User login

Ustekinumab becomes second biologic approved for PsA in kids

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the dual interleukin-12 and IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara) for the treatment of juvenile psoriatic arthritis (jPsA) in patients aged 6 years and older, according to an Aug. 1 announcement from its manufacturer, Janssen.

The approval makes jPsA the sixth approved indication for ustekinumab, which include active psoriatic arthritis in adults, moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in both adults and children aged 6 years or older who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy, moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease in adults, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in adults.

In addition, ustekinumab is now the second biologic to be approved for jPsA, following the agency’s December 2021 approval of secukinumab (Cosentyx) to treat jPsA in children and adolescents aged 2 years and older as well as enthesitis-related arthritis in children and adolescents aged 4 years and older.

In pediatric patients, ustekinumab is administered as a subcutaneous injection dosed four times per year after two starter doses.

Ustekinumab’s approval is based on “an extrapolation of the established data and existing safety profile” of ustekinumab in multiple phase 3 studies in adult and pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and adult patients with active PsA, according to Janssen.

“With the limited availability of pediatric patients for clinical trial inclusion, researchers can extrapolate data from trials with adults to determine the potential efficacy and tolerability of a treatment for a pediatric population,” according to the October 2021 announcement from the company that the Biologics License Application had been submitted to the FDA.

Juvenile arthritis occurs in an estimated 20-45 children per 100,000 in the United States, with about 5% of those children having jPsA, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The prescribing information for ustekinumab includes specific warnings and areas of concern. The drug should not be administered to individuals with known hypersensitivity to ustekinumab. The drug may lower the ability of the immune system to fight infections and may increase risk of infections, sometimes serious, and a test for tuberculosis infection should be given before administration.

Patients taking ustekinumab should not be given a live vaccine, and their doctors should be informed if anyone in their household needs a live vaccine. They also should not receive the BCG vaccine during the 1 year before receiving the drug or 1 year after they stop taking it, according to Johnson & Johnson.

The most common adverse effects include nasal congestion, sore throat, runny nose, upper respiratory infections, fever, headache, tiredness, itching, nausea and vomiting, redness at the injection site, vaginal yeast infections, urinary tract infections, sinus infection, bronchitis, diarrhea, stomach pain, and joint pain.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the dual interleukin-12 and IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara) for the treatment of juvenile psoriatic arthritis (jPsA) in patients aged 6 years and older, according to an Aug. 1 announcement from its manufacturer, Janssen.

The approval makes jPsA the sixth approved indication for ustekinumab, which include active psoriatic arthritis in adults, moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in both adults and children aged 6 years or older who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy, moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease in adults, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in adults.

In addition, ustekinumab is now the second biologic to be approved for jPsA, following the agency’s December 2021 approval of secukinumab (Cosentyx) to treat jPsA in children and adolescents aged 2 years and older as well as enthesitis-related arthritis in children and adolescents aged 4 years and older.

In pediatric patients, ustekinumab is administered as a subcutaneous injection dosed four times per year after two starter doses.

Ustekinumab’s approval is based on “an extrapolation of the established data and existing safety profile” of ustekinumab in multiple phase 3 studies in adult and pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and adult patients with active PsA, according to Janssen.

“With the limited availability of pediatric patients for clinical trial inclusion, researchers can extrapolate data from trials with adults to determine the potential efficacy and tolerability of a treatment for a pediatric population,” according to the October 2021 announcement from the company that the Biologics License Application had been submitted to the FDA.

Juvenile arthritis occurs in an estimated 20-45 children per 100,000 in the United States, with about 5% of those children having jPsA, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The prescribing information for ustekinumab includes specific warnings and areas of concern. The drug should not be administered to individuals with known hypersensitivity to ustekinumab. The drug may lower the ability of the immune system to fight infections and may increase risk of infections, sometimes serious, and a test for tuberculosis infection should be given before administration.

Patients taking ustekinumab should not be given a live vaccine, and their doctors should be informed if anyone in their household needs a live vaccine. They also should not receive the BCG vaccine during the 1 year before receiving the drug or 1 year after they stop taking it, according to Johnson & Johnson.

The most common adverse effects include nasal congestion, sore throat, runny nose, upper respiratory infections, fever, headache, tiredness, itching, nausea and vomiting, redness at the injection site, vaginal yeast infections, urinary tract infections, sinus infection, bronchitis, diarrhea, stomach pain, and joint pain.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the dual interleukin-12 and IL-23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara) for the treatment of juvenile psoriatic arthritis (jPsA) in patients aged 6 years and older, according to an Aug. 1 announcement from its manufacturer, Janssen.

The approval makes jPsA the sixth approved indication for ustekinumab, which include active psoriatic arthritis in adults, moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in both adults and children aged 6 years or older who are candidates for phototherapy or systemic therapy, moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease in adults, and moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis in adults.

In addition, ustekinumab is now the second biologic to be approved for jPsA, following the agency’s December 2021 approval of secukinumab (Cosentyx) to treat jPsA in children and adolescents aged 2 years and older as well as enthesitis-related arthritis in children and adolescents aged 4 years and older.

In pediatric patients, ustekinumab is administered as a subcutaneous injection dosed four times per year after two starter doses.

Ustekinumab’s approval is based on “an extrapolation of the established data and existing safety profile” of ustekinumab in multiple phase 3 studies in adult and pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis and adult patients with active PsA, according to Janssen.

“With the limited availability of pediatric patients for clinical trial inclusion, researchers can extrapolate data from trials with adults to determine the potential efficacy and tolerability of a treatment for a pediatric population,” according to the October 2021 announcement from the company that the Biologics License Application had been submitted to the FDA.

Juvenile arthritis occurs in an estimated 20-45 children per 100,000 in the United States, with about 5% of those children having jPsA, according to the National Psoriasis Foundation.

The prescribing information for ustekinumab includes specific warnings and areas of concern. The drug should not be administered to individuals with known hypersensitivity to ustekinumab. The drug may lower the ability of the immune system to fight infections and may increase risk of infections, sometimes serious, and a test for tuberculosis infection should be given before administration.

Patients taking ustekinumab should not be given a live vaccine, and their doctors should be informed if anyone in their household needs a live vaccine. They also should not receive the BCG vaccine during the 1 year before receiving the drug or 1 year after they stop taking it, according to Johnson & Johnson.

The most common adverse effects include nasal congestion, sore throat, runny nose, upper respiratory infections, fever, headache, tiredness, itching, nausea and vomiting, redness at the injection site, vaginal yeast infections, urinary tract infections, sinus infection, bronchitis, diarrhea, stomach pain, and joint pain.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D supplements do not lower risk of fractures

compared with placebo, according to results from an ancillary study of the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL).

The data showed that taking 2,000 IU of supplemental vitamin D each day without coadministered calcium did not have a significant effect on nonvertebral fractures (hazard ratio, 0.97; P = .50), hip fractures (HR, 1.01; P = .96), or total fractures (HR, 0.98; P = .70), compared with taking placebo, among individuals who did not have osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, or low bone mass, report Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief of the calcium and bone section at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and colleagues.

The findings were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prior randomized, controlled trials have presented conflicting findings. Some have shown that there is some benefit to supplemental vitamin D, whereas others have shown no effect or even harm with regard to risk of fractures, Dr. LeBoff noted.

“Because of the conflicting data at the time, we tested this hypothesis in an effort to advance science and understanding of the effects of vitamin D on bone. In a previous study, we did not see an effect of supplemental vitamin D on bone density in a subcohort from the VITAL trial,” Dr. LeBoff said in an interview.

