User login

IDSA guidelines cover N95 use and reuse

The Infectious Disease Society of America has released new guidelines on the use and reuse of personal protective equipment, most of which address the use of face protection, for health care workers caring for COVID-19 patients. In releasing the guidelines, the IDSA expert guideline panel acknowledged gaps in evidence to support the recommendations, which is why they will be updated regularly as new evidence emerges.

“Our real goal here is to update these guidelines as a live document,” panel chair John Lynch III, MD, MPH, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in a press briefing. “Looking at whatever research is coming out where it gets to the point where we find that the evidence is strong enough to make a change, I think we’ll need to readdress these recommendations.”

The panel tailored recommendations to the availability of supplies: conventional capacity for usual supplies; contingency capacity, when supplies are conserved, adapted and substituted with occasional reuse of select supplies; and crisis capacity, when critical supplies are lacking.

The guidelines contain the following eight recommendations for encounters with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients:

1) Either a surgical mask or N95 (or N99 or PAPR [powered & supplied air respiratory protection]) respirator for routine patient care in a conventional setting.

2) Either a surgical mask or reprocessed respirator as opposed to no mask for routine care in a contingency or crisis setting.

3) No recommendation on the use of double gloves vs. single gloves.

4) No recommendation on the use of shoe covers for any setting.

5) An N95 (or N99 or PAPR) respirator for aerosol-generating procedures in a conventional setting.

6) A reprocessed N95 respirator as opposed to a surgical mask for aerosol-generating procedures in a contingency or crisis setting.

7) Adding a face shield or surgical mask as a cover for an N95 respirator to allow for extended use during respirator shortages when performing aerosol-generating procedures in a contingency or crisis setting. This recommendation carries a caveat: It assumes correct doffing sequence and hand hygiene before and after taking off the face shield or surgical mask cover.

8) In the same scenario, adding a face shield or surgical mask over the N95 respirator so it can be reused, again assuming the correct sequence for hand hygiene.

The guideline was developed using the GRADE approach – for Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation – and a modified methodology for developing rapid recommendations. The levels of evidence supporting each recommendation vary from moderate for the first two to knowledge gap for the third and fourth to very low certainty for the last four.

“You can see that the eight recommendations that were made, a large part of them are really focused on masks, but there are a huge number of other disparate questions that need to be answered where there is really no good evidence basis,” Dr. Lynch said. “If we see any new evidence around that, we can at least provide commentary but I would really hope evidence-based recommendations around some of those interventions.”

Panel member Allison McGeer, MD, FRCPC, of the University of Toronto, explained the lack of evidence supporting infection prevention in hospitals. “In medicine we tend to look at individual patterns and individual patient outcomes,” she said. “When you’re looking at infection prevention, you’re looking at health systems and their outcomes, and it’s much harder to randomize hospitals or a state or a country to one particular policy about how to protect patients from infections in hospitals.”

The latest guidelines follow IDSA’s previously released guidelines on treatment and management of COVID-19 patients. The panel also plans to release guidelines on use of diagnostics for COVID-19 care.

Dr. Lynch has no financial relationships to disclose. Dr. McGeer disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, GlaxoSmithKline and Cidara.

SOURCE: Lynch JB et al. IDSA. April 27, 2020.

The Infectious Disease Society of America has released new guidelines on the use and reuse of personal protective equipment, most of which address the use of face protection, for health care workers caring for COVID-19 patients. In releasing the guidelines, the IDSA expert guideline panel acknowledged gaps in evidence to support the recommendations, which is why they will be updated regularly as new evidence emerges.

“Our real goal here is to update these guidelines as a live document,” panel chair John Lynch III, MD, MPH, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in a press briefing. “Looking at whatever research is coming out where it gets to the point where we find that the evidence is strong enough to make a change, I think we’ll need to readdress these recommendations.”

The panel tailored recommendations to the availability of supplies: conventional capacity for usual supplies; contingency capacity, when supplies are conserved, adapted and substituted with occasional reuse of select supplies; and crisis capacity, when critical supplies are lacking.

The guidelines contain the following eight recommendations for encounters with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients:

1) Either a surgical mask or N95 (or N99 or PAPR [powered & supplied air respiratory protection]) respirator for routine patient care in a conventional setting.

2) Either a surgical mask or reprocessed respirator as opposed to no mask for routine care in a contingency or crisis setting.

3) No recommendation on the use of double gloves vs. single gloves.

4) No recommendation on the use of shoe covers for any setting.

5) An N95 (or N99 or PAPR) respirator for aerosol-generating procedures in a conventional setting.

6) A reprocessed N95 respirator as opposed to a surgical mask for aerosol-generating procedures in a contingency or crisis setting.

7) Adding a face shield or surgical mask as a cover for an N95 respirator to allow for extended use during respirator shortages when performing aerosol-generating procedures in a contingency or crisis setting. This recommendation carries a caveat: It assumes correct doffing sequence and hand hygiene before and after taking off the face shield or surgical mask cover.

8) In the same scenario, adding a face shield or surgical mask over the N95 respirator so it can be reused, again assuming the correct sequence for hand hygiene.

The guideline was developed using the GRADE approach – for Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation – and a modified methodology for developing rapid recommendations. The levels of evidence supporting each recommendation vary from moderate for the first two to knowledge gap for the third and fourth to very low certainty for the last four.

“You can see that the eight recommendations that were made, a large part of them are really focused on masks, but there are a huge number of other disparate questions that need to be answered where there is really no good evidence basis,” Dr. Lynch said. “If we see any new evidence around that, we can at least provide commentary but I would really hope evidence-based recommendations around some of those interventions.”

Panel member Allison McGeer, MD, FRCPC, of the University of Toronto, explained the lack of evidence supporting infection prevention in hospitals. “In medicine we tend to look at individual patterns and individual patient outcomes,” she said. “When you’re looking at infection prevention, you’re looking at health systems and their outcomes, and it’s much harder to randomize hospitals or a state or a country to one particular policy about how to protect patients from infections in hospitals.”

The latest guidelines follow IDSA’s previously released guidelines on treatment and management of COVID-19 patients. The panel also plans to release guidelines on use of diagnostics for COVID-19 care.

Dr. Lynch has no financial relationships to disclose. Dr. McGeer disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, GlaxoSmithKline and Cidara.

SOURCE: Lynch JB et al. IDSA. April 27, 2020.

The Infectious Disease Society of America has released new guidelines on the use and reuse of personal protective equipment, most of which address the use of face protection, for health care workers caring for COVID-19 patients. In releasing the guidelines, the IDSA expert guideline panel acknowledged gaps in evidence to support the recommendations, which is why they will be updated regularly as new evidence emerges.

“Our real goal here is to update these guidelines as a live document,” panel chair John Lynch III, MD, MPH, of the University of Washington, Seattle, said in a press briefing. “Looking at whatever research is coming out where it gets to the point where we find that the evidence is strong enough to make a change, I think we’ll need to readdress these recommendations.”

The panel tailored recommendations to the availability of supplies: conventional capacity for usual supplies; contingency capacity, when supplies are conserved, adapted and substituted with occasional reuse of select supplies; and crisis capacity, when critical supplies are lacking.

The guidelines contain the following eight recommendations for encounters with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients:

1) Either a surgical mask or N95 (or N99 or PAPR [powered & supplied air respiratory protection]) respirator for routine patient care in a conventional setting.

2) Either a surgical mask or reprocessed respirator as opposed to no mask for routine care in a contingency or crisis setting.

3) No recommendation on the use of double gloves vs. single gloves.

