User login

HBV screening often incomplete or forgone when starting tocilizumab, tofacitinib

People beginning treatment with the immunosuppressive drugs tocilizumab (Actemra) or tofacitinib (Xeljanz) are infrequently screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, according to a new study of patients with rheumatic diseases who are starting one of the two treatments.

“Perhaps not unexpectedly, these screening patterns conform more with recommendations from the American College of Rheumatology, which do not explicitly stipulate universal HBV screening,” wrote lead author Amir M. Mohareb, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The study was published in The Journal of Rheumatology.

To determine the frequency of HBV screening among this specific population, the researchers conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study of patients 18 years or older within the Mass General Brigham health system in the Boston area who initiated either of the two drugs before Dec. 31, 2018. Tocilizumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration on Jan. 11, 2010, and tofacitinib was approved on Nov. 6, 2012.

The final study population included 678 patients on tocilizumab and 391 patients on tofacitinib. The mean age of the patients in each group was 61 years for tocilizumab and 60 years for tofacitinib. A large majority were female (78% of the tocilizumab group, 88% of the tofacitinib group) and 84% of patients in both groups were white. Their primary diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis (53% of the tocilizumab group, 77% of the tofacitinib group), and most of them – 57% of patients on tocilizumab and 72% of patients on tofacitinib – had a history of being on both conventional synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

HBV screening patterns were classified into three categories: complete (all three of the HBV surface antigen [HBsAg], total core antibody [anti-HBcAb], and surface antibody [HBsAb] tests); partial (any one to two tests); and none. Of the 678 patients on tocilizumab, 194 (29%) underwent complete screening, 307 (45%) underwent partial screening, and 177 (26%) had no screening. Of the 391 patients on tofacitinib, 94 (24%) underwent complete screening, 195 (50%) underwent partial screening, and 102 (26%) had none.

Inappropriate testing – defined as either HBV e-antigen (HBeAg), anti-HBcAb IgM, or HBV DNA without a positive HBsAg or total anti-HBcAb – occurred in 22% of patients on tocilizumab and 23% of patients on tofacitinib. After multivariable analysis, the authors found that Whites were less likely to undergo complete screening (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.95) compared to non-Whites. Previous use of immunosuppressive agents such as conventional synthetic DMARDs (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.72-1.55) and biologic DMARDs with or without prior csDMARDs (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48-1.12) was not associated with a likelihood of complete appropriate screening.

“These data add to the evidence indicating that clinicians are not completing pretreatment screening for latent infections prior to patients starting high-risk immunosuppressant drugs,” Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “It can be dangerous, since a fraction of these patients may reactivate latent infections with HBV that can result in liver failure or death.

“On the bright side,” she added, “we have antivirals that can be given as prophylaxis against reactivation of latent HBV if patients do test positive.”

Dr. Schmajuk was previously the senior author of a similar study from the 2019 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting that found only a small percentage of patients who were new users of biologics or new synthetic DMARDs were screened for HBV or hepatitis C virus.

When asked if anything in the study stood out, she acknowledged being “somewhat surprised that patients with prior immunosuppression did not have higher rates of screening. One might expect that since those patients had more opportunities for screening – since they started new medications more times – they would have higher rates, but this did not appear to be the case.”

As a message to rheumatologists who may be starting their patients on any biologic or new synthetic DMARD, she reinforced that “we need universal HBV screening for patients starting these medications. Many clinicians are used to ordering a hepatitis B surface antigen test, but one key message is that we also need to be ordering hepatitis B core antibody tests. Patients with a positive core antibody are still at risk for reactivation.”

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including the data being retrospectively collected and some of the subjects potentially being screened in laboratories outside of the Mass General Brigham health system. In addition, they stated that their findings “may not be generalizable to nonrheumatologic settings or other immunomodulators,” although they added that studies of other patient populations have also uncovered “similarly low HBV screening frequencies.”

Several of the authors reported being supported by institutes within the National Institutes of Health. Beyond that, they declared no potential conflicts of interest.

People beginning treatment with the immunosuppressive drugs tocilizumab (Actemra) or tofacitinib (Xeljanz) are infrequently screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, according to a new study of patients with rheumatic diseases who are starting one of the two treatments.

“Perhaps not unexpectedly, these screening patterns conform more with recommendations from the American College of Rheumatology, which do not explicitly stipulate universal HBV screening,” wrote lead author Amir M. Mohareb, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The study was published in The Journal of Rheumatology.

To determine the frequency of HBV screening among this specific population, the researchers conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study of patients 18 years or older within the Mass General Brigham health system in the Boston area who initiated either of the two drugs before Dec. 31, 2018. Tocilizumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration on Jan. 11, 2010, and tofacitinib was approved on Nov. 6, 2012.

The final study population included 678 patients on tocilizumab and 391 patients on tofacitinib. The mean age of the patients in each group was 61 years for tocilizumab and 60 years for tofacitinib. A large majority were female (78% of the tocilizumab group, 88% of the tofacitinib group) and 84% of patients in both groups were white. Their primary diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis (53% of the tocilizumab group, 77% of the tofacitinib group), and most of them – 57% of patients on tocilizumab and 72% of patients on tofacitinib – had a history of being on both conventional synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

HBV screening patterns were classified into three categories: complete (all three of the HBV surface antigen [HBsAg], total core antibody [anti-HBcAb], and surface antibody [HBsAb] tests); partial (any one to two tests); and none. Of the 678 patients on tocilizumab, 194 (29%) underwent complete screening, 307 (45%) underwent partial screening, and 177 (26%) had no screening. Of the 391 patients on tofacitinib, 94 (24%) underwent complete screening, 195 (50%) underwent partial screening, and 102 (26%) had none.

Inappropriate testing – defined as either HBV e-antigen (HBeAg), anti-HBcAb IgM, or HBV DNA without a positive HBsAg or total anti-HBcAb – occurred in 22% of patients on tocilizumab and 23% of patients on tofacitinib. After multivariable analysis, the authors found that Whites were less likely to undergo complete screening (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.95) compared to non-Whites. Previous use of immunosuppressive agents such as conventional synthetic DMARDs (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.72-1.55) and biologic DMARDs with or without prior csDMARDs (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48-1.12) was not associated with a likelihood of complete appropriate screening.

“These data add to the evidence indicating that clinicians are not completing pretreatment screening for latent infections prior to patients starting high-risk immunosuppressant drugs,” Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “It can be dangerous, since a fraction of these patients may reactivate latent infections with HBV that can result in liver failure or death.

“On the bright side,” she added, “we have antivirals that can be given as prophylaxis against reactivation of latent HBV if patients do test positive.”

Dr. Schmajuk was previously the senior author of a similar study from the 2019 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting that found only a small percentage of patients who were new users of biologics or new synthetic DMARDs were screened for HBV or hepatitis C virus.

When asked if anything in the study stood out, she acknowledged being “somewhat surprised that patients with prior immunosuppression did not have higher rates of screening. One might expect that since those patients had more opportunities for screening – since they started new medications more times – they would have higher rates, but this did not appear to be the case.”

As a message to rheumatologists who may be starting their patients on any biologic or new synthetic DMARD, she reinforced that “we need universal HBV screening for patients starting these medications. Many clinicians are used to ordering a hepatitis B surface antigen test, but one key message is that we also need to be ordering hepatitis B core antibody tests. Patients with a positive core antibody are still at risk for reactivation.”

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including the data being retrospectively collected and some of the subjects potentially being screened in laboratories outside of the Mass General Brigham health system. In addition, they stated that their findings “may not be generalizable to nonrheumatologic settings or other immunomodulators,” although they added that studies of other patient populations have also uncovered “similarly low HBV screening frequencies.”

Several of the authors reported being supported by institutes within the National Institutes of Health. Beyond that, they declared no potential conflicts of interest.

People beginning treatment with the immunosuppressive drugs tocilizumab (Actemra) or tofacitinib (Xeljanz) are infrequently screened for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, according to a new study of patients with rheumatic diseases who are starting one of the two treatments.

