User login

Patch testing in children: An evolving science

“Time needs to be allocated for a patch test consultation, placement, removal, and reading,” she said at the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “You will need more time in the day that you’re reading the patch test for patient education. However, your staff will need more time on the front end of the patch test process for application. Also, if they are customizing patch tests, they’ll need time to make the patch tests along with access to a refrigerator and plenty of counter space.”

Other factors to consider are the site of service, your payer mix, and if you need to complete prior authorizations for patch testing.

Dr. Martin, associate professor of dermatology and child health at the University of Missouri–Columbia, said that the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) crosses her mind when she sees a patient with new dermatitis, especially in an older child; if the dermatitis is patterned or regional; if there’s exacerbation of an underlying, previously stable skin disease; or if it’s a pattern known to be associated with systemic contact dermatitis. “In fact, 13%-25% of healthy, asymptomatic kids have allergen sensitization,” she said. “If you take that a step further and look at kids who are suspected of having allergic contact dermatitis, 25%-96% have allergen sensitization. Still, that doesn’t mean that those tests are relevant to the dermatitis that’s going on. If you take kids who are referred to tertiary centers for patch testing, about half will have relevant patch test results.”

Pediatric ACD differs from adult ACD in three ways, Dr. Martin said. First, children have a different clinical morphology and distribution on presentation, compared with adults. “In adults, the most common clinical presentation is hand dermatitis, while kids more often present with a scattered generalized morphology of dermatitis,” she said. “This occurs in about one-third of children with ACD. Their patterns of allergen exposure are also different. For the most part, adults are in control of their own environments and what is placed on their skin, whereas kids are not. When thinking about what you might need to patch test a child to if you’re considering ACD, it’s important to think about not only what the parent or caregiver puts directly on the child’s skin but also any connubial or consort allergen exposure – the most common ones coming from the caregivers themselves, such as fragrance or hair dyes that are transferred to a young child.”

The third factor that differs between pediatric and adult ACD is the allergen source. Dr. Martin noted that children and adults use different personal care products, wear different types of clothing, and spend different amounts of time in play versus work. “Children have many more hobbies in general that are unfortunately lost as many of us age,” she said. That means “thinking through the child’s entire day and how the seasons differ for them, such as what sports they’re in and what protective equipment may be involved with where their dermatitis is, or what musical instruments they play.”

Applying the T.R.U.E. patch test panel or a customized patch test panel to young children poses certain challenges, considering their limited body surface area and propensity to squirm. Dr. Martin often employs distraction techniques when placing patches on young patients, including the use of bubbles, music, movies, and games. “The goal is always to get as much of the patches on the back or the flanks as possible,” she said. “If you need additional space you can use the upper outer arms, the abdomen, or the anterior lateral thighs. Another thing to consider is how to set up your week for pediatric patch testing. There’s a standardized process for adults where we place the patches on day 0, read them on day 2, with removal of the patches at that time, and then perform a delayed read between day 4-7.”

The process is similar for postpubescent children, despite the lack of clear guidelines in the medical literature. “There is much controversy and different practices between different pediatric patch test centers,” Dr. Martin said. “There is more consensus between the older kids and the prepubescent group ages 6-12. Most clinicians will still do a similar placement on day 0 with removal and initial read on day 2, with a delayed read on day 4-7. However, some groups will remove patches at 24 hours, especially in those with atopic dermatitis (AD) or a generalized dermatitis, to reduce irritant reactions. Others will also use half-strength concentrations of allergens.”

The most controversy lies with children younger than 6 years, she said. For those aged 3-6 years, who do not have AD, most practices use a standardized pediatric tray with a 24- to 48-hour contact time. However, patch testing can be “very challenging” for children who are under 3 years of age, and children with AD who are under 6 years, “so there needs to be a very high degree of suspicion for ACD and very careful selection of the allergens and contact time that is used in those particular cases,” she noted.

The most common allergens in children are nickel, fragrance mix I, cobalt, balsam of Peru, neomycin, and bacitracin, which largely match the common allergens seen in adults. However, allergens more common in children, compared with adults, include gold, propylene glycol, 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, and cocamidopropyl betaine. “If the child presents with a regional dermatitis or a patterned dermatitis, sometimes you can hone in on your suspected allergens and only test for a few,” Dr. Martin said. “In a child with eyelid dermatitis, you’re going to worry more about cocamidopropyl betaine in their shampoos and cleansers. Also, a metal allergen could be transferred from their hands from toys or coins, specifically nickel and cobalt. They also may have different sports gear such as goggles that may be affecting their eyelid dermatitis, which you would not necessarily see in an adult.”

Periorificial contact dermatitis can also differ in presentation between children and adults. “In kids, think about musical instruments, flavored lip balms, gum, and pacifiers,” she said. “For ACD on the buttocks and posterior thighs, think about toilet seat allergens, especially those in the potty training ages, and the nickel bolts on school chairs.”

In 2018, Dr. Martin and her colleagues on the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup published a pediatric baseline patch test series as a way to expand on the T.R.U.E. test (Dermatitis. 2018;29[4]:206-12). “It’s nice to have this panel available as a baseline screening tool when you’re unsure of possible triggers of the dermatitis but you still have high suspicion of allergic dermatitis,” Dr. Martin said. “This also is helpful for patients who present with generalized dermatitis. It’s still not perfect. We are collecting prospective data to fine-tune this baseline series.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

“Time needs to be allocated for a patch test consultation, placement, removal, and reading,” she said at the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “You will need more time in the day that you’re reading the patch test for patient education. However, your staff will need more time on the front end of the patch test process for application. Also, if they are customizing patch tests, they’ll need time to make the patch tests along with access to a refrigerator and plenty of counter space.”

Other factors to consider are the site of service, your payer mix, and if you need to complete prior authorizations for patch testing.

Dr. Martin, associate professor of dermatology and child health at the University of Missouri–Columbia, said that the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) crosses her mind when she sees a patient with new dermatitis, especially in an older child; if the dermatitis is patterned or regional; if there’s exacerbation of an underlying, previously stable skin disease; or if it’s a pattern known to be associated with systemic contact dermatitis. “In fact, 13%-25% of healthy, asymptomatic kids have allergen sensitization,” she said. “If you take that a step further and look at kids who are suspected of having allergic contact dermatitis, 25%-96% have allergen sensitization. Still, that doesn’t mean that those tests are relevant to the dermatitis that’s going on. If you take kids who are referred to tertiary centers for patch testing, about half will have relevant patch test results.”

Pediatric ACD differs from adult ACD in three ways, Dr. Martin said. First, children have a different clinical morphology and distribution on presentation, compared with adults. “In adults, the most common clinical presentation is hand dermatitis, while kids more often present with a scattered generalized morphology of dermatitis,” she said. “This occurs in about one-third of children with ACD. Their patterns of allergen exposure are also different. For the most part, adults are in control of their own environments and what is placed on their skin, whereas kids are not. When thinking about what you might need to patch test a child to if you’re considering ACD, it’s important to think about not only what the parent or caregiver puts directly on the child’s skin but also any connubial or consort allergen exposure – the most common ones coming from the caregivers themselves, such as fragrance or hair dyes that are transferred to a young child.”

The third factor that differs between pediatric and adult ACD is the allergen source. Dr. Martin noted that children and adults use different personal care products, wear different types of clothing, and spend different amounts of time in play versus work. “Children have many more hobbies in general that are unfortunately lost as many of us age,” she said. That means “thinking through the child’s entire day and how the seasons differ for them, such as what sports they’re in and what protective equipment may be involved with where their dermatitis is, or what musical instruments they play.”