4) No recommendation on the use of shoe covers for any setting.

5) An N95 (or N99 or PAPR) respirator for aerosol-generating procedures in a conventional setting.

6) A reprocessed N95 respirator as opposed to a surgical mask for aerosol-generating procedures in a contingency or crisis setting.

7) Adding a face shield or surgical mask as a cover for an N95 respirator to allow for extended use during respirator shortages when performing aerosol-generating procedures in a contingency or crisis setting. This recommendation carries a caveat: It assumes correct doffing sequence and hand hygiene before and after taking off the face shield or surgical mask cover.

8) In the same scenario, adding a face shield or surgical mask over the N95 respirator so it can be reused, again assuming the correct sequence for hand hygiene.

The guideline was developed using the GRADE approach – for Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation – and a modified methodology for developing rapid recommendations. The levels of evidence supporting each recommendation vary from moderate for the first two to knowledge gap for the third and fourth to very low certainty for the last four.

“You can see that the eight recommendations that were made, a large part of them are really focused on masks, but there are a huge number of other disparate questions that need to be answered where there is really no good evidence basis,” Dr. Lynch said. “If we see any new evidence around that, we can at least provide commentary but I would really hope evidence-based recommendations around some of those interventions.”

Panel member Allison McGeer, MD, FRCPC, of the University of Toronto, explained the lack of evidence supporting infection prevention in hospitals. “In medicine we tend to look at individual patterns and individual patient outcomes,” she said. “When you’re looking at infection prevention, you’re looking at health systems and their outcomes, and it’s much harder to randomize hospitals or a state or a country to one particular policy about how to protect patients from infections in hospitals.”

The latest guidelines follow IDSA’s previously released guidelines on treatment and management of COVID-19 patients. The panel also plans to release guidelines on use of diagnostics for COVID-19 care.

Dr. Lynch has no financial relationships to disclose. Dr. McGeer disclosed relationships with Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, GlaxoSmithKline and Cidara.

SOURCE: Lynch JB et al. IDSA. April 27, 2020.

FROM INFECTIOUS DISEASE SOCIETY OF AMERICA

New tetracycline antibiotic effective in community-acquired bacterial pneumonia

Background: Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a leading cause of hospitalization and death, particularly in the elderly. Omadacycline is a new once-daily tetracycline with in vitro activity against a wide range of CAP pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and atypical organisms, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia pneumoniae.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Hospitalized patients (98.8%) in non-ICU settings at 86 sites in Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 774 adults with three or more CAP symptoms (cough, purulent sputum production, dyspnea, or pleuritic chest pain) and at least two abnormal vital signs, one or more clinical signs or laboratory findings associated with CAP, radiologically confirmed pneumonia, and a Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) of II, III, or IV (with higher class numbers indicating a greater risk of death). Exclusion criteria included having clinically significant liver or renal insufficiency or having an immunocompromised state. The patients were randomized to receive either omadacycline or moxifloxacin intravenously with the option to switch to the oral preparation of the respective drugs after at least 3 days of therapy. Atypical organisms were implicated in 67% of CAPS with known cause, while Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae were implicated in 20% and 12%, respectively. Omadacycline was noninferior to moxifloxacin with respect to early clinical response (81.1% vs 82.7%, respectively) and posttreatment clinical response rates (87.6% vs. 85.1%). Mean duration of IV therapy was 5.7 days, and the mean total duration of therapy was 9.6 days in both groups. The frequency of adverse events (primarily gastrointestinal) was similar between the two groups.

Exclusion of the most severe CAP and immunocompromised patients limits generalizability of these results.

Bottom line: Omadacycline provides similar clinical benefit as moxifloxacin in the treatment of selected patients with CAP.

Citation: Stets R et al. Omadacycline for community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. N Eng J Med. 2019;380:517-27.

Dr. Manian is a core educator faculty member in the department of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a leading cause of hospitalization and death, particularly in the elderly. Omadacycline is a new once-daily tetracycline with in vitro activity against a wide range of CAP pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and atypical organisms, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia pneumoniae.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Hospitalized patients (98.8%) in non-ICU settings at 86 sites in Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 774 adults with three or more CAP symptoms (cough, purulent sputum production, dyspnea, or pleuritic chest pain) and at least two abnormal vital signs, one or more clinical signs or laboratory findings associated with CAP, radiologically confirmed pneumonia, and a Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) of II, III, or IV (with higher class numbers indicating a greater risk of death). Exclusion criteria included having clinically significant liver or renal insufficiency or having an immunocompromised state. The patients were randomized to receive either omadacycline or moxifloxacin intravenously with the option to switch to the oral preparation of the respective drugs after at least 3 days of therapy. Atypical organisms were implicated in 67% of CAPS with known cause, while Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae were implicated in 20% and 12%, respectively. Omadacycline was noninferior to moxifloxacin with respect to early clinical response (81.1% vs 82.7%, respectively) and posttreatment clinical response rates (87.6% vs. 85.1%). Mean duration of IV therapy was 5.7 days, and the mean total duration of therapy was 9.6 days in both groups. The frequency of adverse events (primarily gastrointestinal) was similar between the two groups.

Exclusion of the most severe CAP and immunocompromised patients limits generalizability of these results.

Bottom line: Omadacycline provides similar clinical benefit as moxifloxacin in the treatment of selected patients with CAP.

Citation: Stets R et al. Omadacycline for community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. N Eng J Med. 2019;380:517-27.

Dr. Manian is a core educator faculty member in the department of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a leading cause of hospitalization and death, particularly in the elderly. Omadacycline is a new once-daily tetracycline with in vitro activity against a wide range of CAP pathogens, including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and atypical organisms, such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Chlamydia pneumoniae.

Study design: Phase 3 randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, placebo-controlled trial.

Setting: Hospitalized patients (98.8%) in non-ICU settings at 86 sites in Europe, North America, South America, the Middle East, Africa, and Asia.

Synopsis: The trial recruited 774 adults with three or more CAP symptoms (cough, purulent sputum production, dyspnea, or pleuritic chest pain) and at least two abnormal vital signs, one or more clinical signs or laboratory findings associated with CAP, radiologically confirmed pneumonia, and a Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) of II, III, or IV (with higher class numbers indicating a greater risk of death). Exclusion criteria included having clinically significant liver or renal insufficiency or having an immunocompromised state. The patients were randomized to receive either omadacycline or moxifloxacin intravenously with the option to switch to the oral preparation of the respective drugs after at least 3 days of therapy. Atypical organisms were implicated in 67% of CAPS with known cause, while Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae were implicated in 20% and 12%, respectively. Omadacycline was noninferior to moxifloxacin with respect to early clinical response (81.1% vs 82.7%, respectively) and posttreatment clinical response rates (87.6% vs. 85.1%). Mean duration of IV therapy was 5.7 days, and the mean total duration of therapy was 9.6 days in both groups. The frequency of adverse events (primarily gastrointestinal) was similar between the two groups.

Exclusion of the most severe CAP and immunocompromised patients limits generalizability of these results.

Bottom line: Omadacycline provides similar clinical benefit as moxifloxacin in the treatment of selected patients with CAP.

Citation: Stets R et al. Omadacycline for community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. N Eng J Med. 2019;380:517-27.

Dr. Manian is a core educator faculty member in the department of medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Remdesivir now ‘standard of care’ for COVID-19, Fauci says

, according to a preliminary data analysis from a U.S.-led randomized, controlled trial.

On the basis of as yet unpublished data, remdesivir “will be the standard of care” for patients with COVID-19, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said during a press conference at the White House April 29.

