User login

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

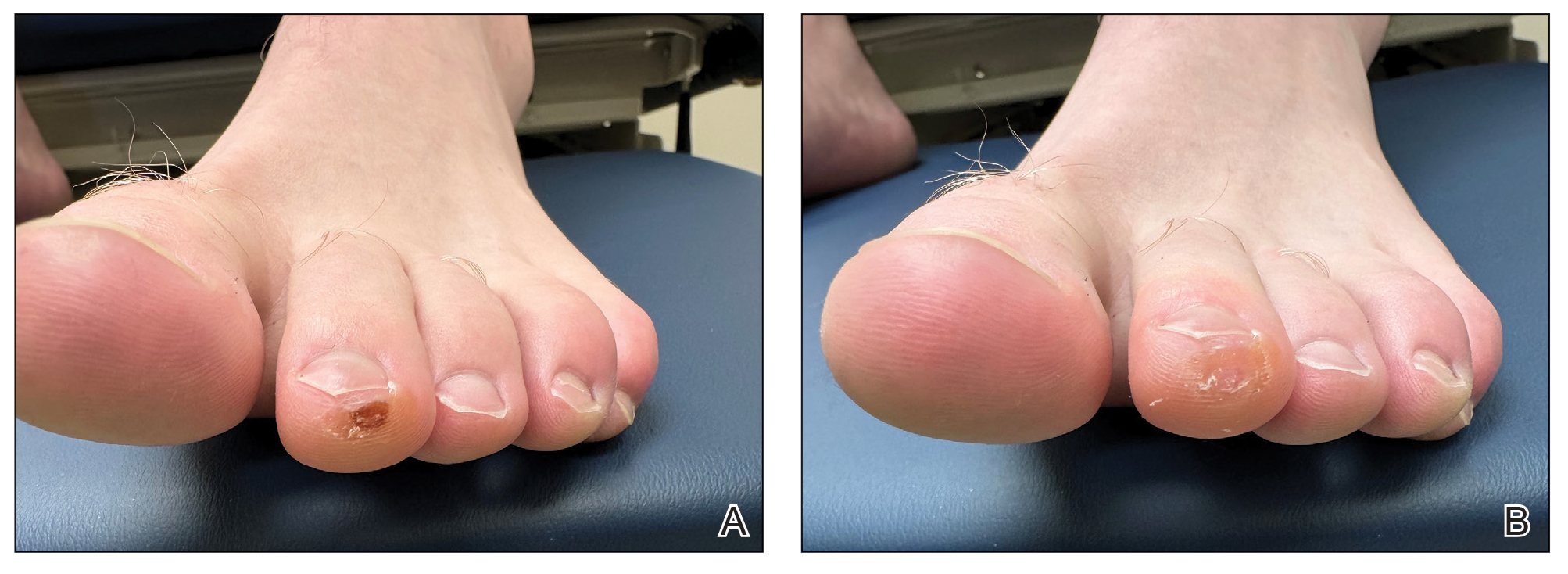

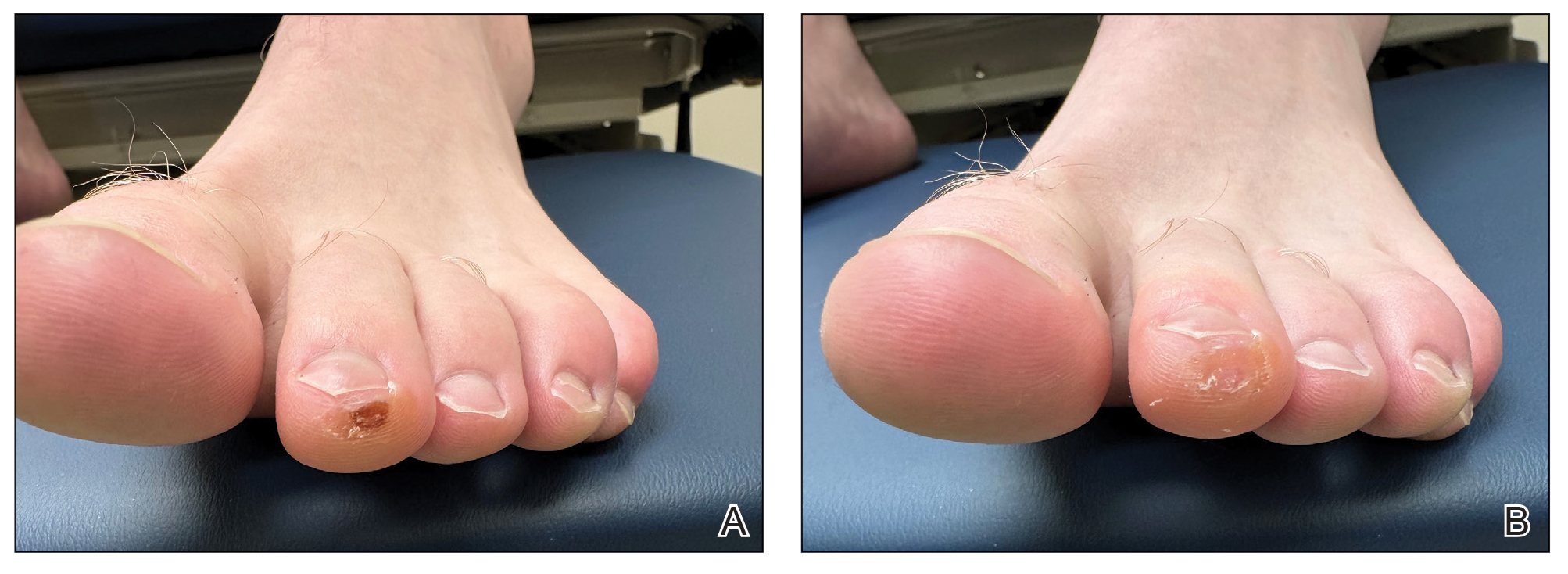

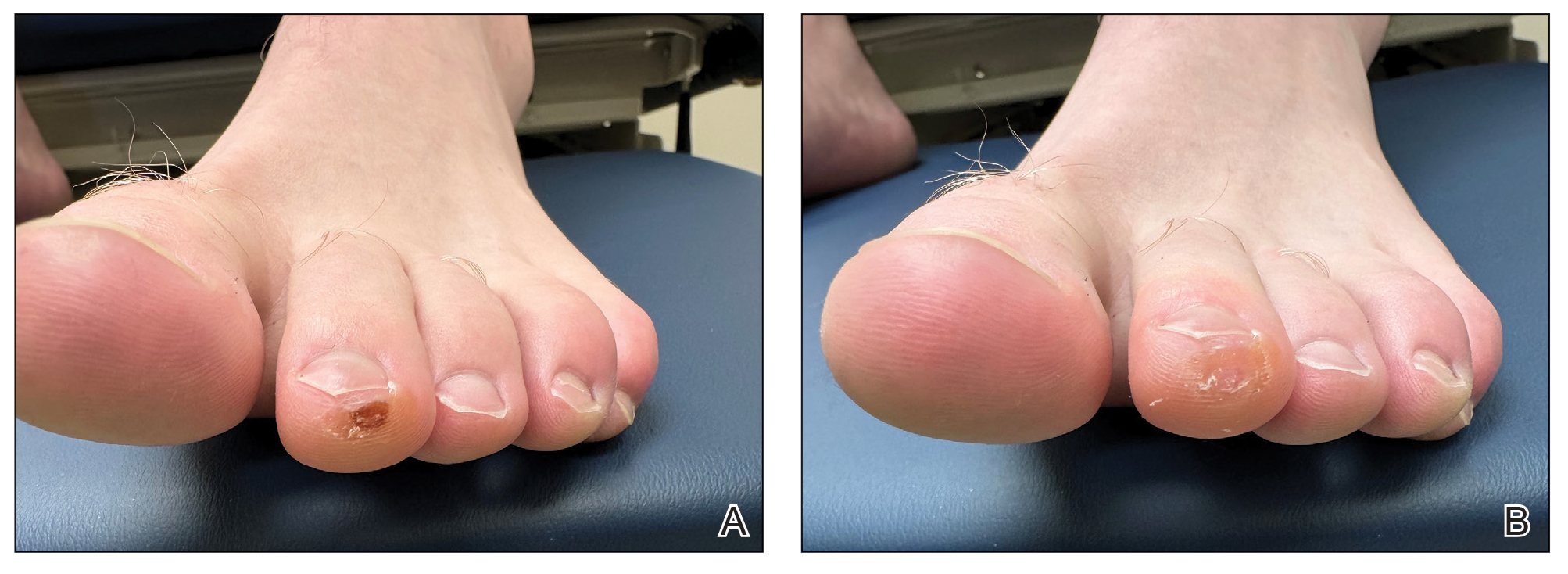

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

Practice Gap

Brown macules on the feet can pose diagnostic challenges, often raising suspicion of acral melanoma. Talon noir, which is benign and self-resolving, is characterized by dark patches on the skin of the feet due to hemorrhage within the stratum corneum and commonly is observed in athletes who sustain repetitive foot trauma. In one study, nearly 50% (9/20) of talon noir cases initially were misdiagnosed as acral melanoma or melanocytic nevi.1 Accurate identification of talon noir is essential to prevent unnecessary interventions or delayed treatment of malignant lesions. Here, we describe a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique for talon noir using a disposable curette to potentially avoid more invasive procedures.

The Technique

A 34-year-old man presented to the dermatology department with a new brown macule on the second toe. The lesion had been present and stable for more than 4 months, showing no changes in shape or color. The patient reported that he was a frequent runner but did not recall any trauma to the toe, and he denied any associated pain, pruritus, or bleeding. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm dark-brown macule on the hyponychium of the left second toe, with numerous petechiae noted on dermoscopic examination. The findings were consistent with talon noir.

Given the clinical suspicion of talon noir, we used a 5-mm disposable curette to gently pare the superficial epidermis. The superficial curettage effectively removed the lesion, leaving behind a healthy epidermis with no pinpoint bleeding, which confirmed the diagnosis of talon noir (Figure). Pathologic changes from acral melanoma reside deeper than talon noir and consequently cannot be effectively removed by superficial curettage alone. Curettage acts as a curative technique for talon noir, but also as a low-risk, cost-effective, and time-efficient diagnostic technique to rule out insidious diagnoses, including acral melanoma.2 A follow-up examination performed several weeks later showed no pigmentation or recurrence of the lesion in our patient, further supporting the diagnosis of talon noir.

Practice Implications

Talon noir refers to localized accumulation of blood within the epidermis due to repetitive trauma, pressure, and shearing forces on the skin that results in pigmented macules.3-5 Repetitive trauma damages the microvasculature in areas of the skin with minimal subcutaneous adipose tissue.6 Talon noir also is known as subcorneal hematoma, intracorneal hematoma, black heel, hyperkeratosis hemorrhagica, and basketball heel.1,3 First described by Crissey and Peachey3 in 1961 as calcaneal petechiae, the condition was identified in basketball players with well-circumscribed, deep-red lesions on the posterior lateral heels, located between the Achilles tendon insertion and calcaneal fat pad.3 Subsequent reports have documented talon noir in athletes from a range of sports such as tennis and football, whose activities involve rapid directional changes and shearing forces on the feet.6 Similar lesions, termed tache noir, have been observed on the hands of athletes including gymnasts, weightlifters, golfers, and climbers due to repetitive hand trauma.6 Gross examination reveals blood collecting in the thickened stratum corneum.5

The cutaneous manifestations of talon noir can mimic acral melanoma, highlighting the need for dermatologists to understand its clinical, dermoscopic, and microscopic features. Poor patient recall can complicate diagnosis; for instance, in one study only 20% (4/20) of patients remembered the inciting trauma that caused the subcorneal hematomas.1 Balancing vigilance for melanoma with recognition of more benign conditions such as talon noir—particularly in younger active populations—is essential to minimize patient anxiety and avoid invasive procedures.

