User login

Functional MRI shows that empathetic remarks reduce pain

These are the results of a study, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that was conducted by a team led by neuroscientist Dan-Mikael Ellingsen, PhD, from Oslo University Hospital.

The researchers used functional MRI to scan the brains of 20 patients with chronic pain to investigate how a physician’s demeanor may affect patients’ sensitivity to pain, including effects in the central nervous system. During the scans, which were conducted in two sessions, the patients’ legs were exposed to stimuli that ranged from painless to moderately painful. The patients recorded perceived pain intensity using a scale. The physicians also underwent fMRI.

Half of the patients were subjected to the pain stimuli while alone; the other half were subjected to pain while in the presence of a physician. The latter group of patients was divided into two subgroups. Half of the patients had spoken to the accompanying physician before the examination. They discussed the history of the patient’s condition to date, among other things. The other half underwent the brain scans without any prior interaction with a physician.

Worse when alone

Dr. Ellingsen and his colleagues found that patients who were alone during the examination reported greater pain than those who were in the presence of a physician, even though they were subjected to stimuli of the same intensity. In instances in which the physician and patient had already spoken before the brain scan, patients additionally felt that the physician was empathetic and understood their pain. Furthermore, the physicians were better able to estimate the pain that their patients experienced.

The patients who had a physician by their side consistently experienced pain that was milder than the pain experienced by those who were alone. For pairs that had spoken beforehand, the patients considered their physician to be better able to understand their pain, and the physicians estimated the perceived pain intensity of their patients more accurately.

Evidence of trust

There was greater activity in the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, as well as in the primary and secondary somatosensory areas, in patients in the subgroup that had spoken to a physician. For the physicians, compared with the comparison group, there was an increase in correspondence between activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and activity in the secondary somatosensory areas of patients, which is a brain region that is known to react to pain. The brain activity correlation increased in line with the self-reported mutual trust between the physician and patient.

“These results prove that empathy and support can decrease pain intensity,” the investigators write. The data shed light on the brain processes behind the social modulation of pain during the interaction between the physician and the patient. Concordances in the brain are increased by greater therapeutic alliance.

Beyond medication

Winfried Meissner, MD, head of the pain clinic at the department of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine at Jena University Hospital, Germany, and former president of the German Pain Society, said in an interview: “I view this as a vital study that impressively demonstrates that effective, intensive pain therapy is not just a case of administering the correct analgesic.”

“Instead, a focus should be placed on what common sense tells us, which is just how crucial an empathetic attitude from physicians and good communication with patients are when it comes to the success of any therapy,” Dr. Meissner added. Unfortunately, such an attitude and such communication often are not provided in clinical practice because of limitations on time.

“Now, with objectively collected data from patients and physicians, [Dr.] Ellingsen’s team has been able to demonstrate that human interaction has a decisive impact on the treatment of patients experiencing pain,” said Dr. Meissner. “The study should encourage practitioners to treat communication just as seriously as the pharmacology of analgesics.”

Perception and attitude

“The study shows remarkably well that empathetic conversation between the physician and patient represents a valuable therapeutic method and should be recognized as such,” emphasized Dr. Meissner. Of course, conversation cannot replace pharmacologic treatment, but it can supplement and reinforce it. Furthermore, a physician’s empathy presumably has an effect that is at least as great as a suitable analgesic.

“Pain is more than just sensory perception,” explained Dr. Meissner. “We all know that it has a strong affective component, and perception is greatly determined by context.” This can be seen, for example, in athletes, who often attribute less importance to their pain and can successfully perform competitively despite a painful injury.

Positive expectations

Dr. Meissner advised all physicians to treat patients with pain empathetically. He encourages them to ask patients about their pain, accompanying symptoms, possible fears, and other mental stress and to take these factors seriously.

Moreover, the findings accentuate the effect of prescribed analgesics. “Numerous studies have meanwhile shown that the more positive a patient’s expectations, the better the effect of a medication,” said Dr. Meissner. “We physicians must exploit this effect, too.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

These are the results of a study, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that was conducted by a team led by neuroscientist Dan-Mikael Ellingsen, PhD, from Oslo University Hospital.

The researchers used functional MRI to scan the brains of 20 patients with chronic pain to investigate how a physician’s demeanor may affect patients’ sensitivity to pain, including effects in the central nervous system. During the scans, which were conducted in two sessions, the patients’ legs were exposed to stimuli that ranged from painless to moderately painful. The patients recorded perceived pain intensity using a scale. The physicians also underwent fMRI.

Half of the patients were subjected to the pain stimuli while alone; the other half were subjected to pain while in the presence of a physician. The latter group of patients was divided into two subgroups. Half of the patients had spoken to the accompanying physician before the examination. They discussed the history of the patient’s condition to date, among other things. The other half underwent the brain scans without any prior interaction with a physician.

Worse when alone

Dr. Ellingsen and his colleagues found that patients who were alone during the examination reported greater pain than those who were in the presence of a physician, even though they were subjected to stimuli of the same intensity. In instances in which the physician and patient had already spoken before the brain scan, patients additionally felt that the physician was empathetic and understood their pain. Furthermore, the physicians were better able to estimate the pain that their patients experienced.

The patients who had a physician by their side consistently experienced pain that was milder than the pain experienced by those who were alone. For pairs that had spoken beforehand, the patients considered their physician to be better able to understand their pain, and the physicians estimated the perceived pain intensity of their patients more accurately.

Evidence of trust

There was greater activity in the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, as well as in the primary and secondary somatosensory areas, in patients in the subgroup that had spoken to a physician. For the physicians, compared with the comparison group, there was an increase in correspondence between activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and activity in the secondary somatosensory areas of patients, which is a brain region that is known to react to pain. The brain activity correlation increased in line with the self-reported mutual trust between the physician and patient.

“These results prove that empathy and support can decrease pain intensity,” the investigators write. The data shed light on the brain processes behind the social modulation of pain during the interaction between the physician and the patient. Concordances in the brain are increased by greater therapeutic alliance.

Beyond medication

Winfried Meissner, MD, head of the pain clinic at the department of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine at Jena University Hospital, Germany, and former president of the German Pain Society, said in an interview: “I view this as a vital study that impressively demonstrates that effective, intensive pain therapy is not just a case of administering the correct analgesic.”

“Instead, a focus should be placed on what common sense tells us, which is just how crucial an empathetic attitude from physicians and good communication with patients are when it comes to the success of any therapy,” Dr. Meissner added. Unfortunately, such an attitude and such communication often are not provided in clinical practice because of limitations on time.

“Now, with objectively collected data from patients and physicians, [Dr.] Ellingsen’s team has been able to demonstrate that human interaction has a decisive impact on the treatment of patients experiencing pain,” said Dr. Meissner. “The study should encourage practitioners to treat communication just as seriously as the pharmacology of analgesics.”

Perception and attitude

“The study shows remarkably well that empathetic conversation between the physician and patient represents a valuable therapeutic method and should be recognized as such,” emphasized Dr. Meissner. Of course, conversation cannot replace pharmacologic treatment, but it can supplement and reinforce it. Furthermore, a physician’s empathy presumably has an effect that is at least as great as a suitable analgesic.

“Pain is more than just sensory perception,” explained Dr. Meissner. “We all know that it has a strong affective component, and perception is greatly determined by context.” This can be seen, for example, in athletes, who often attribute less importance to their pain and can successfully perform competitively despite a painful injury.

Positive expectations

Dr. Meissner advised all physicians to treat patients with pain empathetically. He encourages them to ask patients about their pain, accompanying symptoms, possible fears, and other mental stress and to take these factors seriously.

Moreover, the findings accentuate the effect of prescribed analgesics. “Numerous studies have meanwhile shown that the more positive a patient’s expectations, the better the effect of a medication,” said Dr. Meissner. “We physicians must exploit this effect, too.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

These are the results of a study, recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that was conducted by a team led by neuroscientist Dan-Mikael Ellingsen, PhD, from Oslo University Hospital.

The researchers used functional MRI to scan the brains of 20 patients with chronic pain to investigate how a physician’s demeanor may affect patients’ sensitivity to pain, including effects in the central nervous system. During the scans, which were conducted in two sessions, the patients’ legs were exposed to stimuli that ranged from painless to moderately painful. The patients recorded perceived pain intensity using a scale. The physicians also underwent fMRI.

Half of the patients were subjected to the pain stimuli while alone; the other half were subjected to pain while in the presence of a physician. The latter group of patients was divided into two subgroups. Half of the patients had spoken to the accompanying physician before the examination. They discussed the history of the patient’s condition to date, among other things. The other half underwent the brain scans without any prior interaction with a physician.

