User login

Acute kidney injury in children hospitalized with diarrheal illness in the U.S.

Clinical question: To determine the incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury among children hospitalized with diarrheal illness in the United States.

Background: Diarrheal illness is the fourth leading cause of death for children younger than 5 years and the fifth leading cause of years of life lost globally. In the United States, diarrheal illness remains a leading cause of hospital admission among young children. Complications of severe diarrheal illness include hypovolemic acute kidney injury (AKI). Hospitalized children who develop AKI experience longer hospital stays and higher mortality. Additionally, children who experience AKI are at increased risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension, and proteinuria.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) from 2009 and 2012. The authors used secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses of AKI to identify patients.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed all patients with diarrhea and found that the incidence of AKI in children hospitalized was 0.8%. Those with infectious diarrhea had an incidence of 1% and with noninfectious diarrhea had an incidence of 0.6%. There was a higher incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI in patients with infectious diarrhea. The odds of developing AKI increased with older age in both infectious and noninfectious diarrheal illnesses. As compared with noninfectious diarrheal illness, infectious diarrheal illness was associated with higher odds of AKI (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.7-2.7). Irrespective of diarrhea type, hematologic and rheumatologic conditions, solid organ transplant, CKD, and hypertension were associated with higher odds of developing AKI. AKI in infectious diarrheal illness was also associated with other renal or genitourinary abnormalities, whereas AKI in noninfectious diarrheal illness was associated with diabetes, cardiovascular, and neurologic conditions.

Hospitalizations for diarrheal illness complicated by AKI were associated with higher mortality, prolonged LOS, and higher hospital cost with odds of death increased eightfold with AKI, mean hospital stay was prolonged by 3 days, and costs increased by greater than $9,000 per hospital stay. The development of AKI in hospitalized diarrheal illness was associated with an up to 11-fold increase in the odds of in-hospital mortality for infectious (OR, 10.8; 95% CI, 3.4-34.3) and noninfectious diarrheal illness (OR, 7.0; 95% CI, 3.1-15.7).

The strengths of this study include broad representation of hospitals caring for children across the United States. The study was limited by its use of ICD-9 codes which may misidentify AKI. The authors were unable to determine if identifying AKI could improve outcomes for patients with diarrheal illness.

Bottom line: AKI in diarrhea illnesses is relatively rare. Close attention should be given to AKI in patients with certain serious comorbid illnesses.

Article citation: Bradshaw C, Han J, Chertow GM, Long J, Sutherland SM, Anand S. Acute Kidney Injury in Children Hospitalized With Diarrheal Illness in the United States. Hosp Pediatr. 2019 Dec;9(12):933-941.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, and serves as the pediatrics editor for The Hospitalist.

Clinical question: To determine the incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury among children hospitalized with diarrheal illness in the United States.

Background: Diarrheal illness is the fourth leading cause of death for children younger than 5 years and the fifth leading cause of years of life lost globally. In the United States, diarrheal illness remains a leading cause of hospital admission among young children. Complications of severe diarrheal illness include hypovolemic acute kidney injury (AKI). Hospitalized children who develop AKI experience longer hospital stays and higher mortality. Additionally, children who experience AKI are at increased risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension, and proteinuria.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) from 2009 and 2012. The authors used secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses of AKI to identify patients.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed all patients with diarrhea and found that the incidence of AKI in children hospitalized was 0.8%. Those with infectious diarrhea had an incidence of 1% and with noninfectious diarrhea had an incidence of 0.6%. There was a higher incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI in patients with infectious diarrhea. The odds of developing AKI increased with older age in both infectious and noninfectious diarrheal illnesses. As compared with noninfectious diarrheal illness, infectious diarrheal illness was associated with higher odds of AKI (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.7-2.7). Irrespective of diarrhea type, hematologic and rheumatologic conditions, solid organ transplant, CKD, and hypertension were associated with higher odds of developing AKI. AKI in infectious diarrheal illness was also associated with other renal or genitourinary abnormalities, whereas AKI in noninfectious diarrheal illness was associated with diabetes, cardiovascular, and neurologic conditions.

Hospitalizations for diarrheal illness complicated by AKI were associated with higher mortality, prolonged LOS, and higher hospital cost with odds of death increased eightfold with AKI, mean hospital stay was prolonged by 3 days, and costs increased by greater than $9,000 per hospital stay. The development of AKI in hospitalized diarrheal illness was associated with an up to 11-fold increase in the odds of in-hospital mortality for infectious (OR, 10.8; 95% CI, 3.4-34.3) and noninfectious diarrheal illness (OR, 7.0; 95% CI, 3.1-15.7).

The strengths of this study include broad representation of hospitals caring for children across the United States. The study was limited by its use of ICD-9 codes which may misidentify AKI. The authors were unable to determine if identifying AKI could improve outcomes for patients with diarrheal illness.

Bottom line: AKI in diarrhea illnesses is relatively rare. Close attention should be given to AKI in patients with certain serious comorbid illnesses.

Article citation: Bradshaw C, Han J, Chertow GM, Long J, Sutherland SM, Anand S. Acute Kidney Injury in Children Hospitalized With Diarrheal Illness in the United States. Hosp Pediatr. 2019 Dec;9(12):933-941.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, and serves as the pediatrics editor for The Hospitalist.

