User login

New JAK inhibitor study data confirm benefit in alopecia areata

from clinical trials of two drugs presented at a late-breaker research session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Based on phase 3 studies that document robust hair growth in about one third of patients, deuruxolitinib (CTP-543), an inhibitor of the JAK1 and JAK2 enzymes, has the potential to become the second JAK inhibitor available for the treatment of alopecia areata. If approved, it will join baricitinib (Olumiant), which received U.S. approval almost 1 year ago.

In his talk on THRIVE-AA2, a phase 3 trial of the investigational medicine deuruxolitinib, the principal investigator, Brett A. King, MD, PhD, displayed several before-and-after photos and said, “The photos tell the whole story. This is why there is so much excitement about these drugs.”

THRIVE-AA2 was the second of two phase 3 studies of deuruxolitinib. King was a principal investigator for both pivotal trials, called THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE AA-2. He characterized the results of the two THRIVE trials as “comparable.”

Dr. King also was a principal investigator for the trials with baricitinib, called BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE AA-2, which were published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trials for both drugs had similar designs and endpoints.

Deuruxolitinib and the THRIVE studies

In the THRIVE-AA2 trial, 517 adult patients were enrolled with moderate to severe alopecia areata, defined as a SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) score of ≥ 50%, which signifies a hair loss of at least 50%. Like THRIVE-AA1, patients participated at treatment centers in North America and Europe. About two-thirds were female. The mean age was 39 years. The majority of patients had complete or near complete hair loss at baseline.

“Many of these patients are the ones we have historically characterized as having alopecia totalis or universalis,” Dr. King said.

Participating patients were randomly assigned to 8 mg deuruxolitinib twice daily, 12 mg deuruxolitinib twice daily, or placebo. The primary endpoint was a SALT score of ≤ 20% at week 24.

At 24 weeks, almost no patients in the placebo group (1%) vs. 33% and 38% in the 8 mg and 12 mg twice-daily groups, respectively, met the primary endpoint. Each active treatment group was highly significant vs. placebo.

Of the responders, the majority achieved complete or near complete hair growth as defined by a SALT score of ≤ 10%, Dr. King reported.

Based on a graph that showed a relatively steep climb over the entire 24-week study period, deuruxolitinib “had a really fast onset of action,” Dr. King said. By week 8, which was the time of the first assessment, both doses of deuruxolitinib were superior to placebo.

The majority of patients had complete or significant loss of eyebrows and eye lashes at baseline, but more than two-thirds of these patients had regrowth by week 24, Dr. King said. Again, no significant regrowth was observed in the placebo arm.

On the Satisfaction of Hair Patient Reported Outcomes (SPRO), more than half of patients on both doses reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the improvement when evaluated at 24 weeks.

“The patient satisfaction overshot what one would expect by looking at the SALT scores, but a lot of subjects were at the precipice of the primary endpoint, sitting on SALT scores of 21, 25, or 30,” Dr. King said.

High participation in extension trial

More than 90% of the patients assigned to deuruxolitinib completed the trial and have entered an open-label extension (OLE). Dr. King credited the substantial rates of hair growth and the low rate of significant adverse events for the high rate of transition to OLE. Those who experienced the response were motivated to maintain it.

“This is a devastating disease. Patients want to get better,” Dr. King said.

There were no serious treatment-emergent adverse events associated with deuruxolitinib, including no thromboembolic events or other off-target events that have been reported previously with other JAK inhibitors in other disease states, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Although some adverse events, such as nasopharyngitis, were observed more often in those taking deuruxolitinib than placebo, there were “very few” discontinuations because of an adverse event, he said.

The data of THRIVE-AA2 are wholly compatible with the previously reported 706-patient THRIVE-AA1, according to Dr. King. In THRIVE-AA1, the primary endpoint of SALT ≤ 20% was reached by 29.6%, 41.5%, and 0.8% of the 8 mg, 12 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Patient satisfaction scores, safety, and tolerability were also similar, according to Dr. King.

The experience with deuruxolitinib in the THRIVE-AA phase 3 program is similar to the experience with baricitinib in the BRAVE-AA trials. Although they cannot be compared directly because of potential differences between study populations, the 4-mg dose of baricitinib also achieved SALT score ≤ 20 in about 35% of patients, he said. The proportion was lower in the 2-mg group but was also superior to the placebo group.

“JAK inhibitors are changing the paradigm of alopecia areata,” Dr. King said. Responding to a question about payers reluctant to reimburse therapies for a “cosmetic” condition, Dr. King added that the effective treatments are “changing the landscape of how we think about this disease.” Dr. King believes these kinds of data show that “we are literally transforming lives forever.”

Baricitinib and the BRAVE studies

When baricitinib received regulatory approval for alopecia areata last year, it was not just the first JAK inhibitor approved for this disease, but the first systemic therapy of any kind, according to Maryanne Senna, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the director of the Lahey Hair Loss Center of Excellence, Burlington, Mass. Dr. Senna was a clinical investigator of BRAVE-AA1, as well as of THRIVE-AA2.

Providing an update on the BRAVE-AA program, Dr. Senna reported 104-week data that appear to support the idea of a life-changing benefit from JAK inhibitor therapy. This is because the effects appear durable.

In the data she presented at the AAD, responders and mixed responders at 52 weeks were followed to 104 weeks. Mixed responders were defined as those without a SALT response of ≤ 20 at week 52 but who had achieved this degree of hair regrowth at some earlier point.

Of the responders, 90% maintained their response at 104 weeks. In addition, many of the mixed responders and patients with a partial response but who never achieved a SALT score ≤ 20% gained additional hair growth, including complete or near complete hair growth, when maintained on treatment over the 2 years of follow-up.

“The follow-up suggests that, if you keep patients on treatment, you can get many of them to a meaningful response,” she said.

Meanwhile, “there have been no new safety signals,” Dr. Senna said. She based this statement not only of the 104-week data but on follow-up of up to 3.6 years among patients who have remained on treatment after participating in previous studies.

According to Dr. Senna, the off-target events that have been reported previously in other diseases with other JAK inhibitors, such as major adverse cardiovascular events and thromboembolic events, have not so far been observed in the BRAVE-AA phase 3 program.

Baricitinib, much like all but one of the JAK inhibitors with dermatologic indications, carries a black box warning that lists multiple risks for drugs in this class, based on a rheumatoid arthritis study.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted deuruxolitinib Breakthrough Therapy designation for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata and Fast Track designation for the treatment of alopecia areata, according to its manufacturer Concert Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. King reports financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Concert Pharmaceuticals, which provided the funding for the THRIVE-AA trial program, and for Eli Lilly, which provided funding for the BRAVE-AA trial program. Dr. Senna reports financial relationships with Arena pharmaceuticals, Follica, and both Concert Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

from clinical trials of two drugs presented at a late-breaker research session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Based on phase 3 studies that document robust hair growth in about one third of patients, deuruxolitinib (CTP-543), an inhibitor of the JAK1 and JAK2 enzymes, has the potential to become the second JAK inhibitor available for the treatment of alopecia areata. If approved, it will join baricitinib (Olumiant), which received U.S. approval almost 1 year ago.

In his talk on THRIVE-AA2, a phase 3 trial of the investigational medicine deuruxolitinib, the principal investigator, Brett A. King, MD, PhD, displayed several before-and-after photos and said, “The photos tell the whole story. This is why there is so much excitement about these drugs.”

THRIVE-AA2 was the second of two phase 3 studies of deuruxolitinib. King was a principal investigator for both pivotal trials, called THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE AA-2. He characterized the results of the two THRIVE trials as “comparable.”

Dr. King also was a principal investigator for the trials with baricitinib, called BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE AA-2, which were published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trials for both drugs had similar designs and endpoints.

Deuruxolitinib and the THRIVE studies

In the THRIVE-AA2 trial, 517 adult patients were enrolled with moderate to severe alopecia areata, defined as a SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) score of ≥ 50%, which signifies a hair loss of at least 50%. Like THRIVE-AA1, patients participated at treatment centers in North America and Europe. About two-thirds were female. The mean age was 39 years. The majority of patients had complete or near complete hair loss at baseline.

