User login

Laser Best Practices for Darker Skin Types

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

What does your patient need to know at the first visit? Does it apply to patients of all genders and ages?

Before performing laser procedures on patients with richly pigmented skin (Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI), patients need to be informed of the higher risk for pigmentary alterations as potential complications of the procedure. Specifically, hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation can occur postprocedure, depending on the type of device used, the treatment settings, the technique, the underlying skin disorder being treated, and the patient’s individual response to treatment. Fortunately, these pigment alterations are in most cases self-limited but can last for weeks to months depending on the severity and the nature of the dyspigmentation.

What are your go-to treatments? What are the side effects?

Notwithstanding the higher risks for pigmentary alterations, lasers can be extremely useful for the management of numerous dermatologic concerns in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI including laser hair removal for pseudofolliculitis barbae or nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring and pigmentary disorders. My go-to treatments include the following: long-pulsed 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser for hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin types V to VI, 808-nm diode laser with linear scanning of hair removal in Fitzpatrick skin type IV or less, 1550-nm erbium-doped nonablative fractional laser for acne scarring in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, and low-power diode 1927-nm fractional laser for melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI.

All of these procedures are performed with conservative treatment settings such as low fluences and longer pulse durations for laser hair removal and low treatment densities for fractional laser procedures. Prior to laser resurfacing, I recommend hydroquinone cream 4% twice daily starting 2 weeks before the first session and for 4 weeks posttreatment. These recommendations are based on published evidence (see Suggested Readings) as well as anecdotal experience.

How do you keep patients compliant with treatment?

Emphasizing the need for broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoidance of intense sun exposure before and after laser treatments is important during the initial consultation and prior to each treatment. I warn my patients of the higher risk for hyperpigmentation if the skin is tanned or has recently had intense sun exposure.

What do you do if they refuse treatment?

If patients refuse laser treatment or recommended precautions, then I will consider nonlaser treatment options.

What resources do you recommend to patients for more information?

I recommend patients visit the Skin of Color Society website (www.skinofcolorsociety.org).

Suggested Readings

- Alexis AF. Fractional laser resurfacing of acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2011;10(12 suppl):s6-s7.

- Alexis AF. Lasers and light-based therapies in ethnic skin: treatment options and recommendations for Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(suppl 3):91-97.

- Alexis AF, Coley MK, Nijhawan RI, et al. Nonablative fractional laser resurfacing for acne scarring in patients with Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:392-402.

- Battle EF, Hobbs LM. Laser-assisted hair removal for darker skin types. Dermatol Ther. 2004;17:177-183.

- Clark CM, Silverberg JI, Alexis AF. A retrospective chart review to assess the safety of nonablative fractional laser resurfacing in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:428-431.

- Ross EV, Cooke LM, Timko AL, et al. Treatment of pseudofolliculitis barbae in skin types IV, V, and VI with a long-pulsed neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet laser. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:263-270.

