User login

Dupilumab for Dyshidrotic Eczema With Secondary Improvement in Eosinophilic Interstitial Lung Disease

To the Editor:

Biologic medications are increasingly utilized in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that is inadequately controlled with topical medication. By targeting the IL-4 receptor alpha subunit, dupilumab inhibits the biologic effects of IL-4 and IL-13, resulting in remarkable improvement in disease and quality of life for many patients with refractory AD.1

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved dupilumab for use in AD, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis. However, there is evidence of the drug’s off-label efficacy in conditions such as eosinophilic annular erythema.2 We present a patient with dyshidrotic eczema treated with dupilumab who experienced contemporaneous secondary improvement in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) and interstitial lung disease (ILD).

A 45-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for chronic hand dermatitis refractory to increasing strengths of topical corticosteroids. He had a history of progressive shortness of breath of unknown cause, which began 2 years prior, and he was being followed at our institution’s ILD clinic. Earlier pulmonary function testing revealed a restrictive pattern with interstitial infiltrates seen on chest computed tomography. A lung biopsy demonstrated features of fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis with superimposed eosinophilic pneumonia. His pulmonary symptoms had progressively worsened; over a period of several months, the supplemental oxygen requirement had increased to 6 L at rest and 12 L upon exertion. Prednisone therapy was initiated, which alleviated respiratory symptoms; however, the patient was unable to tolerate a gradual wean of the medication, which rendered him steroid dependent at 30 mg/d.

Along with respiratory symptoms, the patient reported symptoms consistent with an autoimmune process, including dry eyes. Muscle weakness and tenderness also were noted. Ultimately, a diagnosis of anti–PL-7 (anti-threonyl-transfer RNA synthetase) antisynthetase syndrome was rendered by identification of anti–PL-7 antibodies and an elevated level of creatinine kinase.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed subtle palmar scaling on the hands and multiple small clear vesicles on the lateral aspects of the digits (Figure, A), consistent with dyshidrotic eczema. He initially was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%. Despite adherence to this high-potency topical corticosteroid, he experienced only minimal improvement over a period of 3 months. Dupilumab was started at standard dosing—600 mg at initiation, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. The patient reported rapid improvement in dyshidrotic eczema over several months with near-complete resolution (Figure, B).

Concurrent with initiation and continued use of dupilumab, without other changes in his medication regimen, the patient noted gradual improvement in respiratory symptoms. At 6-month follow-up he reported notable improvement in respiratory function and quality of life. He then tolerated a gradual wean of prednisone to 10 mg/d, with a similar reduction in supplemental oxygen.

Off-label use of dupilumab for various eosinophilic conditions has shown promising efficacy. Our patient experienced improvement in CEP shortly after initiation of dupilumab, enabling weaning of prednisone, which has a well established adverse effect profile associated with long term use.3,4 In comparison, dupilumab generally is well tolerated, with rare ophthalmologic complications and injection-site reactions.5

One case report suggested that CEP may represent a potential rare adverse effect of dupilumab initiation.6 However, prior to initiation of dupilumab, that patient had poorly controlled asthma requiring frequent oral corticosteroid therapy. It is possible that CEP was subclinical prior to initiation of dupilumab and became more noticeable once the patient was weaned from corticosteroids, which had served as an indirect treatment.6 Nonetheless, more research is needed to definitively establish the efficacy of dupilumab in CEP prior to more widespread use.

Irrespective of the potential efficacy of dupilumab for the treatment of CEP, our case highlights the growing body of evidence that dupilumab should be considered in the treatment of dyshidrotic eczema, particularly in cases refractory to topical treatment.7 When a systemic medication is preferred, dupilumab likely represents an option with a relatively well-tolerated adverse effect profile compared to traditional systemic treatments for dyshidrotic eczema.

1. Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, Silverberg JI, et al. Dupilumab provides rapid and sustained improvement in SCORAD outcomes in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: combined results ofour randomized phase 3 trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:266-277. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1750550

2. Gordon SC, Robinson SN, Abudu M, et al. Eosinophilic annular erythema treated with dupilumab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E255-E256. doi:10.1111/pde.13533

3. Callaghan DJ 3rd. Use of Google Trends to examine interest in Mohs micrographic surgery: 2004 to 2016. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:186-192. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001270

4. Fowler C, Hoover W. Dupilumab for chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:3229-3230. doi:10.1002/ppul.25096

5. Simpson EL, Akinlade B, Ardeleanu M. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1090-1091. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1700366

6. Menzella F, Montanari G, Patricelli G, et al. A case of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia in a patient treated with dupilumab. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:869-875. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S207402

7. Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan B, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of dyshidrotic eczema in 15 consecutive patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1251-1252. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.053

To the Editor:

Biologic medications are increasingly utilized in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that is inadequately controlled with topical medication. By targeting the IL-4 receptor alpha subunit, dupilumab inhibits the biologic effects of IL-4 and IL-13, resulting in remarkable improvement in disease and quality of life for many patients with refractory AD.1

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved dupilumab for use in AD, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis. However, there is evidence of the drug’s off-label efficacy in conditions such as eosinophilic annular erythema.2 We present a patient with dyshidrotic eczema treated with dupilumab who experienced contemporaneous secondary improvement in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) and interstitial lung disease (ILD).

A 45-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for chronic hand dermatitis refractory to increasing strengths of topical corticosteroids. He had a history of progressive shortness of breath of unknown cause, which began 2 years prior, and he was being followed at our institution’s ILD clinic. Earlier pulmonary function testing revealed a restrictive pattern with interstitial infiltrates seen on chest computed tomography. A lung biopsy demonstrated features of fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis with superimposed eosinophilic pneumonia. His pulmonary symptoms had progressively worsened; over a period of several months, the supplemental oxygen requirement had increased to 6 L at rest and 12 L upon exertion. Prednisone therapy was initiated, which alleviated respiratory symptoms; however, the patient was unable to tolerate a gradual wean of the medication, which rendered him steroid dependent at 30 mg/d.

Along with respiratory symptoms, the patient reported symptoms consistent with an autoimmune process, including dry eyes. Muscle weakness and tenderness also were noted. Ultimately, a diagnosis of anti–PL-7 (anti-threonyl-transfer RNA synthetase) antisynthetase syndrome was rendered by identification of anti–PL-7 antibodies and an elevated level of creatinine kinase.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed subtle palmar scaling on the hands and multiple small clear vesicles on the lateral aspects of the digits (Figure, A), consistent with dyshidrotic eczema. He initially was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%. Despite adherence to this high-potency topical corticosteroid, he experienced only minimal improvement over a period of 3 months. Dupilumab was started at standard dosing—600 mg at initiation, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. The patient reported rapid improvement in dyshidrotic eczema over several months with near-complete resolution (Figure, B).

Concurrent with initiation and continued use of dupilumab, without other changes in his medication regimen, the patient noted gradual improvement in respiratory symptoms. At 6-month follow-up he reported notable improvement in respiratory function and quality of life. He then tolerated a gradual wean of prednisone to 10 mg/d, with a similar reduction in supplemental oxygen.

Off-label use of dupilumab for various eosinophilic conditions has shown promising efficacy. Our patient experienced improvement in CEP shortly after initiation of dupilumab, enabling weaning of prednisone, which has a well established adverse effect profile associated with long term use.3,4 In comparison, dupilumab generally is well tolerated, with rare ophthalmologic complications and injection-site reactions.5

One case report suggested that CEP may represent a potential rare adverse effect of dupilumab initiation.6 However, prior to initiation of dupilumab, that patient had poorly controlled asthma requiring frequent oral corticosteroid therapy. It is possible that CEP was subclinical prior to initiation of dupilumab and became more noticeable once the patient was weaned from corticosteroids, which had served as an indirect treatment.6 Nonetheless, more research is needed to definitively establish the efficacy of dupilumab in CEP prior to more widespread use.

Irrespective of the potential efficacy of dupilumab for the treatment of CEP, our case highlights the growing body of evidence that dupilumab should be considered in the treatment of dyshidrotic eczema, particularly in cases refractory to topical treatment.7 When a systemic medication is preferred, dupilumab likely represents an option with a relatively well-tolerated adverse effect profile compared to traditional systemic treatments for dyshidrotic eczema.

To the Editor:

Biologic medications are increasingly utilized in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis (AD) that is inadequately controlled with topical medication. By targeting the IL-4 receptor alpha subunit, dupilumab inhibits the biologic effects of IL-4 and IL-13, resulting in remarkable improvement in disease and quality of life for many patients with refractory AD.1

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved dupilumab for use in AD, asthma, and chronic rhinosinusitis. However, there is evidence of the drug’s off-label efficacy in conditions such as eosinophilic annular erythema.2 We present a patient with dyshidrotic eczema treated with dupilumab who experienced contemporaneous secondary improvement in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) and interstitial lung disease (ILD).

A 45-year-old man was referred to our dermatology clinic for chronic hand dermatitis refractory to increasing strengths of topical corticosteroids. He had a history of progressive shortness of breath of unknown cause, which began 2 years prior, and he was being followed at our institution’s ILD clinic. Earlier pulmonary function testing revealed a restrictive pattern with interstitial infiltrates seen on chest computed tomography. A lung biopsy demonstrated features of fibrotic nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis with superimposed eosinophilic pneumonia. His pulmonary symptoms had progressively worsened; over a period of several months, the supplemental oxygen requirement had increased to 6 L at rest and 12 L upon exertion. Prednisone therapy was initiated, which alleviated respiratory symptoms; however, the patient was unable to tolerate a gradual wean of the medication, which rendered him steroid dependent at 30 mg/d.

Along with respiratory symptoms, the patient reported symptoms consistent with an autoimmune process, including dry eyes. Muscle weakness and tenderness also were noted. Ultimately, a diagnosis of anti–PL-7 (anti-threonyl-transfer RNA synthetase) antisynthetase syndrome was rendered by identification of anti–PL-7 antibodies and an elevated level of creatinine kinase.

Physical examination at our clinic revealed subtle palmar scaling on the hands and multiple small clear vesicles on the lateral aspects of the digits (Figure, A), consistent with dyshidrotic eczema. He initially was treated with clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05%. Despite adherence to this high-potency topical corticosteroid, he experienced only minimal improvement over a period of 3 months. Dupilumab was started at standard dosing—600 mg at initiation, followed by 300 mg every 2 weeks. The patient reported rapid improvement in dyshidrotic eczema over several months with near-complete resolution (Figure, B).

