User login

Practical Application of Self-Determination Theory to Achieve a Reduction in Postoperative Hypothermia Rate: A Quality Improvement Project

From Children’s Health System of Texas, Division of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Dallas, TX (Drs. Sakhai, Bocanegra, Chandran, Kimatian, and Kiss), UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, Dallas, TX (Drs. Bocanegra, Chandran, Kimatian, and Kiss), and UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Population and Data Sciences, Dallas, TX (Dr. Reisch).

Objective: Policy-driven changes in medical practice have long been the norm. Seldom are changes in clinical practice sought to be brought about by a person’s tendency toward growth or self‐actualization. Many hospitals have instituted hypothermia bundles to help reduce the incidence of unanticipated postoperative hypothermia. Although successful in the short-term, sustained changes are difficult to maintain. We implemented a quality-improvement project focused on addressing the affective components of self-determination theory (SDT) to create sustainable behavioral change while satisfying providers’ basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Methods: A total of 3 Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were enacted over the span of 14 months at a major tertiary care pediatric hospital to recruit and motivate anesthesia providers and perioperative team members to reduce the percentage of hypothermic postsurgical patients by 50%. As an optional initial incentive for participation, anesthesiologists would qualify for American Board of Anesthesiology Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) Part 4 Quality Improvement credits for monitoring their own temperature data and participating in project-related meetings. Providers were given autonomy to develop a personal plan for achieving the desired goals.

Results: The median rate of hypothermia was reduced from 6.9% to 1.6% in July 2019 and was reduced again in July 2020 to 1.3%, an 81% reduction overall. A low hypothermia rate was successfully maintained for at least 21 subsequent months after participants received their MOCA credits in July 2019.

Conclusions: Using an approach that focused on the elements of competency, autonomy, and relatedness central to the principles of SDT, we observed the development of a new culture of vigilance for prevention of hypothermia that successfully endured beyond the project end date.

Keywords: postoperative hypothermia; self-determination theory; motivation; quality improvement.

Perioperative hypothermia, generally accepted as a core temperature less than 36 °C in clinical practice, is a common complication in the pediatric surgical population and is associated with poor postoperative outcomes.1 Hypothermic patients may develop respiratory depression, hypoglycemia, and metabolic acidosis that may lead to decreased oxygen delivery and end organ tissue hypoxia.2-4 Other potential detrimental effects of failing to maintain normal body temperature are impaired clotting factor enzyme function and platelet dysfunction, increasing the risk for postoperative bleeding.5,6 In addition, there are financial implications when hypothermic patients require care and resources postoperatively because of delayed emergence or shivering.7

The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends intraoperative temperature monitoring for procedures when clinically significant changes in body temperature are anticipated.8 Maintenance of normothermia in the pediatric population is especially challenging owing to a larger skin-surface area compared with body mass ratio and less subcutaneous fat content than in adults. Preventing postoperative hypothermia starts preoperatively with parental education and can be as simple as covering the child with a blanket and setting the preoperative room to an acceptably warm temperature.9,10 Intraoperatively, maintaining operating room (OR) temperatures at or above 21.1 °C and using active warming devices and radiant warmers when appropriate are important techniques to preserve the child’s body temperature.11,12

Despite the knowledge of these risks and vigilant avoidance of hypothermia, unplanned perioperative hypothermia can occur in up to 70% of surgical patients.1 Beyond the clinical benefits, as health care marches toward a value-based payment methodology, quality indicators such as avoiding hypothermia may be linked directly to payment.

Self-determination theory (SDT) was first developed in 1980 by Deci and Ryan.13 The central premise of the theory states that people develop their full potential if circumstances allow them to satisfy their basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Under these conditions, people’s natural inclination toward growth can be realized, and they are more likely to internalize external goals. Under an extrinsic reward system, motivation can waver, as people may perceive rewards as controlling.

Many institutions have implemented hypothermia bundles to help decrease the rate of hypothermic patients, but while initially successful, the effectiveness of these interventions tends to fade over time as participants settle into old, comfortable routines.14 With SDT in mind, we designed our quality-improvement (QI) project with interventions to allow clinicians autonomy without instituting rigid guidelines or punitive actions. We aimed to directly address the affective components central to motivation and engagement so that we could bring about long-term meaningful changes in our practice.

Methods

Setting

The hypothermia QI intervention was instituted at a major tertiary care children’s hospital that performs more than 40 000 pediatric general anesthetics annually. Our division of pediatric anesthesiology consists of 66 fellowship-trained pediatric anesthesiologists, 15 or more rotating trainees per month, 13 anesthesiology assistants, 15 anesthesia technicians, and more than 50 perioperative nurses.

The most frequent pediatric surgeries include, but are not limited to, general surgery, otolaryngology, urology, gastroenterology, plastic surgery, neurosurgery, and dentistry. The surgeries are conducted in the hospital’s main operative floor, which consists of 15 ORs and 2 gastroenterology procedure rooms. Although the implementation of the QI project included several operating sites, we focused on collecting temperature data from surgical patients at our main campus recovery unit. We obtained the patients’ initial temperatures upon arrival to the recovery unit from a retrospective electronic health record review of all patients who underwent anesthesia from January 2016 through April 2021.

Postoperative hypothermia was identified as an area of potential improvement after several patients were reported to be hypothermic upon arrival to the recovery unit in the later part of 2018. Further review revealed significant heterogeneity of practices and lack of standardization of patient-warming methods. By comparing the temperatures pre- and postintervention, we could measure the effectiveness of the QI initiative. Prior to the start of our project, the hypothermia rate in our patient population was not actively tracked, and the effectiveness of our variable practice was not measured.

The cutoff for hypothermia for our QI project was defined as body temperature below 36 °C, since this value has been previously used in the literature and is commonly accepted in anesthesia practice as the delineation for hypothermia in patients undergoing general anesthesia.1