Applying the T.R.U.E. patch test panel or a customized patch test panel to young children poses certain challenges, considering their limited body surface area and propensity to squirm. Dr. Martin often employs distraction techniques when placing patches on young patients, including the use of bubbles, music, movies, and games. “The goal is always to get as much of the patches on the back or the flanks as possible,” she said. “If you need additional space you can use the upper outer arms, the abdomen, or the anterior lateral thighs. Another thing to consider is how to set up your week for pediatric patch testing. There’s a standardized process for adults where we place the patches on day 0, read them on day 2, with removal of the patches at that time, and then perform a delayed read between day 4-7.”

The process is similar for postpubescent children, despite the lack of clear guidelines in the medical literature. “There is much controversy and different practices between different pediatric patch test centers,” Dr. Martin said. “There is more consensus between the older kids and the prepubescent group ages 6-12. Most clinicians will still do a similar placement on day 0 with removal and initial read on day 2, with a delayed read on day 4-7. However, some groups will remove patches at 24 hours, especially in those with atopic dermatitis (AD) or a generalized dermatitis, to reduce irritant reactions. Others will also use half-strength concentrations of allergens.”

The most controversy lies with children younger than 6 years, she said. For those aged 3-6 years, who do not have AD, most practices use a standardized pediatric tray with a 24- to 48-hour contact time. However, patch testing can be “very challenging” for children who are under 3 years of age, and children with AD who are under 6 years, “so there needs to be a very high degree of suspicion for ACD and very careful selection of the allergens and contact time that is used in those particular cases,” she noted.

The most common allergens in children are nickel, fragrance mix I, cobalt, balsam of Peru, neomycin, and bacitracin, which largely match the common allergens seen in adults. However, allergens more common in children, compared with adults, include gold, propylene glycol, 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, and cocamidopropyl betaine. “If the child presents with a regional dermatitis or a patterned dermatitis, sometimes you can hone in on your suspected allergens and only test for a few,” Dr. Martin said. “In a child with eyelid dermatitis, you’re going to worry more about cocamidopropyl betaine in their shampoos and cleansers. Also, a metal allergen could be transferred from their hands from toys or coins, specifically nickel and cobalt. They also may have different sports gear such as goggles that may be affecting their eyelid dermatitis, which you would not necessarily see in an adult.”

Periorificial contact dermatitis can also differ in presentation between children and adults. “In kids, think about musical instruments, flavored lip balms, gum, and pacifiers,” she said. “For ACD on the buttocks and posterior thighs, think about toilet seat allergens, especially those in the potty training ages, and the nickel bolts on school chairs.”

In 2018, Dr. Martin and her colleagues on the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup published a pediatric baseline patch test series as a way to expand on the T.R.U.E. test (Dermatitis. 2018;29[4]:206-12). “It’s nice to have this panel available as a baseline screening tool when you’re unsure of possible triggers of the dermatitis but you still have high suspicion of allergic dermatitis,” Dr. Martin said. “This also is helpful for patients who present with generalized dermatitis. It’s still not perfect. We are collecting prospective data to fine-tune this baseline series.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

“Time needs to be allocated for a patch test consultation, placement, removal, and reading,” she said at the virtual annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology. “You will need more time in the day that you’re reading the patch test for patient education. However, your staff will need more time on the front end of the patch test process for application. Also, if they are customizing patch tests, they’ll need time to make the patch tests along with access to a refrigerator and plenty of counter space.”

Other factors to consider are the site of service, your payer mix, and if you need to complete prior authorizations for patch testing.

Dr. Martin, associate professor of dermatology and child health at the University of Missouri–Columbia, said that the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) crosses her mind when she sees a patient with new dermatitis, especially in an older child; if the dermatitis is patterned or regional; if there’s exacerbation of an underlying, previously stable skin disease; or if it’s a pattern known to be associated with systemic contact dermatitis. “In fact, 13%-25% of healthy, asymptomatic kids have allergen sensitization,” she said. “If you take that a step further and look at kids who are suspected of having allergic contact dermatitis, 25%-96% have allergen sensitization. Still, that doesn’t mean that those tests are relevant to the dermatitis that’s going on. If you take kids who are referred to tertiary centers for patch testing, about half will have relevant patch test results.”

Pediatric ACD differs from adult ACD in three ways, Dr. Martin said. First, children have a different clinical morphology and distribution on presentation, compared with adults. “In adults, the most common clinical presentation is hand dermatitis, while kids more often present with a scattered generalized morphology of dermatitis,” she said. “This occurs in about one-third of children with ACD. Their patterns of allergen exposure are also different. For the most part, adults are in control of their own environments and what is placed on their skin, whereas kids are not. When thinking about what you might need to patch test a child to if you’re considering ACD, it’s important to think about not only what the parent or caregiver puts directly on the child’s skin but also any connubial or consort allergen exposure – the most common ones coming from the caregivers themselves, such as fragrance or hair dyes that are transferred to a young child.”

The third factor that differs between pediatric and adult ACD is the allergen source. Dr. Martin noted that children and adults use different personal care products, wear different types of clothing, and spend different amounts of time in play versus work. “Children have many more hobbies in general that are unfortunately lost as many of us age,” she said. That means “thinking through the child’s entire day and how the seasons differ for them, such as what sports they’re in and what protective equipment may be involved with where their dermatitis is, or what musical instruments they play.”

Applying the T.R.U.E. patch test panel or a customized patch test panel to young children poses certain challenges, considering their limited body surface area and propensity to squirm. Dr. Martin often employs distraction techniques when placing patches on young patients, including the use of bubbles, music, movies, and games. “The goal is always to get as much of the patches on the back or the flanks as possible,” she said. “If you need additional space you can use the upper outer arms, the abdomen, or the anterior lateral thighs. Another thing to consider is how to set up your week for pediatric patch testing. There’s a standardized process for adults where we place the patches on day 0, read them on day 2, with removal of the patches at that time, and then perform a delayed read between day 4-7.”

The process is similar for postpubescent children, despite the lack of clear guidelines in the medical literature. “There is much controversy and different practices between different pediatric patch test centers,” Dr. Martin said. “There is more consensus between the older kids and the prepubescent group ages 6-12. Most clinicians will still do a similar placement on day 0 with removal and initial read on day 2, with a delayed read on day 4-7. However, some groups will remove patches at 24 hours, especially in those with atopic dermatitis (AD) or a generalized dermatitis, to reduce irritant reactions. Others will also use half-strength concentrations of allergens.”

The most controversy lies with children younger than 6 years, she said. For those aged 3-6 years, who do not have AD, most practices use a standardized pediatric tray with a 24- to 48-hour contact time. However, patch testing can be “very challenging” for children who are under 3 years of age, and children with AD who are under 6 years, “so there needs to be a very high degree of suspicion for ACD and very careful selection of the allergens and contact time that is used in those particular cases,” she noted.

The most common allergens in children are nickel, fragrance mix I, cobalt, balsam of Peru, neomycin, and bacitracin, which largely match the common allergens seen in adults. However, allergens more common in children, compared with adults, include gold, propylene glycol, 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, and cocamidopropyl betaine. “If the child presents with a regional dermatitis or a patterned dermatitis, sometimes you can hone in on your suspected allergens and only test for a few,” Dr. Martin said. “In a child with eyelid dermatitis, you’re going to worry more about cocamidopropyl betaine in their shampoos and cleansers. Also, a metal allergen could be transferred from their hands from toys or coins, specifically nickel and cobalt. They also may have different sports gear such as goggles that may be affecting their eyelid dermatitis, which you would not necessarily see in an adult.”

