User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Bisphosphonates may have limited ‘protective’ effect against knee OA progression

New data from the National Institutes of Health–funded Osteoarthritis Initiative suggest that, in some women at least, taking bisphosphonates may help to reduce the chances that there will be radiographic progression of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

In a propensity-matched cohort analysis, women who had a Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grade of less than 2 and who used bisphosphonates were half as likely as those who did not use bisphosphonates to have radiographic OA progression at 2 years (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.79). Radiographic OA progression has been defined as a one-step increase in the KL grade.

While the association appeared even stronger in women with a KL grade less than 2 and who were not overweight (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.26-0.92), bisphosphonate use was not associated with radiographic OA progression in women with a higher (≥2) KL grade (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.83-1.35).

“In all analyses, the effect of bisphosphonates was larger in radiographic-disease-naive individuals, suggesting protection using bisphosphonates may be more profound in those who do not already have evidence of knee damage or who have mild disease, and once damage occurs, bisphosphonate use may not have much effect,” Kaleen N. Hayes, PharmD, of the University of Toronto and her coauthors reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

“Our study was the first to our knowledge to examine bisphosphonate exposure effects in different disease severity subgroups and obesity classifications using a rigorous, propensity-matched time-to-event analysis that uniquely addresses confounding by indication,” Dr. Hayes and her team wrote.

Furthermore, they noted that extensive sensitivity analyses, which included redoing the primary analyses to look at statin use, showed that their main conclusions were unchanged and that this helped account for any potential residual confounding, healthy-user bias, or exposure misclassification.

Study details

The Osteoarthritis Initiative is a 10-year longitudinal cohort study conducted at four clinical sites in the United States and recruited men and women aged 45-75 years over a 2-year period starting in 2004. Dr. Hayes and her coauthors restricted their analyses to women 50 years and older. Their study population consisted of 344 bisphosphonate users and 344 bisphosphonate nonusers.

The main bisphosphonate being taken was alendronate (69%), and the average duration of bisphosphonate use was 3.3 years, but no significant effect of duration of use on radiographic progression was found.

The women were followed until the first radiographic OA progression, or the first missed visit or end of the 2-year follow-up period.

Overall, 95 (13.8%) of the 688 women included in the analysis experienced radiographic OA progression. Of those, 27 (3.9%) had a KL grade of less than 2 and 68 (9.8%) had a KL grade of 2 or greater. Ten women with KL less than 2 and 27 women with KL or 2 or greater were taking bisphosphonates at their baseline visit.

“Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that non-users and users with a baseline KL grade of 0 or 1 had 2-year risks of progression of 10.5% and 5.9%, respectively, whereas non-users and users with a baseline KL grade of 2 or 3 had 2-year of these women risks of progression of 23.0% and 23.5%, respectively,” reported the authors.

Before propensity score matching, Dr. Hayes and her colleagues observed that women taking bisphosphonates were older, had lower body weight and a higher prevalence of any fracture or hip and vertebral fractures, and were also more likely be White, compared with non-users. “In addition, bisphosphonate-users appeared to be healthier than non-users, as suggested by a lower smoking prevalence, lower average baseline KL grade, lower diabetes prevalence, and higher multivitamin use (a healthy-user proxy),” they acknowledged.

Results in perspective

“The key thing that I’m concerned about when I see something like bisphosphonates and osteoarthritis is just how well confounding has been addressed,” commented Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University and chief of rheumatology at Boston Medical Center, in an interview.

“So are there factors other than the bisphosphonates themselves that might explain the findings? It looks like they’ve taken into account a lot of important things that one would consider for trying to get the two groups to look as similar as possible,” she added. Dr. Neogi queried, however, if body mass index had been suitably been adjusted for even after propensity score matching.

“The effect estimate is quite large, so I do think there is some confounding. So I would feel comfortable saying that there’s a signal here for bisphosphonates in reducing the risk of progression among those who do not have radiographic OA at baseline,” Dr. Neogi observed.

“The context of all this is that there have been large, well-designed, randomized control trials of oral bisphosphonates from years ago that did not find any benefit of bisphosphonates in [terms of] radiographic OA progression,” Dr. Neogi explained.

In the Knee OA Structural Arthritis (KOSTAR) study, now considered “quite a large landmark study,” the efficacy of risedronate in providing symptom relief and slowing disease progression was studied in almost 2,500 patients. “They saw some improvements in signs and symptoms, but risedronate did not significantly reduce radiographic progression. [However] there were some signals on biomarkers,” Dr. Neogi said.

One of the issues is that radiographs are too insensitive to pick up early bone changes in OA, a fact not missed by Dr. Hayes et al. More recent research has thus looked to using more sensitive imaging methods, such as CT and MRI, such as a recent study published in JAMA looking at the use of intravenous zoledronic acid on bone marrow lesions and cartilage volume. The results did not show any benefit of bisphosphonate use over 2 years.

“So even though we thought the MRI might provide a better way to detect a signal, it hasn’t panned out,” Dr. Neogi said.

But that’s not to say that there isn’t still a signal. Dr. Neogi’s most recent research has been using MRI to look at bone marrow lesion volume in women who were newly starting bisphosphonate therapy versus those who were not, and this has been just been accepted for publication.

“We found no difference in bone marrow lesion volume between the two groups. But in the women who had bone marrow lesions at baseline, there was a statistically significant greater proportion of women on bisphosphonates having a decrease in bone marrow lesion volume than the non-initiators,” she said.

So is there evidence that putting more women on bisphosphonates could prevent OA? “I’m not sure that you would be able to say that this should be something that all postmenopausal women should be on,” Dr. Neogi said.

“There’s a theoretical risk that has not been formally studied that, if you diminish bone turnover and you get more and more mineralization occurring, the bone potentially may have altered mechanical properties, become stiffer and, over the long term, that might not be good for OA.”

She added that, if there is already a clear clinical indication for bisphosphonate use, however, such as older women who have had a fracture and who should be on a bisphosphonate anyway, then “a bisphosphonate has the theoretical potential additional benefit for their osteoarthritis.”

The authors and Dr. Neogi had no conflicts of interest or relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Hayes KN et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 July 14. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4133.

New data from the National Institutes of Health–funded Osteoarthritis Initiative suggest that, in some women at least, taking bisphosphonates may help to reduce the chances that there will be radiographic progression of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

In a propensity-matched cohort analysis, women who had a Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grade of less than 2 and who used bisphosphonates were half as likely as those who did not use bisphosphonates to have radiographic OA progression at 2 years (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.79). Radiographic OA progression has been defined as a one-step increase in the KL grade.

While the association appeared even stronger in women with a KL grade less than 2 and who were not overweight (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.26-0.92), bisphosphonate use was not associated with radiographic OA progression in women with a higher (≥2) KL grade (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.83-1.35).

“In all analyses, the effect of bisphosphonates was larger in radiographic-disease-naive individuals, suggesting protection using bisphosphonates may be more profound in those who do not already have evidence of knee damage or who have mild disease, and once damage occurs, bisphosphonate use may not have much effect,” Kaleen N. Hayes, PharmD, of the University of Toronto and her coauthors reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

“Our study was the first to our knowledge to examine bisphosphonate exposure effects in different disease severity subgroups and obesity classifications using a rigorous, propensity-matched time-to-event analysis that uniquely addresses confounding by indication,” Dr. Hayes and her team wrote.