The randomized, placebo-controlled international trial was sponsored by NIAID, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, and enrolled 1,063 patients. It began on Feb. 21.

The interim results, discussed in the press conference and in a NIAID press release, show that time to recovery (i.e., being well enough for hospital discharge or to return to normal activity level) was 31% faster for patients who received remdesivir than for those who received placebo (P < .001).

The median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir, compared with 15 days for those who received placebo. Results also suggested a survival benefit, with a mortality rate of 8.0% for the group receiving remdesivir and 11.6% for the patients who received placebo (P = .059).

The study, known as the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT), is the first clinical trial launched in the United States to evaluate an experimental treatment for COVID-19. It is being conducted at 68 sites – 47 in the United States and 21 in countries in Europe and Asia.

The data are being released after an interim review by the independent data safety monitoring board found significant benefit with the drug, Dr. Fauci said.

“The reason we are making the announcement now is something that people don’t fully appreciate: Whenever you have clear-cut evidence that a drug works, you have an ethical obligation to let the people in the placebo group know so they could have access,” he explained.

“When I was looking at the data with our team the other night, it was reminiscent of 34 years ago in 1986 when we were struggling for drugs for HIV,” said Dr. Fauci, who was a key figure in HIV/AIDS research. “We did the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial with AZT. It turned out to have an effect that was modest but that was not the endgame because, building on that, every year after, we did better and better.”

Similarly, new trials of drugs for COVID-19 will build on remdesivir, with other agents being added to block other pathways or viral enzymes, Dr. Fauci said.

The study will be submitted to a journal for peer review, he noted, but the New York Times is reporting that the Food and Drug Administration will approve remdesivir for emergency use soon.

In contrast to the positive results Dr. Fauci described from the NIAID-sponsored trial, a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of remdesivir among hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 in China was inconclusive.

The study, published online in The Lancet, showed some nonsignificant trends toward benefit but did not meet its primary endpoint.

The study was stopped early after 237 of the intended 453 patients were enrolled, owing to a lack of additional patients who met the eligibility criteria. The trial was thus underpowered.

Results showed that treatment with remdesivir did not significantly speed recovery or reduce deaths from COVID-19, but with regard to prespecified secondary outcomes, time to clinical improvement and duration of invasive mechanical ventilation were shorter among a subgroup of patients who began undergoing treatment with remdesivir within 10 days of showing symptoms, in comparison with patients who received standard care.

“To me, the studies reported here in The Lancet appear to be less promising than some statements released today from the NIH, so the situation is a bit puzzling to me,” said Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the study. “I would need to look more closely at the data which NIH is looking at to understand the differences.”

Trial details

The published trial was conducted at 10 hospitals in Hubei, China. Enrollment criteria included being admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection within 12 days of symptom onset, having oxygen saturation of 94% or less, and having radiologically confirmed pneumonia.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive intravenous remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg on days 2–10 in single daily infusions) or placebo infusions for 10 days. Patients were permitted concomitant use of lopinavir-ritonavir, interferons, and corticosteroids.

The primary endpoint was time to clinical improvement to day 28, defined as the time (in days) from randomization to the point of a decline of two levels on a six-point ordinal scale of clinical status (on that scale, 1 indicated that the patient was discharged, and 6 indicated death) or to the patient’s being discharged alive from hospital, whichever came first.

The trial was stopped early because stringent public health measures used in Wuhan led to marked reductions in new patient presentations and because lack of available hospital beds resulted in most patients being enrolled later in the course of disease.

Between Feb. 6, 2020, and March 12, 2020, 237 patients were enrolled and were randomly assigned to receive either remdesivir (n = 158) or placebo (n = 79).

Results showed that use of remdesivir was not associated with a difference in time to clinical improvement (hazard ratio [HR], 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-1.75).

Although not statistically significant, time to clinical improvement was numerically faster for patients who received remdesivir than for those who received placebo among patients with symptom duration of 10 days or less (median, 18 days vs. 23 days; HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.95-2.43).

The mortality rates were similar for the two groups (14% of patients who received remdesivir died vs. 13% of those who received placebo). There was no signal that viral load decreased differentially over time between the two groups.

Adverse events were reported in 66% of remdesivir recipients, vs. 64% of those who received placebo. Remdesivir was stopped early because of adverse events in 12% of patients; it was stopped early for 5% of those who received placebo.

The authors, led by Yeming Wang, MD, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, noted that compared with a previous study of compassionate use of remdesivir, the population in the current study was less ill and was treated somewhat earlier in the disease course (median, 10 days vs. 12 days).

Because the study was terminated early, the researchers said they could not adequately assess whether earlier treatment with remdesivir might have provided clinical benefit.

“However, among patients who were treated within 10 days of symptom onset, remdesivir was not a significant factor but was associated with a numerical reduction of 5 days in median time to clinical improvement,” they stated.

They added that remdesivir was adequately tolerated and that no new safety concerns were identified.

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, John David Norrie, MD, Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit, United Kingdom, pointed out that this study “has not shown a statistically significant finding that confirms a remdesivir treatment benefit of at least the minimally clinically important difference, nor has it ruled such a benefit out.”

Dr. Norrie was cautious about the fact that the subgroup analysis suggested possible benefit for those treated within 10 days.

Although he said it seems biologically plausible that treating patients earlier could be more effective, he added that “as well as being vigilant against overinterpretation, we need to ensure that hypotheses generated in efficacy-based trials, even in subgroups, are confirmed or refuted in subsequent adequately powered trials or meta-analyses.”

Noting that several other trials of remdesivir are underway, he concluded: “With each individual study at heightened risk of being incomplete, pooling data across possibly several underpowered but high-quality studies looks like our best way to obtain robust insights into what works, safely, and on whom.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a preliminary data analysis from a U.S.-led randomized, controlled trial.

On the basis of as yet unpublished data, remdesivir “will be the standard of care” for patients with COVID-19, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said during a press conference at the White House April 29.

The randomized, placebo-controlled international trial was sponsored by NIAID, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, and enrolled 1,063 patients. It began on Feb. 21.

The interim results, discussed in the press conference and in a NIAID press release, show that time to recovery (i.e., being well enough for hospital discharge or to return to normal activity level) was 31% faster for patients who received remdesivir than for those who received placebo (P < .001).

The median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir, compared with 15 days for those who received placebo. Results also suggested a survival benefit, with a mortality rate of 8.0% for the group receiving remdesivir and 11.6% for the patients who received placebo (P = .059).

The study, known as the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT), is the first clinical trial launched in the United States to evaluate an experimental treatment for COVID-19. It is being conducted at 68 sites – 47 in the United States and 21 in countries in Europe and Asia.

The data are being released after an interim review by the independent data safety monitoring board found significant benefit with the drug, Dr. Fauci said.

“The reason we are making the announcement now is something that people don’t fully appreciate: Whenever you have clear-cut evidence that a drug works, you have an ethical obligation to let the people in the placebo group know so they could have access,” he explained.

“When I was looking at the data with our team the other night, it was reminiscent of 34 years ago in 1986 when we were struggling for drugs for HIV,” said Dr. Fauci, who was a key figure in HIV/AIDS research. “We did the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial with AZT. It turned out to have an effect that was modest but that was not the endgame because, building on that, every year after, we did better and better.”

Similarly, new trials of drugs for COVID-19 will build on remdesivir, with other agents being added to block other pathways or viral enzymes, Dr. Fauci said.

The study will be submitted to a journal for peer review, he noted, but the New York Times is reporting that the Food and Drug Administration will approve remdesivir for emergency use soon.

