User login

Potential Impact of USPS Mail Delivery Delays on Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 In 2022, there were an estimated 151,030 new CRC cases and 52,580 deaths.1 Options for CRC screening of patients at average risk include stool tests (annual fecal immunochemical test [FIT], annual guaiac-based fecal occult blood test, or stool FIT-DNA test every 1 to 3 years), colonoscopies every 10 years, flexible sigmoidoscopies every 5 years (or every 10 years with annual FIT), and computed tomography (CT) colonography every 5 years.2 Many health care systems use annual FIT for patients at average risk. Compared with guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing, FIT does not require dietary or medication modifications and yields greater sensitivity and patient participation.3

The COVID-19 pandemic and staffing issues have caused a scheduling backlog for screening, diagnostic, and surveillance endoscopies at some medical centers. As a result, FIT has become the primary means of CRC screening at these institutions. FIT kits for home use are typically distributed to eligible patients at an office visit or by mail, and patients are then instructed to mail the kits back to the laboratory. For the test to be as sensitive as possible, FIT kit manufacturers advise laboratory analysis within 14 to 15 days of collection, if stored at ambient temperature, and to reject the sample if it does not meet testing criteria for stability. Delayed FIT sample analysis has been associated with higher false-negative rates because of hemoglobin degradation.4 FIT sample exposure to high ambient temperatures also has been linked to decreased sensitivity for detecting CRC.5

US Postal Service (USPS) mail delivery delays have plagued many areas of the country. A variety of factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, understaffing, changes in USPS policies, closure of post offices, and changes in mail delivery standards, may also be contributory causes. According to the USPS website, delivery standard for first-class mail is 1 to 5 days, but this is not guaranteed.6

The Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) laboratory in Chicago has reported receiving FIT kit envelopes in batches by the USPS, with some prepaid first-class business reply envelopes delivered up to 60 days after the time of sample collection. Polymedco, a company that assists US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers with logistics of FIT programs for CRC screening, reports that USPS batching of FIT kits leading to delayed delivery has been a periodic problem for medical centers around the country. Polymedco staff remind USPS staff about 4 points when they encounter this issue: Mailers are first-class mail; mailers contain a human biologic specimen that has limited viability; the biological sample used for detecting cancer is time sensitive; and delays in delivery by holding/batching kits could impact morbidity and mortality. Reviewing these key points with local USPS staff usually helps, however, batching and delayed delivery of the FIT kits can sometimes recur with USPS staffing turnover.

Tracking and identifying when a patient receives the FIT kit is difficult. Patients are instructed to write the date of collection on the kit, so the receiving laboratory knows whether the sample can be reliably analyzed. When patients are notified about delayed delivery of their sample, a staff member asks if they postponed dropping the kit in the mail. Most patients report mailing the sample within 1 to 2 days of collection. Tracking and dating each step of FIT kit events is not feasible with a mass mailing campaign. In our experience, most patients write the date of collection on the kit. If a collection date is not provided, the laboratory will call the patient to confirm a date. Cheng and colleagues reviewed the causes for FIT specimen rejection in a laboratory analyzing specimens for VA patients and found that 14% of submitted samples were rejected because the specimen was received > 14 days after collection, and 6% because the patient did not record the collection date. With a series of interventions aimed at reminding patients and improving laboratory procedures, rates of rejection for these 2 causes were reduced to < 4%.7 USPS delays were not identified as a factor or tracked in this study.

It is unclear why the USPS sometimes holds FIT kits at their facilities and then delivers large bins of them at the same time. Because FIT kits should be analyzed within 14 to 15 days of sample collection to assure reliable results, mail delivery delays can result in increased sample rejection. Based on the JBVAMC experience, up to 30% of submitted samples might need to be discarded when batched delivery takes place. In these cases, patients need to be contacted, informed of the problem, and asked to submit new kits. Understandably, patients are reluctant to repeat this type of testing, and we are concerned this could lead to reduced rates of CRC screening in affected communities.

As an alternative to discarding delayed samples, laboratories could report the results of delayed FIT kits with an added comment that “negative test results may be less reliable due to delayed processing,” but this approach would raise quality and medicolegal concerns. Clinicians have reached out to local USPS supervisory personnel with mixed results. Sometimes batching and delayed deliveries stop for a few months, only to resume without warning. Dropping off the sample directly at the laboratory is not a realistic option for most patients. Some patients can be convinced to submit another sample, some elect to switch to other CRC screening strategies, while others, unfortunately, decline further screening efforts.

Laboratory staff can be overwhelmed with having to process hundreds of samples in a short time frame, especially because there is no way of knowing when USPS will make a batched delivery. Laboratory capacities can limit staff at some facilities to performing analysis of only 10 tests at a time. The FIT kits should be delivered on a rolling basis and without delay so that the samples can be reliably analyzed with a predictable workload for the laboratory personnel and without unexpected surges.

When health care facilities identify delayed mail delivery of FIT kits via USPS, laboratories should first ensure that the correct postage rates are used on the prepaid envelopes and that their USPS accounts are properly funded, so that insufficient funds are not contributing to delayed deliveries. Stakeholders should then reach out to local USPS supervisory staff and request that the practice of batching the delivery of FIT kits be stopped. Educating USPS supervisory staff about concerns related to decreased test reliability associated with delayed mail delivery can be a persuasive argument. Adding additional language to the preprinted envelopes, such as “time sensitive,” may also be helpful. Unfortunately, the JBVAMC experience has been that the problem initially gets better after contacting the USPS, only to unexpectedly resurface months later. This cycle has been repeated several times in the past 2 years at JBVAMC.