Exophytic Scalp Tumor

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

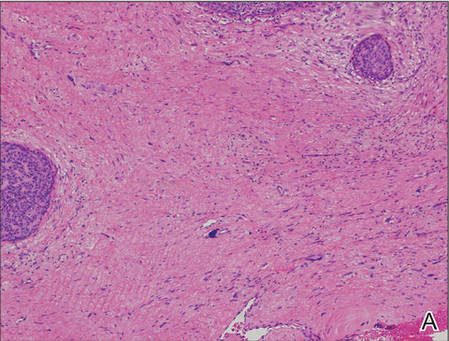

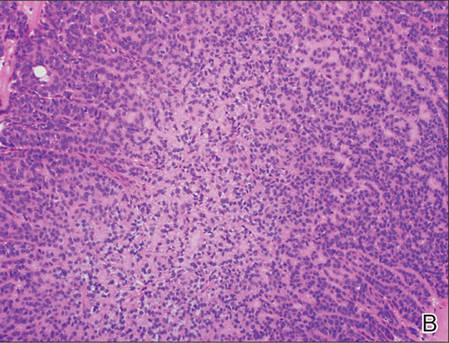

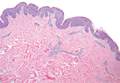

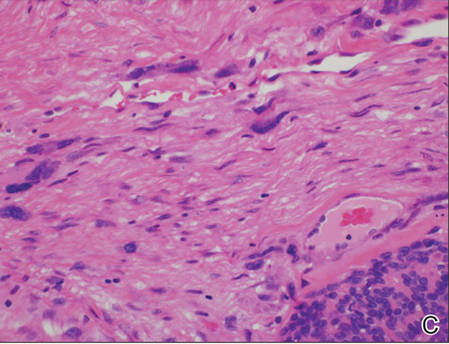

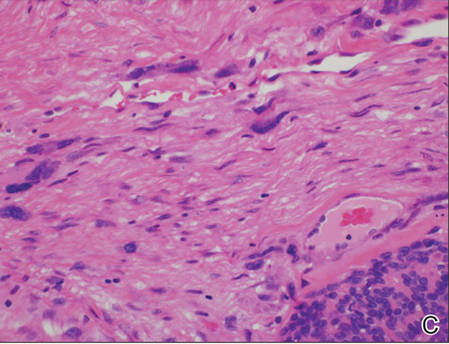

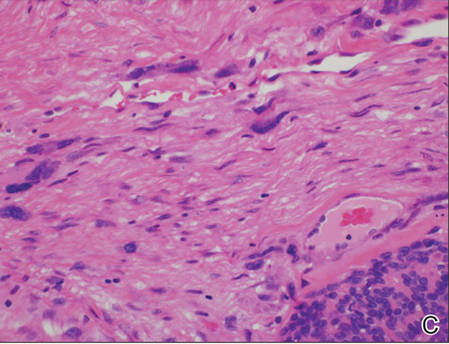

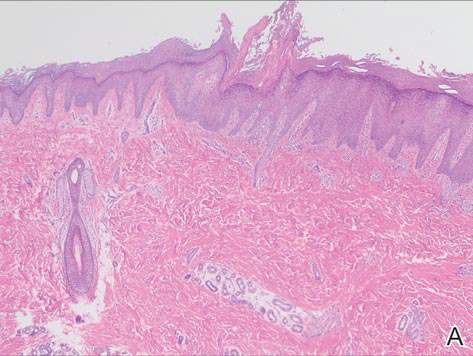

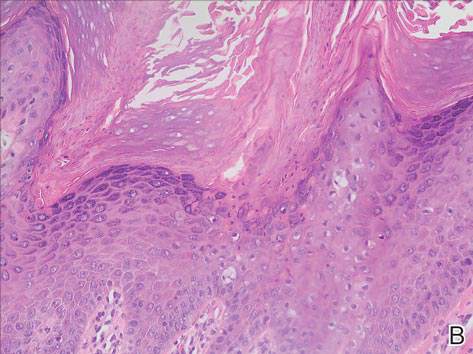

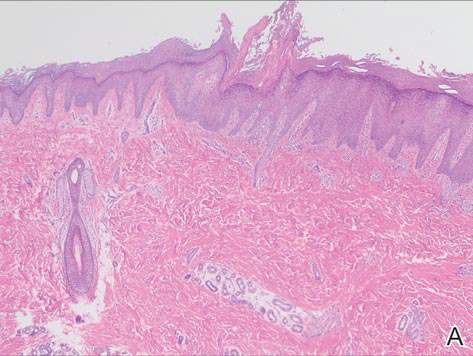

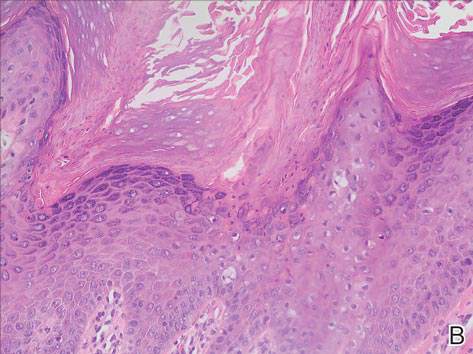

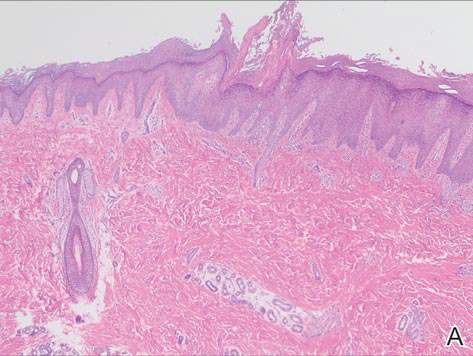

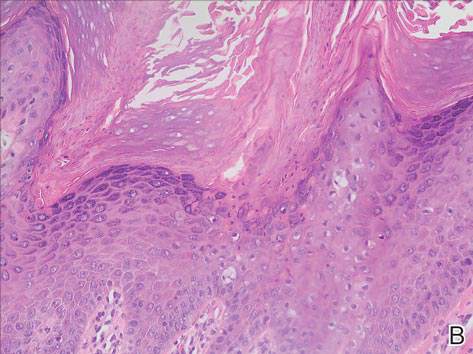

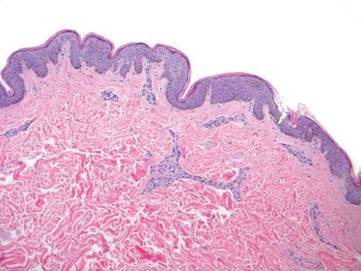

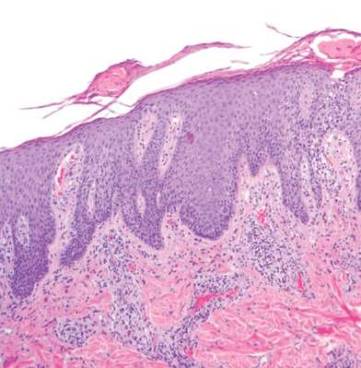

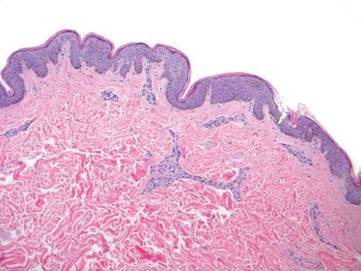

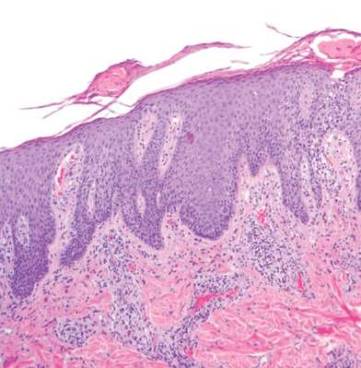

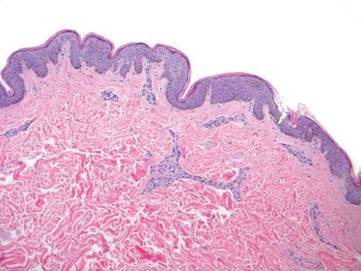

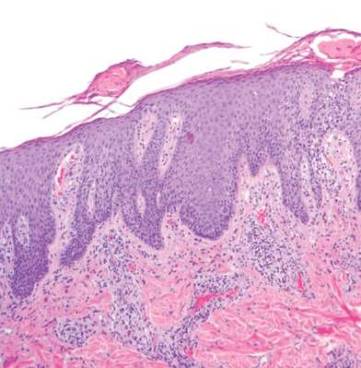

A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an infiltrating tumor consisting of malignant epithelial and stromal components (Figure). The basaloid and squamoid epithelial cells were keratin positive. The stromal cells demonstrated positivity for CD10 but were keratin negative. The epithelial portion of the tumor was composed mostly of basaloid islands of cells with nuclear pleomorphism, scattered mitoses, and focal sebaceous differentiation. The mesenchymal portion of the tumor displayed florid pleomorphism and polymorphism, with many large atypical cells and proliferation. A diagnosis of primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCC) was rendered. Head and neck computed tomography showed tumor penetration of less than 1 cm into scalp soft tissues with no involvement of the underlying bone. There was some evidence of swelling of the supragaleal soft tissues without indication of perineural spread. An 11-mm hyperlucent lower cervical lymph node on the left side that likely represented an incidental finding was noted. Surgical excision with margin evaluation was recommended, but the patient declined. He instead received radiation therapy to the left side of the posterior scalp with a total dose of 30 Gy at 6 Gy per fraction and 1 fraction daily. The patient was found to have a well-healed scar with no evidence of recurrence at 4-week follow-up and again at 5 months after radiation therapy.

|

|

|

| A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an inflitrating tumor consisting on malignant epithelial and stromal components (A-C)(H&E; original magnifications ×10, ×20, and ×40, respectively). |

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.1 Carcinosarcomas have been reported in both the male and female reproductive tracts, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, breasts, larynx, thymus, and thyroid but is uncommon as a primary neoplasm of the skin.2 Epidermal PCC occurs with greater frequency in males than in females and typically presents in the eighth or ninth decades of life.3 These tumors tend to arise in sun-exposed regions, most commonly on the face and scalp.2

Morphologically, PCCs typically are exophytic growths that often feature surface ulceration and may or may not bleed upon palpation.4 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas may present as long-standing lesions that have undergone rapid transformation in the weeks preceding presentation.4 It is not uncommon for PCC lesions to carry the clinical diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, which suggests notable morphologic overlap between these entities. Histopathologically, PCC shows a basal cell carcinoma and/or a squamous cell carcinoma epithelial component intimately admixed with a sarcomatous component.5 The mesenchymal component of PCC typically resembles a superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma characterized by pleomorphic nuclei and cytoplasm, necrosis, and an increased number of mitotic figures.2 Immunohistochemistry can be beneficial in the diagnosis of PCC. A combination of p63 and AE1/AE3 stains can be used to confirm cells of epithelial origin. Staining with vimentin, CD10, or caldesmon can help to delineate the mesenchymal component of PCC.

Epidermal PCC most commonly affects elderly individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure. It has been suggested that p53 mutations due to UV damage are key in tumor formation for both epithelial and mesenchymal elements.5 Literature supports a monoclonal origin for the epithelial and mesenchymal components of this tumor; however, there is insufficient evidence.6 Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for epidermal PCC, but adjuvant or substitutive radiotherapy has been used in some cases.4 The prognosis of PCC is notably better than its visceral counterpart due to early diagnosis and treatment of easily visible lesions. Epidermal PCC has a 70% 5-year disease-free survival rate, while adnexal PCC tends to occur in younger patients and has a 25% 5-year disease-free survival rate.3 Due to the rarity of reported cases and limited follow-up, the long-term prognosis for PCC remains unclear.

We report an unusual case of PCC on the scalp that was successfully treated with radiation therapy alone. This modality should be considered in patients with large tumors who refuse surgery or are not good surgical candidates.

1. El Harroudi T, Ech-Charif S, Amrani M, et al. Primary carcinosarcoma of the skin. J Hand Microsurg. 2010;2:79-81.

2. Patel NK, McKee PH, Smith NP. Primary metaplastic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:363-372.

3. Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

4. Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

5. Tran TA, Muller S, Chaudahri PJ, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: adnexal vs. epidermal types define high- and low-risk tumors. results of a meta-analysis. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:2-11.

6. Paniz Mondolfi AE, Jour G, Johnson M, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: insights into its clonal origin and mutational pattern expression analysis through next-generation sequencing. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2853-2860.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an infiltrating tumor consisting of malignant epithelial and stromal components (Figure). The basaloid and squamoid epithelial cells were keratin positive. The stromal cells demonstrated positivity for CD10 but were keratin negative. The epithelial portion of the tumor was composed mostly of basaloid islands of cells with nuclear pleomorphism, scattered mitoses, and focal sebaceous differentiation. The mesenchymal portion of the tumor displayed florid pleomorphism and polymorphism, with many large atypical cells and proliferation. A diagnosis of primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCC) was rendered. Head and neck computed tomography showed tumor penetration of less than 1 cm into scalp soft tissues with no involvement of the underlying bone. There was some evidence of swelling of the supragaleal soft tissues without indication of perineural spread. An 11-mm hyperlucent lower cervical lymph node on the left side that likely represented an incidental finding was noted. Surgical excision with margin evaluation was recommended, but the patient declined. He instead received radiation therapy to the left side of the posterior scalp with a total dose of 30 Gy at 6 Gy per fraction and 1 fraction daily. The patient was found to have a well-healed scar with no evidence of recurrence at 4-week follow-up and again at 5 months after radiation therapy.