Furthermore, they noted that extensive sensitivity analyses, which included redoing the primary analyses to look at statin use, showed that their main conclusions were unchanged and that this helped account for any potential residual confounding, healthy-user bias, or exposure misclassification.

Study details

The Osteoarthritis Initiative is a 10-year longitudinal cohort study conducted at four clinical sites in the United States and recruited men and women aged 45-75 years over a 2-year period starting in 2004. Dr. Hayes and her coauthors restricted their analyses to women 50 years and older. Their study population consisted of 344 bisphosphonate users and 344 bisphosphonate nonusers.

The main bisphosphonate being taken was alendronate (69%), and the average duration of bisphosphonate use was 3.3 years, but no significant effect of duration of use on radiographic progression was found.

The women were followed until the first radiographic OA progression, or the first missed visit or end of the 2-year follow-up period.

Overall, 95 (13.8%) of the 688 women included in the analysis experienced radiographic OA progression. Of those, 27 (3.9%) had a KL grade of less than 2 and 68 (9.8%) had a KL grade of 2 or greater. Ten women with KL less than 2 and 27 women with KL or 2 or greater were taking bisphosphonates at their baseline visit.

“Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that non-users and users with a baseline KL grade of 0 or 1 had 2-year risks of progression of 10.5% and 5.9%, respectively, whereas non-users and users with a baseline KL grade of 2 or 3 had 2-year of these women risks of progression of 23.0% and 23.5%, respectively,” reported the authors.

Before propensity score matching, Dr. Hayes and her colleagues observed that women taking bisphosphonates were older, had lower body weight and a higher prevalence of any fracture or hip and vertebral fractures, and were also more likely be White, compared with non-users. “In addition, bisphosphonate-users appeared to be healthier than non-users, as suggested by a lower smoking prevalence, lower average baseline KL grade, lower diabetes prevalence, and higher multivitamin use (a healthy-user proxy),” they acknowledged.

Results in perspective

“The key thing that I’m concerned about when I see something like bisphosphonates and osteoarthritis is just how well confounding has been addressed,” commented Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University and chief of rheumatology at Boston Medical Center, in an interview.

“So are there factors other than the bisphosphonates themselves that might explain the findings? It looks like they’ve taken into account a lot of important things that one would consider for trying to get the two groups to look as similar as possible,” she added. Dr. Neogi queried, however, if body mass index had been suitably been adjusted for even after propensity score matching.

“The effect estimate is quite large, so I do think there is some confounding. So I would feel comfortable saying that there’s a signal here for bisphosphonates in reducing the risk of progression among those who do not have radiographic OA at baseline,” Dr. Neogi observed.

“The context of all this is that there have been large, well-designed, randomized control trials of oral bisphosphonates from years ago that did not find any benefit of bisphosphonates in [terms of] radiographic OA progression,” Dr. Neogi explained.

In the Knee OA Structural Arthritis (KOSTAR) study, now considered “quite a large landmark study,” the efficacy of risedronate in providing symptom relief and slowing disease progression was studied in almost 2,500 patients. “They saw some improvements in signs and symptoms, but risedronate did not significantly reduce radiographic progression. [However] there were some signals on biomarkers,” Dr. Neogi said.

One of the issues is that radiographs are too insensitive to pick up early bone changes in OA, a fact not missed by Dr. Hayes et al. More recent research has thus looked to using more sensitive imaging methods, such as CT and MRI, such as a recent study published in JAMA looking at the use of intravenous zoledronic acid on bone marrow lesions and cartilage volume. The results did not show any benefit of bisphosphonate use over 2 years.

“So even though we thought the MRI might provide a better way to detect a signal, it hasn’t panned out,” Dr. Neogi said.

But that’s not to say that there isn’t still a signal. Dr. Neogi’s most recent research has been using MRI to look at bone marrow lesion volume in women who were newly starting bisphosphonate therapy versus those who were not, and this has been just been accepted for publication.

“We found no difference in bone marrow lesion volume between the two groups. But in the women who had bone marrow lesions at baseline, there was a statistically significant greater proportion of women on bisphosphonates having a decrease in bone marrow lesion volume than the non-initiators,” she said.

So is there evidence that putting more women on bisphosphonates could prevent OA? “I’m not sure that you would be able to say that this should be something that all postmenopausal women should be on,” Dr. Neogi said.

“There’s a theoretical risk that has not been formally studied that, if you diminish bone turnover and you get more and more mineralization occurring, the bone potentially may have altered mechanical properties, become stiffer and, over the long term, that might not be good for OA.”

She added that, if there is already a clear clinical indication for bisphosphonate use, however, such as older women who have had a fracture and who should be on a bisphosphonate anyway, then “a bisphosphonate has the theoretical potential additional benefit for their osteoarthritis.”

The authors and Dr. Neogi had no conflicts of interest or relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Hayes KN et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 July 14. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4133.

New data from the National Institutes of Health–funded Osteoarthritis Initiative suggest that, in some women at least, taking bisphosphonates may help to reduce the chances that there will be radiographic progression of knee osteoarthritis (OA).

In a propensity-matched cohort analysis, women who had a Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) grade of less than 2 and who used bisphosphonates were half as likely as those who did not use bisphosphonates to have radiographic OA progression at 2 years (hazard ratio, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.35-0.79). Radiographic OA progression has been defined as a one-step increase in the KL grade.

While the association appeared even stronger in women with a KL grade less than 2 and who were not overweight (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.26-0.92), bisphosphonate use was not associated with radiographic OA progression in women with a higher (≥2) KL grade (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 0.83-1.35).

“In all analyses, the effect of bisphosphonates was larger in radiographic-disease-naive individuals, suggesting protection using bisphosphonates may be more profound in those who do not already have evidence of knee damage or who have mild disease, and once damage occurs, bisphosphonate use may not have much effect,” Kaleen N. Hayes, PharmD, of the University of Toronto and her coauthors reported in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

“Our study was the first to our knowledge to examine bisphosphonate exposure effects in different disease severity subgroups and obesity classifications using a rigorous, propensity-matched time-to-event analysis that uniquely addresses confounding by indication,” Dr. Hayes and her team wrote.

Furthermore, they noted that extensive sensitivity analyses, which included redoing the primary analyses to look at statin use, showed that their main conclusions were unchanged and that this helped account for any potential residual confounding, healthy-user bias, or exposure misclassification.

Study details

The Osteoarthritis Initiative is a 10-year longitudinal cohort study conducted at four clinical sites in the United States and recruited men and women aged 45-75 years over a 2-year period starting in 2004. Dr. Hayes and her coauthors restricted their analyses to women 50 years and older. Their study population consisted of 344 bisphosphonate users and 344 bisphosphonate nonusers.

The main bisphosphonate being taken was alendronate (69%), and the average duration of bisphosphonate use was 3.3 years, but no significant effect of duration of use on radiographic progression was found.

The women were followed until the first radiographic OA progression, or the first missed visit or end of the 2-year follow-up period.

