User login

COVID-19: New guidance to stem mental health crisis in frontline HCPs

A new review offers fresh guidance to help stem the mental health toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline clinicians.

Investigators gathered practice guidelines and resources from a wide range of health care organizations and professional societies to develop a conceptual framework of mental health support for health care professionals (HCPs) caring for COVID-19 patients.

“Support needs to be deployed in multiple dimensions – including individual, organizational, and societal levels – and include training in resilience, stress reduction, emotional awareness, and self-care strategies,” lead author Rachel Schwartz, PhD, health services researcher, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

The review was published Aug. 21 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

An opportune moment

Coauthor Rebecca Margolis, DO, director of well-being in the division of medical education and faculty development, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, said that this is “an opportune moment to look at how we treat frontline providers in this country.”

Studies of previous pandemics have shown heightened distress in HCPs, even years after the pandemic, and the unique challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic surpass those of previous pandemics, Dr. Margolis said in an interview.

Dr. Schwartz, Dr. Margolis, and coauthors Uma Anand, PhD, LP, and Jina Sinskey, MD, met through the Collaborative for Healing and Renewal in Medicine network, a group of medical educators, leaders in academic medicine, experts in burnout research and interventions, and trainees working together to promote well-being among trainees and practicing physicians.

“We were brought together on a conference call in March, when things were particularly bad in New York, and started looking to see what resources we could get to frontline providers who were suffering. It was great to lean on each other and stand on the shoulders of colleagues in New York, who were the ones we learned from on these calls,” said Dr. Margolis.

The authors recommended addressing clinicians’ basic practical needs, including ensuring essentials like meals and transportation, establishing a “well-being area” within hospitals for staff to rest, and providing well-stocked living quarters so clinicians can safely quarantine from family, as well as personal protective equipment and child care.

Clinicians are often asked to “assume new professional roles to meet evolving needs” during a pandemic, which can increase stress. The authors recommended targeted training, assessment of clinician skills before redeployment to a new clinical role, and clear communication practices around redeployment.

Recognition from hospital and government leaders improves morale and supports clinicians’ ability to continue delivering care. Leadership should “leverage communication strategies to provide clinicians with up-to-date information and reassurance,” they wrote.

‘Uniquely isolated’

Dr. Margolis noted that

“My colleagues feel a sense of moral injury, putting their lives on the line at work, performing the most perilous job, and their kids can’t hang out with other kids, which just puts salt on the wound,” she said.

Additional sources of moral injury are deciding which patients should receive life support in the event of inadequate resources and bearing witness to, or enforcing, policies that lead to patients dying alone.

Leaders should encourage clinicians to “seek informal support from colleagues, managers, or chaplains” and to “provide rapid access to professional help,” the authors noted.

Furthermore, they contended that leaders should “proactively and routinely monitor the psychological well-being of their teams,” since guilt and shame often prevent clinicians from disclosing feelings of moral injury.

“Being provided with routine mental health support should be normalized and it should be part of the job – not only during COVID-19 but in general,” Dr. Schwartz said.

‘Battle buddies’

Dr. Margolis recommended the “battle buddy” model for mutual peer support.

Dr. Anand, a mental health clinician at Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., elaborated.

“We connect residents with each other, and they form pairs to support each other and watch for warning signs such as withdrawal from colleagues, being frequently tearful, not showing up at work or showing up late, missing assignments, making mistakes at work, increased use of alcohol, or verbalizing serious concerns,” Dr. Anand said.

If the buddy shows any of these warning signs, he or she can be directed to appropriate resources to get help.

Since the pandemic has interfered with the ability to connect with colleagues and family members, attention should be paid to addressing the social support needs of clinicians.

Dr. Anand suggested that clinicians maintain contact with counselors, friends, and family, even if they cannot be together in person and must connect “virtually.”

Resilience and strength training are “key” components of reducing clinician distress, but trainings as well as processing groups and support workshops should be offered during protected time, Dr. Margolis advised, since it can be burdensome for clinicians to wake up early or stay late to attend these sessions.

Leaders and administrators should “model self-care and well-being,” she noted. For example, sending emails to clinicians late at night or on weekends creates an expectation of a rapid reply, which leads to additional pressure for the clinician.

“This is of the most powerful unspoken curricula we can develop,” Dr. Margolis emphasized.

Self-care critical

Marcus S. Shaker, MD, MSc, associate professor of pediatrics, medicine, and community and family medicine, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said the study was “a much appreciated, timely reminder of the importance of clinician wellness.”

Moreover, “without self-care, our ability to help our patients withers. This article provides a useful conceptual framework for individuals and organizations to provide the right care at the right time in these unprecedented times,” said Dr. Shaker, who was not involved with the study.

The authors agreed, stating that clinicians “require proactive psychological protection specifically because they are a population known for putting others’ needs before their own.”

They recommended several resources for HCPs, including the Physician Support Line; Headspace, a mindfulness Web-based app for reducing stress and anxiety; the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline; and the Crisis Text Line.

The authors and Dr. Shaker disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new review offers fresh guidance to help stem the mental health toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline clinicians.

Investigators gathered practice guidelines and resources from a wide range of health care organizations and professional societies to develop a conceptual framework of mental health support for health care professionals (HCPs) caring for COVID-19 patients.

“Support needs to be deployed in multiple dimensions – including individual, organizational, and societal levels – and include training in resilience, stress reduction, emotional awareness, and self-care strategies,” lead author Rachel Schwartz, PhD, health services researcher, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

The review was published Aug. 21 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

An opportune moment

Coauthor Rebecca Margolis, DO, director of well-being in the division of medical education and faculty development, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, said that this is “an opportune moment to look at how we treat frontline providers in this country.”

Studies of previous pandemics have shown heightened distress in HCPs, even years after the pandemic, and the unique challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic surpass those of previous pandemics, Dr. Margolis said in an interview.

Dr. Schwartz, Dr. Margolis, and coauthors Uma Anand, PhD, LP, and Jina Sinskey, MD, met through the Collaborative for Healing and Renewal in Medicine network, a group of medical educators, leaders in academic medicine, experts in burnout research and interventions, and trainees working together to promote well-being among trainees and practicing physicians.

“We were brought together on a conference call in March, when things were particularly bad in New York, and started looking to see what resources we could get to frontline providers who were suffering. It was great to lean on each other and stand on the shoulders of colleagues in New York, who were the ones we learned from on these calls,” said Dr. Margolis.

The authors recommended addressing clinicians’ basic practical needs, including ensuring essentials like meals and transportation, establishing a “well-being area” within hospitals for staff to rest, and providing well-stocked living quarters so clinicians can safely quarantine from family, as well as personal protective equipment and child care.

Clinicians are often asked to “assume new professional roles to meet evolving needs” during a pandemic, which can increase stress. The authors recommended targeted training, assessment of clinician skills before redeployment to a new clinical role, and clear communication practices around redeployment.

Recognition from hospital and government leaders improves morale and supports clinicians’ ability to continue delivering care. Leadership should “leverage communication strategies to provide clinicians with up-to-date information and reassurance,” they wrote.

‘Uniquely isolated’

Dr. Margolis noted that

“My colleagues feel a sense of moral injury, putting their lives on the line at work, performing the most perilous job, and their kids can’t hang out with other kids, which just puts salt on the wound,” she said.

Additional sources of moral injury are deciding which patients should receive life support in the event of inadequate resources and bearing witness to, or enforcing, policies that lead to patients dying alone.

Leaders should encourage clinicians to “seek informal support from colleagues, managers, or chaplains” and to “provide rapid access to professional help,” the authors noted.

Furthermore, they contended that leaders should “proactively and routinely monitor the psychological well-being of their teams,” since guilt and shame often prevent clinicians from disclosing feelings of moral injury.

“Being provided with routine mental health support should be normalized and it should be part of the job – not only during COVID-19 but in general,” Dr. Schwartz said.

‘Battle buddies’

Dr. Margolis recommended the “battle buddy” model for mutual peer support.

Dr. Anand, a mental health clinician at Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., elaborated.

“We connect residents with each other, and they form pairs to support each other and watch for warning signs such as withdrawal from colleagues, being frequently tearful, not showing up at work or showing up late, missing assignments, making mistakes at work, increased use of alcohol, or verbalizing serious concerns,” Dr. Anand said.

If the buddy shows any of these warning signs, he or she can be directed to appropriate resources to get help.

Since the pandemic has interfered with the ability to connect with colleagues and family members, attention should be paid to addressing the social support needs of clinicians.

Dr. Anand suggested that clinicians maintain contact with counselors, friends, and family, even if they cannot be together in person and must connect “virtually.”

Resilience and strength training are “key” components of reducing clinician distress, but trainings as well as processing groups and support workshops should be offered during protected time, Dr. Margolis advised, since it can be burdensome for clinicians to wake up early or stay late to attend these sessions.

Leaders and administrators should “model self-care and well-being,” she noted. For example, sending emails to clinicians late at night or on weekends creates an expectation of a rapid reply, which leads to additional pressure for the clinician.

“This is of the most powerful unspoken curricula we can develop,” Dr. Margolis emphasized.

Self-care critical

Marcus S. Shaker, MD, MSc, associate professor of pediatrics, medicine, and community and family medicine, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said the study was “a much appreciated, timely reminder of the importance of clinician wellness.”

Moreover, “without self-care, our ability to help our patients withers. This article provides a useful conceptual framework for individuals and organizations to provide the right care at the right time in these unprecedented times,” said Dr. Shaker, who was not involved with the study.

The authors agreed, stating that clinicians “require proactive psychological protection specifically because they are a population known for putting others’ needs before their own.”

