User login

Rosacea: Expert recommends treating erythema, papules/pustules simultaneously

The results of a recently published trial helps answer one of the toughest questions in rosacea treatment: when patients present with both papules/pustules and erythema, which problem do you treat first?

In the past, Hilary Baldwin, MD, tended to target papules and pustules first, usually with ivermectin cream (Soolantra) and, when warranted, anti-inflammatory doses of doxycycline. Going after the erythema first and making the skin paler could make the cherry red inflammatory lesions stand out even more, she said.

In the study, one group was put on ivermectin for 12 weeks, with the vasoconstrictor brimonidine 0.33% (Mirvaso topical gel) added after 4 weeks to help with the erythema; and another group was treated with both ivermectin 1% cream and brimonidine daily for the entire 12 weeks. The third group received vehicles of both applied every day for 12 weeks (J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 1;16[9]:909-16).

“What they found was that both the combinations worked better than ivermectin alone,” and that treatment with both agents for the full 12 weeks worked best, with no increased risk of irritation or worsening of erythema than when brimonidine was brought in after 4 weeks of ivermectin, said Dr. Baldwin, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in an interview. The vasoconstriction might have somehow helped with the papules and pustules, she noted.

The lesions might have looked more prominent “for the week or two it took for the ivermectin to kick in, but the patients didn’t care. They were happier campers by virtue of treating both aspects of their rosacea at the same time,” she added.

The new kid on the block for vasoconstriction – oxymetazoline (Rhofade cream) – appears to be gentler than brimonidine. “It takes a little bit longer to reach peak effect, and the peak doesn’t give you quite as much vasoconstriction as brimonidine, which for some people is a good thing,” she said. “Perhaps they’re a little bit too white with brimonidine. For other people who are bright red, oxymetazoline might not be enough. I think there’s a place for both drugs.”

Both vasoconstrictors might actually make erythema temporarily worse; it’s a known side effect. Dr. Baldwin has her patients try them for the first time when they’re at home and don’t have any important impending social engagements, just in case. “I like to give a tube of each one and say, ‘use one on one side of your face and the other on the other side and see which makes you happier.’ ”

Some patients can get away with “a really low dose and be completely cleared,” she commented. “I have some fully controlled on 10 mg twice weekly. As long as there’s no pregnancy risk, there’s no reason you can’t do this almost indefinitely.”

This publication and the Global Academy for Medical Education are both owned by Frontline Medical News. Dr. Baldwin is a speaker and advisor for Allergan, Galderma, and Valeant; and is an investigator for Dermira, Galderma, Novan, and Valeant.

The results of a recently published trial helps answer one of the toughest questions in rosacea treatment: when patients present with both papules/pustules and erythema, which problem do you treat first?

In the past, Hilary Baldwin, MD, tended to target papules and pustules first, usually with ivermectin cream (Soolantra) and, when warranted, anti-inflammatory doses of doxycycline. Going after the erythema first and making the skin paler could make the cherry red inflammatory lesions stand out even more, she said.

In the study, one group was put on ivermectin for 12 weeks, with the vasoconstrictor brimonidine 0.33% (Mirvaso topical gel) added after 4 weeks to help with the erythema; and another group was treated with both ivermectin 1% cream and brimonidine daily for the entire 12 weeks. The third group received vehicles of both applied every day for 12 weeks (J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 1;16[9]:909-16).

“What they found was that both the combinations worked better than ivermectin alone,” and that treatment with both agents for the full 12 weeks worked best, with no increased risk of irritation or worsening of erythema than when brimonidine was brought in after 4 weeks of ivermectin, said Dr. Baldwin, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in an interview. The vasoconstriction might have somehow helped with the papules and pustules, she noted.

The lesions might have looked more prominent “for the week or two it took for the ivermectin to kick in, but the patients didn’t care. They were happier campers by virtue of treating both aspects of their rosacea at the same time,” she added.

The new kid on the block for vasoconstriction – oxymetazoline (Rhofade cream) – appears to be gentler than brimonidine. “It takes a little bit longer to reach peak effect, and the peak doesn’t give you quite as much vasoconstriction as brimonidine, which for some people is a good thing,” she said. “Perhaps they’re a little bit too white with brimonidine. For other people who are bright red, oxymetazoline might not be enough. I think there’s a place for both drugs.”

Both vasoconstrictors might actually make erythema temporarily worse; it’s a known side effect. Dr. Baldwin has her patients try them for the first time when they’re at home and don’t have any important impending social engagements, just in case. “I like to give a tube of each one and say, ‘use one on one side of your face and the other on the other side and see which makes you happier.’ ”

Some patients can get away with “a really low dose and be completely cleared,” she commented. “I have some fully controlled on 10 mg twice weekly. As long as there’s no pregnancy risk, there’s no reason you can’t do this almost indefinitely.”

This publication and the Global Academy for Medical Education are both owned by Frontline Medical News. Dr. Baldwin is a speaker and advisor for Allergan, Galderma, and Valeant; and is an investigator for Dermira, Galderma, Novan, and Valeant.

The results of a recently published trial helps answer one of the toughest questions in rosacea treatment: when patients present with both papules/pustules and erythema, which problem do you treat first?

In the past, Hilary Baldwin, MD, tended to target papules and pustules first, usually with ivermectin cream (Soolantra) and, when warranted, anti-inflammatory doses of doxycycline. Going after the erythema first and making the skin paler could make the cherry red inflammatory lesions stand out even more, she said.

In the study, one group was put on ivermectin for 12 weeks, with the vasoconstrictor brimonidine 0.33% (Mirvaso topical gel) added after 4 weeks to help with the erythema; and another group was treated with both ivermectin 1% cream and brimonidine daily for the entire 12 weeks. The third group received vehicles of both applied every day for 12 weeks (J Drugs Dermatol. 2017 Sep 1;16[9]:909-16).

“What they found was that both the combinations worked better than ivermectin alone,” and that treatment with both agents for the full 12 weeks worked best, with no increased risk of irritation or worsening of erythema than when brimonidine was brought in after 4 weeks of ivermectin, said Dr. Baldwin, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J., said in an interview. The vasoconstriction might have somehow helped with the papules and pustules, she noted.

The lesions might have looked more prominent “for the week or two it took for the ivermectin to kick in, but the patients didn’t care. They were happier campers by virtue of treating both aspects of their rosacea at the same time,” she added.

The new kid on the block for vasoconstriction – oxymetazoline (Rhofade cream) – appears to be gentler than brimonidine. “It takes a little bit longer to reach peak effect, and the peak doesn’t give you quite as much vasoconstriction as brimonidine, which for some people is a good thing,” she said. “Perhaps they’re a little bit too white with brimonidine. For other people who are bright red, oxymetazoline might not be enough. I think there’s a place for both drugs.”

Both vasoconstrictors might actually make erythema temporarily worse; it’s a known side effect. Dr. Baldwin has her patients try them for the first time when they’re at home and don’t have any important impending social engagements, just in case. “I like to give a tube of each one and say, ‘use one on one side of your face and the other on the other side and see which makes you happier.’ ”

Some patients can get away with “a really low dose and be completely cleared,” she commented. “I have some fully controlled on 10 mg twice weekly. As long as there’s no pregnancy risk, there’s no reason you can’t do this almost indefinitely.”

This publication and the Global Academy for Medical Education are both owned by Frontline Medical News. Dr. Baldwin is a speaker and advisor for Allergan, Galderma, and Valeant; and is an investigator for Dermira, Galderma, Novan, and Valeant.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE COASTAL DERMATOLOGY SYMPOSIUM

Clues to rosacea in patients of skin of color

NEW YORK – A middle-aged patient with Fitzpatrick type V skin comes to the office with a 10-year history of “breakouts” on her face. When asked about topical treatments, she reports that “everything burns or stings,” and says she just has very sensitive skin. What could this be?

Rosacea may often be missed in skin of color, said Dr. Alexis, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s reportedly rare in darker skin types, especially in blacks,” and as a result, dermatologists and patients alike have a low index of suspicion for the diagnosis, he noted.

Also, rosacea looks different on darker skin than it does on lighter skin, which is featured in much of the dermatology teaching material. “In richly pigmented [Fitzpatrick] type VI skin, the erythema of rosacea can be masked,” said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and at Mount Sinai West, both in New York.

Dermatologists, in this case, may have to do some detective work: looking at the distribution of the lesions, thinking about trigger factors from the patient history, and noting the lack of comedones – although the patient has “pimples.” Patient complaints that they are sensitive to almost all topical products and experience stinging with “everything” is another very good clue that the patient may have rosacea.

Keep rosacea on the differential for this picture, advised Dr. Alexis. In skin of color, “rosacea may not be as rare as previously thought – less common, maybe – but not rare.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – A middle-aged patient with Fitzpatrick type V skin comes to the office with a 10-year history of “breakouts” on her face. When asked about topical treatments, she reports that “everything burns or stings,” and says she just has very sensitive skin. What could this be?

Rosacea may often be missed in skin of color, said Dr. Alexis, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s reportedly rare in darker skin types, especially in blacks,” and as a result, dermatologists and patients alike have a low index of suspicion for the diagnosis, he noted.

Also, rosacea looks different on darker skin than it does on lighter skin, which is featured in much of the dermatology teaching material. “In richly pigmented [Fitzpatrick] type VI skin, the erythema of rosacea can be masked,” said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and at Mount Sinai West, both in New York.

Dermatologists, in this case, may have to do some detective work: looking at the distribution of the lesions, thinking about trigger factors from the patient history, and noting the lack of comedones – although the patient has “pimples.” Patient complaints that they are sensitive to almost all topical products and experience stinging with “everything” is another very good clue that the patient may have rosacea.

Keep rosacea on the differential for this picture, advised Dr. Alexis. In skin of color, “rosacea may not be as rare as previously thought – less common, maybe – but not rare.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – A middle-aged patient with Fitzpatrick type V skin comes to the office with a 10-year history of “breakouts” on her face. When asked about topical treatments, she reports that “everything burns or stings,” and says she just has very sensitive skin. What could this be?

Rosacea may often be missed in skin of color, said Dr. Alexis, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “It’s reportedly rare in darker skin types, especially in blacks,” and as a result, dermatologists and patients alike have a low index of suspicion for the diagnosis, he noted.

Also, rosacea looks different on darker skin than it does on lighter skin, which is featured in much of the dermatology teaching material. “In richly pigmented [Fitzpatrick] type VI skin, the erythema of rosacea can be masked,” said Dr. Alexis, chairman of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai St. Luke’s and at Mount Sinai West, both in New York.

Dermatologists, in this case, may have to do some detective work: looking at the distribution of the lesions, thinking about trigger factors from the patient history, and noting the lack of comedones – although the patient has “pimples.” Patient complaints that they are sensitive to almost all topical products and experience stinging with “everything” is another very good clue that the patient may have rosacea.

Keep rosacea on the differential for this picture, advised Dr. Alexis. In skin of color, “rosacea may not be as rare as previously thought – less common, maybe – but not rare.”

Dr. Alexis reported financial relationships with multiple pharmaceutical companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Cosmeceuticals and Alternative Therapies for Rosacea

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

What do your patients need to know?

Vascular instability associated with rosacea is exacerbated by triggers such as sunlight, hot drinks, spicy foods, stress, and rapid changing weather, which make patients flush and blush, increase the appearance of telangiectasia, and disrupt the normal skin barrier. Because the patients feel on fire, an anti-inflammatory approach is indicated. The regimen I recommend includes mild cleansers, barrier repair creams and supplements, antioxidants (topical and oral), and sun protection, all without parabens and harsh chemicals. I always recommend a product that I dispense at the office and another one of similar effectiveness that can be found over-the-counter.

What are your go-to treatments?

Cleansing is indispensable to maintain the normal flow in and out of the skin. I recommend mild cleansers without potentially sensitizing agents such as propylene glycol or parabens. It also should have calming agents (eg, fruit extracts) that remove the contaminants from the skin surface without stripping the important layers of lipids that constitute the barrier of the skin as well as ingredients (eg, prebiotics) that promote the healthy skin biome. Selenium in thermal spring water has free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties as well as protection against heavy metals.

After cleansing, I recommend a product to repair, maintain, and improve the barrier of the skin. A healthy skin barrier has an equal ratio of cholesterol, ceramides, and free fatty acids, the building blocks of the skin. In a barrier repair cream I look for ingredients that stop and prevent damaging inflammation, improve the skin's natural ability to repair and heal (eg, niacinamide), and protect against environmental insults. It should contain petrolatum and/or dimethicone to form a protective barrier on the skin to seal in moisture.