|

|

|

| A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an inflitrating tumor consisting on malignant epithelial and stromal components (A-C)(H&E; original magnifications ×10, ×20, and ×40, respectively). |

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.1 Carcinosarcomas have been reported in both the male and female reproductive tracts, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, breasts, larynx, thymus, and thyroid but is uncommon as a primary neoplasm of the skin.2 Epidermal PCC occurs with greater frequency in males than in females and typically presents in the eighth or ninth decades of life.3 These tumors tend to arise in sun-exposed regions, most commonly on the face and scalp.2

Morphologically, PCCs typically are exophytic growths that often feature surface ulceration and may or may not bleed upon palpation.4 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas may present as long-standing lesions that have undergone rapid transformation in the weeks preceding presentation.4 It is not uncommon for PCC lesions to carry the clinical diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, which suggests notable morphologic overlap between these entities. Histopathologically, PCC shows a basal cell carcinoma and/or a squamous cell carcinoma epithelial component intimately admixed with a sarcomatous component.5 The mesenchymal component of PCC typically resembles a superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma characterized by pleomorphic nuclei and cytoplasm, necrosis, and an increased number of mitotic figures.2 Immunohistochemistry can be beneficial in the diagnosis of PCC. A combination of p63 and AE1/AE3 stains can be used to confirm cells of epithelial origin. Staining with vimentin, CD10, or caldesmon can help to delineate the mesenchymal component of PCC.

Epidermal PCC most commonly affects elderly individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure. It has been suggested that p53 mutations due to UV damage are key in tumor formation for both epithelial and mesenchymal elements.5 Literature supports a monoclonal origin for the epithelial and mesenchymal components of this tumor; however, there is insufficient evidence.6 Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for epidermal PCC, but adjuvant or substitutive radiotherapy has been used in some cases.4 The prognosis of PCC is notably better than its visceral counterpart due to early diagnosis and treatment of easily visible lesions. Epidermal PCC has a 70% 5-year disease-free survival rate, while adnexal PCC tends to occur in younger patients and has a 25% 5-year disease-free survival rate.3 Due to the rarity of reported cases and limited follow-up, the long-term prognosis for PCC remains unclear.

We report an unusual case of PCC on the scalp that was successfully treated with radiation therapy alone. This modality should be considered in patients with large tumors who refuse surgery or are not good surgical candidates.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an infiltrating tumor consisting of malignant epithelial and stromal components (Figure). The basaloid and squamoid epithelial cells were keratin positive. The stromal cells demonstrated positivity for CD10 but were keratin negative. The epithelial portion of the tumor was composed mostly of basaloid islands of cells with nuclear pleomorphism, scattered mitoses, and focal sebaceous differentiation. The mesenchymal portion of the tumor displayed florid pleomorphism and polymorphism, with many large atypical cells and proliferation. A diagnosis of primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCC) was rendered. Head and neck computed tomography showed tumor penetration of less than 1 cm into scalp soft tissues with no involvement of the underlying bone. There was some evidence of swelling of the supragaleal soft tissues without indication of perineural spread. An 11-mm hyperlucent lower cervical lymph node on the left side that likely represented an incidental finding was noted. Surgical excision with margin evaluation was recommended, but the patient declined. He instead received radiation therapy to the left side of the posterior scalp with a total dose of 30 Gy at 6 Gy per fraction and 1 fraction daily. The patient was found to have a well-healed scar with no evidence of recurrence at 4-week follow-up and again at 5 months after radiation therapy.

|

|

|

| A generous shave biopsy and debulking performed on the initial visit revealed an inflitrating tumor consisting on malignant epithelial and stromal components (A-C)(H&E; original magnifications ×10, ×20, and ×40, respectively). |

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm of unknown etiology that is characterized by the presence of both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.1 Carcinosarcomas have been reported in both the male and female reproductive tracts, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, lungs, breasts, larynx, thymus, and thyroid but is uncommon as a primary neoplasm of the skin.2 Epidermal PCC occurs with greater frequency in males than in females and typically presents in the eighth or ninth decades of life.3 These tumors tend to arise in sun-exposed regions, most commonly on the face and scalp.2

Morphologically, PCCs typically are exophytic growths that often feature surface ulceration and may or may not bleed upon palpation.4 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas may present as long-standing lesions that have undergone rapid transformation in the weeks preceding presentation.4 It is not uncommon for PCC lesions to carry the clinical diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma, which suggests notable morphologic overlap between these entities. Histopathologically, PCC shows a basal cell carcinoma and/or a squamous cell carcinoma epithelial component intimately admixed with a sarcomatous component.5 The mesenchymal component of PCC typically resembles a superficial malignant fibrous histiocytoma characterized by pleomorphic nuclei and cytoplasm, necrosis, and an increased number of mitotic figures.2 Immunohistochemistry can be beneficial in the diagnosis of PCC. A combination of p63 and AE1/AE3 stains can be used to confirm cells of epithelial origin. Staining with vimentin, CD10, or caldesmon can help to delineate the mesenchymal component of PCC.

Epidermal PCC most commonly affects elderly individuals with a history of extensive sun exposure. It has been suggested that p53 mutations due to UV damage are key in tumor formation for both epithelial and mesenchymal elements.5 Literature supports a monoclonal origin for the epithelial and mesenchymal components of this tumor; however, there is insufficient evidence.6 Surgical excision is the primary treatment modality for epidermal PCC, but adjuvant or substitutive radiotherapy has been used in some cases.4 The prognosis of PCC is notably better than its visceral counterpart due to early diagnosis and treatment of easily visible lesions. Epidermal PCC has a 70% 5-year disease-free survival rate, while adnexal PCC tends to occur in younger patients and has a 25% 5-year disease-free survival rate.3 Due to the rarity of reported cases and limited follow-up, the long-term prognosis for PCC remains unclear.

We report an unusual case of PCC on the scalp that was successfully treated with radiation therapy alone. This modality should be considered in patients with large tumors who refuse surgery or are not good surgical candidates.

1. El Harroudi T, Ech-Charif S, Amrani M, et al. Primary carcinosarcoma of the skin. J Hand Microsurg. 2010;2:79-81.

2. Patel NK, McKee PH, Smith NP. Primary metaplastic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:363-372.

3. Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

4. Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

5. Tran TA, Muller S, Chaudahri PJ, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: adnexal vs. epidermal types define high- and low-risk tumors. results of a meta-analysis. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:2-11.

6. Paniz Mondolfi AE, Jour G, Johnson M, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: insights into its clonal origin and mutational pattern expression analysis through next-generation sequencing. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2853-2860.

1. El Harroudi T, Ech-Charif S, Amrani M, et al. Primary carcinosarcoma of the skin. J Hand Microsurg. 2010;2:79-81.

2. Patel NK, McKee PH, Smith NP. Primary metaplastic carcinoma (carcinosarcoma) of the skin: a clinicopathologic study of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:363-372.

3. Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

4. Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

5. Tran TA, Muller S, Chaudahri PJ, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: adnexal vs. epidermal types define high- and low-risk tumors. results of a meta-analysis. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:2-11.

6. Paniz Mondolfi AE, Jour G, Johnson M, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: insights into its clonal origin and mutational pattern expression analysis through next-generation sequencing. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2853-2860.

An 81-year-old man presented with a 3.5×3.0-cm pink exophytic tumor with an eroded surface and prominent vascularity on the left side of the parietal scalp. The patient reported that the tumor had been present for more than 30 years but recently had grown larger in size. He denied pain or pruritus in association with the lesion and did not report any systemic symptoms. He had received no prior treatments for the tumor.

Prevalence of Glaucoma in Patients With Vitiligo

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disease of unknown etiology. Characterized by depigmented maculae and melanocytic destruction, it usually presents in childhood or young adulthood. The incidence of vitiligo ranges from 0.5% to 2% globally and there is no racial or gender predilection.1

Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.2 Noninflammatory depigmented lesions of the ocular fundus observed in vitiligo indicate a local loss of melanocytes.1 The fact that melanocytes are present not only in the skin and roots of the hair but also in the uvea and stria vascularis of the inner ear may explain the ophthalmologic disorders that accompany vitiligo.3 The term glaucoma refers to a large number of diseases that share a common feature: a distinctive and progressive optic neuropathy that may derive from various risks and is associated with a gradual loss of the visual field. If the disorder is not diagnosed and treated properly it could cause blindness.