Concurrent with initiation and continued use of dupilumab, without other changes in his medication regimen, the patient noted gradual improvement in respiratory symptoms. At 6-month follow-up he reported notable improvement in respiratory function and quality of life. He then tolerated a gradual wean of prednisone to 10 mg/d, with a similar reduction in supplemental oxygen.

Off-label use of dupilumab for various eosinophilic conditions has shown promising efficacy. Our patient experienced improvement in CEP shortly after initiation of dupilumab, enabling weaning of prednisone, which has a well established adverse effect profile associated with long term use.3,4 In comparison, dupilumab generally is well tolerated, with rare ophthalmologic complications and injection-site reactions.5

One case report suggested that CEP may represent a potential rare adverse effect of dupilumab initiation.6 However, prior to initiation of dupilumab, that patient had poorly controlled asthma requiring frequent oral corticosteroid therapy. It is possible that CEP was subclinical prior to initiation of dupilumab and became more noticeable once the patient was weaned from corticosteroids, which had served as an indirect treatment.6 Nonetheless, more research is needed to definitively establish the efficacy of dupilumab in CEP prior to more widespread use.

Irrespective of the potential efficacy of dupilumab for the treatment of CEP, our case highlights the growing body of evidence that dupilumab should be considered in the treatment of dyshidrotic eczema, particularly in cases refractory to topical treatment.7 When a systemic medication is preferred, dupilumab likely represents an option with a relatively well-tolerated adverse effect profile compared to traditional systemic treatments for dyshidrotic eczema.

1. Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, Silverberg JI, et al. Dupilumab provides rapid and sustained improvement in SCORAD outcomes in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: combined results ofour randomized phase 3 trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:266-277. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1750550

2. Gordon SC, Robinson SN, Abudu M, et al. Eosinophilic annular erythema treated with dupilumab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E255-E256. doi:10.1111/pde.13533

3. Callaghan DJ 3rd. Use of Google Trends to examine interest in Mohs micrographic surgery: 2004 to 2016. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:186-192. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001270

4. Fowler C, Hoover W. Dupilumab for chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:3229-3230. doi:10.1002/ppul.25096

5. Simpson EL, Akinlade B, Ardeleanu M. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1090-1091. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1700366

6. Menzella F, Montanari G, Patricelli G, et al. A case of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia in a patient treated with dupilumab. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:869-875. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S207402

7. Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan B, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of dyshidrotic eczema in 15 consecutive patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1251-1252. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.053

1. Barbarot S, Wollenberg A, Silverberg JI, et al. Dupilumab provides rapid and sustained improvement in SCORAD outcomes in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: combined results ofour randomized phase 3 trials. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:266-277. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1750550

2. Gordon SC, Robinson SN, Abudu M, et al. Eosinophilic annular erythema treated with dupilumab. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E255-E256. doi:10.1111/pde.13533

3. Callaghan DJ 3rd. Use of Google Trends to examine interest in Mohs micrographic surgery: 2004 to 2016. Dermatol Surg. 2018;44:186-192. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001270

4. Fowler C, Hoover W. Dupilumab for chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2020;55:3229-3230. doi:10.1002/ppul.25096

5. Simpson EL, Akinlade B, Ardeleanu M. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1090-1091. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1700366

6. Menzella F, Montanari G, Patricelli G, et al. A case of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia in a patient treated with dupilumab. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2019;15:869-875. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S207402

7. Waldman RA, DeWane ME, Sloan B, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of dyshidrotic eczema in 15 consecutive patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1251-1252. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.053

Practice Points

- Dupilumab can be considered for treatment of refractory dyshidrotic eczema.

- Dupilumab may provide secondary efficacy in patients with dyshidrotic eczema who also have an eosinophilic condition such as eosinophilic pneumonia.

Paradoxical Reaction to TNF-α Inhibitor Therapy in a Patient With Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

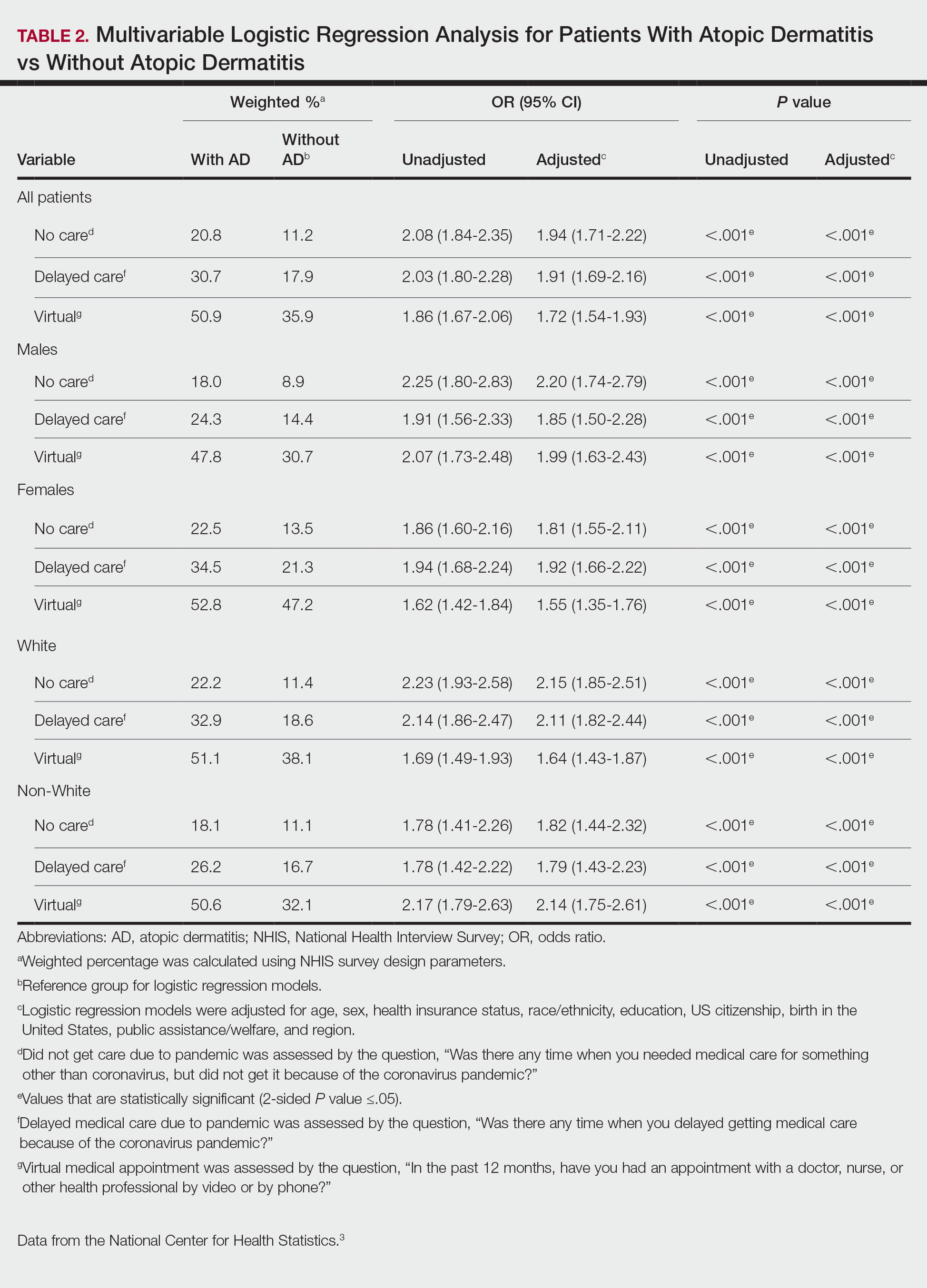

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory condition of the pilosebaceous unit that occurs in concert with elevations of various cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-1β, IL-10, and IL-17.1,2 Adalimumab is a TNF-α inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS. Although TNF-α inhibitors are effective for many immune-mediated inflammatory disorders, paradoxical drug reactions have been reported following treatment with these agents.3-6 True paradoxical drug reactions likely are immune mediated and directly lead to new onset of a pathologic condition that would otherwise respond to that drug. For example, there are reports of rheumatoid arthritis patients who were treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed psoriatic skin lesions.3,6 Paradoxical drug reactions also have been reported with acute-onset inflammatory bowel disease and HS or less commonly pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), uveitis, granulomatous reactions, and vasculitis.4,5 We present the case of a patient with HS who was treated with a TNF-α inhibitor and developed 2 distinct paradoxical drug reactions. We also provide an overview of paradoxical drug reactions associated with TNF-α inhibitors.

A 38-year-old woman developed a painful “boil” on the right leg that was previously treated in the emergency department with incision and drainage as well as oral clindamycin for 7 days, but the lesion spread and continued to worsen. She had a history of HS in the axillae and groin region that had been present since 12 years of age. The condition was poorly controlled despite multiple courses of oral antibiotics and surgical resections. An oral contraceptive also was attempted, but the patient discontinued treatment when liver enzyme levels became elevated. The patient had no other notable medical history, including skin disease. There was a family history of HS in her father and a sibling. Seeking more effective treatment, the patient was offered adalimumab approximately 4 months prior to clinical presentation and agreed to start a course of the drug. She received a loading dose of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15 followed by a maintenance dosage of 40 mg weekly. She experienced improvement in HS symptoms after 3 months on adalimumab; however, she developed scaly pruritic patches on the scalp, arms, and legs that were consistent with psoriasis. Because of the absence of a personal or family history of psoriasis, the patient was informed of the probability of paradoxical psoriasis resulting from adalimumab. She elected to continue adalimumab because of the improvement in HS symptoms, and the psoriatic lesions were mild and adequately controlled with a topical steroid.

At the current presentation 1 month later, physical examination revealed a large indurated and ulcerated area with jagged edges at the incision and drainage site (Figure 1). Pyoderma gangrenosum was clinically suspected; a biopsy was performed, and the patient was started on oral prednisone. At 2-week follow-up, the ulcer was found to be rapidly resolving with prednisone and healing with cribriform scarring (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed an undermining neutrophilic inflammatory process that was consistent with PG. A diagnosis of PG was made based on previously published criteria7 and the following major/minor criteria in the patient: pathology; absence of infection on histologic analysis; history of pathergy related to worsening ulceration at the site of incision and drainage of the initial boil; clinical findings of an ulcer with peripheral violaceous erythema; undermined borders and tenderness at the site; and rapid resolution of the ulcer with prednisone.

Cessation of adalimumab gradually led to clearance of both psoriasiform lesions and PG; however, HS lesions persisted.

