User login

Where Have All the Future Veterans Gone?

Word to the Nation: Guard zealously your right to serve in the Armed Forces, for without them, there will be no other rights to guard.

John F. Kennedy 1

The title of this Veterans Day editorial is a paraphrase of the legendary folk artist Pete Seeger’s protest song popularized during the Vietnam War. On January 27, 1973, in the wake of the widespread antiwar movement, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird announced an end to the dreaded draft.2

For nearly 50 years, the all-volunteer military was celebrated as an outstanding achievement that professionalized the armed services and arguably made the US military among the most highly trained and effective fighting forces in the world. That was until an ongoing recruitment crisis threatened to write a different and far more disturbing conclusion to what the government had heralded as a “success story.”3

The recruiting crisis is a complicated problem with many facets that have received increasing attention from journalists, the media, experts, think tanks, and the government. Given this complexity, this will be a 2-part editorial: This column examines the scope of the crisis and the putative causes of the problem with recruiting Americans to serve in uniform. The next column will examine the potential impact of the shortage of service members on federal health care practice.

The Recruiting Crisis

Over the past several years, nearly every branch of the armed forces has struggled with recruitment, especially the Army. In April of this year, the US Department of Defense (DoD) reported that the Army, Navy, and Air Force would all fail to meet recruitment goals; only the Marines and Space Forces were expected to reach their targets.4 At the end of its fiscal year (October 1), the Army acknowledged that its 55,000 recruits were 10,000 fewer soldiers than it had aimed to enlist.5 But this was still more people joining the ranks than in 2022 when the Army was 15,000 recruits below the mark.6

Challenging Trends

There are many putative causes and proposed solutions for the recruitment crisis. Among the most serious is a marked drop in the American public’s confidence in the military. A June 2023 Gallup poll found that only 60% of citizens expressed “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military. This was the nadir of a 5-year decline that this year reached the lowest point since 1997/1998.7 For many Americans in and out of uniform, the ignoble end to the long war in Afghanistan leaving behind friends and allies contrary to the military ethos is cited as a significant contributor to both the loss of confidence in the military and the recruiting crisis.8

These cultural developments reinforce each other. Now, many veterans do not want their relatives and friends to follow them into the armed services. A 2021 survey by the Military Family Advisory Network found that slightly more than 60% of veterans and active-duty service members would recommend a military career to a potential recruit. This was down from 75% in 2019.9 Veterans cite a variety of reasons for discouraging their fellow citizens from serving, including low pay compared with civilian employment, especially in a labor-hungry job market; and the military failure to fulfill health care promises, housing, and other social services, especially for the growing number experiencing mental health disorders related to their service.10

Two facts about recruitment heighten the negative impact of some veterans’ change of attitude toward joining the services. First, since the end of the draft, military life in the US has become a family tradition. Published in 2011, a Pew Research Center study found that even then, a decreasing number of Americans had a family connection to the military. More respondents aged ≥ 50 years had a parent, child, spouse, or sibling who had served compared with those aged 30 to 49 years and those aged 18 to 29 (77%, 57%, and 33%, respectively).11 Second, since the end of the draft, far fewer Americans have had military experience. Only 1% of the nation is currently in military service, and the veteran population is steadily declining. In 1980, 18% of adult Americans were veterans; 20 years later, that number is only 7%.12 This makes it less likely that a high school or college student will have a personal or even a passing relationship with a teacher, coach, or other mentoring adult who is or has been a military member. This demographic discrepancy has generated what sociologists call the military-civilian gap.10 That division has been manipulated in the increasingly vehement culture wars and generational struggles that are splitting the country.12

This relatively recent sociological trend is reflected in a growing lack of interest among many young Americans in armed forces service. A DoD survey of participants aged 16 to 24 years regarding their intention to serve in the military found that 89% were probably not going to pursue a career in uniform. More than 65% of respondents indicated that the possibility of physical injury, death, or psychological trauma was the primary deterrent for considering enlisting.13 The latter barrier is directly related to our work as practitioners caring for service members and veterans, and through our compassion and competence, we may help bridge the widening divide between the military and civilian spheres. These numbers speak to the unwilling; there is also a significant group of Americans who want to serve yet are unable to due to their history, diagnoses, or condition.14 Their motivation to be military members in the face of the recruitment challenges highlighted here present federal practitioners with ethical questions that will be the subject of the next column.

Armed Forces and Veterans Day

This column’s epigraph is from President John F. Kennedy, a decorated World War II Navy combat veteran who decreed Armed Forces Day an official holiday a decade before conscription ended.1 The commemoration was to thank and honor all individuals currently serving in the military for their patriotism and sacrifice. President Kennedy’s Word to the Nation could not be timelier on Veterans Day 2023. The data reviewed here raise profound questions as to where tomorrow’s service members and the veterans of the future will come from, and how we will persuade them that though there are real risks to military service, the rewards are both tangible and transcendent.

1. US Department of Defense. Armed Forces Day. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://afd.defense.gov/History

2. Zipkin A. The military draft ended 50 years ago, dividing a generation. The Washington Post. January 27, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/01/27/draft-end-conscription-1973

3. Lopez TC. All-volunteer force proves successful for U.S. military. March 2, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3316678/all-volunteer-force-proves-successful-for-us-military

4. Garamone J. Vice-chiefs talk recruiting shortfalls, readiness issues. April 20, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3369472/vice-chiefs-talk-recruiting-shortfalls-readiness-issues

5. Winkie D. Army recruiters at two-thirds of contract goals as the fiscal year closes. Military Times. September 7, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.armytimes.com/news/recruiting/2023/09/07/army-recruiters-at-two-thirds-of-contract-goals-as-fiscal-year-closes

6. Baldor LC. Army misses recruiting goal by 15,000 soldiers. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2022/10/02/army-misses-recruiting-goal-by-15000-soldiers

7. Younis M. Confidence in U.S. military lowest in over two decades. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://news.gallup.com/poll/509189/confidence-military-lowest-two-decades.aspx

8. Rogin A, Corkery A. Why recruiting and confidence in America’s armed forces is so low right now? Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/why-recruiting-and-confidence-in-americas-armed-forces-is-so-low-right-now

9. Military Family Advisory Network. 2021 military family support programming survey. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.mfan.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Executive-Summary-MFAN-Programming-Survey-Results-2021.pdf

10. Kesling B. The military recruiting crisis: even veterans don’t want their family to join. Wall Street Journal. 30 June 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/military-recruiting-crisis-veterans-dont-want-their-children-to-join-510e1a25

11. Pew Research Center. The military-civilian gap: fewer family connections. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/11/23/the-military-civilian-gap-fewer-family-connections

12. Myers M. Is the military too ‘woke’ to recruit? Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2022/10/13/is-the-military-too-woke-to-recruit

13. Schaeffer K. The changing face of America’s veteran population. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/05/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population

14. Phillips D. With few able and fewer willing, U.S. military can’t find recruits. New York Times. July 14, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/14/us/us-military-recruiting-enlistment.html

Word to the Nation: Guard zealously your right to serve in the Armed Forces, for without them, there will be no other rights to guard.