All clinicians involved in CRC screening and treatment at institutions that use FIT kits need to be aware of the impact that local USPS delays can have on the reliability of these results. Health care systems should be prepared to implement mitigation strategies if they encounter significant delays with mail delivery. If delays cannot be reliably resolved by working with the local USPS staff, consider involving national USPS oversight bodies. And if the problems persist despite an attempt to work with the USPS, some institutions might find it feasible to offer drop boxes at their clinics and instruct patients to drop off FIT kits immediately following collection, in lieu of mailing them. Switching to private carriers is not a cost-effective alternative for most health care systems, and some may exclude rural areas. Depending on the local availability and capacity of endoscopists, some clinicians might prioritize referring patients for screening colonoscopies or screening flexible sigmoidoscopies, and might deemphasize FIT kits as a preferred option for CRC screening. CT colonography is an alternative screening method that is not as widely offered, nor as widely accepted at this time.

Conclusions

CRC screening is an essential part of preventive medicine, and the percentage of eligible patients screened is a well-established quality metric in primary care settings. Health care systems, clinicians, and laboratories must be vigilant to ensure that USPS delays in delivering FIT kits do not negatively impact their CRC screening programs. Facilities should actively monitor for delays in the return of FIT kits.

Despite the widespread use of mail-order pharmacies and the use of mail to communicate notifications about test results and follow-up appointments, unreliable or delayed mail delivery traditionally has not been considered a social determinant of health.8 This article highlights the impact delayed mail delivery can have on health outcomes. Disadvantaged communities in inner cities and rural areas have been disproportionately affected by the worsening performance of the USPS over the past few years.9 This represents an underappreciated public health concern in need of a sustainable solution.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer screening tests. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/tests.htm

3. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):82-90. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040

4. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, van Oijen MG, et al. False negative fecal occult blood tests due to delayed sample return in colorectal cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(4):746-750. doi:10.1002/ijc.24458

5. Doubeni CA, Jensen CD, Fedewa SA, et al. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colon cancer screening: variable performance with ambient temperature. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):672-681. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.160060

6. United States Postal Service. Shipping and mailing with USPS. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.usps.com/ship

7. Cheng C, Ganz DA, Chang ET, Huynh A, De Peralta S. Reducing rejected fecal immunochemical tests received in the laboratory for colorectal cancer screening. J Healthc Qual. 2019;41(2):75-82.doi:10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000181

8. Hussaini SMQ, Alexander GC. The United States Postal Service: an essential public health agency? J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3699-3701. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06275-2

9. Hampton DJ. Colorado mountain towns are plagued by post office delays as residents wait weeks for medication and retirement checks. NBC News. February 25, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/colo-mountain-towns-are-plagued-post-office-delays-residents-wait-week-rcna72085

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 In 2022, there were an estimated 151,030 new CRC cases and 52,580 deaths.1 Options for CRC screening of patients at average risk include stool tests (annual fecal immunochemical test [FIT], annual guaiac-based fecal occult blood test, or stool FIT-DNA test every 1 to 3 years), colonoscopies every 10 years, flexible sigmoidoscopies every 5 years (or every 10 years with annual FIT), and computed tomography (CT) colonography every 5 years.2 Many health care systems use annual FIT for patients at average risk. Compared with guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing, FIT does not require dietary or medication modifications and yields greater sensitivity and patient participation.3

The COVID-19 pandemic and staffing issues have caused a scheduling backlog for screening, diagnostic, and surveillance endoscopies at some medical centers. As a result, FIT has become the primary means of CRC screening at these institutions. FIT kits for home use are typically distributed to eligible patients at an office visit or by mail, and patients are then instructed to mail the kits back to the laboratory. For the test to be as sensitive as possible, FIT kit manufacturers advise laboratory analysis within 14 to 15 days of collection, if stored at ambient temperature, and to reject the sample if it does not meet testing criteria for stability. Delayed FIT sample analysis has been associated with higher false-negative rates because of hemoglobin degradation.4 FIT sample exposure to high ambient temperatures also has been linked to decreased sensitivity for detecting CRC.5

US Postal Service (USPS) mail delivery delays have plagued many areas of the country. A variety of factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, understaffing, changes in USPS policies, closure of post offices, and changes in mail delivery standards, may also be contributory causes. According to the USPS website, delivery standard for first-class mail is 1 to 5 days, but this is not guaranteed.6

The Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) laboratory in Chicago has reported receiving FIT kit envelopes in batches by the USPS, with some prepaid first-class business reply envelopes delivered up to 60 days after the time of sample collection. Polymedco, a company that assists US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers with logistics of FIT programs for CRC screening, reports that USPS batching of FIT kits leading to delayed delivery has been a periodic problem for medical centers around the country. Polymedco staff remind USPS staff about 4 points when they encounter this issue: Mailers are first-class mail; mailers contain a human biologic specimen that has limited viability; the biological sample used for detecting cancer is time sensitive; and delays in delivery by holding/batching kits could impact morbidity and mortality. Reviewing these key points with local USPS staff usually helps, however, batching and delayed delivery of the FIT kits can sometimes recur with USPS staffing turnover.

