User login

The Mississippi solution

I agree wholeheartedly with Dr. William G. Wilkoff’s doubts that an increase in medical schools/students and/or foreign medical graduates is the answer to the physician shortage felt by many areas of the country (Letters From Maine, “Help Wanted,” Nov. 2019, page 19). All you have to do is look at the glut of physicians – and just about any other profession – in metropolitan areas versus rural America, and ask basic questions regarding why those doctors practice where they do. You will quickly discover that most are willing to trade the possibility of a higher salary in areas where their presence is more needed to achieve more school choices, jobs for a spouse, and likely a more favorable call schedule. Something more attractive than salary or the prospect of more “elbow room” is desired.

Here in Mississippi we may have found an answer to the problem. A few years ago our state legislature started the Mississippi Rural Health Scholarship Program that pays for recipients to attend a state-run medical school on scholarship in exchange for agreeing to practice at least 4 years in a rural area of the state (less than 20k population) following their primary care residency (family medicine, pediatrics, ob.gyn., med-peds, internal medicine, and, recently added, psychiatry). Although a recent increase in the number of pediatric residency slots at our state’s sole program will no doubt also have a positive effect to this end, such a scholarship program as the one implemented by Mississippi is the best way to compete with the various intangibles that lead people to choose bigger cities over rural areas of the state to practice their trade. Once there, many – like myself – will find that such a practice is not only a good business decision but often is a wonderful place to raise a family. Meanwhile, our own practice just added a fourth physician as a result of said Rural Health Scholarship Program, and we could not be more satisfied with the result.

I agree wholeheartedly with Dr. William G. Wilkoff’s doubts that an increase in medical schools/students and/or foreign medical graduates is the answer to the physician shortage felt by many areas of the country (Letters From Maine, “Help Wanted,” Nov. 2019, page 19). All you have to do is look at the glut of physicians – and just about any other profession – in metropolitan areas versus rural America, and ask basic questions regarding why those doctors practice where they do. You will quickly discover that most are willing to trade the possibility of a higher salary in areas where their presence is more needed to achieve more school choices, jobs for a spouse, and likely a more favorable call schedule. Something more attractive than salary or the prospect of more “elbow room” is desired.

Here in Mississippi we may have found an answer to the problem. A few years ago our state legislature started the Mississippi Rural Health Scholarship Program that pays for recipients to attend a state-run medical school on scholarship in exchange for agreeing to practice at least 4 years in a rural area of the state (less than 20k population) following their primary care residency (family medicine, pediatrics, ob.gyn., med-peds, internal medicine, and, recently added, psychiatry). Although a recent increase in the number of pediatric residency slots at our state’s sole program will no doubt also have a positive effect to this end, such a scholarship program as the one implemented by Mississippi is the best way to compete with the various intangibles that lead people to choose bigger cities over rural areas of the state to practice their trade. Once there, many – like myself – will find that such a practice is not only a good business decision but often is a wonderful place to raise a family. Meanwhile, our own practice just added a fourth physician as a result of said Rural Health Scholarship Program, and we could not be more satisfied with the result.

I agree wholeheartedly with Dr. William G. Wilkoff’s doubts that an increase in medical schools/students and/or foreign medical graduates is the answer to the physician shortage felt by many areas of the country (Letters From Maine, “Help Wanted,” Nov. 2019, page 19). All you have to do is look at the glut of physicians – and just about any other profession – in metropolitan areas versus rural America, and ask basic questions regarding why those doctors practice where they do. You will quickly discover that most are willing to trade the possibility of a higher salary in areas where their presence is more needed to achieve more school choices, jobs for a spouse, and likely a more favorable call schedule. Something more attractive than salary or the prospect of more “elbow room” is desired.

Here in Mississippi we may have found an answer to the problem. A few years ago our state legislature started the Mississippi Rural Health Scholarship Program that pays for recipients to attend a state-run medical school on scholarship in exchange for agreeing to practice at least 4 years in a rural area of the state (less than 20k population) following their primary care residency (family medicine, pediatrics, ob.gyn., med-peds, internal medicine, and, recently added, psychiatry). Although a recent increase in the number of pediatric residency slots at our state’s sole program will no doubt also have a positive effect to this end, such a scholarship program as the one implemented by Mississippi is the best way to compete with the various intangibles that lead people to choose bigger cities over rural areas of the state to practice their trade. Once there, many – like myself – will find that such a practice is not only a good business decision but often is a wonderful place to raise a family. Meanwhile, our own practice just added a fourth physician as a result of said Rural Health Scholarship Program, and we could not be more satisfied with the result.

Vaccinating most girls could eliminate cervical cancer within a century

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in lower- and middle-income countries, but universal human papillomavirus vaccination for girls would reduce new cervical cancer cases by about 90% over the next century, according to researchers.

Adding twice-lifetime cervical screening with human papillomavirus (HPV) testing would further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, including in countries with the highest burden, the researchers reported in The Lancet.

Marc Brisson, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and colleagues conducted this study using three models identified by the World Health Organization. The models were used to project reductions in cervical cancer incidence for women in 78 low- and middle-income countries based on the following HPV vaccination and screening scenarios:

- Universal girls-only vaccination at age 9 years, assuming 90% of girls vaccinated and a vaccine that is perfectly effective

- Girls-only vaccination plus cervical screening with HPV testing at age 35 years

- Girls-only vaccination plus screening at ages 35 and 45.

All three scenarios modeled would result in the elimination of cervical cancer, Dr. Brisson and colleagues found. Elimination was defined as four or fewer new cases per 100,000 women-years.

The simplest scenario, universal girls-only vaccination, was predicted to reduce age-standardized cervical cancer incidence from 19.8 cases per 100,000 women-years to 2.1 cases per 100,000 women-years (89.4% reduction) by 2120. That amounts to about 61 million potential cases avoided, with elimination targets reached in 60% of the countries studied.

HPV vaccination plus one-time screening was predicted to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer to 1.0 case per 100,000 women-years (95.0% reduction), and HPV vaccination plus twice-lifetime screening was predicted to reduce the incidence to 0.7 cases per 100,000 women-years (96.7% reduction).

Dr. Brisson and colleagues reported that, for the countries with the highest burden of cervical cancer (more than 25 cases per 100,000 women-years), adding screening would be necessary to achieve elimination.

To meet the same targets across all 78 countries, “our models predict that scale-up of both girls-only HPV vaccination and twice-lifetime screening is necessary, with 90% HPV vaccination coverage, 90% screening uptake, and long-term protection against HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Brisson and colleagues claimed that a strength of this study is the modeling approach, which compared three models “that have been extensively peer reviewed and validated with postvaccination surveillance data.”

The researchers acknowledged, however, that their modeling could not account for variations in sexual behavior from country to country, and the study was not designed to anticipate behavioral or technological changes that could affect cervical cancer incidence in the decades to come.

The study was funded by the WHO, the United Nations, and the Canadian and Australian governments. The WHO contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Two study authors reported receiving indirect industry funding for a cervical screening trial in Australia.

SOURCE: Brisson M et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30068-4.

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in lower- and middle-income countries, but universal human papillomavirus vaccination for girls would reduce new cervical cancer cases by about 90% over the next century, according to researchers.

Adding twice-lifetime cervical screening with human papillomavirus (HPV) testing would further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, including in countries with the highest burden, the researchers reported in The Lancet.

Marc Brisson, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and colleagues conducted this study using three models identified by the World Health Organization. The models were used to project reductions in cervical cancer incidence for women in 78 low- and middle-income countries based on the following HPV vaccination and screening scenarios:

- Universal girls-only vaccination at age 9 years, assuming 90% of girls vaccinated and a vaccine that is perfectly effective

- Girls-only vaccination plus cervical screening with HPV testing at age 35 years

- Girls-only vaccination plus screening at ages 35 and 45.

All three scenarios modeled would result in the elimination of cervical cancer, Dr. Brisson and colleagues found. Elimination was defined as four or fewer new cases per 100,000 women-years.

The simplest scenario, universal girls-only vaccination, was predicted to reduce age-standardized cervical cancer incidence from 19.8 cases per 100,000 women-years to 2.1 cases per 100,000 women-years (89.4% reduction) by 2120. That amounts to about 61 million potential cases avoided, with elimination targets reached in 60% of the countries studied.

HPV vaccination plus one-time screening was predicted to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer to 1.0 case per 100,000 women-years (95.0% reduction), and HPV vaccination plus twice-lifetime screening was predicted to reduce the incidence to 0.7 cases per 100,000 women-years (96.7% reduction).

Dr. Brisson and colleagues reported that, for the countries with the highest burden of cervical cancer (more than 25 cases per 100,000 women-years), adding screening would be necessary to achieve elimination.