Although the precise pathogenesis of HS is unclear, both genetic abnormalities of the pilosebaceous unit and a dysregulated immune reaction appear to lead to the clinical characteristics of chronic inflammation and scarring seen in HS. A key effector appears to be helper T-cell (TH17) lymphocyte activation, with increased secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-17.1,2 In turn, IL-17 induces higher expression of TNF-α, leading to a persistent cycle of inflammation. Peripheral recruitment of IL-17–producing neutrophils also may contribute to chronic inflammation.8

Adalimumab is the only US Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic indicated for the treatment of HS. Our patient initially responded to adalimumab with improvement of HS; however, treatment had to be discontinued because of the unusual occurrence of 2 distinct paradoxical reactions in a short span of time. Psoriasis and PG are both considered true paradoxical reactions because primary occurrences of both diseases usually are responsive to treatment with adalimumab.

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced psoriasis arises de novo and is estimated to occur in approximately 5% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.3,6 Palmoplantar pustular psoriasiform reactions are the most common form of paradoxical psoriasis. Topical medications can be used to treat skin lesions, but systemic treatment is required in many cases. Switching to an alternate class of a biologic, such as an IL-17, IL-12/23, or IL-23 inhibitor, can improve the skin reaction; however, such treatment is inconsistently successful, and paradoxical drug reactions also have been seen with these other classes of biologics.4,9

Recent studies support distinct immune causes for classical and paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) produce IFN-α, which stimulates conventional dendritic cells to produce TNF-α. However, TNF-α matures both pDCs and conventional dendritic cells; upon maturation, both types of dendritic cells lose the ability to produce IFN-α, thus allowing TNF-α to become dominant.10 The blockade of TNF-α prevents pDC maturation, leading to uninhibited IFN-α, which appears to drive inflammation in paradoxical psoriasis. In classical psoriasis, oligoclonal dermal CD4+ T cells and epidermal CD8+ T cells remain, even in resolved skin lesions, and can cause disease recurrence through reactivation of skin-resident memory T cells.11 No relapse of paradoxical psoriasis occurs with discontinuation of anti-TNF-α therapy, which supports the notion of an absence of memory T cells.

The incidence of paradoxical psoriasis in patients receiving a TNF-α inhibitor for HS is unclear.12 There are case series in which patients who had concurrent psoriasis and HS were successfully treated with a TNF-α inhibitor.13 A recently recognized condition—PASH syndrome—encompasses the clinical triad of PG, acne, and HS.10

Our patient had no history of acne or PG, only a long-standing history of HS. New-onset PG occurred only after a TNF-α inhibitor was initiated. Notably, PASH syndrome has been successfully treated with TNF-α inhibitors, highlighting the shared inflammatory etiology of HS and PG.14 In patients with concurrent PG and HS, TNF-α inhibitors were more effective for treating PG than for HS.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is an inflammatory disorder that often occurs concomitantly with other conditions, such as inflammatory bowel disease. The exact underlying cause of PG is unclear, but there appears to be both neutrophil and T-cell dysfunction in PG, with excess inflammatory cytokine production (eg, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-17).15

The mainstay of treatment of PG is systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressives, such as cyclosporine. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors as well as other interleukin inhibitors are increasingly utilized as potential therapeutic alternatives for PG.16,17

Unlike paradoxical psoriasis, the underlying cause of paradoxical PG is unclear.18,19 A similar mechanism may be postulated whereby inhibition of TNF-α leads to excessive activation of alternative inflammatory pathways that result in paradoxical PG. In one study, the prevalence of PG among 68,232 patients with HS was 0.18% compared with 0.01% among those without HS; therefore, patients with HS appear to be more predisposed to PG.20

This case illustrates the complex, often conflicting effects of cytokine inhibition in the paradoxical elicitation of alternative inflammatory disorders as an unintended consequence of the initial cytokine blockade. It is likely that genetic predisposition allows for paradoxical reactions in some patients when there is predominant inhibition of one cytokine in the inflammatory pathway. In rare cases, multiple paradoxical reactions are possible.

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

1. Vossen ARJV, van der Zee HH, Prens EP. Hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review integrating inflammatory pathways into a cohesive pathogenic model. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2965. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02965

2. Goldburg SR, Strober BE, Payette MJ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology, clinical presentation and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020; 82:1045-1058. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.090

3. Brown G, Wang E, Leon A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitor-induced psoriasis: systematic review of clinical features, histopathological findings, and management experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:334-341. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.012

4. Puig L. Paradoxical reactions: anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab and others. Curr Prob Dermatol. 2018;53:49-63. doi:10.1159/000479475

5. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al; . Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

6. Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. doi:10.1080/09546630802441234

7. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:461-466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

8. Lima AL, Karl I, Giner T, et al. Keratinocytes and neutrophils are important sources of proinflammatory molecules in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:514-521. doi:10.1111/bjd.14214

9. Li SJ, Perez-Chada LM, Merola JF. TNF inhibitor-induced psoriasis: proposed algorithm for treatment and management. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2019;4:70-80. doi:10.1177/2475530318810851

10. Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9:25. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02466-4

11. Matos TR, O’Malley JT, Lowry EL, et al. Clinically resolved psoriatic lesions contain psoriasis-specific IL-17-producing αβ T cell clones. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4031-4041. doi:10.1172/JCI93396

12. Faivre C, Villani AP, Aubin F, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS): an unrecognized paradoxical effect of biologic agents (BA) used in chronic inflammatory diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1153-1159. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.01.018

13. Marzano AV, Damiani G, Ceccherini I, et al. Autoinflammation in pyoderma gangrenosum and its syndromic form (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and suppurative hidradenitis). Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1588-1598. doi:10.1111/bjd.15226

14. Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH, PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18:555-562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

15. Wang EA, Steel A, Luxardi G, et al. Classic ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum is a T cell-mediated disease targeting follicular adnexal structures: a hypothesis based on molecular and clinicopathologic studies. Front Immunol. 2018;8:1980. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01980

16. Patel F, Fitzmaurice S, Duong C, et al. Effective strategies for the management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:525-531. doi:10.2340/00015555-2008

17. Partridge ACR, Bai JW, Rosen CF, et al. Effectiveness of systemic treatments for pyoderma gangrenosum: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:290-295. doi:10.1111/bjd.16485

18. Benzaquen M, Monnier J, Beaussault Y, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum arising during treatment of psoriasis with adalimumab: effectiveness of ustekinumab. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e270-e271. doi:10.1111/ajd.12545

19. Fujimoto N, Yamasaki Y, Watanabe RJ. Paradoxical uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis under infliximab treatment. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:1139-1140. doi:10.1111/ddg.13632

20. Tannenbaum R, Strunk A, Garg A. Overall and subgroup prevalence of pyoderma gangrenosum among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a population-based analysis in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1533-1537. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.004

Practice Points

- Clinicians need to be aware of the potential risk for a paradoxical reaction in patients receiving a tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor for hidradenitis suppurativa.

- Although uncommon, developing more than 1 type of paradoxical skin reaction is possible with a TNF-α inhibitor.

- Early recognition and appropriate management of these paradoxical reactions are critical.

Abstracts from the Neurology Exchange 2023, a virtual event held September 19-21, 2023

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Care for Patients With Atopic Dermatitis

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widely prevalent dermatologic condition that can severely impact a patient’s quality of life.1 Individuals with AD have been substantially affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased use of irritants, decreased access to care, and rise in psychological stress.1,2 These factors have resulted in lower quality of life and worsening dermatologic symptoms for many AD patients over the last few years.1 One major potential contributory component of these findings is decreased accessibility to in-office care during the pandemic, with a shift to telemedicine instead. Accessibility to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for AD patients compared to those without AD remains unknown. Therefore, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with AD in a large US population.