They recommended several resources for HCPs, including the Physician Support Line; Headspace, a mindfulness Web-based app for reducing stress and anxiety; the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline; and the Crisis Text Line.

The authors and Dr. Shaker disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new review offers fresh guidance to help stem the mental health toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on frontline clinicians.

Investigators gathered practice guidelines and resources from a wide range of health care organizations and professional societies to develop a conceptual framework of mental health support for health care professionals (HCPs) caring for COVID-19 patients.

“Support needs to be deployed in multiple dimensions – including individual, organizational, and societal levels – and include training in resilience, stress reduction, emotional awareness, and self-care strategies,” lead author Rachel Schwartz, PhD, health services researcher, Stanford (Calif.) University, said in an interview.

The review was published Aug. 21 in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

An opportune moment

Coauthor Rebecca Margolis, DO, director of well-being in the division of medical education and faculty development, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, said that this is “an opportune moment to look at how we treat frontline providers in this country.”

Studies of previous pandemics have shown heightened distress in HCPs, even years after the pandemic, and the unique challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic surpass those of previous pandemics, Dr. Margolis said in an interview.

Dr. Schwartz, Dr. Margolis, and coauthors Uma Anand, PhD, LP, and Jina Sinskey, MD, met through the Collaborative for Healing and Renewal in Medicine network, a group of medical educators, leaders in academic medicine, experts in burnout research and interventions, and trainees working together to promote well-being among trainees and practicing physicians.

“We were brought together on a conference call in March, when things were particularly bad in New York, and started looking to see what resources we could get to frontline providers who were suffering. It was great to lean on each other and stand on the shoulders of colleagues in New York, who were the ones we learned from on these calls,” said Dr. Margolis.

The authors recommended addressing clinicians’ basic practical needs, including ensuring essentials like meals and transportation, establishing a “well-being area” within hospitals for staff to rest, and providing well-stocked living quarters so clinicians can safely quarantine from family, as well as personal protective equipment and child care.

Clinicians are often asked to “assume new professional roles to meet evolving needs” during a pandemic, which can increase stress. The authors recommended targeted training, assessment of clinician skills before redeployment to a new clinical role, and clear communication practices around redeployment.

Recognition from hospital and government leaders improves morale and supports clinicians’ ability to continue delivering care. Leadership should “leverage communication strategies to provide clinicians with up-to-date information and reassurance,” they wrote.

‘Uniquely isolated’

Dr. Margolis noted that

“My colleagues feel a sense of moral injury, putting their lives on the line at work, performing the most perilous job, and their kids can’t hang out with other kids, which just puts salt on the wound,” she said.

Additional sources of moral injury are deciding which patients should receive life support in the event of inadequate resources and bearing witness to, or enforcing, policies that lead to patients dying alone.

Leaders should encourage clinicians to “seek informal support from colleagues, managers, or chaplains” and to “provide rapid access to professional help,” the authors noted.

Furthermore, they contended that leaders should “proactively and routinely monitor the psychological well-being of their teams,” since guilt and shame often prevent clinicians from disclosing feelings of moral injury.

“Being provided with routine mental health support should be normalized and it should be part of the job – not only during COVID-19 but in general,” Dr. Schwartz said.

‘Battle buddies’

Dr. Margolis recommended the “battle buddy” model for mutual peer support.

Dr. Anand, a mental health clinician at Mayo Medical School, Rochester, Minn., elaborated.

“We connect residents with each other, and they form pairs to support each other and watch for warning signs such as withdrawal from colleagues, being frequently tearful, not showing up at work or showing up late, missing assignments, making mistakes at work, increased use of alcohol, or verbalizing serious concerns,” Dr. Anand said.

If the buddy shows any of these warning signs, he or she can be directed to appropriate resources to get help.

Since the pandemic has interfered with the ability to connect with colleagues and family members, attention should be paid to addressing the social support needs of clinicians.

Dr. Anand suggested that clinicians maintain contact with counselors, friends, and family, even if they cannot be together in person and must connect “virtually.”

Resilience and strength training are “key” components of reducing clinician distress, but trainings as well as processing groups and support workshops should be offered during protected time, Dr. Margolis advised, since it can be burdensome for clinicians to wake up early or stay late to attend these sessions.

Leaders and administrators should “model self-care and well-being,” she noted. For example, sending emails to clinicians late at night or on weekends creates an expectation of a rapid reply, which leads to additional pressure for the clinician.

“This is of the most powerful unspoken curricula we can develop,” Dr. Margolis emphasized.

Self-care critical

Marcus S. Shaker, MD, MSc, associate professor of pediatrics, medicine, and community and family medicine, Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock in Lebanon, N.H., and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., said the study was “a much appreciated, timely reminder of the importance of clinician wellness.”

Moreover, “without self-care, our ability to help our patients withers. This article provides a useful conceptual framework for individuals and organizations to provide the right care at the right time in these unprecedented times,” said Dr. Shaker, who was not involved with the study.

The authors agreed, stating that clinicians “require proactive psychological protection specifically because they are a population known for putting others’ needs before their own.”

They recommended several resources for HCPs, including the Physician Support Line; Headspace, a mindfulness Web-based app for reducing stress and anxiety; the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline; and the Crisis Text Line.

The authors and Dr. Shaker disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Rash, muscle weakness, and confusion

The constellation of symptoms was suggestive of Lyme disease, although connective tissue disease and syphilis were also considered. Two punch biopsies were performed in the office, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody panel, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) laboratory tests were ordered.

Immediately available laboratory results included ESR, CBC, INR, and CMP. Findings were notable for elevated INR, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase. The transaminitis suggested myopathy and was consistent with clinical muscle weakness. RPR testing was negative.

Because of the confusion, severity of muscle weakness, and plausibility of early encephalopathy with Lyme disease, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Lumbar puncture was delayed until his INR was reduced, but subsequently was found to be normal. He received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (2 g/d) empirically for possible early disseminated disease with neurologic complications. His confusion, muscle weakness, and transaminitis rapidly improved.

His Lyme antibody panel was positive for IgM after his third day of hospitalization. A reflexive confirmatory western blot for IgG was not positive on the initial set of labs but was positive when redrawn 4 weeks after this hospitalization, confirming Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne disease caused by the Borrelia genus of spirochete bacteria, most commonly Borrelia burgdorferi in North America. Transmission occurs through prolonged (typically 36-48 hours) attachment of a blacklegged tick.

The disease can be divided into 3 stages:

- localized (3-30 days): erythema migrans rash and flulike illness

- early disseminated (days to weeks; seen in this patient): multiple erythema migrans rashes, early neuroborreliosis, arthritis, carditis, and rarely hepatitis and uveitis

- late disseminated (months to years): chronic Lyme arthritis, chronic neurological disorders (eg, encephalopathy, radicular pain, and chronic neuropathy).

The initial erythema migrans rash is classically red and targetoid; it expands from the site of attachment. Early disseminated patches tend to be smaller and can occur on any body part. The rash is rarely itchy or painful but may be warm to the touch or sensitive. The rash resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 weeks of onset.

Treatment of all early and early disseminated Lyme disease typically involves a 14- to 28-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid for adults, 2.2 mg/kg bid [maximum 100 mg bid] for children). Patients with acute neurologic disease often can be treated with doxycycline, but patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline and those with parenchymal disease such as encephalitis should receive IV therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g/d.

In this case, the patient was discharged home on a 3-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and cleared without further symptoms.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

The constellation of symptoms was suggestive of Lyme disease, although connective tissue disease and syphilis were also considered. Two punch biopsies were performed in the office, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody panel, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) laboratory tests were ordered.

Immediately available laboratory results included ESR, CBC, INR, and CMP. Findings were notable for elevated INR, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase. The transaminitis suggested myopathy and was consistent with clinical muscle weakness. RPR testing was negative.

Because of the confusion, severity of muscle weakness, and plausibility of early encephalopathy with Lyme disease, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Lumbar puncture was delayed until his INR was reduced, but subsequently was found to be normal. He received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (2 g/d) empirically for possible early disseminated disease with neurologic complications. His confusion, muscle weakness, and transaminitis rapidly improved.

His Lyme antibody panel was positive for IgM after his third day of hospitalization. A reflexive confirmatory western blot for IgG was not positive on the initial set of labs but was positive when redrawn 4 weeks after this hospitalization, confirming Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne disease caused by the Borrelia genus of spirochete bacteria, most commonly Borrelia burgdorferi in North America. Transmission occurs through prolonged (typically 36-48 hours) attachment of a blacklegged tick.

The disease can be divided into 3 stages:

- localized (3-30 days): erythema migrans rash and flulike illness

- early disseminated (days to weeks; seen in this patient): multiple erythema migrans rashes, early neuroborreliosis, arthritis, carditis, and rarely hepatitis and uveitis

- late disseminated (months to years): chronic Lyme arthritis, chronic neurological disorders (eg, encephalopathy, radicular pain, and chronic neuropathy).

The initial erythema migrans rash is classically red and targetoid; it expands from the site of attachment. Early disseminated patches tend to be smaller and can occur on any body part. The rash is rarely itchy or painful but may be warm to the touch or sensitive. The rash resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 weeks of onset.

Treatment of all early and early disseminated Lyme disease typically involves a 14- to 28-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid for adults, 2.2 mg/kg bid [maximum 100 mg bid] for children). Patients with acute neurologic disease often can be treated with doxycycline, but patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline and those with parenchymal disease such as encephalitis should receive IV therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g/d.

In this case, the patient was discharged home on a 3-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and cleared without further symptoms.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

The constellation of symptoms was suggestive of Lyme disease, although connective tissue disease and syphilis were also considered. Two punch biopsies were performed in the office, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), complete blood cell count (CBC), international normalized ratio (INR), comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), Lyme enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) antibody panel, and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) laboratory tests were ordered.