Overall, 95 (13.8%) of the 688 women included in the analysis experienced radiographic OA progression. Of those, 27 (3.9%) had a KL grade of less than 2 and 68 (9.8%) had a KL grade of 2 or greater. Ten women with KL less than 2 and 27 women with KL or 2 or greater were taking bisphosphonates at their baseline visit.

“Kaplan-Meier analysis indicated that non-users and users with a baseline KL grade of 0 or 1 had 2-year risks of progression of 10.5% and 5.9%, respectively, whereas non-users and users with a baseline KL grade of 2 or 3 had 2-year of these women risks of progression of 23.0% and 23.5%, respectively,” reported the authors.

Before propensity score matching, Dr. Hayes and her colleagues observed that women taking bisphosphonates were older, had lower body weight and a higher prevalence of any fracture or hip and vertebral fractures, and were also more likely be White, compared with non-users. “In addition, bisphosphonate-users appeared to be healthier than non-users, as suggested by a lower smoking prevalence, lower average baseline KL grade, lower diabetes prevalence, and higher multivitamin use (a healthy-user proxy),” they acknowledged.

Results in perspective

“The key thing that I’m concerned about when I see something like bisphosphonates and osteoarthritis is just how well confounding has been addressed,” commented Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University and chief of rheumatology at Boston Medical Center, in an interview.

“So are there factors other than the bisphosphonates themselves that might explain the findings? It looks like they’ve taken into account a lot of important things that one would consider for trying to get the two groups to look as similar as possible,” she added. Dr. Neogi queried, however, if body mass index had been suitably been adjusted for even after propensity score matching.

“The effect estimate is quite large, so I do think there is some confounding. So I would feel comfortable saying that there’s a signal here for bisphosphonates in reducing the risk of progression among those who do not have radiographic OA at baseline,” Dr. Neogi observed.

“The context of all this is that there have been large, well-designed, randomized control trials of oral bisphosphonates from years ago that did not find any benefit of bisphosphonates in [terms of] radiographic OA progression,” Dr. Neogi explained.

In the Knee OA Structural Arthritis (KOSTAR) study, now considered “quite a large landmark study,” the efficacy of risedronate in providing symptom relief and slowing disease progression was studied in almost 2,500 patients. “They saw some improvements in signs and symptoms, but risedronate did not significantly reduce radiographic progression. [However] there were some signals on biomarkers,” Dr. Neogi said.

One of the issues is that radiographs are too insensitive to pick up early bone changes in OA, a fact not missed by Dr. Hayes et al. More recent research has thus looked to using more sensitive imaging methods, such as CT and MRI, such as a recent study published in JAMA looking at the use of intravenous zoledronic acid on bone marrow lesions and cartilage volume. The results did not show any benefit of bisphosphonate use over 2 years.

“So even though we thought the MRI might provide a better way to detect a signal, it hasn’t panned out,” Dr. Neogi said.

But that’s not to say that there isn’t still a signal. Dr. Neogi’s most recent research has been using MRI to look at bone marrow lesion volume in women who were newly starting bisphosphonate therapy versus those who were not, and this has been just been accepted for publication.

“We found no difference in bone marrow lesion volume between the two groups. But in the women who had bone marrow lesions at baseline, there was a statistically significant greater proportion of women on bisphosphonates having a decrease in bone marrow lesion volume than the non-initiators,” she said.

So is there evidence that putting more women on bisphosphonates could prevent OA? “I’m not sure that you would be able to say that this should be something that all postmenopausal women should be on,” Dr. Neogi said.

“There’s a theoretical risk that has not been formally studied that, if you diminish bone turnover and you get more and more mineralization occurring, the bone potentially may have altered mechanical properties, become stiffer and, over the long term, that might not be good for OA.”

She added that, if there is already a clear clinical indication for bisphosphonate use, however, such as older women who have had a fracture and who should be on a bisphosphonate anyway, then “a bisphosphonate has the theoretical potential additional benefit for their osteoarthritis.”

The authors and Dr. Neogi had no conflicts of interest or relationships to disclose.

SOURCE: Hayes KN et al. J Bone Miner Res. 2020 July 14. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.4133.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH

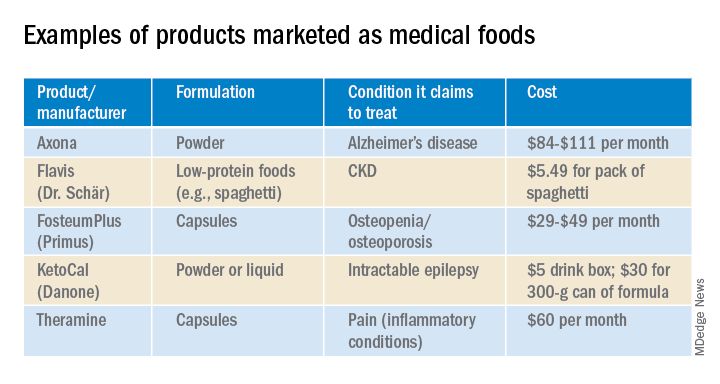

Move over supplements, here come medical foods

As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

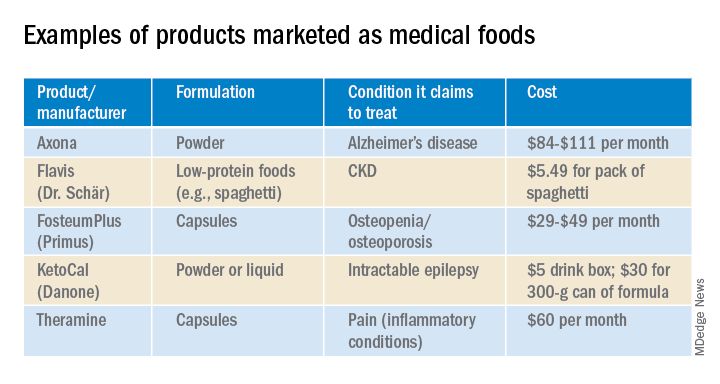

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

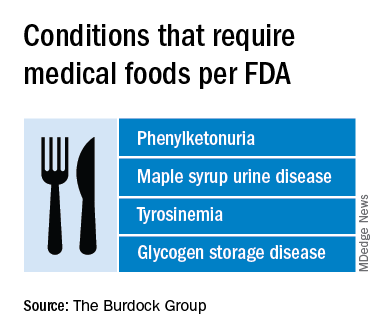

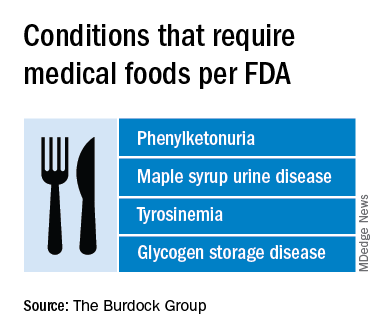

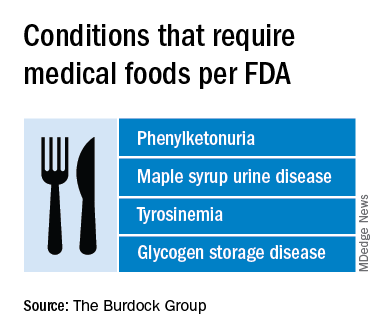

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.