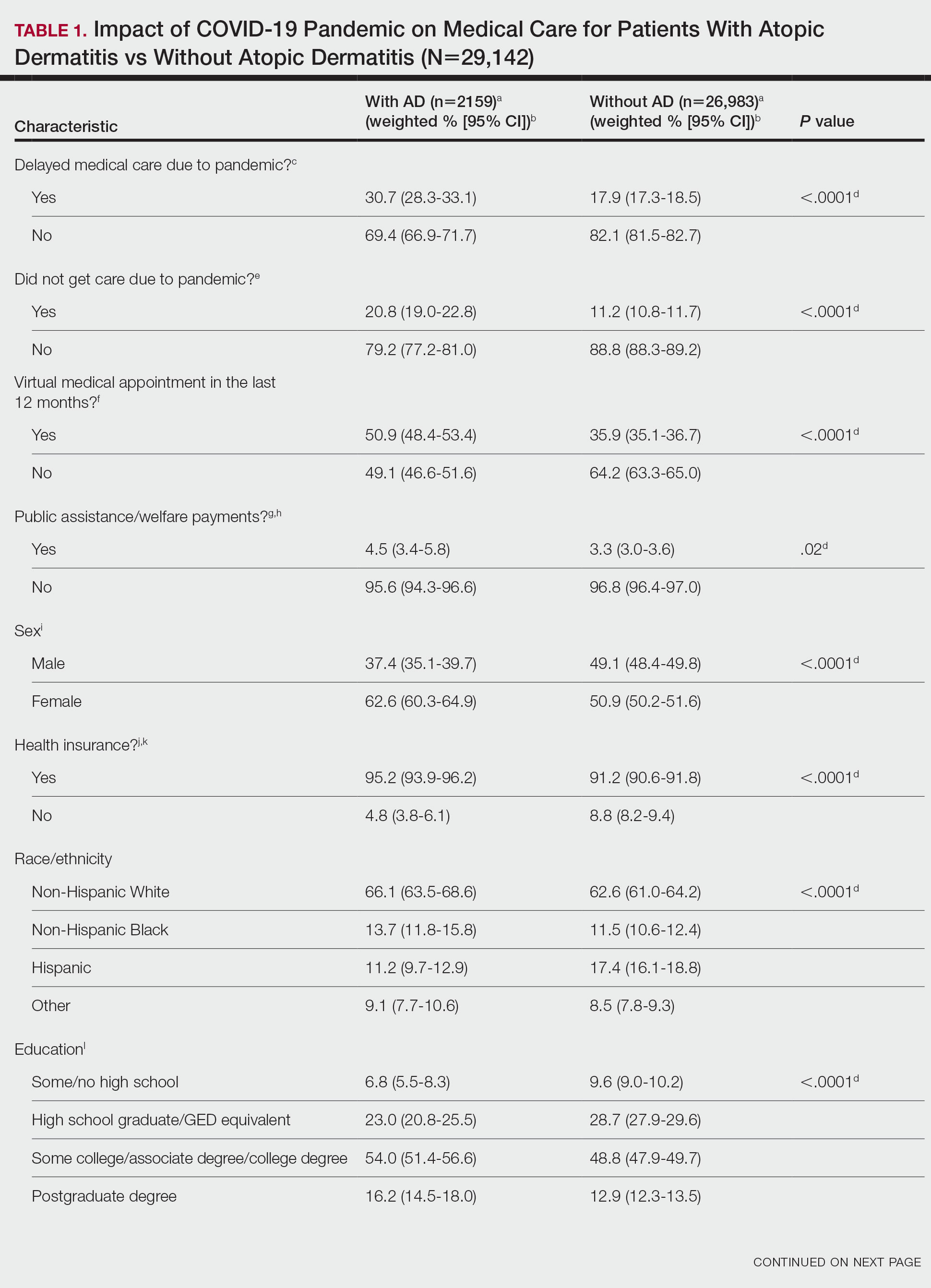

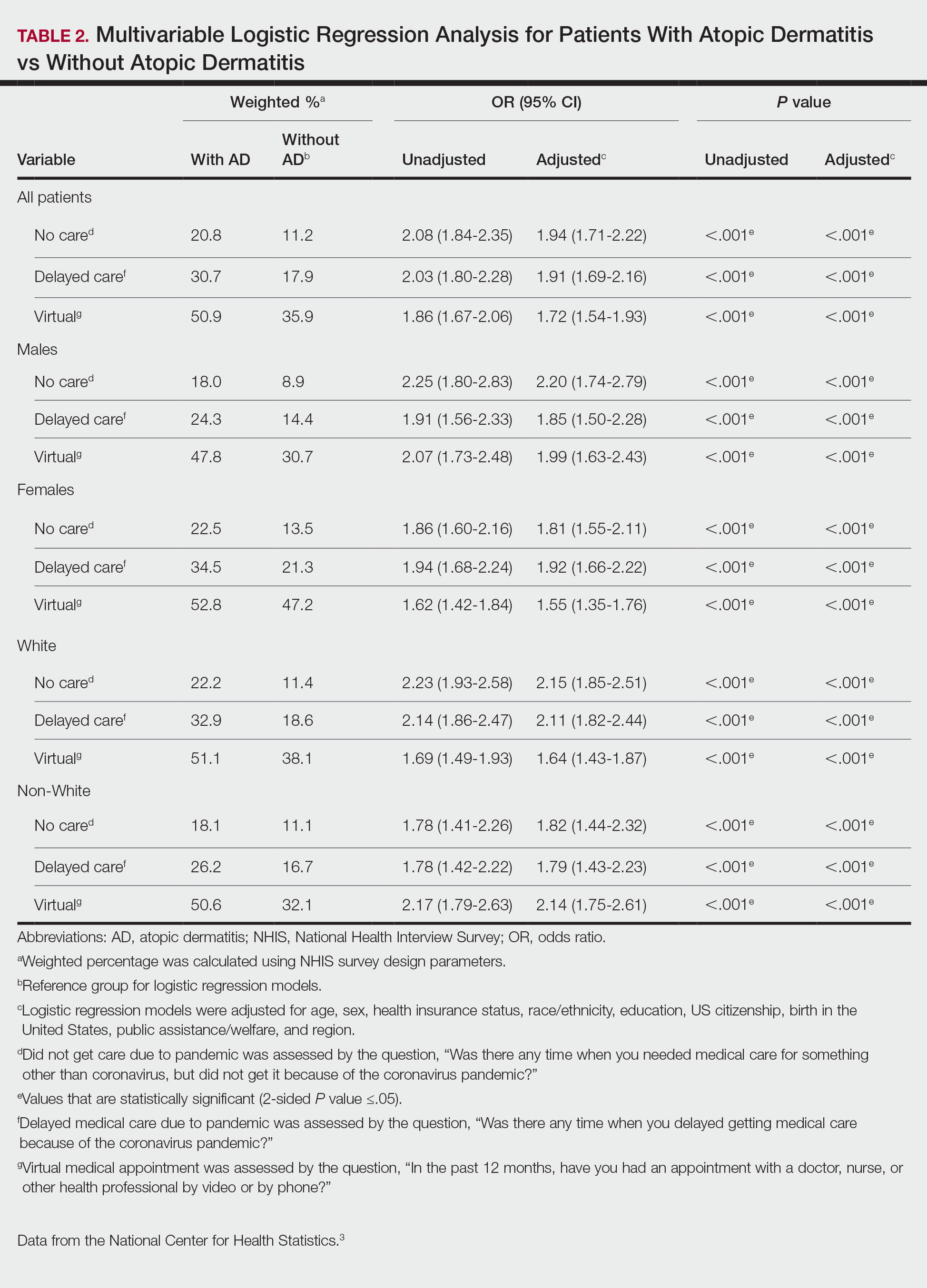

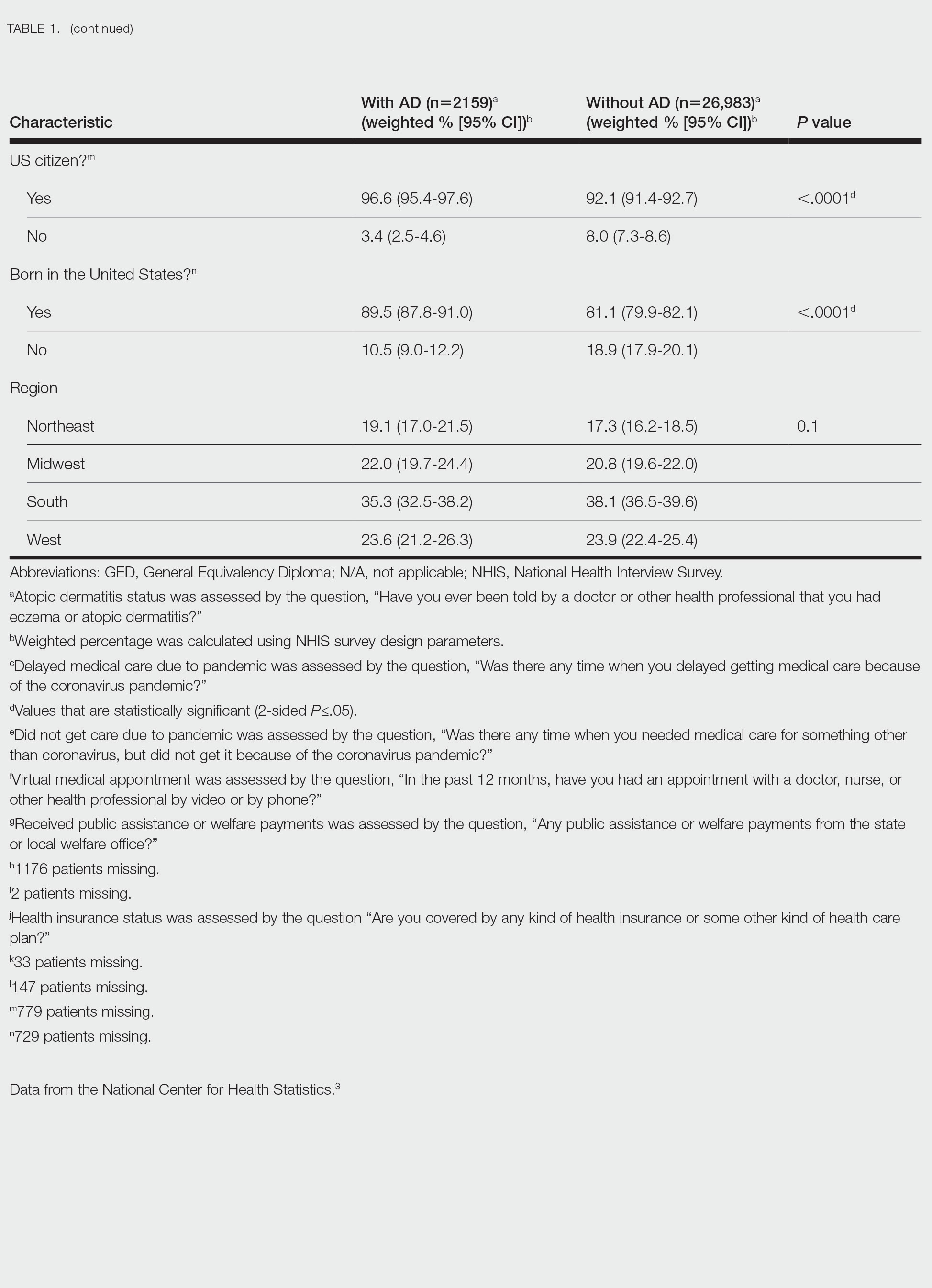

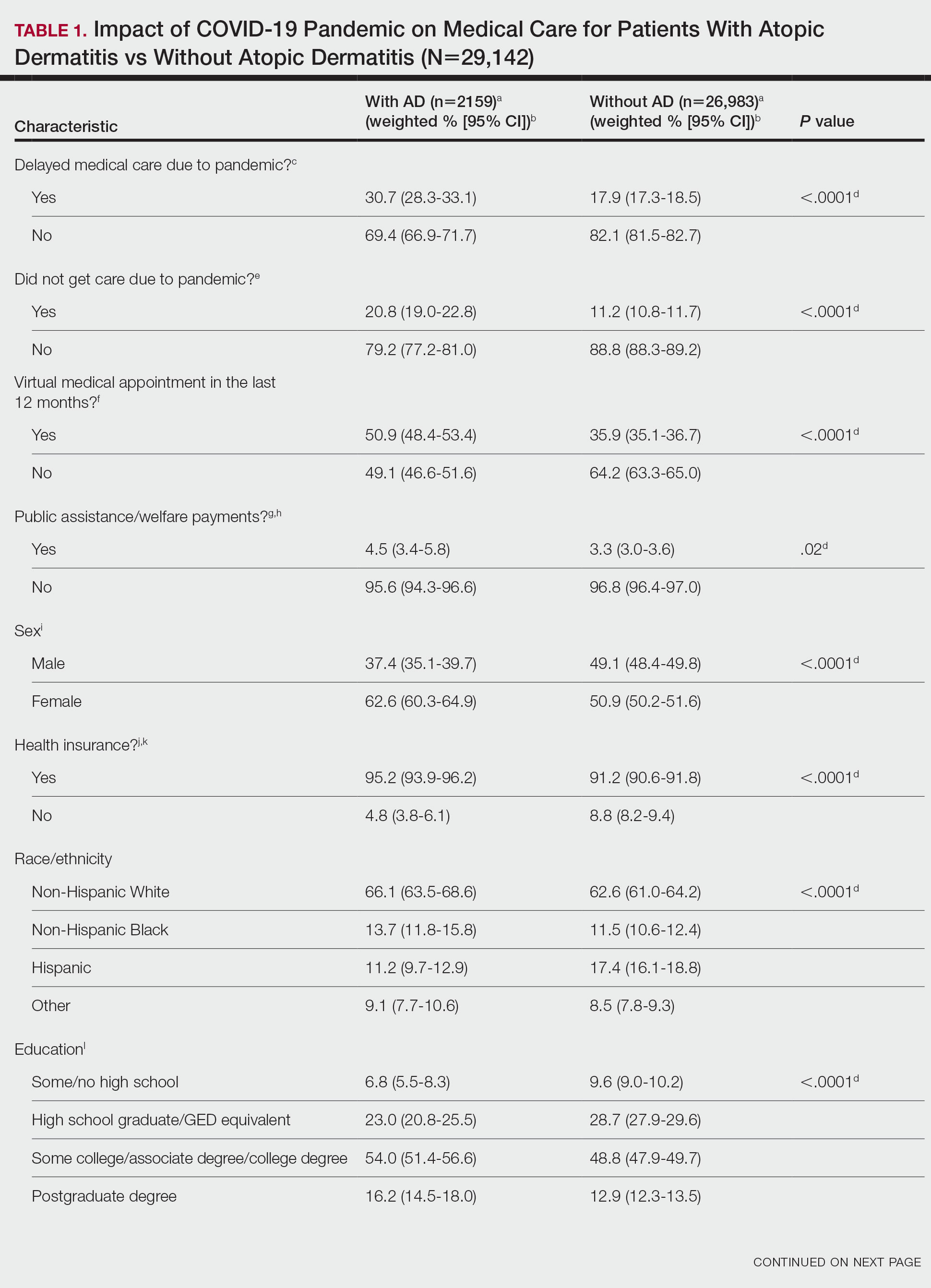

Using anonymous survey data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey,3 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with AD compared to those without AD. We assigned the following 3 survey questions as outcome variables to assess access to care: delayed medical care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), did not get care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and virtual medical appointment in the last 12 months (yes/no). In Table 1, numerous categorical survey variables, including sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region, were analyzed using χ2 testing to evaluate for differences among individuals with and without AD. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between AD and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our analysis we controlled for age, sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region.