Interventions

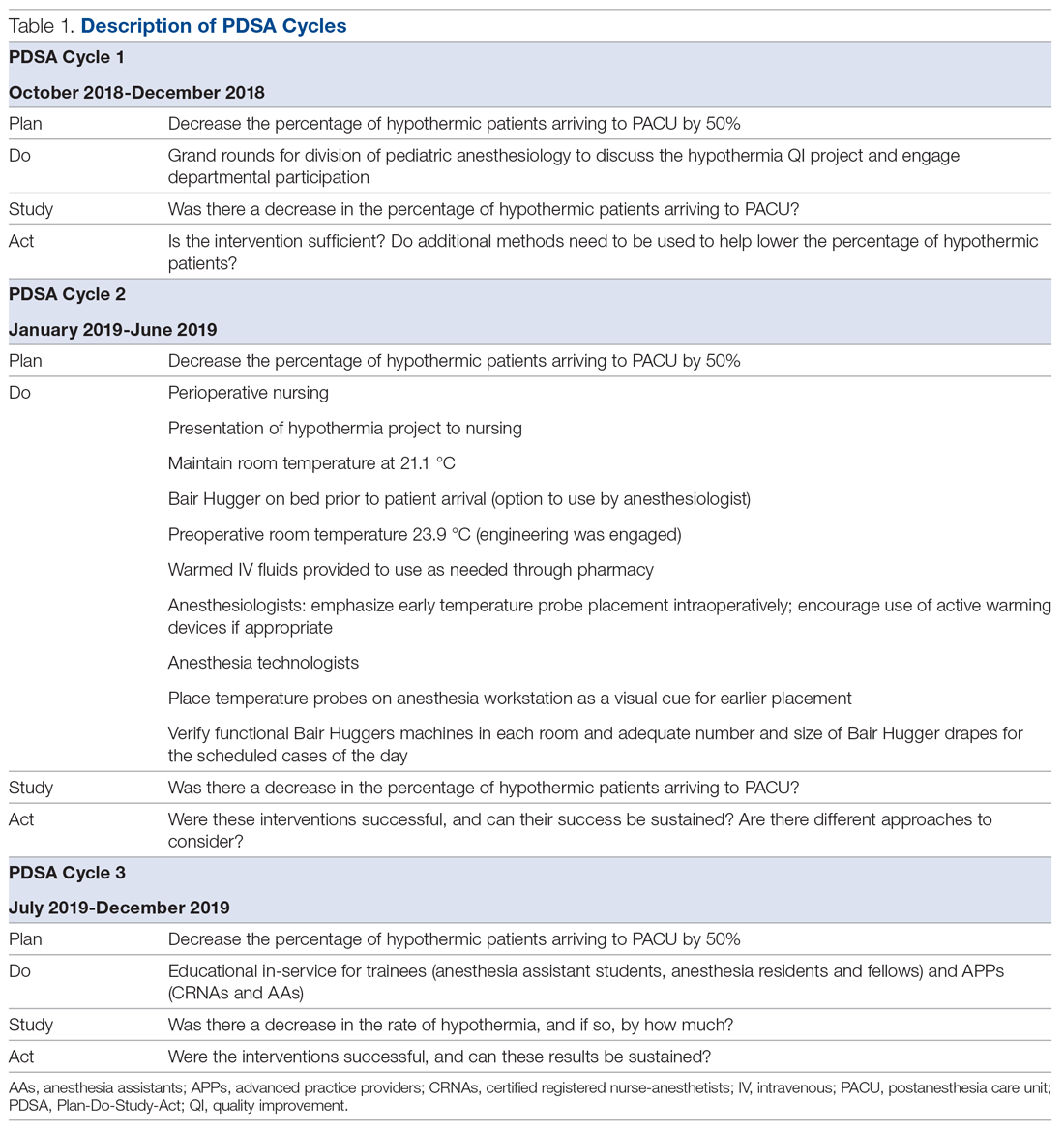

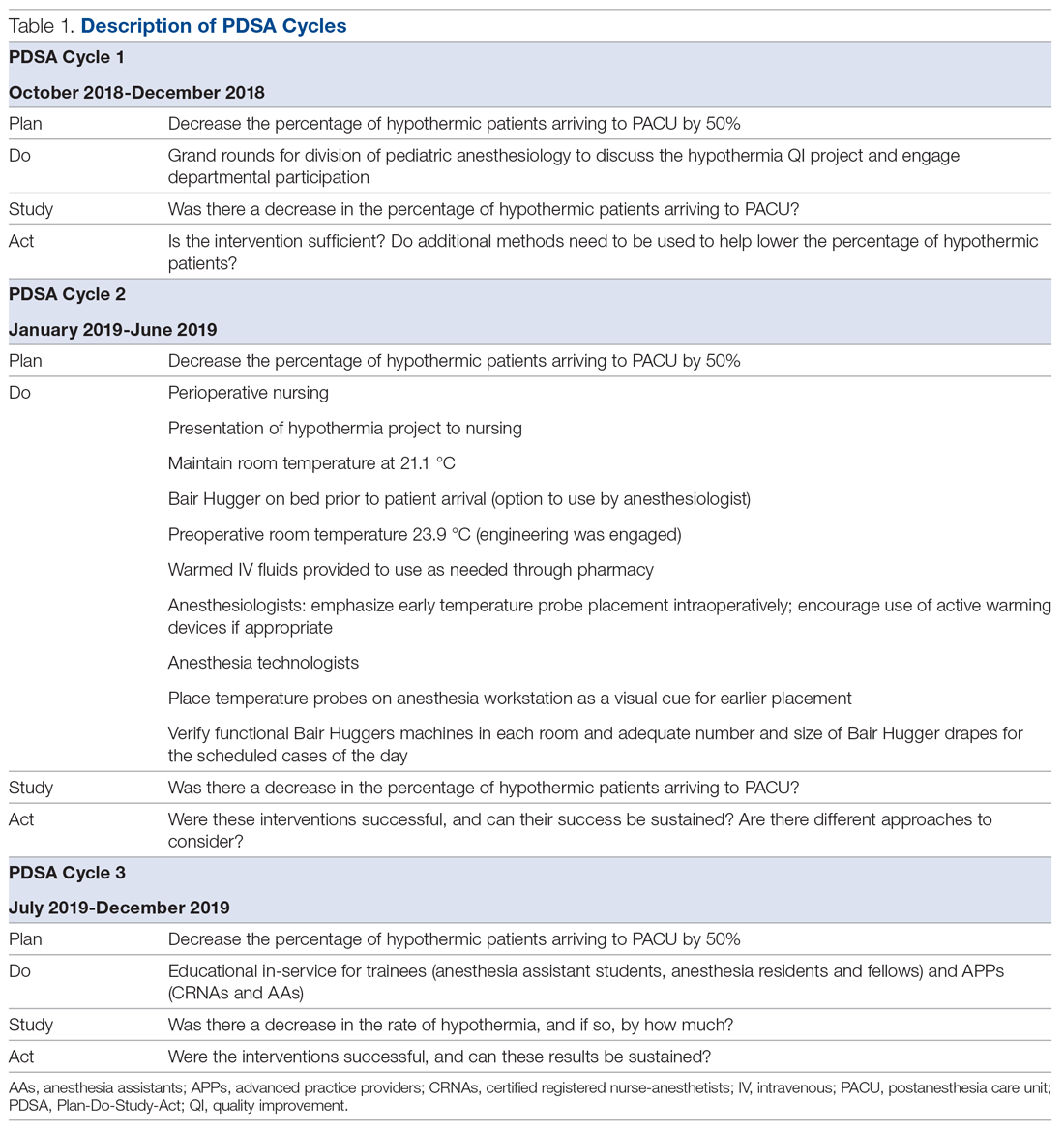

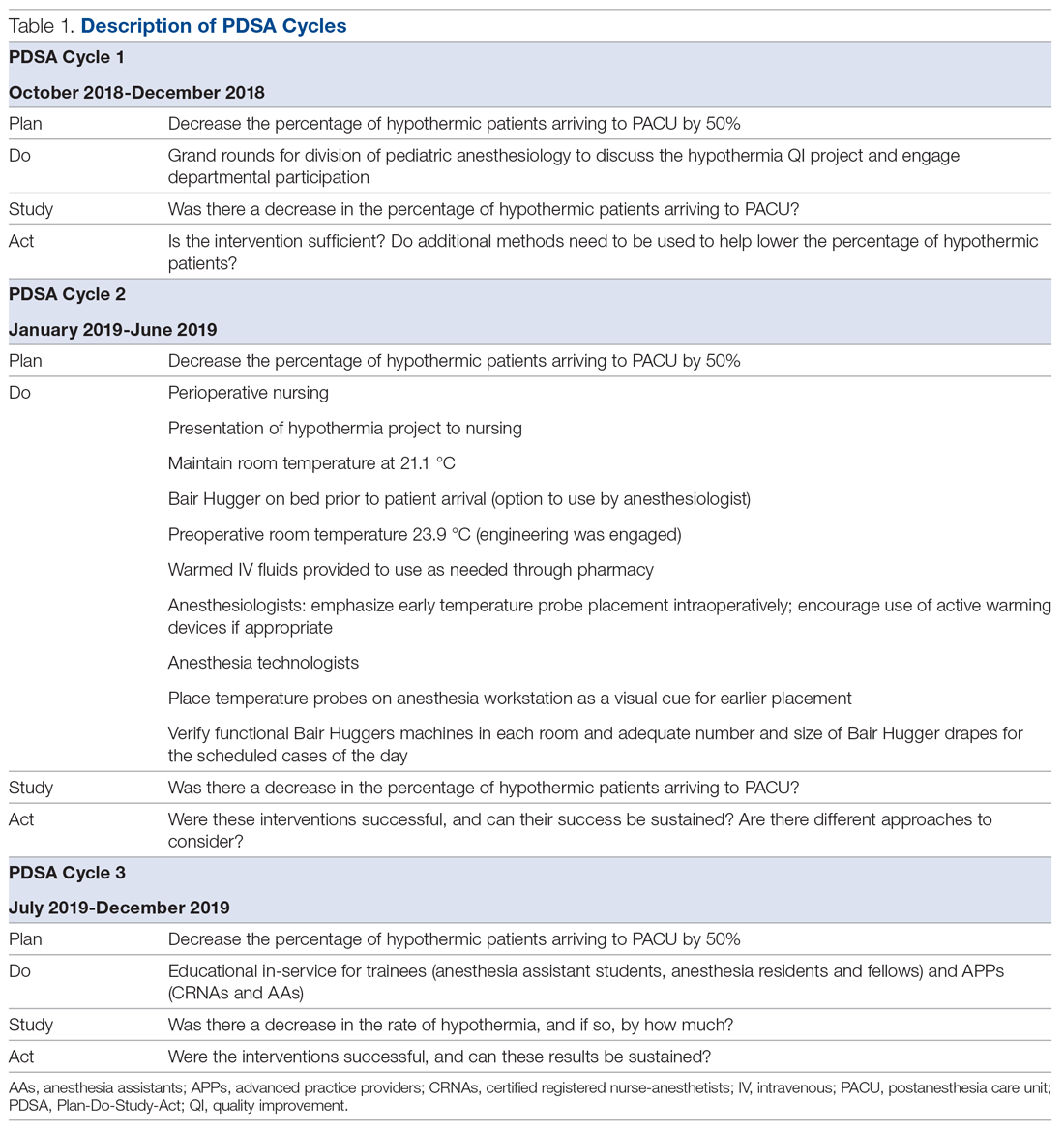

This QI project was designed and modeled after the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement.15 Three cycles of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) were developed and instituted over a 14-month period until December 2019 (Table 1).

A retrospective review was conducted to determine the percentage of surgical patients arriving to our recovery units with an initial temperature reading of less than 36 °C. A project key driver diagram and smart aim were created and approved by the hospital’s continuing medical education (CME) committee for credit via the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Multi-Specialty Portfolio Program, Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) Part 4.

The first PDSA cycle involved introducing the QI project and sharing the aims of the project at a department grand rounds in the latter part of October 2018. Enrollment to participate in the project was open to all anesthesiologists in the division, and participants could earn up to 20 hours of MOCA Part 4 credits. A spreadsheet was developed and maintained to track each anesthesiologist’s monthly percentage of hypothermic patients. The de-identified patient data were shared with the division via monthly emails. In addition, individual providers with a hypothermic patient in the recovery room received a notification email.

The anesthesiologists participated in the QI project by reviewing their personal percentage of hypothermic patients on an ongoing basis to earn the credit. There was no explicit requirement to decrease their own rate of patients with body temperature less than 36 °C or expectation to achieve a predetermined goal, so the participants could not “fail.”

Because of the large interest in this project, a hypothermia committee was formed that consisted of 36 anesthesiologists. This group reviewed the data and exchanged ideas for improvement in November 2018 as part of the first PDSA cycle. The committee met monthly and was responsible for actively engaging other members of the department and perioperative staff to help in this multidisciplinary effort of combating hypothermia in our surgical pediatric population.

PDSA cycle 2 involved several major initiatives, including direct incorporation of the rest of the perioperative team. The perioperative nursing team was educated on the risks of hypothermia and engaged to take an active role by maintaining the operating suite temperature at 21.1 °C and turning on the Bair Hugger (3M) blanket to 43 °C on the OR bed prior to patient arrival to the OR. Additionally, anesthesia technicians (ATs) were tasked with ensuring an adequate supply of Bair Hugger drapes for all cases of the day. The facility’s engineering team was engaged to move the preoperative room temperature controls away from families (who frequently made the rooms cold) and instead set it at a consistent temperature of 23.9 °C. ATs were also asked to place axillary and nasal temperature probes on the anesthesia workstations as a visual reminder to facilitate temperature monitoring closer to the start of anesthesia (instead of the anesthesia provider having to remember to retrieve a temperature probe out of a drawer and place it on the patient). Furthermore, anesthesiologists were instructed via the aforementioned monthly emails and at monthly department meetings to place the temperature probes as early as possible in order to recognize and respond to intraoperative hypothermia in a timelier manner. Finally, supply chain leaders were informed of our expected increase in the use of the blankets and probes and proportionally increased ordering of these supplies to make sure availability would not present an obstacle.

In PDSA cycle 3, trainees (anesthesia assistant students, anesthesia residents and fellows) and advanced practice providers (APPs) (certified registered nurse-anesthetists [CRNAs] and certified anesthesia assistants [C-AAs]) were informed of the QI project. This initiative was guided toward improving vigilance for hypothermia in the rest of the anesthesia team members. The trainees and APPs usually set up the anesthesia area prior to patient arrival, so their recruitment in support of this effort would ensure appropriate OR temperature, active warming device deployment, and the availability and early placement of the correct temperature probe for the case. To facilitate personal accountability, the trainees and APPs were also emailed their own patients’ rate of hypothermia.