In contrast to the positive results Dr. Fauci described from the NIAID-sponsored trial, a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of remdesivir among hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 in China was inconclusive.

The study, published online in The Lancet, showed some nonsignificant trends toward benefit but did not meet its primary endpoint.

The study was stopped early after 237 of the intended 453 patients were enrolled, owing to a lack of additional patients who met the eligibility criteria. The trial was thus underpowered.

Results showed that treatment with remdesivir did not significantly speed recovery or reduce deaths from COVID-19, but with regard to prespecified secondary outcomes, time to clinical improvement and duration of invasive mechanical ventilation were shorter among a subgroup of patients who began undergoing treatment with remdesivir within 10 days of showing symptoms, in comparison with patients who received standard care.

“To me, the studies reported here in The Lancet appear to be less promising than some statements released today from the NIH, so the situation is a bit puzzling to me,” said Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the study. “I would need to look more closely at the data which NIH is looking at to understand the differences.”

Trial details

The published trial was conducted at 10 hospitals in Hubei, China. Enrollment criteria included being admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection within 12 days of symptom onset, having oxygen saturation of 94% or less, and having radiologically confirmed pneumonia.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive intravenous remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg on days 2–10 in single daily infusions) or placebo infusions for 10 days. Patients were permitted concomitant use of lopinavir-ritonavir, interferons, and corticosteroids.

The primary endpoint was time to clinical improvement to day 28, defined as the time (in days) from randomization to the point of a decline of two levels on a six-point ordinal scale of clinical status (on that scale, 1 indicated that the patient was discharged, and 6 indicated death) or to the patient’s being discharged alive from hospital, whichever came first.

The trial was stopped early because stringent public health measures used in Wuhan led to marked reductions in new patient presentations and because lack of available hospital beds resulted in most patients being enrolled later in the course of disease.

Between Feb. 6, 2020, and March 12, 2020, 237 patients were enrolled and were randomly assigned to receive either remdesivir (n = 158) or placebo (n = 79).

Results showed that use of remdesivir was not associated with a difference in time to clinical improvement (hazard ratio [HR], 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-1.75).

Although not statistically significant, time to clinical improvement was numerically faster for patients who received remdesivir than for those who received placebo among patients with symptom duration of 10 days or less (median, 18 days vs. 23 days; HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.95-2.43).

The mortality rates were similar for the two groups (14% of patients who received remdesivir died vs. 13% of those who received placebo). There was no signal that viral load decreased differentially over time between the two groups.

Adverse events were reported in 66% of remdesivir recipients, vs. 64% of those who received placebo. Remdesivir was stopped early because of adverse events in 12% of patients; it was stopped early for 5% of those who received placebo.

The authors, led by Yeming Wang, MD, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, noted that compared with a previous study of compassionate use of remdesivir, the population in the current study was less ill and was treated somewhat earlier in the disease course (median, 10 days vs. 12 days).

Because the study was terminated early, the researchers said they could not adequately assess whether earlier treatment with remdesivir might have provided clinical benefit.

“However, among patients who were treated within 10 days of symptom onset, remdesivir was not a significant factor but was associated with a numerical reduction of 5 days in median time to clinical improvement,” they stated.

They added that remdesivir was adequately tolerated and that no new safety concerns were identified.

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, John David Norrie, MD, Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit, United Kingdom, pointed out that this study “has not shown a statistically significant finding that confirms a remdesivir treatment benefit of at least the minimally clinically important difference, nor has it ruled such a benefit out.”

Dr. Norrie was cautious about the fact that the subgroup analysis suggested possible benefit for those treated within 10 days.

Although he said it seems biologically plausible that treating patients earlier could be more effective, he added that “as well as being vigilant against overinterpretation, we need to ensure that hypotheses generated in efficacy-based trials, even in subgroups, are confirmed or refuted in subsequent adequately powered trials or meta-analyses.”

Noting that several other trials of remdesivir are underway, he concluded: “With each individual study at heightened risk of being incomplete, pooling data across possibly several underpowered but high-quality studies looks like our best way to obtain robust insights into what works, safely, and on whom.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, according to a preliminary data analysis from a U.S.-led randomized, controlled trial.

On the basis of as yet unpublished data, remdesivir “will be the standard of care” for patients with COVID-19, Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), said during a press conference at the White House April 29.

The randomized, placebo-controlled international trial was sponsored by NIAID, which is part of the National Institutes of Health, and enrolled 1,063 patients. It began on Feb. 21.

The interim results, discussed in the press conference and in a NIAID press release, show that time to recovery (i.e., being well enough for hospital discharge or to return to normal activity level) was 31% faster for patients who received remdesivir than for those who received placebo (P < .001).

The median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir, compared with 15 days for those who received placebo. Results also suggested a survival benefit, with a mortality rate of 8.0% for the group receiving remdesivir and 11.6% for the patients who received placebo (P = .059).

The study, known as the Adaptive COVID-19 Treatment Trial (ACTT), is the first clinical trial launched in the United States to evaluate an experimental treatment for COVID-19. It is being conducted at 68 sites – 47 in the United States and 21 in countries in Europe and Asia.

The data are being released after an interim review by the independent data safety monitoring board found significant benefit with the drug, Dr. Fauci said.

“The reason we are making the announcement now is something that people don’t fully appreciate: Whenever you have clear-cut evidence that a drug works, you have an ethical obligation to let the people in the placebo group know so they could have access,” he explained.

“When I was looking at the data with our team the other night, it was reminiscent of 34 years ago in 1986 when we were struggling for drugs for HIV,” said Dr. Fauci, who was a key figure in HIV/AIDS research. “We did the first randomized, placebo-controlled trial with AZT. It turned out to have an effect that was modest but that was not the endgame because, building on that, every year after, we did better and better.”

Similarly, new trials of drugs for COVID-19 will build on remdesivir, with other agents being added to block other pathways or viral enzymes, Dr. Fauci said.

The study will be submitted to a journal for peer review, he noted, but the New York Times is reporting that the Food and Drug Administration will approve remdesivir for emergency use soon.

In contrast to the positive results Dr. Fauci described from the NIAID-sponsored trial, a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of remdesivir among hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 in China was inconclusive.

The study, published online in The Lancet, showed some nonsignificant trends toward benefit but did not meet its primary endpoint.

The study was stopped early after 237 of the intended 453 patients were enrolled, owing to a lack of additional patients who met the eligibility criteria. The trial was thus underpowered.

Results showed that treatment with remdesivir did not significantly speed recovery or reduce deaths from COVID-19, but with regard to prespecified secondary outcomes, time to clinical improvement and duration of invasive mechanical ventilation were shorter among a subgroup of patients who began undergoing treatment with remdesivir within 10 days of showing symptoms, in comparison with patients who received standard care.

“To me, the studies reported here in The Lancet appear to be less promising than some statements released today from the NIH, so the situation is a bit puzzling to me,” said Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, who was not involved in the study. “I would need to look more closely at the data which NIH is looking at to understand the differences.”

Trial details

The published trial was conducted at 10 hospitals in Hubei, China. Enrollment criteria included being admitted to hospital with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection within 12 days of symptom onset, having oxygen saturation of 94% or less, and having radiologically confirmed pneumonia.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive intravenous remdesivir (200 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg on days 2–10 in single daily infusions) or placebo infusions for 10 days. Patients were permitted concomitant use of lopinavir-ritonavir, interferons, and corticosteroids.