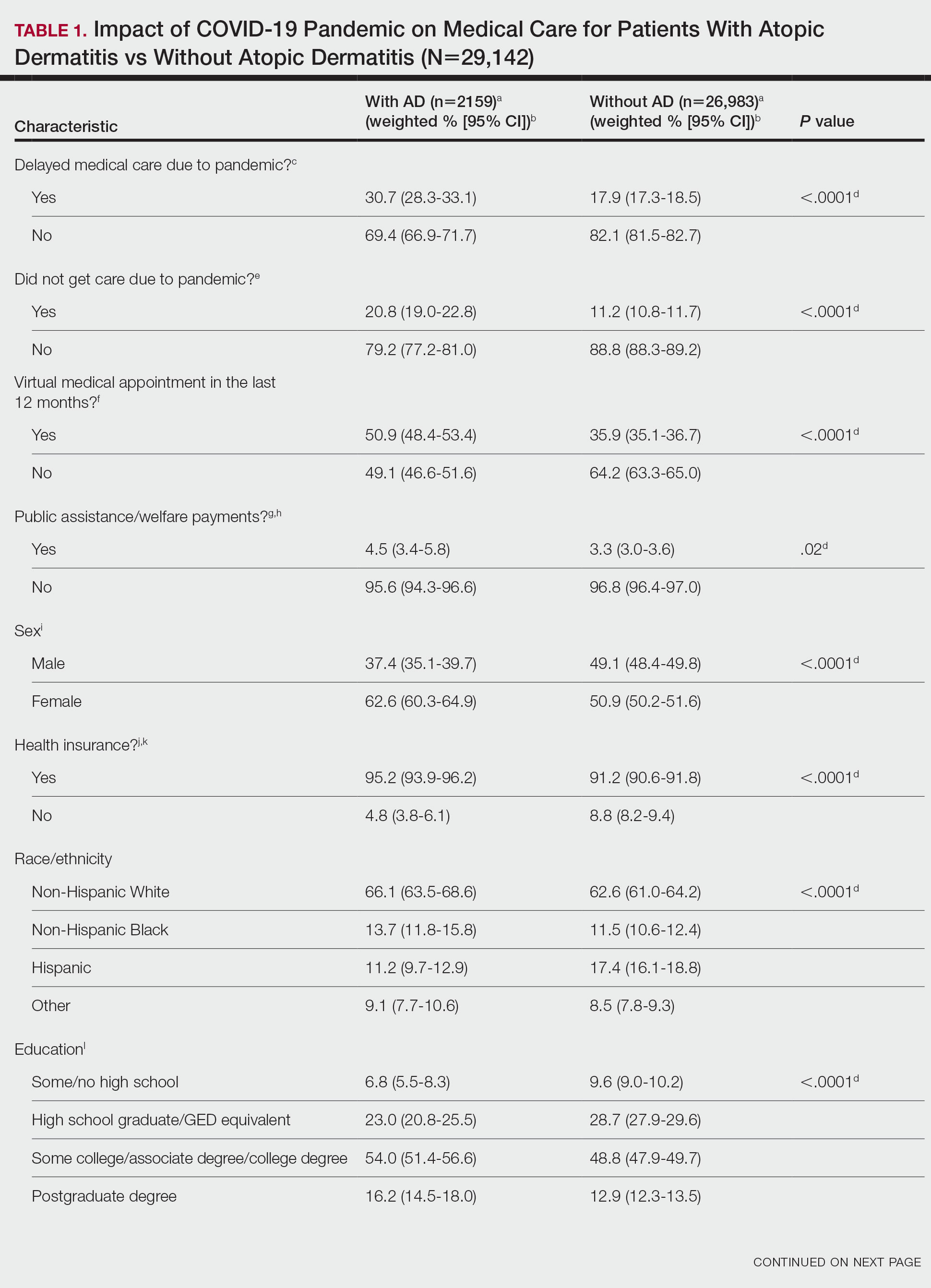

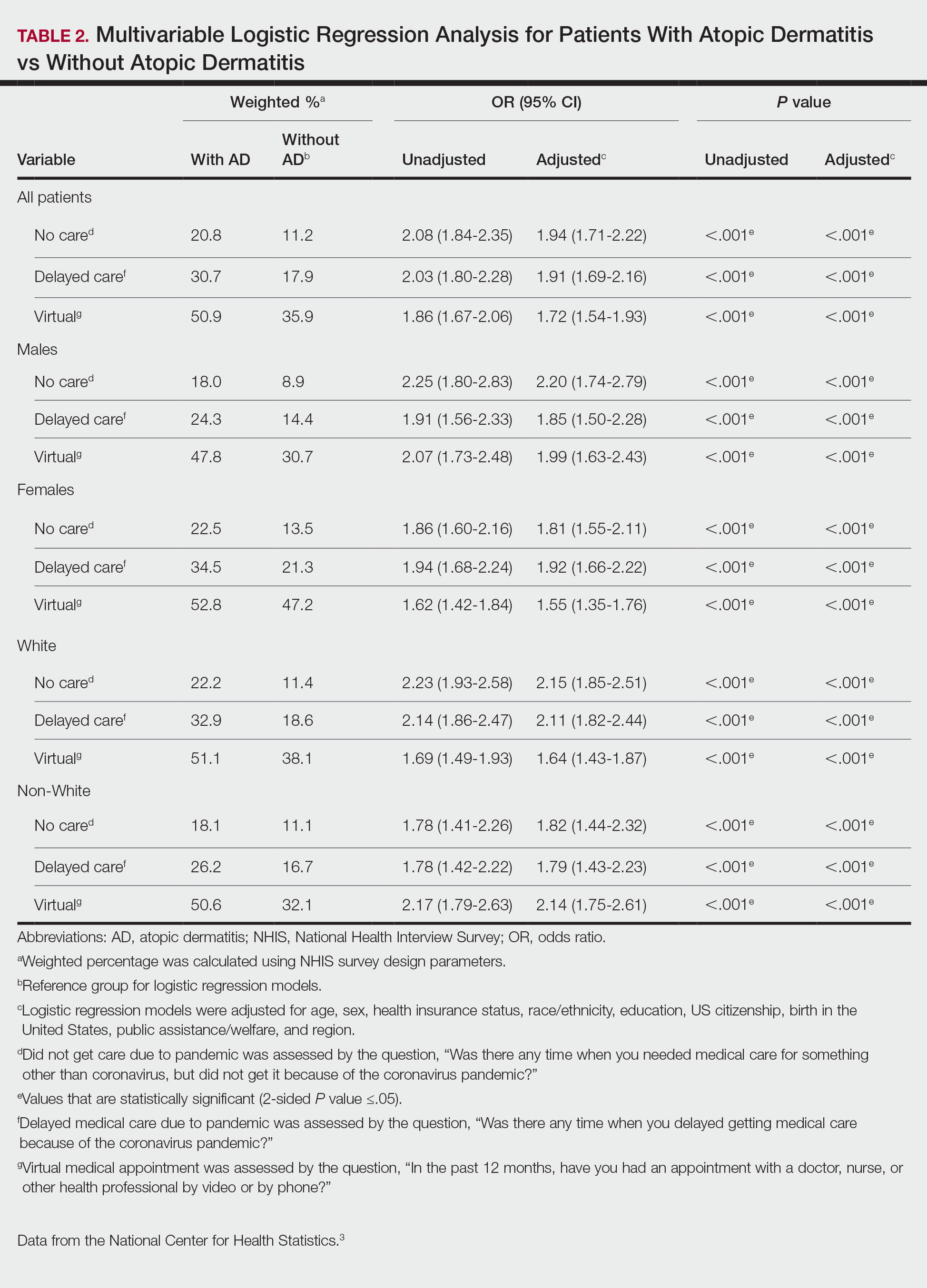

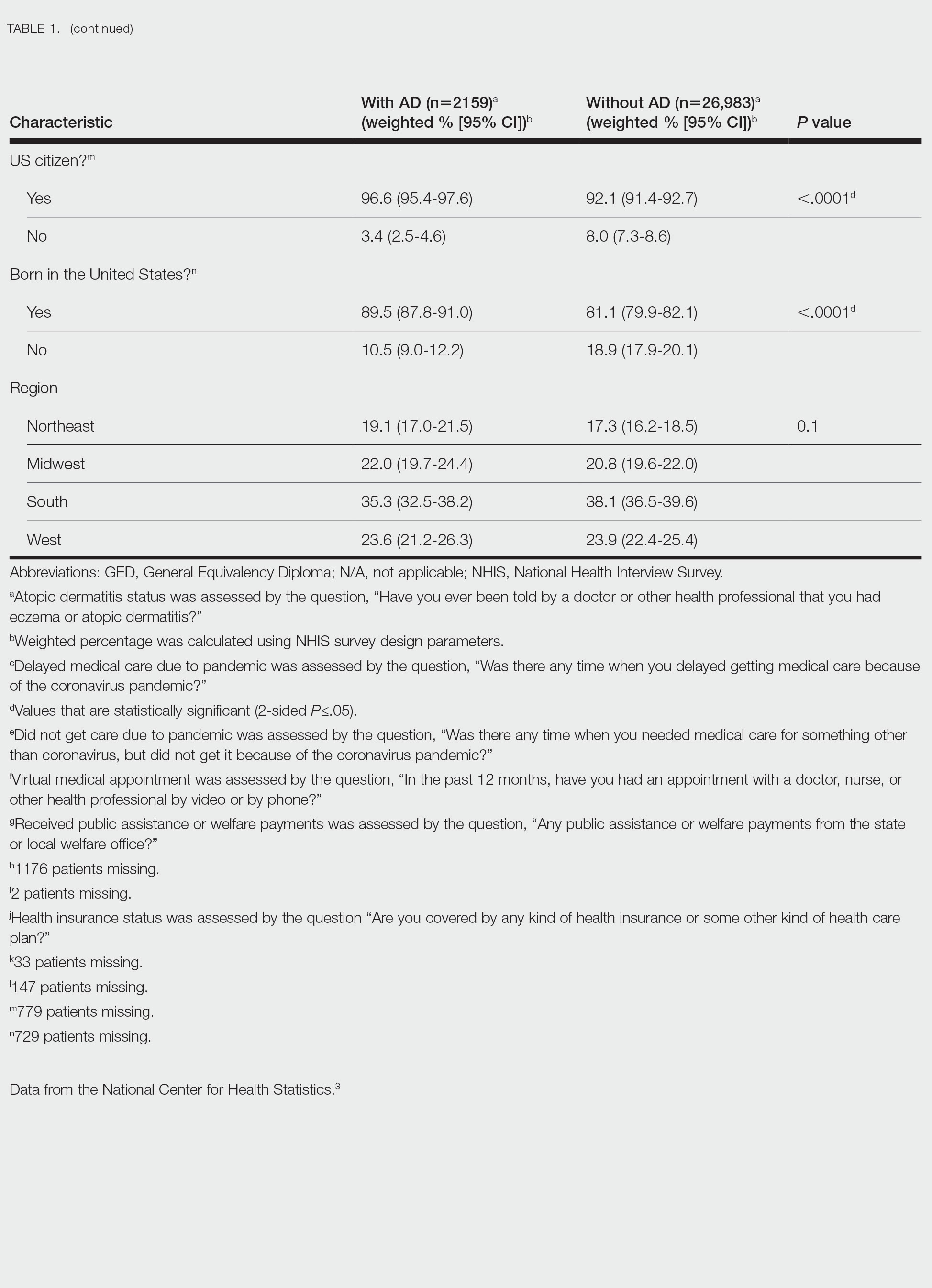

There were 29,142 adult patients (aged ≥18 years) included in our analysis. Approximately 7.4% (weighted) of individuals had AD (Table 1). After adjusting for confounding variables, patients with AD had a higher odds of delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.91; 95% CI, 1.69-2.16; P<.001), not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (AOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.71-2.22; P<.001), and having a virtual medical visit in the last 12 months (AOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.54-1.93; P<.001)(Table 2) compared with patients without AD.

Our findings support the association between AD and decreased access to in-person care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, telemedicine was utilized more among individuals with AD, possibly due to the accessibility of diagnostic tools for dermatologic diagnoses, such as high-quality photographs.4 According to Trinidad et al,4 telemedicine became an invaluable tool for dermatology hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many physicians were able to comfortably diagnose patients with cutaneous diseases without an in-person visit. Utilizing telemedicine for patient care can help reduce the risk for COVID-19 transmission while also providing quality care for individuals living in rural areas.5 Chiricozzi et al6 discussed the importance of telemedicine in Italy during the pandemic, as many AD patients were able to maintain control of their disease while on systemic treatments.

Limitations of this study include self-reported measures; inability to compare patients with AD to individuals with other cutaneous diseases; and additional potential confounders, such as chronic comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate the use of telemedicine and access to care among individuals with other common skin diseases and help determine why such discrepancies exist. Understanding the difficulties in access to care and the viable alternatives in place may increase awareness and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

1. Sieniawska J, Lesiak A, Cia˛z˙yn´ski K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031734

2. Pourani MR, Ganji R, Dashti T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286-T293. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004

3. National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

4. Trinidad J, Gabel CK, Han JJ, et al. Telemedicine and dermatology hospital consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-centre observational study on resource utilization and conversion to in-person consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E323-E325. doi:10.1111/jdv.17898

5. Marasca C, Annunziata MC, Camela E, et al. Teledermatology and inflammatory skin conditions during COVID-19 era: new perspectives and applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1511. doi:10.3390/jcm11061511

6. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813-1824. doi:10.1111/all.14767

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widely prevalent dermatologic condition that can severely impact a patient’s quality of life.1 Individuals with AD have been substantially affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased use of irritants, decreased access to care, and rise in psychological stress.1,2 These factors have resulted in lower quality of life and worsening dermatologic symptoms for many AD patients over the last few years.1 One major potential contributory component of these findings is decreased accessibility to in-office care during the pandemic, with a shift to telemedicine instead. Accessibility to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for AD patients compared to those without AD remains unknown. Therefore, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with AD in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey,3 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with AD compared to those without AD. We assigned the following 3 survey questions as outcome variables to assess access to care: delayed medical care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), did not get care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and virtual medical appointment in the last 12 months (yes/no). In Table 1, numerous categorical survey variables, including sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region, were analyzed using χ2 testing to evaluate for differences among individuals with and without AD. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between AD and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our analysis we controlled for age, sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region.

There were 29,142 adult patients (aged ≥18 years) included in our analysis. Approximately 7.4% (weighted) of individuals had AD (Table 1). After adjusting for confounding variables, patients with AD had a higher odds of delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.91; 95% CI, 1.69-2.16; P<.001), not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (AOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.71-2.22; P<.001), and having a virtual medical visit in the last 12 months (AOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.54-1.93; P<.001)(Table 2) compared with patients without AD.

Our findings support the association between AD and decreased access to in-person care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, telemedicine was utilized more among individuals with AD, possibly due to the accessibility of diagnostic tools for dermatologic diagnoses, such as high-quality photographs.4 According to Trinidad et al,4 telemedicine became an invaluable tool for dermatology hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many physicians were able to comfortably diagnose patients with cutaneous diseases without an in-person visit. Utilizing telemedicine for patient care can help reduce the risk for COVID-19 transmission while also providing quality care for individuals living in rural areas.5 Chiricozzi et al6 discussed the importance of telemedicine in Italy during the pandemic, as many AD patients were able to maintain control of their disease while on systemic treatments.

Limitations of this study include self-reported measures; inability to compare patients with AD to individuals with other cutaneous diseases; and additional potential confounders, such as chronic comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate the use of telemedicine and access to care among individuals with other common skin diseases and help determine why such discrepancies exist. Understanding the difficulties in access to care and the viable alternatives in place may increase awareness and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

To the Editor:

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a widely prevalent dermatologic condition that can severely impact a patient’s quality of life.1 Individuals with AD have been substantially affected during the COVID-19 pandemic due to the increased use of irritants, decreased access to care, and rise in psychological stress.1,2 These factors have resulted in lower quality of life and worsening dermatologic symptoms for many AD patients over the last few years.1 One major potential contributory component of these findings is decreased accessibility to in-office care during the pandemic, with a shift to telemedicine instead. Accessibility to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for AD patients compared to those without AD remains unknown. Therefore, we explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with AD in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2021 National Health Interview Survey,3 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with AD compared to those without AD. We assigned the following 3 survey questions as outcome variables to assess access to care: delayed medical care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), did not get care due to COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and virtual medical appointment in the last 12 months (yes/no). In Table 1, numerous categorical survey variables, including sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region, were analyzed using χ2 testing to evaluate for differences among individuals with and without AD. Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between AD and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17 (StataCorp LLC). In our analysis we controlled for age, sex, health insurance status, race/ethnicity, education, US citizenship, birth in the United States, public assistance/welfare, and region.

There were 29,142 adult patients (aged ≥18 years) included in our analysis. Approximately 7.4% (weighted) of individuals had AD (Table 1). After adjusting for confounding variables, patients with AD had a higher odds of delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.91; 95% CI, 1.69-2.16; P<.001), not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (AOR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.71-2.22; P<.001), and having a virtual medical visit in the last 12 months (AOR, 1.72; 95% CI, 1.54-1.93; P<.001)(Table 2) compared with patients without AD.

Our findings support the association between AD and decreased access to in-person care due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, telemedicine was utilized more among individuals with AD, possibly due to the accessibility of diagnostic tools for dermatologic diagnoses, such as high-quality photographs.4 According to Trinidad et al,4 telemedicine became an invaluable tool for dermatology hospitalists during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many physicians were able to comfortably diagnose patients with cutaneous diseases without an in-person visit. Utilizing telemedicine for patient care can help reduce the risk for COVID-19 transmission while also providing quality care for individuals living in rural areas.5 Chiricozzi et al6 discussed the importance of telemedicine in Italy during the pandemic, as many AD patients were able to maintain control of their disease while on systemic treatments.

Limitations of this study include self-reported measures; inability to compare patients with AD to individuals with other cutaneous diseases; and additional potential confounders, such as chronic comorbidities. Future studies should evaluate the use of telemedicine and access to care among individuals with other common skin diseases and help determine why such discrepancies exist. Understanding the difficulties in access to care and the viable alternatives in place may increase awareness and assist clinicians with adequate management of patients with AD.