“Many of these patients are the ones we have historically characterized as having alopecia totalis or universalis,” Dr. King said.

Participating patients were randomly assigned to 8 mg deuruxolitinib twice daily, 12 mg deuruxolitinib twice daily, or placebo. The primary endpoint was a SALT score of ≤ 20% at week 24.

At 24 weeks, almost no patients in the placebo group (1%) vs. 33% and 38% in the 8 mg and 12 mg twice-daily groups, respectively, met the primary endpoint. Each active treatment group was highly significant vs. placebo.

Of the responders, the majority achieved complete or near complete hair growth as defined by a SALT score of ≤ 10%, Dr. King reported.

Based on a graph that showed a relatively steep climb over the entire 24-week study period, deuruxolitinib “had a really fast onset of action,” Dr. King said. By week 8, which was the time of the first assessment, both doses of deuruxolitinib were superior to placebo.

The majority of patients had complete or significant loss of eyebrows and eye lashes at baseline, but more than two-thirds of these patients had regrowth by week 24, Dr. King said. Again, no significant regrowth was observed in the placebo arm.

On the Satisfaction of Hair Patient Reported Outcomes (SPRO), more than half of patients on both doses reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the improvement when evaluated at 24 weeks.

“The patient satisfaction overshot what one would expect by looking at the SALT scores, but a lot of subjects were at the precipice of the primary endpoint, sitting on SALT scores of 21, 25, or 30,” Dr. King said.

High participation in extension trial

More than 90% of the patients assigned to deuruxolitinib completed the trial and have entered an open-label extension (OLE). Dr. King credited the substantial rates of hair growth and the low rate of significant adverse events for the high rate of transition to OLE. Those who experienced the response were motivated to maintain it.

“This is a devastating disease. Patients want to get better,” Dr. King said.

There were no serious treatment-emergent adverse events associated with deuruxolitinib, including no thromboembolic events or other off-target events that have been reported previously with other JAK inhibitors in other disease states, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Although some adverse events, such as nasopharyngitis, were observed more often in those taking deuruxolitinib than placebo, there were “very few” discontinuations because of an adverse event, he said.

The data of THRIVE-AA2 are wholly compatible with the previously reported 706-patient THRIVE-AA1, according to Dr. King. In THRIVE-AA1, the primary endpoint of SALT ≤ 20% was reached by 29.6%, 41.5%, and 0.8% of the 8 mg, 12 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Patient satisfaction scores, safety, and tolerability were also similar, according to Dr. King.

The experience with deuruxolitinib in the THRIVE-AA phase 3 program is similar to the experience with baricitinib in the BRAVE-AA trials. Although they cannot be compared directly because of potential differences between study populations, the 4-mg dose of baricitinib also achieved SALT score ≤ 20 in about 35% of patients, he said. The proportion was lower in the 2-mg group but was also superior to the placebo group.

“JAK inhibitors are changing the paradigm of alopecia areata,” Dr. King said. Responding to a question about payers reluctant to reimburse therapies for a “cosmetic” condition, Dr. King added that the effective treatments are “changing the landscape of how we think about this disease.” Dr. King believes these kinds of data show that “we are literally transforming lives forever.”

Baricitinib and the BRAVE studies

When baricitinib received regulatory approval for alopecia areata last year, it was not just the first JAK inhibitor approved for this disease, but the first systemic therapy of any kind, according to Maryanne Senna, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the director of the Lahey Hair Loss Center of Excellence, Burlington, Mass. Dr. Senna was a clinical investigator of BRAVE-AA1, as well as of THRIVE-AA2.

Providing an update on the BRAVE-AA program, Dr. Senna reported 104-week data that appear to support the idea of a life-changing benefit from JAK inhibitor therapy. This is because the effects appear durable.

In the data she presented at the AAD, responders and mixed responders at 52 weeks were followed to 104 weeks. Mixed responders were defined as those without a SALT response of ≤ 20 at week 52 but who had achieved this degree of hair regrowth at some earlier point.

Of the responders, 90% maintained their response at 104 weeks. In addition, many of the mixed responders and patients with a partial response but who never achieved a SALT score ≤ 20% gained additional hair growth, including complete or near complete hair growth, when maintained on treatment over the 2 years of follow-up.

“The follow-up suggests that, if you keep patients on treatment, you can get many of them to a meaningful response,” she said.

Meanwhile, “there have been no new safety signals,” Dr. Senna said. She based this statement not only of the 104-week data but on follow-up of up to 3.6 years among patients who have remained on treatment after participating in previous studies.

According to Dr. Senna, the off-target events that have been reported previously in other diseases with other JAK inhibitors, such as major adverse cardiovascular events and thromboembolic events, have not so far been observed in the BRAVE-AA phase 3 program.

Baricitinib, much like all but one of the JAK inhibitors with dermatologic indications, carries a black box warning that lists multiple risks for drugs in this class, based on a rheumatoid arthritis study.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted deuruxolitinib Breakthrough Therapy designation for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata and Fast Track designation for the treatment of alopecia areata, according to its manufacturer Concert Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. King reports financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Concert Pharmaceuticals, which provided the funding for the THRIVE-AA trial program, and for Eli Lilly, which provided funding for the BRAVE-AA trial program. Dr. Senna reports financial relationships with Arena pharmaceuticals, Follica, and both Concert Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

from clinical trials of two drugs presented at a late-breaker research session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Based on phase 3 studies that document robust hair growth in about one third of patients, deuruxolitinib (CTP-543), an inhibitor of the JAK1 and JAK2 enzymes, has the potential to become the second JAK inhibitor available for the treatment of alopecia areata. If approved, it will join baricitinib (Olumiant), which received U.S. approval almost 1 year ago.

In his talk on THRIVE-AA2, a phase 3 trial of the investigational medicine deuruxolitinib, the principal investigator, Brett A. King, MD, PhD, displayed several before-and-after photos and said, “The photos tell the whole story. This is why there is so much excitement about these drugs.”

THRIVE-AA2 was the second of two phase 3 studies of deuruxolitinib. King was a principal investigator for both pivotal trials, called THRIVE-AA1 and THRIVE AA-2. He characterized the results of the two THRIVE trials as “comparable.”

Dr. King also was a principal investigator for the trials with baricitinib, called BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE AA-2, which were published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine. The trials for both drugs had similar designs and endpoints.

Deuruxolitinib and the THRIVE studies

In the THRIVE-AA2 trial, 517 adult patients were enrolled with moderate to severe alopecia areata, defined as a SALT (Severity of Alopecia Tool) score of ≥ 50%, which signifies a hair loss of at least 50%. Like THRIVE-AA1, patients participated at treatment centers in North America and Europe. About two-thirds were female. The mean age was 39 years. The majority of patients had complete or near complete hair loss at baseline.

“Many of these patients are the ones we have historically characterized as having alopecia totalis or universalis,” Dr. King said.

Participating patients were randomly assigned to 8 mg deuruxolitinib twice daily, 12 mg deuruxolitinib twice daily, or placebo. The primary endpoint was a SALT score of ≤ 20% at week 24.

At 24 weeks, almost no patients in the placebo group (1%) vs. 33% and 38% in the 8 mg and 12 mg twice-daily groups, respectively, met the primary endpoint. Each active treatment group was highly significant vs. placebo.

Of the responders, the majority achieved complete or near complete hair growth as defined by a SALT score of ≤ 10%, Dr. King reported.

Based on a graph that showed a relatively steep climb over the entire 24-week study period, deuruxolitinib “had a really fast onset of action,” Dr. King said. By week 8, which was the time of the first assessment, both doses of deuruxolitinib were superior to placebo.

The majority of patients had complete or significant loss of eyebrows and eye lashes at baseline, but more than two-thirds of these patients had regrowth by week 24, Dr. King said. Again, no significant regrowth was observed in the placebo arm.

On the Satisfaction of Hair Patient Reported Outcomes (SPRO), more than half of patients on both doses reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the improvement when evaluated at 24 weeks.