Periorificial contact dermatitis can also differ in presentation between children and adults. “In kids, think about musical instruments, flavored lip balms, gum, and pacifiers,” she said. “For ACD on the buttocks and posterior thighs, think about toilet seat allergens, especially those in the potty training ages, and the nickel bolts on school chairs.”

In 2018, Dr. Martin and her colleagues on the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Workgroup published a pediatric baseline patch test series as a way to expand on the T.R.U.E. test (Dermatitis. 2018;29[4]:206-12). “It’s nice to have this panel available as a baseline screening tool when you’re unsure of possible triggers of the dermatitis but you still have high suspicion of allergic dermatitis,” Dr. Martin said. “This also is helpful for patients who present with generalized dermatitis. It’s still not perfect. We are collecting prospective data to fine-tune this baseline series.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM SPD 2020

Atretic Cephalocele With Hypertrichosis

To the Editor:

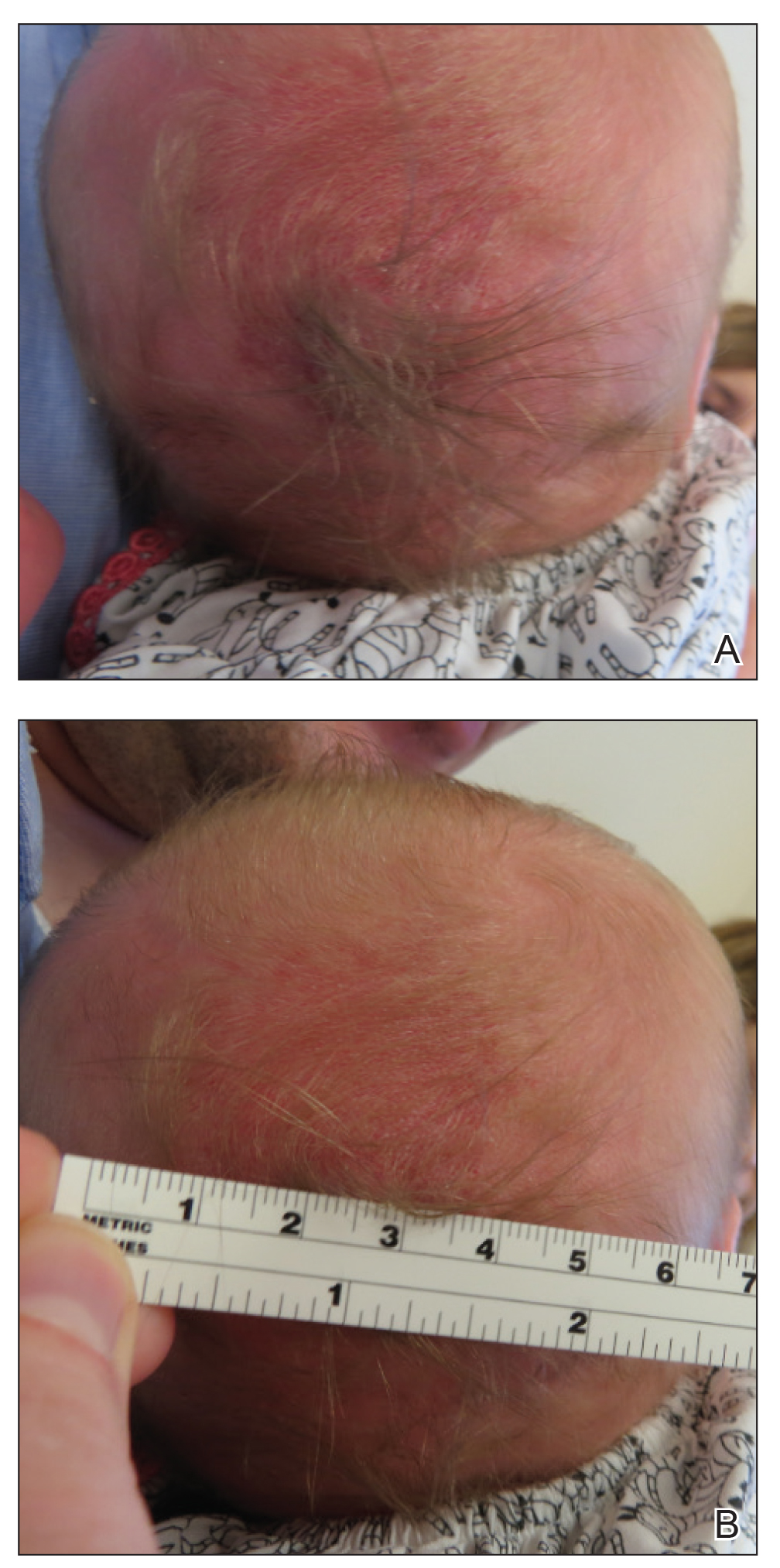

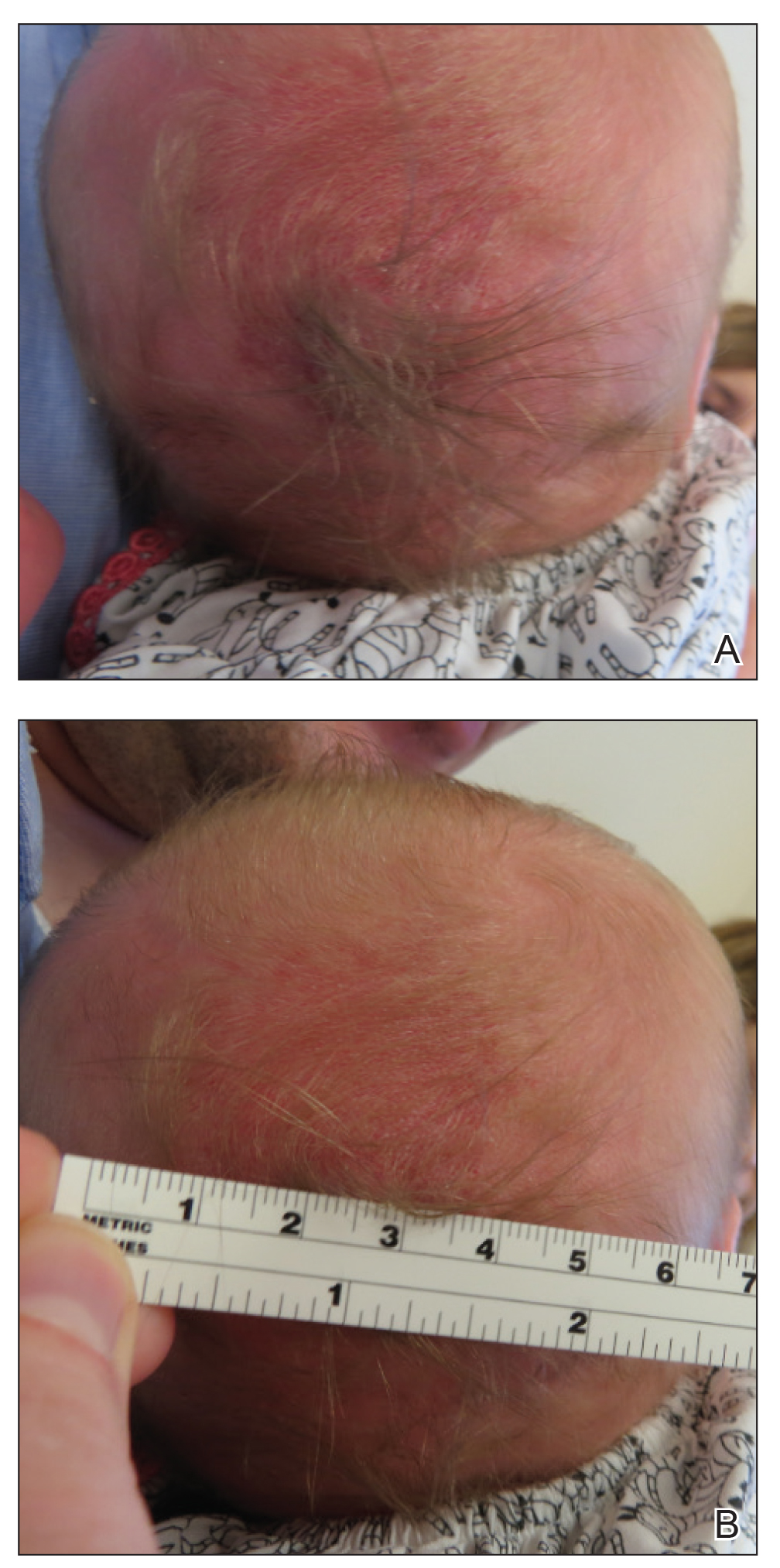

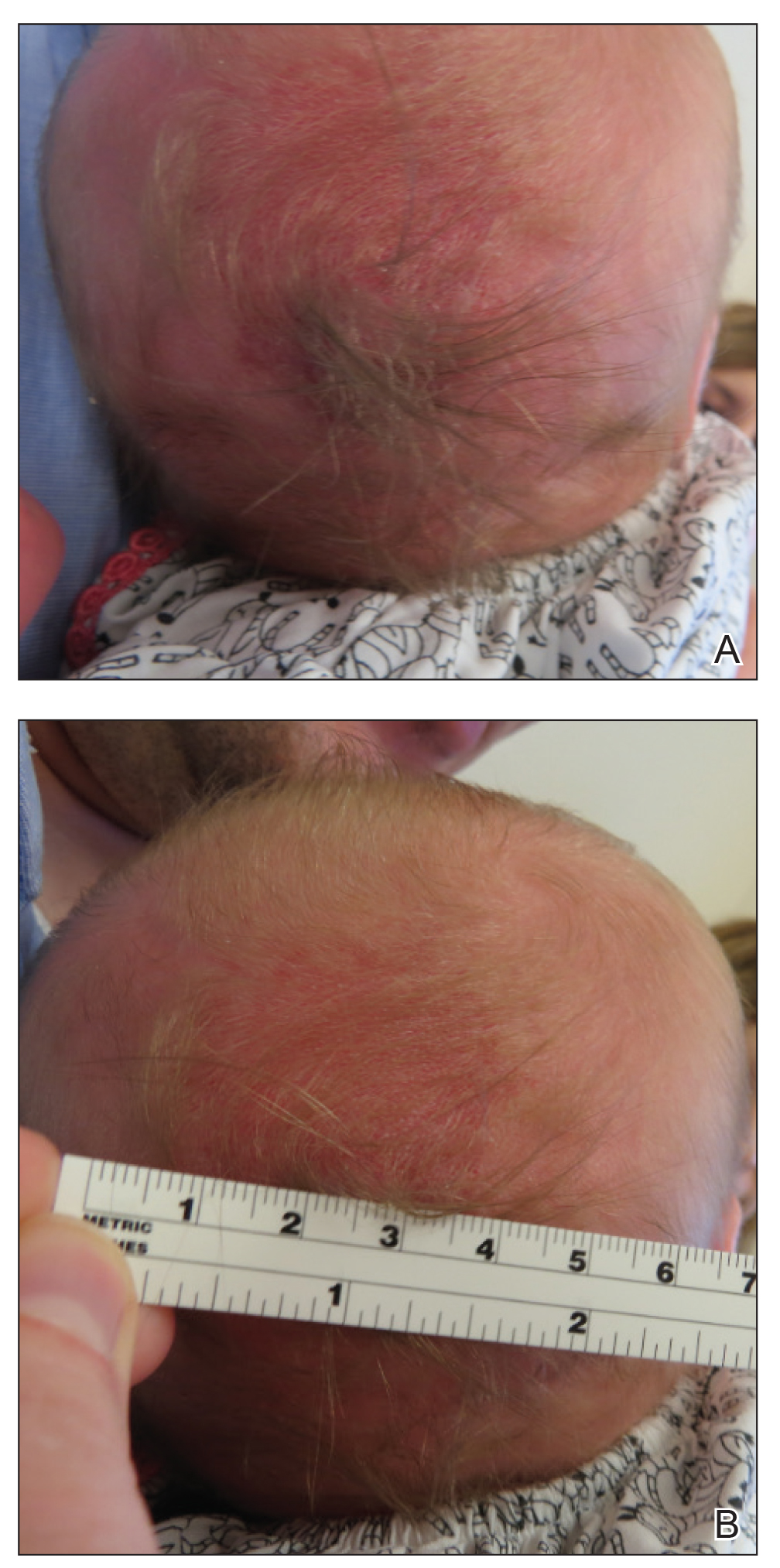

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

To the Editor:

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

To the Editor:

A 2-week-old female infant presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of a 4.0×4.5-cm pink-red patch with a 1-cm central nodule and an overlying tuft of hair on the midline occipital region (Figure). The patient was born at 39 weeks’ gestation to nonconsanguineous parents via a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery and had an unremarkable prenatal course with no complications since birth. The red patch and tuft of hair were noted at birth, and the parents reported that the redness varied somewhat in size throughout