1. Sieniawska J, Lesiak A, Cia˛z˙yn´ski K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031734

2. Pourani MR, Ganji R, Dashti T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286-T293. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004

3. National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

4. Trinidad J, Gabel CK, Han JJ, et al. Telemedicine and dermatology hospital consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-centre observational study on resource utilization and conversion to in-person consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E323-E325. doi:10.1111/jdv.17898

5. Marasca C, Annunziata MC, Camela E, et al. Teledermatology and inflammatory skin conditions during COVID-19 era: new perspectives and applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1511. doi:10.3390/jcm11061511

6. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813-1824. doi:10.1111/all.14767

1. Sieniawska J, Lesiak A, Cia˛z˙yn´ski K, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on atopic dermatitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1734. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031734

2. Pourani MR, Ganji R, Dashti T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on patients with atopic dermatitis [in Spanish]. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T286-T293. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2021.08.004

3. National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed February 1, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

4. Trinidad J, Gabel CK, Han JJ, et al. Telemedicine and dermatology hospital consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-centre observational study on resource utilization and conversion to in-person consultations during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2022;36:E323-E325. doi:10.1111/jdv.17898

5. Marasca C, Annunziata MC, Camela E, et al. Teledermatology and inflammatory skin conditions during COVID-19 era: new perspectives and applications. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1511. doi:10.3390/jcm11061511

6. Chiricozzi A, Talamonti M, De Simone C, et al. Management of patients with atopic dermatitis undergoing systemic therapy during COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: data from the DA-COVID-19 registry. Allergy. 2021;76:1813-1824. doi:10.1111/all.14767

Practice Points

- The landscape of dermatology has seen major changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as many patients now utilize telemedicine to receive care.

- Understanding accessibility to in-person care for patients with atopic dermatitis during the COVID-19 pandemic can assist with the development of methods to enhance management.

Aberrant Expression of CD56 in Metastatic Malignant Melanoma

To the Editor:

Many types of neoplasms can show aberrant immunoreactivity or unexpected expression of markers.1 Malignant melanoma is a tumor that can show not only aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns but also notable histologic diversity,1,2 which often makes the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.2

The incidence of malignant melanoma continues to grow.3 Maintaining a high degree of suspicion for this disease, recognizing its heterogeneity and divergent differentiation, and knowing potential aberrant immunohistochemical staining patterns are imperative for accurate diagnosis.

