User login

Even a few days of steroids may be risky, new study suggests

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Extended use of corticosteroids for chronic inflammatory conditions puts patients at risk for serious adverse events (AEs), including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, cataracts, and diabetes. Now, a growing body of evidence suggests that even short bursts of these drugs are associated with serious risks.

Most recently, a population-based study of more than 2.6 million people found that taking corticosteroids for 14 days or less was associated with a substantially greater risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis, and heart failure, particularly within the first 30 days after therapy.

In the study, Tsung-Chieh Yao, MD, PhD, a professor in the division of allergy, asthma, and rheumatology in the department of pediatrics at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taoyuan, Taiwan, and colleagues used a self-controlled case series to analyze data from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database of medical claims. They compared patients’ conditions in the period from 5 to 90 days before treatment to conditions from the periods from 5 to 30 days and from 31 to 90 days after therapy.

With a median duration of 3 days of treatment, the incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were 1.80 (95% confidence interval, 1.75-1.84) for GI bleeding, 1.99 (95% CI, 1.70-2.32) for sepsis, and 2.37 (95% CI, 2.13-2.63) for heart failure.

Given the findings, physicians should weigh the benefits against the risks of rare but potentially serious consequences of these anti-inflammatory drugs, according to the authors.

“After initiating patients on oral steroid bursts, physicians should be on the lookout for these severe adverse events, particularly within the first month after initiation of steroid therapy,” Dr. Yao said in an interview.

The findings were published online July 6 in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Of the 15,859,129 adult Asians in the Taiwanese database, the study included 2,623,327 adults aged 20-64 years who received single steroid bursts (14 days or less) between Jan. 1, 2013, and Dec. 31, 2015.

Almost 60% of the indications were for skin disorders, such as eczema and urticaria, and for respiratory tract infections, such as sinusitis and acute pharyngitis. Among specialties, dermatology, otolaryngology, family practice, internal medicine, and pediatrics accounted for 88% of prescriptions.

“Our findings are important for physicians and guideline developers because short-term use of oral corticosteroids is common and the real-world safety of this approach remains unclear,” the authors wrote. They acknowledged that the database did not provide information on such potential confounders as disease severity and lifestyle factors, nor did it include children and vulnerable individuals, which may limit the generalizability of the results.

The findings echo those of a 2017 cohort study conducted by researchers at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That study, by Akbar K. Waljee, MD, assistant professor of gastroenterology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues, included data on more than 1.5 million privately insured U.S. adults. The researchers included somewhat longer steroid bursts of up to 30 days’ duration and found that use of the drugs was associated with a greater than fivefold increased risk for sepsis, a more than threefold increased risk for venous thromboembolism, and a nearly twofold increased risk for fracture within 30 days of starting treatment.

Furthermore, the elevated risk persisted at prednisone-equivalent doses of less than 20 mg/d (IRR, 4.02 for sepsis, 3.61 for venous thromboembolism, and 1.83 for fracture; all P < .001).

The U.S. study also found that during the 3-year period from 2012 to 2014, more than 20% of patients were prescribed short-term oral corticosteroids.

“Both studies indicate that these short-term regimens are more common in the real world than was previously thought and are not risk free,” Dr. Yao said.

Recognition that corticosteroids are associated with adverse events has been building for decades, according to the authors of an editorial that accompanies the new study.

“However, we commonly use short corticosteroid ‘bursts’ for minor ailments despite a lack of evidence for meaningful benefit. We are now learning that bursts as short as 3 days may increase risk for serious AEs, even in young and healthy people,” wrote editorialists Beth I. Wallace, MD, of the Center for Clinical Management Research at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and the Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation at Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, and Dr. Waljee, who led the 2017 study.

Dr. Wallace and Dr. Waljee drew parallels between corticosteroid bursts and other short-term regimens, such as of antibiotics and opiates, in which prescriber preference and sometimes patient pressure play a role. “All of these treatments have well-defined indications but can cause net harm when used. We can thus conceive of a corticosteroid stewardship model of targeted interventions that aims to reduce inappropriate prescribing,” they wrote.

In an interview, Dr. Wallace, a rheumatologist who prescribes oral steroids fairly frequently, noted that the Taiwan study is the first to investigate steroid bursts. “Up till now, these very short courses have flown under the radar. Clinicians very commonly prescribe short courses to help relieve symptoms of self-limited conditions like bronchitis, and we assume that because the exposure duration is short, the risks are low, especially for patients who are otherwise healthy.”

She warned that the data in the current study indicate that these short bursts – even at the lower end of the 1- to 2-week courses American physicians prescribe most often – carry small but real increases in risk for serious AEs. “And these increases were seen in young, healthy people, not just in people with preexisting conditions,” she said. “So, we might need to start thinking harder about how we are prescribing even these very short courses of steroids and try to use steroids only when their meaningful benefits really outweigh the risk.”

She noted that a patient with a chronic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may benefit substantially from short-term steroids to treat a disease flare. In that specific case, the benefits of short-term steroids may outweigh the risks, Dr. Wallace said.

But not everyone thinks a new strategy is needed. For Whitney A. High, MD, associate professor of dermatology and pathology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, the overprescribing of short-term corticosteroids is not a problem, and dermatologists are already exercising caution.

“I only prescribe these drugs short term to, at a guess, about 1 in 40 patients and only when a patient is miserable and quality of life is being seriously affected,” he said in an interview. “And that’s something that can’t be measured in a database study like the one from Taiwan but only in a risk-benefit analysis,” he said.

Furthermore, dermatologists have other drugs and technologies in their armamentarium, including topical steroids with occlusion or with wet wraps, phototherapy, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, calcipotriene, methotrexate and other immunosuppressive agents, and biologics. “In fact, many of these agents are specifically referred to as steroid-sparing,” Dr. High said.

Nor does he experience much pressure from patients to prescribe these drugs. “While occasionally I may encounter a patient who places pressure on me for oral steroids, it’s probably not nearly as frequently as providers in other fields are pressured to prescribe antibiotics or narcotics,” he said.

According to the Taiwanese researchers, the next step is to conduct more studies, including clinical trials, to determine optimal use of corticosteroids by monitoring adverse events. In the meantime, for practitioners such as Dr. Wallace and Dr. High, there is ample evidence from several recent studies of the harms of short-term corticosteroids, whereas the benefits for patients with self-limiting conditions remain uncertain. “This and other studies like it quite appropriately remind providers to avoid oral steroids when they’re not necessary and to seek alternatives where possible,” Dr. High said.

The study was supported by the National Health Research Institutes of Taiwan, the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, the Chang Gung Medical Foundation, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Dr. Yao has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wu has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline outside the submitted work. The editorialists and Dr. High have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Wallace received an NIH grant during the writing of the editorial.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatric hospitalists convene virtually to discuss PHM designation

A recent teleconference brought together an ad hoc panel of pediatric hospitalists, with more than 100 diverse voices discussing whether there ought to be an additional professional recognition or designation for the subspecialty, apart from the new pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) board certification that was launched in 2019.

The heterogeneity of PHM was on display during the discussion, as participants included university-based pediatric hospitalists and those from community hospitals, physicians trained in combined medicine and pediatrics or in family medicine, doctors who completed a general pediatric residency before going straight into PHM, niche practitioners such as newborn hospitalists, trainees, and a small but growing number of graduates of PHM fellowship programs. There are 61 PHM fellowships, and these programs graduate approximately 70 new fellows per year.

