User login

Erenumab beats topiramate for migraine in first head-to-head trial

, according to data from almost 800 patients in the first head-to-head trial of its kind.

The findings suggest that erenumab may help overcome longstanding issues with migraine medication adherence, and additional supportive data may alter treatment sequencing, reported lead author Uwe Reuter, MD, professor at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and colleagues.

“So far, no study has been done in order to compare the efficacy of a monoclonal antibody targeting the CGRP pathway to that of a standard of care oral preventive drug,” the investigators wrote in Cephalalgia.

The phase 4 HER-MES trial aimed to address this knowledge gap by enrolling 777 adult patients with a history of migraine. All patients reported migraine with or without aura for at least 1 year prior to screening. At baseline, most patients (65%) reported 8-14 migraine days per months, followed by 4-7 days (24.0%), and at least 15 days (11.0%). No patients had previously received topiramate or a CGRP-targeting agent.

“HER-MES includes a broad migraine population with two-thirds of the patients in the high-frequency migraine spectrum,” the investigators noted. “Despite a mean disease duration of about 20 years, almost 60% of the patients had not received previous prophylactic treatment, which underlines the long-standing problem of undertreatment in migraine.”

The trial had a double-dummy design; patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either subcutaneous erenumab (70 or 140 mg/month) plus oral placebo, or oral topiramate (50-100 mg/day) plus subcutaneous placebo. The topiramate dose was uptitrated over the first 6 weeks. Treatments were given for a total of 24 weeks or until discontinuation due to adverse events, which was the primary endpoint. The secondary endpoint was efficacy over months 4-6, defined as at least 50% reduction in monthly migraine days, compared with baseline. Other patient-reported outcomes were also evaluated.

After 24 weeks, 95.1% of patients were still enrolled in the trial. Discontinuations due to adverse events were almost four times as common in the topiramate group than the erenumab group (38.9% vs. 10.6%; odds ratio [OR], 0.19; confidence interval, 0.13-0.27; P less than .001). Efficacy findings followed suit, with 55.4% of patients in the erenumab group reporting at least 50% reduction in monthly migraine days, compared with 31.2% of patients in the topiramate group (OR, 2.76; 95% CI, 2.06-3.71; P less than.001).

Erenumab significantly improved monthly migraine days, headache impact test (HIT-6) scores, and short form health survey version (SF-35v2) scores, including physical and mental components (P less than .001 for all).

Safety profiles aligned with previous findings.

“Compared to topiramate, treatment with erenumab has a superior tolerability profile and a significantly higher efficacy,” the investigators concluded. “HER-MES supports the potential of erenumab in overcoming issues of low adherence in clinical practice observed with topiramate, lessening migraine burden, and improving quality of life in a broad migraine population.”

Superior tolerability

Commenting on the study, Alan Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said this is “a very important, very well conducted trial that documents what many of us already suspected; erenumab clearly has better tolerability than topiramate as well as better efficacy.”

Dr. Rapoport, a past president of the International Headache Society, said the study highlights an area of unmet need in neurology practice.

“Despite most patients in the trial having chronic headaches for 20 years, 60% of them had never received preventive treatment,” he said, noting that this reflects current practice in the United States.

Dr. Rapoport said primary care providers in the United States prescribe preventive migraine medications to 10%-15% of eligible patients. Prescribing rates for general neurologists are slightly higher, he said, ranging from 35% to 40%, while headache specialists prescribe 70%-90% of the time.

“How can we improve this situation?” Dr. Rapoport asked. “For years we have tried to improve it with education, but we need to do a better job. We need to educate our primary care physicians in more practical ways. We have to teach them how to make a diagnosis of high frequency migraine and chronic migraine and strongly suggest that those patients be put on appropriate preventive medications.”

Barriers to care may be systemic, according to Dr. Rapoport.

“One issue in the U.S. is that patients with commercial insurance are almost always required to fail two or three categories of older oral preventive migraine medications before they can get a monoclonal antibody or gepants for prevention,” he said. “It would be good if we could change that system so that patients that absolutely need the better tolerated, more effective preventive medications could get them sooner rather than later. This will help them feel and function better, with less pain, and eventually bring down the cost of migraine therapy.”

While Dr. Reuter and colleagues concluded that revised treatment sequencing may be warranted after more trials show similar results, Dr. Rapoport suggested that “this was such a large, well-performed, 6-month study with few dropouts, that further trials to confirm these findings are unnecessary, in my opinion.”

The HER-MES trial was funded by Novartis. Dr. Reuter and colleagues disclosed additional relationships with Eli Lilly, Teva Pharmaceutical, Allergan, and others. Dr. Rapoport was involved in early topiramate trials for prevention and migraine, and is a speaker for Amgen.

, according to data from almost 800 patients in the first head-to-head trial of its kind.

The findings suggest that erenumab may help overcome longstanding issues with migraine medication adherence, and additional supportive data may alter treatment sequencing, reported lead author Uwe Reuter, MD, professor at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and colleagues.

“So far, no study has been done in order to compare the efficacy of a monoclonal antibody targeting the CGRP pathway to that of a standard of care oral preventive drug,” the investigators wrote in Cephalalgia.

The phase 4 HER-MES trial aimed to address this knowledge gap by enrolling 777 adult patients with a history of migraine. All patients reported migraine with or without aura for at least 1 year prior to screening. At baseline, most patients (65%) reported 8-14 migraine days per months, followed by 4-7 days (24.0%), and at least 15 days (11.0%). No patients had previously received topiramate or a CGRP-targeting agent.

“HER-MES includes a broad migraine population with two-thirds of the patients in the high-frequency migraine spectrum,” the investigators noted. “Despite a mean disease duration of about 20 years, almost 60% of the patients had not received previous prophylactic treatment, which underlines the long-standing problem of undertreatment in migraine.”

The trial had a double-dummy design; patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either subcutaneous erenumab (70 or 140 mg/month) plus oral placebo, or oral topiramate (50-100 mg/day) plus subcutaneous placebo. The topiramate dose was uptitrated over the first 6 weeks. Treatments were given for a total of 24 weeks or until discontinuation due to adverse events, which was the primary endpoint. The secondary endpoint was efficacy over months 4-6, defined as at least 50% reduction in monthly migraine days, compared with baseline. Other patient-reported outcomes were also evaluated.

After 24 weeks, 95.1% of patients were still enrolled in the trial. Discontinuations due to adverse events were almost four times as common in the topiramate group than the erenumab group (38.9% vs. 10.6%; odds ratio [OR], 0.19; confidence interval, 0.13-0.27; P less than .001). Efficacy findings followed suit, with 55.4% of patients in the erenumab group reporting at least 50% reduction in monthly migraine days, compared with 31.2% of patients in the topiramate group (OR, 2.76; 95% CI, 2.06-3.71; P less than.001).

Erenumab significantly improved monthly migraine days, headache impact test (HIT-6) scores, and short form health survey version (SF-35v2) scores, including physical and mental components (P less than .001 for all).

Safety profiles aligned with previous findings.

“Compared to topiramate, treatment with erenumab has a superior tolerability profile and a significantly higher efficacy,” the investigators concluded. “HER-MES supports the potential of erenumab in overcoming issues of low adherence in clinical practice observed with topiramate, lessening migraine burden, and improving quality of life in a broad migraine population.”

Superior tolerability

Commenting on the study, Alan Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said this is “a very important, very well conducted trial that documents what many of us already suspected; erenumab clearly has better tolerability than topiramate as well as better efficacy.”

Dr. Rapoport, a past president of the International Headache Society, said the study highlights an area of unmet need in neurology practice.

“Despite most patients in the trial having chronic headaches for 20 years, 60% of them had never received preventive treatment,” he said, noting that this reflects current practice in the United States.

Dr. Rapoport said primary care providers in the United States prescribe preventive migraine medications to 10%-15% of eligible patients. Prescribing rates for general neurologists are slightly higher, he said, ranging from 35% to 40%, while headache specialists prescribe 70%-90% of the time.

“How can we improve this situation?” Dr. Rapoport asked. “For years we have tried to improve it with education, but we need to do a better job. We need to educate our primary care physicians in more practical ways. We have to teach them how to make a diagnosis of high frequency migraine and chronic migraine and strongly suggest that those patients be put on appropriate preventive medications.”

Barriers to care may be systemic, according to Dr. Rapoport.

“One issue in the U.S. is that patients with commercial insurance are almost always required to fail two or three categories of older oral preventive migraine medications before they can get a monoclonal antibody or gepants for prevention,” he said. “It would be good if we could change that system so that patients that absolutely need the better tolerated, more effective preventive medications could get them sooner rather than later. This will help them feel and function better, with less pain, and eventually bring down the cost of migraine therapy.”

While Dr. Reuter and colleagues concluded that revised treatment sequencing may be warranted after more trials show similar results, Dr. Rapoport suggested that “this was such a large, well-performed, 6-month study with few dropouts, that further trials to confirm these findings are unnecessary, in my opinion.”

The HER-MES trial was funded by Novartis. Dr. Reuter and colleagues disclosed additional relationships with Eli Lilly, Teva Pharmaceutical, Allergan, and others. Dr. Rapoport was involved in early topiramate trials for prevention and migraine, and is a speaker for Amgen.

, according to data from almost 800 patients in the first head-to-head trial of its kind.

The findings suggest that erenumab may help overcome longstanding issues with migraine medication adherence, and additional supportive data may alter treatment sequencing, reported lead author Uwe Reuter, MD, professor at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and colleagues.

“So far, no study has been done in order to compare the efficacy of a monoclonal antibody targeting the CGRP pathway to that of a standard of care oral preventive drug,” the investigators wrote in Cephalalgia.

The phase 4 HER-MES trial aimed to address this knowledge gap by enrolling 777 adult patients with a history of migraine. All patients reported migraine with or without aura for at least 1 year prior to screening. At baseline, most patients (65%) reported 8-14 migraine days per months, followed by 4-7 days (24.0%), and at least 15 days (11.0%). No patients had previously received topiramate or a CGRP-targeting agent.