Further investigation is warranted in lesions that persist without obvious cause or in those that demonstrate concerning features such as extensive growth. One case of talon noir in a patient with diabetes required an excisional biopsy due to its atypical progression over 1 year with considerable hyperpigmentation and friability.7 Additional investigation such as dermoscopy may be required with paring of the skin to establish a diagnosis.1 Using a curette to pare the thickened stratum corneum, which has no nerve endings, does not require anesthetics.8 In talon noir, paring completely removes the lesion, leaving behind unaffected skin, while melanomas would retain their pigmentation due to melanin in the basal layer.2

Talon noir is a benign condition frequently misdiagnosed due to its resemblance to more serious pathologies such as melanoma. Awareness of its clinical and dermoscopic features can promote cost-effective care while reducing unnecessary procedures. Diagnostic paring of the skin with a curette offers a simple and reliable means of distinguishing talon noir from acral melanoma and other potential conditions.

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

- Elmas OF, Akdeniz N. Subcorneal hematoma as an imitator of acral melanoma: dermoscopic diagnosis. North Clin Istanb. 2019;7:56-59. doi:10.14744/nci.2019.65481

- Googe AB, Schulmeier JS, Jackson AR, et al. Talon noir: paring can eliminate the need for a biopsy. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:730-731. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132996

- Crissey JT, Peachey JC. Calcaneal petechiae. Arch Dermatol. 1961;83:501. doi:10.1001/archderm.1961.01580090151017

- Martin SB, Lucas JK, Posa M, et al. Talon noir in a young baseball player: a case report. J Pediatr Health Care. 2021;35:235-238. doi:10.1016 /j.pedhc.2020.10.009

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Duncan KO, et al. Dermatology Essentials. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2022.

- Emer J, Sivek R, Marciniak B. Sports dermatology: part 1 of 2 traumatic or mechanical injuries, inflammatory conditions, and exacerbations of pre-existing conditions. J Clin Aesthetic Dermatol. 2015; 8:31-43.

- Choudhury S, Mandal A. Talon noir: a case report and literature review. Cureus. 2023;15:E35905. doi:10.7759/cureus.35905

- Oberdorfer KL, Farshchian M, Moossavi M. Paring of skin for superficially lodged foreign body removal. Cureus. 2023;15:E42396. doi:10.7759/cureus.42396

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Using Superficial Curettage to Diagnose Talon Noir

Immunotherapy Reduces Skin Cancer Precursors

TOPLINE:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) show promise for field cancerization, based on their ability to reduce actinic keratoses (AKs) in a new study.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective cohort study included 23 immunocompetent participants (26.1% women; mean age, 69.7 years) from Australia who received ICIs for any cancer between April 2022 and November 2023.

- The most frequently prescribed ICI regimen was a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab (34.8%), followed by nivolumab monotherapy (26.1%) and cemiplimab (21.7%) or pembrolizumab (17.4%) monotherapy.

- More than half of the patients received ICI therapy for skin cancer (melanoma, 30.4%; cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, 26.1%); 34.8% had lung cancer; two had other carcinomas.

- The primary outcome was the number of AKs at 12 months after starting ICI therapy; the secondary outcome was the number of keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) excised 12 months before and after ICI therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 12 months, one patient had complete resolution from AK, and the mean number of AKs significantly decreased from 47.2 at baseline to 14.3 (P < .001).