Tracking and identifying when a patient receives the FIT kit is difficult. Patients are instructed to write the date of collection on the kit, so the receiving laboratory knows whether the sample can be reliably analyzed. When patients are notified about delayed delivery of their sample, a staff member asks if they postponed dropping the kit in the mail. Most patients report mailing the sample within 1 to 2 days of collection. Tracking and dating each step of FIT kit events is not feasible with a mass mailing campaign. In our experience, most patients write the date of collection on the kit. If a collection date is not provided, the laboratory will call the patient to confirm a date. Cheng and colleagues reviewed the causes for FIT specimen rejection in a laboratory analyzing specimens for VA patients and found that 14% of submitted samples were rejected because the specimen was received > 14 days after collection, and 6% because the patient did not record the collection date. With a series of interventions aimed at reminding patients and improving laboratory procedures, rates of rejection for these 2 causes were reduced to < 4%.7 USPS delays were not identified as a factor or tracked in this study.

It is unclear why the USPS sometimes holds FIT kits at their facilities and then delivers large bins of them at the same time. Because FIT kits should be analyzed within 14 to 15 days of sample collection to assure reliable results, mail delivery delays can result in increased sample rejection. Based on the JBVAMC experience, up to 30% of submitted samples might need to be discarded when batched delivery takes place. In these cases, patients need to be contacted, informed of the problem, and asked to submit new kits. Understandably, patients are reluctant to repeat this type of testing, and we are concerned this could lead to reduced rates of CRC screening in affected communities.

As an alternative to discarding delayed samples, laboratories could report the results of delayed FIT kits with an added comment that “negative test results may be less reliable due to delayed processing,” but this approach would raise quality and medicolegal concerns. Clinicians have reached out to local USPS supervisory personnel with mixed results. Sometimes batching and delayed deliveries stop for a few months, only to resume without warning. Dropping off the sample directly at the laboratory is not a realistic option for most patients. Some patients can be convinced to submit another sample, some elect to switch to other CRC screening strategies, while others, unfortunately, decline further screening efforts.

Laboratory staff can be overwhelmed with having to process hundreds of samples in a short time frame, especially because there is no way of knowing when USPS will make a batched delivery. Laboratory capacities can limit staff at some facilities to performing analysis of only 10 tests at a time. The FIT kits should be delivered on a rolling basis and without delay so that the samples can be reliably analyzed with a predictable workload for the laboratory personnel and without unexpected surges.

When health care facilities identify delayed mail delivery of FIT kits via USPS, laboratories should first ensure that the correct postage rates are used on the prepaid envelopes and that their USPS accounts are properly funded, so that insufficient funds are not contributing to delayed deliveries. Stakeholders should then reach out to local USPS supervisory staff and request that the practice of batching the delivery of FIT kits be stopped. Educating USPS supervisory staff about concerns related to decreased test reliability associated with delayed mail delivery can be a persuasive argument. Adding additional language to the preprinted envelopes, such as “time sensitive,” may also be helpful. Unfortunately, the JBVAMC experience has been that the problem initially gets better after contacting the USPS, only to unexpectedly resurface months later. This cycle has been repeated several times in the past 2 years at JBVAMC.

All clinicians involved in CRC screening and treatment at institutions that use FIT kits need to be aware of the impact that local USPS delays can have on the reliability of these results. Health care systems should be prepared to implement mitigation strategies if they encounter significant delays with mail delivery. If delays cannot be reliably resolved by working with the local USPS staff, consider involving national USPS oversight bodies. And if the problems persist despite an attempt to work with the USPS, some institutions might find it feasible to offer drop boxes at their clinics and instruct patients to drop off FIT kits immediately following collection, in lieu of mailing them. Switching to private carriers is not a cost-effective alternative for most health care systems, and some may exclude rural areas. Depending on the local availability and capacity of endoscopists, some clinicians might prioritize referring patients for screening colonoscopies or screening flexible sigmoidoscopies, and might deemphasize FIT kits as a preferred option for CRC screening. CT colonography is an alternative screening method that is not as widely offered, nor as widely accepted at this time.

Conclusions

CRC screening is an essential part of preventive medicine, and the percentage of eligible patients screened is a well-established quality metric in primary care settings. Health care systems, clinicians, and laboratories must be vigilant to ensure that USPS delays in delivering FIT kits do not negatively impact their CRC screening programs. Facilities should actively monitor for delays in the return of FIT kits.

