User login

Refractive Outcomes for Cataract Surgery With Toric Intraocular Lenses at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center

Cataract surgery is one of the most common ambulatory procedures performed in the US.1-3 With the aging of the US population, the number of Americans with cataracts is projected to increase from 24.4 million in 2010 to 38.7 million in 2030.4

Approximately 20% of all cataract patients have preoperative astigmatism of > 1.5 diopters (D), underscoring the importance of training residents in the placement of toric intraocular lenses (IOLs).5 However, the implantation of toric IOLs is more challenging than monofocal IOLs, requiring precise surgical alignment of the IOL.6 Successful toric IOL implantation also requires accurate calculation of the IOL cylinder power and target axis of alignment. It is unclear which toric IOL calculation formula offers the most accurate refractive predictions, and practitioners have designed strategies to apply different formulae depending on the biometric dimensions of the target eye.7-9

Previous studies of resident-performed cataract surgery using toric IOLs6,10-13 and studies that compare the performance of the Barrett and Holladay toric formulae have been limited by their small sample sizes (< 107 eyes).7,14-16 Moreover, none of the studies that evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these biometric formulae were conducted at a teaching hospital.7,14-16

Given the added complexity of toric IOL placement and variable surgical experience of residents as ophthalmologists-in-training, it is important to assess outcomes in teaching hospitals.13 The primary aims of this study were to assess the visual and refractive outcomes of cataract surgery using toric IOLs in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) teaching hospital and to compare the relative accuracy of the Holladay 2 or Barrett toric biometric formulae in predicting postoperative refraction outcomes.

Methods

The Providence VA Medical Center (PVAMC) Institutional Review Board approved this study. This retrospective chart review included patients with cataract and corneal astigmatism who underwent cataract surgery using Acrysof toric IOLs, model SN6AT (Alcon) at the PVAMC teaching hospital between November 2013 and May 2018.

Only 1 eye was included from each study subject to avoid compounding of data with the use of bilateral eyes.17 In addition, bilateral cataract surgery was only performed on some patients at the PVAMC, so including both eyes from eligible patients would disproportionately weigh those patients’ outcomes. If both eyes had cataract surgery and their postoperative visual acuities were unequal, we chose the eye with the better postoperative visual acuity since refraction accuracy decreases with worsening best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA). If both eyes had cataract surgery and the postoperative visual acuity was the same, the first operated eye was chosen.17,18

Exclusion criteria included worse than 20/40 BCVA, posterior capsular rupture, sulcus IOL, history of corneal disease, history of refractive surgery (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis [LASIK]/photorefractive keratectomy [PRK]), axial length not measurable by the Lenstar optical biometer (Haag-Streit USA), or no postoperative refraction within 3 weeks to 4 months.19,20

Patient age, race/ethnicity, gender, preoperative refraction, preoperative BCVA, postoperative refraction, postoperative BCVA, and IOL power were recorded from patient charts (Table 1). Preoperative and postoperative refractive values were converted to spherical equivalents. The preoperative biometry and most of the postoperative refractions were performed by experienced technicians certified by the Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology. The main outcomes for the assessment of surgeries included the postoperative BCVA, postoperative spherical equivalent refraction, and postoperative residual refractive astigmatism.

Axial length (AL), preoperative anterior chamber depth (ACD), preoperative flat corneal front power (K1), preoperative steep corneal front power (K2), lens thickness, horizontal white-to-white (WTW) corneal diameter, and central corneal thickness (CCT) were recorded from the Lenstar biometric device. Predicted postoperative refractions for the Holladay 2 formula were calculated using Holladay IOL Consultant software (Holladay Consulting). Predicted postoperative refractions for the Barrett toric IOL formula were calculated using the online Barrett toric formula calculator.21 Since previous studies have shown that both the Holladay and Barrett formulae account for posterior corneal astigmatism, a comparison of refractive outcomes in eyes with against-the-rule astigmatism vs with-the-rule astigmatism was not performed.14 An estimated standardized value for surgically-induced astigmatism was entered into both formulae; 0.3 diopter (D) was chosen based on previously published averages.22-24

A formula’s prediction error is defined as the predicted postoperative refraction minus the actual postoperative refraction. The mean absolute prediction error (MAE), defined as the mean of the absolute values of the prediction errors, and the median absolute prediction error (MedAE), defined as the median of the absolute values of the prediction errors, were used to assess the overall accuracy of each formula. Also, the percentages of eyes with postoperative refraction within ≥ 0.25 D, ≥ 0.50 D, and ≥ 1.0 D were calculated for both formulae. Two-tailed t tests were performed to compare the MAE between the formulae. Subgroup analyses were performed for short eyes (AL < 22 mm), medium length eyes (AL = 22-25 mm), and long eyes (AL > 25 mm). Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11 (STATA Corp). The preoperative corneal astigmatism and postoperative refractive astigmatism of all the cases were compared in double-angle plots to assess how well the toric IOL neutralized the corneal astigmatism.

Results

Of 325 charts reviewed during the study period, 34 patients were excluded due to lack of postoperative refraction within the designated follow-up period, 5 for worse than 20/40 postoperative BCVA (4 had preexisting ocular disease), 2 for complications, and 1 for missing data. We included 283 eyes from 283 patients in the final study. Resident ophthalmologists were the primary surgeons in 87.6% (248/283) of the cases.

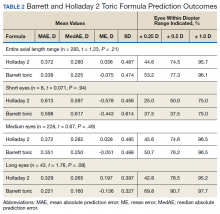

The median postoperative BCVA was 20/20, and 92% of patients had a postoperative BCVA of 20/25 or better. The prediction outcomes of the toric SN6AT IOLs are shown in Table 2. The Barrett toric formula had a lower MAE than the Holladay 2 formula, but this difference was not statistically significant. The Barrett toric formula also predicted a higher percentage of eyes with postoperative refraction within ≥ 0.25 D (53.2%), ≥ 0.5 D (77.3%), and ≥ 1.0 D (96.1%). For both formulae, > 95% of eyes had prediction errors that fell within 1.0 D.

While the Barrett formula demonstrated a lower MAE in all 3 AL groups, no statistically significant differences were found between the Barrett and Holladay formulae (P = .94, P = .49, and P = .08 for short, medium, and long eyes, respectively). Both formulae produced the lowest MAE in the long AL group: Barrett had a MAE of 0.221 D and Holladay 2 had one of 0.329 D. The Barrett formula produced its highest percentage of eyes with prediction errors falling within 0.25 D and 0.5 D in the long AL group. In comparison, both formulae had the highest MAEs in the short AL group (Barrett toric, 0.598 D; Holladay 2, 0.613 D) and produced the lowest percentage of eyes with prediction errors falling within ≥ 0.25 D and ≥ 0.5 D in the short AL group.

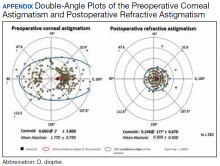

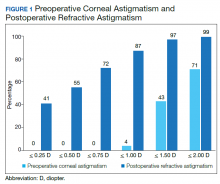

A cumulative histogram of the preoperative corneal and postoperative refractive astigmatism magnitude is shown in Figure 1. The same data are presented as double-angle plots in the Appendix, which shows that the centroid values for preoperative corneal astigmatism were greatlyreduced when compared with the postoperative refractive astigmatism (mean absolute value of 1.77 D ≥ 0.73 D to 0.5 D ≥ 0.50 D).

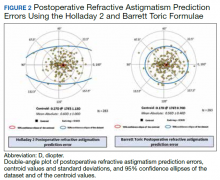

Preoperative corneal astigmatism and postoperative refractive astigmatism were compared since preoperative refractive astigmatism has noncorneal contributions, including lenticular astigmatism, and there is minimal expected change between preoperative and postoperative corneal astigmatism.14 For comparison, double-angle plots of postoperative refractive astigmatism prediction errors for the Holladay and Barrett formulae are shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of resident-performed cataract surgery using toric IOLs, the largest study that compared the performance of the Barrett toric and Holladay 2 formulae, and the first that compared these formulae in a teaching hospital setting. This study found no significant difference in the predictive accuracy of the Barrett and Holladay 2 biometric formulae for cataract surgery using toric IOLs. In addition, our refractive outcomes were consistent with the results of previous toric IOL outcome studies conducted in teaching and nonteaching hospital settings.6,10-13

In 4 previous studies that compared the MAE of the Barrett and Holladay formulae for toric IOLs, the Barrett formula produced a lower MAE than the Holladay 2 formula.7,14-16 However, this difference was significant in only 2 of the studies, which had sample sizes of only 68 and 107 eyes.14,16 Furthermore, the Barrett toric formula produced the lower MAE for the entire AL range, though this was not statistically significant at our sample size. In addition, both formulae produced the lowest MAE in the long AL group and the highest MAE in the short AL group. The unique anatomy and high IOL power needed in short eyes may explain the challenges in attaining accurate IOL power predictions in this AL group.19,25

Limitations

The sample size of this study may have prevented us from detecting statistically significant differences in the performance of the Barrett and Holladay formulae. However, our findings are consistent with studies that compare the accuracy of these formulae in teaching and nonteaching hospital settings. Second, the study was conducted at a VA hospital, and a high proportion of patients were male; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to patients who receive cataract surgery with toric IOLs in other settings.