- Younger patients (66.7% vs 33.3%; P = .007) and those with a history of blistering sunburn (100% vs 0; P = .005) were more likely to experience ≥ 65% reduction in AK count.

- KC incidence in the year before ICI therapy vs the year after initiation dropped from 42 to 17 cases, respectively, and the number of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas decreased from 16 to 5.

- Adverse events occurred in 11 participants (47.8%), with maculopapular rash or pruritus the most common.

IN PRACTICE:

“This pilot cohort study highlights the potential association of ICI therapy, originally used in cancer treatment, with significant reduction of clinical AKs,” the authors wrote. These findings, they said, “underscore ICIs’ potential as a novel approach to mitigating field cancerization in high-risk populations.”

SOURCE:

Charlotte Cox, MD, MPhil, MPHTM, BMSt, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included interrater reliability issues in AK counting. Not all patients completed the follow-up period, and observations about changes after stopping ICI therapy were limited. Surveillance bias could be present in KC reporting.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by grants from the Metro South Health SERTA project and by the French Society of Dermatology, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, the Collège des Enseignants en Dermatologie de France, and the European Association of Dermatology and Venereology. Cox received personal fees from the University of Queensland scholarship funds during this work. Some authors reported receiving personal fees and support from pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) show promise for field cancerization, based on their ability to reduce actinic keratoses (AKs) in a new study.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective cohort study included 23 immunocompetent participants (26.1% women; mean age, 69.7 years) from Australia who received ICIs for any cancer between April 2022 and November 2023.

- The most frequently prescribed ICI regimen was a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab (34.8%), followed by nivolumab monotherapy (26.1%) and cemiplimab (21.7%) or pembrolizumab (17.4%) monotherapy.

- More than half of the patients received ICI therapy for skin cancer (melanoma, 30.4%; cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, 26.1%); 34.8% had lung cancer; two had other carcinomas.

- The primary outcome was the number of AKs at 12 months after starting ICI therapy; the secondary outcome was the number of keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) excised 12 months before and after ICI therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 12 months, one patient had complete resolution from AK, and the mean number of AKs significantly decreased from 47.2 at baseline to 14.3 (P < .001).

- Younger patients (66.7% vs 33.3%; P = .007) and those with a history of blistering sunburn (100% vs 0; P = .005) were more likely to experience ≥ 65% reduction in AK count.

- KC incidence in the year before ICI therapy vs the year after initiation dropped from 42 to 17 cases, respectively, and the number of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas decreased from 16 to 5.

- Adverse events occurred in 11 participants (47.8%), with maculopapular rash or pruritus the most common.

IN PRACTICE:

“This pilot cohort study highlights the potential association of ICI therapy, originally used in cancer treatment, with significant reduction of clinical AKs,” the authors wrote. These findings, they said, “underscore ICIs’ potential as a novel approach to mitigating field cancerization in high-risk populations.”

SOURCE:

Charlotte Cox, MD, MPhil, MPHTM, BMSt, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included interrater reliability issues in AK counting. Not all patients completed the follow-up period, and observations about changes after stopping ICI therapy were limited. Surveillance bias could be present in KC reporting.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by grants from the Metro South Health SERTA project and by the French Society of Dermatology, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, the Collège des Enseignants en Dermatologie de France, and the European Association of Dermatology and Venereology. Cox received personal fees from the University of Queensland scholarship funds during this work. Some authors reported receiving personal fees and support from pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) show promise for field cancerization, based on their ability to reduce actinic keratoses (AKs) in a new study.

METHODOLOGY:

- This prospective cohort study included 23 immunocompetent participants (26.1% women; mean age, 69.7 years) from Australia who received ICIs for any cancer between April 2022 and November 2023.

- The most frequently prescribed ICI regimen was a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab (34.8%), followed by nivolumab monotherapy (26.1%) and cemiplimab (21.7%) or pembrolizumab (17.4%) monotherapy.

- More than half of the patients received ICI therapy for skin cancer (melanoma, 30.4%; cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, 26.1%); 34.8% had lung cancer; two had other carcinomas.

- The primary outcome was the number of AKs at 12 months after starting ICI therapy; the secondary outcome was the number of keratinocyte carcinomas (KCs) excised 12 months before and after ICI therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- At 12 months, one patient had complete resolution from AK, and the mean number of AKs significantly decreased from 47.2 at baseline to 14.3 (P < .001).

- Younger patients (66.7% vs 33.3%; P = .007) and those with a history of blistering sunburn (100% vs 0; P = .005) were more likely to experience ≥ 65% reduction in AK count.

- KC incidence in the year before ICI therapy vs the year after initiation dropped from 42 to 17 cases, respectively, and the number of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas decreased from 16 to 5.

- Adverse events occurred in 11 participants (47.8%), with maculopapular rash or pruritus the most common.

IN PRACTICE:

“This pilot cohort study highlights the potential association of ICI therapy, originally used in cancer treatment, with significant reduction of clinical AKs,” the authors wrote. These findings, they said, “underscore ICIs’ potential as a novel approach to mitigating field cancerization in high-risk populations.”

SOURCE:

Charlotte Cox, MD, MPhil, MPHTM, BMSt, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, led the study, which was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included interrater reliability issues in AK counting. Not all patients completed the follow-up period, and observations about changes after stopping ICI therapy were limited. Surveillance bias could be present in KC reporting.

DISCLOSURES:

This work was supported by grants from the Metro South Health SERTA project and by the French Society of Dermatology, La Ligue Contre le Cancer, the Collège des Enseignants en Dermatologie de France, and the European Association of Dermatology and Venereology. Cox received personal fees from the University of Queensland scholarship funds during this work. Some authors reported receiving personal fees and support from pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma Less Common, With higher Mortality Than Melanoma

TOPLINE:

that also reported that male gender, older age, and exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) are significant risk factors.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers identified 19,444 MCC cases and 646,619 melanoma cases diagnosed between 2000 and 2021 using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.

- Ambient UVR exposure data were obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s total ozone mapping spectrometer database.

- Risk factors and cancer-specific mortality rates were evaluated for both cancers.

TAKEAWAY:

- Incidence rates per 100,000 person-years of MCC and melanoma were 0.8 and 27.3, respectively.

- Men (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.72 for MCC and 1.23 for melanoma), older age groups (IRR: 2.69 for MCC and 1.62 for melanoma among those 70-79 years; and 5.68 for MCC and 2.26 for melanoma among those 80 years or older) showed higher incidences of MCC and melanoma. Non-Hispanic White individuals were at higher risk for MCC and melanoma than other racial/ethnic groups.

- Exposure to UVR was associated with higher incidences of melanoma (IRR, 1.24-1.49) and MCC (IRR, 1.15-1.20) in non-Hispanic White individuals, particularly on the head and neck. These associations were unclear among racial/ethnic groups.

- Individuals with MCC had a higher risk for cancer-specific mortality than those with melanoma (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.33; 95% CI, 2.26-2.42). Cancer-specific survival for both cancers improved for cases diagnosed during 2012-2021 vs 2004-2011 (MCC: HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.78-0.89; melanoma: HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.74-0.76).