Oral niacinamide should be taken as a photoprotective agent. Oral supplementation (500 mg twice daily) is effective in reducing skin cancer. Because UV light is a trigger factor, oral photoprotection is recommended.

Topical antioxidants also are important. Free radical formation has been documented even in photoprotected skin. These free radicals have been implicated in skin cancer development and metalloproteinase production and are triggers of rosacea. As a result, I advise my patients to apply topical encapsulated vitamin C every night. The encapsulated form prevents oxidation of the product before application. In addition, I recommend oral vitamin C (1 g daily) and vitamin E (400 U daily).

For sun protection I recommend sunblocks with titanium dioxide and zinc oxide for total UVA and UVB protection. If the patient has a darker skin type, sun protection should contain iron oxide. Chemical agents can cause irritation, photocontact dermatitis, and exacerbation of rosacea symptoms. Daily application of sun protection with reapplication every 2 hours is reinforced.

What holistic therapies do you recommend?

Stress reduction activities, including yoga, relaxation, massages, and meditation, can help. Oral consumption of trigger factors is discouraged. Antioxidant green tea is recommended instead of caffeinated beverages.

Suggested Readings

Baldwin HE, Bathia ND, Friedman A, et al. The role of cutaneous microbiota harmony in maintaining functional skin barrier. J Drugs Dermatol. 2017;16:12-18.

Celerier P, Richard A, Litoux P, et al. Modulatory effects of selenium and strontium salts on keratinocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines. Arch Dermatol Res. 1995;287:680-682.

Chen AC, Martin AJ, Choy B, et al. A phase 3 randomized trial of nicotinamide for skin cancer chemoprevention. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1618-1626.

Jones D. Reactive oxygen species and rosacea. Cutis. 2004;74(suppl 3):17-20.

Lack of Significant Anti-inflammatory Activity With Clindamycin in the Treatment of Rosacea: Results of 2 Randomized, Vehicle-Controlled Trials

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by central facial erythema with or without intermittent papules and pustules (described as the inflammatory lesions of rosacea). Although twice-daily clindamycin 1% solution or gel has been used in the treatment of acne, few studies have investigated the use of clindamycin in rosacea.1,2 In one study comparing twice-daily clindamycin lotion 1% with oral tetracycline in 43 rosacea patients, clindamycin was found to be superior in the eradication of pustules.3 A combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and benzoyl peroxide 5% was found to be more effective than the vehicle in inflammatory lesions and erythema of rosacea in a 12-week randomized controlled trial; however, a definitive advantage over US Food and Drug Administration-approved topical agents used to treat papulopustular rosacea was not established.4,5 Two further studies evaluated clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel in the treatment of rosacea, but only 1 showed any effect on papulopustular lesions.6-8 The objective of the studies reported here was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clindamycin in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter (study A, 20 centers; study B, 10 centers), randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies were conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2002 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The studies were reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

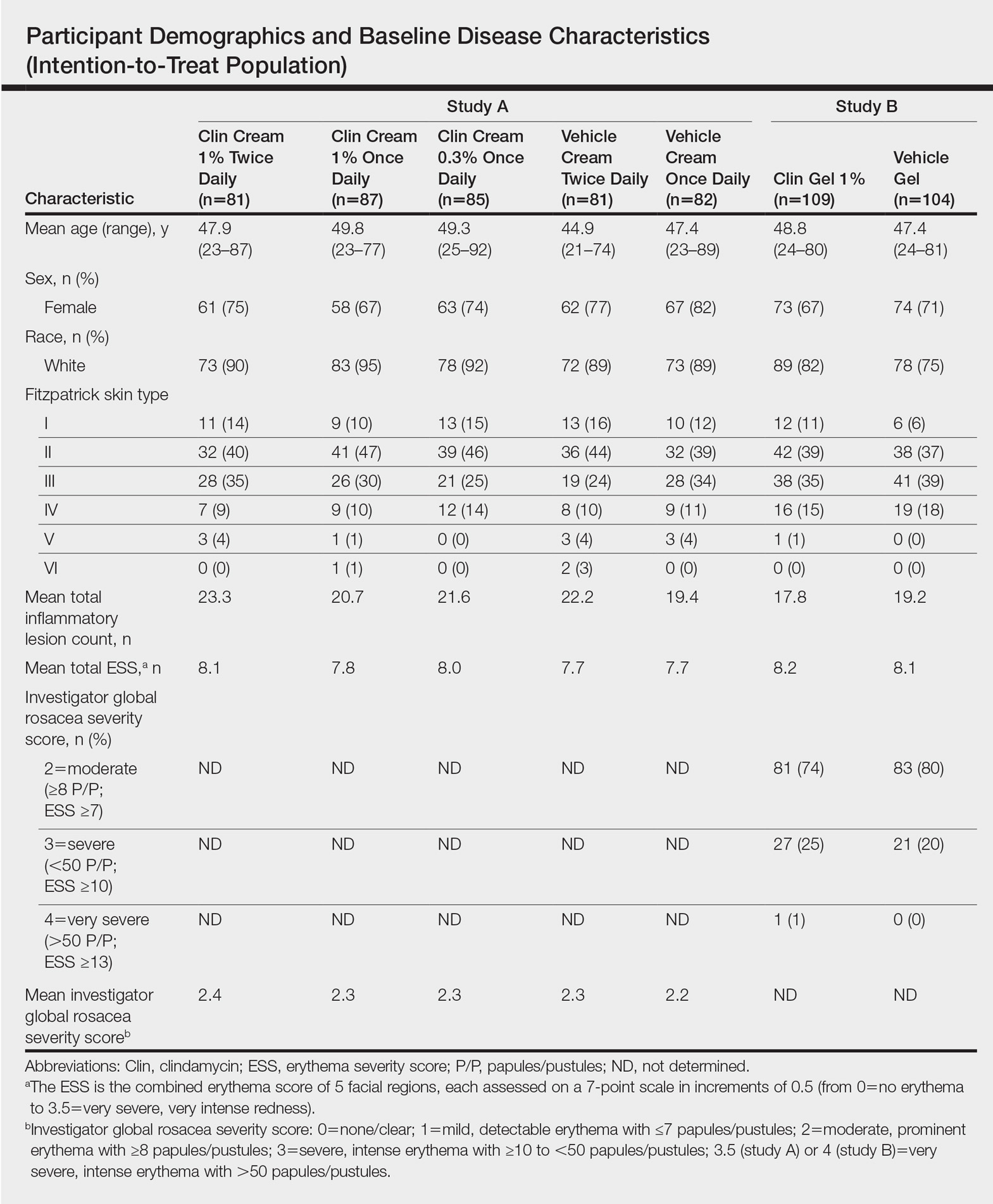

In study A, moderate to severe rosacea patients with erythema, telangiectasia, and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive clindamycin cream 1% or vehicle cream once (in the evening) or twice daily (in the morning and evening) or clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily (in the evening) for 12 weeks (1:1:1:1:1 ratio). All study treatments were supplied in identical tubes with blinded labels.

In study B, patients with moderate to severe rosacea and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized in a 1:1 ratio with instructions to apply clindamycin gel 1% or vehicle gel to the affected areas twice daily (morning and evening) for 12 weeks.

Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluations were performed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 on the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy assessments in both studies included inflammatory lesion counts (papules and pustules) of 5 facial regions--forehead, chin, nose, right cheek, left cheek--counted separately and then combined to give the total inflammatory lesion count (both studies), as well as improvement in the investigator global rosacea severity score (0=none/clear; 1=mild, detectable erythema with ≤7 papules/pustules; 2=moderate, prominent erythema with ≥8 papules/pustules; 3=severe, intense erythema with ≥10 to <50 papules/pustules; 3.5 [study A] or 4 [study B]=very severe, intense erythema with >50 papules/pustules). In study B, the proportion of participants dichotomized to success (a score of 0 [none/clear] or 1 [mild/almost clear]) or failure (a score of ≥2) on the 5-point investigator global rosacea severity scale at week 12 was evaluated. In study A, investigator global improvement assessment at week 12, based on photographs taken at baseline, was graded on a 7-point scale (from -1 [worse], 0 [no change], and 1 [minimal improvement] to 5 [clear]). In both studies, erythema severity was graded on a 7-point scale in increments of 0.5 (from 0=no erythema to 3.5=very severe redness, very intense redness). Skin irritation also was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Safety Evaluation

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analysis

Studies were powered assuming 60% reduction in inflammatory lesion counts with active and 40% with vehicle, based on historical data from a prior study with metronidazole cream 0.75% versus vehicle; 64 participants were required in each treatment group to detect this effect using a 2-sided t test (α=.017). Pairwise comparisons (clindamycin vs respective vehicle) were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for combined lesion count percentage change.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