Along the course of the project, quarterly committee meetings and departmental monthly meetings served as venues to express concerns and look for areas of improvement, such as specific patterns or trends leading to hypothermic patients. One specific example was the identification of the gastrointestinal endoscopic patients having a rate of hypothermia that was 2% higher than average. Directed education on the importance of Bair Hugger blankets and using warm intravenous fluids worked well to decrease the rate of hypothermia in these patients. This collection of data was shared at regular intervals during monthly department meetings as well and more frequently using departmental emails. The hospital’s secure intranet SharePoint (Microsoft) site was used to share the data among providers.

Study of the interventions and measures

To study the effectiveness and impact of the project to motivate our anesthesiologists and other team members, we compared the first temperatures obtained in the recovery unit prior to the start of the intervention with those collected after the start of the QI project in November 2018. Because of the variability of temperature monitoring intraoperatively (nasal, axillary, rectal), we decided to use the temperature obtained by the nurse in the recovery room upon the patient’s arrival. Over the years analyzed, the nurse’s technique of measuring the temperature remained consistent. All patient temperature measurements were performed using the TAT-5000 (Exergen Corporation). This temporal artery thermometer has been previously shown to correlate well with bladder temperatures (70% of measurements differ by no more than 0.5 °C, as reported by Langham et al16).

Admittedly, we could not measure the degree of motivation or internalization of the project goals by our cohort, but we could measure the reduction in the rate of hypothermia and subjectively gauge engagement in the project by the various groups of participants and the sustainability of the results. In addition, all participating anesthesiologists received MOCA Part 4 credits in July 2019. We continued our data collection until April 2021 to determine if our project had brought about sustainable changes in practice that would continue past the initial motivator of obtaining CME credit.

Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft) and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

The median of the monthly percentage of patients with a temperature of less than 36.0 °C was also determined for the preintervention time frame. This served as our baseline hypothermia rate, and we aimed to lower it by 50%. Run charts, a well-described methodology to gauge the effectiveness of the QI project, were constructed with the collected data.17

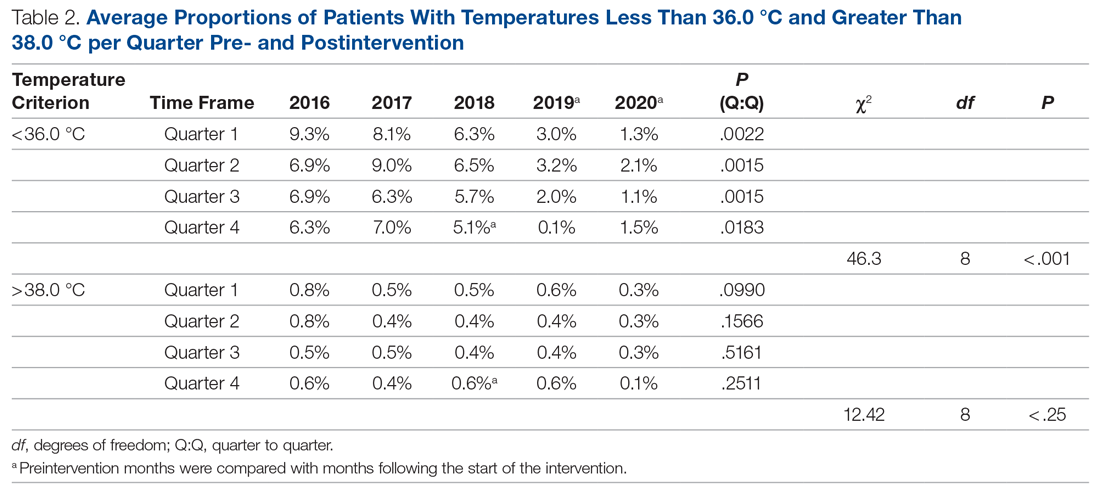

We performed additional analysis to adjust for different time periods throughout the year. The time period between January 2016 and October 2018 was considered preintervention. We considered November 2018 the start of our intervention, or more specifically, the start of our PDSA cycles. October 2018 was analyzed as part of the preintervention data. To account for seasonal temperature variations, the statistical analysis focused on the comparisons of the same calendar quarters for before and after starting intervention using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U tests. To reach an overall conclusion, the probabilities for the 4 quarters were combined for each criterion separately utilizing the Fisher χ2 combined probability method.

The hypothermia QI project was reviewed by the institutional review board and determined to be exempt.

Results

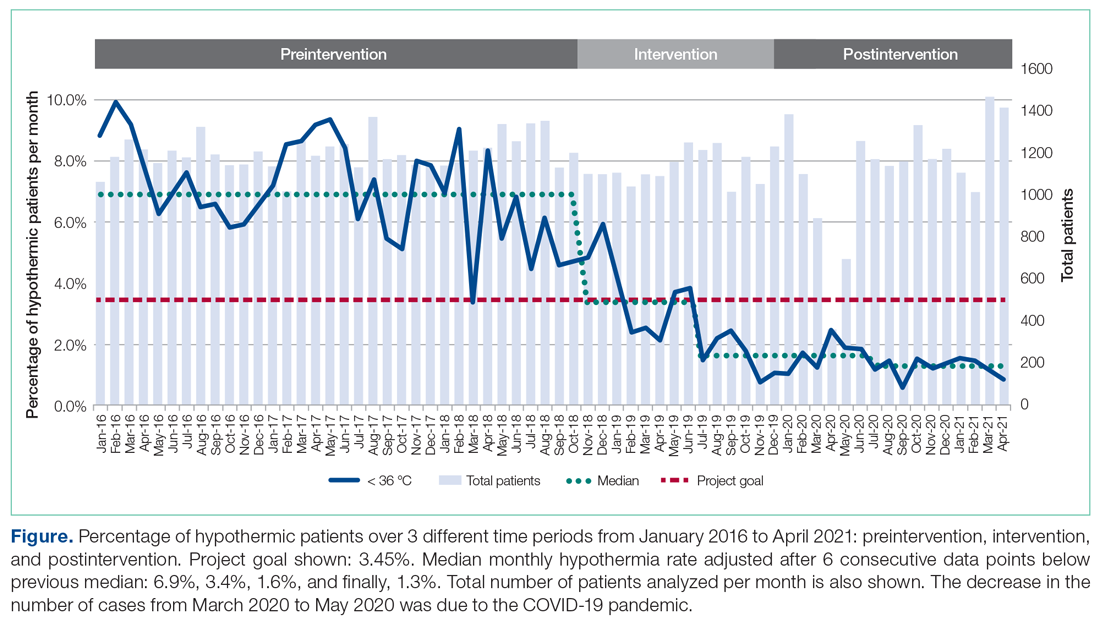

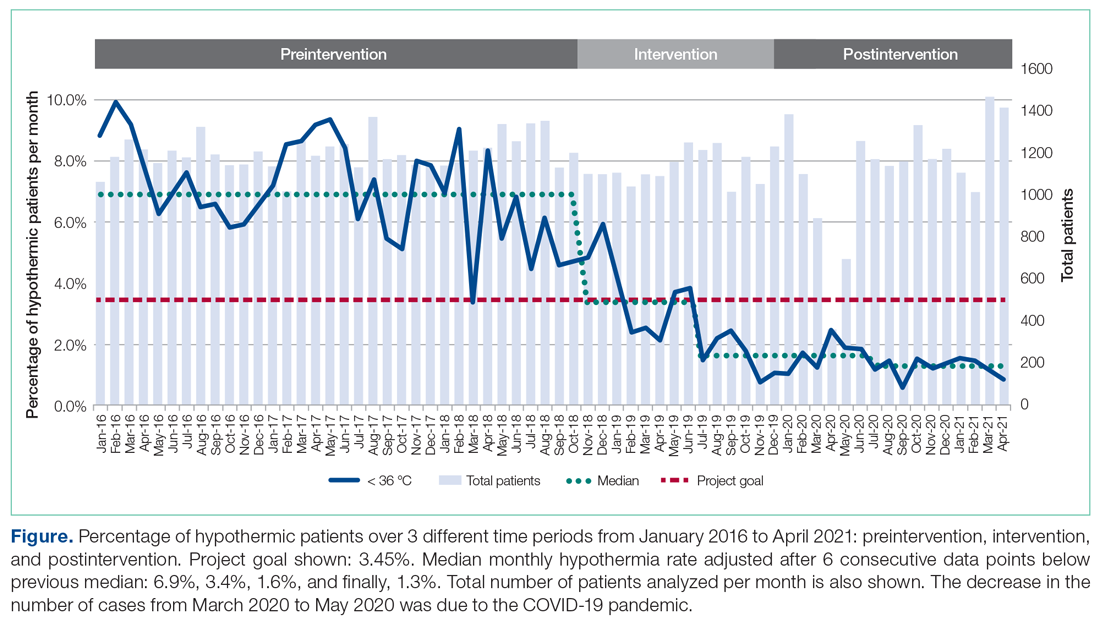

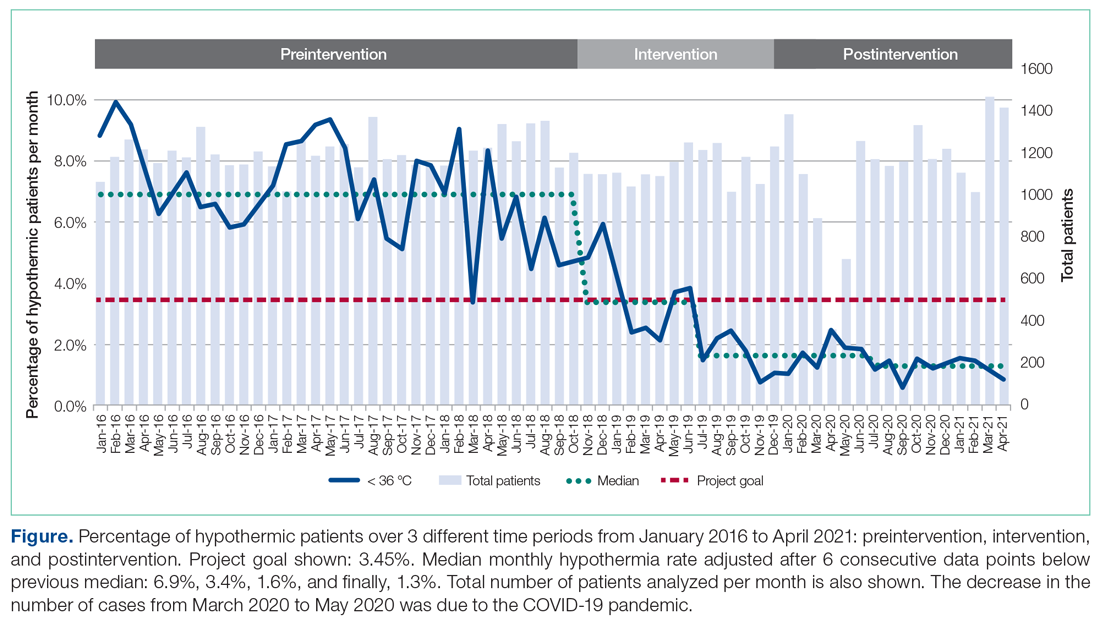

The temperatures of 40 875 patients were available for analysis for the preintervention period between January 2016 and October 2018. The median percentage of patients with temperatures less than 36.0 °C was 6.9% (interquartile range [IQR], 5.8%-8.4%). The highest percentage was in February 2016 (9.9%), and the lowest was in March 2018 (3.4%). Following the start of the first PDSA cycle, the next 6 consecutive rates of hypothermia were below the median preintervention value, and a new median for these percentages was calculated at 3.4% (IQR, 2.6%-4.3%). In July 2019, the proportion of hypothermic patients decreased once more for 6 consecutive months, yielding a new median of 1.6% (IQR, 1.2%-1.8%) and again in July 2020, to yield a median of 1.3% (IQR, 1.2%-1.5%) (Figure). In all, 33 799 patients were analyzed after the start of the project from November 2018 to the end of the data collection period through April 2021.