Although a route to some kind of professional designation for PHM – separate from board certification – was the centerpiece of the conference call, there is no proposal actively under consideration for developing such a designation, said Weijen W. Chang, MD, FAAP, SFHM, chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts–Baystate Campus.

Who might develop such a proposal? “The hope is that the three major professional societies involved in pediatric hospital medicine – the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association – would jointly develop such a designation,” Dr. Chang said. However, it is not clear whether the three societies could agree on this. An online survey of 551 pediatric hospitalists, shared during the conference call, found that the majority would like to see some kind of alternate designation.

The reality of the boards

The pediatric subspecialty of PHM was recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties in 2015 following a petition by a group of PHM leaders seeking a way to credential their unique skill set. The first PHM board certification exam was offered by the American Board of Pediatrics on Nov. 12, 2019, with 1,491 hospitalists sitting for the exam and 84% passing. An estimated 4,000 pediatric hospitalists currently work in the field.

Certification as a subspecialty typically requires completing a fellowship, but new subspecialties often offer a “practice pathway” allowing those who already have experience working in the field to sit for the exam. A PHM practice pathway, and a combined fellowship and experience option for those whose fellowship training was less than 2 years, was offered for last year’s exam and will be offered again in 2021 and 2023. After that, board certification will only be available to graduates of recognized fellowships.

But concerns began to emerge last summer in advance of ABM’s initial PHM board exam, when some applicants were told that they weren’t eligible to sit for it, said H. Barrett Fromme, MD, associate dean for faculty development in medical education and section chief for pediatric hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. She also chairs the section of hospital medicine for the AAP.

Concerns including unintended gender bias against women, such as those hospitalists whose training is interrupted for maternity leave, were raised in a petition to ABP. The board promptly responded that gender bias was not supported by the facts, although its response did not account for selection bias in the data. But the ABP removed its practice interruption criteria.1,2

There are various reasons why a pediatric hospitalist might not be able or willing to pursue a 2-year fellowship or otherwise qualify for certification, Dr. Fromme said, including time and cost. For some, the practice pathway’s requirements, including a minimum number of hours worked in pediatrics in the previous 4 years, may be impossible to meet. Pediatric hospitalists boarded in family medicine are not eligible.

For hospitalists who can’t achieve board certification, what might that mean in terms of their future salary, employment opportunities, reimbursement, other career goals? Might they find themselves unable to qualify for PHM jobs at some university-based medical centers? The answers are not yet known.

What might self-designation look like?

PHM is distinct from adult hospital medicine by virtue of its designation as a board-certified subspecialty. But it can look to the broader HM field for examples of designations that bestow a kind of professional recognition, Dr. Chang said. These include SHM’s merit-based Fellow in Hospital Medicine program and the American Board of Medical Specialties’ Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine, a pathway for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine, he said.

But PHM self-designation is not necessarily a pathway to hospital privileges. “If we build it, will they come? If they come, will it mean anything to them? That’s the million-dollar question?” Dr. Chang said.

Hospitalists need to appreciate that this issue is important to all three PHM professional societies, SHM, AAP, and APA, Dr. Fromme said. “We are concerned about how to support all of our members – certified, noncertified, nonphysician. Alternate designation is one idea, but we need time to understand it. We need a lot more conversations and a lot of people thinking about it.”

Dr. Fromme is part of the Council on Pediatric Hospital Medicine, a small circle of leaders of PHM interest groups within the three professional associations. It meets quarterly and will be reviewing the results of the conference call.

“I personally think we don’t understand the scope of the problem or the needs of pediatric hospitalists who are not able to sit for boards or pursue a fellowship,” she said. “We have empathy and concern for our colleagues who can’t take the boards. We don’t want them to feel excluded, and that includes advanced practice nurses and residents. But does an alternative designation actually provide what people think it provides?”

There are other ways to demonstrate that professionals are engaged with and serious about developing their practice. If they are looking to better themselves at quality improvement, leadership, education, and other elements of PHM practice, the associations can endeavor to provide more educational opportunities, Dr. Fromme said. “But if it’s about how they look as a candidate for hire, relative to board-certified candidates, that’s a different beast, and we need to think about what can help them the most.”

References

1. American Board of Pediatrics, Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition. 2019 Aug 20. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf.

2. Chang WW et al. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90.

A recent teleconference brought together an ad hoc panel of pediatric hospitalists, with more than 100 diverse voices discussing whether there ought to be an additional professional recognition or designation for the subspecialty, apart from the new pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) board certification that was launched in 2019.

The heterogeneity of PHM was on display during the discussion, as participants included university-based pediatric hospitalists and those from community hospitals, physicians trained in combined medicine and pediatrics or in family medicine, doctors who completed a general pediatric residency before going straight into PHM, niche practitioners such as newborn hospitalists, trainees, and a small but growing number of graduates of PHM fellowship programs. There are 61 PHM fellowships, and these programs graduate approximately 70 new fellows per year.

Although a route to some kind of professional designation for PHM – separate from board certification – was the centerpiece of the conference call, there is no proposal actively under consideration for developing such a designation, said Weijen W. Chang, MD, FAAP, SFHM, chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts–Baystate Campus.

Who might develop such a proposal? “The hope is that the three major professional societies involved in pediatric hospital medicine – the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association – would jointly develop such a designation,” Dr. Chang said. However, it is not clear whether the three societies could agree on this. An online survey of 551 pediatric hospitalists, shared during the conference call, found that the majority would like to see some kind of alternate designation.

The reality of the boards

The pediatric subspecialty of PHM was recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties in 2015 following a petition by a group of PHM leaders seeking a way to credential their unique skill set. The first PHM board certification exam was offered by the American Board of Pediatrics on Nov. 12, 2019, with 1,491 hospitalists sitting for the exam and 84% passing. An estimated 4,000 pediatric hospitalists currently work in the field.

Certification as a subspecialty typically requires completing a fellowship, but new subspecialties often offer a “practice pathway” allowing those who already have experience working in the field to sit for the exam. A PHM practice pathway, and a combined fellowship and experience option for those whose fellowship training was less than 2 years, was offered for last year’s exam and will be offered again in 2021 and 2023. After that, board certification will only be available to graduates of recognized fellowships.

But concerns began to emerge last summer in advance of ABM’s initial PHM board exam, when some applicants were told that they weren’t eligible to sit for it, said H. Barrett Fromme, MD, associate dean for faculty development in medical education and section chief for pediatric hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. She also chairs the section of hospital medicine for the AAP.

Concerns including unintended gender bias against women, such as those hospitalists whose training is interrupted for maternity leave, were raised in a petition to ABP. The board promptly responded that gender bias was not supported by the facts, although its response did not account for selection bias in the data. But the ABP removed its practice interruption criteria.1,2

There are various reasons why a pediatric hospitalist might not be able or willing to pursue a 2-year fellowship or otherwise qualify for certification, Dr. Fromme said, including time and cost. For some, the practice pathway’s requirements, including a minimum number of hours worked in pediatrics in the previous 4 years, may be impossible to meet. Pediatric hospitalists boarded in family medicine are not eligible.