“HER-MES includes a broad migraine population with two-thirds of the patients in the high-frequency migraine spectrum,” the investigators noted. “Despite a mean disease duration of about 20 years, almost 60% of the patients had not received previous prophylactic treatment, which underlines the long-standing problem of undertreatment in migraine.”

The trial had a double-dummy design; patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either subcutaneous erenumab (70 or 140 mg/month) plus oral placebo, or oral topiramate (50-100 mg/day) plus subcutaneous placebo. The topiramate dose was uptitrated over the first 6 weeks. Treatments were given for a total of 24 weeks or until discontinuation due to adverse events, which was the primary endpoint. The secondary endpoint was efficacy over months 4-6, defined as at least 50% reduction in monthly migraine days, compared with baseline. Other patient-reported outcomes were also evaluated.

After 24 weeks, 95.1% of patients were still enrolled in the trial. Discontinuations due to adverse events were almost four times as common in the topiramate group than the erenumab group (38.9% vs. 10.6%; odds ratio [OR], 0.19; confidence interval, 0.13-0.27; P less than .001). Efficacy findings followed suit, with 55.4% of patients in the erenumab group reporting at least 50% reduction in monthly migraine days, compared with 31.2% of patients in the topiramate group (OR, 2.76; 95% CI, 2.06-3.71; P less than.001).

Erenumab significantly improved monthly migraine days, headache impact test (HIT-6) scores, and short form health survey version (SF-35v2) scores, including physical and mental components (P less than .001 for all).

Safety profiles aligned with previous findings.

“Compared to topiramate, treatment with erenumab has a superior tolerability profile and a significantly higher efficacy,” the investigators concluded. “HER-MES supports the potential of erenumab in overcoming issues of low adherence in clinical practice observed with topiramate, lessening migraine burden, and improving quality of life in a broad migraine population.”

Superior tolerability

Commenting on the study, Alan Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews, said this is “a very important, very well conducted trial that documents what many of us already suspected; erenumab clearly has better tolerability than topiramate as well as better efficacy.”

Dr. Rapoport, a past president of the International Headache Society, said the study highlights an area of unmet need in neurology practice.

“Despite most patients in the trial having chronic headaches for 20 years, 60% of them had never received preventive treatment,” he said, noting that this reflects current practice in the United States.

Dr. Rapoport said primary care providers in the United States prescribe preventive migraine medications to 10%-15% of eligible patients. Prescribing rates for general neurologists are slightly higher, he said, ranging from 35% to 40%, while headache specialists prescribe 70%-90% of the time.

“How can we improve this situation?” Dr. Rapoport asked. “For years we have tried to improve it with education, but we need to do a better job. We need to educate our primary care physicians in more practical ways. We have to teach them how to make a diagnosis of high frequency migraine and chronic migraine and strongly suggest that those patients be put on appropriate preventive medications.”

Barriers to care may be systemic, according to Dr. Rapoport.

“One issue in the U.S. is that patients with commercial insurance are almost always required to fail two or three categories of older oral preventive migraine medications before they can get a monoclonal antibody or gepants for prevention,” he said. “It would be good if we could change that system so that patients that absolutely need the better tolerated, more effective preventive medications could get them sooner rather than later. This will help them feel and function better, with less pain, and eventually bring down the cost of migraine therapy.”

While Dr. Reuter and colleagues concluded that revised treatment sequencing may be warranted after more trials show similar results, Dr. Rapoport suggested that “this was such a large, well-performed, 6-month study with few dropouts, that further trials to confirm these findings are unnecessary, in my opinion.”

The HER-MES trial was funded by Novartis. Dr. Reuter and colleagues disclosed additional relationships with Eli Lilly, Teva Pharmaceutical, Allergan, and others. Dr. Rapoport was involved in early topiramate trials for prevention and migraine, and is a speaker for Amgen.

FROM CEPHALALGIA

U.S. overdose deaths hit an all-time high

a 28.5% increase from the previous year.

Deaths in some states rose even more precipitously. Vermont saw an almost 70% increase, and drug overdose deaths in West Virginia increased by 62%. Many states, including Alabama, California, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Washington, had a 45%-50% rise in overdose deaths.

The data released by the CDC was provisional, as there is generally a lag between a reported overdose and confirmation of the death to the National Vital Statistics System. The agency uses statistical models that render the counts almost 100% accurate, the CDC says.

The vast majority (73,757) of overdose deaths involved opioids – with most of those (62,338) involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Federal officials said that one American died every 5 minutes from an overdose, or 265 a day.

“We have to acknowledge what this is – it is a crisis,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra told reporters on a call.

“As much as the numbers speak so vividly, they don’t tell the whole story. We see it in the faces of grieving families and all those overworked caregivers. You hear it every time you get that panicked 911 phone call, you read it in obituaries of sons and daughters who left us way too soon,” Mr. Becerra said.

Rahul Gupta, MD, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said that “this is unacceptable, and it requires an unprecedented response.”

Dr. Gupta, who noted that he has a waiver to treat substance use disorder patients with buprenorphine, said he’s seen “first-hand the heartbreak of the overdose epidemic,” adding that, with 23 years in practice, “I’ve learned that an overdose is a cry for help and for far too many people that cry goes unanswered.”

Both Mr. Becerra and Dr. Gupta called on Congress to pass President Joe Biden’s fiscal 2022 budget request, noting that it calls for $41 billion – a $669 million increase from fiscal year 2021 – to go to agencies working on drug interdiction and substance use prevention, treatment, and recovery support.

Dr. Gupta also announced that the administration was releasing a model law that could be used by state legislatures to help standardize policies on making the overdose antidote naloxone more accessible. Currently, such policies are a patchwork across the nation.

In addition, the federal government is newly supporting harm reduction, Mr. Becerra said. This means federal money can be used by clinics and outreach programs to buy fentanyl test strips, which they can then distribute to drug users.

“It’s important for Americans to have the ability to make sure that they can test for fentanyl in the substance,” Dr. Gupta said.

Fake pills, fentanyl a huge issue

Federal officials said that both fentanyl and methamphetamine are contributing to rising numbers of fatalities.

“Drug cartels in Mexico are mass-producing fentanyl and methamphetamine largely sourced from chemicals in China and they are distributing these substances throughout the United States,” Anne Milgram, administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration, said on the call.

Ms. Milgram said the agency had seized 12,000 pounds of fentanyl in 2021, enough to provide every American with a lethal dose. Fentanyl is also mixed in with cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and marijuana – often in counterfeit pills, Ms. Milgram said.

The DEA and other law enforcement agencies have seized more than 14 million such pills in 2021. “These types of pills are easily accessible today on social media and e-commerce platforms, Ms. Milgram said.

“Drug dealers are now in our homes,” she said. “Wherever there is a smart phone or a computer, a dealer is one click away,” Ms. Milgram said.

National Institute on Drug Abuse Director Nora D. Volkow, MD, said that dealers will continue to push both fentanyl and methamphetamine because they are among the most addictive substances. They also are more profitable because they don’t require cultivation and harvesting, she said on the call.

Dr. Volkow also noted that naloxone is not as effective in reversing fentanyl overdoses because fentanyl is more potent than heroin and other opioids, and “it gets into the brain extremely rapidly.”

Ongoing research is aimed at developing a faster delivery mechanism and a longer-lasting formulation to counter overdoses, Dr. Volkow said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a 28.5% increase from the previous year.

Deaths in some states rose even more precipitously. Vermont saw an almost 70% increase, and drug overdose deaths in West Virginia increased by 62%. Many states, including Alabama, California, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Washington, had a 45%-50% rise in overdose deaths.

The data released by the CDC was provisional, as there is generally a lag between a reported overdose and confirmation of the death to the National Vital Statistics System. The agency uses statistical models that render the counts almost 100% accurate, the CDC says.

The vast majority (73,757) of overdose deaths involved opioids – with most of those (62,338) involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Federal officials said that one American died every 5 minutes from an overdose, or 265 a day.

“We have to acknowledge what this is – it is a crisis,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra told reporters on a call.

“As much as the numbers speak so vividly, they don’t tell the whole story. We see it in the faces of grieving families and all those overworked caregivers. You hear it every time you get that panicked 911 phone call, you read it in obituaries of sons and daughters who left us way too soon,” Mr. Becerra said.

Rahul Gupta, MD, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said that “this is unacceptable, and it requires an unprecedented response.”

Dr. Gupta, who noted that he has a waiver to treat substance use disorder patients with buprenorphine, said he’s seen “first-hand the heartbreak of the overdose epidemic,” adding that, with 23 years in practice, “I’ve learned that an overdose is a cry for help and for far too many people that cry goes unanswered.”

Both Mr. Becerra and Dr. Gupta called on Congress to pass President Joe Biden’s fiscal 2022 budget request, noting that it calls for $41 billion – a $669 million increase from fiscal year 2021 – to go to agencies working on drug interdiction and substance use prevention, treatment, and recovery support.

Dr. Gupta also announced that the administration was releasing a model law that could be used by state legislatures to help standardize policies on making the overdose antidote naloxone more accessible. Currently, such policies are a patchwork across the nation.

In addition, the federal government is newly supporting harm reduction, Mr. Becerra said. This means federal money can be used by clinics and outreach programs to buy fentanyl test strips, which they can then distribute to drug users.

“It’s important for Americans to have the ability to make sure that they can test for fentanyl in the substance,” Dr. Gupta said.

Fake pills, fentanyl a huge issue

Federal officials said that both fentanyl and methamphetamine are contributing to rising numbers of fatalities.

“Drug cartels in Mexico are mass-producing fentanyl and methamphetamine largely sourced from chemicals in China and they are distributing these substances throughout the United States,” Anne Milgram, administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration, said on the call.

Ms. Milgram said the agency had seized 12,000 pounds of fentanyl in 2021, enough to provide every American with a lethal dose. Fentanyl is also mixed in with cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and marijuana – often in counterfeit pills, Ms. Milgram said.

The DEA and other law enforcement agencies have seized more than 14 million such pills in 2021. “These types of pills are easily accessible today on social media and e-commerce platforms, Ms. Milgram said.