Worse when alone

Dr. Ellingsen and his colleagues found that patients who were alone during the examination reported greater pain than those who were in the presence of a physician, even though they were subjected to stimuli of the same intensity. In instances in which the physician and patient had already spoken before the brain scan, patients additionally felt that the physician was empathetic and understood their pain. Furthermore, the physicians were better able to estimate the pain that their patients experienced.

The patients who had a physician by their side consistently experienced pain that was milder than the pain experienced by those who were alone. For pairs that had spoken beforehand, the patients considered their physician to be better able to understand their pain, and the physicians estimated the perceived pain intensity of their patients more accurately.

Evidence of trust

There was greater activity in the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, as well as in the primary and secondary somatosensory areas, in patients in the subgroup that had spoken to a physician. For the physicians, compared with the comparison group, there was an increase in correspondence between activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and activity in the secondary somatosensory areas of patients, which is a brain region that is known to react to pain. The brain activity correlation increased in line with the self-reported mutual trust between the physician and patient.

“These results prove that empathy and support can decrease pain intensity,” the investigators write. The data shed light on the brain processes behind the social modulation of pain during the interaction between the physician and the patient. Concordances in the brain are increased by greater therapeutic alliance.

Beyond medication

Winfried Meissner, MD, head of the pain clinic at the department of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine at Jena University Hospital, Germany, and former president of the German Pain Society, said in an interview: “I view this as a vital study that impressively demonstrates that effective, intensive pain therapy is not just a case of administering the correct analgesic.”

“Instead, a focus should be placed on what common sense tells us, which is just how crucial an empathetic attitude from physicians and good communication with patients are when it comes to the success of any therapy,” Dr. Meissner added. Unfortunately, such an attitude and such communication often are not provided in clinical practice because of limitations on time.

“Now, with objectively collected data from patients and physicians, [Dr.] Ellingsen’s team has been able to demonstrate that human interaction has a decisive impact on the treatment of patients experiencing pain,” said Dr. Meissner. “The study should encourage practitioners to treat communication just as seriously as the pharmacology of analgesics.”

Perception and attitude

“The study shows remarkably well that empathetic conversation between the physician and patient represents a valuable therapeutic method and should be recognized as such,” emphasized Dr. Meissner. Of course, conversation cannot replace pharmacologic treatment, but it can supplement and reinforce it. Furthermore, a physician’s empathy presumably has an effect that is at least as great as a suitable analgesic.

“Pain is more than just sensory perception,” explained Dr. Meissner. “We all know that it has a strong affective component, and perception is greatly determined by context.” This can be seen, for example, in athletes, who often attribute less importance to their pain and can successfully perform competitively despite a painful injury.

Positive expectations

Dr. Meissner advised all physicians to treat patients with pain empathetically. He encourages them to ask patients about their pain, accompanying symptoms, possible fears, and other mental stress and to take these factors seriously.

Moreover, the findings accentuate the effect of prescribed analgesics. “Numerous studies have meanwhile shown that the more positive a patient’s expectations, the better the effect of a medication,” said Dr. Meissner. “We physicians must exploit this effect, too.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German Edition and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES

Opioid initiation in dementia tied to an 11-fold increased risk of death

Opioid initiation for older adults with dementia is linked to a significantly increased risk of death, especially in the first 2 weeks, when the risk is elevated 11-fold, new research shows.

“We expected that opioids would be associated with an increased risk of death, but we are surprised by the magnitude,” study investigator Christina Jensen-Dahm, MD, PhD, with the Danish Dementia Research Centre, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Denmark, told this news organization.

“It’s important that physicians carefully evaluate the risk and benefits if considering initiating an opioid, and this is particularly important in elderly with dementia,” Dr. Jensen-Dahm added.

The findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Risky business

Using Danish nationwide registries, the researchers analyzed data on all 75,471 adults in Denmark who were aged 65 and older and had been diagnosed with dementia between 2008 and 2018. A total of 31,619 individuals (42%) filled a prescription for an opioid. These “exposed” individuals were matched to 63,235 unexposed individuals.

Among the exposed group, 10,474 (33%) died within 180 days after starting opioid therapy, compared with 3,980 (6.4%) in the unexposed group.

After adjusting for potential differences between groups, new use of an opioid was associated with a greater than fourfold excess mortality risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.16; 95% confidence interval, 4.00-4.33).

New use of a strong opioid – defined as morphine, oxycodone, ketobemidone, hydromorphone, pethidine, buprenorphine, and fentanyl – was associated with a greater than sixfold increase in mortality risk (aHR, 6.42; 95% CI, 6.08-6.79).

Among those who used fentanyl patches as their first opioid, 65% died within the first 180 days, compared with 6.7% in the unexposed – an eightfold increased mortality risk (aHR, 8.04; 95% CI, 7.01-9.22).

For all opioids, the risk was greatest in the first 14 days, with a nearly 11-fold increased risk of mortality (aHR, 10.8; 95% CI, 9.74-11.99). However, there remained a twofold increase in risk after taking opioids for 90 days (aHR, 2.32; 95% CI, 2.17-2.48).

“Opioids are associated with severe and well-known side effects, such as sedation, confusion, respiratory depression, falls, and in the most severe cases, death. In the general population, opioids have been associated with an increased risk of death, and similar to ours, greatest in the first 14 days,” said Dr. Jensen-Dahm.

Need to weigh risks, benefits

Commenting on the study, Percy Griffin, PhD, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, told this news organization that the use of strong opioids has “increased considerably over the past decade among older people with dementia. Opioid therapy should only be considered for pain if the benefits are anticipated to outweigh the risks in individuals who are living with dementia.”

“Opioids are very powerful drugs, and while we need to see additional research in more diverse populations, these initial findings indicate they may put older adults with dementia at much higher risk of death,” Nicole Purcell, DO, neurologist and senior director of clinical practice at the Alzheimer’s Association, added in a conference statement.

“Pain should not go undiagnosed or untreated, in particular in people living with dementia, who may not be able to effectively articulate the location and severity of the pain,” Dr. Purcell added.

These new findings further emphasize the need for discussion between patient, family, and physician. Decisions about prescribing pain medication should be thought through carefully, and if used, there needs to be careful monitoring of the patient, said Dr. Purcell.

The study was supported by a grant from the Capital Region of Denmark. Dr. Jensen-Dahm, Dr. Griffin, and Dr. Purcell have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid initiation for older adults with dementia is linked to a significantly increased risk of death, especially in the first 2 weeks, when the risk is elevated 11-fold, new research shows.

“We expected that opioids would be associated with an increased risk of death, but we are surprised by the magnitude,” study investigator Christina Jensen-Dahm, MD, PhD, with the Danish Dementia Research Centre, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Denmark, told this news organization.

“It’s important that physicians carefully evaluate the risk and benefits if considering initiating an opioid, and this is particularly important in elderly with dementia,” Dr. Jensen-Dahm added.

The findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Risky business

Using Danish nationwide registries, the researchers analyzed data on all 75,471 adults in Denmark who were aged 65 and older and had been diagnosed with dementia between 2008 and 2018. A total of 31,619 individuals (42%) filled a prescription for an opioid. These “exposed” individuals were matched to 63,235 unexposed individuals.

Among the exposed group, 10,474 (33%) died within 180 days after starting opioid therapy, compared with 3,980 (6.4%) in the unexposed group.

After adjusting for potential differences between groups, new use of an opioid was associated with a greater than fourfold excess mortality risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.16; 95% confidence interval, 4.00-4.33).

New use of a strong opioid – defined as morphine, oxycodone, ketobemidone, hydromorphone, pethidine, buprenorphine, and fentanyl – was associated with a greater than sixfold increase in mortality risk (aHR, 6.42; 95% CI, 6.08-6.79).

Among those who used fentanyl patches as their first opioid, 65% died within the first 180 days, compared with 6.7% in the unexposed – an eightfold increased mortality risk (aHR, 8.04; 95% CI, 7.01-9.22).

For all opioids, the risk was greatest in the first 14 days, with a nearly 11-fold increased risk of mortality (aHR, 10.8; 95% CI, 9.74-11.99). However, there remained a twofold increase in risk after taking opioids for 90 days (aHR, 2.32; 95% CI, 2.17-2.48).

“Opioids are associated with severe and well-known side effects, such as sedation, confusion, respiratory depression, falls, and in the most severe cases, death. In the general population, opioids have been associated with an increased risk of death, and similar to ours, greatest in the first 14 days,” said Dr. Jensen-Dahm.