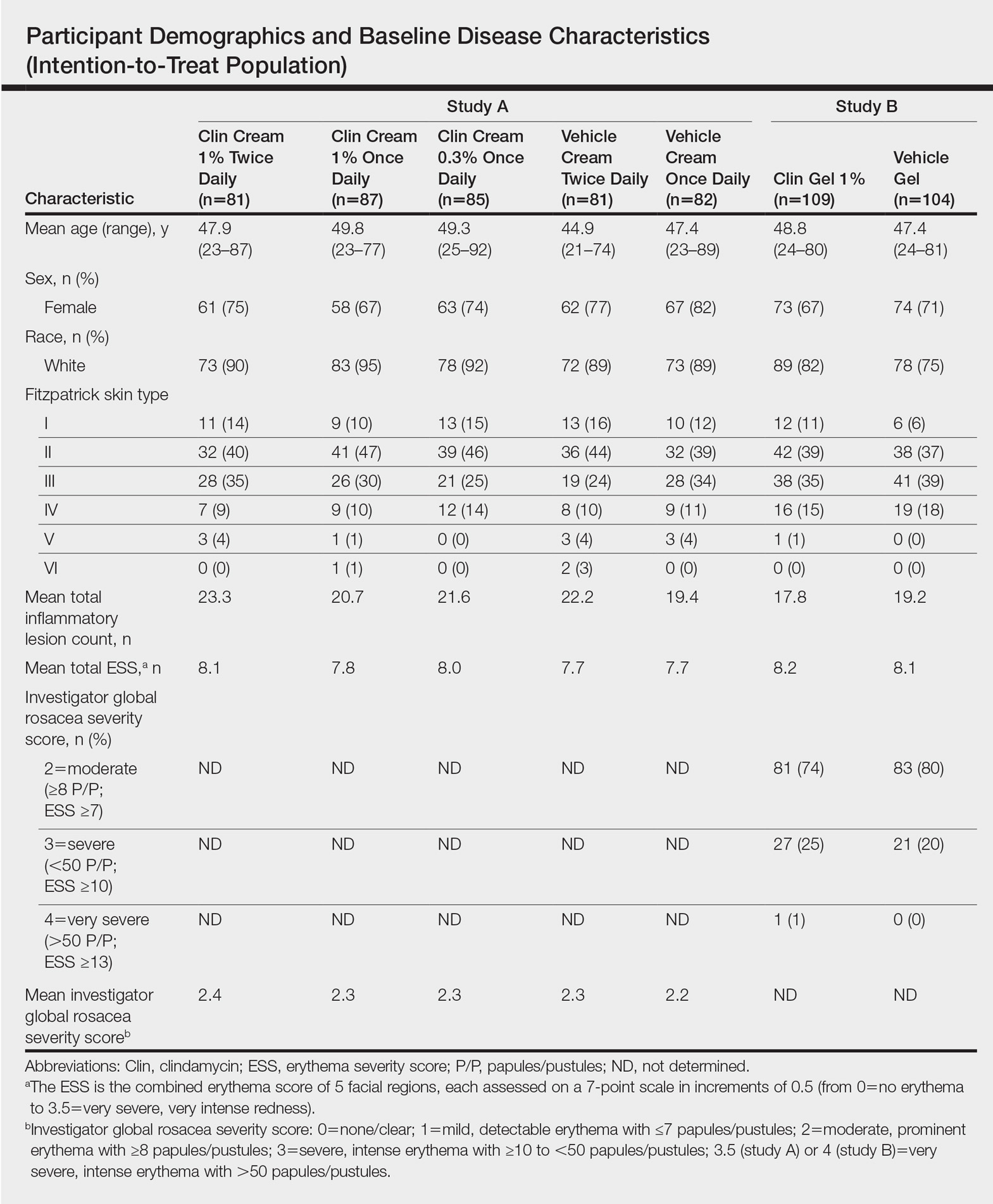

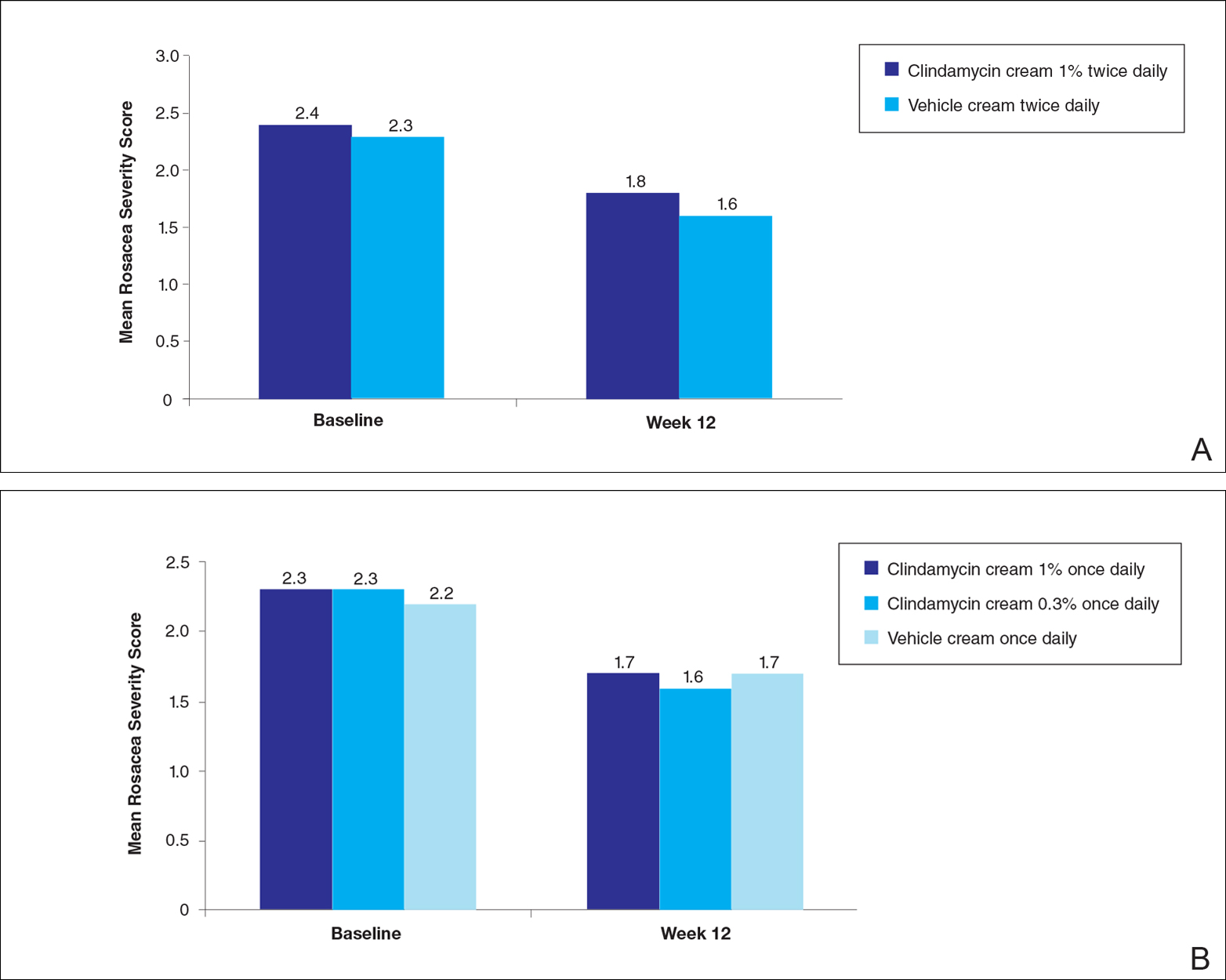

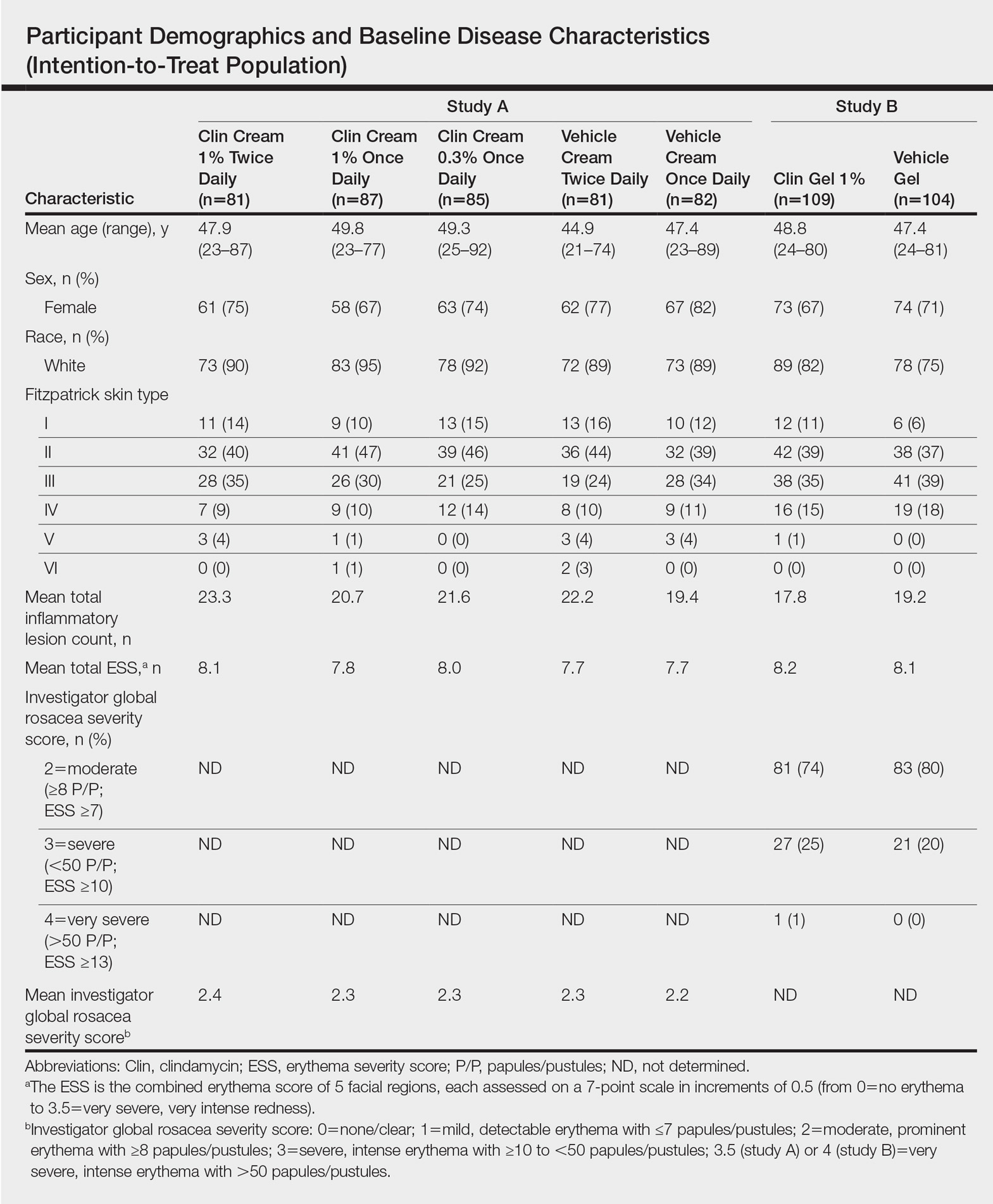

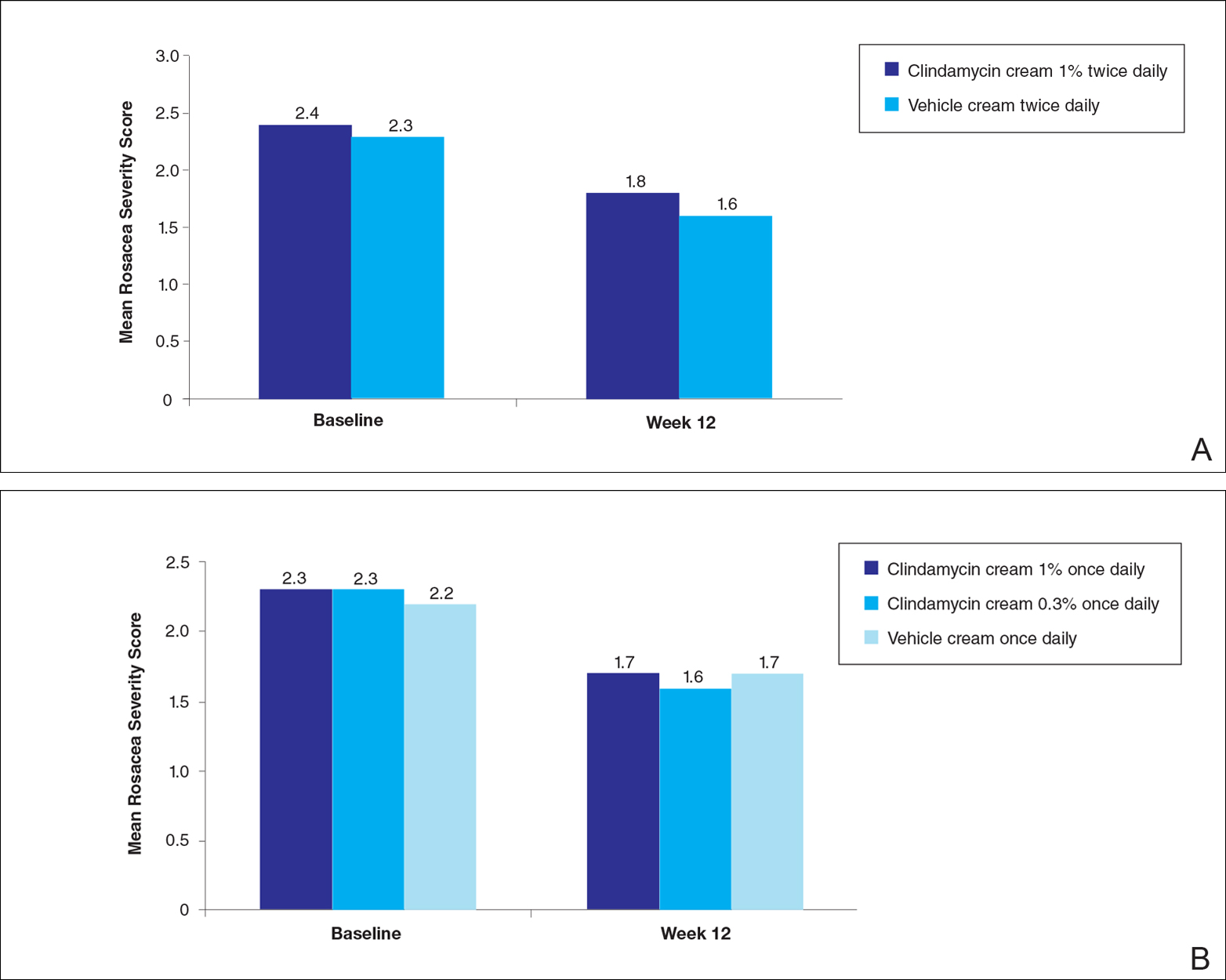

Overall, a total of 629 participants were randomized across both studies. In study A, a total of 416 participants were randomized into 5 treatment arms, with 369 participants (88.7%) completing the study; 47 (11.3%) participants discontinued study A, mainly due to participant request (19/47 [40.4%]) or lost to follow-up (11/47 [23.4%]). In study B, a total of 213 participants were randomized to receive either clindamycin gel 1% (n=109 [51.2%]) twice daily or vehicle gel (n=104 [48.8%]) twice daily, with 193 participants (90.6%) completing the study; 20 (9.4%) participants discontinued study B, mainly due to participant request (6/20 [30%]) or lost to follow-up (4/20 [20%]). Participants in studies A and B were similar in demographics and baseline disease characteristics (Table). The majority of participants were white females.