“Drug dealers are now in our homes,” she said. “Wherever there is a smart phone or a computer, a dealer is one click away,” Ms. Milgram said.

National Institute on Drug Abuse Director Nora D. Volkow, MD, said that dealers will continue to push both fentanyl and methamphetamine because they are among the most addictive substances. They also are more profitable because they don’t require cultivation and harvesting, she said on the call.

Dr. Volkow also noted that naloxone is not as effective in reversing fentanyl overdoses because fentanyl is more potent than heroin and other opioids, and “it gets into the brain extremely rapidly.”

Ongoing research is aimed at developing a faster delivery mechanism and a longer-lasting formulation to counter overdoses, Dr. Volkow said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

a 28.5% increase from the previous year.

Deaths in some states rose even more precipitously. Vermont saw an almost 70% increase, and drug overdose deaths in West Virginia increased by 62%. Many states, including Alabama, California, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Washington, had a 45%-50% rise in overdose deaths.

The data released by the CDC was provisional, as there is generally a lag between a reported overdose and confirmation of the death to the National Vital Statistics System. The agency uses statistical models that render the counts almost 100% accurate, the CDC says.

The vast majority (73,757) of overdose deaths involved opioids – with most of those (62,338) involving synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. Federal officials said that one American died every 5 minutes from an overdose, or 265 a day.

“We have to acknowledge what this is – it is a crisis,” Department of Health & Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra told reporters on a call.

“As much as the numbers speak so vividly, they don’t tell the whole story. We see it in the faces of grieving families and all those overworked caregivers. You hear it every time you get that panicked 911 phone call, you read it in obituaries of sons and daughters who left us way too soon,” Mr. Becerra said.

Rahul Gupta, MD, director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, said that “this is unacceptable, and it requires an unprecedented response.”

Dr. Gupta, who noted that he has a waiver to treat substance use disorder patients with buprenorphine, said he’s seen “first-hand the heartbreak of the overdose epidemic,” adding that, with 23 years in practice, “I’ve learned that an overdose is a cry for help and for far too many people that cry goes unanswered.”

Both Mr. Becerra and Dr. Gupta called on Congress to pass President Joe Biden’s fiscal 2022 budget request, noting that it calls for $41 billion – a $669 million increase from fiscal year 2021 – to go to agencies working on drug interdiction and substance use prevention, treatment, and recovery support.

Dr. Gupta also announced that the administration was releasing a model law that could be used by state legislatures to help standardize policies on making the overdose antidote naloxone more accessible. Currently, such policies are a patchwork across the nation.

In addition, the federal government is newly supporting harm reduction, Mr. Becerra said. This means federal money can be used by clinics and outreach programs to buy fentanyl test strips, which they can then distribute to drug users.

“It’s important for Americans to have the ability to make sure that they can test for fentanyl in the substance,” Dr. Gupta said.

Fake pills, fentanyl a huge issue

Federal officials said that both fentanyl and methamphetamine are contributing to rising numbers of fatalities.

“Drug cartels in Mexico are mass-producing fentanyl and methamphetamine largely sourced from chemicals in China and they are distributing these substances throughout the United States,” Anne Milgram, administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration, said on the call.

Ms. Milgram said the agency had seized 12,000 pounds of fentanyl in 2021, enough to provide every American with a lethal dose. Fentanyl is also mixed in with cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine, and marijuana – often in counterfeit pills, Ms. Milgram said.

The DEA and other law enforcement agencies have seized more than 14 million such pills in 2021. “These types of pills are easily accessible today on social media and e-commerce platforms, Ms. Milgram said.

“Drug dealers are now in our homes,” she said. “Wherever there is a smart phone or a computer, a dealer is one click away,” Ms. Milgram said.

National Institute on Drug Abuse Director Nora D. Volkow, MD, said that dealers will continue to push both fentanyl and methamphetamine because they are among the most addictive substances. They also are more profitable because they don’t require cultivation and harvesting, she said on the call.

Dr. Volkow also noted that naloxone is not as effective in reversing fentanyl overdoses because fentanyl is more potent than heroin and other opioids, and “it gets into the brain extremely rapidly.”

Ongoing research is aimed at developing a faster delivery mechanism and a longer-lasting formulation to counter overdoses, Dr. Volkow said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Which injections are effective for lateral epicondylitis?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Neither corticosteroids nor platelet-rich plasma are superior to placebo

A 2014 systematic review of RCTs of nonsurgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis identified 4 studies comparing corticosteroid injections to saline or anesthetic injections.1 In the first study, investigators followed 64 patients for 6 months. Both groups significantly improved from baseline, but there were no differences in pain or function at 1 or 6 months. Skin discoloration occurred in 2 patients who received lidocaine injection and 1 who received dexamethasone.2

In a second RCT of patients with symptoms for > 4 weeks, 39 participants were randomized to either betamethasone/bupivacaine or bupivacaine-only injections. In-person follow-up occurred at 4 and 8 weeks and telephone follow-up at 6 months. Both groups statistically improved from baseline to 6 months. No differences were seen between groups in pain or functional improvement at 4, 8, or 26 weeks, but the betamethasone group showed statistically greater improvement on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) from 8 weeks to the final 6-month telephone follow-up. No functional assessments were reported at 6 months.3

The third RCT of 165 patients with lateral epicondylitis for > 6 weeks evaluated 4 intervention groups: corticosteroid injection with/without physiotherapy and placebo (small-volume saline) injection with/without physiotherapy. At the end of 1 year, the corticosteroid injection groups had less complete recovery (83% vs 96%; relative risk [RR] = 0.86; 99% CI, 0.75-0.99) and more recurrences (54% vs 12%; RR = 0.23; 99% CI, 0.10-0.51) than the placebo groups.4

The fourth RCT randomized 120 patients to either 2 mL lidocaine or 1 mL lidocaine plus 1 mL of triamcinolone. At 1-year follow-up, 57 of 60 lidocaine-injected patients had an excellent recovery and 56 of 60 triamcinolone plus lidocaine patients had an excellent recovery.5

Platelet-rich plasma. A meta-analysis6 of RCTs of PRP vs saline injections included 5 trials and 276 patients with a mean age of 48 years; duration of follow-up was 2 to 12 months. No significant differences were found between the groups for pain score—measured by VAS or the Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE)—(standardized mean difference [SMD] = –0.51; 95% CI, –1.32 to –0.30) nor for functional score (SMD = 0.07; 95% CI, –0.46 to 0.33). Two of the trials reported adverse reactions of pain around the injection site: 16% to 20% in the PRP group vs 8% to 15% in the saline group.

Corticosteroids and PRP. A 2013 3-armed RCT7 (n = 60) compared 1-time injections of PRP, corticosteroid, and saline for treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Pain was evaluated at 1 and 3 months using the PRTEE. Compared to saline, corticosteroid showed a statistically significant, but not a minimum clinically important, reduction (8% greater improvement) at 1 month but not at 3 months. PRP pain reduction at both 1 and 3 months was not significantly different from placebo. Importantly, a small sample size combined with a high dropout rate (> 70%) limit validity of this study.

Botulinum toxin shows modest pain improvement, but …

A 2017 meta-analysis8 of 4 RCTs (n = 278) compared the effectiveness of botulinum toxin vs saline injection and other nonsurgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis. The studies compared the mean differences in pain relief and hand grip strength in adult patients with lateral epicondylitis symptoms for at least 3 months. Compared with saline injection, botulinum toxin injection significantly reduced pain to a small or medium SMD, at 2 to 4 weeks post injection (SMD = –0.73; 95% CI, –1.29 to –0.17); 8 to 12 weeks post injection (SMD = –0.45; 95% CI, –0.74 to –0.15); and 16+ weeks post injection (SMD = –0.54; 95% CI, –0.98 to –0.11). Harm from botulinum toxin was greater than from saline or corticosteroid, with a significant reduction in grip strength at 2 to 4 weeks (SMD = –0.33; 95% CI, –0.59 to –0.08).

Continue to: Prolotherapy needs further study

Prolotherapy needs further study

A 2008 RCT9 of 20 adults with at least 6 months of lateral epicondylitis received either prolotherapy (1 part 5% sodium morrhuate, 1.5 parts 50% dextrose, 0.5 parts 4% lidocaine, 0.5 parts 0.5% bupivacaine HCl, and 3.5 parts normal saline) injections or 0.9% saline injections at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks. On a 10-point Likert scale, the prolotherapy group had a lower mean pain score at 16 weeks than the saline injection group (0.5 vs 3.5), but not at 8 weeks (3.3 vs 3.6). This pilot study’s results are limited by its small sample size.

Hyaluronic acid improves pain, but not enough

A 2010 double-blind RCT10 (n = 331) compared hyaluronic acid injection vs saline injection in treatment of lateral epicondylitis in adults with > 3 months of symptoms. Two injections were performed 1 week apart, with follow-up at 30 days and at 1 year after the first injection. VAS score in the hyaluronic acid group, at rest and after grip testing, was significantly different (statistically) than in the placebo group but did not meet criteria for minimum clinically important improvement. Review of the literature showed limited follow-up studies on hyaluronic acid for lateral epicondylitis to confirm this RCT.

Autologous blood has no advantage over placebo

The only RCT of autologous blood compared to saline injections11 included patients with lateral epicondylitis for < 6 months: 10 saline injections vs 9 autologous blood injections. Patient scores on the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand scale (which measures symptoms from 0 to 100; lower is better) showed no difference but favored the saline injections at 2-month (28 vs 20) and 6-month (20 vs 10) follow-up.

Editor’s takeaway

Limiting the evidence review to studies with a placebo comparator clarifies the lack of effectiveness of lateral epicondylitis injections. Neither corticosteroid, platelet-rich plasma, botulinum toxin, prolotherapy, hyaluronic acid, or autologous blood injections have proven superior to saline or anesthetic injections. However, all injections that contained “placebo” significantly improved lateralepicondylitis.