Need to weigh risks, benefits

Commenting on the study, Percy Griffin, PhD, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, told this news organization that the use of strong opioids has “increased considerably over the past decade among older people with dementia. Opioid therapy should only be considered for pain if the benefits are anticipated to outweigh the risks in individuals who are living with dementia.”

“Opioids are very powerful drugs, and while we need to see additional research in more diverse populations, these initial findings indicate they may put older adults with dementia at much higher risk of death,” Nicole Purcell, DO, neurologist and senior director of clinical practice at the Alzheimer’s Association, added in a conference statement.

“Pain should not go undiagnosed or untreated, in particular in people living with dementia, who may not be able to effectively articulate the location and severity of the pain,” Dr. Purcell added.

These new findings further emphasize the need for discussion between patient, family, and physician. Decisions about prescribing pain medication should be thought through carefully, and if used, there needs to be careful monitoring of the patient, said Dr. Purcell.

The study was supported by a grant from the Capital Region of Denmark. Dr. Jensen-Dahm, Dr. Griffin, and Dr. Purcell have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioid initiation for older adults with dementia is linked to a significantly increased risk of death, especially in the first 2 weeks, when the risk is elevated 11-fold, new research shows.

“We expected that opioids would be associated with an increased risk of death, but we are surprised by the magnitude,” study investigator Christina Jensen-Dahm, MD, PhD, with the Danish Dementia Research Centre, Copenhagen University Hospital, Rigshospitalet, Denmark, told this news organization.

“It’s important that physicians carefully evaluate the risk and benefits if considering initiating an opioid, and this is particularly important in elderly with dementia,” Dr. Jensen-Dahm added.

The findings were presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Risky business

Using Danish nationwide registries, the researchers analyzed data on all 75,471 adults in Denmark who were aged 65 and older and had been diagnosed with dementia between 2008 and 2018. A total of 31,619 individuals (42%) filled a prescription for an opioid. These “exposed” individuals were matched to 63,235 unexposed individuals.

Among the exposed group, 10,474 (33%) died within 180 days after starting opioid therapy, compared with 3,980 (6.4%) in the unexposed group.

After adjusting for potential differences between groups, new use of an opioid was associated with a greater than fourfold excess mortality risk (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.16; 95% confidence interval, 4.00-4.33).

New use of a strong opioid – defined as morphine, oxycodone, ketobemidone, hydromorphone, pethidine, buprenorphine, and fentanyl – was associated with a greater than sixfold increase in mortality risk (aHR, 6.42; 95% CI, 6.08-6.79).

Among those who used fentanyl patches as their first opioid, 65% died within the first 180 days, compared with 6.7% in the unexposed – an eightfold increased mortality risk (aHR, 8.04; 95% CI, 7.01-9.22).

For all opioids, the risk was greatest in the first 14 days, with a nearly 11-fold increased risk of mortality (aHR, 10.8; 95% CI, 9.74-11.99). However, there remained a twofold increase in risk after taking opioids for 90 days (aHR, 2.32; 95% CI, 2.17-2.48).

“Opioids are associated with severe and well-known side effects, such as sedation, confusion, respiratory depression, falls, and in the most severe cases, death. In the general population, opioids have been associated with an increased risk of death, and similar to ours, greatest in the first 14 days,” said Dr. Jensen-Dahm.

Need to weigh risks, benefits

Commenting on the study, Percy Griffin, PhD, director of scientific engagement at the Alzheimer’s Association, told this news organization that the use of strong opioids has “increased considerably over the past decade among older people with dementia. Opioid therapy should only be considered for pain if the benefits are anticipated to outweigh the risks in individuals who are living with dementia.”

“Opioids are very powerful drugs, and while we need to see additional research in more diverse populations, these initial findings indicate they may put older adults with dementia at much higher risk of death,” Nicole Purcell, DO, neurologist and senior director of clinical practice at the Alzheimer’s Association, added in a conference statement.

“Pain should not go undiagnosed or untreated, in particular in people living with dementia, who may not be able to effectively articulate the location and severity of the pain,” Dr. Purcell added.

These new findings further emphasize the need for discussion between patient, family, and physician. Decisions about prescribing pain medication should be thought through carefully, and if used, there needs to be careful monitoring of the patient, said Dr. Purcell.

The study was supported by a grant from the Capital Region of Denmark. Dr. Jensen-Dahm, Dr. Griffin, and Dr. Purcell have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

From AAIC 2023

Fibromyalgia linked to higher mortality risk

People who experience chronic pain and tiredness from fibromyalgia have an increased risk for all-cause mortality, a new analysis of evidence says.

The condition can lead people to be vulnerable to accidents, infections, and even suicide, according to the report published in RMD Open.

The researchers suggest that care providers monitor physical and mental health to lower the dangers.

People with fibromyalgia often have other health issues, including rheumatic, gut, neurological, and mental health disorders, according to The BMJ. More and more people are being diagnosed with fibromyalgia. The cause of the illness remains unclear.

The researchers looked at eight studies published between 1999 and 2020 and pooled results from six of them. The studies involved a total of 188,000 adults.

The analysis of the data revealed that fibromyalgia was linked to a 27% greater risk of death from all causes.

Those with fibromyalgia were at a 44% greater risk of infections, including pneumonia. Their suicide risk was more than three times higher.

The greater risk of all-cause death could result from fatigue, poor sleep, and concentration problems, The BMJ said.

The patients had a 12% lower risk of dying from cancer, the analysis found. This could be because they tend to make more visits to health care professionals, the authors suggest.

“Fibromyalgia is often called an ‘imaginary condition,’ with ongoing debates on the legitimacy and clinical usefulness of this diagnosis. Our review provides further proof that fibromyalgia patients should be taken seriously, with particular focus on screening for suicidal ideation, prevention of accidents, and prevention and treatment of infections,” the researchers say.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

People who experience chronic pain and tiredness from fibromyalgia have an increased risk for all-cause mortality, a new analysis of evidence says.

The condition can lead people to be vulnerable to accidents, infections, and even suicide, according to the report published in RMD Open.

The researchers suggest that care providers monitor physical and mental health to lower the dangers.

People with fibromyalgia often have other health issues, including rheumatic, gut, neurological, and mental health disorders, according to The BMJ. More and more people are being diagnosed with fibromyalgia. The cause of the illness remains unclear.

The researchers looked at eight studies published between 1999 and 2020 and pooled results from six of them. The studies involved a total of 188,000 adults.

The analysis of the data revealed that fibromyalgia was linked to a 27% greater risk of death from all causes.

Those with fibromyalgia were at a 44% greater risk of infections, including pneumonia. Their suicide risk was more than three times higher.

The greater risk of all-cause death could result from fatigue, poor sleep, and concentration problems, The BMJ said.

The patients had a 12% lower risk of dying from cancer, the analysis found. This could be because they tend to make more visits to health care professionals, the authors suggest.

“Fibromyalgia is often called an ‘imaginary condition,’ with ongoing debates on the legitimacy and clinical usefulness of this diagnosis. Our review provides further proof that fibromyalgia patients should be taken seriously, with particular focus on screening for suicidal ideation, prevention of accidents, and prevention and treatment of infections,” the researchers say.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

People who experience chronic pain and tiredness from fibromyalgia have an increased risk for all-cause mortality, a new analysis of evidence says.

The condition can lead people to be vulnerable to accidents, infections, and even suicide, according to the report published in RMD Open.

The researchers suggest that care providers monitor physical and mental health to lower the dangers.

People with fibromyalgia often have other health issues, including rheumatic, gut, neurological, and mental health disorders, according to The BMJ. More and more people are being diagnosed with fibromyalgia. The cause of the illness remains unclear.

The researchers looked at eight studies published between 1999 and 2020 and pooled results from six of them. The studies involved a total of 188,000 adults.

The analysis of the data revealed that fibromyalgia was linked to a 27% greater risk of death from all causes.

Those with fibromyalgia were at a 44% greater risk of infections, including pneumonia. Their suicide risk was more than three times higher.

The greater risk of all-cause death could result from fatigue, poor sleep, and concentration problems, The BMJ said.

The patients had a 12% lower risk of dying from cancer, the analysis found. This could be because they tend to make more visits to health care professionals, the authors suggest.

“Fibromyalgia is often called an ‘imaginary condition,’ with ongoing debates on the legitimacy and clinical usefulness of this diagnosis. Our review provides further proof that fibromyalgia patients should be taken seriously, with particular focus on screening for suicidal ideation, prevention of accidents, and prevention and treatment of infections,” the researchers say.

