User login

Less symptomatic patients ‘worse off’ after knee surgery

AMSTERDAM – Patients with milder knee osteoarthritis symptoms or better quality of life before undergoing total knee replacement surgery gained less benefit from the surgery than did those who had more severe symptoms in two separate analyses of British and U.S. patients.

Additional evidence from total knee replacements (TKRs) performed on U.S. participants of the Osteoarthritis Initiative also suggest that as the use of TKR has increased to include less symptomatic patients, the overall cost-effectiveness of the procedure has declined.

“Knee replacements are one of those interventions that are known to be very effective and very cost-effective,” Rafael Pinedo-Villanueva, Ph.D., of the University of Oxford (England) said during his presentation of National Health Service data from England at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis. Indeed, knee replacements are associated with significant improvements in pain, function, and quality of life, he said, but that is if you look at the mean values.

As the deciles for baseline knee pain and function decrease in severity, there are diminishing mean improvements and an increasing proportion of patients who do worse after the operation, he reported. Up to 17% of patients had unchanged or improved knee pain scores and up to 27% had lower quality of life scores. If minimally important differences were considered, these percentages rose to 40% and 48% of patients being worse off, respectively.

“The significant improvements seem to be overshadowing what happens to those patients who are doing worse,” Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva suggested. “So essentially cost-effectiveness is being driven by the magnitude of the change in those who do improve, and we don’t really see much about what is happening to those who are doing worse.”

Of over 215,000 records of knee replacement collected from all patients undergoing TKR in England during 2008-2012, Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and his study coauthors found 117,844 had data on pre- and post-operative knee pain assessed using the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and quality of life measured with the EQ-5D instrument. The majority of replacements were in women (55%) and almost three quarters of patients had one or no comorbidities. Overall, the mean change in OKS was 15 points, improving from 19 to 34 (the higher the score the lesser the knee pain). EQ-5D scores also improved by a mean difference of 0.30 (from 0.41 to 0.70 where 1.0 is perfect health). Although the vast majority of patients had improved OKS and EQ-5D scores after surgery, unchanged or decreased scores were seen in 8% and 22% of patients, respectively.

“As we breakdown these data by deciles of baseline pain and function we see clearly that those starting at the lower decile improved the most, and that’s to be expected; they’ve a lot more to improve than the ones that came into the operation at the higher decile,” Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva said at the Congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. But there were patients who fared worse at every decile, he noted.

Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva concluded that outcome prediction models were needed to try to reduce the number of patients who are apparently worse off after knee replacement and improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

The value of TKR in a contemporary U.S. population was the focus of a separate presentation by Dr. Bart Ferket of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Dr. Ferket reported the results of a study looking at the impact of TKR on patients’ quality of life, lifetime costs, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) while varying the use of TKR by patients’ functional status at baseline.

“In the United States, the rate at which total knee replacement is performed has doubled in the last two decades,” Dr. Ferket observed. This “disproportionate” increase has been attributed to expanding the eligibility criteria to include less symptomatic patients.

Using data collected over an 8-year period on 1,327 participants from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, Dr. Ferket and his associates at Mount Sinai and Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam (The Netherlands) discovered that the increased uptake of TKR might have affected the likely benefit and reduced the overall cost-effectiveness of the procedure.

At baseline, 17% of the participants, who all had knee osteoarthritis, had had a prior knee replacement.

Quality of life measured on the physical component scores (PCS) of the 12-item Short Form (SF-12) were generally improved after TKR but decreased in those who did not have a knee replaced. The effect on the mental component of the SF-12 was less clear, with possibly a decrease seen in some patients. Changes on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) and Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) showed a considerable benefit for knee replacement and there was a general decrease in pain medication over time in those who had surgery. The overall effect was more pronounced if patients with greater baseline symptoms were considered.

Cost-effectiveness modeling showed that reserving TKR for more seriously affected patients may make it more economically attractive. The QALYs gained from TKR was about 11 but as the number of QALYs increased, so did the relative lifetime cost, with increasing incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) as SF-12 PCS rose. ICERs were around $143,000, $160,000, $217,000, $385,000, and $1,175,000 considering patients with SF-12 PCS of less than 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50, respectively.

“The more lenient the eligibility criteria are, the higher the effectiveness, but also the higher the costs,” Dr. Ferket said. “The most cost-effective scenarios are actually more restrictive that what is currently seen in current practice in the U.S.”

Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and Dr. Ferket reported having no financial disclosures.

AMSTERDAM – Patients with milder knee osteoarthritis symptoms or better quality of life before undergoing total knee replacement surgery gained less benefit from the surgery than did those who had more severe symptoms in two separate analyses of British and U.S. patients.

Additional evidence from total knee replacements (TKRs) performed on U.S. participants of the Osteoarthritis Initiative also suggest that as the use of TKR has increased to include less symptomatic patients, the overall cost-effectiveness of the procedure has declined.

“Knee replacements are one of those interventions that are known to be very effective and very cost-effective,” Rafael Pinedo-Villanueva, Ph.D., of the University of Oxford (England) said during his presentation of National Health Service data from England at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis. Indeed, knee replacements are associated with significant improvements in pain, function, and quality of life, he said, but that is if you look at the mean values.

As the deciles for baseline knee pain and function decrease in severity, there are diminishing mean improvements and an increasing proportion of patients who do worse after the operation, he reported. Up to 17% of patients had unchanged or improved knee pain scores and up to 27% had lower quality of life scores. If minimally important differences were considered, these percentages rose to 40% and 48% of patients being worse off, respectively.

“The significant improvements seem to be overshadowing what happens to those patients who are doing worse,” Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva suggested. “So essentially cost-effectiveness is being driven by the magnitude of the change in those who do improve, and we don’t really see much about what is happening to those who are doing worse.”

Of over 215,000 records of knee replacement collected from all patients undergoing TKR in England during 2008-2012, Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and his study coauthors found 117,844 had data on pre- and post-operative knee pain assessed using the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and quality of life measured with the EQ-5D instrument. The majority of replacements were in women (55%) and almost three quarters of patients had one or no comorbidities. Overall, the mean change in OKS was 15 points, improving from 19 to 34 (the higher the score the lesser the knee pain). EQ-5D scores also improved by a mean difference of 0.30 (from 0.41 to 0.70 where 1.0 is perfect health). Although the vast majority of patients had improved OKS and EQ-5D scores after surgery, unchanged or decreased scores were seen in 8% and 22% of patients, respectively.

“As we breakdown these data by deciles of baseline pain and function we see clearly that those starting at the lower decile improved the most, and that’s to be expected; they’ve a lot more to improve than the ones that came into the operation at the higher decile,” Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva said at the Congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. But there were patients who fared worse at every decile, he noted.

Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva concluded that outcome prediction models were needed to try to reduce the number of patients who are apparently worse off after knee replacement and improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

The value of TKR in a contemporary U.S. population was the focus of a separate presentation by Dr. Bart Ferket of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Dr. Ferket reported the results of a study looking at the impact of TKR on patients’ quality of life, lifetime costs, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) while varying the use of TKR by patients’ functional status at baseline.

“In the United States, the rate at which total knee replacement is performed has doubled in the last two decades,” Dr. Ferket observed. This “disproportionate” increase has been attributed to expanding the eligibility criteria to include less symptomatic patients.

Using data collected over an 8-year period on 1,327 participants from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, Dr. Ferket and his associates at Mount Sinai and Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam (The Netherlands) discovered that the increased uptake of TKR might have affected the likely benefit and reduced the overall cost-effectiveness of the procedure.

At baseline, 17% of the participants, who all had knee osteoarthritis, had had a prior knee replacement.

Quality of life measured on the physical component scores (PCS) of the 12-item Short Form (SF-12) were generally improved after TKR but decreased in those who did not have a knee replaced. The effect on the mental component of the SF-12 was less clear, with possibly a decrease seen in some patients. Changes on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) and Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) showed a considerable benefit for knee replacement and there was a general decrease in pain medication over time in those who had surgery. The overall effect was more pronounced if patients with greater baseline symptoms were considered.