Immediately available laboratory results included ESR, CBC, INR, and CMP. Findings were notable for elevated INR, as well as elevated alanine aminotransferase and aspartate transaminase. The transaminitis suggested myopathy and was consistent with clinical muscle weakness. RPR testing was negative.

Because of the confusion, severity of muscle weakness, and plausibility of early encephalopathy with Lyme disease, the patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up. Lumbar puncture was delayed until his INR was reduced, but subsequently was found to be normal. He received intravenous (IV) ceftriaxone (2 g/d) empirically for possible early disseminated disease with neurologic complications. His confusion, muscle weakness, and transaminitis rapidly improved.

His Lyme antibody panel was positive for IgM after his third day of hospitalization. A reflexive confirmatory western blot for IgG was not positive on the initial set of labs but was positive when redrawn 4 weeks after this hospitalization, confirming Lyme disease.

Lyme disease is a vector-borne disease caused by the Borrelia genus of spirochete bacteria, most commonly Borrelia burgdorferi in North America. Transmission occurs through prolonged (typically 36-48 hours) attachment of a blacklegged tick.

The disease can be divided into 3 stages:

- localized (3-30 days): erythema migrans rash and flulike illness

- early disseminated (days to weeks; seen in this patient): multiple erythema migrans rashes, early neuroborreliosis, arthritis, carditis, and rarely hepatitis and uveitis

- late disseminated (months to years): chronic Lyme arthritis, chronic neurological disorders (eg, encephalopathy, radicular pain, and chronic neuropathy).

The initial erythema migrans rash is classically red and targetoid; it expands from the site of attachment. Early disseminated patches tend to be smaller and can occur on any body part. The rash is rarely itchy or painful but may be warm to the touch or sensitive. The rash resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 weeks of onset.

Treatment of all early and early disseminated Lyme disease typically involves a 14- to 28-day course of doxycycline (100 mg bid for adults, 2.2 mg/kg bid [maximum 100 mg bid] for children). Patients with acute neurologic disease often can be treated with doxycycline, but patients who cannot tolerate doxycycline and those with parenchymal disease such as encephalitis should receive IV therapy with ceftriaxone 2 g/d.

In this case, the patient was discharged home on a 3-week course of doxycycline 100 mg bid and cleared without further symptoms.

Text courtesy of Tristan Reynolds, DO, Maine Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, and Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

Lyme disease. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/healthcare/index.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

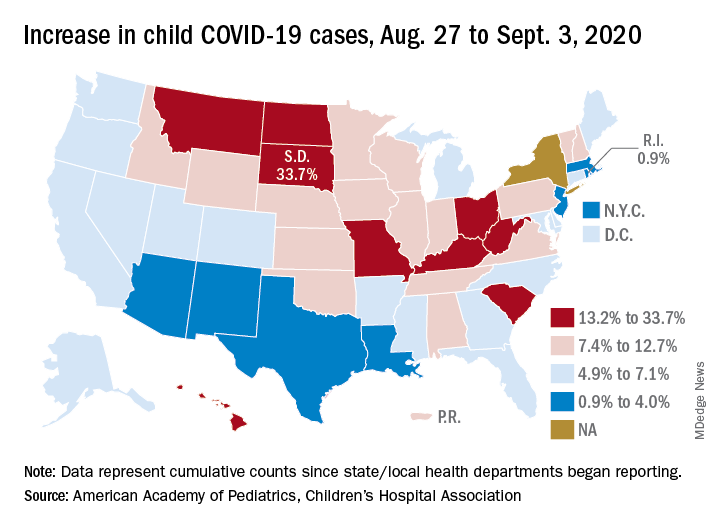

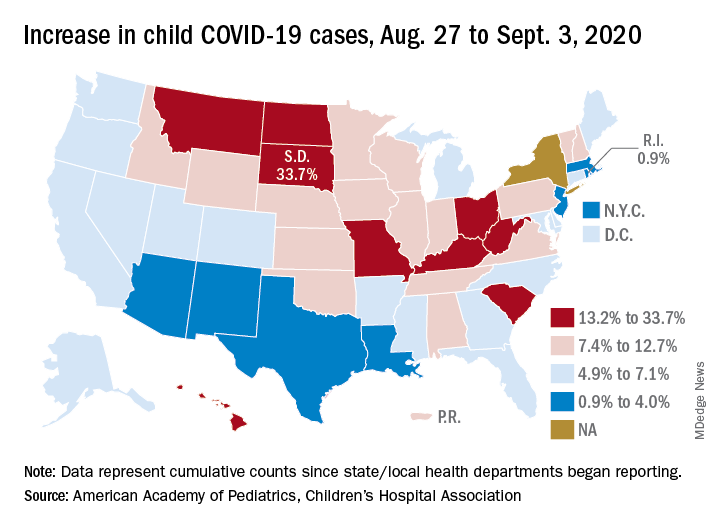

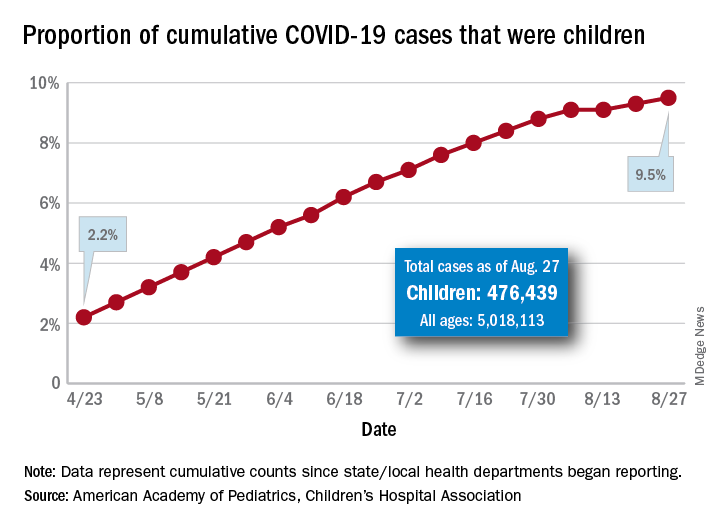

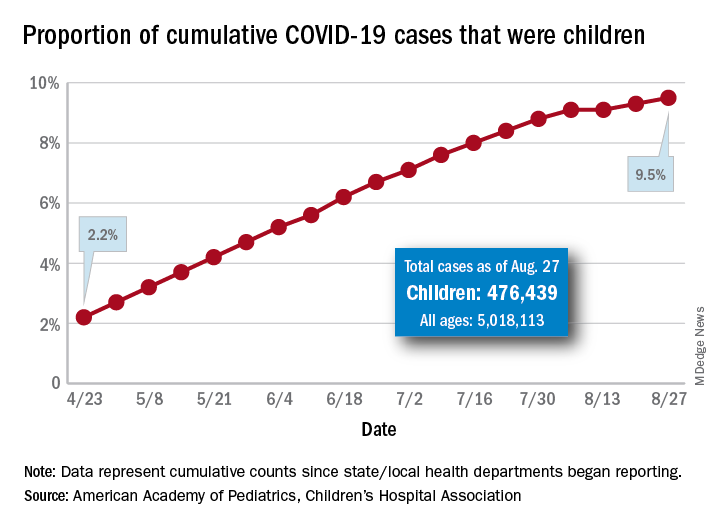

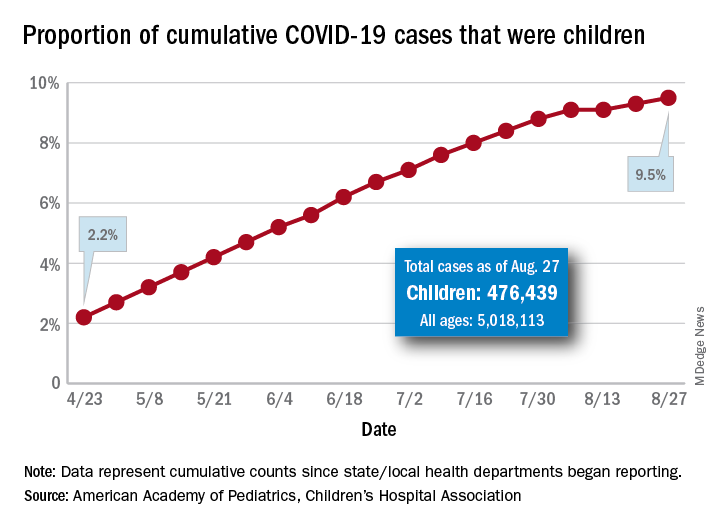

U.S. tops 500,000 COVID-19 cases in children

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

States have reported 513,415 cases of COVID-19 in children since the beginning of the pandemic, with almost 37,000 coming in the last week, the AAP and the CHA said Sept. 8 in the weekly report. That figure includes New York City – the rest of New York State is not reporting ages for COVID-19 patients – as well as Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and Guam.

“These numbers are a chilling reminder of why we need to take this virus seriously,” AAP President Sara Goza, MD, said in a written statement.

Children now represent 9.8% of the almost 5.3 million cases that have been reported in Americans of all ages. The proportion of child cases has continued to increase as the pandemic has progressed – it was 8.0% as of mid-July and 5.2% in early June, the data show.

“Throughout the summer, surges in the virus have occurred in Southern, Western, and Midwestern states,” the AAP statement said.

The latest AAP/CHA report shows that, from Aug. 27 to Sept. 3, the total number of child cases jumped by 33.7% in South Dakota, more than any other state. North Dakota was next at 22.7%, followed by Hawaii (18.1%), Missouri (16.8%), and Kentucky (16.4%).