For hospitalists who can’t achieve board certification, what might that mean in terms of their future salary, employment opportunities, reimbursement, other career goals? Might they find themselves unable to qualify for PHM jobs at some university-based medical centers? The answers are not yet known.

What might self-designation look like?

PHM is distinct from adult hospital medicine by virtue of its designation as a board-certified subspecialty. But it can look to the broader HM field for examples of designations that bestow a kind of professional recognition, Dr. Chang said. These include SHM’s merit-based Fellow in Hospital Medicine program and the American Board of Medical Specialties’ Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine, a pathway for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine, he said.

But PHM self-designation is not necessarily a pathway to hospital privileges. “If we build it, will they come? If they come, will it mean anything to them? That’s the million-dollar question?” Dr. Chang said.

Hospitalists need to appreciate that this issue is important to all three PHM professional societies, SHM, AAP, and APA, Dr. Fromme said. “We are concerned about how to support all of our members – certified, noncertified, nonphysician. Alternate designation is one idea, but we need time to understand it. We need a lot more conversations and a lot of people thinking about it.”

Dr. Fromme is part of the Council on Pediatric Hospital Medicine, a small circle of leaders of PHM interest groups within the three professional associations. It meets quarterly and will be reviewing the results of the conference call.

“I personally think we don’t understand the scope of the problem or the needs of pediatric hospitalists who are not able to sit for boards or pursue a fellowship,” she said. “We have empathy and concern for our colleagues who can’t take the boards. We don’t want them to feel excluded, and that includes advanced practice nurses and residents. But does an alternative designation actually provide what people think it provides?”

There are other ways to demonstrate that professionals are engaged with and serious about developing their practice. If they are looking to better themselves at quality improvement, leadership, education, and other elements of PHM practice, the associations can endeavor to provide more educational opportunities, Dr. Fromme said. “But if it’s about how they look as a candidate for hire, relative to board-certified candidates, that’s a different beast, and we need to think about what can help them the most.”

References

1. American Board of Pediatrics, Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition. 2019 Aug 20. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf.

2. Chang WW et al. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90.

A recent teleconference brought together an ad hoc panel of pediatric hospitalists, with more than 100 diverse voices discussing whether there ought to be an additional professional recognition or designation for the subspecialty, apart from the new pediatric hospital medicine (PHM) board certification that was launched in 2019.

The heterogeneity of PHM was on display during the discussion, as participants included university-based pediatric hospitalists and those from community hospitals, physicians trained in combined medicine and pediatrics or in family medicine, doctors who completed a general pediatric residency before going straight into PHM, niche practitioners such as newborn hospitalists, trainees, and a small but growing number of graduates of PHM fellowship programs. There are 61 PHM fellowships, and these programs graduate approximately 70 new fellows per year.

Although a route to some kind of professional designation for PHM – separate from board certification – was the centerpiece of the conference call, there is no proposal actively under consideration for developing such a designation, said Weijen W. Chang, MD, FAAP, SFHM, chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass., and associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts–Baystate Campus.

Who might develop such a proposal? “The hope is that the three major professional societies involved in pediatric hospital medicine – the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association – would jointly develop such a designation,” Dr. Chang said. However, it is not clear whether the three societies could agree on this. An online survey of 551 pediatric hospitalists, shared during the conference call, found that the majority would like to see some kind of alternate designation.

The reality of the boards

The pediatric subspecialty of PHM was recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties in 2015 following a petition by a group of PHM leaders seeking a way to credential their unique skill set. The first PHM board certification exam was offered by the American Board of Pediatrics on Nov. 12, 2019, with 1,491 hospitalists sitting for the exam and 84% passing. An estimated 4,000 pediatric hospitalists currently work in the field.

Certification as a subspecialty typically requires completing a fellowship, but new subspecialties often offer a “practice pathway” allowing those who already have experience working in the field to sit for the exam. A PHM practice pathway, and a combined fellowship and experience option for those whose fellowship training was less than 2 years, was offered for last year’s exam and will be offered again in 2021 and 2023. After that, board certification will only be available to graduates of recognized fellowships.

But concerns began to emerge last summer in advance of ABM’s initial PHM board exam, when some applicants were told that they weren’t eligible to sit for it, said H. Barrett Fromme, MD, associate dean for faculty development in medical education and section chief for pediatric hospital medicine at the University of Chicago. She also chairs the section of hospital medicine for the AAP.

Concerns including unintended gender bias against women, such as those hospitalists whose training is interrupted for maternity leave, were raised in a petition to ABP. The board promptly responded that gender bias was not supported by the facts, although its response did not account for selection bias in the data. But the ABP removed its practice interruption criteria.1,2

There are various reasons why a pediatric hospitalist might not be able or willing to pursue a 2-year fellowship or otherwise qualify for certification, Dr. Fromme said, including time and cost. For some, the practice pathway’s requirements, including a minimum number of hours worked in pediatrics in the previous 4 years, may be impossible to meet. Pediatric hospitalists boarded in family medicine are not eligible.

For hospitalists who can’t achieve board certification, what might that mean in terms of their future salary, employment opportunities, reimbursement, other career goals? Might they find themselves unable to qualify for PHM jobs at some university-based medical centers? The answers are not yet known.

What might self-designation look like?

PHM is distinct from adult hospital medicine by virtue of its designation as a board-certified subspecialty. But it can look to the broader HM field for examples of designations that bestow a kind of professional recognition, Dr. Chang said. These include SHM’s merit-based Fellow in Hospital Medicine program and the American Board of Medical Specialties’ Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine, a pathway for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine, he said.

But PHM self-designation is not necessarily a pathway to hospital privileges. “If we build it, will they come? If they come, will it mean anything to them? That’s the million-dollar question?” Dr. Chang said.

Hospitalists need to appreciate that this issue is important to all three PHM professional societies, SHM, AAP, and APA, Dr. Fromme said. “We are concerned about how to support all of our members – certified, noncertified, nonphysician. Alternate designation is one idea, but we need time to understand it. We need a lot more conversations and a lot of people thinking about it.”

Dr. Fromme is part of the Council on Pediatric Hospital Medicine, a small circle of leaders of PHM interest groups within the three professional associations. It meets quarterly and will be reviewing the results of the conference call.

“I personally think we don’t understand the scope of the problem or the needs of pediatric hospitalists who are not able to sit for boards or pursue a fellowship,” she said. “We have empathy and concern for our colleagues who can’t take the boards. We don’t want them to feel excluded, and that includes advanced practice nurses and residents. But does an alternative designation actually provide what people think it provides?”

There are other ways to demonstrate that professionals are engaged with and serious about developing their practice. If they are looking to better themselves at quality improvement, leadership, education, and other elements of PHM practice, the associations can endeavor to provide more educational opportunities, Dr. Fromme said. “But if it’s about how they look as a candidate for hire, relative to board-certified candidates, that’s a different beast, and we need to think about what can help them the most.”

References

1. American Board of Pediatrics, Response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine Petition. 2019 Aug 20. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf.