Cost-effectiveness modeling showed that reserving TKR for more seriously affected patients may make it more economically attractive. The QALYs gained from TKR was about 11 but as the number of QALYs increased, so did the relative lifetime cost, with increasing incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) as SF-12 PCS rose. ICERs were around $143,000, $160,000, $217,000, $385,000, and $1,175,000 considering patients with SF-12 PCS of less than 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50, respectively.

“The more lenient the eligibility criteria are, the higher the effectiveness, but also the higher the costs,” Dr. Ferket said. “The most cost-effective scenarios are actually more restrictive that what is currently seen in current practice in the U.S.”

Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and Dr. Ferket reported having no financial disclosures.

AMSTERDAM – Patients with milder knee osteoarthritis symptoms or better quality of life before undergoing total knee replacement surgery gained less benefit from the surgery than did those who had more severe symptoms in two separate analyses of British and U.S. patients.

Additional evidence from total knee replacements (TKRs) performed on U.S. participants of the Osteoarthritis Initiative also suggest that as the use of TKR has increased to include less symptomatic patients, the overall cost-effectiveness of the procedure has declined.

“Knee replacements are one of those interventions that are known to be very effective and very cost-effective,” Rafael Pinedo-Villanueva, Ph.D., of the University of Oxford (England) said during his presentation of National Health Service data from England at the World Congress on Osteoarthritis. Indeed, knee replacements are associated with significant improvements in pain, function, and quality of life, he said, but that is if you look at the mean values.

As the deciles for baseline knee pain and function decrease in severity, there are diminishing mean improvements and an increasing proportion of patients who do worse after the operation, he reported. Up to 17% of patients had unchanged or improved knee pain scores and up to 27% had lower quality of life scores. If minimally important differences were considered, these percentages rose to 40% and 48% of patients being worse off, respectively.

“The significant improvements seem to be overshadowing what happens to those patients who are doing worse,” Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva suggested. “So essentially cost-effectiveness is being driven by the magnitude of the change in those who do improve, and we don’t really see much about what is happening to those who are doing worse.”

Of over 215,000 records of knee replacement collected from all patients undergoing TKR in England during 2008-2012, Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and his study coauthors found 117,844 had data on pre- and post-operative knee pain assessed using the Oxford Knee Score (OKS) and quality of life measured with the EQ-5D instrument. The majority of replacements were in women (55%) and almost three quarters of patients had one or no comorbidities. Overall, the mean change in OKS was 15 points, improving from 19 to 34 (the higher the score the lesser the knee pain). EQ-5D scores also improved by a mean difference of 0.30 (from 0.41 to 0.70 where 1.0 is perfect health). Although the vast majority of patients had improved OKS and EQ-5D scores after surgery, unchanged or decreased scores were seen in 8% and 22% of patients, respectively.

“As we breakdown these data by deciles of baseline pain and function we see clearly that those starting at the lower decile improved the most, and that’s to be expected; they’ve a lot more to improve than the ones that came into the operation at the higher decile,” Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva said at the Congress, sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International. But there were patients who fared worse at every decile, he noted.

Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva concluded that outcome prediction models were needed to try to reduce the number of patients who are apparently worse off after knee replacement and improve the efficiency of resource allocation.

The value of TKR in a contemporary U.S. population was the focus of a separate presentation by Dr. Bart Ferket of Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. Dr. Ferket reported the results of a study looking at the impact of TKR on patients’ quality of life, lifetime costs, and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) while varying the use of TKR by patients’ functional status at baseline.

“In the United States, the rate at which total knee replacement is performed has doubled in the last two decades,” Dr. Ferket observed. This “disproportionate” increase has been attributed to expanding the eligibility criteria to include less symptomatic patients.

Using data collected over an 8-year period on 1,327 participants from the Osteoarthritis Initiative, Dr. Ferket and his associates at Mount Sinai and Erasmus University Medical Center in Rotterdam (The Netherlands) discovered that the increased uptake of TKR might have affected the likely benefit and reduced the overall cost-effectiveness of the procedure.

At baseline, 17% of the participants, who all had knee osteoarthritis, had had a prior knee replacement.

Quality of life measured on the physical component scores (PCS) of the 12-item Short Form (SF-12) were generally improved after TKR but decreased in those who did not have a knee replaced. The effect on the mental component of the SF-12 was less clear, with possibly a decrease seen in some patients. Changes on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) and Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) showed a considerable benefit for knee replacement and there was a general decrease in pain medication over time in those who had surgery. The overall effect was more pronounced if patients with greater baseline symptoms were considered.

Cost-effectiveness modeling showed that reserving TKR for more seriously affected patients may make it more economically attractive. The QALYs gained from TKR was about 11 but as the number of QALYs increased, so did the relative lifetime cost, with increasing incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) as SF-12 PCS rose. ICERs were around $143,000, $160,000, $217,000, $385,000, and $1,175,000 considering patients with SF-12 PCS of less than 30, 35, 40, 45, and 50, respectively.

“The more lenient the eligibility criteria are, the higher the effectiveness, but also the higher the costs,” Dr. Ferket said. “The most cost-effective scenarios are actually more restrictive that what is currently seen in current practice in the U.S.”

Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and Dr. Ferket reported having no financial disclosures.

AT OARSI 2016

Key clinical point: Patients with milder osteoarthritis can fare worse after knee replacement surgery, and the cost-effectiveness of the procedure is lower.

Major finding: Knee pain and quality of life scores were unchanged or worse after the operation in 8% and 22% of patients, respectively.

Data source: Two separate studies looking at the value of knee replacement in patients with knee osteoarthritis.

Disclosures: Dr. Pinedo-Villanueva and Dr. Ferket reported having no financial disclosures.

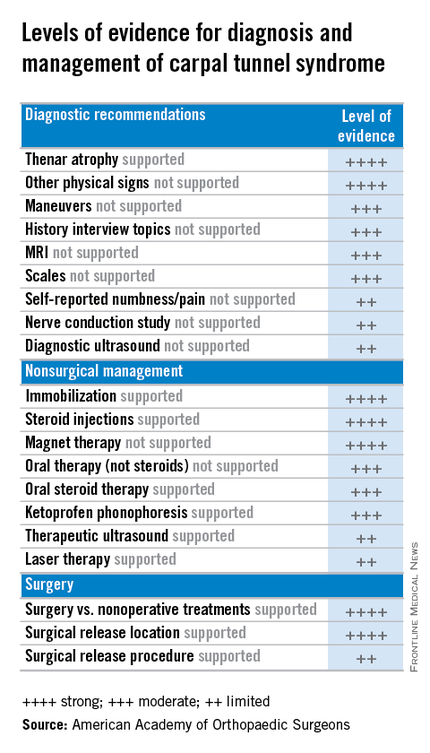

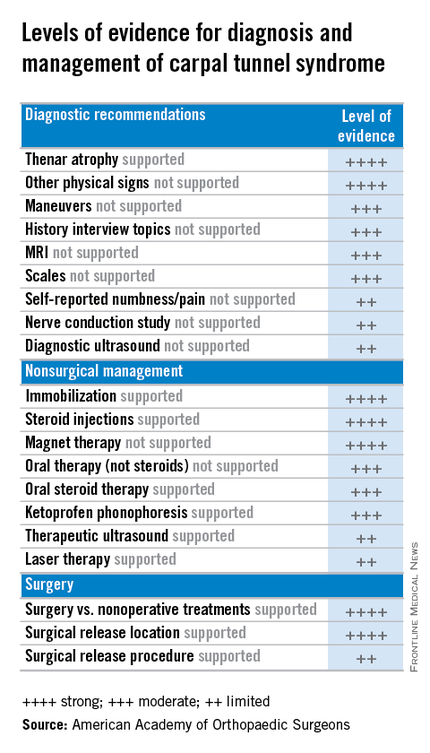

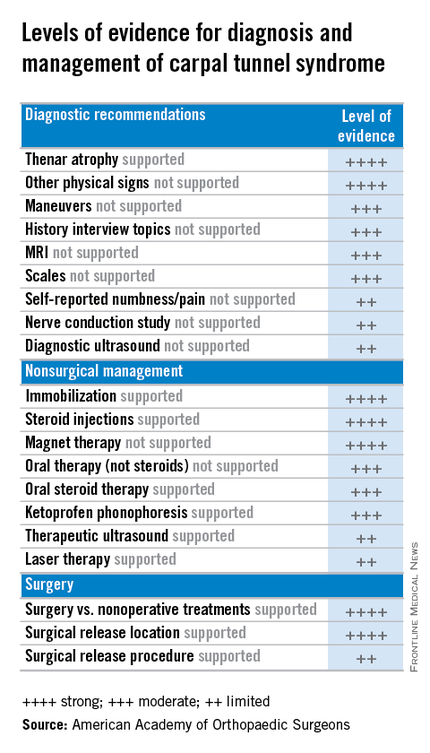

Carpal tunnel syndrome: Guidelines rate evidence for diagnosis, treatment

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has adopted clinical practice guidelines that assign evidence-based ratings for common strategies used to diagnose and treat carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).