IN PRACTICE:

“MCC and melanoma are aggressive skin cancers with similar risk factors including male sex, older age, and UV radiation exposure. Clinicians should be alert to diagnosis of these cancers to allow for prompt treatment,” the authors wrote, adding: “It is encouraging that survival for both cancers has increased in recent years, with the largest gains in survival seen in distant stage melanoma, coinciding with the approval of BRAF and PD-1 inhibitors used for distant stage disease,” although mortality for advanced stage tumors “continues to be very high.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jacob T. Tribble, BA, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland. It was published online on January 5 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study relied on SEER’s general staging system rather than the American Joint Committee on Cancer standard, and UVR exposure estimates did not account for individual sun protection behaviors or prior residential history. Race and ethnicity served as a proxy for UVR sensitivity, which may introduce misclassification bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Dental Research, and the Colgate-Palmolive Company. The authors reported no conflict of interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

that also reported that male gender, older age, and exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) are significant risk factors.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers identified 19,444 MCC cases and 646,619 melanoma cases diagnosed between 2000 and 2021 using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.

- Ambient UVR exposure data were obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s total ozone mapping spectrometer database.

- Risk factors and cancer-specific mortality rates were evaluated for both cancers.

TAKEAWAY:

- Incidence rates per 100,000 person-years of MCC and melanoma were 0.8 and 27.3, respectively.

- Men (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.72 for MCC and 1.23 for melanoma), older age groups (IRR: 2.69 for MCC and 1.62 for melanoma among those 70-79 years; and 5.68 for MCC and 2.26 for melanoma among those 80 years or older) showed higher incidences of MCC and melanoma. Non-Hispanic White individuals were at higher risk for MCC and melanoma than other racial/ethnic groups.

- Exposure to UVR was associated with higher incidences of melanoma (IRR, 1.24-1.49) and MCC (IRR, 1.15-1.20) in non-Hispanic White individuals, particularly on the head and neck. These associations were unclear among racial/ethnic groups.

- Individuals with MCC had a higher risk for cancer-specific mortality than those with melanoma (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.33; 95% CI, 2.26-2.42). Cancer-specific survival for both cancers improved for cases diagnosed during 2012-2021 vs 2004-2011 (MCC: HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.78-0.89; melanoma: HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.74-0.76).

IN PRACTICE:

“MCC and melanoma are aggressive skin cancers with similar risk factors including male sex, older age, and UV radiation exposure. Clinicians should be alert to diagnosis of these cancers to allow for prompt treatment,” the authors wrote, adding: “It is encouraging that survival for both cancers has increased in recent years, with the largest gains in survival seen in distant stage melanoma, coinciding with the approval of BRAF and PD-1 inhibitors used for distant stage disease,” although mortality for advanced stage tumors “continues to be very high.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jacob T. Tribble, BA, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland. It was published online on January 5 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study relied on SEER’s general staging system rather than the American Joint Committee on Cancer standard, and UVR exposure estimates did not account for individual sun protection behaviors or prior residential history. Race and ethnicity served as a proxy for UVR sensitivity, which may introduce misclassification bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Dental Research, and the Colgate-Palmolive Company. The authors reported no conflict of interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

that also reported that male gender, older age, and exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) are significant risk factors.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers identified 19,444 MCC cases and 646,619 melanoma cases diagnosed between 2000 and 2021 using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program.

- Ambient UVR exposure data were obtained from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s total ozone mapping spectrometer database.

- Risk factors and cancer-specific mortality rates were evaluated for both cancers.

TAKEAWAY:

- Incidence rates per 100,000 person-years of MCC and melanoma were 0.8 and 27.3, respectively.

- Men (adjusted incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.72 for MCC and 1.23 for melanoma), older age groups (IRR: 2.69 for MCC and 1.62 for melanoma among those 70-79 years; and 5.68 for MCC and 2.26 for melanoma among those 80 years or older) showed higher incidences of MCC and melanoma. Non-Hispanic White individuals were at higher risk for MCC and melanoma than other racial/ethnic groups.

- Exposure to UVR was associated with higher incidences of melanoma (IRR, 1.24-1.49) and MCC (IRR, 1.15-1.20) in non-Hispanic White individuals, particularly on the head and neck. These associations were unclear among racial/ethnic groups.

- Individuals with MCC had a higher risk for cancer-specific mortality than those with melanoma (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 2.33; 95% CI, 2.26-2.42). Cancer-specific survival for both cancers improved for cases diagnosed during 2012-2021 vs 2004-2011 (MCC: HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.78-0.89; melanoma: HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.74-0.76).

IN PRACTICE:

“MCC and melanoma are aggressive skin cancers with similar risk factors including male sex, older age, and UV radiation exposure. Clinicians should be alert to diagnosis of these cancers to allow for prompt treatment,” the authors wrote, adding: “It is encouraging that survival for both cancers has increased in recent years, with the largest gains in survival seen in distant stage melanoma, coinciding with the approval of BRAF and PD-1 inhibitors used for distant stage disease,” although mortality for advanced stage tumors “continues to be very high.”

SOURCE:

The study was led by Jacob T. Tribble, BA, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, Maryland. It was published online on January 5 in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

The study relied on SEER’s general staging system rather than the American Joint Committee on Cancer standard, and UVR exposure estimates did not account for individual sun protection behaviors or prior residential history. Race and ethnicity served as a proxy for UVR sensitivity, which may introduce misclassification bias.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the American Association for Dental Research, and the Colgate-Palmolive Company. The authors reported no conflict of interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including artificial intelligence, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MRI-Invisible Prostate Lesions: Are They Dangerous?

MRI-invisible prostate lesions. It sounds like the stuff of science fiction and fantasy, a creation from the minds of H.G. Wells, who wrote The Invisible Man, or J.K. Rowling, who authored the Harry Potter series.

But MRI-invisible prostate lesions are real. And what these lesions may, or may not, indicate is the subject of intense debate.

MRI plays an increasingly important role in detecting and diagnosing prostate cancer, staging prostate cancer as well as monitoring disease progression. However, on occasion, a puzzling phenomenon arises. Certain prostate lesions that appear when pathologists examine biopsied tissue samples under a microscope are not visible on MRI. The prostate tissue will, instead, appear normal to a radiologist’s eye.

Some experts believe these MRI-invisible lesions are nothing to worry about.

If the clinician can’t see the cancer on MRI, then it simply isn’t a threat, according to Mark Emberton, MD, a pioneer in prostate MRIs and director of interventional oncology at University College London, England.

Laurence Klotz, MD, of the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, agreed, noting that “invisible cancers are clinically insignificant and don’t require systematic biopsies.”

Emberton and Klotz compared MRI-invisible lesions to grade group 1 prostate cancer (Gleason score ≤ 6) — the least aggressive category that indicates the cancer that is not likely to spread or kill. For patients on active surveillance, those with MRI-invisible cancers do drastically better than those with visible cancers, Klotz explained.

But other experts in the field are skeptical that MRI-invisible lesions are truly innocuous.

Although statistically an MRI-visible prostate lesion indicates a more aggressive tumor, that is not always the case for every individual, said Brian Helfand, MD, PhD, chief of urology at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Illinois.

MRIs can lead to false negatives in about 10%-20% of patients who have clinically significant prostate cancer, though estimates vary.

In one analysis, 16% of men with no suspicious lesions on MRI had clinically significant prostate cancer identified after undergoing a systematic biopsy. Another analysis found that about 35% of MRI-invisible prostate cancers identified via biopsy were clinically significant.

Other studies, however, have indicated that negative MRI results accurately indicate patients at low risk of developing clinically significant cancers. A recent JAMA Oncology analysis, for instance, found that only seven of 233 men (3%) with negative MRI results at baseline who completed 3 years of monitoring were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancer.

When a patient has an MRI-invisible prostate tumor, there are a couple of reasons the MRI may not be picking it up, said urologic oncologist Alexander Putnam Cole, MD, assistant professor of surgery, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. “One is that the cancer is aggressive but just very small,” said Cole.

“Another possibility is that the cancer looks very similar to background prostate tissue, which is something that you might expect if you think about more of a low-grade cancer,” he explained.