“We previously reported that vitamin D, about 2,000 units per day, did not increase bone density, nor did it affect bone structure, according to PQCT [peripheral quantitative CT]. So that was an indicator that since bone density is a surrogate marker of fractures, there may not be an effect on fractures,” she added.

These results should dispel any idea that vitamin D alone could significantly reduce fracture rates in the general population, noted Steven R. Cummings, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and Clifford Rosen, MD, of Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, in an accompanying editorial.

“Adding those findings to previous reports from VITAL and other trials showing the lack of an effect for preventing numerous conditions suggests that providers should stop screening for 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels or recommending vitamin D supplements, and people should stop taking vitamin D supplements to prevent major diseases or extend life,” the editorialists wrote.

The researchers assessed 25,871 participants from all 50 states during a median follow-up time of 5.3 years. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive placebo or vitamin D.

The mean age of the participants was 67.1 years; 50.6% of the study cohort were women, and 20.2% of the cohort were Black. Participants did not have low bone mass, vitamin D deficiency, or osteoporosis.

Participants agreed not to supplement their dietary intake with more than 1,200 mg of calcium each day and no more than 800 IU of vitamin D each day.

Participants filled out detailed surveys to evaluate baseline prescription drug use, demographic factors, medical history, and the consumption of supplements, such as fish oil, calcium, and vitamin D, during the run-in stage. Yearly surveys were used to assess side effects, adherence to the investigation protocol, falls, fractures, physical activity, osteoporosis and associated risk factors, onset of major illness, and the use of nontrial prescription drugs and supplements, such as vitamin D and calcium.

The researchers adjudicated incident fracture data using a centralized medical record review. To approximate the therapeutic effect in intention-to-treat analyses, they used proportional-hazard models.

Notably, outcomes were similar for the placebo and vitamin D groups with regard to incident kidney stones and hypercalcemia.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation was not modified by baseline parameters such as race or ethnicity, sex, body mass index, age, or blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels.

Dr. Cummings and Dr. Rosen pointed out that these findings, along with other VITAL trial data, show that no subgroups classified on the basis of baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, including those with levels less than 20 ng/mL, benefited from vitamin supplementation.

“There is no justification for measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the general population or treating to a target serum level. A 25-hydroxyvitamin D level might be a useful diagnostic test for some patients with conditions that may be due to or that may cause severe deficiency,” the editorialists noted.

Except with regard to select patients, such as individuals living in nursing homes who have limited sun exposure, the use of the terms “vitamin D deficiency” and “vitamin D “insufficiency” should now be reevaluated, Dr. Rosen and Dr. Cummings wrote.

The study’s limitations include its assessment of only one dosage of vitamin D supplementation and a lack of adjustment for multiplicity, exploratory, parent trial, or secondary endpoints, the researchers noted.

The number of participants who had vitamin D deficiency was limited, owing to ethical and feasibility concerns regarding these patients. The data are not generalizable to individuals who are older and institutionalized or those who have osteomalacia or osteoporosis, the researchers wrote.

Expert commentary

“The interpretation of this [study] to me is that vitamin D is not for everybody,” said Baha Arafah, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and chief of the division of endocrinology at University Hospital, both in Cleveland, who was not involved in the study.

“This is not the final word; I would suggest that you don’t throw vitamin D at everybody. I would use markers of bone formation as a better measure to determine whether they need vitamin D or not, specifically looking at parathyroid hormone,” Dr. Arafah said in an interview.

Dr. Arafah pointed out that these data do not mean that clinicians should stop thinking about vitamin D altogether. “I think that would be the wrong message to read. If you read through the article, you will find that there are people who do need vitamin D; people who are deficient do need vitamin D. There’s no question that excessive or extreme vitamin D deficiency can lead to other things, specifically, osteomalacia, weak bones, [and] poor mineralization, so we are not totally out of the woods at this time.”

The ancillary study of the VITAL trial was sponsored by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Pharmavite donated the vitamin D 3 supplements used in the trial. Dr. LeBoff reported that she holds stock in Amgen. Cummings reported receiving personal fees and nonfinancial support from Amgen outside the submitted work. Dr. Rosen is associate editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Arafah reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with placebo, according to results from an ancillary study of the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL).

The data showed that taking 2,000 IU of supplemental vitamin D each day without coadministered calcium did not have a significant effect on nonvertebral fractures (hazard ratio, 0.97; P = .50), hip fractures (HR, 1.01; P = .96), or total fractures (HR, 0.98; P = .70), compared with taking placebo, among individuals who did not have osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, or low bone mass, report Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief of the calcium and bone section at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and colleagues.

The findings were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prior randomized, controlled trials have presented conflicting findings. Some have shown that there is some benefit to supplemental vitamin D, whereas others have shown no effect or even harm with regard to risk of fractures, Dr. LeBoff noted.

“Because of the conflicting data at the time, we tested this hypothesis in an effort to advance science and understanding of the effects of vitamin D on bone. In a previous study, we did not see an effect of supplemental vitamin D on bone density in a subcohort from the VITAL trial,” Dr. LeBoff said in an interview.

“We previously reported that vitamin D, about 2,000 units per day, did not increase bone density, nor did it affect bone structure, according to PQCT [peripheral quantitative CT]. So that was an indicator that since bone density is a surrogate marker of fractures, there may not be an effect on fractures,” she added.

These results should dispel any idea that vitamin D alone could significantly reduce fracture rates in the general population, noted Steven R. Cummings, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and Clifford Rosen, MD, of Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, in an accompanying editorial.

“Adding those findings to previous reports from VITAL and other trials showing the lack of an effect for preventing numerous conditions suggests that providers should stop screening for 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels or recommending vitamin D supplements, and people should stop taking vitamin D supplements to prevent major diseases or extend life,” the editorialists wrote.

The researchers assessed 25,871 participants from all 50 states during a median follow-up time of 5.3 years. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive placebo or vitamin D.

The mean age of the participants was 67.1 years; 50.6% of the study cohort were women, and 20.2% of the cohort were Black. Participants did not have low bone mass, vitamin D deficiency, or osteoporosis.

Participants agreed not to supplement their dietary intake with more than 1,200 mg of calcium each day and no more than 800 IU of vitamin D each day.

Participants filled out detailed surveys to evaluate baseline prescription drug use, demographic factors, medical history, and the consumption of supplements, such as fish oil, calcium, and vitamin D, during the run-in stage. Yearly surveys were used to assess side effects, adherence to the investigation protocol, falls, fractures, physical activity, osteoporosis and associated risk factors, onset of major illness, and the use of nontrial prescription drugs and supplements, such as vitamin D and calcium.

The researchers adjudicated incident fracture data using a centralized medical record review. To approximate the therapeutic effect in intention-to-treat analyses, they used proportional-hazard models.

Notably, outcomes were similar for the placebo and vitamin D groups with regard to incident kidney stones and hypercalcemia.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation was not modified by baseline parameters such as race or ethnicity, sex, body mass index, age, or blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels.

Dr. Cummings and Dr. Rosen pointed out that these findings, along with other VITAL trial data, show that no subgroups classified on the basis of baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, including those with levels less than 20 ng/mL, benefited from vitamin supplementation.

“There is no justification for measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the general population or treating to a target serum level. A 25-hydroxyvitamin D level might be a useful diagnostic test for some patients with conditions that may be due to or that may cause severe deficiency,” the editorialists noted.

Except with regard to select patients, such as individuals living in nursing homes who have limited sun exposure, the use of the terms “vitamin D deficiency” and “vitamin D “insufficiency” should now be reevaluated, Dr. Rosen and Dr. Cummings wrote.

The study’s limitations include its assessment of only one dosage of vitamin D supplementation and a lack of adjustment for multiplicity, exploratory, parent trial, or secondary endpoints, the researchers noted.