The 982-page comprehensive guidelines have been endorsed by the American Society for the Surgery of the Hand and the American College of Radiology. The guidelines address the burden of CTS, the second most common cause of sick days from work, according to AAOS, and its etiology, risk factors, emotional and physical impact, potential benefits, harms, contraindications, and future research. The document is available on the OrthoGuidelines Web-based app at orthoguidelines.org.

The assessments of evidence are based upon a systematic review of the current scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. In addition to a concise summary, the report includes an exhaustive list of studies used to establish levels of evidence and a summary of the evidence in each. Also included is a list of studies not included, many because of poor study design or very small samples.

The guidelines make recommendations on practices to diagnose and manage CTS based on four levels of evidence:

• Strong: Supported by two or more “high-quality” studies with consistent findings.

• Moderate: Supported by two or more “moderate-quality” studies or one “high-quality” study.

• Limited: Supported by two or more “low-quality” studies or one “moderate-quality” study, or the evidence is considered insufficient or conflicting.

• Consensus: No supporting evidence but the guidelines development group made a recommendation based on clinical opinion.

Diagnosis and risk evidence

For diagnosis of CTS, the guidelines rate the evidence for the value of both observation and physical signs as strong, but assign ratings of moderate to MRI and limited to ultrasound. Evidence is strong for thenar atrophy, or diminished thumb muscle mass, being associated with CTS, but a lack of thenar atrophy is not enough to rule out a diagnosis. Common evaluation tools such the Phalen test, Tinel sign, Flick sign, or Upper-Limb Neurodynamic/Nerve Tension test (ULNT) are weakly supported as independent physical examination maneuvers to rule in or rule out carpal tunnel and the guidelines suggest that they not be used as sole diagnostic tools.

Moderate evidence supports exercise and physical activity to reduce the risk of developing CTS. The guidelines consider obesity a strong risk factor for CTS, but assign moderate ratings to evidence for a host of other factors, perimenopausal status, wrist ratio/index, rheumatoid arthritis, psychosocial factors, and activities such as gardening and computer use among them.

Treatment evidence

For treatment, the guidelines evaluate evidence for both surgical and nonsurgical strategies. In general, evidence for the efficacy of splinting, steroids (oral or injection), the use of ketoprofen phonophoresis gel, and magnetic therapy is strong. But therapeutic ultrasound and laser therapy are backed up with only limited evidence from the literature.

As might be expected, the evidence is strong for the efficacy of surgery to release the transverse carpal ligament. “Strong evidence supports that surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome should have a greater treatment benefit at 6 and 12 months as compared to splinting, NSAIDs/therapy, and a single steroid injection.” But the value of adjunctive techniques such as epineurotomy, neurolysis, flexor tenosynovectomy, and lengthening/reconstruction of the flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament) is not supported with strong evidence at this point. And the superiority of the endoscopic surgical approach is supported with only limited evidence.

“The impetus for this came from trying to help physicians cull through literally thousands and thousands of published research papers concerning various diagnoses,” said Dr. Allan E. Peljovich, vice-chair of the Guideline Work Group and AAOS representative to the group. It’s a tool to help orthopedic surgeons and other practitioners “understand what our best evidence tells us about diagnosing and treating a variety of conditions,” he said.

The effort to develop the CTS guidelines started February 2013 and involved the Guideline Work Group formulating a set of questions that, as Dr. Peljovich explained, were “the most pertinent questions that anybody interested in a particular diagnosis would want to have answered.” Then a team of statisticians and epidemiologists culled through the “incredible expanse of English language literature” to correlate data to answer those questions.

In May 2015 the work group then met to review the evidence and draft final recommendations. After a period of editing, the draft was submitted for peer review in September. The AAOS board of directors adopted the guidelines in February.

“The guidelines are not intended to be a cookbook on how to treat a condition,” Dr. Peljovich said. “They are really designed to tell you what the best evidence says about a particular set of questions. It helps you to be as updated as you want to be; it’s not designed to tell you this is the only way to do anything. ... It’s an educational tool.”

Members of the Guideline Work Group, AAOS staff, and contributing members submitted their disclosures to the AAOS.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has adopted clinical practice guidelines that assign evidence-based ratings for common strategies used to diagnose and treat carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).

The 982-page comprehensive guidelines have been endorsed by the American Society for the Surgery of the Hand and the American College of Radiology. The guidelines address the burden of CTS, the second most common cause of sick days from work, according to AAOS, and its etiology, risk factors, emotional and physical impact, potential benefits, harms, contraindications, and future research. The document is available on the OrthoGuidelines Web-based app at orthoguidelines.org.

The assessments of evidence are based upon a systematic review of the current scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. In addition to a concise summary, the report includes an exhaustive list of studies used to establish levels of evidence and a summary of the evidence in each. Also included is a list of studies not included, many because of poor study design or very small samples.

The guidelines make recommendations on practices to diagnose and manage CTS based on four levels of evidence:

• Strong: Supported by two or more “high-quality” studies with consistent findings.

• Moderate: Supported by two or more “moderate-quality” studies or one “high-quality” study.

• Limited: Supported by two or more “low-quality” studies or one “moderate-quality” study, or the evidence is considered insufficient or conflicting.

• Consensus: No supporting evidence but the guidelines development group made a recommendation based on clinical opinion.

Diagnosis and risk evidence

For diagnosis of CTS, the guidelines rate the evidence for the value of both observation and physical signs as strong, but assign ratings of moderate to MRI and limited to ultrasound. Evidence is strong for thenar atrophy, or diminished thumb muscle mass, being associated with CTS, but a lack of thenar atrophy is not enough to rule out a diagnosis. Common evaluation tools such the Phalen test, Tinel sign, Flick sign, or Upper-Limb Neurodynamic/Nerve Tension test (ULNT) are weakly supported as independent physical examination maneuvers to rule in or rule out carpal tunnel and the guidelines suggest that they not be used as sole diagnostic tools.

Moderate evidence supports exercise and physical activity to reduce the risk of developing CTS. The guidelines consider obesity a strong risk factor for CTS, but assign moderate ratings to evidence for a host of other factors, perimenopausal status, wrist ratio/index, rheumatoid arthritis, psychosocial factors, and activities such as gardening and computer use among them.

Treatment evidence

For treatment, the guidelines evaluate evidence for both surgical and nonsurgical strategies. In general, evidence for the efficacy of splinting, steroids (oral or injection), the use of ketoprofen phonophoresis gel, and magnetic therapy is strong. But therapeutic ultrasound and laser therapy are backed up with only limited evidence from the literature.

As might be expected, the evidence is strong for the efficacy of surgery to release the transverse carpal ligament. “Strong evidence supports that surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome should have a greater treatment benefit at 6 and 12 months as compared to splinting, NSAIDs/therapy, and a single steroid injection.” But the value of adjunctive techniques such as epineurotomy, neurolysis, flexor tenosynovectomy, and lengthening/reconstruction of the flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament) is not supported with strong evidence at this point. And the superiority of the endoscopic surgical approach is supported with only limited evidence.