1. Sims S, Miller K, Elfar J, et al. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9:419-446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x

2. Lindenhovius A, Henket M, Gilligan BP, et al. Injection of dexamethasone versus placebo for lateral elbow pain: a prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:909-919. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.02.004

3. Newcomer KL, Laskowski ER, Idank DM, et al. Corticosteroid injection in early treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:214-222. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200110000-00002

4. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Brooks P, et al. Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:461-469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.129

5. Altay T, Gunal I, Ozturk H. Local injection treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;398:127-130.

6. Simental-Mendía M, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Álvarez-Villalobos N, et al. Clinical efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2255-2265. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05000-y

7. Krogh T, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich-plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:625-635. doi:10.1177/0363546512472975

8. Lin Y, Wu W, Hsu Y, et al. Comparative effectiveness of botulinum toxin versus non-surgical treatments for treating lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;32:131-145. doi:10.1177/0269215517702517

9. Scarpone M, Rabago DP, Zgierska A, et al. The efficacy of prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis: a pilot study. Clin J Sports Med. 2008;18:248-254. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318170fc87

10. Petrella R, Cogliano A, Decaria J, et al. Management of tennis elbow with sodium hyaluronate periarticular injections. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-2-4

11. Wolf JM, Ozer K, Scott F, et al. Comparison of autologous blood, corticosteroid, and saline injection in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1269-1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.05.014

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Neither corticosteroids nor platelet-rich plasma are superior to placebo

A 2014 systematic review of RCTs of nonsurgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis identified 4 studies comparing corticosteroid injections to saline or anesthetic injections.1 In the first study, investigators followed 64 patients for 6 months. Both groups significantly improved from baseline, but there were no differences in pain or function at 1 or 6 months. Skin discoloration occurred in 2 patients who received lidocaine injection and 1 who received dexamethasone.2

In a second RCT of patients with symptoms for > 4 weeks, 39 participants were randomized to either betamethasone/bupivacaine or bupivacaine-only injections. In-person follow-up occurred at 4 and 8 weeks and telephone follow-up at 6 months. Both groups statistically improved from baseline to 6 months. No differences were seen between groups in pain or functional improvement at 4, 8, or 26 weeks, but the betamethasone group showed statistically greater improvement on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) from 8 weeks to the final 6-month telephone follow-up. No functional assessments were reported at 6 months.3

The third RCT of 165 patients with lateral epicondylitis for > 6 weeks evaluated 4 intervention groups: corticosteroid injection with/without physiotherapy and placebo (small-volume saline) injection with/without physiotherapy. At the end of 1 year, the corticosteroid injection groups had less complete recovery (83% vs 96%; relative risk [RR] = 0.86; 99% CI, 0.75-0.99) and more recurrences (54% vs 12%; RR = 0.23; 99% CI, 0.10-0.51) than the placebo groups.4

The fourth RCT randomized 120 patients to either 2 mL lidocaine or 1 mL lidocaine plus 1 mL of triamcinolone. At 1-year follow-up, 57 of 60 lidocaine-injected patients had an excellent recovery and 56 of 60 triamcinolone plus lidocaine patients had an excellent recovery.5

Platelet-rich plasma. A meta-analysis6 of RCTs of PRP vs saline injections included 5 trials and 276 patients with a mean age of 48 years; duration of follow-up was 2 to 12 months. No significant differences were found between the groups for pain score—measured by VAS or the Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE)—(standardized mean difference [SMD] = –0.51; 95% CI, –1.32 to –0.30) nor for functional score (SMD = 0.07; 95% CI, –0.46 to 0.33). Two of the trials reported adverse reactions of pain around the injection site: 16% to 20% in the PRP group vs 8% to 15% in the saline group.

Corticosteroids and PRP. A 2013 3-armed RCT7 (n = 60) compared 1-time injections of PRP, corticosteroid, and saline for treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Pain was evaluated at 1 and 3 months using the PRTEE. Compared to saline, corticosteroid showed a statistically significant, but not a minimum clinically important, reduction (8% greater improvement) at 1 month but not at 3 months. PRP pain reduction at both 1 and 3 months was not significantly different from placebo. Importantly, a small sample size combined with a high dropout rate (> 70%) limit validity of this study.

Botulinum toxin shows modest pain improvement, but …

A 2017 meta-analysis8 of 4 RCTs (n = 278) compared the effectiveness of botulinum toxin vs saline injection and other nonsurgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis. The studies compared the mean differences in pain relief and hand grip strength in adult patients with lateral epicondylitis symptoms for at least 3 months. Compared with saline injection, botulinum toxin injection significantly reduced pain to a small or medium SMD, at 2 to 4 weeks post injection (SMD = –0.73; 95% CI, –1.29 to –0.17); 8 to 12 weeks post injection (SMD = –0.45; 95% CI, –0.74 to –0.15); and 16+ weeks post injection (SMD = –0.54; 95% CI, –0.98 to –0.11). Harm from botulinum toxin was greater than from saline or corticosteroid, with a significant reduction in grip strength at 2 to 4 weeks (SMD = –0.33; 95% CI, –0.59 to –0.08).

Continue to: Prolotherapy needs further study

Prolotherapy needs further study

A 2008 RCT9 of 20 adults with at least 6 months of lateral epicondylitis received either prolotherapy (1 part 5% sodium morrhuate, 1.5 parts 50% dextrose, 0.5 parts 4% lidocaine, 0.5 parts 0.5% bupivacaine HCl, and 3.5 parts normal saline) injections or 0.9% saline injections at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks. On a 10-point Likert scale, the prolotherapy group had a lower mean pain score at 16 weeks than the saline injection group (0.5 vs 3.5), but not at 8 weeks (3.3 vs 3.6). This pilot study’s results are limited by its small sample size.

Hyaluronic acid improves pain, but not enough

A 2010 double-blind RCT10 (n = 331) compared hyaluronic acid injection vs saline injection in treatment of lateral epicondylitis in adults with > 3 months of symptoms. Two injections were performed 1 week apart, with follow-up at 30 days and at 1 year after the first injection. VAS score in the hyaluronic acid group, at rest and after grip testing, was significantly different (statistically) than in the placebo group but did not meet criteria for minimum clinically important improvement. Review of the literature showed limited follow-up studies on hyaluronic acid for lateral epicondylitis to confirm this RCT.

Autologous blood has no advantage over placebo

The only RCT of autologous blood compared to saline injections11 included patients with lateral epicondylitis for < 6 months: 10 saline injections vs 9 autologous blood injections. Patient scores on the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand scale (which measures symptoms from 0 to 100; lower is better) showed no difference but favored the saline injections at 2-month (28 vs 20) and 6-month (20 vs 10) follow-up.

Editor’s takeaway

Limiting the evidence review to studies with a placebo comparator clarifies the lack of effectiveness of lateral epicondylitis injections. Neither corticosteroid, platelet-rich plasma, botulinum toxin, prolotherapy, hyaluronic acid, or autologous blood injections have proven superior to saline or anesthetic injections. However, all injections that contained “placebo” significantly improved lateralepicondylitis.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Neither corticosteroids nor platelet-rich plasma are superior to placebo

A 2014 systematic review of RCTs of nonsurgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis identified 4 studies comparing corticosteroid injections to saline or anesthetic injections.1 In the first study, investigators followed 64 patients for 6 months. Both groups significantly improved from baseline, but there were no differences in pain or function at 1 or 6 months. Skin discoloration occurred in 2 patients who received lidocaine injection and 1 who received dexamethasone.2

In a second RCT of patients with symptoms for > 4 weeks, 39 participants were randomized to either betamethasone/bupivacaine or bupivacaine-only injections. In-person follow-up occurred at 4 and 8 weeks and telephone follow-up at 6 months. Both groups statistically improved from baseline to 6 months. No differences were seen between groups in pain or functional improvement at 4, 8, or 26 weeks, but the betamethasone group showed statistically greater improvement on the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) from 8 weeks to the final 6-month telephone follow-up. No functional assessments were reported at 6 months.3

The third RCT of 165 patients with lateral epicondylitis for > 6 weeks evaluated 4 intervention groups: corticosteroid injection with/without physiotherapy and placebo (small-volume saline) injection with/without physiotherapy. At the end of 1 year, the corticosteroid injection groups had less complete recovery (83% vs 96%; relative risk [RR] = 0.86; 99% CI, 0.75-0.99) and more recurrences (54% vs 12%; RR = 0.23; 99% CI, 0.10-0.51) than the placebo groups.4

The fourth RCT randomized 120 patients to either 2 mL lidocaine or 1 mL lidocaine plus 1 mL of triamcinolone. At 1-year follow-up, 57 of 60 lidocaine-injected patients had an excellent recovery and 56 of 60 triamcinolone plus lidocaine patients had an excellent recovery.5

Platelet-rich plasma. A meta-analysis6 of RCTs of PRP vs saline injections included 5 trials and 276 patients with a mean age of 48 years; duration of follow-up was 2 to 12 months. No significant differences were found between the groups for pain score—measured by VAS or the Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE)—(standardized mean difference [SMD] = –0.51; 95% CI, –1.32 to –0.30) nor for functional score (SMD = 0.07; 95% CI, –0.46 to 0.33). Two of the trials reported adverse reactions of pain around the injection site: 16% to 20% in the PRP group vs 8% to 15% in the saline group.

Corticosteroids and PRP. A 2013 3-armed RCT7 (n = 60) compared 1-time injections of PRP, corticosteroid, and saline for treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Pain was evaluated at 1 and 3 months using the PRTEE. Compared to saline, corticosteroid showed a statistically significant, but not a minimum clinically important, reduction (8% greater improvement) at 1 month but not at 3 months. PRP pain reduction at both 1 and 3 months was not significantly different from placebo. Importantly, a small sample size combined with a high dropout rate (> 70%) limit validity of this study.