Clinical question: To determine the incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury among children hospitalized with diarrheal illness in the United States.

Background: Diarrheal illness is the fourth leading cause of death for children younger than 5 years and the fifth leading cause of years of life lost globally. In the United States, diarrheal illness remains a leading cause of hospital admission among young children. Complications of severe diarrheal illness include hypovolemic acute kidney injury (AKI). Hospitalized children who develop AKI experience longer hospital stays and higher mortality. Additionally, children who experience AKI are at increased risk for chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension, and proteinuria.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Kids’ Inpatient Database (KID) from 2009 and 2012. The authors used secondary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnoses of AKI to identify patients.

Synopsis: The authors reviewed all patients with diarrhea and found that the incidence of AKI in children hospitalized was 0.8%. Those with infectious diarrhea had an incidence of 1% and with noninfectious diarrhea had an incidence of 0.6%. There was a higher incidence of dialysis-requiring AKI in patients with infectious diarrhea. The odds of developing AKI increased with older age in both infectious and noninfectious diarrheal illnesses. As compared with noninfectious diarrheal illness, infectious diarrheal illness was associated with higher odds of AKI (odds ratio, 2.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.7-2.7). Irrespective of diarrhea type, hematologic and rheumatologic conditions, solid organ transplant, CKD, and hypertension were associated with higher odds of developing AKI. AKI in infectious diarrheal illness was also associated with other renal or genitourinary abnormalities, whereas AKI in noninfectious diarrheal illness was associated with diabetes, cardiovascular, and neurologic conditions.

Hospitalizations for diarrheal illness complicated by AKI were associated with higher mortality, prolonged LOS, and higher hospital cost with odds of death increased eightfold with AKI, mean hospital stay was prolonged by 3 days, and costs increased by greater than $9,000 per hospital stay. The development of AKI in hospitalized diarrheal illness was associated with an up to 11-fold increase in the odds of in-hospital mortality for infectious (OR, 10.8; 95% CI, 3.4-34.3) and noninfectious diarrheal illness (OR, 7.0; 95% CI, 3.1-15.7).

The strengths of this study include broad representation of hospitals caring for children across the United States. The study was limited by its use of ICD-9 codes which may misidentify AKI. The authors were unable to determine if identifying AKI could improve outcomes for patients with diarrheal illness.

Bottom line: AKI in diarrhea illnesses is relatively rare. Close attention should be given to AKI in patients with certain serious comorbid illnesses.

Article citation: Bradshaw C, Han J, Chertow GM, Long J, Sutherland SM, Anand S. Acute Kidney Injury in Children Hospitalized With Diarrheal Illness in the United States. Hosp Pediatr. 2019 Dec;9(12):933-941.

Dr. Kumar is a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is a clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, and serves as the pediatrics editor for The Hospitalist.