“The impetus for this came from trying to help physicians cull through literally thousands and thousands of published research papers concerning various diagnoses,” said Dr. Allan E. Peljovich, vice-chair of the Guideline Work Group and AAOS representative to the group. It’s a tool to help orthopedic surgeons and other practitioners “understand what our best evidence tells us about diagnosing and treating a variety of conditions,” he said.

The effort to develop the CTS guidelines started February 2013 and involved the Guideline Work Group formulating a set of questions that, as Dr. Peljovich explained, were “the most pertinent questions that anybody interested in a particular diagnosis would want to have answered.” Then a team of statisticians and epidemiologists culled through the “incredible expanse of English language literature” to correlate data to answer those questions.

In May 2015 the work group then met to review the evidence and draft final recommendations. After a period of editing, the draft was submitted for peer review in September. The AAOS board of directors adopted the guidelines in February.

“The guidelines are not intended to be a cookbook on how to treat a condition,” Dr. Peljovich said. “They are really designed to tell you what the best evidence says about a particular set of questions. It helps you to be as updated as you want to be; it’s not designed to tell you this is the only way to do anything. ... It’s an educational tool.”

Members of the Guideline Work Group, AAOS staff, and contributing members submitted their disclosures to the AAOS.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has adopted clinical practice guidelines that assign evidence-based ratings for common strategies used to diagnose and treat carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS).

The 982-page comprehensive guidelines have been endorsed by the American Society for the Surgery of the Hand and the American College of Radiology. The guidelines address the burden of CTS, the second most common cause of sick days from work, according to AAOS, and its etiology, risk factors, emotional and physical impact, potential benefits, harms, contraindications, and future research. The document is available on the OrthoGuidelines Web-based app at orthoguidelines.org.

The assessments of evidence are based upon a systematic review of the current scientific and clinical information and accepted approaches to treatment and/or diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. In addition to a concise summary, the report includes an exhaustive list of studies used to establish levels of evidence and a summary of the evidence in each. Also included is a list of studies not included, many because of poor study design or very small samples.

The guidelines make recommendations on practices to diagnose and manage CTS based on four levels of evidence:

• Strong: Supported by two or more “high-quality” studies with consistent findings.

• Moderate: Supported by two or more “moderate-quality” studies or one “high-quality” study.

• Limited: Supported by two or more “low-quality” studies or one “moderate-quality” study, or the evidence is considered insufficient or conflicting.

• Consensus: No supporting evidence but the guidelines development group made a recommendation based on clinical opinion.

Diagnosis and risk evidence

For diagnosis of CTS, the guidelines rate the evidence for the value of both observation and physical signs as strong, but assign ratings of moderate to MRI and limited to ultrasound. Evidence is strong for thenar atrophy, or diminished thumb muscle mass, being associated with CTS, but a lack of thenar atrophy is not enough to rule out a diagnosis. Common evaluation tools such the Phalen test, Tinel sign, Flick sign, or Upper-Limb Neurodynamic/Nerve Tension test (ULNT) are weakly supported as independent physical examination maneuvers to rule in or rule out carpal tunnel and the guidelines suggest that they not be used as sole diagnostic tools.

Moderate evidence supports exercise and physical activity to reduce the risk of developing CTS. The guidelines consider obesity a strong risk factor for CTS, but assign moderate ratings to evidence for a host of other factors, perimenopausal status, wrist ratio/index, rheumatoid arthritis, psychosocial factors, and activities such as gardening and computer use among them.

Treatment evidence

For treatment, the guidelines evaluate evidence for both surgical and nonsurgical strategies. In general, evidence for the efficacy of splinting, steroids (oral or injection), the use of ketoprofen phonophoresis gel, and magnetic therapy is strong. But therapeutic ultrasound and laser therapy are backed up with only limited evidence from the literature.

As might be expected, the evidence is strong for the efficacy of surgery to release the transverse carpal ligament. “Strong evidence supports that surgical treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome should have a greater treatment benefit at 6 and 12 months as compared to splinting, NSAIDs/therapy, and a single steroid injection.” But the value of adjunctive techniques such as epineurotomy, neurolysis, flexor tenosynovectomy, and lengthening/reconstruction of the flexor retinaculum (transverse carpal ligament) is not supported with strong evidence at this point. And the superiority of the endoscopic surgical approach is supported with only limited evidence.

“The impetus for this came from trying to help physicians cull through literally thousands and thousands of published research papers concerning various diagnoses,” said Dr. Allan E. Peljovich, vice-chair of the Guideline Work Group and AAOS representative to the group. It’s a tool to help orthopedic surgeons and other practitioners “understand what our best evidence tells us about diagnosing and treating a variety of conditions,” he said.

The effort to develop the CTS guidelines started February 2013 and involved the Guideline Work Group formulating a set of questions that, as Dr. Peljovich explained, were “the most pertinent questions that anybody interested in a particular diagnosis would want to have answered.” Then a team of statisticians and epidemiologists culled through the “incredible expanse of English language literature” to correlate data to answer those questions.

In May 2015 the work group then met to review the evidence and draft final recommendations. After a period of editing, the draft was submitted for peer review in September. The AAOS board of directors adopted the guidelines in February.

“The guidelines are not intended to be a cookbook on how to treat a condition,” Dr. Peljovich said. “They are really designed to tell you what the best evidence says about a particular set of questions. It helps you to be as updated as you want to be; it’s not designed to tell you this is the only way to do anything. ... It’s an educational tool.”

Members of the Guideline Work Group, AAOS staff, and contributing members submitted their disclosures to the AAOS.

Can the Mediterranean Diet Reduce the Risk of Hip Fracture?

Eating a Mediterranean diet full of fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, legumes, and whole grains is associated with a slightly lower risk of hip fracture in women, according to a study published online ahead of print in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data on diet and fracture risk in more than 90,000 postmenopausal women (average age, 63.6 years) who were followed for an average of almost 16 years. Diet quality and adherence were assessed by scores on 4 scales: the alternate Mediterranean Diet (aMED); the Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI-2010); the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010); and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

Women who scored the highest for adherence to a Mediterranean diet were at lower risk for hip fractures, although the absolute risk reduction was 0.29%. There was no association between a Mediterranean diet and total fracture risk.

A higher HEI-2010 or DASH score was inversely related to the risk of hip fracture, but the finding was not statistically significant. There was no association between HEI-2010, DASH and total fracture risk. The highest scores for AHEI-2010 were not significantly associated with hip or total fracture risk.

Suggested Reading

Haring B, Crandall CJ, Wu C, et al. Dietary patterns and fractures in postmenopausal women: results from the women's health initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Mar 28. [Epub ahead of print]

Eating a Mediterranean diet full of fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, legumes, and whole grains is associated with a slightly lower risk of hip fracture in women, according to a study published online ahead of print in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data on diet and fracture risk in more than 90,000 postmenopausal women (average age, 63.6 years) who were followed for an average of almost 16 years. Diet quality and adherence were assessed by scores on 4 scales: the alternate Mediterranean Diet (aMED); the Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI-2010); the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010); and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

Women who scored the highest for adherence to a Mediterranean diet were at lower risk for hip fractures, although the absolute risk reduction was 0.29%. There was no association between a Mediterranean diet and total fracture risk.

A higher HEI-2010 or DASH score was inversely related to the risk of hip fracture, but the finding was not statistically significant. There was no association between HEI-2010, DASH and total fracture risk. The highest scores for AHEI-2010 were not significantly associated with hip or total fracture risk.

Eating a Mediterranean diet full of fruits, vegetables, fish, nuts, legumes, and whole grains is associated with a slightly lower risk of hip fracture in women, according to a study published online ahead of print in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Researchers analyzed data on diet and fracture risk in more than 90,000 postmenopausal women (average age, 63.6 years) who were followed for an average of almost 16 years. Diet quality and adherence were assessed by scores on 4 scales: the alternate Mediterranean Diet (aMED); the Healthy Eating Index 2010 (HEI-2010); the Alternate Healthy Eating Index 2010 (AHEI-2010); and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet.

