User login

‘Goodie bag’ pill mill doctor sentenced to 2 decades in prison

A Pennsylvania-based internist was sentenced to 20 years in prison by a federal judge on May 10 for running a prescription “pill mill” from his medical practice.

Since May 2005, Andrew Berkowitz, MD, 62, of Huntington Valley, Pa., was president and CEO of A+ Pain Management, a clinic in the Philadelphia area, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Prosecutors said patients, no matter their complaint, would leave Dr. Berkowitz’s offices with “goodie bags” filled with a selection of drugs. A typical haul included topical analgesics, such as Relyyt and/or lidocaine; muscle relaxants, including chlorzoxazone and/or cyclobenzaprine; anti-inflammatories, such as celecoxib and/or fenoprofen; and schedule IV substances, including tramadol, eszopiclone, and quazepam.

The practice was registered in Pennsylvania as a nonpharmacy dispensing site, allowing Dr. Berkowitz to bill insurers for the drugs, according to The Pennsylvania Record, a journal covering Pennsylvania’s legal system. Dr. Berkowitz also prescribed oxycodone for “pill seeking” patients, who gave him their tacit approval of submitting claims to their insurance providers, which included Medicare, Aetna, and others, for the items in the goodie bag.

In addition, Dr. Berkowitz fraudulently billed insurers for medically unnecessary physical therapy, acupuncture, and chiropractic adjustments, as well as for treatments that were never provided, according to federal officials.

According to the Department of Justice, Dr. Berkowitz collected more than $4,000 per bag from insurers. From 2015 to 2018, prosecutors estimate that Dr. Berkowitz took in more than $4 million in fraudulent proceeds from his scheme.

The pill mill came to the attention of federal authorities after Blue Cross investigators forwarded to the FBI several complaints it had received about Dr. Berkowitz. In 2017, the FBI sent a cooperating witness to Dr. Berkowitz’s clinic. The undercover patient received a prescription for oxycodone, Motrin, and Flexeril and paid $185, according to The Record.

After being indicted in 2019, Dr. Berkowitz pleaded guilty in January 2020 to 19 counts of health care fraud and to 23 counts of distributing oxycodone outside the course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

On May 10, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, followed by 5 years of supervised release. In addition, he was ordered to pay a $40,000 fine and almost $4 million in restitution. As a result of civil False Claims Act liability for false claims submitted to Medicare, he is also obligated to pay approximately $1.8 million and is subject to a permanent prohibition on prescribing, distributing, or dispensing controlled substances.

Dr. Berkowitz’s actions were deemed especially egregious in light of the opioid epidemic.

“Doctors are supposed to treat illness, not feed it,” said Jacqueline Maguire, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Philadelphia division. “Andrew Berkowitz prescribed patients unnecessary pills and handed out opioids to addicts.” Jennifer Arbittier Williams, acting U.S. Attorney, added upon announcing the sentence, “Doctors who dare engage in health care fraud and drug diversion, two drivers of the opioid epidemic ravaging our communities, should heed this sentence as a warning that they will be held responsible, criminally and financially.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Pennsylvania-based internist was sentenced to 20 years in prison by a federal judge on May 10 for running a prescription “pill mill” from his medical practice.

Since May 2005, Andrew Berkowitz, MD, 62, of Huntington Valley, Pa., was president and CEO of A+ Pain Management, a clinic in the Philadelphia area, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Prosecutors said patients, no matter their complaint, would leave Dr. Berkowitz’s offices with “goodie bags” filled with a selection of drugs. A typical haul included topical analgesics, such as Relyyt and/or lidocaine; muscle relaxants, including chlorzoxazone and/or cyclobenzaprine; anti-inflammatories, such as celecoxib and/or fenoprofen; and schedule IV substances, including tramadol, eszopiclone, and quazepam.

The practice was registered in Pennsylvania as a nonpharmacy dispensing site, allowing Dr. Berkowitz to bill insurers for the drugs, according to The Pennsylvania Record, a journal covering Pennsylvania’s legal system. Dr. Berkowitz also prescribed oxycodone for “pill seeking” patients, who gave him their tacit approval of submitting claims to their insurance providers, which included Medicare, Aetna, and others, for the items in the goodie bag.

In addition, Dr. Berkowitz fraudulently billed insurers for medically unnecessary physical therapy, acupuncture, and chiropractic adjustments, as well as for treatments that were never provided, according to federal officials.

According to the Department of Justice, Dr. Berkowitz collected more than $4,000 per bag from insurers. From 2015 to 2018, prosecutors estimate that Dr. Berkowitz took in more than $4 million in fraudulent proceeds from his scheme.

The pill mill came to the attention of federal authorities after Blue Cross investigators forwarded to the FBI several complaints it had received about Dr. Berkowitz. In 2017, the FBI sent a cooperating witness to Dr. Berkowitz’s clinic. The undercover patient received a prescription for oxycodone, Motrin, and Flexeril and paid $185, according to The Record.

After being indicted in 2019, Dr. Berkowitz pleaded guilty in January 2020 to 19 counts of health care fraud and to 23 counts of distributing oxycodone outside the course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

On May 10, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, followed by 5 years of supervised release. In addition, he was ordered to pay a $40,000 fine and almost $4 million in restitution. As a result of civil False Claims Act liability for false claims submitted to Medicare, he is also obligated to pay approximately $1.8 million and is subject to a permanent prohibition on prescribing, distributing, or dispensing controlled substances.

Dr. Berkowitz’s actions were deemed especially egregious in light of the opioid epidemic.

“Doctors are supposed to treat illness, not feed it,” said Jacqueline Maguire, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Philadelphia division. “Andrew Berkowitz prescribed patients unnecessary pills and handed out opioids to addicts.” Jennifer Arbittier Williams, acting U.S. Attorney, added upon announcing the sentence, “Doctors who dare engage in health care fraud and drug diversion, two drivers of the opioid epidemic ravaging our communities, should heed this sentence as a warning that they will be held responsible, criminally and financially.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Pennsylvania-based internist was sentenced to 20 years in prison by a federal judge on May 10 for running a prescription “pill mill” from his medical practice.

Since May 2005, Andrew Berkowitz, MD, 62, of Huntington Valley, Pa., was president and CEO of A+ Pain Management, a clinic in the Philadelphia area, according to his LinkedIn profile.

Prosecutors said patients, no matter their complaint, would leave Dr. Berkowitz’s offices with “goodie bags” filled with a selection of drugs. A typical haul included topical analgesics, such as Relyyt and/or lidocaine; muscle relaxants, including chlorzoxazone and/or cyclobenzaprine; anti-inflammatories, such as celecoxib and/or fenoprofen; and schedule IV substances, including tramadol, eszopiclone, and quazepam.

The practice was registered in Pennsylvania as a nonpharmacy dispensing site, allowing Dr. Berkowitz to bill insurers for the drugs, according to The Pennsylvania Record, a journal covering Pennsylvania’s legal system. Dr. Berkowitz also prescribed oxycodone for “pill seeking” patients, who gave him their tacit approval of submitting claims to their insurance providers, which included Medicare, Aetna, and others, for the items in the goodie bag.

In addition, Dr. Berkowitz fraudulently billed insurers for medically unnecessary physical therapy, acupuncture, and chiropractic adjustments, as well as for treatments that were never provided, according to federal officials.

According to the Department of Justice, Dr. Berkowitz collected more than $4,000 per bag from insurers. From 2015 to 2018, prosecutors estimate that Dr. Berkowitz took in more than $4 million in fraudulent proceeds from his scheme.

The pill mill came to the attention of federal authorities after Blue Cross investigators forwarded to the FBI several complaints it had received about Dr. Berkowitz. In 2017, the FBI sent a cooperating witness to Dr. Berkowitz’s clinic. The undercover patient received a prescription for oxycodone, Motrin, and Flexeril and paid $185, according to The Record.

After being indicted in 2019, Dr. Berkowitz pleaded guilty in January 2020 to 19 counts of health care fraud and to 23 counts of distributing oxycodone outside the course of professional practice and without a legitimate medical purpose.

On May 10, he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, followed by 5 years of supervised release. In addition, he was ordered to pay a $40,000 fine and almost $4 million in restitution. As a result of civil False Claims Act liability for false claims submitted to Medicare, he is also obligated to pay approximately $1.8 million and is subject to a permanent prohibition on prescribing, distributing, or dispensing controlled substances.

Dr. Berkowitz’s actions were deemed especially egregious in light of the opioid epidemic.

“Doctors are supposed to treat illness, not feed it,” said Jacqueline Maguire, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Philadelphia division. “Andrew Berkowitz prescribed patients unnecessary pills and handed out opioids to addicts.” Jennifer Arbittier Williams, acting U.S. Attorney, added upon announcing the sentence, “Doctors who dare engage in health care fraud and drug diversion, two drivers of the opioid epidemic ravaging our communities, should heed this sentence as a warning that they will be held responsible, criminally and financially.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Prior authorizations delay TNF inhibitors for children with JIA

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) who need a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor after failing conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment often experience insurance delays before beginning the new drug because of prior authorization denials, according to research presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA). The findings were also published as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

“Prompt escalation to TNF inhibitors is recommended for children with JIA refractory to DMARDs,” author Jordan Roberts, MD, a clinical fellow of the Harvard Medical School Rheumatology Program, Boston, told CARRA attendees. TNF inhibitors are increasingly used as first-line treatment in JIA since growing evidence suggests better outcomes from early treatment with biologics. “Prior authorization requirements that delay TNF inhibitor initiation among children with JIA are common in clinical practice,” Dr. Roberts said, but little evidence exists to understand the extent of this problem and its causes.

The researchers therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study using a search of electronic health records from January 2018 to December 2019 to find all children at a single center with a new diagnosis of nonsystemic JIA. Then the authors pulled the timing of prior authorization requests, approvals, denials, and first TNF inhibitor dose from the medical notes. They also sought out any children who had been recommended a TNF inhibitor but never started one.

The total population included 54 children with an average age of 10 years, about two-thirds of whom had private insurance (63%). The group was predominantly White (63%), although 13% declined to provide race, and 7% were Hispanic. Most subtypes of disease were represented: oligoarticular persistent (28%), oligoarticular extended (2%), polyarticular rheumatoid factor-negative (15%), polyarticular rheumatoid factor-positive (15%), psoriatic arthritis (26%), enthesitis-related arthritis (12%), and undifferentiated arthritis (2%).