2. Chang WW et al. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90.

Sorting out the many mimickers of psoriasis

“It has an earlier age of onset, usually in infancy, and can occur with the atopic triad that presents with asthma and seasonal allergies as well,” Israel David “Izzy” Andrews, MD, said at the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “There is typically a very strong family history, as this is an autosomal dominant condition, and it’s far more common than psoriasis. The annual incidence is estimated to be 10%-15% of pediatric patients. It has classic areas of involvement depending on the age of the patient, and lesions are intensely pruritic at all times. There is induration and crust, but it’s important to distinguish crust from scale. Whereas crust is dried exudate, and scale is usually secondary to a hyperproliferation of the skin. Initially, treatments (especially topical) are similar and may also delay the formalized diagnosis of either of the two.”

Another psoriasis mimicker, pityriasis rosea, is thought to be secondary to human herpes virus 6 or 7 infection, said Dr. Andrews, of the department of dermatology at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. It typically appears in the teens and tweens and usually presents as a large herald patch or plaque on the trunk. As the herald patch resolves, smaller lesions will develop on the trunk following skin folds. “It’s rarely symptomatic and it’s very short lived, and clears within 6-12 weeks,” Dr. Andrews noted. “It can present with an inverse pattern involving the face, neck, and groin, but sparing the trunk. This variant, termed inverse pityriasis rosea, can be confused with inverse psoriasis, which has a similar distribution. However, the inverse pattern of pityriasis rosea will still resolve in a similar time frame to its more classic variant.”