Conclusions

In a single VA teaching hospital, the Barrett and Holladay 2 biometric formulae provide similar refractive predictions for cataract surgery using toric IOLs. Larger studies would be necessary to detect smaller differences in the relative performance of the biometric formulae.

1. Schein OD, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Gower EW. Cataract surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(5):257-264.

2. Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):477-485.

3. Congdon N, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, et al. Prevalence of cataract and pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):487-494.

4. National Eye Institute. Cataract tables: cataract defined. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/resources-for-health-educators/eye-health-data-and-statistics/cataract-data-and-statistics/cataract-tables. Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2020.

5. Ostri C, Falck L, Boberg-Ans G, Kessel L. The need for toric intra-ocular lens implantation in public ophthalmology departments. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(5):e396-e397.

6. Sundy M, McKnight D, Eck C, Rieger F 3rd. Visual acuity outcomes of toric lens implantation in patients undergoing cataract surgery at a residency training program. Mo Med. 2016;113(1):40-43.

7. Ferreira TB, Ribeiro P, Ribeiro FJ, O’Neill JG. Comparison of methodologies using estimated or measured values of total corneal astigmatism for toric intraocular lens power calculation. J Refract Surg. 2017;33(12):794-800.

8. Reitblat O, Levy A, Kleinmann G, Abulafia A, Assia EI. Effect of posterior corneal astigmatism on power calculation and alignment of toric intraocular lenses: comparison of methodologies. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(2):217-225.

9. Aristodemou P, Knox Cartwright NE, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. Formula choice: Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, or SRK/T and refractive outcomes in 8108 eyes after cataract surgery with biometry by partial coherence interferometry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(1):63-71.

10. Moreira HR, Hatch KM, Greenberg PB. Benchmarking outcomes in resident-performed cataract surgery with toric intraocular lenses [published correction appears in: Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013;41(8):819]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(6):624-626.

11. Retzlaff JA, Sanders DR, Kraff MC. Development of the SRK/T intraocular lens implant power calculation formula [published correction appears in: J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(4):528]. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(3):333-340.

12. Roensch MA, Charton JW, Blomquist PH, Aggarwal NK, McCulley JP. Resident experience with toric and multifocal intraocular lenses in a public county hospital system. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(5):793-798.

13. Pouyeh B, Galor A, Junk AK, et al. Surgical and refractive outcomes of cataract surgery with toric intraocular lens implantation at a resident-teaching institution. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(9):1623-1628.

14. Ferreira TB, Ribeiro P, Ribeiro FJ, O’Neill JG. Comparison of astigmatic prediction errors associated with new calculation methods for toric intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43(3):340-347.

15. Abulafia A, Hill WE, Franchina M, Barrett GD. Comparison of methods to predict residual astigmatism after intraocular lens implantation. J Refract Surg. 2015;31(10):699-707.

16. Abulafia A, Barrett GD, Kleinmann G, et al. Prediction of refractive outcomes with toric intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(5):936-944.

17. Wang Q, Jiang W, Lin T, Wu X, Lin H, Chen W. Meta-analysis of accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation formulas in short eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(4):356-363.

18. Melles RB, Holladay JT, Chang WJ. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculation formulas. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(2):169-178.

19. Hoffer KJ. The Hoffer Q formula: a comparison of theoretic and regression formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19(6):700-712.

20. Cooke DL, Cooke TL. Comparison of 9 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(8):1157-1164.

21. American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Barrett toric calculator. www.ascrs.org/barrett-toric-calculator. Accessed February 5, 2020.

22. Holladay JT, Pettit G. Improving toric intraocular lens calculations using total surgically induced astigmatism for a 2.5 mm temporal incision. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(3):272-283.

23. Canovas C, Alarcon A, Rosén R, et al. New algorithm for toric intraocular lens power calculation considering the posterior corneal astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(2):168-174.

24. Visser N, Berendschot TT, Bauer NJ, Nuijts RM. Vector analysis of corneal and refractive astigmatism changes following toric pseudophakic and toric phakic IOL implantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):1865-1873.

25. Narváez J, Zimmerman G, Stulting RD, Chang DH. Accuracy of intraocular lens power prediction using the Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, Holladay 2, and SRK/T formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(12):2050-2053.

Cataract surgery is one of the most common ambulatory procedures performed in the US.1-3 With the aging of the US population, the number of Americans with cataracts is projected to increase from 24.4 million in 2010 to 38.7 million in 2030.4

Approximately 20% of all cataract patients have preoperative astigmatism of > 1.5 diopters (D), underscoring the importance of training residents in the placement of toric intraocular lenses (IOLs).5 However, the implantation of toric IOLs is more challenging than monofocal IOLs, requiring precise surgical alignment of the IOL.6 Successful toric IOL implantation also requires accurate calculation of the IOL cylinder power and target axis of alignment. It is unclear which toric IOL calculation formula offers the most accurate refractive predictions, and practitioners have designed strategies to apply different formulae depending on the biometric dimensions of the target eye.7-9

Previous studies of resident-performed cataract surgery using toric IOLs6,10-13 and studies that compare the performance of the Barrett and Holladay toric formulae have been limited by their small sample sizes (< 107 eyes).7,14-16 Moreover, none of the studies that evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these biometric formulae were conducted at a teaching hospital.7,14-16

Given the added complexity of toric IOL placement and variable surgical experience of residents as ophthalmologists-in-training, it is important to assess outcomes in teaching hospitals.13 The primary aims of this study were to assess the visual and refractive outcomes of cataract surgery using toric IOLs in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) teaching hospital and to compare the relative accuracy of the Holladay 2 or Barrett toric biometric formulae in predicting postoperative refraction outcomes.

Methods

The Providence VA Medical Center (PVAMC) Institutional Review Board approved this study. This retrospective chart review included patients with cataract and corneal astigmatism who underwent cataract surgery using Acrysof toric IOLs, model SN6AT (Alcon) at the PVAMC teaching hospital between November 2013 and May 2018.

Only 1 eye was included from each study subject to avoid compounding of data with the use of bilateral eyes.17 In addition, bilateral cataract surgery was only performed on some patients at the PVAMC, so including both eyes from eligible patients would disproportionately weigh those patients’ outcomes. If both eyes had cataract surgery and their postoperative visual acuities were unequal, we chose the eye with the better postoperative visual acuity since refraction accuracy decreases with worsening best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA). If both eyes had cataract surgery and the postoperative visual acuity was the same, the first operated eye was chosen.17,18

Exclusion criteria included worse than 20/40 BCVA, posterior capsular rupture, sulcus IOL, history of corneal disease, history of refractive surgery (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis [LASIK]/photorefractive keratectomy [PRK]), axial length not measurable by the Lenstar optical biometer (Haag-Streit USA), or no postoperative refraction within 3 weeks to 4 months.19,20

Patient age, race/ethnicity, gender, preoperative refraction, preoperative BCVA, postoperative refraction, postoperative BCVA, and IOL power were recorded from patient charts (Table 1). Preoperative and postoperative refractive values were converted to spherical equivalents. The preoperative biometry and most of the postoperative refractions were performed by experienced technicians certified by the Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology. The main outcomes for the assessment of surgeries included the postoperative BCVA, postoperative spherical equivalent refraction, and postoperative residual refractive astigmatism.

Axial length (AL), preoperative anterior chamber depth (ACD), preoperative flat corneal front power (K1), preoperative steep corneal front power (K2), lens thickness, horizontal white-to-white (WTW) corneal diameter, and central corneal thickness (CCT) were recorded from the Lenstar biometric device. Predicted postoperative refractions for the Holladay 2 formula were calculated using Holladay IOL Consultant software (Holladay Consulting). Predicted postoperative refractions for the Barrett toric IOL formula were calculated using the online Barrett toric formula calculator.21 Since previous studies have shown that both the Holladay and Barrett formulae account for posterior corneal astigmatism, a comparison of refractive outcomes in eyes with against-the-rule astigmatism vs with-the-rule astigmatism was not performed.14 An estimated standardized value for surgically-induced astigmatism was entered into both formulae; 0.3 diopter (D) was chosen based on previously published averages.22-24

A formula’s prediction error is defined as the predicted postoperative refraction minus the actual postoperative refraction. The mean absolute prediction error (MAE), defined as the mean of the absolute values of the prediction errors, and the median absolute prediction error (MedAE), defined as the median of the absolute values of the prediction errors, were used to assess the overall accuracy of each formula. Also, the percentages of eyes with postoperative refraction within ≥ 0.25 D, ≥ 0.50 D, and ≥ 1.0 D were calculated for both formulae. Two-tailed t tests were performed to compare the MAE between the formulae. Subgroup analyses were performed for short eyes (AL < 22 mm), medium length eyes (AL = 22-25 mm), and long eyes (AL > 25 mm). Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11 (STATA Corp). The preoperative corneal astigmatism and postoperative refractive astigmatism of all the cases were compared in double-angle plots to assess how well the toric IOL neutralized the corneal astigmatism.

Results

Of 325 charts reviewed during the study period, 34 patients were excluded due to lack of postoperative refraction within the designated follow-up period, 5 for worse than 20/40 postoperative BCVA (4 had preexisting ocular disease), 2 for complications, and 1 for missing data. We included 283 eyes from 283 patients in the final study. Resident ophthalmologists were the primary surgeons in 87.6% (248/283) of the cases.