The number of participants who had vitamin D deficiency was limited, owing to ethical and feasibility concerns regarding these patients. The data are not generalizable to individuals who are older and institutionalized or those who have osteomalacia or osteoporosis, the researchers wrote.

Expert commentary

“The interpretation of this [study] to me is that vitamin D is not for everybody,” said Baha Arafah, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and chief of the division of endocrinology at University Hospital, both in Cleveland, who was not involved in the study.

“This is not the final word; I would suggest that you don’t throw vitamin D at everybody. I would use markers of bone formation as a better measure to determine whether they need vitamin D or not, specifically looking at parathyroid hormone,” Dr. Arafah said in an interview.

Dr. Arafah pointed out that these data do not mean that clinicians should stop thinking about vitamin D altogether. “I think that would be the wrong message to read. If you read through the article, you will find that there are people who do need vitamin D; people who are deficient do need vitamin D. There’s no question that excessive or extreme vitamin D deficiency can lead to other things, specifically, osteomalacia, weak bones, [and] poor mineralization, so we are not totally out of the woods at this time.”

The ancillary study of the VITAL trial was sponsored by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Pharmavite donated the vitamin D 3 supplements used in the trial. Dr. LeBoff reported that she holds stock in Amgen. Cummings reported receiving personal fees and nonfinancial support from Amgen outside the submitted work. Dr. Rosen is associate editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Arafah reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

compared with placebo, according to results from an ancillary study of the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL).

The data showed that taking 2,000 IU of supplemental vitamin D each day without coadministered calcium did not have a significant effect on nonvertebral fractures (hazard ratio, 0.97; P = .50), hip fractures (HR, 1.01; P = .96), or total fractures (HR, 0.98; P = .70), compared with taking placebo, among individuals who did not have osteoporosis, vitamin D deficiency, or low bone mass, report Meryl S. LeBoff, MD, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chief of the calcium and bone section at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and colleagues.

The findings were published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Prior randomized, controlled trials have presented conflicting findings. Some have shown that there is some benefit to supplemental vitamin D, whereas others have shown no effect or even harm with regard to risk of fractures, Dr. LeBoff noted.

“Because of the conflicting data at the time, we tested this hypothesis in an effort to advance science and understanding of the effects of vitamin D on bone. In a previous study, we did not see an effect of supplemental vitamin D on bone density in a subcohort from the VITAL trial,” Dr. LeBoff said in an interview.

“We previously reported that vitamin D, about 2,000 units per day, did not increase bone density, nor did it affect bone structure, according to PQCT [peripheral quantitative CT]. So that was an indicator that since bone density is a surrogate marker of fractures, there may not be an effect on fractures,” she added.

These results should dispel any idea that vitamin D alone could significantly reduce fracture rates in the general population, noted Steven R. Cummings, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, and Clifford Rosen, MD, of Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough, in an accompanying editorial.

“Adding those findings to previous reports from VITAL and other trials showing the lack of an effect for preventing numerous conditions suggests that providers should stop screening for 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels or recommending vitamin D supplements, and people should stop taking vitamin D supplements to prevent major diseases or extend life,” the editorialists wrote.

The researchers assessed 25,871 participants from all 50 states during a median follow-up time of 5.3 years. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive placebo or vitamin D.

The mean age of the participants was 67.1 years; 50.6% of the study cohort were women, and 20.2% of the cohort were Black. Participants did not have low bone mass, vitamin D deficiency, or osteoporosis.

Participants agreed not to supplement their dietary intake with more than 1,200 mg of calcium each day and no more than 800 IU of vitamin D each day.

Participants filled out detailed surveys to evaluate baseline prescription drug use, demographic factors, medical history, and the consumption of supplements, such as fish oil, calcium, and vitamin D, during the run-in stage. Yearly surveys were used to assess side effects, adherence to the investigation protocol, falls, fractures, physical activity, osteoporosis and associated risk factors, onset of major illness, and the use of nontrial prescription drugs and supplements, such as vitamin D and calcium.

The researchers adjudicated incident fracture data using a centralized medical record review. To approximate the therapeutic effect in intention-to-treat analyses, they used proportional-hazard models.

Notably, outcomes were similar for the placebo and vitamin D groups with regard to incident kidney stones and hypercalcemia.

The effect of vitamin D supplementation was not modified by baseline parameters such as race or ethnicity, sex, body mass index, age, or blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels.

Dr. Cummings and Dr. Rosen pointed out that these findings, along with other VITAL trial data, show that no subgroups classified on the basis of baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels, including those with levels less than 20 ng/mL, benefited from vitamin supplementation.

“There is no justification for measuring 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the general population or treating to a target serum level. A 25-hydroxyvitamin D level might be a useful diagnostic test for some patients with conditions that may be due to or that may cause severe deficiency,” the editorialists noted.

Except with regard to select patients, such as individuals living in nursing homes who have limited sun exposure, the use of the terms “vitamin D deficiency” and “vitamin D “insufficiency” should now be reevaluated, Dr. Rosen and Dr. Cummings wrote.

The study’s limitations include its assessment of only one dosage of vitamin D supplementation and a lack of adjustment for multiplicity, exploratory, parent trial, or secondary endpoints, the researchers noted.

The number of participants who had vitamin D deficiency was limited, owing to ethical and feasibility concerns regarding these patients. The data are not generalizable to individuals who are older and institutionalized or those who have osteomalacia or osteoporosis, the researchers wrote.

Expert commentary

“The interpretation of this [study] to me is that vitamin D is not for everybody,” said Baha Arafah, MD, professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University and chief of the division of endocrinology at University Hospital, both in Cleveland, who was not involved in the study.

“This is not the final word; I would suggest that you don’t throw vitamin D at everybody. I would use markers of bone formation as a better measure to determine whether they need vitamin D or not, specifically looking at parathyroid hormone,” Dr. Arafah said in an interview.

Dr. Arafah pointed out that these data do not mean that clinicians should stop thinking about vitamin D altogether. “I think that would be the wrong message to read. If you read through the article, you will find that there are people who do need vitamin D; people who are deficient do need vitamin D. There’s no question that excessive or extreme vitamin D deficiency can lead to other things, specifically, osteomalacia, weak bones, [and] poor mineralization, so we are not totally out of the woods at this time.”

The ancillary study of the VITAL trial was sponsored by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Pharmavite donated the vitamin D 3 supplements used in the trial. Dr. LeBoff reported that she holds stock in Amgen. Cummings reported receiving personal fees and nonfinancial support from Amgen outside the submitted work. Dr. Rosen is associate editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. Dr. Arafah reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Uveitis in juvenile arthritis patients persists into midlife

Active uveitis remained in 43.4% of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients up to 40 years after a diagnosis, based on data from 30 individuals.

Uveitis occurs in approximately 10%-20% of patients with JIA, but data on the long-term activity and prevalence are limited, although previous studies suggest that uveitis can persist into adulthood, wrote Dr. Angelika Skarin of Skåne University in Lund, Sweden, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatric Rheumatology, the researchers reviewed ophthalmic records from 30 JIA patients at a mean of 40.7 years after uveitis onset. They compared these records to data collected from the same patient population at a mean of 7.2 and 24.0 years after onset. In the previous follow-up studies, 49% of the patients had active uveitis at 24 years, and the prevalence of cataracts and glaucoma increased between the 7-year and 24-year assessments.

In the current study, 43.4% of the population had active uveitis at the 40-year follow-up, which corresponded to 23.6% of the original study cohort. The mean age of the participants overall was 46.9 years, the mean duration of joint disease was 42.99 years, and the mean time from onset of uveitis was 40.7 years.