“The patient satisfaction overshot what one would expect by looking at the SALT scores, but a lot of subjects were at the precipice of the primary endpoint, sitting on SALT scores of 21, 25, or 30,” Dr. King said.

High participation in extension trial

More than 90% of the patients assigned to deuruxolitinib completed the trial and have entered an open-label extension (OLE). Dr. King credited the substantial rates of hair growth and the low rate of significant adverse events for the high rate of transition to OLE. Those who experienced the response were motivated to maintain it.

“This is a devastating disease. Patients want to get better,” Dr. King said.

There were no serious treatment-emergent adverse events associated with deuruxolitinib, including no thromboembolic events or other off-target events that have been reported previously with other JAK inhibitors in other disease states, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Although some adverse events, such as nasopharyngitis, were observed more often in those taking deuruxolitinib than placebo, there were “very few” discontinuations because of an adverse event, he said.

The data of THRIVE-AA2 are wholly compatible with the previously reported 706-patient THRIVE-AA1, according to Dr. King. In THRIVE-AA1, the primary endpoint of SALT ≤ 20% was reached by 29.6%, 41.5%, and 0.8% of the 8 mg, 12 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. Patient satisfaction scores, safety, and tolerability were also similar, according to Dr. King.

The experience with deuruxolitinib in the THRIVE-AA phase 3 program is similar to the experience with baricitinib in the BRAVE-AA trials. Although they cannot be compared directly because of potential differences between study populations, the 4-mg dose of baricitinib also achieved SALT score ≤ 20 in about 35% of patients, he said. The proportion was lower in the 2-mg group but was also superior to the placebo group.

“JAK inhibitors are changing the paradigm of alopecia areata,” Dr. King said. Responding to a question about payers reluctant to reimburse therapies for a “cosmetic” condition, Dr. King added that the effective treatments are “changing the landscape of how we think about this disease.” Dr. King believes these kinds of data show that “we are literally transforming lives forever.”

Baricitinib and the BRAVE studies

When baricitinib received regulatory approval for alopecia areata last year, it was not just the first JAK inhibitor approved for this disease, but the first systemic therapy of any kind, according to Maryanne Senna, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and the director of the Lahey Hair Loss Center of Excellence, Burlington, Mass. Dr. Senna was a clinical investigator of BRAVE-AA1, as well as of THRIVE-AA2.

Providing an update on the BRAVE-AA program, Dr. Senna reported 104-week data that appear to support the idea of a life-changing benefit from JAK inhibitor therapy. This is because the effects appear durable.

In the data she presented at the AAD, responders and mixed responders at 52 weeks were followed to 104 weeks. Mixed responders were defined as those without a SALT response of ≤ 20 at week 52 but who had achieved this degree of hair regrowth at some earlier point.

Of the responders, 90% maintained their response at 104 weeks. In addition, many of the mixed responders and patients with a partial response but who never achieved a SALT score ≤ 20% gained additional hair growth, including complete or near complete hair growth, when maintained on treatment over the 2 years of follow-up.

“The follow-up suggests that, if you keep patients on treatment, you can get many of them to a meaningful response,” she said.

Meanwhile, “there have been no new safety signals,” Dr. Senna said. She based this statement not only of the 104-week data but on follow-up of up to 3.6 years among patients who have remained on treatment after participating in previous studies.

According to Dr. Senna, the off-target events that have been reported previously in other diseases with other JAK inhibitors, such as major adverse cardiovascular events and thromboembolic events, have not so far been observed in the BRAVE-AA phase 3 program.

Baricitinib, much like all but one of the JAK inhibitors with dermatologic indications, carries a black box warning that lists multiple risks for drugs in this class, based on a rheumatoid arthritis study.

The Food and Drug Administration has granted deuruxolitinib Breakthrough Therapy designation for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata and Fast Track designation for the treatment of alopecia areata, according to its manufacturer Concert Pharmaceuticals.

Dr. King reports financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including Concert Pharmaceuticals, which provided the funding for the THRIVE-AA trial program, and for Eli Lilly, which provided funding for the BRAVE-AA trial program. Dr. Senna reports financial relationships with Arena pharmaceuticals, Follica, and both Concert Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AAD 2023

JAK inhibitor safety warnings drawn from rheumatologic data may be misleading in dermatology

NEW ORLEANS – , even though the basis for all the risks is a rheumatoid arthritis study, according to a critical review at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Given the fact that the postmarketing RA study was specifically enriched with high-risk patients by requiring an age at enrollment of at least 50 years and the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, the extrapolation of these risks to dermatologic indications is “not necessarily data-driven,” said Brett A. King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The recently approved deucravacitinib is the only JAK inhibitor that has so far been exempt from these warnings. Instead, based on the ORAL Surveillance study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the Food and Drug Administration requires a boxed warning in nearly identical language for all the other JAK inhibitors. Relative to tofacitinib, the JAK inhibitor tested in ORAL Surveillance, many of these drugs differ by JAK selectivity and other characteristics that are likely relevant to risk of adverse events, Dr. King said. The same language has even been applied to topical ruxolitinib cream.

Basis of boxed warnings

In ORAL Surveillance, about 4,300 high-risk patients with RA were randomized to one of two doses of tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg) twice daily or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. All patients in the trial were taking methotrexate, and almost 60% were taking concomitant corticosteroids. The average body mass index of the study population was about 30 kg/m2.

After a median 4 years of follow-up (about 5,000 patient-years), the incidence of many of the adverse events tracked in the study were higher in the tofacitinib groups, including serious infections, MACE, thromboembolic events, and cancer. Dr. King did not challenge the importance of these data, but he questioned whether they are reasonably extrapolated to dermatologic indications, particularly as many of those treated are younger than those common to an RA population.

In fact, despite a study enriched for a higher risk of many events tracked, most adverse events were only slightly elevated, Dr. King pointed out. For example, the incidence of MACE over the 4 years of follow-up was 3.4% among those taking any dose of tofacitinib versus 2.5% of those randomized to TNF inhibitor. Rates of cancer were 4.2% versus 2.9%, respectively. There were also absolute increases in the number of serious infections and thromboembolic events for tofacitinib relative to TNF inhibitor.

Dr. King acknowledged that the numbers in ORAL Surveillance associated tofacitinib with a higher risk of serious events than TNF inhibitor in patients with RA, but he believes that “JAK inhibitor safety is almost certainly not the same in dermatology as it is in rheumatology patients.”

Evidence of difference in dermatology

There is some evidence to back this up. Dr. King cited a recently published study in RMD Open that evaluated the safety profile of the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib in nearly 7,000 patients over 15,000 patient-years of follow-up. Drug safety data were evaluated with up to 5.5 years of follow-up from 12 clinical trials of the four diseases for which upadacitinib is now indicated. Three were rheumatologic (RA, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis), and the fourth was atopic dermatitis (AD). Fourteen outcomes, including numerous types of infection, MACE, hepatic complications, and malignancy, were compared with methotrexate and the TNF inhibitor adalimumab.

For the RA diseases, upadacitinib was associated with a greater risk than comparators for several outcomes, including serious infections. But in AD, there was a smaller increased risk of adverse outcomes for the JAK inhibitor relative to comparators.

When evaluated by risk of adverse events across indications, for MACE, the exposure-adjusted event rates for upadacitinib were less than 0.1 in patients treated for AD over the observation period versus 0.3 and 0.4 for RA and psoriatic arthritis, respectively. Similarly, for venous thromboembolism, the rates for upadacitinib were again less than 0.1 in patients with AD versus 0.4 and 0.2 in RA and psoriatic arthritis, respectively.

Referring back to the postmarketing study, Dr. King emphasized that it is essential to consider how the boxed warning for JAK inhibitors was generated before applying them to dermatologic indications.

“Is a 30-year-old patient with a dermatologic disorder possibly at the same risk as the patients in the study from which we got the boxed warning? The answer is simply no,” he said.

Like the tofacitinib data in the ORAL Surveillance study, the upadacitinib clinical trial data are not necessarily relevant to other JAK inhibitors. In fact, Dr. King pointed out that the safety profiles of the available JAK inhibitors are not identical, an observation that is consistent with differences in JAK inhibitor selectivity that has implications for off-target events.