Women who scored the highest for adherence to a Mediterranean diet were at lower risk for hip fractures, although the absolute risk reduction was 0.29%. There was no association between a Mediterranean diet and total fracture risk.

A higher HEI-2010 or DASH score was inversely related to the risk of hip fracture, but the finding was not statistically significant. There was no association between HEI-2010, DASH and total fracture risk. The highest scores for AHEI-2010 were not significantly associated with hip or total fracture risk.

Suggested Reading

Haring B, Crandall CJ, Wu C, et al. Dietary patterns and fractures in postmenopausal women: results from the women's health initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Mar 28. [Epub ahead of print]

Suggested Reading

Haring B, Crandall CJ, Wu C, et al. Dietary patterns and fractures in postmenopausal women: results from the women's health initiative. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Mar 28. [Epub ahead of print]

Rate of Tommy John Surgeries in Young Athletes Is on the Rise

An increasing number of adolescents are undergoing ulnar lateral ligament (UCL) surgery to repair a pitching-related elbow injury, according to a study published online ahead of print in the March issue of the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Analyzing a database of all ambulatory discharges in New York state, researchers found that 444 patients underwent surgery to repair their UCL between 2002 and 2011. The median age of study participants was 21; most were male.

The total volume of UCL surgeries increased nearly 200% during that time, while the number of UCL reconstructions per 100,000 people tripled from 0.15 to 0.45. Almost all of the growth occurred in two age groups, 17- to 18-year-olds and 19- to 20-year-olds. Patients who had private insurance were 25 times more likely to undergo UCL construction than those with Medicaid.

Suggested Reading

Hodgins JL, Vitale M, Arons RR, et al. Epidemiology of Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Mar;44(3):729-34. [Epub ahead of print].

An increasing number of adolescents are undergoing ulnar lateral ligament (UCL) surgery to repair a pitching-related elbow injury, according to a study published online ahead of print in the March issue of the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Analyzing a database of all ambulatory discharges in New York state, researchers found that 444 patients underwent surgery to repair their UCL between 2002 and 2011. The median age of study participants was 21; most were male.

The total volume of UCL surgeries increased nearly 200% during that time, while the number of UCL reconstructions per 100,000 people tripled from 0.15 to 0.45. Almost all of the growth occurred in two age groups, 17- to 18-year-olds and 19- to 20-year-olds. Patients who had private insurance were 25 times more likely to undergo UCL construction than those with Medicaid.

An increasing number of adolescents are undergoing ulnar lateral ligament (UCL) surgery to repair a pitching-related elbow injury, according to a study published online ahead of print in the March issue of the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Analyzing a database of all ambulatory discharges in New York state, researchers found that 444 patients underwent surgery to repair their UCL between 2002 and 2011. The median age of study participants was 21; most were male.

The total volume of UCL surgeries increased nearly 200% during that time, while the number of UCL reconstructions per 100,000 people tripled from 0.15 to 0.45. Almost all of the growth occurred in two age groups, 17- to 18-year-olds and 19- to 20-year-olds. Patients who had private insurance were 25 times more likely to undergo UCL construction than those with Medicaid.

Suggested Reading

Hodgins JL, Vitale M, Arons RR, et al. Epidemiology of Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Mar;44(3):729-34. [Epub ahead of print].

Suggested Reading

Hodgins JL, Vitale M, Arons RR, et al. Epidemiology of Medial Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016 Mar;44(3):729-34. [Epub ahead of print].

New Pain Management Technique Can Preserve Muscle Strength in ACL Patients

Anesthesiologists can significantly reduce loss of muscle strength in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) knee surgery patients by using a new technique called an adductor canal block instead of a conventional femoral nerve block, according to a study published online ahead of print March 3 in Anesthesiology. Unlike the previously used femoral nerve block, the adductor canal block targets the distal branches of the femoral nerve in the mid-thigh.

Researchers randomly assigned 100 patients undergoing surgery for ACL repair to femoral nerve block or adductor canal block. They used a dynamometer to assessed patients’ muscle strength in patients for 45 minutes after receiving a nerve block. They then followed patients for 24 hours postop to gauge their pain severity and pain medication needs, and also recorded the incidence of falls or readmissions.

Patients who received the new mid-thigh adductor block experienced a 22% loss of muscle strength in the quadriceps, compare to a 71% loss for those who received the femoral nerve block. Those who received the new block reported no falls or accidents requiring readmission, compared with three falls or near-falls in the other group.

Suggested Reading

Abdallah FW, Whelan DB, Chan VW, et al. Adductor canal block provides noninferior analgesia and superior quadriceps strength compared with femoral nerve block in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Anesthesiology. 2016 Mar 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Anesthesiologists can significantly reduce loss of muscle strength in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) knee surgery patients by using a new technique called an adductor canal block instead of a conventional femoral nerve block, according to a study published online ahead of print March 3 in Anesthesiology. Unlike the previously used femoral nerve block, the adductor canal block targets the distal branches of the femoral nerve in the mid-thigh.

Researchers randomly assigned 100 patients undergoing surgery for ACL repair to femoral nerve block or adductor canal block. They used a dynamometer to assessed patients’ muscle strength in patients for 45 minutes after receiving a nerve block. They then followed patients for 24 hours postop to gauge their pain severity and pain medication needs, and also recorded the incidence of falls or readmissions.

Patients who received the new mid-thigh adductor block experienced a 22% loss of muscle strength in the quadriceps, compare to a 71% loss for those who received the femoral nerve block. Those who received the new block reported no falls or accidents requiring readmission, compared with three falls or near-falls in the other group.

Anesthesiologists can significantly reduce loss of muscle strength in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) knee surgery patients by using a new technique called an adductor canal block instead of a conventional femoral nerve block, according to a study published online ahead of print March 3 in Anesthesiology. Unlike the previously used femoral nerve block, the adductor canal block targets the distal branches of the femoral nerve in the mid-thigh.

Researchers randomly assigned 100 patients undergoing surgery for ACL repair to femoral nerve block or adductor canal block. They used a dynamometer to assessed patients’ muscle strength in patients for 45 minutes after receiving a nerve block. They then followed patients for 24 hours postop to gauge their pain severity and pain medication needs, and also recorded the incidence of falls or readmissions.

Patients who received the new mid-thigh adductor block experienced a 22% loss of muscle strength in the quadriceps, compare to a 71% loss for those who received the femoral nerve block. Those who received the new block reported no falls or accidents requiring readmission, compared with three falls or near-falls in the other group.

Suggested Reading

Abdallah FW, Whelan DB, Chan VW, et al. Adductor canal block provides noninferior analgesia and superior quadriceps strength compared with femoral nerve block in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Anesthesiology. 2016 Mar 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Suggested Reading

Abdallah FW, Whelan DB, Chan VW, et al. Adductor canal block provides noninferior analgesia and superior quadriceps strength compared with femoral nerve block in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Anesthesiology. 2016 Mar 3. [Epub ahead of print]

ADHD Medications Are Linked to Diminished Bone Density in Young Patients

Children and adolescents who take medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) show decreased bone density, according to a large cross-sectional study presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in Orlando.

Researchers identified 5,315 pediatric patients in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and compared children who were taking an ADHD medication (methylphenidate, desmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, atomoxetine, or lisdexamfetamine) with those who were not.

Children taking ADHD medication had lower bone mineral density in the femur, femoral neck, and lumbar spine. Approximately 25% of survey participants who were taking ADHD medication met criteria for osteopenia.

Researchers were able to rule out other potential causes of low bone density in these children, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and poverty levels. However, the study did not include information on dose, duration of use, or changes in therapy because of the limitations of the NHANES survey data.

Children and adolescents who take medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) show decreased bone density, according to a large cross-sectional study presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in Orlando.

Researchers identified 5,315 pediatric patients in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and compared children who were taking an ADHD medication (methylphenidate, desmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, atomoxetine, or lisdexamfetamine) with those who were not.

Children taking ADHD medication had lower bone mineral density in the femur, femoral neck, and lumbar spine. Approximately 25% of survey participants who were taking ADHD medication met criteria for osteopenia.