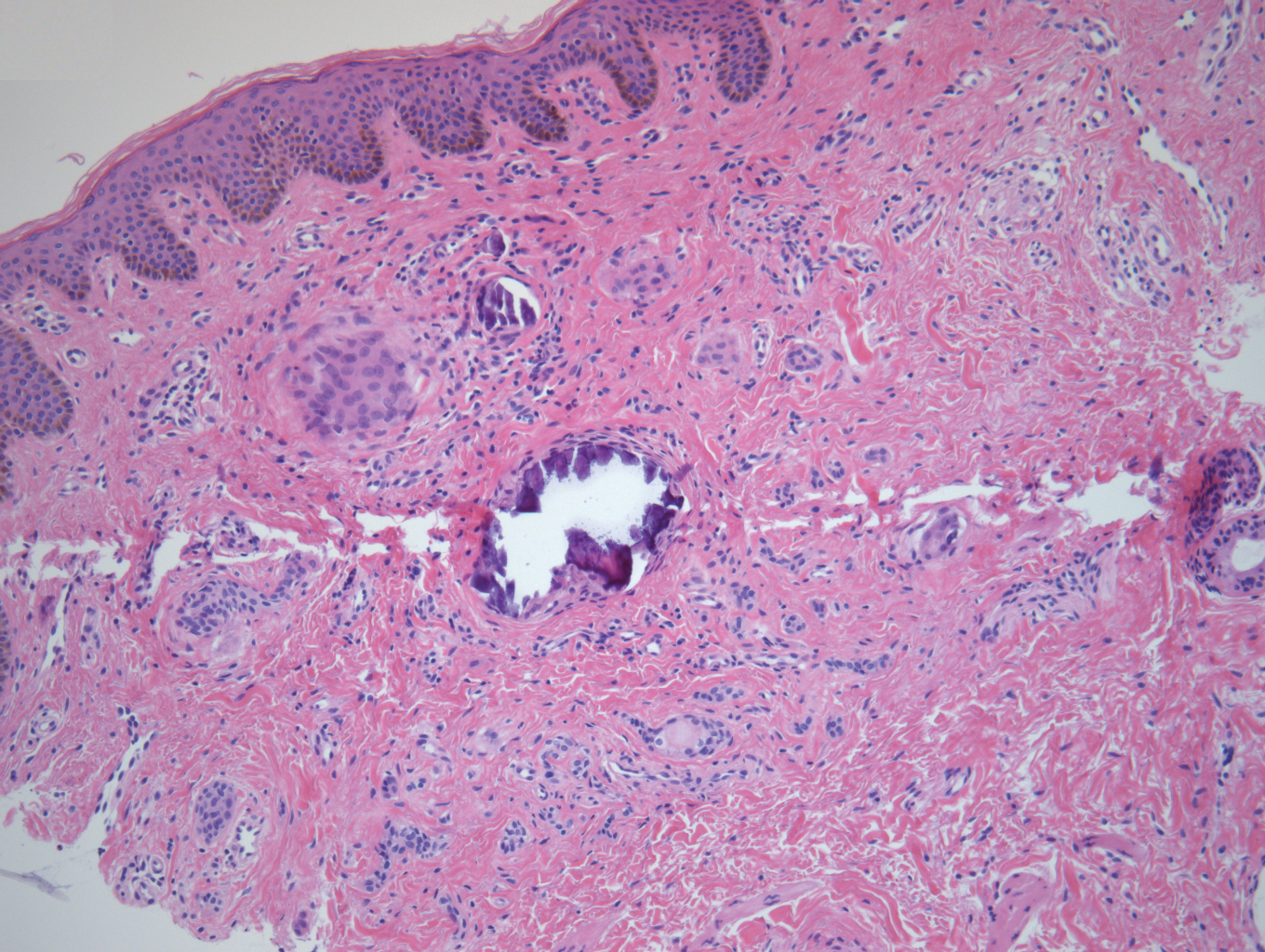

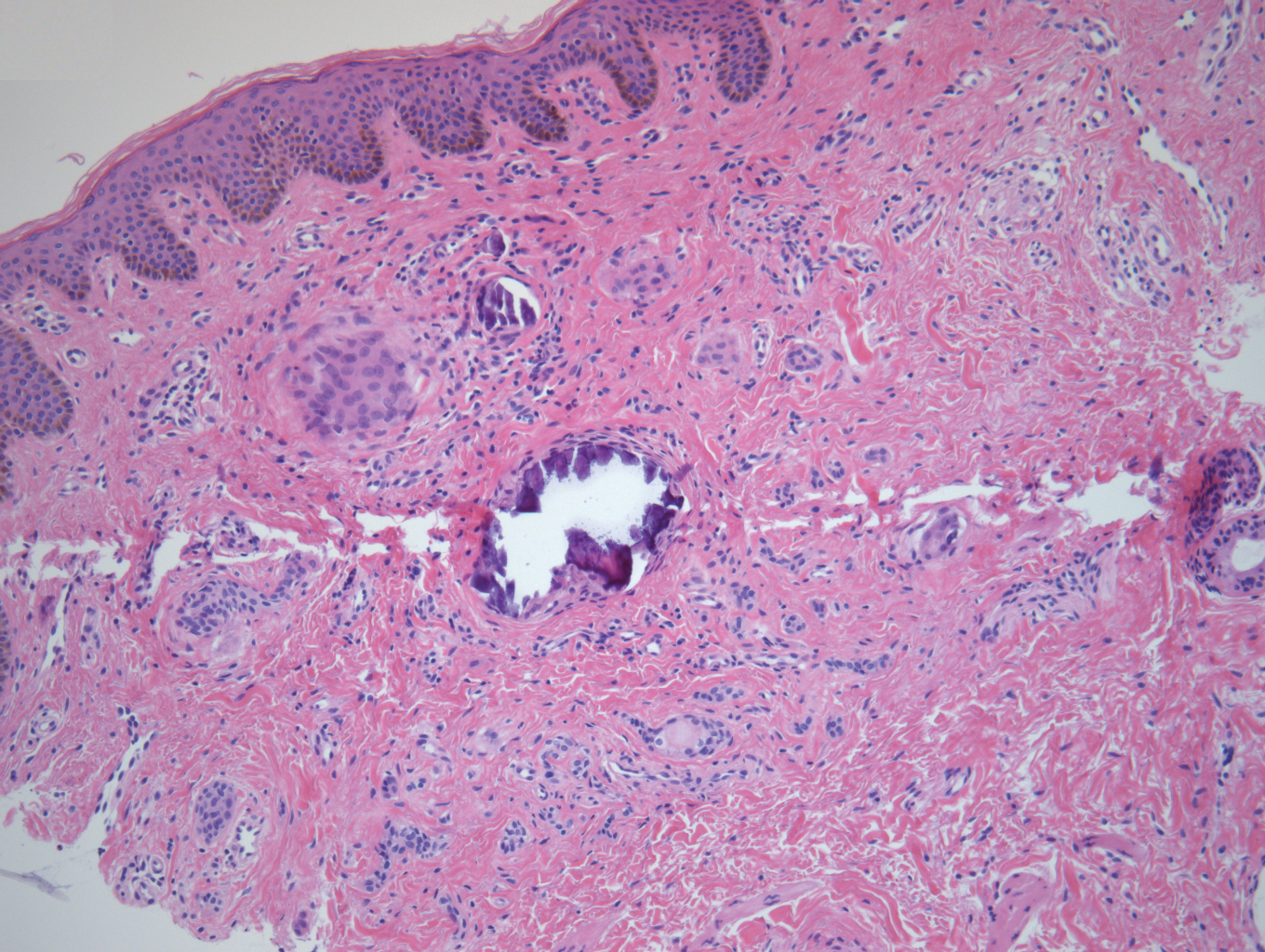

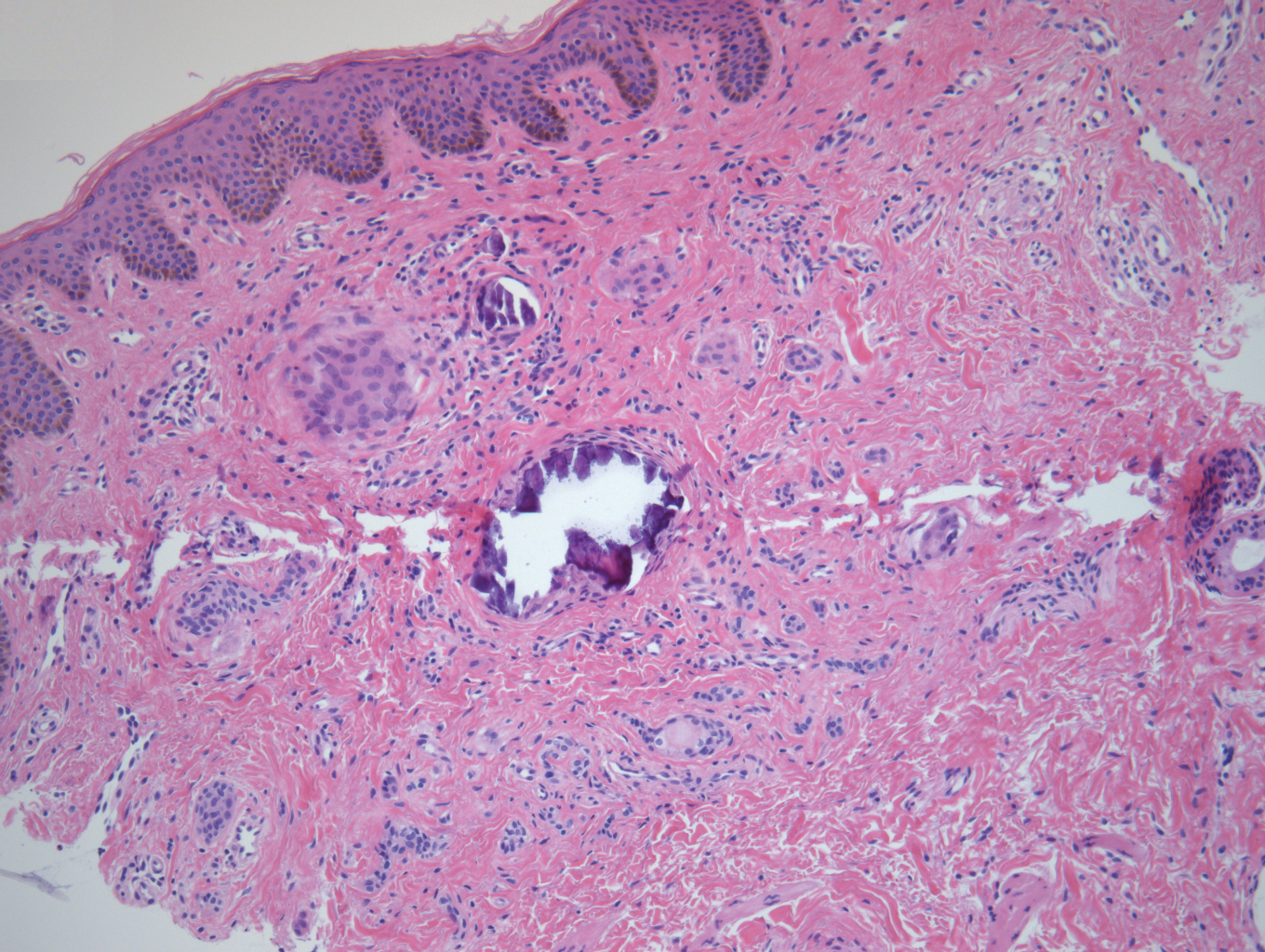

Pityriasis lichenoides can also be mistaken for psoriasis. The acute form can present with erythematous, scaly papules and plaques, but lesions are often found in different phases of resolution or healing. “This benign lymphoproliferative skin disorder can be very difficult to distinguish from psoriasis and may require a biopsy to rule in or out,” Dr. Andrews said. “It can last months to years and there are few treatments that are effective. It is typically nonresponsive to topical steroids and other treatments that would be more effective for psoriasis, helping to distinguish the two. It is thought to exist in the spectrum with other lymphoproliferative diseases including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [CTCL]. However, there are only a few cases in the literature that support a transformation from pityriasis lichenoides to CTCL.”

Seborrheic dermatitis is more common than atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but it can be mistaken for psoriasis. It is caused by an inflammatory response secondary to overgrowth of Malassezia yeast and has a bimodal age distribution. “Seborrheic dermatitis affects babies, teens, and tweens, and can persist into adulthood,” he said. “Infants with cradle cap usually resolve with moisturization, gentle brushing, and occasional antifungal shampoos.” Petaloid seborrheic dermatitis can predominately involve the face with psoriatic-appearing induration, plaques, and varying degrees of scales. “In skin of color, this can be confused with discoid lupus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis, occasionally requiring a biopsy to distinguish,” said Dr. Andrews, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Another psoriasis mimicker, pityriasis amiantacea, is thought to be a more severe form of seborrheic dermatitis. It presents with concretions of scale around hair follicles that are highly adherent and are sometimes called sebopsoriasis. “It may be associated with cutaneous findings of psoriasis elsewhere, but may also be found with secondarily infected atopic dermatitis and tinea capitis; however, in my clinical experience, it is most often found in isolation,” he said. “There may be a seasonal association with exacerbation in warm temperatures, and treatment often consists of humectants like salicylic acid for loosening scale, topical steroids for inflammation, and gentle combing out of scale.”