“Perhaps not unexpectedly, these screening patterns conform more with recommendations from the American College of Rheumatology, which do not explicitly stipulate universal HBV screening,” wrote lead author Amir M. Mohareb, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. The study was published in The Journal of Rheumatology.

To determine the frequency of HBV screening among this specific population, the researchers conducted a retrospective, cross-sectional study of patients 18 years or older within the Mass General Brigham health system in the Boston area who initiated either of the two drugs before Dec. 31, 2018. Tocilizumab was approved by the Food and Drug Administration on Jan. 11, 2010, and tofacitinib was approved on Nov. 6, 2012.

The final study population included 678 patients on tocilizumab and 391 patients on tofacitinib. The mean age of the patients in each group was 61 years for tocilizumab and 60 years for tofacitinib. A large majority were female (78% of the tocilizumab group, 88% of the tofacitinib group) and 84% of patients in both groups were white. Their primary diagnosis was rheumatoid arthritis (53% of the tocilizumab group, 77% of the tofacitinib group), and most of them – 57% of patients on tocilizumab and 72% of patients on tofacitinib – had a history of being on both conventional synthetic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

HBV screening patterns were classified into three categories: complete (all three of the HBV surface antigen [HBsAg], total core antibody [anti-HBcAb], and surface antibody [HBsAb] tests); partial (any one to two tests); and none. Of the 678 patients on tocilizumab, 194 (29%) underwent complete screening, 307 (45%) underwent partial screening, and 177 (26%) had no screening. Of the 391 patients on tofacitinib, 94 (24%) underwent complete screening, 195 (50%) underwent partial screening, and 102 (26%) had none.

Inappropriate testing – defined as either HBV e-antigen (HBeAg), anti-HBcAb IgM, or HBV DNA without a positive HBsAg or total anti-HBcAb – occurred in 22% of patients on tocilizumab and 23% of patients on tofacitinib. After multivariable analysis, the authors found that Whites were less likely to undergo complete screening (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% confidence interval, 0.57-0.95) compared to non-Whites. Previous use of immunosuppressive agents such as conventional synthetic DMARDs (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.72-1.55) and biologic DMARDs with or without prior csDMARDs (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.48-1.12) was not associated with a likelihood of complete appropriate screening.

“These data add to the evidence indicating that clinicians are not completing pretreatment screening for latent infections prior to patients starting high-risk immunosuppressant drugs,” Gabriela Schmajuk, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, said in an interview. “It can be dangerous, since a fraction of these patients may reactivate latent infections with HBV that can result in liver failure or death.

“On the bright side,” she added, “we have antivirals that can be given as prophylaxis against reactivation of latent HBV if patients do test positive.”

Dr. Schmajuk was previously the senior author of a similar study from the 2019 American College of Rheumatology annual meeting that found only a small percentage of patients who were new users of biologics or new synthetic DMARDs were screened for HBV or hepatitis C virus.

When asked if anything in the study stood out, she acknowledged being “somewhat surprised that patients with prior immunosuppression did not have higher rates of screening. One might expect that since those patients had more opportunities for screening – since they started new medications more times – they would have higher rates, but this did not appear to be the case.”

As a message to rheumatologists who may be starting their patients on any biologic or new synthetic DMARD, she reinforced that “we need universal HBV screening for patients starting these medications. Many clinicians are used to ordering a hepatitis B surface antigen test, but one key message is that we also need to be ordering hepatitis B core antibody tests. Patients with a positive core antibody are still at risk for reactivation.”

The authors noted their study’s limitations, including the data being retrospectively collected and some of the subjects potentially being screened in laboratories outside of the Mass General Brigham health system. In addition, they stated that their findings “may not be generalizable to nonrheumatologic settings or other immunomodulators,” although they added that studies of other patient populations have also uncovered “similarly low HBV screening frequencies.”

Several of the authors reported being supported by institutes within the National Institutes of Health. Beyond that, they declared no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF RHEUMATOLOGY

Rashes in Pregnancy

Rashes that develop during pregnancy often result in considerable anxiety or concern for patients and their families. Recognizing these pregnancy-specific dermatoses is important in identifying fetal risks as well as providing appropriate management and expert guidance for patients regarding future pregnancies. Managing cutaneous manifestations of pregnancy-related disorders is challenging and requires knowledge of potential side effects of therapy for both the mother and fetus. It also is important to appreciate the physiologic cutaneous changes of pregnancy along with their clinical significance and management.

In 2006, Ambrose-Rudolph et al1 proposed reclassification of pregnancy-specific dermatoses, which has since been widely accepted by the academic dermatology community. The 4 most prominent disorders include intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP); pemphigoid gestationis (PG); polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy; and atopic eruption of pregnancy.2 It is important to recognize these pregnancy-specific disorders and to understand their clinical significance. The morphology of the eruption as well as the location and timing of the onset of the rash are important clues in making an accurate diagnosis.3

Clinical Presentation

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents with severe generalized pruritus, usually with involvement of the palms and soles, in the late second or third trimester. Pemphigoid gestationis presents with urticarial papules and/or bullae, often in the second or third trimester or postpartum. An important diagnostic clue for PG is involvement near the umbilicus. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy presents with urticarial papules and plaques; onset occurs in the third trimester or postpartum and initially involves the striae while sparing the umbilicus, unlike in PG. Atopic eruption of pregnancy has an earlier onset than the other pregnancy-specific dermatoses, often in the first or second trimester, and presents with widespread eczematous lesions.3

Diagnosis

The pregnancy dermatoses with the greatest potential for fetal risks are ICP and PG; therefore, it is critical for health care providers to diagnose these dermatoses in a timely manner and initiate appropriate management. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is confirmed by elevated serum bile acids (ie, >10 µmol/L), often during the third trimester. The risk of fetal morbidity is high in ICP with increased bile acids crossing the placenta causing placental anoxia and impaired cardiomyocyte function.4 Fetal risks, including preterm delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and stillbirth, correlate with the level of bile acids in the serum.5 Maternal prognosis is favorable, but there is an increased association with hepatitis C and hepatobiliary disease.6

Diagnosis of PG is confirmed by classic biopsy results and direct immunofluorescence revealing C3 with or without IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane zone. Additionally, complement indirect immunofluorescence reveals circulating IgG anti–basement membrane zone antibodies. Pemphigoid gestationis is associated with increased fetal risks of preterm labor and intrauterine growth retardation.7 Clinical findings of PG may present in the fetus upon delivery due to transmission of autoantibodies across the placenta. The symptoms usually are mild.8 An increased risk of Graves disease has been reported in mothers with PG.

In most cases, diagnosis of PEP is based on history and morphology, but if the presentation is not classic, skin biopsy must be used to differentiate it from PG as well as more common dermatologic conditions such as contact dermatitis, drug and viral eruptions, and urticaria.

Atopic eruption of pregnancy manifests as widespread eczematous excoriated papules and plaques. Lesions of prurigo nodularis are common.

Comorbidities

It is important to be aware of specific clinical associations related to pregnancy-specific dermatoses. Pemphigoid gestationis has been associated with gestational trophoblastic tumors including hydatiform mole and choriocarcinoma.4 An increased risk for Graves disease has been reported in patients with PG.9 Patients who develop ICP have a higher incidence of hepatitis C, postpartum cholecystitis, gallstones, and nonalcoholic cirrhosis.8 Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy is associated with a notably higher incidence in multiple gestation pregnancies.2

Treatment and Management

Management of ICP requires an accurate and timely diagnosis, and advanced neonatal-obstetric management is critical.3 Ursodeoxycholic acid is the treatment of choice and reduces pruritus, prolongs pregnancy, and reduces fetal risk.4 Most stillbirths cluster at the 38th week of pregnancy, and patients with ICP and highly elevated serum bile acids (>40 µmol/L) should be considered for delivery at 37 weeks or earlier.5

Management of the other cutaneous disorders of pregnancy can be challenging for health care providers based on safety concerns for the fetus. Although it is important to minimize risks to the fetus, it also is important to adequately treat the mother’s cutaneous disease, which requires a solid knowledge of drug safety during pregnancy. The former US Food and Drug Administration classification system using A, B, C, D, and X pregnancy categories was replaced by the Pregnancy Lactation Label Final Rule, which provides counseling on medication safety during pregnancy.10 In 2014, Murase et al11 published a review of dermatologic medication safety during pregnancy, which serves as an excellent guide.