Efficacy

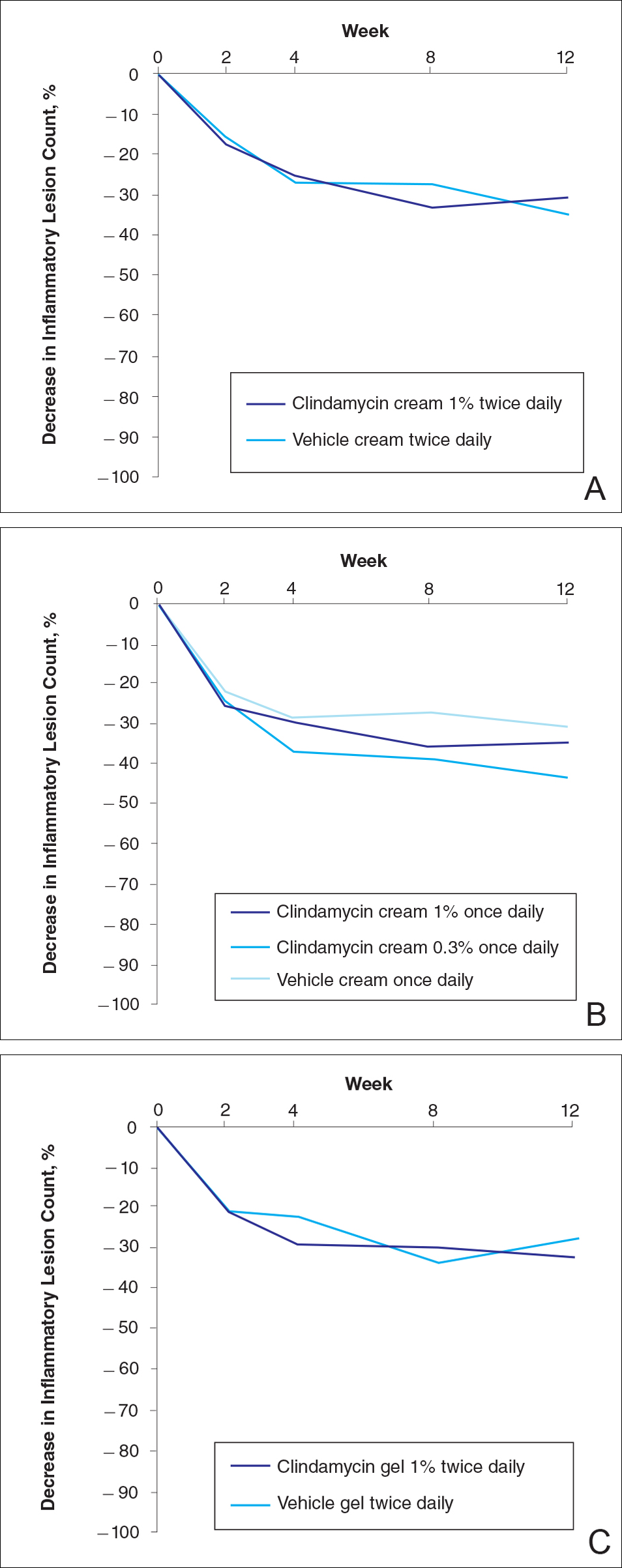

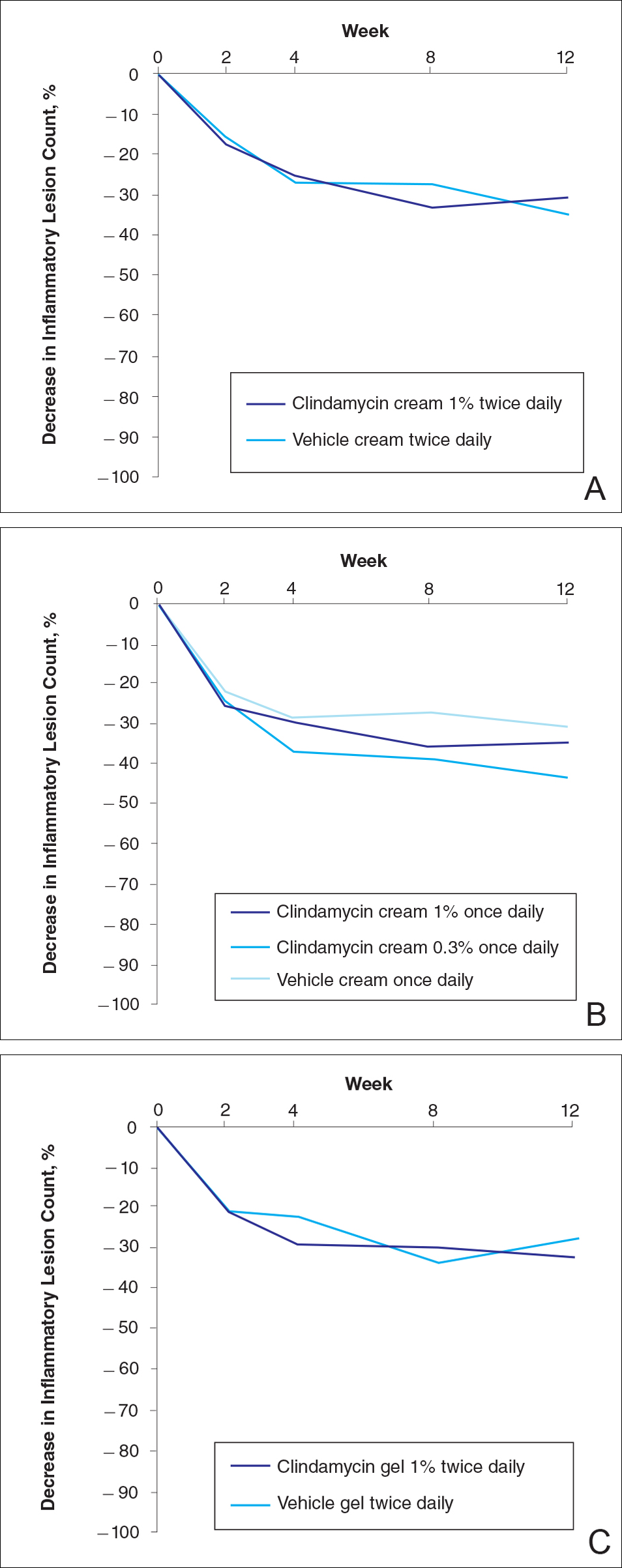

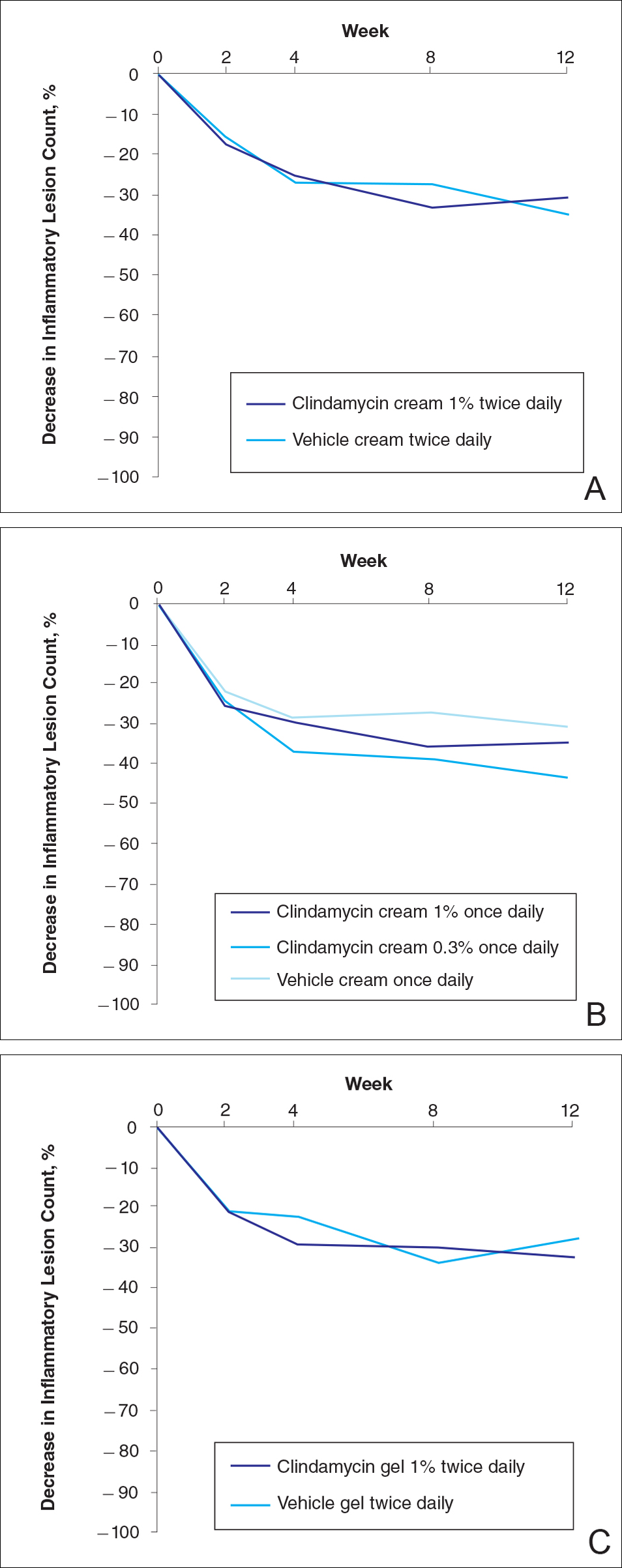

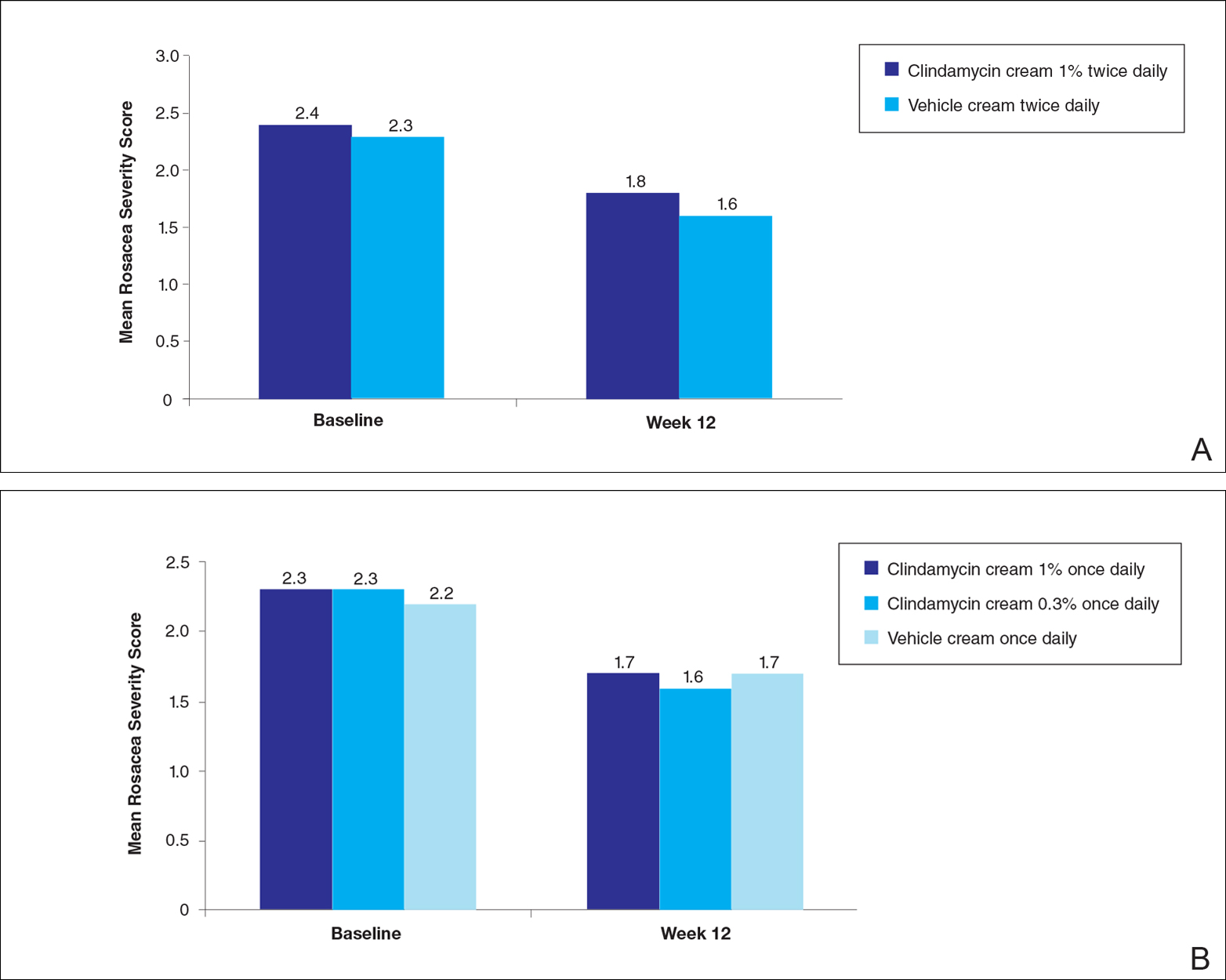

No statistically significant difference was observed in all pairwise comparisons (clindamycin cream twice daily vs vehicle twice daily, clindamycin cream once daily vs vehicle once daily, clindamycin gel vs vehicle gel) for the primary end point of mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion counts at week 12 (Figure 1; P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