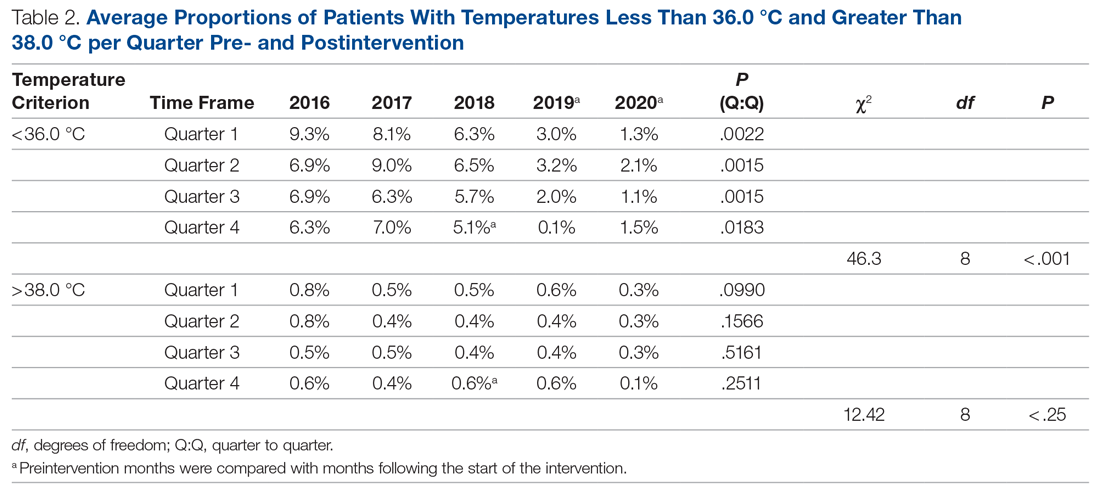

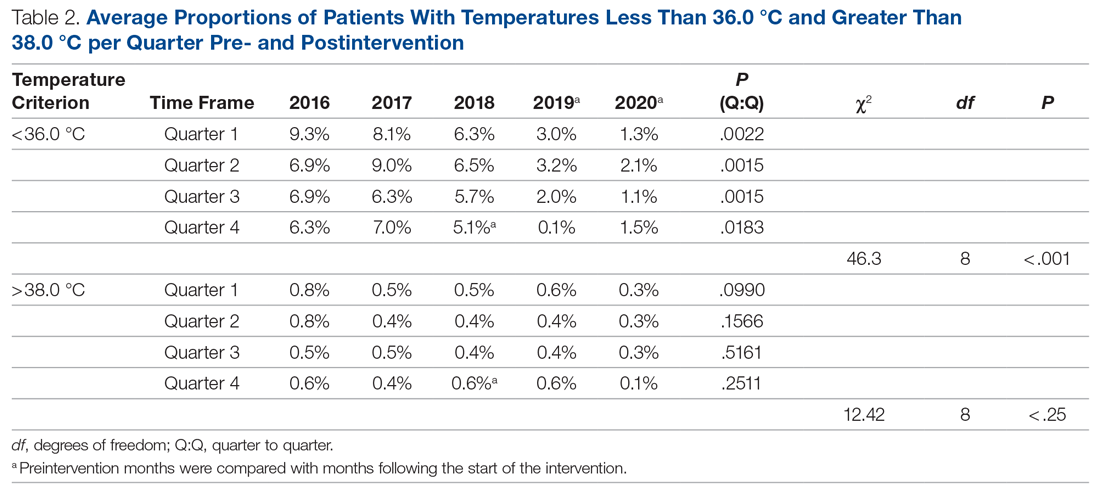

The preintervention monthly rates of hypothermia were compared, quarter to quarter, with those starting in November 2018 using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test. The decrease in proportion of hypothermic patients after the start of the intervention was statistically significant (P < .001). In addition, the percentage of patients with temperatures greater than 38 °C was not significantly different between the pre- and postintervention time periods (P < .25) (Table 2). The decrease in the number of patients available for analysis from March 2020 to May 2020 was due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Subjectively, we did not experience any notable resistance to our efforts, and the experience was largely positive for everyone involved. Clinicians identified as having high monthly rates of hypothermia (5% or higher) corrected their numbers the following month after being notified via email or in person.

Discussion

To achieve changes in practice, the health care industry has relied on instituting guidelines, regulations, and policies, often with punitive consequences. We call into question this long-standing framework and propose a novel approach to help evolve the field of QI. Studies in human psychology have long demonstrated the demotivation power of a reward system and the negative response to attempts by authority to use incentives to control or coerce. In our QI project, we instituted 3 PDSA cycles and applied elements from SDT to motivate people’s behaviors. We demonstrate how a new culture focused on maintaining intraoperative normothermia was developed and brought about a measurable and significant decrease in the rate of hypothermia. The relevance of SDT, a widely accepted unifying theory that bridges and links social and personality psychology, should not be understated in health care. Authorities wishing to have long-standing influence should consider a person’s right to make their own decisions and, if possible, a unique way of doing things.

Positively reinforcing behavior has been shown to have a paradoxical effect by dampening an individual’s intrinsic motivation or desire to perform certain tasks.18 Deadlines, surveillance, and authoritative commands are also deterrents.19,20 We focused on providing the tools and information to the clinicians and relied on their innate need for autonomy, growth, and self-actualization to bring about change in clinical practice.21 Group meetings served as a construct for exchanging ideas and to encourage participation, but without the implementation of rigid guidelines or policies. Intraoperative active warming devices and temperature probes were made available, but their use was not mandated. The use of these devices was intentionally not audited to avoid any overbearing control. Providers were, however, given monthly temperature data to help individually assess the effectiveness of their interventions. We did not impose any negative or punitive actions for those clinicians who had high rates of hypothermic patients, and we did not reward those who had low rates of hypothermia. We wanted the participants to feel that the inner self was the source of their behavior, and this was in parallel with their own interests and values. If providers could feel their need for competency could be realized, we hoped they would continue to adhere to the measures we provided to maintain a low rate of hypothermia.

The effectiveness of our efforts was demonstrated by a decrease in the prevalence of postoperative hypothermia in our surgical patients. The initial decrease of the median rate of hypothermia from 6.9% to 3.4% occurred shortly into the start of the first PDSA cycle. The second PDSA cycle started in January 2019 with a multimodal approach and included almost all parties involved in the perioperative care of our surgical patients. Not only was this intervention responsible for a continued downward trend in the percentage of hypothermic patients, but it set the stage for the third and final PDSA cycle, which started in July 2019. The architecture was in place to integrate trainees and APPs to reinforce our initiative. Subsequently, the new median percentage of hypothermic patients was further decreased to an all-time low of 1.6% per month, satisfying and surpassing the goal of the QI project of decreasing the rate of hypothermia by only 50%. Our organization thereafter maintained a monthly hypothermia rate below 2%, except for April 2020, when it reached 2.5%. Our lowest median percentage was obtained after July 2020, reaching 1.3%.

To account for seasonal variations in temperatures and types of surgeries performed, we compared the percentage of hypothermic patients before and after the start of intervention, quarter by quarter. The decrease in the proportion of hypothermic patients after the start of intervention was statistically significant (P < .001). In addition, the data failed to prove any statistical difference for temperatures above 38 °C between the 2 periods, indicating that our interventions did not result in significant overwarming of patients. The clinical implications of decreasing the percentage of hypothermic patients from 6.9% to 1.3% is likely clinically important when considering the large number of patients who undergo surgery at large tertiary care pediatric centers. Even if simple interventions reduce hypothermia in only a handful of patients, routine applications of simple measures to keep patients normothermic is likely best clinical practice.

Anesthesiologists who participated in the hypothermia QI project by tracking the incidence of hypothermia in their patients were able to collect MOCA Part 4 credits in July 2019. There was no requirement for the individual anesthesiologist to reduce the rate of hypothermia or apply any of the encouraged strategies to obtain credit. As previously stated, there were also no rewards for obtaining low hypothermia rates for the providers. The temperature data continued to be collected through April 2021, 21 months after the credits were distributed, to demonstrate a continued, meaningful change, at least in the short-term. While the MOCA Part 4 credits likely served as an initial motivating factor to encourage participation in the QI project, they certainly were not responsible for the sustained low hypothermia rate after July 2019. We showed that the low rate of hypothermia was successfully maintained, indicating that the change in providers’ behavior was independent of the external motivator of obtaining the credit hours. Mere participation in the project by reviewing one’s temperature data was all that was required to obtain the credit. The Organismic Integration Theory, a mini-theory within SDT, best explains this phenomenon by describing any motivated behavior on a continuum ranging from controlled to autonomous.22 Do people perform the task resentfully, on their own volition because they believe it is the correct action, or somewhere in between? We explain the sustained low rates of hypothermia after the MOCA credits were distributed due to a shift to the autonomous end of the continuum with the clinician’s active willingness to meet the challenges and apply intrinsically motivated behaviors to lower the rate of hypothermia. The internalization of external motivators is difficult to prove, but the evidence supports that the methods we used to motivate individuals were effective and have resulted in a significant downward trend in our hypothermia rate.