Infections can also mimic psoriasis. For example, tinea infections are often misdiagnosed as eczema or psoriasis and treated with topical steroids. “This can lead to tinea incognito, making it harder to diagnose either condition without attention to detail,” Dr. Andrews said. “On the body, look for expanding lesions with more raised peripheral edges, and central flattening, giving a classic annular appearance. It’s also important to inquire about family history and contacts including pets, contact sports/mat sports (think yoga, gymnastics, martial arts), or other contacts with similar rashes.” Work-up typically includes a fungal culture and starting empiric oral antifungal medications. “It is important to be able to distinguish scalp psoriasis from tinea capitis to prevent the more inflammatory form of tinea capitis, kerion (a deeper more symptomatic, painful and purulent dermatitis), which can lead to permanent scarring alopecia,” he said.

Bacterial infections can also mimic psoriasis, specifically nonbullous impetigo and ecthyma, the more ulcerative form of impetigo. The most frequent associations are group A Streptococcus, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Dr. Andrews closed his presentation by noting that tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasiform drug eruptions can occur in psoriasis-naive patients or unmask a predilection for psoriasis in patients with Crohn’s disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or other autoinflammatory or autoimmune conditions. “They may improve with continued treatment and resolve with switching treatments,” he said. “Early biopsy in psoriasiform drug eruptions can appear like atopic dermatitis on pathology. When suspecting psoriasis in a pediatric patient, it is important to consider the history and physical exam as well as family history and associated comorbidities. While a biopsy may aide in the work-up, diagnosis can be made clinically.”

Dr. Andrews reported having no financial disclosures.

“It has an earlier age of onset, usually in infancy, and can occur with the atopic triad that presents with asthma and seasonal allergies as well,” Israel David “Izzy” Andrews, MD, said at the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “There is typically a very strong family history, as this is an autosomal dominant condition, and it’s far more common than psoriasis. The annual incidence is estimated to be 10%-15% of pediatric patients. It has classic areas of involvement depending on the age of the patient, and lesions are intensely pruritic at all times. There is induration and crust, but it’s important to distinguish crust from scale. Whereas crust is dried exudate, and scale is usually secondary to a hyperproliferation of the skin. Initially, treatments (especially topical) are similar and may also delay the formalized diagnosis of either of the two.”

Another psoriasis mimicker, pityriasis rosea, is thought to be secondary to human herpes virus 6 or 7 infection, said Dr. Andrews, of the department of dermatology at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. It typically appears in the teens and tweens and usually presents as a large herald patch or plaque on the trunk. As the herald patch resolves, smaller lesions will develop on the trunk following skin folds. “It’s rarely symptomatic and it’s very short lived, and clears within 6-12 weeks,” Dr. Andrews noted. “It can present with an inverse pattern involving the face, neck, and groin, but sparing the trunk. This variant, termed inverse pityriasis rosea, can be confused with inverse psoriasis, which has a similar distribution. However, the inverse pattern of pityriasis rosea will still resolve in a similar time frame to its more classic variant.”

Pityriasis lichenoides can also be mistaken for psoriasis. The acute form can present with erythematous, scaly papules and plaques, but lesions are often found in different phases of resolution or healing. “This benign lymphoproliferative skin disorder can be very difficult to distinguish from psoriasis and may require a biopsy to rule in or out,” Dr. Andrews said. “It can last months to years and there are few treatments that are effective. It is typically nonresponsive to topical steroids and other treatments that would be more effective for psoriasis, helping to distinguish the two. It is thought to exist in the spectrum with other lymphoproliferative diseases including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [CTCL]. However, there are only a few cases in the literature that support a transformation from pityriasis lichenoides to CTCL.”

Seborrheic dermatitis is more common than atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but it can be mistaken for psoriasis. It is caused by an inflammatory response secondary to overgrowth of Malassezia yeast and has a bimodal age distribution. “Seborrheic dermatitis affects babies, teens, and tweens, and can persist into adulthood,” he said. “Infants with cradle cap usually resolve with moisturization, gentle brushing, and occasional antifungal shampoos.” Petaloid seborrheic dermatitis can predominately involve the face with psoriatic-appearing induration, plaques, and varying degrees of scales. “In skin of color, this can be confused with discoid lupus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis, occasionally requiring a biopsy to distinguish,” said Dr. Andrews, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Another psoriasis mimicker, pityriasis amiantacea, is thought to be a more severe form of seborrheic dermatitis. It presents with concretions of scale around hair follicles that are highly adherent and are sometimes called sebopsoriasis. “It may be associated with cutaneous findings of psoriasis elsewhere, but may also be found with secondarily infected atopic dermatitis and tinea capitis; however, in my clinical experience, it is most often found in isolation,” he said. “There may be a seasonal association with exacerbation in warm temperatures, and treatment often consists of humectants like salicylic acid for loosening scale, topical steroids for inflammation, and gentle combing out of scale.”

Infections can also mimic psoriasis. For example, tinea infections are often misdiagnosed as eczema or psoriasis and treated with topical steroids. “This can lead to tinea incognito, making it harder to diagnose either condition without attention to detail,” Dr. Andrews said. “On the body, look for expanding lesions with more raised peripheral edges, and central flattening, giving a classic annular appearance. It’s also important to inquire about family history and contacts including pets, contact sports/mat sports (think yoga, gymnastics, martial arts), or other contacts with similar rashes.” Work-up typically includes a fungal culture and starting empiric oral antifungal medications. “It is important to be able to distinguish scalp psoriasis from tinea capitis to prevent the more inflammatory form of tinea capitis, kerion (a deeper more symptomatic, painful and purulent dermatitis), which can lead to permanent scarring alopecia,” he said.

Bacterial infections can also mimic psoriasis, specifically nonbullous impetigo and ecthyma, the more ulcerative form of impetigo. The most frequent associations are group A Streptococcus, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Dr. Andrews closed his presentation by noting that tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasiform drug eruptions can occur in psoriasis-naive patients or unmask a predilection for psoriasis in patients with Crohn’s disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or other autoinflammatory or autoimmune conditions. “They may improve with continued treatment and resolve with switching treatments,” he said. “Early biopsy in psoriasiform drug eruptions can appear like atopic dermatitis on pathology. When suspecting psoriasis in a pediatric patient, it is important to consider the history and physical exam as well as family history and associated comorbidities. While a biopsy may aide in the work-up, diagnosis can be made clinically.”

Dr. Andrews reported having no financial disclosures.

“It has an earlier age of onset, usually in infancy, and can occur with the atopic triad that presents with asthma and seasonal allergies as well,” Israel David “Izzy” Andrews, MD, said at the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “There is typically a very strong family history, as this is an autosomal dominant condition, and it’s far more common than psoriasis. The annual incidence is estimated to be 10%-15% of pediatric patients. It has classic areas of involvement depending on the age of the patient, and lesions are intensely pruritic at all times. There is induration and crust, but it’s important to distinguish crust from scale. Whereas crust is dried exudate, and scale is usually secondary to a hyperproliferation of the skin. Initially, treatments (especially topical) are similar and may also delay the formalized diagnosis of either of the two.”