To meet the same targets across all 78 countries, “our models predict that scale-up of both girls-only HPV vaccination and twice-lifetime screening is necessary, with 90% HPV vaccination coverage, 90% screening uptake, and long-term protection against HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Brisson and colleagues claimed that a strength of this study is the modeling approach, which compared three models “that have been extensively peer reviewed and validated with postvaccination surveillance data.”

The researchers acknowledged, however, that their modeling could not account for variations in sexual behavior from country to country, and the study was not designed to anticipate behavioral or technological changes that could affect cervical cancer incidence in the decades to come.

The study was funded by the WHO, the United Nations, and the Canadian and Australian governments. The WHO contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Two study authors reported receiving indirect industry funding for a cervical screening trial in Australia.

SOURCE: Brisson M et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30068-4.

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in lower- and middle-income countries, but universal human papillomavirus vaccination for girls would reduce new cervical cancer cases by about 90% over the next century, according to researchers.

Adding twice-lifetime cervical screening with human papillomavirus (HPV) testing would further reduce the incidence of cervical cancer, including in countries with the highest burden, the researchers reported in The Lancet.

Marc Brisson, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and colleagues conducted this study using three models identified by the World Health Organization. The models were used to project reductions in cervical cancer incidence for women in 78 low- and middle-income countries based on the following HPV vaccination and screening scenarios:

- Universal girls-only vaccination at age 9 years, assuming 90% of girls vaccinated and a vaccine that is perfectly effective

- Girls-only vaccination plus cervical screening with HPV testing at age 35 years

- Girls-only vaccination plus screening at ages 35 and 45.

All three scenarios modeled would result in the elimination of cervical cancer, Dr. Brisson and colleagues found. Elimination was defined as four or fewer new cases per 100,000 women-years.

The simplest scenario, universal girls-only vaccination, was predicted to reduce age-standardized cervical cancer incidence from 19.8 cases per 100,000 women-years to 2.1 cases per 100,000 women-years (89.4% reduction) by 2120. That amounts to about 61 million potential cases avoided, with elimination targets reached in 60% of the countries studied.

HPV vaccination plus one-time screening was predicted to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer to 1.0 case per 100,000 women-years (95.0% reduction), and HPV vaccination plus twice-lifetime screening was predicted to reduce the incidence to 0.7 cases per 100,000 women-years (96.7% reduction).

Dr. Brisson and colleagues reported that, for the countries with the highest burden of cervical cancer (more than 25 cases per 100,000 women-years), adding screening would be necessary to achieve elimination.

To meet the same targets across all 78 countries, “our models predict that scale-up of both girls-only HPV vaccination and twice-lifetime screening is necessary, with 90% HPV vaccination coverage, 90% screening uptake, and long-term protection against HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58,” the researchers wrote.

Dr. Brisson and colleagues claimed that a strength of this study is the modeling approach, which compared three models “that have been extensively peer reviewed and validated with postvaccination surveillance data.”

The researchers acknowledged, however, that their modeling could not account for variations in sexual behavior from country to country, and the study was not designed to anticipate behavioral or technological changes that could affect cervical cancer incidence in the decades to come.

The study was funded by the WHO, the United Nations, and the Canadian and Australian governments. The WHO contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. Two study authors reported receiving indirect industry funding for a cervical screening trial in Australia.

SOURCE: Brisson M et al. Lancet. 2020 Jan 30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30068-4.

FROM THE LANCET

What to do when stimulants fail for ADHD

NEW ORLEANS – A variety of reasons can contribute to the failure of stimulants to treat ADHD in children, such as comorbidities, missed diagnoses, inadequate medication dosage, side effects, major life changes, and other factors in the home or school environments, said Alison Schonwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Stimulant medications indicated for ADHD usually work in 70%-75% of school-age children, but that leaves one in four children whose condition can be more challenging to treat, she said.

“Look around you,” Dr. Schonwald told a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “You’re not the only one struggling with this topic.” She sprinkled her presentation with case studies of patients with ADHD for whom stimulants weren’t working, examples that the audience clearly found familiar.

The three steps you already know to do with treatment-resistant children sound simple: assess the child for factors linked to their poor response; develop a new treatment plan; and use Food and Drug Administration-approved nonstimulant medications, including off-label options, in a new plan.

But in the office, the process can be anything but simple when you must consider school and family environments, comorbidities, and other factors potentially complicating the child’s ability to function well.

Comorbidities

To start, Dr. Schonwald provided a chart of common coexisting problems in children with ADHD that included the recommended assessment and intervention:

- Mood and self-esteem issues call for the depression section of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ9) and Moods and Feelings questionnaire (MFQ), followed by interventions such as individual and peer group therapy and exercise.

- Anxiety can be assessed with the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale, then treated similarly to mood and self-esteem issues.

- Bullying or trauma require taking a history during an interview, and treatment with individual and peer group therapy.