The experience level of the radiologist interpreting the MRI can also play into the accuracy of the reading.

But Cole agreed that “in general, MRI visibility is associated with molecular and histologic features of progression and aggressiveness and non-visible cancers are less likely to have aggressive features.”

The genomic profiles of MRI-visible and -invisible cancers bear this out.

According to Todd Morgan, MD, chief of urologic oncology at Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the gene expression in visible disease tends to be linked to more aggressive prostate tumors whereas gene expression in invisible disease does not.

In one analysis, for instance, researchers found that four genes — PHYHD1, CENPF, ALDH2, and GDF15 — associated with worse progression-free survival and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer also predicted MRI visibility.

“Genes that are associated with visibility are essentially the same genes that are associated with aggressive cancers,” Klotz said.

Next Steps After Negative MRI Result

What do MRI-invisible lesions mean for patient care? If, for instance, a patient has elevated PSA levels but a normal MRI, is a targeted or systematic biopsy warranted?

The overarching message, according to Klotz, is that “you don’t need to find them.” Klotz noted, however, that patients with a negative MRI result should still be followed with periodic repeat imaging.

Several trials support this approach of using MRI to decide who needs a biopsy and delaying a biopsy in men with normal MRIs.

The recent JAMA Oncology analysis found that, among men with negative MRI results, 86% avoided a biopsy over 3 years, with clinically significant prostate cancer detected in only 4% of men across the study period — four in the initial diagnostic phase and seven in the 3-year monitoring phase. However, during the initial diagnostic phase, more than half the men with positive MRI findings had clinically significant prostate cancer detected.

Another recent study found that patients with negative MRI results were much less likely to upgrade to higher Gleason scores over time. Among 522 patients who underwent a systematic and targeted biopsy within 18 months of their grade group 1 designation, 9.2% with negative MRI findings had tumors reclassified as grade group 2 or higher vs 27% with positive MRI findings, and 2.3% with negative MRI findings had tumors reclassified as grade group 3 or higher vs 7.8% with positive MRI findings.

These data suggest that men with grade group 1 cancer and negative MRI result “may be able to avoid confirmatory biopsies until a routine surveillance biopsy in 2-3 years,” according to study author Christian Pavlovich, MD, professor of urologic oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Cole used MRI findings to triage who gets a biopsy. When a biopsy is warranted, “I usually recommend adding in some systematic sampling of the other side to assess for nonvisible cancers,” he noted.

Sampling prostate tissue outside the target area “adds maybe 1-2 minutes to the procedure and doesn’t drastically increase the morbidity or risks,” Cole said. It also can help “confirm there is cancer in the MRI target and also confirm there is no cancer in the nonvisible areas.”

According to Klotz, if imaging demonstrates progression, patients should receive a biopsy — in most cases, a targeted biopsy only. And, Klotz noted, skipping routine prostate biopsies in men with negative MRI results can save thousands of men from these procedures, which carry risks for infections and sepsis.

Looking beyond Gleason scores for risk prediction, MRI “visibility is a very powerful risk stratifier,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MRI-invisible prostate lesions. It sounds like the stuff of science fiction and fantasy, a creation from the minds of H.G. Wells, who wrote The Invisible Man, or J.K. Rowling, who authored the Harry Potter series.

But MRI-invisible prostate lesions are real. And what these lesions may, or may not, indicate is the subject of intense debate.

MRI plays an increasingly important role in detecting and diagnosing prostate cancer, staging prostate cancer as well as monitoring disease progression. However, on occasion, a puzzling phenomenon arises. Certain prostate lesions that appear when pathologists examine biopsied tissue samples under a microscope are not visible on MRI. The prostate tissue will, instead, appear normal to a radiologist’s eye.

Some experts believe these MRI-invisible lesions are nothing to worry about.

If the clinician can’t see the cancer on MRI, then it simply isn’t a threat, according to Mark Emberton, MD, a pioneer in prostate MRIs and director of interventional oncology at University College London, England.

Laurence Klotz, MD, of the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, agreed, noting that “invisible cancers are clinically insignificant and don’t require systematic biopsies.”

Emberton and Klotz compared MRI-invisible lesions to grade group 1 prostate cancer (Gleason score ≤ 6) — the least aggressive category that indicates the cancer that is not likely to spread or kill. For patients on active surveillance, those with MRI-invisible cancers do drastically better than those with visible cancers, Klotz explained.

But other experts in the field are skeptical that MRI-invisible lesions are truly innocuous.

Although statistically an MRI-visible prostate lesion indicates a more aggressive tumor, that is not always the case for every individual, said Brian Helfand, MD, PhD, chief of urology at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Illinois.

MRIs can lead to false negatives in about 10%-20% of patients who have clinically significant prostate cancer, though estimates vary.

In one analysis, 16% of men with no suspicious lesions on MRI had clinically significant prostate cancer identified after undergoing a systematic biopsy. Another analysis found that about 35% of MRI-invisible prostate cancers identified via biopsy were clinically significant.

Other studies, however, have indicated that negative MRI results accurately indicate patients at low risk of developing clinically significant cancers. A recent JAMA Oncology analysis, for instance, found that only seven of 233 men (3%) with negative MRI results at baseline who completed 3 years of monitoring were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancer.

When a patient has an MRI-invisible prostate tumor, there are a couple of reasons the MRI may not be picking it up, said urologic oncologist Alexander Putnam Cole, MD, assistant professor of surgery, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. “One is that the cancer is aggressive but just very small,” said Cole.

“Another possibility is that the cancer looks very similar to background prostate tissue, which is something that you might expect if you think about more of a low-grade cancer,” he explained.

The experience level of the radiologist interpreting the MRI can also play into the accuracy of the reading.

But Cole agreed that “in general, MRI visibility is associated with molecular and histologic features of progression and aggressiveness and non-visible cancers are less likely to have aggressive features.”

The genomic profiles of MRI-visible and -invisible cancers bear this out.

According to Todd Morgan, MD, chief of urologic oncology at Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the gene expression in visible disease tends to be linked to more aggressive prostate tumors whereas gene expression in invisible disease does not.

In one analysis, for instance, researchers found that four genes — PHYHD1, CENPF, ALDH2, and GDF15 — associated with worse progression-free survival and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer also predicted MRI visibility.

“Genes that are associated with visibility are essentially the same genes that are associated with aggressive cancers,” Klotz said.

Next Steps After Negative MRI Result

What do MRI-invisible lesions mean for patient care? If, for instance, a patient has elevated PSA levels but a normal MRI, is a targeted or systematic biopsy warranted?

The overarching message, according to Klotz, is that “you don’t need to find them.” Klotz noted, however, that patients with a negative MRI result should still be followed with periodic repeat imaging.

Several trials support this approach of using MRI to decide who needs a biopsy and delaying a biopsy in men with normal MRIs.

The recent JAMA Oncology analysis found that, among men with negative MRI results, 86% avoided a biopsy over 3 years, with clinically significant prostate cancer detected in only 4% of men across the study period — four in the initial diagnostic phase and seven in the 3-year monitoring phase. However, during the initial diagnostic phase, more than half the men with positive MRI findings had clinically significant prostate cancer detected.

Another recent study found that patients with negative MRI results were much less likely to upgrade to higher Gleason scores over time. Among 522 patients who underwent a systematic and targeted biopsy within 18 months of their grade group 1 designation, 9.2% with negative MRI findings had tumors reclassified as grade group 2 or higher vs 27% with positive MRI findings, and 2.3% with negative MRI findings had tumors reclassified as grade group 3 or higher vs 7.8% with positive MRI findings.