Glaucoma is classified on the basis of the underlying abnormality that causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise. Glaucoma is first divided into open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma; glaucoma associated with developmental anomalies is then subdivided according to specific alterations.4

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vitiligo and glaucoma revealed only 1 study examining the incidence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo.5 In the study reported here, we determined the presence of and possible risk factors for glaucoma in patients with vitiligo who had presented to the dermatology polyclinic.

Methods

We registered 49 patients diagnosed with vitiligo by clinical and Wood light examination and 20 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients who were using topical corticosteroid treatments for vitiligo lesions located on the face were excluded from the study due to the glaucoma-inducing effects of corticosteroids. Similarly, patients who received drugs with sympathetic and parasympathetic action that can cause glaucoma were excluded.

The patients received a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included visual acuity testing, refraction, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and fundus examination. All patients and controls underwent visual field tests and optic nerve head analyses using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Glaucoma was diagnosed based on fundus examination, IOP measurement, field of vision evaluation, and optic nerve head analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the university hospital ethics committee.

Results

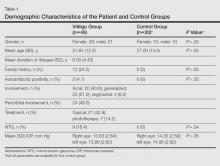

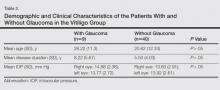

The study registered a total of 49 patients with vitiligo (28 female; 21 male) and 20 healthy controls (10 female; 10 male) with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Mean (SD) IOP values were 13.83 (2.84) mm Hg for the right eye and 13.89 (2.60) mm Hg for the left eye in the vitiligo group. Values were 14.35 (2.56) mm Hg and 14.95 (2.92) mm Hg, respectively, in the control group. The IOP differences between the 2 groups were not statistically significant (P>.05).

Nine patients (18.4%) in the vitiligo group were found to have signs of normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Optic nerve damage and vision loss occurs in the presence of normal IOP in NTG. There were no signs of NTG in the control group. Normal-tension glaucoma was diagnosed in the vitiligo group based on glaucomatous optic disc appearance, visual field defects, and structural analysis of the entire optic nerve head in confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. The NTG difference between the vitiligo and control groups was statistically significant (P=.04).

In the vitiligo group, of the 9 patients who had NTG, 6 had periorbital vitiligo lesions; the remaining 3 had none. Although patients who had periorbital lesions had a higher rate of glaucoma relative to the patients without periorbital lesions, the difference was not statistically significant (P>.05).

No statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between patients with vitiligo with and without glaucoma in terms of age, sex, disease duration, family history of vitiligo, presence or absence of periorbital involvement, manner of involvement, percentage of the involved body areas, and IOP (Table 1).

Comment

Glaucoma is characterized by increased IOP, visual field loss, and changes in the optic nerve head. Although elevated IOP is common in ocular hypertension as well as in glaucoma, there is no glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. In NTG, on the other hand, glaucomatous visual field loss and optic nerve head changes occur without an increase in IOP.6 Normal-tension glaucoma is a particular type of open-angle glaucoma. It is believed that NTG and high-tension glaucoma induce optic nerve head damage through different means.7 Alternative theories have been put forth to account for the glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve head that occurs in NTG, despite normal or close to normal IOP. These theories include vascular disorders (eg, ischemia, which interrupts the orthograde or retrograde axonal transport), excessive accumulation of free radicals, triggering of apoptosis, and low resistance of lamina cribrosa.8

Although there are various studies exploring ocular symptoms in patients with vitiligo,9-15 only 1 study has examined the incidence of glaucoma in this group of patients.5 Biswas et al11 examined ocular signs in 100 patients with vitiligo and found that 23% of patients had hypopigmented foci in the iris, 18% had pigmentation in the anterior chamber, 11% had chorioretinal degeneration, 9% had hypopigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, 5% had uveitis, and 34% were evaluated as normal. In this study, the authors concluded that there was a strong relationship between vitiligo and eye diseases.11 When Gopal et al9 compared the eye examinations of 150 vitiligo patients and 100 healthy controls, they found uveitis, iris, and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in 16% of the vitiligo patients (P<.001).

Rogosić et al5 examined the incidence of glaucoma in 42 patients with vitiligo and found primary open-angle glaucoma in 24 (57%) patients. The patients had a mean age of 56 years, mean disease duration of 13 years, and mean IOP of 18 mm Hg for the right eye and 17.5 mm Hg for the left eye. The incidence of glaucoma was significantly higher in patients with vitiligo (P<.001) and increased with disease duration.5

Similar studies, however, have failed to show a relationship between vitiligo and glaucoma. In a study that evaluated the retinal pigment epithelium and the optic nerve in patients with vitiligo, Perossini et al10 found that the fundus examination of the patients was perfectly normal.

In our study, we detected NTG in 18.4% of patients with vitiligo. We did not find a significant statistical difference between patients with and without glaucoma (Table 2). Rogosić et al5 found a significant relationship between age and glaucoma incidence, but we did not find such a relationship, which we believe is because the mean age of our patients was lower than the prior study.

In vitiligo, melanocytes are destroyed through an unknown mechanism. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms causing melanocytic destruction have not yet been determined, various hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. Among these, the most commonly held hypotheses are the neural, self-destruction, and autoimmune hypotheses.16

Based on the observation that stress and serious trauma could precipitate or trigger the onset of vitiligo,16 the neural hypothesis holds that neurochemical mediators released from the edges of the nerve endings exert toxic effects on melanocytes. The fact that both melanocytes and choroidal pigment cells originate from the mesenchyme and dermatomal spreading of segmental vitiligo are arguments propounded in favor of this hypothesis.17

The self-destruction hypothesis suggests that the intrinsic protective mechanisms that normally enable melanocytes to eliminate toxic intermediate products or metabolites on the melanogenesis path have been impaired in patients with vitiligo.18,19 There is evidence of increased oxidative stress over the whole epidermis of patients with vitiligo.20 Thus, free radicals affect melanin and cause membrane damage via lipid peroxidation reactions.21

The autoimmune hypothesis proposes a clinical relationship between vitiligo and several diseases believed to be autoimmune. Because the macrophage infiltration observed in vitiligo lesions is more pronounced on the perilesional skin, this hypothesis holds that macrophages may play a role in melanocyte removal.21 The Koebner phenomenon observed in vitiligo lends support to the critical role of trauma in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.

Although we could not explain the co-presence of vitiligo and glaucoma, we believe that it may result from the fact that both diseases are observed in tissues that have the same embryologic origin and etiology, perhaps vascular or neural disorders, excessive accumulation of free radicals, or the triggering of apoptosis. Dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo because glaucoma is an eye disease that progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss.

1. Ortonne JP. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JB, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:947-973.

2. Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB, et al. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:836-881.

3. van den Wijngaard R, Wijngaard R, Wankowiczs-Kalinsa A, et al. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061-1067.

4. Shields MB, Ritch R, Krupin T. Classification of the glaucomas. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, eds. The Glaucomas. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co; 1996:717-725.

5. Rogosić V, Bojić L, Puizina-Ivić N, et al. Vitiligo and glaucoma–an association or a coincidence? a pilot study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:21-26.

6. Anderson DR. Normal-tension glaucoma (low-tension glaucoma). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(suppl 59):S97-S101.

7. Iwata K. Primary open angle glaucoma and low tension glaucoma–pathogenesis and mechanism of optic nerve damage [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1501-1531.

8. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983;67:818-821.

9. Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, et al. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:162-165.

10. Perossini M, Turio E, Perossini T, et al. Vitiligo: ocular and electrophysiological findings. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:141-149.

11. Biswas G, Barbhuiya JN, Biswas MC, et al. Clinical pattern of ocular manifestations in vitiligo. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:478-480.

12. Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609-622.

13. Albert DM, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1145-1160.

14. Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16-26.

15. Cowan CL Jr, Halder RM, Grimes PE, et al. Ocular disturbances in vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:17-24.

16. Orecchia GE. Neural pathogenesis. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:142-150.

17. Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolf HH, et al. Disorders of melanin pigmentation. In: Bartels V, ed. Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000:1013-1042.

18. Tüzün Y, Kotoğyan A, Aydemir EH, et al. Pigmentasyon bozuklukları. In: Baransü O. Dermatoloji. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 1994:557-559.

19. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Disturbances of pigmentation. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000:1065-1068.

20. Schallreuter KU. Biochemical theory of vitiligo: a role of pteridines in pigmentation. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:151-159.