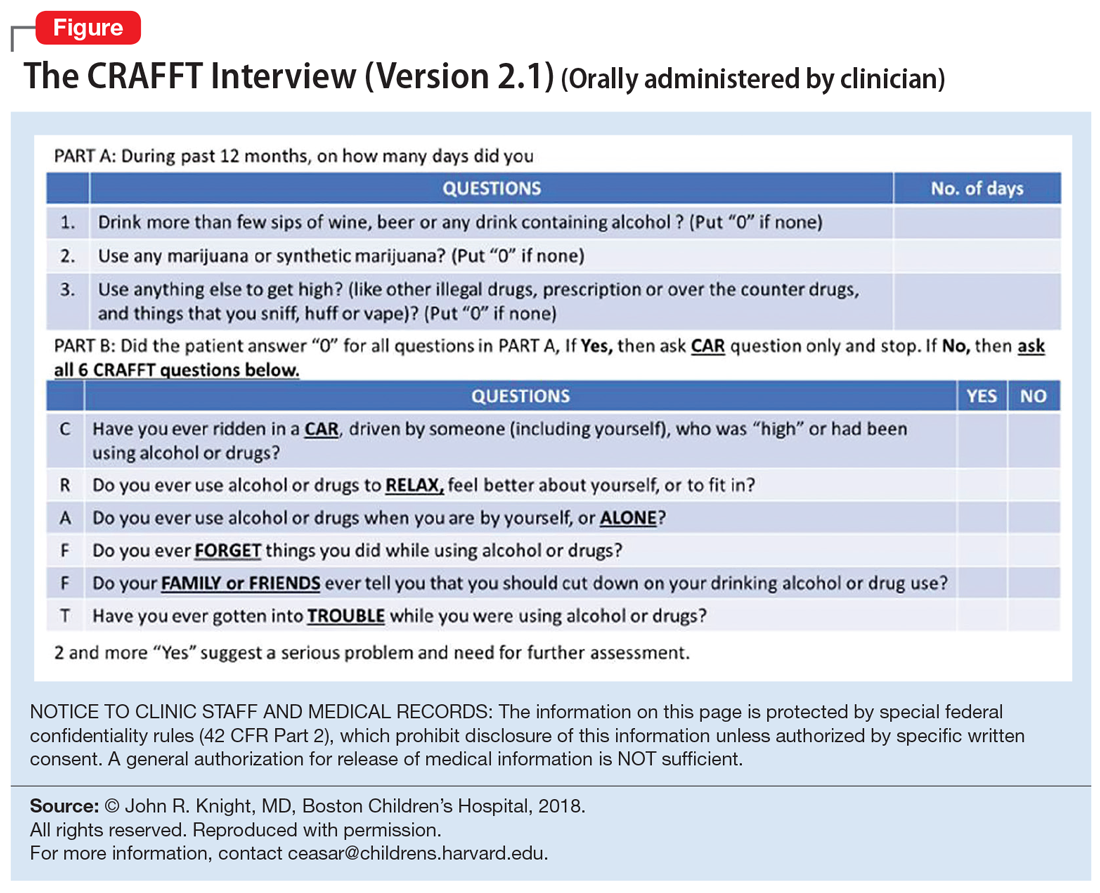

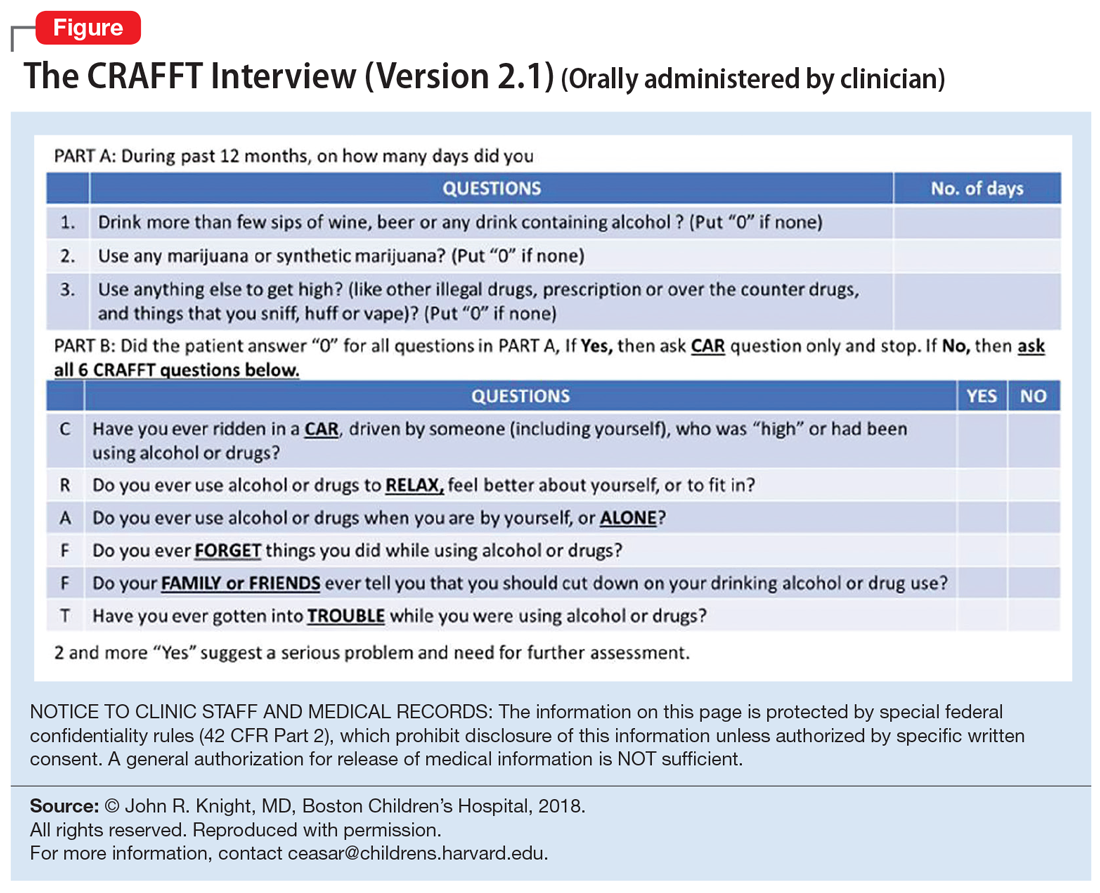

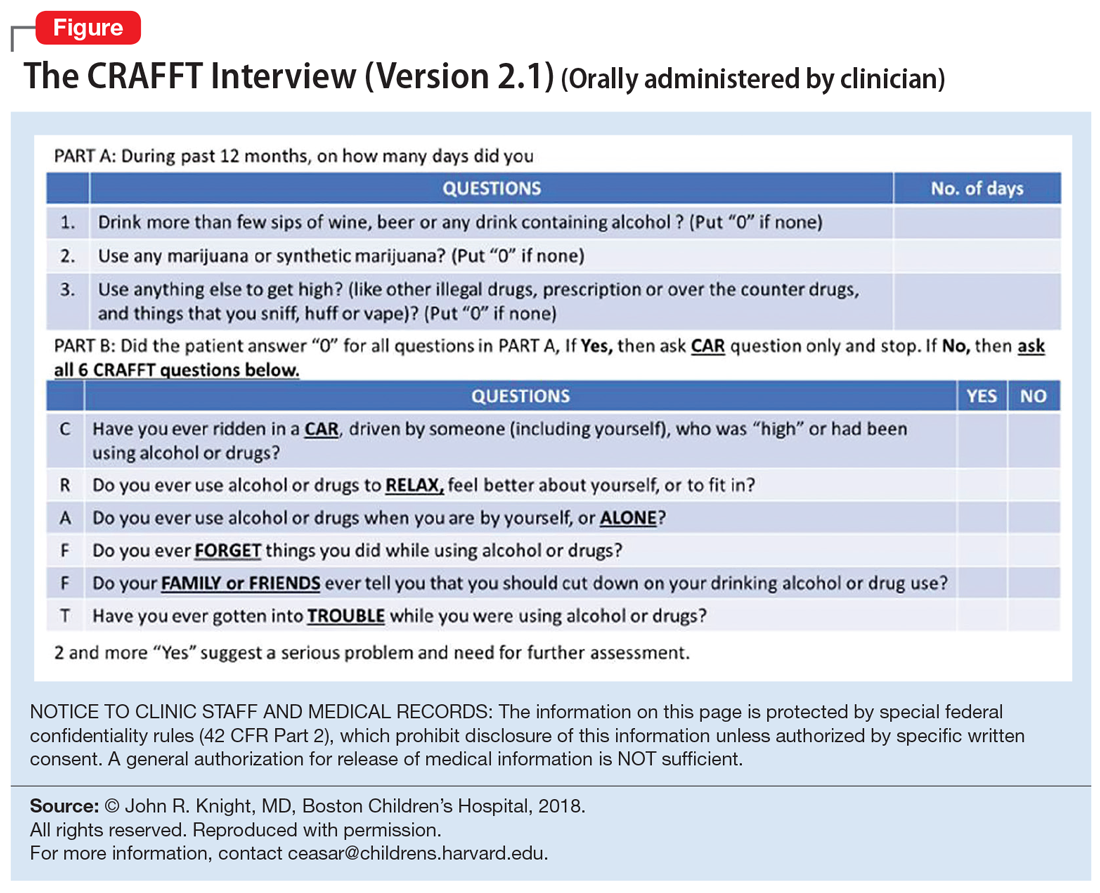

- Substance abuse should be assessed with the CRAFFT screening tool (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble) and Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) Tool, then treated according to best practices.

- Executive function, low cognitive abilities, and poor adaptive skills require a review of the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) testing, followed by personalized school and home interventions.

- Poor social skills, assessed in an interview, also require personalized interventions at home and in school.

Doctors also may need to consider other common comorbidities in children with ADHD, such as bipolar disorder, depression, learning disabilities, oppositional defiant disorder, and tic disorders.

Tic disorders typically have an onset around 7 years old and peak in midadolescence, declining in late teen years. An estimated 35%-90% of children with Tourette syndrome have ADHD, Dr. Schonwald said (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006 Jul;48[7]:616-21).

Managing treatment with stimulants

A common dosage amount for stimulants is 2.5-5 mg, but that dose may be too low for children, Dr. Schonwald said. She recommended increasing it until an effect is seen and stopping at the effective dose level the child can tolerate. The maximum recommended by the FDA is 60 mg/day for short-acting stimulants and 72 mg/day for extended-release ones, but some research has shown dosage can go even higher without causing toxic effects (J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010 Feb;20[1]:49-54).

Dr. Schonwald also suggested trying both methylphenidate and amphetamine medication, while recognizing the latter tends to have more stimulant-related side effects.

Adherence is another consideration because multiple studies show high rates of noncompliance or discontinuation, such as up to 19% discontinuation for long-acting and 38% for short-acting stimulants (J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Nov;76(11):e1459-68; Postgrad Med. 2012 May;124(3):139-48). A study of a school cohort in Philadelphia found only about one in five children were adherent (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 May;50[5]:480-9).

One potential solution to adherence challenges are pill reminder smartphone apps, such as Medisafe Medication Management, Pill Reminder-All in One, MyTherapy: Medication Reminder, and CareZone.

Dr. Schonwald noted several factors that can influence children’s response to stimulants. Among children with comorbid intellectual disability, for example, the response rate is lower than the average 75% of children without the disability, hovering around 40%-50% (Res Dev Disabil. 2018 Dec;83:217-32). Those who get more sleep tend to have improved attention, compared with children with less sleep (Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017 Mar;9[1]:31-38).

She also offered strategies to manage problematic adverse effects from stimulants. Those experiencing weight loss can take their stimulant after breakfast, drink whole milk, and consider taking drug holidays.

To reduce stomachaches, children should take their medication with food, and you should look at whether the child is taking the lowest effective dose they can and whether anxiety may be involved. Similarly, children with headaches should take stimulants with food, and you should look at the dosage and ask whether the patient is getting adequate sleep.

Strategies to address difficulty falling asleep can include taking the stimulant earlier in the day or switching to a shorter-acting form, dexmethylphenidate, or another stimulant. If they’re having trouble staying asleep, inquire about sleep hygiene, and look for associations with other factors that might explain why the child is experiencing new problems with staying asleep. If these strategies are unsuccessful, you can consider prescribing melatonin or clonidine.

Alternatives to stimulants

Several medications besides stimulants are available to prescribe to children with ADHD if they aren’t responding adequately to stimulants, Dr. Schonwald said.