Despite the widespread use of mail-order pharmacies and the use of mail to communicate notifications about test results and follow-up appointments, unreliable or delayed mail delivery traditionally has not been considered a social determinant of health.8 This article highlights the impact delayed mail delivery can have on health outcomes. Disadvantaged communities in inner cities and rural areas have been disproportionately affected by the worsening performance of the USPS over the past few years.9 This represents an underappreciated public health concern in need of a sustainable solution.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.1 In 2022, there were an estimated 151,030 new CRC cases and 52,580 deaths.1 Options for CRC screening of patients at average risk include stool tests (annual fecal immunochemical test [FIT], annual guaiac-based fecal occult blood test, or stool FIT-DNA test every 1 to 3 years), colonoscopies every 10 years, flexible sigmoidoscopies every 5 years (or every 10 years with annual FIT), and computed tomography (CT) colonography every 5 years.2 Many health care systems use annual FIT for patients at average risk. Compared with guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing, FIT does not require dietary or medication modifications and yields greater sensitivity and patient participation.3

The COVID-19 pandemic and staffing issues have caused a scheduling backlog for screening, diagnostic, and surveillance endoscopies at some medical centers. As a result, FIT has become the primary means of CRC screening at these institutions. FIT kits for home use are typically distributed to eligible patients at an office visit or by mail, and patients are then instructed to mail the kits back to the laboratory. For the test to be as sensitive as possible, FIT kit manufacturers advise laboratory analysis within 14 to 15 days of collection, if stored at ambient temperature, and to reject the sample if it does not meet testing criteria for stability. Delayed FIT sample analysis has been associated with higher false-negative rates because of hemoglobin degradation.4 FIT sample exposure to high ambient temperatures also has been linked to decreased sensitivity for detecting CRC.5

US Postal Service (USPS) mail delivery delays have plagued many areas of the country. A variety of factors, including the COVID-19 pandemic, understaffing, changes in USPS policies, closure of post offices, and changes in mail delivery standards, may also be contributory causes. According to the USPS website, delivery standard for first-class mail is 1 to 5 days, but this is not guaranteed.6

The Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) laboratory in Chicago has reported receiving FIT kit envelopes in batches by the USPS, with some prepaid first-class business reply envelopes delivered up to 60 days after the time of sample collection. Polymedco, a company that assists US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers with logistics of FIT programs for CRC screening, reports that USPS batching of FIT kits leading to delayed delivery has been a periodic problem for medical centers around the country. Polymedco staff remind USPS staff about 4 points when they encounter this issue: Mailers are first-class mail; mailers contain a human biologic specimen that has limited viability; the biological sample used for detecting cancer is time sensitive; and delays in delivery by holding/batching kits could impact morbidity and mortality. Reviewing these key points with local USPS staff usually helps, however, batching and delayed delivery of the FIT kits can sometimes recur with USPS staffing turnover.

Tracking and identifying when a patient receives the FIT kit is difficult. Patients are instructed to write the date of collection on the kit, so the receiving laboratory knows whether the sample can be reliably analyzed. When patients are notified about delayed delivery of their sample, a staff member asks if they postponed dropping the kit in the mail. Most patients report mailing the sample within 1 to 2 days of collection. Tracking and dating each step of FIT kit events is not feasible with a mass mailing campaign. In our experience, most patients write the date of collection on the kit. If a collection date is not provided, the laboratory will call the patient to confirm a date. Cheng and colleagues reviewed the causes for FIT specimen rejection in a laboratory analyzing specimens for VA patients and found that 14% of submitted samples were rejected because the specimen was received > 14 days after collection, and 6% because the patient did not record the collection date. With a series of interventions aimed at reminding patients and improving laboratory procedures, rates of rejection for these 2 causes were reduced to < 4%.7 USPS delays were not identified as a factor or tracked in this study.

It is unclear why the USPS sometimes holds FIT kits at their facilities and then delivers large bins of them at the same time. Because FIT kits should be analyzed within 14 to 15 days of sample collection to assure reliable results, mail delivery delays can result in increased sample rejection. Based on the JBVAMC experience, up to 30% of submitted samples might need to be discarded when batched delivery takes place. In these cases, patients need to be contacted, informed of the problem, and asked to submit new kits. Understandably, patients are reluctant to repeat this type of testing, and we are concerned this could lead to reduced rates of CRC screening in affected communities.

As an alternative to discarding delayed samples, laboratories could report the results of delayed FIT kits with an added comment that “negative test results may be less reliable due to delayed processing,” but this approach would raise quality and medicolegal concerns. Clinicians have reached out to local USPS supervisory personnel with mixed results. Sometimes batching and delayed deliveries stop for a few months, only to resume without warning. Dropping off the sample directly at the laboratory is not a realistic option for most patients. Some patients can be convinced to submit another sample, some elect to switch to other CRC screening strategies, while others, unfortunately, decline further screening efforts.

Laboratory staff can be overwhelmed with having to process hundreds of samples in a short time frame, especially because there is no way of knowing when USPS will make a batched delivery. Laboratory capacities can limit staff at some facilities to performing analysis of only 10 tests at a time. The FIT kits should be delivered on a rolling basis and without delay so that the samples can be reliably analyzed with a predictable workload for the laboratory personnel and without unexpected surges.

When health care facilities identify delayed mail delivery of FIT kits via USPS, laboratories should first ensure that the correct postage rates are used on the prepaid envelopes and that their USPS accounts are properly funded, so that insufficient funds are not contributing to delayed deliveries. Stakeholders should then reach out to local USPS supervisory staff and request that the practice of batching the delivery of FIT kits be stopped. Educating USPS supervisory staff about concerns related to decreased test reliability associated with delayed mail delivery can be a persuasive argument. Adding additional language to the preprinted envelopes, such as “time sensitive,” may also be helpful. Unfortunately, the JBVAMC experience has been that the problem initially gets better after contacting the USPS, only to unexpectedly resurface months later. This cycle has been repeated several times in the past 2 years at JBVAMC.