Manufacturers and the FDA differ

One example of a product about which regulators and manufacturers differ is Theramine, which is described as “specially designed to supply the nervous system with the fuel it needs to meet the altered metabolic requirements of chronic pain and inflammatory disorders.”

It is not considered a medical food by the FDA, and the company has had numerous discussions with the agency about their diverging views, according to Mr. Charuvastra. “We’ve had our warning letters and we’ve had our sit downs, and we just had an inspection.”

Targeted Medical Pharma continues to market its products as medical foods but steers away from making any claims that they are like drugs, he said.

Confusion about medical foods has been exposed in the California Workers’ Compensation System by Leslie Wilson, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco. They found that physicians regularly wrote medical food prescriptions for non–FDA-approved uses and that the system reimbursed the majority of the products at a cost of $15.5 million from 2011 to 2013. More than half of these prescriptions were for Theramine.

Dr. Wilson reported that, for most products, no evidence supported effectiveness, and they were frequently mislabeled – for all 36 that were studied, submissions for reimbursement were made using a National Drug Code, an impossibility because medical foods are not drugs, and 14 were labeled “Rx only.”

Big-name companies joining in

The FDA does not keep a list of approved medical foods or manufacturers. Both small businesses and big food companies like Danone, Nestlé, and Abbott are players. Most products are sold online.

In the United States, Danone’s Nutricia division sells formulas and low-protein foods for IEMs. They also sell Ketocal, a powder or ready-to-drink liquid that is pitched as a balanced medical food to simplify and optimize the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy. Yet the FDA does not include epilepsy among the conditions that medical foods can treat.

Nestlé sells traditional medical foods for IEMs and also markets a range of what it calls nutritional therapies for such conditions as irritable bowel syndrome and dysphagia.

Nestlé is a minority shareholder in Axona, a product originally developed by Accera (Cerecin as of 2018). Jacquelyn Campo, senior director of global communications at Nestlé Health Sciences, said that the company is not actively involved in the operations management of Cerecin. However, on its website, Nestlé touts Axona, which is only available in the United States, as a “medical food” that “is intended for the clinical dietary management of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.” The Axona site claims that the main ingredient, caprylic triglyceride, is broken down into ketones that provide fuel to treat cerebral hypometabolism, a precursor to Alzheimer disease. In a 2009 study, daily dosing of a preliminary formulation was associated with improved cognitive performance compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.

In 2013, the FDA warned Accera that it was misbranding Axona as a medical food and that the therapeutic claims the company was making would make the product an unapproved drug. Ms. Campo said Nestlé is aware of the agency’s warning, but added, “to our knowledge, Cerecin provided answers to the issues raised by the FDA.”

With the goal of getting drug approval, Accera went on to test a tweaked formulation in a 400-patient randomized, placebo-controlled trial called NOURISH AD that ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Axona is still marketed as a medical food. It costs about $100 for a month’s supply.

Repeated requests for comment from Cerecin were not answered. Danielle Schor, an FDA spokesperson, said the agency will not discuss the status of individual products.

More disputes and insurance coverage

Mary Ann DeMarco, executive director of sales and marketing for the Scottsdale, Ariz.–based medical food maker Primus Pharmaceuticals, said the company believes its products fit within the FDA’s medical foods rubric.

These include Fosteum Plus capsules, which it markets “for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes of osteopenia and osteoporosis.” The capsules contain a combination of genistein, zinc, calcium, phosphate, vitamin K2, and vitamin D. As proof of effectiveness, the company cites clinical data on some of the ingredients – not the product itself.

Primus has run afoul of the FDA before when it similarly positioned another product, called Limbrel, as a medical food for osteoarthritis. From 2007 to 2017, the FDA received 194 adverse event reports associated with Limbrel, including reports of drug-induced liver injury, pancreatitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In December 2017, the agency urged Primus to recall Limbrel, a move that it said was “necessary to protect the public health and welfare.” Primus withdrew the product but laid out a defense of Limbrel on a devoted website.

The FDA would not comment any further, said Ms. Schor. Ms. DeMarco said that Primus is working with the FDA to bring Limbrel back to market.

A lack of insurance coverage – even for approved medical foods for IEMs – has frustrated advocates, parents, and manufacturers. They are putting their weight behind the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, which would mandate public and private payer coverage of medical foods for IEMs and digestive conditions such as Crohn disease. That 2019 House bill has 56 cosponsors; there is no Senate companion bill.

“If you can get reimbursement, it really makes the market,” for Primus and the other manufacturers, Mr. Hyman said.

Primus Pharmaceuticals has launched its own campaign, Cover My Medical Foods, to enlist consumers and others to the cause.

Partnering with advocates

Although its low-protein breads, pastas, and baking products are not considered medical foods by the FDA, Dr. Schär is marketing them as such in the United States. They are trying to make a mark in CKD, according to Ms. Donnelly. She added that Dr. Schär has been successful in Europe, where nutrition therapy is more integrated in the health care system.

In 2019, Flavis and the National Kidney Foundation joined forces to raise awareness of nutritional interventions and to build enthusiasm for the Flavis products. The partnership has now ended, mostly because Flavis could no longer afford it, according to Ms. Donnelly.

“Information on diet and nutrition is the most requested subject matter from the NKF,” said Anthony Gucciardo, senior vice president of strategic partnerships at the foundation. The partnership “has never been necessarily about promoting their products per se; it’s promoting a healthy diet and really a diet specific for CKD.”

The NKF developed cobranded materials on low-protein foods for physicians and a teaching tool they could use with patients. Consumers could access nutrition information and a discount on Flavis products on a dedicated webpage. The foundation didn’t describe the low-protein products as medical foods, said Mr. Gucciardo, even if Flavis promoted them as such.

In patients with CKD, dietary management can help prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. Although Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy – in which patients receive personalized assessments and dietary advice – uptake is abysmally low, according to a 2018 study.

Dr. Burdock thinks low-protein foods for CKD do meet the FDA’s criteria for a medical food but that the agency might not necessarily agree with him. The FDA would not comment.

Physician beware

When it comes to medical foods, the FDA has often looked the other way because the ingredients may already have been proven safe and the danger to an individual or to the public’s health is relatively low, according to Dr. Burdock and Mr. Hyman.

However, if the agency “feels that a medical food will prevent people from seeking medical care or there is potential to defraud the public, it is justified in taking action against the company,” said Dr. Burdock.

According to Dr. Wilson, the pharmacist who reported on the inappropriate medical food prescriptions in the California system, the FDA could help by creating a list of approved medical foods. Physicians should take time to learn about the difference between medical foods and supplements, she said, adding that they should also not hesitate to “question the veracity of the claims for them.”

Ms. Guggenheim believed doctors need to know that, for the most part, these are not FDA-approved products. She emphasized the importance of evaluating the products and looking at the data of their impact on a disease or condition.

“Many of these companies strongly believe that the products work and help people, so clinicians need to be very data driven,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.

Manufacturers and the FDA differ

One example of a product about which regulators and manufacturers differ is Theramine, which is described as “specially designed to supply the nervous system with the fuel it needs to meet the altered metabolic requirements of chronic pain and inflammatory disorders.”