In addition, 66.6% of the patients in the current study had cataracts or had undergone cataract surgery in one or both eyes, and 40.0% had glaucoma.

By the time of the current study, of the original cohort of 55 individuals, 11 were deceased; rheumatic disease was declared the main cause in four patients and a contributing factor in three others.

Potential drivers of the earliest cases of glaucoma and ocular hypertension (G/OH) include increased intraocular pressure as a result of topical corticosteroid treatment, the researchers noted in their discussion. However, G/OH occurring later than the 7-year follow-up was “more likely to be the type observed in many patients with long-standing chronic uveitis, where a gradual increase in intraocular pressure is assumed to be caused by impaired aqueous outflow,” they said.

Only 4 of the 30 patients did not have regular ophthalmology visits, which suggests a study population with ocular symptoms or concerns about their eyesight, the researchers wrote. “The fact that 13% of our original cohort were reported to have severe visual impairment or worse in both eyes at any of the three follow-ups is noteworthy,” compared to reports of visual impairment of less than 0.5% in a German study in the general population for similar ages.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design, small study population, and lack of data on 25 of the original 55-member study cohort, which may reduce the reliability of the current study, the researchers noted. However, the results reflect data from previous studies and support the need for JIA patients to continue regular ophthalmic checkups throughout life, they concluded.

The study was supported by Stiftelsen för Synskadade i f.d. Malmöhus län, Sweden, Skånes Universitetssjukhus Stiftelser och Donationer, Ögonfonden, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Active uveitis remained in 43.4% of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients up to 40 years after a diagnosis, based on data from 30 individuals.

Uveitis occurs in approximately 10%-20% of patients with JIA, but data on the long-term activity and prevalence are limited, although previous studies suggest that uveitis can persist into adulthood, wrote Dr. Angelika Skarin of Skåne University in Lund, Sweden, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatric Rheumatology, the researchers reviewed ophthalmic records from 30 JIA patients at a mean of 40.7 years after uveitis onset. They compared these records to data collected from the same patient population at a mean of 7.2 and 24.0 years after onset. In the previous follow-up studies, 49% of the patients had active uveitis at 24 years, and the prevalence of cataracts and glaucoma increased between the 7-year and 24-year assessments.

In the current study, 43.4% of the population had active uveitis at the 40-year follow-up, which corresponded to 23.6% of the original study cohort. The mean age of the participants overall was 46.9 years, the mean duration of joint disease was 42.99 years, and the mean time from onset of uveitis was 40.7 years.

In addition, 66.6% of the patients in the current study had cataracts or had undergone cataract surgery in one or both eyes, and 40.0% had glaucoma.

By the time of the current study, of the original cohort of 55 individuals, 11 were deceased; rheumatic disease was declared the main cause in four patients and a contributing factor in three others.

Potential drivers of the earliest cases of glaucoma and ocular hypertension (G/OH) include increased intraocular pressure as a result of topical corticosteroid treatment, the researchers noted in their discussion. However, G/OH occurring later than the 7-year follow-up was “more likely to be the type observed in many patients with long-standing chronic uveitis, where a gradual increase in intraocular pressure is assumed to be caused by impaired aqueous outflow,” they said.

Only 4 of the 30 patients did not have regular ophthalmology visits, which suggests a study population with ocular symptoms or concerns about their eyesight, the researchers wrote. “The fact that 13% of our original cohort were reported to have severe visual impairment or worse in both eyes at any of the three follow-ups is noteworthy,” compared to reports of visual impairment of less than 0.5% in a German study in the general population for similar ages.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design, small study population, and lack of data on 25 of the original 55-member study cohort, which may reduce the reliability of the current study, the researchers noted. However, the results reflect data from previous studies and support the need for JIA patients to continue regular ophthalmic checkups throughout life, they concluded.

The study was supported by Stiftelsen för Synskadade i f.d. Malmöhus län, Sweden, Skånes Universitetssjukhus Stiftelser och Donationer, Ögonfonden, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Active uveitis remained in 43.4% of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) patients up to 40 years after a diagnosis, based on data from 30 individuals.

Uveitis occurs in approximately 10%-20% of patients with JIA, but data on the long-term activity and prevalence are limited, although previous studies suggest that uveitis can persist into adulthood, wrote Dr. Angelika Skarin of Skåne University in Lund, Sweden, and colleagues.

In a study published in Pediatric Rheumatology, the researchers reviewed ophthalmic records from 30 JIA patients at a mean of 40.7 years after uveitis onset. They compared these records to data collected from the same patient population at a mean of 7.2 and 24.0 years after onset. In the previous follow-up studies, 49% of the patients had active uveitis at 24 years, and the prevalence of cataracts and glaucoma increased between the 7-year and 24-year assessments.

In the current study, 43.4% of the population had active uveitis at the 40-year follow-up, which corresponded to 23.6% of the original study cohort. The mean age of the participants overall was 46.9 years, the mean duration of joint disease was 42.99 years, and the mean time from onset of uveitis was 40.7 years.

In addition, 66.6% of the patients in the current study had cataracts or had undergone cataract surgery in one or both eyes, and 40.0% had glaucoma.

By the time of the current study, of the original cohort of 55 individuals, 11 were deceased; rheumatic disease was declared the main cause in four patients and a contributing factor in three others.

Potential drivers of the earliest cases of glaucoma and ocular hypertension (G/OH) include increased intraocular pressure as a result of topical corticosteroid treatment, the researchers noted in their discussion. However, G/OH occurring later than the 7-year follow-up was “more likely to be the type observed in many patients with long-standing chronic uveitis, where a gradual increase in intraocular pressure is assumed to be caused by impaired aqueous outflow,” they said.

Only 4 of the 30 patients did not have regular ophthalmology visits, which suggests a study population with ocular symptoms or concerns about their eyesight, the researchers wrote. “The fact that 13% of our original cohort were reported to have severe visual impairment or worse in both eyes at any of the three follow-ups is noteworthy,” compared to reports of visual impairment of less than 0.5% in a German study in the general population for similar ages.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the retrospective design, small study population, and lack of data on 25 of the original 55-member study cohort, which may reduce the reliability of the current study, the researchers noted. However, the results reflect data from previous studies and support the need for JIA patients to continue regular ophthalmic checkups throughout life, they concluded.

The study was supported by Stiftelsen för Synskadade i f.d. Malmöhus län, Sweden, Skånes Universitetssjukhus Stiftelser och Donationer, Ögonfonden, and the Swedish Society of Medicine. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PEDIATRIC RHEUMATOLOGY

No more ‘escape hatch’: Post Roe, new worries about meds linked to birth defects

As states ban or limit abortion in the wake of the demise of Roe v. Wade, physicians are turning their attention to widely-used drugs that can cause birth defects. At issue: Should these drugs still be prescribed to women of childbearing age if they don’t have the option of terminating their pregnancies?

“Doctors are going to understandably be terrified that a patient may become pregnant using a teratogen that they have prescribed,” said University of Pittsburgh rheumatologist Mehret Birru Talabi, MD, PhD, who works in a state where the future of abortion rights is uncertain. “While this was a feared outcome before Roe v. Wade was overturned, abortion provided an escape hatch by which women could avoid having to continue a pregnancy and potentially raise a child with congenital anomalies. I believe that prescribing is going to become much more defensive and conservative. Some clinicians may choose not to prescribe these medications to patients who have childbearing potential, even if they don’t have much risk for pregnancy.”