A version of this article appeared on WebMD.com.

Medical cannabis does not reduce use of prescription meds

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cannabis advocates suggest that legal medical cannabis can be a partial solution to the opioid overdose crisis in the United States, which claimed more than 80,000 lives in 2021.

- Current research on how legalized cannabis reduces dependence on prescription pain medication is inconclusive.

- Researchers examined insurance data for the period 2010-2022 from 583,820 adults with chronic noncancer pain.

- They drew from 12 states in which medical cannabis is legal and from 17 in which it is not legal to create a hypothetical randomized trial. The control group simulated prescription rates where medical cannabis was not available.

- Authors evaluated prescription rates for opioids, nonopioid painkillers, and pain interventions, such as physical therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

In a given month during the first 3 years after legalization, for states with medical cannabis, the investigators found the following:

- There was an average decrease of 1.07 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any opioid prescription, compared to a 1.12 percentage point decrease in the control group.

- There was an average increase of 1.14 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any nonopioid prescription painkiller, compared to a 1.19 percentage point increase in the control group.

- There was a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the proportion of patients who received any pain procedure, compared to a 0.001 percentage point decrease in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study did not identify important effects of medical cannabis laws on receipt of opioid or nonopioid pain treatment among patients with chronic noncancer pain,” according to the researchers.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Emma E. McGinty, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators used a simulated, hypothetical control group that was based on untestable assumptions. They also drew data solely from insured individuals, so the study does not necessarily represent uninsured populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. McGinty reports receiving a grant from NIDA. Her coauthors reported receiving support from NIDA and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cannabis advocates suggest that legal medical cannabis can be a partial solution to the opioid overdose crisis in the United States, which claimed more than 80,000 lives in 2021.

- Current research on how legalized cannabis reduces dependence on prescription pain medication is inconclusive.

- Researchers examined insurance data for the period 2010-2022 from 583,820 adults with chronic noncancer pain.

- They drew from 12 states in which medical cannabis is legal and from 17 in which it is not legal to create a hypothetical randomized trial. The control group simulated prescription rates where medical cannabis was not available.

- Authors evaluated prescription rates for opioids, nonopioid painkillers, and pain interventions, such as physical therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

In a given month during the first 3 years after legalization, for states with medical cannabis, the investigators found the following:

- There was an average decrease of 1.07 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any opioid prescription, compared to a 1.12 percentage point decrease in the control group.

- There was an average increase of 1.14 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any nonopioid prescription painkiller, compared to a 1.19 percentage point increase in the control group.

- There was a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the proportion of patients who received any pain procedure, compared to a 0.001 percentage point decrease in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study did not identify important effects of medical cannabis laws on receipt of opioid or nonopioid pain treatment among patients with chronic noncancer pain,” according to the researchers.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Emma E. McGinty, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators used a simulated, hypothetical control group that was based on untestable assumptions. They also drew data solely from insured individuals, so the study does not necessarily represent uninsured populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. McGinty reports receiving a grant from NIDA. Her coauthors reported receiving support from NIDA and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, according to a new study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

METHODOLOGY:

- Cannabis advocates suggest that legal medical cannabis can be a partial solution to the opioid overdose crisis in the United States, which claimed more than 80,000 lives in 2021.

- Current research on how legalized cannabis reduces dependence on prescription pain medication is inconclusive.

- Researchers examined insurance data for the period 2010-2022 from 583,820 adults with chronic noncancer pain.

- They drew from 12 states in which medical cannabis is legal and from 17 in which it is not legal to create a hypothetical randomized trial. The control group simulated prescription rates where medical cannabis was not available.

- Authors evaluated prescription rates for opioids, nonopioid painkillers, and pain interventions, such as physical therapy.

TAKEAWAY:

In a given month during the first 3 years after legalization, for states with medical cannabis, the investigators found the following:

- There was an average decrease of 1.07 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any opioid prescription, compared to a 1.12 percentage point decrease in the control group.

- There was an average increase of 1.14 percentage points in the proportion of patients who received any nonopioid prescription painkiller, compared to a 1.19 percentage point increase in the control group.

- There was a 0.17 percentage point decrease in the proportion of patients who received any pain procedure, compared to a 0.001 percentage point decrease in the control group.

IN PRACTICE:

“This study did not identify important effects of medical cannabis laws on receipt of opioid or nonopioid pain treatment among patients with chronic noncancer pain,” according to the researchers.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Emma E. McGinty, PhD, of Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, and was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

LIMITATIONS:

The investigators used a simulated, hypothetical control group that was based on untestable assumptions. They also drew data solely from insured individuals, so the study does not necessarily represent uninsured populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. McGinty reports receiving a grant from NIDA. Her coauthors reported receiving support from NIDA and the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Landmark’ trial shows opioids for back, neck pain no better than placebo

Opioids do not relieve acute low back or neck pain in the short term and lead to worse outcomes in the long term, results of the first randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy and safety of a short course of opioids for acute nonspecific low back/neck pain suggest.

After 6 weeks, there was no significant difference in pain scores of patients who took opioids, compared with those who took placebo. After 1 year, patients given the placebo had slightly lower pain scores. Also, patients using opioids were at greater risk of opioid misuse after 1 year.

This is a “landmark” trial with “practice-changing” results, senior author Christine Lin, PhD, with the University of Sydney, told this news organization.

“Before this trial, we did not have good evidence on whether opioids were effective for acute low back pain or neck pain, yet opioids were one of the most commonly used medicines for these conditions,” Dr. Lin explained.

On the basis of these results, “opioids should not be recommended at all for acute low back pain and neck pain,” Dr. Lin said.

Results of the OPAL study were published online in The Lancet.

Rigorous trial

The trial was conducted in 157 primary care or emergency department sites in Australia and involved 347 adults who had been experiencing low back pain, neck pain, or both for 12 weeks or less.

They were randomly allocated (1:1) to receive guideline-recommended care (reassurance and advice to stay active) plus an opioid (oxycodone up to 20 mg daily) or identical placebo for up to 6 weeks. Naloxone was provided to help prevent opioid-induced constipation and improve blinding.

The primary outcome was pain severity at 6 weeks, measured with the pain severity subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory (10-point scale).

After 6 weeks, opioid therapy offered no more relief for acute back/neck pain or functional improvement than placebo.

The mean pain score at 6 weeks was 2.78 in the opioid group, versus 2.25 in the placebo group (adjusted mean difference, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, –0.00 to 1.07; P = .051). At 1 year, mean pain scores in the placebo group were slightly lower than in the opioid group (1.8 vs. 2.4).

In addition, there was a doubling of the risk of opioid misuse at 1 year among patients randomly allocated to receive opioid therapy for 6 weeks, compared with those allocated to receive placebo for 6 weeks.

At 1 year, 24 (20%) of 123 of the patients who received opioids were at risk of misuse, as indicated by the Current Opioid Misuse Measure scale, compared with 13 (10%) of 128 patients in the placebo group (P = .049). The COMM is a widely used measure of current aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain who are being prescribed opioid therapy.

Results raise ‘serious questions’

“I believe the findings of the study will need to be disseminated to the doctors and patients, so they receive this latest evidence on opioids,” Dr. Lin said in an interview.

“We need to reassure doctors and patients that most people with acute low back pain and neck pain recover well with time (usually by 6 weeks), so management is simple – staying active, avoiding bed rest, and, if necessary, using a heat pack for short term pain relief. If drugs are required, consider anti-inflammatory drugs,” Dr. Lin added.

The authors of a linked comment say the OPAL trial “raises serious questions about the use of opioid therapy for acute low back and neck pain.”

Mark Sullivan, MD, PhD, and Jane Ballantyne, MD, with the University of Washington, Seattle, note that current clinical guidelines recommend opioids for patients with acute back and neck pain when other drug treatments fail or are contraindicated.

“As many as two-thirds of patients might receive an opioid when presenting for care of back or neck pain. It is time to re-examine these guidelines and these practices,” Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Ballantyne conclude.

Funding for the OPAL study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine and Health, and SafeWork SA. The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Ballantyne are board members (unpaid) of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing and have been paid consultants in opioid litigation.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids do not relieve acute low back or neck pain in the short term and lead to worse outcomes in the long term, results of the first randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy and safety of a short course of opioids for acute nonspecific low back/neck pain suggest.