It is not considered a medical food by the FDA, and the company has had numerous discussions with the agency about their diverging views, according to Mr. Charuvastra. “We’ve had our warning letters and we’ve had our sit downs, and we just had an inspection.”

Targeted Medical Pharma continues to market its products as medical foods but steers away from making any claims that they are like drugs, he said.

Confusion about medical foods has been exposed in the California Workers’ Compensation System by Leslie Wilson, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco. They found that physicians regularly wrote medical food prescriptions for non–FDA-approved uses and that the system reimbursed the majority of the products at a cost of $15.5 million from 2011 to 2013. More than half of these prescriptions were for Theramine.

Dr. Wilson reported that, for most products, no evidence supported effectiveness, and they were frequently mislabeled – for all 36 that were studied, submissions for reimbursement were made using a National Drug Code, an impossibility because medical foods are not drugs, and 14 were labeled “Rx only.”

Big-name companies joining in

The FDA does not keep a list of approved medical foods or manufacturers. Both small businesses and big food companies like Danone, Nestlé, and Abbott are players. Most products are sold online.

In the United States, Danone’s Nutricia division sells formulas and low-protein foods for IEMs. They also sell Ketocal, a powder or ready-to-drink liquid that is pitched as a balanced medical food to simplify and optimize the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy. Yet the FDA does not include epilepsy among the conditions that medical foods can treat.

Nestlé sells traditional medical foods for IEMs and also markets a range of what it calls nutritional therapies for such conditions as irritable bowel syndrome and dysphagia.

Nestlé is a minority shareholder in Axona, a product originally developed by Accera (Cerecin as of 2018). Jacquelyn Campo, senior director of global communications at Nestlé Health Sciences, said that the company is not actively involved in the operations management of Cerecin. However, on its website, Nestlé touts Axona, which is only available in the United States, as a “medical food” that “is intended for the clinical dietary management of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.” The Axona site claims that the main ingredient, caprylic triglyceride, is broken down into ketones that provide fuel to treat cerebral hypometabolism, a precursor to Alzheimer disease. In a 2009 study, daily dosing of a preliminary formulation was associated with improved cognitive performance compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.

In 2013, the FDA warned Accera that it was misbranding Axona as a medical food and that the therapeutic claims the company was making would make the product an unapproved drug. Ms. Campo said Nestlé is aware of the agency’s warning, but added, “to our knowledge, Cerecin provided answers to the issues raised by the FDA.”

With the goal of getting drug approval, Accera went on to test a tweaked formulation in a 400-patient randomized, placebo-controlled trial called NOURISH AD that ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Axona is still marketed as a medical food. It costs about $100 for a month’s supply.

Repeated requests for comment from Cerecin were not answered. Danielle Schor, an FDA spokesperson, said the agency will not discuss the status of individual products.

More disputes and insurance coverage

Mary Ann DeMarco, executive director of sales and marketing for the Scottsdale, Ariz.–based medical food maker Primus Pharmaceuticals, said the company believes its products fit within the FDA’s medical foods rubric.

These include Fosteum Plus capsules, which it markets “for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes of osteopenia and osteoporosis.” The capsules contain a combination of genistein, zinc, calcium, phosphate, vitamin K2, and vitamin D. As proof of effectiveness, the company cites clinical data on some of the ingredients – not the product itself.

Primus has run afoul of the FDA before when it similarly positioned another product, called Limbrel, as a medical food for osteoarthritis. From 2007 to 2017, the FDA received 194 adverse event reports associated with Limbrel, including reports of drug-induced liver injury, pancreatitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In December 2017, the agency urged Primus to recall Limbrel, a move that it said was “necessary to protect the public health and welfare.” Primus withdrew the product but laid out a defense of Limbrel on a devoted website.

The FDA would not comment any further, said Ms. Schor. Ms. DeMarco said that Primus is working with the FDA to bring Limbrel back to market.

A lack of insurance coverage – even for approved medical foods for IEMs – has frustrated advocates, parents, and manufacturers. They are putting their weight behind the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, which would mandate public and private payer coverage of medical foods for IEMs and digestive conditions such as Crohn disease. That 2019 House bill has 56 cosponsors; there is no Senate companion bill.

“If you can get reimbursement, it really makes the market,” for Primus and the other manufacturers, Mr. Hyman said.

Primus Pharmaceuticals has launched its own campaign, Cover My Medical Foods, to enlist consumers and others to the cause.

Partnering with advocates

Although its low-protein breads, pastas, and baking products are not considered medical foods by the FDA, Dr. Schär is marketing them as such in the United States. They are trying to make a mark in CKD, according to Ms. Donnelly. She added that Dr. Schär has been successful in Europe, where nutrition therapy is more integrated in the health care system.

In 2019, Flavis and the National Kidney Foundation joined forces to raise awareness of nutritional interventions and to build enthusiasm for the Flavis products. The partnership has now ended, mostly because Flavis could no longer afford it, according to Ms. Donnelly.

“Information on diet and nutrition is the most requested subject matter from the NKF,” said Anthony Gucciardo, senior vice president of strategic partnerships at the foundation. The partnership “has never been necessarily about promoting their products per se; it’s promoting a healthy diet and really a diet specific for CKD.”

The NKF developed cobranded materials on low-protein foods for physicians and a teaching tool they could use with patients. Consumers could access nutrition information and a discount on Flavis products on a dedicated webpage. The foundation didn’t describe the low-protein products as medical foods, said Mr. Gucciardo, even if Flavis promoted them as such.

In patients with CKD, dietary management can help prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. Although Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy – in which patients receive personalized assessments and dietary advice – uptake is abysmally low, according to a 2018 study.

Dr. Burdock thinks low-protein foods for CKD do meet the FDA’s criteria for a medical food but that the agency might not necessarily agree with him. The FDA would not comment.

Physician beware

When it comes to medical foods, the FDA has often looked the other way because the ingredients may already have been proven safe and the danger to an individual or to the public’s health is relatively low, according to Dr. Burdock and Mr. Hyman.

However, if the agency “feels that a medical food will prevent people from seeking medical care or there is potential to defraud the public, it is justified in taking action against the company,” said Dr. Burdock.

According to Dr. Wilson, the pharmacist who reported on the inappropriate medical food prescriptions in the California system, the FDA could help by creating a list of approved medical foods. Physicians should take time to learn about the difference between medical foods and supplements, she said, adding that they should also not hesitate to “question the veracity of the claims for them.”

Ms. Guggenheim believed doctors need to know that, for the most part, these are not FDA-approved products. She emphasized the importance of evaluating the products and looking at the data of their impact on a disease or condition.

“Many of these companies strongly believe that the products work and help people, so clinicians need to be very data driven,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

As the Food and Drug Administration focuses on other issues, companies, both big and small, are looking to boost physician and consumer interest in their “medical foods” – products that fall somewhere between drugs and supplements and promise to mitigate symptoms, or even address underlying pathologies, of a range of diseases.

Manufacturers now market an array of medical foods, ranging from powders and capsules for Alzheimer disease to low-protein spaghetti for chronic kidney disease (CKD). The FDA has not been completely absent; it takes a narrow view of what medical conditions qualify for treatment with food products and has warned some manufacturers that their misbranded products are acting more like unapproved drugs.