The 44 participants with private insurance had an average of two joints with active disease, while the 10 patients with public insurance had an average of four involved joints. Nearly all the patients (91%) had previously taken or were currently taking DMARDs when the prior authorization was submitted, and 61% had received NSAIDs.

All but one of the patients’ insurance plans required a prior authorization. The first prior authorization was denied for about one-third of the public insurance patients (30%) and a quarter of the private insurance patients. About 1 in 5 patients overall (22%) required a written appeal to override the denial, and 4% required peer-to-peer review. Meanwhile, 7% of patients began another medication because of the denial.

It took a median of 3 days for prior authorizations to be approved and a median of 24 days from the time the TNF inhibitor was recommended to the patient receiving the first dose. However, 22% of patients waited at least 2 weeks before the prior authorization was approved, and more than a quarter of the requests took over 30 days before the patient could begin the medication. In the public insurance group in particular, a quarter of children waited at least 19 days for approval and at least 44 days before starting the medication.

In fact, when the researchers looked at the difference in approval time between those who did and did not receive an initial denial, the difference was stark. Median approval time was 16 days when the prior authorization was denied, compared with a median of 5 days when the first prior authorization was approved. Similarly, time to initiation of the drug after recommendation was a median of 35 days for those whose prior authorization was first denied and 17 days for those with an initial approval.

The most common reason for an initial denial was the insurance company requiring a different TNF inhibitor than the one the rheumatologist wanted to prescribe. “These were all children whose rheumatologist has recommended either infliximab or etanercept that were required to use adalimumab instead,” Dr. Roberts said.

The other reasons for initial denial were similarly familiar ones:

- Required submission to another insurer

- Additional documentation required

- Lack of medical necessity

- Prescription was for an indication not approved by the Food and Drug Administration

- Age of patient

- Nonbiologic DMARD required

- NSAID required for step therapy

Only three children who were advised to begin a TNF inhibitor did not do so, including one who was lost to follow-up, one who had injection-related anxiety, and one who had safety concerns about the medication.

“Several children were required to use alternative TNF inhibitors than the one that was recommended due to restricted formularies, which may reduce shared decisionmaking between physicians and families and may not be the optimal clinical choice for an individual child,” Dr. Roberts said in her conclusion. Most children, however, were able to get approval for the TNF inhibitor originally requested, “suggesting that utilization management strategies present barriers to timely care despite appropriate specialty medication requests,” she said. “Therefore, it’s important for us to advocate for access to medications for children with JIA.”

Findings are not surprising

“I have these same experiences at my institution – often insurance will dictate clinical practice, and step therapy is the only option, causing a delay to initiation of TNFi even if we think, as the pediatric rheumatologist, that a child needs this medicine to be initiated on presentation to our clinic,” Nayimisha Balmuri, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of allergy, immunology, and rheumatology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

Dr. Balmuri, who was not involved in the study, noted that in her clinic at Johns Hopkins, it is hit or miss if an appeal to insurance companies or to the state (if it is Medicaid coverage) will be successful. “Unfortunately, [we are] mostly unsuccessful, and we have to try another DMARD for 8 to 12 weeks first before trying to get TNFi,” she said.

Dr. Balmuri called for bringing these issues to the attention of state and federal legislators. “It’s so important for us to continue to advocate for our patients at the state and national level! We are the advocates for our patients, and we are uniquely trained to know the best medications to initiate to help patients maximize their chance to reach remission of arthritis. Insurance companies need to hear our voices!”

Dr. Roberts reported grants from CARRA, the Lupus Foundation of America, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) who need a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor after failing conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment often experience insurance delays before beginning the new drug because of prior authorization denials, according to research presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA). The findings were also published as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

“Prompt escalation to TNF inhibitors is recommended for children with JIA refractory to DMARDs,” author Jordan Roberts, MD, a clinical fellow of the Harvard Medical School Rheumatology Program, Boston, told CARRA attendees. TNF inhibitors are increasingly used as first-line treatment in JIA since growing evidence suggests better outcomes from early treatment with biologics. “Prior authorization requirements that delay TNF inhibitor initiation among children with JIA are common in clinical practice,” Dr. Roberts said, but little evidence exists to understand the extent of this problem and its causes.

The researchers therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study using a search of electronic health records from January 2018 to December 2019 to find all children at a single center with a new diagnosis of nonsystemic JIA. Then the authors pulled the timing of prior authorization requests, approvals, denials, and first TNF inhibitor dose from the medical notes. They also sought out any children who had been recommended a TNF inhibitor but never started one.

The total population included 54 children with an average age of 10 years, about two-thirds of whom had private insurance (63%). The group was predominantly White (63%), although 13% declined to provide race, and 7% were Hispanic. Most subtypes of disease were represented: oligoarticular persistent (28%), oligoarticular extended (2%), polyarticular rheumatoid factor-negative (15%), polyarticular rheumatoid factor-positive (15%), psoriatic arthritis (26%), enthesitis-related arthritis (12%), and undifferentiated arthritis (2%).

The 44 participants with private insurance had an average of two joints with active disease, while the 10 patients with public insurance had an average of four involved joints. Nearly all the patients (91%) had previously taken or were currently taking DMARDs when the prior authorization was submitted, and 61% had received NSAIDs.

All but one of the patients’ insurance plans required a prior authorization. The first prior authorization was denied for about one-third of the public insurance patients (30%) and a quarter of the private insurance patients. About 1 in 5 patients overall (22%) required a written appeal to override the denial, and 4% required peer-to-peer review. Meanwhile, 7% of patients began another medication because of the denial.

It took a median of 3 days for prior authorizations to be approved and a median of 24 days from the time the TNF inhibitor was recommended to the patient receiving the first dose. However, 22% of patients waited at least 2 weeks before the prior authorization was approved, and more than a quarter of the requests took over 30 days before the patient could begin the medication. In the public insurance group in particular, a quarter of children waited at least 19 days for approval and at least 44 days before starting the medication.

In fact, when the researchers looked at the difference in approval time between those who did and did not receive an initial denial, the difference was stark. Median approval time was 16 days when the prior authorization was denied, compared with a median of 5 days when the first prior authorization was approved. Similarly, time to initiation of the drug after recommendation was a median of 35 days for those whose prior authorization was first denied and 17 days for those with an initial approval.

The most common reason for an initial denial was the insurance company requiring a different TNF inhibitor than the one the rheumatologist wanted to prescribe. “These were all children whose rheumatologist has recommended either infliximab or etanercept that were required to use adalimumab instead,” Dr. Roberts said.

The other reasons for initial denial were similarly familiar ones:

- Required submission to another insurer

- Additional documentation required

- Lack of medical necessity

- Prescription was for an indication not approved by the Food and Drug Administration

- Age of patient

- Nonbiologic DMARD required

- NSAID required for step therapy

Only three children who were advised to begin a TNF inhibitor did not do so, including one who was lost to follow-up, one who had injection-related anxiety, and one who had safety concerns about the medication.

“Several children were required to use alternative TNF inhibitors than the one that was recommended due to restricted formularies, which may reduce shared decisionmaking between physicians and families and may not be the optimal clinical choice for an individual child,” Dr. Roberts said in her conclusion. Most children, however, were able to get approval for the TNF inhibitor originally requested, “suggesting that utilization management strategies present barriers to timely care despite appropriate specialty medication requests,” she said. “Therefore, it’s important for us to advocate for access to medications for children with JIA.”

Findings are not surprising

“I have these same experiences at my institution – often insurance will dictate clinical practice, and step therapy is the only option, causing a delay to initiation of TNFi even if we think, as the pediatric rheumatologist, that a child needs this medicine to be initiated on presentation to our clinic,” Nayimisha Balmuri, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of allergy, immunology, and rheumatology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

Dr. Balmuri, who was not involved in the study, noted that in her clinic at Johns Hopkins, it is hit or miss if an appeal to insurance companies or to the state (if it is Medicaid coverage) will be successful. “Unfortunately, [we are] mostly unsuccessful, and we have to try another DMARD for 8 to 12 weeks first before trying to get TNFi,” she said.

Dr. Balmuri called for bringing these issues to the attention of state and federal legislators. “It’s so important for us to continue to advocate for our patients at the state and national level! We are the advocates for our patients, and we are uniquely trained to know the best medications to initiate to help patients maximize their chance to reach remission of arthritis. Insurance companies need to hear our voices!”

Dr. Roberts reported grants from CARRA, the Lupus Foundation of America, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) who need a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor after failing conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment often experience insurance delays before beginning the new drug because of prior authorization denials, according to research presented at the 2022 annual meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA). The findings were also published as a research letter in JAMA Network Open.

“Prompt escalation to TNF inhibitors is recommended for children with JIA refractory to DMARDs,” author Jordan Roberts, MD, a clinical fellow of the Harvard Medical School Rheumatology Program, Boston, told CARRA attendees. TNF inhibitors are increasingly used as first-line treatment in JIA since growing evidence suggests better outcomes from early treatment with biologics. “Prior authorization requirements that delay TNF inhibitor initiation among children with JIA are common in clinical practice,” Dr. Roberts said, but little evidence exists to understand the extent of this problem and its causes.

The researchers therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study using a search of electronic health records from January 2018 to December 2019 to find all children at a single center with a new diagnosis of nonsystemic JIA. Then the authors pulled the timing of prior authorization requests, approvals, denials, and first TNF inhibitor dose from the medical notes. They also sought out any children who had been recommended a TNF inhibitor but never started one.

The total population included 54 children with an average age of 10 years, about two-thirds of whom had private insurance (63%). The group was predominantly White (63%), although 13% declined to provide race, and 7% were Hispanic. Most subtypes of disease were represented: oligoarticular persistent (28%), oligoarticular extended (2%), polyarticular rheumatoid factor-negative (15%), polyarticular rheumatoid factor-positive (15%), psoriatic arthritis (26%), enthesitis-related arthritis (12%), and undifferentiated arthritis (2%).

The 44 participants with private insurance had an average of two joints with active disease, while the 10 patients with public insurance had an average of four involved joints. Nearly all the patients (91%) had previously taken or were currently taking DMARDs when the prior authorization was submitted, and 61% had received NSAIDs.