All clinicians involved in CRC screening and treatment at institutions that use FIT kits need to be aware of the impact that local USPS delays can have on the reliability of these results. Health care systems should be prepared to implement mitigation strategies if they encounter significant delays with mail delivery. If delays cannot be reliably resolved by working with the local USPS staff, consider involving national USPS oversight bodies. And if the problems persist despite an attempt to work with the USPS, some institutions might find it feasible to offer drop boxes at their clinics and instruct patients to drop off FIT kits immediately following collection, in lieu of mailing them. Switching to private carriers is not a cost-effective alternative for most health care systems, and some may exclude rural areas. Depending on the local availability and capacity of endoscopists, some clinicians might prioritize referring patients for screening colonoscopies or screening flexible sigmoidoscopies, and might deemphasize FIT kits as a preferred option for CRC screening. CT colonography is an alternative screening method that is not as widely offered, nor as widely accepted at this time.

Conclusions

CRC screening is an essential part of preventive medicine, and the percentage of eligible patients screened is a well-established quality metric in primary care settings. Health care systems, clinicians, and laboratories must be vigilant to ensure that USPS delays in delivering FIT kits do not negatively impact their CRC screening programs. Facilities should actively monitor for delays in the return of FIT kits.

Despite the widespread use of mail-order pharmacies and the use of mail to communicate notifications about test results and follow-up appointments, unreliable or delayed mail delivery traditionally has not been considered a social determinant of health.8 This article highlights the impact delayed mail delivery can have on health outcomes. Disadvantaged communities in inner cities and rural areas have been disproportionately affected by the worsening performance of the USPS over the past few years.9 This represents an underappreciated public health concern in need of a sustainable solution.

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer screening tests. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/tests.htm

3. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):82-90. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040

4. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, van Oijen MG, et al. False negative fecal occult blood tests due to delayed sample return in colorectal cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(4):746-750. doi:10.1002/ijc.24458

5. Doubeni CA, Jensen CD, Fedewa SA, et al. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colon cancer screening: variable performance with ambient temperature. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):672-681. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.160060

6. United States Postal Service. Shipping and mailing with USPS. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.usps.com/ship

7. Cheng C, Ganz DA, Chang ET, Huynh A, De Peralta S. Reducing rejected fecal immunochemical tests received in the laboratory for colorectal cancer screening. J Healthc Qual. 2019;41(2):75-82.doi:10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000181

8. Hussaini SMQ, Alexander GC. The United States Postal Service: an essential public health agency? J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3699-3701. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06275-2

9. Hampton DJ. Colorado mountain towns are plagued by post office delays as residents wait weeks for medication and retirement checks. NBC News. February 25, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/colo-mountain-towns-are-plagued-post-office-delays-residents-wait-week-rcna72085

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72(1):7-33. doi:10.3322/caac.21708

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Colorectal cancer screening tests. Updated February 23, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/basic_info/screening/tests.htm

3. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):82-90. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040

4. van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, van Oijen MG, et al. False negative fecal occult blood tests due to delayed sample return in colorectal cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(4):746-750. doi:10.1002/ijc.24458

5. Doubeni CA, Jensen CD, Fedewa SA, et al. Fecal immunochemical test (FIT) for colon cancer screening: variable performance with ambient temperature. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(6):672-681. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.06.160060

6. United States Postal Service. Shipping and mailing with USPS. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.usps.com/ship

7. Cheng C, Ganz DA, Chang ET, Huynh A, De Peralta S. Reducing rejected fecal immunochemical tests received in the laboratory for colorectal cancer screening. J Healthc Qual. 2019;41(2):75-82.doi:10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000181

8. Hussaini SMQ, Alexander GC. The United States Postal Service: an essential public health agency? J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3699-3701. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06275-2

9. Hampton DJ. Colorado mountain towns are plagued by post office delays as residents wait weeks for medication and retirement checks. NBC News. February 25, 2023. Accessed March 14, 2024. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/colo-mountain-towns-are-plagued-post-office-delays-residents-wait-week-rcna72085

Moral Injury in Health Care: A Unified Definition and its Relationship to Burnout

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

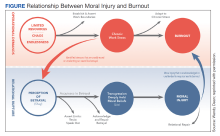

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

Moral injury was identified by health care professionals (HCPs) as a driver of occupational distress prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the crisis expanded the appeal and investigation of the term.1 HCPs now consider moral injury an essential component of the framework to describe their distress, because using the term burnout alone fails to capture their full experience and has proven resistant to interventions.2 Moral injury goes beyond the transdiagnostic symptoms of exhaustion and cynicism and beyond operational, demand-resource mismatches that characterize burnout. It describes the frustration, anger, and helplessness associated with relational ruptures and the existential threats to a clinician’s professional identity as business interests erode their ability to put their patients’ needs ahead of corporate and health care system obligations.3

Proper characterization of moral injury in health care—separate from the military environments where it originated—is stymied by an ill-defined relationship between 2 definitions of the term and by an unclear relationship between moral injury and the long-standing body of scholarship in burnout. To clarify the concept, inform research agendas, and open avenues for more effective solutions to the crisis of HCP distress, we propose a unified conceptualization of moral injury and its association with burnout in health care.