Before instituting treatment, the therapeutic plan should be discussed with the physician managing the patient’s pregnancy. In general, topical steroids are considered safe during pregnancy, and low-potency to moderate-potency topical steroids are preferred. If possible, use of topical steroids should be limited to less than 300 g for the duration of the pregnancy. Fluticasone propionate should be avoided during pregnancy because it is not metabolized by the placenta. When systemic steroids are considered appropriate for management during pregnancy, nonhalogenated corticosteroids such as prednisone and prednisolone are preferred because they are enzymatically inactivated by the placenta, which results in a favorable maternal-fetal gradient.12 There has been concern expressed in the medical literature that systemic steroids during the first trimester may increase the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate.3,12 When managing pregnancy dermatoses, consideration should be given to keep prednisone exposure below 20 mg/d, and try to limit prolonged use to 7.5 mg/d. However, this may not be possible in PG.3 Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be appropriate when patients are on prolonged systemic steroids to control disease.

Antihistamines can be used to control pruritus complicating pregnancy-associated dermatoses. First-generation antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine and diphenhydramine are preferred due to long-term safety data.3,11,12 Loratadine is the first choice and cetirizine is the second choice if a second-generation antihistamine is preferred.3 Loratadine is preferred during breastfeeding due to less sedation.12 High-dose antihistamines prior to delivery may cause concerns for potential side effects in the newborn, including tremulousness, irritability, and poor feeding.

Recurrence

Women with pregnancy dermatoses often are concerned about recurrence with future pregnancies. Pemphigoid gestationis may flare with subsequent pregnancies, subsequent menses, or with oral contraceptive use.3 Recurrence of PEP in subsequent pregnancies is rare and usually is less severe than the primary eruption.8 Often, the rare recurrent eruption of PEP is associated with multigestational pregnancies.2 Mothers can anticipate a recurrence of ICP in up to 60% to 70% of future pregnancies. Patients with AEP have an underlying atopic diathesis, and recurrence in future pregnancies is not uncommon.8

Final Thoughts

In summary, it is important for health care providers to recognize the specific cutaneous disorders of pregnancy and their potential fetal complications. The anatomical location of onset of the dermatosis and timing of onset during pregnancy can give important clues. Appropriate management, especially with ICP, can minimize fetal complications. A fundamental knowledge of medication safety and management during pregnancy is essential. Rashes during pregnancy can cause anxiety in the mother and family and require support, comfort, and guidance.

- Ambrose-Rudolph CM, Müllegger RR, Vaughn-Jones SA, et al. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:395-404.

- Bechtel M, Plotner A. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58:104-111.

- Bechtel M. Pruritus in pregnancy and its management. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:259-265.

- Ambrose-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy—clues to diagnosis, fetal risk, and therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:265-275.

- Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-controlled study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482-1491.

- Bergman H, Melamed N, Koven G. Pruritus in pregnancy: treatment of dermatoses unique to pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:1290-1294.

- Beard MP, Millington GW. Recent developments in the specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:1-14.

- Shears S, Blaszczak A, Kaffenberger J. Pregnancy dermatosis. In: Tyler KH, ed. Cutaneous Disorders of Pregnancy. 1st ed. Springer Nature; 2020:13-39.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2015;26:274-284.

- Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Fed Registr. 2014;79:72064-72103. To be codified at 21 CFR § 201.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part 1. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;401:E1-E14.

- Friedman B, Bercovitch L. Atopic dermatitis in pregnancy. In: Tyler KH, ed. Cutaneous Disorders of Pregnancy. Springer Nature; 2020:59-74.

Rashes that develop during pregnancy often result in considerable anxiety or concern for patients and their families. Recognizing these pregnancy-specific dermatoses is important in identifying fetal risks as well as providing appropriate management and expert guidance for patients regarding future pregnancies. Managing cutaneous manifestations of pregnancy-related disorders is challenging and requires knowledge of potential side effects of therapy for both the mother and fetus. It also is important to appreciate the physiologic cutaneous changes of pregnancy along with their clinical significance and management.

In 2006, Ambrose-Rudolph et al1 proposed reclassification of pregnancy-specific dermatoses, which has since been widely accepted by the academic dermatology community. The 4 most prominent disorders include intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP); pemphigoid gestationis (PG); polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy; and atopic eruption of pregnancy.2 It is important to recognize these pregnancy-specific disorders and to understand their clinical significance. The morphology of the eruption as well as the location and timing of the onset of the rash are important clues in making an accurate diagnosis.3

Clinical Presentation

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents with severe generalized pruritus, usually with involvement of the palms and soles, in the late second or third trimester. Pemphigoid gestationis presents with urticarial papules and/or bullae, often in the second or third trimester or postpartum. An important diagnostic clue for PG is involvement near the umbilicus. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy presents with urticarial papules and plaques; onset occurs in the third trimester or postpartum and initially involves the striae while sparing the umbilicus, unlike in PG. Atopic eruption of pregnancy has an earlier onset than the other pregnancy-specific dermatoses, often in the first or second trimester, and presents with widespread eczematous lesions.3

Diagnosis

The pregnancy dermatoses with the greatest potential for fetal risks are ICP and PG; therefore, it is critical for health care providers to diagnose these dermatoses in a timely manner and initiate appropriate management. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is confirmed by elevated serum bile acids (ie, >10 µmol/L), often during the third trimester. The risk of fetal morbidity is high in ICP with increased bile acids crossing the placenta causing placental anoxia and impaired cardiomyocyte function.4 Fetal risks, including preterm delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and stillbirth, correlate with the level of bile acids in the serum.5 Maternal prognosis is favorable, but there is an increased association with hepatitis C and hepatobiliary disease.6

Diagnosis of PG is confirmed by classic biopsy results and direct immunofluorescence revealing C3 with or without IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane zone. Additionally, complement indirect immunofluorescence reveals circulating IgG anti–basement membrane zone antibodies. Pemphigoid gestationis is associated with increased fetal risks of preterm labor and intrauterine growth retardation.7 Clinical findings of PG may present in the fetus upon delivery due to transmission of autoantibodies across the placenta. The symptoms usually are mild.8 An increased risk of Graves disease has been reported in mothers with PG.

In most cases, diagnosis of PEP is based on history and morphology, but if the presentation is not classic, skin biopsy must be used to differentiate it from PG as well as more common dermatologic conditions such as contact dermatitis, drug and viral eruptions, and urticaria.

Atopic eruption of pregnancy manifests as widespread eczematous excoriated papules and plaques. Lesions of prurigo nodularis are common.

Comorbidities

It is important to be aware of specific clinical associations related to pregnancy-specific dermatoses. Pemphigoid gestationis has been associated with gestational trophoblastic tumors including hydatiform mole and choriocarcinoma.4 An increased risk for Graves disease has been reported in patients with PG.9 Patients who develop ICP have a higher incidence of hepatitis C, postpartum cholecystitis, gallstones, and nonalcoholic cirrhosis.8 Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy is associated with a notably higher incidence in multiple gestation pregnancies.2

Treatment and Management

Management of ICP requires an accurate and timely diagnosis, and advanced neonatal-obstetric management is critical.3 Ursodeoxycholic acid is the treatment of choice and reduces pruritus, prolongs pregnancy, and reduces fetal risk.4 Most stillbirths cluster at the 38th week of pregnancy, and patients with ICP and highly elevated serum bile acids (>40 µmol/L) should be considered for delivery at 37 weeks or earlier.5

Management of the other cutaneous disorders of pregnancy can be challenging for health care providers based on safety concerns for the fetus. Although it is important to minimize risks to the fetus, it also is important to adequately treat the mother’s cutaneous disease, which requires a solid knowledge of drug safety during pregnancy. The former US Food and Drug Administration classification system using A, B, C, D, and X pregnancy categories was replaced by the Pregnancy Lactation Label Final Rule, which provides counseling on medication safety during pregnancy.10 In 2014, Murase et al11 published a review of dermatologic medication safety during pregnancy, which serves as an excellent guide.