All but one of the patients’ insurance plans required a prior authorization. The first prior authorization was denied for about one-third of the public insurance patients (30%) and a quarter of the private insurance patients. About 1 in 5 patients overall (22%) required a written appeal to override the denial, and 4% required peer-to-peer review. Meanwhile, 7% of patients began another medication because of the denial.

It took a median of 3 days for prior authorizations to be approved and a median of 24 days from the time the TNF inhibitor was recommended to the patient receiving the first dose. However, 22% of patients waited at least 2 weeks before the prior authorization was approved, and more than a quarter of the requests took over 30 days before the patient could begin the medication. In the public insurance group in particular, a quarter of children waited at least 19 days for approval and at least 44 days before starting the medication.

In fact, when the researchers looked at the difference in approval time between those who did and did not receive an initial denial, the difference was stark. Median approval time was 16 days when the prior authorization was denied, compared with a median of 5 days when the first prior authorization was approved. Similarly, time to initiation of the drug after recommendation was a median of 35 days for those whose prior authorization was first denied and 17 days for those with an initial approval.

The most common reason for an initial denial was the insurance company requiring a different TNF inhibitor than the one the rheumatologist wanted to prescribe. “These were all children whose rheumatologist has recommended either infliximab or etanercept that were required to use adalimumab instead,” Dr. Roberts said.

The other reasons for initial denial were similarly familiar ones:

- Required submission to another insurer

- Additional documentation required

- Lack of medical necessity

- Prescription was for an indication not approved by the Food and Drug Administration

- Age of patient

- Nonbiologic DMARD required

- NSAID required for step therapy

Only three children who were advised to begin a TNF inhibitor did not do so, including one who was lost to follow-up, one who had injection-related anxiety, and one who had safety concerns about the medication.

“Several children were required to use alternative TNF inhibitors than the one that was recommended due to restricted formularies, which may reduce shared decisionmaking between physicians and families and may not be the optimal clinical choice for an individual child,” Dr. Roberts said in her conclusion. Most children, however, were able to get approval for the TNF inhibitor originally requested, “suggesting that utilization management strategies present barriers to timely care despite appropriate specialty medication requests,” she said. “Therefore, it’s important for us to advocate for access to medications for children with JIA.”

Findings are not surprising

“I have these same experiences at my institution – often insurance will dictate clinical practice, and step therapy is the only option, causing a delay to initiation of TNFi even if we think, as the pediatric rheumatologist, that a child needs this medicine to be initiated on presentation to our clinic,” Nayimisha Balmuri, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics in the division of allergy, immunology, and rheumatology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, told this news organization.

Dr. Balmuri, who was not involved in the study, noted that in her clinic at Johns Hopkins, it is hit or miss if an appeal to insurance companies or to the state (if it is Medicaid coverage) will be successful. “Unfortunately, [we are] mostly unsuccessful, and we have to try another DMARD for 8 to 12 weeks first before trying to get TNFi,” she said.

Dr. Balmuri called for bringing these issues to the attention of state and federal legislators. “It’s so important for us to continue to advocate for our patients at the state and national level! We are the advocates for our patients, and we are uniquely trained to know the best medications to initiate to help patients maximize their chance to reach remission of arthritis. Insurance companies need to hear our voices!”

Dr. Roberts reported grants from CARRA, the Lupus Foundation of America, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases during the conduct of the study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Does platelet-rich plasma improve patellar tendinopathy symptoms?

Evidence summary

Symptoms improve with PRP—but not significantly

A 2014 double-blind RCT (n = 23) explored recovery outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who received either 1 injection of leukocyte-rich PRP or ultrasound-guided dry needling.1 Both groups also completed standardized eccentric exercises. Participants were predominantly men, ages ≥ 18 years. Symptomatic improvement was assessed using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment–Patella (VISA-P), an 8-item subjective questionnaire of functionality with a range of 0 to 100, with 100 as the maximum score for an asymptomatic individual.

At 12 weeks posttreatment, VISA-P scores improved in both groups. However, the improvement in the dry needling group was not statistically significant (5.2 points; 95% CI, –2.2 to 12.6; P = .20), while in the PRP group it was statistically significant (25.4 points; 95% CI, 10.3 to 40.6; P = .01). At ≥ 26 weeks, statistically significant improvement was observed in both treatment groups: scores improved by 33.2 points (95% CI, 24.1 to 42.4; P = .001) in the dry needling group and by 28.9 points (95% CI, 11.4 to 46.3; P = .01) in the PRP group. However, the difference between the groups’ VISA-P scores at ≥ 26 weeks was not significant (P = .66).1

No significant differences observed for PRP vs placebo or physical therapy

A 2019 single-blind RCT (n = 57) involved patients who were treated with 1 injection of either leukocyte-rich PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP, or saline, all in combination with 6 weeks of physical therapy.2 Participants were predominantly men, ages 18 to 50 years, and engaged in recreational sporting activities. There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in VISA-P score at any timepoint of the 2-year study period. P values were not reported.2

A 2010 RCT (n = 31) compared PRP (unspecified whether leukocyte-rich or -poor) in combination with physical therapy to physical therapy alone.3 Groups were matched for sex, age, and sports activity level; patients in the PRP group were required to have failed previous treatment, while control subjects must not have received any treatment for at least 2 months. Subjects were evaluated pretreatment, immediately posttreatment, and 6 months posttreatment. Clinical evaluation was aided by use of the Tegner activity score, a 1-item score that grades activity level on a scale of 0 to 10; the EuroQol-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which evaluates subjective rating of overall health; and pain level scores.

At 6 months posttreatment, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups in EQ-VAS and pain level scores. However, Tegner activity scores among PRP recipients showed significant percent improvement over controls at 6 months posttreatment (39% vs 20%; P = .048).3

Recommendations from others

Currently, national orthopedic and professional athletic medical associations have recommended that further research be conducted in order to make a strong statement in favor of or against PRP.4,5

Editor’s takeaway

Existing data regarding PRP fails, again, to show consistent benefits. These small sample sizes, inconsistent comparators, and heterogeneous results limit our certainty. This lack of quality evidence does not prove a lack of effect, but it raises serious doubts.

1. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416

2. Scott A, LaPrade R, Harmon K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial of leukocyte-rich PRP or leukocyte-poor PRP versus saline. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1654-1661. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837954

3. Filardo G, Kon E, Villa S Della, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34:909. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7

4. LaPrade R, Dragoo J, Koh J, et al. AAOS Research Symposium updates and consensus: biologic treatment of orthopaedic injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:e62-e78. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00086

5. Rodeo SA, Bedi A. 2019-2020 NFL and NFL Physician Society orthobiologics consensus statement. Sports Health. 2020;12:58-60. doi: 10.1177/1941738119889013

Evidence summary

Symptoms improve with PRP—but not significantly

A 2014 double-blind RCT (n = 23) explored recovery outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who received either 1 injection of leukocyte-rich PRP or ultrasound-guided dry needling.1 Both groups also completed standardized eccentric exercises. Participants were predominantly men, ages ≥ 18 years. Symptomatic improvement was assessed using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment–Patella (VISA-P), an 8-item subjective questionnaire of functionality with a range of 0 to 100, with 100 as the maximum score for an asymptomatic individual.

At 12 weeks posttreatment, VISA-P scores improved in both groups. However, the improvement in the dry needling group was not statistically significant (5.2 points; 95% CI, –2.2 to 12.6; P = .20), while in the PRP group it was statistically significant (25.4 points; 95% CI, 10.3 to 40.6; P = .01). At ≥ 26 weeks, statistically significant improvement was observed in both treatment groups: scores improved by 33.2 points (95% CI, 24.1 to 42.4; P = .001) in the dry needling group and by 28.9 points (95% CI, 11.4 to 46.3; P = .01) in the PRP group. However, the difference between the groups’ VISA-P scores at ≥ 26 weeks was not significant (P = .66).1

No significant differences observed for PRP vs placebo or physical therapy

A 2019 single-blind RCT (n = 57) involved patients who were treated with 1 injection of either leukocyte-rich PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP, or saline, all in combination with 6 weeks of physical therapy.2 Participants were predominantly men, ages 18 to 50 years, and engaged in recreational sporting activities. There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in VISA-P score at any timepoint of the 2-year study period. P values were not reported.2

A 2010 RCT (n = 31) compared PRP (unspecified whether leukocyte-rich or -poor) in combination with physical therapy to physical therapy alone.3 Groups were matched for sex, age, and sports activity level; patients in the PRP group were required to have failed previous treatment, while control subjects must not have received any treatment for at least 2 months. Subjects were evaluated pretreatment, immediately posttreatment, and 6 months posttreatment. Clinical evaluation was aided by use of the Tegner activity score, a 1-item score that grades activity level on a scale of 0 to 10; the EuroQol-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which evaluates subjective rating of overall health; and pain level scores.

At 6 months posttreatment, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups in EQ-VAS and pain level scores. However, Tegner activity scores among PRP recipients showed significant percent improvement over controls at 6 months posttreatment (39% vs 20%; P = .048).3

Recommendations from others

Currently, national orthopedic and professional athletic medical associations have recommended that further research be conducted in order to make a strong statement in favor of or against PRP.4,5

Editor’s takeaway

Existing data regarding PRP fails, again, to show consistent benefits. These small sample sizes, inconsistent comparators, and heterogeneous results limit our certainty. This lack of quality evidence does not prove a lack of effect, but it raises serious doubts.

Evidence summary

Symptoms improve with PRP—but not significantly

A 2014 double-blind RCT (n = 23) explored recovery outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who received either 1 injection of leukocyte-rich PRP or ultrasound-guided dry needling.1 Both groups also completed standardized eccentric exercises. Participants were predominantly men, ages ≥ 18 years. Symptomatic improvement was assessed using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment–Patella (VISA-P), an 8-item subjective questionnaire of functionality with a range of 0 to 100, with 100 as the maximum score for an asymptomatic individual.