Other physicians expressed similar concerns in interviews. Duke University, Durham, N.C., rheumatologist Megan E. B. Clowse, MD, MPH, fears that physicians will be wary of prescribing a variety of medications – including new ones for which there are few pregnancy data – if abortion is unavailable. “Women who receive these new or teratogenic medications will likely lose their reproductive autonomy and be forced to choose between having sexual relationships with men, obtaining procedures that make them permanently sterile, or using contraception that may cause intolerable side effects,” she said. “I am very concerned that young women with rheumatic disease will now be left with active disease resulting in joint damage and renal failure.”

Abortion is now banned in at least six states, according to The New York Times. That number may rise to 16 as more restrictions become law. Another five states aren’t expected to ban abortion soon but have implemented gestational age limits on abortion or are expected to adopt them. In another nine states, courts or lawmakers will decide whether abortion remains legal.

Only 20 states and the District of Columbia have firm abortion protections in place.

Numerous drugs are considered teratogens, which means they may cause birth defects. Thalidomide is the most infamous, but there are many more, including several used in rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology. Among the most widely used teratogenic medications are the acne drugs isotretinoin and methotrexate, which are used to treat a variety of conditions, such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.

Dr. Clowse, who helps manage an industry-supported website devoted to reproductive care for women with lupus (www.LupusPregnancy.org), noted that several drugs linked to birth defects and pregnancy loss are commonly prescribed in rheumatology.

“Methotrexate is the most common medication and has been the cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis [treatment] for at least two decades,” she said. “Mycophenolate is our best medication to treat lupus nephritis, which is inflammation in the kidneys caused by lupus. This is a common complication for young women with lupus, and all of our guideline-recommended treatment regimens include a medication that causes pregnancy loss and birth defects, either mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide.”

Rheumatologists also prescribe a large number of new drugs for which there are few data about pregnancy risks. “It typically takes about two decades to have sufficient data about the safety of our medications,” she said.

Reflecting the sensitivity of the topic, Dr. Clowse made clear that her opinions don’t represent the views of her institution. She works in North Carolina, where the fate of abortion rights is uncertain, according to The New York Times.

What about alternatives? “The short answer is that some of these medications work really well and sometimes much better than the nonteratogenic alternatives,” said Dr. Birru Talabi. “I’m worried about methotrexate. It has been used to induce abortions but is primarily used in the United States as a highly effective treatment for cancer as well as a myriad of rheumatic diseases. If legislators try to restrict access to methotrexate, we may see increasing disability and even death among people who need this medication but cannot access it.”

Rheumatologists aren’t the only physicians who are worrying about the fates of their patients in a new era of abortion restrictions. Gastroenterologist Sunanda Kane, MD, MSPH, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said several teratogenic medications are used in her field to treat constipation, viral hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

“When treating women of childbearing age, there are usually alternatives. If we do prescribe a medication with a high teratogenic potential, we counsel and document that we have discussed two forms of birth control to avoid pregnancy. We usually do not prescribe a drug with teratogenic potential with the ‘out’ being an abortion if a pregnancy does occur,” she said. However, “if abortion is not even on the table as an option, we may be much less likely to prescribe these medications. This will be particularly true in patients who clearly do not have the means to travel to have an abortion in any situation.”

Abortion is expected to remain legal in Minnesota, where Dr. Kane practices, but it may be restricted or banned in nearby Wisconsin, depending on the state legislature. None of her patients have had abortions after becoming pregnant while taking the medications, she said, although she “did have a patient who because of her religious faith did not have an abortion after exposure and ended up with a stillbirth.”

The crackdown on abortion won’t just pose risks to patients who take potentially dangerous medications, physicians said. Dr. Kane said pregnancy itself is a significant risk for patients with “very active, uncontrolled gastrointestinal conditions where a pregnancy could be harmful to the mother’s health or result in offspring that are very unhealthy.” These include decompensated cirrhosis, uncontrolled Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, refractory gastroparesis, uncontrolled celiac sprue, and chronic pancreatitis, she said.

“There have been times when after shared decisionmaking, a patient with very active inflammatory bowel disease has decided to terminate the pregnancy because of her own ongoing health issues,” she said. “Not having this option will potentially lead to disastrous results.”

Dr. Clowse, the Duke University rheumatologist, echoed Dr. Kane’s concerns about women who are too sick to bear children. “The removal of abortion rights puts the lives and quality of life for women with rheumatic disease at risk. For patients with lupus and other systemic rheumatic disease, pregnancy can be medically catastrophic, leading to permanent harm and even death to the woman and her offspring. I am worried that women in these conditions will die without lifesaving pregnancy terminations, due to worries about the legal consequences for their physicians.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade has also raised the prospect that the court could ultimately allow birth control to be restricted or outlawed.

While the ruling states that “nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurrence in which he said that the court should reconsider a 1960s ruling that forbids the banning of contraceptives. Republicans have dismissed concerns about bans being allowed, although Democrats, including the president and vice president, starkly warn that they could happen.

“If we as providers have to be concerned that there will be an unplanned pregnancy because of the lack of access to contraception,” Dr. Kane said, “this will have significant downstream consequences to the kind of care we can provide and might just drive some providers to not give care to female patients at all given this concern.”

The physicians quoted in this article report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As states ban or limit abortion in the wake of the demise of Roe v. Wade, physicians are turning their attention to widely-used drugs that can cause birth defects. At issue: Should these drugs still be prescribed to women of childbearing age if they don’t have the option of terminating their pregnancies?

“Doctors are going to understandably be terrified that a patient may become pregnant using a teratogen that they have prescribed,” said University of Pittsburgh rheumatologist Mehret Birru Talabi, MD, PhD, who works in a state where the future of abortion rights is uncertain. “While this was a feared outcome before Roe v. Wade was overturned, abortion provided an escape hatch by which women could avoid having to continue a pregnancy and potentially raise a child with congenital anomalies. I believe that prescribing is going to become much more defensive and conservative. Some clinicians may choose not to prescribe these medications to patients who have childbearing potential, even if they don’t have much risk for pregnancy.”

Other physicians expressed similar concerns in interviews. Duke University, Durham, N.C., rheumatologist Megan E. B. Clowse, MD, MPH, fears that physicians will be wary of prescribing a variety of medications – including new ones for which there are few pregnancy data – if abortion is unavailable. “Women who receive these new or teratogenic medications will likely lose their reproductive autonomy and be forced to choose between having sexual relationships with men, obtaining procedures that make them permanently sterile, or using contraception that may cause intolerable side effects,” she said. “I am very concerned that young women with rheumatic disease will now be left with active disease resulting in joint damage and renal failure.”

Abortion is now banned in at least six states, according to The New York Times. That number may rise to 16 as more restrictions become law. Another five states aren’t expected to ban abortion soon but have implemented gestational age limits on abortion or are expected to adopt them. In another nine states, courts or lawmakers will decide whether abortion remains legal.

Only 20 states and the District of Columbia have firm abortion protections in place.

Numerous drugs are considered teratogens, which means they may cause birth defects. Thalidomide is the most infamous, but there are many more, including several used in rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology. Among the most widely used teratogenic medications are the acne drugs isotretinoin and methotrexate, which are used to treat a variety of conditions, such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.

Dr. Clowse, who helps manage an industry-supported website devoted to reproductive care for women with lupus (www.LupusPregnancy.org), noted that several drugs linked to birth defects and pregnancy loss are commonly prescribed in rheumatology.

“Methotrexate is the most common medication and has been the cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis [treatment] for at least two decades,” she said. “Mycophenolate is our best medication to treat lupus nephritis, which is inflammation in the kidneys caused by lupus. This is a common complication for young women with lupus, and all of our guideline-recommended treatment regimens include a medication that causes pregnancy loss and birth defects, either mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide.”