the day and from day to day. An initial neurologic workup revealed no gross neurologic abnormalities. A head ultrasound revealed a soft-tissue hypervascular nodule that appeared separate from bony structures but showed evidence of a necklike extension from the nodule to the underlying soft tissues. The ultrasound could not definitively rule out intracranial extension; gross brain structures appeared normal. The initial differential diagnosis consisted of a congenital hemangioma (either a rapidly involuting or noninvoluting subtype), meningioma, or cephalocele.

Consultation with the pediatric neurosurgery service was sought, and magnetic resonance imaging of the head was performed, which demonstrated a cystic lesion within the subcutaneous soft tissue in the midline posterior scalp approximately 2 cm above the torcula. There also was a thin stalk extending from the cyst and going through an osseous defect within the occipital bone and attaching to the falx cerebri. There was no evidence of any venous communication with the cerebral sinus tracts or intraparenchymal extension. No intracranial abnormalities were noted. Given the radiographic evidence, a presumptive diagnosis of an atretic cephalocele was made with the plan for surgical repair.

The patient was re-evaluated at 3 and 4 months of age; there were no changes in the size or appearance of the lesion, and she continued to meet all developmental milestones. At 9 months of age the patient underwent uncomplicated neurosurgery to repair the cephalocele. Histopathologic examination of the resected lesion was consistent with an atretic cephalocele and showed positive staining for epithelial membrane antigen, which further confirmed a meningothelial origin; no glial elements were identified. The postoperative course was uncomplicated, and the patient was healing well at a follow-up examination 2 weeks after the procedure.