At 12 weeks posttreatment, VISA-P scores improved in both groups. However, the improvement in the dry needling group was not statistically significant (5.2 points; 95% CI, –2.2 to 12.6; P = .20), while in the PRP group it was statistically significant (25.4 points; 95% CI, 10.3 to 40.6; P = .01). At ≥ 26 weeks, statistically significant improvement was observed in both treatment groups: scores improved by 33.2 points (95% CI, 24.1 to 42.4; P = .001) in the dry needling group and by 28.9 points (95% CI, 11.4 to 46.3; P = .01) in the PRP group. However, the difference between the groups’ VISA-P scores at ≥ 26 weeks was not significant (P = .66).1

No significant differences observed for PRP vs placebo or physical therapy

A 2019 single-blind RCT (n = 57) involved patients who were treated with 1 injection of either leukocyte-rich PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP, or saline, all in combination with 6 weeks of physical therapy.2 Participants were predominantly men, ages 18 to 50 years, and engaged in recreational sporting activities. There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in VISA-P score at any timepoint of the 2-year study period. P values were not reported.2

A 2010 RCT (n = 31) compared PRP (unspecified whether leukocyte-rich or -poor) in combination with physical therapy to physical therapy alone.3 Groups were matched for sex, age, and sports activity level; patients in the PRP group were required to have failed previous treatment, while control subjects must not have received any treatment for at least 2 months. Subjects were evaluated pretreatment, immediately posttreatment, and 6 months posttreatment. Clinical evaluation was aided by use of the Tegner activity score, a 1-item score that grades activity level on a scale of 0 to 10; the EuroQol-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which evaluates subjective rating of overall health; and pain level scores.

At 6 months posttreatment, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups in EQ-VAS and pain level scores. However, Tegner activity scores among PRP recipients showed significant percent improvement over controls at 6 months posttreatment (39% vs 20%; P = .048).3

Recommendations from others

Currently, national orthopedic and professional athletic medical associations have recommended that further research be conducted in order to make a strong statement in favor of or against PRP.4,5

Editor’s takeaway

Existing data regarding PRP fails, again, to show consistent benefits. These small sample sizes, inconsistent comparators, and heterogeneous results limit our certainty. This lack of quality evidence does not prove a lack of effect, but it raises serious doubts.

1. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416

2. Scott A, LaPrade R, Harmon K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial of leukocyte-rich PRP or leukocyte-poor PRP versus saline. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1654-1661. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837954

3. Filardo G, Kon E, Villa S Della, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34:909. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7

4. LaPrade R, Dragoo J, Koh J, et al. AAOS Research Symposium updates and consensus: biologic treatment of orthopaedic injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:e62-e78. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00086

5. Rodeo SA, Bedi A. 2019-2020 NFL and NFL Physician Society orthobiologics consensus statement. Sports Health. 2020;12:58-60. doi: 10.1177/1941738119889013

1. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416

2. Scott A, LaPrade R, Harmon K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial of leukocyte-rich PRP or leukocyte-poor PRP versus saline. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1654-1661. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837954

3. Filardo G, Kon E, Villa S Della, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34:909. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7

4. LaPrade R, Dragoo J, Koh J, et al. AAOS Research Symposium updates and consensus: biologic treatment of orthopaedic injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:e62-e78. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00086

5. Rodeo SA, Bedi A. 2019-2020 NFL and NFL Physician Society orthobiologics consensus statement. Sports Health. 2020;12:58-60. doi: 10.1177/1941738119889013

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

IT’S UNCLEAR. High-quality data have not consistently established the effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections to improve symptomatic recovery in patellar tendinopathy, compared to placebo (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on 3 small randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). The 3 small RCTs included only 111 patients, total. One found no evidence of significant improvement with PRP compared to controls. The other 2 studies showed mixed results, with different outcome measures favoring different treatment groups and heterogeneous results depending on follow-up duration.

43-year-old male • fatigue • unintentional weight loss • pancytopenia • Dx?

THE CASE

A 43-year-old Black male presented to his primary care physician with an 8-month history of progressive fatigue, weakness, and unintentional weight loss. The patient’s history also included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) with prior deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism for which he was taking warfarin.

At the time of presentation, he reported profound dyspnea on exertion, lightheadedness, dry mouth, low back pain, and worsening nocturia. The remainder of the review of systems was negative. He denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use or recent travel. His personal and family histories were negative for cancer.

Laboratory data collected during the outpatient visit were notable for a white blood cell count of 2300/mcL (reference range, 4000-11,000/mcL); hemoglobin, 8.6 g/dL (13.5-17.5 g/dL); and platelets, 44,000/mcL (150,000-400,000/mcL). Proteinuria was indicated by a measurement > 500 mg/dL on urine dipstick.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up of new pancytopenia. His vital signs on admission were notable for tachycardia and a weight of 237 lbs, decreased from 283 lbs 8 months prior. His physical exam revealed dry mucous membranes, bruising of fingertips, and marked lower extremity weakness with preserved sensation. No lymphadenopathy was noted on the admission physical exam.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Inpatient laboratory studies showed elevated inflammatory markers and a positive Coombs test with low haptoglobin. There was no evidence of bacterial or viral infection.

Autoimmune laboratory data included a positive antiphospholipid antibody (ANA) test (1:10,240, diffuse; reference < 1:160), an elevated dsDNA antibody level (800 IU/mL; reference range, 0-99 IU/mL), low complement levels, and antibody titers consistent with the patient’s known APS. Based on these findings, the patient was given a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