John F. Kennedy 1

The title of this Veterans Day editorial is a paraphrase of the legendary folk artist Pete Seeger’s protest song popularized during the Vietnam War. On January 27, 1973, in the wake of the widespread antiwar movement, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird announced an end to the dreaded draft.2

For nearly 50 years, the all-volunteer military was celebrated as an outstanding achievement that professionalized the armed services and arguably made the US military among the most highly trained and effective fighting forces in the world. That was until an ongoing recruitment crisis threatened to write a different and far more disturbing conclusion to what the government had heralded as a “success story.”3

The recruiting crisis is a complicated problem with many facets that have received increasing attention from journalists, the media, experts, think tanks, and the government. Given this complexity, this will be a 2-part editorial: This column examines the scope of the crisis and the putative causes of the problem with recruiting Americans to serve in uniform. The next column will examine the potential impact of the shortage of service members on federal health care practice.

The Recruiting Crisis

Over the past several years, nearly every branch of the armed forces has struggled with recruitment, especially the Army. In April of this year, the US Department of Defense (DoD) reported that the Army, Navy, and Air Force would all fail to meet recruitment goals; only the Marines and Space Forces were expected to reach their targets.4 At the end of its fiscal year (October 1), the Army acknowledged that its 55,000 recruits were 10,000 fewer soldiers than it had aimed to enlist.5 But this was still more people joining the ranks than in 2022 when the Army was 15,000 recruits below the mark.6

Challenging Trends

There are many putative causes and proposed solutions for the recruitment crisis. Among the most serious is a marked drop in the American public’s confidence in the military. A June 2023 Gallup poll found that only 60% of citizens expressed “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military. This was the nadir of a 5-year decline that this year reached the lowest point since 1997/1998.7 For many Americans in and out of uniform, the ignoble end to the long war in Afghanistan leaving behind friends and allies contrary to the military ethos is cited as a significant contributor to both the loss of confidence in the military and the recruiting crisis.8

These cultural developments reinforce each other. Now, many veterans do not want their relatives and friends to follow them into the armed services. A 2021 survey by the Military Family Advisory Network found that slightly more than 60% of veterans and active-duty service members would recommend a military career to a potential recruit. This was down from 75% in 2019.9 Veterans cite a variety of reasons for discouraging their fellow citizens from serving, including low pay compared with civilian employment, especially in a labor-hungry job market; and the military failure to fulfill health care promises, housing, and other social services, especially for the growing number experiencing mental health disorders related to their service.10

Two facts about recruitment heighten the negative impact of some veterans’ change of attitude toward joining the services. First, since the end of the draft, military life in the US has become a family tradition. Published in 2011, a Pew Research Center study found that even then, a decreasing number of Americans had a family connection to the military. More respondents aged ≥ 50 years had a parent, child, spouse, or sibling who had served compared with those aged 30 to 49 years and those aged 18 to 29 (77%, 57%, and 33%, respectively).11 Second, since the end of the draft, far fewer Americans have had military experience. Only 1% of the nation is currently in military service, and the veteran population is steadily declining. In 1980, 18% of adult Americans were veterans; 20 years later, that number is only 7%.12 This makes it less likely that a high school or college student will have a personal or even a passing relationship with a teacher, coach, or other mentoring adult who is or has been a military member. This demographic discrepancy has generated what sociologists call the military-civilian gap.10 That division has been manipulated in the increasingly vehement culture wars and generational struggles that are splitting the country.12

This relatively recent sociological trend is reflected in a growing lack of interest among many young Americans in armed forces service. A DoD survey of participants aged 16 to 24 years regarding their intention to serve in the military found that 89% were probably not going to pursue a career in uniform. More than 65% of respondents indicated that the possibility of physical injury, death, or psychological trauma was the primary deterrent for considering enlisting.13 The latter barrier is directly related to our work as practitioners caring for service members and veterans, and through our compassion and competence, we may help bridge the widening divide between the military and civilian spheres. These numbers speak to the unwilling; there is also a significant group of Americans who want to serve yet are unable to due to their history, diagnoses, or condition.14 Their motivation to be military members in the face of the recruitment challenges highlighted here present federal practitioners with ethical questions that will be the subject of the next column.

Armed Forces and Veterans Day

This column’s epigraph is from President John F. Kennedy, a decorated World War II Navy combat veteran who decreed Armed Forces Day an official holiday a decade before conscription ended.1 The commemoration was to thank and honor all individuals currently serving in the military for their patriotism and sacrifice. President Kennedy’s Word to the Nation could not be timelier on Veterans Day 2023. The data reviewed here raise profound questions as to where tomorrow’s service members and the veterans of the future will come from, and how we will persuade them that though there are real risks to military service, the rewards are both tangible and transcendent.

Word to the Nation: Guard zealously your right to serve in the Armed Forces, for without them, there will be no other rights to guard.

John F. Kennedy 1

The title of this Veterans Day editorial is a paraphrase of the legendary folk artist Pete Seeger’s protest song popularized during the Vietnam War. On January 27, 1973, in the wake of the widespread antiwar movement, Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird announced an end to the dreaded draft.2

For nearly 50 years, the all-volunteer military was celebrated as an outstanding achievement that professionalized the armed services and arguably made the US military among the most highly trained and effective fighting forces in the world. That was until an ongoing recruitment crisis threatened to write a different and far more disturbing conclusion to what the government had heralded as a “success story.”3

The recruiting crisis is a complicated problem with many facets that have received increasing attention from journalists, the media, experts, think tanks, and the government. Given this complexity, this will be a 2-part editorial: This column examines the scope of the crisis and the putative causes of the problem with recruiting Americans to serve in uniform. The next column will examine the potential impact of the shortage of service members on federal health care practice.

The Recruiting Crisis

Over the past several years, nearly every branch of the armed forces has struggled with recruitment, especially the Army. In April of this year, the US Department of Defense (DoD) reported that the Army, Navy, and Air Force would all fail to meet recruitment goals; only the Marines and Space Forces were expected to reach their targets.4 At the end of its fiscal year (October 1), the Army acknowledged that its 55,000 recruits were 10,000 fewer soldiers than it had aimed to enlist.5 But this was still more people joining the ranks than in 2022 when the Army was 15,000 recruits below the mark.6

Challenging Trends

There are many putative causes and proposed solutions for the recruitment crisis. Among the most serious is a marked drop in the American public’s confidence in the military. A June 2023 Gallup poll found that only 60% of citizens expressed “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military. This was the nadir of a 5-year decline that this year reached the lowest point since 1997/1998.7 For many Americans in and out of uniform, the ignoble end to the long war in Afghanistan leaving behind friends and allies contrary to the military ethos is cited as a significant contributor to both the loss of confidence in the military and the recruiting crisis.8

These cultural developments reinforce each other. Now, many veterans do not want their relatives and friends to follow them into the armed services. A 2021 survey by the Military Family Advisory Network found that slightly more than 60% of veterans and active-duty service members would recommend a military career to a potential recruit. This was down from 75% in 2019.9 Veterans cite a variety of reasons for discouraging their fellow citizens from serving, including low pay compared with civilian employment, especially in a labor-hungry job market; and the military failure to fulfill health care promises, housing, and other social services, especially for the growing number experiencing mental health disorders related to their service.10