Dr. King does not dismiss the potential risks outlined in the current regulatory cautions about the use of JAK inhibitors, but he believes that dermatologists should be cognizant of “where the black box warning comes from.”

“We need to think carefully about the risk-to-benefit ratio in older patients or patients with risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said. But the safety profile of JAK inhibitors “is almost certainly better” than the profile suggested in boxed warnings applied to JAK inhibitors for dermatologic indications, he advised.

Risk-benefit considerations in dermatology

This position was supported by numerous other experts when asked for their perspectives. “I fully agree,” said Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, system chair of dermatology and immunology, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York.

Like Dr. King, Dr. Guttman-Yassky did not dismiss the potential risks of JAK inhibitors when treating dermatologic diseases.

“While JAK inhibitors need monitoring as advised, adopting a boxed warning from an RA study for patients who are older [is problematic],” she commented. A study with the nonselective tofacitinib in this population “cannot be compared to more selective inhibitors in a much younger population, such as those treated [for] alopecia areata or atopic dermatitis.”

George Z. Han, MD, PhD, an associate professor of dermatology, Zucker School of Medicine, Hofstra, Northwell Medical Center, New Hyde Park, New York, also agreed but added some caveats.

“The comments about the ORAL Surveillance study are salient,” he said in an interview. “This kind of data should not directly be extrapolated to other patient types or to other medications.” However, one of Dr. Han’s most important caveats involves long-term use.

“JAK inhibitors are still relatively narrow-therapeutic-window drugs that in a dose-dependent fashion could lead to negative effects, including thromboembolic events, abnormalities in red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and lipids,” he said. While doses used in dermatology “are generally below the level of any major concern,” Dr. Han cautioned that “we lack definitive data” on long-term use, and this is important for understanding “any potential small risk of rare events, such as malignancy or thromboembolism.”

Saakshi Khattri, MD, a colleague of Dr. Guttman-Yassky at Mount Sinai, said the risks of JAK inhibitors should not be underestimated, but she also agreed that risk “needs to be delivered in the right context.” Dr. Khattri, who is board certified in both dermatology and rheumatology, noted the safety profiles of available JAK inhibitors differ and that extrapolating safety from an RA study to dermatologic indications does not make sense. “Different diseases, different age groups,” she said.

Dr. King has reported financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including companies that make JAK inhibitors. Dr. Guttman-Yassky has reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including companies that make JAK inhibitors. Dr. Han reports financial relationships with Amgen, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bond Avillion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, PellePharm, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Khattri has reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS – , even though the basis for all the risks is a rheumatoid arthritis study, according to a critical review at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Given the fact that the postmarketing RA study was specifically enriched with high-risk patients by requiring an age at enrollment of at least 50 years and the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, the extrapolation of these risks to dermatologic indications is “not necessarily data-driven,” said Brett A. King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The recently approved deucravacitinib is the only JAK inhibitor that has so far been exempt from these warnings. Instead, based on the ORAL Surveillance study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the Food and Drug Administration requires a boxed warning in nearly identical language for all the other JAK inhibitors. Relative to tofacitinib, the JAK inhibitor tested in ORAL Surveillance, many of these drugs differ by JAK selectivity and other characteristics that are likely relevant to risk of adverse events, Dr. King said. The same language has even been applied to topical ruxolitinib cream.

Basis of boxed warnings

In ORAL Surveillance, about 4,300 high-risk patients with RA were randomized to one of two doses of tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg) twice daily or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. All patients in the trial were taking methotrexate, and almost 60% were taking concomitant corticosteroids. The average body mass index of the study population was about 30 kg/m2.

After a median 4 years of follow-up (about 5,000 patient-years), the incidence of many of the adverse events tracked in the study were higher in the tofacitinib groups, including serious infections, MACE, thromboembolic events, and cancer. Dr. King did not challenge the importance of these data, but he questioned whether they are reasonably extrapolated to dermatologic indications, particularly as many of those treated are younger than those common to an RA population.

In fact, despite a study enriched for a higher risk of many events tracked, most adverse events were only slightly elevated, Dr. King pointed out. For example, the incidence of MACE over the 4 years of follow-up was 3.4% among those taking any dose of tofacitinib versus 2.5% of those randomized to TNF inhibitor. Rates of cancer were 4.2% versus 2.9%, respectively. There were also absolute increases in the number of serious infections and thromboembolic events for tofacitinib relative to TNF inhibitor.

Dr. King acknowledged that the numbers in ORAL Surveillance associated tofacitinib with a higher risk of serious events than TNF inhibitor in patients with RA, but he believes that “JAK inhibitor safety is almost certainly not the same in dermatology as it is in rheumatology patients.”

Evidence of difference in dermatology

There is some evidence to back this up. Dr. King cited a recently published study in RMD Open that evaluated the safety profile of the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib in nearly 7,000 patients over 15,000 patient-years of follow-up. Drug safety data were evaluated with up to 5.5 years of follow-up from 12 clinical trials of the four diseases for which upadacitinib is now indicated. Three were rheumatologic (RA, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis), and the fourth was atopic dermatitis (AD). Fourteen outcomes, including numerous types of infection, MACE, hepatic complications, and malignancy, were compared with methotrexate and the TNF inhibitor adalimumab.

For the RA diseases, upadacitinib was associated with a greater risk than comparators for several outcomes, including serious infections. But in AD, there was a smaller increased risk of adverse outcomes for the JAK inhibitor relative to comparators.

When evaluated by risk of adverse events across indications, for MACE, the exposure-adjusted event rates for upadacitinib were less than 0.1 in patients treated for AD over the observation period versus 0.3 and 0.4 for RA and psoriatic arthritis, respectively. Similarly, for venous thromboembolism, the rates for upadacitinib were again less than 0.1 in patients with AD versus 0.4 and 0.2 in RA and psoriatic arthritis, respectively.

Referring back to the postmarketing study, Dr. King emphasized that it is essential to consider how the boxed warning for JAK inhibitors was generated before applying them to dermatologic indications.

“Is a 30-year-old patient with a dermatologic disorder possibly at the same risk as the patients in the study from which we got the boxed warning? The answer is simply no,” he said.

Like the tofacitinib data in the ORAL Surveillance study, the upadacitinib clinical trial data are not necessarily relevant to other JAK inhibitors. In fact, Dr. King pointed out that the safety profiles of the available JAK inhibitors are not identical, an observation that is consistent with differences in JAK inhibitor selectivity that has implications for off-target events.

Dr. King does not dismiss the potential risks outlined in the current regulatory cautions about the use of JAK inhibitors, but he believes that dermatologists should be cognizant of “where the black box warning comes from.”

“We need to think carefully about the risk-to-benefit ratio in older patients or patients with risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said. But the safety profile of JAK inhibitors “is almost certainly better” than the profile suggested in boxed warnings applied to JAK inhibitors for dermatologic indications, he advised.

Risk-benefit considerations in dermatology

This position was supported by numerous other experts when asked for their perspectives. “I fully agree,” said Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, system chair of dermatology and immunology, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York.

Like Dr. King, Dr. Guttman-Yassky did not dismiss the potential risks of JAK inhibitors when treating dermatologic diseases.

“While JAK inhibitors need monitoring as advised, adopting a boxed warning from an RA study for patients who are older [is problematic],” she commented. A study with the nonselective tofacitinib in this population “cannot be compared to more selective inhibitors in a much younger population, such as those treated [for] alopecia areata or atopic dermatitis.”

George Z. Han, MD, PhD, an associate professor of dermatology, Zucker School of Medicine, Hofstra, Northwell Medical Center, New Hyde Park, New York, also agreed but added some caveats.

“The comments about the ORAL Surveillance study are salient,” he said in an interview. “This kind of data should not directly be extrapolated to other patient types or to other medications.” However, one of Dr. Han’s most important caveats involves long-term use.

“JAK inhibitors are still relatively narrow-therapeutic-window drugs that in a dose-dependent fashion could lead to negative effects, including thromboembolic events, abnormalities in red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and lipids,” he said. While doses used in dermatology “are generally below the level of any major concern,” Dr. Han cautioned that “we lack definitive data” on long-term use, and this is important for understanding “any potential small risk of rare events, such as malignancy or thromboembolism.”