Rheumatologists also prescribe a large number of new drugs for which there are few data about pregnancy risks. “It typically takes about two decades to have sufficient data about the safety of our medications,” she said.

Reflecting the sensitivity of the topic, Dr. Clowse made clear that her opinions don’t represent the views of her institution. She works in North Carolina, where the fate of abortion rights is uncertain, according to The New York Times.

What about alternatives? “The short answer is that some of these medications work really well and sometimes much better than the nonteratogenic alternatives,” said Dr. Birru Talabi. “I’m worried about methotrexate. It has been used to induce abortions but is primarily used in the United States as a highly effective treatment for cancer as well as a myriad of rheumatic diseases. If legislators try to restrict access to methotrexate, we may see increasing disability and even death among people who need this medication but cannot access it.”

Rheumatologists aren’t the only physicians who are worrying about the fates of their patients in a new era of abortion restrictions. Gastroenterologist Sunanda Kane, MD, MSPH, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said several teratogenic medications are used in her field to treat constipation, viral hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

“When treating women of childbearing age, there are usually alternatives. If we do prescribe a medication with a high teratogenic potential, we counsel and document that we have discussed two forms of birth control to avoid pregnancy. We usually do not prescribe a drug with teratogenic potential with the ‘out’ being an abortion if a pregnancy does occur,” she said. However, “if abortion is not even on the table as an option, we may be much less likely to prescribe these medications. This will be particularly true in patients who clearly do not have the means to travel to have an abortion in any situation.”

Abortion is expected to remain legal in Minnesota, where Dr. Kane practices, but it may be restricted or banned in nearby Wisconsin, depending on the state legislature. None of her patients have had abortions after becoming pregnant while taking the medications, she said, although she “did have a patient who because of her religious faith did not have an abortion after exposure and ended up with a stillbirth.”

The crackdown on abortion won’t just pose risks to patients who take potentially dangerous medications, physicians said. Dr. Kane said pregnancy itself is a significant risk for patients with “very active, uncontrolled gastrointestinal conditions where a pregnancy could be harmful to the mother’s health or result in offspring that are very unhealthy.” These include decompensated cirrhosis, uncontrolled Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, refractory gastroparesis, uncontrolled celiac sprue, and chronic pancreatitis, she said.

“There have been times when after shared decisionmaking, a patient with very active inflammatory bowel disease has decided to terminate the pregnancy because of her own ongoing health issues,” she said. “Not having this option will potentially lead to disastrous results.”

Dr. Clowse, the Duke University rheumatologist, echoed Dr. Kane’s concerns about women who are too sick to bear children. “The removal of abortion rights puts the lives and quality of life for women with rheumatic disease at risk. For patients with lupus and other systemic rheumatic disease, pregnancy can be medically catastrophic, leading to permanent harm and even death to the woman and her offspring. I am worried that women in these conditions will die without lifesaving pregnancy terminations, due to worries about the legal consequences for their physicians.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade has also raised the prospect that the court could ultimately allow birth control to be restricted or outlawed.

While the ruling states that “nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurrence in which he said that the court should reconsider a 1960s ruling that forbids the banning of contraceptives. Republicans have dismissed concerns about bans being allowed, although Democrats, including the president and vice president, starkly warn that they could happen.

“If we as providers have to be concerned that there will be an unplanned pregnancy because of the lack of access to contraception,” Dr. Kane said, “this will have significant downstream consequences to the kind of care we can provide and might just drive some providers to not give care to female patients at all given this concern.”

The physicians quoted in this article report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As states ban or limit abortion in the wake of the demise of Roe v. Wade, physicians are turning their attention to widely-used drugs that can cause birth defects. At issue: Should these drugs still be prescribed to women of childbearing age if they don’t have the option of terminating their pregnancies?

“Doctors are going to understandably be terrified that a patient may become pregnant using a teratogen that they have prescribed,” said University of Pittsburgh rheumatologist Mehret Birru Talabi, MD, PhD, who works in a state where the future of abortion rights is uncertain. “While this was a feared outcome before Roe v. Wade was overturned, abortion provided an escape hatch by which women could avoid having to continue a pregnancy and potentially raise a child with congenital anomalies. I believe that prescribing is going to become much more defensive and conservative. Some clinicians may choose not to prescribe these medications to patients who have childbearing potential, even if they don’t have much risk for pregnancy.”

Other physicians expressed similar concerns in interviews. Duke University, Durham, N.C., rheumatologist Megan E. B. Clowse, MD, MPH, fears that physicians will be wary of prescribing a variety of medications – including new ones for which there are few pregnancy data – if abortion is unavailable. “Women who receive these new or teratogenic medications will likely lose their reproductive autonomy and be forced to choose between having sexual relationships with men, obtaining procedures that make them permanently sterile, or using contraception that may cause intolerable side effects,” she said. “I am very concerned that young women with rheumatic disease will now be left with active disease resulting in joint damage and renal failure.”

Abortion is now banned in at least six states, according to The New York Times. That number may rise to 16 as more restrictions become law. Another five states aren’t expected to ban abortion soon but have implemented gestational age limits on abortion or are expected to adopt them. In another nine states, courts or lawmakers will decide whether abortion remains legal.

Only 20 states and the District of Columbia have firm abortion protections in place.

Numerous drugs are considered teratogens, which means they may cause birth defects. Thalidomide is the most infamous, but there are many more, including several used in rheumatology, dermatology, and gastroenterology. Among the most widely used teratogenic medications are the acne drugs isotretinoin and methotrexate, which are used to treat a variety of conditions, such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis.

Dr. Clowse, who helps manage an industry-supported website devoted to reproductive care for women with lupus (www.LupusPregnancy.org), noted that several drugs linked to birth defects and pregnancy loss are commonly prescribed in rheumatology.

“Methotrexate is the most common medication and has been the cornerstone of rheumatoid arthritis [treatment] for at least two decades,” she said. “Mycophenolate is our best medication to treat lupus nephritis, which is inflammation in the kidneys caused by lupus. This is a common complication for young women with lupus, and all of our guideline-recommended treatment regimens include a medication that causes pregnancy loss and birth defects, either mycophenolate or cyclophosphamide.”

Rheumatologists also prescribe a large number of new drugs for which there are few data about pregnancy risks. “It typically takes about two decades to have sufficient data about the safety of our medications,” she said.

Reflecting the sensitivity of the topic, Dr. Clowse made clear that her opinions don’t represent the views of her institution. She works in North Carolina, where the fate of abortion rights is uncertain, according to The New York Times.

What about alternatives? “The short answer is that some of these medications work really well and sometimes much better than the nonteratogenic alternatives,” said Dr. Birru Talabi. “I’m worried about methotrexate. It has been used to induce abortions but is primarily used in the United States as a highly effective treatment for cancer as well as a myriad of rheumatic diseases. If legislators try to restrict access to methotrexate, we may see increasing disability and even death among people who need this medication but cannot access it.”

Rheumatologists aren’t the only physicians who are worrying about the fates of their patients in a new era of abortion restrictions. Gastroenterologist Sunanda Kane, MD, MSPH, of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said several teratogenic medications are used in her field to treat constipation, viral hepatitis, and inflammatory bowel disease.

“When treating women of childbearing age, there are usually alternatives. If we do prescribe a medication with a high teratogenic potential, we counsel and document that we have discussed two forms of birth control to avoid pregnancy. We usually do not prescribe a drug with teratogenic potential with the ‘out’ being an abortion if a pregnancy does occur,” she said. However, “if abortion is not even on the table as an option, we may be much less likely to prescribe these medications. This will be particularly true in patients who clearly do not have the means to travel to have an abortion in any situation.”