These data suggest that men with grade group 1 cancer and negative MRI result “may be able to avoid confirmatory biopsies until a routine surveillance biopsy in 2-3 years,” according to study author Christian Pavlovich, MD, professor of urologic oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Cole used MRI findings to triage who gets a biopsy. When a biopsy is warranted, “I usually recommend adding in some systematic sampling of the other side to assess for nonvisible cancers,” he noted.

Sampling prostate tissue outside the target area “adds maybe 1-2 minutes to the procedure and doesn’t drastically increase the morbidity or risks,” Cole said. It also can help “confirm there is cancer in the MRI target and also confirm there is no cancer in the nonvisible areas.”

According to Klotz, if imaging demonstrates progression, patients should receive a biopsy — in most cases, a targeted biopsy only. And, Klotz noted, skipping routine prostate biopsies in men with negative MRI results can save thousands of men from these procedures, which carry risks for infections and sepsis.

Looking beyond Gleason scores for risk prediction, MRI “visibility is a very powerful risk stratifier,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

MRI-invisible prostate lesions. It sounds like the stuff of science fiction and fantasy, a creation from the minds of H.G. Wells, who wrote The Invisible Man, or J.K. Rowling, who authored the Harry Potter series.

But MRI-invisible prostate lesions are real. And what these lesions may, or may not, indicate is the subject of intense debate.

MRI plays an increasingly important role in detecting and diagnosing prostate cancer, staging prostate cancer as well as monitoring disease progression. However, on occasion, a puzzling phenomenon arises. Certain prostate lesions that appear when pathologists examine biopsied tissue samples under a microscope are not visible on MRI. The prostate tissue will, instead, appear normal to a radiologist’s eye.

Some experts believe these MRI-invisible lesions are nothing to worry about.

If the clinician can’t see the cancer on MRI, then it simply isn’t a threat, according to Mark Emberton, MD, a pioneer in prostate MRIs and director of interventional oncology at University College London, England.

Laurence Klotz, MD, of the University of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, agreed, noting that “invisible cancers are clinically insignificant and don’t require systematic biopsies.”

Emberton and Klotz compared MRI-invisible lesions to grade group 1 prostate cancer (Gleason score ≤ 6) — the least aggressive category that indicates the cancer that is not likely to spread or kill. For patients on active surveillance, those with MRI-invisible cancers do drastically better than those with visible cancers, Klotz explained.

But other experts in the field are skeptical that MRI-invisible lesions are truly innocuous.

Although statistically an MRI-visible prostate lesion indicates a more aggressive tumor, that is not always the case for every individual, said Brian Helfand, MD, PhD, chief of urology at NorthShore University Health System, Evanston, Illinois.

MRIs can lead to false negatives in about 10%-20% of patients who have clinically significant prostate cancer, though estimates vary.

In one analysis, 16% of men with no suspicious lesions on MRI had clinically significant prostate cancer identified after undergoing a systematic biopsy. Another analysis found that about 35% of MRI-invisible prostate cancers identified via biopsy were clinically significant.

Other studies, however, have indicated that negative MRI results accurately indicate patients at low risk of developing clinically significant cancers. A recent JAMA Oncology analysis, for instance, found that only seven of 233 men (3%) with negative MRI results at baseline who completed 3 years of monitoring were diagnosed with clinically significant prostate cancer.

When a patient has an MRI-invisible prostate tumor, there are a couple of reasons the MRI may not be picking it up, said urologic oncologist Alexander Putnam Cole, MD, assistant professor of surgery, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. “One is that the cancer is aggressive but just very small,” said Cole.

“Another possibility is that the cancer looks very similar to background prostate tissue, which is something that you might expect if you think about more of a low-grade cancer,” he explained.

The experience level of the radiologist interpreting the MRI can also play into the accuracy of the reading.

But Cole agreed that “in general, MRI visibility is associated with molecular and histologic features of progression and aggressiveness and non-visible cancers are less likely to have aggressive features.”

The genomic profiles of MRI-visible and -invisible cancers bear this out.

According to Todd Morgan, MD, chief of urologic oncology at Michigan Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, the gene expression in visible disease tends to be linked to more aggressive prostate tumors whereas gene expression in invisible disease does not.

In one analysis, for instance, researchers found that four genes — PHYHD1, CENPF, ALDH2, and GDF15 — associated with worse progression-free survival and metastasis-free survival in prostate cancer also predicted MRI visibility.

“Genes that are associated with visibility are essentially the same genes that are associated with aggressive cancers,” Klotz said.

Next Steps After Negative MRI Result

What do MRI-invisible lesions mean for patient care? If, for instance, a patient has elevated PSA levels but a normal MRI, is a targeted or systematic biopsy warranted?

The overarching message, according to Klotz, is that “you don’t need to find them.” Klotz noted, however, that patients with a negative MRI result should still be followed with periodic repeat imaging.

Several trials support this approach of using MRI to decide who needs a biopsy and delaying a biopsy in men with normal MRIs.

The recent JAMA Oncology analysis found that, among men with negative MRI results, 86% avoided a biopsy over 3 years, with clinically significant prostate cancer detected in only 4% of men across the study period — four in the initial diagnostic phase and seven in the 3-year monitoring phase. However, during the initial diagnostic phase, more than half the men with positive MRI findings had clinically significant prostate cancer detected.

Another recent study found that patients with negative MRI results were much less likely to upgrade to higher Gleason scores over time. Among 522 patients who underwent a systematic and targeted biopsy within 18 months of their grade group 1 designation, 9.2% with negative MRI findings had tumors reclassified as grade group 2 or higher vs 27% with positive MRI findings, and 2.3% with negative MRI findings had tumors reclassified as grade group 3 or higher vs 7.8% with positive MRI findings.

These data suggest that men with grade group 1 cancer and negative MRI result “may be able to avoid confirmatory biopsies until a routine surveillance biopsy in 2-3 years,” according to study author Christian Pavlovich, MD, professor of urologic oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore.

Cole used MRI findings to triage who gets a biopsy. When a biopsy is warranted, “I usually recommend adding in some systematic sampling of the other side to assess for nonvisible cancers,” he noted.

Sampling prostate tissue outside the target area “adds maybe 1-2 minutes to the procedure and doesn’t drastically increase the morbidity or risks,” Cole said. It also can help “confirm there is cancer in the MRI target and also confirm there is no cancer in the nonvisible areas.”

According to Klotz, if imaging demonstrates progression, patients should receive a biopsy — in most cases, a targeted biopsy only. And, Klotz noted, skipping routine prostate biopsies in men with negative MRI results can save thousands of men from these procedures, which carry risks for infections and sepsis.

Looking beyond Gleason scores for risk prediction, MRI “visibility is a very powerful risk stratifier,” he said.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cellular Therapies for Solid Tumors: The Next Big Thing?

The cutting edge of treating solid tumors with cell therapies got notably sharper in 2024.

First came the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in February 2024 of the tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy lifileucel in unresectable or metastatic melanoma that had progressed on prior immunotherapy, the first cellular therapy for any solid tumor. Then came the August FDA approval of afamitresgene autoleucel in unresectable or metastatic synovial sarcoma with failed chemotherapy, the first engineered T-cell therapy for cancers in soft tissue.

“This was a pipe dream just a decade ago,” Alison Betof Warner, MD, PhD, lead author of a lifileucel study (NCT05640193), said in an interview with Medscape Medical News. “At the start of 2024, we had no approvals of these kinds of products in solid cancers. Now we have two.”

As the director of Solid Tumor Cell Therapy and leader of Stanford Medicine’s Melanoma and Cutaneous Oncology Clinical Research Group, Betof Warner has been at the forefront of developing commercial cell therapy using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

“The approval of lifileucel increases confidence that we can get these therapies across the regulatory finish line and to patients,” Betof Warner said during the interview. She was not involved in the development of afamitresgene autoleucel.

‘Reverse Engineering’

In addition to her contributions to the work that led to lifileucel’s approval, Betof Warner was the lead author on the first consensus guidelines on management and best practices for tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cell therapy.

Betof Warner began studying TILs after doing research with her mentors in immuno-oncology, Jedd D. Wolchok and Michael A. Postow. Their investigations — including one that Betof Warner coauthored — into how monoclonal antibodies and checkpoint inhibitors, such as ipilimumab or nivolumab, might extend the lives of people with advanced unresectable or metastatic melanoma inspired her to push further to find ways to minimize treatment while maximizing outcomes for patients. Betof Warner’s interest overall, she said in the interview, is in capitalizing on what can be learned about how the immune system controls cancer.

“What we know is that the immune system has the ability to kill cancer,” Betof Warner said. “Therefore we need to be thinking about how we can increase immune surveillance. How can we enhance that before a patient develops advanced cancer?

Betof Warner said that although TILs are now standard treatment in melanoma, there is about a 30% response rate compared with about a 50% response rate in immunotherapy, and the latter is easier for the patient to withstand.

“Antibodies on the frontline are better than going through a surgery and then waiting weeks to get your therapy,” Betof Warner said in the interview. “You can come into my clinic and get an antibody therapy in 30 minutes and go straight to work. TILs require patients to be in the hospital for weeks at a time and out of work for months at a time.”

In an effort to combine therapies to maximize best outcomes, a phase 3 trial (NCT05727904) is currently recruiting. The TILVANCE-301 trial will compare immunotherapy plus adoptive cell therapy vs immunotherapy alone in untreated unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Betof Warner is not a part of this study.

Cell Therapies Include CAR T Cells and TCRT

In general, adoptive T-cell therapies such as TILs involve the isolation of autologous immune cells that are removed from the body and either expanded or modified to optimize their efficacy in fighting antigens, before their transfer to the patient as a living drug by infusion.

In addition to TILs, adoptive cell therapies for antitumor therapeutics include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and engineered T-cell receptor therapy (TCRT).

In CAR T-cell therapy and TCRT, naive T cells are harvested from the patient’s blood then engineered to target a tumor. In TIL therapy, tumor-specific T cells are taken from the patient’s tumor. Once extracted, the respective cells are expanded billions of times and then delivered back to the patient’s body, said Betof Warner.

“The main promise of this approach is to generate responses in what we know as ‘cold’ tumors, or tumors that do not have a lot of endogenous T-cell infiltration or where the T cells are not working well, to bring in tumor targeting T cells and then trigger an immune response,” Betof Warner told an audience at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2024 annual meeting.

TIL patients also receive interleukin (IL)-2 infusions to further stimulate the cells. In patients being treated with TCRT, they either receive low or no IL-2, Betof Warner said in her ASCO presentation, “Adopting Cutting-Edge Cell Therapies in Melanoma,” part of the session Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg: Next-Generation Cell-Based Therapies.

Decades in the Making

The National Cancer Institute began investigating TILs in the late 1980s, with the current National Cancer Institute (NCI) surgery chief, Steven Rosenberg, MD, PhD, leading the first-ever trials that showed TILs could shrink tumors in people with advanced melanoma.

Since then, NCI staff and others have also investigated TILs beyond melanoma and additional cell therapies based on CAR T cells and TCRT for antitumor therapeutics.

“TCRs are different from CAR Ts because they go after intracellular antigens instead of extracellular antigens,” said Betof Warner. “That has appeal because many of the tumor antigens we’re looking for will be intracellular.”

Because CAR T cells only target extracellular antigens, their utility is somewhat limited. Although several CAR T-cell therapies exist for blood cancers, there currently are no approved CAR T-cell therapies for solid tumors. However, several trials of CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers and melanoma are ongoing, said Betof Warner, who is not a part of these studies.

“We are starting to see early-phase efficacy in pediatric gliomas,” Betof Warner said, mentioning a study conducted by colleagues at Stanford who demonstrated potential for anti-GD2 CAR T-cell therapy in deadly pediatric diffuse midline gliomas, tumors on the spine and brain.

In their study, nine out of 11 participants (median age, 15 years) showed benefit from the cell therapy, with one participant’s tumors resolving completely. The results paved the way for the FDA to grant a Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy designation for use of anti-GD2 CAR T cells in H3K27M-positive diffuse midline gliomas.

The investigators are now recruiting for a phase 1 trial (NCT04196413). Results of the initial study were published in Nature last month.

Another lesser-known cell therapy expected to advance at some point in the future for solid tumors is use of the body’s natural killer (NK) cells. “They’ve been known about for a long time, but they are more difficult to regulate, which is one reason why it has taken longer to make NK cell therapies,” said Betof Warner, who is not involved in the study of NK cells. “One of their advantages is that, potentially, there could be an ‘off the shelf’ NK product. They don’t necessarily have to be made with autologous cells.”

Risk-Benefit Profiles Depend on Mechanism of Action

If the corresponding TCR sequence of a tumor antigen is known, said Betof Warner, it is possible to use leukapheresis to generate naive circulating lymphocytes. Once infused, the manufactured TCRTs will activate in the body the same as native cells because the signaling is the same.

An advantage to TCRT compared with CAR T-cell therapy is that it targets intracellular proteins, which are significantly present in the tumor, Betof Warner said in her presentation at ASCO 2024. She clarified that tumors will usually be screened for the presence of this antigen before a patient is selected for treatment with that particular therapy, because not all antigens are highly expressed in every tumor.

“Furthermore, the tumor antigen has to be presented by a major histocompatibility complex, meaning there are human leukocyte antigen restrictions, which impacts patient selection,” she said.

A risk with both TCRT and CAR T-cell therapy, according to Betof Warner, is that because there are often shared antigens between tumor and normal tissues, on-target/off-tumor toxicity is a risk.

“TILs are different because they are nonengineered, at least not for antigen recognition. They are polyclonal and go after multiple targets,” Betof Warner said. “TCRs and CARs are engineered to go after one target. So, TILs have much lower rates of on-tumor/off-target effects, vs when you engineer a very high affinity receptor like a TCR or CAR.”

A good example of how this amplification of TCR affinity can lead to poor outcomes is in metastatic melanoma, said Betof Warner.

In investigations (NCI-07-C-0174 and NCI-07-C-0175) of TCRT in metastatic melanoma, for example, the researchers were targeting MART-1 or gp100, which are expressed in melanocytes.

“The problem was that these antigens are also expressed in the eyes and ears, so it caused eye inflammation and hearing loss in a number of patients because it wasn’t specific enough for the tumor,” said Betof Warner. “So, if that target is highly expressed on normal tissue, then you have a high risk.”

Promise of PRAME

Betof Warner said the most promising TCRT at present is the investigational autologous cell therapy IMA203 (NCT03688124), which targets the preferentially expressed antigen (PRAME). Although PRAME is found in many tumors, this testis antigen does not tend to express in normal, healthy adult tissues. Betof Warner is not affiliated with this study.

“It’s maybe the most exciting TCRT cell in melanoma,” Betof Warner told her audience at the ASCO 2024 meeting. Because the expression rate of PRAME in cutaneous and uveal melanoma is at or above 95% and 90%, respectively, she said “it is a really good target in melanoma.”

Phase 1a results reported in late 2023 from a first-in-human trial of IMA203 involving 13 persons with highly advanced melanoma and a median of 5.5 previous treatments showed a 50% objective response rate in the 12 evaluable results. The duration of response ranged between 2.2 and 14.7 months (median follow-up, 14 months).

The safety profile of the treatment was favorable, with no grade 3 adverse events occurring in more than 10% of the cohort, and no grade 5 adverse events at all.

Phase 1b results published in October by maker Immatics showed that in 28 heavily pretreated metastatic melanoma patients, IMA203 had a confirmed objective response rate of 54% with a median duration of response of 12.1 months, while maintaining a favorable tolerability profile.

Accelerated Approvals, Boxed Warnings

The FDA granted accelerated approvals for both lifileucel, the TIL therapy, and afamitresgene autoleucel, the TCRT.

Both were approved with boxed warnings. Lifileucel’s warning is for treatment-related mortality, prolonged severe cytopenia, severe infection, and cardiopulmonary and renal impairment. Afamitresgene autoleucel’s boxed warning is for serious or fatal cytokine release syndrome, which may be severe or life-threatening.

With these approvals, the bar is now raised on TILs and TCRTs, said Betof Warner.

The lifileucel trial studied 73 patients whose melanoma had continued to metastasize despite treatment with a programmed cell death protein (PD-1)/ programmed death-ligand (PD-L1)–targeted immune checkpoint inhibitor and a BRAF inhibitor (if appropriate based on tumor mutation status), and whose lifileucel dose was at least 7.5 billion cells (the approved dose). The cohort also received a median of six IL-2 (aldesleukin) doses.

The objective response rate was 31.5% (95% CI, 21.1-43.4), and median duration of response was not reached (lower bound of 95% CI, 4.1).

In the afamitresgene autoleucel study, 44 of 52 patients with synovial sarcoma received leukapheresis and a single infusion of afamitresgene autoleucel.

The overall response rate was 43.2% (95% CI, 28.4-59.0). The median time to response was 4.9 weeks (95% CI, 4.4-8), and the median duration of response was 6 months (lower bound of 95% CI, 4.6). Among patients who were responsive to the treatment, 45.6% and 39.0% had a duration of response of 6 months or longer and 12 months or longer, respectively.

New Hope for Patients

Betof Warner and her colleagues are now recruiting for an open-label, phase 1/2 investigation of the safety and efficacy of the TIL therapy OBX-115 in adult advanced solid tumors in melanoma or non–small cell lung cancer. The first-in-human results of a previous trial were presented at the ASCO 2024 meeting, and OBX-115 received FDA fast track designation in July.

“I think the results are really promising,” said Betof Warner. “This is an engineered TIL that does not require administering IL-2 to the patient. There were four out of the nine patients who responded to the treatment and there were no dose-limiting toxicities, no cytokine and no intracranial — all of which is excellent.”

For Betof Warner, the possibility that by using their own immune system, patients with advanced and refractory cancers could soon have a one-time treatment with a cell therapy rather than innumerable bouts of chemotherapy pushes her onward.

“The idea that we can treat cancer one time and have it not recur for years — that’s pushing the start of saying there’s a cure of cancer. That a person could move on from cancer like they move on from an infection. That is the potential of this work. We’re not there yet, but that’s where we need to think and dream big,” she said.

Betof Warner disclosed consulting/advisory roles with BluePath Solutions, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Medarex, Immatics, Instil Bio, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Lyell Immunopharma, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer and research funding and travel expenses from Iovance Biotherapeutics.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The cutting edge of treating solid tumors with cell therapies got notably sharper in 2024.

First came the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in February 2024 of the tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy lifileucel in unresectable or metastatic melanoma that had progressed on prior immunotherapy, the first cellular therapy for any solid tumor. Then came the August FDA approval of afamitresgene autoleucel in unresectable or metastatic synovial sarcoma with failed chemotherapy, the first engineered T-cell therapy for cancers in soft tissue.

“This was a pipe dream just a decade ago,” Alison Betof Warner, MD, PhD, lead author of a lifileucel study (NCT05640193), said in an interview with Medscape Medical News. “At the start of 2024, we had no approvals of these kinds of products in solid cancers. Now we have two.”

As the director of Solid Tumor Cell Therapy and leader of Stanford Medicine’s Melanoma and Cutaneous Oncology Clinical Research Group, Betof Warner has been at the forefront of developing commercial cell therapy using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs).

“The approval of lifileucel increases confidence that we can get these therapies across the regulatory finish line and to patients,” Betof Warner said during the interview. She was not involved in the development of afamitresgene autoleucel.

‘Reverse Engineering’

In addition to her contributions to the work that led to lifileucel’s approval, Betof Warner was the lead author on the first consensus guidelines on management and best practices for tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte cell therapy.

Betof Warner began studying TILs after doing research with her mentors in immuno-oncology, Jedd D. Wolchok and Michael A. Postow. Their investigations — including one that Betof Warner coauthored — into how monoclonal antibodies and checkpoint inhibitors, such as ipilimumab or nivolumab, might extend the lives of people with advanced unresectable or metastatic melanoma inspired her to push further to find ways to minimize treatment while maximizing outcomes for patients. Betof Warner’s interest overall, she said in the interview, is in capitalizing on what can be learned about how the immune system controls cancer.

“What we know is that the immune system has the ability to kill cancer,” Betof Warner said. “Therefore we need to be thinking about how we can increase immune surveillance. How can we enhance that before a patient develops advanced cancer?

Betof Warner said that although TILs are now standard treatment in melanoma, there is about a 30% response rate compared with about a 50% response rate in immunotherapy, and the latter is easier for the patient to withstand.

“Antibodies on the frontline are better than going through a surgery and then waiting weeks to get your therapy,” Betof Warner said in the interview. “You can come into my clinic and get an antibody therapy in 30 minutes and go straight to work. TILs require patients to be in the hospital for weeks at a time and out of work for months at a time.”

In an effort to combine therapies to maximize best outcomes, a phase 3 trial (NCT05727904) is currently recruiting. The TILVANCE-301 trial will compare immunotherapy plus adoptive cell therapy vs immunotherapy alone in untreated unresectable or metastatic melanoma. Betof Warner is not a part of this study.

Cell Therapies Include CAR T Cells and TCRT

In general, adoptive T-cell therapies such as TILs involve the isolation of autologous immune cells that are removed from the body and either expanded or modified to optimize their efficacy in fighting antigens, before their transfer to the patient as a living drug by infusion.

In addition to TILs, adoptive cell therapies for antitumor therapeutics include chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells and engineered T-cell receptor therapy (TCRT).

In CAR T-cell therapy and TCRT, naive T cells are harvested from the patient’s blood then engineered to target a tumor. In TIL therapy, tumor-specific T cells are taken from the patient’s tumor. Once extracted, the respective cells are expanded billions of times and then delivered back to the patient’s body, said Betof Warner.

“The main promise of this approach is to generate responses in what we know as ‘cold’ tumors, or tumors that do not have a lot of endogenous T-cell infiltration or where the T cells are not working well, to bring in tumor targeting T cells and then trigger an immune response,” Betof Warner told an audience at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2024 annual meeting.

TIL patients also receive interleukin (IL)-2 infusions to further stimulate the cells. In patients being treated with TCRT, they either receive low or no IL-2, Betof Warner said in her ASCO presentation, “Adopting Cutting-Edge Cell Therapies in Melanoma,” part of the session Beyond the Tip of the Iceberg: Next-Generation Cell-Based Therapies.

Decades in the Making

The National Cancer Institute began investigating TILs in the late 1980s, with the current National Cancer Institute (NCI) surgery chief, Steven Rosenberg, MD, PhD, leading the first-ever trials that showed TILs could shrink tumors in people with advanced melanoma.

Since then, NCI staff and others have also investigated TILs beyond melanoma and additional cell therapies based on CAR T cells and TCRT for antitumor therapeutics.