“This rapid rise in positive cases occurred over the summer, and as the weather cools, we know people will spend more time indoors,” said Sean O’Leary, MD, MPH, vice chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases. “The goal is to get children back into schools for in-person learning, but in many communities, this is not possible as the virus spreads unchecked.”

The smallest increase over the last week, just 0.9%, came in Rhode Island, with Massachusetts just a bit higher at 1.0%. Also at the low end of the increase scale are Arizona (3.3%) and Louisiana (4.0%), two states that have very high rates of cumulative cases: 1,380 per 100,000 children for Arizona and 1,234 per 100,000 for Louisiana, the report said.

To give those figures some context, Tennessee has the highest cumulative count of any state at 1,553 cases per 100,000 children and Vermont has the lowest at 151, based on the data gathered by the AAP and CHA.

“While much remains unknown about COVID-19, we do know that the spread among children reflects what is happening in the broader communities. A disproportionate number of cases are reported in Black and Hispanic children and in places where there is high poverty. We must work harder to address societal inequities that contribute to these disparities,” Dr. Goza said.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

States have reported 513,415 cases of COVID-19 in children since the beginning of the pandemic, with almost 37,000 coming in the last week, the AAP and the CHA said Sept. 8 in the weekly report. That figure includes New York City – the rest of New York State is not reporting ages for COVID-19 patients – as well as Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and Guam.

“These numbers are a chilling reminder of why we need to take this virus seriously,” AAP President Sara Goza, MD, said in a written statement.

Children now represent 9.8% of the almost 5.3 million cases that have been reported in Americans of all ages. The proportion of child cases has continued to increase as the pandemic has progressed – it was 8.0% as of mid-July and 5.2% in early June, the data show.

“Throughout the summer, surges in the virus have occurred in Southern, Western, and Midwestern states,” the AAP statement said.

The latest AAP/CHA report shows that, from Aug. 27 to Sept. 3, the total number of child cases jumped by 33.7% in South Dakota, more than any other state. North Dakota was next at 22.7%, followed by Hawaii (18.1%), Missouri (16.8%), and Kentucky (16.4%).

“This rapid rise in positive cases occurred over the summer, and as the weather cools, we know people will spend more time indoors,” said Sean O’Leary, MD, MPH, vice chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases. “The goal is to get children back into schools for in-person learning, but in many communities, this is not possible as the virus spreads unchecked.”

The smallest increase over the last week, just 0.9%, came in Rhode Island, with Massachusetts just a bit higher at 1.0%. Also at the low end of the increase scale are Arizona (3.3%) and Louisiana (4.0%), two states that have very high rates of cumulative cases: 1,380 per 100,000 children for Arizona and 1,234 per 100,000 for Louisiana, the report said.

To give those figures some context, Tennessee has the highest cumulative count of any state at 1,553 cases per 100,000 children and Vermont has the lowest at 151, based on the data gathered by the AAP and CHA.

“While much remains unknown about COVID-19, we do know that the spread among children reflects what is happening in the broader communities. A disproportionate number of cases are reported in Black and Hispanic children and in places where there is high poverty. We must work harder to address societal inequities that contribute to these disparities,” Dr. Goza said.

according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

States have reported 513,415 cases of COVID-19 in children since the beginning of the pandemic, with almost 37,000 coming in the last week, the AAP and the CHA said Sept. 8 in the weekly report. That figure includes New York City – the rest of New York State is not reporting ages for COVID-19 patients – as well as Puerto Rico, the District of Columbia, and Guam.

“These numbers are a chilling reminder of why we need to take this virus seriously,” AAP President Sara Goza, MD, said in a written statement.

Children now represent 9.8% of the almost 5.3 million cases that have been reported in Americans of all ages. The proportion of child cases has continued to increase as the pandemic has progressed – it was 8.0% as of mid-July and 5.2% in early June, the data show.

“Throughout the summer, surges in the virus have occurred in Southern, Western, and Midwestern states,” the AAP statement said.

The latest AAP/CHA report shows that, from Aug. 27 to Sept. 3, the total number of child cases jumped by 33.7% in South Dakota, more than any other state. North Dakota was next at 22.7%, followed by Hawaii (18.1%), Missouri (16.8%), and Kentucky (16.4%).

“This rapid rise in positive cases occurred over the summer, and as the weather cools, we know people will spend more time indoors,” said Sean O’Leary, MD, MPH, vice chair of the AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases. “The goal is to get children back into schools for in-person learning, but in many communities, this is not possible as the virus spreads unchecked.”

The smallest increase over the last week, just 0.9%, came in Rhode Island, with Massachusetts just a bit higher at 1.0%. Also at the low end of the increase scale are Arizona (3.3%) and Louisiana (4.0%), two states that have very high rates of cumulative cases: 1,380 per 100,000 children for Arizona and 1,234 per 100,000 for Louisiana, the report said.

To give those figures some context, Tennessee has the highest cumulative count of any state at 1,553 cases per 100,000 children and Vermont has the lowest at 151, based on the data gathered by the AAP and CHA.

“While much remains unknown about COVID-19, we do know that the spread among children reflects what is happening in the broader communities. A disproportionate number of cases are reported in Black and Hispanic children and in places where there is high poverty. We must work harder to address societal inequities that contribute to these disparities,” Dr. Goza said.

We are all in this together: Lessons learned on a COVID-19 unit

Like most family medicine residencies, our teaching nursing home was struck with a COVID-19 outbreak. Within 10 days, I was the sole physician responsible for 15 patients with varying degrees of illness, quarantined behind the fire doors of a wing of a Memory Support Unit. My daily work there over the course of the next month prompted me to reflect on some of the core principles of family medicine, and health care, that are vital to effective patient care during a pandemic. My experience provided the following reminders:

Work as a team. Gowned, gloved, and masked behind the fire doors, our world shrank to our patients and a 4-person team comprised of a nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and me. For the first time in the 10+ years I’ve worked at that facility, I actually asked for and memorized the names of everyone I was working with that day. Without an intercom or other telecommunications system, it became important for me to be able to call for my team members by name for immediate help. We had to depend on one another to make sure all patients were hydrated and fed, to avert falls whenever possible, to intervene early when dementia-associated behaviors were escalating, and to recognize when patients were crashing.

We also had to depend on each other to ensure that our personal protective equipment remained properly placed, to combat the psychological sense of isolation that quarantine environments engender, and to placate a gnawing undercurrent of unease while working around a potentially deadly pathogen.

Develop clinical routines. Having listened to other medical directors whose nursing homes were affected by the pandemic earlier than we were, and hearing about potentially avoidable complications, we developed clinical routines. This began with identifying any patients with diabetes whose poor appetites while acutely ill could send them into hypoglycemia. We devised a daily clinical report sheet that included vital signs, date of positive COVID-19 test, global clinical status, and advance directives. Unlike the usual mode of working almost in parallel, I began my workday with a “sign-out” from the nurse, then started examining each patient.

Under the strain of this unusual environment and novel circumstances, we communicated more and more often. This allowed us to quickly recognize and communicate emerging changes in the clinical status of a patient by sharing our observations of subtle, nonspecific “sub-threshold” indicators.

Clarify the goals of care. Since most of the patients in the COVID-19 unit were under the long-term care of other attending physicians, it was important for me to understand the wishes of the patient or surrogate decision maker, should life-threatening complications occur. While all affected patients were long-term residents of a memory support unit, some had full-code advance directives. I quickly realized that what was first necessary was to develop rapport and trust with the families who didn’t know me, then discuss goals of care, and finally assure that the advance directives were in congruence with their stated goals. What helped families gain trust in me was knowing that I was seeing their loved one daily, that I was committed to helping the patient survive this infection, and that I was willing to come back to the facility if a crisis occurred—even at night, if necessary.

Appreciate the daily work of team members. One of my greatest worries was dehydration. When elders were acutely ill and eating and drinking poorly, I would assist with feeding and offering liquids. I quickly came to appreciate how complex and subtle this seemingly mundane task can be. Learning the proper pace and portion size, even choosing the right conversation topic and tone, could make the difference between a patient “shutting down” and refusing all nourishment and successfully drinking a 360-cc cup of a high-nutrient shake.

Continue to: In the disrupted routines...

In the disrupted routines and altered physical environments of the COVID-19 unit, the psychological and behavioral complications of dementia intensified for some patients. I observed first-hand the great patience, kindness, and finesse that nurses and nursing assistants display in their efforts to de-escalate and prevent disruptive behaviors.

Empathize with (and appreciate) families. Families tearfully reminded me that they had been suffering from the absence of contact with their loved ones for months; COVID-19 added to that trauma for many of them. They talked about the missed graduations, birthdays, and other precious times together that were lost because of the quarantine.

Families also prevented me from making mistakes. When I ordered nitrofurantoin for a patient with a urinary tract infection, her son called me and respectfully requested I “just check and make sure” it would not cause a problem, given her G6PD deficiency. He prevented me from prescribing an antibiotic contraindicated in that condition.

Bring forward the lessons learned. The COVID-19 outbreak has passed through our nursing home—at least for now. I perceive a subtle shift in how we continue to interact with one another. Behind the masks, we make a little more eye contact; we more often address each other by name; and we acknowledge a greater mutual respect.

The shared experience of COVID-19 has brought us all a little closer together, and in the end, our patients have benefitted.