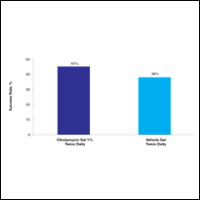

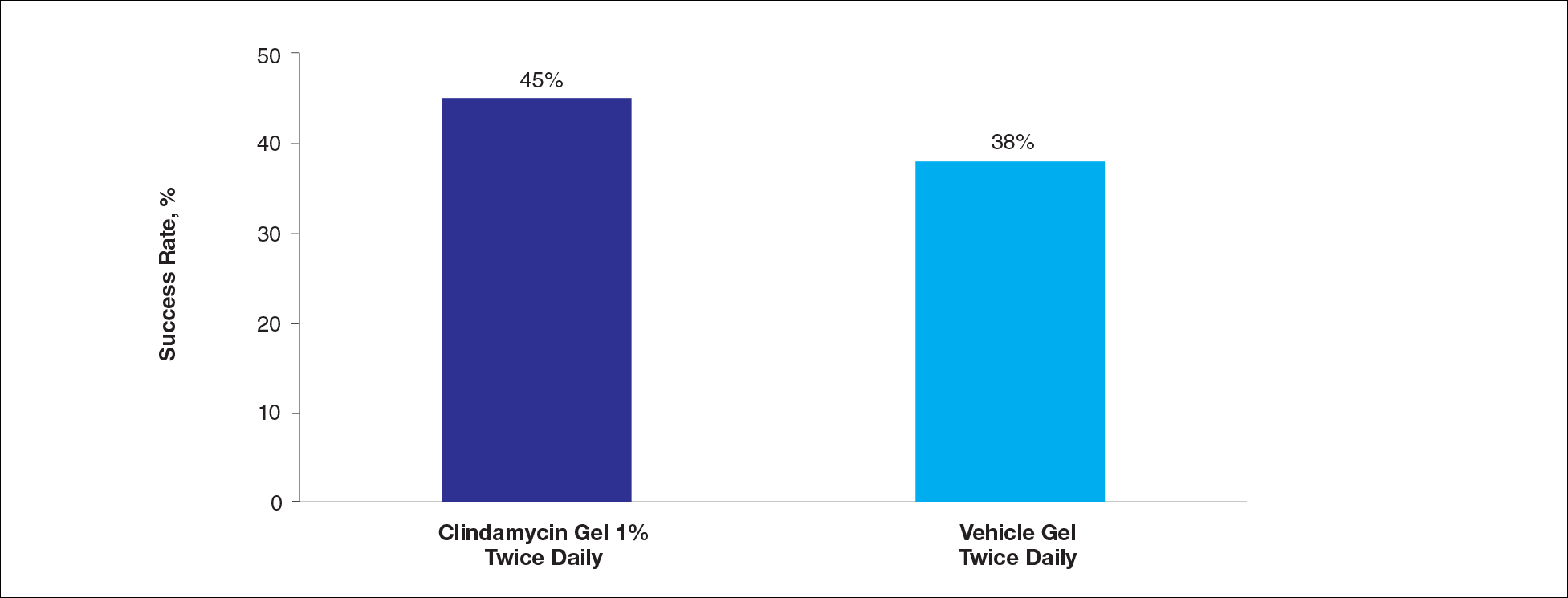

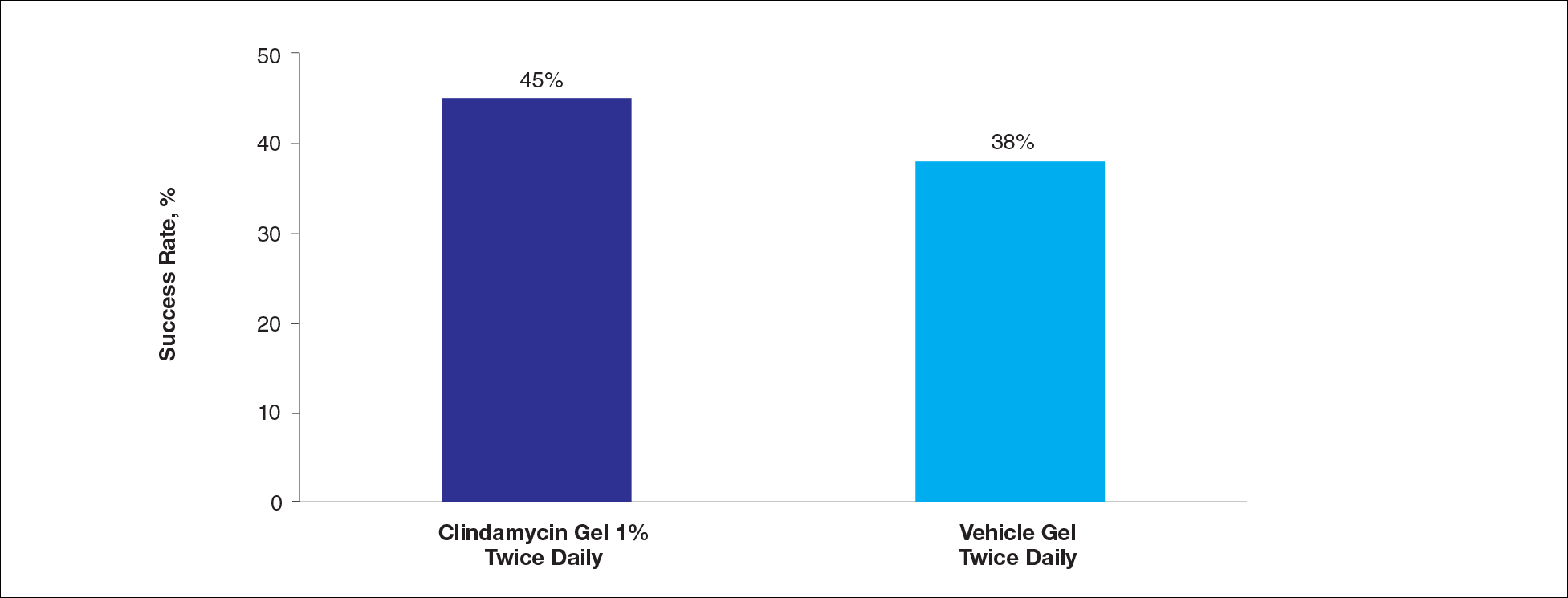

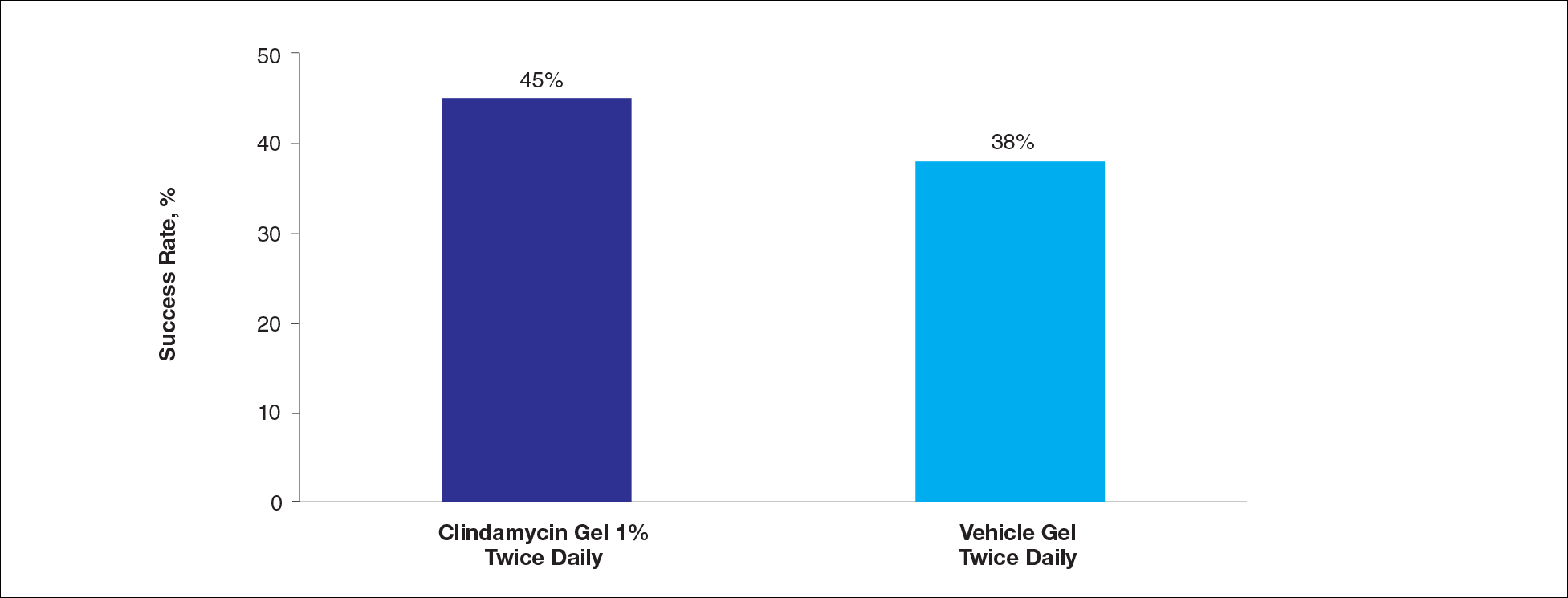

At week 12, the proportion of participants in study B deemed as a success (none/clear or mild/almost clear [investigator global rosacea severity score of 0 or 1]) in the clindamycin gel 1% and vehicle gel groups were 45% versus 38%, respectively (P=.347) (Figure 2).

For the secondary end point of mean investigator global rosacea severity assessment at week 12 (study A), there were no significant differences between the active and vehicle control groups (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons)(Figure 3). Also, the proportion of participants with at least a moderate investigator global improvement assessment from baseline to week 12 ranged from 45% for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily to 56% for clindamycin cream 0.3% cream once daily and from 45% for vehicle cream once daily to 51% for vehicle cream twice daily (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

There were no significant differences in the mean total erythema severity scores at week 12 for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily versus vehicle cream twice daily (6.3 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 1% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (6.2 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (5.9 vs 6.0; P>.5), and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily versus vehicle gel twice daily (6.7 vs 6.2; P>.5).

There were no relevant differences between any of the clindamycin cream groups and their respective vehicle group at week 12 for skin irritation, including desquamation, edema, dryness, pruritus, and stinging/burning.

Safety

In study A, the majority of AEs in all 5 treatment arms were nondermatologic, mild in intensity, and not considered to be related to the study treatment by the investigator. Overall, 12 participants had AEs considered by the investigator as possibly or probably related to the study treatment: 4.9% in the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group, 4.6% in the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group, 3.7% in the vehicle cream twice daily group, 1.2% in the clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily group, and 0% in the vehicle cream once daily group. Two treatment-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation, including dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group and contact dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group.

Comment

No evidence of increased efficacy over the respective vehicles was observed with clindamycin cream or gel, whatever the regimen, in the treatment of rosacea patients in either of these well-designed and well-powered, blinded studies. Slight improvements in the various efficacy criteria were observed, even in the vehicle groups, highlighting the importance of using a good basic skin care regimen in the management of rosacea.9 In contrast to our observations of lack of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, clinical efficacy of clindamycin has been demonstrated in acne,10-12 albeit with low efficacy for clindamycin monotherapy.13 It is noteworthy that oral or topical antibiotics are no longer recommended as monotherapy for acne to prevent and minimize antibiotic resistance and to preserve the therapeutic value of antibiotics.14

Acne and rosacea are both chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin associated with papules and pustules, and they share some common inflammatory patterns.15-19 Furthermore, the intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity of clindamycin in addition to its antibiotic effects has been suggested by some authors as the main reason for treating acne with clindamycin.20 However, the relative contributions of antibacterial and/or anti-inflammatory properties remain to be fully elucidated, and evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin remains heterogeneous.21,22 Several pathophysiological factors have been implicated in acne, including hormonal effects, abnormal keratinocyte function, increased sebum production, and microbial components (eg, hypercolonization of the skin follicles by Propionibacterium acnes).23,24 The antibiotic activity of clindamycin against P acnes may be the key factor responsible for the clinical effects in acne.25,26 Although clindamycin may have anti-inflammatory effects in acne via a different inflammatory pathway not shared by rosacea, a purely antibiotic mechanism of action of clindamycin also could explain why we observed no evidence of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, as no causative bacterial component has been clearly demonstrated in rosacea.27

Conclusion

In these studies, clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily, clindamycin cream 1% once or twice daily, and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily were all well tolerated; however, they were no more effective than the vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D (Sophia Antipolis, France), for editorial and medical writing assistance.