There are several limitations to our QI project. The first involves the measuring of postoperative temperature in the recovery units. The temperatures were obtained using the same medical-grade infrared thermometer for all the patients, but other variables, such as timing and techniques, were not standardized. Secondly, overall surgical outcomes related to hypothermia were not tracked because we were unable to control for other confounding variables in our large cohort of patients, so we cannot say if the drop in the hypothermia rate had a clinically significant outcome. Thirdly, we propose that SDT offers a compellingly fitting explanation of the psychology of motivation in our efforts, but it may be possible that other theories may offer equally fitting explanations. The ability to measure the degree of motivation is lacking, and we did not explicitly ask participants what their specific source of motivation was. Aside from SDT, the reduction in hypothermia rate could also be attributed to the ease and availability of warming equipment that was made in each OR. This QI project was successfully applied to only 1 institution, so its ability to be widely applicable remains uncertain. In addition, data collection continued during the COVID-19 pandemic when case volumes decreased. However, by June 2020, the number of surgical cases at our institution had largely returned to prepandemic levels. Additional data collection beyond April 2021 would be helpful to determine if the reduction in hypothermia rates is truly sustained.

Conclusion

Overall, the importance of maintaining perioperative normothermia was well disseminated and agreed upon by all departments involved. Despite the limitations of the project, there was a significant reduction in rates of hypothermia, and sustainability of outcomes was consistently demonstrated in the poststudy period.

Using 3 cycles of the PDSA method, we successfully decreased the median rate of postoperative hypothermia in our pediatric surgical population from a preintervention value of 6.9% to 1.3%—a reduction of more than 81.2%. We provided motivation for members of our anesthesiology staff to participate by offering MOCA 2.0 Part 4 credits, but the lower rate of hypothermic patients was maintained for 15 months after the credits were distributed. Over the course of the project, there was a shift in culture, and extra vigilance was given to temperature monitoring and assessment. We attribute this sustained cultural change to the deliberate incorporation of the principles of competency, autonomy, and relatedness central to SDT to the structure of the interventions, avoiding rigid guidelines and pathways in favor of affective engagement to establish intrinsic motivation.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Joan Reisch, PhD, for her assistance with the statistical analysis.

Corresponding author: Edgar Erold Kiss, MD, 1935 Medical District Dr, Dallas, TX 75235; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Leslie K, Sessler DI. Perioperative hypothermia in the high-risk surgical patient. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(4):485-498.

2. Sessler DI. Forced-air warming in infants and children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(6):467-468.

3. Wetzel RC. Evaluation of children. In: Longnecker DE, Tinker JH, Morgan Jr GE, eds. Principles and Practice of Anesthesiology. 2nd ed. Mosby Publishers; 1999:445-447.

4. Witt L, Dennhardt N, Eich C, et al. Prevention of intraoperative hypothermia in neonates and infants: results of a prospective multicenter observational study with a new forced-air warming system with increased warm air flow. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(6):469-474.

5. Blum R, Cote C. Pediatric equipment. In: Blum R, Cote C, eds. A Practice of Anaesthesia for Infants and Children. Saunders Elsevier; 2009:1099-1101.

6. Doufas AG. Consequences of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(4):535-549.

7. Mahoney CB, Odom J. Maintaining intraoperative normothermia: a meta-analysis of outcomes with costs. AANA J. 1999;67(2):155-163.

8. American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Standards for Basic Anesthetic Monitoring. Approved by the ASA House of Delegates October 21, 1986; last amended October 20, 2010; last affirmed October 28, 2015.

9. Horn E-P, Bein B, Böhm R, et al. The effect of short time periods of pre-operative warming in the prevention of peri-operative hypothermia. Anaesthesia. 2012;67(6):612-617.

10. Andrzejowski J, Hoyle J, Eapen G, Turnbull D. Effect of prewarming on post-induction core temperature and the incidence of inadvertent perioperative hypothermia in patients undergoing general anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(5):627-631.

11. Sessler DI. Complications and treatment of mild hypothermia. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(2):531-543.

12. Bräuer A, English MJM, Steinmetz N, et al. Efficacy of forced-air warming systems with full body blankets. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54(1):34-41.

13. Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self‐determination of behavior. Psychol Inquiry. 2000;11(4):227-268.

14. Al-Shamari M, Puttha R, Yuen S, et al. G9 Can introduction of a hypothermia bundle reduce hypothermia in the newborns? Arch Dis Childhood. 2019;104(suppl 2):A4.1-A4.

15. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. How to improve. Accessed May 12, 2021. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

16. Langham GE, Meheshwari A, You J, et al. Noninvasive temperature monitoring in postanesthesia care units. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(1):90-96.

17. Perla RJ, Provost LP, Murray SK. The run chart: a simple analytical tool for learning from variation in healthcare processes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(1):46-51.

18. Deci EL. Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1971;18(1):105-115.

19. Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM. A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(6):627-668.

20. Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM. The undermining effect is a reality after all—extrinsic rewards, task interest, and self-determination: Reply to Eisenberger, Pierce, and Cameron (1999) and Lepper, Henderlong, and Gingras (1999). Psychol Bull. 1999;125(6):692-700.

21. Maslow A. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. Viking Press; 1971.

22. Sheldon KM, Prentice M. Self-determination theory as a foundation for personality researchers. J Pers. 2019;87(1):5-14.

From Children’s Health System of Texas, Division of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Dallas, TX (Drs. Sakhai, Bocanegra, Chandran, Kimatian, and Kiss), UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, Dallas, TX (Drs. Bocanegra, Chandran, Kimatian, and Kiss), and UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Population and Data Sciences, Dallas, TX (Dr. Reisch).

Objective: Policy-driven changes in medical practice have long been the norm. Seldom are changes in clinical practice sought to be brought about by a person’s tendency toward growth or self‐actualization. Many hospitals have instituted hypothermia bundles to help reduce the incidence of unanticipated postoperative hypothermia. Although successful in the short-term, sustained changes are difficult to maintain. We implemented a quality-improvement project focused on addressing the affective components of self-determination theory (SDT) to create sustainable behavioral change while satisfying providers’ basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Methods: A total of 3 Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were enacted over the span of 14 months at a major tertiary care pediatric hospital to recruit and motivate anesthesia providers and perioperative team members to reduce the percentage of hypothermic postsurgical patients by 50%. As an optional initial incentive for participation, anesthesiologists would qualify for American Board of Anesthesiology Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) Part 4 Quality Improvement credits for monitoring their own temperature data and participating in project-related meetings. Providers were given autonomy to develop a personal plan for achieving the desired goals.

Results: The median rate of hypothermia was reduced from 6.9% to 1.6% in July 2019 and was reduced again in July 2020 to 1.3%, an 81% reduction overall. A low hypothermia rate was successfully maintained for at least 21 subsequent months after participants received their MOCA credits in July 2019.

Conclusions: Using an approach that focused on the elements of competency, autonomy, and relatedness central to the principles of SDT, we observed the development of a new culture of vigilance for prevention of hypothermia that successfully endured beyond the project end date.

Keywords: postoperative hypothermia; self-determination theory; motivation; quality improvement.

Perioperative hypothermia, generally accepted as a core temperature less than 36 °C in clinical practice, is a common complication in the pediatric surgical population and is associated with poor postoperative outcomes.1 Hypothermic patients may develop respiratory depression, hypoglycemia, and metabolic acidosis that may lead to decreased oxygen delivery and end organ tissue hypoxia.2-4 Other potential detrimental effects of failing to maintain normal body temperature are impaired clotting factor enzyme function and platelet dysfunction, increasing the risk for postoperative bleeding.5,6 In addition, there are financial implications when hypothermic patients require care and resources postoperatively because of delayed emergence or shivering.7

The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends intraoperative temperature monitoring for procedures when clinically significant changes in body temperature are anticipated.8 Maintenance of normothermia in the pediatric population is especially challenging owing to a larger skin-surface area compared with body mass ratio and less subcutaneous fat content than in adults. Preventing postoperative hypothermia starts preoperatively with parental education and can be as simple as covering the child with a blanket and setting the preoperative room to an acceptably warm temperature.9,10 Intraoperatively, maintaining operating room (OR) temperatures at or above 21.1 °C and using active warming devices and radiant warmers when appropriate are important techniques to preserve the child’s body temperature.11,12

Despite the knowledge of these risks and vigilant avoidance of hypothermia, unplanned perioperative hypothermia can occur in up to 70% of surgical patients.1 Beyond the clinical benefits, as health care marches toward a value-based payment methodology, quality indicators such as avoiding hypothermia may be linked directly to payment.

Self-determination theory (SDT) was first developed in 1980 by Deci and Ryan.13 The central premise of the theory states that people develop their full potential if circumstances allow them to satisfy their basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Under these conditions, people’s natural inclination toward growth can be realized, and they are more likely to internalize external goals. Under an extrinsic reward system, motivation can waver, as people may perceive rewards as controlling.

Many institutions have implemented hypothermia bundles to help decrease the rate of hypothermic patients, but while initially successful, the effectiveness of these interventions tends to fade over time as participants settle into old, comfortable routines.14 With SDT in mind, we designed our quality-improvement (QI) project with interventions to allow clinicians autonomy without instituting rigid guidelines or punitive actions. We aimed to directly address the affective components central to motivation and engagement so that we could bring about long-term meaningful changes in our practice.

Methods

Setting

The hypothermia QI intervention was instituted at a major tertiary care children’s hospital that performs more than 40 000 pediatric general anesthetics annually. Our division of pediatric anesthesiology consists of 66 fellowship-trained pediatric anesthesiologists, 15 or more rotating trainees per month, 13 anesthesiology assistants, 15 anesthesia technicians, and more than 50 perioperative nurses.

The most frequent pediatric surgeries include, but are not limited to, general surgery, otolaryngology, urology, gastroenterology, plastic surgery, neurosurgery, and dentistry. The surgeries are conducted in the hospital’s main operative floor, which consists of 15 ORs and 2 gastroenterology procedure rooms. Although the implementation of the QI project included several operating sites, we focused on collecting temperature data from surgical patients at our main campus recovery unit. We obtained the patients’ initial temperatures upon arrival to the recovery unit from a retrospective electronic health record review of all patients who underwent anesthesia from January 2016 through April 2021.