Before instituting treatment, the therapeutic plan should be discussed with the physician managing the patient’s pregnancy. In general, topical steroids are considered safe during pregnancy, and low-potency to moderate-potency topical steroids are preferred. If possible, use of topical steroids should be limited to less than 300 g for the duration of the pregnancy. Fluticasone propionate should be avoided during pregnancy because it is not metabolized by the placenta. When systemic steroids are considered appropriate for management during pregnancy, nonhalogenated corticosteroids such as prednisone and prednisolone are preferred because they are enzymatically inactivated by the placenta, which results in a favorable maternal-fetal gradient.12 There has been concern expressed in the medical literature that systemic steroids during the first trimester may increase the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate.3,12 When managing pregnancy dermatoses, consideration should be given to keep prednisone exposure below 20 mg/d, and try to limit prolonged use to 7.5 mg/d. However, this may not be possible in PG.3 Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be appropriate when patients are on prolonged systemic steroids to control disease.

Antihistamines can be used to control pruritus complicating pregnancy-associated dermatoses. First-generation antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine and diphenhydramine are preferred due to long-term safety data.3,11,12 Loratadine is the first choice and cetirizine is the second choice if a second-generation antihistamine is preferred.3 Loratadine is preferred during breastfeeding due to less sedation.12 High-dose antihistamines prior to delivery may cause concerns for potential side effects in the newborn, including tremulousness, irritability, and poor feeding.

Recurrence

Women with pregnancy dermatoses often are concerned about recurrence with future pregnancies. Pemphigoid gestationis may flare with subsequent pregnancies, subsequent menses, or with oral contraceptive use.3 Recurrence of PEP in subsequent pregnancies is rare and usually is less severe than the primary eruption.8 Often, the rare recurrent eruption of PEP is associated with multigestational pregnancies.2 Mothers can anticipate a recurrence of ICP in up to 60% to 70% of future pregnancies. Patients with AEP have an underlying atopic diathesis, and recurrence in future pregnancies is not uncommon.8

Final Thoughts

In summary, it is important for health care providers to recognize the specific cutaneous disorders of pregnancy and their potential fetal complications. The anatomical location of onset of the dermatosis and timing of onset during pregnancy can give important clues. Appropriate management, especially with ICP, can minimize fetal complications. A fundamental knowledge of medication safety and management during pregnancy is essential. Rashes during pregnancy can cause anxiety in the mother and family and require support, comfort, and guidance.

Rashes that develop during pregnancy often result in considerable anxiety or concern for patients and their families. Recognizing these pregnancy-specific dermatoses is important in identifying fetal risks as well as providing appropriate management and expert guidance for patients regarding future pregnancies. Managing cutaneous manifestations of pregnancy-related disorders is challenging and requires knowledge of potential side effects of therapy for both the mother and fetus. It also is important to appreciate the physiologic cutaneous changes of pregnancy along with their clinical significance and management.

In 2006, Ambrose-Rudolph et al1 proposed reclassification of pregnancy-specific dermatoses, which has since been widely accepted by the academic dermatology community. The 4 most prominent disorders include intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP); pemphigoid gestationis (PG); polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), also known as pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy; and atopic eruption of pregnancy.2 It is important to recognize these pregnancy-specific disorders and to understand their clinical significance. The morphology of the eruption as well as the location and timing of the onset of the rash are important clues in making an accurate diagnosis.3

Clinical Presentation

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy presents with severe generalized pruritus, usually with involvement of the palms and soles, in the late second or third trimester. Pemphigoid gestationis presents with urticarial papules and/or bullae, often in the second or third trimester or postpartum. An important diagnostic clue for PG is involvement near the umbilicus. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy presents with urticarial papules and plaques; onset occurs in the third trimester or postpartum and initially involves the striae while sparing the umbilicus, unlike in PG. Atopic eruption of pregnancy has an earlier onset than the other pregnancy-specific dermatoses, often in the first or second trimester, and presents with widespread eczematous lesions.3

Diagnosis

The pregnancy dermatoses with the greatest potential for fetal risks are ICP and PG; therefore, it is critical for health care providers to diagnose these dermatoses in a timely manner and initiate appropriate management. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is confirmed by elevated serum bile acids (ie, >10 µmol/L), often during the third trimester. The risk of fetal morbidity is high in ICP with increased bile acids crossing the placenta causing placental anoxia and impaired cardiomyocyte function.4 Fetal risks, including preterm delivery, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and stillbirth, correlate with the level of bile acids in the serum.5 Maternal prognosis is favorable, but there is an increased association with hepatitis C and hepatobiliary disease.6

Diagnosis of PG is confirmed by classic biopsy results and direct immunofluorescence revealing C3 with or without IgG in a linear band along the basement membrane zone. Additionally, complement indirect immunofluorescence reveals circulating IgG anti–basement membrane zone antibodies. Pemphigoid gestationis is associated with increased fetal risks of preterm labor and intrauterine growth retardation.7 Clinical findings of PG may present in the fetus upon delivery due to transmission of autoantibodies across the placenta. The symptoms usually are mild.8 An increased risk of Graves disease has been reported in mothers with PG.

In most cases, diagnosis of PEP is based on history and morphology, but if the presentation is not classic, skin biopsy must be used to differentiate it from PG as well as more common dermatologic conditions such as contact dermatitis, drug and viral eruptions, and urticaria.

Atopic eruption of pregnancy manifests as widespread eczematous excoriated papules and plaques. Lesions of prurigo nodularis are common.

Comorbidities

It is important to be aware of specific clinical associations related to pregnancy-specific dermatoses. Pemphigoid gestationis has been associated with gestational trophoblastic tumors including hydatiform mole and choriocarcinoma.4 An increased risk for Graves disease has been reported in patients with PG.9 Patients who develop ICP have a higher incidence of hepatitis C, postpartum cholecystitis, gallstones, and nonalcoholic cirrhosis.8 Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy is associated with a notably higher incidence in multiple gestation pregnancies.2

Treatment and Management

Management of ICP requires an accurate and timely diagnosis, and advanced neonatal-obstetric management is critical.3 Ursodeoxycholic acid is the treatment of choice and reduces pruritus, prolongs pregnancy, and reduces fetal risk.4 Most stillbirths cluster at the 38th week of pregnancy, and patients with ICP and highly elevated serum bile acids (>40 µmol/L) should be considered for delivery at 37 weeks or earlier.5

Management of the other cutaneous disorders of pregnancy can be challenging for health care providers based on safety concerns for the fetus. Although it is important to minimize risks to the fetus, it also is important to adequately treat the mother’s cutaneous disease, which requires a solid knowledge of drug safety during pregnancy. The former US Food and Drug Administration classification system using A, B, C, D, and X pregnancy categories was replaced by the Pregnancy Lactation Label Final Rule, which provides counseling on medication safety during pregnancy.10 In 2014, Murase et al11 published a review of dermatologic medication safety during pregnancy, which serves as an excellent guide.

Before instituting treatment, the therapeutic plan should be discussed with the physician managing the patient’s pregnancy. In general, topical steroids are considered safe during pregnancy, and low-potency to moderate-potency topical steroids are preferred. If possible, use of topical steroids should be limited to less than 300 g for the duration of the pregnancy. Fluticasone propionate should be avoided during pregnancy because it is not metabolized by the placenta. When systemic steroids are considered appropriate for management during pregnancy, nonhalogenated corticosteroids such as prednisone and prednisolone are preferred because they are enzymatically inactivated by the placenta, which results in a favorable maternal-fetal gradient.12 There has been concern expressed in the medical literature that systemic steroids during the first trimester may increase the risk of cleft lip and cleft palate.3,12 When managing pregnancy dermatoses, consideration should be given to keep prednisone exposure below 20 mg/d, and try to limit prolonged use to 7.5 mg/d. However, this may not be possible in PG.3 Vitamin D and calcium supplementation may be appropriate when patients are on prolonged systemic steroids to control disease.