This case highlights the importance of an extensive workup when a patient presents with a midline lesion and hypertrichosis. The patient’s red patch, excluding the hair tuft, was reminiscent of a vascular malformation or hemangioma precursor lesion given the hypervascularity, the history of the lesion being present since birth, the lack of neurologic symptomatology, and the history of meeting all developmental milestones. The differential diagnosis for this patient was extensive, as many neurologic conditions present with cutaneous findings. Having central nervous system (CNS) and cutaneous comorbidities coincide underscores their common neuroectodermal origin during embryogenesis.1,2

Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis, with the prevalence of cephaloceles estimated to be 0.8 to 3.0 per 10,000 births.3 It typically occurs in either the parietal or occipital scalp as a skin nodule with a hair tuft or alopecic lesion with or without a hair collar. A cephalocele is defined as a skin-covered protrusion of intracranial contents through a bony defect. Central nervous system tissue, meninges, or cerebrospinal fluid can protrude outside the skull with this condition. An atretic cephalocele refers to a cephalocele that arrested in development and represents approximately 40% to 50% of all cephaloceles.4 Various hypotheses have explained the development of atretic cephaloceles: it represents a neural crest remnant, regression of a meningocele in utero, injury of multipotential mesenchymal cells, and either failure of the neural tube to close or reopening of the neural tube after closure.4-6 There is evidence of developmental defects in skin appendages including sweat and sebaceous glands, arrector pili muscles, and hair follicles in and around the skin overlying the cephalocele, suggesting that there is a developmental abnormality of not only the CNS but also the cutaneous tissue.5 Typical radiographic findings include a cystic lesion with underlying defect in the skull. A vertical positioning of the straight sinus also has been demonstrated to be a consistent finding that can aid in diagnosis.4

Imaging is of utmost importance when a patient presents with a tuft of hair on the scalp to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities such as gray matter heterotopia, hypogenesis of the corpus callosum, hydrocephalus, and Dandy-Walker and Walker-Warburg syndromes, which have all been associated with atretic cephaloceles.4,7 The impact of location of the intracranial abnormality on prognosis has been contested, with some reporting a better prognosis with occipital cephalocele vs parietal cephalocele while others have found the opposite to be true.6,7

Cutaneous abnormalities presenting with hypertrichosis (ie, hair tuft, hair collar) and/or capillary malformations increase the likelihood of a cranial dysraphism, especially when these findings present together and occur in and around the midline. Clinical examination cannot rule out an underlying connection to the CNS; these findings require appropriate radiographic imaging assessment prior to any procedural intervention.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

- Drolet BA, Clowry L, McTigue K, et al. The hair collar sign: marker for cranial dysraphism. Pediatrics. 1995;96(2, pt 1):309-313.

- Sewell MJ, Chiu YE, Drolet BA. Neural tube dysraphism: review of cutaneous markers and imaging. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:161-170.

- Carvalho DR, Giuliani LR, Simão GN, et al. Autosomal dominant atretic cephalocele with phenotype variability: report of a Brazilian family with six affected in four generation. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140:1458-1462.

- Bick DS, Brockland JJ, Scott AR. A scalp lesion with intracranial extension. atretic cephalocele. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141:289-290.

- Fukuyama M, Tanese K, Yasuda F, et al. Two cases of atretic cephalocele, and histological evaluation of skin appendages in the surrounding skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:48-52.

- Martinez-Lage JF, Sola J, Casas C, et al. Atretic cephalocele: the tip of the iceberg. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:230-235.

- Yakota A, Kajiwara H, Kohchi M, et al. Parietal cephalocele: clinical importance of its atretic form and associated malformation. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:545-551.

Practice Points

- Atretic cephalocele is a rare diagnosis occurring on the scalp as a nodule with an overlying hair tuft or alopecia with or without a hair collar.

- Imaging is of utmost importance when presented with a tuft of hair on the midline to rule out intracranial extension and associated abnormalities.

Stress, COVID-19 contribute to mental health concerns in college students

Socioeconomic, technological, cultural, and historical conditions are contributing to a mental health crisis among college students in the United States, according to Anthony L. Rostain, MD, MA, in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

A recent National College Health Assessment published in fall of 2018 by the American College Health Association found that one in four college students had some kind of diagnosable mental illness, and 44% had symptoms of depression within the past year.

The assessment also found that college students felt overwhelmed (86%), felt sad (68%), felt very lonely (63%), had overwhelming anxiety (62%), experienced feelings of hopelessness (53%), or were depressed to the point where functioning was difficult (41%), all of which was higher than in previous years. Students also were more likely than in previous years to engage in interpersonal violence (17%), seriously consider suicide (11%), intentionally hurt themselves (7.4%), and attempt suicide (1.9%). According to the organization Active Minds, suicide is a leading cause of death in college students.

This shift in mental health for individuals in Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, can be attributed to historical events since the turn of the century, Dr. Rostain said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, school shootings, globalization leading to economic uncertainty, the 24-hour news cycle and continuous media exposure, and the influence of the Internet have all influenced Gen Z’s identity.

“Growing up immersed in the Internet certainly has its advantages, but also maybe created some vulnerabilities in our young people,” he said.

Concerns about climate change, the burden of higher education and student debt, and the COVID-19 pandemic also have contributed to anxiety in this group. In a spring survey of students published by Active Minds about COVID-19 and its impact on mental health, 91% of students reported having stress or anxiety, 81% were disappointed or sad, 80% said they felt lonely or isolated, 56% had relocated as a result of the pandemic, and 48% reported financial setbacks tied to COVID-19.

“Anxiety seems to have become a feature of modern life,” said Dr. Rostain, who is director of education at the department of psychiatry and professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“Our culture, which often has a prominent emotional tone of fear, tends to promote cognitive distortions in which everyone is perceiving danger at every turn.” in this group, he noted. While people should be washing their hands and staying safe through social distancing during the pandemic, “we don’t want people to stop functioning, planning the future, and really in college students’ case, studying and getting ready for their careers,” he said. Parents can hinder those goals through intensively parenting or “overparenting” their children, which can result in destructive perfectionism, anxiety and depression, abject fear of failure and risk avoidance, and a focus on the external aspects of life rather than internal feelings.

Heavier alcohol use and amphetamine use also is on the rise in college students, Dr. Rostain said. Increased stimulant use in young adults is attributed to greater access to prescription drugs prior to college, greater prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peer pressure, and influence from marketing and media messaging, he said. Another important change is the rise of smartphones and the Internet, which might drive the need to be constantly connected and compete for attention.

“This is the first generation who had constant access to the Internet. Smartphones in particular are everywhere, and we think this is another important factor in considering what might be happening to young people,” Dr. Rostain said.

Developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, developing coping mechanisms, being able to regulate emotions, finding optimism toward the future, having access to mental health services, and having cultural or religious beliefs with a negative view of suicide are all protective factors that promote resiliency in young people, Dr. Rostain said. Other protective factors include the development of socio-emotional readiness skills, such as conscientiousness, self-management, interpersonal skills, self-control, task persistence, risk management, self-acceptance, and having an open mindset or seeking help when needed. However, he noted, family is one area that can be both a help or a risk to mental health.

“Family attachments and supportive relationships in the family are really critical in predicting good outcomes. By the same token, families that are conflicted, where there’s a lot of stress or there’s a lot of turmoil and/or where resources are not available, that may be a risk factor to coping in young adulthood,” he said.

Individual resilience can be developed through learning from mistakes and overcoming mindset barriers, such as feelings of not belonging, concerns about disappointing one’s parents, worries about not making it, or fears of being different.

On campus, best practices and emerging trends include wellness and resiliency programs, reducing stigma, engagement from students, training of faculty and staff, crisis management plans, telehealth counseling, substance abuse programs, postvention support after suicide, collaboration with mental health providers, and support for diverse populations.

“The best schools are the ones that promote communication and that invite families to be involved early on because parents and families can be and need to be educated about what to do to prevent adverse outcomes of young people who are really at risk,” Dr. Rostain said. “It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes the same village to bring someone from adolescence to young adulthood.”