Tender White Lesions on the Groin

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

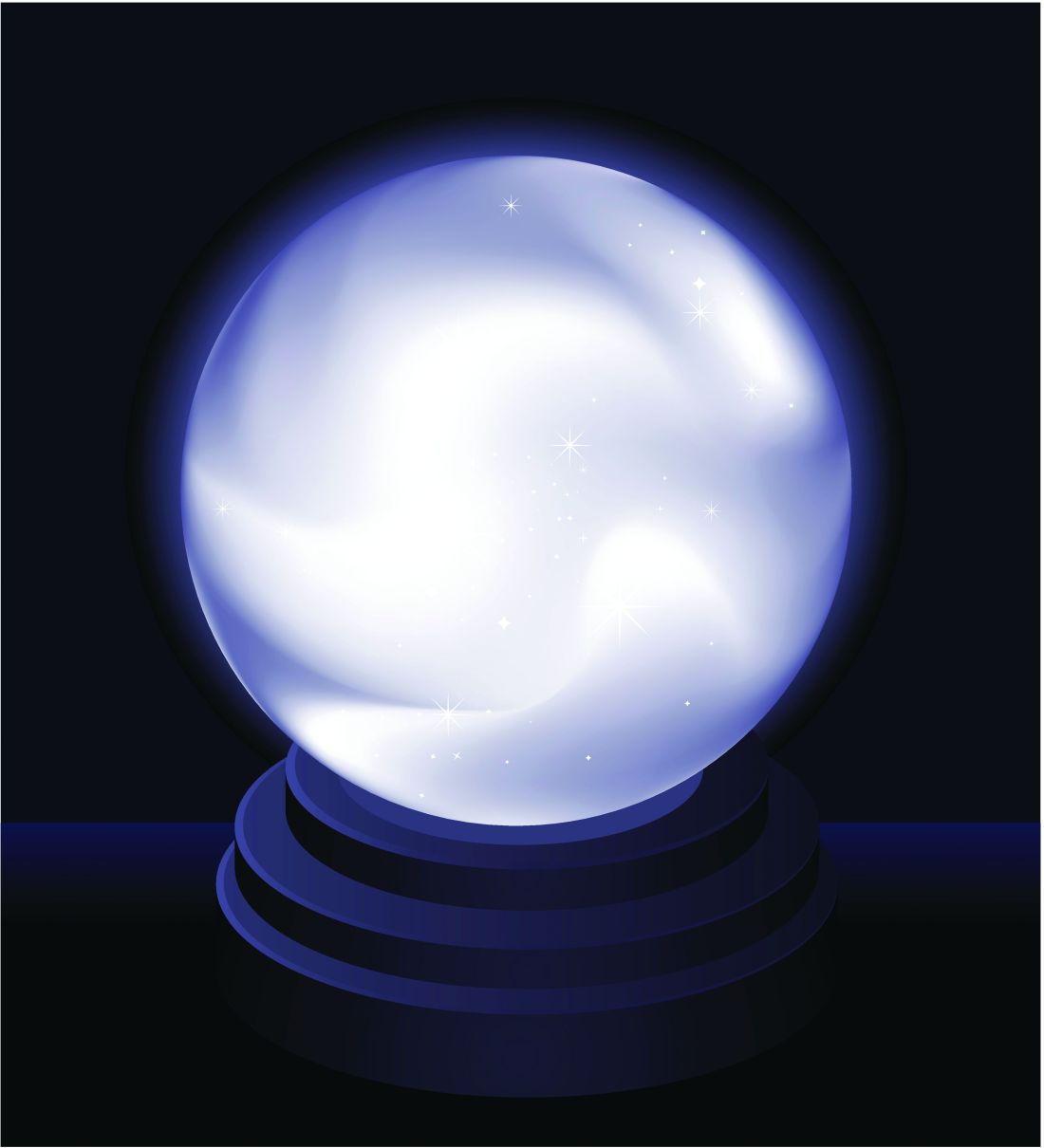

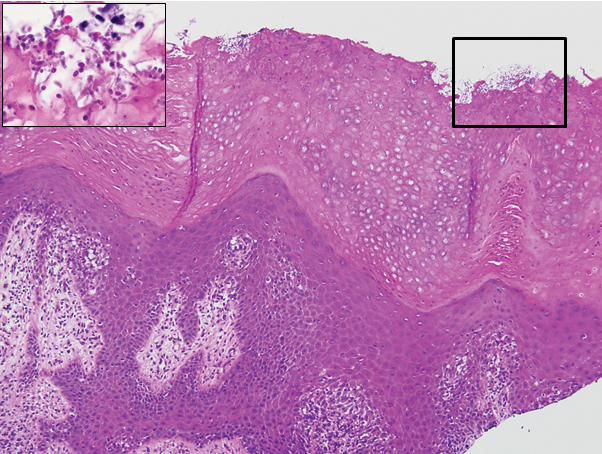

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

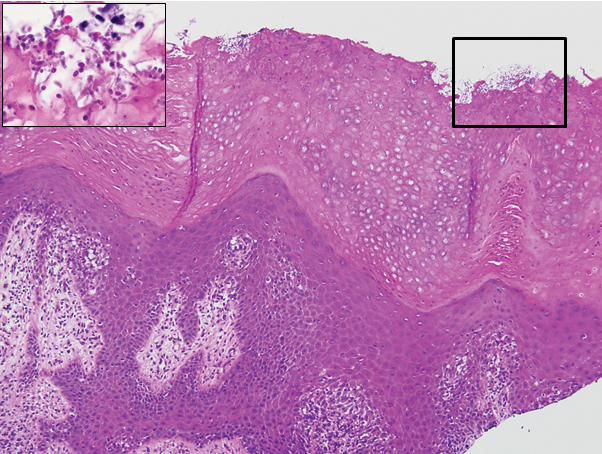

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

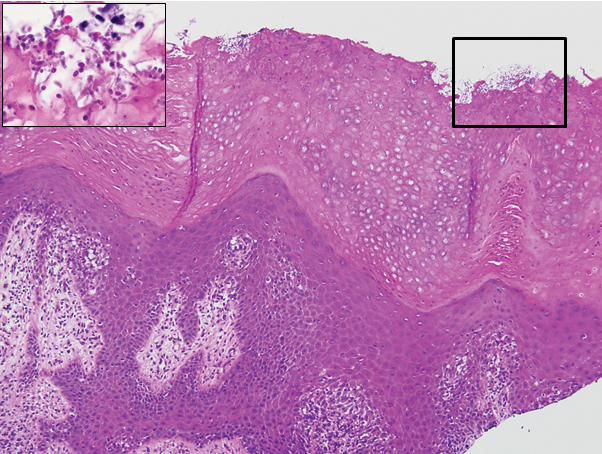

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

The Diagnosis: Candidal Intertrigo

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of severe hyperkeratotic candidal intertrigo with no evidence of Hailey-Hailey disease. Hematoxylin and eosin- stained sections demonstrated irregular acanthosis and variable spongiosis. The stratum corneum was predominantly orthokeratotic with overlying psuedohyphae and yeast fungal elements (Figure 1).

Hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (HIES), also known as hyper-IgE syndrome or Job syndrome, is a rare immunodeficiency disorder characterized by an eczematous dermatitis-like rash, recurrent skin and lung abscesses, eosinophilia, and elevated serum IgE. Facial asymmetry, prominent forehead, deep-set eyes, broad nose, and roughened facial skin with large pores are characteristic of the sporadic and autosomal-recessive forms. Other common findings include retained primary teeth, hyperextensible joints, and recurrent mucocutaneous candidiasis.1

Although autosomal-dominant and autosomal-recessive inheritance patterns exist, sporadic mutations are the most common cause of HIES.2 Several genes have been implicated depending on the inheritance pattern. The majority of autosomal-dominant cases are associated with inactivating STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3) mutations, whereas the majority of autosomal-recessive cases are associated with inactivating DOCK8 (dedicator of cytokinesis 8) mutations.1 Ultimately, all of these mutations lead to an impaired helper T cell (TH17) response, which is crucial for clearing fungal and extracellular bacterial infections.3

Skin eruptions typically are the first manifestation of HIES; they appear within the first week to month of life as papulopustular eruptions on the face and scalp and rapidly generalize to the rest of the body, favoring the shoulders, arms, chest, and buttocks. The pustules then coalesce into crusted plaques that resemble atopic dermatitis, frequently with superimposed Staphylococcus aureus infection. On microscopy, the pustules are folliculocentric and often contain eosinophils, whereas the plaques may contain intraepidermal collections of eosinophils.1

Mucocutaneous candidiasis is seen in approximately 60% of HIES cases and is closely linked to STAT3 inactivating mutations.3 Histologically, there is marked acanthosis with neutrophil exocytosis and abundant yeast and pseudohyphal forms within the stratum corneum (Figure 2).4 Cutaneous candidal infections typically require both oral and topical antifungal agents to clear the infection.3 Most cases of mucocutaneous candidiasis are caused by Candida albicans; however, other known culprits include Candida glabrata, Candida tropicalis, Candida parapsilosis, and Candida krusei.5,6 Of note, species identification and antifungal susceptibility studies may be useful in refractory cases, especially with C glabrata, which is known to acquire resistance to azoles, such as fluconazole, with emerging resistance to echinocandins.6

The differential diagnosis of this groin eruption included Hailey-Hailey disease; pemphigus vegetans, Hallopeau type; tinea cruris; and inverse psoriasis. Hailey-Hailey disease can be complicated by a superimposed candidal infection with similar clinical features, and biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis. Hailey-Hailey disease typically presents with macerated fissured plaques that resemble macerated tissue paper with red fissures (Figure 3). Biopsy confirms full-thickness acantholysis resembling a dilapidated brick wall with minimal dyskeratosis.1 Pemphigus vegetans is a localized variant of pemphigus vulgaris with a predilection for flexural surfaces. The lesions progress to vegetating erosive plaques.4 The Hallopeau type often is studded with pustules and typically remains more localized than the Neumann type. Direct immunofluorescence demonstrates intercellular deposition of IgG and C3, and routine sections characteristically show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal eosinophilic microabscesses.1,4 Tinea cruris is characterized by erythematous annular lesions with raised scaly borders spreading down the inner thighs.7 The epidermis is variably spongiotic with parakeratosis, and neutrophils often present in a layered stratum corneum with basketweave keratin above a layer of more compact and eosinophilic keratin. Fungal stains, such as periodic acid-Schiff, will highlight the fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum. The inguinal folds are a typical location for inverse psoriasis, which generally appears as thin, sharply demarcated, shiny red plaques with less scale than plaque psoriasis.1 Psoriasiform hyperplasia with a diminished granular layer and tortuous papillary dermal vessels would be expected histologically.1

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews' Diseases of the Skin. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

- Schwartz RA, Tarlow MM. Dermatologic manifestations of Job syndrome. Medscape website. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1050852-overview. Updated April 22, 2019. Accessed March 28, 2020.

- Minegishi Y, Saito M. Cutaneous manifestations of hyper IgE syndrome. Allergol Int. 2012;61:191-196.

- Patterson JW. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Executive summary: clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:409-417.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Antifungal resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/antifungal-resistance.html. Updated March 17, 2020. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- Tinea cruris. DermNet NZ website. https://www.dermnetnz.org/topics/tinea-cruris/. Published 2003. Accessed March 28, 2020.

A 28-year-old man with a history of hyperimmunoglobulinemia E syndrome (previously known as Job syndrome), coarse facial features, and multiple skin and soft tissue infections presented to the university dermatology clinic with persistent white, macerated, fissured groin plaques that were present for months. The lesions were tender and pruritic with a burning sensation. Treatment with topical terbinafine and oral fluconazole was attempted without resolution of the eruption. A biopsy of the groin lesion was performed.

Pseudoepitheliomatous Hyperplasia Arising From Purple Tattoo Pigment

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

To the Editor:

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is an uncommon type of reactive epidermal proliferation that can occur from a variety of causes, including an underlying infection, inflammation, neoplastic condition, or trauma induced from tattooing.1 Diagnosis can be challenging and requires clinicopathologic correlation, as PEH can mimic malignancy on histopathology.2-4 Histologically, PEH shows irregular hyperplasia of the epidermis and adnexal epithelium, elongation of the rete ridges, and extension of the reactive proliferation into the dermis. Absence of cytologic atypia is key to the diagnosis of PEH, helping to distinguish it from squamous cell carcinoma and keratoacanthoma. Clinically, patients typically present with well-demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques or nodules in reactive areas, which can be symptomatically pruritic.