Abortion is expected to remain legal in Minnesota, where Dr. Kane practices, but it may be restricted or banned in nearby Wisconsin, depending on the state legislature. None of her patients have had abortions after becoming pregnant while taking the medications, she said, although she “did have a patient who because of her religious faith did not have an abortion after exposure and ended up with a stillbirth.”

The crackdown on abortion won’t just pose risks to patients who take potentially dangerous medications, physicians said. Dr. Kane said pregnancy itself is a significant risk for patients with “very active, uncontrolled gastrointestinal conditions where a pregnancy could be harmful to the mother’s health or result in offspring that are very unhealthy.” These include decompensated cirrhosis, uncontrolled Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, refractory gastroparesis, uncontrolled celiac sprue, and chronic pancreatitis, she said.

“There have been times when after shared decisionmaking, a patient with very active inflammatory bowel disease has decided to terminate the pregnancy because of her own ongoing health issues,” she said. “Not having this option will potentially lead to disastrous results.”

Dr. Clowse, the Duke University rheumatologist, echoed Dr. Kane’s concerns about women who are too sick to bear children. “The removal of abortion rights puts the lives and quality of life for women with rheumatic disease at risk. For patients with lupus and other systemic rheumatic disease, pregnancy can be medically catastrophic, leading to permanent harm and even death to the woman and her offspring. I am worried that women in these conditions will die without lifesaving pregnancy terminations, due to worries about the legal consequences for their physicians.”

The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that overturned Roe v. Wade has also raised the prospect that the court could ultimately allow birth control to be restricted or outlawed.

While the ruling states that “nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurrence in which he said that the court should reconsider a 1960s ruling that forbids the banning of contraceptives. Republicans have dismissed concerns about bans being allowed, although Democrats, including the president and vice president, starkly warn that they could happen.

“If we as providers have to be concerned that there will be an unplanned pregnancy because of the lack of access to contraception,” Dr. Kane said, “this will have significant downstream consequences to the kind of care we can provide and might just drive some providers to not give care to female patients at all given this concern.”

The physicians quoted in this article report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Biomarkers may help to predict persistent oligoarticular JIA

Ongoing research in patients with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) so far suggests that a set of biomarkers in synovial fluid may help to predict which patients may be more likely to stay with persistent oligoarticular disease rather than progress to polyarticular disease, according to new research presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, held virtually this year. Identifying biomarkers in synovial fluid or possibly serum could aid families and physicians in being more proactive in treatment protocols, said AnneMarie C. Brescia, MD, of Nemours Children’s Hospital in Wilmington, Del.

“JIA carries the risk of permanent joint damage and disability, which can result when joint involvement evolves from oligoarticular into a polyarticular course, termed extended oligoarticular disease,” Dr. Brescia told attendees. “Since disease progression increases the risk for disability, early prediction of this course is essential.”

This group – those whose oligoarticular disease will begin recruiting joints and ultimately become extended oligoarticular JIA – is “very important because they have been shown to have worse health-related quality of life and greater risk of needing a joint replacement than even polyarticular [JIA],” Dr. Brescia said. “So, our lab has really focused on trying to predict who will fall in this group.”

Melissa Oliver, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of pediatric rheumatology at Indiana University in Indianapolis, was not involved in the study but agreed that having highly sensitive and specific biomarkers could be particularly helpful in clinical care.

“Biomarkers can help guide treatment decisions and help physicians and their patients share the decision-making about next choices and when to change,” Dr. Oliver told this news organization. “If a provider and parent know that their child has these markers in their serum or synovial fluid that may predict extension of their disease, then they may be more aggressive upfront with therapy.”

The study aimed to determine whether differential levels of synovial fluid proteins could be used to predict whether JIA would evolve into an extended course before it became clinically evident. Although early aggressive treatment is common with rheumatoid arthritis and can lead to remission, JIA treatment paradigms tend to be more reactive, Dr. Brescia said.

“It would be better to switch to proactive, that if we’re able to predict that this patient may have a more difficult course with extension to polyarticular, we could be prepared, we could inform the parents, and it would just help us have a more proactive approach,” she said.

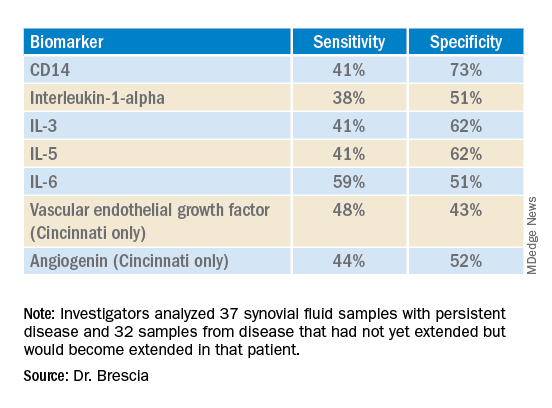

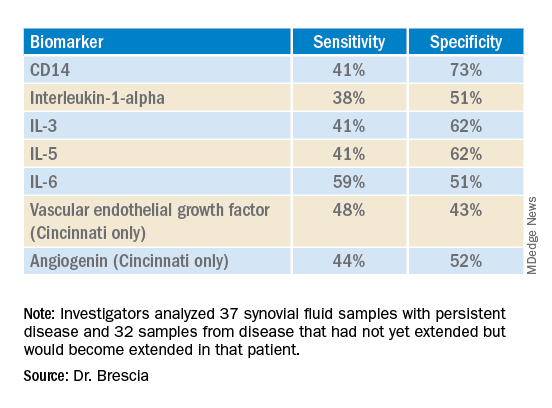

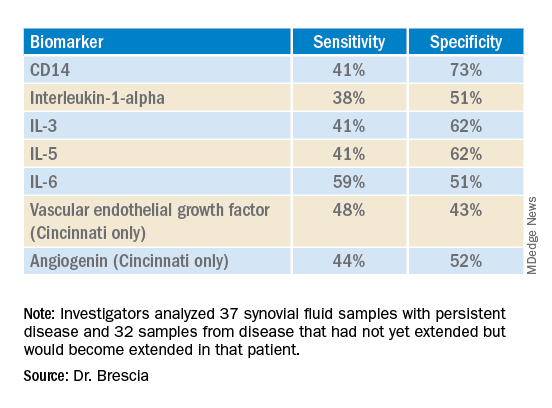

The researchers used antibody arrays to detect the following inflammatory mediators in blinded samples: CD14, interleukin (IL)-1-alpha, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and angiogenin. They analyzed 37 samples with persistent disease and 32 samples from disease that had not yet extended but would become extended in that patient. The samples came from patients who were taking no medicines or only NSAIDs. The researchers assessed the sensitivity and specificity of each biomarker. Sensitivity referred the biomarker’s ability to correctly indicate that the sample would extend, and specificity referred to the biomarker’s accuracy in determining that the disease in the sample would remain persistent.

Combining samples from cohorts at Nemours Children’s Health (14 persistent and 7 extended-to-be) and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (23 persistent and 25 extended-to-be) yielded the following results:

The findings revealed that the selected biomarkers were more accurate at predicting whose disease would remain persistent than predicting those that would extend, Dr. Brescia said. CD14 was the most specific biomarker, and IL-6 was the most sensitive biomarker in both groups.

When the researchers translated the findings from ELISA to the Luminex platform, positive results in synovial fluid for all these biomarkers were also positive in serum samples. Although the differences between persistent and extended-to-be samples did not reach statistical significance using Luminex, the pattern was the same for each biomarker.