By the FDA’s definition, medical food is limited to products that provide crucial therapy for patients with inborn errors of metabolism (IEM). An example is specialized baby formula for infants with phenylketonuria. Unlike supplements, medical foods are supposed to be used under the supervision of a physician. This has prompted some sales reps to turn up in the clinic, and most manufacturers have online approval forms for doctors to sign. Manufacturers, advisers, and regulators were interviewed for a closer look at this burgeoning industry.

The market

The global market for medical foods – about $18 billion in 2019 – is expected to grow steadily in the near future. It is drawing more interest, especially in Europe, where medical foods are more accepted by physicians and consumers, Meghan Donnelly, MS, RDN, said in an interview. She is a registered dietitian who conducts physician outreach in the United States for Flavis, a division of Dr. Schär. That company, based in northern Italy, started out targeting IEMs but now also sells gluten-free foods for celiac disease and low-protein foods for CKD.

It is still a niche market in the United States – and isn’t likely to ever approach the size of the supplement market, according to Marcus Charuvastra, the managing director of Targeted Medical Pharma, which markets Theramine capsules for pain management, among many other products. But it could still be a big win for a manufacturer if they get a small slice of a big market, such as for Alzheimer disease.

Defining medical food

According to an update of the Orphan Drug Act in 1988, a medical food is “a food which is formulated to be consumed or administered enterally under the supervision of a physician and which is intended for the specific dietary management of a disease or condition for which distinctive nutritional requirements, based on recognized scientific principles, are established by medical evaluation.” The FDA issued regulations to accompany that law in 1993 but has since only issued a guidance document that is not legally binding.

Medical foods are not drugs and they are not supplements (the latter are intended only for healthy people). The FDA doesn’t require formal approval of a medical food, but, by law, the ingredients must be generally recognized as safe, and manufacturers must follow good manufacturing practices. However, the agency has taken a narrow view of what conditions require medical foods.

Policing medical foods hasn’t been a priority for the FDA, which is why there has been a proliferation of products that don’t meet the FDA’s view of the statutory definition of medical foods, according to Miriam Guggenheim, a food and drug law attorney in Washington, D.C. The FDA usually takes enforcement action when it sees a risk to the public’s health.

The agency’s stance has led to confusion – among manufacturers, physicians, consumers, and even regulators – making the market a kind of Wild West, according to Paul Hyman, a Washington, D.C.–based attorney who has represented medical food companies.

George A. Burdock, PhD, an Orlando-based regulatory consultant who has worked with medical food makers, believes the FDA will be forced to expand their narrow definition. He foresees a reconsideration of many medical food products in light of an October 2019 White House executive order prohibiting federal agencies from issuing guidance in lieu of rules.

Manufacturers and the FDA differ

One example of a product about which regulators and manufacturers differ is Theramine, which is described as “specially designed to supply the nervous system with the fuel it needs to meet the altered metabolic requirements of chronic pain and inflammatory disorders.”

It is not considered a medical food by the FDA, and the company has had numerous discussions with the agency about their diverging views, according to Mr. Charuvastra. “We’ve had our warning letters and we’ve had our sit downs, and we just had an inspection.”

Targeted Medical Pharma continues to market its products as medical foods but steers away from making any claims that they are like drugs, he said.

Confusion about medical foods has been exposed in the California Workers’ Compensation System by Leslie Wilson, PhD, and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco. They found that physicians regularly wrote medical food prescriptions for non–FDA-approved uses and that the system reimbursed the majority of the products at a cost of $15.5 million from 2011 to 2013. More than half of these prescriptions were for Theramine.

Dr. Wilson reported that, for most products, no evidence supported effectiveness, and they were frequently mislabeled – for all 36 that were studied, submissions for reimbursement were made using a National Drug Code, an impossibility because medical foods are not drugs, and 14 were labeled “Rx only.”

Big-name companies joining in

The FDA does not keep a list of approved medical foods or manufacturers. Both small businesses and big food companies like Danone, Nestlé, and Abbott are players. Most products are sold online.

In the United States, Danone’s Nutricia division sells formulas and low-protein foods for IEMs. They also sell Ketocal, a powder or ready-to-drink liquid that is pitched as a balanced medical food to simplify and optimize the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy. Yet the FDA does not include epilepsy among the conditions that medical foods can treat.

Nestlé sells traditional medical foods for IEMs and also markets a range of what it calls nutritional therapies for such conditions as irritable bowel syndrome and dysphagia.

Nestlé is a minority shareholder in Axona, a product originally developed by Accera (Cerecin as of 2018). Jacquelyn Campo, senior director of global communications at Nestlé Health Sciences, said that the company is not actively involved in the operations management of Cerecin. However, on its website, Nestlé touts Axona, which is only available in the United States, as a “medical food” that “is intended for the clinical dietary management of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.” The Axona site claims that the main ingredient, caprylic triglyceride, is broken down into ketones that provide fuel to treat cerebral hypometabolism, a precursor to Alzheimer disease. In a 2009 study, daily dosing of a preliminary formulation was associated with improved cognitive performance compared with placebo in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease.

In 2013, the FDA warned Accera that it was misbranding Axona as a medical food and that the therapeutic claims the company was making would make the product an unapproved drug. Ms. Campo said Nestlé is aware of the agency’s warning, but added, “to our knowledge, Cerecin provided answers to the issues raised by the FDA.”

With the goal of getting drug approval, Accera went on to test a tweaked formulation in a 400-patient randomized, placebo-controlled trial called NOURISH AD that ultimately failed. Nevertheless, Axona is still marketed as a medical food. It costs about $100 for a month’s supply.

Repeated requests for comment from Cerecin were not answered. Danielle Schor, an FDA spokesperson, said the agency will not discuss the status of individual products.

More disputes and insurance coverage

Mary Ann DeMarco, executive director of sales and marketing for the Scottsdale, Ariz.–based medical food maker Primus Pharmaceuticals, said the company believes its products fit within the FDA’s medical foods rubric.

These include Fosteum Plus capsules, which it markets “for the clinical dietary management of the metabolic processes of osteopenia and osteoporosis.” The capsules contain a combination of genistein, zinc, calcium, phosphate, vitamin K2, and vitamin D. As proof of effectiveness, the company cites clinical data on some of the ingredients – not the product itself.

Primus has run afoul of the FDA before when it similarly positioned another product, called Limbrel, as a medical food for osteoarthritis. From 2007 to 2017, the FDA received 194 adverse event reports associated with Limbrel, including reports of drug-induced liver injury, pancreatitis, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. In December 2017, the agency urged Primus to recall Limbrel, a move that it said was “necessary to protect the public health and welfare.” Primus withdrew the product but laid out a defense of Limbrel on a devoted website.

The FDA would not comment any further, said Ms. Schor. Ms. DeMarco said that Primus is working with the FDA to bring Limbrel back to market.

A lack of insurance coverage – even for approved medical foods for IEMs – has frustrated advocates, parents, and manufacturers. They are putting their weight behind the Medical Nutrition Equity Act, which would mandate public and private payer coverage of medical foods for IEMs and digestive conditions such as Crohn disease. That 2019 House bill has 56 cosponsors; there is no Senate companion bill.