Botulinum toxin shows modest pain improvement, but …

A 2017 meta-analysis8 of 4 RCTs (n = 278) compared the effectiveness of botulinum toxin vs saline injection and other nonsurgical treatments for lateral epicondylitis. The studies compared the mean differences in pain relief and hand grip strength in adult patients with lateral epicondylitis symptoms for at least 3 months. Compared with saline injection, botulinum toxin injection significantly reduced pain to a small or medium SMD, at 2 to 4 weeks post injection (SMD = –0.73; 95% CI, –1.29 to –0.17); 8 to 12 weeks post injection (SMD = –0.45; 95% CI, –0.74 to –0.15); and 16+ weeks post injection (SMD = –0.54; 95% CI, –0.98 to –0.11). Harm from botulinum toxin was greater than from saline or corticosteroid, with a significant reduction in grip strength at 2 to 4 weeks (SMD = –0.33; 95% CI, –0.59 to –0.08).

Continue to: Prolotherapy needs further study

Prolotherapy needs further study

A 2008 RCT9 of 20 adults with at least 6 months of lateral epicondylitis received either prolotherapy (1 part 5% sodium morrhuate, 1.5 parts 50% dextrose, 0.5 parts 4% lidocaine, 0.5 parts 0.5% bupivacaine HCl, and 3.5 parts normal saline) injections or 0.9% saline injections at baseline, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks. On a 10-point Likert scale, the prolotherapy group had a lower mean pain score at 16 weeks than the saline injection group (0.5 vs 3.5), but not at 8 weeks (3.3 vs 3.6). This pilot study’s results are limited by its small sample size.

Hyaluronic acid improves pain, but not enough

A 2010 double-blind RCT10 (n = 331) compared hyaluronic acid injection vs saline injection in treatment of lateral epicondylitis in adults with > 3 months of symptoms. Two injections were performed 1 week apart, with follow-up at 30 days and at 1 year after the first injection. VAS score in the hyaluronic acid group, at rest and after grip testing, was significantly different (statistically) than in the placebo group but did not meet criteria for minimum clinically important improvement. Review of the literature showed limited follow-up studies on hyaluronic acid for lateral epicondylitis to confirm this RCT.

Autologous blood has no advantage over placebo

The only RCT of autologous blood compared to saline injections11 included patients with lateral epicondylitis for < 6 months: 10 saline injections vs 9 autologous blood injections. Patient scores on the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand scale (which measures symptoms from 0 to 100; lower is better) showed no difference but favored the saline injections at 2-month (28 vs 20) and 6-month (20 vs 10) follow-up.

Editor’s takeaway

Limiting the evidence review to studies with a placebo comparator clarifies the lack of effectiveness of lateral epicondylitis injections. Neither corticosteroid, platelet-rich plasma, botulinum toxin, prolotherapy, hyaluronic acid, or autologous blood injections have proven superior to saline or anesthetic injections. However, all injections that contained “placebo” significantly improved lateralepicondylitis.

1. Sims S, Miller K, Elfar J, et al. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9:419-446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x

2. Lindenhovius A, Henket M, Gilligan BP, et al. Injection of dexamethasone versus placebo for lateral elbow pain: a prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:909-919. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.02.004

3. Newcomer KL, Laskowski ER, Idank DM, et al. Corticosteroid injection in early treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:214-222. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200110000-00002

4. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Brooks P, et al. Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:461-469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.129

5. Altay T, Gunal I, Ozturk H. Local injection treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;398:127-130.

6. Simental-Mendía M, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Álvarez-Villalobos N, et al. Clinical efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2255-2265. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05000-y

7. Krogh T, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich-plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:625-635. doi:10.1177/0363546512472975

8. Lin Y, Wu W, Hsu Y, et al. Comparative effectiveness of botulinum toxin versus non-surgical treatments for treating lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;32:131-145. doi:10.1177/0269215517702517

9. Scarpone M, Rabago DP, Zgierska A, et al. The efficacy of prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis: a pilot study. Clin J Sports Med. 2008;18:248-254. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318170fc87

10. Petrella R, Cogliano A, Decaria J, et al. Management of tennis elbow with sodium hyaluronate periarticular injections. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-2-4

11. Wolf JM, Ozer K, Scott F, et al. Comparison of autologous blood, corticosteroid, and saline injection in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1269-1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.05.014

1. Sims S, Miller K, Elfar J, et al. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9:419-446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x

2. Lindenhovius A, Henket M, Gilligan BP, et al. Injection of dexamethasone versus placebo for lateral elbow pain: a prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:909-919. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.02.004

3. Newcomer KL, Laskowski ER, Idank DM, et al. Corticosteroid injection in early treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:214-222. doi: 10.1097/00042752-200110000-00002

4. Coombes BK, Bisset L, Brooks P, et al. Effect of corticosteroid injection, physiotherapy, or both on clinical outcomes in patients with unilateral lateral epicondylalgia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309:461-469. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.129

5. Altay T, Gunal I, Ozturk H. Local injection treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;398:127-130.

6. Simental-Mendía M, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Álvarez-Villalobos N, et al. Clinical efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2255-2265. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05000-y

7. Krogh T, Fredberg U, Stengaard-Pedersen K, et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with platelet-rich-plasma, glucocorticoid, or saline: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41:625-635. doi:10.1177/0363546512472975

8. Lin Y, Wu W, Hsu Y, et al. Comparative effectiveness of botulinum toxin versus non-surgical treatments for treating lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2017;32:131-145. doi:10.1177/0269215517702517

9. Scarpone M, Rabago DP, Zgierska A, et al. The efficacy of prolotherapy for lateral epicondylosis: a pilot study. Clin J Sports Med. 2008;18:248-254. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318170fc87

10. Petrella R, Cogliano A, Decaria J, et al. Management of tennis elbow with sodium hyaluronate periarticular injections. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2010;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-2-4

11. Wolf JM, Ozer K, Scott F, et al. Comparison of autologous blood, corticosteroid, and saline injection in the treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1269-1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.05.014

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Placebo injections actually improve lateral epicondylitis at high rates. No other injections convincingly improve it better than placebo.

Corticosteroid injection is not superior to saline or anesthetic injection (strength of recommendation [SOR] A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injection is not superior to saline injection (SOR A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Botulinum toxin injection, compared to saline injection, modestly improved pain in lateral epicondylitis, but with short-term grip-strength weakness (SOR A, meta-analysis of RCTs). Prolotherapy injection, compared to saline injection, improved pain at 16-week, but not at 8-week, follow-up (SOR B, one small pilot RCT).

Hyaluronic acid injection, compared to saline injection, resulted in a statistically significant pain reduction (6%) but did not achieve the minimum clinically important difference (SOR B, single RCT). Autologous blood injection, compared to saline injection, did not improve disability ratings (SOR B, one small RCT).

When the evidence suggests that placebo is best

In this issue of JFP, the Clinical Inquiry seeks to answer the question: What are effective injection treatments for lateral epicondylitis? Answering this question proved to be a daunting task for the authors. The difficulty lies in answering this question: effective compared to what?

The injections evaluated in their comprehensive review—corticosteroids, botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma,

There are 2 choices for an ideal comparison group. One choice compares the active intervention to an adequate placebo, the other compares it to another treatment that has previously been proven effective. Ideally, the other treatment would be a “gold standard”—that is, the best treatment currently available. Unfortunately, for treatment of lateral epicondylitis, no gold standard has been established.

So, what is an “adequate placebo” for injection therapy? This is a very difficult question. The placebo should probably include putting a needle into the treatment site and injecting a nonactive substance, such as saline solution. This is the comparison group Vukelic et al chose for their review. But even saline could theoretically be therapeutic.

Another fair comparison for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis would be an injection near, but not at, the lateral epicondyle. Yet another comparison—dry needling without any medication to the lateral epicondyle vs dry needling of an adjacent location—would also be a fair comparison to help understand the effect of needling alone. Unfortunately, these comparisons have not been explored in randomized controlled trials. Although several studies have evaluated dry needling for lateral epicondylitis,2-4 none have used a fair comparison.

Some studies1 evaluating treatments for lateral epicondylitis used comparisons to agents that are ineffective or of uncertain effectiveness. Comparing 1 agent to another ineffective or potentially harmful agent obscures our knowledge. Evidence-based medicine must be built on a reliable foundation.

Vukelic and colleagues did an admirable job of selecting studies with an appropriate comparison group—that is, saline injection, the best comparator that has been studied. What they discovered is that no type of injection therapy has been proven to be better than a saline injection.

So, if your patient is not satisfied with conservative therapy for epicondylitis and wants an injection, salt water seems as good as anything.

1. Sims S, Miller K, Elfar J, et al. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9:419-446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x

2. Uygur E, Aktas B, Ozkut A, et al. Dry needling in lateral epicondylitis: a prospective controlled study. Int Orthop. 2017; 41:2321-2325. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3604-1

3. Krey D, Borchers J, McCamey K. Tendon needling for treatment of tendinopathy: A systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:80-86. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1004296

4. Jayaseelan DJ, Faller BT, Avery MH. The utilization and effects of filiform dry needling in the management of tendinopathy: a systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. Published online April 27, 2021. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1920076

In this issue of JFP, the Clinical Inquiry seeks to answer the question: What are effective injection treatments for lateral epicondylitis? Answering this question proved to be a daunting task for the authors. The difficulty lies in answering this question: effective compared to what?

The injections evaluated in their comprehensive review—corticosteroids, botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma,

There are 2 choices for an ideal comparison group. One choice compares the active intervention to an adequate placebo, the other compares it to another treatment that has previously been proven effective. Ideally, the other treatment would be a “gold standard”—that is, the best treatment currently available. Unfortunately, for treatment of lateral epicondylitis, no gold standard has been established.

So, what is an “adequate placebo” for injection therapy? This is a very difficult question. The placebo should probably include putting a needle into the treatment site and injecting a nonactive substance, such as saline solution. This is the comparison group Vukelic et al chose for their review. But even saline could theoretically be therapeutic.

Another fair comparison for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis would be an injection near, but not at, the lateral epicondyle. Yet another comparison—dry needling without any medication to the lateral epicondyle vs dry needling of an adjacent location—would also be a fair comparison to help understand the effect of needling alone. Unfortunately, these comparisons have not been explored in randomized controlled trials. Although several studies have evaluated dry needling for lateral epicondylitis,2-4 none have used a fair comparison.