- Whitney KM, Ditre CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin: a review of its use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clinical Medicine Insights: Dermatology. 2011;4:27-41.

- Mays RM, Gordon RA, Wilson JM, et al. New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:23-37.

- Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

- Breneman D, Savin R, VandePol C, et al. Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial of once-daily benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:381-387.

- Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, Shalita A. Photographic review of results from a clinical study comparing benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel with vehicle in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):11-17.

- Chang AL, Alora-Palli M, Lima XT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of clindamycin 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% combination gel for the treatment of acne rosacea over 12 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:333-339.

- Freeman SA, Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for rosacea: summary of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1410-1414.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

- Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:158-162.

- Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590-595.

- Alirezaï M, Gerlach B, Horvath A, et al. Results of a randomised, multicentre study comparing a new water-based gel of clindamycin 1% versus clindamycin 1% topical solution in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:274-278.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:318-326.

- Benzaclin. Med Library website. http://medlibrary.org/lib/rx/meds/benzaclin-3. Updated May 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:E23-E33.

- Jeremy AH, Holland DB, Roberts SG, et al. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:20-27.

- Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S57-S60.

- Salzer S, Kresse S, Hirai Y, et al. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 increases UVB-triggered inflammasome activation: possible implications for rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:173-179.

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198-2208.

- Kistowska M, Meier B, Proust T, et al. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:110-118.

- Zeichner JA. Inflammatory acne treatment: review of current and new topical therapeutic options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1 suppl 1):S11-S16.

- Nakano T, Hiramatsu K, Kishi K, et al. Clindamycin modulates inflammatory-cytokine induction in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:363-367.

- Orman KL, English BK. Effects of antibiotic class on the macrophage inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1561-1565.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:323-333.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The sequence of inflammation, relevant biomarkers, and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: what does recent research show and what does it mean to the clinician? J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(8 suppl):S109-S115.

- Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. an in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263-266.

- Wang WL, Everett ED, Johnson M, et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to seventeen antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:171-173.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by central facial erythema with or without intermittent papules and pustules (described as the inflammatory lesions of rosacea). Although twice-daily clindamycin 1% solution or gel has been used in the treatment of acne, few studies have investigated the use of clindamycin in rosacea.1,2 In one study comparing twice-daily clindamycin lotion 1% with oral tetracycline in 43 rosacea patients, clindamycin was found to be superior in the eradication of pustules.3 A combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and benzoyl peroxide 5% was found to be more effective than the vehicle in inflammatory lesions and erythema of rosacea in a 12-week randomized controlled trial; however, a definitive advantage over US Food and Drug Administration-approved topical agents used to treat papulopustular rosacea was not established.4,5 Two further studies evaluated clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel in the treatment of rosacea, but only 1 showed any effect on papulopustular lesions.6-8 The objective of the studies reported here was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clindamycin in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter (study A, 20 centers; study B, 10 centers), randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies were conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2002 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The studies were reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

In study A, moderate to severe rosacea patients with erythema, telangiectasia, and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive clindamycin cream 1% or vehicle cream once (in the evening) or twice daily (in the morning and evening) or clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily (in the evening) for 12 weeks (1:1:1:1:1 ratio). All study treatments were supplied in identical tubes with blinded labels.

In study B, patients with moderate to severe rosacea and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized in a 1:1 ratio with instructions to apply clindamycin gel 1% or vehicle gel to the affected areas twice daily (morning and evening) for 12 weeks.

Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluations were performed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 on the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy assessments in both studies included inflammatory lesion counts (papules and pustules) of 5 facial regions--forehead, chin, nose, right cheek, left cheek--counted separately and then combined to give the total inflammatory lesion count (both studies), as well as improvement in the investigator global rosacea severity score (0=none/clear; 1=mild, detectable erythema with ≤7 papules/pustules; 2=moderate, prominent erythema with ≥8 papules/pustules; 3=severe, intense erythema with ≥10 to <50 papules/pustules; 3.5 [study A] or 4 [study B]=very severe, intense erythema with >50 papules/pustules). In study B, the proportion of participants dichotomized to success (a score of 0 [none/clear] or 1 [mild/almost clear]) or failure (a score of ≥2) on the 5-point investigator global rosacea severity scale at week 12 was evaluated. In study A, investigator global improvement assessment at week 12, based on photographs taken at baseline, was graded on a 7-point scale (from -1 [worse], 0 [no change], and 1 [minimal improvement] to 5 [clear]). In both studies, erythema severity was graded on a 7-point scale in increments of 0.5 (from 0=no erythema to 3.5=very severe redness, very intense redness). Skin irritation also was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Safety Evaluation

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analysis

Studies were powered assuming 60% reduction in inflammatory lesion counts with active and 40% with vehicle, based on historical data from a prior study with metronidazole cream 0.75% versus vehicle; 64 participants were required in each treatment group to detect this effect using a 2-sided t test (α=.017). Pairwise comparisons (clindamycin vs respective vehicle) were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for combined lesion count percentage change.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Overall, a total of 629 participants were randomized across both studies. In study A, a total of 416 participants were randomized into 5 treatment arms, with 369 participants (88.7%) completing the study; 47 (11.3%) participants discontinued study A, mainly due to participant request (19/47 [40.4%]) or lost to follow-up (11/47 [23.4%]). In study B, a total of 213 participants were randomized to receive either clindamycin gel 1% (n=109 [51.2%]) twice daily or vehicle gel (n=104 [48.8%]) twice daily, with 193 participants (90.6%) completing the study; 20 (9.4%) participants discontinued study B, mainly due to participant request (6/20 [30%]) or lost to follow-up (4/20 [20%]). Participants in studies A and B were similar in demographics and baseline disease characteristics (Table). The majority of participants were white females.

Efficacy

No statistically significant difference was observed in all pairwise comparisons (clindamycin cream twice daily vs vehicle twice daily, clindamycin cream once daily vs vehicle once daily, clindamycin gel vs vehicle gel) for the primary end point of mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion counts at week 12 (Figure 1; P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

At week 12, the proportion of participants in study B deemed as a success (none/clear or mild/almost clear [investigator global rosacea severity score of 0 or 1]) in the clindamycin gel 1% and vehicle gel groups were 45% versus 38%, respectively (P=.347) (Figure 2).

For the secondary end point of mean investigator global rosacea severity assessment at week 12 (study A), there were no significant differences between the active and vehicle control groups (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons)(Figure 3). Also, the proportion of participants with at least a moderate investigator global improvement assessment from baseline to week 12 ranged from 45% for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily to 56% for clindamycin cream 0.3% cream once daily and from 45% for vehicle cream once daily to 51% for vehicle cream twice daily (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

There were no significant differences in the mean total erythema severity scores at week 12 for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily versus vehicle cream twice daily (6.3 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 1% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (6.2 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (5.9 vs 6.0; P>.5), and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily versus vehicle gel twice daily (6.7 vs 6.2; P>.5).

There were no relevant differences between any of the clindamycin cream groups and their respective vehicle group at week 12 for skin irritation, including desquamation, edema, dryness, pruritus, and stinging/burning.

Safety

In study A, the majority of AEs in all 5 treatment arms were nondermatologic, mild in intensity, and not considered to be related to the study treatment by the investigator. Overall, 12 participants had AEs considered by the investigator as possibly or probably related to the study treatment: 4.9% in the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group, 4.6% in the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group, 3.7% in the vehicle cream twice daily group, 1.2% in the clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily group, and 0% in the vehicle cream once daily group. Two treatment-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation, including dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group and contact dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group.

Comment

No evidence of increased efficacy over the respective vehicles was observed with clindamycin cream or gel, whatever the regimen, in the treatment of rosacea patients in either of these well-designed and well-powered, blinded studies. Slight improvements in the various efficacy criteria were observed, even in the vehicle groups, highlighting the importance of using a good basic skin care regimen in the management of rosacea.9 In contrast to our observations of lack of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, clinical efficacy of clindamycin has been demonstrated in acne,10-12 albeit with low efficacy for clindamycin monotherapy.13 It is noteworthy that oral or topical antibiotics are no longer recommended as monotherapy for acne to prevent and minimize antibiotic resistance and to preserve the therapeutic value of antibiotics.14

Acne and rosacea are both chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin associated with papules and pustules, and they share some common inflammatory patterns.15-19 Furthermore, the intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity of clindamycin in addition to its antibiotic effects has been suggested by some authors as the main reason for treating acne with clindamycin.20 However, the relative contributions of antibacterial and/or anti-inflammatory properties remain to be fully elucidated, and evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin remains heterogeneous.21,22 Several pathophysiological factors have been implicated in acne, including hormonal effects, abnormal keratinocyte function, increased sebum production, and microbial components (eg, hypercolonization of the skin follicles by Propionibacterium acnes).23,24 The antibiotic activity of clindamycin against P acnes may be the key factor responsible for the clinical effects in acne.25,26 Although clindamycin may have anti-inflammatory effects in acne via a different inflammatory pathway not shared by rosacea, a purely antibiotic mechanism of action of clindamycin also could explain why we observed no evidence of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, as no causative bacterial component has been clearly demonstrated in rosacea.27

Conclusion

In these studies, clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily, clindamycin cream 1% once or twice daily, and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily were all well tolerated; however, they were no more effective than the vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D (Sophia Antipolis, France), for editorial and medical writing assistance.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by central facial erythema with or without intermittent papules and pustules (described as the inflammatory lesions of rosacea). Although twice-daily clindamycin 1% solution or gel has been used in the treatment of acne, few studies have investigated the use of clindamycin in rosacea.1,2 In one study comparing twice-daily clindamycin lotion 1% with oral tetracycline in 43 rosacea patients, clindamycin was found to be superior in the eradication of pustules.3 A combination therapy of clindamycin 1% and benzoyl peroxide 5% was found to be more effective than the vehicle in inflammatory lesions and erythema of rosacea in a 12-week randomized controlled trial; however, a definitive advantage over US Food and Drug Administration-approved topical agents used to treat papulopustular rosacea was not established.4,5 Two further studies evaluated clindamycin phosphate 1.2%-tretinoin 0.025% combination gel in the treatment of rosacea, but only 1 showed any effect on papulopustular lesions.6-8 The objective of the studies reported here was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of clindamycin in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea.

Methods

Study Design

Two multicenter (study A, 20 centers; study B, 10 centers), randomized, investigator-blinded, vehicle-controlled studies were conducted in the United States between 1999 and 2002 in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The studies were reviewed and approved by the respective institutional review boards, and all participants provided written informed consent.

In study A, moderate to severe rosacea patients with erythema, telangiectasia, and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized to receive clindamycin cream 1% or vehicle cream once (in the evening) or twice daily (in the morning and evening) or clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily (in the evening) for 12 weeks (1:1:1:1:1 ratio). All study treatments were supplied in identical tubes with blinded labels.

In study B, patients with moderate to severe rosacea and at least 8 inflammatory lesions were randomized in a 1:1 ratio with instructions to apply clindamycin gel 1% or vehicle gel to the affected areas twice daily (morning and evening) for 12 weeks.

Efficacy Evaluation

Evaluations were performed at baseline and weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12 on the intention-to-treat population with the last observation carried forward.

Efficacy assessments in both studies included inflammatory lesion counts (papules and pustules) of 5 facial regions--forehead, chin, nose, right cheek, left cheek--counted separately and then combined to give the total inflammatory lesion count (both studies), as well as improvement in the investigator global rosacea severity score (0=none/clear; 1=mild, detectable erythema with ≤7 papules/pustules; 2=moderate, prominent erythema with ≥8 papules/pustules; 3=severe, intense erythema with ≥10 to <50 papules/pustules; 3.5 [study A] or 4 [study B]=very severe, intense erythema with >50 papules/pustules). In study B, the proportion of participants dichotomized to success (a score of 0 [none/clear] or 1 [mild/almost clear]) or failure (a score of ≥2) on the 5-point investigator global rosacea severity scale at week 12 was evaluated. In study A, investigator global improvement assessment at week 12, based on photographs taken at baseline, was graded on a 7-point scale (from -1 [worse], 0 [no change], and 1 [minimal improvement] to 5 [clear]). In both studies, erythema severity was graded on a 7-point scale in increments of 0.5 (from 0=no erythema to 3.5=very severe redness, very intense redness). Skin irritation also was graded as none, mild, moderate, or severe.