Antihistamines can be used to control pruritus complicating pregnancy-associated dermatoses. First-generation antihistamines such as chlorpheniramine and diphenhydramine are preferred due to long-term safety data.3,11,12 Loratadine is the first choice and cetirizine is the second choice if a second-generation antihistamine is preferred.3 Loratadine is preferred during breastfeeding due to less sedation.12 High-dose antihistamines prior to delivery may cause concerns for potential side effects in the newborn, including tremulousness, irritability, and poor feeding.

Recurrence

Women with pregnancy dermatoses often are concerned about recurrence with future pregnancies. Pemphigoid gestationis may flare with subsequent pregnancies, subsequent menses, or with oral contraceptive use.3 Recurrence of PEP in subsequent pregnancies is rare and usually is less severe than the primary eruption.8 Often, the rare recurrent eruption of PEP is associated with multigestational pregnancies.2 Mothers can anticipate a recurrence of ICP in up to 60% to 70% of future pregnancies. Patients with AEP have an underlying atopic diathesis, and recurrence in future pregnancies is not uncommon.8

Final Thoughts

In summary, it is important for health care providers to recognize the specific cutaneous disorders of pregnancy and their potential fetal complications. The anatomical location of onset of the dermatosis and timing of onset during pregnancy can give important clues. Appropriate management, especially with ICP, can minimize fetal complications. A fundamental knowledge of medication safety and management during pregnancy is essential. Rashes during pregnancy can cause anxiety in the mother and family and require support, comfort, and guidance.

- Ambrose-Rudolph CM, Müllegger RR, Vaughn-Jones SA, et al. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:395-404.

- Bechtel M, Plotner A. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58:104-111.

- Bechtel M. Pruritus in pregnancy and its management. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:259-265.

- Ambrose-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy—clues to diagnosis, fetal risk, and therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:265-275.

- Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-controlled study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482-1491.

- Bergman H, Melamed N, Koven G. Pruritus in pregnancy: treatment of dermatoses unique to pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:1290-1294.

- Beard MP, Millington GW. Recent developments in the specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:1-14.

- Shears S, Blaszczak A, Kaffenberger J. Pregnancy dermatosis. In: Tyler KH, ed. Cutaneous Disorders of Pregnancy. 1st ed. Springer Nature; 2020:13-39.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2015;26:274-284.

- Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Fed Registr. 2014;79:72064-72103. To be codified at 21 CFR § 201.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part 1. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;401:E1-E14.

- Friedman B, Bercovitch L. Atopic dermatitis in pregnancy. In: Tyler KH, ed. Cutaneous Disorders of Pregnancy. Springer Nature; 2020:59-74.

- Ambrose-Rudolph CM, Müllegger RR, Vaughn-Jones SA, et al. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:395-404.

- Bechtel M, Plotner A. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015;58:104-111.

- Bechtel M. Pruritus in pregnancy and its management. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:259-265.

- Ambrose-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy—clues to diagnosis, fetal risk, and therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:265-275.

- Geenes V, Chappell LC, Seed PT, et al. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-controlled study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482-1491.

- Bergman H, Melamed N, Koven G. Pruritus in pregnancy: treatment of dermatoses unique to pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:1290-1294.

- Beard MP, Millington GW. Recent developments in the specific dermatoses of pregnancy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:1-14.

- Shears S, Blaszczak A, Kaffenberger J. Pregnancy dermatosis. In: Tyler KH, ed. Cutaneous Disorders of Pregnancy. 1st ed. Springer Nature; 2020:13-39.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2015;26:274-284.

- Content and format of labeling for human prescription drug and biological products; requirements for pregnancy and lactation labeling. Fed Registr. 2014;79:72064-72103. To be codified at 21 CFR § 201.

- Murase JE, Heller MM, Butler DC. Safety of dermatologic medications in pregnancy and lactation: part 1. pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;401:E1-E14.

- Friedman B, Bercovitch L. Atopic dermatitis in pregnancy. In: Tyler KH, ed. Cutaneous Disorders of Pregnancy. Springer Nature; 2020:59-74.

Fauci says ‘unprecedented’ conditions could influence COVID vaccine approval for kids

“From a public health standpoint, I think we have an evolving situation,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in a moderated session with Lee Beers, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

The reasons for this shift remain unclear, he said.

Dr. Beers emphasized the ability of pediatric hospitalists to be flexible in the face of uncertainty and the evolving virus, and asked Dr. Fauci to elaborate on the unique traits of the delta variant that make it especially challenging.

“There is no doubt that delta transmits much more efficiently than the alpha variant or any other variant,” Dr. Fauci said. The transmissibility is evident in comparisons of the level of virus in the nasopharynx of the delta variant, compared with the original alpha COVID-19 virus – delta is as much as 1,000 times higher, he explained.

In addition, the level of virus in the nasopharynx of vaccinated individuals who develop breakthrough infections with the delta variant is similar to the levels in unvaccinated individuals who are infected with the delta variant.

The delta variant is “the tough guy on the block” at the moment, Dr. Fauci said.

Dr. Fauci also responded to a question on the lack of winter viruses, such as RSV and the flu, last winter, but the surge in these viruses over the summer.

This winter’s activity remains uncertain, Dr. Fauci said. However, he speculated “with a strong dose of humility and modesty” that viruses tend to have niches, some are seasonal, and the winter viruses that were displaced by COVID-19 hit harder in the summer instead. “If I were a [non-COVID] virus looking for a niche, I would be really confused,” he said. “I don’t know what will happen this winter, but if we get good control over COVID-19 by winter, we could have a very vengeful influenza season,” he said. “This is speculation, I don’t have any data for this,” he cautioned.