Researchers were able to rule out other potential causes of low bone density in these children, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and poverty levels. However, the study did not include information on dose, duration of use, or changes in therapy because of the limitations of the NHANES survey data.

Children and adolescents who take medication for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) show decreased bone density, according to a large cross-sectional study presented at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in Orlando.

Researchers identified 5,315 pediatric patients in the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and compared children who were taking an ADHD medication (methylphenidate, desmethylphenidate, dextroamphetamine, atomoxetine, or lisdexamfetamine) with those who were not.

Children taking ADHD medication had lower bone mineral density in the femur, femoral neck, and lumbar spine. Approximately 25% of survey participants who were taking ADHD medication met criteria for osteopenia.

Researchers were able to rule out other potential causes of low bone density in these children, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, and poverty levels. However, the study did not include information on dose, duration of use, or changes in therapy because of the limitations of the NHANES survey data.

A Click Is Not a Clunk: Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in a Newborn

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Newborn hip evaluation algorithm

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, follows a spectrum of irregular anatomic hip development spanning from acetabular dysplasia to irreducible dislocation at birth. Early detection is critical to improve the overall prognosis. Prompt diagnosis requires understanding of potential risk factors, proficiency in physical examination techniques, and implementation of appropriate screening tools when indicated. Although current guidelines direct timing for physical exam screenings, imaging, and treatment, it is ultimately up to the provider to determine the best course of action on a case-by-case basis. This article provides a review of these topics and more.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed guidelines for detection of hip dysplasia, including recommendation of relevant physical exam screenings for all newborns.1 In 2007, the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) encouraged providers to follow the AAP guidelines with a continued recommendation to perform newborn screening for hip instability and routine follow-up evaluations until the child achieves walking.2 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) also established clinical guidelines in 2014 that are endorsed by both AAP and POSNA.3 These guidelines support routine clinical screening; research evaluated infants up to 6 months old, however, limiting the recommendations to that age-group.

Failure to treat DDH early has been associated with serious negative sequelae that include chronic pain, degenerative arthritis, postural scoliosis, and early gait disturbances.4 Primary care providers are expected to perform thorough newborn hip exams with associated specialized tests (ie, Ortolani and Barlow, which are discussed in “Physical exam”) at each routine follow-up. Heightened clinical suspicion and risk factor awareness are key for primary care providers to promptly identify patients requiring orthopedic referral. With early diagnosis, a removable soft abduction brace can be applied as the initial treatment. When treatment is delayed, however, closed reduction under anesthesia or complex surgical intervention may be required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The etiology for DDH remains unknown. Hip dysplasia typically presents unilaterally but can also occur bilaterally. DDH is more likely to affect the left hip than the right.5

Reported incidence varies, ranging from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1,000 live births, and is largely affected by race and geographic location.5 Incidence is higher in countries where routine screening is required, by either physical examination or ultrasound (1.6 to 28.5 and 34.0 to 60.3 per 1,000, respectively), compared with countries not requiring routine screening (1.3 per 1,000). This may suggest that the majority of hip dysplasia cases are transient and resolve spontaneously without treatment.6,7

RISK FACTORS AND PATIENT HISTORY

Known risk factors for DDH include breech presentation (see Figure 1), positive family history, and female gender.5,8-10 Female infants are eight times more likely than males to develop DDH.10 Firstborn status is also recognized as an associated risk factor, which may be attributable to space constraints in utero. This hypothesis is further supported by the relative DDH-protective effect of prematurity and low birth weight. Other potential risk factors include advanced maternal age, birth weight that is high for gestational age, decreased hip abduction, and joint laxity. However, the majority of patients with hip dysplasia have no identifiable risk factors.3,5,9,11,12

Swaddling, which often maintains the hips in an adducted and/or extended position, has also been strongly associated with hip dysplasia.5,13 Multiple organizations, including the AAOS,AAP, POSNA, and the International Hip Dysplasia Institute, have developed or endorsed hip-healthy swaddling recommendations to minimize the risk for DDH in swaddled infants.13-15 Such practices allow the infant’s legs to bend up and out at the hips, promoting free hip movement, flexion, and abduction.13,15 Swaddling has demonstrated multiple benefits (including improved sleep and relief of excessive crying13) and continues to be recommended by many US providers; however, those caring for infants at risk for DDH should avoid traditional swaddling and/or practice hip-healthy swaddling techniques.10,13,14 Early diagnosis starts with the clinician’s knowledge of DDH risk factors and the recommended screening protocols. The presence of multiple risk factors will increase the likelihood of this condition and should lower the clinician’s threshold for ordering additional screening, regardless of hip exam findings.

PHYSICAL EXAM

Both AAP and AAOS guidelines recommend clinical screening for DDH with physical exam in all newborns.1,3 A head-to-toe musculoskeletal exam is warranted during the initial evaluation of every newborn in order to assess for any known DDH-associated conditions, which may include neuromuscular disorders, torticollis, and metatarsus adductus.5

Initial evaluation of an infant with DDH may reveal nonspecific findings, including asymmetric skin folds and limb-length inequality. The Galeazzi sign should be sought by aligning flexed knees with the child in the supine position and assessing for uneven knee heights (see Figure 2). Unilateral posterior hip dislocation or femoral shortening represents a positive Galeazzi sign.16 Joint laxity and limited hip abduction have also been associated with DDH.1,10

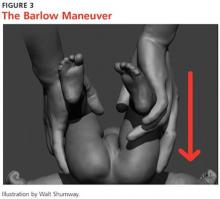

Barlow and Ortolani exams are more specific to DDH and should be completed at newborn screening and each subsequent well-baby exam.1 The Barlow maneuver is a provocative test with flexion, adduction, and posterior pressure through the infant’s hip (Figure 3). A palpable clunk during the Barlow maneuver indicates positive instability with posterior displacement. The Ortolani test is a reductive maneuver requiring abduction with posterior pressure to lift the greater trochanter (Figure 4). A clunk sensation with this test is positive for reduction of the hip.

The infant’s diaper should be removed during the hip evaluation. These exams are more reliable when each hip is evaluated separately with the pelvis stabilized.10 All physical exam findings must be carefully documented at each encounter.1,17

It is critical for the examiner to understand the appropriate technique and potential results when conducting each of these specialized hip exams. A true positive finding is the clunking sensation that occurs with the dislocation or relocation of the affected hip; this finding is better felt than heard. In contrast, a benign hip click with these maneuvers is a more subtle sensation—typically, a soft-tissue snapping or catching—and is not diagnostic of DDH. A click is not a clunk and is not indicative of DDH.1,3

DDH may present later in infancy or early childhood; therefore, DDH should remain within the differential diagnosis for gait asymmetry, unequal hip motion, or limb-length discrepancy. It may be beneficial to continue to evaluate for these developments during routine exams as part of a thorough pediatric musculoskeletal assessment, particularly in patients with documented risk factors for DDH.1,3,4 Delay in diagnosis of DDH, it should be noted, is a relatively common complaint in pediatric medical malpractice lawsuits; until the early 2000s, this condition represented about 75% of claims in one medical malpractice database.The decrease in claims has been attributed to better awareness and earlier diagnosis of DDH. 17

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

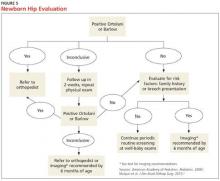

A positive Ortolani or Barlow sign is diagnostic and warrants prompt orthopedic referral (Figure 5). If physical examination results are equivocal or inconclusive, follow-up at two weeks is recommended, with continued routine follow-up until walking is achieved. Patients with persistent equivocal findings at the two-week follow-up warrant ultrasound at age 3 to 4 weeks or orthopedic referral. Infants with significant risk factors, particularly breech presentation at birth, should also undergo imaging.18 AAP recommends ultrasound at age 6 weeks or radiograph after 4 months of age.1,18 AAOS recommends performing an imaging study before age 6 months when at least one of the following risk factors is present: breech presentation, positive family history of DDH, or previous clinical instability (moderate level of evidence).3

IMAGING

Ultrasound is the diagnostic test of choice for infants because radiographs have limited value until the femoral heads begin to ossify at age 4 to 6 months.18 Ultrasonography allows for visualization of the cartilaginous portion of the acetabulum and femoral head.1 Dynamic stressing is performed during ultrasound to assess the level of hip stability. A provider trained in ultrasound will measure the depth of the acetabulum and identify any potential laxity or instability of the hip joint. Accuracy of these findings is largely dependent on the experience and skill of the examiner.