After 6 weeks, there was no significant difference in pain scores of patients who took opioids, compared with those who took placebo. After 1 year, patients given the placebo had slightly lower pain scores. Also, patients using opioids were at greater risk of opioid misuse after 1 year.

This is a “landmark” trial with “practice-changing” results, senior author Christine Lin, PhD, with the University of Sydney, told this news organization.

“Before this trial, we did not have good evidence on whether opioids were effective for acute low back pain or neck pain, yet opioids were one of the most commonly used medicines for these conditions,” Dr. Lin explained.

On the basis of these results, “opioids should not be recommended at all for acute low back pain and neck pain,” Dr. Lin said.

Results of the OPAL study were published online in The Lancet.

Rigorous trial

The trial was conducted in 157 primary care or emergency department sites in Australia and involved 347 adults who had been experiencing low back pain, neck pain, or both for 12 weeks or less.

They were randomly allocated (1:1) to receive guideline-recommended care (reassurance and advice to stay active) plus an opioid (oxycodone up to 20 mg daily) or identical placebo for up to 6 weeks. Naloxone was provided to help prevent opioid-induced constipation and improve blinding.

The primary outcome was pain severity at 6 weeks, measured with the pain severity subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory (10-point scale).

After 6 weeks, opioid therapy offered no more relief for acute back/neck pain or functional improvement than placebo.

The mean pain score at 6 weeks was 2.78 in the opioid group, versus 2.25 in the placebo group (adjusted mean difference, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, –0.00 to 1.07; P = .051). At 1 year, mean pain scores in the placebo group were slightly lower than in the opioid group (1.8 vs. 2.4).

In addition, there was a doubling of the risk of opioid misuse at 1 year among patients randomly allocated to receive opioid therapy for 6 weeks, compared with those allocated to receive placebo for 6 weeks.

At 1 year, 24 (20%) of 123 of the patients who received opioids were at risk of misuse, as indicated by the Current Opioid Misuse Measure scale, compared with 13 (10%) of 128 patients in the placebo group (P = .049). The COMM is a widely used measure of current aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain who are being prescribed opioid therapy.

Results raise ‘serious questions’

“I believe the findings of the study will need to be disseminated to the doctors and patients, so they receive this latest evidence on opioids,” Dr. Lin said in an interview.

“We need to reassure doctors and patients that most people with acute low back pain and neck pain recover well with time (usually by 6 weeks), so management is simple – staying active, avoiding bed rest, and, if necessary, using a heat pack for short term pain relief. If drugs are required, consider anti-inflammatory drugs,” Dr. Lin added.

The authors of a linked comment say the OPAL trial “raises serious questions about the use of opioid therapy for acute low back and neck pain.”

Mark Sullivan, MD, PhD, and Jane Ballantyne, MD, with the University of Washington, Seattle, note that current clinical guidelines recommend opioids for patients with acute back and neck pain when other drug treatments fail or are contraindicated.

“As many as two-thirds of patients might receive an opioid when presenting for care of back or neck pain. It is time to re-examine these guidelines and these practices,” Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Ballantyne conclude.

Funding for the OPAL study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine and Health, and SafeWork SA. The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Ballantyne are board members (unpaid) of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing and have been paid consultants in opioid litigation.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Opioids do not relieve acute low back or neck pain in the short term and lead to worse outcomes in the long term, results of the first randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy and safety of a short course of opioids for acute nonspecific low back/neck pain suggest.

After 6 weeks, there was no significant difference in pain scores of patients who took opioids, compared with those who took placebo. After 1 year, patients given the placebo had slightly lower pain scores. Also, patients using opioids were at greater risk of opioid misuse after 1 year.

This is a “landmark” trial with “practice-changing” results, senior author Christine Lin, PhD, with the University of Sydney, told this news organization.

“Before this trial, we did not have good evidence on whether opioids were effective for acute low back pain or neck pain, yet opioids were one of the most commonly used medicines for these conditions,” Dr. Lin explained.

On the basis of these results, “opioids should not be recommended at all for acute low back pain and neck pain,” Dr. Lin said.

Results of the OPAL study were published online in The Lancet.

Rigorous trial

The trial was conducted in 157 primary care or emergency department sites in Australia and involved 347 adults who had been experiencing low back pain, neck pain, or both for 12 weeks or less.

They were randomly allocated (1:1) to receive guideline-recommended care (reassurance and advice to stay active) plus an opioid (oxycodone up to 20 mg daily) or identical placebo for up to 6 weeks. Naloxone was provided to help prevent opioid-induced constipation and improve blinding.

The primary outcome was pain severity at 6 weeks, measured with the pain severity subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory (10-point scale).

After 6 weeks, opioid therapy offered no more relief for acute back/neck pain or functional improvement than placebo.

The mean pain score at 6 weeks was 2.78 in the opioid group, versus 2.25 in the placebo group (adjusted mean difference, 0.53; 95% confidence interval, –0.00 to 1.07; P = .051). At 1 year, mean pain scores in the placebo group were slightly lower than in the opioid group (1.8 vs. 2.4).

In addition, there was a doubling of the risk of opioid misuse at 1 year among patients randomly allocated to receive opioid therapy for 6 weeks, compared with those allocated to receive placebo for 6 weeks.

At 1 year, 24 (20%) of 123 of the patients who received opioids were at risk of misuse, as indicated by the Current Opioid Misuse Measure scale, compared with 13 (10%) of 128 patients in the placebo group (P = .049). The COMM is a widely used measure of current aberrant drug-related behavior among patients with chronic pain who are being prescribed opioid therapy.

Results raise ‘serious questions’

“I believe the findings of the study will need to be disseminated to the doctors and patients, so they receive this latest evidence on opioids,” Dr. Lin said in an interview.

“We need to reassure doctors and patients that most people with acute low back pain and neck pain recover well with time (usually by 6 weeks), so management is simple – staying active, avoiding bed rest, and, if necessary, using a heat pack for short term pain relief. If drugs are required, consider anti-inflammatory drugs,” Dr. Lin added.

The authors of a linked comment say the OPAL trial “raises serious questions about the use of opioid therapy for acute low back and neck pain.”

Mark Sullivan, MD, PhD, and Jane Ballantyne, MD, with the University of Washington, Seattle, note that current clinical guidelines recommend opioids for patients with acute back and neck pain when other drug treatments fail or are contraindicated.

“As many as two-thirds of patients might receive an opioid when presenting for care of back or neck pain. It is time to re-examine these guidelines and these practices,” Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Ballantyne conclude.

Funding for the OPAL study was provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council, the University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine and Health, and SafeWork SA. The study authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sullivan and Dr. Ballantyne are board members (unpaid) of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing and have been paid consultants in opioid litigation.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New international guidelines on opioid deprescribing

An expert panel of pain management clinicians has released what they say are the first international guidelines for general practitioners on opioid analgesic deprescribing in adults.

The recommendations describe best practices for stopping opioid therapy and emphasize slow tapering and individualized deprescribing plans tailored to each patient.

Developed by general practitioners, pain specialists, addiction specialists, pharmacists, registered nurses, consumers, and physiotherapists, the guidelines note that deprescribing may not be appropriate for every patient and that stopping abruptly can be associated with an increased risk of overdose.

“Internationally, we were seeing significant harms from opioids but also significant harms from unsolicited and abrupt opioid cessation,” said lead author Aili Langford, PhD, who conducted the study as a doctoral student at the University of Sydney. “It was clear that recommendations to support safe and person-centered opioid deprescribing were required.”

The findings were published online in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Deprescribing plan

The consensus guidelines include 11 recommendations for deprescribing in adult patients who take at least one opioid for any type of pain.

Recommendations include implementing a deprescribing plan when opioids are first prescribed and gradual and individualized deprescribing, with regular monitoring and review.

Clinicians should consider opioid deprescribing in patients who experience no clinically meaningful improvement in function, quality of life, or pain at high risk with opioid therapy, they note. Patients who are at high risk for opioid-related harm are also good candidates for deprescribing.

Stopping opioid therapy is not recommended for patients with severe opioid use disorder (OUD). In those patients, medication-assisted OUD treatment and other evidence-based interventions are recommended.

“Opioids can be effective in pain management,” co-author Carl Schneider, PhD, an associate professor of pharmacy at the University of Sydney, said in a press release. “However, over the longer term, the risk of harms may outweigh the benefits.”

A ‘global problem’

Commenting on the guidelines, Orman Trent Hall, DO, assistant professor of addiction medicine, department of psychiatry and behavioral health at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said they are similar to recommendations published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 and 2022 but offer additional information that could be helpful.