The primary endpoint was time to clinical improvement to day 28, defined as the time (in days) from randomization to the point of a decline of two levels on a six-point ordinal scale of clinical status (on that scale, 1 indicated that the patient was discharged, and 6 indicated death) or to the patient’s being discharged alive from hospital, whichever came first.

The trial was stopped early because stringent public health measures used in Wuhan led to marked reductions in new patient presentations and because lack of available hospital beds resulted in most patients being enrolled later in the course of disease.

Between Feb. 6, 2020, and March 12, 2020, 237 patients were enrolled and were randomly assigned to receive either remdesivir (n = 158) or placebo (n = 79).

Results showed that use of remdesivir was not associated with a difference in time to clinical improvement (hazard ratio [HR], 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.87-1.75).

Although not statistically significant, time to clinical improvement was numerically faster for patients who received remdesivir than for those who received placebo among patients with symptom duration of 10 days or less (median, 18 days vs. 23 days; HR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.95-2.43).

The mortality rates were similar for the two groups (14% of patients who received remdesivir died vs. 13% of those who received placebo). There was no signal that viral load decreased differentially over time between the two groups.

Adverse events were reported in 66% of remdesivir recipients, vs. 64% of those who received placebo. Remdesivir was stopped early because of adverse events in 12% of patients; it was stopped early for 5% of those who received placebo.

The authors, led by Yeming Wang, MD, China-Japan Friendship Hospital, Beijing, noted that compared with a previous study of compassionate use of remdesivir, the population in the current study was less ill and was treated somewhat earlier in the disease course (median, 10 days vs. 12 days).

Because the study was terminated early, the researchers said they could not adequately assess whether earlier treatment with remdesivir might have provided clinical benefit.

“However, among patients who were treated within 10 days of symptom onset, remdesivir was not a significant factor but was associated with a numerical reduction of 5 days in median time to clinical improvement,” they stated.

They added that remdesivir was adequately tolerated and that no new safety concerns were identified.

In an accompanying comment in The Lancet, John David Norrie, MD, Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit, United Kingdom, pointed out that this study “has not shown a statistically significant finding that confirms a remdesivir treatment benefit of at least the minimally clinically important difference, nor has it ruled such a benefit out.”

Dr. Norrie was cautious about the fact that the subgroup analysis suggested possible benefit for those treated within 10 days.

Although he said it seems biologically plausible that treating patients earlier could be more effective, he added that “as well as being vigilant against overinterpretation, we need to ensure that hypotheses generated in efficacy-based trials, even in subgroups, are confirmed or refuted in subsequent adequately powered trials or meta-analyses.”

Noting that several other trials of remdesivir are underway, he concluded: “With each individual study at heightened risk of being incomplete, pooling data across possibly several underpowered but high-quality studies looks like our best way to obtain robust insights into what works, safely, and on whom.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Standing orders for vaccines may improve pediatric vaccination rates

The biggest barrier to using standing orders for childhood immunizations is concern that patients will receive the wrong vaccine, according to a survey of pediatricians published in Pediatrics.

The other top reasons pediatricians give for not using standing orders for vaccines are concerns that parents may want to talk to the doctor about the vaccine before their child gets it, and a belief that the doctor should be the one who personally recommends a vaccine for their patient.

But with severe drops in vaccination rates resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, standing orders may be a valuable tool for ensuring children get their vaccines on time, suggested lead author, Jessica Cataldi, MD, of the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

“As we work to bring more families back to their pediatrician’s office for well-child checks, standing orders are one process that can streamline the visit by saving providers time and increasing vaccine delivery,” she said in an interview. “We will also need use standing orders to support different ways to get children their immunizations during times of social distancing. This could take the form of drive-through immunization clinics or telehealth well-child checks that are paired with a quick immunization-only visit.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidance April 14 that emphasizes the need to prioritize immunization of children through 2-years-old.

Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, agreed that it’s essential children do not fall behind on the recommended schedule during the pandemic.

“It’s important not to have greater collateral damage from this COVID-19 pandemic by putting children at increased risk from other infections that are circulating, like measles and pertussis,” he said, noting that nearly 1,300 measles cases and more than 15,000 pertussis cases occurred in the United States in 2019.

It’s important “not to delay those primary vaccines because it’s hard to catch up,” he said in an interview

Although “standing orders” may go by other names in non–inpatient settings, the researchers defined them in their survey as “a written or verbal policy that persons other than a medical provider, such as a nurse or medical assistant, may consent and vaccinate a person without speaking with the physician or advanced care provider first.” Further, the “vaccine may be given before or after a physician encounter or in the absence of a physician encounter altogether.”

Research strongly suggests that standing orders for childhood vaccines are cost-effective and increase immunization rates, the authors noted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the federal National Vaccine Advisory Committee all recommend using standing orders to improve vaccination access and rates.

The authors sought to understand how many pediatricians use standing orders and what reasons stop them from doing so. During June-September 2017, they sent out 471 online and mail surveys to a nationally representative sample of AAP members who spent at least half their time in primary care.

The 372 pediatricians who completed the survey made up a response rate of 79%, with no differences in response based on age, sex, years in practice, practice setting, region or rural/urban location.

More than half the respondents (59%) used standing orders for childhood immunizations. Just over a third of respondents (36%) said they use standing orders for all routinely recommended vaccines, and 23% use them for some vaccines.

Among those who did not use standing orders, 68% cited the concern that patients would get the incorrect vaccine by mistake as a barrier to using them. That came as a surprise to Dr Offit, who would expect standing orders to reduce the likelihood of error.

“The standing order should make things a little more foolproof so that you’re less likely to make a mistake,” Dr Offit said.

No studies have shown that vaccine errors occur more often in clinics that use standing orders for immunizations, but the question merits continued monitoring, Dr Cataldi said.

“It is important for any clinic that is new to the use of standing orders to provide adequate education to providers and other staff about when and how to use standing orders, and to always leave room for staff to bring vaccination questions to the provider,” Dr Cataldi told this newspaper

Nearly as many physicians (62%) believed that families would want to speak to the doctor about a vaccine before getting it, and 57% of respondents who didn’t use standing orders believed they should be the one who recommends a vaccine to their patient’s parents.

All three of these reasons also ranked highest as barriers in responses from all respondents, including those who use standing orders. But those who didn’t use them were significantly more likely to cite these reasons (P less than .0001).

Since the survey occurred in 2017, however, it’s possible the pandemic and the rapid increase in telehealth as a result may influence perceptions moving forward.

“With provider concerns that standing orders remove physicians from the vaccination conversation, it may be that those conversations become less crucial as some families may start to value and accept immunizations more as a result of this pandemic,” Dr Cataldi said. “Or for families with vaccine questions, telehealth might support those conversations with a provider well.”

After adjusting for potential confounders, the only practice or physician factor significantly associated with not using standing orders for vaccines was physicians’ having a higher “physician responsibility score.” Doctors with these higher scores also were marginally more likely to make independent decisions about vaccines than counterparts working at practices where system-level decisions occur.

“Perhaps physicians who feel more personal responsibility about their role in vaccination are more likely to choose practice settings where they have more independent decision-making ability,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, knowing the level of decision-making about vaccines in the practice may influence the amount of personal responsibility that pediatricians feel about their role in vaccine delivery.”

Again, attitudes may have shifted since the coronavirus pandemic began. The biggest risk to children in terms of immunizations is not getting them, Dr Offit said.

“The parents are scared, and the doctors are scared,” he said. “They feel that going to a doctor’s office is going to a concentrated area where they’re more likely to pick up this virus.”

He’s expressed uncertainty about whether standing orders could play a role in alleviating that anxiety. But Dr Cataldi suggests it’s possible.