“If you can get reimbursement, it really makes the market,” for Primus and the other manufacturers, Mr. Hyman said.

Primus Pharmaceuticals has launched its own campaign, Cover My Medical Foods, to enlist consumers and others to the cause.

Partnering with advocates

Although its low-protein breads, pastas, and baking products are not considered medical foods by the FDA, Dr. Schär is marketing them as such in the United States. They are trying to make a mark in CKD, according to Ms. Donnelly. She added that Dr. Schär has been successful in Europe, where nutrition therapy is more integrated in the health care system.

In 2019, Flavis and the National Kidney Foundation joined forces to raise awareness of nutritional interventions and to build enthusiasm for the Flavis products. The partnership has now ended, mostly because Flavis could no longer afford it, according to Ms. Donnelly.

“Information on diet and nutrition is the most requested subject matter from the NKF,” said Anthony Gucciardo, senior vice president of strategic partnerships at the foundation. The partnership “has never been necessarily about promoting their products per se; it’s promoting a healthy diet and really a diet specific for CKD.”

The NKF developed cobranded materials on low-protein foods for physicians and a teaching tool they could use with patients. Consumers could access nutrition information and a discount on Flavis products on a dedicated webpage. The foundation didn’t describe the low-protein products as medical foods, said Mr. Gucciardo, even if Flavis promoted them as such.

In patients with CKD, dietary management can help prevent the progression to end-stage renal disease. Although Medicare covers medical nutrition therapy – in which patients receive personalized assessments and dietary advice – uptake is abysmally low, according to a 2018 study.

Dr. Burdock thinks low-protein foods for CKD do meet the FDA’s criteria for a medical food but that the agency might not necessarily agree with him. The FDA would not comment.

Physician beware

When it comes to medical foods, the FDA has often looked the other way because the ingredients may already have been proven safe and the danger to an individual or to the public’s health is relatively low, according to Dr. Burdock and Mr. Hyman.

However, if the agency “feels that a medical food will prevent people from seeking medical care or there is potential to defraud the public, it is justified in taking action against the company,” said Dr. Burdock.

According to Dr. Wilson, the pharmacist who reported on the inappropriate medical food prescriptions in the California system, the FDA could help by creating a list of approved medical foods. Physicians should take time to learn about the difference between medical foods and supplements, she said, adding that they should also not hesitate to “question the veracity of the claims for them.”

Ms. Guggenheim believed doctors need to know that, for the most part, these are not FDA-approved products. She emphasized the importance of evaluating the products and looking at the data of their impact on a disease or condition.

“Many of these companies strongly believe that the products work and help people, so clinicians need to be very data driven,” she said.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

EULAR gives pointers on intra-articular injection best practices

New EULAR recommendations for the intra-articular (IA) treatment of arthropathies aim to facilitate uniformity and quality of care for this mainstay of rheumatologic practice, according to a report on the new guidance that was presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, held online this year due to COVID-19.

Until now there were no official recommendations on how best to use it in everyday practice. “This is the first time that there’s been a joint effort to develop evidence-based recommendations,” Jacqueline Usón, MD, PhD, associate professor medicine at Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid, said in an interview. “Everything that we are saying is pretty logical, but it’s nice to see it put in recommendations based on evidence.”

IA therapy has been around for decades and is key for treating adults with a number of different conditions where synovitis, effusion, pain, or all three, are present, such as inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis, Dr. Usón observed during her presentation.

“Today, commonly used injectables are not only corticosteroids but also local anesthetics, hyaluronic acid, blood products, and maybe pharmaceuticals,” she said, adding that “there is a wide variation in the way intra-articular therapies are used and delivered to patients.” Health professionals also have very different views and habits depending on geographic locations and health care systems, she observed. Ironing out the variation was one of the main objectives of the recommendations.

As one of the two conveners of the EULAR task force behind the recommendations, Dr. Usón, herself a rheumatologist at University Hospital of Móstoles, pointed out that the task force brought together a range of specialties – rheumatologists, orthopedic surgeons, radiologists, nuclear medicine specialists, among others, as well as patients – to ensure that the best advice could be given.

The task force followed EULAR standard operating procedures for developing recommendations, with discussion groups, systematic literature reviews, and Delphi technique-based consensus all being employed. The literature search considered publications from 1946 up until 2019.

“We agreed on the need for more background information from health professionals and patients, so we developed two surveys: One for health professionals with 160 items, [for which] we obtained 186 responses from 26 countries; and the patient survey was made up of 44 items, translated into 10 different languages, and we obtained 200 responses,” she said.

The results of the systematic literature review and surveys were used to help form expert consensus, leading to 5 overarching principles and 11 recommendations that look at before, during, and after intra-articular therapy.

Five overarching principles

The first overarching principle recognizes the widespread use of IA therapies and that their use is specific to the disease that is being treated and “may not be interchangeable across indications,” Dr. Usón said. The second principle concerns improving patient-centered outcomes, which are “those that are relevant to the patient,” and include the benefits, harms, preferences, or implications for self-management.

“Contextual factors are important and contribute to the effect of IAT [intra-articular treatment],” she said, discussing the third principle. “These include effective communication, patient expectations, or settings [where the procedure takes place]. In addition, one should take into account that the route of delivery has in itself a placebo effect. We found that in different RCTs [randomized controlled trials], the pooled placebo effect of IA saline is moderate to large.”

The fourth principle looks at ensuring that patients and clinicians make an informed and shared decision, which is again highlighted by the first recommendation. The fifth, and last, overarching principle acknowledges that IA injections may be given by a range of health care professionals.

Advice for before, during, and after injection

Patients need to be “fully informed of the nature of the procedure, the injectable used, and potential effects – benefits and risks – [and] informed consent should be obtained and documented,” said Dr. Usón, outlining the first recommendation. “That seems common,” she said in the interview, “but when we did the survey, we realize that many patients didn’t [give consent], and the doctors didn’t even ask for it. This is why it’s a very general statement, and it’s our first recommendation. The agreement was 99%!”

The recommendations also look at the optimal settings for performing injections, such as providing a professional and private, well-lighted room, and having a resuscitation kit nearby in case patients faint. Accuracy is important, Dr. Usón said, and imaging, such as ultrasound, should be used where available to ensure accurate injection into the joint. This is an area where further research could be performed, she said, urging young rheumatologists and health professionals to consider this. “Intra-articular therapy is something that you learn and do, but you never really investigate in it,” she said.

One recommendation states that when intra-articular injections are being given to pregnant patients, the safety of injected compound must be considered, both for the mother and for the fetus. There is another recommendation on the need to perform IA injections under aseptic conditions, and another stating that patients should be offered local anesthetics, after explaining the pros and cons.

Special populations of patients are also considered, Dr. Usón said. For example, the guidance advises warning patients with diabetes of the risk of transient glycemia after IA glucocorticoids and the need to monitor their blood glucose levels carefully for a couple of days afterward.

As a rule, “IAT is not a contraindication to people with clotting or bleeding disorders, or taking antithrombotic medications,” she said, unless they are at a high risk of bleeding.