Safety Evaluation

Safety was assessed by the incidence of adverse events (AEs).

Statistical Analysis

Studies were powered assuming 60% reduction in inflammatory lesion counts with active and 40% with vehicle, based on historical data from a prior study with metronidazole cream 0.75% versus vehicle; 64 participants were required in each treatment group to detect this effect using a 2-sided t test (α=.017). Pairwise comparisons (clindamycin vs respective vehicle) were performed using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for combined lesion count percentage change.

Results

Participant Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

Overall, a total of 629 participants were randomized across both studies. In study A, a total of 416 participants were randomized into 5 treatment arms, with 369 participants (88.7%) completing the study; 47 (11.3%) participants discontinued study A, mainly due to participant request (19/47 [40.4%]) or lost to follow-up (11/47 [23.4%]). In study B, a total of 213 participants were randomized to receive either clindamycin gel 1% (n=109 [51.2%]) twice daily or vehicle gel (n=104 [48.8%]) twice daily, with 193 participants (90.6%) completing the study; 20 (9.4%) participants discontinued study B, mainly due to participant request (6/20 [30%]) or lost to follow-up (4/20 [20%]). Participants in studies A and B were similar in demographics and baseline disease characteristics (Table). The majority of participants were white females.

Efficacy

No statistically significant difference was observed in all pairwise comparisons (clindamycin cream twice daily vs vehicle twice daily, clindamycin cream once daily vs vehicle once daily, clindamycin gel vs vehicle gel) for the primary end point of mean percentage change from baseline in inflammatory lesion counts at week 12 (Figure 1; P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

At week 12, the proportion of participants in study B deemed as a success (none/clear or mild/almost clear [investigator global rosacea severity score of 0 or 1]) in the clindamycin gel 1% and vehicle gel groups were 45% versus 38%, respectively (P=.347) (Figure 2).

For the secondary end point of mean investigator global rosacea severity assessment at week 12 (study A), there were no significant differences between the active and vehicle control groups (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons)(Figure 3). Also, the proportion of participants with at least a moderate investigator global improvement assessment from baseline to week 12 ranged from 45% for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily to 56% for clindamycin cream 0.3% cream once daily and from 45% for vehicle cream once daily to 51% for vehicle cream twice daily (P>.5 for all pairwise comparisons).

There were no significant differences in the mean total erythema severity scores at week 12 for clindamycin cream 1% twice daily versus vehicle cream twice daily (6.3 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 1% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (6.2 vs 6.0; P>.5), clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily versus vehicle cream once daily (5.9 vs 6.0; P>.5), and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily versus vehicle gel twice daily (6.7 vs 6.2; P>.5).

There were no relevant differences between any of the clindamycin cream groups and their respective vehicle group at week 12 for skin irritation, including desquamation, edema, dryness, pruritus, and stinging/burning.

Safety

In study A, the majority of AEs in all 5 treatment arms were nondermatologic, mild in intensity, and not considered to be related to the study treatment by the investigator. Overall, 12 participants had AEs considered by the investigator as possibly or probably related to the study treatment: 4.9% in the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group, 4.6% in the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group, 3.7% in the vehicle cream twice daily group, 1.2% in the clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily group, and 0% in the vehicle cream once daily group. Two treatment-related AEs led to treatment discontinuation, including dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% once daily group and contact dermatitis in 1 participant from the clindamycin cream 1% twice daily group.

Comment

No evidence of increased efficacy over the respective vehicles was observed with clindamycin cream or gel, whatever the regimen, in the treatment of rosacea patients in either of these well-designed and well-powered, blinded studies. Slight improvements in the various efficacy criteria were observed, even in the vehicle groups, highlighting the importance of using a good basic skin care regimen in the management of rosacea.9 In contrast to our observations of lack of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, clinical efficacy of clindamycin has been demonstrated in acne,10-12 albeit with low efficacy for clindamycin monotherapy.13 It is noteworthy that oral or topical antibiotics are no longer recommended as monotherapy for acne to prevent and minimize antibiotic resistance and to preserve the therapeutic value of antibiotics.14

Acne and rosacea are both chronic inflammatory disorders of the skin associated with papules and pustules, and they share some common inflammatory patterns.15-19 Furthermore, the intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity of clindamycin in addition to its antibiotic effects has been suggested by some authors as the main reason for treating acne with clindamycin.20 However, the relative contributions of antibacterial and/or anti-inflammatory properties remain to be fully elucidated, and evidence for direct anti-inflammatory effects of clindamycin remains heterogeneous.21,22 Several pathophysiological factors have been implicated in acne, including hormonal effects, abnormal keratinocyte function, increased sebum production, and microbial components (eg, hypercolonization of the skin follicles by Propionibacterium acnes).23,24 The antibiotic activity of clindamycin against P acnes may be the key factor responsible for the clinical effects in acne.25,26 Although clindamycin may have anti-inflammatory effects in acne via a different inflammatory pathway not shared by rosacea, a purely antibiotic mechanism of action of clindamycin also could explain why we observed no evidence of efficacy in the treatment of rosacea, as no causative bacterial component has been clearly demonstrated in rosacea.27

Conclusion

In these studies, clindamycin cream 0.3% once daily, clindamycin cream 1% once or twice daily, and clindamycin gel 1% twice daily were all well tolerated; however, they were no more effective than the vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Helen Simpson, PhD, of Galderma R&D (Sophia Antipolis, France), for editorial and medical writing assistance.

- Whitney KM, Ditre CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin: a review of its use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clinical Medicine Insights: Dermatology. 2011;4:27-41.

- Mays RM, Gordon RA, Wilson JM, et al. New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:23-37.

- Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

- Breneman D, Savin R, VandePol C, et al. Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial of once-daily benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:381-387.

- Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, Shalita A. Photographic review of results from a clinical study comparing benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel with vehicle in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):11-17.

- Chang AL, Alora-Palli M, Lima XT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of clindamycin 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% combination gel for the treatment of acne rosacea over 12 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:333-339.

- Freeman SA, Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for rosacea: summary of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1410-1414.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

- Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:158-162.

- Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590-595.

- Alirezaï M, Gerlach B, Horvath A, et al. Results of a randomised, multicentre study comparing a new water-based gel of clindamycin 1% versus clindamycin 1% topical solution in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:274-278.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:318-326.

- Benzaclin. Med Library website. http://medlibrary.org/lib/rx/meds/benzaclin-3. Updated May 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:E23-E33.

- Jeremy AH, Holland DB, Roberts SG, et al. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:20-27.

- Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S57-S60.

- Salzer S, Kresse S, Hirai Y, et al. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 increases UVB-triggered inflammasome activation: possible implications for rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:173-179.

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198-2208.

- Kistowska M, Meier B, Proust T, et al. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:110-118.

- Zeichner JA. Inflammatory acne treatment: review of current and new topical therapeutic options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1 suppl 1):S11-S16.

- Nakano T, Hiramatsu K, Kishi K, et al. Clindamycin modulates inflammatory-cytokine induction in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:363-367.

- Orman KL, English BK. Effects of antibiotic class on the macrophage inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1561-1565.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:323-333.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The sequence of inflammation, relevant biomarkers, and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: what does recent research show and what does it mean to the clinician? J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(8 suppl):S109-S115.

- Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. an in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263-266.

- Wang WL, Everett ED, Johnson M, et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to seventeen antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:171-173.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Whitney KM, Ditre CM. Anti-inflammatory properties of clindamycin: a review of its use in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Clinical Medicine Insights: Dermatology. 2011;4:27-41.

- Mays RM, Gordon RA, Wilson JM, et al. New antibiotic therapies for acne and rosacea. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25:23-37.

- Wilkin JK, DeWitt S. Treatment of rosacea: topical clindamycin versus oral tetracycline. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:65-67.

- Breneman D, Savin R, VandePol C, et al. Double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical trial of once-daily benzoyl peroxide/clindamycin topical gel in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:381-387.

- Leyden JJ, Thiboutot D, Shalita A. Photographic review of results from a clinical study comparing benzoyl peroxide 5%/clindamycin 1% topical gel with vehicle in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 2004;73(6 suppl):11-17.

- Chang AL, Alora-Palli M, Lima XT, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study to assess the efficacy and safety of clindamycin 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% combination gel for the treatment of acne rosacea over 12 weeks. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:333-339.

- Freeman SA, Moon SD, Spencer JM. Clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and tretinoin 0.025% gel for rosacea: summary of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1410-1414.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, et al. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

- Laquieze S, Czernielewski J, Baltas E. Beneficial use of Cetaphil moisturizing cream as part of a daily skin care regimen for individuals with rosacea. J Dermatolog Treat. 2007;18:158-162.

- Lookingbill DP, Chalker DK, Lindholm JS, et al. Treatment of acne with a combination clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide gel compared with clindamycin gel, benzoyl peroxide gel and vehicle gel: combined results of two double-blind investigations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:590-595.

- Alirezaï M, Gerlach B, Horvath A, et al. Results of a randomised, multicentre study comparing a new water-based gel of clindamycin 1% versus clindamycin 1% topical solution in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:274-278.

- Jarratt MT, Brundage T. Efficacy and safety of clindamycin-tretinoin gel versus clindamycin or tretinoin alone in acne vulgaris: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:318-326.

- Benzaclin. Med Library website. http://medlibrary.org/lib/rx/meds/benzaclin-3. Updated May 8, 2013. Accessed January 24, 2017.

- Walsh TR, Efthimiou J, Dréno B. Systematic review of antibiotic resistance in acne: an increasing topical and oral threat. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:E23-E33.

- Jeremy AH, Holland DB, Roberts SG, et al. Inflammatory events are involved in acne lesion initiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:20-27.

- Kircik LH. Re-evaluating treatment targets in acne vulgaris: adapting to a new understanding of pathophysiology. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:S57-S60.

- Salzer S, Kresse S, Hirai Y, et al. Cathelicidin peptide LL-37 increases UVB-triggered inflammasome activation: possible implications for rosacea. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:173-179.

- Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198-2208.

- Kistowska M, Meier B, Proust T, et al. Propionibacterium acnes promotes Th17 and Th17/Th1 responses in acne patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:110-118.

- Zeichner JA. Inflammatory acne treatment: review of current and new topical therapeutic options. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15(1 suppl 1):S11-S16.

- Nakano T, Hiramatsu K, Kishi K, et al. Clindamycin modulates inflammatory-cytokine induction in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse peritoneal macrophages. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:363-367.

- Orman KL, English BK. Effects of antibiotic class on the macrophage inflammatory response to Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1561-1565.

- Taylor M, Gonzalez M, Porter R. Pathways to inflammation: acne pathophysiology. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:323-333.

- Del Rosso JQ, Kircik LH. The sequence of inflammation, relevant biomarkers, and the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris: what does recent research show and what does it mean to the clinician? J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12(8 suppl):S109-S115.

- Leyden J, Kaidbey K, Levy SF. The combination formulation of clindamycin 1% plus benzoyl peroxide 5% versus 3 different formulations of topical clindamycin alone in the reduction of Propionibacterium acnes. an in vivo comparative study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:263-266.

- Wang WL, Everett ED, Johnson M, et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes to seventeen antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977;11:171-173.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

Practice Points

- Clindamycin cream 0.3% and 1% and clindamycin gel 1% were no more effective than their respective vehicles in the treatment of moderate to severe rosacea.