21. van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, et al. Local immune response in skin of generalized vitiligo patients. destruction of melanocytes is associated with the predominent presence of CLA+T cells at the perilesional site. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1299-1309.

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disease of unknown etiology. Characterized by depigmented maculae and melanocytic destruction, it usually presents in childhood or young adulthood. The incidence of vitiligo ranges from 0.5% to 2% globally and there is no racial or gender predilection.1

Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.2 Noninflammatory depigmented lesions of the ocular fundus observed in vitiligo indicate a local loss of melanocytes.1 The fact that melanocytes are present not only in the skin and roots of the hair but also in the uvea and stria vascularis of the inner ear may explain the ophthalmologic disorders that accompany vitiligo.3 The term glaucoma refers to a large number of diseases that share a common feature: a distinctive and progressive optic neuropathy that may derive from various risks and is associated with a gradual loss of the visual field. If the disorder is not diagnosed and treated properly it could cause blindness.

Glaucoma is classified on the basis of the underlying abnormality that causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise. Glaucoma is first divided into open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma; glaucoma associated with developmental anomalies is then subdivided according to specific alterations.4

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vitiligo and glaucoma revealed only 1 study examining the incidence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo.5 In the study reported here, we determined the presence of and possible risk factors for glaucoma in patients with vitiligo who had presented to the dermatology polyclinic.

Methods

We registered 49 patients diagnosed with vitiligo by clinical and Wood light examination and 20 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients who were using topical corticosteroid treatments for vitiligo lesions located on the face were excluded from the study due to the glaucoma-inducing effects of corticosteroids. Similarly, patients who received drugs with sympathetic and parasympathetic action that can cause glaucoma were excluded.

The patients received a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included visual acuity testing, refraction, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and fundus examination. All patients and controls underwent visual field tests and optic nerve head analyses using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Glaucoma was diagnosed based on fundus examination, IOP measurement, field of vision evaluation, and optic nerve head analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the university hospital ethics committee.

Results

The study registered a total of 49 patients with vitiligo (28 female; 21 male) and 20 healthy controls (10 female; 10 male) with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Mean (SD) IOP values were 13.83 (2.84) mm Hg for the right eye and 13.89 (2.60) mm Hg for the left eye in the vitiligo group. Values were 14.35 (2.56) mm Hg and 14.95 (2.92) mm Hg, respectively, in the control group. The IOP differences between the 2 groups were not statistically significant (P>.05).

Nine patients (18.4%) in the vitiligo group were found to have signs of normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Optic nerve damage and vision loss occurs in the presence of normal IOP in NTG. There were no signs of NTG in the control group. Normal-tension glaucoma was diagnosed in the vitiligo group based on glaucomatous optic disc appearance, visual field defects, and structural analysis of the entire optic nerve head in confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. The NTG difference between the vitiligo and control groups was statistically significant (P=.04).

In the vitiligo group, of the 9 patients who had NTG, 6 had periorbital vitiligo lesions; the remaining 3 had none. Although patients who had periorbital lesions had a higher rate of glaucoma relative to the patients without periorbital lesions, the difference was not statistically significant (P>.05).

No statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between patients with vitiligo with and without glaucoma in terms of age, sex, disease duration, family history of vitiligo, presence or absence of periorbital involvement, manner of involvement, percentage of the involved body areas, and IOP (Table 1).

Comment

Glaucoma is characterized by increased IOP, visual field loss, and changes in the optic nerve head. Although elevated IOP is common in ocular hypertension as well as in glaucoma, there is no glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. In NTG, on the other hand, glaucomatous visual field loss and optic nerve head changes occur without an increase in IOP.6 Normal-tension glaucoma is a particular type of open-angle glaucoma. It is believed that NTG and high-tension glaucoma induce optic nerve head damage through different means.7 Alternative theories have been put forth to account for the glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve head that occurs in NTG, despite normal or close to normal IOP. These theories include vascular disorders (eg, ischemia, which interrupts the orthograde or retrograde axonal transport), excessive accumulation of free radicals, triggering of apoptosis, and low resistance of lamina cribrosa.8

Although there are various studies exploring ocular symptoms in patients with vitiligo,9-15 only 1 study has examined the incidence of glaucoma in this group of patients.5 Biswas et al11 examined ocular signs in 100 patients with vitiligo and found that 23% of patients had hypopigmented foci in the iris, 18% had pigmentation in the anterior chamber, 11% had chorioretinal degeneration, 9% had hypopigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, 5% had uveitis, and 34% were evaluated as normal. In this study, the authors concluded that there was a strong relationship between vitiligo and eye diseases.11 When Gopal et al9 compared the eye examinations of 150 vitiligo patients and 100 healthy controls, they found uveitis, iris, and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in 16% of the vitiligo patients (P<.001).

Rogosić et al5 examined the incidence of glaucoma in 42 patients with vitiligo and found primary open-angle glaucoma in 24 (57%) patients. The patients had a mean age of 56 years, mean disease duration of 13 years, and mean IOP of 18 mm Hg for the right eye and 17.5 mm Hg for the left eye. The incidence of glaucoma was significantly higher in patients with vitiligo (P<.001) and increased with disease duration.5

Similar studies, however, have failed to show a relationship between vitiligo and glaucoma. In a study that evaluated the retinal pigment epithelium and the optic nerve in patients with vitiligo, Perossini et al10 found that the fundus examination of the patients was perfectly normal.

In our study, we detected NTG in 18.4% of patients with vitiligo. We did not find a significant statistical difference between patients with and without glaucoma (Table 2). Rogosić et al5 found a significant relationship between age and glaucoma incidence, but we did not find such a relationship, which we believe is because the mean age of our patients was lower than the prior study.

In vitiligo, melanocytes are destroyed through an unknown mechanism. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms causing melanocytic destruction have not yet been determined, various hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. Among these, the most commonly held hypotheses are the neural, self-destruction, and autoimmune hypotheses.16

Based on the observation that stress and serious trauma could precipitate or trigger the onset of vitiligo,16 the neural hypothesis holds that neurochemical mediators released from the edges of the nerve endings exert toxic effects on melanocytes. The fact that both melanocytes and choroidal pigment cells originate from the mesenchyme and dermatomal spreading of segmental vitiligo are arguments propounded in favor of this hypothesis.17

The self-destruction hypothesis suggests that the intrinsic protective mechanisms that normally enable melanocytes to eliminate toxic intermediate products or metabolites on the melanogenesis path have been impaired in patients with vitiligo.18,19 There is evidence of increased oxidative stress over the whole epidermis of patients with vitiligo.20 Thus, free radicals affect melanin and cause membrane damage via lipid peroxidation reactions.21

The autoimmune hypothesis proposes a clinical relationship between vitiligo and several diseases believed to be autoimmune. Because the macrophage infiltration observed in vitiligo lesions is more pronounced on the perilesional skin, this hypothesis holds that macrophages may play a role in melanocyte removal.21 The Koebner phenomenon observed in vitiligo lends support to the critical role of trauma in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.

Although we could not explain the co-presence of vitiligo and glaucoma, we believe that it may result from the fact that both diseases are observed in tissues that have the same embryologic origin and etiology, perhaps vascular or neural disorders, excessive accumulation of free radicals, or the triggering of apoptosis. Dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo because glaucoma is an eye disease that progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss.

Vitiligo is an acquired idiopathic disease of unknown etiology. Characterized by depigmented maculae and melanocytic destruction, it usually presents in childhood or young adulthood. The incidence of vitiligo ranges from 0.5% to 2% globally and there is no racial or gender predilection.1

Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.2 Noninflammatory depigmented lesions of the ocular fundus observed in vitiligo indicate a local loss of melanocytes.1 The fact that melanocytes are present not only in the skin and roots of the hair but also in the uvea and stria vascularis of the inner ear may explain the ophthalmologic disorders that accompany vitiligo.3 The term glaucoma refers to a large number of diseases that share a common feature: a distinctive and progressive optic neuropathy that may derive from various risks and is associated with a gradual loss of the visual field. If the disorder is not diagnosed and treated properly it could cause blindness.