CONTEXTUAL DISTINCTIONS

It is important to properly distinguish between the original use of moral injury in the military and its expanded use in civilian circumstances. Health care and the military are both professions whereupon donning the “uniform” of a physician—or soldier, sailor, airman, or marine—members must comport with strict expectations of behavior, including the refusal to engage in illegal actions or those contrary to professional ethics. Individuals in both professions acquire a highly specialized body of knowledge and enter an implied contract to provide critical services to society, specifically healing and protection, respectively. Members of both professions are trained to make complex judgments with integrity under conditions of technical and ethical uncertainty, upon which they take highly skilled action. Medical and military professionals must be free to act on their ethical principles, without confounding demands.4 However, the context of each profession’s commitment to society carries different moral implications.

The risk of moral injury is inherent in military service. The military promises protection with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. In contrast, HCPs promise healing and care. The military promises to protect our society, with an implicit acknowledgment of the need to use lethal force to uphold the agreement. Some military actions may inflict harm without the hope of benefitting an individual, and are therefore potentially morally injurious. The health care contract with society, promising healing and care, is devoid of inherent moral injury due to harm without potential individual benefit. Therefore, the presence of moral injury in health care settings are warning signs of a dysfunctional environment.

One complex example of the dysfunctional environments is illustrative. The military and health care are among the few industries where supply creates demand. For example, the more bad state actors there are, the more demand for the military. As we have seen since the 1950s, the more technology and therapeutics we create in health care, coupled with a larger share paid for by third parties, the greater the demand for and use of them.5 In a fee for service environment, corporate greed feeds on this reality. In most other environments, more technological and therapeutic options inevitably pit clinicians against multiple other factions: payers, who do not want to underwrite them; patients, who sometimes demand them without justification or later rail against spiraling health care costs; and administrators, especially in capitated systems, who watch their bottom lines erode. The moral injury risk in this instance demands a collective conversation among stakeholders regarding the structural determinants of health—how we choose to distribute limited resources. The intermediary of moral injury is a useful measure of the harm that results from ignoring or avoiding such challenges.

HARMONIZING DEFINITIONS

Moral injury is inherently nuanced. The 2 dominant definitions arise from work with combat veterans and create additional and perhaps unnecessary complexity. Unifying these 2 definitions eliminates inadvertent confusion, preventing the risk of unbridled interdisciplinary investigation which leads to a lack of precision in the meaning of moral injury and other related concepts, such as burnout.6

The first definition was developed by Jonathan Shay in 1994 and outlines 3 necessarycomponents, viewing the violator as a powerholder: (1) betrayal of what is right, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high stakes situation.7 Litz and colleagues describe moral injury another way: “Perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”8 The violator is posited to be either the self or others.

Rather than representing “self” or “other” imposed moral injury, we propose the 2 definitions are related as exposure (ie, the perceived betrayal) and response (ie, the resulting transgression). An individual who experiences a betrayal by a legitimate authority has an opportunity to choose their response. They may acquiesce and transgress their moral beliefs (eg, their oath to provide ethical health care), or they could refuse, by speaking out, or in some way resisting the authority’s betrayal. The case of Ray Brovont is a useful illustration of reconciling the definitions (Box).9

Myriad factors—known as potentially morally injurious events—drive moral injury, such as resource-constrained decision making, witnessing the behaviors of colleagues that violate deeply held moral beliefs, questionable billing practices, and more. Each begins with a betrayal. Spotlighting the betrayal, refusing to perpetuate it, or taking actions toward change, may reduce the risk of experiencing moral injury.9 Conversely, acquiescing and transgressing one’s oath, the profession’s covenant with society, increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.8

Many HCPs believe they are not always free to resist betrayal, fearing retaliation, job loss, blacklisting, or worse. They feel constrained by debt accrued while receiving their education, being their household’s primary earner, community ties, practicing a niche specialty that requires working for a tertiary referral center, or perhaps believing the situation will be the same elsewhere. To not stand up or speak out is to choose complicity with corporate greed that uses HCPs to undermine their professional duties, which significantly increases the risk of experiencing moral injury.

MORAL INJURY AND BURNOUT

In addition to reconciling the definitions of moral injury, the relationship between moral injury and burnout are still being elucidated. We suggest that moral injury and burnout represent independent and potentially interrelated pathways to distress (Figure). Exposure to chronic, inconsonant, and transactional demands, which things like shorter work hours, better self-care, or improved health system operations might mitigate, manifests as burnout. In contrast, moral injury arises when a superior’s actions or a system’s policies and practices—such as justifiable but unnecessary testing, or referral restrictions to prevent revenue leakage—undermine one’s professional obligations to prioritize the patient’s best interest.

If concerns from HCPs about transactional demands are persistently dismissed, such inaction may be perceived as a betrayal, raising the risk of moral injury. Additionally, the resignation or helplessness of moral injury perceived as inescapable may present with emotional exhaustion, ineffectiveness, and depersonalization, all hallmarks of burnout. Both conditions can mediate and moderate the relationship between triggers for workplace distress and resulting psychological, physical, and existential harm.

CONCLUSIONS

Moral injury is increasingly recognized as a source of distress among HCPs, resulting from structural constraints on their ability to deliver optimal care and their own unwillingness to stand up for their patients, their oaths, and their professions.1 Unlike the military, where moral injury is inherent in the contract with society, moral injury in health care (and the relational rupture it connotes) is a signal of systemic dysfunction, fractured trust, and the need for relational repair.