Like most family medicine residencies, our teaching nursing home was struck with a COVID-19 outbreak. Within 10 days, I was the sole physician responsible for 15 patients with varying degrees of illness, quarantined behind the fire doors of a wing of a Memory Support Unit. My daily work there over the course of the next month prompted me to reflect on some of the core principles of family medicine, and health care, that are vital to effective patient care during a pandemic. My experience provided the following reminders:

Work as a team. Gowned, gloved, and masked behind the fire doors, our world shrank to our patients and a 4-person team comprised of a nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and me. For the first time in the 10+ years I’ve worked at that facility, I actually asked for and memorized the names of everyone I was working with that day. Without an intercom or other telecommunications system, it became important for me to be able to call for my team members by name for immediate help. We had to depend on one another to make sure all patients were hydrated and fed, to avert falls whenever possible, to intervene early when dementia-associated behaviors were escalating, and to recognize when patients were crashing.

We also had to depend on each other to ensure that our personal protective equipment remained properly placed, to combat the psychological sense of isolation that quarantine environments engender, and to placate a gnawing undercurrent of unease while working around a potentially deadly pathogen.

Develop clinical routines. Having listened to other medical directors whose nursing homes were affected by the pandemic earlier than we were, and hearing about potentially avoidable complications, we developed clinical routines. This began with identifying any patients with diabetes whose poor appetites while acutely ill could send them into hypoglycemia. We devised a daily clinical report sheet that included vital signs, date of positive COVID-19 test, global clinical status, and advance directives. Unlike the usual mode of working almost in parallel, I began my workday with a “sign-out” from the nurse, then started examining each patient.

Under the strain of this unusual environment and novel circumstances, we communicated more and more often. This allowed us to quickly recognize and communicate emerging changes in the clinical status of a patient by sharing our observations of subtle, nonspecific “sub-threshold” indicators.

Clarify the goals of care. Since most of the patients in the COVID-19 unit were under the long-term care of other attending physicians, it was important for me to understand the wishes of the patient or surrogate decision maker, should life-threatening complications occur. While all affected patients were long-term residents of a memory support unit, some had full-code advance directives. I quickly realized that what was first necessary was to develop rapport and trust with the families who didn’t know me, then discuss goals of care, and finally assure that the advance directives were in congruence with their stated goals. What helped families gain trust in me was knowing that I was seeing their loved one daily, that I was committed to helping the patient survive this infection, and that I was willing to come back to the facility if a crisis occurred—even at night, if necessary.

Appreciate the daily work of team members. One of my greatest worries was dehydration. When elders were acutely ill and eating and drinking poorly, I would assist with feeding and offering liquids. I quickly came to appreciate how complex and subtle this seemingly mundane task can be. Learning the proper pace and portion size, even choosing the right conversation topic and tone, could make the difference between a patient “shutting down” and refusing all nourishment and successfully drinking a 360-cc cup of a high-nutrient shake.

Continue to: In the disrupted routines...

In the disrupted routines and altered physical environments of the COVID-19 unit, the psychological and behavioral complications of dementia intensified for some patients. I observed first-hand the great patience, kindness, and finesse that nurses and nursing assistants display in their efforts to de-escalate and prevent disruptive behaviors.

Empathize with (and appreciate) families. Families tearfully reminded me that they had been suffering from the absence of contact with their loved ones for months; COVID-19 added to that trauma for many of them. They talked about the missed graduations, birthdays, and other precious times together that were lost because of the quarantine.

Families also prevented me from making mistakes. When I ordered nitrofurantoin for a patient with a urinary tract infection, her son called me and respectfully requested I “just check and make sure” it would not cause a problem, given her G6PD deficiency. He prevented me from prescribing an antibiotic contraindicated in that condition.

Bring forward the lessons learned. The COVID-19 outbreak has passed through our nursing home—at least for now. I perceive a subtle shift in how we continue to interact with one another. Behind the masks, we make a little more eye contact; we more often address each other by name; and we acknowledge a greater mutual respect.

The shared experience of COVID-19 has brought us all a little closer together, and in the end, our patients have benefitted.

Like most family medicine residencies, our teaching nursing home was struck with a COVID-19 outbreak. Within 10 days, I was the sole physician responsible for 15 patients with varying degrees of illness, quarantined behind the fire doors of a wing of a Memory Support Unit. My daily work there over the course of the next month prompted me to reflect on some of the core principles of family medicine, and health care, that are vital to effective patient care during a pandemic. My experience provided the following reminders:

Work as a team. Gowned, gloved, and masked behind the fire doors, our world shrank to our patients and a 4-person team comprised of a nurse, 2 nursing assistants, and me. For the first time in the 10+ years I’ve worked at that facility, I actually asked for and memorized the names of everyone I was working with that day. Without an intercom or other telecommunications system, it became important for me to be able to call for my team members by name for immediate help. We had to depend on one another to make sure all patients were hydrated and fed, to avert falls whenever possible, to intervene early when dementia-associated behaviors were escalating, and to recognize when patients were crashing.

We also had to depend on each other to ensure that our personal protective equipment remained properly placed, to combat the psychological sense of isolation that quarantine environments engender, and to placate a gnawing undercurrent of unease while working around a potentially deadly pathogen.

Develop clinical routines. Having listened to other medical directors whose nursing homes were affected by the pandemic earlier than we were, and hearing about potentially avoidable complications, we developed clinical routines. This began with identifying any patients with diabetes whose poor appetites while acutely ill could send them into hypoglycemia. We devised a daily clinical report sheet that included vital signs, date of positive COVID-19 test, global clinical status, and advance directives. Unlike the usual mode of working almost in parallel, I began my workday with a “sign-out” from the nurse, then started examining each patient.

Under the strain of this unusual environment and novel circumstances, we communicated more and more often. This allowed us to quickly recognize and communicate emerging changes in the clinical status of a patient by sharing our observations of subtle, nonspecific “sub-threshold” indicators.

Clarify the goals of care. Since most of the patients in the COVID-19 unit were under the long-term care of other attending physicians, it was important for me to understand the wishes of the patient or surrogate decision maker, should life-threatening complications occur. While all affected patients were long-term residents of a memory support unit, some had full-code advance directives. I quickly realized that what was first necessary was to develop rapport and trust with the families who didn’t know me, then discuss goals of care, and finally assure that the advance directives were in congruence with their stated goals. What helped families gain trust in me was knowing that I was seeing their loved one daily, that I was committed to helping the patient survive this infection, and that I was willing to come back to the facility if a crisis occurred—even at night, if necessary.

Appreciate the daily work of team members. One of my greatest worries was dehydration. When elders were acutely ill and eating and drinking poorly, I would assist with feeding and offering liquids. I quickly came to appreciate how complex and subtle this seemingly mundane task can be. Learning the proper pace and portion size, even choosing the right conversation topic and tone, could make the difference between a patient “shutting down” and refusing all nourishment and successfully drinking a 360-cc cup of a high-nutrient shake.

Continue to: In the disrupted routines...

In the disrupted routines and altered physical environments of the COVID-19 unit, the psychological and behavioral complications of dementia intensified for some patients. I observed first-hand the great patience, kindness, and finesse that nurses and nursing assistants display in their efforts to de-escalate and prevent disruptive behaviors.

Empathize with (and appreciate) families. Families tearfully reminded me that they had been suffering from the absence of contact with their loved ones for months; COVID-19 added to that trauma for many of them. They talked about the missed graduations, birthdays, and other precious times together that were lost because of the quarantine.

Families also prevented me from making mistakes. When I ordered nitrofurantoin for a patient with a urinary tract infection, her son called me and respectfully requested I “just check and make sure” it would not cause a problem, given her G6PD deficiency. He prevented me from prescribing an antibiotic contraindicated in that condition.

Bring forward the lessons learned. The COVID-19 outbreak has passed through our nursing home—at least for now. I perceive a subtle shift in how we continue to interact with one another. Behind the masks, we make a little more eye contact; we more often address each other by name; and we acknowledge a greater mutual respect.

The shared experience of COVID-19 has brought us all a little closer together, and in the end, our patients have benefitted.

45-year-old man • fever • generalized rash • recent history of calcaneal osteomyelitis • Dx?

THE CASE

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a fever and generalized rash. For the previous 2 weeks, he had been treated at a skilled nursing facility with IV vancomycin and cefepime for left calcaneal osteomyelitis. He reported that the rash was pruritic and started 2 days prior to hospital admission.

His past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and polysubstance drug abuse. Medical and travel history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was taking the following medications at the time of presentation: hydrocodone-acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and metformin.

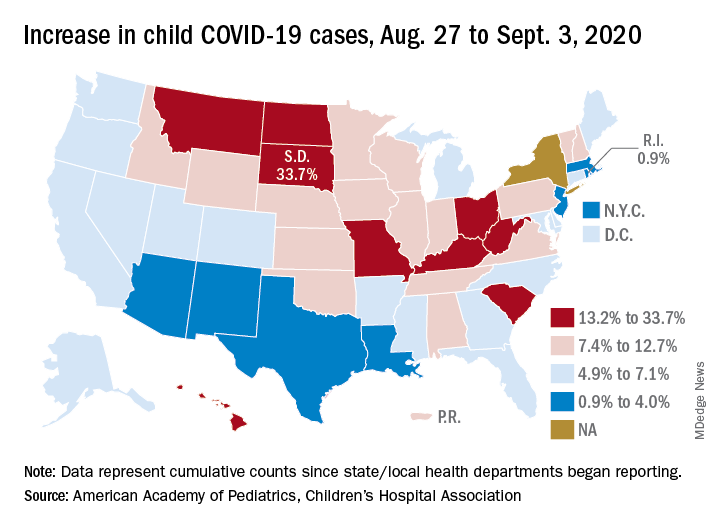

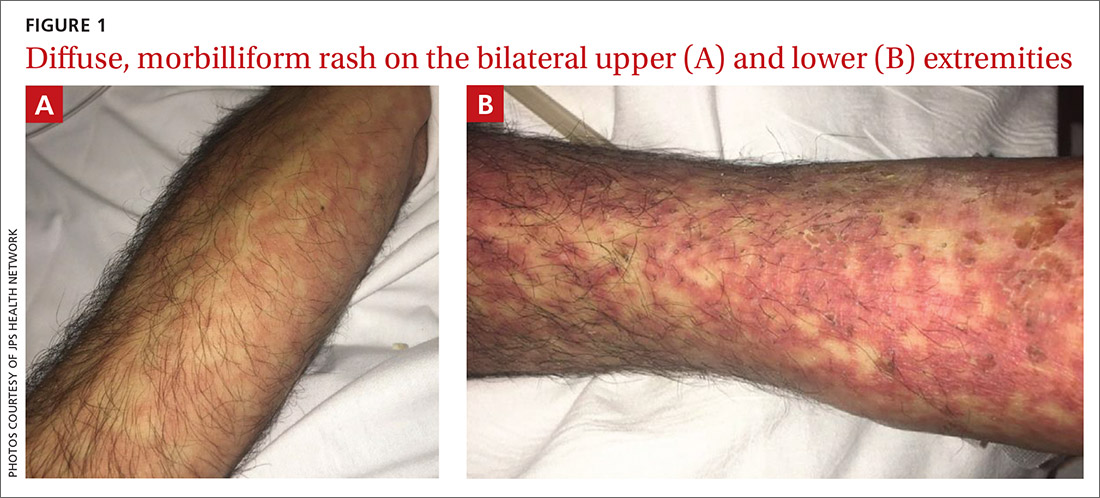

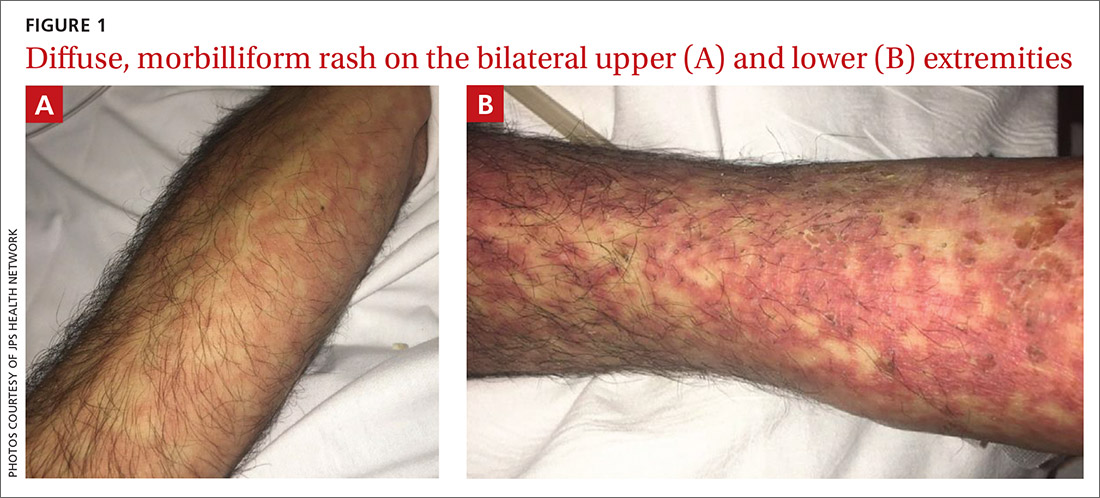

Initial vital signs included a temperature of 102.9°F; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; heart rate, 97 beats/min; and blood pressure, 89/50 mm Hg. Physical exam was notable for left anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient had no facial edema, but he did have a diffuse, morbilliform rash on his bilateral upper and lower extremities, encompassing about 54% of his body surface area (FIGURE 1).

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4.7/mcL, with 3.4% eosinophils and 10.9% monocytes; an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h; and a C-reactive protein level of 1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were both elevated (AST: 95 U/L [normal range, 8 - 48 U/L]; ALT: 115 U/L [normal range: 7 - 55 U/L]). A chest x-ray was obtained and showed new lung infiltrates (FIGURE 2).

Linezolid and meropenem were initiated for a presumed health care–associated pneumonia, and a sepsis work-up was initiated.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s rash and pruritus worsened after meropenem was introduced. A hepatitis panel was nonreactive except for prior hepatitis A exposure. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was normal. Investigation of pneumonia pathogens including Legionella, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia psittaci did not reveal any causative agents. A skin biopsy revealed perivascular neutrophilic dermatitis with dyskeratosis.

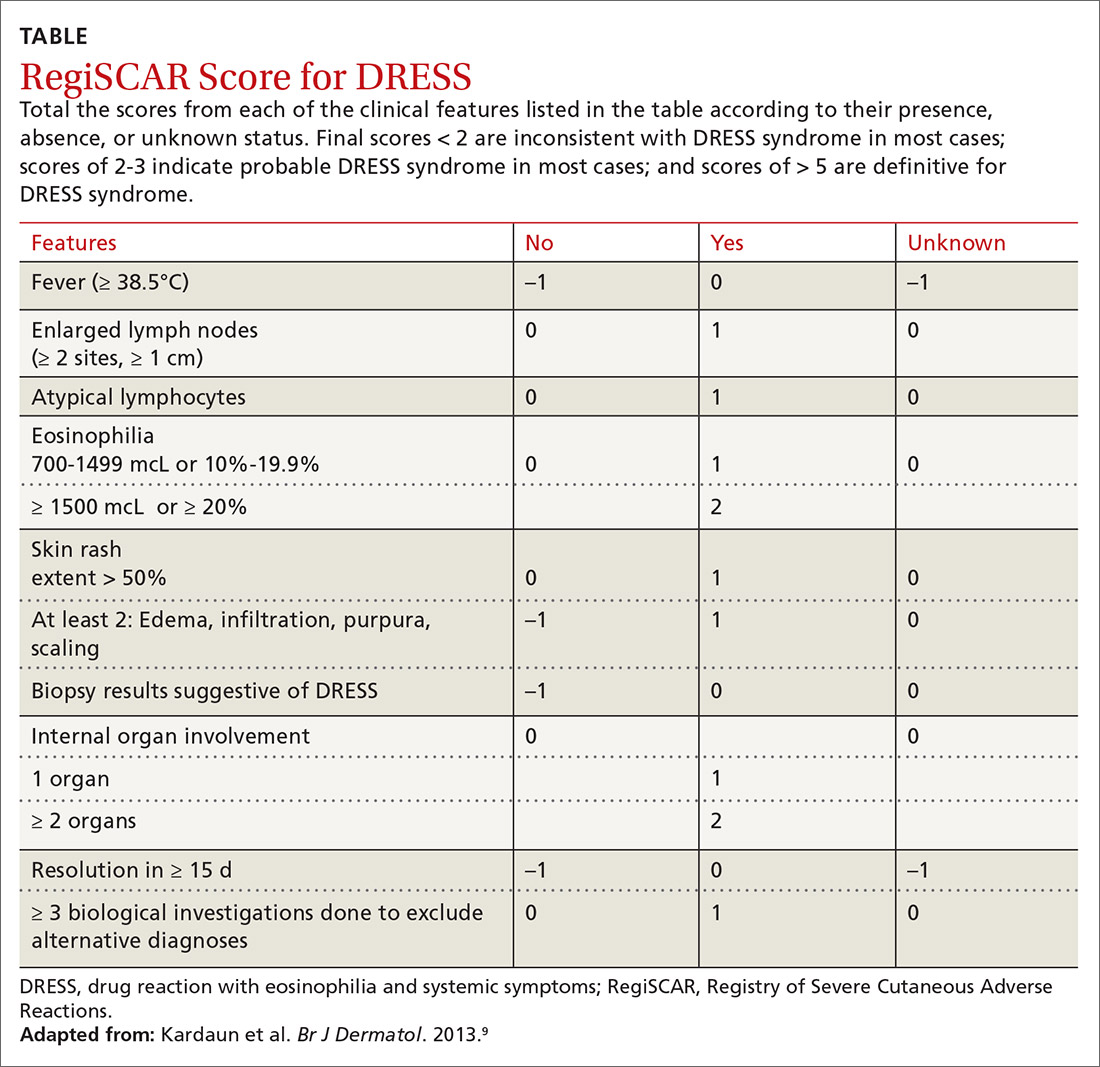

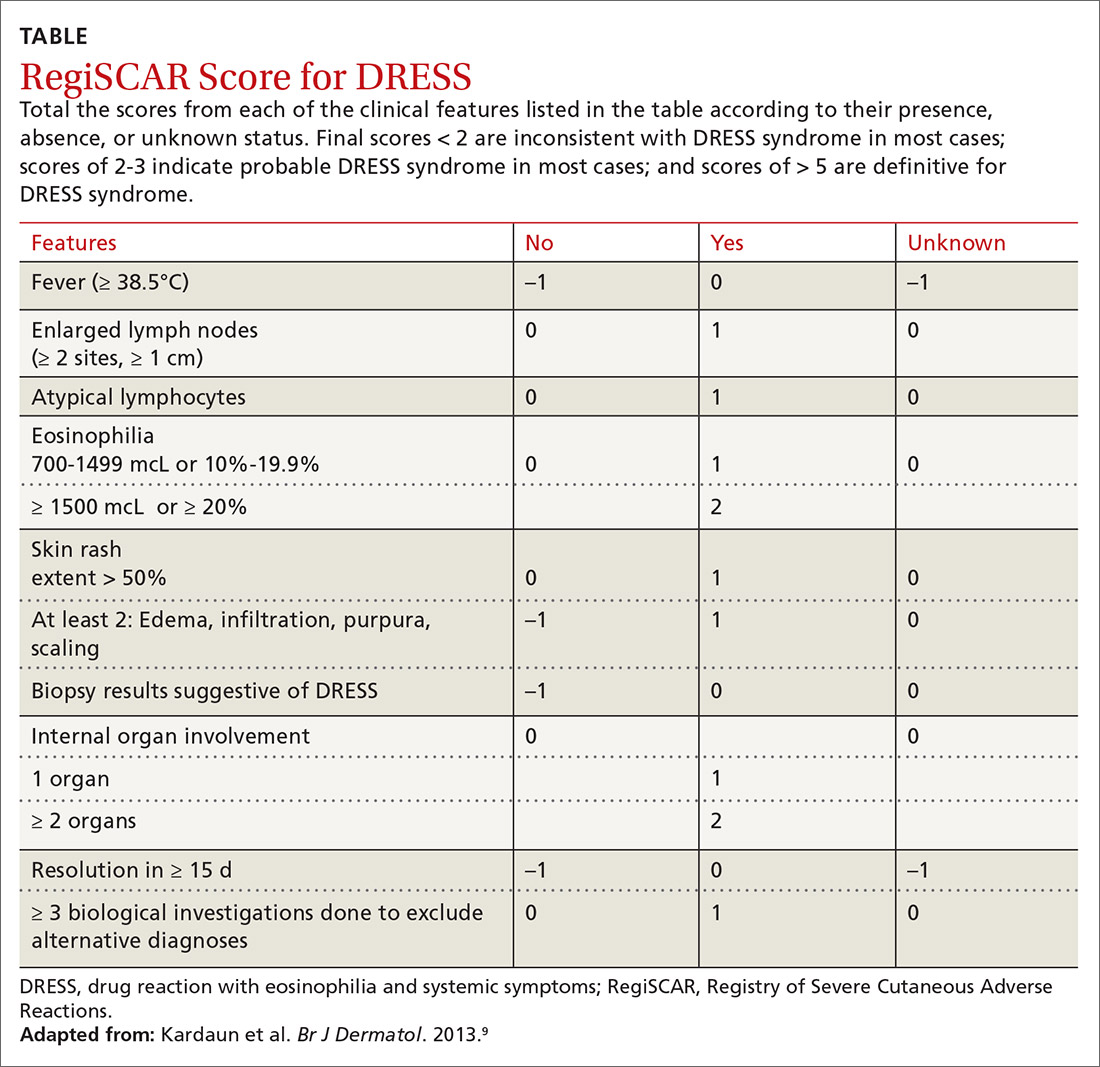

The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome based on his fever, worsening morbilliform rash, lymphadenopathy, and elevated liver transaminase levels. Although he did not have marked eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes were present. Serologies for human herpesvirus (HHV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all unremarkable.

Continue to: During discussions...

During discussions with an infectious disease specialist, it was concluded that the patient’s DRESS syndrome was likely secondary to beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient had been receiving cefepime prior to hospitalization. Meropenem was discontinued and aztreonam was started, with continued linezolid. This patient did not have a reactivation of a herpesvirus (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, or CMV), which has been previously reported in cases of DRESS syndrome.

DISCUSSION

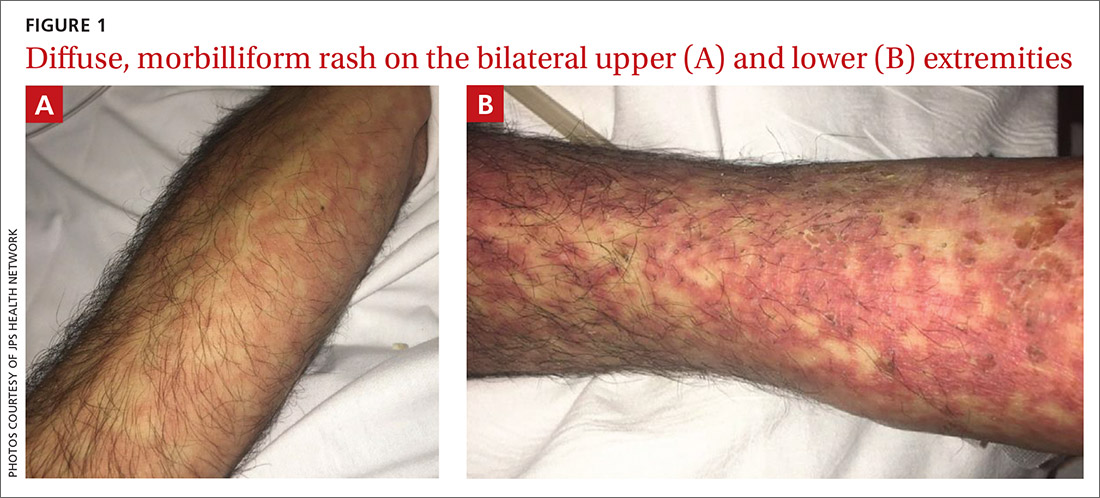

DRESS syndrome is a challenging diagnosis to make due to the multiplicity of presenting symptoms. Skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatic involvement, and hypereosinophilia are characteristic findings.1 Accurate diagnosis reduces fatal disease outcomes, which are estimated to occur in 5%-10% of cases.1,2

Causative agents. DRESS syndrome typically occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the introduction of the causative agent, commonly an aromatic anticonvulsant or antibiotic.3 The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using carbamazepine and phenytoin is estimated to be 1 to 5 per 10,000 patients. The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using antibiotics is unknown. Frequently, the inducing antibiotic is a beta-lactam, as in this case.4,5

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood, although there appears to be an immune-mediated reaction that occurs in certain patients after viral reactivation, particularly with herpesviruses. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the culprit drug is able to induce viral reactivation leading to T-lymphocyte response and systemic inflammation, which occurs in multiple organs.6,7 Reported long-term sequelae of DRESS syndrome include immune-mediated diseases such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. In addition, it is hypothesized that there is a genetic predisposition involving human leukocyte antigens that increases the likelihood that individuals will develop DRESS syndrome.5,8

Diagnosis. The

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is aimed at stopping the causative agent and starting moderate- to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/d). If symptoms continue to progress, cyclosporine can be used. N-acetylcysteine may also be beneficial due to its ability to neutralize drug metabolites that can stimulate T-cell response.7 There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that antiviral medication should be initiated.1,7

Our patient was treated with 2 mg/kg/d of prednisone, along with triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and N-acetylcysteine. His rash improved dramatically during his hospital stay and at the subsequent 1-month follow-up was completely resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

DRESS syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and liver involvement after initiation of drugs commonly associated with this syndrome. Our case reinforces previous clinical evidence that beta-lactam antibiotics are a common cause of DRESS syndrome; patients taking these medications should be closely monitored. Cross-reactions are frequent, and it is imperative that patients avoid related drugs to prevent recurrence. Although glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment, further studies are needed to assess the benefits of N-acetylcysteine.

CORRESPONDENCE

W. Jacob Cobb, MD, JPS Health Network, 1500 South Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 76104; [email protected]

1. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

2. Chen Y, Chiu H, Chu C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373-1379.

3. Jeung Y-J, Lee J-Y, Oh M-J, et al. Comparison of the causes and clinical features of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:123–126.

4. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations [commentary]. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:1083-1084.

5. Ben-Said B, Arnaud-Butel S, Rozières A, et al. Allergic delayed drug hypersensitivity is more frequently diagnosed in drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome than in exanthema induced by beta lactam antibiotics. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80:71-74.

6. Schrijvers R, Gilissen L, Chiriac AM, et al. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of delayed-type drug hypersensitivity reactions, from bedside to bench and back. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:31.

7. Moling O, Tappeiner L, Piccin A, et al. Treatment of DIHS/DRESS syndrome with combined N-acetylcysteine, prednisone and valganciclovir—a hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CS57-CS62.

8. Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113898.

9. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

10. Bernard L, Eichenfield L. Drug-associated rashes. In: Zaoutis L, Chiang V, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010: 1005-1011.

11. Grover S. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:3-6.

THE CASE

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a fever and generalized rash. For the previous 2 weeks, he had been treated at a skilled nursing facility with IV vancomycin and cefepime for left calcaneal osteomyelitis. He reported that the rash was pruritic and started 2 days prior to hospital admission.

His past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and polysubstance drug abuse. Medical and travel history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was taking the following medications at the time of presentation: hydrocodone-acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and metformin.

Initial vital signs included a temperature of 102.9°F; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; heart rate, 97 beats/min; and blood pressure, 89/50 mm Hg. Physical exam was notable for left anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient had no facial edema, but he did have a diffuse, morbilliform rash on his bilateral upper and lower extremities, encompassing about 54% of his body surface area (FIGURE 1).

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4.7/mcL, with 3.4% eosinophils and 10.9% monocytes; an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h; and a C-reactive protein level of 1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were both elevated (AST: 95 U/L [normal range, 8 - 48 U/L]; ALT: 115 U/L [normal range: 7 - 55 U/L]). A chest x-ray was obtained and showed new lung infiltrates (FIGURE 2).

Linezolid and meropenem were initiated for a presumed health care–associated pneumonia, and a sepsis work-up was initiated.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s rash and pruritus worsened after meropenem was introduced. A hepatitis panel was nonreactive except for prior hepatitis A exposure. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was normal. Investigation of pneumonia pathogens including Legionella, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia psittaci did not reveal any causative agents. A skin biopsy revealed perivascular neutrophilic dermatitis with dyskeratosis.

The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome based on his fever, worsening morbilliform rash, lymphadenopathy, and elevated liver transaminase levels. Although he did not have marked eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes were present. Serologies for human herpesvirus (HHV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all unremarkable.

Continue to: During discussions...

During discussions with an infectious disease specialist, it was concluded that the patient’s DRESS syndrome was likely secondary to beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient had been receiving cefepime prior to hospitalization. Meropenem was discontinued and aztreonam was started, with continued linezolid. This patient did not have a reactivation of a herpesvirus (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, or CMV), which has been previously reported in cases of DRESS syndrome.

DISCUSSION

DRESS syndrome is a challenging diagnosis to make due to the multiplicity of presenting symptoms. Skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatic involvement, and hypereosinophilia are characteristic findings.1 Accurate diagnosis reduces fatal disease outcomes, which are estimated to occur in 5%-10% of cases.1,2

Causative agents. DRESS syndrome typically occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the introduction of the causative agent, commonly an aromatic anticonvulsant or antibiotic.3 The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using carbamazepine and phenytoin is estimated to be 1 to 5 per 10,000 patients. The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using antibiotics is unknown. Frequently, the inducing antibiotic is a beta-lactam, as in this case.4,5

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood, although there appears to be an immune-mediated reaction that occurs in certain patients after viral reactivation, particularly with herpesviruses. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the culprit drug is able to induce viral reactivation leading to T-lymphocyte response and systemic inflammation, which occurs in multiple organs.6,7 Reported long-term sequelae of DRESS syndrome include immune-mediated diseases such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. In addition, it is hypothesized that there is a genetic predisposition involving human leukocyte antigens that increases the likelihood that individuals will develop DRESS syndrome.5,8

Diagnosis. The

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is aimed at stopping the causative agent and starting moderate- to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/d). If symptoms continue to progress, cyclosporine can be used. N-acetylcysteine may also be beneficial due to its ability to neutralize drug metabolites that can stimulate T-cell response.7 There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that antiviral medication should be initiated.1,7

Our patient was treated with 2 mg/kg/d of prednisone, along with triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and N-acetylcysteine. His rash improved dramatically during his hospital stay and at the subsequent 1-month follow-up was completely resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

DRESS syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and liver involvement after initiation of drugs commonly associated with this syndrome. Our case reinforces previous clinical evidence that beta-lactam antibiotics are a common cause of DRESS syndrome; patients taking these medications should be closely monitored. Cross-reactions are frequent, and it is imperative that patients avoid related drugs to prevent recurrence. Although glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment, further studies are needed to assess the benefits of N-acetylcysteine.

CORRESPONDENCE

W. Jacob Cobb, MD, JPS Health Network, 1500 South Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 76104; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 45-year-old man was admitted to the hospital with a fever and generalized rash. For the previous 2 weeks, he had been treated at a skilled nursing facility with IV vancomycin and cefepime for left calcaneal osteomyelitis. He reported that the rash was pruritic and started 2 days prior to hospital admission.

His past medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus and polysubstance drug abuse. Medical and travel history were otherwise unremarkable. The patient was taking the following medications at the time of presentation: hydrocodone-acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, melatonin, and metformin.

Initial vital signs included a temperature of 102.9°F; respiratory rate, 22 breaths/min; heart rate, 97 beats/min; and blood pressure, 89/50 mm Hg. Physical exam was notable for left anterior cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy. The patient had no facial edema, but he did have a diffuse, morbilliform rash on his bilateral upper and lower extremities, encompassing about 54% of his body surface area (FIGURE 1).

Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 4.7/mcL, with 3.4% eosinophils and 10.9% monocytes; an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 60 mm/h; and a C-reactive protein level of 1 mg/dL. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were both elevated (AST: 95 U/L [normal range, 8 - 48 U/L]; ALT: 115 U/L [normal range: 7 - 55 U/L]). A chest x-ray was obtained and showed new lung infiltrates (FIGURE 2).

Linezolid and meropenem were initiated for a presumed health care–associated pneumonia, and a sepsis work-up was initiated.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient’s rash and pruritus worsened after meropenem was introduced. A hepatitis panel was nonreactive except for prior hepatitis A exposure. Ultrasound of the liver and spleen was normal. Investigation of pneumonia pathogens including Legionella, Streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydia psittaci did not reveal any causative agents. A skin biopsy revealed perivascular neutrophilic dermatitis with dyskeratosis.

The patient was diagnosed with DRESS (drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms) syndrome based on his fever, worsening morbilliform rash, lymphadenopathy, and elevated liver transaminase levels. Although he did not have marked eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytes were present. Serologies for human herpesvirus (HHV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and cytomegalovirus (CMV) were all unremarkable.

Continue to: During discussions...

During discussions with an infectious disease specialist, it was concluded that the patient’s DRESS syndrome was likely secondary to beta-lactam antibiotics. The patient had been receiving cefepime prior to hospitalization. Meropenem was discontinued and aztreonam was started, with continued linezolid. This patient did not have a reactivation of a herpesvirus (HHV-6, HHV-7, EBV, or CMV), which has been previously reported in cases of DRESS syndrome.

DISCUSSION

DRESS syndrome is a challenging diagnosis to make due to the multiplicity of presenting symptoms. Skin rash, lymphadenopathy, hepatic involvement, and hypereosinophilia are characteristic findings.1 Accurate diagnosis reduces fatal disease outcomes, which are estimated to occur in 5%-10% of cases.1,2

Causative agents. DRESS syndrome typically occurs 2 to 6 weeks after the introduction of the causative agent, commonly an aromatic anticonvulsant or antibiotic.3 The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using carbamazepine and phenytoin is estimated to be 1 to 5 per 10,000 patients. The incidence of DRESS syndrome in patients using antibiotics is unknown. Frequently, the inducing antibiotic is a beta-lactam, as in this case.4,5

The pathogenesis of DRESS syndrome is not well understood, although there appears to be an immune-mediated reaction that occurs in certain patients after viral reactivation, particularly with herpesviruses. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the culprit drug is able to induce viral reactivation leading to T-lymphocyte response and systemic inflammation, which occurs in multiple organs.6,7 Reported long-term sequelae of DRESS syndrome include immune-mediated diseases such as thyroiditis and type 1 diabetes. In addition, it is hypothesized that there is a genetic predisposition involving human leukocyte antigens that increases the likelihood that individuals will develop DRESS syndrome.5,8

Diagnosis. The

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment is aimed at stopping the causative agent and starting moderate- to high-dose systemic corticosteroids (from 0.5 to 2 mg/kg/d). If symptoms continue to progress, cyclosporine can be used. N-acetylcysteine may also be beneficial due to its ability to neutralize drug metabolites that can stimulate T-cell response.7 There has not been sufficient evidence to suggest that antiviral medication should be initiated.1,7

Our patient was treated with 2 mg/kg/d of prednisone, along with triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and N-acetylcysteine. His rash improved dramatically during his hospital stay and at the subsequent 1-month follow-up was completely resolved.

THE TAKEAWAY

DRESS syndrome should be suspected in patients presenting with fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, pulmonary infiltrates, and liver involvement after initiation of drugs commonly associated with this syndrome. Our case reinforces previous clinical evidence that beta-lactam antibiotics are a common cause of DRESS syndrome; patients taking these medications should be closely monitored. Cross-reactions are frequent, and it is imperative that patients avoid related drugs to prevent recurrence. Although glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment, further studies are needed to assess the benefits of N-acetylcysteine.

CORRESPONDENCE

W. Jacob Cobb, MD, JPS Health Network, 1500 South Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 76104; [email protected]

1. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

2. Chen Y, Chiu H, Chu C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373-1379.

3. Jeung Y-J, Lee J-Y, Oh M-J, et al. Comparison of the causes and clinical features of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:123–126.

4. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations [commentary]. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:1083-1084.

5. Ben-Said B, Arnaud-Butel S, Rozières A, et al. Allergic delayed drug hypersensitivity is more frequently diagnosed in drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome than in exanthema induced by beta lactam antibiotics. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80:71-74.

6. Schrijvers R, Gilissen L, Chiriac AM, et al. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of delayed-type drug hypersensitivity reactions, from bedside to bench and back. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:31.

7. Moling O, Tappeiner L, Piccin A, et al. Treatment of DIHS/DRESS syndrome with combined N-acetylcysteine, prednisone and valganciclovir—a hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CS57-CS62.

8. Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113898.

9. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

10. Bernard L, Eichenfield L. Drug-associated rashes. In: Zaoutis L, Chiang V, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010: 1005-1011.

11. Grover S. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:3-6.

1. Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597.

2. Chen Y, Chiu H, Chu C. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: a retrospective study of 60 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1373-1379.

3. Jeung Y-J, Lee J-Y, Oh M-J, et al. Comparison of the causes and clinical features of drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms and Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2010;2:123–126.

4. Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations [commentary]. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156:1083-1084.

5. Ben-Said B, Arnaud-Butel S, Rozières A, et al. Allergic delayed drug hypersensitivity is more frequently diagnosed in drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome than in exanthema induced by beta lactam antibiotics. J Dermatol Sci. 2015;80:71-74.

6. Schrijvers R, Gilissen L, Chiriac AM, et al. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of delayed-type drug hypersensitivity reactions, from bedside to bench and back. Clin Transl Allergy. 2015;5:31.

7. Moling O, Tappeiner L, Piccin A, et al. Treatment of DIHS/DRESS syndrome with combined N-acetylcysteine, prednisone and valganciclovir—a hypothesis. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:CS57-CS62.

8. Cardoso CS, Vieira AM, Oliveira AP. DRESS syndrome: a case report and literature review. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113898.

9. Kardaun SH, Sekula P, Valeyrie-Allanore L, et al. Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS): an original multisystem adverse drug reaction. Results from the prospective RegiSCAR study. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1071-1080.

10. Bernard L, Eichenfield L. Drug-associated rashes. In: Zaoutis L, Chiang V, eds. Comprehensive Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010: 1005-1011.