Family-based intervention has also shown promise, he said, but clinicians should watch for signs that a family is not willing to undergo therapy, is scapegoating a college student, or there are signs of boundary violations, violence, or sexual abuse in the family – or attempts to undermine treatment.

Specific to COVID-19, campus mental health services should focus on routine, self-care, physical activity, and connections with other people while also space for grieving lost experiences, facing uncertainty, developing resilience, and finding meaning. In the family, challenges around COVID-19 can include issues of physical distancing and quarantine, anxiety about becoming infected with the virus, economic insecurity, managing conflicts, setting and enforcing boundaries in addition to providing mutual support, and finding new meaning during the pandemic.

“I think these are the challenges, but we think this whole process of people living together and handling life in a way they’ve never expected to may hold some silver linings,” Dr. Rostain said. “It may be a way of addressing many issues that were never addressed before the young person went off to college.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Rostain reported receiving royalties from Routledge/Taylor Francis Group and St. Martin’s Press, scientific advisory board honoraria from Arbor and Shire/Takeda, consulting fees from the National Football League and Tris Pharmaceuticals, and has presented CME sessions for American Psychiatric Publishing, Global Medical Education, Shire/Takeda, and the U.S. Psychiatric Congress.

Socioeconomic, technological, cultural, and historical conditions are contributing to a mental health crisis among college students in the United States, according to Anthony L. Rostain, MD, MA, in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

A recent National College Health Assessment published in fall of 2018 by the American College Health Association found that one in four college students had some kind of diagnosable mental illness, and 44% had symptoms of depression within the past year.

The assessment also found that college students felt overwhelmed (86%), felt sad (68%), felt very lonely (63%), had overwhelming anxiety (62%), experienced feelings of hopelessness (53%), or were depressed to the point where functioning was difficult (41%), all of which was higher than in previous years. Students also were more likely than in previous years to engage in interpersonal violence (17%), seriously consider suicide (11%), intentionally hurt themselves (7.4%), and attempt suicide (1.9%). According to the organization Active Minds, suicide is a leading cause of death in college students.

This shift in mental health for individuals in Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, can be attributed to historical events since the turn of the century, Dr. Rostain said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, school shootings, globalization leading to economic uncertainty, the 24-hour news cycle and continuous media exposure, and the influence of the Internet have all influenced Gen Z’s identity.

“Growing up immersed in the Internet certainly has its advantages, but also maybe created some vulnerabilities in our young people,” he said.

Concerns about climate change, the burden of higher education and student debt, and the COVID-19 pandemic also have contributed to anxiety in this group. In a spring survey of students published by Active Minds about COVID-19 and its impact on mental health, 91% of students reported having stress or anxiety, 81% were disappointed or sad, 80% said they felt lonely or isolated, 56% had relocated as a result of the pandemic, and 48% reported financial setbacks tied to COVID-19.

“Anxiety seems to have become a feature of modern life,” said Dr. Rostain, who is director of education at the department of psychiatry and professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“Our culture, which often has a prominent emotional tone of fear, tends to promote cognitive distortions in which everyone is perceiving danger at every turn.” in this group, he noted. While people should be washing their hands and staying safe through social distancing during the pandemic, “we don’t want people to stop functioning, planning the future, and really in college students’ case, studying and getting ready for their careers,” he said. Parents can hinder those goals through intensively parenting or “overparenting” their children, which can result in destructive perfectionism, anxiety and depression, abject fear of failure and risk avoidance, and a focus on the external aspects of life rather than internal feelings.

Heavier alcohol use and amphetamine use also is on the rise in college students, Dr. Rostain said. Increased stimulant use in young adults is attributed to greater access to prescription drugs prior to college, greater prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peer pressure, and influence from marketing and media messaging, he said. Another important change is the rise of smartphones and the Internet, which might drive the need to be constantly connected and compete for attention.

“This is the first generation who had constant access to the Internet. Smartphones in particular are everywhere, and we think this is another important factor in considering what might be happening to young people,” Dr. Rostain said.

Developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, developing coping mechanisms, being able to regulate emotions, finding optimism toward the future, having access to mental health services, and having cultural or religious beliefs with a negative view of suicide are all protective factors that promote resiliency in young people, Dr. Rostain said. Other protective factors include the development of socio-emotional readiness skills, such as conscientiousness, self-management, interpersonal skills, self-control, task persistence, risk management, self-acceptance, and having an open mindset or seeking help when needed. However, he noted, family is one area that can be both a help or a risk to mental health.

“Family attachments and supportive relationships in the family are really critical in predicting good outcomes. By the same token, families that are conflicted, where there’s a lot of stress or there’s a lot of turmoil and/or where resources are not available, that may be a risk factor to coping in young adulthood,” he said.

Individual resilience can be developed through learning from mistakes and overcoming mindset barriers, such as feelings of not belonging, concerns about disappointing one’s parents, worries about not making it, or fears of being different.

On campus, best practices and emerging trends include wellness and resiliency programs, reducing stigma, engagement from students, training of faculty and staff, crisis management plans, telehealth counseling, substance abuse programs, postvention support after suicide, collaboration with mental health providers, and support for diverse populations.

“The best schools are the ones that promote communication and that invite families to be involved early on because parents and families can be and need to be educated about what to do to prevent adverse outcomes of young people who are really at risk,” Dr. Rostain said. “It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes the same village to bring someone from adolescence to young adulthood.”

Family-based intervention has also shown promise, he said, but clinicians should watch for signs that a family is not willing to undergo therapy, is scapegoating a college student, or there are signs of boundary violations, violence, or sexual abuse in the family – or attempts to undermine treatment.

Specific to COVID-19, campus mental health services should focus on routine, self-care, physical activity, and connections with other people while also space for grieving lost experiences, facing uncertainty, developing resilience, and finding meaning. In the family, challenges around COVID-19 can include issues of physical distancing and quarantine, anxiety about becoming infected with the virus, economic insecurity, managing conflicts, setting and enforcing boundaries in addition to providing mutual support, and finding new meaning during the pandemic.

“I think these are the challenges, but we think this whole process of people living together and handling life in a way they’ve never expected to may hold some silver linings,” Dr. Rostain said. “It may be a way of addressing many issues that were never addressed before the young person went off to college.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Rostain reported receiving royalties from Routledge/Taylor Francis Group and St. Martin’s Press, scientific advisory board honoraria from Arbor and Shire/Takeda, consulting fees from the National Football League and Tris Pharmaceuticals, and has presented CME sessions for American Psychiatric Publishing, Global Medical Education, Shire/Takeda, and the U.S. Psychiatric Congress.

Socioeconomic, technological, cultural, and historical conditions are contributing to a mental health crisis among college students in the United States, according to Anthony L. Rostain, MD, MA, in a virtual meeting presented by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists.

A recent National College Health Assessment published in fall of 2018 by the American College Health Association found that one in four college students had some kind of diagnosable mental illness, and 44% had symptoms of depression within the past year.

The assessment also found that college students felt overwhelmed (86%), felt sad (68%), felt very lonely (63%), had overwhelming anxiety (62%), experienced feelings of hopelessness (53%), or were depressed to the point where functioning was difficult (41%), all of which was higher than in previous years. Students also were more likely than in previous years to engage in interpersonal violence (17%), seriously consider suicide (11%), intentionally hurt themselves (7.4%), and attempt suicide (1.9%). According to the organization Active Minds, suicide is a leading cause of death in college students.