Importantly, the recommendations cover when IAT can be performed after joint replacement surgery (after at least 3 months), and the need to “avoid overuse of injected joints” while also avoiding complete immobilization for at least 24 hours afterward. The recommendations very generally cover re-injections, but not how long intervals between injections should be. When asked about interval duration after her presentation, Dr. Usón said that the usual advice is to give IA injections no more than 2-3 times a year, but it depends on the injectable.

“It wasn’t our intention to review the efficacy and the safety of the different injectables, nor to review the use of IAT in different types of joint diseases,” she said. “We do lack a lot of information, a lot of evidence in this, and I really would hope that new rheumatologists start looking into and start investigating in this topic,” she added.

Recommendations will increase awareness of good clinical practice

“IA injections are commonly administered in the rheumatology setting. This is because [IA injection] is often a useful treatment for acute flare of arthritis, particularly when it is limited to a few joints,” observed Ai Lyn Tan, MD, associate professor and honorary consultant rheumatologist at the Leeds (England) Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine.

IA injection “also relieves symptoms relatively quickly for patients; however, the response can be variable, and there are side effects associated with IA injections,” Dr. Tan added in an interview.

There is a lack of universally accepted recommendations, Dr. Tan observed, noting that while there might be some local guidelines on how to safely perform IA injections these were often not standardized and were subject to being continually updated to try to improve the experience for patients.

“It is therefore timely to learn about the new EULAR recommendations for IA injections. The advantage of this will be to increase awareness of good clinical practice for performing IA injections.”

Dr. Tan had no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: EULAR COVID-19 Recommendations. E-congress content available until Sept. 1, 2020.

New EULAR recommendations for the intra-articular (IA) treatment of arthropathies aim to facilitate uniformity and quality of care for this mainstay of rheumatologic practice, according to a report on the new guidance that was presented at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, held online this year due to COVID-19.

Until now there were no official recommendations on how best to use it in everyday practice. “This is the first time that there’s been a joint effort to develop evidence-based recommendations,” Jacqueline Usón, MD, PhD, associate professor medicine at Rey Juan Carlos University in Madrid, said in an interview. “Everything that we are saying is pretty logical, but it’s nice to see it put in recommendations based on evidence.”

IA therapy has been around for decades and is key for treating adults with a number of different conditions where synovitis, effusion, pain, or all three, are present, such as inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis, Dr. Usón observed during her presentation.

“Today, commonly used injectables are not only corticosteroids but also local anesthetics, hyaluronic acid, blood products, and maybe pharmaceuticals,” she said, adding that “there is a wide variation in the way intra-articular therapies are used and delivered to patients.” Health professionals also have very different views and habits depending on geographic locations and health care systems, she observed. Ironing out the variation was one of the main objectives of the recommendations.

As one of the two conveners of the EULAR task force behind the recommendations, Dr. Usón, herself a rheumatologist at University Hospital of Móstoles, pointed out that the task force brought together a range of specialties – rheumatologists, orthopedic surgeons, radiologists, nuclear medicine specialists, among others, as well as patients – to ensure that the best advice could be given.

The task force followed EULAR standard operating procedures for developing recommendations, with discussion groups, systematic literature reviews, and Delphi technique-based consensus all being employed. The literature search considered publications from 1946 up until 2019.

“We agreed on the need for more background information from health professionals and patients, so we developed two surveys: One for health professionals with 160 items, [for which] we obtained 186 responses from 26 countries; and the patient survey was made up of 44 items, translated into 10 different languages, and we obtained 200 responses,” she said.

The results of the systematic literature review and surveys were used to help form expert consensus, leading to 5 overarching principles and 11 recommendations that look at before, during, and after intra-articular therapy.

Five overarching principles

The first overarching principle recognizes the widespread use of IA therapies and that their use is specific to the disease that is being treated and “may not be interchangeable across indications,” Dr. Usón said. The second principle concerns improving patient-centered outcomes, which are “those that are relevant to the patient,” and include the benefits, harms, preferences, or implications for self-management.

“Contextual factors are important and contribute to the effect of IAT [intra-articular treatment],” she said, discussing the third principle. “These include effective communication, patient expectations, or settings [where the procedure takes place]. In addition, one should take into account that the route of delivery has in itself a placebo effect. We found that in different RCTs [randomized controlled trials], the pooled placebo effect of IA saline is moderate to large.”

The fourth principle looks at ensuring that patients and clinicians make an informed and shared decision, which is again highlighted by the first recommendation. The fifth, and last, overarching principle acknowledges that IA injections may be given by a range of health care professionals.

Advice for before, during, and after injection

Patients need to be “fully informed of the nature of the procedure, the injectable used, and potential effects – benefits and risks – [and] informed consent should be obtained and documented,” said Dr. Usón, outlining the first recommendation. “That seems common,” she said in the interview, “but when we did the survey, we realize that many patients didn’t [give consent], and the doctors didn’t even ask for it. This is why it’s a very general statement, and it’s our first recommendation. The agreement was 99%!”

The recommendations also look at the optimal settings for performing injections, such as providing a professional and private, well-lighted room, and having a resuscitation kit nearby in case patients faint. Accuracy is important, Dr. Usón said, and imaging, such as ultrasound, should be used where available to ensure accurate injection into the joint. This is an area where further research could be performed, she said, urging young rheumatologists and health professionals to consider this. “Intra-articular therapy is something that you learn and do, but you never really investigate in it,” she said.

One recommendation states that when intra-articular injections are being given to pregnant patients, the safety of injected compound must be considered, both for the mother and for the fetus. There is another recommendation on the need to perform IA injections under aseptic conditions, and another stating that patients should be offered local anesthetics, after explaining the pros and cons.

Special populations of patients are also considered, Dr. Usón said. For example, the guidance advises warning patients with diabetes of the risk of transient glycemia after IA glucocorticoids and the need to monitor their blood glucose levels carefully for a couple of days afterward.

As a rule, “IAT is not a contraindication to people with clotting or bleeding disorders, or taking antithrombotic medications,” she said, unless they are at a high risk of bleeding.

Importantly, the recommendations cover when IAT can be performed after joint replacement surgery (after at least 3 months), and the need to “avoid overuse of injected joints” while also avoiding complete immobilization for at least 24 hours afterward. The recommendations very generally cover re-injections, but not how long intervals between injections should be. When asked about interval duration after her presentation, Dr. Usón said that the usual advice is to give IA injections no more than 2-3 times a year, but it depends on the injectable.

“It wasn’t our intention to review the efficacy and the safety of the different injectables, nor to review the use of IAT in different types of joint diseases,” she said. “We do lack a lot of information, a lot of evidence in this, and I really would hope that new rheumatologists start looking into and start investigating in this topic,” she added.

Recommendations will increase awareness of good clinical practice

“IA injections are commonly administered in the rheumatology setting. This is because [IA injection] is often a useful treatment for acute flare of arthritis, particularly when it is limited to a few joints,” observed Ai Lyn Tan, MD, associate professor and honorary consultant rheumatologist at the Leeds (England) Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine.

IA injection “also relieves symptoms relatively quickly for patients; however, the response can be variable, and there are side effects associated with IA injections,” Dr. Tan added in an interview.

There is a lack of universally accepted recommendations, Dr. Tan observed, noting that while there might be some local guidelines on how to safely perform IA injections these were often not standardized and were subject to being continually updated to try to improve the experience for patients.