Some studies1 evaluating treatments for lateral epicondylitis used comparisons to agents that are ineffective or of uncertain effectiveness. Comparing 1 agent to another ineffective or potentially harmful agent obscures our knowledge. Evidence-based medicine must be built on a reliable foundation.

Vukelic and colleagues did an admirable job of selecting studies with an appropriate comparison group—that is, saline injection, the best comparator that has been studied. What they discovered is that no type of injection therapy has been proven to be better than a saline injection.

So, if your patient is not satisfied with conservative therapy for epicondylitis and wants an injection, salt water seems as good as anything.

In this issue of JFP, the Clinical Inquiry seeks to answer the question: What are effective injection treatments for lateral epicondylitis? Answering this question proved to be a daunting task for the authors. The difficulty lies in answering this question: effective compared to what?

The injections evaluated in their comprehensive review—corticosteroids, botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acid, platelet-rich plasma,

There are 2 choices for an ideal comparison group. One choice compares the active intervention to an adequate placebo, the other compares it to another treatment that has previously been proven effective. Ideally, the other treatment would be a “gold standard”—that is, the best treatment currently available. Unfortunately, for treatment of lateral epicondylitis, no gold standard has been established.

So, what is an “adequate placebo” for injection therapy? This is a very difficult question. The placebo should probably include putting a needle into the treatment site and injecting a nonactive substance, such as saline solution. This is the comparison group Vukelic et al chose for their review. But even saline could theoretically be therapeutic.

Another fair comparison for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis would be an injection near, but not at, the lateral epicondyle. Yet another comparison—dry needling without any medication to the lateral epicondyle vs dry needling of an adjacent location—would also be a fair comparison to help understand the effect of needling alone. Unfortunately, these comparisons have not been explored in randomized controlled trials. Although several studies have evaluated dry needling for lateral epicondylitis,2-4 none have used a fair comparison.

Some studies1 evaluating treatments for lateral epicondylitis used comparisons to agents that are ineffective or of uncertain effectiveness. Comparing 1 agent to another ineffective or potentially harmful agent obscures our knowledge. Evidence-based medicine must be built on a reliable foundation.

Vukelic and colleagues did an admirable job of selecting studies with an appropriate comparison group—that is, saline injection, the best comparator that has been studied. What they discovered is that no type of injection therapy has been proven to be better than a saline injection.

So, if your patient is not satisfied with conservative therapy for epicondylitis and wants an injection, salt water seems as good as anything.

1. Sims S, Miller K, Elfar J, et al. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9:419-446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x

2. Uygur E, Aktas B, Ozkut A, et al. Dry needling in lateral epicondylitis: a prospective controlled study. Int Orthop. 2017; 41:2321-2325. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3604-1

3. Krey D, Borchers J, McCamey K. Tendon needling for treatment of tendinopathy: A systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:80-86. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1004296

4. Jayaseelan DJ, Faller BT, Avery MH. The utilization and effects of filiform dry needling in the management of tendinopathy: a systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. Published online April 27, 2021. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1920076

1. Sims S, Miller K, Elfar J, et al. Non-surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Hand (NY). 2014;9:419-446. doi: 10.1007/s11552-014-9642-x

2. Uygur E, Aktas B, Ozkut A, et al. Dry needling in lateral epicondylitis: a prospective controlled study. Int Orthop. 2017; 41:2321-2325. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3604-1

3. Krey D, Borchers J, McCamey K. Tendon needling for treatment of tendinopathy: A systematic review. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:80-86. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2015.1004296

4. Jayaseelan DJ, Faller BT, Avery MH. The utilization and effects of filiform dry needling in the management of tendinopathy: a systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. Published online April 27, 2021. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.1920076

Botulinum toxin for chronic pain: What's on the horizon?

Botulinum toxin (BoNT) was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of strabismus and blepharospasm in 1989. Since then, approved indications have expanded to include spasticity, cervical dystonia, severe axillary hyperhidrosis, bladder dysfunction, and chronic migraine headache, as well as multiple cosmetic uses.1,2 Over the course of 30 years of clinical use, BoNT has proven to be effective and safe.3,4 This has led to the expanded use of BoNT for additional medical conditions.1,2

In the review that follows, we will discuss the utility of BoNT in the treatment of headaches, spasticity, and cervical dystonia. We will then explore the evidence for emerging indications that include chronic joint pain, trigeminal neuralgia, and plantar fasciitis. But first, a brief word about how BoNT works and its safety profile.

Seven toxins, but only 2 are used for medical purposes

BoNT is naturally produced by Clostridium botulinum, an anaerobic, spore-forming bacteria.1 BoNT inhibits acetylcholine release from presynaptic vesicles at the neuromuscular junctions, which results in flaccid paralysis in peripheral skeletal musculature and autonomic nerve terminals.1,5 These effects from BoNT can last up to 3 to 6 months.1

Seven different toxins have been identified (A, B, C, D, E, F, and G), but only toxins A and B are currently used for medical purposes.5 Both have similar effects, although there are slight differences in mechanism of action. Toxin B injections are also reported to be slightly more painful. There are also differences in preparation, with some requiring reconstitution, which vary by brand. Certain types of BoNT require refrigeration, and an in-depth review of the manufacturer’s guidelines is recommended before use.

Safety and adverse effects

Although BoNT is 1 of the most lethal toxins known to humans, it has been used in clinical medicine for more than 30 years and has proven to be safe if used properly.3 Adverse effects are rare and are often location and dose dependent (200 U and higher). Immediate or acute adverse effects are usually mild and can include bruising, headache, allergic reactions, edema, skin conditions, infection, or pain at the injection site.4 Delayed adverse effects can include muscle weakness that persists throughout the 3 to 6 months of duration and is usually related to incorrect placement or unintentional spread.4

Serious adverse events are rare: there are reports of the development of botulism, generalized paralysis, dysphagia, respiratory effects, and even death in patients who had received BoNT injections.3 In a majority of cases, a direct relationship with BoNT was never established, and in most incidents reported, there were significant comorbidities that could have contributed to the adverse event.3 These events appear to be related to higher doses of BoNT, as well as possible incorrect injection placement.3

Knowledge of anatomy and correct placement of BoNT are vitally important, as they have a significant impact on the effectiveness of treatment and adverse events.3 In preventing adverse events, those administering BoNT need to be familiar with the BoNT brand being used, verify proper storage consistent with the manufacturer’s recommendations, and confirm correct dosages with proper reconstitution process.3

Continue to: BoNT is contraindicated

BoNT is contraindicated in those with a history of a previous anaphylactic reaction to BoNT. Patients with known hypersensitivity to BoNT, including those with neuromuscular junction diseases and anterior horn disorders, should be considered for other forms of treatment due to the risk of an exaggerated response. No adverse events have been recorded in regard to pregnancy and lactation, although these remain a potential contraindication.3,4,6

Taking a closer look at current indications

Headaches

Chronic migraine (CM) is defined by the International Headache Society as at least 15 days per month with headaches and 8 of those days with migraine features. BoNT has been FDA approved for treatment of CM since 2011. This was based on 2 large, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials that showed a significant reduction from baseline for headaches and migraine days, total time, and frequency of migraines.7,8

Subsequent studies have continued to show benefit for CM treatment. In a recent Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis, it was determined that BoNT can decrease frequency of CM by 2 days per month, and it is recommended by several organizations as a treatment option for CM.9

Low-quality evidence has not shown benefit for tension-type headaches. However, further research is warranted, especially for chronic tension-type headache, which is defined as daily tension headaches.10

Spasticity

Spasticity is caused by an insult to the brain or spinal cord and can often occur after a stroke, brain or spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, or other neurologic condition.11 BoNT was initially FDA approved in 2010 for treatment of upper limb spasticity in adults, although it had been used for treatment for spasticity for more than 20 years prior to that. It currently is approved for upper and lower spasticity in adults and recently was expanded to include pediatrics.12

Continue to: A small case series...

A small case series conducted soon after BoNT was introduced showed promising results, and subsequent meta-analyses and systematic reviews have shown positive results for use of BoNT for the management of spasticity.13 Studies have begun to focus on specific regions of the upper and lower limbs to identify optimal sites for injections.

Cervical dystonia

Cervical dystonia (CD) is the most common form of dystonia and is defined as impairment of activities of daily living due to abnormal postures of the head and neck. BoNT was approved for CD in 1999 after several pivotal randomized placebo-controlled double-blind studies showed improvement of symptoms.14 Several BoNT formulations have been given Level A classification, and can be considered a potential first-line treatment for CD.15,16 The most common adverse effects reported have been dry mouth, dysphagia, muscle weakness, and neck pain.14-16

BoNT is currently being used off-label for management of multiple types of dystonia with reported success, as research on its use for noncervical dystonia (including limb, laryngeal, oromandibular, and truncal) continues. Although there are case series and some randomized trials exploring BoNT for certain types of dystonia, most are lacking high-quality evidence from double-blind, randomized controlled trials.14-16

Exploring the evidence for emerging indications

There has been significant interest in using BoNT for management for both nociceptive and neuropathic pain symptoms.5

Nociceptive pain is the irritation and painful response to actual or potential tissue damage. It is a major component of chronic pain and is difficult to treat, with limited effective options.5,17