Atomoxetine performed better than placebo in treatment studies, with similar weight loss effects, albeit the lowest mean effect size in clinician ratings (Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5[9]:727-38). Dr. Schonwald recommended starting atomoxetine in children under 40 kg at 0.5 mg/kg for 4 days, then increasing to 1.2 mg/kg/day. For children over 40 kg, the dose can start at 40 mg. Maximum dose can range from 1.4 to 1.8 mg/kg or 100 mg/day.

About 7% of white children and 2% of African American children are poor metabolizers of atomoxetine, and the drug has interactions with dextromethorphan, fluoxetine, and paroxetine, she noted. Side effects can include abdominal pain, dry mouth, fatigue, mood swings, nausea, and vomiting.

Two alpha-adrenergics that you can consider are clonidine and guanfacine. Clonidine, a hypotensive drug given at a dose of 0.05-0.2 mg up to three times a day, is helpful for hyperactivity and impulsivity rather than attention difficulties. Side effects can include depression, headache, rebound hypertension, and sedation, and it’s only FDA approved for ages 12 years and older.

An extended release version of clonidine (Kapvay) is approved for monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for ADHD; it led to improvements in ADHD–Rating Scale-IV scores as soon as the second week in an 8-week randomized controlled trial. Mild to moderate somnolence was the most common adverse event, and changes on electrocardiograms were minor (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;50[2]:171-9).

Guanfacine, also a hypotensive drug, given at a dose of 0.5-2 mg up to three times a day, has fewer data about its use for ADHD but appears to treat attention problems more effectively than hyperactivity. Also approved only for ages 12 years and older, guanfacine is less sedating, and its side effects can include agitation, headache , and insomnia. An extended-release version of guanfacine (brand name Intuniv) showed statistically significant reductions in ADHD Rating Scale-IV scores in a 9-week, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Side effects including fatigue, sedation, and somnolence occurred in the first 2 weeks but generally resolved, and participants returned to baseline during dose maintenance and tapering (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;48[2]:155-65).

Intuniv doses should start at 1 mg/day and increase no more than 1 mg/week, Dr. Schonwald said, until reaching a maintenance dose of 1-4 mg once daily, depending on the patient’s clinical response and tolerability. Children also must be able to swallow the pill whole.

Treating preschoolers

Preschool children are particularly difficult to diagnose given their normal range of temperament and development, Dr. Schonwald said. Their symptoms could be resulting from another diagnosis or from circumstances in the environment.

You should consider potential comorbidities and whether the child’s symptoms are situational or pervasive. About 55% of preschoolers have at least one comorbidity, she said (Infants & Young Children. 2006 Apr-Jun;19[2]:109-122.)

That said, stimulants usually are effective in very young children whose primary concern is ADHD. In a randomized controlled trial of 303 preschoolers, significantly more children experienced reduced ADHD symptoms with methylphenidate than with placebo. The trial’s “data suggest that preschoolers with ADHD need to start with low methylphenidate doses. Treatment may best begin using methylphenidate–immediate release at 2.5 mg twice daily, and then be increased to 7.5 mg three times a day during the course of 1 week. The mean optimal total daily [methylphenidate] dose for preschoolers was 14.2 plus or minus 8.1 mg/day” (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;45[11]:1284-93).

In treating preschoolers, if the patient’s symptoms appear to get worse after starting a stimulant, you can consider a medication change. If symptoms are much worse, consider a lower dose or a different stimulant class, or whether the diagnosis is appropriate.

Five common components of poor behavior in preschoolers with ADHD include agitation, anxiety, explosively, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. If these issues are occurring throughout the day, consider reducing the dose or switching drug classes.

If it’s only occurring in the morning, Dr. Schonwald said, optimize the morning structure and consider giving the medication earlier in the morning or adding a short-acting booster. If it’s occurring in late afternoon, consider a booster and reducing high-demand activities for the child.

If a preschooler experiences some benefit from the stimulant but still has problems, adjunctive atomoxetine or an alpha adrenergic may help. Those medications also are recommended if the child has no benefit with the stimulant or cannot tolerate the lowest therapeutic dose.

Dr. Schonwald said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – A variety of reasons can contribute to the failure of stimulants to treat ADHD in children, such as comorbidities, missed diagnoses, inadequate medication dosage, side effects, major life changes, and other factors in the home or school environments, said Alison Schonwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Stimulant medications indicated for ADHD usually work in 70%-75% of school-age children, but that leaves one in four children whose condition can be more challenging to treat, she said.

“Look around you,” Dr. Schonwald told a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “You’re not the only one struggling with this topic.” She sprinkled her presentation with case studies of patients with ADHD for whom stimulants weren’t working, examples that the audience clearly found familiar.

The three steps you already know to do with treatment-resistant children sound simple: assess the child for factors linked to their poor response; develop a new treatment plan; and use Food and Drug Administration-approved nonstimulant medications, including off-label options, in a new plan.

But in the office, the process can be anything but simple when you must consider school and family environments, comorbidities, and other factors potentially complicating the child’s ability to function well.

Comorbidities

To start, Dr. Schonwald provided a chart of common coexisting problems in children with ADHD that included the recommended assessment and intervention:

- Mood and self-esteem issues call for the depression section of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ9) and Moods and Feelings questionnaire (MFQ), followed by interventions such as individual and peer group therapy and exercise.

- Anxiety can be assessed with the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale, then treated similarly to mood and self-esteem issues.

- Bullying or trauma require taking a history during an interview, and treatment with individual and peer group therapy.

- Substance abuse should be assessed with the CRAFFT screening tool (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble) and Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) Tool, then treated according to best practices.

- Executive function, low cognitive abilities, and poor adaptive skills require a review of the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) testing, followed by personalized school and home interventions.

- Poor social skills, assessed in an interview, also require personalized interventions at home and in school.

Doctors also may need to consider other common comorbidities in children with ADHD, such as bipolar disorder, depression, learning disabilities, oppositional defiant disorder, and tic disorders.

Tic disorders typically have an onset around 7 years old and peak in midadolescence, declining in late teen years. An estimated 35%-90% of children with Tourette syndrome have ADHD, Dr. Schonwald said (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006 Jul;48[7]:616-21).

Managing treatment with stimulants

A common dosage amount for stimulants is 2.5-5 mg, but that dose may be too low for children, Dr. Schonwald said. She recommended increasing it until an effect is seen and stopping at the effective dose level the child can tolerate. The maximum recommended by the FDA is 60 mg/day for short-acting stimulants and 72 mg/day for extended-release ones, but some research has shown dosage can go even higher without causing toxic effects (J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010 Feb;20[1]:49-54).

Dr. Schonwald also suggested trying both methylphenidate and amphetamine medication, while recognizing the latter tends to have more stimulant-related side effects.

Adherence is another consideration because multiple studies show high rates of noncompliance or discontinuation, such as up to 19% discontinuation for long-acting and 38% for short-acting stimulants (J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Nov;76(11):e1459-68; Postgrad Med. 2012 May;124(3):139-48). A study of a school cohort in Philadelphia found only about one in five children were adherent (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 May;50[5]:480-9).

One potential solution to adherence challenges are pill reminder smartphone apps, such as Medisafe Medication Management, Pill Reminder-All in One, MyTherapy: Medication Reminder, and CareZone.

Dr. Schonwald noted several factors that can influence children’s response to stimulants. Among children with comorbid intellectual disability, for example, the response rate is lower than the average 75% of children without the disability, hovering around 40%-50% (Res Dev Disabil. 2018 Dec;83:217-32). Those who get more sleep tend to have improved attention, compared with children with less sleep (Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017 Mar;9[1]:31-38).

She also offered strategies to manage problematic adverse effects from stimulants. Those experiencing weight loss can take their stimulant after breakfast, drink whole milk, and consider taking drug holidays.

To reduce stomachaches, children should take their medication with food, and you should look at whether the child is taking the lowest effective dose they can and whether anxiety may be involved. Similarly, children with headaches should take stimulants with food, and you should look at the dosage and ask whether the patient is getting adequate sleep.

Strategies to address difficulty falling asleep can include taking the stimulant earlier in the day or switching to a shorter-acting form, dexmethylphenidate, or another stimulant. If they’re having trouble staying asleep, inquire about sleep hygiene, and look for associations with other factors that might explain why the child is experiencing new problems with staying asleep. If these strategies are unsuccessful, you can consider prescribing melatonin or clonidine.

Alternatives to stimulants

Several medications besides stimulants are available to prescribe to children with ADHD if they aren’t responding adequately to stimulants, Dr. Schonwald said.

Atomoxetine performed better than placebo in treatment studies, with similar weight loss effects, albeit the lowest mean effect size in clinician ratings (Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5[9]:727-38). Dr. Schonwald recommended starting atomoxetine in children under 40 kg at 0.5 mg/kg for 4 days, then increasing to 1.2 mg/kg/day. For children over 40 kg, the dose can start at 40 mg. Maximum dose can range from 1.4 to 1.8 mg/kg or 100 mg/day.