“I think standing orders will be important to increasing vaccination rates during a pandemic as they can be used to support delivery of vaccines through public health departments and through vaccine-only nurse visits,” she said.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Cataldi J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Apr;e20191855.

The biggest barrier to using standing orders for childhood immunizations is concern that patients will receive the wrong vaccine, according to a survey of pediatricians published in Pediatrics.

The other top reasons pediatricians give for not using standing orders for vaccines are concerns that parents may want to talk to the doctor about the vaccine before their child gets it, and a belief that the doctor should be the one who personally recommends a vaccine for their patient.

But with severe drops in vaccination rates resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, standing orders may be a valuable tool for ensuring children get their vaccines on time, suggested lead author, Jessica Cataldi, MD, of the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

“As we work to bring more families back to their pediatrician’s office for well-child checks, standing orders are one process that can streamline the visit by saving providers time and increasing vaccine delivery,” she said in an interview. “We will also need use standing orders to support different ways to get children their immunizations during times of social distancing. This could take the form of drive-through immunization clinics or telehealth well-child checks that are paired with a quick immunization-only visit.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidance April 14 that emphasizes the need to prioritize immunization of children through 2-years-old.

Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, agreed that it’s essential children do not fall behind on the recommended schedule during the pandemic.

“It’s important not to have greater collateral damage from this COVID-19 pandemic by putting children at increased risk from other infections that are circulating, like measles and pertussis,” he said, noting that nearly 1,300 measles cases and more than 15,000 pertussis cases occurred in the United States in 2019.

It’s important “not to delay those primary vaccines because it’s hard to catch up,” he said in an interview

Although “standing orders” may go by other names in non–inpatient settings, the researchers defined them in their survey as “a written or verbal policy that persons other than a medical provider, such as a nurse or medical assistant, may consent and vaccinate a person without speaking with the physician or advanced care provider first.” Further, the “vaccine may be given before or after a physician encounter or in the absence of a physician encounter altogether.”

Research strongly suggests that standing orders for childhood vaccines are cost-effective and increase immunization rates, the authors noted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the federal National Vaccine Advisory Committee all recommend using standing orders to improve vaccination access and rates.

The authors sought to understand how many pediatricians use standing orders and what reasons stop them from doing so. During June-September 2017, they sent out 471 online and mail surveys to a nationally representative sample of AAP members who spent at least half their time in primary care.

The 372 pediatricians who completed the survey made up a response rate of 79%, with no differences in response based on age, sex, years in practice, practice setting, region or rural/urban location.

More than half the respondents (59%) used standing orders for childhood immunizations. Just over a third of respondents (36%) said they use standing orders for all routinely recommended vaccines, and 23% use them for some vaccines.

Among those who did not use standing orders, 68% cited the concern that patients would get the incorrect vaccine by mistake as a barrier to using them. That came as a surprise to Dr Offit, who would expect standing orders to reduce the likelihood of error.

“The standing order should make things a little more foolproof so that you’re less likely to make a mistake,” Dr Offit said.

No studies have shown that vaccine errors occur more often in clinics that use standing orders for immunizations, but the question merits continued monitoring, Dr Cataldi said.

“It is important for any clinic that is new to the use of standing orders to provide adequate education to providers and other staff about when and how to use standing orders, and to always leave room for staff to bring vaccination questions to the provider,” Dr Cataldi told this newspaper

Nearly as many physicians (62%) believed that families would want to speak to the doctor about a vaccine before getting it, and 57% of respondents who didn’t use standing orders believed they should be the one who recommends a vaccine to their patient’s parents.

All three of these reasons also ranked highest as barriers in responses from all respondents, including those who use standing orders. But those who didn’t use them were significantly more likely to cite these reasons (P less than .0001).

Since the survey occurred in 2017, however, it’s possible the pandemic and the rapid increase in telehealth as a result may influence perceptions moving forward.

“With provider concerns that standing orders remove physicians from the vaccination conversation, it may be that those conversations become less crucial as some families may start to value and accept immunizations more as a result of this pandemic,” Dr Cataldi said. “Or for families with vaccine questions, telehealth might support those conversations with a provider well.”

After adjusting for potential confounders, the only practice or physician factor significantly associated with not using standing orders for vaccines was physicians’ having a higher “physician responsibility score.” Doctors with these higher scores also were marginally more likely to make independent decisions about vaccines than counterparts working at practices where system-level decisions occur.

“Perhaps physicians who feel more personal responsibility about their role in vaccination are more likely to choose practice settings where they have more independent decision-making ability,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, knowing the level of decision-making about vaccines in the practice may influence the amount of personal responsibility that pediatricians feel about their role in vaccine delivery.”

Again, attitudes may have shifted since the coronavirus pandemic began. The biggest risk to children in terms of immunizations is not getting them, Dr Offit said.

“The parents are scared, and the doctors are scared,” he said. “They feel that going to a doctor’s office is going to a concentrated area where they’re more likely to pick up this virus.”

He’s expressed uncertainty about whether standing orders could play a role in alleviating that anxiety. But Dr Cataldi suggests it’s possible.

“I think standing orders will be important to increasing vaccination rates during a pandemic as they can be used to support delivery of vaccines through public health departments and through vaccine-only nurse visits,” she said.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Cataldi J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Apr;e20191855.

The biggest barrier to using standing orders for childhood immunizations is concern that patients will receive the wrong vaccine, according to a survey of pediatricians published in Pediatrics.

The other top reasons pediatricians give for not using standing orders for vaccines are concerns that parents may want to talk to the doctor about the vaccine before their child gets it, and a belief that the doctor should be the one who personally recommends a vaccine for their patient.

But with severe drops in vaccination rates resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, standing orders may be a valuable tool for ensuring children get their vaccines on time, suggested lead author, Jessica Cataldi, MD, of the University of Colorado and Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

“As we work to bring more families back to their pediatrician’s office for well-child checks, standing orders are one process that can streamline the visit by saving providers time and increasing vaccine delivery,” she said in an interview. “We will also need use standing orders to support different ways to get children their immunizations during times of social distancing. This could take the form of drive-through immunization clinics or telehealth well-child checks that are paired with a quick immunization-only visit.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidance April 14 that emphasizes the need to prioritize immunization of children through 2-years-old.

Paul A. Offit, MD, director of the Vaccine Education Center and an attending physician in the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, agreed that it’s essential children do not fall behind on the recommended schedule during the pandemic.

“It’s important not to have greater collateral damage from this COVID-19 pandemic by putting children at increased risk from other infections that are circulating, like measles and pertussis,” he said, noting that nearly 1,300 measles cases and more than 15,000 pertussis cases occurred in the United States in 2019.

It’s important “not to delay those primary vaccines because it’s hard to catch up,” he said in an interview

Although “standing orders” may go by other names in non–inpatient settings, the researchers defined them in their survey as “a written or verbal policy that persons other than a medical provider, such as a nurse or medical assistant, may consent and vaccinate a person without speaking with the physician or advanced care provider first.” Further, the “vaccine may be given before or after a physician encounter or in the absence of a physician encounter altogether.”

Research strongly suggests that standing orders for childhood vaccines are cost-effective and increase immunization rates, the authors noted. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, its Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the federal National Vaccine Advisory Committee all recommend using standing orders to improve vaccination access and rates.

The authors sought to understand how many pediatricians use standing orders and what reasons stop them from doing so. During June-September 2017, they sent out 471 online and mail surveys to a nationally representative sample of AAP members who spent at least half their time in primary care.

The 372 pediatricians who completed the survey made up a response rate of 79%, with no differences in response based on age, sex, years in practice, practice setting, region or rural/urban location.

More than half the respondents (59%) used standing orders for childhood immunizations. Just over a third of respondents (36%) said they use standing orders for all routinely recommended vaccines, and 23% use them for some vaccines.

Among those who did not use standing orders, 68% cited the concern that patients would get the incorrect vaccine by mistake as a barrier to using them. That came as a surprise to Dr Offit, who would expect standing orders to reduce the likelihood of error.

“The standing order should make things a little more foolproof so that you’re less likely to make a mistake,” Dr Offit said.

No studies have shown that vaccine errors occur more often in clinics that use standing orders for immunizations, but the question merits continued monitoring, Dr Cataldi said.

“It is important for any clinic that is new to the use of standing orders to provide adequate education to providers and other staff about when and how to use standing orders, and to always leave room for staff to bring vaccination questions to the provider,” Dr Cataldi told this newspaper

Nearly as many physicians (62%) believed that families would want to speak to the doctor about a vaccine before getting it, and 57% of respondents who didn’t use standing orders believed they should be the one who recommends a vaccine to their patient’s parents.

All three of these reasons also ranked highest as barriers in responses from all respondents, including those who use standing orders. But those who didn’t use them were significantly more likely to cite these reasons (P less than .0001).

Since the survey occurred in 2017, however, it’s possible the pandemic and the rapid increase in telehealth as a result may influence perceptions moving forward.

“With provider concerns that standing orders remove physicians from the vaccination conversation, it may be that those conversations become less crucial as some families may start to value and accept immunizations more as a result of this pandemic,” Dr Cataldi said. “Or for families with vaccine questions, telehealth might support those conversations with a provider well.”

After adjusting for potential confounders, the only practice or physician factor significantly associated with not using standing orders for vaccines was physicians’ having a higher “physician responsibility score.” Doctors with these higher scores also were marginally more likely to make independent decisions about vaccines than counterparts working at practices where system-level decisions occur.

“Perhaps physicians who feel more personal responsibility about their role in vaccination are more likely to choose practice settings where they have more independent decision-making ability,” the authors wrote. “Alternatively, knowing the level of decision-making about vaccines in the practice may influence the amount of personal responsibility that pediatricians feel about their role in vaccine delivery.”

Again, attitudes may have shifted since the coronavirus pandemic began. The biggest risk to children in terms of immunizations is not getting them, Dr Offit said.

“The parents are scared, and the doctors are scared,” he said. “They feel that going to a doctor’s office is going to a concentrated area where they’re more likely to pick up this virus.”

He’s expressed uncertainty about whether standing orders could play a role in alleviating that anxiety. But Dr Cataldi suggests it’s possible.

“I think standing orders will be important to increasing vaccination rates during a pandemic as they can be used to support delivery of vaccines through public health departments and through vaccine-only nurse visits,” she said.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Cataldi J et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Apr;e20191855.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Survey: Hydroxychloroquine use fairly common in COVID-19

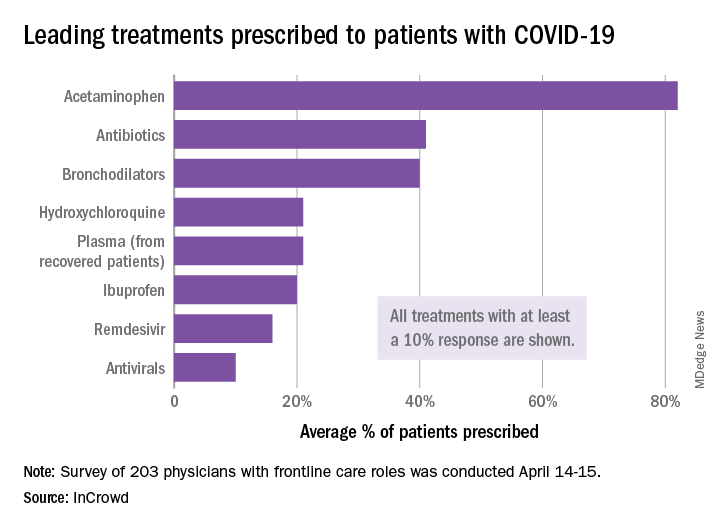

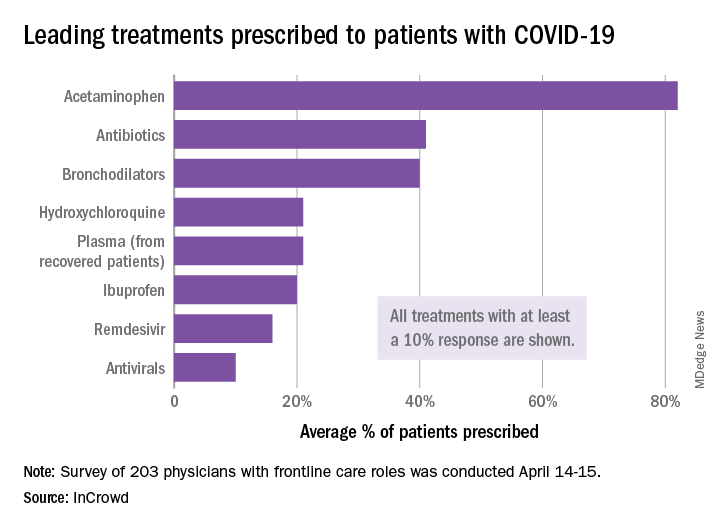

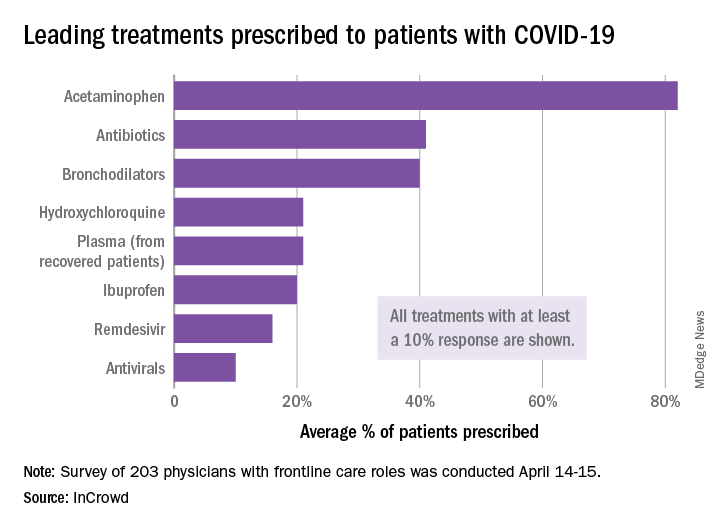

One of five physicians in front-line treatment roles has prescribed hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, according to a new survey from health care market research company InCrowd.

The most common treatments were acetaminophen, prescribed to 82% of patients, antibiotics (41%), and bronchodilators (40%), InCrowd said after surveying 203 primary care physicians, pediatricians, and emergency medicine or critical care physicians who are treating at least 20 patients with flulike symptoms.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine outside of hospitals and clinical trials.

The InCrowd survey, which took place April 14-15 and is the fourth in a series investigating COVID-19’s impact on physicians, showed that access to testing was up to 82% in mid-April, compared with 67% in March and 20% in late February. The April respondents also were twice as likely (59% vs. 24% in March) to say that their facilities were prepared to treat patients, InCrowd reported.

“U.S. physicians report sluggish optimism around preparedness, safety, and institutional efforts, while many worry about the future, including a second outbreak and job security,” the company said in a separate written statement.