This shift in mental health for individuals in Generation Z, those born between the mid-1990s and early 2010s, can be attributed to historical events since the turn of the century, Dr. Rostain said at the meeting, presented by Global Academy for Medical Education. The Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the financial crisis of 2007-2008, school shootings, globalization leading to economic uncertainty, the 24-hour news cycle and continuous media exposure, and the influence of the Internet have all influenced Gen Z’s identity.

“Growing up immersed in the Internet certainly has its advantages, but also maybe created some vulnerabilities in our young people,” he said.

Concerns about climate change, the burden of higher education and student debt, and the COVID-19 pandemic also have contributed to anxiety in this group. In a spring survey of students published by Active Minds about COVID-19 and its impact on mental health, 91% of students reported having stress or anxiety, 81% were disappointed or sad, 80% said they felt lonely or isolated, 56% had relocated as a result of the pandemic, and 48% reported financial setbacks tied to COVID-19.

“Anxiety seems to have become a feature of modern life,” said Dr. Rostain, who is director of education at the department of psychiatry and professor of psychiatry at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“Our culture, which often has a prominent emotional tone of fear, tends to promote cognitive distortions in which everyone is perceiving danger at every turn.” in this group, he noted. While people should be washing their hands and staying safe through social distancing during the pandemic, “we don’t want people to stop functioning, planning the future, and really in college students’ case, studying and getting ready for their careers,” he said. Parents can hinder those goals through intensively parenting or “overparenting” their children, which can result in destructive perfectionism, anxiety and depression, abject fear of failure and risk avoidance, and a focus on the external aspects of life rather than internal feelings.

Heavier alcohol use and amphetamine use also is on the rise in college students, Dr. Rostain said. Increased stimulant use in young adults is attributed to greater access to prescription drugs prior to college, greater prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peer pressure, and influence from marketing and media messaging, he said. Another important change is the rise of smartphones and the Internet, which might drive the need to be constantly connected and compete for attention.

“This is the first generation who had constant access to the Internet. Smartphones in particular are everywhere, and we think this is another important factor in considering what might be happening to young people,” Dr. Rostain said.

Developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, developing coping mechanisms, being able to regulate emotions, finding optimism toward the future, having access to mental health services, and having cultural or religious beliefs with a negative view of suicide are all protective factors that promote resiliency in young people, Dr. Rostain said. Other protective factors include the development of socio-emotional readiness skills, such as conscientiousness, self-management, interpersonal skills, self-control, task persistence, risk management, self-acceptance, and having an open mindset or seeking help when needed. However, he noted, family is one area that can be both a help or a risk to mental health.

“Family attachments and supportive relationships in the family are really critical in predicting good outcomes. By the same token, families that are conflicted, where there’s a lot of stress or there’s a lot of turmoil and/or where resources are not available, that may be a risk factor to coping in young adulthood,” he said.

Individual resilience can be developed through learning from mistakes and overcoming mindset barriers, such as feelings of not belonging, concerns about disappointing one’s parents, worries about not making it, or fears of being different.

On campus, best practices and emerging trends include wellness and resiliency programs, reducing stigma, engagement from students, training of faculty and staff, crisis management plans, telehealth counseling, substance abuse programs, postvention support after suicide, collaboration with mental health providers, and support for diverse populations.

“The best schools are the ones that promote communication and that invite families to be involved early on because parents and families can be and need to be educated about what to do to prevent adverse outcomes of young people who are really at risk,” Dr. Rostain said. “It takes a village to raise a child, and it takes the same village to bring someone from adolescence to young adulthood.”

Family-based intervention has also shown promise, he said, but clinicians should watch for signs that a family is not willing to undergo therapy, is scapegoating a college student, or there are signs of boundary violations, violence, or sexual abuse in the family – or attempts to undermine treatment.

Specific to COVID-19, campus mental health services should focus on routine, self-care, physical activity, and connections with other people while also space for grieving lost experiences, facing uncertainty, developing resilience, and finding meaning. In the family, challenges around COVID-19 can include issues of physical distancing and quarantine, anxiety about becoming infected with the virus, economic insecurity, managing conflicts, setting and enforcing boundaries in addition to providing mutual support, and finding new meaning during the pandemic.

“I think these are the challenges, but we think this whole process of people living together and handling life in a way they’ve never expected to may hold some silver linings,” Dr. Rostain said. “It may be a way of addressing many issues that were never addressed before the young person went off to college.”

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same parent company. Dr. Rostain reported receiving royalties from Routledge/Taylor Francis Group and St. Martin’s Press, scientific advisory board honoraria from Arbor and Shire/Takeda, consulting fees from the National Football League and Tris Pharmaceuticals, and has presented CME sessions for American Psychiatric Publishing, Global Medical Education, Shire/Takeda, and the U.S. Psychiatric Congress.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CP/AACP 2020 PSYCHIATRY UPDATE

Acute EVALI remains a diagnosis of exclusion

according to a synthesis of current information presented at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Respiratory symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath are common but so are constitutive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, said Yamini Kuchipudi, MD, a staff physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, during the session at the virtual meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

If EVALI is not considered across this broad array of symptoms, of which respiratory complaints might not be the most prominent at the time of presentation, the diagnosis might be delayed, Dr. Kuchipudi warned during the virtual meeting.

Teenagers and young adults are the most common users of e-cigarettes and vaping devices. In these patients or in any individual suspected of having EVALI, Dr. Kuchipudi recommended posing questions about vaping relatively early in the work-up “in a confidential and nonjudgmental way.”

Eliciting a truthful history will be particularly important, because the risk of EVALI appears to be largely related to vaping with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products rather than with nicotine alone. Although the exact cause of EVALI is not yet completely clear, this condition is now strongly associated with additives to the THC, according to Issa Hanna, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

“E-liquid contains products like hydrocarbons, vitamin E acetate, and heavy metals that appear to damage the alveolar epithelium by direct cellular inflammation,” Dr. Hanna explained.

These products are not only found in THC processed for vaping but also for dabbing, a related but different form of inhalation that involves vaporization of highly concentrated THC waxes or resins. Dr. Hanna suggested that the decline in reported cases of EVALI, which has followed the peak incidence in September 2019, is likely to be related to a decline in THC additives as well as greater caution among users.

E-cigarettes were introduced in 2007, according to Dr. Hanna, but EVALI was not widely recognized until cases began accruing early in 2019. By June 2019, the growing number of case reports had attracted the attention of the media as well as public health officials, intensifying the effort to isolate the risks and causes.

Consistent with greater use of e-cigarettes and vaping among younger individuals, nearly 80% of the 2,807 patients hospitalized for EVALI in the United States by February of this year occurred in individuals aged less than 35 years, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The median age was less than 25 years. Of these hospitalizations, 68 deaths (2.5%) in 29 states and Washington, D.C., were attributed to EVALI.

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of a definitive diagnostic test, EVALI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, according to Abigail Musial, MD, who is completing a fellowship in hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s. She presented a case in which a patient suspected of EVALI went home after symptoms abated on steroids.

“Less than 24 hours later, she returned to the ED with tachypnea and hypoxemia,” Dr. Musial recounted. Although a chest x-ray at the initial evaluation showed lung opacities, a repeat chest x-ray when she returned to the ED showed bilateral worsening of these opacities and persistent elevation of inflammatory markers.

“She was started on steroids and also on antibiotics,” Dr. Musial said. “She was weaned quickly from oxygen once the steroids were started and was discharged on hospital day 3.”

For patients suspected of EVALI, COVID-19 testing should be part of the work-up, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. She also recommended an x-ray or CT scan of the lung as well as an evaluation of inflammatory markers.