About 7% of white children and 2% of African American children are poor metabolizers of atomoxetine, and the drug has interactions with dextromethorphan, fluoxetine, and paroxetine, she noted. Side effects can include abdominal pain, dry mouth, fatigue, mood swings, nausea, and vomiting.

Two alpha-adrenergics that you can consider are clonidine and guanfacine. Clonidine, a hypotensive drug given at a dose of 0.05-0.2 mg up to three times a day, is helpful for hyperactivity and impulsivity rather than attention difficulties. Side effects can include depression, headache, rebound hypertension, and sedation, and it’s only FDA approved for ages 12 years and older.

An extended release version of clonidine (Kapvay) is approved for monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for ADHD; it led to improvements in ADHD–Rating Scale-IV scores as soon as the second week in an 8-week randomized controlled trial. Mild to moderate somnolence was the most common adverse event, and changes on electrocardiograms were minor (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;50[2]:171-9).

Guanfacine, also a hypotensive drug, given at a dose of 0.5-2 mg up to three times a day, has fewer data about its use for ADHD but appears to treat attention problems more effectively than hyperactivity. Also approved only for ages 12 years and older, guanfacine is less sedating, and its side effects can include agitation, headache , and insomnia. An extended-release version of guanfacine (brand name Intuniv) showed statistically significant reductions in ADHD Rating Scale-IV scores in a 9-week, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Side effects including fatigue, sedation, and somnolence occurred in the first 2 weeks but generally resolved, and participants returned to baseline during dose maintenance and tapering (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;48[2]:155-65).

Intuniv doses should start at 1 mg/day and increase no more than 1 mg/week, Dr. Schonwald said, until reaching a maintenance dose of 1-4 mg once daily, depending on the patient’s clinical response and tolerability. Children also must be able to swallow the pill whole.

Treating preschoolers

Preschool children are particularly difficult to diagnose given their normal range of temperament and development, Dr. Schonwald said. Their symptoms could be resulting from another diagnosis or from circumstances in the environment.

You should consider potential comorbidities and whether the child’s symptoms are situational or pervasive. About 55% of preschoolers have at least one comorbidity, she said (Infants & Young Children. 2006 Apr-Jun;19[2]:109-122.)

That said, stimulants usually are effective in very young children whose primary concern is ADHD. In a randomized controlled trial of 303 preschoolers, significantly more children experienced reduced ADHD symptoms with methylphenidate than with placebo. The trial’s “data suggest that preschoolers with ADHD need to start with low methylphenidate doses. Treatment may best begin using methylphenidate–immediate release at 2.5 mg twice daily, and then be increased to 7.5 mg three times a day during the course of 1 week. The mean optimal total daily [methylphenidate] dose for preschoolers was 14.2 plus or minus 8.1 mg/day” (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;45[11]:1284-93).

In treating preschoolers, if the patient’s symptoms appear to get worse after starting a stimulant, you can consider a medication change. If symptoms are much worse, consider a lower dose or a different stimulant class, or whether the diagnosis is appropriate.

Five common components of poor behavior in preschoolers with ADHD include agitation, anxiety, explosively, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. If these issues are occurring throughout the day, consider reducing the dose or switching drug classes.

If it’s only occurring in the morning, Dr. Schonwald said, optimize the morning structure and consider giving the medication earlier in the morning or adding a short-acting booster. If it’s occurring in late afternoon, consider a booster and reducing high-demand activities for the child.

If a preschooler experiences some benefit from the stimulant but still has problems, adjunctive atomoxetine or an alpha adrenergic may help. Those medications also are recommended if the child has no benefit with the stimulant or cannot tolerate the lowest therapeutic dose.

Dr. Schonwald said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

NEW ORLEANS – A variety of reasons can contribute to the failure of stimulants to treat ADHD in children, such as comorbidities, missed diagnoses, inadequate medication dosage, side effects, major life changes, and other factors in the home or school environments, said Alison Schonwald, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Stimulant medications indicated for ADHD usually work in 70%-75% of school-age children, but that leaves one in four children whose condition can be more challenging to treat, she said.

“Look around you,” Dr. Schonwald told a packed room at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “You’re not the only one struggling with this topic.” She sprinkled her presentation with case studies of patients with ADHD for whom stimulants weren’t working, examples that the audience clearly found familiar.

The three steps you already know to do with treatment-resistant children sound simple: assess the child for factors linked to their poor response; develop a new treatment plan; and use Food and Drug Administration-approved nonstimulant medications, including off-label options, in a new plan.

But in the office, the process can be anything but simple when you must consider school and family environments, comorbidities, and other factors potentially complicating the child’s ability to function well.

Comorbidities

To start, Dr. Schonwald provided a chart of common coexisting problems in children with ADHD that included the recommended assessment and intervention:

- Mood and self-esteem issues call for the depression section of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ9) and Moods and Feelings questionnaire (MFQ), followed by interventions such as individual and peer group therapy and exercise.

- Anxiety can be assessed with the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) and Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale, then treated similarly to mood and self-esteem issues.

- Bullying or trauma require taking a history during an interview, and treatment with individual and peer group therapy.

- Substance abuse should be assessed with the CRAFFT screening tool (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble) and Screening to Brief Intervention (S2BI) Tool, then treated according to best practices.

- Executive function, low cognitive abilities, and poor adaptive skills require a review of the child’s Individualized Education Program (IEP) testing, followed by personalized school and home interventions.

- Poor social skills, assessed in an interview, also require personalized interventions at home and in school.

Doctors also may need to consider other common comorbidities in children with ADHD, such as bipolar disorder, depression, learning disabilities, oppositional defiant disorder, and tic disorders.

Tic disorders typically have an onset around 7 years old and peak in midadolescence, declining in late teen years. An estimated 35%-90% of children with Tourette syndrome have ADHD, Dr. Schonwald said (Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006 Jul;48[7]:616-21).

Managing treatment with stimulants

A common dosage amount for stimulants is 2.5-5 mg, but that dose may be too low for children, Dr. Schonwald said. She recommended increasing it until an effect is seen and stopping at the effective dose level the child can tolerate. The maximum recommended by the FDA is 60 mg/day for short-acting stimulants and 72 mg/day for extended-release ones, but some research has shown dosage can go even higher without causing toxic effects (J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010 Feb;20[1]:49-54).

Dr. Schonwald also suggested trying both methylphenidate and amphetamine medication, while recognizing the latter tends to have more stimulant-related side effects.

Adherence is another consideration because multiple studies show high rates of noncompliance or discontinuation, such as up to 19% discontinuation for long-acting and 38% for short-acting stimulants (J Clin Psychiatry. 2015 Nov;76(11):e1459-68; Postgrad Med. 2012 May;124(3):139-48). A study of a school cohort in Philadelphia found only about one in five children were adherent (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 May;50[5]:480-9).

One potential solution to adherence challenges are pill reminder smartphone apps, such as Medisafe Medication Management, Pill Reminder-All in One, MyTherapy: Medication Reminder, and CareZone.

Dr. Schonwald noted several factors that can influence children’s response to stimulants. Among children with comorbid intellectual disability, for example, the response rate is lower than the average 75% of children without the disability, hovering around 40%-50% (Res Dev Disabil. 2018 Dec;83:217-32). Those who get more sleep tend to have improved attention, compared with children with less sleep (Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017 Mar;9[1]:31-38).

She also offered strategies to manage problematic adverse effects from stimulants. Those experiencing weight loss can take their stimulant after breakfast, drink whole milk, and consider taking drug holidays.

To reduce stomachaches, children should take their medication with food, and you should look at whether the child is taking the lowest effective dose they can and whether anxiety may be involved. Similarly, children with headaches should take stimulants with food, and you should look at the dosage and ask whether the patient is getting adequate sleep.

Strategies to address difficulty falling asleep can include taking the stimulant earlier in the day or switching to a shorter-acting form, dexmethylphenidate, or another stimulant. If they’re having trouble staying asleep, inquire about sleep hygiene, and look for associations with other factors that might explain why the child is experiencing new problems with staying asleep. If these strategies are unsuccessful, you can consider prescribing melatonin or clonidine.

Alternatives to stimulants

Several medications besides stimulants are available to prescribe to children with ADHD if they aren’t responding adequately to stimulants, Dr. Schonwald said.

Atomoxetine performed better than placebo in treatment studies, with similar weight loss effects, albeit the lowest mean effect size in clinician ratings (Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Sep;5[9]:727-38). Dr. Schonwald recommended starting atomoxetine in children under 40 kg at 0.5 mg/kg for 4 days, then increasing to 1.2 mg/kg/day. For children over 40 kg, the dose can start at 40 mg. Maximum dose can range from 1.4 to 1.8 mg/kg or 100 mg/day.