Continue to: Neuropathic pain

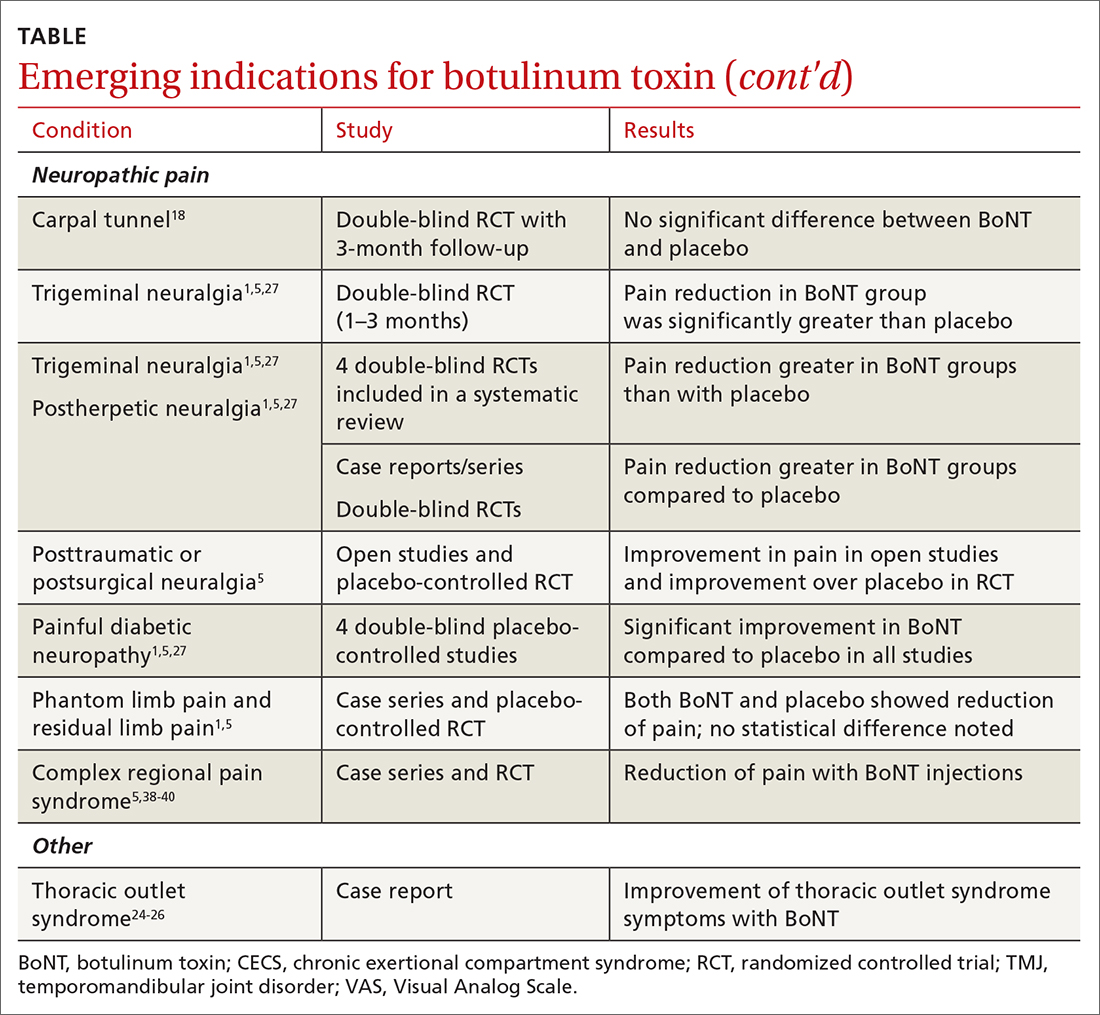

Neuropathic pain is related to abnormalities that disrupt the normal function of the nervous system. Abnormalities could be related to anatomic or structural changes that cause compression, trauma, scar tissue, or a number of other conditions that affect nerve function. These can be either central or peripheral and can be caused by multiple etiologies.