Ultrasound evaluation is not recommended until after age 3 to 4 weeks. Earlier findings may include mild laxity and immature morphology of the acetabulum, which often resolve spontaneously.1,18 Use of ultrasound is currently recommended only to confirm diagnostic suspicion, based on clinical findings, or for infants with significant risk factors.18 Universal ultrasound screening in newborns is not recommended and would incur unnecessary costs.1,3,9 Plain radiographs are used after age 4 months to confirm a diagnosis of DDH or to assess for residual dysplasia.3,18

Continue for management >>

MANAGEMENT

Once hip dysplasia is suggested by physical exam or imaging study, the child’s subsequent care should be provided by an orthopedic specialist with experience in treating this condition. Treatment is preferably initiated before age 6 weeks.12 The specifics of treatment are largely based on age at diagnosis and the severity of dysplasia.

The goal of treatment is to maintain the hips in a stable position with the femoral head well covered by the acetabulum. This will improve anatomic development and function. Early clinical diagnosis is often sufficient to justify initiating conservative treatment; additionally, early detection of DDH can considerably reduce the need for surgical intervention.12 Although the potential for spontaneous resolution is high, the consequences associated with delay in care can be significant.

Preferred initial management, which can be initiated before confirmation of DDH by ultrasound, involves implementation of soft abduction support.19 The Pavlik harness is the support design of choice (Figure 6).12 This harness maintains hip flexion and abduction, creating concentric reduction of the femoral head. The brace is highly successful when its use is initiated early. Treatment in a Pavlik harness requires nearly full-time wear and close monitoring by a clinician. Unlikely potential risks associated with this treatment include avascular necrosis and femoral nerve palsy.4

Ultrasonography is used to further monitor treatment and to determine length of wear. Long-term results suggest a success rate exceeding 90%.20,21 However, this rate may be falsely elevated due to the number of hips that likely would have improved spontaneously without treatment.6,19

The Pavlik harness becomes less effective with increasing age, and a more rigid abduction brace may be considered in infants older than 6 months.20 Overall outcomes improve once the femoral head is consistently maintained in the acetabulum. Delay in treatment is associated with an increase in the long-term complications associated with residual hip dysplasia.22

Once an infant is undergoing treatment for DDH in a Pavlik harness, there is no need for primary care providers to continue to perform provocative testing, such as the Ortolani or Barlow test, at routine well-baby checks. Unnecessary stress to the hips is not beneficial, and any new results will not change the treatment being provided by the orthopedic specialist. Adjustments to the fit of the harness should be made only by the orthopedist, unless femoral nerve palsy is noted on exam. This development warrants immediate discontinuation of harness use until symptoms resolve.21

Abduction bracing may not be suitable for all cases of hip dysplasia. Newborns with irreducible hips, more advanced dysplasia, or associated neuromuscular or syndromic disorder may require closed versus open reduction and casting. More invasive surgical options may also be considered in advanced dysplasia in order to reshape the joint and improve function.20,22

Continue for patient education >>

PATIENT EDUCATION

Parents should be fully educated on the options for managing hip dysplasia. Once DDH is diagnosed, prompt referral to an orthopedic specialist is critical in order to weigh the treatment options and to develop the appropriate individualized plan for each child. Once treatment is initiated, parental compliance is essential; frequent meetings between parents and the specialist are important.

Parents of infants with known risk factors for and/or suspicion of hip dysplasia should also be educated on hip-healthy swaddling to allow for free motion of the hips and knees.10,13 Advise them that some commercial baby carriers and slings may maintain the hips in an undesirable extended position. In both swaddling and with baby carriers, care should be taken to allow for hip abduction and flexion. Caution should also be taken during diaper changes to avoid lifting the legs and thereby causing unnecessary stress to the hips.

CONCLUSION

Developmental dysplasia of the hip can be a disabling pediatric condition. Early diagnosis improves the likelihood of successful treatment during infancy and can prevent serious complications. If untreated, DDH can lead to joint degeneration and premature arthritis. Recognition and treatment within the first six weeks of life is crucial to the overall outcome.

The role of a primary care provider is to identify hip dysplasia risk factors and recognize associated physical exam findings in order to refer to an orthopedic specialist in a timely manner. Guidelines from the AAP, POSNA, and AAOS help direct this process in order to effectively identify infants at risk and in need of treatment.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Clinical practice guideline: early detection of developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics. 2000;105(4 pt 1):896-905.

2. Schwend RM, Schoenecker P, Richards BS, et al. Screening the newborn for developmental dysplasia of the hip: now what do we do? J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(6):607-610.

3. Mulpuri K, Song KM, Goldberg MJ, Sevarino K. Detection and nonoperative management of pediatric developmental dysplasia of the hip in infants up to six months of age. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23(3):202-205.

4. Thomas SRYW. A review of long-term outcomes for late presenting developmental hip dysplasia. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(6):729-733.

5. Loder RT, Skopelja EN. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthop. 2011;2011:238607.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):898-902.

7. Shorter D, Hong T, Osborn DA. Screening programmes for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9):CD004595.

8. Loder RT, Shafer C. The demographics of developmental hip dysplasia in the Midwestern United States (Indiana). J Child Orthop. 2015;9(1):93-98.

9. Paton RW, Hinduja K, Thomas CD. The significance of at-risk factors in ultrasound surveillance of developmental dysplasia of the hip: a ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1264-1266.

10. Alsaleem M, Set KK, Saadeh L. Developmental dysplasia of hip: a review. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54(10):921-928.

11. Chan A, McCaul KA, Cundy PJ, et al. Perinatal risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76(2):F94-F100.

12. Godley DR. Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip. JAAPA. 2013;26(3):54-58.

13. Van Sleuwen BE, Engelberts AC, Boere-Boonekamp MM, et al. Swaddling: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1097-e1106.

14. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Position statement: swaddling and developmental hip dysplasia. www.aaos.org/uploadedFiles/PreProduction/About/Opinion_Statements/position/1186%20Swaddling%20and%20Developmental%20Hip%20Dysplasia.pdf. Accessed January 22, 2016.

15. Clarke NM. Swaddling and hip dysplasia: an orthopaedic perspective. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(1):5-6.

16. Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1310-1316.

17. McAbee GN, Donn SM, Mendelson RA, et al. Medical diagnoses commonly associated with pediatric malpractice lawsuits in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1282-e1286.

18. Imrie M, Scott V, Stearns P, et al. Is ultrasound screening for DDH in babies born breech sufficient? J Child Orthop. 2010;4(1):3-8.

19. Chen HW, Chang CH, Tsai ST, et al. Natural progression of hip dysplasia in newborns: a reflection of hip ultrasonographic screenings in newborn nurseries. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2010;19(5):418-423.

20. Gans I, Flynn JM, Sankar WN. Abduction bracing for residual acetabular dysplasia in infantile DDH. J Pediatr Orthop. 2013;33(7):714-718.

21. Murnaghan ML, Browne RH, Sucato DJ, Birch J. Femoral nerve palsy in Pavlik harness treatment for developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(5):493-499.

22. Dezateux C, Rosendahl K. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1541-1552.

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Newborn hip evaluation algorithm

Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), previously known as congenital dislocation of the hip, follows a spectrum of irregular anatomic hip development spanning from acetabular dysplasia to irreducible dislocation at birth. Early detection is critical to improve the overall prognosis. Prompt diagnosis requires understanding of potential risk factors, proficiency in physical examination techniques, and implementation of appropriate screening tools when indicated. Although current guidelines direct timing for physical exam screenings, imaging, and treatment, it is ultimately up to the provider to determine the best course of action on a case-by-case basis. This article provides a review of these topics and more.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) developed guidelines for detection of hip dysplasia, including recommendation of relevant physical exam screenings for all newborns.1 In 2007, the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America (POSNA) encouraged providers to follow the AAP guidelines with a continued recommendation to perform newborn screening for hip instability and routine follow-up evaluations until the child achieves walking.2 The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) also established clinical guidelines in 2014 that are endorsed by both AAP and POSNA.3 These guidelines support routine clinical screening; research evaluated infants up to 6 months old, however, limiting the recommendations to that age-group.