Glaucoma is classified on the basis of the underlying abnormality that causes intraocular pressure (IOP) to rise. Glaucoma is first divided into open-angle and angle-closure glaucoma; glaucoma associated with developmental anomalies is then subdivided according to specific alterations.4

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms vitiligo and glaucoma revealed only 1 study examining the incidence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo.5 In the study reported here, we determined the presence of and possible risk factors for glaucoma in patients with vitiligo who had presented to the dermatology polyclinic.

Methods

We registered 49 patients diagnosed with vitiligo by clinical and Wood light examination and 20 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Patients who were using topical corticosteroid treatments for vitiligo lesions located on the face were excluded from the study due to the glaucoma-inducing effects of corticosteroids. Similarly, patients who received drugs with sympathetic and parasympathetic action that can cause glaucoma were excluded.

The patients received a comprehensive ophthalmologic examination that included visual acuity testing, refraction, IOP measurement, gonioscopy, and fundus examination. All patients and controls underwent visual field tests and optic nerve head analyses using a confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. Glaucoma was diagnosed based on fundus examination, IOP measurement, field of vision evaluation, and optic nerve head analysis.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The research protocol was approved by the university hospital ethics committee.

Results

The study registered a total of 49 patients with vitiligo (28 female; 21 male) and 20 healthy controls (10 female; 10 male) with a variety of demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1).

Mean (SD) IOP values were 13.83 (2.84) mm Hg for the right eye and 13.89 (2.60) mm Hg for the left eye in the vitiligo group. Values were 14.35 (2.56) mm Hg and 14.95 (2.92) mm Hg, respectively, in the control group. The IOP differences between the 2 groups were not statistically significant (P>.05).

Nine patients (18.4%) in the vitiligo group were found to have signs of normal-tension glaucoma (NTG). Optic nerve damage and vision loss occurs in the presence of normal IOP in NTG. There were no signs of NTG in the control group. Normal-tension glaucoma was diagnosed in the vitiligo group based on glaucomatous optic disc appearance, visual field defects, and structural analysis of the entire optic nerve head in confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope. The NTG difference between the vitiligo and control groups was statistically significant (P=.04).

In the vitiligo group, of the 9 patients who had NTG, 6 had periorbital vitiligo lesions; the remaining 3 had none. Although patients who had periorbital lesions had a higher rate of glaucoma relative to the patients without periorbital lesions, the difference was not statistically significant (P>.05).

No statistically significant differences (P>.05) were found between patients with vitiligo with and without glaucoma in terms of age, sex, disease duration, family history of vitiligo, presence or absence of periorbital involvement, manner of involvement, percentage of the involved body areas, and IOP (Table 1).

Comment

Glaucoma is characterized by increased IOP, visual field loss, and changes in the optic nerve head. Although elevated IOP is common in ocular hypertension as well as in glaucoma, there is no glaucomatous visual field loss in ocular hypertension. In NTG, on the other hand, glaucomatous visual field loss and optic nerve head changes occur without an increase in IOP.6 Normal-tension glaucoma is a particular type of open-angle glaucoma. It is believed that NTG and high-tension glaucoma induce optic nerve head damage through different means.7 Alternative theories have been put forth to account for the glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve head that occurs in NTG, despite normal or close to normal IOP. These theories include vascular disorders (eg, ischemia, which interrupts the orthograde or retrograde axonal transport), excessive accumulation of free radicals, triggering of apoptosis, and low resistance of lamina cribrosa.8

Although there are various studies exploring ocular symptoms in patients with vitiligo,9-15 only 1 study has examined the incidence of glaucoma in this group of patients.5 Biswas et al11 examined ocular signs in 100 patients with vitiligo and found that 23% of patients had hypopigmented foci in the iris, 18% had pigmentation in the anterior chamber, 11% had chorioretinal degeneration, 9% had hypopigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium, 5% had uveitis, and 34% were evaluated as normal. In this study, the authors concluded that there was a strong relationship between vitiligo and eye diseases.11 When Gopal et al9 compared the eye examinations of 150 vitiligo patients and 100 healthy controls, they found uveitis, iris, and retinal pigmentary abnormalities in 16% of the vitiligo patients (P<.001).

Rogosić et al5 examined the incidence of glaucoma in 42 patients with vitiligo and found primary open-angle glaucoma in 24 (57%) patients. The patients had a mean age of 56 years, mean disease duration of 13 years, and mean IOP of 18 mm Hg for the right eye and 17.5 mm Hg for the left eye. The incidence of glaucoma was significantly higher in patients with vitiligo (P<.001) and increased with disease duration.5

Similar studies, however, have failed to show a relationship between vitiligo and glaucoma. In a study that evaluated the retinal pigment epithelium and the optic nerve in patients with vitiligo, Perossini et al10 found that the fundus examination of the patients was perfectly normal.

In our study, we detected NTG in 18.4% of patients with vitiligo. We did not find a significant statistical difference between patients with and without glaucoma (Table 2). Rogosić et al5 found a significant relationship between age and glaucoma incidence, but we did not find such a relationship, which we believe is because the mean age of our patients was lower than the prior study.

In vitiligo, melanocytes are destroyed through an unknown mechanism. Although the cellular and molecular mechanisms causing melanocytic destruction have not yet been determined, various hypotheses have been put forward to explain the etiopathogenesis of vitiligo. Among these, the most commonly held hypotheses are the neural, self-destruction, and autoimmune hypotheses.16

Based on the observation that stress and serious trauma could precipitate or trigger the onset of vitiligo,16 the neural hypothesis holds that neurochemical mediators released from the edges of the nerve endings exert toxic effects on melanocytes. The fact that both melanocytes and choroidal pigment cells originate from the mesenchyme and dermatomal spreading of segmental vitiligo are arguments propounded in favor of this hypothesis.17

The self-destruction hypothesis suggests that the intrinsic protective mechanisms that normally enable melanocytes to eliminate toxic intermediate products or metabolites on the melanogenesis path have been impaired in patients with vitiligo.18,19 There is evidence of increased oxidative stress over the whole epidermis of patients with vitiligo.20 Thus, free radicals affect melanin and cause membrane damage via lipid peroxidation reactions.21

The autoimmune hypothesis proposes a clinical relationship between vitiligo and several diseases believed to be autoimmune. Because the macrophage infiltration observed in vitiligo lesions is more pronounced on the perilesional skin, this hypothesis holds that macrophages may play a role in melanocyte removal.21 The Koebner phenomenon observed in vitiligo lends support to the critical role of trauma in the etiopathogenesis of the disease.

Although we could not explain the co-presence of vitiligo and glaucoma, we believe that it may result from the fact that both diseases are observed in tissues that have the same embryologic origin and etiology, perhaps vascular or neural disorders, excessive accumulation of free radicals, or the triggering of apoptosis. Dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in patients with vitiligo because glaucoma is an eye disease that progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss.

1. Ortonne JP. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JB, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:947-973.

2. Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB, et al. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:836-881.

3. van den Wijngaard R, Wijngaard R, Wankowiczs-Kalinsa A, et al. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061-1067.

4. Shields MB, Ritch R, Krupin T. Classification of the glaucomas. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, eds. The Glaucomas. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co; 1996:717-725.

5. Rogosić V, Bojić L, Puizina-Ivić N, et al. Vitiligo and glaucoma–an association or a coincidence? a pilot study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:21-26.

6. Anderson DR. Normal-tension glaucoma (low-tension glaucoma). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(suppl 59):S97-S101.

7. Iwata K. Primary open angle glaucoma and low tension glaucoma–pathogenesis and mechanism of optic nerve damage [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1501-1531.

8. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983;67:818-821.

9. Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, et al. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:162-165.

10. Perossini M, Turio E, Perossini T, et al. Vitiligo: ocular and electrophysiological findings. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:141-149.

11. Biswas G, Barbhuiya JN, Biswas MC, et al. Clinical pattern of ocular manifestations in vitiligo. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:478-480.

12. Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609-622.

13. Albert DM, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1145-1160.

14. Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16-26.

15. Cowan CL Jr, Halder RM, Grimes PE, et al. Ocular disturbances in vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:17-24.

16. Orecchia GE. Neural pathogenesis. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:142-150.

17. Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolf HH, et al. Disorders of melanin pigmentation. In: Bartels V, ed. Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000:1013-1042.

18. Tüzün Y, Kotoğyan A, Aydemir EH, et al. Pigmentasyon bozuklukları. In: Baransü O. Dermatoloji. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 1994:557-559.

19. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Disturbances of pigmentation. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000:1065-1068.