Another psoriasis mimicker, pityriasis rosea, is thought to be secondary to human herpes virus 6 or 7 infection, said Dr. Andrews, of the department of dermatology at Phoenix Children’s Hospital. It typically appears in the teens and tweens and usually presents as a large herald patch or plaque on the trunk. As the herald patch resolves, smaller lesions will develop on the trunk following skin folds. “It’s rarely symptomatic and it’s very short lived, and clears within 6-12 weeks,” Dr. Andrews noted. “It can present with an inverse pattern involving the face, neck, and groin, but sparing the trunk. This variant, termed inverse pityriasis rosea, can be confused with inverse psoriasis, which has a similar distribution. However, the inverse pattern of pityriasis rosea will still resolve in a similar time frame to its more classic variant.”

Pityriasis lichenoides can also be mistaken for psoriasis. The acute form can present with erythematous, scaly papules and plaques, but lesions are often found in different phases of resolution or healing. “This benign lymphoproliferative skin disorder can be very difficult to distinguish from psoriasis and may require a biopsy to rule in or out,” Dr. Andrews said. “It can last months to years and there are few treatments that are effective. It is typically nonresponsive to topical steroids and other treatments that would be more effective for psoriasis, helping to distinguish the two. It is thought to exist in the spectrum with other lymphoproliferative diseases including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [CTCL]. However, there are only a few cases in the literature that support a transformation from pityriasis lichenoides to CTCL.”

Seborrheic dermatitis is more common than atopic dermatitis and psoriasis, but it can be mistaken for psoriasis. It is caused by an inflammatory response secondary to overgrowth of Malassezia yeast and has a bimodal age distribution. “Seborrheic dermatitis affects babies, teens, and tweens, and can persist into adulthood,” he said. “Infants with cradle cap usually resolve with moisturization, gentle brushing, and occasional antifungal shampoos.” Petaloid seborrheic dermatitis can predominately involve the face with psoriatic-appearing induration, plaques, and varying degrees of scales. “In skin of color, this can be confused with discoid lupus, sarcoidosis, and psoriasis, occasionally requiring a biopsy to distinguish,” said Dr. Andrews, who is also an assistant professor of pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Another psoriasis mimicker, pityriasis amiantacea, is thought to be a more severe form of seborrheic dermatitis. It presents with concretions of scale around hair follicles that are highly adherent and are sometimes called sebopsoriasis. “It may be associated with cutaneous findings of psoriasis elsewhere, but may also be found with secondarily infected atopic dermatitis and tinea capitis; however, in my clinical experience, it is most often found in isolation,” he said. “There may be a seasonal association with exacerbation in warm temperatures, and treatment often consists of humectants like salicylic acid for loosening scale, topical steroids for inflammation, and gentle combing out of scale.”

Infections can also mimic psoriasis. For example, tinea infections are often misdiagnosed as eczema or psoriasis and treated with topical steroids. “This can lead to tinea incognito, making it harder to diagnose either condition without attention to detail,” Dr. Andrews said. “On the body, look for expanding lesions with more raised peripheral edges, and central flattening, giving a classic annular appearance. It’s also important to inquire about family history and contacts including pets, contact sports/mat sports (think yoga, gymnastics, martial arts), or other contacts with similar rashes.” Work-up typically includes a fungal culture and starting empiric oral antifungal medications. “It is important to be able to distinguish scalp psoriasis from tinea capitis to prevent the more inflammatory form of tinea capitis, kerion (a deeper more symptomatic, painful and purulent dermatitis), which can lead to permanent scarring alopecia,” he said.

Bacterial infections can also mimic psoriasis, specifically nonbullous impetigo and ecthyma, the more ulcerative form of impetigo. The most frequent associations are group A Streptococcus, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Dr. Andrews closed his presentation by noting that tumor necrosis factor–alpha inhibitor–induced psoriasiform drug eruptions can occur in psoriasis-naive patients or unmask a predilection for psoriasis in patients with Crohn’s disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, or other autoinflammatory or autoimmune conditions. “They may improve with continued treatment and resolve with switching treatments,” he said. “Early biopsy in psoriasiform drug eruptions can appear like atopic dermatitis on pathology. When suspecting psoriasis in a pediatric patient, it is important to consider the history and physical exam as well as family history and associated comorbidities. While a biopsy may aide in the work-up, diagnosis can be made clinically.”

Dr. Andrews reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY 2020

Expert shares his approach to treating warts in children

In the clinical experience of Anthony J. Mancini, MD, one option for children and adolescents who present with common warts is to do nothing, since they may resolve on their own.

“Many effective treatments that we have are painful and poorly tolerated, especially in younger children,” Dr. Mancini, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “However, while they’re harmless and often self-limited, warts often form a social stigma, and parents often desire therapy.”

Even though warts may spontaneously resolve in up to 65% of patients at 2 years and 80% at 4 years, the goals of treatment are to eradicate them, minimize pain, avoid scarring, and help prevent recurrence.

One effective topical therapy he highlighted is WartPEEL cream, which is a proprietary, compounded formulation of 17% salicylic acid and 2% 5-fluorouracil. “It’s in a sustained release vehicle called Remedium, and is available from a compounding pharmacy, but not FDA approved,” said Dr. Mancini, who is also head of pediatric dermatology at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. “It’s applied nightly with plastic tape occlusion and rinsed off each morning.”

WartPEEL is available through NuCara Pharmacy at 877-268-2272. It is not covered by most insurance plans and it costs around $80. “It is very effective, tends to be totally painless, and has a much quicker response than over-the-counter salicylic acid-based treatments for warts,” he said.

Another treatment option is oral cimetidine, especially in patients who have multiple or recalcitrant warts. The recommended dosing is 30-40 mg/kg per day, divided into twice-daily dosing. “You have to give it for at least 8-12 weeks to determine whether it’s working or not,” Dr. Mancini said. “In the initial report, [investigators] described an 81% complete response rate, but subsequent randomized, controlled trials were not able to confirm that data against placebo or topical treatments. I will say, though, that cimetidine is well tolerated. It’s always worth a try but, if you do use it, always consider other medications the patient may be taking and potential drug-drug interactions.”

For flat warts, verrucous papules that commonly occur on the face, Dr. Mancini recommends off-label treatment with 5% 5-fluorouracil cream (Efudex), which is normally indicated for actinic keratoses in adults. “I have patients apply this for 3 nights per week and work their way up gradually to nightly application,” he said. “It’s really important that parents and patients understand the importance of sun protection when they’re using Efudex, and they need to know that some irritation is possible. Overall, this treatment seems to be very well tolerated.”

Other treatment options for common warts, in addition to over-the-counter products that contain salicylic acid, are home cryotherapy kits that contain a mixture of diethyl ether and propane. “These can be effective for small warts,” Dr. Mancini said. “But for larger, thicker lesions, they’re not going to quite as effective.”

Treatment options best reserved for dermatologists, he continued, include in-office liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, “if it’s tolerated,” he said. “I have a no-hold policy, so if we have to hold a child down who’s flailing and crying and screaming during treatment, we’re probably not going to use liquid nitrogen.” He also mentioned topical immunotherapy with agents like squaric acid dibutylester. “This is almost like putting poison ivy on your warts to get the immune system revved up,” he said. “It can be very effective.” Other treatment options include intralesional immune therapy, topical cidofovir, and even pulsed-dye laser.

Dr. Mancini disclosed that he is a consultant to and a member of the scientific advisory board for Verrica Pharmaceuticals.

In the clinical experience of Anthony J. Mancini, MD, one option for children and adolescents who present with common warts is to do nothing, since they may resolve on their own.

“Many effective treatments that we have are painful and poorly tolerated, especially in younger children,” Dr. Mancini, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “However, while they’re harmless and often self-limited, warts often form a social stigma, and parents often desire therapy.”

Even though warts may spontaneously resolve in up to 65% of patients at 2 years and 80% at 4 years, the goals of treatment are to eradicate them, minimize pain, avoid scarring, and help prevent recurrence.

One effective topical therapy he highlighted is WartPEEL cream, which is a proprietary, compounded formulation of 17% salicylic acid and 2% 5-fluorouracil. “It’s in a sustained release vehicle called Remedium, and is available from a compounding pharmacy, but not FDA approved,” said Dr. Mancini, who is also head of pediatric dermatology at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. “It’s applied nightly with plastic tape occlusion and rinsed off each morning.”

WartPEEL is available through NuCara Pharmacy at 877-268-2272. It is not covered by most insurance plans and it costs around $80. “It is very effective, tends to be totally painless, and has a much quicker response than over-the-counter salicylic acid-based treatments for warts,” he said.

Another treatment option is oral cimetidine, especially in patients who have multiple or recalcitrant warts. The recommended dosing is 30-40 mg/kg per day, divided into twice-daily dosing. “You have to give it for at least 8-12 weeks to determine whether it’s working or not,” Dr. Mancini said. “In the initial report, [investigators] described an 81% complete response rate, but subsequent randomized, controlled trials were not able to confirm that data against placebo or topical treatments. I will say, though, that cimetidine is well tolerated. It’s always worth a try but, if you do use it, always consider other medications the patient may be taking and potential drug-drug interactions.”

For flat warts, verrucous papules that commonly occur on the face, Dr. Mancini recommends off-label treatment with 5% 5-fluorouracil cream (Efudex), which is normally indicated for actinic keratoses in adults. “I have patients apply this for 3 nights per week and work their way up gradually to nightly application,” he said. “It’s really important that parents and patients understand the importance of sun protection when they’re using Efudex, and they need to know that some irritation is possible. Overall, this treatment seems to be very well tolerated.”

Other treatment options for common warts, in addition to over-the-counter products that contain salicylic acid, are home cryotherapy kits that contain a mixture of diethyl ether and propane. “These can be effective for small warts,” Dr. Mancini said. “But for larger, thicker lesions, they’re not going to quite as effective.”

Treatment options best reserved for dermatologists, he continued, include in-office liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, “if it’s tolerated,” he said. “I have a no-hold policy, so if we have to hold a child down who’s flailing and crying and screaming during treatment, we’re probably not going to use liquid nitrogen.” He also mentioned topical immunotherapy with agents like squaric acid dibutylester. “This is almost like putting poison ivy on your warts to get the immune system revved up,” he said. “It can be very effective.” Other treatment options include intralesional immune therapy, topical cidofovir, and even pulsed-dye laser.

Dr. Mancini disclosed that he is a consultant to and a member of the scientific advisory board for Verrica Pharmaceuticals.

In the clinical experience of Anthony J. Mancini, MD, one option for children and adolescents who present with common warts is to do nothing, since they may resolve on their own.

“Many effective treatments that we have are painful and poorly tolerated, especially in younger children,” Dr. Mancini, professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago, said during the virtual Pediatric Dermatology 2020: Best Practices and Innovations Conference. “However, while they’re harmless and often self-limited, warts often form a social stigma, and parents often desire therapy.”

Even though warts may spontaneously resolve in up to 65% of patients at 2 years and 80% at 4 years, the goals of treatment are to eradicate them, minimize pain, avoid scarring, and help prevent recurrence.

One effective topical therapy he highlighted is WartPEEL cream, which is a proprietary, compounded formulation of 17% salicylic acid and 2% 5-fluorouracil. “It’s in a sustained release vehicle called Remedium, and is available from a compounding pharmacy, but not FDA approved,” said Dr. Mancini, who is also head of pediatric dermatology at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. “It’s applied nightly with plastic tape occlusion and rinsed off each morning.”

WartPEEL is available through NuCara Pharmacy at 877-268-2272. It is not covered by most insurance plans and it costs around $80. “It is very effective, tends to be totally painless, and has a much quicker response than over-the-counter salicylic acid-based treatments for warts,” he said.

Another treatment option is oral cimetidine, especially in patients who have multiple or recalcitrant warts. The recommended dosing is 30-40 mg/kg per day, divided into twice-daily dosing. “You have to give it for at least 8-12 weeks to determine whether it’s working or not,” Dr. Mancini said. “In the initial report, [investigators] described an 81% complete response rate, but subsequent randomized, controlled trials were not able to confirm that data against placebo or topical treatments. I will say, though, that cimetidine is well tolerated. It’s always worth a try but, if you do use it, always consider other medications the patient may be taking and potential drug-drug interactions.”

For flat warts, verrucous papules that commonly occur on the face, Dr. Mancini recommends off-label treatment with 5% 5-fluorouracil cream (Efudex), which is normally indicated for actinic keratoses in adults. “I have patients apply this for 3 nights per week and work their way up gradually to nightly application,” he said. “It’s really important that parents and patients understand the importance of sun protection when they’re using Efudex, and they need to know that some irritation is possible. Overall, this treatment seems to be very well tolerated.”

Other treatment options for common warts, in addition to over-the-counter products that contain salicylic acid, are home cryotherapy kits that contain a mixture of diethyl ether and propane. “These can be effective for small warts,” Dr. Mancini said. “But for larger, thicker lesions, they’re not going to quite as effective.”

Treatment options best reserved for dermatologists, he continued, include in-office liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, “if it’s tolerated,” he said. “I have a no-hold policy, so if we have to hold a child down who’s flailing and crying and screaming during treatment, we’re probably not going to use liquid nitrogen.” He also mentioned topical immunotherapy with agents like squaric acid dibutylester. “This is almost like putting poison ivy on your warts to get the immune system revved up,” he said. “It can be very effective.” Other treatment options include intralesional immune therapy, topical cidofovir, and even pulsed-dye laser.

Dr. Mancini disclosed that he is a consultant to and a member of the scientific advisory board for Verrica Pharmaceuticals.

FROM PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY 2020

Daily Recap: Lifestyle vs. genes in breast cancer showdown; Big pharma sues over insulin affordability law

Here are the stories our MDedge editors across specialties think you need to know about today:

Lifestyle choices may reduce breast cancer risk regardless of genetics

A “favorable” lifestyle was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer even among women at high genetic risk for the disease in a study of more than 90,000 women, researchers reported.

The findings suggest that, regardless of genetic risk, women may be able to reduce their risk of developing breast cancer by getting adequate levels of exercise; maintaining a healthy weight; and limiting or eliminating use of alcohol, oral contraceptives, and hormone replacement therapy.

“These data should empower patients that they can impact on their overall health and reduce the risk of developing breast cancer,” said William Gradishar, MD, who was not invovled with the study. Read more.

Primary care practices may lose $68K per physician this year