“This new guideline provides more explicit advice about tapering and withdrawal management, which may be useful to practitioners. The opioid crisis is a global problem, and while individual countries may require local solutions, the new international guideline may offer a framework for approaching this issue,” he said.

The guideline’s emphasis on the potential risks of deprescribing in some patients is also key, Dr. Hall added. Patients who are tapering off opioid therapy may have worsening pain and loss of function that can affect their quality of life.

“Patients may also experience psychological harm and increased risk of opioid use disorder and death by suicide following opioid deprescribing,” Dr. Hall said. “Therefore, it is important for providers to carefully weigh the risks of prescribing and deprescribing and engage patients with person-centered communication and shared decision-making.”

The work was funded by grants from the University of Sydney and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Full disclosures are available in the original article. Dr. Hall has provided expert opinion to the health care consultancy firm Lumanity and Emergent BioSolutions regarding the overdose crisis.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An expert panel of pain management clinicians has released what they say are the first international guidelines for general practitioners on opioid analgesic deprescribing in adults.

The recommendations describe best practices for stopping opioid therapy and emphasize slow tapering and individualized deprescribing plans tailored to each patient.

Developed by general practitioners, pain specialists, addiction specialists, pharmacists, registered nurses, consumers, and physiotherapists, the guidelines note that deprescribing may not be appropriate for every patient and that stopping abruptly can be associated with an increased risk of overdose.

“Internationally, we were seeing significant harms from opioids but also significant harms from unsolicited and abrupt opioid cessation,” said lead author Aili Langford, PhD, who conducted the study as a doctoral student at the University of Sydney. “It was clear that recommendations to support safe and person-centered opioid deprescribing were required.”

The findings were published online in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Deprescribing plan

The consensus guidelines include 11 recommendations for deprescribing in adult patients who take at least one opioid for any type of pain.

Recommendations include implementing a deprescribing plan when opioids are first prescribed and gradual and individualized deprescribing, with regular monitoring and review.

Clinicians should consider opioid deprescribing in patients who experience no clinically meaningful improvement in function, quality of life, or pain at high risk with opioid therapy, they note. Patients who are at high risk for opioid-related harm are also good candidates for deprescribing.

Stopping opioid therapy is not recommended for patients with severe opioid use disorder (OUD). In those patients, medication-assisted OUD treatment and other evidence-based interventions are recommended.

“Opioids can be effective in pain management,” co-author Carl Schneider, PhD, an associate professor of pharmacy at the University of Sydney, said in a press release. “However, over the longer term, the risk of harms may outweigh the benefits.”

A ‘global problem’

Commenting on the guidelines, Orman Trent Hall, DO, assistant professor of addiction medicine, department of psychiatry and behavioral health at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said they are similar to recommendations published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 and 2022 but offer additional information that could be helpful.

“This new guideline provides more explicit advice about tapering and withdrawal management, which may be useful to practitioners. The opioid crisis is a global problem, and while individual countries may require local solutions, the new international guideline may offer a framework for approaching this issue,” he said.

The guideline’s emphasis on the potential risks of deprescribing in some patients is also key, Dr. Hall added. Patients who are tapering off opioid therapy may have worsening pain and loss of function that can affect their quality of life.

“Patients may also experience psychological harm and increased risk of opioid use disorder and death by suicide following opioid deprescribing,” Dr. Hall said. “Therefore, it is important for providers to carefully weigh the risks of prescribing and deprescribing and engage patients with person-centered communication and shared decision-making.”

The work was funded by grants from the University of Sydney and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Full disclosures are available in the original article. Dr. Hall has provided expert opinion to the health care consultancy firm Lumanity and Emergent BioSolutions regarding the overdose crisis.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An expert panel of pain management clinicians has released what they say are the first international guidelines for general practitioners on opioid analgesic deprescribing in adults.

The recommendations describe best practices for stopping opioid therapy and emphasize slow tapering and individualized deprescribing plans tailored to each patient.

Developed by general practitioners, pain specialists, addiction specialists, pharmacists, registered nurses, consumers, and physiotherapists, the guidelines note that deprescribing may not be appropriate for every patient and that stopping abruptly can be associated with an increased risk of overdose.

“Internationally, we were seeing significant harms from opioids but also significant harms from unsolicited and abrupt opioid cessation,” said lead author Aili Langford, PhD, who conducted the study as a doctoral student at the University of Sydney. “It was clear that recommendations to support safe and person-centered opioid deprescribing were required.”

The findings were published online in the Medical Journal of Australia.

Deprescribing plan

The consensus guidelines include 11 recommendations for deprescribing in adult patients who take at least one opioid for any type of pain.

Recommendations include implementing a deprescribing plan when opioids are first prescribed and gradual and individualized deprescribing, with regular monitoring and review.

Clinicians should consider opioid deprescribing in patients who experience no clinically meaningful improvement in function, quality of life, or pain at high risk with opioid therapy, they note. Patients who are at high risk for opioid-related harm are also good candidates for deprescribing.

Stopping opioid therapy is not recommended for patients with severe opioid use disorder (OUD). In those patients, medication-assisted OUD treatment and other evidence-based interventions are recommended.

“Opioids can be effective in pain management,” co-author Carl Schneider, PhD, an associate professor of pharmacy at the University of Sydney, said in a press release. “However, over the longer term, the risk of harms may outweigh the benefits.”

A ‘global problem’

Commenting on the guidelines, Orman Trent Hall, DO, assistant professor of addiction medicine, department of psychiatry and behavioral health at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, said they are similar to recommendations published by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2016 and 2022 but offer additional information that could be helpful.

“This new guideline provides more explicit advice about tapering and withdrawal management, which may be useful to practitioners. The opioid crisis is a global problem, and while individual countries may require local solutions, the new international guideline may offer a framework for approaching this issue,” he said.

The guideline’s emphasis on the potential risks of deprescribing in some patients is also key, Dr. Hall added. Patients who are tapering off opioid therapy may have worsening pain and loss of function that can affect their quality of life.

“Patients may also experience psychological harm and increased risk of opioid use disorder and death by suicide following opioid deprescribing,” Dr. Hall said. “Therefore, it is important for providers to carefully weigh the risks of prescribing and deprescribing and engage patients with person-centered communication and shared decision-making.”

The work was funded by grants from the University of Sydney and the National Health and Medical Research Council. Full disclosures are available in the original article. Dr. Hall has provided expert opinion to the health care consultancy firm Lumanity and Emergent BioSolutions regarding the overdose crisis.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

New DEA CME mandate affects 2 million prescribers

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 mandates that all Drug Enforcement Administration–registered physicians and health care providers complete a one-time, 8-hour CME training on managing and treating opioid and other substance abuse disorders. This requirement goes into effect on June 27, 2023. New DEA registrants must also comply. Veterinarians are exempt.