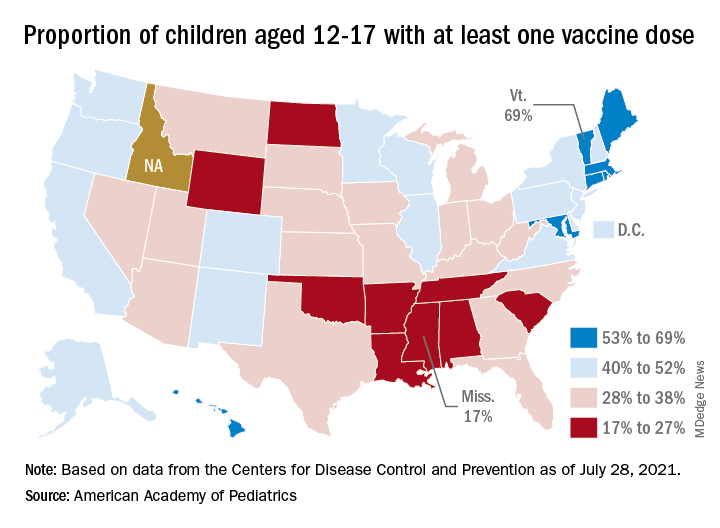

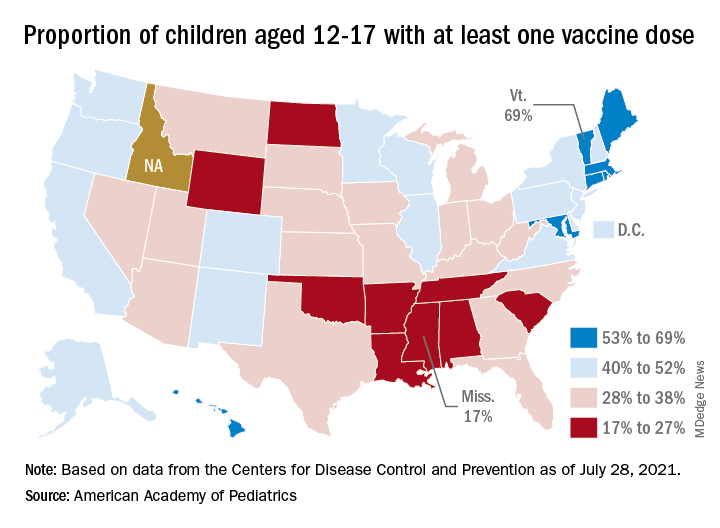

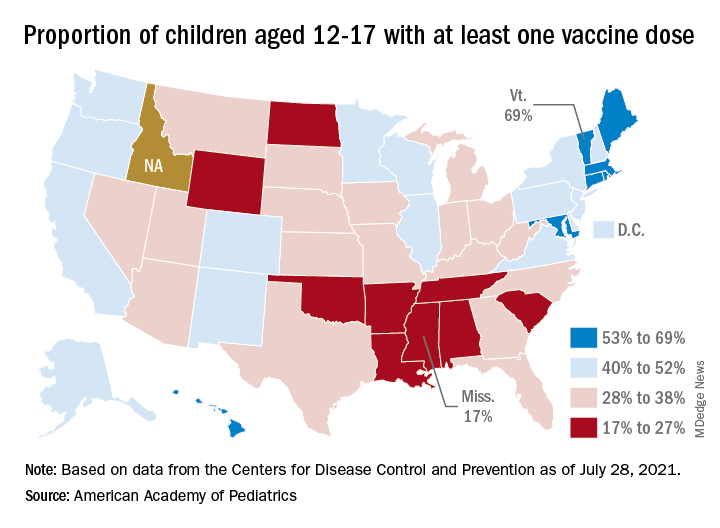

Dr. Beers raised the issue of back-to-school safety, and the updated AAP guidance for universal masking for K-12 students. “Our guidance about return to school gets updated as the situation changes and we gain a better understanding of how kids can get to school safely,” she said. A combination of factors affect back-to-school guidance, including the ineligibility of children younger than 12 years to be vaccinated, the number of adolescents who are eligible but have not been vaccinated, and the challenge for educators to navigate which children should wear masks, Dr. Beers said.

“We want to get vaccines for our youngest kids as soon as safely possible,” Dr. Beers emphasized. She noted that the same urgency is needed to provide vaccines for children as for adults, although “we have to do it safely, and be sure and feel confident in the data.”

When asked to comment about the status of FDA authorization of COVID-19 vaccines for younger children, Dr. Fauci described the current situation as one that “might require some unprecedented and unique action” on the part of the FDA, which tends to move cautiously because of safety considerations. However, concerns about adverse events might get in the way of protecting children against what “you are really worried about,” in this case COVID-19 and its variants, he said. Despite the breakthrough infections, “vaccination continues to very adequately protect people from getting severe disease,” he emphasized.

Dr. Fauci also said that he believes the current data support boosters for the immune compromised; however “it is a different story about the general vaccinated population and the vaccinated elderly,” he said. Sooner or later most people will likely need boosters; “the question is who, when, and how soon,” he noted.

Dr. Fauci wrapped up the session with kudos and support for the pediatric health care community. “As a nonpediatrician, I have a great deal of respect for the job you are doing,” he said. “Keep up the great work.”

Dr. Beers echoed this sentiment, saying that she was “continually awed, impressed, and inspired” by how the pediatric hospitalists are navigating the ever-changing pandemic environment.

“From a public health standpoint, I think we have an evolving situation,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in a moderated session with Lee Beers, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

The reasons for this shift remain unclear, he said.

Dr. Beers emphasized the ability of pediatric hospitalists to be flexible in the face of uncertainty and the evolving virus, and asked Dr. Fauci to elaborate on the unique traits of the delta variant that make it especially challenging.

“There is no doubt that delta transmits much more efficiently than the alpha variant or any other variant,” Dr. Fauci said. The transmissibility is evident in comparisons of the level of virus in the nasopharynx of the delta variant, compared with the original alpha COVID-19 virus – delta is as much as 1,000 times higher, he explained.

In addition, the level of virus in the nasopharynx of vaccinated individuals who develop breakthrough infections with the delta variant is similar to the levels in unvaccinated individuals who are infected with the delta variant.

The delta variant is “the tough guy on the block” at the moment, Dr. Fauci said.

Dr. Fauci also responded to a question on the lack of winter viruses, such as RSV and the flu, last winter, but the surge in these viruses over the summer.

This winter’s activity remains uncertain, Dr. Fauci said. However, he speculated “with a strong dose of humility and modesty” that viruses tend to have niches, some are seasonal, and the winter viruses that were displaced by COVID-19 hit harder in the summer instead. “If I were a [non-COVID] virus looking for a niche, I would be really confused,” he said. “I don’t know what will happen this winter, but if we get good control over COVID-19 by winter, we could have a very vengeful influenza season,” he said. “This is speculation, I don’t have any data for this,” he cautioned.

Dr. Beers raised the issue of back-to-school safety, and the updated AAP guidance for universal masking for K-12 students. “Our guidance about return to school gets updated as the situation changes and we gain a better understanding of how kids can get to school safely,” she said. A combination of factors affect back-to-school guidance, including the ineligibility of children younger than 12 years to be vaccinated, the number of adolescents who are eligible but have not been vaccinated, and the challenge for educators to navigate which children should wear masks, Dr. Beers said.

“We want to get vaccines for our youngest kids as soon as safely possible,” Dr. Beers emphasized. She noted that the same urgency is needed to provide vaccines for children as for adults, although “we have to do it safely, and be sure and feel confident in the data.”

When asked to comment about the status of FDA authorization of COVID-19 vaccines for younger children, Dr. Fauci described the current situation as one that “might require some unprecedented and unique action” on the part of the FDA, which tends to move cautiously because of safety considerations. However, concerns about adverse events might get in the way of protecting children against what “you are really worried about,” in this case COVID-19 and its variants, he said. Despite the breakthrough infections, “vaccination continues to very adequately protect people from getting severe disease,” he emphasized.

Dr. Fauci also said that he believes the current data support boosters for the immune compromised; however “it is a different story about the general vaccinated population and the vaccinated elderly,” he said. Sooner or later most people will likely need boosters; “the question is who, when, and how soon,” he noted.

Dr. Fauci wrapped up the session with kudos and support for the pediatric health care community. “As a nonpediatrician, I have a great deal of respect for the job you are doing,” he said. “Keep up the great work.”

Dr. Beers echoed this sentiment, saying that she was “continually awed, impressed, and inspired” by how the pediatric hospitalists are navigating the ever-changing pandemic environment.

“From a public health standpoint, I think we have an evolving situation,” said Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, in a moderated session with Lee Beers, MD, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine annual conference.

The reasons for this shift remain unclear, he said.

Dr. Beers emphasized the ability of pediatric hospitalists to be flexible in the face of uncertainty and the evolving virus, and asked Dr. Fauci to elaborate on the unique traits of the delta variant that make it especially challenging.

“There is no doubt that delta transmits much more efficiently than the alpha variant or any other variant,” Dr. Fauci said. The transmissibility is evident in comparisons of the level of virus in the nasopharynx of the delta variant, compared with the original alpha COVID-19 virus – delta is as much as 1,000 times higher, he explained.

In addition, the level of virus in the nasopharynx of vaccinated individuals who develop breakthrough infections with the delta variant is similar to the levels in unvaccinated individuals who are infected with the delta variant.

The delta variant is “the tough guy on the block” at the moment, Dr. Fauci said.

Dr. Fauci also responded to a question on the lack of winter viruses, such as RSV and the flu, last winter, but the surge in these viruses over the summer.

This winter’s activity remains uncertain, Dr. Fauci said. However, he speculated “with a strong dose of humility and modesty” that viruses tend to have niches, some are seasonal, and the winter viruses that were displaced by COVID-19 hit harder in the summer instead. “If I were a [non-COVID] virus looking for a niche, I would be really confused,” he said. “I don’t know what will happen this winter, but if we get good control over COVID-19 by winter, we could have a very vengeful influenza season,” he said. “This is speculation, I don’t have any data for this,” he cautioned.

Dr. Beers raised the issue of back-to-school safety, and the updated AAP guidance for universal masking for K-12 students. “Our guidance about return to school gets updated as the situation changes and we gain a better understanding of how kids can get to school safely,” she said. A combination of factors affect back-to-school guidance, including the ineligibility of children younger than 12 years to be vaccinated, the number of adolescents who are eligible but have not been vaccinated, and the challenge for educators to navigate which children should wear masks, Dr. Beers said.

“We want to get vaccines for our youngest kids as soon as safely possible,” Dr. Beers emphasized. She noted that the same urgency is needed to provide vaccines for children as for adults, although “we have to do it safely, and be sure and feel confident in the data.”