A 48-year-old woman presented with scaly and crusted verrucous plaques of 2 months’ duration that were isolated to the areas of purple pigment within a tattoo on the right lower leg. The patient reported pruritus in the affected areas that occurred immediately after obtaining the tattoo, which was her first and only tattoo. She denied any pertinent medical history, including an absence of immunosuppression and autoimmune or chronic inflammatory diseases.

Physical examination revealed scaly and crusted plaques isolated to areas of purple tattoo pigment (Figure 1). Areas of red, green, black, and blue pigmentation within the tattoo were uninvolved. With the initial suspicion of allergic contact dermatitis, two 6-mm punch biopsies were taken from adjacent linear plaques on the right leg for histology and tissue culture. Histopathologic evaluation revealed dermal tattoo pigment with overlying PEH and was negative for signs of infection (Figure 2). Infectious stains such as periodic acid–Schiff, Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver, and Gram stains were performed and found to be negative. In addition, culture for mycobacteria came back negative. Prurigo was on the differential; however, histopathologic changes were more compatible with a PEH reaction to the tattoo.

Upon diagnosis, the patient was treated with clobetasol ointment 0.05% under occlusion for 1 month without reported improvement. The patient subsequently elected to undergo treatment with intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL to all areas of PEH, except the areas immediately surrounding the healing biopsy sites. Twice-daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% to all affected areas also was initiated. At follow-up 1 month later, she reported symptomatic relief of pruritus with a notable reduction in the thickness of the plaques in all treated areas (Figure 3). A second course of intralesional triamcinolone 5 mg/mL was performed. No additional plaques appeared during the treatment course, and the patient reported high satisfaction with the final result that was achieved.

An increase in the popularity of tattooing has led to more reports of various tattoo skin reactions.4-6 The differential diagnosis is broad for tattoo reactions and includes granulomatous inflammation, sarcoidosis, psoriasis (Köbner phenomenon), allergic contact dermatitis, lichen planus, morphealike reactions, squamous cell carcinoma, and keratoacanthoma,5 which makes clinicopathologic correlation essential for accurate diagnosis. Our case demonstrated the characteristic epithelial hyperplasia in the absence of cytologic atypia. In addition, the presence of mixed dermal inflammation histologically was noted in our patient.

Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia development from a tattoo in areas of both mercury-based and non–mercury-based red pigment is a known association.7-9 Balfour et al10 also reported a case of PEH occurring secondary to manganese-based purple pigment. Because few cases have been reported, the epidemiology for PEH currently is unknown. Treatment of this condition primarily is anecdotal, with prior cases showing success with topical or intralesional steroids.5,7 As with any steroid-based treatment, we recommend less aggressive treatments initially with close follow-up and adaptation as needed to minimize adverse effects such as unwanted atrophy. Some success has been reported with the use of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in the setting of a PEH tattoo reaction.5 Similar to other tattoo reactions, surgical removal can be considered with failure of more conservative treatment methods and focal involvement.

We report an unusual case of PEH occurring secondary to purple tattoo pigment. Our report also demonstrates the clinical and symptomatic improvement of PEH that can be achieved through the use of intralesional corticosteroid therapy. Our patient represents a case of PEH reactive to tattooing with purple ink. Further research to elucidate the precise pathogenesis of PEH tattoo reactions would be helpful in identifying high-risk patients and determining the most efficacious treatments.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

- Meani RE, Nixon RL, O’Keefe R, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia secondary to allergic contact dermatitis to Grevillea Robyn Gordon. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E8-E10.

- Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P, Agrawal D, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a clinical entity mistaken for squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7:232.

- Kluger N. Issues with keratoacanthoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and squamous cell carcinoma within tattoos: a clinical point of view. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;37:812-813.

- Zayour M, Lazova R. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: a review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:112-126.

- Bassi A, Campolmi P, Cannarozzo G, et al. Tattoo-associated skin reaction: the importance of an early diagnosis and proper treatment [published online July 23, 2014]. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:354608.

- Serup J. Diagnostic tools for doctors’ evaluation of tattoo complications. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2017;52:42-57.

- Kazlouskaya V, Junkins-Hopkins JM. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in a red pigment tattoo: a separate entity or hypertrophic lichen planus-like reaction? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8:48-52.

- Kluger N, Durand L, Minier-Thoumin C, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia in tattoos: report of three cases. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:337-340.

- Cui W, McGregor DH, Stark SP, et al. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia—an unusual reaction following tattoo: report of a case and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:743-745.

- Balfour E, Olhoffer I, Leffell D, et al. Massive pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia: an unusual reaction to a tattoo. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:338-340.

Practice Points

- Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (PEH) is a rare benign condition that can arise in response to multiple underlying triggers such as tattoo pigment.

- Histopathologic evaluation is essential for diagnosis and shows characteristic hyperplasia of the epidermis.

- Clinicians should consider intralesional steroids in the treatment of PEH once atypical mycobacterial and deep fungal infections have been ruled out.