DISCUSSION

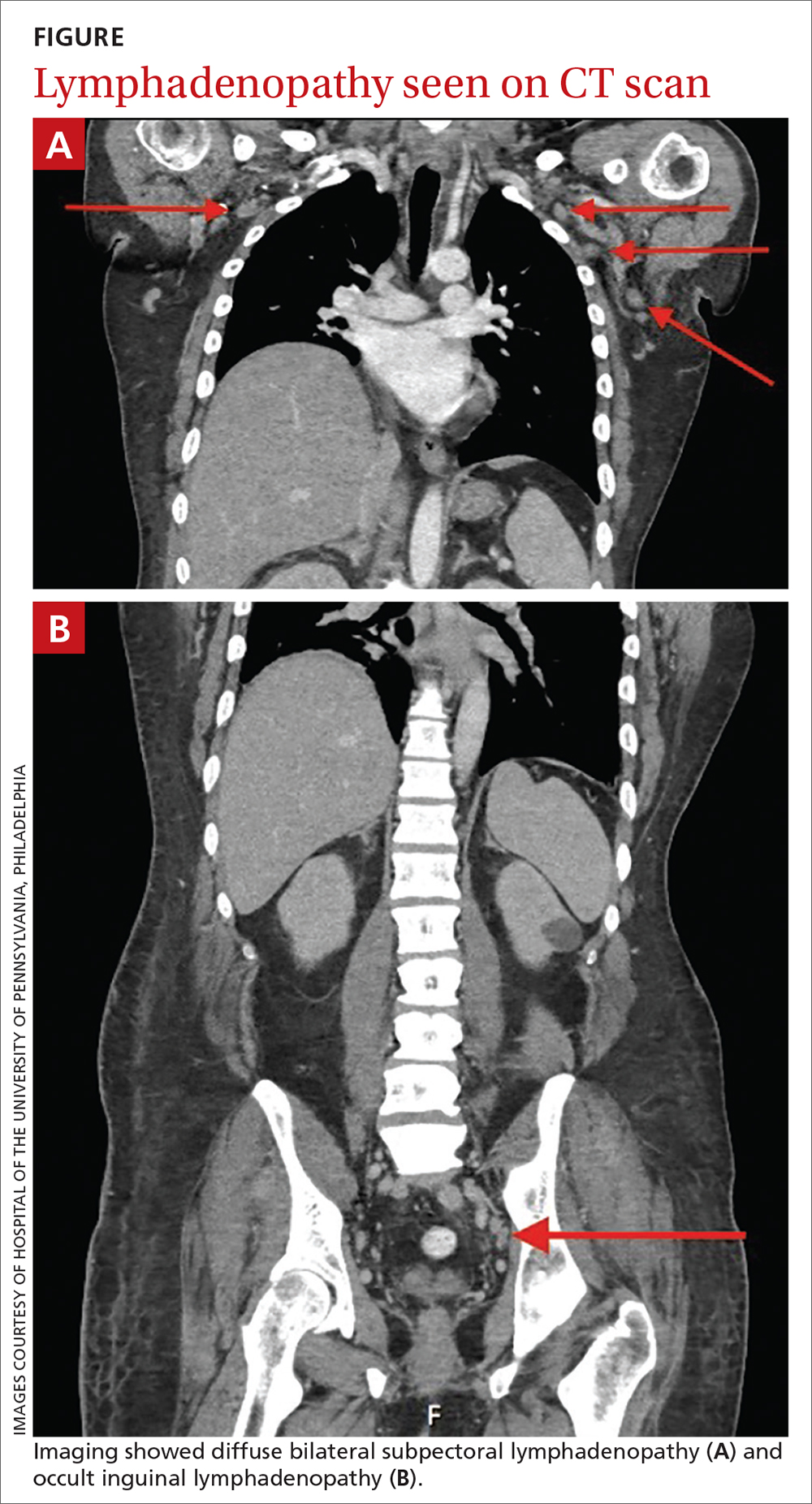

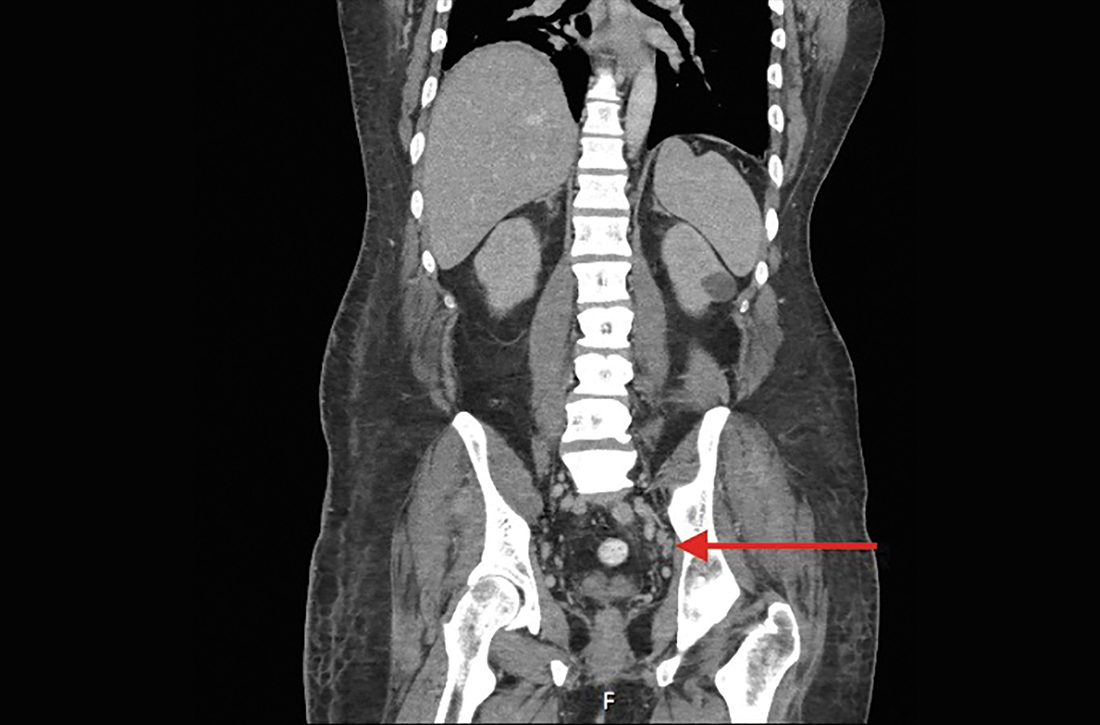

Lymphadenopathy, revealed by exam or by imaging, in combination with systemic symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue, elicits an extensive differential diagnosis. In the absence of recent exposures, travel, or risk factors for infectious causes, our patient’s work-up was appropriately narrowed to noninfectious etiologies of pancytopenia and lymphadenopathy. At the top of this differential are malignancies—in particular, multiple myeloma and lymphoma—and rheumatologic processes, such as sarcoidosis, connective tissue disease, and SLE.1,2 Ultimately, the combination of autoimmune markers with the pancytopenia and a negative work-up for malignancy confirmed a diagnosis of SLE.

Continue to: SLE classification and generalized lymphadenopathy

SLE classification and generalized lymphadenopathy. SLE is a multisystem inflammatory process with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established validated criteria to aid in the diagnosis of SLE,3 which were most recently updated in 2012 to improve clinical utility. For a diagnosis to be made, at least 1 clinical and 1 immunologic criterion must be present or a renal biopsy must show lupus nephritis.3

Notably, lymphadenopathy is not included in this validated model, despite its occurrence in 25% to 50% of patients with SLE.1,3,4 With this in mind, SLE should be considered in the work-up of generalized lymphadenopathy.

ANA and SLE. Although it is estimated that 30% to 40% of patients with SLE test positive for ANA,5 the presence of ANA also is not part of the diagnostic criteria for SLE. Interestingly, the co-occurrence of the 2 has clinical implications for patients. In particular, patients with SLE and a positive ANA have higher prevalence of thrombosis, valvular disease, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia, among other complications.5 Although our patient’s presentation of thrombocytopenia and hemolysis clouded the initial work-up, such a combination is consistent with co-presentation of SLE and APS.

Differences in sex, age, and race. SLE is more common in women than in men, with a prevalence ratio of 7:1.6 It is estimated that 65% of patients with SLE experience disease onset between the ages of 16 and 55 years.7

The median age of diagnosis also differs based on sex and race: According to Rus et al,8 the typical age ranges are 37 to 50 years for White women; 50 to 59 for White men; 15 to 44 for Black women; and 45 to 64 for Black men. These estimates of incidence stratified by race, sex, and age can be helpful when evaluating patients with confusing clinical presentations. Our patient’s age was consistent with the median for his sex and race.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient was started on oral prednisone 60 mg/d with plans for a prolonged taper over 6 months under the close supervision of Rheumatology. His weakness and polyuria began to improve within a month, and lupus-related symptoms resolved within 3 months. His cytopenia also significantly improved, with the exception of refractory thrombocytopenia.

THE TAKEAWAY

SLE is a common diagnosis with multiple presentations. Although lymphadenopathy is not part of the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of SLE, multiple case studies have highlighted its prevalence among affected patients.1,2,4,9-17 APS and antiphospholipid antibodies are also absent in the diagnostic criteria despite being highly associated with SLE. Thus, co-presentation (as well as age and sex) can be helpful with both disease stratification and risk assessment once a diagnosis is made.

CORRESPONDENCE

Isabella Buzzo Bellon Brout, MD, 409 West Broadway, Boston, MA 02127; [email protected]

1. Afzal W, Arab T, Ullah T, et al. Generalized lymphadenopathy as presenting features of systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of literature. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8:819-823. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2717w

2. Smith LW, Petri M. Diffuse lymphadenopathy as the presenting manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:397-399. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182a6a924

3. Petri M, Orbai A, Graciela S, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-2686. doi: 10.1002/art.34473

4. Kitsanou M, Adreopoulou E, Bai MK, et al. Extensive lymphadenopathy as the first clinical manifestation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9:140-143. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828037

5. Unlu O, Zuily S, Erkan D. The clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:75-84. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0085

6. Lahita RG. The role of sex hormones in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:352-356. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199909000-00005

7. Rothfield N. Clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Kelley WN, Harris ED, Ruddy S, Sledge CB (eds). Textbook of Rheumatology. WB Saunders; 1981.

8. Rus V, Maury EE, Hochberg MC. The epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Wallace DJ, Hahn BH (eds). Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002.

9. Biner B, Acunas B, Karasalihoglu S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy: a case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2001;43:94-96.

10. Gilmore R, Sin WY. Systemic lupus erythematosus mimicking lymphoma: the relevance of the clinical background in interpreting imaging studies. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013201802. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201802

11. Shrestha D, Dhakal AK, Shiva RK, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and granulomatous lymphadenopathy. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-179

12. Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M. The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Rheumatol Port. 2008;33:402-406.

13. Tamaki K, Morishima S, Nakachi S, et al. An atypical case of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with systemic lymphadenopathy and severe autoimmune thrombocytopenia/neutropenia mimicking malignant lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2017;105:526-531. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2126-8

14. Hyami T, Kato T, Moritani S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus with abdominal lymphadenopathy. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:342-344. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3589

15. Mull ES, Aranez V, Pierce D, et al. Newly diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus: atypical presentation with focal seizures and long-standing lymphadenopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:e109-e113. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000681

16. Kassan SS, Moss ML, Reddick RL. Progressive hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus on corticosteroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1382-1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197606172942506

17. Tuinman PR, Nieuwenhuis MB, Groen E, et al. A young woman with generalized lymphadenopathy. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Neth J Med. 2011;69:284-288.

THE CASE

A 43-year-old Black male presented to his primary care physician with an 8-month history of progressive fatigue, weakness, and unintentional weight loss. The patient’s history also included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) with prior deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism for which he was taking warfarin.

At the time of presentation, he reported profound dyspnea on exertion, lightheadedness, dry mouth, low back pain, and worsening nocturia. The remainder of the review of systems was negative. He denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use or recent travel. His personal and family histories were negative for cancer.

Laboratory data collected during the outpatient visit were notable for a white blood cell count of 2300/mcL (reference range, 4000-11,000/mcL); hemoglobin, 8.6 g/dL (13.5-17.5 g/dL); and platelets, 44,000/mcL (150,000-400,000/mcL). Proteinuria was indicated by a measurement > 500 mg/dL on urine dipstick.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up of new pancytopenia. His vital signs on admission were notable for tachycardia and a weight of 237 lbs, decreased from 283 lbs 8 months prior. His physical exam revealed dry mucous membranes, bruising of fingertips, and marked lower extremity weakness with preserved sensation. No lymphadenopathy was noted on the admission physical exam.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Inpatient laboratory studies showed elevated inflammatory markers and a positive Coombs test with low haptoglobin. There was no evidence of bacterial or viral infection.

Autoimmune laboratory data included a positive antiphospholipid antibody (ANA) test (1:10,240, diffuse; reference < 1:160), an elevated dsDNA antibody level (800 IU/mL; reference range, 0-99 IU/mL), low complement levels, and antibody titers consistent with the patient’s known APS. Based on these findings, the patient was given a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

DISCUSSION

Lymphadenopathy, revealed by exam or by imaging, in combination with systemic symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue, elicits an extensive differential diagnosis. In the absence of recent exposures, travel, or risk factors for infectious causes, our patient’s work-up was appropriately narrowed to noninfectious etiologies of pancytopenia and lymphadenopathy. At the top of this differential are malignancies—in particular, multiple myeloma and lymphoma—and rheumatologic processes, such as sarcoidosis, connective tissue disease, and SLE.1,2 Ultimately, the combination of autoimmune markers with the pancytopenia and a negative work-up for malignancy confirmed a diagnosis of SLE.

Continue to: SLE classification and generalized lymphadenopathy

SLE classification and generalized lymphadenopathy. SLE is a multisystem inflammatory process with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established validated criteria to aid in the diagnosis of SLE,3 which were most recently updated in 2012 to improve clinical utility. For a diagnosis to be made, at least 1 clinical and 1 immunologic criterion must be present or a renal biopsy must show lupus nephritis.3

Notably, lymphadenopathy is not included in this validated model, despite its occurrence in 25% to 50% of patients with SLE.1,3,4 With this in mind, SLE should be considered in the work-up of generalized lymphadenopathy.

ANA and SLE. Although it is estimated that 30% to 40% of patients with SLE test positive for ANA,5 the presence of ANA also is not part of the diagnostic criteria for SLE. Interestingly, the co-occurrence of the 2 has clinical implications for patients. In particular, patients with SLE and a positive ANA have higher prevalence of thrombosis, valvular disease, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia, among other complications.5 Although our patient’s presentation of thrombocytopenia and hemolysis clouded the initial work-up, such a combination is consistent with co-presentation of SLE and APS.