Dr. Kuchipudi said that more invasive studies than lung function tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy, might be considered when severe symptoms make aggressive diagnostic studies attractive.

Steroids and antibiotics typically lead to control of acute symptoms, but patients should be clinically stable for 24-48 hours prior to hospital discharge, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. Follow-up after discharge should include lung function tests and imaging 2-4 weeks later to confirm resolution of abnormalities.

Dr. Kuchipudi stressed the opportunity that an episode of EVALI provides to induce patients to give up nicotine and vaping entirely. Such strategies, such as a nicotine patch, deserve consideration, but she also cautioned that e-cigarettes for smoking cessation should not be recommended to EVALI patients.

The speakers reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

according to a synthesis of current information presented at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Respiratory symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath are common but so are constitutive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, said Yamini Kuchipudi, MD, a staff physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, during the session at the virtual meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

If EVALI is not considered across this broad array of symptoms, of which respiratory complaints might not be the most prominent at the time of presentation, the diagnosis might be delayed, Dr. Kuchipudi warned during the virtual meeting.

Teenagers and young adults are the most common users of e-cigarettes and vaping devices. In these patients or in any individual suspected of having EVALI, Dr. Kuchipudi recommended posing questions about vaping relatively early in the work-up “in a confidential and nonjudgmental way.”

Eliciting a truthful history will be particularly important, because the risk of EVALI appears to be largely related to vaping with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products rather than with nicotine alone. Although the exact cause of EVALI is not yet completely clear, this condition is now strongly associated with additives to the THC, according to Issa Hanna, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

“E-liquid contains products like hydrocarbons, vitamin E acetate, and heavy metals that appear to damage the alveolar epithelium by direct cellular inflammation,” Dr. Hanna explained.

These products are not only found in THC processed for vaping but also for dabbing, a related but different form of inhalation that involves vaporization of highly concentrated THC waxes or resins. Dr. Hanna suggested that the decline in reported cases of EVALI, which has followed the peak incidence in September 2019, is likely to be related to a decline in THC additives as well as greater caution among users.

E-cigarettes were introduced in 2007, according to Dr. Hanna, but EVALI was not widely recognized until cases began accruing early in 2019. By June 2019, the growing number of case reports had attracted the attention of the media as well as public health officials, intensifying the effort to isolate the risks and causes.

Consistent with greater use of e-cigarettes and vaping among younger individuals, nearly 80% of the 2,807 patients hospitalized for EVALI in the United States by February of this year occurred in individuals aged less than 35 years, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The median age was less than 25 years. Of these hospitalizations, 68 deaths (2.5%) in 29 states and Washington, D.C., were attributed to EVALI.

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of a definitive diagnostic test, EVALI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, according to Abigail Musial, MD, who is completing a fellowship in hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s. She presented a case in which a patient suspected of EVALI went home after symptoms abated on steroids.

“Less than 24 hours later, she returned to the ED with tachypnea and hypoxemia,” Dr. Musial recounted. Although a chest x-ray at the initial evaluation showed lung opacities, a repeat chest x-ray when she returned to the ED showed bilateral worsening of these opacities and persistent elevation of inflammatory markers.

“She was started on steroids and also on antibiotics,” Dr. Musial said. “She was weaned quickly from oxygen once the steroids were started and was discharged on hospital day 3.”

For patients suspected of EVALI, COVID-19 testing should be part of the work-up, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. She also recommended an x-ray or CT scan of the lung as well as an evaluation of inflammatory markers.

Dr. Kuchipudi said that more invasive studies than lung function tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy, might be considered when severe symptoms make aggressive diagnostic studies attractive.

Steroids and antibiotics typically lead to control of acute symptoms, but patients should be clinically stable for 24-48 hours prior to hospital discharge, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. Follow-up after discharge should include lung function tests and imaging 2-4 weeks later to confirm resolution of abnormalities.

Dr. Kuchipudi stressed the opportunity that an episode of EVALI provides to induce patients to give up nicotine and vaping entirely. Such strategies, such as a nicotine patch, deserve consideration, but she also cautioned that e-cigarettes for smoking cessation should not be recommended to EVALI patients.

The speakers reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

according to a synthesis of current information presented at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

Respiratory symptoms, including cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath are common but so are constitutive symptoms, including fever, sore throat, muscle aches, nausea and vomiting, said Yamini Kuchipudi, MD, a staff physician at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, during the session at the virtual meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

If EVALI is not considered across this broad array of symptoms, of which respiratory complaints might not be the most prominent at the time of presentation, the diagnosis might be delayed, Dr. Kuchipudi warned during the virtual meeting.

Teenagers and young adults are the most common users of e-cigarettes and vaping devices. In these patients or in any individual suspected of having EVALI, Dr. Kuchipudi recommended posing questions about vaping relatively early in the work-up “in a confidential and nonjudgmental way.”

Eliciting a truthful history will be particularly important, because the risk of EVALI appears to be largely related to vaping with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)-containing products rather than with nicotine alone. Although the exact cause of EVALI is not yet completely clear, this condition is now strongly associated with additives to the THC, according to Issa Hanna, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Florida, Jacksonville.

“E-liquid contains products like hydrocarbons, vitamin E acetate, and heavy metals that appear to damage the alveolar epithelium by direct cellular inflammation,” Dr. Hanna explained.

These products are not only found in THC processed for vaping but also for dabbing, a related but different form of inhalation that involves vaporization of highly concentrated THC waxes or resins. Dr. Hanna suggested that the decline in reported cases of EVALI, which has followed the peak incidence in September 2019, is likely to be related to a decline in THC additives as well as greater caution among users.

E-cigarettes were introduced in 2007, according to Dr. Hanna, but EVALI was not widely recognized until cases began accruing early in 2019. By June 2019, the growing number of case reports had attracted the attention of the media as well as public health officials, intensifying the effort to isolate the risks and causes.

Consistent with greater use of e-cigarettes and vaping among younger individuals, nearly 80% of the 2,807 patients hospitalized for EVALI in the United States by February of this year occurred in individuals aged less than 35 years, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The median age was less than 25 years. Of these hospitalizations, 68 deaths (2.5%) in 29 states and Washington, D.C., were attributed to EVALI.

Because of the nonspecific symptoms and lack of a definitive diagnostic test, EVALI is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, according to Abigail Musial, MD, who is completing a fellowship in hospital medicine at Cincinnati Children’s. She presented a case in which a patient suspected of EVALI went home after symptoms abated on steroids.

“Less than 24 hours later, she returned to the ED with tachypnea and hypoxemia,” Dr. Musial recounted. Although a chest x-ray at the initial evaluation showed lung opacities, a repeat chest x-ray when she returned to the ED showed bilateral worsening of these opacities and persistent elevation of inflammatory markers.

“She was started on steroids and also on antibiotics,” Dr. Musial said. “She was weaned quickly from oxygen once the steroids were started and was discharged on hospital day 3.”

For patients suspected of EVALI, COVID-19 testing should be part of the work-up, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. She also recommended an x-ray or CT scan of the lung as well as an evaluation of inflammatory markers.

Dr. Kuchipudi said that more invasive studies than lung function tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy, might be considered when severe symptoms make aggressive diagnostic studies attractive.

Steroids and antibiotics typically lead to control of acute symptoms, but patients should be clinically stable for 24-48 hours prior to hospital discharge, according to Dr. Kuchipudi. Follow-up after discharge should include lung function tests and imaging 2-4 weeks later to confirm resolution of abnormalities.