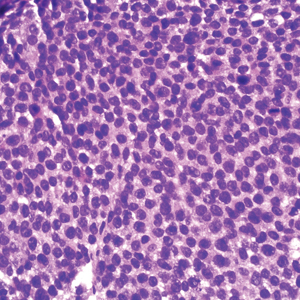

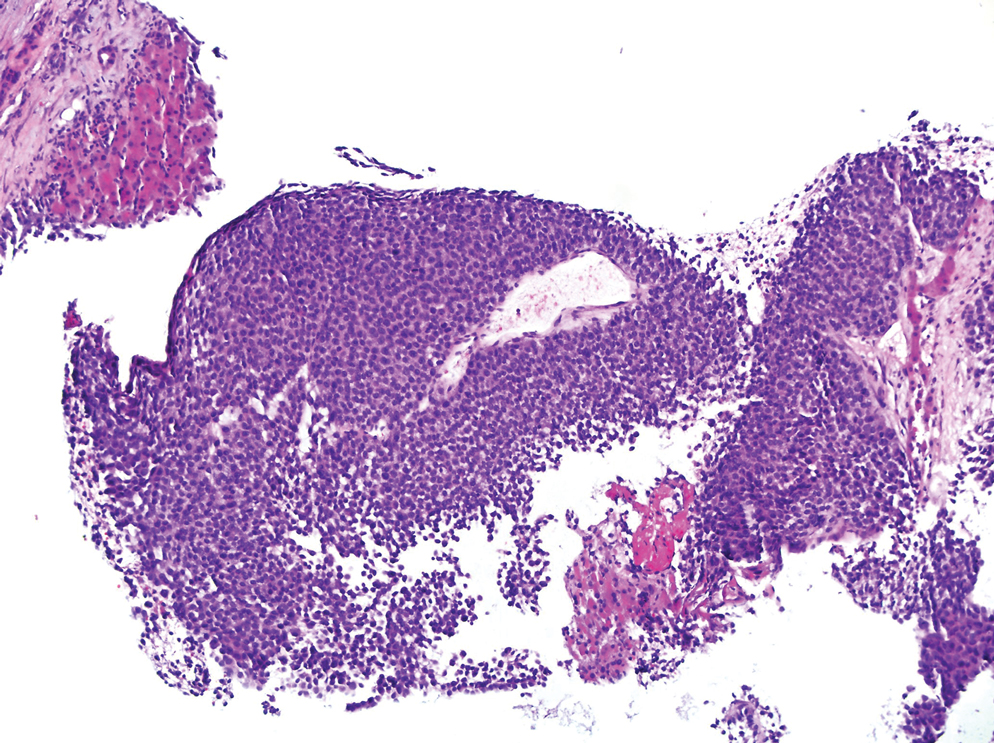

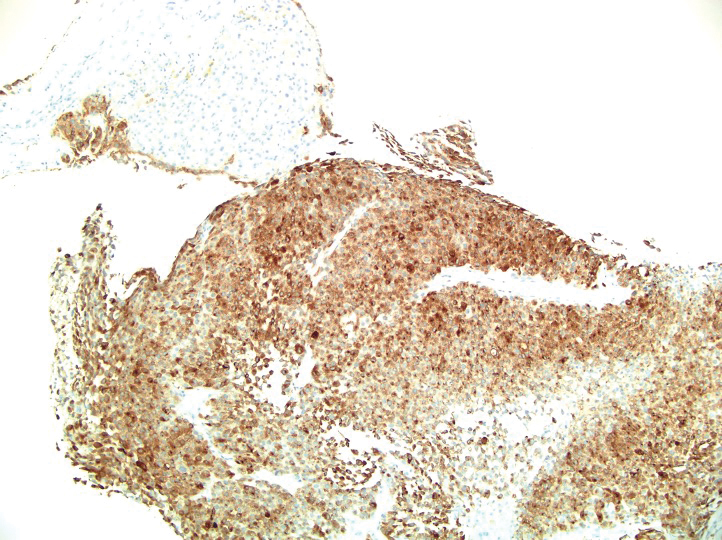

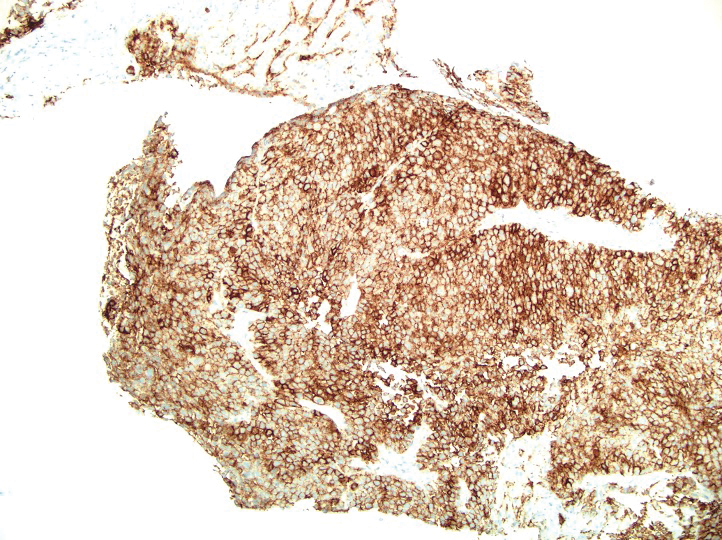

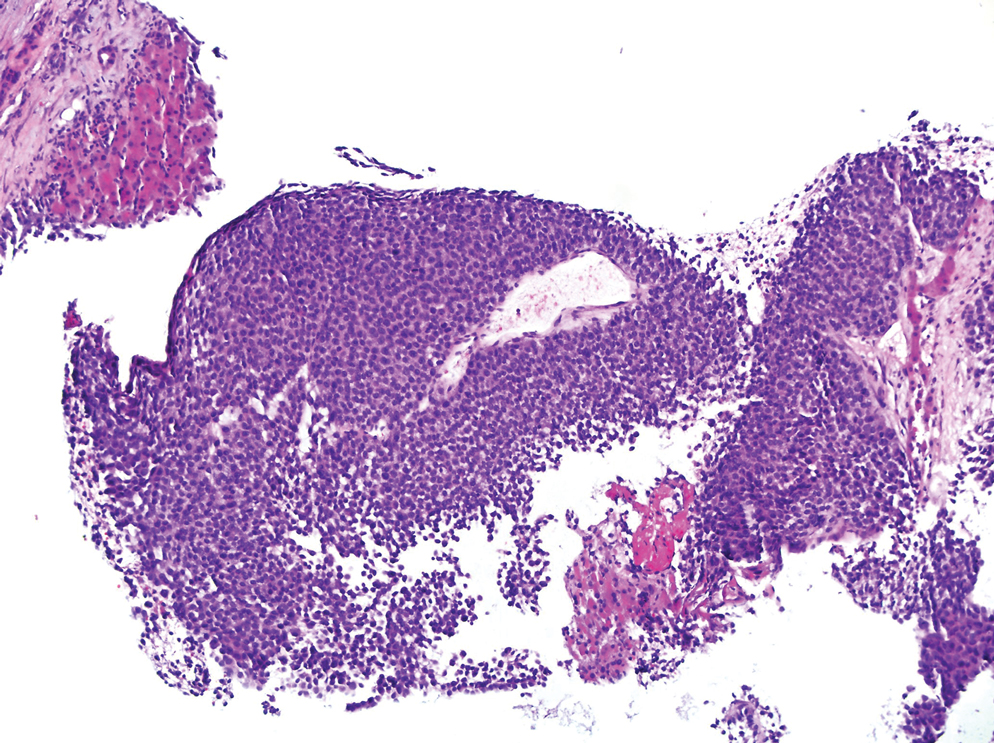

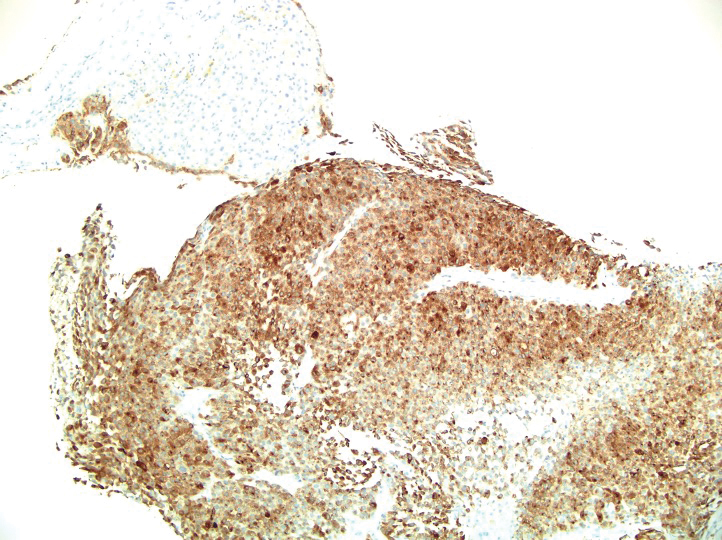

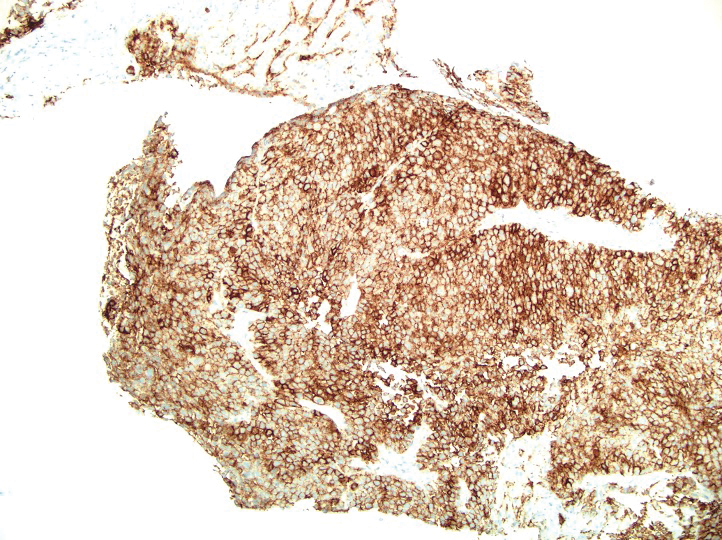

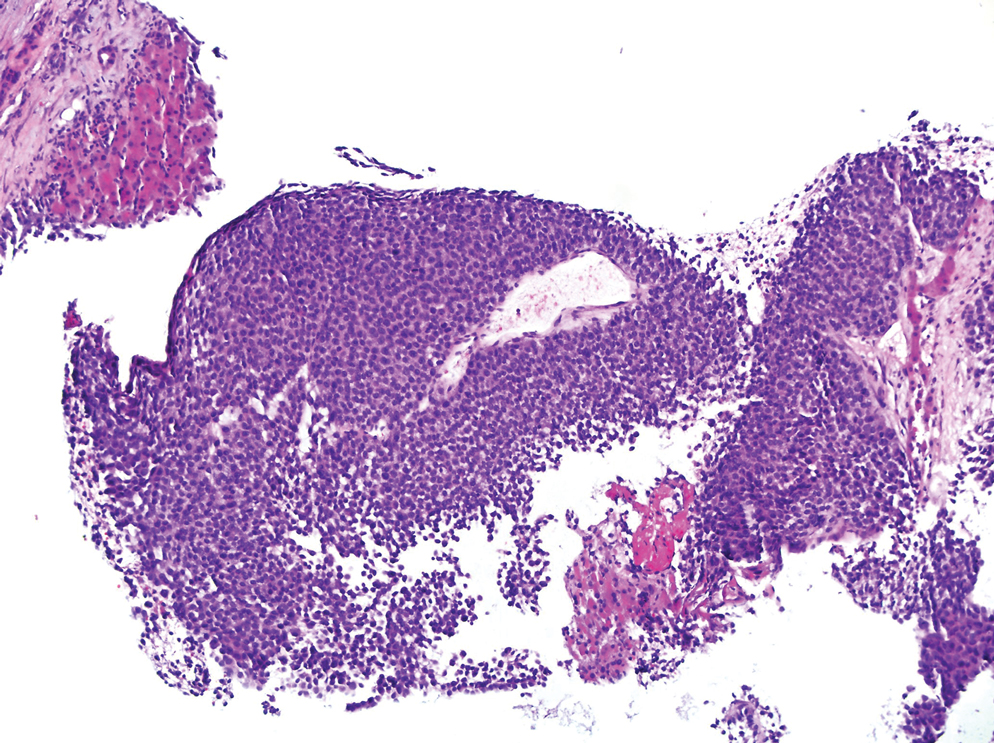

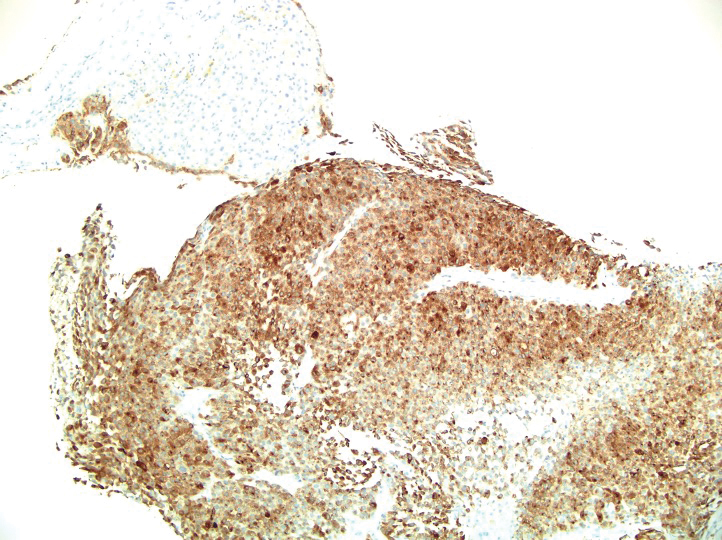

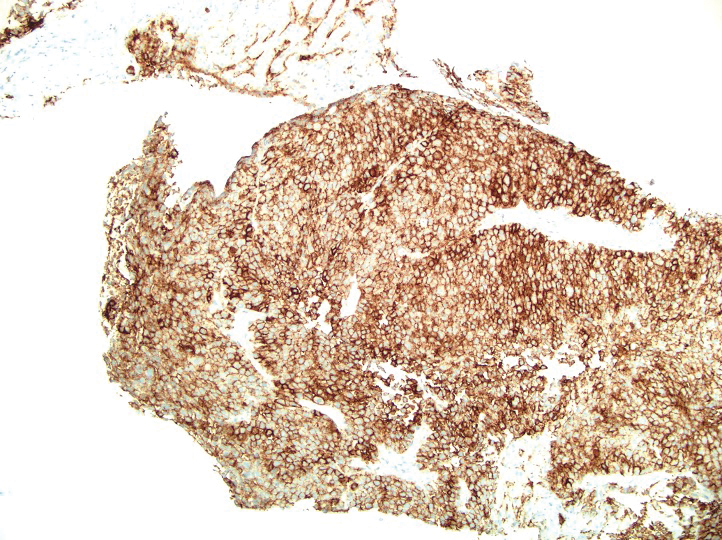

A 36-year-old man presented to a primary care physician with right-sided chest pain, upper and lower back aches, bilateral hip pain, neck pain, headache, night sweats, chills, and nausea. After infectious causes were ruled out, he was placed on a steroid taper without improvement. He presented to the emergency department a few days later with muscle spasms and was found to also have diffuse abdominal tenderness and guarding. The patient’s medical history was noncontributory; he was a lifelong nonsmoker. Laboratory studies revealed elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase and C-reactive protein. Computed tomography of the chest and abdomen revealed innumerable liver and lung lesions that were suspicious for metastatic malignancy. A liver biopsy revealed nests and sheets of metastatic tumor with pleomorphic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and areas of intranuclear clearing (Figures 1 and 2). Immunohistochemical staining was performed to further characterize the tumor. Neoplastic cells were positive for MART-1 (also known as Melan-A and melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells)(Figure 3), SOX10, S-100, HMB-45, and vimentin. Nonspecific staining with CD56 (Figure 4), a neuroendocrine marker, also was noted; however, the neoplasm was negative for synaptophysin, another neuroendocrine marker. Other markers for which staining was negative included pan-keratin, CD138 (syndecan-1), desmin, placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), inhibin, OCT-4, cytokeratin 7, and cytokeratin 20. This staining pattern was compatible with metastatic melanoma with aberrant CD56 expression.

BRAF V600E immunohistochemical staining also was performed and showed strong and diffuse positivity within neoplastic cells. A subsequent positron emission tomography scan revealed widespread metastatic disease involving the lungs, liver, spleen, and bones. The patient did not have a history of an excised skin lesion; no primary cutaneous or mucosal lesions were identified.