Vaginal cleansing at cesarean delivery works in practice

Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery was successfully implemented – and significantly decreased the rate of surgical site infections (SSI) – in a quality improvement study done at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

“Our goal was not to prove that vaginal preparation [before cesarean section] works, because that’s already been shown in large randomized, controlled trials, but to show that we can implement it and that we can see the same results in real life,” lead investigator Johanna Quist-Nelson, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Quist-Nelson, a third-year fellow at the hospital and the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, was scheduled to present the findings at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

Resident and staff physicians as well as nursing and operating room staff were educated/reminded through a multipronged intervention about the benefits of vaginal cleansing with a sponge stick preparation of 10% povidone-iodine solution (Betadine) – and later about the potential benefits of intravenous azithromycin – immediately before cesarean delivery for women in labor and women with ruptured membranes.

Dr. Quist-Nelson and coinvestigators compared three periods of time: 12 months preintervention, 14 months with vaginal cleansing promoted for infection prophylaxis, and 16 months of instructions for both vaginal cleansing and intravenous azithromycin. The three periods captured 1,033 patients. The researchers used control charts – a tool “often used in implementation science,” she said – to analyze monthly data and assess trends for SSI rates and for compliance.

The rate of SSI – as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – decreased by 33%, they found, from 23% to 15%. The drop occurred mainly 4 months into the vaginal cleansing portion of the study and was sustained during the following 26 months. The addition of intravenous azithromycin education did not result in any further change in the SSI rate, Dr. Quist-Nelson and associates reported in the study – the abstract for which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. It won a third-place prize among the papers on current clinical and basic investigation.

Compliance with the vaginal cleansing protocol increased from 60% at the start of the vaginal cleansing phase to 85% 1 year later. Azithromycin compliance rose to 75% over the third phase of the intervention.

Vaginal cleansing has received attention at Thomas Jefferson for several years. In 2017, researchers there collaborated with investigators in Italy on a systemic review and meta-analysis which concluded that women who received vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery – most commonly with 10% povidine-iodine – had a significantly lower incidence of endometritis (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;130[3]:527-38).

A subgroup analysis showed that Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

Azithromycin similarly was found to reduce the risk of postoperative infection in women undergoing nonelective cesarean deliveries in a randomized trial published in 2016 (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375[13]:1231-41). While the new quality improvement study did not suggest any additional benefit to intravenous azithromycin, “we continue to offer it [at our hospital] because it has been shown [in prior research] to be beneficial and because our study wasn’t [designed] to show benefit,” Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

The quality improvement intervention included hands-on training on vaginal cleansing for resident physicians and e-mail reminders for physician staff, and daily reviews for 1 week on intravenous azithromycin for resident physicians and EMR “best practice advisory” reminders for physician staff. “We also wrote a protocol available online, and put reminders in our OR notes, as well as trained the nursing staff and OR staff,” she said.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Davis, said in an interview that SSI rates are “problematic [in obstetrics], not only because of morbidity but also potential cost because of rehospitalization.” The study shows that vaginal cleansing “is absolutely a good target for quality improvement,” she said. “It’s promising, and very exciting to see something like this have such a dramatic positive result.” Dr. Cansino, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn News editorial advisory board, was not involved in this study.

Thomas Jefferson Hospital has had relatively high SSI rates, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted.

Dr. Quist-Nelson and coinvestigators did not report any potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Cansino also did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Quist-Nelson J et al. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020 May;135:1S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662876.23603.13.

Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery was successfully implemented – and significantly decreased the rate of surgical site infections (SSI) – in a quality improvement study done at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

“Our goal was not to prove that vaginal preparation [before cesarean section] works, because that’s already been shown in large randomized, controlled trials, but to show that we can implement it and that we can see the same results in real life,” lead investigator Johanna Quist-Nelson, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Quist-Nelson, a third-year fellow at the hospital and the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, was scheduled to present the findings at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

Resident and staff physicians as well as nursing and operating room staff were educated/reminded through a multipronged intervention about the benefits of vaginal cleansing with a sponge stick preparation of 10% povidone-iodine solution (Betadine) – and later about the potential benefits of intravenous azithromycin – immediately before cesarean delivery for women in labor and women with ruptured membranes.

Dr. Quist-Nelson and coinvestigators compared three periods of time: 12 months preintervention, 14 months with vaginal cleansing promoted for infection prophylaxis, and 16 months of instructions for both vaginal cleansing and intravenous azithromycin. The three periods captured 1,033 patients. The researchers used control charts – a tool “often used in implementation science,” she said – to analyze monthly data and assess trends for SSI rates and for compliance.

The rate of SSI – as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – decreased by 33%, they found, from 23% to 15%. The drop occurred mainly 4 months into the vaginal cleansing portion of the study and was sustained during the following 26 months. The addition of intravenous azithromycin education did not result in any further change in the SSI rate, Dr. Quist-Nelson and associates reported in the study – the abstract for which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. It won a third-place prize among the papers on current clinical and basic investigation.

Compliance with the vaginal cleansing protocol increased from 60% at the start of the vaginal cleansing phase to 85% 1 year later. Azithromycin compliance rose to 75% over the third phase of the intervention.

Vaginal cleansing has received attention at Thomas Jefferson for several years. In 2017, researchers there collaborated with investigators in Italy on a systemic review and meta-analysis which concluded that women who received vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery – most commonly with 10% povidine-iodine – had a significantly lower incidence of endometritis (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;130[3]:527-38).