- Clindamycin may have no intrinsic anti-inflammatory activity in rosacea.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Redness-Reducing Products

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on redness-reducing products. Consideration must be given to:

- Avène Antirougeurs FORT Relief Concentrate

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA

“This formula has medical-grade ruscus extract to support microcirculation and soothe skin reactivity and redness, as well as soothing Avène Thermal Spring Water.” — Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

“Eucerin’s Redness Relief product line has worked well for some of my patients.” — Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Redness Solutions Daily Protective Base Broad Spectrum SPF 15

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“This oil-free makeup primer has a sheer green tint that camouflages redness while also protecting from UV rays.” — Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, cleansing devices, and men’s products will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on redness-reducing products. Consideration must be given to:

- Avène Antirougeurs FORT Relief Concentrate

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA

“This formula has medical-grade ruscus extract to support microcirculation and soothe skin reactivity and redness, as well as soothing Avène Thermal Spring Water.” — Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

“Eucerin’s Redness Relief product line has worked well for some of my patients.” — Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Redness Solutions Daily Protective Base Broad Spectrum SPF 15

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“This oil-free makeup primer has a sheer green tint that camouflages redness while also protecting from UV rays.” — Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, cleansing devices, and men’s products will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on redness-reducing products. Consideration must be given to:

- Avène Antirougeurs FORT Relief Concentrate

Pierre Fabre Dermo-Cosmetique USA

“This formula has medical-grade ruscus extract to support microcirculation and soothe skin reactivity and redness, as well as soothing Avène Thermal Spring Water.” — Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Eucerin Redness Relief

Beiersdorf Inc

“Eucerin’s Redness Relief product line has worked well for some of my patients.” — Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Redness Solutions Daily Protective Base Broad Spectrum SPF 15

Clinique Laboratories, LLC

“This oil-free makeup primer has a sheer green tint that camouflages redness while also protecting from UV rays.” — Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, New York, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, cleansing devices, and men’s products will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please email your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

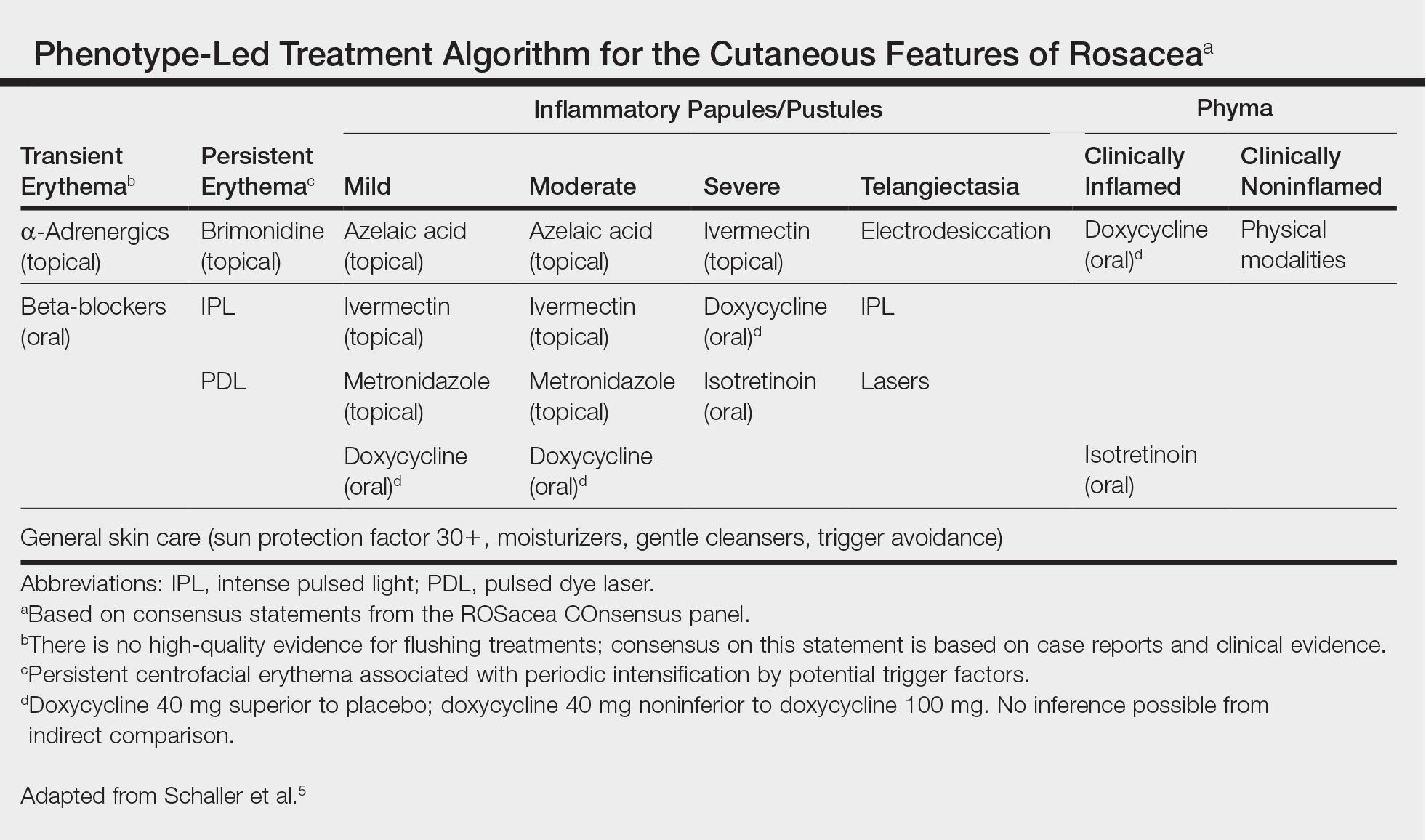

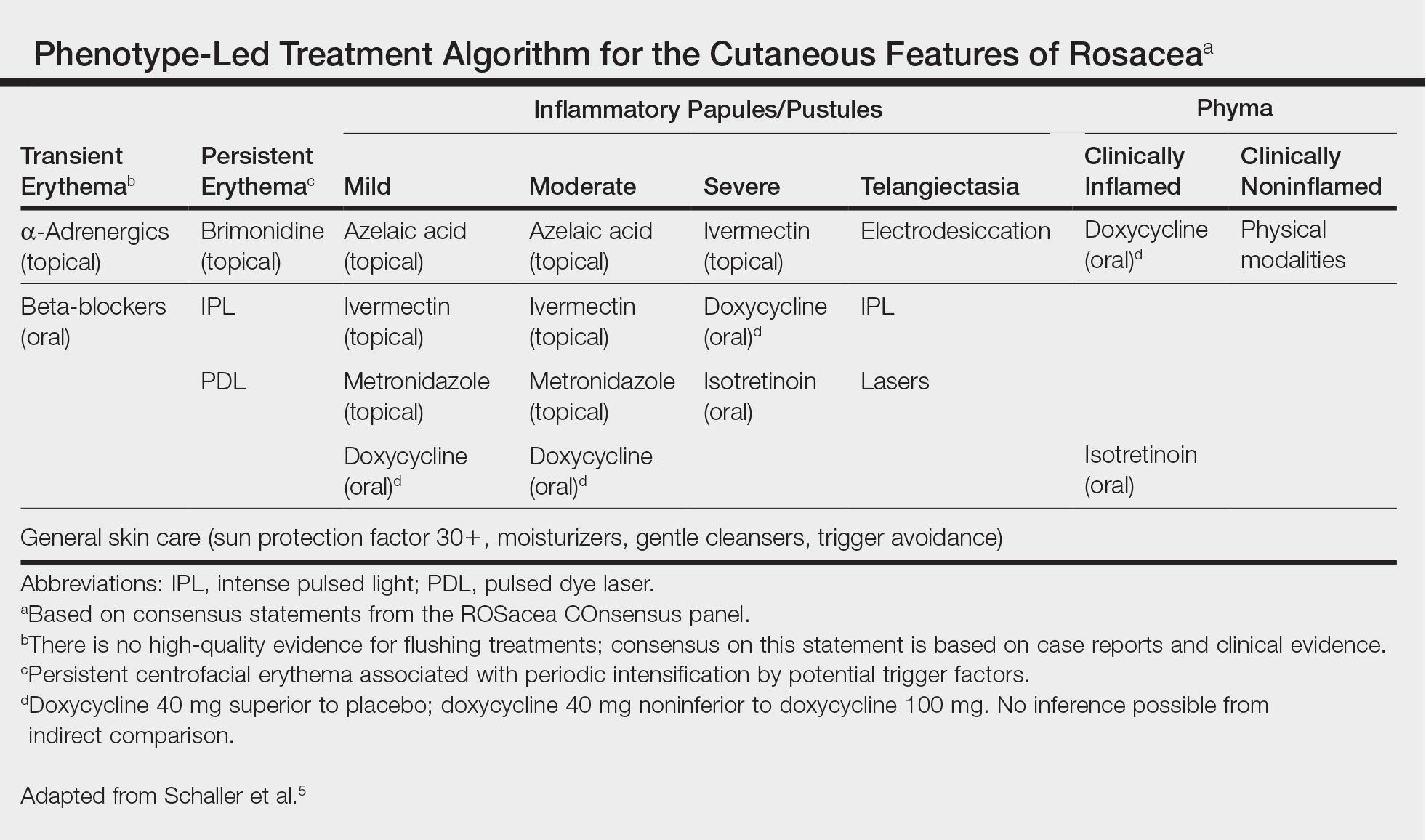

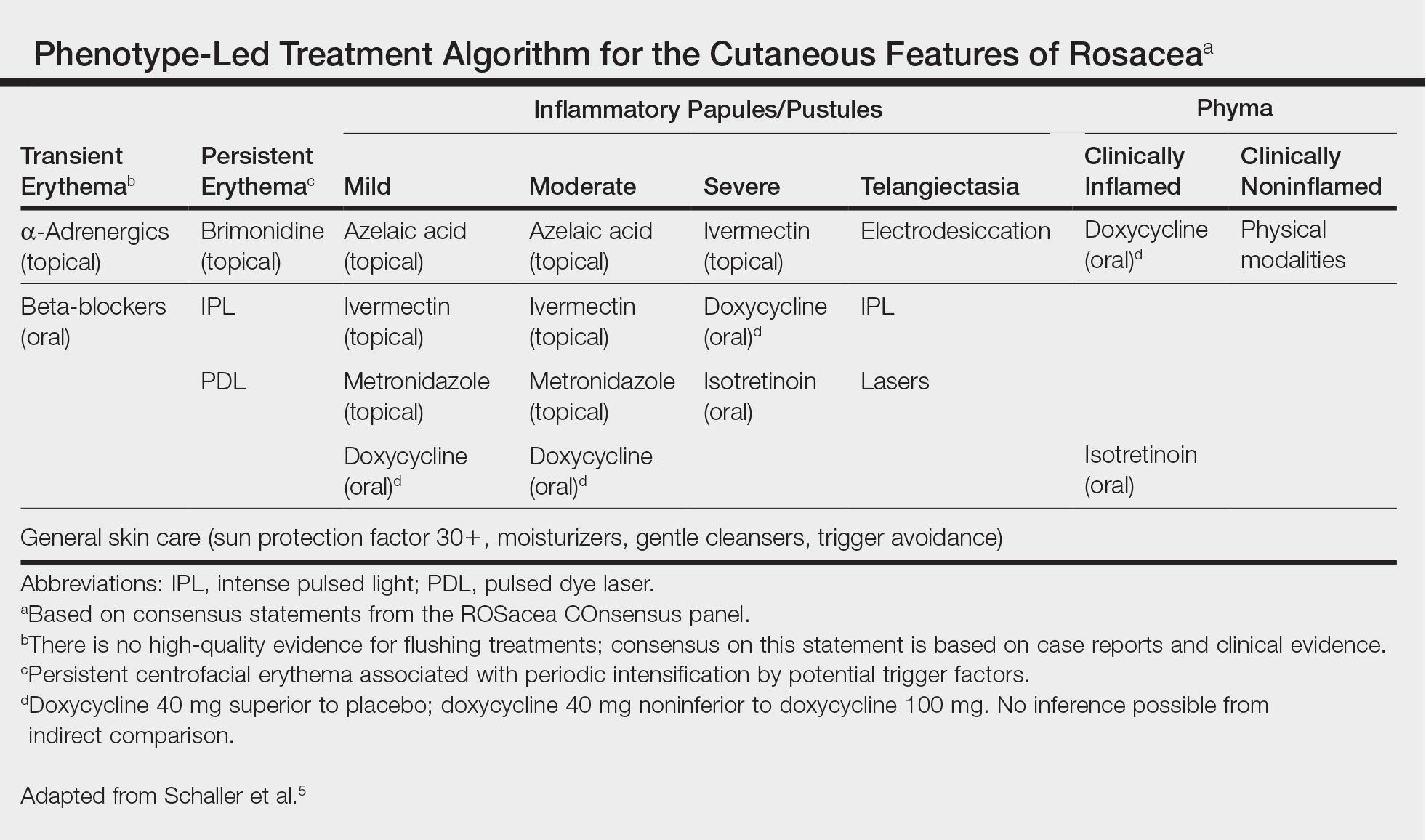

Rosacea Treatment Schema: An Update

When tasked with outlining updated therapy regimens for rosacea, specific patient vignettes come to mind.

A 53-year-old male golfer presents with years of central facial flushing, prominent telangiectases, erythema, and scattered pink papules. He attempted various over-the-counter topical products indicated for acne, such as salicylic acid scrub and benzoyl peroxide cream, with no improvement and much irritation. Recently, his wife has been helping him apply redness-concealing makeup in the morning and over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream in the evening, which has been slightly helpful.