The average estimate for a return to normal was just over 6 months among respondents, and only 28% believed that their facility was prepared for a second outbreak later in the year, InCrowd noted.

On a personal level, 45% of the respondents were concerned about the safety of their job. An emergency/critical care physician from Tennessee said, “We’ve been cutting back on staff due to overall revenue reductions, but have increased acuity and complexity which requires more staffing. This puts even more of a burden on those of us still here.”

Support for institutional responses to slow the pandemic was strongest for state governments, which gained approval from 54% of front-line physicians, up from 33% in March. Actions taken by the federal government were supported by 21% of respondents, compared with 38% for the World Health Organization and 46% for governments outside the United States, InCrowd reported.

Suggestions for further actions by state and local authorities included this comment from an emergency/critical care physician in Florida: “Continued, broad and properly enforced stay at home and social distancing measures MUST remain in place to keep citizens and healthcare workers safe, and the latter alive and in adequate supply.”

One of five physicians in front-line treatment roles has prescribed hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, according to a new survey from health care market research company InCrowd.

The most common treatments were acetaminophen, prescribed to 82% of patients, antibiotics (41%), and bronchodilators (40%), InCrowd said after surveying 203 primary care physicians, pediatricians, and emergency medicine or critical care physicians who are treating at least 20 patients with flulike symptoms.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine outside of hospitals and clinical trials.

The InCrowd survey, which took place April 14-15 and is the fourth in a series investigating COVID-19’s impact on physicians, showed that access to testing was up to 82% in mid-April, compared with 67% in March and 20% in late February. The April respondents also were twice as likely (59% vs. 24% in March) to say that their facilities were prepared to treat patients, InCrowd reported.

“U.S. physicians report sluggish optimism around preparedness, safety, and institutional efforts, while many worry about the future, including a second outbreak and job security,” the company said in a separate written statement.

The average estimate for a return to normal was just over 6 months among respondents, and only 28% believed that their facility was prepared for a second outbreak later in the year, InCrowd noted.

On a personal level, 45% of the respondents were concerned about the safety of their job. An emergency/critical care physician from Tennessee said, “We’ve been cutting back on staff due to overall revenue reductions, but have increased acuity and complexity which requires more staffing. This puts even more of a burden on those of us still here.”

Support for institutional responses to slow the pandemic was strongest for state governments, which gained approval from 54% of front-line physicians, up from 33% in March. Actions taken by the federal government were supported by 21% of respondents, compared with 38% for the World Health Organization and 46% for governments outside the United States, InCrowd reported.

Suggestions for further actions by state and local authorities included this comment from an emergency/critical care physician in Florida: “Continued, broad and properly enforced stay at home and social distancing measures MUST remain in place to keep citizens and healthcare workers safe, and the latter alive and in adequate supply.”

One of five physicians in front-line treatment roles has prescribed hydroxychloroquine for COVID-19, according to a new survey from health care market research company InCrowd.

The most common treatments were acetaminophen, prescribed to 82% of patients, antibiotics (41%), and bronchodilators (40%), InCrowd said after surveying 203 primary care physicians, pediatricians, and emergency medicine or critical care physicians who are treating at least 20 patients with flulike symptoms.

On April 24, the Food and Drug Administration warned against the use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine outside of hospitals and clinical trials.

The InCrowd survey, which took place April 14-15 and is the fourth in a series investigating COVID-19’s impact on physicians, showed that access to testing was up to 82% in mid-April, compared with 67% in March and 20% in late February. The April respondents also were twice as likely (59% vs. 24% in March) to say that their facilities were prepared to treat patients, InCrowd reported.

“U.S. physicians report sluggish optimism around preparedness, safety, and institutional efforts, while many worry about the future, including a second outbreak and job security,” the company said in a separate written statement.

The average estimate for a return to normal was just over 6 months among respondents, and only 28% believed that their facility was prepared for a second outbreak later in the year, InCrowd noted.

On a personal level, 45% of the respondents were concerned about the safety of their job. An emergency/critical care physician from Tennessee said, “We’ve been cutting back on staff due to overall revenue reductions, but have increased acuity and complexity which requires more staffing. This puts even more of a burden on those of us still here.”

Support for institutional responses to slow the pandemic was strongest for state governments, which gained approval from 54% of front-line physicians, up from 33% in March. Actions taken by the federal government were supported by 21% of respondents, compared with 38% for the World Health Organization and 46% for governments outside the United States, InCrowd reported.

Suggestions for further actions by state and local authorities included this comment from an emergency/critical care physician in Florida: “Continued, broad and properly enforced stay at home and social distancing measures MUST remain in place to keep citizens and healthcare workers safe, and the latter alive and in adequate supply.”

COVID-19: Calls to NYC crisis hotline soar

Calls to a mental health crisis hotline in New York City have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has closed schools and businesses, put millions out of work, and ushered in stay-at-home orders.

ensuring that care is available when and where needed during a crisis, whether that be an individual crisis, a local community crisis, or a national mental health crisis like we are facing right now,” said Kimberly Williams, president and CEO of Vibrant Emotional Health.

Vibrant Emotional Health, formerly the Mental Health Association of New York City, provides crisis line services across the United States in partnership with local and federal governments and corporations. NYC Well is one of them.

Ms. Williams and two of her colleagues spoke about crisis hotlines April 25 during the American Psychiatric Association’s Virtual Spring Highlights Meeting.

Rapid crisis intervention

Crisis hotlines provide “rapid crisis intervention, delivering help immediately from trained crisis counselors who respond to unique needs, actively engage in collaborative problem solving, and assess risk for suicide,” Ms. Williams said.

They have a proven track record, she noted. Research shows that they are able to decrease emotional distress and reduce suicidality in crisis situations.

Kelly Clarke, program director of NYC Well, noted that inbound call volume has increased roughly 50% since the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Callers to NYC Well most commonly report mood/anxiety concerns, stressful life events, and interpersonal problems. “Many people are reaching out to seek support in how to manage their own emotional well-being in light of the pandemic and the restrictions put in place,” said Ms. Clarke.

Multilingual peer support specialists and counselors with NYC Well provide free, confidential support by talk, text, or chat 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, 365 days a year. The service also provides mobile crisis teams and follow-up services. NYC Well has set up a landing page of resources specifically geared toward COVID-19.

How to cope with the rapid growth and at the same time ensure high quality of services are two key challenges for NYC Well, Ms. Clarke said.

“Absolutely essential” service

For John Draper, PhD, the experience early in his career of working on a mobile mental health crisis team in Brooklyn “changed his life.”

First, it showed him that, for people who are severely psychiatrically ill, “care has to come to them,” said Dr. Draper, executive vice president of national networks for Vibrant Emotional Health.

“So many of the people we were seeing were too depressed to get out of bed, much less get to a clinic, and I realized our system was not set up to serve its customers. It was like putting a spinal cord injury clinic at the top of a stairs,” he said.

Crisis hotlines are “absolutely essential.” Their value for communities and individuals “can’t be overestimated,” said Dr. Draper.

This was revealed after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and now with COVID-19, said Dr. Draper. He noted, that following the attacks of 9/11, a federal report referred to crisis hotlines as “the single most important asset in the response.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Calls to a mental health crisis hotline in New York City have soared during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has closed schools and businesses, put millions out of work, and ushered in stay-at-home orders.

ensuring that care is available when and where needed during a crisis, whether that be an individual crisis, a local community crisis, or a national mental health crisis like we are facing right now,” said Kimberly Williams, president and CEO of Vibrant Emotional Health.