Postoperative hypothermia was identified as an area of potential improvement after several patients were reported to be hypothermic upon arrival to the recovery unit in the later part of 2018. Further review revealed significant heterogeneity of practices and lack of standardization of patient-warming methods. By comparing the temperatures pre- and postintervention, we could measure the effectiveness of the QI initiative. Prior to the start of our project, the hypothermia rate in our patient population was not actively tracked, and the effectiveness of our variable practice was not measured.

The cutoff for hypothermia for our QI project was defined as body temperature below 36 °C, since this value has been previously used in the literature and is commonly accepted in anesthesia practice as the delineation for hypothermia in patients undergoing general anesthesia.1

Interventions

This QI project was designed and modeled after the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement.15 Three cycles of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) were developed and instituted over a 14-month period until December 2019 (Table 1).

A retrospective review was conducted to determine the percentage of surgical patients arriving to our recovery units with an initial temperature reading of less than 36 °C. A project key driver diagram and smart aim were created and approved by the hospital’s continuing medical education (CME) committee for credit via the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Multi-Specialty Portfolio Program, Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) Part 4.

The first PDSA cycle involved introducing the QI project and sharing the aims of the project at a department grand rounds in the latter part of October 2018. Enrollment to participate in the project was open to all anesthesiologists in the division, and participants could earn up to 20 hours of MOCA Part 4 credits. A spreadsheet was developed and maintained to track each anesthesiologist’s monthly percentage of hypothermic patients. The de-identified patient data were shared with the division via monthly emails. In addition, individual providers with a hypothermic patient in the recovery room received a notification email.

The anesthesiologists participated in the QI project by reviewing their personal percentage of hypothermic patients on an ongoing basis to earn the credit. There was no explicit requirement to decrease their own rate of patients with body temperature less than 36 °C or expectation to achieve a predetermined goal, so the participants could not “fail.”

Because of the large interest in this project, a hypothermia committee was formed that consisted of 36 anesthesiologists. This group reviewed the data and exchanged ideas for improvement in November 2018 as part of the first PDSA cycle. The committee met monthly and was responsible for actively engaging other members of the department and perioperative staff to help in this multidisciplinary effort of combating hypothermia in our surgical pediatric population.

PDSA cycle 2 involved several major initiatives, including direct incorporation of the rest of the perioperative team. The perioperative nursing team was educated on the risks of hypothermia and engaged to take an active role by maintaining the operating suite temperature at 21.1 °C and turning on the Bair Hugger (3M) blanket to 43 °C on the OR bed prior to patient arrival to the OR. Additionally, anesthesia technicians (ATs) were tasked with ensuring an adequate supply of Bair Hugger drapes for all cases of the day. The facility’s engineering team was engaged to move the preoperative room temperature controls away from families (who frequently made the rooms cold) and instead set it at a consistent temperature of 23.9 °C. ATs were also asked to place axillary and nasal temperature probes on the anesthesia workstations as a visual reminder to facilitate temperature monitoring closer to the start of anesthesia (instead of the anesthesia provider having to remember to retrieve a temperature probe out of a drawer and place it on the patient). Furthermore, anesthesiologists were instructed via the aforementioned monthly emails and at monthly department meetings to place the temperature probes as early as possible in order to recognize and respond to intraoperative hypothermia in a timelier manner. Finally, supply chain leaders were informed of our expected increase in the use of the blankets and probes and proportionally increased ordering of these supplies to make sure availability would not present an obstacle.

In PDSA cycle 3, trainees (anesthesia assistant students, anesthesia residents and fellows) and advanced practice providers (APPs) (certified registered nurse-anesthetists [CRNAs] and certified anesthesia assistants [C-AAs]) were informed of the QI project. This initiative was guided toward improving vigilance for hypothermia in the rest of the anesthesia team members. The trainees and APPs usually set up the anesthesia area prior to patient arrival, so their recruitment in support of this effort would ensure appropriate OR temperature, active warming device deployment, and the availability and early placement of the correct temperature probe for the case. To facilitate personal accountability, the trainees and APPs were also emailed their own patients’ rate of hypothermia.

Along the course of the project, quarterly committee meetings and departmental monthly meetings served as venues to express concerns and look for areas of improvement, such as specific patterns or trends leading to hypothermic patients. One specific example was the identification of the gastrointestinal endoscopic patients having a rate of hypothermia that was 2% higher than average. Directed education on the importance of Bair Hugger blankets and using warm intravenous fluids worked well to decrease the rate of hypothermia in these patients. This collection of data was shared at regular intervals during monthly department meetings as well and more frequently using departmental emails. The hospital’s secure intranet SharePoint (Microsoft) site was used to share the data among providers.

Study of the interventions and measures

To study the effectiveness and impact of the project to motivate our anesthesiologists and other team members, we compared the first temperatures obtained in the recovery unit prior to the start of the intervention with those collected after the start of the QI project in November 2018. Because of the variability of temperature monitoring intraoperatively (nasal, axillary, rectal), we decided to use the temperature obtained by the nurse in the recovery room upon the patient’s arrival. Over the years analyzed, the nurse’s technique of measuring the temperature remained consistent. All patient temperature measurements were performed using the TAT-5000 (Exergen Corporation). This temporal artery thermometer has been previously shown to correlate well with bladder temperatures (70% of measurements differ by no more than 0.5 °C, as reported by Langham et al16).

Admittedly, we could not measure the degree of motivation or internalization of the project goals by our cohort, but we could measure the reduction in the rate of hypothermia and subjectively gauge engagement in the project by the various groups of participants and the sustainability of the results. In addition, all participating anesthesiologists received MOCA Part 4 credits in July 2019. We continued our data collection until April 2021 to determine if our project had brought about sustainable changes in practice that would continue past the initial motivator of obtaining CME credit.

Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft) and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

The median of the monthly percentage of patients with a temperature of less than 36.0 °C was also determined for the preintervention time frame. This served as our baseline hypothermia rate, and we aimed to lower it by 50%. Run charts, a well-described methodology to gauge the effectiveness of the QI project, were constructed with the collected data.17

We performed additional analysis to adjust for different time periods throughout the year. The time period between January 2016 and October 2018 was considered preintervention. We considered November 2018 the start of our intervention, or more specifically, the start of our PDSA cycles. October 2018 was analyzed as part of the preintervention data. To account for seasonal temperature variations, the statistical analysis focused on the comparisons of the same calendar quarters for before and after starting intervention using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U tests. To reach an overall conclusion, the probabilities for the 4 quarters were combined for each criterion separately utilizing the Fisher χ2 combined probability method.

The hypothermia QI project was reviewed by the institutional review board and determined to be exempt.

Results

The temperatures of 40 875 patients were available for analysis for the preintervention period between January 2016 and October 2018. The median percentage of patients with temperatures less than 36.0 °C was 6.9% (interquartile range [IQR], 5.8%-8.4%). The highest percentage was in February 2016 (9.9%), and the lowest was in March 2018 (3.4%). Following the start of the first PDSA cycle, the next 6 consecutive rates of hypothermia were below the median preintervention value, and a new median for these percentages was calculated at 3.4% (IQR, 2.6%-4.3%). In July 2019, the proportion of hypothermic patients decreased once more for 6 consecutive months, yielding a new median of 1.6% (IQR, 1.2%-1.8%) and again in July 2020, to yield a median of 1.3% (IQR, 1.2%-1.5%) (Figure). In all, 33 799 patients were analyzed after the start of the project from November 2018 to the end of the data collection period through April 2021.

The preintervention monthly rates of hypothermia were compared, quarter to quarter, with those starting in November 2018 using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test. The decrease in proportion of hypothermic patients after the start of the intervention was statistically significant (P < .001). In addition, the percentage of patients with temperatures greater than 38 °C was not significantly different between the pre- and postintervention time periods (P < .25) (Table 2). The decrease in the number of patients available for analysis from March 2020 to May 2020 was due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Subjectively, we did not experience any notable resistance to our efforts, and the experience was largely positive for everyone involved. Clinicians identified as having high monthly rates of hypothermia (5% or higher) corrected their numbers the following month after being notified via email or in person.

Discussion

To achieve changes in practice, the health care industry has relied on instituting guidelines, regulations, and policies, often with punitive consequences. We call into question this long-standing framework and propose a novel approach to help evolve the field of QI. Studies in human psychology have long demonstrated the demotivation power of a reward system and the negative response to attempts by authority to use incentives to control or coerce. In our QI project, we instituted 3 PDSA cycles and applied elements from SDT to motivate people’s behaviors. We demonstrate how a new culture focused on maintaining intraoperative normothermia was developed and brought about a measurable and significant decrease in the rate of hypothermia. The relevance of SDT, a widely accepted unifying theory that bridges and links social and personality psychology, should not be understated in health care. Authorities wishing to have long-standing influence should consider a person’s right to make their own decisions and, if possible, a unique way of doing things.

Positively reinforcing behavior has been shown to have a paradoxical effect by dampening an individual’s intrinsic motivation or desire to perform certain tasks.18 Deadlines, surveillance, and authoritative commands are also deterrents.19,20 We focused on providing the tools and information to the clinicians and relied on their innate need for autonomy, growth, and self-actualization to bring about change in clinical practice.21 Group meetings served as a construct for exchanging ideas and to encourage participation, but without the implementation of rigid guidelines or policies. Intraoperative active warming devices and temperature probes were made available, but their use was not mandated. The use of these devices was intentionally not audited to avoid any overbearing control. Providers were, however, given monthly temperature data to help individually assess the effectiveness of their interventions. We did not impose any negative or punitive actions for those clinicians who had high rates of hypothermic patients, and we did not reward those who had low rates of hypothermia. We wanted the participants to feel that the inner self was the source of their behavior, and this was in parallel with their own interests and values. If providers could feel their need for competency could be realized, we hoped they would continue to adhere to the measures we provided to maintain a low rate of hypothermia.

The effectiveness of our efforts was demonstrated by a decrease in the prevalence of postoperative hypothermia in our surgical patients. The initial decrease of the median rate of hypothermia from 6.9% to 3.4% occurred shortly into the start of the first PDSA cycle. The second PDSA cycle started in January 2019 with a multimodal approach and included almost all parties involved in the perioperative care of our surgical patients. Not only was this intervention responsible for a continued downward trend in the percentage of hypothermic patients, but it set the stage for the third and final PDSA cycle, which started in July 2019. The architecture was in place to integrate trainees and APPs to reinforce our initiative. Subsequently, the new median percentage of hypothermic patients was further decreased to an all-time low of 1.6% per month, satisfying and surpassing the goal of the QI project of decreasing the rate of hypothermia by only 50%. Our organization thereafter maintained a monthly hypothermia rate below 2%, except for April 2020, when it reached 2.5%. Our lowest median percentage was obtained after July 2020, reaching 1.3%.