A subgroup analysis showed that Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

Azithromycin similarly was found to reduce the risk of postoperative infection in women undergoing nonelective cesarean deliveries in a randomized trial published in 2016 (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375[13]:1231-41). While the new quality improvement study did not suggest any additional benefit to intravenous azithromycin, “we continue to offer it [at our hospital] because it has been shown [in prior research] to be beneficial and because our study wasn’t [designed] to show benefit,” Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

The quality improvement intervention included hands-on training on vaginal cleansing for resident physicians and e-mail reminders for physician staff, and daily reviews for 1 week on intravenous azithromycin for resident physicians and EMR “best practice advisory” reminders for physician staff. “We also wrote a protocol available online, and put reminders in our OR notes, as well as trained the nursing staff and OR staff,” she said.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Davis, said in an interview that SSI rates are “problematic [in obstetrics], not only because of morbidity but also potential cost because of rehospitalization.” The study shows that vaginal cleansing “is absolutely a good target for quality improvement,” she said. “It’s promising, and very exciting to see something like this have such a dramatic positive result.” Dr. Cansino, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn News editorial advisory board, was not involved in this study.

Thomas Jefferson Hospital has had relatively high SSI rates, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted.

Dr. Quist-Nelson and coinvestigators did not report any potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Cansino also did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Quist-Nelson J et al. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020 May;135:1S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662876.23603.13.

Vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery was successfully implemented – and significantly decreased the rate of surgical site infections (SSI) – in a quality improvement study done at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia.

“Our goal was not to prove that vaginal preparation [before cesarean section] works, because that’s already been shown in large randomized, controlled trials, but to show that we can implement it and that we can see the same results in real life,” lead investigator Johanna Quist-Nelson, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Quist-Nelson, a third-year fellow at the hospital and the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia, was scheduled to present the findings at the annual clinical and scientific meeting of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG canceled the meeting and released abstracts for press coverage.

Resident and staff physicians as well as nursing and operating room staff were educated/reminded through a multipronged intervention about the benefits of vaginal cleansing with a sponge stick preparation of 10% povidone-iodine solution (Betadine) – and later about the potential benefits of intravenous azithromycin – immediately before cesarean delivery for women in labor and women with ruptured membranes.

Dr. Quist-Nelson and coinvestigators compared three periods of time: 12 months preintervention, 14 months with vaginal cleansing promoted for infection prophylaxis, and 16 months of instructions for both vaginal cleansing and intravenous azithromycin. The three periods captured 1,033 patients. The researchers used control charts – a tool “often used in implementation science,” she said – to analyze monthly data and assess trends for SSI rates and for compliance.

The rate of SSI – as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – decreased by 33%, they found, from 23% to 15%. The drop occurred mainly 4 months into the vaginal cleansing portion of the study and was sustained during the following 26 months. The addition of intravenous azithromycin education did not result in any further change in the SSI rate, Dr. Quist-Nelson and associates reported in the study – the abstract for which was published in Obstetrics & Gynecology. It won a third-place prize among the papers on current clinical and basic investigation.

Compliance with the vaginal cleansing protocol increased from 60% at the start of the vaginal cleansing phase to 85% 1 year later. Azithromycin compliance rose to 75% over the third phase of the intervention.

Vaginal cleansing has received attention at Thomas Jefferson for several years. In 2017, researchers there collaborated with investigators in Italy on a systemic review and meta-analysis which concluded that women who received vaginal cleansing before cesarean delivery – most commonly with 10% povidine-iodine – had a significantly lower incidence of endometritis (Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Sep;130[3]:527-38).

A subgroup analysis showed that Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

Azithromycin similarly was found to reduce the risk of postoperative infection in women undergoing nonelective cesarean deliveries in a randomized trial published in 2016 (N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375[13]:1231-41). While the new quality improvement study did not suggest any additional benefit to intravenous azithromycin, “we continue to offer it [at our hospital] because it has been shown [in prior research] to be beneficial and because our study wasn’t [designed] to show benefit,” Dr. Quist-Nelson said.

The quality improvement intervention included hands-on training on vaginal cleansing for resident physicians and e-mail reminders for physician staff, and daily reviews for 1 week on intravenous azithromycin for resident physicians and EMR “best practice advisory” reminders for physician staff. “We also wrote a protocol available online, and put reminders in our OR notes, as well as trained the nursing staff and OR staff,” she said.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, of the University of California, Davis, said in an interview that SSI rates are “problematic [in obstetrics], not only because of morbidity but also potential cost because of rehospitalization.” The study shows that vaginal cleansing “is absolutely a good target for quality improvement,” she said. “It’s promising, and very exciting to see something like this have such a dramatic positive result.” Dr. Cansino, who is a member of the Ob.Gyn News editorial advisory board, was not involved in this study.

Thomas Jefferson Hospital has had relatively high SSI rates, Dr. Quist-Nelson noted.

Dr. Quist-Nelson and coinvestigators did not report any potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Cansino also did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Quist-Nelson J et al. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020 May;135:1S. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662876.23603.13.

REPORTING FROM ACOG 2020

Seniors with COVID-19 show unusual symptoms, doctors say

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.