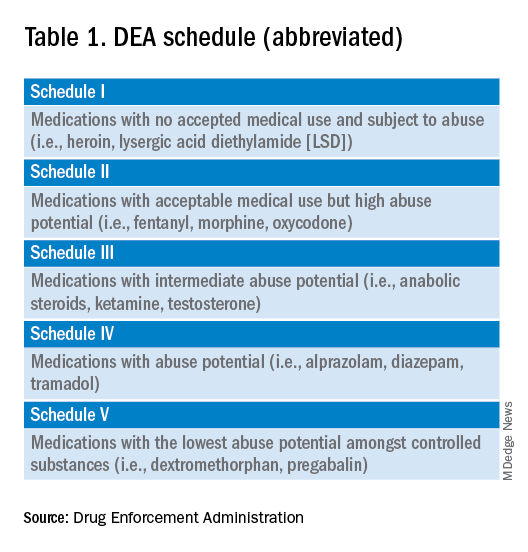

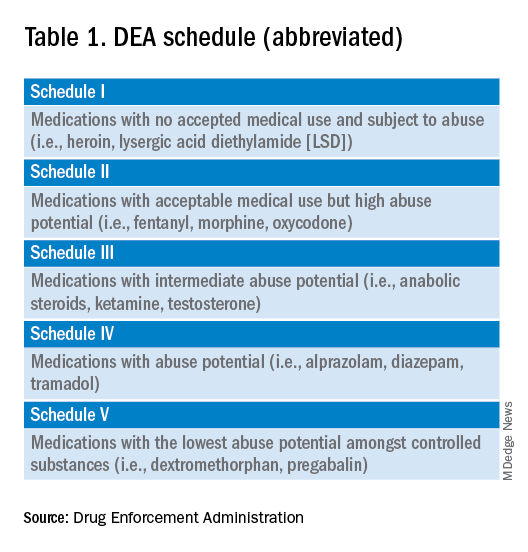

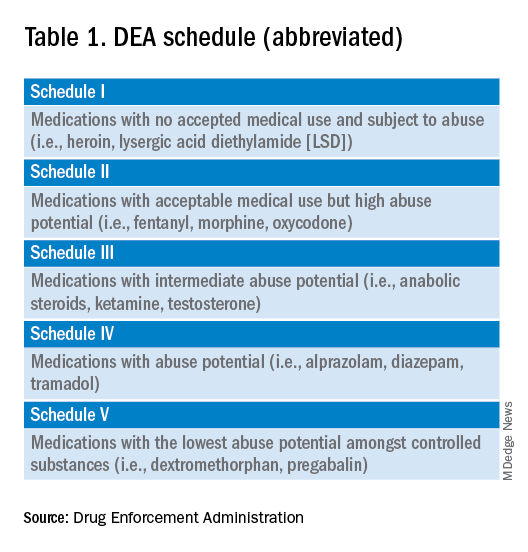

A DEA registration is required to prescribe any controlled substance. The DEA categorizes these as Schedule I-V, with V being the least likely to be abused (Table 1). For example, opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone, and morphine are Schedule II. Medications without abuse potential are not scheduled.

Will 16 million hours of opioid education save lives?

One should not underestimate the sweeping scope of this new federal requirement. DEA registrants include physicians and other health care providers such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and dentists. That is 8 hours per provider x 2 million providers: 16 million hours of CME!

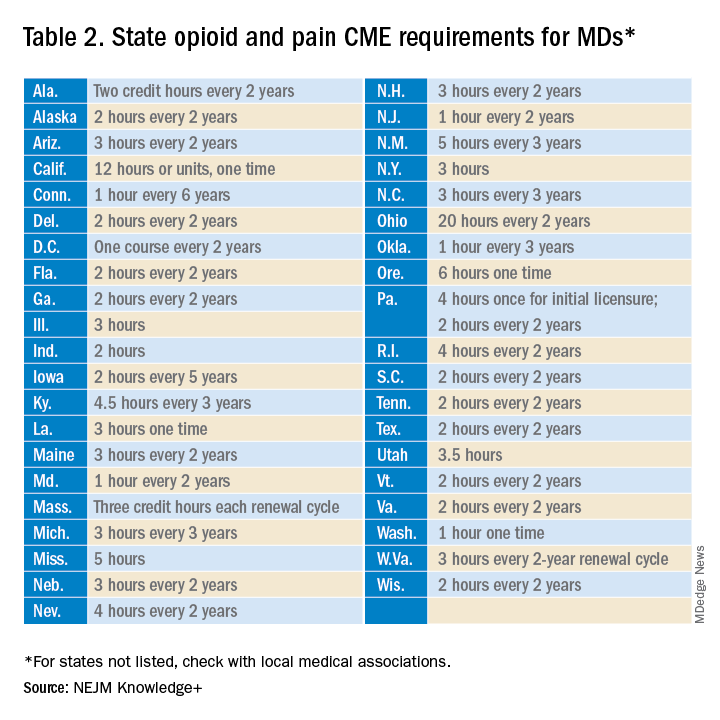

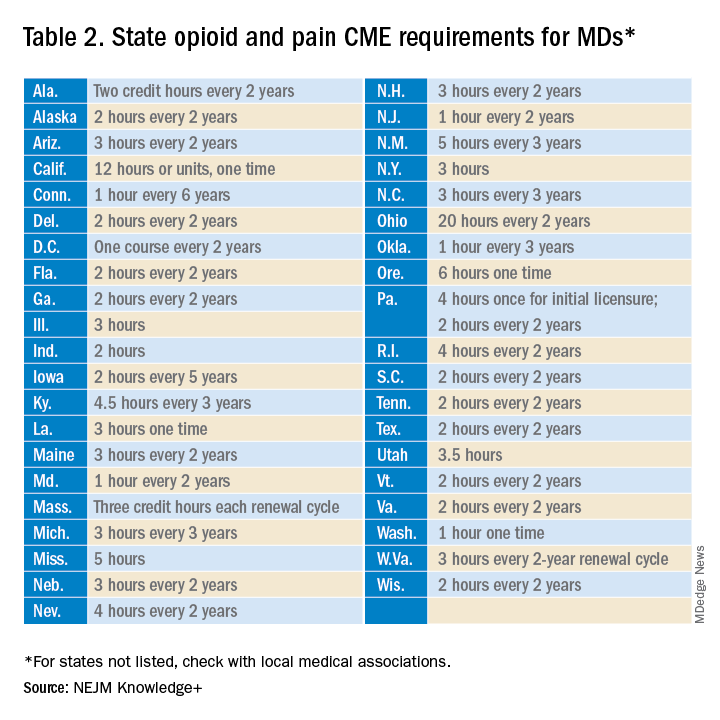

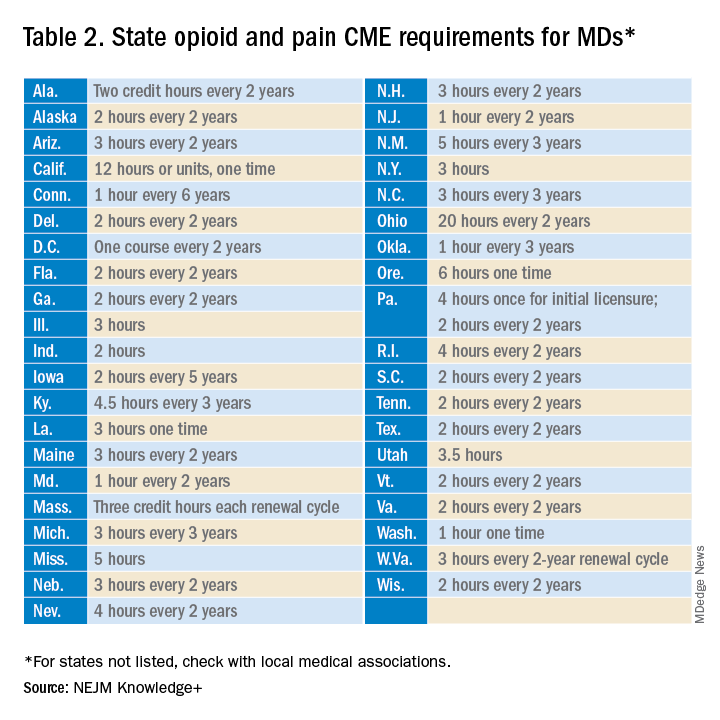

Many states already require 1 or more hours of opioid training and pain management as part of their relicensure requirements (Table 2). To avoid redundancy, the DEA-mandated 8-hour training satisfies the various states’ requirements.

An uncompensated mandate

Physicians are no strangers to lifelong learning and most eagerly pursue educational opportunities. Though some physicians may have CME time and stipends allocated by their employers, many others, such as the approximately 50,000 locum tenens doctors, do not. However, as enthusiastic as these physicians may be about this new CME course, they will likely lose a day of seeing patients (and income) to comply with this new obligation.

Not just pain doctors

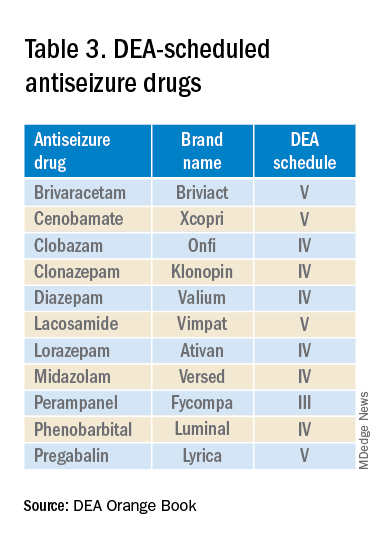

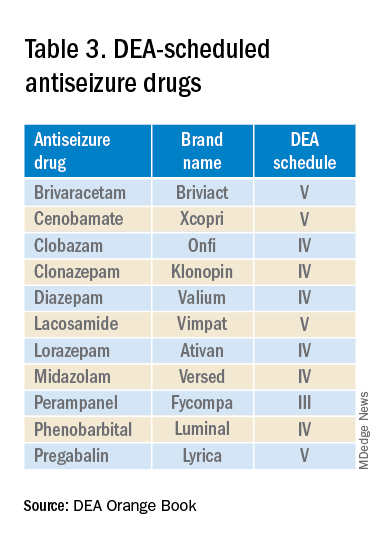

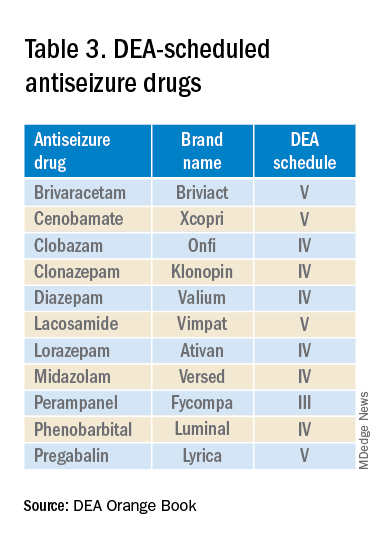

The mandate’s broad brush includes many health care providers who hold DEA certificates but do not prescribe opioids. For example, as a general neurologist and epileptologist, I do not treat patients with chronic pain and cannot remember the last time I wrote an opioid prescription. However, I frequently prescribe lacosamide, a Schedule V drug. A surprisingly large number of antiseizure drugs are Schedule III, IV, or V drugs (Table 3).