To account for seasonal variations in temperatures and types of surgeries performed, we compared the percentage of hypothermic patients before and after the start of intervention, quarter by quarter. The decrease in the proportion of hypothermic patients after the start of intervention was statistically significant (P < .001). In addition, the data failed to prove any statistical difference for temperatures above 38 °C between the 2 periods, indicating that our interventions did not result in significant overwarming of patients. The clinical implications of decreasing the percentage of hypothermic patients from 6.9% to 1.3% is likely clinically important when considering the large number of patients who undergo surgery at large tertiary care pediatric centers. Even if simple interventions reduce hypothermia in only a handful of patients, routine applications of simple measures to keep patients normothermic is likely best clinical practice.

Anesthesiologists who participated in the hypothermia QI project by tracking the incidence of hypothermia in their patients were able to collect MOCA Part 4 credits in July 2019. There was no requirement for the individual anesthesiologist to reduce the rate of hypothermia or apply any of the encouraged strategies to obtain credit. As previously stated, there were also no rewards for obtaining low hypothermia rates for the providers. The temperature data continued to be collected through April 2021, 21 months after the credits were distributed, to demonstrate a continued, meaningful change, at least in the short-term. While the MOCA Part 4 credits likely served as an initial motivating factor to encourage participation in the QI project, they certainly were not responsible for the sustained low hypothermia rate after July 2019. We showed that the low rate of hypothermia was successfully maintained, indicating that the change in providers’ behavior was independent of the external motivator of obtaining the credit hours. Mere participation in the project by reviewing one’s temperature data was all that was required to obtain the credit. The Organismic Integration Theory, a mini-theory within SDT, best explains this phenomenon by describing any motivated behavior on a continuum ranging from controlled to autonomous.22 Do people perform the task resentfully, on their own volition because they believe it is the correct action, or somewhere in between? We explain the sustained low rates of hypothermia after the MOCA credits were distributed due to a shift to the autonomous end of the continuum with the clinician’s active willingness to meet the challenges and apply intrinsically motivated behaviors to lower the rate of hypothermia. The internalization of external motivators is difficult to prove, but the evidence supports that the methods we used to motivate individuals were effective and have resulted in a significant downward trend in our hypothermia rate.

There are several limitations to our QI project. The first involves the measuring of postoperative temperature in the recovery units. The temperatures were obtained using the same medical-grade infrared thermometer for all the patients, but other variables, such as timing and techniques, were not standardized. Secondly, overall surgical outcomes related to hypothermia were not tracked because we were unable to control for other confounding variables in our large cohort of patients, so we cannot say if the drop in the hypothermia rate had a clinically significant outcome. Thirdly, we propose that SDT offers a compellingly fitting explanation of the psychology of motivation in our efforts, but it may be possible that other theories may offer equally fitting explanations. The ability to measure the degree of motivation is lacking, and we did not explicitly ask participants what their specific source of motivation was. Aside from SDT, the reduction in hypothermia rate could also be attributed to the ease and availability of warming equipment that was made in each OR. This QI project was successfully applied to only 1 institution, so its ability to be widely applicable remains uncertain. In addition, data collection continued during the COVID-19 pandemic when case volumes decreased. However, by June 2020, the number of surgical cases at our institution had largely returned to prepandemic levels. Additional data collection beyond April 2021 would be helpful to determine if the reduction in hypothermia rates is truly sustained.

Conclusion

Overall, the importance of maintaining perioperative normothermia was well disseminated and agreed upon by all departments involved. Despite the limitations of the project, there was a significant reduction in rates of hypothermia, and sustainability of outcomes was consistently demonstrated in the poststudy period.

Using 3 cycles of the PDSA method, we successfully decreased the median rate of postoperative hypothermia in our pediatric surgical population from a preintervention value of 6.9% to 1.3%—a reduction of more than 81.2%. We provided motivation for members of our anesthesiology staff to participate by offering MOCA 2.0 Part 4 credits, but the lower rate of hypothermic patients was maintained for 15 months after the credits were distributed. Over the course of the project, there was a shift in culture, and extra vigilance was given to temperature monitoring and assessment. We attribute this sustained cultural change to the deliberate incorporation of the principles of competency, autonomy, and relatedness central to SDT to the structure of the interventions, avoiding rigid guidelines and pathways in favor of affective engagement to establish intrinsic motivation.

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Joan Reisch, PhD, for her assistance with the statistical analysis.

Corresponding author: Edgar Erold Kiss, MD, 1935 Medical District Dr, Dallas, TX 75235; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From Children’s Health System of Texas, Division of Pediatric Anesthesiology, Dallas, TX (Drs. Sakhai, Bocanegra, Chandran, Kimatian, and Kiss), UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Management, Dallas, TX (Drs. Bocanegra, Chandran, Kimatian, and Kiss), and UT Southwestern Medical Center, Department of Population and Data Sciences, Dallas, TX (Dr. Reisch).

Objective: Policy-driven changes in medical practice have long been the norm. Seldom are changes in clinical practice sought to be brought about by a person’s tendency toward growth or self‐actualization. Many hospitals have instituted hypothermia bundles to help reduce the incidence of unanticipated postoperative hypothermia. Although successful in the short-term, sustained changes are difficult to maintain. We implemented a quality-improvement project focused on addressing the affective components of self-determination theory (SDT) to create sustainable behavioral change while satisfying providers’ basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

Methods: A total of 3 Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were enacted over the span of 14 months at a major tertiary care pediatric hospital to recruit and motivate anesthesia providers and perioperative team members to reduce the percentage of hypothermic postsurgical patients by 50%. As an optional initial incentive for participation, anesthesiologists would qualify for American Board of Anesthesiology Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) Part 4 Quality Improvement credits for monitoring their own temperature data and participating in project-related meetings. Providers were given autonomy to develop a personal plan for achieving the desired goals.

Results: The median rate of hypothermia was reduced from 6.9% to 1.6% in July 2019 and was reduced again in July 2020 to 1.3%, an 81% reduction overall. A low hypothermia rate was successfully maintained for at least 21 subsequent months after participants received their MOCA credits in July 2019.

Conclusions: Using an approach that focused on the elements of competency, autonomy, and relatedness central to the principles of SDT, we observed the development of a new culture of vigilance for prevention of hypothermia that successfully endured beyond the project end date.

Keywords: postoperative hypothermia; self-determination theory; motivation; quality improvement.

Perioperative hypothermia, generally accepted as a core temperature less than 36 °C in clinical practice, is a common complication in the pediatric surgical population and is associated with poor postoperative outcomes.1 Hypothermic patients may develop respiratory depression, hypoglycemia, and metabolic acidosis that may lead to decreased oxygen delivery and end organ tissue hypoxia.2-4 Other potential detrimental effects of failing to maintain normal body temperature are impaired clotting factor enzyme function and platelet dysfunction, increasing the risk for postoperative bleeding.5,6 In addition, there are financial implications when hypothermic patients require care and resources postoperatively because of delayed emergence or shivering.7

The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends intraoperative temperature monitoring for procedures when clinically significant changes in body temperature are anticipated.8 Maintenance of normothermia in the pediatric population is especially challenging owing to a larger skin-surface area compared with body mass ratio and less subcutaneous fat content than in adults. Preventing postoperative hypothermia starts preoperatively with parental education and can be as simple as covering the child with a blanket and setting the preoperative room to an acceptably warm temperature.9,10 Intraoperatively, maintaining operating room (OR) temperatures at or above 21.1 °C and using active warming devices and radiant warmers when appropriate are important techniques to preserve the child’s body temperature.11,12

Despite the knowledge of these risks and vigilant avoidance of hypothermia, unplanned perioperative hypothermia can occur in up to 70% of surgical patients.1 Beyond the clinical benefits, as health care marches toward a value-based payment methodology, quality indicators such as avoiding hypothermia may be linked directly to payment.

Self-determination theory (SDT) was first developed in 1980 by Deci and Ryan.13 The central premise of the theory states that people develop their full potential if circumstances allow them to satisfy their basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Under these conditions, people’s natural inclination toward growth can be realized, and they are more likely to internalize external goals. Under an extrinsic reward system, motivation can waver, as people may perceive rewards as controlling.

Many institutions have implemented hypothermia bundles to help decrease the rate of hypothermic patients, but while initially successful, the effectiveness of these interventions tends to fade over time as participants settle into old, comfortable routines.14 With SDT in mind, we designed our quality-improvement (QI) project with interventions to allow clinicians autonomy without instituting rigid guidelines or punitive actions. We aimed to directly address the affective components central to motivation and engagement so that we could bring about long-term meaningful changes in our practice.

Methods

Setting

The hypothermia QI intervention was instituted at a major tertiary care children’s hospital that performs more than 40 000 pediatric general anesthetics annually. Our division of pediatric anesthesiology consists of 66 fellowship-trained pediatric anesthesiologists, 15 or more rotating trainees per month, 13 anesthesiology assistants, 15 anesthesia technicians, and more than 50 perioperative nurses.

The most frequent pediatric surgeries include, but are not limited to, general surgery, otolaryngology, urology, gastroenterology, plastic surgery, neurosurgery, and dentistry. The surgeries are conducted in the hospital’s main operative floor, which consists of 15 ORs and 2 gastroenterology procedure rooms. Although the implementation of the QI project included several operating sites, we focused on collecting temperature data from surgical patients at our main campus recovery unit. We obtained the patients’ initial temperatures upon arrival to the recovery unit from a retrospective electronic health record review of all patients who underwent anesthesia from January 2016 through April 2021.

Postoperative hypothermia was identified as an area of potential improvement after several patients were reported to be hypothermic upon arrival to the recovery unit in the later part of 2018. Further review revealed significant heterogeneity of practices and lack of standardization of patient-warming methods. By comparing the temperatures pre- and postintervention, we could measure the effectiveness of the QI initiative. Prior to the start of our project, the hypothermia rate in our patient population was not actively tracked, and the effectiveness of our variable practice was not measured.