When asked to comment about the status of FDA authorization of COVID-19 vaccines for younger children, Dr. Fauci described the current situation as one that “might require some unprecedented and unique action” on the part of the FDA, which tends to move cautiously because of safety considerations. However, concerns about adverse events might get in the way of protecting children against what “you are really worried about,” in this case COVID-19 and its variants, he said. Despite the breakthrough infections, “vaccination continues to very adequately protect people from getting severe disease,” he emphasized.

Dr. Fauci also said that he believes the current data support boosters for the immune compromised; however “it is a different story about the general vaccinated population and the vaccinated elderly,” he said. Sooner or later most people will likely need boosters; “the question is who, when, and how soon,” he noted.

Dr. Fauci wrapped up the session with kudos and support for the pediatric health care community. “As a nonpediatrician, I have a great deal of respect for the job you are doing,” he said. “Keep up the great work.”

Dr. Beers echoed this sentiment, saying that she was “continually awed, impressed, and inspired” by how the pediatric hospitalists are navigating the ever-changing pandemic environment.

FROM PHM 2021

Long COVID symptoms rare but real in some kids

School-aged children with SARS-CoV-2 infection had only a few mild symptoms and typically recovered in 6 days, with more than 98% recovering in 8 weeks, a large U.K. study of smartphone data reassuringly reports.

In a small proportion (4.4%), however, COVID-19 symptoms such as fatigue, headache, or loss of smell persisted beyond a month, highlighting the need for ongoing pediatric care, according to Erika Molteni, PhD, a research fellow at King’s College, London, and colleagues.

The results, published online in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, also indicated that some children who had non-COVID infections were also susceptible to prolonged symptoms. “Our data highlight that other illnesses, such as colds and flu, can also have prolonged symptoms in children and it is important to consider this when planning for pediatric health services during the pandemic and beyond,” Michael Absoud, PhD, a senior coauthor and a King’s College consultant and senior lecturer, said in a news release. “All children who have persistent symptoms – from any illness – need timely multidisciplinary support linked with education, to enable them to find their individual pathway to recovery.”

Using a “citizen science” approach, the study extracted data from a smartphone app for tracking COVID symptoms in the ZOE COVID Study. The researchers looked at 258,790 children aged 5-17 years whose details were reported by adult proxies such as parents and carers from March 24, 2020, to Feb. 22, 2021. Of these, 75,529 had undergone a valid SARS-CoV-2 test.

The study also assessed symptoms in a randomly selected, age- and sex-matched cohort of 1,734 children in the app database who tested negative for COVID-19 but may have had other illnesses such as colds or flu.

In the 1,734 children testing positive for COVID-19 (approximately 50% each boys and girls), the most common symptoms were headache (62.2%) and fatigue (55.0%). More than 10% of the entire cohort had underlying asthma, but other comorbidities were very rare.

To assess the effect of age, the children were assessed in two groups: 5-11 years (n = 588) and 12-17 years (n = 1,146).

While unable to cross-check app reporting against actual medical records, the study suggested that illness lasted longer in COVID-positive than COVID-negative children, with a median of 6 days (interquartile range, 3-11) versus 3 days (IQR, 2-7). Furthermore, illness duration was positively associated with age: older children (median, 7 days; IQR, 3-12) versus younger children (median, 5 days; IQR, 2-9).

In 77 (4.4%) of the 1,734 COVID-positive children, illness persisted for at least 28 days, again more often in older than younger children: 5.1% of older children versus 3.1% of younger children (P = .046).

In addition, those with COVID-19 were more likely than children with non-COVID illness to be sick for more than 4 weeks: 4.4% versus 0.9%. At 4 weeks, however, the few children with other illnesses tended to have more symptoms, exhibiting a median of five symptoms versus two symptoms in the COVID-positive group.

“I tend to agree with the U.K. findings. COVID-19 in most school-age children is asymptomatic or a brief, self-limiting illness,” Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, said in an interview. “The few children who need hospitalization have also mostly fully recovered by the time they are seen for their first outpatient clinic follow-up visit.”

Dr. Mohandas, who was not involved in the U.K. study, added that in her experience a small percentage, particularly adolescents, have some lingering symptoms after infection including fatigue, loss of appetite, and changes in smell and taste. “Identifying children with persistent illness and providing support and multidisciplinary care based on their symptomatology can make a positive impact on patients and their families.”

Recent research has suggested that long symptoms can persist for 3 months in 6% of children with COVID-19. And data from China have indicated that the prevalence of coinfection may be higher than in older patients.

In an accompanying comment, Dana Mahr, PhD, and Bruno J. Strasser, PhD, researchers in the faculty of science at the University of Geneva, said the app-based study “illustrates the potential and challenges of what has been called citizenship science,” in which projects rely on data input from nonscientists.

But while potentially democratizing participation in medical research, this subjective approach has the inherent bias of self-reporting (and in the case of the current study, proxy reporting), and can introduce potential conflicts of interest owing to the politicization of certain diseases.

In the case of the current study, Dr. Mahr and Dr. Strasser argued that, since the COVID-19 test result is known to participants, a pediatrician using objective criteria is better positioned to control for reporting biases than a parent asking a child about symptoms. “Entering data on a smartphone app is not equivalent to discussing with a pediatrician or health care worker who can answer further questions and concerns of participants, an especially important factor for underserved communities,” they wrote. “Citizen science will continue to require a close interaction with professional medical researchers to turn unique illness experiences into research data.”

This study was funded by Zoe Limited, the U.K. Government Department of Health and Social Care, Wellcome Trust, the U.K. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the U.K. Research and Innovation London Medical Imaging and Artificial Intelligence Centre for Value Based Healthcare, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research, the U.K. Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Society. Several study authors have disclosed support from various research-funding agencies and Zoe Limited supported all aspects of building and running the symptom-tracking application. Dr. Mahr and Dr. Strasser declared no competing interests. Dr. Mohandas disclosed no competing interests with regard to her comments.

School-aged children with SARS-CoV-2 infection had only a few mild symptoms and typically recovered in 6 days, with more than 98% recovering in 8 weeks, a large U.K. study of smartphone data reassuringly reports.

In a small proportion (4.4%), however, COVID-19 symptoms such as fatigue, headache, or loss of smell persisted beyond a month, highlighting the need for ongoing pediatric care, according to Erika Molteni, PhD, a research fellow at King’s College, London, and colleagues.

The results, published online in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, also indicated that some children who had non-COVID infections were also susceptible to prolonged symptoms. “Our data highlight that other illnesses, such as colds and flu, can also have prolonged symptoms in children and it is important to consider this when planning for pediatric health services during the pandemic and beyond,” Michael Absoud, PhD, a senior coauthor and a King’s College consultant and senior lecturer, said in a news release. “All children who have persistent symptoms – from any illness – need timely multidisciplinary support linked with education, to enable them to find their individual pathway to recovery.”

Using a “citizen science” approach, the study extracted data from a smartphone app for tracking COVID symptoms in the ZOE COVID Study. The researchers looked at 258,790 children aged 5-17 years whose details were reported by adult proxies such as parents and carers from March 24, 2020, to Feb. 22, 2021. Of these, 75,529 had undergone a valid SARS-CoV-2 test.

The study also assessed symptoms in a randomly selected, age- and sex-matched cohort of 1,734 children in the app database who tested negative for COVID-19 but may have had other illnesses such as colds or flu.

In the 1,734 children testing positive for COVID-19 (approximately 50% each boys and girls), the most common symptoms were headache (62.2%) and fatigue (55.0%). More than 10% of the entire cohort had underlying asthma, but other comorbidities were very rare.

To assess the effect of age, the children were assessed in two groups: 5-11 years (n = 588) and 12-17 years (n = 1,146).

While unable to cross-check app reporting against actual medical records, the study suggested that illness lasted longer in COVID-positive than COVID-negative children, with a median of 6 days (interquartile range, 3-11) versus 3 days (IQR, 2-7). Furthermore, illness duration was positively associated with age: older children (median, 7 days; IQR, 3-12) versus younger children (median, 5 days; IQR, 2-9).