Differences in sex, age, and race. SLE is more common in women than in men, with a prevalence ratio of 7:1.6 It is estimated that 65% of patients with SLE experience disease onset between the ages of 16 and 55 years.7

The median age of diagnosis also differs based on sex and race: According to Rus et al,8 the typical age ranges are 37 to 50 years for White women; 50 to 59 for White men; 15 to 44 for Black women; and 45 to 64 for Black men. These estimates of incidence stratified by race, sex, and age can be helpful when evaluating patients with confusing clinical presentations. Our patient’s age was consistent with the median for his sex and race.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient was started on oral prednisone 60 mg/d with plans for a prolonged taper over 6 months under the close supervision of Rheumatology. His weakness and polyuria began to improve within a month, and lupus-related symptoms resolved within 3 months. His cytopenia also significantly improved, with the exception of refractory thrombocytopenia.

THE TAKEAWAY

SLE is a common diagnosis with multiple presentations. Although lymphadenopathy is not part of the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of SLE, multiple case studies have highlighted its prevalence among affected patients.1,2,4,9-17 APS and antiphospholipid antibodies are also absent in the diagnostic criteria despite being highly associated with SLE. Thus, co-presentation (as well as age and sex) can be helpful with both disease stratification and risk assessment once a diagnosis is made.

CORRESPONDENCE

Isabella Buzzo Bellon Brout, MD, 409 West Broadway, Boston, MA 02127; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 43-year-old Black male presented to his primary care physician with an 8-month history of progressive fatigue, weakness, and unintentional weight loss. The patient’s history also included antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APS) with prior deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism for which he was taking warfarin.

At the time of presentation, he reported profound dyspnea on exertion, lightheadedness, dry mouth, low back pain, and worsening nocturia. The remainder of the review of systems was negative. He denied tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drug use or recent travel. His personal and family histories were negative for cancer.

Laboratory data collected during the outpatient visit were notable for a white blood cell count of 2300/mcL (reference range, 4000-11,000/mcL); hemoglobin, 8.6 g/dL (13.5-17.5 g/dL); and platelets, 44,000/mcL (150,000-400,000/mcL). Proteinuria was indicated by a measurement > 500 mg/dL on urine dipstick.

The patient was admitted to the hospital for further work-up of new pancytopenia. His vital signs on admission were notable for tachycardia and a weight of 237 lbs, decreased from 283 lbs 8 months prior. His physical exam revealed dry mucous membranes, bruising of fingertips, and marked lower extremity weakness with preserved sensation. No lymphadenopathy was noted on the admission physical exam.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Inpatient laboratory studies showed elevated inflammatory markers and a positive Coombs test with low haptoglobin. There was no evidence of bacterial or viral infection.

Autoimmune laboratory data included a positive antiphospholipid antibody (ANA) test (1:10,240, diffuse; reference < 1:160), an elevated dsDNA antibody level (800 IU/mL; reference range, 0-99 IU/mL), low complement levels, and antibody titers consistent with the patient’s known APS. Based on these findings, the patient was given a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

DISCUSSION

Lymphadenopathy, revealed by exam or by imaging, in combination with systemic symptoms such as weight loss and fatigue, elicits an extensive differential diagnosis. In the absence of recent exposures, travel, or risk factors for infectious causes, our patient’s work-up was appropriately narrowed to noninfectious etiologies of pancytopenia and lymphadenopathy. At the top of this differential are malignancies—in particular, multiple myeloma and lymphoma—and rheumatologic processes, such as sarcoidosis, connective tissue disease, and SLE.1,2 Ultimately, the combination of autoimmune markers with the pancytopenia and a negative work-up for malignancy confirmed a diagnosis of SLE.

Continue to: SLE classification and generalized lymphadenopathy

SLE classification and generalized lymphadenopathy. SLE is a multisystem inflammatory process with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has established validated criteria to aid in the diagnosis of SLE,3 which were most recently updated in 2012 to improve clinical utility. For a diagnosis to be made, at least 1 clinical and 1 immunologic criterion must be present or a renal biopsy must show lupus nephritis.3

Notably, lymphadenopathy is not included in this validated model, despite its occurrence in 25% to 50% of patients with SLE.1,3,4 With this in mind, SLE should be considered in the work-up of generalized lymphadenopathy.

ANA and SLE. Although it is estimated that 30% to 40% of patients with SLE test positive for ANA,5 the presence of ANA also is not part of the diagnostic criteria for SLE. Interestingly, the co-occurrence of the 2 has clinical implications for patients. In particular, patients with SLE and a positive ANA have higher prevalence of thrombosis, valvular disease, thrombocytopenia, and hemolytic anemia, among other complications.5 Although our patient’s presentation of thrombocytopenia and hemolysis clouded the initial work-up, such a combination is consistent with co-presentation of SLE and APS.

Differences in sex, age, and race. SLE is more common in women than in men, with a prevalence ratio of 7:1.6 It is estimated that 65% of patients with SLE experience disease onset between the ages of 16 and 55 years.7

The median age of diagnosis also differs based on sex and race: According to Rus et al,8 the typical age ranges are 37 to 50 years for White women; 50 to 59 for White men; 15 to 44 for Black women; and 45 to 64 for Black men. These estimates of incidence stratified by race, sex, and age can be helpful when evaluating patients with confusing clinical presentations. Our patient’s age was consistent with the median for his sex and race.

Continue to: Our patient

Our patient was started on oral prednisone 60 mg/d with plans for a prolonged taper over 6 months under the close supervision of Rheumatology. His weakness and polyuria began to improve within a month, and lupus-related symptoms resolved within 3 months. His cytopenia also significantly improved, with the exception of refractory thrombocytopenia.

THE TAKEAWAY

SLE is a common diagnosis with multiple presentations. Although lymphadenopathy is not part of the clinical criteria for the diagnosis of SLE, multiple case studies have highlighted its prevalence among affected patients.1,2,4,9-17 APS and antiphospholipid antibodies are also absent in the diagnostic criteria despite being highly associated with SLE. Thus, co-presentation (as well as age and sex) can be helpful with both disease stratification and risk assessment once a diagnosis is made.

CORRESPONDENCE

Isabella Buzzo Bellon Brout, MD, 409 West Broadway, Boston, MA 02127; [email protected]

1. Afzal W, Arab T, Ullah T, et al. Generalized lymphadenopathy as presenting features of systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of literature. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8:819-823. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2717w

2. Smith LW, Petri M. Diffuse lymphadenopathy as the presenting manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:397-399. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182a6a924

3. Petri M, Orbai A, Graciela S, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-2686. doi: 10.1002/art.34473

4. Kitsanou M, Adreopoulou E, Bai MK, et al. Extensive lymphadenopathy as the first clinical manifestation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9:140-143. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828037

5. Unlu O, Zuily S, Erkan D. The clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:75-84. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0085

6. Lahita RG. The role of sex hormones in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:352-356. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199909000-00005

7. Rothfield N. Clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Kelley WN, Harris ED, Ruddy S, Sledge CB (eds). Textbook of Rheumatology. WB Saunders; 1981.

8. Rus V, Maury EE, Hochberg MC. The epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Wallace DJ, Hahn BH (eds). Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002.

9. Biner B, Acunas B, Karasalihoglu S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy: a case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2001;43:94-96.

10. Gilmore R, Sin WY. Systemic lupus erythematosus mimicking lymphoma: the relevance of the clinical background in interpreting imaging studies. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013201802. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201802

11. Shrestha D, Dhakal AK, Shiva RK, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and granulomatous lymphadenopathy. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-179

12. Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M. The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Rheumatol Port. 2008;33:402-406.

13. Tamaki K, Morishima S, Nakachi S, et al. An atypical case of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with systemic lymphadenopathy and severe autoimmune thrombocytopenia/neutropenia mimicking malignant lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2017;105:526-531. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2126-8

14. Hyami T, Kato T, Moritani S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus with abdominal lymphadenopathy. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:342-344. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3589

15. Mull ES, Aranez V, Pierce D, et al. Newly diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus: atypical presentation with focal seizures and long-standing lymphadenopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:e109-e113. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000681

16. Kassan SS, Moss ML, Reddick RL. Progressive hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus on corticosteroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1382-1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197606172942506

17. Tuinman PR, Nieuwenhuis MB, Groen E, et al. A young woman with generalized lymphadenopathy. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Neth J Med. 2011;69:284-288.

1. Afzal W, Arab T, Ullah T, et al. Generalized lymphadenopathy as presenting features of systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and review of literature. J Clin Med Res. 2016;8:819-823. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2717w

2. Smith LW, Petri M. Diffuse lymphadenopathy as the presenting manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:397-399. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182a6a924

3. Petri M, Orbai A, Graciela S, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2677-2686. doi: 10.1002/art.34473

4. Kitsanou M, Adreopoulou E, Bai MK, et al. Extensive lymphadenopathy as the first clinical manifestation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9:140-143. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828037

5. Unlu O, Zuily S, Erkan D. The clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur J Rheumatol. 2016;3:75-84. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2015.0085

6. Lahita RG. The role of sex hormones in systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:352-356. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199909000-00005

7. Rothfield N. Clinical features of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Kelley WN, Harris ED, Ruddy S, Sledge CB (eds). Textbook of Rheumatology. WB Saunders; 1981.

8. Rus V, Maury EE, Hochberg MC. The epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Wallace DJ, Hahn BH (eds). Dubois’ Lupus Erythematosus. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2002.

9. Biner B, Acunas B, Karasalihoglu S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy: a case report. Turk J Pediatr. 2001;43:94-96.

10. Gilmore R, Sin WY. Systemic lupus erythematosus mimicking lymphoma: the relevance of the clinical background in interpreting imaging studies. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013201802. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-201802

11. Shrestha D, Dhakal AK, Shiva RK, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus and granulomatous lymphadenopathy. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:179. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-179

12. Melikoglu MA, Melikoglu M. The clinical importance of lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Acta Rheumatol Port. 2008;33:402-406.

13. Tamaki K, Morishima S, Nakachi S, et al. An atypical case of late-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with systemic lymphadenopathy and severe autoimmune thrombocytopenia/neutropenia mimicking malignant lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2017;105:526-531. doi: 10.1007/s12185-016-2126-8

14. Hyami T, Kato T, Moritani S, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus with abdominal lymphadenopathy. Eur J Dermatol. 2019;29:342-344. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2019.3589

15. Mull ES, Aranez V, Pierce D, et al. Newly diagnosed systemic lupus erythematosus: atypical presentation with focal seizures and long-standing lymphadenopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019;25:e109-e113. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000681

16. Kassan SS, Moss ML, Reddick RL. Progressive hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy in systemic lupus erythematosus on corticosteroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:1382-1383. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197606172942506

17. Tuinman PR, Nieuwenhuis MB, Groen E, et al. A young woman with generalized lymphadenopathy. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Neth J Med. 2011;69:284-288.