Real-world abuse?

How often scheduled antiseizure drugs are diverted or abused in an epilepsy population is unknown but appears to be infrequent. For example, perampanel abuse has not been reported despite its classification as a Schedule III drug. Anecdotally, in more than 40 years of clinical practice, I have never known a patient with epilepsy to abuse their antiseizure medications.

Take the course

Many organizations are happy to charge for the new 8-hour course. For example, the Tennessee Medical Association offers the training for $299 online or $400 in person. Materials from Elite Learning satisfy the 8-hour requirement for $80. However, NEJM Knowledge+ provides a complimentary 10-hour DEA-compliant course.

I recently completed the NEJM course. The information was thorough and took the whole 10 hours to finish. As excellent as it was, the content was only tangentially relevant to my clinical practice.

Conclusions

To obtain or renew a DEA certificate, neurologists, epilepsy specialists, and many other health care providers must comply with the new 8-hour CME opioid training mandate. Because the course requires 1 day to complete, health care providers would be prudent to obtain their CME well before their DEA certificate expires.

Though efforts to control the morbidity and mortality of the opioid epidemic are laudatory, perhaps the training should be more targeted to physicians who actually prescribe opioids rather than every DEA registrant. In the meantime, whether 16 million CME hours will save lives remains to be seen.

Dr. Wilner is professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis. He reported a conflict of interest with Accordant Health Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 mandates that all Drug Enforcement Administration–registered physicians and health care providers complete a one-time, 8-hour CME training on managing and treating opioid and other substance abuse disorders. This requirement goes into effect on June 27, 2023. New DEA registrants must also comply. Veterinarians are exempt.

A DEA registration is required to prescribe any controlled substance. The DEA categorizes these as Schedule I-V, with V being the least likely to be abused (Table 1). For example, opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone, and morphine are Schedule II. Medications without abuse potential are not scheduled.

Will 16 million hours of opioid education save lives?

One should not underestimate the sweeping scope of this new federal requirement. DEA registrants include physicians and other health care providers such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and dentists. That is 8 hours per provider x 2 million providers: 16 million hours of CME!

Many states already require 1 or more hours of opioid training and pain management as part of their relicensure requirements (Table 2). To avoid redundancy, the DEA-mandated 8-hour training satisfies the various states’ requirements.

An uncompensated mandate

Physicians are no strangers to lifelong learning and most eagerly pursue educational opportunities. Though some physicians may have CME time and stipends allocated by their employers, many others, such as the approximately 50,000 locum tenens doctors, do not. However, as enthusiastic as these physicians may be about this new CME course, they will likely lose a day of seeing patients (and income) to comply with this new obligation.

Not just pain doctors

The mandate’s broad brush includes many health care providers who hold DEA certificates but do not prescribe opioids. For example, as a general neurologist and epileptologist, I do not treat patients with chronic pain and cannot remember the last time I wrote an opioid prescription. However, I frequently prescribe lacosamide, a Schedule V drug. A surprisingly large number of antiseizure drugs are Schedule III, IV, or V drugs (Table 3).

Real-world abuse?

How often scheduled antiseizure drugs are diverted or abused in an epilepsy population is unknown but appears to be infrequent. For example, perampanel abuse has not been reported despite its classification as a Schedule III drug. Anecdotally, in more than 40 years of clinical practice, I have never known a patient with epilepsy to abuse their antiseizure medications.

Take the course

Many organizations are happy to charge for the new 8-hour course. For example, the Tennessee Medical Association offers the training for $299 online or $400 in person. Materials from Elite Learning satisfy the 8-hour requirement for $80. However, NEJM Knowledge+ provides a complimentary 10-hour DEA-compliant course.

I recently completed the NEJM course. The information was thorough and took the whole 10 hours to finish. As excellent as it was, the content was only tangentially relevant to my clinical practice.

Conclusions

To obtain or renew a DEA certificate, neurologists, epilepsy specialists, and many other health care providers must comply with the new 8-hour CME opioid training mandate. Because the course requires 1 day to complete, health care providers would be prudent to obtain their CME well before their DEA certificate expires.

Though efforts to control the morbidity and mortality of the opioid epidemic are laudatory, perhaps the training should be more targeted to physicians who actually prescribe opioids rather than every DEA registrant. In the meantime, whether 16 million CME hours will save lives remains to be seen.

Dr. Wilner is professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis. He reported a conflict of interest with Accordant Health Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 mandates that all Drug Enforcement Administration–registered physicians and health care providers complete a one-time, 8-hour CME training on managing and treating opioid and other substance abuse disorders. This requirement goes into effect on June 27, 2023. New DEA registrants must also comply. Veterinarians are exempt.

A DEA registration is required to prescribe any controlled substance. The DEA categorizes these as Schedule I-V, with V being the least likely to be abused (Table 1). For example, opioids like fentanyl, oxycodone, and morphine are Schedule II. Medications without abuse potential are not scheduled.

Will 16 million hours of opioid education save lives?

One should not underestimate the sweeping scope of this new federal requirement. DEA registrants include physicians and other health care providers such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and dentists. That is 8 hours per provider x 2 million providers: 16 million hours of CME!

Many states already require 1 or more hours of opioid training and pain management as part of their relicensure requirements (Table 2). To avoid redundancy, the DEA-mandated 8-hour training satisfies the various states’ requirements.

An uncompensated mandate

Physicians are no strangers to lifelong learning and most eagerly pursue educational opportunities. Though some physicians may have CME time and stipends allocated by their employers, many others, such as the approximately 50,000 locum tenens doctors, do not. However, as enthusiastic as these physicians may be about this new CME course, they will likely lose a day of seeing patients (and income) to comply with this new obligation.

Not just pain doctors

The mandate’s broad brush includes many health care providers who hold DEA certificates but do not prescribe opioids. For example, as a general neurologist and epileptologist, I do not treat patients with chronic pain and cannot remember the last time I wrote an opioid prescription. However, I frequently prescribe lacosamide, a Schedule V drug. A surprisingly large number of antiseizure drugs are Schedule III, IV, or V drugs (Table 3).

Real-world abuse?

How often scheduled antiseizure drugs are diverted or abused in an epilepsy population is unknown but appears to be infrequent. For example, perampanel abuse has not been reported despite its classification as a Schedule III drug. Anecdotally, in more than 40 years of clinical practice, I have never known a patient with epilepsy to abuse their antiseizure medications.

Take the course

Many organizations are happy to charge for the new 8-hour course. For example, the Tennessee Medical Association offers the training for $299 online or $400 in person. Materials from Elite Learning satisfy the 8-hour requirement for $80. However, NEJM Knowledge+ provides a complimentary 10-hour DEA-compliant course.

I recently completed the NEJM course. The information was thorough and took the whole 10 hours to finish. As excellent as it was, the content was only tangentially relevant to my clinical practice.

Conclusions

To obtain or renew a DEA certificate, neurologists, epilepsy specialists, and many other health care providers must comply with the new 8-hour CME opioid training mandate. Because the course requires 1 day to complete, health care providers would be prudent to obtain their CME well before their DEA certificate expires.

Though efforts to control the morbidity and mortality of the opioid epidemic are laudatory, perhaps the training should be more targeted to physicians who actually prescribe opioids rather than every DEA registrant. In the meantime, whether 16 million CME hours will save lives remains to be seen.

Dr. Wilner is professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis. He reported a conflict of interest with Accordant Health Services.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Migraine device expands treatment possibilities