Saakshi Khattri, MD, a colleague of Dr. Guttman-Yassky at Mount Sinai, said the risks of JAK inhibitors should not be underestimated, but she also agreed that risk “needs to be delivered in the right context.” Dr. Khattri, who is board certified in both dermatology and rheumatology, noted the safety profiles of available JAK inhibitors differ and that extrapolating safety from an RA study to dermatologic indications does not make sense. “Different diseases, different age groups,” she said.

Dr. King has reported financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including companies that make JAK inhibitors. Dr. Guttman-Yassky has reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including companies that make JAK inhibitors. Dr. Han reports financial relationships with Amgen, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bond Avillion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, PellePharm, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Khattri has reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS – , even though the basis for all the risks is a rheumatoid arthritis study, according to a critical review at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Given the fact that the postmarketing RA study was specifically enriched with high-risk patients by requiring an age at enrollment of at least 50 years and the presence of at least one cardiovascular risk factor, the extrapolation of these risks to dermatologic indications is “not necessarily data-driven,” said Brett A. King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The recently approved deucravacitinib is the only JAK inhibitor that has so far been exempt from these warnings. Instead, based on the ORAL Surveillance study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the Food and Drug Administration requires a boxed warning in nearly identical language for all the other JAK inhibitors. Relative to tofacitinib, the JAK inhibitor tested in ORAL Surveillance, many of these drugs differ by JAK selectivity and other characteristics that are likely relevant to risk of adverse events, Dr. King said. The same language has even been applied to topical ruxolitinib cream.

Basis of boxed warnings

In ORAL Surveillance, about 4,300 high-risk patients with RA were randomized to one of two doses of tofacitinib (5 mg or 10 mg) twice daily or a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor. All patients in the trial were taking methotrexate, and almost 60% were taking concomitant corticosteroids. The average body mass index of the study population was about 30 kg/m2.

After a median 4 years of follow-up (about 5,000 patient-years), the incidence of many of the adverse events tracked in the study were higher in the tofacitinib groups, including serious infections, MACE, thromboembolic events, and cancer. Dr. King did not challenge the importance of these data, but he questioned whether they are reasonably extrapolated to dermatologic indications, particularly as many of those treated are younger than those common to an RA population.

In fact, despite a study enriched for a higher risk of many events tracked, most adverse events were only slightly elevated, Dr. King pointed out. For example, the incidence of MACE over the 4 years of follow-up was 3.4% among those taking any dose of tofacitinib versus 2.5% of those randomized to TNF inhibitor. Rates of cancer were 4.2% versus 2.9%, respectively. There were also absolute increases in the number of serious infections and thromboembolic events for tofacitinib relative to TNF inhibitor.

Dr. King acknowledged that the numbers in ORAL Surveillance associated tofacitinib with a higher risk of serious events than TNF inhibitor in patients with RA, but he believes that “JAK inhibitor safety is almost certainly not the same in dermatology as it is in rheumatology patients.”

Evidence of difference in dermatology

There is some evidence to back this up. Dr. King cited a recently published study in RMD Open that evaluated the safety profile of the JAK inhibitor upadacitinib in nearly 7,000 patients over 15,000 patient-years of follow-up. Drug safety data were evaluated with up to 5.5 years of follow-up from 12 clinical trials of the four diseases for which upadacitinib is now indicated. Three were rheumatologic (RA, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis), and the fourth was atopic dermatitis (AD). Fourteen outcomes, including numerous types of infection, MACE, hepatic complications, and malignancy, were compared with methotrexate and the TNF inhibitor adalimumab.

For the RA diseases, upadacitinib was associated with a greater risk than comparators for several outcomes, including serious infections. But in AD, there was a smaller increased risk of adverse outcomes for the JAK inhibitor relative to comparators.

When evaluated by risk of adverse events across indications, for MACE, the exposure-adjusted event rates for upadacitinib were less than 0.1 in patients treated for AD over the observation period versus 0.3 and 0.4 for RA and psoriatic arthritis, respectively. Similarly, for venous thromboembolism, the rates for upadacitinib were again less than 0.1 in patients with AD versus 0.4 and 0.2 in RA and psoriatic arthritis, respectively.

Referring back to the postmarketing study, Dr. King emphasized that it is essential to consider how the boxed warning for JAK inhibitors was generated before applying them to dermatologic indications.

“Is a 30-year-old patient with a dermatologic disorder possibly at the same risk as the patients in the study from which we got the boxed warning? The answer is simply no,” he said.

Like the tofacitinib data in the ORAL Surveillance study, the upadacitinib clinical trial data are not necessarily relevant to other JAK inhibitors. In fact, Dr. King pointed out that the safety profiles of the available JAK inhibitors are not identical, an observation that is consistent with differences in JAK inhibitor selectivity that has implications for off-target events.

Dr. King does not dismiss the potential risks outlined in the current regulatory cautions about the use of JAK inhibitors, but he believes that dermatologists should be cognizant of “where the black box warning comes from.”

“We need to think carefully about the risk-to-benefit ratio in older patients or patients with risk factors, such as obesity and diabetes,” he said. But the safety profile of JAK inhibitors “is almost certainly better” than the profile suggested in boxed warnings applied to JAK inhibitors for dermatologic indications, he advised.

Risk-benefit considerations in dermatology

This position was supported by numerous other experts when asked for their perspectives. “I fully agree,” said Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, system chair of dermatology and immunology, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai, New York.

Like Dr. King, Dr. Guttman-Yassky did not dismiss the potential risks of JAK inhibitors when treating dermatologic diseases.

“While JAK inhibitors need monitoring as advised, adopting a boxed warning from an RA study for patients who are older [is problematic],” she commented. A study with the nonselective tofacitinib in this population “cannot be compared to more selective inhibitors in a much younger population, such as those treated [for] alopecia areata or atopic dermatitis.”

George Z. Han, MD, PhD, an associate professor of dermatology, Zucker School of Medicine, Hofstra, Northwell Medical Center, New Hyde Park, New York, also agreed but added some caveats.

“The comments about the ORAL Surveillance study are salient,” he said in an interview. “This kind of data should not directly be extrapolated to other patient types or to other medications.” However, one of Dr. Han’s most important caveats involves long-term use.

“JAK inhibitors are still relatively narrow-therapeutic-window drugs that in a dose-dependent fashion could lead to negative effects, including thromboembolic events, abnormalities in red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and lipids,” he said. While doses used in dermatology “are generally below the level of any major concern,” Dr. Han cautioned that “we lack definitive data” on long-term use, and this is important for understanding “any potential small risk of rare events, such as malignancy or thromboembolism.”

Saakshi Khattri, MD, a colleague of Dr. Guttman-Yassky at Mount Sinai, said the risks of JAK inhibitors should not be underestimated, but she also agreed that risk “needs to be delivered in the right context.” Dr. Khattri, who is board certified in both dermatology and rheumatology, noted the safety profiles of available JAK inhibitors differ and that extrapolating safety from an RA study to dermatologic indications does not make sense. “Different diseases, different age groups,” she said.

Dr. King has reported financial relationships with more than 15 pharmaceutical companies, including companies that make JAK inhibitors. Dr. Guttman-Yassky has reported financial relationships with more than 20 pharmaceutical companies, including companies that make JAK inhibitors. Dr. Han reports financial relationships with Amgen, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bond Avillion, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, PellePharm, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Khattri has reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Arcutis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Leo, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AAD 2023

Call it preclinical or subclinical, ILD in RA needs to be tracked

More clinical guidance is needed for monitoring interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, according to a new commentary.

Though ILD is a leading cause of death among patients with RA, these patients are not routinely screened for ILD, the authors say, and there are currently no guidelines on how to monitor ILD progression in patients with RA.