20. Schallreuter KU. Biochemical theory of vitiligo: a role of pteridines in pigmentation. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:151-159.

21. van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, et al. Local immune response in skin of generalized vitiligo patients. destruction of melanocytes is associated with the predominent presence of CLA+T cells at the perilesional site. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1299-1309.

1. Ortonne JP. Vitiligo and other disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Bolognia JB, Jorizzo JL, Rapini RP, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. New York, NY: Mosby; 2003:947-973.

2. Ortonne JP, Bahadoran P, Fitzpatrick TB, et al. Hypomelanoses and hypermelanoses. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2003:836-881.

3. van den Wijngaard R, Wijngaard R, Wankowiczs-Kalinsa A, et al. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061-1067.

4. Shields MB, Ritch R, Krupin T. Classification of the glaucomas. In: Ritch R, Shields MB, Krupin T, eds. The Glaucomas. St Louis, MO: C.V. Mosby Co; 1996:717-725.

5. Rogosić V, Bojić L, Puizina-Ivić N, et al. Vitiligo and glaucoma–an association or a coincidence? a pilot study. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2010;18:21-26.

6. Anderson DR. Normal-tension glaucoma (low-tension glaucoma). Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011;59(suppl 59):S97-S101.

7. Iwata K. Primary open angle glaucoma and low tension glaucoma–pathogenesis and mechanism of optic nerve damage [in Japanese]. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1501-1531.

8. Hitchings RA, Anderton SA. A comparative study of visual field defects seen in patients with low-tension glaucoma and chronic simple glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 1983;67:818-821.

9. Gopal KV, Rama Rao GR, Kumar YH, et al. Vitiligo: a part of a systemic autoimmune process. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:162-165.

10. Perossini M, Turio E, Perossini T, et al. Vitiligo: ocular and electrophysiological findings. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2010;145:141-149.

11. Biswas G, Barbhuiya JN, Biswas MC, et al. Clinical pattern of ocular manifestations in vitiligo. J Indian Med Assoc. 2003;101:478-480.

12. Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609-622.

13. Albert DM, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Ocular abnormalities occurring with vitiligo. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:1145-1160.

14. Wagoner MD, Albert DM, Lerner AB, et al. New observations on vitiligo and ocular disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;96:16-26.

15. Cowan CL Jr, Halder RM, Grimes PE, et al. Ocular disturbances in vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:17-24.

16. Orecchia GE. Neural pathogenesis. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. Oxford, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:142-150.

17. Braun-Falco O, Plewig G, Wolf HH, et al. Disorders of melanin pigmentation. In: Bartels V, ed. Dermatology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2000:1013-1042.

18. Tüzün Y, Kotoğyan A, Aydemir EH, et al. Pigmentasyon bozuklukları. In: Baransü O. Dermatoloji. 2nd ed. Istanbul: Nobel Tıp Kitabevi; 1994:557-559.

19. Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Disturbances of pigmentation. In: Odom RB, James WD, Berger TG. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Company; 2000:1065-1068.

20. Schallreuter KU. Biochemical theory of vitiligo: a role of pteridines in pigmentation. In: Hann SK, Nordlund JJ. Vitiligo. London, England: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2000:151-159.

21. van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Le Poole C, et al. Local immune response in skin of generalized vitiligo patients. destruction of melanocytes is associated with the predominent presence of CLA+T cells at the perilesional site. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1299-1309.

Practice Points

- Patients with vitiligo may exhibit pigmentary abnormalities of the iris and retina.

- Normal-tension glaucoma may develop in patients with vitiligo.

- Glaucoma progresses slowly and may lead to vision loss; as a result, dermatologists should be alert to the presence of glaucoma in vitiligo patients.

Clinical Pearl: Increasing Utility of Isopropyl Alcohol for Cutaneous Dyschromia

Practice Gap

Conditions with dyschromia including terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (CARP), and acanthosis nigricans are difficult to distinguish from one another.

Diagnostic Tools

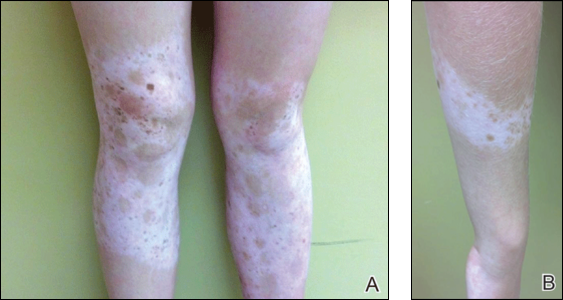

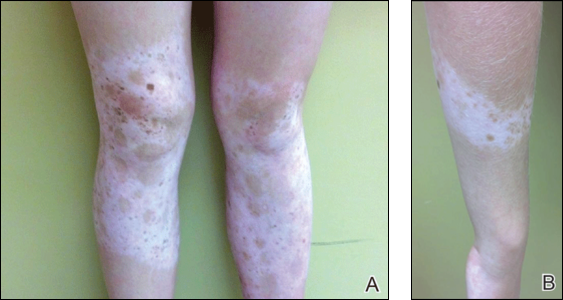

Since its development in 1920, dermatologists have utilized isopropyl alcohol in ways that exceed conventional antimicrobial purposes. If TFFP, CARP, and acanthosis nigricans are suspected, the first step in any algorithmic approach should be to rub the skin with an alcohol pad using firm continuous pressure in an attempt to remove pigmentation. Complete resolution of dyspigmentation strongly supports a diagnosis of TFFD1 and can be curative (Figure). Alcohol can similarly lighten CARP but to a lesser degree than TFFD.2 In contrast, acanthosis nigricans will display minimal to no improvement with isopropyl alcohol.

Practice Implications

Isopropyl alcohol has few side effects and each swab costs less than a dime. It is extremely cost effective compared to biopsy and subsequent pathology and laboratory costs. Patients appreciate a noninvasive initial approach, and it is rewarding to treat a cosmetically disturbing condition with ease.

Swabbing the skin with alcohol pads reflects light and improves visualization of veins that should be avoided during surgery. Alcohol-based gel inhibits bacterial colonization, reduces dermatoscope-related nosocomial infection, and enhances dermoscopic resolution.3 Alcohol swabs quickly remove gentian violet, which aids in porokeratosis diagnosis; the pathognomonic cornoid lamella of porokeratosis retains gentian violet.4 A solution of 70% isopropyl alcohol preserves myiasis larvae better than formalin, which causes larval tissue hardening. Alcohol also can be squeezed into the central punctum in myiasis as a form of treatment.5 In conclusion, alcohol represents a convenient, inexpensive, and helpful tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium that should not be forgotten.

- Browning J, Rosen T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis revisited. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Berk DR. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis response to 70% alcohol swabbing. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:247-248.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.

- Thomas CJ, Elston DM. Medical pearl: Gentian violet to highlight the cornoid lamella in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3, pt 1):513-514.

- Meinking TL, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Changing paradigms in parasitic infections: common dermatological helminthic infections and cutaneous myiasis. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:407-416.

Practice Gap

Conditions with dyschromia including terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (CARP), and acanthosis nigricans are difficult to distinguish from one another.

Diagnostic Tools

Since its development in 1920, dermatologists have utilized isopropyl alcohol in ways that exceed conventional antimicrobial purposes. If TFFP, CARP, and acanthosis nigricans are suspected, the first step in any algorithmic approach should be to rub the skin with an alcohol pad using firm continuous pressure in an attempt to remove pigmentation. Complete resolution of dyspigmentation strongly supports a diagnosis of TFFD1 and can be curative (Figure). Alcohol can similarly lighten CARP but to a lesser degree than TFFD.2 In contrast, acanthosis nigricans will display minimal to no improvement with isopropyl alcohol.

Practice Implications

Isopropyl alcohol has few side effects and each swab costs less than a dime. It is extremely cost effective compared to biopsy and subsequent pathology and laboratory costs. Patients appreciate a noninvasive initial approach, and it is rewarding to treat a cosmetically disturbing condition with ease.