“Luminex is more sensitive than ELISA. We believe that conducting an LDA [linear discriminant analysis] using these Luminex measurements will allow us to determine new cutoffs or new protein levels that are appropriate for Luminex to predict who will extend,” Dr. Brescia said. “It’s also our goal to develop a serum panel because ... being able to detect these markers in serum would expand the applicability of these markers to more patients.”

Dr. Brescia then described the group’s work in defining clinically relevant subpopulations of patients based on fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) cells in the synovial intimal lining that produce inflammatory cytokines.

“Our compelling, single-cell, RNA sequencing preliminary data revealing multiple subpopulations within the total FLS population supports our hypothesis that distinct FLS subpopulations correlate with clinical outcome,” said Dr. Brescia. They looked at the percentage of chondrocyte-like, fibroblast-like, and smooth muscle-like subpopulations in samples from patients with oligoarticular JIA, extended-to-be JIA, and polyarticular JIA. Chondrocytes occurred in the largest proportion, and polyarticular JIA FLS had the largest percentage of chondrocytes, compared with the other two subpopulation groups.

“This is a work in progress,” Dr. Brescia said, “so hopefully you’ll hear about it next year.” In response to an attendee’s question, she said she believes identifying reliable biomarkers will eventually lead to refining treatment paradigms.

“I think it will at least change the guidance we can provide parents about making next choices and how quickly to accelerate to those next choices,” Dr. Brescia said. For example, if a child’s serum or synovial fluid has markers that show a very high likelihood of extension, the parent may decide to proceed to the next level medication sooner. “I do think it will push both parents and doctors to be a little more proactive instead of reactive when the poor patient comes back with 13 joints involved when they had just been an oligo for years.”

Dr. Oliver noted the promise of CD14 and IL-6 in potentially predicting which patients’ disease will stay persistent but cautioned that it’s still early in evaluating these biomarkers, especially with the limited patient samples in this study.

“I think these results are promising, and it’s great that there are groups out there working on this,” Dr. Oliver said. “Once we have a reliable, highly sensitive and specific biomarker, that will definitely help providers, parents, and patients be more informed.”

The research was supported by the Open Net Foundation, the Arthritis Foundation, Delaware Community Foundation, the Delaware Clinical and Translational Research (DE-CTR) ACCEL Program, the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases, and CARRA. Dr. Brescia and Dr. Oliver have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ongoing research in patients with oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) so far suggests that a set of biomarkers in synovial fluid may help to predict which patients may be more likely to stay with persistent oligoarticular disease rather than progress to polyarticular disease, according to new research presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance, held virtually this year. Identifying biomarkers in synovial fluid or possibly serum could aid families and physicians in being more proactive in treatment protocols, said AnneMarie C. Brescia, MD, of Nemours Children’s Hospital in Wilmington, Del.

“JIA carries the risk of permanent joint damage and disability, which can result when joint involvement evolves from oligoarticular into a polyarticular course, termed extended oligoarticular disease,” Dr. Brescia told attendees. “Since disease progression increases the risk for disability, early prediction of this course is essential.”

This group – those whose oligoarticular disease will begin recruiting joints and ultimately become extended oligoarticular JIA – is “very important because they have been shown to have worse health-related quality of life and greater risk of needing a joint replacement than even polyarticular [JIA],” Dr. Brescia said. “So, our lab has really focused on trying to predict who will fall in this group.”

Melissa Oliver, MD, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics in the division of pediatric rheumatology at Indiana University in Indianapolis, was not involved in the study but agreed that having highly sensitive and specific biomarkers could be particularly helpful in clinical care.

“Biomarkers can help guide treatment decisions and help physicians and their patients share the decision-making about next choices and when to change,” Dr. Oliver told this news organization. “If a provider and parent know that their child has these markers in their serum or synovial fluid that may predict extension of their disease, then they may be more aggressive upfront with therapy.”

The study aimed to determine whether differential levels of synovial fluid proteins could be used to predict whether JIA would evolve into an extended course before it became clinically evident. Although early aggressive treatment is common with rheumatoid arthritis and can lead to remission, JIA treatment paradigms tend to be more reactive, Dr. Brescia said.

“It would be better to switch to proactive, that if we’re able to predict that this patient may have a more difficult course with extension to polyarticular, we could be prepared, we could inform the parents, and it would just help us have a more proactive approach,” she said.

The researchers used antibody arrays to detect the following inflammatory mediators in blinded samples: CD14, interleukin (IL)-1-alpha, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and angiogenin. They analyzed 37 samples with persistent disease and 32 samples from disease that had not yet extended but would become extended in that patient. The samples came from patients who were taking no medicines or only NSAIDs. The researchers assessed the sensitivity and specificity of each biomarker. Sensitivity referred the biomarker’s ability to correctly indicate that the sample would extend, and specificity referred to the biomarker’s accuracy in determining that the disease in the sample would remain persistent.

Combining samples from cohorts at Nemours Children’s Health (14 persistent and 7 extended-to-be) and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (23 persistent and 25 extended-to-be) yielded the following results:

The findings revealed that the selected biomarkers were more accurate at predicting whose disease would remain persistent than predicting those that would extend, Dr. Brescia said. CD14 was the most specific biomarker, and IL-6 was the most sensitive biomarker in both groups.

When the researchers translated the findings from ELISA to the Luminex platform, positive results in synovial fluid for all these biomarkers were also positive in serum samples. Although the differences between persistent and extended-to-be samples did not reach statistical significance using Luminex, the pattern was the same for each biomarker.

“Luminex is more sensitive than ELISA. We believe that conducting an LDA [linear discriminant analysis] using these Luminex measurements will allow us to determine new cutoffs or new protein levels that are appropriate for Luminex to predict who will extend,” Dr. Brescia said. “It’s also our goal to develop a serum panel because ... being able to detect these markers in serum would expand the applicability of these markers to more patients.”

Dr. Brescia then described the group’s work in defining clinically relevant subpopulations of patients based on fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) cells in the synovial intimal lining that produce inflammatory cytokines.

“Our compelling, single-cell, RNA sequencing preliminary data revealing multiple subpopulations within the total FLS population supports our hypothesis that distinct FLS subpopulations correlate with clinical outcome,” said Dr. Brescia. They looked at the percentage of chondrocyte-like, fibroblast-like, and smooth muscle-like subpopulations in samples from patients with oligoarticular JIA, extended-to-be JIA, and polyarticular JIA. Chondrocytes occurred in the largest proportion, and polyarticular JIA FLS had the largest percentage of chondrocytes, compared with the other two subpopulation groups.

“This is a work in progress,” Dr. Brescia said, “so hopefully you’ll hear about it next year.” In response to an attendee’s question, she said she believes identifying reliable biomarkers will eventually lead to refining treatment paradigms.

“I think it will at least change the guidance we can provide parents about making next choices and how quickly to accelerate to those next choices,” Dr. Brescia said. For example, if a child’s serum or synovial fluid has markers that show a very high likelihood of extension, the parent may decide to proceed to the next level medication sooner. “I do think it will push both parents and doctors to be a little more proactive instead of reactive when the poor patient comes back with 13 joints involved when they had just been an oligo for years.”

Dr. Oliver noted the promise of CD14 and IL-6 in potentially predicting which patients’ disease will stay persistent but cautioned that it’s still early in evaluating these biomarkers, especially with the limited patient samples in this study.

“I think these results are promising, and it’s great that there are groups out there working on this,” Dr. Oliver said. “Once we have a reliable, highly sensitive and specific biomarker, that will definitely help providers, parents, and patients be more informed.”

The research was supported by the Open Net Foundation, the Arthritis Foundation, Delaware Community Foundation, the Delaware Clinical and Translational Research (DE-CTR) ACCEL Program, the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases, and CARRA. Dr. Brescia and Dr. Oliver have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.