“ILD associated with rheumatoid arthritis is a disease for which there’s been very little research done, so it’s an area of rheumatology where there are many unknowns,” lead author Elizabeth R. Volkmann, MD, who codirects the connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) program at University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The commentary was published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Defining disease

One of the major unknowns is how to define the disease, she said. RA patients sometimes undergo imaging for other medical reasons, and interstitial lung abnormalities are incidentally detected. These patients can be classified as having “preclinical” or “subclinical” ILD, as they do not yet have symptoms; however, there is no consensus as to what these terms mean, the commentary authors write. “The other problem that we have with these terms is that it sometimes creates the perception that this is a nonworrisome feature of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Volkmann said, although the condition should be followed closely.

“We know we can detect imaging features of ILD in people who may not yet have symptoms, and we need to know when to define a clinically important informality that requires follow-up or treatment,” added John M. Davis III, MD, a rheumatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He was not involved with the work.

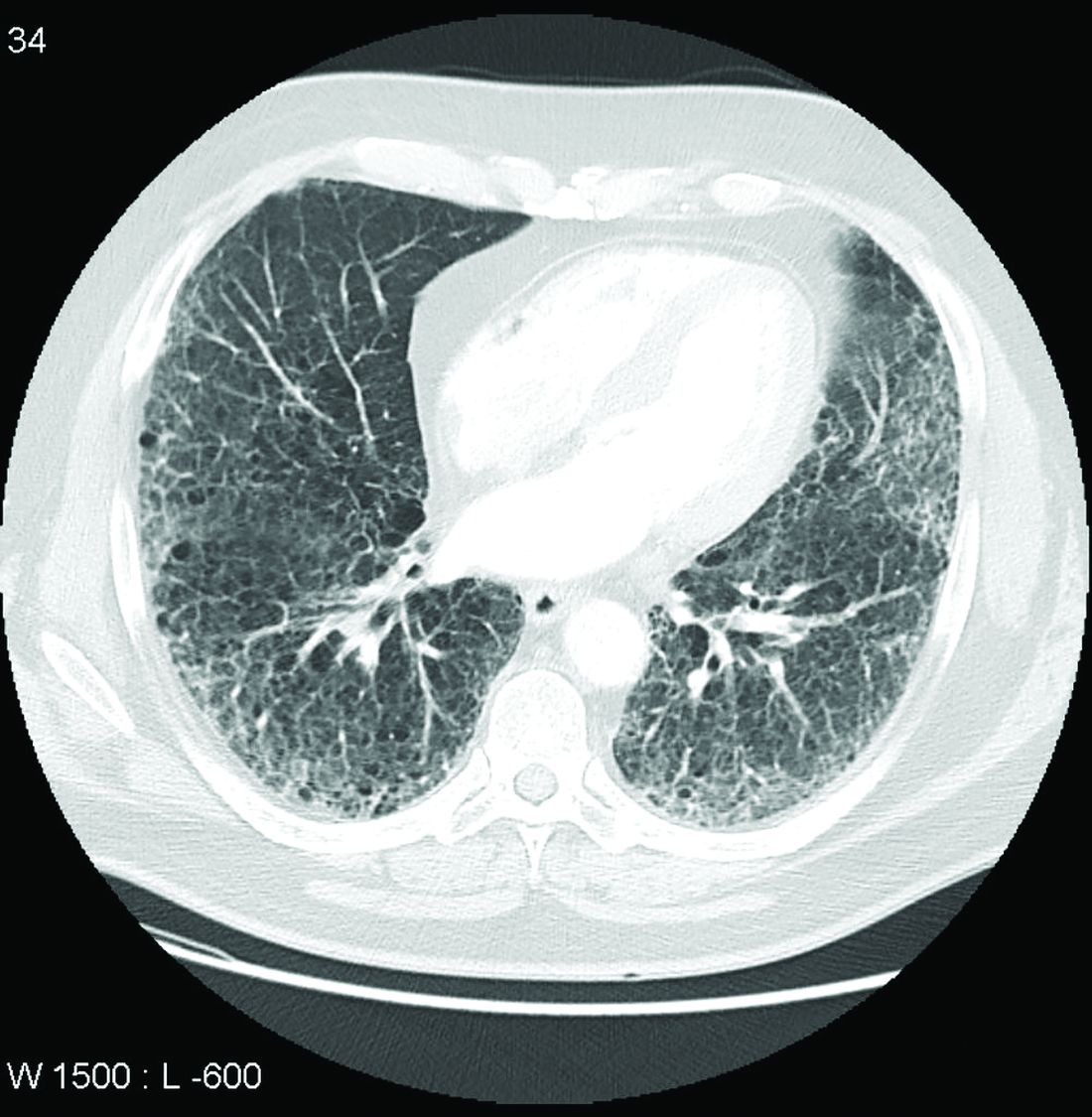

Dr. Volkmann proposed eliminating the prefixes “pre” and “sub” when referring to ILD. “In other connective tissue diseases, like systemic sclerosis, for example, we can use the term ‘limited’ or ‘extensive’ ILD, based on the extent of involvement of the ILD on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging,” she said. “This could potentially be something that is applied to how we classify patients with RA-ILD.”

Tracking ILD progression

Once ILD is identified, monitoring its progression poses challenges, as respiratory symptoms may be difficult to detect. RA patients may already be avoiding exercise because of joint pain, so they may not notice shortness of breath during physical activity, noted Jessica K. Gordon, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, in an interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the commentary. Cough is a potential symptom of ILD, but cough can also be the result of allergies, postnasal drip, or reflux, she said. Making the distinction between “preclinical” and symptomatic disease can be “complicated,” she added; “you may have to really dig.”

Additionally, there has been little research on the outcomes of patients with preclinical or subclinical ILD and clinical ILD, the commentary authors write. “It is therefore conceivable that some patients with rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed with preclinical or subclinical ILD could potentially have worse outcomes if both the rheumatoid arthritis and ILD are not monitored closely,” they note.

To better track RA-associated ILD for patients with and those without symptoms, the authors advocate for monitoring patients using pulmonary testing and CT scanning, as well as evaluating symptoms. How often these assessments should be conducted depends on the individual, they note. In her own practice, Dr. Volkmann sees patients every 3 months to evaluate their symptoms and conduct pulmonary function tests (PFTs). For patients early in the course of ILD, she orders HRCT imaging once per year.

For Dr. Davis, the frequency of follow-up depends on the severity of ILD. “For minimally symptomatic patients without compromised lung function, we would generally follow annually. For patients with symptomatic ILD on stable therapy, we may monitor every 6 months. For patients with active/progressive ILD, we would generally be following at least every 1-3 months,” he said.

Screening and future research

While there is no evidence to recommend screening patients for ILD using CT, there are certain risk factors for ILD in RA patients, including a history of smoking, male sex, and high RA disease activity despite antirheumatic treatment, Dr. Volkmann said. In both of their practices, Dr. Davis and Dr. Volkmann screen with RA via HRCT and PFTs for ILD for patients with known risk factors that predispose them to the lung condition and/or for patients who report respiratory symptoms.

“We still don’t have an algorithm [for screening patients], and that is a desperate need in this field,” added Joshua J. Solomon, MD, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health, Denver, whose research focuses on RA-associated ILD. While recommendations state that all patients with scleroderma should be screened with CT, ILD incidence is lower among patients with RA, and thus these screening recommendations need to be narrowed, he said. But more research is needed to better fine tune recommendations, he said; “The only thing you can do is give some expert consensus until there are good data.”

Dr. Volkmann has received consulting and speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and institutional support for performing studies on systemic sclerosis for Kadmon, Forbius, Boehringer Ingelheim, Horizon, and Prometheus. Dr. Gordon, Dr. Davis, and Dr. Solomon report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More clinical guidance is needed for monitoring interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, according to a new commentary.

Though ILD is a leading cause of death among patients with RA, these patients are not routinely screened for ILD, the authors say, and there are currently no guidelines on how to monitor ILD progression in patients with RA.