Swabbing the skin with alcohol pads reflects light and improves visualization of veins that should be avoided during surgery. Alcohol-based gel inhibits bacterial colonization, reduces dermatoscope-related nosocomial infection, and enhances dermoscopic resolution.3 Alcohol swabs quickly remove gentian violet, which aids in porokeratosis diagnosis; the pathognomonic cornoid lamella of porokeratosis retains gentian violet.4 A solution of 70% isopropyl alcohol preserves myiasis larvae better than formalin, which causes larval tissue hardening. Alcohol also can be squeezed into the central punctum in myiasis as a form of treatment.5 In conclusion, alcohol represents a convenient, inexpensive, and helpful tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium that should not be forgotten.

Practice Gap

Conditions with dyschromia including terra firma-forme dermatosis (TFFD), confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (CARP), and acanthosis nigricans are difficult to distinguish from one another.

Diagnostic Tools

Since its development in 1920, dermatologists have utilized isopropyl alcohol in ways that exceed conventional antimicrobial purposes. If TFFP, CARP, and acanthosis nigricans are suspected, the first step in any algorithmic approach should be to rub the skin with an alcohol pad using firm continuous pressure in an attempt to remove pigmentation. Complete resolution of dyspigmentation strongly supports a diagnosis of TFFD1 and can be curative (Figure). Alcohol can similarly lighten CARP but to a lesser degree than TFFD.2 In contrast, acanthosis nigricans will display minimal to no improvement with isopropyl alcohol.

Practice Implications

Isopropyl alcohol has few side effects and each swab costs less than a dime. It is extremely cost effective compared to biopsy and subsequent pathology and laboratory costs. Patients appreciate a noninvasive initial approach, and it is rewarding to treat a cosmetically disturbing condition with ease.

Swabbing the skin with alcohol pads reflects light and improves visualization of veins that should be avoided during surgery. Alcohol-based gel inhibits bacterial colonization, reduces dermatoscope-related nosocomial infection, and enhances dermoscopic resolution.3 Alcohol swabs quickly remove gentian violet, which aids in porokeratosis diagnosis; the pathognomonic cornoid lamella of porokeratosis retains gentian violet.4 A solution of 70% isopropyl alcohol preserves myiasis larvae better than formalin, which causes larval tissue hardening. Alcohol also can be squeezed into the central punctum in myiasis as a form of treatment.5 In conclusion, alcohol represents a convenient, inexpensive, and helpful tool in the dermatologist’s armamentarium that should not be forgotten.

- Browning J, Rosen T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis revisited. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Berk DR. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis response to 70% alcohol swabbing. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:247-248.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.

- Thomas CJ, Elston DM. Medical pearl: Gentian violet to highlight the cornoid lamella in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3, pt 1):513-514.

- Meinking TL, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Changing paradigms in parasitic infections: common dermatological helminthic infections and cutaneous myiasis. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:407-416.

- Browning J, Rosen T. Terra firma-forme dermatosis revisited. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:15.

- Berk DR. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis response to 70% alcohol swabbing. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:247-248.

- Kelly SC, Purcell SM. Prevention of nosocomial infection during dermoscopy? Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:552-555.

- Thomas CJ, Elston DM. Medical pearl: Gentian violet to highlight the cornoid lamella in disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(3, pt 1):513-514.

- Meinking TL, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Changing paradigms in parasitic infections: common dermatological helminthic infections and cutaneous myiasis. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:407-416.

Diagnosing Porokeratosis of Mibelli Every Time: A Novel Biopsy Technique to Maximize Histopathologic Confirmation

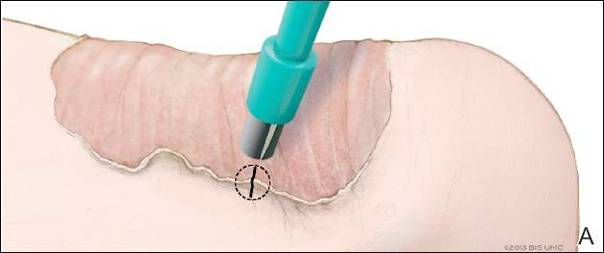

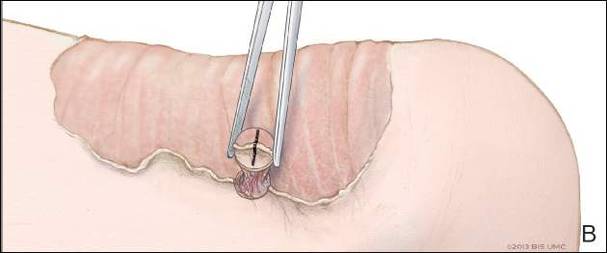

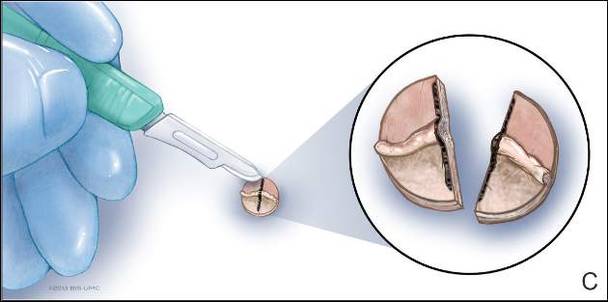

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

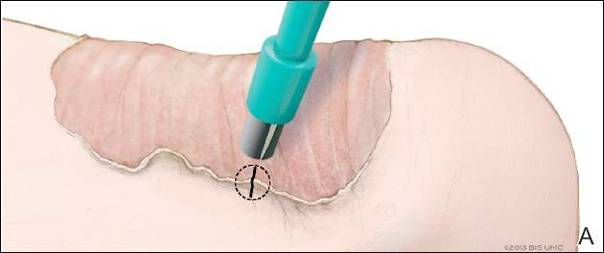

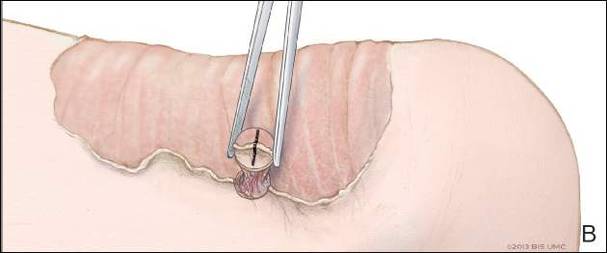

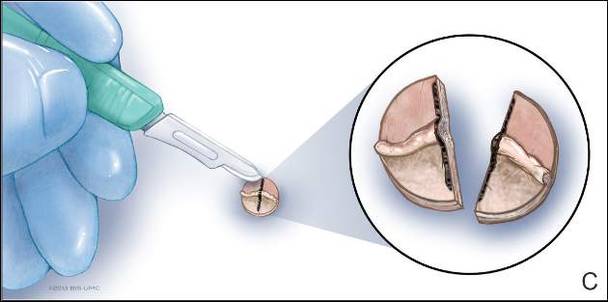

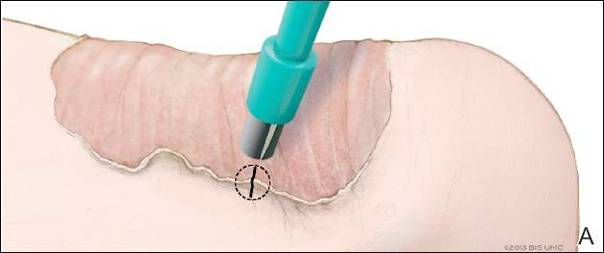

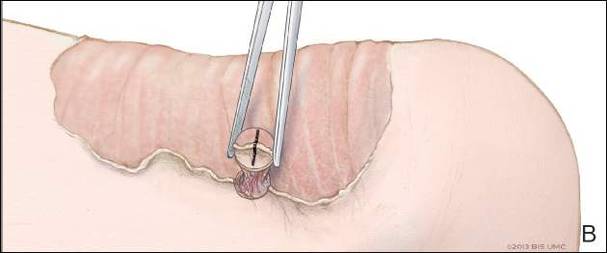

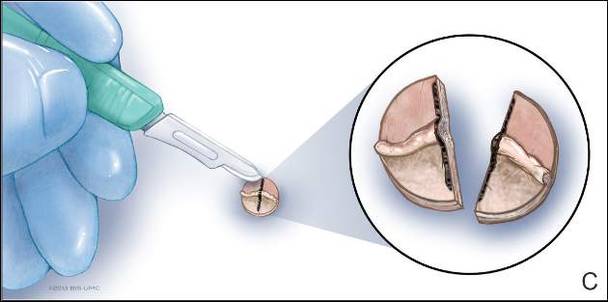

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.