Two facts about recruitment heighten the negative impact of some veterans’ change of attitude toward joining the services. First, since the end of the draft, military life in the US has become a family tradition. Published in 2011, a Pew Research Center study found that even then, a decreasing number of Americans had a family connection to the military. More respondents aged ≥ 50 years had a parent, child, spouse, or sibling who had served compared with those aged 30 to 49 years and those aged 18 to 29 (77%, 57%, and 33%, respectively).11 Second, since the end of the draft, far fewer Americans have had military experience. Only 1% of the nation is currently in military service, and the veteran population is steadily declining. In 1980, 18% of adult Americans were veterans; 20 years later, that number is only 7%.12 This makes it less likely that a high school or college student will have a personal or even a passing relationship with a teacher, coach, or other mentoring adult who is or has been a military member. This demographic discrepancy has generated what sociologists call the military-civilian gap.10 That division has been manipulated in the increasingly vehement culture wars and generational struggles that are splitting the country.12

This relatively recent sociological trend is reflected in a growing lack of interest among many young Americans in armed forces service. A DoD survey of participants aged 16 to 24 years regarding their intention to serve in the military found that 89% were probably not going to pursue a career in uniform. More than 65% of respondents indicated that the possibility of physical injury, death, or psychological trauma was the primary deterrent for considering enlisting.13 The latter barrier is directly related to our work as practitioners caring for service members and veterans, and through our compassion and competence, we may help bridge the widening divide between the military and civilian spheres. These numbers speak to the unwilling; there is also a significant group of Americans who want to serve yet are unable to due to their history, diagnoses, or condition.14 Their motivation to be military members in the face of the recruitment challenges highlighted here present federal practitioners with ethical questions that will be the subject of the next column.

Armed Forces and Veterans Day

This column’s epigraph is from President John F. Kennedy, a decorated World War II Navy combat veteran who decreed Armed Forces Day an official holiday a decade before conscription ended.1 The commemoration was to thank and honor all individuals currently serving in the military for their patriotism and sacrifice. President Kennedy’s Word to the Nation could not be timelier on Veterans Day 2023. The data reviewed here raise profound questions as to where tomorrow’s service members and the veterans of the future will come from, and how we will persuade them that though there are real risks to military service, the rewards are both tangible and transcendent.

1. US Department of Defense. Armed Forces Day. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://afd.defense.gov/History

2. Zipkin A. The military draft ended 50 years ago, dividing a generation. The Washington Post. January 27, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/01/27/draft-end-conscription-1973

3. Lopez TC. All-volunteer force proves successful for U.S. military. March 2, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3316678/all-volunteer-force-proves-successful-for-us-military

4. Garamone J. Vice-chiefs talk recruiting shortfalls, readiness issues. April 20, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3369472/vice-chiefs-talk-recruiting-shortfalls-readiness-issues

5. Winkie D. Army recruiters at two-thirds of contract goals as the fiscal year closes. Military Times. September 7, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.armytimes.com/news/recruiting/2023/09/07/army-recruiters-at-two-thirds-of-contract-goals-as-fiscal-year-closes

6. Baldor LC. Army misses recruiting goal by 15,000 soldiers. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2022/10/02/army-misses-recruiting-goal-by-15000-soldiers

7. Younis M. Confidence in U.S. military lowest in over two decades. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://news.gallup.com/poll/509189/confidence-military-lowest-two-decades.aspx

8. Rogin A, Corkery A. Why recruiting and confidence in America’s armed forces is so low right now? Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/why-recruiting-and-confidence-in-americas-armed-forces-is-so-low-right-now

9. Military Family Advisory Network. 2021 military family support programming survey. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.mfan.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Executive-Summary-MFAN-Programming-Survey-Results-2021.pdf

10. Kesling B. The military recruiting crisis: even veterans don’t want their family to join. Wall Street Journal. 30 June 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/military-recruiting-crisis-veterans-dont-want-their-children-to-join-510e1a25

11. Pew Research Center. The military-civilian gap: fewer family connections. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/11/23/the-military-civilian-gap-fewer-family-connections

12. Myers M. Is the military too ‘woke’ to recruit? Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2022/10/13/is-the-military-too-woke-to-recruit

13. Schaeffer K. The changing face of America’s veteran population. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/05/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population

14. Phillips D. With few able and fewer willing, U.S. military can’t find recruits. New York Times. July 14, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/14/us/us-military-recruiting-enlistment.html

1. US Department of Defense. Armed Forces Day. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://afd.defense.gov/History

2. Zipkin A. The military draft ended 50 years ago, dividing a generation. The Washington Post. January 27, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/01/27/draft-end-conscription-1973

3. Lopez TC. All-volunteer force proves successful for U.S. military. March 2, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3316678/all-volunteer-force-proves-successful-for-us-military

4. Garamone J. Vice-chiefs talk recruiting shortfalls, readiness issues. April 20, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3369472/vice-chiefs-talk-recruiting-shortfalls-readiness-issues

5. Winkie D. Army recruiters at two-thirds of contract goals as the fiscal year closes. Military Times. September 7, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.armytimes.com/news/recruiting/2023/09/07/army-recruiters-at-two-thirds-of-contract-goals-as-fiscal-year-closes

6. Baldor LC. Army misses recruiting goal by 15,000 soldiers. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.armytimes.com/news/your-army/2022/10/02/army-misses-recruiting-goal-by-15000-soldiers

7. Younis M. Confidence in U.S. military lowest in over two decades. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://news.gallup.com/poll/509189/confidence-military-lowest-two-decades.aspx

8. Rogin A, Corkery A. Why recruiting and confidence in America’s armed forces is so low right now? Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/why-recruiting-and-confidence-in-americas-armed-forces-is-so-low-right-now

9. Military Family Advisory Network. 2021 military family support programming survey. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.mfan.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Executive-Summary-MFAN-Programming-Survey-Results-2021.pdf

10. Kesling B. The military recruiting crisis: even veterans don’t want their family to join. Wall Street Journal. 30 June 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/military-recruiting-crisis-veterans-dont-want-their-children-to-join-510e1a25

11. Pew Research Center. The military-civilian gap: fewer family connections. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/11/23/the-military-civilian-gap-fewer-family-connections

12. Myers M. Is the military too ‘woke’ to recruit? Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2022/10/13/is-the-military-too-woke-to-recruit

13. Schaeffer K. The changing face of America’s veteran population. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2021/04/05/the-changing-face-of-americas-veteran-population

14. Phillips D. With few able and fewer willing, U.S. military can’t find recruits. New York Times. July 14, 2023. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/14/us/us-military-recruiting-enlistment.html

How VA Innovative Partnerships and Health Care Systems Can Respond to National Needs: NOSE Trial Example

Traditional manufacturing concentrates capacity into a few discrete locations while applying lean and just-in-time philosophies to maximize profit during times of somewhat predictable supply and demand. This approach exposed nationwide vulnerabilities even during local crises, such as the United States saline shortages following closure of a single plant in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria in 2017.1 Interruptions to the supply chain due to pandemic plant closure, weather, politics, or surge demand can cause immediate and lasting shortages. Nasal swabs were a clear example.

At the onset of COVID-19, 2 companies—Puritan in Guilford, Maine, and Copan in Italy—manufactured nearly all of the highly specialized nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs singled out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to test patients for COVID-19. Demand for swabs skyrocketed as the virus spread, and they became unattainable. The lack of swabs meant patients went undiagnosed. Without knowing who was positive, people with symptoms and known contacts were presumed positive and quarantined, impacting isolated patients, the health care professionals treating them, and the entire US economy.

3-Dimensional Printing Solutions

Manufacturing NP swabs is not trivial. Their simple shape conceals complexity and requires highly specialized equipment. The lead time for one non-US machine manufacturer was > 6 months at the start of the pandemic.

Digital manufacturing/3-dimensional (3D) printing represented a potential solution to the supply chain crisis.2 Designers created digital blueprints for 3D-printed goods, face masks, face shields, and ventilator splitters were rapidly created and shared.3,4 Scrambling to fill the critical need for NP swabs, many hospitals, businesses, and academic centers began 3D printing swabs. This effort was spearheaded by University of South Florida (USF) and Northwell Health researchers and clinicians, who designed and tested a 3D-printed NP swab from photocurable resin that was printable on 2 models of Formlabs printers.5 Several other 3D-printed NP swab designs soon followed. This innovation and problem-solving renaissance faced several challenges well known to traditional manufacturers of regulated products but novel to newcomers.

The first challlenge was that these NP swabs predate FDA oversight of medical device development and manufacturing and no testing standards existed. Designers began casting prototypes out without guidance about the critical features and clinical functions required. Many of these designs did not have a clinical evaluation pathway to test safety and efficacy.

The second challlenge was that these swabs were being produced by facilities not registered with the FDA. This raised concerns about the quality of unlisted medical products developed and manufactured at novel facilities.

The third challenge was that small-scale novel approaches may offset local shortages but could not address national needs. The self-organized infrastructure for this crisis was ad hoc, local, and lacked coordinated federal support. This led to rolling shortages of these materials for years.

Two studies were performed early in the pandemic. The first study evaluated 4 prototypes of different manufacturer designs, finding excellent concordance among them and their control swab.6 A second study demonstrated the USF swab to be noninferior to the standard of care.7 Both studies acknowledged and addressed the first challenge for their designs.

COLLABORATIONS

Interagency

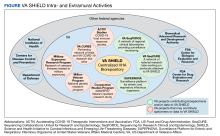

Before the pandemic, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had been coordinating with the FDA, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the nonprofit America Makes to bring medical product development and manufacturing closer to the point of care.

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the collaboration was formalized to address new challenges.8 The objectives of this collaboration were the following: (1) host a digital repository for 3D-printed digital designs for personal protectice equipment and other medical supplies in or at risk of shortage; (2) provide scientifically based ratings for designs according to clinical and field testing; and (3) offer education to health care workers and the public about the digital manufacturing of medical goods and devices.4,9

A key output of this collaboration was the COVID 3D Trusted Repository For Users And Suppliers Through Testing (COVID 3D TRUST), a curated archive of designs. In most cases, existing FDA standards and guidance formed the basis of testing strategies with deviations due to limited access to traditional testing facilities and reagents.

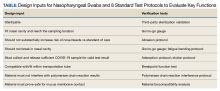

To address novel NP swabs, working with its COVID 3D TRUST partners, the VA gathered a combined list of clinical- and engineering-informed customer requirements and performed a hazard analysis. The result was a list of design inputs for NP swabs and 8 standard test protocols to evaluate key functions (Table).10 These protocols are meant to benchmark novel 3D-printed swabs against the key functions of established, traditionally manufactured swabs, which have a long record of safety and efficacy. The protocols, developed by the VA and undergoing validation by the US Army, empower and inform consumers and provide performance metrics to swab designers and manufacturers. The testing protocols and preliminary test results developed by the VA are publicly available at the NIH.11

Intra-agency

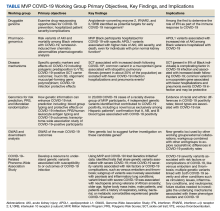

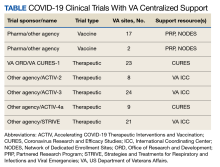

The use of the inputs and verification tests noted in the Table may reduce the risk of poor design but were inadequate to evaluate the clinical safety and efficacy of novel swabs. Recognizing this, the VA Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning (OHIL) and the Office of Research and Development (ORD) launched the Nasal Swab Objective and Statistical Evaluation (NOSE) study to formally evaluate the safety and efficacy of 3D-printed swabs in the field. This multisite clinical study was a close collaboration between the OHIL and ORD. The OHIL provided the quality system and manufacturing oversight and delivery of the swabs, and the ORD provided scientific review, research infrastructure, human subjects oversight, administrative support, and funding and fiscal oversight. The OHIL/ORD collaboration resulted in the successful completion of the NOSE study.

This study (manuscript under preparation) yielded two 3D-printing production processes and swab designs that had comparable performance to the standard of care, were manufacturable compliant with FDA guidelines, and could be produced at scale in a distributed manner. This approach directly addressed the 3 challenges described earlier.

LESSONS LEARNED

Swabs were an example of supply challenges in the pandemic, but advanced manufacturing (notably, digital designs leading to 3D-printed solutions) also served as a temporary solution to device and product shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital designs and 3D printing as manufacturing techniques have the following key advantages: (1) they are distributed in nature, both in the breadth of locations that have access to these manufacturing platforms and in the depth of material choice that can be used to fabricate products, which alleviates the threat of a disaster impacting manufacturing capacity or a material stream; (2) they do not require retooling of machinery so new products can deploy rapidly and on demand; and (3) the speed of digital iteration, printing, and revision allows for rapid product development and production.

There also are notable disadvantages to these techniques. First, because 3D printing is a newer technology, there is less general depth of knowledge regarding design and material choice for additive manufacturing. Second, the flexibility of 3D printing means that operators must increase awareness of the factors that might cause the fabrication of a part to fail in either printing or postprocessing. Third, there are significant gaps in understanding how materials and manufacturing processes will perform in high-stakes settings such as health care, where performance and biocompatibility may be critical to support life-sustaining functions. Fourth, digital files are vulnerable to intentional or unintentional alteration. These alterations might weaken design integrity and be imperceptible to the manufacturer or end user. This is a prevalent challenge in all open-source designs.

The pandemic materialized quickly and created vast supply chain challenges. To address this crisis, it was clear that the average 17-year interval between research and translation in the US was unacceptable. The VA was able to accelerate swiftly many existing processes to meet this need, build new capabilities, and establish new practices for the rapid evaluation and deployment of health care products and guidance. This agile and innovative cooperation was critical in the success of the VA’s national support for pandemic solutions.

Finally, although COVID 3D TRUST was able to provide testing of submitted designs, this collaboration was not a substitute for the “peacetime” process of manufacturing site registration with the FDA and product listing. COVID 3D TRUST could evaluate designs only, not the production process, safety, and efficacy.

CALLS TO ACTION

The pandemic's impact on medical supply chain security persists, as does the need for greater foresight and crisis preparation. We must act now to avoid experiencing again the magnitude of fatalities (civilian and veteran) and the devastation to the US economy and livelihoods that occurred during this single biological event. To this end, creating a digital stockpile of federally curated, crisis-ready designs for as-needed distribution across our US industrial base would offer a second line of defense against life-threatening supply chain interruptions. The realization of such a digital stockpile requires calls to action among multiple contributors.

Collaborations

The VA’s Fourth Mission is to improve the nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters. The VA does this by developing plans and taking actions to ensure continued service to veterans, as well as to support national, state, and local emergency management, public health, safety, and homeland security efforts.

The VA partnership with the FDA and NIH during the pandemic enabled successful coordination among federal agencies. Numerous other agencies, including the US Department of Defense (DoD), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), also developed and executed successful initiatives.12-14 The joint awareness and management of these efforts, however, could be strengthened through more formal agreements and processes in peacetime. The VA/FDA/NIH Memorandum of Understanding is a prototype example of each agency lending its subject matter expertise to address a host of pandemic challenges collectively, cooperatively, and efficiently.8

Public-private partnerships (eg, VA/FDA/NIH and America Makes) led to coordinated responses for crisis readiness. The Advanced Manufacturing Crisis Product Response Program, a multipartner collaboration that included VA, addressed 7 crisis scenarios, 3 of which were specifically related to COVID-19.15 In addition, both BARDA and DARPA had successful public-private collaborations, and the DoD supported national logistics and other efforts.12-14 Clearly, industry and government both recognize complementary synergies: (1) the depth of resources of US industry; and (2) the national resources, coordination, and clinical insight available through federal agencies that can address the challenges of future crises quickly and efficiently.

When traditional supply chains and manufacturing processes failed during the pandemic, new techniques were exploited to fill the unmet material needs. Novel techniques and product pathways, however, are untested or undeveloped. The collaboration between the ORD and OHIL in support of NP swab testing and production is an example of bringing research insight, regulated product development, and manufacturing together to support a complete product life cycle.

Joint Awareness and Management

The VA continues to refine the joint awareness and management (JAM) process of products from ideation to translation, to shorten the time from research to product delivery. JAM is a VA collaborative committee of partners from ORD research offices and technology transfer program, and the OHIL Office of Advanced Manufacturing, which seeks additional support and guidance from VHA clinical service lines, VA Office of General Council, and VA Office of Acquisitions, Logistics, and Construction.

This team enables the rapid identification of unmet veteran health care product needs. In addition, JAM leverages the resources of each group to support products from problem identification to solution ideation, regulated development, production, and delivery into clinical service lines. While the concept of JAM arose to meet the crisis needs of the pandemic, it persists in delivering advanced health care solutions to veterans.

A Proposed Plan

The next national crisis is likely to involve and threaten national health care security. We propose that federal agencies be brought together to form a federally supported digital stockpile. This digital stockpile must encompass, at minimum, the following features: (1) preservation of novel, scalable medical supplies and products generated during the COVID-19 pandemic, to avoid the loss of this work; (2) clinical maturation of those existing supplies and products to refine their features and functions under the guidance of clinical, regulatory, and manufacturing experts—and validate those outputs with clinical evidence; (3) manufacturing maturation of those existing supplies and products, such that complete design and production processes are developed with the intent to distribute to multiple public manufacturers during the next crisis; (4) a call for new designs/intake portal for new designs to be matured and curated as vulnerabilities are identified; (5) supply chain crisis drills executed to test public-private preparedness to ensure design transfer is turnkey and can be engaged quickly during the next crisis; and (6) public-private engagement to develop strategy, scenarios, and policy to ensure that when supply chains next fail, additional surge capacity can be quickly added to protect American lives and health care, and that when supply chains resume, surge capacity can be redirected or stood down to protect the competitive markets.

This digital stockpile can complement and be part of the Strategic National Stockpile. Whereas the Strategic National Stockpile is a reserve of physical products that may offset product shortages, the digital stockpile is a reserve of turnkey, transferable designs that may offset supply chain disruptions and production-capacity shortages.

CONCLUSIONS

The success of 3D-printed NP swabs is a specific example of the importance of collaborations across industry, government, innovators, and researchers. More important than a sole product, however, these collaborations demonstrated the potential for game-changing approaches to how public-private partnerships support the continuity of health care operations nationally and prevent the potential for unnecessary loss of life due to capacity and supply chain disruptions.

As the largest health care system in the US, the VA has a unique capability to lead in the assessment of other novel 3D-printed medical devices in partnership with the FDA. The VA has a unique patient-centered perspective on medical device efficacy, and as a government institution, it is a trusted independent source for medical device evaluation. The VA’s role in the evaluation of 3D-printed medical devices will benefit veterans and their families, clinicians, hospitals, and the broader public by providing a gold-standard evaluation for the growing medical 3D-printing industry to follow. By creating new pathways and expectations for how federal agencies maintain crisis preparedness—such as establishing a digital stockpile—we can be equipped to serve the US health care system and minimize the effects of supply chain disruptions.

1. Sacks CA, Kesselheim AS, Fralick M. The shortage of normal saline in the wake of Hurricane Maria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):885–886. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1936

2. Bauchner H, Fontanarosa PB, Livingston EH. Conserving supply of personal protective equipment–a call for ideas. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1911. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4770

3. Sinha MS, Bourgeois FT, Sorger PK. Personal protective equipment for COVID-19: distributed fabrication and additive manufacturing. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(8):1162-1164. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2020.305753

4. McCarthy MC, Di Prima M, Cruz P, et al. Trust in the time of Covid-19: 3D printing and additive manufacturing (3DP/AM) as a solution to supply chain gaps. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(6). doi:10.1056/CAT.21.0321

5. Ford J, Goldstein T, Trahan S, Neuwirth A, Tatoris K, Decker S. A 3D-printed nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19 diagnostic testing. 3D Print Med. 2020;6(1):21. Published 2020 Aug 15. doi:10.1186/s41205-020-00076-3

6. Callahan CJ, Lee R, Zulauf K, et al. Open development and clinical validation of multiple 3D-printed sample-collection swabs: rapid resolution of a critical COVID-19 testing bottleneck. Preprint. medRxiv. 2020;2020.04.14.20065094. Published 2020 Apr 17. doi:10.1101/2020.04.14.20065094

7. Decker SJ, Goldstein TA, Ford JM, et al. 3-dimensional printed alternative to the standard synthetic flocked nasopharyngeal swabs used for coronavirus disease 2019 testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(9):e3027-e3032. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1366

8. US Food and Drug Administration. Memorandum of understanding: rapid response to Covid-19 using 3d printing between National Institutes of Health within U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Food and Drug Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Veterans Health Administration within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. March 26, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/domestic-mous/mou-225-20-008

9. National Institutes of Health, NIH 3D Print Exchange. Covid 3D trust: trusted repository for users and suppliers through testing. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://3d.nih.gov/collections/covid-19-response?tab=search

10. National Institutes of Health, NIH 3D Print Exchange. 3D printed nasal swabs - assessment criteria. August 17, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://3d.nih.gov/collections/covid-19-response?tab=swabassessment

11. National Institutes of Health, NIH 3D Print Exchange. 3D printed nasal swabs - general information. August 17, 2020. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://3d.nih.gov/collections/covid-19-response?tab=swabinfo

12. US Department of Defense. Coronavirus: DOD response. December 20, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.defense.gov/Spotlights/Coronavirus-DoD-Response

13. US Department of Health and Human Services, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority. BARDA COVID-19 response. Updated May 25, 2023. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.medicalcountermeasures.gov/barda/barda-covid-19-response

14. Green S. Pandemic prevention platform (P3). Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.darpa.mil/program/pandemic-prevention-platform

15. America Makes. America makes completes successful scenario testing for crisis response program [press release]. May 25, 2021. Accessed August 31, 2023. https://www.americamakes.us/america-makes-completes-successful-scenario-testing-for-crisis-response-program

Traditional manufacturing concentrates capacity into a few discrete locations while applying lean and just-in-time philosophies to maximize profit during times of somewhat predictable supply and demand. This approach exposed nationwide vulnerabilities even during local crises, such as the United States saline shortages following closure of a single plant in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria in 2017.1 Interruptions to the supply chain due to pandemic plant closure, weather, politics, or surge demand can cause immediate and lasting shortages. Nasal swabs were a clear example.

At the onset of COVID-19, 2 companies—Puritan in Guilford, Maine, and Copan in Italy—manufactured nearly all of the highly specialized nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs singled out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to test patients for COVID-19. Demand for swabs skyrocketed as the virus spread, and they became unattainable. The lack of swabs meant patients went undiagnosed. Without knowing who was positive, people with symptoms and known contacts were presumed positive and quarantined, impacting isolated patients, the health care professionals treating them, and the entire US economy.

3-Dimensional Printing Solutions

Manufacturing NP swabs is not trivial. Their simple shape conceals complexity and requires highly specialized equipment. The lead time for one non-US machine manufacturer was > 6 months at the start of the pandemic.

Digital manufacturing/3-dimensional (3D) printing represented a potential solution to the supply chain crisis.2 Designers created digital blueprints for 3D-printed goods, face masks, face shields, and ventilator splitters were rapidly created and shared.3,4 Scrambling to fill the critical need for NP swabs, many hospitals, businesses, and academic centers began 3D printing swabs. This effort was spearheaded by University of South Florida (USF) and Northwell Health researchers and clinicians, who designed and tested a 3D-printed NP swab from photocurable resin that was printable on 2 models of Formlabs printers.5 Several other 3D-printed NP swab designs soon followed. This innovation and problem-solving renaissance faced several challenges well known to traditional manufacturers of regulated products but novel to newcomers.

The first challlenge was that these NP swabs predate FDA oversight of medical device development and manufacturing and no testing standards existed. Designers began casting prototypes out without guidance about the critical features and clinical functions required. Many of these designs did not have a clinical evaluation pathway to test safety and efficacy.

The second challlenge was that these swabs were being produced by facilities not registered with the FDA. This raised concerns about the quality of unlisted medical products developed and manufactured at novel facilities.

The third challenge was that small-scale novel approaches may offset local shortages but could not address national needs. The self-organized infrastructure for this crisis was ad hoc, local, and lacked coordinated federal support. This led to rolling shortages of these materials for years.

Two studies were performed early in the pandemic. The first study evaluated 4 prototypes of different manufacturer designs, finding excellent concordance among them and their control swab.6 A second study demonstrated the USF swab to be noninferior to the standard of care.7 Both studies acknowledged and addressed the first challenge for their designs.

COLLABORATIONS

Interagency

Before the pandemic, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had been coordinating with the FDA, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the nonprofit America Makes to bring medical product development and manufacturing closer to the point of care.

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the collaboration was formalized to address new challenges.8 The objectives of this collaboration were the following: (1) host a digital repository for 3D-printed digital designs for personal protectice equipment and other medical supplies in or at risk of shortage; (2) provide scientifically based ratings for designs according to clinical and field testing; and (3) offer education to health care workers and the public about the digital manufacturing of medical goods and devices.4,9

A key output of this collaboration was the COVID 3D Trusted Repository For Users And Suppliers Through Testing (COVID 3D TRUST), a curated archive of designs. In most cases, existing FDA standards and guidance formed the basis of testing strategies with deviations due to limited access to traditional testing facilities and reagents.

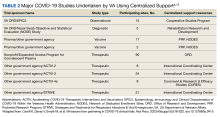

To address novel NP swabs, working with its COVID 3D TRUST partners, the VA gathered a combined list of clinical- and engineering-informed customer requirements and performed a hazard analysis. The result was a list of design inputs for NP swabs and 8 standard test protocols to evaluate key functions (Table).10 These protocols are meant to benchmark novel 3D-printed swabs against the key functions of established, traditionally manufactured swabs, which have a long record of safety and efficacy. The protocols, developed by the VA and undergoing validation by the US Army, empower and inform consumers and provide performance metrics to swab designers and manufacturers. The testing protocols and preliminary test results developed by the VA are publicly available at the NIH.11

Intra-agency

The use of the inputs and verification tests noted in the Table may reduce the risk of poor design but were inadequate to evaluate the clinical safety and efficacy of novel swabs. Recognizing this, the VA Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning (OHIL) and the Office of Research and Development (ORD) launched the Nasal Swab Objective and Statistical Evaluation (NOSE) study to formally evaluate the safety and efficacy of 3D-printed swabs in the field. This multisite clinical study was a close collaboration between the OHIL and ORD. The OHIL provided the quality system and manufacturing oversight and delivery of the swabs, and the ORD provided scientific review, research infrastructure, human subjects oversight, administrative support, and funding and fiscal oversight. The OHIL/ORD collaboration resulted in the successful completion of the NOSE study.

This study (manuscript under preparation) yielded two 3D-printing production processes and swab designs that had comparable performance to the standard of care, were manufacturable compliant with FDA guidelines, and could be produced at scale in a distributed manner. This approach directly addressed the 3 challenges described earlier.

LESSONS LEARNED

Swabs were an example of supply challenges in the pandemic, but advanced manufacturing (notably, digital designs leading to 3D-printed solutions) also served as a temporary solution to device and product shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital designs and 3D printing as manufacturing techniques have the following key advantages: (1) they are distributed in nature, both in the breadth of locations that have access to these manufacturing platforms and in the depth of material choice that can be used to fabricate products, which alleviates the threat of a disaster impacting manufacturing capacity or a material stream; (2) they do not require retooling of machinery so new products can deploy rapidly and on demand; and (3) the speed of digital iteration, printing, and revision allows for rapid product development and production.

There also are notable disadvantages to these techniques. First, because 3D printing is a newer technology, there is less general depth of knowledge regarding design and material choice for additive manufacturing. Second, the flexibility of 3D printing means that operators must increase awareness of the factors that might cause the fabrication of a part to fail in either printing or postprocessing. Third, there are significant gaps in understanding how materials and manufacturing processes will perform in high-stakes settings such as health care, where performance and biocompatibility may be critical to support life-sustaining functions. Fourth, digital files are vulnerable to intentional or unintentional alteration. These alterations might weaken design integrity and be imperceptible to the manufacturer or end user. This is a prevalent challenge in all open-source designs.

The pandemic materialized quickly and created vast supply chain challenges. To address this crisis, it was clear that the average 17-year interval between research and translation in the US was unacceptable. The VA was able to accelerate swiftly many existing processes to meet this need, build new capabilities, and establish new practices for the rapid evaluation and deployment of health care products and guidance. This agile and innovative cooperation was critical in the success of the VA’s national support for pandemic solutions.

Finally, although COVID 3D TRUST was able to provide testing of submitted designs, this collaboration was not a substitute for the “peacetime” process of manufacturing site registration with the FDA and product listing. COVID 3D TRUST could evaluate designs only, not the production process, safety, and efficacy.

CALLS TO ACTION

The pandemic's impact on medical supply chain security persists, as does the need for greater foresight and crisis preparation. We must act now to avoid experiencing again the magnitude of fatalities (civilian and veteran) and the devastation to the US economy and livelihoods that occurred during this single biological event. To this end, creating a digital stockpile of federally curated, crisis-ready designs for as-needed distribution across our US industrial base would offer a second line of defense against life-threatening supply chain interruptions. The realization of such a digital stockpile requires calls to action among multiple contributors.

Collaborations

The VA’s Fourth Mission is to improve the nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters. The VA does this by developing plans and taking actions to ensure continued service to veterans, as well as to support national, state, and local emergency management, public health, safety, and homeland security efforts.

The VA partnership with the FDA and NIH during the pandemic enabled successful coordination among federal agencies. Numerous other agencies, including the US Department of Defense (DoD), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), also developed and executed successful initiatives.12-14 The joint awareness and management of these efforts, however, could be strengthened through more formal agreements and processes in peacetime. The VA/FDA/NIH Memorandum of Understanding is a prototype example of each agency lending its subject matter expertise to address a host of pandemic challenges collectively, cooperatively, and efficiently.8

Public-private partnerships (eg, VA/FDA/NIH and America Makes) led to coordinated responses for crisis readiness. The Advanced Manufacturing Crisis Product Response Program, a multipartner collaboration that included VA, addressed 7 crisis scenarios, 3 of which were specifically related to COVID-19.15 In addition, both BARDA and DARPA had successful public-private collaborations, and the DoD supported national logistics and other efforts.12-14 Clearly, industry and government both recognize complementary synergies: (1) the depth of resources of US industry; and (2) the national resources, coordination, and clinical insight available through federal agencies that can address the challenges of future crises quickly and efficiently.

When traditional supply chains and manufacturing processes failed during the pandemic, new techniques were exploited to fill the unmet material needs. Novel techniques and product pathways, however, are untested or undeveloped. The collaboration between the ORD and OHIL in support of NP swab testing and production is an example of bringing research insight, regulated product development, and manufacturing together to support a complete product life cycle.

Joint Awareness and Management

The VA continues to refine the joint awareness and management (JAM) process of products from ideation to translation, to shorten the time from research to product delivery. JAM is a VA collaborative committee of partners from ORD research offices and technology transfer program, and the OHIL Office of Advanced Manufacturing, which seeks additional support and guidance from VHA clinical service lines, VA Office of General Council, and VA Office of Acquisitions, Logistics, and Construction.

This team enables the rapid identification of unmet veteran health care product needs. In addition, JAM leverages the resources of each group to support products from problem identification to solution ideation, regulated development, production, and delivery into clinical service lines. While the concept of JAM arose to meet the crisis needs of the pandemic, it persists in delivering advanced health care solutions to veterans.

A Proposed Plan

The next national crisis is likely to involve and threaten national health care security. We propose that federal agencies be brought together to form a federally supported digital stockpile. This digital stockpile must encompass, at minimum, the following features: (1) preservation of novel, scalable medical supplies and products generated during the COVID-19 pandemic, to avoid the loss of this work; (2) clinical maturation of those existing supplies and products to refine their features and functions under the guidance of clinical, regulatory, and manufacturing experts—and validate those outputs with clinical evidence; (3) manufacturing maturation of those existing supplies and products, such that complete design and production processes are developed with the intent to distribute to multiple public manufacturers during the next crisis; (4) a call for new designs/intake portal for new designs to be matured and curated as vulnerabilities are identified; (5) supply chain crisis drills executed to test public-private preparedness to ensure design transfer is turnkey and can be engaged quickly during the next crisis; and (6) public-private engagement to develop strategy, scenarios, and policy to ensure that when supply chains next fail, additional surge capacity can be quickly added to protect American lives and health care, and that when supply chains resume, surge capacity can be redirected or stood down to protect the competitive markets.

This digital stockpile can complement and be part of the Strategic National Stockpile. Whereas the Strategic National Stockpile is a reserve of physical products that may offset product shortages, the digital stockpile is a reserve of turnkey, transferable designs that may offset supply chain disruptions and production-capacity shortages.

CONCLUSIONS

The success of 3D-printed NP swabs is a specific example of the importance of collaborations across industry, government, innovators, and researchers. More important than a sole product, however, these collaborations demonstrated the potential for game-changing approaches to how public-private partnerships support the continuity of health care operations nationally and prevent the potential for unnecessary loss of life due to capacity and supply chain disruptions.

As the largest health care system in the US, the VA has a unique capability to lead in the assessment of other novel 3D-printed medical devices in partnership with the FDA. The VA has a unique patient-centered perspective on medical device efficacy, and as a government institution, it is a trusted independent source for medical device evaluation. The VA’s role in the evaluation of 3D-printed medical devices will benefit veterans and their families, clinicians, hospitals, and the broader public by providing a gold-standard evaluation for the growing medical 3D-printing industry to follow. By creating new pathways and expectations for how federal agencies maintain crisis preparedness—such as establishing a digital stockpile—we can be equipped to serve the US health care system and minimize the effects of supply chain disruptions.

Traditional manufacturing concentrates capacity into a few discrete locations while applying lean and just-in-time philosophies to maximize profit during times of somewhat predictable supply and demand. This approach exposed nationwide vulnerabilities even during local crises, such as the United States saline shortages following closure of a single plant in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria in 2017.1 Interruptions to the supply chain due to pandemic plant closure, weather, politics, or surge demand can cause immediate and lasting shortages. Nasal swabs were a clear example.

At the onset of COVID-19, 2 companies—Puritan in Guilford, Maine, and Copan in Italy—manufactured nearly all of the highly specialized nasopharyngeal (NP) swabs singled out by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to test patients for COVID-19. Demand for swabs skyrocketed as the virus spread, and they became unattainable. The lack of swabs meant patients went undiagnosed. Without knowing who was positive, people with symptoms and known contacts were presumed positive and quarantined, impacting isolated patients, the health care professionals treating them, and the entire US economy.

3-Dimensional Printing Solutions

Manufacturing NP swabs is not trivial. Their simple shape conceals complexity and requires highly specialized equipment. The lead time for one non-US machine manufacturer was > 6 months at the start of the pandemic.

Digital manufacturing/3-dimensional (3D) printing represented a potential solution to the supply chain crisis.2 Designers created digital blueprints for 3D-printed goods, face masks, face shields, and ventilator splitters were rapidly created and shared.3,4 Scrambling to fill the critical need for NP swabs, many hospitals, businesses, and academic centers began 3D printing swabs. This effort was spearheaded by University of South Florida (USF) and Northwell Health researchers and clinicians, who designed and tested a 3D-printed NP swab from photocurable resin that was printable on 2 models of Formlabs printers.5 Several other 3D-printed NP swab designs soon followed. This innovation and problem-solving renaissance faced several challenges well known to traditional manufacturers of regulated products but novel to newcomers.

The first challlenge was that these NP swabs predate FDA oversight of medical device development and manufacturing and no testing standards existed. Designers began casting prototypes out without guidance about the critical features and clinical functions required. Many of these designs did not have a clinical evaluation pathway to test safety and efficacy.

The second challlenge was that these swabs were being produced by facilities not registered with the FDA. This raised concerns about the quality of unlisted medical products developed and manufactured at novel facilities.

The third challenge was that small-scale novel approaches may offset local shortages but could not address national needs. The self-organized infrastructure for this crisis was ad hoc, local, and lacked coordinated federal support. This led to rolling shortages of these materials for years.

Two studies were performed early in the pandemic. The first study evaluated 4 prototypes of different manufacturer designs, finding excellent concordance among them and their control swab.6 A second study demonstrated the USF swab to be noninferior to the standard of care.7 Both studies acknowledged and addressed the first challenge for their designs.

COLLABORATIONS

Interagency

Before the pandemic, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) had been coordinating with the FDA, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the nonprofit America Makes to bring medical product development and manufacturing closer to the point of care.

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the collaboration was formalized to address new challenges.8 The objectives of this collaboration were the following: (1) host a digital repository for 3D-printed digital designs for personal protectice equipment and other medical supplies in or at risk of shortage; (2) provide scientifically based ratings for designs according to clinical and field testing; and (3) offer education to health care workers and the public about the digital manufacturing of medical goods and devices.4,9

A key output of this collaboration was the COVID 3D Trusted Repository For Users And Suppliers Through Testing (COVID 3D TRUST), a curated archive of designs. In most cases, existing FDA standards and guidance formed the basis of testing strategies with deviations due to limited access to traditional testing facilities and reagents.

To address novel NP swabs, working with its COVID 3D TRUST partners, the VA gathered a combined list of clinical- and engineering-informed customer requirements and performed a hazard analysis. The result was a list of design inputs for NP swabs and 8 standard test protocols to evaluate key functions (Table).10 These protocols are meant to benchmark novel 3D-printed swabs against the key functions of established, traditionally manufactured swabs, which have a long record of safety and efficacy. The protocols, developed by the VA and undergoing validation by the US Army, empower and inform consumers and provide performance metrics to swab designers and manufacturers. The testing protocols and preliminary test results developed by the VA are publicly available at the NIH.11

Intra-agency

The use of the inputs and verification tests noted in the Table may reduce the risk of poor design but were inadequate to evaluate the clinical safety and efficacy of novel swabs. Recognizing this, the VA Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning (OHIL) and the Office of Research and Development (ORD) launched the Nasal Swab Objective and Statistical Evaluation (NOSE) study to formally evaluate the safety and efficacy of 3D-printed swabs in the field. This multisite clinical study was a close collaboration between the OHIL and ORD. The OHIL provided the quality system and manufacturing oversight and delivery of the swabs, and the ORD provided scientific review, research infrastructure, human subjects oversight, administrative support, and funding and fiscal oversight. The OHIL/ORD collaboration resulted in the successful completion of the NOSE study.

This study (manuscript under preparation) yielded two 3D-printing production processes and swab designs that had comparable performance to the standard of care, were manufacturable compliant with FDA guidelines, and could be produced at scale in a distributed manner. This approach directly addressed the 3 challenges described earlier.

LESSONS LEARNED

Swabs were an example of supply challenges in the pandemic, but advanced manufacturing (notably, digital designs leading to 3D-printed solutions) also served as a temporary solution to device and product shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digital designs and 3D printing as manufacturing techniques have the following key advantages: (1) they are distributed in nature, both in the breadth of locations that have access to these manufacturing platforms and in the depth of material choice that can be used to fabricate products, which alleviates the threat of a disaster impacting manufacturing capacity or a material stream; (2) they do not require retooling of machinery so new products can deploy rapidly and on demand; and (3) the speed of digital iteration, printing, and revision allows for rapid product development and production.

There also are notable disadvantages to these techniques. First, because 3D printing is a newer technology, there is less general depth of knowledge regarding design and material choice for additive manufacturing. Second, the flexibility of 3D printing means that operators must increase awareness of the factors that might cause the fabrication of a part to fail in either printing or postprocessing. Third, there are significant gaps in understanding how materials and manufacturing processes will perform in high-stakes settings such as health care, where performance and biocompatibility may be critical to support life-sustaining functions. Fourth, digital files are vulnerable to intentional or unintentional alteration. These alterations might weaken design integrity and be imperceptible to the manufacturer or end user. This is a prevalent challenge in all open-source designs.

The pandemic materialized quickly and created vast supply chain challenges. To address this crisis, it was clear that the average 17-year interval between research and translation in the US was unacceptable. The VA was able to accelerate swiftly many existing processes to meet this need, build new capabilities, and establish new practices for the rapid evaluation and deployment of health care products and guidance. This agile and innovative cooperation was critical in the success of the VA’s national support for pandemic solutions.

Finally, although COVID 3D TRUST was able to provide testing of submitted designs, this collaboration was not a substitute for the “peacetime” process of manufacturing site registration with the FDA and product listing. COVID 3D TRUST could evaluate designs only, not the production process, safety, and efficacy.

CALLS TO ACTION

The pandemic's impact on medical supply chain security persists, as does the need for greater foresight and crisis preparation. We must act now to avoid experiencing again the magnitude of fatalities (civilian and veteran) and the devastation to the US economy and livelihoods that occurred during this single biological event. To this end, creating a digital stockpile of federally curated, crisis-ready designs for as-needed distribution across our US industrial base would offer a second line of defense against life-threatening supply chain interruptions. The realization of such a digital stockpile requires calls to action among multiple contributors.

Collaborations

The VA’s Fourth Mission is to improve the nation’s preparedness for response to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disasters. The VA does this by developing plans and taking actions to ensure continued service to veterans, as well as to support national, state, and local emergency management, public health, safety, and homeland security efforts.

The VA partnership with the FDA and NIH during the pandemic enabled successful coordination among federal agencies. Numerous other agencies, including the US Department of Defense (DoD), the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), also developed and executed successful initiatives.12-14 The joint awareness and management of these efforts, however, could be strengthened through more formal agreements and processes in peacetime. The VA/FDA/NIH Memorandum of Understanding is a prototype example of each agency lending its subject matter expertise to address a host of pandemic challenges collectively, cooperatively, and efficiently.8

Public-private partnerships (eg, VA/FDA/NIH and America Makes) led to coordinated responses for crisis readiness. The Advanced Manufacturing Crisis Product Response Program, a multipartner collaboration that included VA, addressed 7 crisis scenarios, 3 of which were specifically related to COVID-19.15 In addition, both BARDA and DARPA had successful public-private collaborations, and the DoD supported national logistics and other efforts.12-14 Clearly, industry and government both recognize complementary synergies: (1) the depth of resources of US industry; and (2) the national resources, coordination, and clinical insight available through federal agencies that can address the challenges of future crises quickly and efficiently.

When traditional supply chains and manufacturing processes failed during the pandemic, new techniques were exploited to fill the unmet material needs. Novel techniques and product pathways, however, are untested or undeveloped. The collaboration between the ORD and OHIL in support of NP swab testing and production is an example of bringing research insight, regulated product development, and manufacturing together to support a complete product life cycle.

Joint Awareness and Management

The VA continues to refine the joint awareness and management (JAM) process of products from ideation to translation, to shorten the time from research to product delivery. JAM is a VA collaborative committee of partners from ORD research offices and technology transfer program, and the OHIL Office of Advanced Manufacturing, which seeks additional support and guidance from VHA clinical service lines, VA Office of General Council, and VA Office of Acquisitions, Logistics, and Construction.

This team enables the rapid identification of unmet veteran health care product needs. In addition, JAM leverages the resources of each group to support products from problem identification to solution ideation, regulated development, production, and delivery into clinical service lines. While the concept of JAM arose to meet the crisis needs of the pandemic, it persists in delivering advanced health care solutions to veterans.

A Proposed Plan