The median postoperative BCVA was 20/20, and 92% of patients had a postoperative BCVA of 20/25 or better. The prediction outcomes of the toric SN6AT IOLs are shown in Table 2. The Barrett toric formula had a lower MAE than the Holladay 2 formula, but this difference was not statistically significant. The Barrett toric formula also predicted a higher percentage of eyes with postoperative refraction within ≥ 0.25 D (53.2%), ≥ 0.5 D (77.3%), and ≥ 1.0 D (96.1%). For both formulae, > 95% of eyes had prediction errors that fell within 1.0 D.

While the Barrett formula demonstrated a lower MAE in all 3 AL groups, no statistically significant differences were found between the Barrett and Holladay formulae (P = .94, P = .49, and P = .08 for short, medium, and long eyes, respectively). Both formulae produced the lowest MAE in the long AL group: Barrett had a MAE of 0.221 D and Holladay 2 had one of 0.329 D. The Barrett formula produced its highest percentage of eyes with prediction errors falling within 0.25 D and 0.5 D in the long AL group. In comparison, both formulae had the highest MAEs in the short AL group (Barrett toric, 0.598 D; Holladay 2, 0.613 D) and produced the lowest percentage of eyes with prediction errors falling within ≥ 0.25 D and ≥ 0.5 D in the short AL group.

A cumulative histogram of the preoperative corneal and postoperative refractive astigmatism magnitude is shown in Figure 1. The same data are presented as double-angle plots in the Appendix, which shows that the centroid values for preoperative corneal astigmatism were greatlyreduced when compared with the postoperative refractive astigmatism (mean absolute value of 1.77 D ≥ 0.73 D to 0.5 D ≥ 0.50 D).

Preoperative corneal astigmatism and postoperative refractive astigmatism were compared since preoperative refractive astigmatism has noncorneal contributions, including lenticular astigmatism, and there is minimal expected change between preoperative and postoperative corneal astigmatism.14 For comparison, double-angle plots of postoperative refractive astigmatism prediction errors for the Holladay and Barrett formulae are shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of resident-performed cataract surgery using toric IOLs, the largest study that compared the performance of the Barrett toric and Holladay 2 formulae, and the first that compared these formulae in a teaching hospital setting. This study found no significant difference in the predictive accuracy of the Barrett and Holladay 2 biometric formulae for cataract surgery using toric IOLs. In addition, our refractive outcomes were consistent with the results of previous toric IOL outcome studies conducted in teaching and nonteaching hospital settings.6,10-13

In 4 previous studies that compared the MAE of the Barrett and Holladay formulae for toric IOLs, the Barrett formula produced a lower MAE than the Holladay 2 formula.7,14-16 However, this difference was significant in only 2 of the studies, which had sample sizes of only 68 and 107 eyes.14,16 Furthermore, the Barrett toric formula produced the lower MAE for the entire AL range, though this was not statistically significant at our sample size. In addition, both formulae produced the lowest MAE in the long AL group and the highest MAE in the short AL group. The unique anatomy and high IOL power needed in short eyes may explain the challenges in attaining accurate IOL power predictions in this AL group.19,25

Limitations

The sample size of this study may have prevented us from detecting statistically significant differences in the performance of the Barrett and Holladay formulae. However, our findings are consistent with studies that compare the accuracy of these formulae in teaching and nonteaching hospital settings. Second, the study was conducted at a VA hospital, and a high proportion of patients were male; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to patients who receive cataract surgery with toric IOLs in other settings.

Conclusions

In a single VA teaching hospital, the Barrett and Holladay 2 biometric formulae provide similar refractive predictions for cataract surgery using toric IOLs. Larger studies would be necessary to detect smaller differences in the relative performance of the biometric formulae.

Cataract surgery is one of the most common ambulatory procedures performed in the US.1-3 With the aging of the US population, the number of Americans with cataracts is projected to increase from 24.4 million in 2010 to 38.7 million in 2030.4

Approximately 20% of all cataract patients have preoperative astigmatism of > 1.5 diopters (D), underscoring the importance of training residents in the placement of toric intraocular lenses (IOLs).5 However, the implantation of toric IOLs is more challenging than monofocal IOLs, requiring precise surgical alignment of the IOL.6 Successful toric IOL implantation also requires accurate calculation of the IOL cylinder power and target axis of alignment. It is unclear which toric IOL calculation formula offers the most accurate refractive predictions, and practitioners have designed strategies to apply different formulae depending on the biometric dimensions of the target eye.7-9

Previous studies of resident-performed cataract surgery using toric IOLs6,10-13 and studies that compare the performance of the Barrett and Holladay toric formulae have been limited by their small sample sizes (< 107 eyes).7,14-16 Moreover, none of the studies that evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these biometric formulae were conducted at a teaching hospital.7,14-16

Given the added complexity of toric IOL placement and variable surgical experience of residents as ophthalmologists-in-training, it is important to assess outcomes in teaching hospitals.13 The primary aims of this study were to assess the visual and refractive outcomes of cataract surgery using toric IOLs in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) teaching hospital and to compare the relative accuracy of the Holladay 2 or Barrett toric biometric formulae in predicting postoperative refraction outcomes.

Methods

The Providence VA Medical Center (PVAMC) Institutional Review Board approved this study. This retrospective chart review included patients with cataract and corneal astigmatism who underwent cataract surgery using Acrysof toric IOLs, model SN6AT (Alcon) at the PVAMC teaching hospital between November 2013 and May 2018.

Only 1 eye was included from each study subject to avoid compounding of data with the use of bilateral eyes.17 In addition, bilateral cataract surgery was only performed on some patients at the PVAMC, so including both eyes from eligible patients would disproportionately weigh those patients’ outcomes. If both eyes had cataract surgery and their postoperative visual acuities were unequal, we chose the eye with the better postoperative visual acuity since refraction accuracy decreases with worsening best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA). If both eyes had cataract surgery and the postoperative visual acuity was the same, the first operated eye was chosen.17,18

Exclusion criteria included worse than 20/40 BCVA, posterior capsular rupture, sulcus IOL, history of corneal disease, history of refractive surgery (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis [LASIK]/photorefractive keratectomy [PRK]), axial length not measurable by the Lenstar optical biometer (Haag-Streit USA), or no postoperative refraction within 3 weeks to 4 months.19,20

Patient age, race/ethnicity, gender, preoperative refraction, preoperative BCVA, postoperative refraction, postoperative BCVA, and IOL power were recorded from patient charts (Table 1). Preoperative and postoperative refractive values were converted to spherical equivalents. The preoperative biometry and most of the postoperative refractions were performed by experienced technicians certified by the Joint Commission on Allied Health Personnel in Ophthalmology. The main outcomes for the assessment of surgeries included the postoperative BCVA, postoperative spherical equivalent refraction, and postoperative residual refractive astigmatism.

Axial length (AL), preoperative anterior chamber depth (ACD), preoperative flat corneal front power (K1), preoperative steep corneal front power (K2), lens thickness, horizontal white-to-white (WTW) corneal diameter, and central corneal thickness (CCT) were recorded from the Lenstar biometric device. Predicted postoperative refractions for the Holladay 2 formula were calculated using Holladay IOL Consultant software (Holladay Consulting). Predicted postoperative refractions for the Barrett toric IOL formula were calculated using the online Barrett toric formula calculator.21 Since previous studies have shown that both the Holladay and Barrett formulae account for posterior corneal astigmatism, a comparison of refractive outcomes in eyes with against-the-rule astigmatism vs with-the-rule astigmatism was not performed.14 An estimated standardized value for surgically-induced astigmatism was entered into both formulae; 0.3 diopter (D) was chosen based on previously published averages.22-24

A formula’s prediction error is defined as the predicted postoperative refraction minus the actual postoperative refraction. The mean absolute prediction error (MAE), defined as the mean of the absolute values of the prediction errors, and the median absolute prediction error (MedAE), defined as the median of the absolute values of the prediction errors, were used to assess the overall accuracy of each formula. Also, the percentages of eyes with postoperative refraction within ≥ 0.25 D, ≥ 0.50 D, and ≥ 1.0 D were calculated for both formulae. Two-tailed t tests were performed to compare the MAE between the formulae. Subgroup analyses were performed for short eyes (AL < 22 mm), medium length eyes (AL = 22-25 mm), and long eyes (AL > 25 mm). Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 11 (STATA Corp). The preoperative corneal astigmatism and postoperative refractive astigmatism of all the cases were compared in double-angle plots to assess how well the toric IOL neutralized the corneal astigmatism.

Results

Of 325 charts reviewed during the study period, 34 patients were excluded due to lack of postoperative refraction within the designated follow-up period, 5 for worse than 20/40 postoperative BCVA (4 had preexisting ocular disease), 2 for complications, and 1 for missing data. We included 283 eyes from 283 patients in the final study. Resident ophthalmologists were the primary surgeons in 87.6% (248/283) of the cases.

The median postoperative BCVA was 20/20, and 92% of patients had a postoperative BCVA of 20/25 or better. The prediction outcomes of the toric SN6AT IOLs are shown in Table 2. The Barrett toric formula had a lower MAE than the Holladay 2 formula, but this difference was not statistically significant. The Barrett toric formula also predicted a higher percentage of eyes with postoperative refraction within ≥ 0.25 D (53.2%), ≥ 0.5 D (77.3%), and ≥ 1.0 D (96.1%). For both formulae, > 95% of eyes had prediction errors that fell within 1.0 D.