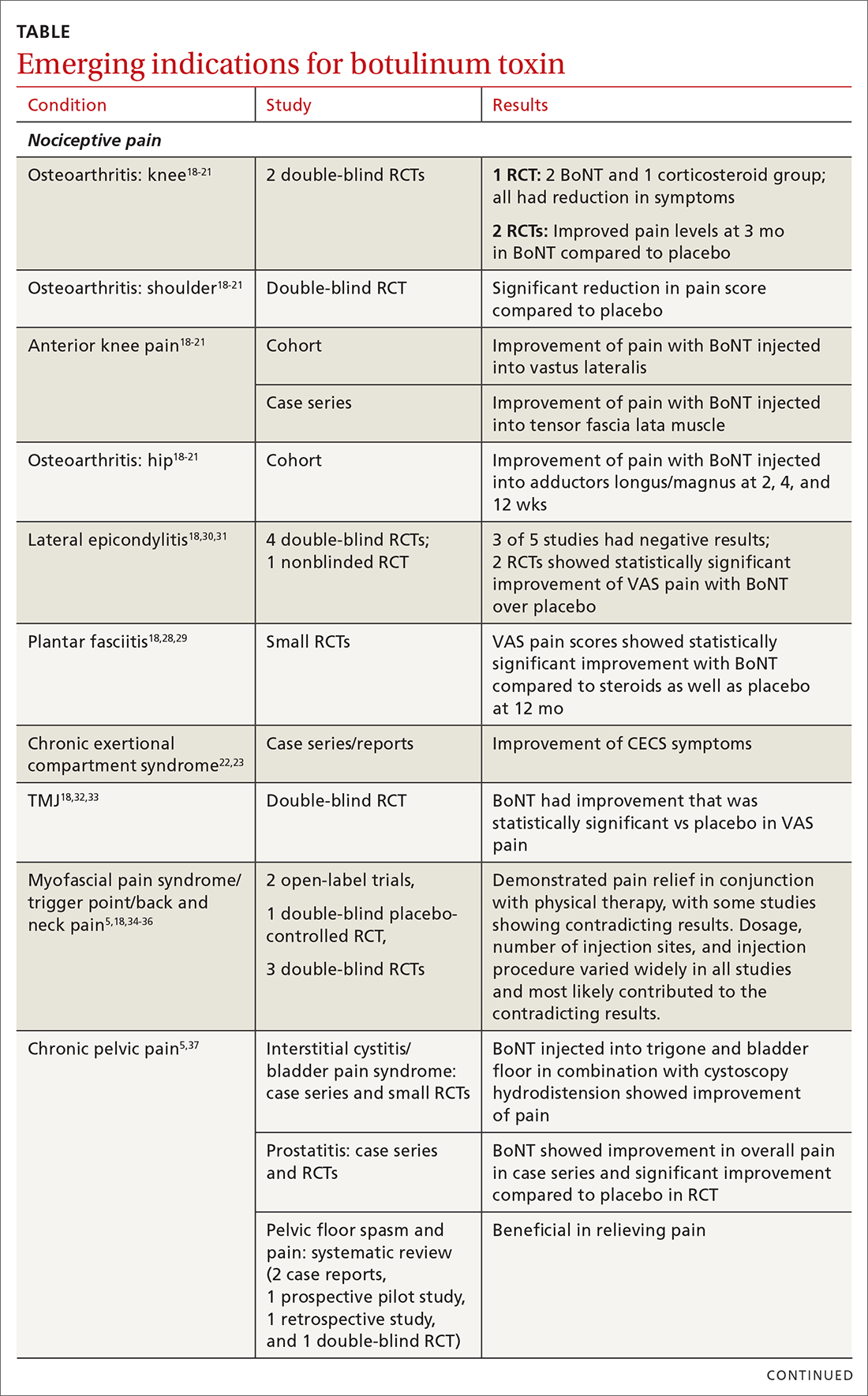

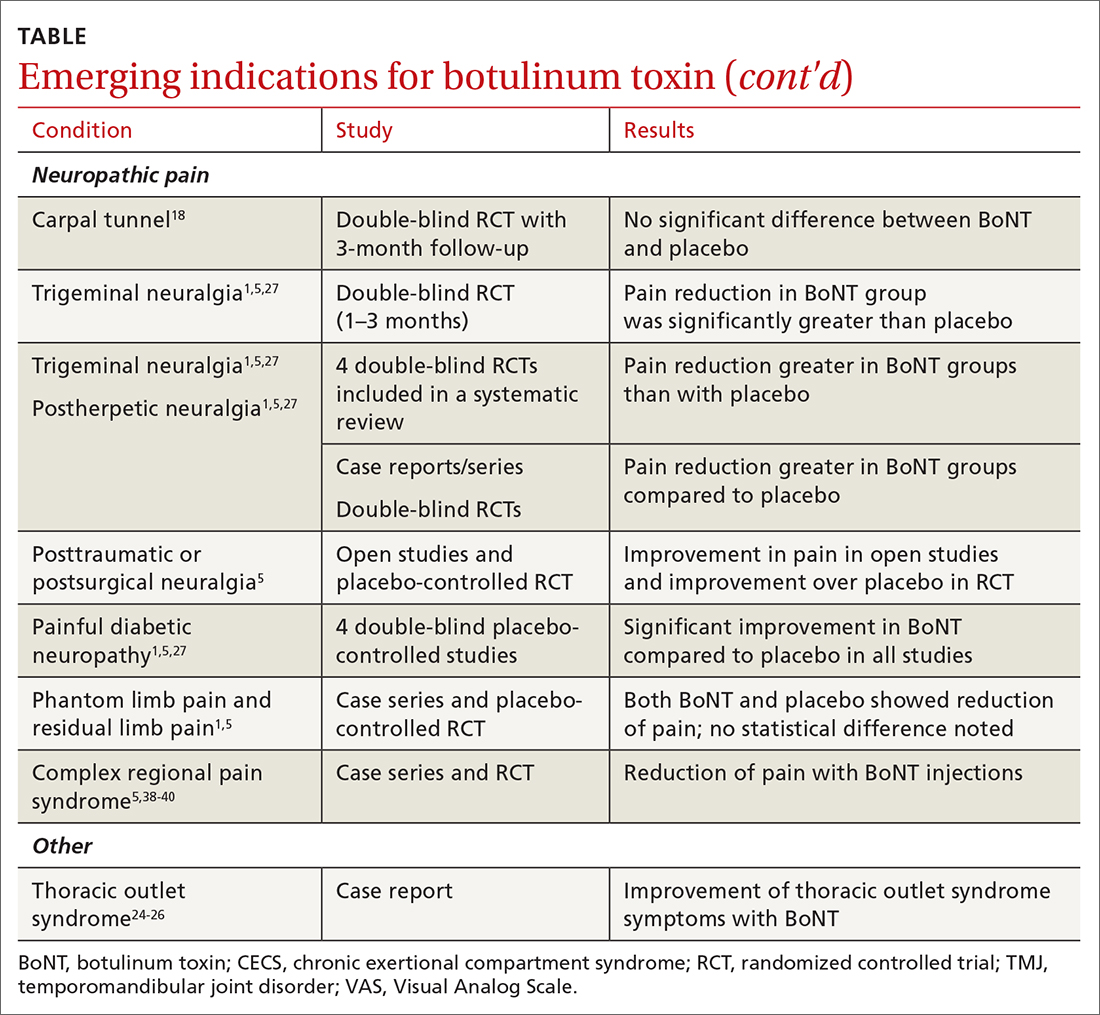

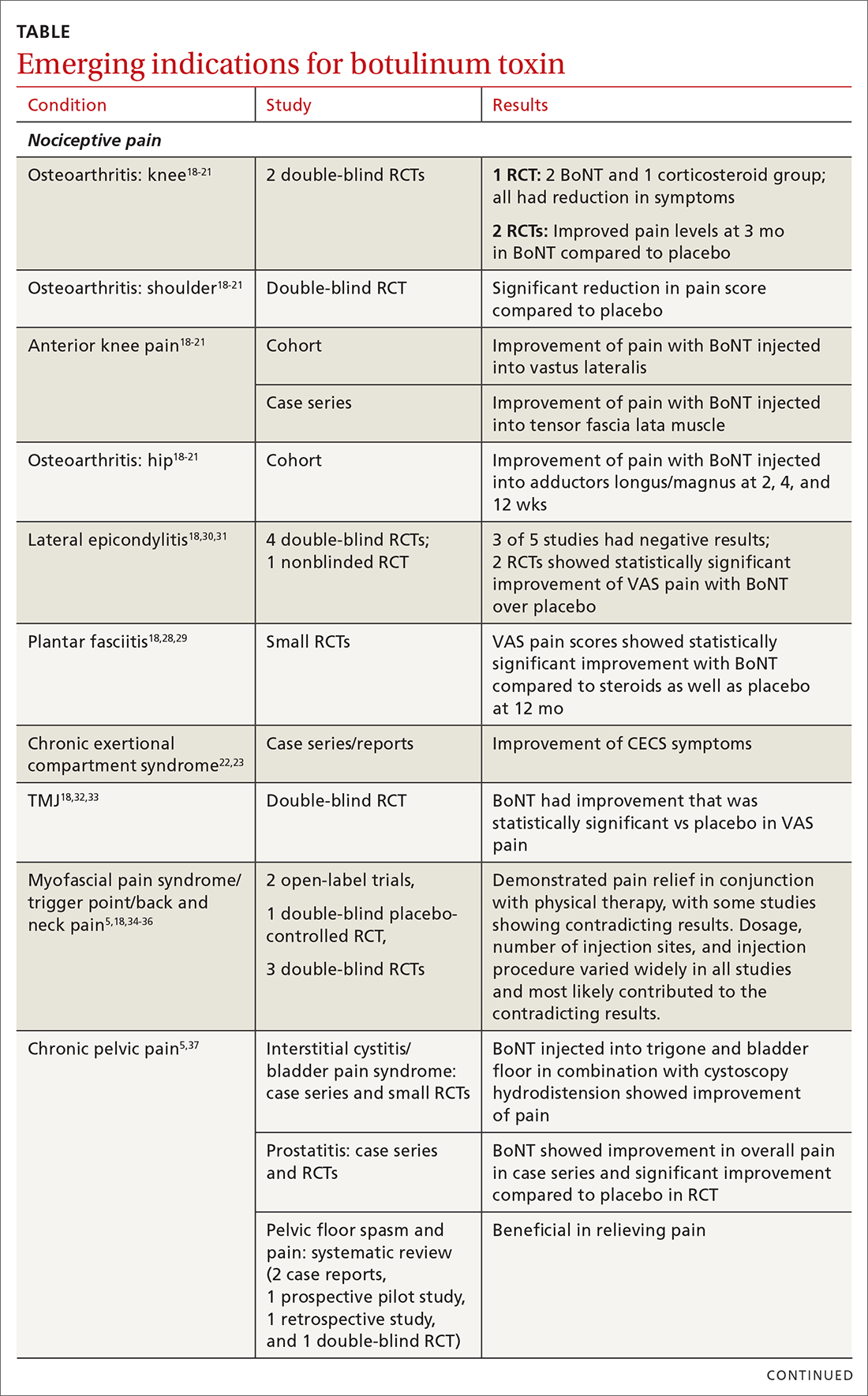

The following discussion explores the evidence for potential emerging indications for BoNT. The TABLE1,5,18-40 summarizes what we know to date.

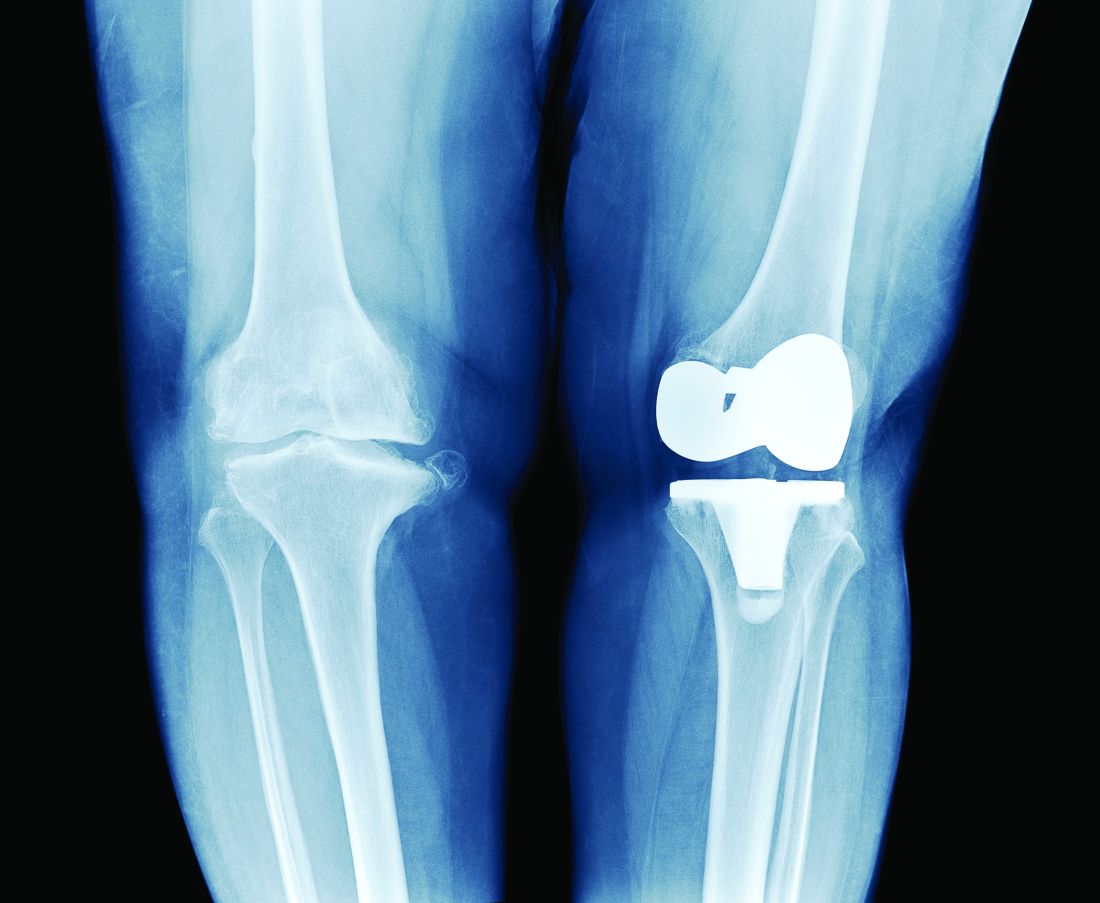

Chronic joint pain

Refractory joint pain is difficult to treat and can be debilitating for patients. It can have multiple causes but is most commonly related to arthritic changes. Due to the difficulty with treatment, there have been attempts to use BoNT as an intra-articular treatment for refractory joint pain. Results vary and are related to several factors, including the initial degree of pain, the BoNT dosage, and the formulation used, as well as the joint injected.

There appears to be a potentially significant improvement in short-term pain with BoNT compared to conventional therapies, such as physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and hyaluronic acid injections. In studies evaluating long-term benefits, it was noted that after 6 months, there was no significant difference between BoNT and control groups.19-21

The knee joint has been the focus of most research, but BoNT has also been used for shoulder and ankle pain, with success. Recent meta-analyses evaluating knee and shoulder pain have shown BoNT is safe and effective for joint pain.20,21 There has been no significant difference noted in adverse events with BoNT compared to controls. Currently, more long-term data and research are needed, but BoNT is safe and a potentially effective treatment option for short-term relief of refractory joint pain.19-21

Continue to: Chronic exertional compartment sydrome

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) is defined subjectively as pain in a specific compartment that develops during exercise and resolves upon stopping, as well as objectively with an increase in intra-muscular pressure.22 It is most common in the lower leg and is a difficult condition to manage. Nonsurgical and surgical options are only successful at returning the patient to full activity 40% to 80% of the time.23

An initial study done in 2013 of BoNT injected into the anterior and lateral compartments of the lower extremity showed that symptoms resolved completely in 94% of patients treated.22 The actual mechanism of benefit is not clearly understood but is potentially related to muscle atrophy and loss of contractile tissue. However, it has not been reported that these changes have affected the strength or performance of patients who receive BoNT for CECS.23

Thoracic outlet syndrome

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is a compression of neurovascular structures within the thoracic outlet. There are several locations of potential compression, as well as possible neurogenic, vascular, or nonspecific manifestations.24 Compression can be from a structural variant, such as a cervical rib, or due to soft tissue from the scalene or pectoralis musculature. TOS is difficult to diagnose and treat. Physical therapy is the mainstay of treatment, but failure is common and treatment options are otherwise limited. Decompression surgery is an option if conservative management fails, but it has a high recurrence rate.24