Health care is at a crossroads, experiencing a workforce retention crisis while simultaneously predicting a significant increase in care needs by Baby Boomers over the next 3 decades.

Health care does not have the luxury of experimenting another 30 years with interventions that have limited impact. We must design a new generation of approaches, shaped by lessons learned from the pandemic while acknowledging that prepandemic standards were already failing the workforce. A unified definition of moral injury must be integrated to frame clinician distress alongside burnout, recentering ethical decision making, rather than profit, at the heart of health care. Harmonizing the definitions of moral injury and clarifying the relationship of moral injury with burnout reduces the need for further reinterpretations, allowing for more robust, easily comparable studies focused on identifying risk factors, as well as rapidly implementing effective mitigation strategies.

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

1. Griffin BJ, Weber MC, Hinkson KD, et al. Toward a dimensional contextual model of moral injury: a scoping review on healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psych. 2023;10:199-216. doi:10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on Systems Approaches to Improve Patient Care by Supporting Clinician Well-Being. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: A Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. The National Academies Press; 2019. doi:10.17226/25521

3. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

4. Gardner HE, Schulman LS. The professions in America today: crucial but fragile. Daedalus. 2005;134(3):13-18. doi:10.1162/0011526054622132

5. Fuchs VR. Major trends in the U.S. health economy since 1950. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):973-977. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1200478

6. Molendijk T. Warnings against romanticising moral injury. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;220(1):1-3. doi:10.1192/bjp.2021.114

7. Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychol. 2014;31(2):182-191. doi:10.1037/a0036090

8. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

9. Brovont v KS-I Med. Servs., P.A., 622 SW3d 671 (Mo Ct App 2020).

Graduate Medical Education Financing in the US Department of Veterans Affairs

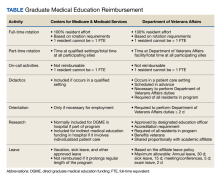

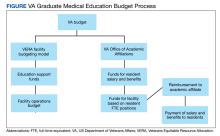

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has partnered with academic medical centers and programs since 1946 to provide clinical training for physician residents. Ranking second in federal graduate medical education (GME) funding to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the $850 million VA GME budget annually reimburses > 250 GME-sponsoring institutions (affiliates) of 8000 GME programs for the clinical training of 49,000 individual residents rotating through > 11,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions.1 The VA also distributes $1.6 billion to VA facilities to offset the costs of conducting health professions education (HPE) (eg, facility infrastructure, salary support for VA instructors and preceptors, education office administration, and instructional equipment).2 The VA financial and educational contributions account for payment of 11% of resident positions nationally and allow academic medical centers to be less reliant on CMS GME funding.3,4 The VA contributions also provide opportunities for GME expansion,1,5,6 educational innovations,5,7 interprofessional and team-based care,8,9 and quality and safety training.10,11 The Table provides a comparison of CMS and VA GME reimbursability based on activity.

GME financing is complex, particularly the formulaic approach used by CMS, the details of which are often obscured in federal regulations. Due to this complexity and the $16 billion CMS GME budget, academic publications have focused on CMS GME financing while not fully explaining the VA GME policies and processes.4,12-14 By comparison, the VA GME financing model is relatively straightforward and governed by different statues and VA regulations, yet sharing some of the same principles as CMS regulations. Given the challenges in CMS reimbursement to fully support the cost of resident education, as well as the educational opportunities at the VA, the VA designs its reimbursement model to assure that affiliates receive appropriate payments.4,12,15 To ensure the continued success of VA GME partnerships, knowledge of VA GME financing has become increasingly important for designated institutional officers (DIOs) and residency program directors, particularly in light of recent investigations into oversight of the VA’s reimbursement to academic affiliates.

VA AUTHORITY

While the VA’s primary mission is “to provide a complete hospital medical service for the medical care and treatment of veterans,” early VA leaders recognized the importance of affiliating with the nation’s academic institutions.19 In 1946, the VA Policy Memorandum Number 2 established a partnership between the VA and the academic medical community.20 Additional legislation authorized specific agreements with academic affiliates for the central administration of salary and benefits for residents rotating at VA facilities. This process, known as disbursement, is an alternative payroll mechanism whereby the VA reimburses the academic affiliate for resident salary and benefits and the affiliate acts as the disbursing agent, issuing paychecks to residents.21,22

Resident FUNDING

By policy, with rare exceptions, the VA does not sponsor residency programs due to the challenges of providing an appropriate patient mix of age, sex, and medical conditions to meet accreditation standards.4 Nearly all VA reimbursements are for residents in affiliate-sponsored programs, while just 1% pays for residents in legacy, VA-sponsored residency programs at 2 VA facilities. The VA budget for resident (including fellows) salary and benefits is managed by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the national VA office responsible for oversight, policy, and funding of VA HPE programs.

Resident Salaries and Benefits

VA funding of resident salary and benefits are analogous with CMS direct GME (DGME), which is designed to cover resident salary and benefits costs.4,14,23 CMS DGME payments depend on a hospital’s volume of CMS inpatients and are based on a statutory formula, which uses the hospital’s resident FTE positions, the per-resident amount, and Medicare’s share of inpatient beds (Medicare patient load) to determine payments.12 The per-resident amount is set by statute, varies geographically, and is calculated by dividing the hospital’s allowable costs of GME (percentage of CMS inpatient days) divided by the number of residents.12,24

By comparison, the VA GME payment reimburses for each FTE based on the salary and benefits rate set by the academic affiliate. Reimbursement is calculated based on resident time spent at the VA multiplied by a daily salary rate. The daily salary rate is determined by dividing the resident’s total compensation (salary and benefits) by the number of calendar days in an academic year. Resident time spent at the VA facility is determined by obtaining rotation schedules provided by the academic affiliate and verifying resident clinical and educational activity during scheduled rotations.