In 77 (4.4%) of the 1,734 COVID-positive children, illness persisted for at least 28 days, again more often in older than younger children: 5.1% of older children versus 3.1% of younger children (P = .046).

In addition, those with COVID-19 were more likely than children with non-COVID illness to be sick for more than 4 weeks: 4.4% versus 0.9%. At 4 weeks, however, the few children with other illnesses tended to have more symptoms, exhibiting a median of five symptoms versus two symptoms in the COVID-positive group.

“I tend to agree with the U.K. findings. COVID-19 in most school-age children is asymptomatic or a brief, self-limiting illness,” Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, said in an interview. “The few children who need hospitalization have also mostly fully recovered by the time they are seen for their first outpatient clinic follow-up visit.”

Dr. Mohandas, who was not involved in the U.K. study, added that in her experience a small percentage, particularly adolescents, have some lingering symptoms after infection including fatigue, loss of appetite, and changes in smell and taste. “Identifying children with persistent illness and providing support and multidisciplinary care based on their symptomatology can make a positive impact on patients and their families.”

Recent research has suggested that long symptoms can persist for 3 months in 6% of children with COVID-19. And data from China have indicated that the prevalence of coinfection may be higher than in older patients.

In an accompanying comment, Dana Mahr, PhD, and Bruno J. Strasser, PhD, researchers in the faculty of science at the University of Geneva, said the app-based study “illustrates the potential and challenges of what has been called citizenship science,” in which projects rely on data input from nonscientists.

But while potentially democratizing participation in medical research, this subjective approach has the inherent bias of self-reporting (and in the case of the current study, proxy reporting), and can introduce potential conflicts of interest owing to the politicization of certain diseases.

In the case of the current study, Dr. Mahr and Dr. Strasser argued that, since the COVID-19 test result is known to participants, a pediatrician using objective criteria is better positioned to control for reporting biases than a parent asking a child about symptoms. “Entering data on a smartphone app is not equivalent to discussing with a pediatrician or health care worker who can answer further questions and concerns of participants, an especially important factor for underserved communities,” they wrote. “Citizen science will continue to require a close interaction with professional medical researchers to turn unique illness experiences into research data.”

This study was funded by Zoe Limited, the U.K. Government Department of Health and Social Care, Wellcome Trust, the U.K. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the U.K. Research and Innovation London Medical Imaging and Artificial Intelligence Centre for Value Based Healthcare, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research, the U.K. Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Society. Several study authors have disclosed support from various research-funding agencies and Zoe Limited supported all aspects of building and running the symptom-tracking application. Dr. Mahr and Dr. Strasser declared no competing interests. Dr. Mohandas disclosed no competing interests with regard to her comments.

School-aged children with SARS-CoV-2 infection had only a few mild symptoms and typically recovered in 6 days, with more than 98% recovering in 8 weeks, a large U.K. study of smartphone data reassuringly reports.

In a small proportion (4.4%), however, COVID-19 symptoms such as fatigue, headache, or loss of smell persisted beyond a month, highlighting the need for ongoing pediatric care, according to Erika Molteni, PhD, a research fellow at King’s College, London, and colleagues.

The results, published online in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, also indicated that some children who had non-COVID infections were also susceptible to prolonged symptoms. “Our data highlight that other illnesses, such as colds and flu, can also have prolonged symptoms in children and it is important to consider this when planning for pediatric health services during the pandemic and beyond,” Michael Absoud, PhD, a senior coauthor and a King’s College consultant and senior lecturer, said in a news release. “All children who have persistent symptoms – from any illness – need timely multidisciplinary support linked with education, to enable them to find their individual pathway to recovery.”

Using a “citizen science” approach, the study extracted data from a smartphone app for tracking COVID symptoms in the ZOE COVID Study. The researchers looked at 258,790 children aged 5-17 years whose details were reported by adult proxies such as parents and carers from March 24, 2020, to Feb. 22, 2021. Of these, 75,529 had undergone a valid SARS-CoV-2 test.

The study also assessed symptoms in a randomly selected, age- and sex-matched cohort of 1,734 children in the app database who tested negative for COVID-19 but may have had other illnesses such as colds or flu.

In the 1,734 children testing positive for COVID-19 (approximately 50% each boys and girls), the most common symptoms were headache (62.2%) and fatigue (55.0%). More than 10% of the entire cohort had underlying asthma, but other comorbidities were very rare.

To assess the effect of age, the children were assessed in two groups: 5-11 years (n = 588) and 12-17 years (n = 1,146).

While unable to cross-check app reporting against actual medical records, the study suggested that illness lasted longer in COVID-positive than COVID-negative children, with a median of 6 days (interquartile range, 3-11) versus 3 days (IQR, 2-7). Furthermore, illness duration was positively associated with age: older children (median, 7 days; IQR, 3-12) versus younger children (median, 5 days; IQR, 2-9).

In 77 (4.4%) of the 1,734 COVID-positive children, illness persisted for at least 28 days, again more often in older than younger children: 5.1% of older children versus 3.1% of younger children (P = .046).

In addition, those with COVID-19 were more likely than children with non-COVID illness to be sick for more than 4 weeks: 4.4% versus 0.9%. At 4 weeks, however, the few children with other illnesses tended to have more symptoms, exhibiting a median of five symptoms versus two symptoms in the COVID-positive group.

“I tend to agree with the U.K. findings. COVID-19 in most school-age children is asymptomatic or a brief, self-limiting illness,” Sindhu Mohandas, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, said in an interview. “The few children who need hospitalization have also mostly fully recovered by the time they are seen for their first outpatient clinic follow-up visit.”

Dr. Mohandas, who was not involved in the U.K. study, added that in her experience a small percentage, particularly adolescents, have some lingering symptoms after infection including fatigue, loss of appetite, and changes in smell and taste. “Identifying children with persistent illness and providing support and multidisciplinary care based on their symptomatology can make a positive impact on patients and their families.”

Recent research has suggested that long symptoms can persist for 3 months in 6% of children with COVID-19. And data from China have indicated that the prevalence of coinfection may be higher than in older patients.

In an accompanying comment, Dana Mahr, PhD, and Bruno J. Strasser, PhD, researchers in the faculty of science at the University of Geneva, said the app-based study “illustrates the potential and challenges of what has been called citizenship science,” in which projects rely on data input from nonscientists.

But while potentially democratizing participation in medical research, this subjective approach has the inherent bias of self-reporting (and in the case of the current study, proxy reporting), and can introduce potential conflicts of interest owing to the politicization of certain diseases.

In the case of the current study, Dr. Mahr and Dr. Strasser argued that, since the COVID-19 test result is known to participants, a pediatrician using objective criteria is better positioned to control for reporting biases than a parent asking a child about symptoms. “Entering data on a smartphone app is not equivalent to discussing with a pediatrician or health care worker who can answer further questions and concerns of participants, an especially important factor for underserved communities,” they wrote. “Citizen science will continue to require a close interaction with professional medical researchers to turn unique illness experiences into research data.”

This study was funded by Zoe Limited, the U.K. Government Department of Health and Social Care, Wellcome Trust, the U.K. Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the U.K. Research and Innovation London Medical Imaging and Artificial Intelligence Centre for Value Based Healthcare, the U.K. National Institute for Health Research, the U.K. Medical Research Council, the British Heart Foundation, and the Alzheimer’s Society. Several study authors have disclosed support from various research-funding agencies and Zoe Limited supported all aspects of building and running the symptom-tracking application. Dr. Mahr and Dr. Strasser declared no competing interests. Dr. Mohandas disclosed no competing interests with regard to her comments.

FROM THE LANCET CHILD & ADOLESCENT HEALTH

How heat kills: Deadly weather ‘cooking’ people from within

Millions of Americans have been languishing for weeks in the oppressive heat and humidity of a merciless summer. Deadly heat has already taken the lives of hundreds in the Pacific Northwest alone, with numbers likely to grow as the full impact of heat-related deaths eventually comes to light.

In the final week of July, the National Weather Service issued excessive heat warnings for 17 states, stretching from the West Coast, across the Midwest, down south into Louisiana and Georgia. Temperatures 10° to 15° F above average threaten the lives and livelihoods of people all across the country.