“ILD associated with rheumatoid arthritis is a disease for which there’s been very little research done, so it’s an area of rheumatology where there are many unknowns,” lead author Elizabeth R. Volkmann, MD, who codirects the connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) program at University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The commentary was published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Defining disease

One of the major unknowns is how to define the disease, she said. RA patients sometimes undergo imaging for other medical reasons, and interstitial lung abnormalities are incidentally detected. These patients can be classified as having “preclinical” or “subclinical” ILD, as they do not yet have symptoms; however, there is no consensus as to what these terms mean, the commentary authors write. “The other problem that we have with these terms is that it sometimes creates the perception that this is a nonworrisome feature of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Volkmann said, although the condition should be followed closely.

“We know we can detect imaging features of ILD in people who may not yet have symptoms, and we need to know when to define a clinically important informality that requires follow-up or treatment,” added John M. Davis III, MD, a rheumatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He was not involved with the work.

Dr. Volkmann proposed eliminating the prefixes “pre” and “sub” when referring to ILD. “In other connective tissue diseases, like systemic sclerosis, for example, we can use the term ‘limited’ or ‘extensive’ ILD, based on the extent of involvement of the ILD on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging,” she said. “This could potentially be something that is applied to how we classify patients with RA-ILD.”

Tracking ILD progression

Once ILD is identified, monitoring its progression poses challenges, as respiratory symptoms may be difficult to detect. RA patients may already be avoiding exercise because of joint pain, so they may not notice shortness of breath during physical activity, noted Jessica K. Gordon, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, in an interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the commentary. Cough is a potential symptom of ILD, but cough can also be the result of allergies, postnasal drip, or reflux, she said. Making the distinction between “preclinical” and symptomatic disease can be “complicated,” she added; “you may have to really dig.”

Additionally, there has been little research on the outcomes of patients with preclinical or subclinical ILD and clinical ILD, the commentary authors write. “It is therefore conceivable that some patients with rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed with preclinical or subclinical ILD could potentially have worse outcomes if both the rheumatoid arthritis and ILD are not monitored closely,” they note.

To better track RA-associated ILD for patients with and those without symptoms, the authors advocate for monitoring patients using pulmonary testing and CT scanning, as well as evaluating symptoms. How often these assessments should be conducted depends on the individual, they note. In her own practice, Dr. Volkmann sees patients every 3 months to evaluate their symptoms and conduct pulmonary function tests (PFTs). For patients early in the course of ILD, she orders HRCT imaging once per year.

For Dr. Davis, the frequency of follow-up depends on the severity of ILD. “For minimally symptomatic patients without compromised lung function, we would generally follow annually. For patients with symptomatic ILD on stable therapy, we may monitor every 6 months. For patients with active/progressive ILD, we would generally be following at least every 1-3 months,” he said.

Screening and future research

While there is no evidence to recommend screening patients for ILD using CT, there are certain risk factors for ILD in RA patients, including a history of smoking, male sex, and high RA disease activity despite antirheumatic treatment, Dr. Volkmann said. In both of their practices, Dr. Davis and Dr. Volkmann screen with RA via HRCT and PFTs for ILD for patients with known risk factors that predispose them to the lung condition and/or for patients who report respiratory symptoms.

“We still don’t have an algorithm [for screening patients], and that is a desperate need in this field,” added Joshua J. Solomon, MD, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health, Denver, whose research focuses on RA-associated ILD. While recommendations state that all patients with scleroderma should be screened with CT, ILD incidence is lower among patients with RA, and thus these screening recommendations need to be narrowed, he said. But more research is needed to better fine tune recommendations, he said; “The only thing you can do is give some expert consensus until there are good data.”

Dr. Volkmann has received consulting and speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and institutional support for performing studies on systemic sclerosis for Kadmon, Forbius, Boehringer Ingelheim, Horizon, and Prometheus. Dr. Gordon, Dr. Davis, and Dr. Solomon report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

More clinical guidance is needed for monitoring interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, according to a new commentary.

Though ILD is a leading cause of death among patients with RA, these patients are not routinely screened for ILD, the authors say, and there are currently no guidelines on how to monitor ILD progression in patients with RA.

“ILD associated with rheumatoid arthritis is a disease for which there’s been very little research done, so it’s an area of rheumatology where there are many unknowns,” lead author Elizabeth R. Volkmann, MD, who codirects the connective tissue disease–related interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) program at University of California, Los Angeles, told this news organization.

The commentary was published in The Lancet Rheumatology.

Defining disease

One of the major unknowns is how to define the disease, she said. RA patients sometimes undergo imaging for other medical reasons, and interstitial lung abnormalities are incidentally detected. These patients can be classified as having “preclinical” or “subclinical” ILD, as they do not yet have symptoms; however, there is no consensus as to what these terms mean, the commentary authors write. “The other problem that we have with these terms is that it sometimes creates the perception that this is a nonworrisome feature of rheumatoid arthritis,” Dr. Volkmann said, although the condition should be followed closely.

“We know we can detect imaging features of ILD in people who may not yet have symptoms, and we need to know when to define a clinically important informality that requires follow-up or treatment,” added John M. Davis III, MD, a rheumatologist at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He was not involved with the work.

Dr. Volkmann proposed eliminating the prefixes “pre” and “sub” when referring to ILD. “In other connective tissue diseases, like systemic sclerosis, for example, we can use the term ‘limited’ or ‘extensive’ ILD, based on the extent of involvement of the ILD on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) imaging,” she said. “This could potentially be something that is applied to how we classify patients with RA-ILD.”

Tracking ILD progression

Once ILD is identified, monitoring its progression poses challenges, as respiratory symptoms may be difficult to detect. RA patients may already be avoiding exercise because of joint pain, so they may not notice shortness of breath during physical activity, noted Jessica K. Gordon, MD, of the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, in an interview with this news organization. She was not involved with the commentary. Cough is a potential symptom of ILD, but cough can also be the result of allergies, postnasal drip, or reflux, she said. Making the distinction between “preclinical” and symptomatic disease can be “complicated,” she added; “you may have to really dig.”

Additionally, there has been little research on the outcomes of patients with preclinical or subclinical ILD and clinical ILD, the commentary authors write. “It is therefore conceivable that some patients with rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed with preclinical or subclinical ILD could potentially have worse outcomes if both the rheumatoid arthritis and ILD are not monitored closely,” they note.

To better track RA-associated ILD for patients with and those without symptoms, the authors advocate for monitoring patients using pulmonary testing and CT scanning, as well as evaluating symptoms. How often these assessments should be conducted depends on the individual, they note. In her own practice, Dr. Volkmann sees patients every 3 months to evaluate their symptoms and conduct pulmonary function tests (PFTs). For patients early in the course of ILD, she orders HRCT imaging once per year.

For Dr. Davis, the frequency of follow-up depends on the severity of ILD. “For minimally symptomatic patients without compromised lung function, we would generally follow annually. For patients with symptomatic ILD on stable therapy, we may monitor every 6 months. For patients with active/progressive ILD, we would generally be following at least every 1-3 months,” he said.

Screening and future research

While there is no evidence to recommend screening patients for ILD using CT, there are certain risk factors for ILD in RA patients, including a history of smoking, male sex, and high RA disease activity despite antirheumatic treatment, Dr. Volkmann said. In both of their practices, Dr. Davis and Dr. Volkmann screen with RA via HRCT and PFTs for ILD for patients with known risk factors that predispose them to the lung condition and/or for patients who report respiratory symptoms.

“We still don’t have an algorithm [for screening patients], and that is a desperate need in this field,” added Joshua J. Solomon, MD, a pulmonologist at National Jewish Health, Denver, whose research focuses on RA-associated ILD. While recommendations state that all patients with scleroderma should be screened with CT, ILD incidence is lower among patients with RA, and thus these screening recommendations need to be narrowed, he said. But more research is needed to better fine tune recommendations, he said; “The only thing you can do is give some expert consensus until there are good data.”