While the Barrett formula demonstrated a lower MAE in all 3 AL groups, no statistically significant differences were found between the Barrett and Holladay formulae (P = .94, P = .49, and P = .08 for short, medium, and long eyes, respectively). Both formulae produced the lowest MAE in the long AL group: Barrett had a MAE of 0.221 D and Holladay 2 had one of 0.329 D. The Barrett formula produced its highest percentage of eyes with prediction errors falling within 0.25 D and 0.5 D in the long AL group. In comparison, both formulae had the highest MAEs in the short AL group (Barrett toric, 0.598 D; Holladay 2, 0.613 D) and produced the lowest percentage of eyes with prediction errors falling within ≥ 0.25 D and ≥ 0.5 D in the short AL group.

A cumulative histogram of the preoperative corneal and postoperative refractive astigmatism magnitude is shown in Figure 1. The same data are presented as double-angle plots in the Appendix, which shows that the centroid values for preoperative corneal astigmatism were greatlyreduced when compared with the postoperative refractive astigmatism (mean absolute value of 1.77 D ≥ 0.73 D to 0.5 D ≥ 0.50 D).

Preoperative corneal astigmatism and postoperative refractive astigmatism were compared since preoperative refractive astigmatism has noncorneal contributions, including lenticular astigmatism, and there is minimal expected change between preoperative and postoperative corneal astigmatism.14 For comparison, double-angle plots of postoperative refractive astigmatism prediction errors for the Holladay and Barrett formulae are shown in Figure 2.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study of resident-performed cataract surgery using toric IOLs, the largest study that compared the performance of the Barrett toric and Holladay 2 formulae, and the first that compared these formulae in a teaching hospital setting. This study found no significant difference in the predictive accuracy of the Barrett and Holladay 2 biometric formulae for cataract surgery using toric IOLs. In addition, our refractive outcomes were consistent with the results of previous toric IOL outcome studies conducted in teaching and nonteaching hospital settings.6,10-13

In 4 previous studies that compared the MAE of the Barrett and Holladay formulae for toric IOLs, the Barrett formula produced a lower MAE than the Holladay 2 formula.7,14-16 However, this difference was significant in only 2 of the studies, which had sample sizes of only 68 and 107 eyes.14,16 Furthermore, the Barrett toric formula produced the lower MAE for the entire AL range, though this was not statistically significant at our sample size. In addition, both formulae produced the lowest MAE in the long AL group and the highest MAE in the short AL group. The unique anatomy and high IOL power needed in short eyes may explain the challenges in attaining accurate IOL power predictions in this AL group.19,25

Limitations

The sample size of this study may have prevented us from detecting statistically significant differences in the performance of the Barrett and Holladay formulae. However, our findings are consistent with studies that compare the accuracy of these formulae in teaching and nonteaching hospital settings. Second, the study was conducted at a VA hospital, and a high proportion of patients were male; thus, our findings may not be generalizable to patients who receive cataract surgery with toric IOLs in other settings.

Conclusions

In a single VA teaching hospital, the Barrett and Holladay 2 biometric formulae provide similar refractive predictions for cataract surgery using toric IOLs. Larger studies would be necessary to detect smaller differences in the relative performance of the biometric formulae.

1. Schein OD, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Gower EW. Cataract surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(5):257-264.

2. Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):477-485.

3. Congdon N, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, et al. Prevalence of cataract and pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):487-494.

4. National Eye Institute. Cataract tables: cataract defined. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/resources-for-health-educators/eye-health-data-and-statistics/cataract-data-and-statistics/cataract-tables. Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2020.

5. Ostri C, Falck L, Boberg-Ans G, Kessel L. The need for toric intra-ocular lens implantation in public ophthalmology departments. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(5):e396-e397.

6. Sundy M, McKnight D, Eck C, Rieger F 3rd. Visual acuity outcomes of toric lens implantation in patients undergoing cataract surgery at a residency training program. Mo Med. 2016;113(1):40-43.

7. Ferreira TB, Ribeiro P, Ribeiro FJ, O’Neill JG. Comparison of methodologies using estimated or measured values of total corneal astigmatism for toric intraocular lens power calculation. J Refract Surg. 2017;33(12):794-800.

8. Reitblat O, Levy A, Kleinmann G, Abulafia A, Assia EI. Effect of posterior corneal astigmatism on power calculation and alignment of toric intraocular lenses: comparison of methodologies. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(2):217-225.

9. Aristodemou P, Knox Cartwright NE, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. Formula choice: Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, or SRK/T and refractive outcomes in 8108 eyes after cataract surgery with biometry by partial coherence interferometry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(1):63-71.

10. Moreira HR, Hatch KM, Greenberg PB. Benchmarking outcomes in resident-performed cataract surgery with toric intraocular lenses [published correction appears in: Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013;41(8):819]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(6):624-626.

11. Retzlaff JA, Sanders DR, Kraff MC. Development of the SRK/T intraocular lens implant power calculation formula [published correction appears in: J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(4):528]. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(3):333-340.

12. Roensch MA, Charton JW, Blomquist PH, Aggarwal NK, McCulley JP. Resident experience with toric and multifocal intraocular lenses in a public county hospital system. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(5):793-798.

13. Pouyeh B, Galor A, Junk AK, et al. Surgical and refractive outcomes of cataract surgery with toric intraocular lens implantation at a resident-teaching institution. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(9):1623-1628.

14. Ferreira TB, Ribeiro P, Ribeiro FJ, O’Neill JG. Comparison of astigmatic prediction errors associated with new calculation methods for toric intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43(3):340-347.

15. Abulafia A, Hill WE, Franchina M, Barrett GD. Comparison of methods to predict residual astigmatism after intraocular lens implantation. J Refract Surg. 2015;31(10):699-707.

16. Abulafia A, Barrett GD, Kleinmann G, et al. Prediction of refractive outcomes with toric intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(5):936-944.

17. Wang Q, Jiang W, Lin T, Wu X, Lin H, Chen W. Meta-analysis of accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation formulas in short eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(4):356-363.

18. Melles RB, Holladay JT, Chang WJ. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculation formulas. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(2):169-178.

19. Hoffer KJ. The Hoffer Q formula: a comparison of theoretic and regression formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19(6):700-712.

20. Cooke DL, Cooke TL. Comparison of 9 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(8):1157-1164.

21. American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Barrett toric calculator. www.ascrs.org/barrett-toric-calculator. Accessed February 5, 2020.

22. Holladay JT, Pettit G. Improving toric intraocular lens calculations using total surgically induced astigmatism for a 2.5 mm temporal incision. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(3):272-283.

23. Canovas C, Alarcon A, Rosén R, et al. New algorithm for toric intraocular lens power calculation considering the posterior corneal astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(2):168-174.

24. Visser N, Berendschot TT, Bauer NJ, Nuijts RM. Vector analysis of corneal and refractive astigmatism changes following toric pseudophakic and toric phakic IOL implantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):1865-1873.

25. Narváez J, Zimmerman G, Stulting RD, Chang DH. Accuracy of intraocular lens power prediction using the Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, Holladay 2, and SRK/T formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(12):2050-2053.

1. Schein OD, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Gower EW. Cataract surgery among Medicare beneficiaries. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(5):257-264.

2. Congdon N, O’Colmain B, Klaver CC, et al. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):477-485.

3. Congdon N, Vingerling JR, Klein BE, et al. Prevalence of cataract and pseudophakia/aphakia among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):487-494.

4. National Eye Institute. Cataract tables: cataract defined. https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/resources-for-health-educators/eye-health-data-and-statistics/cataract-data-and-statistics/cataract-tables. Updated February 7, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2020.

5. Ostri C, Falck L, Boberg-Ans G, Kessel L. The need for toric intra-ocular lens implantation in public ophthalmology departments. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(5):e396-e397.

6. Sundy M, McKnight D, Eck C, Rieger F 3rd. Visual acuity outcomes of toric lens implantation in patients undergoing cataract surgery at a residency training program. Mo Med. 2016;113(1):40-43.

7. Ferreira TB, Ribeiro P, Ribeiro FJ, O’Neill JG. Comparison of methodologies using estimated or measured values of total corneal astigmatism for toric intraocular lens power calculation. J Refract Surg. 2017;33(12):794-800.

8. Reitblat O, Levy A, Kleinmann G, Abulafia A, Assia EI. Effect of posterior corneal astigmatism on power calculation and alignment of toric intraocular lenses: comparison of methodologies. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(2):217-225.

9. Aristodemou P, Knox Cartwright NE, Sparrow JM, Johnston RL. Formula choice: Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, or SRK/T and refractive outcomes in 8108 eyes after cataract surgery with biometry by partial coherence interferometry. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(1):63-71.

10. Moreira HR, Hatch KM, Greenberg PB. Benchmarking outcomes in resident-performed cataract surgery with toric intraocular lenses [published correction appears in: Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2013;41(8):819]. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013;41(6):624-626.

11. Retzlaff JA, Sanders DR, Kraff MC. Development of the SRK/T intraocular lens implant power calculation formula [published correction appears in: J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(4):528]. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1990;16(3):333-340.

12. Roensch MA, Charton JW, Blomquist PH, Aggarwal NK, McCulley JP. Resident experience with toric and multifocal intraocular lenses in a public county hospital system. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2012;38(5):793-798.

13. Pouyeh B, Galor A, Junk AK, et al. Surgical and refractive outcomes of cataract surgery with toric intraocular lens implantation at a resident-teaching institution. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2011;37(9):1623-1628.

14. Ferreira TB, Ribeiro P, Ribeiro FJ, O’Neill JG. Comparison of astigmatic prediction errors associated with new calculation methods for toric intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2017;43(3):340-347.

15. Abulafia A, Hill WE, Franchina M, Barrett GD. Comparison of methods to predict residual astigmatism after intraocular lens implantation. J Refract Surg. 2015;31(10):699-707.

16. Abulafia A, Barrett GD, Kleinmann G, et al. Prediction of refractive outcomes with toric intraocular lens implantation. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2015;41(5):936-944.

17. Wang Q, Jiang W, Lin T, Wu X, Lin H, Chen W. Meta-analysis of accuracy of intraocular lens power calculation formulas in short eyes. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2018;46(4):356-363.

18. Melles RB, Holladay JT, Chang WJ. Accuracy of intraocular lens calculation formulas. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(2):169-178.

19. Hoffer KJ. The Hoffer Q formula: a comparison of theoretic and regression formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1993;19(6):700-712.

20. Cooke DL, Cooke TL. Comparison of 9 intraocular lens power calculation formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2016;42(8):1157-1164.

21. American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. Barrett toric calculator. www.ascrs.org/barrett-toric-calculator. Accessed February 5, 2020.

22. Holladay JT, Pettit G. Improving toric intraocular lens calculations using total surgically induced astigmatism for a 2.5 mm temporal incision. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2019;45(3):272-283.

23. Canovas C, Alarcon A, Rosén R, et al. New algorithm for toric intraocular lens power calculation considering the posterior corneal astigmatism. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(2):168-174.

24. Visser N, Berendschot TT, Bauer NJ, Nuijts RM. Vector analysis of corneal and refractive astigmatism changes following toric pseudophakic and toric phakic IOL implantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(4):1865-1873.

25. Narváez J, Zimmerman G, Stulting RD, Chang DH. Accuracy of intraocular lens power prediction using the Hoffer Q, Holladay 1, Holladay 2, and SRK/T formulas. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2006;32(12):2050-2053.

Loneliness, social isolation in seniors need urgent attention

Health care systems need to take urgent action to address social isolation and loneliness among U.S. seniors, experts say.

A new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) points out that social isolation in this population is a major public health concern that contributes to heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The report authors note that the health care system remains an underused partner in preventing, identifying, and intervening in social isolation and loneliness among adults over age 50.

For seniors who are homebound, have no family, or do not belong to community or faith groups, a medical appointment or home health visit may be one of the few social interactions they have, the report notes.

Health care providers and systems may be “first responders” in recognizing lonely or socially isolated patients, committee chair Dan Blazer, MD, from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., said during a press briefing.

As deadly as obesity, smoking

Committee member Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, from Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, noted that social isolation and loneliness are “distinctly different.”

Social isolation is defined as an objective lack of (or limited) social connections, while loneliness is a subjective perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely.

Not all older adults are isolated or lonely, but they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone and the loss of loved ones, she explained.

The issue may be compounded for LGBT, minority, and immigrant older adults, who may already face barriers to care, stigma, and discrimination. Social isolation and loneliness may also directly stem from chronic illness, hearing or vision loss, or mobility issues. In these cases, health care providers might be able to help prevent or reduce social isolation and loneliness by directly addressing the underlying health-related causes.

Holt-Lunstad told the briefing. The report offers a vision for how the health care system can identify people at risk of social isolation and loneliness, intervene, and engage other community partners.

It recommends that providers use validated tools to periodically assess patients who may be at risk for social isolation and loneliness and connect them to community resources for help.

The report also calls for greater education and training among health providers. Schools of health professions and training programs for direct care workers (eg, home health aides, nurse aides, and personal care aides) should incorporate social isolation and loneliness in their curricula, the report says.

It also offers recommendations for leveraging digital health and health technology, improving community partnerships, increasing funding for research, and creation of a national resource center under the Department of Health and Human Services.

Blazer said there remains “much to be learned” about what approaches to mitigating social isolation and loneliness work best in which populations.

The report, from the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, was sponsored by the AARP Foundation.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health care systems need to take urgent action to address social isolation and loneliness among U.S. seniors, experts say.

A new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) points out that social isolation in this population is a major public health concern that contributes to heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The report authors note that the health care system remains an underused partner in preventing, identifying, and intervening in social isolation and loneliness among adults over age 50.

For seniors who are homebound, have no family, or do not belong to community or faith groups, a medical appointment or home health visit may be one of the few social interactions they have, the report notes.

Health care providers and systems may be “first responders” in recognizing lonely or socially isolated patients, committee chair Dan Blazer, MD, from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., said during a press briefing.

As deadly as obesity, smoking

Committee member Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, from Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, noted that social isolation and loneliness are “distinctly different.”

Social isolation is defined as an objective lack of (or limited) social connections, while loneliness is a subjective perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely.

Not all older adults are isolated or lonely, but they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone and the loss of loved ones, she explained.

The issue may be compounded for LGBT, minority, and immigrant older adults, who may already face barriers to care, stigma, and discrimination. Social isolation and loneliness may also directly stem from chronic illness, hearing or vision loss, or mobility issues. In these cases, health care providers might be able to help prevent or reduce social isolation and loneliness by directly addressing the underlying health-related causes.

Holt-Lunstad told the briefing. The report offers a vision for how the health care system can identify people at risk of social isolation and loneliness, intervene, and engage other community partners.

It recommends that providers use validated tools to periodically assess patients who may be at risk for social isolation and loneliness and connect them to community resources for help.

The report also calls for greater education and training among health providers. Schools of health professions and training programs for direct care workers (eg, home health aides, nurse aides, and personal care aides) should incorporate social isolation and loneliness in their curricula, the report says.

It also offers recommendations for leveraging digital health and health technology, improving community partnerships, increasing funding for research, and creation of a national resource center under the Department of Health and Human Services.

Blazer said there remains “much to be learned” about what approaches to mitigating social isolation and loneliness work best in which populations.

The report, from the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, was sponsored by the AARP Foundation.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Health care systems need to take urgent action to address social isolation and loneliness among U.S. seniors, experts say.

A new report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NAS) points out that social isolation in this population is a major public health concern that contributes to heart disease, depression, and premature death.

The report authors note that the health care system remains an underused partner in preventing, identifying, and intervening in social isolation and loneliness among adults over age 50.

For seniors who are homebound, have no family, or do not belong to community or faith groups, a medical appointment or home health visit may be one of the few social interactions they have, the report notes.

Health care providers and systems may be “first responders” in recognizing lonely or socially isolated patients, committee chair Dan Blazer, MD, from Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, N.C., said during a press briefing.

As deadly as obesity, smoking

Committee member Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, from Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, noted that social isolation and loneliness are “distinctly different.”

Social isolation is defined as an objective lack of (or limited) social connections, while loneliness is a subjective perception of social isolation or the subjective feeling of being lonely.

Not all older adults are isolated or lonely, but they are more likely to face predisposing factors such as living alone and the loss of loved ones, she explained.

The issue may be compounded for LGBT, minority, and immigrant older adults, who may already face barriers to care, stigma, and discrimination. Social isolation and loneliness may also directly stem from chronic illness, hearing or vision loss, or mobility issues. In these cases, health care providers might be able to help prevent or reduce social isolation and loneliness by directly addressing the underlying health-related causes.

Holt-Lunstad told the briefing. The report offers a vision for how the health care system can identify people at risk of social isolation and loneliness, intervene, and engage other community partners.

It recommends that providers use validated tools to periodically assess patients who may be at risk for social isolation and loneliness and connect them to community resources for help.

The report also calls for greater education and training among health providers. Schools of health professions and training programs for direct care workers (eg, home health aides, nurse aides, and personal care aides) should incorporate social isolation and loneliness in their curricula, the report says.

It also offers recommendations for leveraging digital health and health technology, improving community partnerships, increasing funding for research, and creation of a national resource center under the Department of Health and Human Services.

Blazer said there remains “much to be learned” about what approaches to mitigating social isolation and loneliness work best in which populations.

The report, from the Committee on the Health and Medical Dimensions of Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults, was sponsored by the AARP Foundation.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

RA magnifies fragility fracture risk in ESRD

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

MAUI, HAWAII – Comorbid rheumatoid arthritis is a force multiplier for fragility fracture risk in patients with end-stage renal disease, Renée Peterkin-McCalman, MD, reported at the 2020 Rheumatology Winter Clinical Symposium.

“Patients with RA and ESRD are at substantially increased risk of osteoporotic fragility fractures compared to the overall population of ESRD patients. So fracture prevention prior to initiation of dialysis should be a focus of care in patients with RA,” said Dr. Peterkin-McCalman, a rheumatology fellow at the Medical College of Georgia, Augusta.

She presented a retrospective cohort study of 10,706 adults who initiated hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for ESRD during 2005-2008, including 1,040 who also had RA. All subjects were drawn from the United States Renal Data System. The impetus for the study, Dr. Peterkin-McCalman explained in an interview, was that although prior studies have established that RA and ESRD are independent risk factors for osteoporotic fractures, the interplay between the two was previously unknown.

The risk of incident osteoporotic fractures during the first 3 years after going on renal dialysis was 14.7% in patients with ESRD only, vaulting to 25.6% in those with comorbid RA. Individuals with both RA and ESRD were at an adjusted 1.83-fold increased overall risk for new fragility fractures and at 1.85-fold increased risk for hip fracture, compared to those without RA.

Far and away the strongest risk factor for incident osteoporotic fractures in the group with RA plus ESRD was a history of a fracture sustained within 5 years prior to initiation of dialysis, with an associated 11.5-fold increased fracture risk overall and an 8.2-fold increased risk of hip fracture.

“The reason that’s important is we don’t really have any medications to reduce fracture risk once you get to ESRD. Of course, we have bisphosphonates and Prolia (denosumab) and things like that, but that’s in patients with milder CKD [chronic kidney disease] or no renal disease at all. So the goal is to identify the patients early who are at higher risk so that we can protect those bones before they get to ESRD and we have nothing left to treat them with,” she said.

In addition to a history of prevalent fracture prior to starting ESRD, the other risk factors for fracture in patients with ESRD and comorbid RA Dr. Peterkin-McCalman identified in her study included age greater than 50 years at the start of dialysis and female gender, which was associated with a twofold greater fracture risk than in men. Black patients with ESRD and RA were 64% less likely than whites to experience an incident fragility fracture. And the fracture risk was higher in patients on hemodialysis than with peritoneal dialysis.

Her study was supported by the Medical College of Georgia and a research grant from Dialysis Clinic Inc.

SOURCE: Peterkin-McCalman R et al. RWCS 2020.

REPORTING FROM RWCS 2020

Refining your approach to hypothyroidism treatment

CASE

A 38-year-old woman presents for a routine physical. Other than urgent care visits for 1 episode of influenza and 2 upper respiratory illnesses, she has not seen a physician for a physical in 5 years. She denies any significant medical history. She takes naproxen occasionally for chronic right knee pain. She does not use tobacco or alcohol. Recently, she has started using a meal replacement shake at lunchtime for weight management. She performs aerobic exercise 30 to 40 minutes per day, 5 days per week. Her family history is significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, arthritis, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia on her mother’s side. She is single, is not currently sexually active, works as a pharmacy technician, and has no children. A high-risk human papillomavirus test was normal 4 years ago.

A review of systems is notable for a 20-pound weight gain over the past year, worsening heartburn over the past 2 weeks, and chronic knee pain, which is greater in the right knee than the left. She denies weakness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, or abdominal pain. Vital signs reveal a blood pressure of 146/88 mm Hg, a heart rate of 63 bpm, a temperature of 98°F (36.7°C), a respiratory rate of 16, a height of 5’7’’ (1.7 m), a weight of 217 lbs (98.4 kg), and a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 99% on room air. The physical exam reveals a body mass index (BMI) of 34, warm dry skin, and coarse brittle hair.

Lab results reveal a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 11.17 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free thyroxine (T4) of 0.58 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). A basic metabolic panel and hemoglobin A1C level are normal.

What would you recommend?

In the United States, the prevalence of overt hypothyroidism (defined as a TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L and a low free T4) among people ≥ 12 years of age was estimated at 0.3% based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999-2002.1 Subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L but < 10 mIU/L and a normal T4 level) is even more common, with an estimated prevalence of 3.4%.1 Hypothyroidism is more common in females and occurs more frequently in Caucasian Americans and Mexican Americans than in African Americans.1

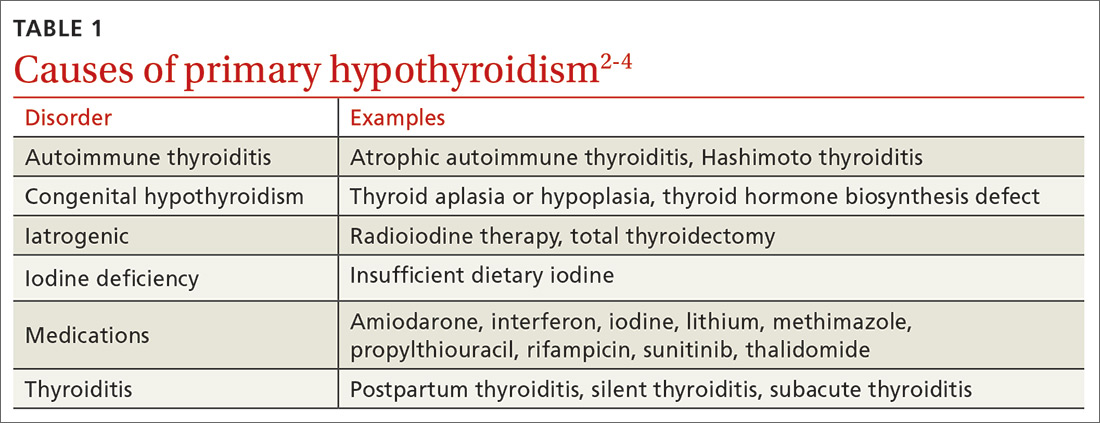

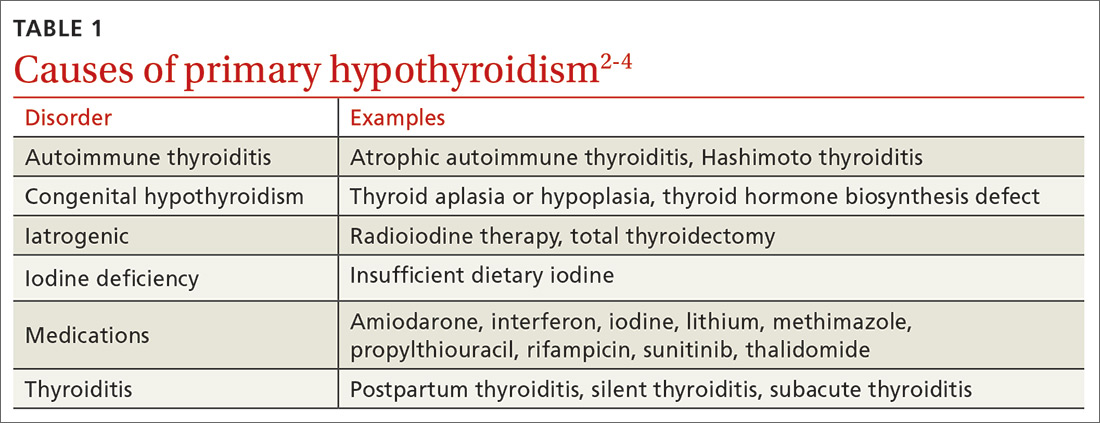

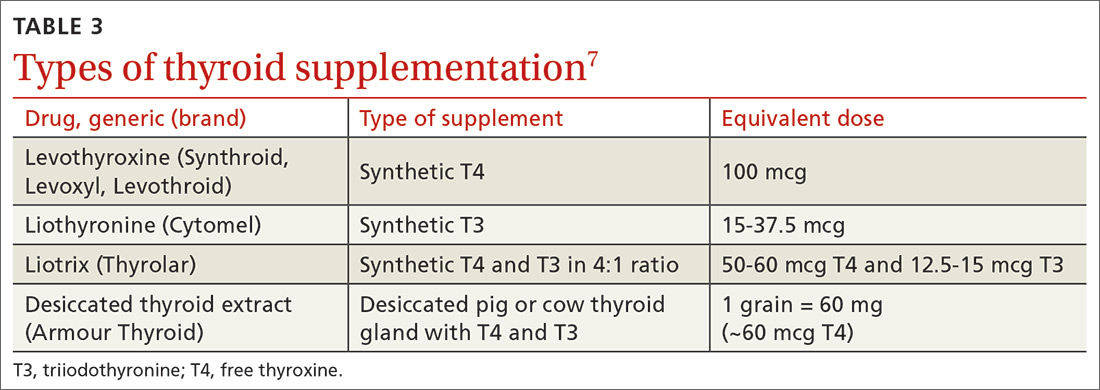

The most common etiologies of hypothyroidism include autoimmune thyroiditis (eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis, atrophic autoimmune thyroiditis) and iatrogenic causes (eg, after radioactive iodine ablation or thyroidectomy) (TABLE 1).2-4

Initiating thyroid hormone replacement

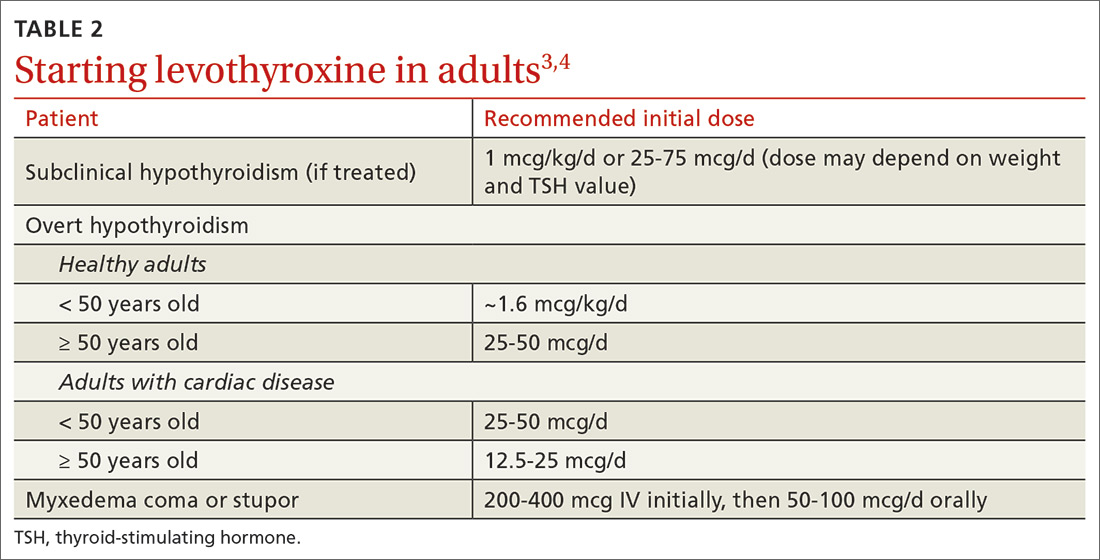

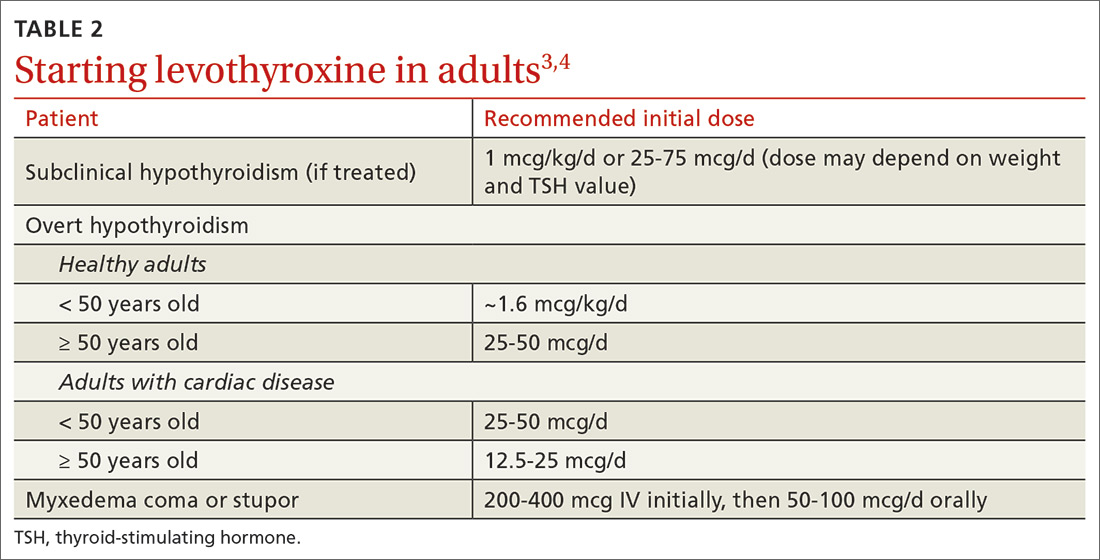

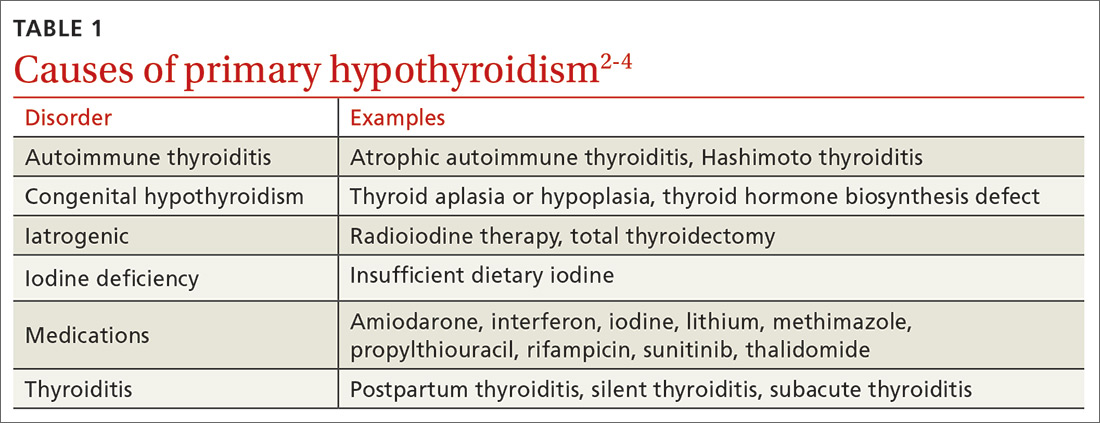

Factors to consider when starting a patient on thyroid hormone replacement include age, weight, symptom severity, TSH level, goal TSH value, adverse effects from thyroid supplements, history of cardiac disease, and, for women of child-bearing age, the desire for pregnancy vs the use of contraceptives. Most adult patients < 50 years with overt hypothyroidism can begin a weight-based dose of levothyroxine: ~1.6 mcg/kg/d (based on ideal body weight).3

Continue to: For adults with cardiac disease...

For adults with cardiac disease, the risk of over-replacement limits initial dosing to 25 to 50 mcg/d for patients < 50 years (12.5-25 mcg/d; ≥ 50 years).3 For adults with subclinical hypothyroidism, it is reasonable to begin therapy at a lower daily dose (eg, 25-75 mcg/d) depending on baseline TSH level, symptoms (the patient may be asymptomatic), and the presence of cardiac disease (TABLE 23,4). Consider treatment in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism particularly when patients have a goiter or dyslipidemia and in women contemplating pregnancy in the near future. Elderly patients may require a dose 20% to 25% lower than younger adults because of decreased body mass.3

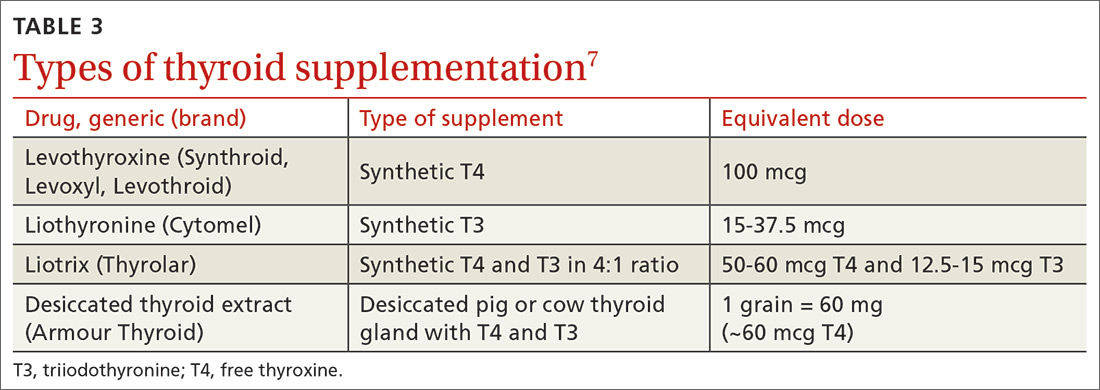

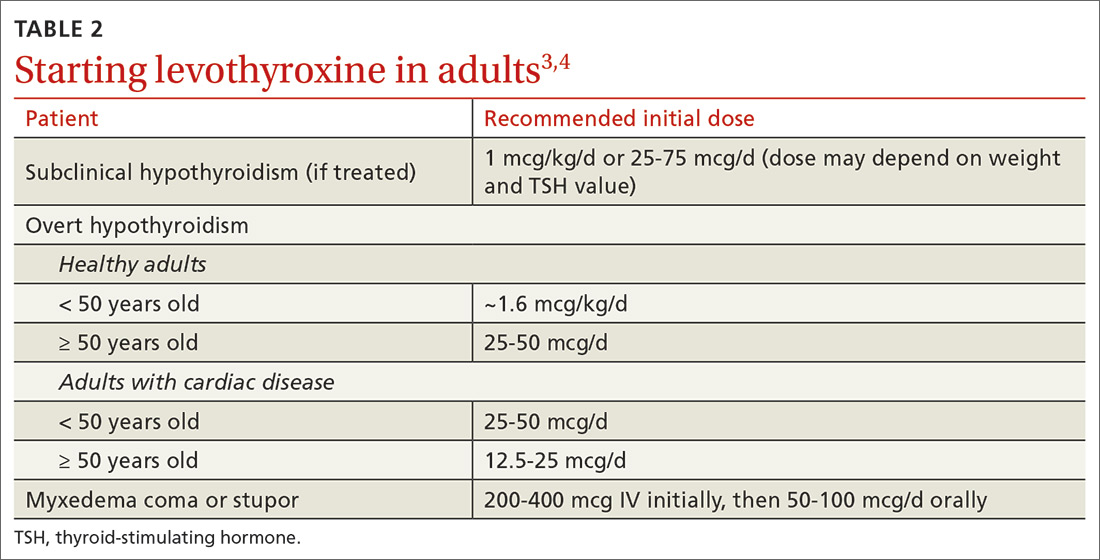

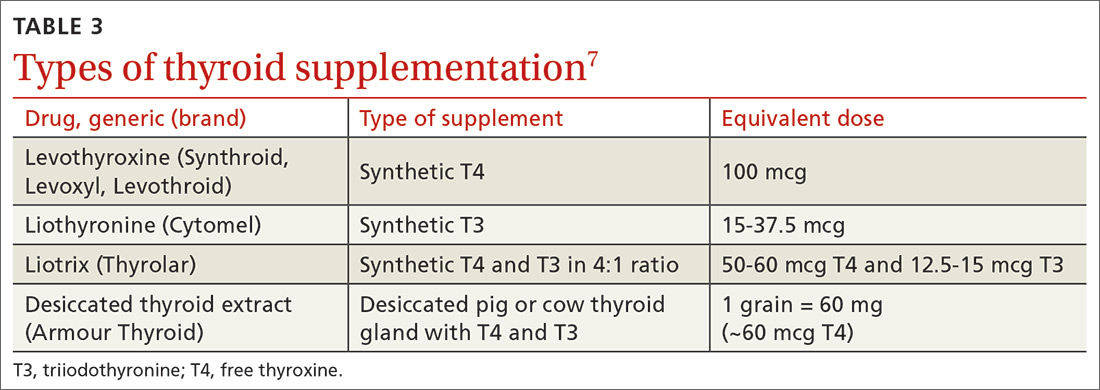

Levothyroxine is considered first-line therapy for hypothyroidism because of its low cost, dose consistency, low risk of allergic reactions, and potential to cause fewer cardiac adverse effects than triiodothyronine (T3) products such as desiccated thyroid extract.5 Although data have not shown an absolute increase in cardiovascular adverse effects, T3 products have a higher T3 vs T4 ratio, giving them a theoretically increased risk.5,6 Desiccated thyroid extract also has been associated with allergic reactions.5

Use of liothyronine alone or in combination with levothyroxine lacks evidence and guideline support.4 Furthermore, it is dosed twice daily, which makes it less convenient, and concerns still exist that there may be an increase in cardiovascular adverse effects.4,6 See TABLE 37 for a summary of available products and their equivalent doses.

Maintaining patients on therapy

The maintenance phase begins once hypothyroidism is diagnosed and treatment is initiated. This phase includes regular monitoring with laboratory studies, office visits, and as-needed adjustments in hormone replacement dosing. The frequency at which all of these occur is variable and based on a number of factors including the patient’s other medical conditions, use of other medications including over-the-counter agents, the patient’s age, weight changes, and pregnancy status.3,4,8 In general, dosage adjustments of 12.5 to 25 mcg can be made at 6- to 8-week intervals based on repeat TSH measurements, patient symptoms, and comorbidities.3

Once a patient is symptomatically stable and laboratory values have normalized, the recommended frequency of laboratory evaluation and office visits is every 12 months, barring significant changes in any of the factors mentioned above. At each visit, physicians should perform medication (including supplements) reconciliation and discuss any health condition updates. Changes to the therapy plan, including frequency or timing of laboratory tests, may be necessary if patients begin taking medications that alter the absorption or function of levothyroxine (eg, steroids).

Continue to: To maximize absorption...

To maximize absorption, providers should review with patients the optimal way to take thyroid hormones. Levothyroxine is approximately 70% to 80% absorbed under ideal conditions, which means taking it in the morning at least 30 to 60 minutes before eating or 3 to 4 hours after the last meal of the day.3,9-13 Of note, TSH levels may increase slightly in patients taking proton pump inhibitors, but this does not usually require a dose increase of thyroid hormone.11 Given that some supplements, particularly iron and calcium, can interfere with absorption, it is recommended to maintain a 3- to 4-hour gap between taking those supplements and taking levothyroxine.12-14 For those patients unable or unwilling to adhere to these recommendations, an increase in levothyroxine dose may be required in order to compensate for the decreased absorption.

Don’t adjust hormone therapy based on clinical presentation alone. While clinical symptoms are important, it is not recommended to adjust hormone therapy based solely on clinical presentation. Common hypothyroid symptoms of dry skin, edema, weight gain, and fatigue may be caused by other medical conditions. While indices including Achilles reflex time and basal metabolic rate have shown some correlation to thyroid dysfunction, there has been limited evidence to show that longitudinal index changes reflect subtle changes in thyroid hormone levels.3

The most recent guidelines from the American Thyroid Association recommend that, “Symptoms should be followed, but considered in the context of serum thyrotropin values, relevant comorbidities, and other potential causes.”3

Special populations/circumstances to keep in mind

Malabsorption conditions. When a higher than expected weight-based dose of levothyroxine is required, physicians should review administration timing, adherence, and comorbid medical conditions that can affect absorption.

Several studies, for example, have demonstrated the impact of Helicobacter pylori gastritis on levothyroxine absorption and subsequent TSH levels.15-17 In one nonrandomized prospective study, patients with H pylori and hypothyroidism who were previously thought to be unresponsive to levothyroxine therapy had a decrease in average TSH level from 30.5 mIU/L to 4.2 mIU/L after H pylori was eradicated.15 Autoimmune atrophic gastritis and celiac disease, both of which are more common in those with other autoimmune diseases, are also associated with the need for higher than expected levothyroxine doses.17,18

Continue to: A history of gastric bypass surgery...

A history of gastric bypass surgery alone is not considered a risk factor for poor absorption of thyroid hormone, given that the majority of levothyroxine absorption occurs in the ileum.19,20 However, advancing age (> 70 years) and extreme obesity (BMI > 40) are independent risk factors for decreased levothyroxine absorption.20,21

Women of reproductive age and pregnant women. Overt untreated or undertreated hypothyroidism can be associated with increased risk of maternal and fetal complications including decreased fertility, miscarriage, preterm delivery, lower birth rates, and infant cognitive deficits.3,22 Therefore, the main focus should be optimization of thyroid hormone levels prior to and during pregnancy.3,4,8,22 Thyroid hormone replacement needs to be increased during pregnancy in approximately 50% to 85% of women using thyroid replacement prior to pregnancy, but the dose requirements vary based on the underlying etiology of thyroid dysfunction.

One initial option for patients on a stable dose before pregnancy is to increase their daily dose by a half tablet (1.5 × daily dose) immediately after home confirmation of pregnancy, until finer dose adjustments (usually increases of 25%-60% ) can be made by a physician. Experts recommend that a TSH level be obtained every 4 weeks until mid-gestation and then at least once around 30 weeks’ gestation to ensure specific targets are being met with dose adjustments.22 Optimal thyrotropin reference ranges during conception and pregnancy can be found in the literature.23

Patients who have positive antibodies and normal thyroid function tests. Patients who are screened for thyroid disorders may demonstrate normal thyroid function (ie, euthyroid) with TSH, free T4, and, if checked, free T3, all within normal ranges. Despite these normal lab results, patients may have additional test results that demonstrate positive thyroid autoantibodies including thyroglobulin antibodies and/or thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Thyroid autoimmunity itself has been associated with a range of other autoimmune conditions as well as an increased risk of thyroid cancer in those with Hashimoto thyroiditis.24 Two studies showed that prophylactic treatment of euthyroid patients with levothyroxine led to a reduction in antibody levels and a lower TSH level.25,26 However, no studies have focused on patient-oriented outcomes such as hospitalizations, quality of life, or symptoms. If the patient remains asymptomatic, we recommend no treatment, but that the patient’s TSH levels be monitored every 12 months.27

Elderly patients. Population data have shown that TSH increases normally with age, with a TSH level of 7.5 mIU/L being the upper limit of normal for a population of healthy adults > 80 years of age.28,29 Overall, studies have failed to show any benefit in treating elderly patients with subclinical hypothyroidism unless their TSH level exceeds 10 mIU/L.6,21 The one exception is elderly patients with heart failure in whom untreated subclinical hypothyroidism has been shown to be associated with higher mortality.30

Continue to: Elderly patients are at higher risk...

Elderly patients are at higher risk for adverse effects of thyroid over-replacement, including atrial fibrillation and osteoporosis. While there have been no randomized trials examining target TSH levels in this population, a reasonable recommendation is a goal TSH level of 4 to 6 mIU/L for elderly patients ≥ 70 years.4

CASE

As a result of the patient’s elevated TSH level and symptoms of hypothyroidism, you start levothyroxine 150 mcg/d by mouth, counsel her on potential adverse effects, and schedule a follow-up visit with another TSH check in 6 weeks.

Follow-up laboratory studies 6 weeks later reveal a TSH level of 5.86 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free T4 level of 0.74 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). Based on those results, you increase the dose of levothyroxine to 175 mcg/d.

At her follow-up visit 12 weeks after initial presentation, her TSH level is 3.85 mIU/L. She reports feeling better overall with less fatigue, and she has lost 5 pounds since her last visit. You recommend she continue levothyroxine 175 mcg/d after reviewing medication compliance with the patient and ensuring she is indeed taking it in the morning, at least 30 minutes prior to eating. With improved but not resolved symptoms, she agrees to follow-up with repeat TSH laboratory studies in 6 weeks to determine whether further dose adjustments are necessary. Given that she is of reproductive age and her TSH level is suboptimal for pregnancy, you caution her about heightened pregnancy/fetal risks with a suboptimal TSH and recommend that she use reliable contraception.

CORRESPONDENCE

Christopher Bunt, MD, FAAFP, 5 Charleston Center Drive, Suite 263, MSC 192,Charleston, SC 29425; [email protected]