Failure to treat DDH early has been associated with serious negative sequelae that include chronic pain, degenerative arthritis, postural scoliosis, and early gait disturbances.4 Primary care providers are expected to perform thorough newborn hip exams with associated specialized tests (ie, Ortolani and Barlow, which are discussed in “Physical exam”) at each routine follow-up. Heightened clinical suspicion and risk factor awareness are key for primary care providers to promptly identify patients requiring orthopedic referral. With early diagnosis, a removable soft abduction brace can be applied as the initial treatment. When treatment is delayed, however, closed reduction under anesthesia or complex surgical intervention may be required.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The etiology for DDH remains unknown. Hip dysplasia typically presents unilaterally but can also occur bilaterally. DDH is more likely to affect the left hip than the right.5

Reported incidence varies, ranging from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1,000 live births, and is largely affected by race and geographic location.5 Incidence is higher in countries where routine screening is required, by either physical examination or ultrasound (1.6 to 28.5 and 34.0 to 60.3 per 1,000, respectively), compared with countries not requiring routine screening (1.3 per 1,000). This may suggest that the majority of hip dysplasia cases are transient and resolve spontaneously without treatment.6,7

RISK FACTORS AND PATIENT HISTORY

Known risk factors for DDH include breech presentation (see Figure 1), positive family history, and female gender.5,8-10 Female infants are eight times more likely than males to develop DDH.10 Firstborn status is also recognized as an associated risk factor, which may be attributable to space constraints in utero. This hypothesis is further supported by the relative DDH-protective effect of prematurity and low birth weight. Other potential risk factors include advanced maternal age, birth weight that is high for gestational age, decreased hip abduction, and joint laxity. However, the majority of patients with hip dysplasia have no identifiable risk factors.3,5,9,11,12

Swaddling, which often maintains the hips in an adducted and/or extended position, has also been strongly associated with hip dysplasia.5,13 Multiple organizations, including the AAOS,AAP, POSNA, and the International Hip Dysplasia Institute, have developed or endorsed hip-healthy swaddling recommendations to minimize the risk for DDH in swaddled infants.13-15 Such practices allow the infant’s legs to bend up and out at the hips, promoting free hip movement, flexion, and abduction.13,15 Swaddling has demonstrated multiple benefits (including improved sleep and relief of excessive crying13) and continues to be recommended by many US providers; however, those caring for infants at risk for DDH should avoid traditional swaddling and/or practice hip-healthy swaddling techniques.10,13,14 Early diagnosis starts with the clinician’s knowledge of DDH risk factors and the recommended screening protocols. The presence of multiple risk factors will increase the likelihood of this condition and should lower the clinician’s threshold for ordering additional screening, regardless of hip exam findings.

PHYSICAL EXAM

Both AAP and AAOS guidelines recommend clinical screening for DDH with physical exam in all newborns.1,3 A head-to-toe musculoskeletal exam is warranted during the initial evaluation of every newborn in order to assess for any known DDH-associated conditions, which may include neuromuscular disorders, torticollis, and metatarsus adductus.5

Initial evaluation of an infant with DDH may reveal nonspecific findings, including asymmetric skin folds and limb-length inequality. The Galeazzi sign should be sought by aligning flexed knees with the child in the supine position and assessing for uneven knee heights (see Figure 2). Unilateral posterior hip dislocation or femoral shortening represents a positive Galeazzi sign.16 Joint laxity and limited hip abduction have also been associated with DDH.1,10

Barlow and Ortolani exams are more specific to DDH and should be completed at newborn screening and each subsequent well-baby exam.1 The Barlow maneuver is a provocative test with flexion, adduction, and posterior pressure through the infant’s hip (Figure 3). A palpable clunk during the Barlow maneuver indicates positive instability with posterior displacement. The Ortolani test is a reductive maneuver requiring abduction with posterior pressure to lift the greater trochanter (Figure 4). A clunk sensation with this test is positive for reduction of the hip.

The infant’s diaper should be removed during the hip evaluation. These exams are more reliable when each hip is evaluated separately with the pelvis stabilized.10 All physical exam findings must be carefully documented at each encounter.1,17

It is critical for the examiner to understand the appropriate technique and potential results when conducting each of these specialized hip exams. A true positive finding is the clunking sensation that occurs with the dislocation or relocation of the affected hip; this finding is better felt than heard. In contrast, a benign hip click with these maneuvers is a more subtle sensation—typically, a soft-tissue snapping or catching—and is not diagnostic of DDH. A click is not a clunk and is not indicative of DDH.1,3

DDH may present later in infancy or early childhood; therefore, DDH should remain within the differential diagnosis for gait asymmetry, unequal hip motion, or limb-length discrepancy. It may be beneficial to continue to evaluate for these developments during routine exams as part of a thorough pediatric musculoskeletal assessment, particularly in patients with documented risk factors for DDH.1,3,4 Delay in diagnosis of DDH, it should be noted, is a relatively common complaint in pediatric medical malpractice lawsuits; until the early 2000s, this condition represented about 75% of claims in one medical malpractice database.The decrease in claims has been attributed to better awareness and earlier diagnosis of DDH. 17

Continue for the diagnosis >>

DIAGNOSIS

A positive Ortolani or Barlow sign is diagnostic and warrants prompt orthopedic referral (Figure 5). If physical examination results are equivocal or inconclusive, follow-up at two weeks is recommended, with continued routine follow-up until walking is achieved. Patients with persistent equivocal findings at the two-week follow-up warrant ultrasound at age 3 to 4 weeks or orthopedic referral. Infants with significant risk factors, particularly breech presentation at birth, should also undergo imaging.18 AAP recommends ultrasound at age 6 weeks or radiograph after 4 months of age.1,18 AAOS recommends performing an imaging study before age 6 months when at least one of the following risk factors is present: breech presentation, positive family history of DDH, or previous clinical instability (moderate level of evidence).3

IMAGING

Ultrasound is the diagnostic test of choice for infants because radiographs have limited value until the femoral heads begin to ossify at age 4 to 6 months.18 Ultrasonography allows for visualization of the cartilaginous portion of the acetabulum and femoral head.1 Dynamic stressing is performed during ultrasound to assess the level of hip stability. A provider trained in ultrasound will measure the depth of the acetabulum and identify any potential laxity or instability of the hip joint. Accuracy of these findings is largely dependent on the experience and skill of the examiner.

Ultrasound evaluation is not recommended until after age 3 to 4 weeks. Earlier findings may include mild laxity and immature morphology of the acetabulum, which often resolve spontaneously.1,18 Use of ultrasound is currently recommended only to confirm diagnostic suspicion, based on clinical findings, or for infants with significant risk factors.18 Universal ultrasound screening in newborns is not recommended and would incur unnecessary costs.1,3,9 Plain radiographs are used after age 4 months to confirm a diagnosis of DDH or to assess for residual dysplasia.3,18

Continue for management >>

MANAGEMENT

Once hip dysplasia is suggested by physical exam or imaging study, the child’s subsequent care should be provided by an orthopedic specialist with experience in treating this condition. Treatment is preferably initiated before age 6 weeks.12 The specifics of treatment are largely based on age at diagnosis and the severity of dysplasia.

The goal of treatment is to maintain the hips in a stable position with the femoral head well covered by the acetabulum. This will improve anatomic development and function. Early clinical diagnosis is often sufficient to justify initiating conservative treatment; additionally, early detection of DDH can considerably reduce the need for surgical intervention.12 Although the potential for spontaneous resolution is high, the consequences associated with delay in care can be significant.