Dr. Volkmann has received consulting and speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and institutional support for performing studies on systemic sclerosis for Kadmon, Forbius, Boehringer Ingelheim, Horizon, and Prometheus. Dr. Gordon, Dr. Davis, and Dr. Solomon report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Commentary: ILD and other issues in RA treatment, March 2023

Two recent studies examined interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Albrecht and colleagues examined the prevalence of ILD in German patients with RA using a nationwide claims database from 2007 to 2020. Using diagnosis codes for seropositive and seronegative RA (along with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug prescriptions) as well as ILD, they found the prevalence of ILD to be relatively stable from 1.6% to 2.2%, and that incidence was stable (reported as 0.13%-0.21% per year, rather than per patient-year) over the course of the study. There is likely some misclassification with the primary reliance on diagnosis codes (of the included patients with RA only 44% were seropositive). They also excluded drug-induced ILD by diagnosis code, which may not be sufficient. Overall, the prevalence of ILD seems on the low end of what might be expected and may reflect a need for earlier evaluation to detect subclinical ILD.

Kronzer and colleagues performed a case-control study of 84 patients with incident RA-ILD compared with 233 patients with RA without ILD to evaluate the risk associated with specific anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) for the development of ILD. Compared with the clinical risk factors of smoking, disease activity, obesity, and glucocorticoid use, six "fine-specificity" ACPA were better able to predict ILD risk, with immunoglobulin (Ig) A2 to citrullinated histone 4 associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.08, and the others (IgA2 to citrullinated histone 2A, IgA2 to native cyclic histone 2A, IgA2 to native histone 2A, IgG to cyclic citrullinated filaggrin, and IgG to native cyclic filaggrin) were associated with OR of 2.5-5.5 for ILD. In combination with clinical characteristics, the authors developed a risk score with 93% specificity for RA-ILD that should be validated in other populations.

Suh and colleagues examined the association of RA with another less well-studied organ complication, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), using a large national insurance database. Once again, the accuracy of diagnosis is not fully clear using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), codes for classification. Overall, people with RA had a higher risk for ESRD than did people without RA, regardless of sex or smoking status. Because no immediate mechanistic connection between RA and ESRD is evident, it is possible that part of the increased risk is due to medications used in RA treatment, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Finally, a footnote to the success of the treat-to-target strategy (T2T) in RA comes in a study by Ramiro and colleagues of the RA-BIODAM cohort, which, along with other studies, has shown the success of T2T in achieving and maintaining long-term clinical remission in RA. The effect of T2T on radiographic progression, however, is less clear. In this study, over 500 patients were followed for 2 years and a comparison between the T2T strategy and radiographic damage was made. The T2T strategy consisted of intensification of treatment if the Disease Activity Score (DAS-44) did not achieve a goal of < 1.6. This was compared with the radiographic damage (based on the change in Sharp-van der Heijde score[SvdH]) over a 6-month period. Overall, the change in progression was not different among patients who were treated with a stricter adherence to T2T (ie, a higher proportion of T2T) compared with those who were not, suggesting that a looser application of T2T will not necessarily cause a worsening of radiographic progression. It is possible, given the intervals of assessment in this study, that a longer follow-up after T2T is necessary to detect progression, or, given that patients were not randomly assigned, patients who were more strictly treated with T2T were already at higher risk for radiographic progression. However, this study is also helpful in understanding how insights from controlled trials may play out in usual clinical practice.

Two recent studies examined interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Albrecht and colleagues examined the prevalence of ILD in German patients with RA using a nationwide claims database from 2007 to 2020. Using diagnosis codes for seropositive and seronegative RA (along with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug prescriptions) as well as ILD, they found the prevalence of ILD to be relatively stable from 1.6% to 2.2%, and that incidence was stable (reported as 0.13%-0.21% per year, rather than per patient-year) over the course of the study. There is likely some misclassification with the primary reliance on diagnosis codes (of the included patients with RA only 44% were seropositive). They also excluded drug-induced ILD by diagnosis code, which may not be sufficient. Overall, the prevalence of ILD seems on the low end of what might be expected and may reflect a need for earlier evaluation to detect subclinical ILD.

Kronzer and colleagues performed a case-control study of 84 patients with incident RA-ILD compared with 233 patients with RA without ILD to evaluate the risk associated with specific anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) for the development of ILD. Compared with the clinical risk factors of smoking, disease activity, obesity, and glucocorticoid use, six "fine-specificity" ACPA were better able to predict ILD risk, with immunoglobulin (Ig) A2 to citrullinated histone 4 associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.08, and the others (IgA2 to citrullinated histone 2A, IgA2 to native cyclic histone 2A, IgA2 to native histone 2A, IgG to cyclic citrullinated filaggrin, and IgG to native cyclic filaggrin) were associated with OR of 2.5-5.5 for ILD. In combination with clinical characteristics, the authors developed a risk score with 93% specificity for RA-ILD that should be validated in other populations.

Suh and colleagues examined the association of RA with another less well-studied organ complication, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), using a large national insurance database. Once again, the accuracy of diagnosis is not fully clear using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), codes for classification. Overall, people with RA had a higher risk for ESRD than did people without RA, regardless of sex or smoking status. Because no immediate mechanistic connection between RA and ESRD is evident, it is possible that part of the increased risk is due to medications used in RA treatment, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but this hypothesis remains to be tested.

Finally, a footnote to the success of the treat-to-target strategy (T2T) in RA comes in a study by Ramiro and colleagues of the RA-BIODAM cohort, which, along with other studies, has shown the success of T2T in achieving and maintaining long-term clinical remission in RA. The effect of T2T on radiographic progression, however, is less clear. In this study, over 500 patients were followed for 2 years and a comparison between the T2T strategy and radiographic damage was made. The T2T strategy consisted of intensification of treatment if the Disease Activity Score (DAS-44) did not achieve a goal of < 1.6. This was compared with the radiographic damage (based on the change in Sharp-van der Heijde score[SvdH]) over a 6-month period. Overall, the change in progression was not different among patients who were treated with a stricter adherence to T2T (ie, a higher proportion of T2T) compared with those who were not, suggesting that a looser application of T2T will not necessarily cause a worsening of radiographic progression. It is possible, given the intervals of assessment in this study, that a longer follow-up after T2T is necessary to detect progression, or, given that patients were not randomly assigned, patients who were more strictly treated with T2T were already at higher risk for radiographic progression. However, this study is also helpful in understanding how insights from controlled trials may play out in usual clinical practice.

Two recent studies examined interstitial lung disease (ILD) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Albrecht and colleagues examined the prevalence of ILD in German patients with RA using a nationwide claims database from 2007 to 2020. Using diagnosis codes for seropositive and seronegative RA (along with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug prescriptions) as well as ILD, they found the prevalence of ILD to be relatively stable from 1.6% to 2.2%, and that incidence was stable (reported as 0.13%-0.21% per year, rather than per patient-year) over the course of the study. There is likely some misclassification with the primary reliance on diagnosis codes (of the included patients with RA only 44% were seropositive). They also excluded drug-induced ILD by diagnosis code, which may not be sufficient. Overall, the prevalence of ILD seems on the low end of what might be expected and may reflect a need for earlier evaluation to detect subclinical ILD.

Kronzer and colleagues performed a case-control study of 84 patients with incident RA-ILD compared with 233 patients with RA without ILD to evaluate the risk associated with specific anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA) for the development of ILD. Compared with the clinical risk factors of smoking, disease activity, obesity, and glucocorticoid use, six "fine-specificity" ACPA were better able to predict ILD risk, with immunoglobulin (Ig) A2 to citrullinated histone 4 associated with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.08, and the others (IgA2 to citrullinated histone 2A, IgA2 to native cyclic histone 2A, IgA2 to native histone 2A, IgG to cyclic citrullinated filaggrin, and IgG to native cyclic filaggrin) were associated with OR of 2.5-5.5 for ILD. In combination with clinical characteristics, the authors developed a risk score with 93% specificity for RA-ILD that should be validated in other populations.

Suh and colleagues examined the association of RA with another less well-studied organ complication, end-stage renal disease (ESRD), using a large national insurance database. Once again, the accuracy of diagnosis is not fully clear using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), codes for classification. Overall, people with RA had a higher risk for ESRD than did people without RA, regardless of sex or smoking status. Because no immediate mechanistic connection between RA and ESRD is evident, it is possible that part of the increased risk is due to medications used in RA treatment, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but this hypothesis remains to be tested.