Atypical knee pain

An 83-year-old woman, with an otherwise noncontributory past medical history, presented with chronic right knee pain. Over the prior 4 years, she had undergone evaluation by an outside physician and received several corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid intra-articular injections, without symptom resolution. She described the pain as a 4/10 at rest and as “severe” when climbing stairs and exercising. The pain was localized to her lower back and right groin and extended to her right knee. She also said that she found it difficult to put on her socks. An outside orthopedic surgeon recommended right total knee arthroplasty, prompting her to seek a second opinion.

Examination of her right knee was unrevealing. However, during the hip examination, there was a pronounced loss of range of motion and concordant pain reproduction with the FABER (combined flexion, abduction, external rotation) and FADIR (combined flexion, adduction, and internal rotation) maneuvers.

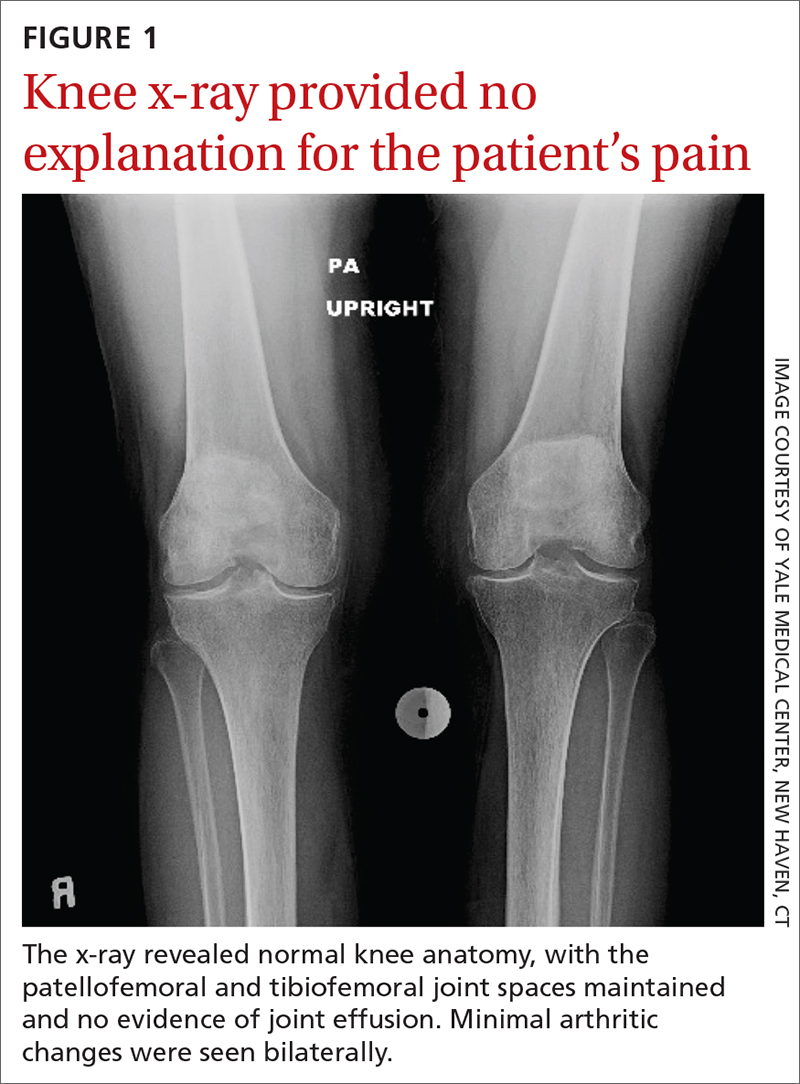

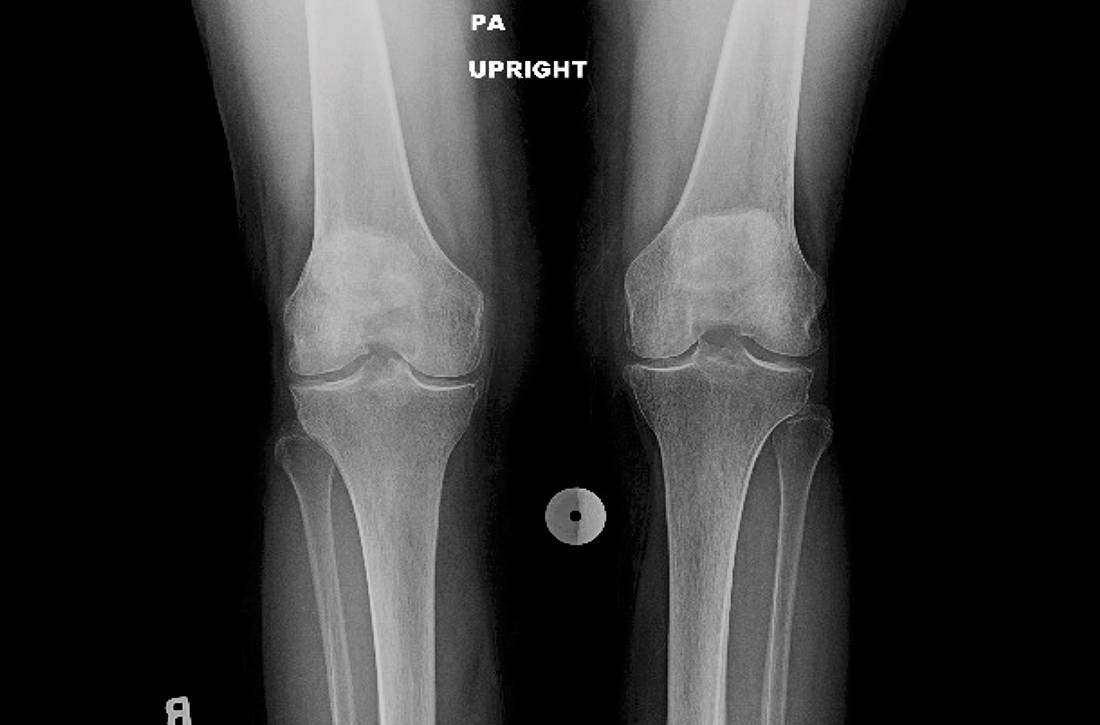

The patient’s extensive clinical and diagnostic history, combined with benign knee examination and imaging (FIGURE 1), ruled out isolated knee pathology.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

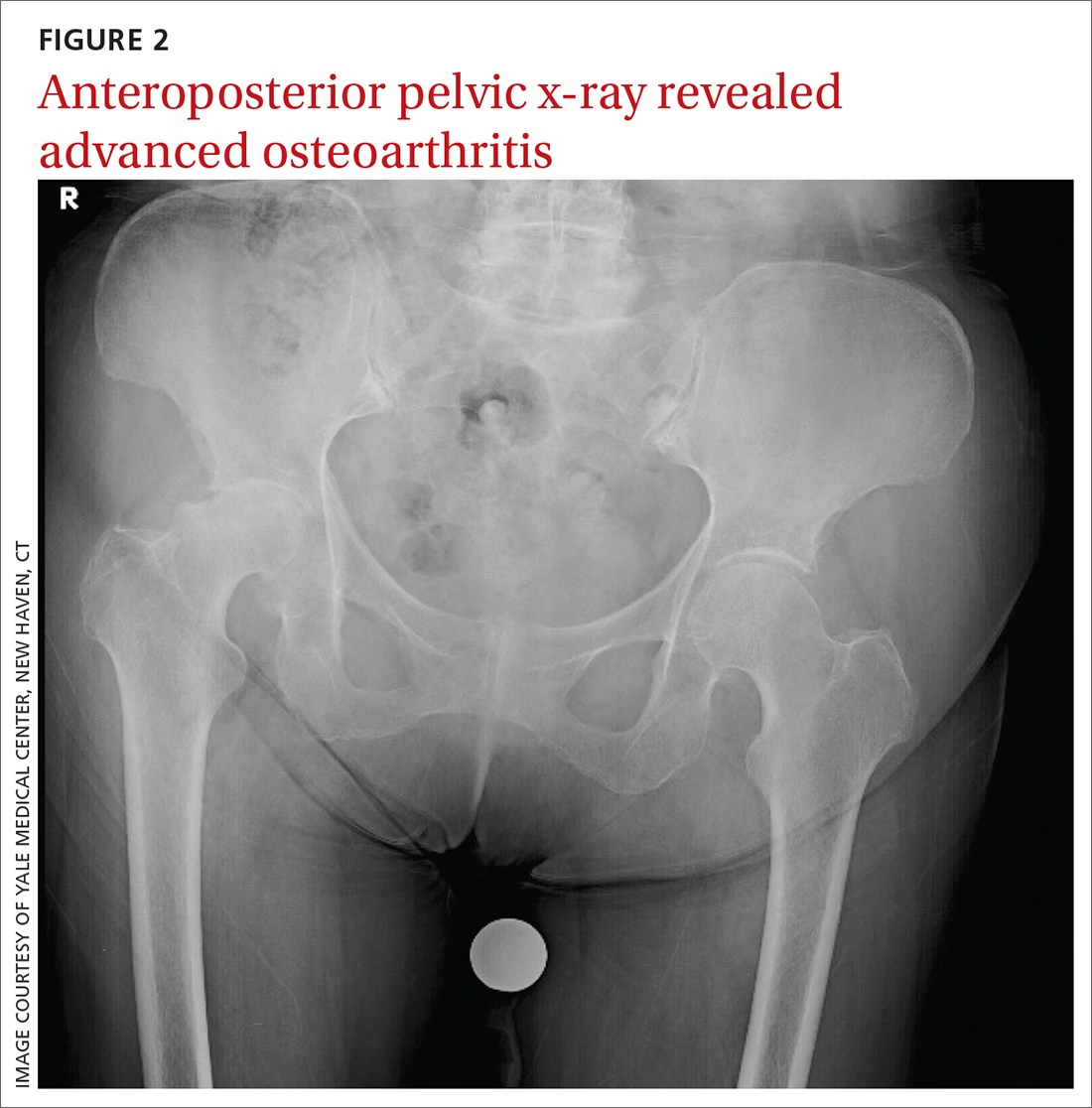

Dx: Right hip OA with referred knee pain

The patient’s history and physical exam prompted us to suspect right hip osteoarthritis (OA) with referred pain to the right knee. This suspicion was confirmed with hip radiographs (FIGURE 2), which revealed significant OA of the right hip, as evidenced by marked joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes. There was also superior migration of the right femoral head relative to the acetabulum. Additionally, there was loss of sphericity of the right femoral head, suggesting avascular necrosis with collapse.