About 7% of white children and 2% of African American children are poor metabolizers of atomoxetine, and the drug has interactions with dextromethorphan, fluoxetine, and paroxetine, she noted. Side effects can include abdominal pain, dry mouth, fatigue, mood swings, nausea, and vomiting.

Two alpha-adrenergics that you can consider are clonidine and guanfacine. Clonidine, a hypotensive drug given at a dose of 0.05-0.2 mg up to three times a day, is helpful for hyperactivity and impulsivity rather than attention difficulties. Side effects can include depression, headache, rebound hypertension, and sedation, and it’s only FDA approved for ages 12 years and older.

An extended release version of clonidine (Kapvay) is approved for monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for ADHD; it led to improvements in ADHD–Rating Scale-IV scores as soon as the second week in an 8-week randomized controlled trial. Mild to moderate somnolence was the most common adverse event, and changes on electrocardiograms were minor (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;50[2]:171-9).

Guanfacine, also a hypotensive drug, given at a dose of 0.5-2 mg up to three times a day, has fewer data about its use for ADHD but appears to treat attention problems more effectively than hyperactivity. Also approved only for ages 12 years and older, guanfacine is less sedating, and its side effects can include agitation, headache , and insomnia. An extended-release version of guanfacine (brand name Intuniv) showed statistically significant reductions in ADHD Rating Scale-IV scores in a 9-week, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Side effects including fatigue, sedation, and somnolence occurred in the first 2 weeks but generally resolved, and participants returned to baseline during dose maintenance and tapering (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Feb;48[2]:155-65).

Intuniv doses should start at 1 mg/day and increase no more than 1 mg/week, Dr. Schonwald said, until reaching a maintenance dose of 1-4 mg once daily, depending on the patient’s clinical response and tolerability. Children also must be able to swallow the pill whole.

Treating preschoolers

Preschool children are particularly difficult to diagnose given their normal range of temperament and development, Dr. Schonwald said. Their symptoms could be resulting from another diagnosis or from circumstances in the environment.

You should consider potential comorbidities and whether the child’s symptoms are situational or pervasive. About 55% of preschoolers have at least one comorbidity, she said (Infants & Young Children. 2006 Apr-Jun;19[2]:109-122.)

That said, stimulants usually are effective in very young children whose primary concern is ADHD. In a randomized controlled trial of 303 preschoolers, significantly more children experienced reduced ADHD symptoms with methylphenidate than with placebo. The trial’s “data suggest that preschoolers with ADHD need to start with low methylphenidate doses. Treatment may best begin using methylphenidate–immediate release at 2.5 mg twice daily, and then be increased to 7.5 mg three times a day during the course of 1 week. The mean optimal total daily [methylphenidate] dose for preschoolers was 14.2 plus or minus 8.1 mg/day” (J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;45[11]:1284-93).

In treating preschoolers, if the patient’s symptoms appear to get worse after starting a stimulant, you can consider a medication change. If symptoms are much worse, consider a lower dose or a different stimulant class, or whether the diagnosis is appropriate.

Five common components of poor behavior in preschoolers with ADHD include agitation, anxiety, explosively, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. If these issues are occurring throughout the day, consider reducing the dose or switching drug classes.

If it’s only occurring in the morning, Dr. Schonwald said, optimize the morning structure and consider giving the medication earlier in the morning or adding a short-acting booster. If it’s occurring in late afternoon, consider a booster and reducing high-demand activities for the child.

If a preschooler experiences some benefit from the stimulant but still has problems, adjunctive atomoxetine or an alpha adrenergic may help. Those medications also are recommended if the child has no benefit with the stimulant or cannot tolerate the lowest therapeutic dose.

Dr. Schonwald said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAP 2019

Delaying flu vaccine didn’t drop fever rate for childhood immunizations

according to a randomized trial.

An increased risk for febrile seizures had been seen when the three vaccines were administered together, wrote Emmanuel B. Walter, MD, MPH, and coauthors, so they constructed a trial that compared a simultaneous administration strategy that delayed inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) administration by about 2 weeks.

In all, 221 children aged 12-16 months were enrolled in the randomized study. A total of 110 children received quadrivalent IIV (IIV4), DTaP, and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) simultaneously and returned for a dental health education visit 2 weeks later. For 111 children, DTaP and PCV13 were administered at study visit 1, and IIV4 was given along with dental health education 2 weeks later. Most children in both groups also received at least one nonstudy vaccine at the first study visit. Eleven children in the simultaneous group and four in the sequential group didn’t complete the study.

There was no difference between study groups in the combined rates of fever on the first 2 days after study visits 1 and 2 taken together: 8% of children in the simultaneous group and 9% of those in the sequential group had fever of 38° C or higher (adjusted relative risk, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-2.10).

However, children in the simultaneous group were more likely to receive antipyretic medication in the first 2 days after visit 1 (37% versus 22%; P = .020), reported Dr. Walter, professor of pediatrics at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and coauthors. Because it’s rare for febrile seizures to occur after immunization, the authors didn’t make the occurrence of febrile seizure a primary or secondary endpoint of the study; no seizures occurred in study participants. They did hypothesize that the total proportion of children having fever would be higher in the simultaneous than in the sequential group – a hypothesis not supported by the study findings.

Children were excluded, or their study vaccinations were delayed, if they had received antipyretic medication within the 72 hours preceding the visit or at the study visit, or if they had a temperature of 38° C or more.

Parents monitored participants’ temperatures for 8 days after visits by using a study-provided temporal thermometer once daily at about the same time, and also by checking the temperature if their child felt feverish. Parents also recorded any antipyretic use, medical care, other symptoms, and febrile seizures.

The study was stopped earlier than anticipated because unexpectedly high levels of influenza activity made it unethical to delay influenza immunization, explained Dr. Walter and coauthors.

Participants were a median 15 months old; most were non-Hispanic white and had private insurance. Most participants didn’t attend day care.

“Nearly all fever episodes and days of fever on days 1-2 after the study visits occurred after visit 1,” reported Dr. Walter and coinvestigators. They saw no difference between groups in the proportion of children who had a fever of 38.6° C on days 1-2 after either study visit.

The mean peak temperature – about 38.5° C – on combined study visits 1 and 2 didn’t differ between groups. Similarly, for those participants who had a fever, the mean postvisit fever duration of 1.3 days was identical between groups.

Parents also were asked about their perceptions of the vaccination schedule their children received. Over half of parents overall (56%) reported that they disliked having to bring their child in for two separate clinic visits, with more parents in the sequential group than the simultaneous group reporting this (65% versus 48%).

Generalizability of the findings and comparison with previous studies are limited, noted Dr. Walter and coinvestigators, because the composition of influenza vaccine varies from year to year. No signal for seizures was seen in the Vaccine Safety Datalink after IIV during the 2017-2018 influenza season, wrote the investigators. The 2010-2011 influenza season’s IIV formulation was associated with increased febrile seizure risk, indicating that the IIV formulation for that year may have been more pyrogenic than the 2017-2018 formulation.

Also, children deemed at higher risk of febrile seizure were excluded from the study, so findings may have limited applicability to these children. The lack of parental blinding also may have influenced antipyretic administration or other symptom reporting, although objective temperature measurement should not have been affected by the lack of blinding, wrote Dr. Walker and collaborators.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One coauthor reported potential conflicts of interest from financial support received from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, Merck, Protein Science, Dynavax, and Medimmune. The remaining authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Walter EB et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20191909.

according to a randomized trial.

An increased risk for febrile seizures had been seen when the three vaccines were administered together, wrote Emmanuel B. Walter, MD, MPH, and coauthors, so they constructed a trial that compared a simultaneous administration strategy that delayed inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) administration by about 2 weeks.

In all, 221 children aged 12-16 months were enrolled in the randomized study. A total of 110 children received quadrivalent IIV (IIV4), DTaP, and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) simultaneously and returned for a dental health education visit 2 weeks later. For 111 children, DTaP and PCV13 were administered at study visit 1, and IIV4 was given along with dental health education 2 weeks later. Most children in both groups also received at least one nonstudy vaccine at the first study visit. Eleven children in the simultaneous group and four in the sequential group didn’t complete the study.

There was no difference between study groups in the combined rates of fever on the first 2 days after study visits 1 and 2 taken together: 8% of children in the simultaneous group and 9% of those in the sequential group had fever of 38° C or higher (adjusted relative risk, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-2.10).