Quratulain Syed, MD, an Atlanta geriatrician, describes a man in his 80s whom she treated in mid-March. Over a period of days, this patient, who had heart disease, diabetes and moderate cognitive impairment, stopped walking and became incontinent and profoundly lethargic. But he didn’t have a fever or a cough. His only respiratory symptom: sneezing off and on.

The man’s elderly spouse called 911 twice. Both times, paramedics checked his vital signs and declared he was OK. After another worried call from the overwhelmed spouse, Dr. Syed insisted the patient be taken to the hospital, where he tested positive for COVID-19.

“I was quite concerned about the paramedics and health aides who’d been in the house and who hadn’t used PPE [personal protective equipment],” Dr. Syed said.

Dr. Sam Torbati, medical director of the emergency department at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, describes treating seniors who initially appear to be trauma patients but are found to have COVID-19.

“They get weak and dehydrated,” he said, “and when they stand to walk, they collapse and injure themselves badly.”

Dr. Torbati has seen older adults who are profoundly disoriented and unable to speak and who appear at first to have suffered strokes.

“When we test them, we discover that what’s producing these changes is a central nervous system effect of coronavirus,” he said.

Laura Perry, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, saw a patient like this several weeks ago. The woman, in her 80s, had what seemed to be a cold before becoming very confused. In the hospital, she couldn’t identify where she was or stay awake during an examination. Dr. Perry diagnosed hypoactive delirium, an altered mental state in which people become inactive and drowsy. The patient tested positive for coronavirus and is still in the ICU.

Anthony Perry, MD, of the department of geriatric medicine at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, tells of an 81-year-old woman with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea who tested positive for COVID-19 in the emergency room. After receiving intravenous fluids, oxygen, and medication for her intestinal upset, she returned home after 2 days and is doing well.

Another 80-year-old Rush patient with similar symptoms – nausea and vomiting, but no cough, fever, or shortness of breath – is in intensive care after getting a positive COVID-19 test and due to be put on a ventilator. The difference? This patient is frail with “a lot of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Perry said. Other than that, it’s not yet clear why some older patients do well while others do not.

So far, reports of cases like these have been anecdotal. But a few physicians are trying to gather more systematic information.

In Switzerland, Sylvain Nguyen, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Lausanne Hospital Center, put together a list of typical and atypical symptoms in older COVID-19 patients for a paper to be published in the Revue Médicale Suisse. Included on the atypical list are changes in a patient’s usual status, delirium, falls, fatigue, lethargy, low blood pressure, painful swallowing, fainting, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and the loss of smell and taste.

Data come from hospitals and nursing homes in Switzerland, Italy, and France, Dr. Nguyen said in an email.

On the front lines, physicians need to make sure they carefully assess an older patient’s symptoms.

“While we have to have a high suspicion of COVID-19 because it’s so dangerous in the older population, there are many other things to consider,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, a geriatrician at Indiana University, Indianapolis.

Seniors may also do poorly because their routines have changed. In nursing homes and most assisted living centers, activities have stopped and “residents are going to get weaker and more deconditioned because they’re not walking to and from the dining hall,” she said.

At home, isolated seniors may not be getting as much help with medication management or other essential needs from family members who are keeping their distance, other experts suggested. Or they may have become apathetic or depressed.

“I’d want to know ‘What’s the potential this person has had an exposure [to the coronavirus], especially in the last 2 weeks?’ ” said Dr. Vaughan of Emory. “Do they have home health personnel coming in? Have they gotten together with other family members? Are chronic conditions being controlled? Is there another diagnosis that seems more likely?”

“Someone may be just having a bad day. But if they’re not themselves for a couple of days, absolutely reach out to a primary care doctor or a local health system hotline to see if they meet the threshold for [coronavirus] testing,” Dr. Vaughan advised. “Be persistent. If you get a ‘no’ the first time and things aren’t improving, call back and ask again.”

Kaiser Health News (khn.org) is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

complicating efforts to ensure they get timely and appropriate treatment, according to physicians.

COVID-19 is typically signaled by three symptoms: a fever, an insistent cough, and shortness of breath. But older adults – the age group most at risk of severe complications or death from this condition – may have none of these characteristics.

Instead, seniors may seem “off” – not acting like themselves – early on after being infected by the coronavirus. They may sleep more than usual or stop eating. They may seem unusually apathetic or confused, losing orientation to their surroundings. They may become dizzy and fall. Sometimes, seniors stop speaking or simply collapse.

“With a lot of conditions, older adults don’t present in a typical way, and we’re seeing that with COVID-19 as well,” said Camille Vaughan, MD, section chief of geriatrics and gerontology at Emory University, Atlanta.

The reason has to do with how older bodies respond to illness and infection.

At advanced ages, “someone’s immune response may be blunted and their ability to regulate temperature may be altered,” said Dr. Joseph Ouslander, a professor of geriatric medicine at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton.

“Underlying chronic illnesses can mask or interfere with signs of infection,” he said. “Some older people, whether from age-related changes or previous neurologic issues such as a stroke, may have altered cough reflexes. Others with cognitive impairment may not be able to communicate their symptoms.”

Recognizing danger signs is important: If early signs of COVID-19 are missed, seniors may deteriorate before getting needed care. And people may go in and out of their homes without adequate protective measures, risking the spread of infection.