Hip and knee OA are among the most common causes of disability worldwide. Knee and hip pain are estimated to affect up to 27% and 15% of the general population, respectively.1,2 Referred knee pain secondary to hip pathology, also known as atypical knee pain, has been cited at highly variable rates, ranging from 2% to 27%.3

Eighty-six percent of patients with atypical knee pain experience a delay in diagnosis of more than 1 year.4 Half of these patients require the use of a wheelchair or walker for community navigation.4 These findings highlight the impact that a delay in diagnosis can have on the day-to-day quality of life for these patients. Also, delayed or missed diagnoses may have contributed to the doubling in the rate of knee replacement surgery from 2000 to 2010 and the reports that up to one-third of knee replacement surgeries did not meet appropriate criteria to be performed.5,6

Convergence confusion

Referred pain is likely explained by the convergence of nociceptive and non-nociceptive nerve fibers.7 Both of these fiber types conduct action potentials that terminate at second order neurons. Occasionally, nociceptive nerve fibers from different parts of the body (ie, knee and hip) terminate at the same second order fiber. At this point of convergence, higher brain centers lose their ability to discriminate the anatomic location of origin. This results in the perception of pain in a different location, where there is no intrinsic pathology.

Patients with hip OA report that the most common locations of pain are the groin, anterior thigh, buttock, anterior knee, and greater trochanter.3 One small study revealed that 85% of patients with referred pain who underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) reported complete resolution of pain symptoms within 4 days of the procedure.3

Continue to: A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

A comprehensive exam can reveal a different origin of pain

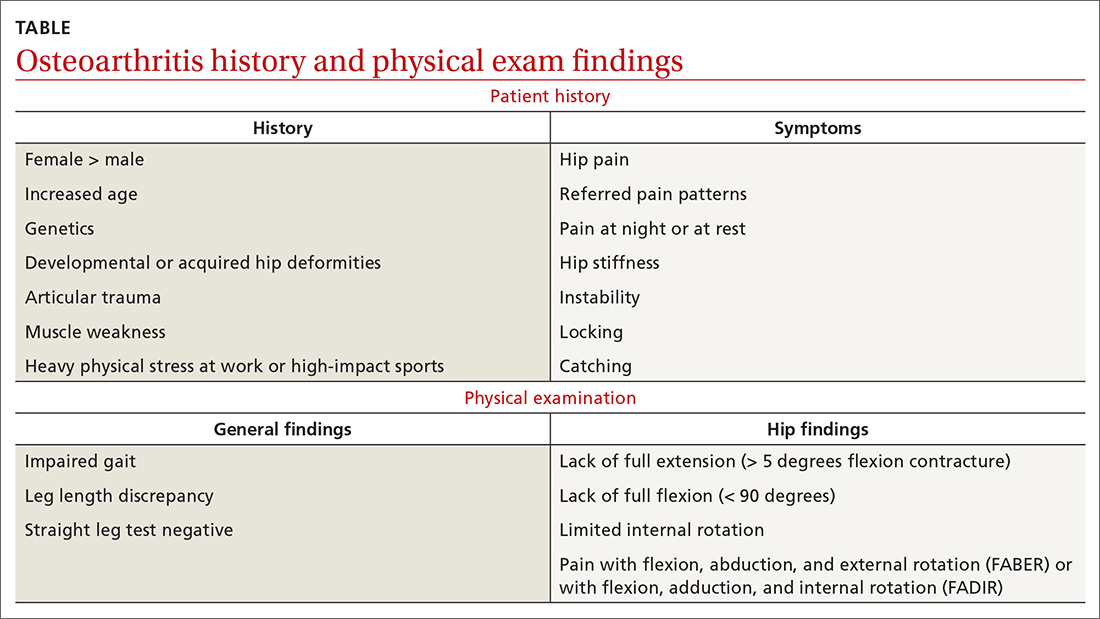

As with any musculoskeletal complaint, history and physical examination should include a focus on the joints proximal and distal to the purported joint of concern. When the hip is in consideration, historical inquiry should focus on degree and timeline of pain, stiffness, and traumatic history. Our patient reported difficulty donning socks, an excellent screening question to evaluate loss of range of motion in the hip. On physical examination, the FABER and FADIR maneuvers are quite specific to hip OA. A comprehensive list of history and physical examination findings can be found in the TABLE.

The differential includes a broad range of musculoskeletal diagnoses

The differential diagnosis for knee pain includes knee OA, spinopelvic pathology, infection, and rheumatologic disease.

Knee OA can be confirmed with knee radiographs, but one must also assess the joint above and below, as with all musculoskeletal complaints.

Spinopelvic pathology may be established with radiographs and a thorough nervous system exam.

Infection, such as septic arthritis or gout, can be diagnosed through radiographs, physical exam, and lab tests to evaluate white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels. High clinical suspicion may warrant a joint aspiration.

Continue to: Rheumatologic disease

Rheumatologic disease can be evaluated with a comprehensive physical exam, as well as lab work.

Management includes both surgical and nonsurgical options

Hip OA can be managed much like OA in other areas of the body. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International guidelines provide direction and insight concerning outpatient nonsurgical management.8 Weight loss and land-based, low-impact exercise programs are excellent first-line options. Second-line therapies include symptomatic management with systemic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in patients without contraindications. (Topical NSAIDs, while useful in the treatment of knee OA, are not as effective for hip OA due to thickness of soft tissue in this area of the body.)

Patients who do not achieve symptomatic relief with these first- and second-line therapies may benefit from other nonoperative measures, such as intra-articular corticosteroid injections. If pain persists, patients may need a referral to an orthopedic surgeon to discuss surgical candidacy.

Following the x-ray, our patient received a fluoroscopic guided intra-articular hip joint anesthetic and corticosteroid injection. Her pain level went from a reported6/10 prior to the procedure to complete pain relief after it.

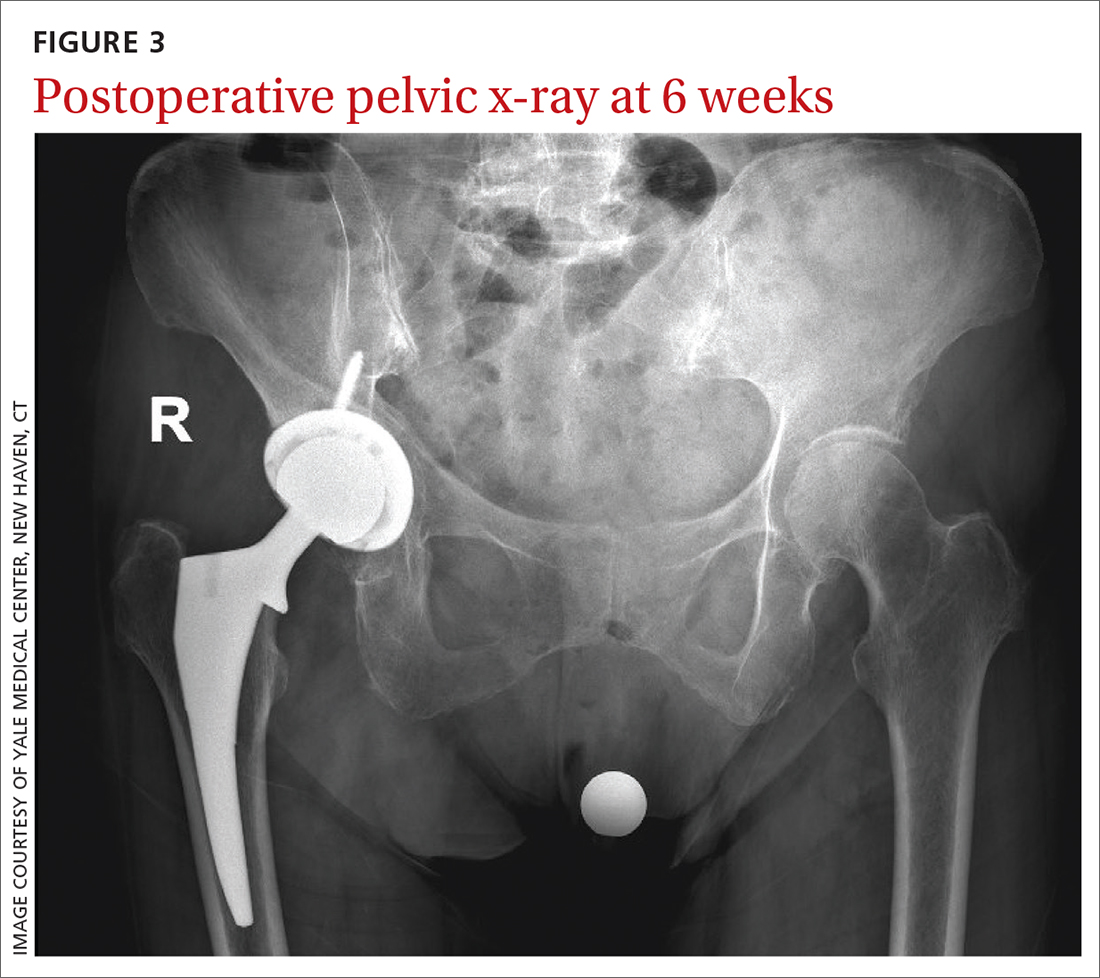

However, at her follow-up visit 4 weeks later, the patient reported return of functionally limiting pain. The orthopedic surgeon talked to the patient about the potential risks and benefits of THA. She elected to proceed with a right THA.

Six weeks after the surgery, the patient presented for follow-up with minimal hip pain and complete resolution of her knee pain (FIGURE 3). Functionally, she found it much easier to stand straight, and she was able to climb the stairs in her house independently.