The cutoff for hypothermia for our QI project was defined as body temperature below 36 °C, since this value has been previously used in the literature and is commonly accepted in anesthesia practice as the delineation for hypothermia in patients undergoing general anesthesia.1

Interventions

This QI project was designed and modeled after the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Model for Improvement.15 Three cycles of Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) were developed and instituted over a 14-month period until December 2019 (Table 1).

A retrospective review was conducted to determine the percentage of surgical patients arriving to our recovery units with an initial temperature reading of less than 36 °C. A project key driver diagram and smart aim were created and approved by the hospital’s continuing medical education (CME) committee for credit via the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) Multi-Specialty Portfolio Program, Maintenance of Certification in Anesthesiology (MOCA) Part 4.

The first PDSA cycle involved introducing the QI project and sharing the aims of the project at a department grand rounds in the latter part of October 2018. Enrollment to participate in the project was open to all anesthesiologists in the division, and participants could earn up to 20 hours of MOCA Part 4 credits. A spreadsheet was developed and maintained to track each anesthesiologist’s monthly percentage of hypothermic patients. The de-identified patient data were shared with the division via monthly emails. In addition, individual providers with a hypothermic patient in the recovery room received a notification email.

The anesthesiologists participated in the QI project by reviewing their personal percentage of hypothermic patients on an ongoing basis to earn the credit. There was no explicit requirement to decrease their own rate of patients with body temperature less than 36 °C or expectation to achieve a predetermined goal, so the participants could not “fail.”

Because of the large interest in this project, a hypothermia committee was formed that consisted of 36 anesthesiologists. This group reviewed the data and exchanged ideas for improvement in November 2018 as part of the first PDSA cycle. The committee met monthly and was responsible for actively engaging other members of the department and perioperative staff to help in this multidisciplinary effort of combating hypothermia in our surgical pediatric population.

PDSA cycle 2 involved several major initiatives, including direct incorporation of the rest of the perioperative team. The perioperative nursing team was educated on the risks of hypothermia and engaged to take an active role by maintaining the operating suite temperature at 21.1 °C and turning on the Bair Hugger (3M) blanket to 43 °C on the OR bed prior to patient arrival to the OR. Additionally, anesthesia technicians (ATs) were tasked with ensuring an adequate supply of Bair Hugger drapes for all cases of the day. The facility’s engineering team was engaged to move the preoperative room temperature controls away from families (who frequently made the rooms cold) and instead set it at a consistent temperature of 23.9 °C. ATs were also asked to place axillary and nasal temperature probes on the anesthesia workstations as a visual reminder to facilitate temperature monitoring closer to the start of anesthesia (instead of the anesthesia provider having to remember to retrieve a temperature probe out of a drawer and place it on the patient). Furthermore, anesthesiologists were instructed via the aforementioned monthly emails and at monthly department meetings to place the temperature probes as early as possible in order to recognize and respond to intraoperative hypothermia in a timelier manner. Finally, supply chain leaders were informed of our expected increase in the use of the blankets and probes and proportionally increased ordering of these supplies to make sure availability would not present an obstacle.

In PDSA cycle 3, trainees (anesthesia assistant students, anesthesia residents and fellows) and advanced practice providers (APPs) (certified registered nurse-anesthetists [CRNAs] and certified anesthesia assistants [C-AAs]) were informed of the QI project. This initiative was guided toward improving vigilance for hypothermia in the rest of the anesthesia team members. The trainees and APPs usually set up the anesthesia area prior to patient arrival, so their recruitment in support of this effort would ensure appropriate OR temperature, active warming device deployment, and the availability and early placement of the correct temperature probe for the case. To facilitate personal accountability, the trainees and APPs were also emailed their own patients’ rate of hypothermia.

Along the course of the project, quarterly committee meetings and departmental monthly meetings served as venues to express concerns and look for areas of improvement, such as specific patterns or trends leading to hypothermic patients. One specific example was the identification of the gastrointestinal endoscopic patients having a rate of hypothermia that was 2% higher than average. Directed education on the importance of Bair Hugger blankets and using warm intravenous fluids worked well to decrease the rate of hypothermia in these patients. This collection of data was shared at regular intervals during monthly department meetings as well and more frequently using departmental emails. The hospital’s secure intranet SharePoint (Microsoft) site was used to share the data among providers.

Study of the interventions and measures

To study the effectiveness and impact of the project to motivate our anesthesiologists and other team members, we compared the first temperatures obtained in the recovery unit prior to the start of the intervention with those collected after the start of the QI project in November 2018. Because of the variability of temperature monitoring intraoperatively (nasal, axillary, rectal), we decided to use the temperature obtained by the nurse in the recovery room upon the patient’s arrival. Over the years analyzed, the nurse’s technique of measuring the temperature remained consistent. All patient temperature measurements were performed using the TAT-5000 (Exergen Corporation). This temporal artery thermometer has been previously shown to correlate well with bladder temperatures (70% of measurements differ by no more than 0.5 °C, as reported by Langham et al16).

Admittedly, we could not measure the degree of motivation or internalization of the project goals by our cohort, but we could measure the reduction in the rate of hypothermia and subjectively gauge engagement in the project by the various groups of participants and the sustainability of the results. In addition, all participating anesthesiologists received MOCA Part 4 credits in July 2019. We continued our data collection until April 2021 to determine if our project had brought about sustainable changes in practice that would continue past the initial motivator of obtaining CME credit.

Analysis

Data analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft) and SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

The median of the monthly percentage of patients with a temperature of less than 36.0 °C was also determined for the preintervention time frame. This served as our baseline hypothermia rate, and we aimed to lower it by 50%. Run charts, a well-described methodology to gauge the effectiveness of the QI project, were constructed with the collected data.17

We performed additional analysis to adjust for different time periods throughout the year. The time period between January 2016 and October 2018 was considered preintervention. We considered November 2018 the start of our intervention, or more specifically, the start of our PDSA cycles. October 2018 was analyzed as part of the preintervention data. To account for seasonal temperature variations, the statistical analysis focused on the comparisons of the same calendar quarters for before and after starting intervention using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U tests. To reach an overall conclusion, the probabilities for the 4 quarters were combined for each criterion separately utilizing the Fisher χ2 combined probability method.

The hypothermia QI project was reviewed by the institutional review board and determined to be exempt.

Results

The temperatures of 40 875 patients were available for analysis for the preintervention period between January 2016 and October 2018. The median percentage of patients with temperatures less than 36.0 °C was 6.9% (interquartile range [IQR], 5.8%-8.4%). The highest percentage was in February 2016 (9.9%), and the lowest was in March 2018 (3.4%). Following the start of the first PDSA cycle, the next 6 consecutive rates of hypothermia were below the median preintervention value, and a new median for these percentages was calculated at 3.4% (IQR, 2.6%-4.3%). In July 2019, the proportion of hypothermic patients decreased once more for 6 consecutive months, yielding a new median of 1.6% (IQR, 1.2%-1.8%) and again in July 2020, to yield a median of 1.3% (IQR, 1.2%-1.5%) (Figure). In all, 33 799 patients were analyzed after the start of the project from November 2018 to the end of the data collection period through April 2021.

The preintervention monthly rates of hypothermia were compared, quarter to quarter, with those starting in November 2018 using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney U test. The decrease in proportion of hypothermic patients after the start of the intervention was statistically significant (P < .001). In addition, the percentage of patients with temperatures greater than 38 °C was not significantly different between the pre- and postintervention time periods (P < .25) (Table 2). The decrease in the number of patients available for analysis from March 2020 to May 2020 was due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Subjectively, we did not experience any notable resistance to our efforts, and the experience was largely positive for everyone involved. Clinicians identified as having high monthly rates of hypothermia (5% or higher) corrected their numbers the following month after being notified via email or in person.

Discussion

To achieve changes in practice, the health care industry has relied on instituting guidelines, regulations, and policies, often with punitive consequences. We call into question this long-standing framework and propose a novel approach to help evolve the field of QI. Studies in human psychology have long demonstrated the demotivation power of a reward system and the negative response to attempts by authority to use incentives to control or coerce. In our QI project, we instituted 3 PDSA cycles and applied elements from SDT to motivate people’s behaviors. We demonstrate how a new culture focused on maintaining intraoperative normothermia was developed and brought about a measurable and significant decrease in the rate of hypothermia. The relevance of SDT, a widely accepted unifying theory that bridges and links social and personality psychology, should not be understated in health care. Authorities wishing to have long-standing influence should consider a person’s right to make their own decisions and, if possible, a unique way of doing things.

Positively reinforcing behavior has been shown to have a paradoxical effect by dampening an individual’s intrinsic motivation or desire to perform certain tasks.18 Deadlines, surveillance, and authoritative commands are also deterrents.19,20 We focused on providing the tools and information to the clinicians and relied on their innate need for autonomy, growth, and self-actualization to bring about change in clinical practice.21 Group meetings served as a construct for exchanging ideas and to encourage participation, but without the implementation of rigid guidelines or policies. Intraoperative active warming devices and temperature probes were made available, but their use was not mandated. The use of these devices was intentionally not audited to avoid any overbearing control. Providers were, however, given monthly temperature data to help individually assess the effectiveness of their interventions. We did not impose any negative or punitive actions for those clinicians who had high rates of hypothermic patients, and we did not reward those who had low rates of hypothermia. We wanted the participants to feel that the inner self was the source of their behavior, and this was in parallel with their own interests and values. If providers could feel their need for competency could be realized, we hoped they would continue to adhere to the measures we provided to maintain a low rate of hypothermia.

The effectiveness of our efforts was demonstrated by a decrease in the prevalence of postoperative hypothermia in our surgical patients. The initial decrease of the median rate of hypothermia from 6.9% to 3.4% occurred shortly into the start of the first PDSA cycle. The second PDSA cycle started in January 2019 with a multimodal approach and included almost all parties involved in the perioperative care of our surgical patients. Not only was this intervention responsible for a continued downward trend in the percentage of hypothermic patients, but it set the stage for the third and final PDSA cycle, which started in July 2019. The architecture was in place to integrate trainees and APPs to reinforce our initiative. Subsequently, the new median percentage of hypothermic patients was further decreased to an all-time low of 1.6% per month, satisfying and surpassing the goal of the QI project of decreasing the rate of hypothermia by only 50%. Our organization thereafter maintained a monthly hypothermia rate below 2%, except for April 2020, when it reached 2.5%. Our lowest median percentage was obtained after July 2020, reaching 1.3%.