However, children in the simultaneous group were more likely to receive antipyretic medication in the first 2 days after visit 1 (37% versus 22%; P = .020), reported Dr. Walter, professor of pediatrics at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and coauthors. Because it’s rare for febrile seizures to occur after immunization, the authors didn’t make the occurrence of febrile seizure a primary or secondary endpoint of the study; no seizures occurred in study participants. They did hypothesize that the total proportion of children having fever would be higher in the simultaneous than in the sequential group – a hypothesis not supported by the study findings.

Children were excluded, or their study vaccinations were delayed, if they had received antipyretic medication within the 72 hours preceding the visit or at the study visit, or if they had a temperature of 38° C or more.

Parents monitored participants’ temperatures for 8 days after visits by using a study-provided temporal thermometer once daily at about the same time, and also by checking the temperature if their child felt feverish. Parents also recorded any antipyretic use, medical care, other symptoms, and febrile seizures.

The study was stopped earlier than anticipated because unexpectedly high levels of influenza activity made it unethical to delay influenza immunization, explained Dr. Walter and coauthors.

Participants were a median 15 months old; most were non-Hispanic white and had private insurance. Most participants didn’t attend day care.

“Nearly all fever episodes and days of fever on days 1-2 after the study visits occurred after visit 1,” reported Dr. Walter and coinvestigators. They saw no difference between groups in the proportion of children who had a fever of 38.6° C on days 1-2 after either study visit.

The mean peak temperature – about 38.5° C – on combined study visits 1 and 2 didn’t differ between groups. Similarly, for those participants who had a fever, the mean postvisit fever duration of 1.3 days was identical between groups.

Parents also were asked about their perceptions of the vaccination schedule their children received. Over half of parents overall (56%) reported that they disliked having to bring their child in for two separate clinic visits, with more parents in the sequential group than the simultaneous group reporting this (65% versus 48%).

Generalizability of the findings and comparison with previous studies are limited, noted Dr. Walter and coinvestigators, because the composition of influenza vaccine varies from year to year. No signal for seizures was seen in the Vaccine Safety Datalink after IIV during the 2017-2018 influenza season, wrote the investigators. The 2010-2011 influenza season’s IIV formulation was associated with increased febrile seizure risk, indicating that the IIV formulation for that year may have been more pyrogenic than the 2017-2018 formulation.

Also, children deemed at higher risk of febrile seizure were excluded from the study, so findings may have limited applicability to these children. The lack of parental blinding also may have influenced antipyretic administration or other symptom reporting, although objective temperature measurement should not have been affected by the lack of blinding, wrote Dr. Walker and collaborators.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One coauthor reported potential conflicts of interest from financial support received from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, Merck, Protein Science, Dynavax, and Medimmune. The remaining authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Walter EB et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20191909.

according to a randomized trial.

An increased risk for febrile seizures had been seen when the three vaccines were administered together, wrote Emmanuel B. Walter, MD, MPH, and coauthors, so they constructed a trial that compared a simultaneous administration strategy that delayed inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) administration by about 2 weeks.

In all, 221 children aged 12-16 months were enrolled in the randomized study. A total of 110 children received quadrivalent IIV (IIV4), DTaP, and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) simultaneously and returned for a dental health education visit 2 weeks later. For 111 children, DTaP and PCV13 were administered at study visit 1, and IIV4 was given along with dental health education 2 weeks later. Most children in both groups also received at least one nonstudy vaccine at the first study visit. Eleven children in the simultaneous group and four in the sequential group didn’t complete the study.

There was no difference between study groups in the combined rates of fever on the first 2 days after study visits 1 and 2 taken together: 8% of children in the simultaneous group and 9% of those in the sequential group had fever of 38° C or higher (adjusted relative risk, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-2.10).

However, children in the simultaneous group were more likely to receive antipyretic medication in the first 2 days after visit 1 (37% versus 22%; P = .020), reported Dr. Walter, professor of pediatrics at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and coauthors. Because it’s rare for febrile seizures to occur after immunization, the authors didn’t make the occurrence of febrile seizure a primary or secondary endpoint of the study; no seizures occurred in study participants. They did hypothesize that the total proportion of children having fever would be higher in the simultaneous than in the sequential group – a hypothesis not supported by the study findings.

Children were excluded, or their study vaccinations were delayed, if they had received antipyretic medication within the 72 hours preceding the visit or at the study visit, or if they had a temperature of 38° C or more.

Parents monitored participants’ temperatures for 8 days after visits by using a study-provided temporal thermometer once daily at about the same time, and also by checking the temperature if their child felt feverish. Parents also recorded any antipyretic use, medical care, other symptoms, and febrile seizures.

The study was stopped earlier than anticipated because unexpectedly high levels of influenza activity made it unethical to delay influenza immunization, explained Dr. Walter and coauthors.

Participants were a median 15 months old; most were non-Hispanic white and had private insurance. Most participants didn’t attend day care.

“Nearly all fever episodes and days of fever on days 1-2 after the study visits occurred after visit 1,” reported Dr. Walter and coinvestigators. They saw no difference between groups in the proportion of children who had a fever of 38.6° C on days 1-2 after either study visit.

The mean peak temperature – about 38.5° C – on combined study visits 1 and 2 didn’t differ between groups. Similarly, for those participants who had a fever, the mean postvisit fever duration of 1.3 days was identical between groups.

Parents also were asked about their perceptions of the vaccination schedule their children received. Over half of parents overall (56%) reported that they disliked having to bring their child in for two separate clinic visits, with more parents in the sequential group than the simultaneous group reporting this (65% versus 48%).

Generalizability of the findings and comparison with previous studies are limited, noted Dr. Walter and coinvestigators, because the composition of influenza vaccine varies from year to year. No signal for seizures was seen in the Vaccine Safety Datalink after IIV during the 2017-2018 influenza season, wrote the investigators. The 2010-2011 influenza season’s IIV formulation was associated with increased febrile seizure risk, indicating that the IIV formulation for that year may have been more pyrogenic than the 2017-2018 formulation.

Also, children deemed at higher risk of febrile seizure were excluded from the study, so findings may have limited applicability to these children. The lack of parental blinding also may have influenced antipyretic administration or other symptom reporting, although objective temperature measurement should not have been affected by the lack of blinding, wrote Dr. Walker and collaborators.

The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One coauthor reported potential conflicts of interest from financial support received from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, Merck, Protein Science, Dynavax, and Medimmune. The remaining authors have no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Walter EB et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20191909.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Fevers were no less common when influenza vaccine was delayed for children receiving DTaP and pneumococcal vaccinations.

Major finding: There was no difference between study groups in the combined rates of fever on the first 2 days after study visits 1 and 2 taken together: 8% of children in the simultaneous group and 9% of those in the sequential group had fever of 38° C or higher (adjusted relative risk, 0.87).

Study details: Randomized, nonblinded trial of 221 children aged 12-16 months receiving scheduled vaccinations.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One coauthor reported financial support received from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, Pfizer, Merck, Protein Science, Dynavax, and Medimmune.

Source: Walter EB et al. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20191909.

Losartan showing promise in pediatric epidermolysis bullosa trial

LONDON – Treatment with the in an early clinical study.

In the ongoing phase 1/2 REFLECT (Recessive dystrophic EB: Mechanisms of fibrosis and its prevention with Losartan in vivo) trial, involving 29 children, no severe complications have been noted so far, according to one of the study investigators, Dimitra Kiritsi, MD, of the University of Freiburg, Germany. At the EB World Congress, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA), she presented interim data on 18 patients in the trial, emphasizing that the primary aim of the trial was to evaluate the safety of this treatment approach.

Over the 2 years the trial has been underway, 65 adverse events have been reported, of which 4 have been severe. Two of these were bacterial infections that required hospital treatment and the other two were a reduction in the general health condition of the child.

Losartan is an angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) that has been in clinical use for more than 25 years in adults and 15 years in children over the age of 6 years.

The drug may be used for treating recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB) in the future, Dr. Kiritsi said, because it attenuates tumor necrosis factor–beta (TGF-beta) signaling, which is thought to be involved in the fibrotic process. So while it may not target the genetic defect, it could help ameliorate the effects of the disease.

The precursor to REFLECT was a study performed in a mouse disease model of EB (EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1211-28) where a reduction in fibrotic scarring was seen with losartan with “remarkable effects” on “mitten” deformity, Dr. Kiritsi said. The results of that study suggested that the earlier treatment with losartan was started in the course of the disease, the better the effect, she added. (Mitten deformity is the result of fused skin between the fingers or toes, and the subsequent buildup of fibrotic tissue causes the hand or foot to contract.)

REFLECT is an investigator-initiated trial that started in 2017 and is being funded by DEBRA International. It is a dual-center, nonrandomized, single-arm study in which children aged 3-16 years with RDEB are treated with losartan for 10 months, with follow-up at 3 months.