Indirect Medical Education Funding

In addition to resident salary and benefits, funds to offset the cost of conducting HPE are provided to VA facilities. These funds are intended to improve and maintain necessary infrastructure for all HPE programs not just GME, including education office administration needs, teaching costs (ie, a portion of VA preceptors salary), and instructional equipment.

The Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) is a national budgeting process for VA medical facilities that funds facility operational needs such as staff salary and benefits, infrastructure, and equipment.2 The education portion of the VERA, the VERA Education Support Component (VESC), is not managed by the OAA, but rather is distributed through the VERA model to the general budget of VA facilities hosting HPE (Figure). VESC funding in the VA budget is based on labor mapping of physician time spent in education; other labor mapping categories include clinical care, research, and administration. VA facility VESC funding is calculated based on the number of paid health profession trainees (HPTs) from all professions, apportioned according to the number of FTEs for physician residents and VA-paid HPTs in other disciplines. In fiscal year 2024, VA facilities received $115,812 for each physician resident FTE position and $84,906 for each VA-paid, non-GME FTE position.

The VESC is like CMS's indirect GME funding, termed Indirect Medical Education (IME), an additional payment for each Medicare patient discharged reflecting teaching hospitals’ higher patient care costs relative to nonteaching hospitals. Described elsewhere, IME is calculated using a resident-to-bed ratio and a multiplier, which is set by statute.4,25 While IME can be used for reimbursement for some resident clinical and educational activities(eg, research), VA VESC funds cannot be used for such activities and are part of the general facility budget and appropriated per the discretion of the medical facility director.

ESTABLISHING GME PARTNERSHIPS

An affiliation agreement establishes the administrative and legal requirements for educational relationships with academic affiliates and includes standards for conducting HPE, responsibilities for accreditation standards, program leadership, faculty, resources, supervision, academic policies, and procedures. The VA uses standardized affiliation agreement templates that have been vetted with accrediting bodies and the VA Office of General Counsel.

A disbursement agreement authorizes the VA to reimburse affiliates for resident salary and benefits for VA clinical and educational activities. The disbursement agreement details the fiscal arrangements (eg, payment in advance vs arrears, salary, and benefit rates, leave) for the reimbursement payments. Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1400.05 provides the policy and procedures for calculating reimbursement for HPT educational activities.26

The VA facility designated education officer (DEO) oversees all HPE programs and coordinates the affiliation and disbursement agreement processes.27 The DEO, affiliate DIO, residency program director, and VA residency site director determine the physician resident FTE positions assigned to a VA facility based on educational objectives and availability of educational resources at the VA facility, such as patient care opportunities, faculty supervisors, space, and equipment. The VA facility requests for resident FTE positions are submitted to the OAA by the facility DEO.

Once GME FTE positions are approved by the OAA, VA facilities work with their academic affiliate to submit the physician resident salary and benefit rate. Affiliate DIOs attest to the accuracy of the salary rate schedule and the local DEO submits the budget request to the OAA. Upon approval, the funds are transferred to the VA facility each fiscal year, which begins October 1. DEOs report quarterly to the OAA both budget needs and excesses based on variations in the approved FTEs due to additional VA rotations, physician resident attrition, or reassignment.

Resident Position Allocation

VA GME financing provides flexibility through periodic needs assessments and expansion initiatives. In August and December, DEOs collaborate with an academic affiliate to submit reports to the OAA confirming their projected GME needs for the next academic year. Additional positions requests are reviewed by the OAA; funding depends on budget and the educational justification. The OAA periodically issues GME expansion requests for proposal, which typically arise from legislation to address specific VA workforce needs. The VA facility DEO and affiliate GME leaders collaborate to apply for additional positions. For example, a VA GME expansion under the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 added 1500 GME positions in 8 years for critically needed specialties and in rural and underserved areas.5 The Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Outside Networks (MISSION) Act of 2018 authorized a pilot program for VA to fund residents at non-VA facilities with priority for Indian Health Services, Tribes and Tribal Organizations, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and US Department of Defense facilities to provide access to veterans in underserved areas.6

The VA GME financing system has flexibility to meet local needs for additional resident positions and to address broader VA workforce gaps through targeted expansion. Generally, CMS does not fund positions to address workforce needs, place residents in specific geographic areas, or require the training of certain types of residents.4 However, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 has provided the opportunity to address rural workforce needs.28

Reimbursement

The VA provides reimbursement for clinical and educational activities performed in VA facilities for the benefit of veterans as well as research, didactics, meetings and conferences, annual and sick leave, and orientation. The VA also may provide reimbursement for educational activities that occur off VA grounds (eg, the VA proportional share of a residency program’s didactic sessions). The VA does not reimburse for affiliate clinical duties or administrative costs, although a national policy allows VA facilities to reimburse affiliates for some GME overhead costs.29