The patient was started on targeted therapy with trametinib, a mitogen-activated extracellular signal-related kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, and dabrafenib, a BRAF inhibitor. The disease continued to progress; he developed extensive leptomeningeal metastatic disease for which palliative radiation therapy was administered. The patient died 4 months after the initial diagnosis.

More than 90% of melanoma cases are of cutaneous origin; however, 4% to 8% of cases present as a metastatic lesion in the absence of an identified primary lesion,4 similar to our patient. The diagnosis of melanoma often is challenging; the tumor can show notable histologic diversity and has the potential to express aberrant immunophenotypes.1,2 The histologic diversity of melanoma includes a variety of architectural patterns (eg, nests, trabeculae, fascicular, pseudoglandular, pseudopapillary, or pseudorosette patterns), cytomorphologic features, and stromal changes. Cytomorphologic features of melanoma can be large pleomorphic cells; small cells; spindle cells; clear cells; signet-ring cells; and rhabdoid, plasmacytoid, and balloon cells.5

Melanoma can mimic carcinoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, benign stromal tumors, plasmacytoma, and germ-cell tumors.5 Nuclei can binucleated, multinucleated, or lobated and may contain inclusions or grooves. Stroma may become myxoid or desmoplastic in appearance or rarely show granulomatous inflammation or osteoclastic giant cells.5 These variations render the diagnosis of melanoma challenging and ultimately can lead to diagnostic uncertainty.

Melanomas typically express MART-1, HMB-45, S-100, tyrosinase, NK1C3, vimentin, and neuron-specific enolase. However, melanoma is among the many neoplasms that sometimes exhibit aberrant immunoreactivity and differentiation toward nonmelanocytic elements.6 The most commonly expressed immunophenotypic aberration is cytokeratin, especially the low-molecular-weight keratin marker CAM5.2.5 CAM5.2 positivity also is seen more often in metastatic melanoma. Melanomas rarely express other intermediate filaments, including desmin, neurofilament protein, and glial fibrillary acidic protein; expression of smooth-muscle actin is rare.5