Various secondary endpoints were included to look for the first signs of any efficacy: the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA), the Birmingham Epidermolysis Bullosa Severity Score (BEBS), the Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), the Itch Assessment Scale for the Pediatric Burn Patients, and two quality of life indices: the Quality of Life in EB (QOLEB) questionnaire and the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI).

Dr. Kiritsi highlighted a few of the secondary endpoint findings, saying that reduced BEBS scores showed there was “amelioration of the patients’ phenotype” and that EBDASI scores also decreased, with “nearly 60% of the patients having significant improvement of their skin disease.” Importantly, itch improved in most of the patients, she said. Reductions in CDLQI were observed, “meaning that quality of life was significantly better at the end of the trial.” There were also decreases in inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha.

Although there is no validated tool available to assess hand function, Dr. Kiritsi and her team used their own morphometric scoring instrument to measure how far the hand could stretch; their evaluations suggested that this measure improved – or at least did not worsen – with losartan treatment, she noted.

A larger, randomized trial is needed to confirm if there is any benefit of losartan, but first, a new, easy-to-swallow losartan formulation needs to be developed specifically for EB in the pediatric population, Dr. Kiritsi said. Although a pediatric suspension of losartan was previously available, it is no longer on the market, so the next step is to develop a formulation that could be used in a pivotal clinical trial, she noted.

“Losartan faces fewer technical hurdles compared to other novel treatments as it is an established medicine,” Dr. Kiritsi and associates observed in a poster presentation. There are still economic hurdles, however, since “with losartan patents expired, companies cannot expect to recoup an investment into clinical studies” and alternative funding sources are needed.

In 2019, losartan was granted an orphan drug designation for the treatment of EB from both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, but its use remains off label in children. “We decided to treat children,” Dr. Kiritsi said, “because we wanted to start as early as possible. If you already have mitten deformities, these cannot be reversed.”

DEBRA International funded the study. Dr. Kiritsi received research support from Rheacell GmbH and honoraria or consultation fees from Amryt Pharma and Rheacell GmbH. She has received other support from DEBRA International, EB Research Partnership, Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, German Research Foundation (funding of research projects), and 3R Pharma Consulting and Midas Pharma GmbH (consultation for losartan new drug formulation).

SOURCE: Kiritsi D et al. EB 2020. Poster 47.

LONDON – Treatment with the in an early clinical study.

In the ongoing phase 1/2 REFLECT (Recessive dystrophic EB: Mechanisms of fibrosis and its prevention with Losartan in vivo) trial, involving 29 children, no severe complications have been noted so far, according to one of the study investigators, Dimitra Kiritsi, MD, of the University of Freiburg, Germany. At the EB World Congress, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA), she presented interim data on 18 patients in the trial, emphasizing that the primary aim of the trial was to evaluate the safety of this treatment approach.

Over the 2 years the trial has been underway, 65 adverse events have been reported, of which 4 have been severe. Two of these were bacterial infections that required hospital treatment and the other two were a reduction in the general health condition of the child.

Losartan is an angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) that has been in clinical use for more than 25 years in adults and 15 years in children over the age of 6 years.

The drug may be used for treating recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB) in the future, Dr. Kiritsi said, because it attenuates tumor necrosis factor–beta (TGF-beta) signaling, which is thought to be involved in the fibrotic process. So while it may not target the genetic defect, it could help ameliorate the effects of the disease.

The precursor to REFLECT was a study performed in a mouse disease model of EB (EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1211-28) where a reduction in fibrotic scarring was seen with losartan with “remarkable effects” on “mitten” deformity, Dr. Kiritsi said. The results of that study suggested that the earlier treatment with losartan was started in the course of the disease, the better the effect, she added. (Mitten deformity is the result of fused skin between the fingers or toes, and the subsequent buildup of fibrotic tissue causes the hand or foot to contract.)

REFLECT is an investigator-initiated trial that started in 2017 and is being funded by DEBRA International. It is a dual-center, nonrandomized, single-arm study in which children aged 3-16 years with RDEB are treated with losartan for 10 months, with follow-up at 3 months.

Various secondary endpoints were included to look for the first signs of any efficacy: the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA), the Birmingham Epidermolysis Bullosa Severity Score (BEBS), the Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), the Itch Assessment Scale for the Pediatric Burn Patients, and two quality of life indices: the Quality of Life in EB (QOLEB) questionnaire and the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI).

Dr. Kiritsi highlighted a few of the secondary endpoint findings, saying that reduced BEBS scores showed there was “amelioration of the patients’ phenotype” and that EBDASI scores also decreased, with “nearly 60% of the patients having significant improvement of their skin disease.” Importantly, itch improved in most of the patients, she said. Reductions in CDLQI were observed, “meaning that quality of life was significantly better at the end of the trial.” There were also decreases in inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha.

Although there is no validated tool available to assess hand function, Dr. Kiritsi and her team used their own morphometric scoring instrument to measure how far the hand could stretch; their evaluations suggested that this measure improved – or at least did not worsen – with losartan treatment, she noted.

A larger, randomized trial is needed to confirm if there is any benefit of losartan, but first, a new, easy-to-swallow losartan formulation needs to be developed specifically for EB in the pediatric population, Dr. Kiritsi said. Although a pediatric suspension of losartan was previously available, it is no longer on the market, so the next step is to develop a formulation that could be used in a pivotal clinical trial, she noted.

“Losartan faces fewer technical hurdles compared to other novel treatments as it is an established medicine,” Dr. Kiritsi and associates observed in a poster presentation. There are still economic hurdles, however, since “with losartan patents expired, companies cannot expect to recoup an investment into clinical studies” and alternative funding sources are needed.

In 2019, losartan was granted an orphan drug designation for the treatment of EB from both the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, but its use remains off label in children. “We decided to treat children,” Dr. Kiritsi said, “because we wanted to start as early as possible. If you already have mitten deformities, these cannot be reversed.”

DEBRA International funded the study. Dr. Kiritsi received research support from Rheacell GmbH and honoraria or consultation fees from Amryt Pharma and Rheacell GmbH. She has received other support from DEBRA International, EB Research Partnership, Fritz Thyssen Stiftung, German Research Foundation (funding of research projects), and 3R Pharma Consulting and Midas Pharma GmbH (consultation for losartan new drug formulation).

SOURCE: Kiritsi D et al. EB 2020. Poster 47.

LONDON – Treatment with the in an early clinical study.

In the ongoing phase 1/2 REFLECT (Recessive dystrophic EB: Mechanisms of fibrosis and its prevention with Losartan in vivo) trial, involving 29 children, no severe complications have been noted so far, according to one of the study investigators, Dimitra Kiritsi, MD, of the University of Freiburg, Germany. At the EB World Congress, organized by the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Association (DEBRA), she presented interim data on 18 patients in the trial, emphasizing that the primary aim of the trial was to evaluate the safety of this treatment approach.

Over the 2 years the trial has been underway, 65 adverse events have been reported, of which 4 have been severe. Two of these were bacterial infections that required hospital treatment and the other two were a reduction in the general health condition of the child.

Losartan is an angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) that has been in clinical use for more than 25 years in adults and 15 years in children over the age of 6 years.

The drug may be used for treating recessive dystrophic EB (RDEB) in the future, Dr. Kiritsi said, because it attenuates tumor necrosis factor–beta (TGF-beta) signaling, which is thought to be involved in the fibrotic process. So while it may not target the genetic defect, it could help ameliorate the effects of the disease.

The precursor to REFLECT was a study performed in a mouse disease model of EB (EMBO Mol Med. 2015;7:1211-28) where a reduction in fibrotic scarring was seen with losartan with “remarkable effects” on “mitten” deformity, Dr. Kiritsi said. The results of that study suggested that the earlier treatment with losartan was started in the course of the disease, the better the effect, she added. (Mitten deformity is the result of fused skin between the fingers or toes, and the subsequent buildup of fibrotic tissue causes the hand or foot to contract.)

REFLECT is an investigator-initiated trial that started in 2017 and is being funded by DEBRA International. It is a dual-center, nonrandomized, single-arm study in which children aged 3-16 years with RDEB are treated with losartan for 10 months, with follow-up at 3 months.

Various secondary endpoints were included to look for the first signs of any efficacy: the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA), the Birmingham Epidermolysis Bullosa Severity Score (BEBS), the Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI), the Itch Assessment Scale for the Pediatric Burn Patients, and two quality of life indices: the Quality of Life in EB (QOLEB) questionnaire and the Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI).

Dr. Kiritsi highlighted a few of the secondary endpoint findings, saying that reduced BEBS scores showed there was “amelioration of the patients’ phenotype” and that EBDASI scores also decreased, with “nearly 60% of the patients having significant improvement of their skin disease.” Importantly, itch improved in most of the patients, she said. Reductions in CDLQI were observed, “meaning that quality of life was significantly better at the end of the trial.” There were also decreases in inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha.