User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

New update focuses on NAFLD in lean people

Ongoing follow-up and lifestyle interventions are needed in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), suggests a panel of experts in a recent review.

They also urge screening for NAFLD in individuals who are older than 40 years with type 2 diabetes, even if they are not overweight.

NAFLD is a leading cause of chronic liver disease that affects more than 25% of the United States and worldwide populations, note lead author Michelle T. Long, MD, Boston Medical Center, Boston University, and colleagues.

They add that around one-quarter of those affected have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality due to complications of liver cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Although NAFLD occurs primarily in individuals with obesity or type 2 diabetes, between 7%-20% have a lean body habitus, they write.

There are differences in rates of disease progression, associated conditions, and diagnostic and management approaches between lean and non-lean patients, the authors note, but there is limited guidance on the appropriate clinical evaluation of the former group.

The American Gastroenterological Association therefore commissioned an expert review to provide best practice advice on key clinical issues relating to the diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment of NAFLD in lean individuals.

Their review was published online in Gastroenterology.

Evidence-based approaches

The 15 best practice advice statements covered a wide range of clinical areas, first defining lean as a body mass index (BMI) less than 25 in non-Asian persons and less than 23 in Asian persons.

The authors go on to stipulate, for example, that lean individuals in the general population should not be screened for NAFLD but that screening should be considered for individuals older than 40 years with type 2 diabetes.

More broadly, they write that the condition should be considered in lean individuals with metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, as well as elevated values on liver biochemical tests or incidentally noted hepatic steatosis.

After other causes of liver diseases are ruled out, the authors note that clinicians should consider liver biopsy as the reference test if uncertainties remain about liver injury causes and/or liver fibrosis staging.

They also write that the NAFLD fibrosis score and Fibrosis-4 score, along with imaging techniques, may be used as alternatives to biopsy for staging and during follow-up.

The authors, who provide a diagnosis and management algorithm to aid clinicians, suggest that lean patients with NAFLD follow lifestyle interventions, such as exercise, diet modification, and avoidance of fructose- and sugar-sweetened drinks, to achieve weight loss of 3%-5%.

Vitamin E may be considered, they continue, in patients with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis but without type 2 diabetes or cirrhosis. Additionally, oral pioglitazone may be considered in lean persons with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis.

In contrast, they write that the role of glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors requires further investigation.

The advice also says that lean patients with NAFLD should be routinely evaluated for comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and risk-stratified for hepatic fibrosis to identify those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

For lean patients with NAFLD and clinical markers compatible with liver cirrhosis, twice-yearly surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is also advised.

Fatty liver disease in lean people with metabolic conditions

Approached for comment, Liyun Yuan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of clinical medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said it is very important to have uniform guidelines for general practitioners and other specialties on NAFLD in lean individuals.

Dr. Yuan, who was not involved in the review, told this news organization that it is crucial to raise awareness of NAFLD, just like awareness of breast cancer screening among women of a certain age was increased, so that individuals are screened for metabolic conditions regardless of whether they have obesity or overweight.

Zobair Younossi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Inova Campus, Falls Church, Va., added that there is a lack of awareness that NAFLD occurs in lean individuals, especially in those who have diabetes.

He said in an interview that although it is accurate to define individuals as being lean in terms of their BMI, the best way is to look not only at BMI but also at waist circumference.

Dr. Younossi said that he and his colleagues have shown that when BMI is combined with waist circumference, the prediction of mortality risk in NAFLD is affected, such that lean individuals with an obese waist circumference have a higher risk for all-cause mortality.

Dr. Long is supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Award, Boston University School of Medicine Department of Medicine Career Investment Award, and Boston University Clinical Translational Science Institute. Dr. Long declares relationships with Novo Nordisk, Echosens Corporation, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Yuan declares relationships with Genfit, Intercept, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Younossi declares no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*This article was updated on July 27, 2022.

Ongoing follow-up and lifestyle interventions are needed in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), suggests a panel of experts in a recent review.

They also urge screening for NAFLD in individuals who are older than 40 years with type 2 diabetes, even if they are not overweight.

NAFLD is a leading cause of chronic liver disease that affects more than 25% of the United States and worldwide populations, note lead author Michelle T. Long, MD, Boston Medical Center, Boston University, and colleagues.

They add that around one-quarter of those affected have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality due to complications of liver cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Although NAFLD occurs primarily in individuals with obesity or type 2 diabetes, between 7%-20% have a lean body habitus, they write.

There are differences in rates of disease progression, associated conditions, and diagnostic and management approaches between lean and non-lean patients, the authors note, but there is limited guidance on the appropriate clinical evaluation of the former group.

The American Gastroenterological Association therefore commissioned an expert review to provide best practice advice on key clinical issues relating to the diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment of NAFLD in lean individuals.

Their review was published online in Gastroenterology.

Evidence-based approaches

The 15 best practice advice statements covered a wide range of clinical areas, first defining lean as a body mass index (BMI) less than 25 in non-Asian persons and less than 23 in Asian persons.

The authors go on to stipulate, for example, that lean individuals in the general population should not be screened for NAFLD but that screening should be considered for individuals older than 40 years with type 2 diabetes.

More broadly, they write that the condition should be considered in lean individuals with metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, as well as elevated values on liver biochemical tests or incidentally noted hepatic steatosis.

After other causes of liver diseases are ruled out, the authors note that clinicians should consider liver biopsy as the reference test if uncertainties remain about liver injury causes and/or liver fibrosis staging.

They also write that the NAFLD fibrosis score and Fibrosis-4 score, along with imaging techniques, may be used as alternatives to biopsy for staging and during follow-up.

The authors, who provide a diagnosis and management algorithm to aid clinicians, suggest that lean patients with NAFLD follow lifestyle interventions, such as exercise, diet modification, and avoidance of fructose- and sugar-sweetened drinks, to achieve weight loss of 3%-5%.

Vitamin E may be considered, they continue, in patients with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis but without type 2 diabetes or cirrhosis. Additionally, oral pioglitazone may be considered in lean persons with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis.

In contrast, they write that the role of glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors requires further investigation.

The advice also says that lean patients with NAFLD should be routinely evaluated for comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and risk-stratified for hepatic fibrosis to identify those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

For lean patients with NAFLD and clinical markers compatible with liver cirrhosis, twice-yearly surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is also advised.

Fatty liver disease in lean people with metabolic conditions

Approached for comment, Liyun Yuan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of clinical medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said it is very important to have uniform guidelines for general practitioners and other specialties on NAFLD in lean individuals.

Dr. Yuan, who was not involved in the review, told this news organization that it is crucial to raise awareness of NAFLD, just like awareness of breast cancer screening among women of a certain age was increased, so that individuals are screened for metabolic conditions regardless of whether they have obesity or overweight.

Zobair Younossi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Inova Campus, Falls Church, Va., added that there is a lack of awareness that NAFLD occurs in lean individuals, especially in those who have diabetes.

He said in an interview that although it is accurate to define individuals as being lean in terms of their BMI, the best way is to look not only at BMI but also at waist circumference.

Dr. Younossi said that he and his colleagues have shown that when BMI is combined with waist circumference, the prediction of mortality risk in NAFLD is affected, such that lean individuals with an obese waist circumference have a higher risk for all-cause mortality.

Dr. Long is supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Award, Boston University School of Medicine Department of Medicine Career Investment Award, and Boston University Clinical Translational Science Institute. Dr. Long declares relationships with Novo Nordisk, Echosens Corporation, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Yuan declares relationships with Genfit, Intercept, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Younossi declares no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*This article was updated on July 27, 2022.

Ongoing follow-up and lifestyle interventions are needed in lean patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), suggests a panel of experts in a recent review.

They also urge screening for NAFLD in individuals who are older than 40 years with type 2 diabetes, even if they are not overweight.

NAFLD is a leading cause of chronic liver disease that affects more than 25% of the United States and worldwide populations, note lead author Michelle T. Long, MD, Boston Medical Center, Boston University, and colleagues.

They add that around one-quarter of those affected have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality due to complications of liver cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Although NAFLD occurs primarily in individuals with obesity or type 2 diabetes, between 7%-20% have a lean body habitus, they write.

There are differences in rates of disease progression, associated conditions, and diagnostic and management approaches between lean and non-lean patients, the authors note, but there is limited guidance on the appropriate clinical evaluation of the former group.

The American Gastroenterological Association therefore commissioned an expert review to provide best practice advice on key clinical issues relating to the diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment of NAFLD in lean individuals.

Their review was published online in Gastroenterology.

Evidence-based approaches

The 15 best practice advice statements covered a wide range of clinical areas, first defining lean as a body mass index (BMI) less than 25 in non-Asian persons and less than 23 in Asian persons.

The authors go on to stipulate, for example, that lean individuals in the general population should not be screened for NAFLD but that screening should be considered for individuals older than 40 years with type 2 diabetes.

More broadly, they write that the condition should be considered in lean individuals with metabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, as well as elevated values on liver biochemical tests or incidentally noted hepatic steatosis.

After other causes of liver diseases are ruled out, the authors note that clinicians should consider liver biopsy as the reference test if uncertainties remain about liver injury causes and/or liver fibrosis staging.

They also write that the NAFLD fibrosis score and Fibrosis-4 score, along with imaging techniques, may be used as alternatives to biopsy for staging and during follow-up.

The authors, who provide a diagnosis and management algorithm to aid clinicians, suggest that lean patients with NAFLD follow lifestyle interventions, such as exercise, diet modification, and avoidance of fructose- and sugar-sweetened drinks, to achieve weight loss of 3%-5%.

Vitamin E may be considered, they continue, in patients with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis but without type 2 diabetes or cirrhosis. Additionally, oral pioglitazone may be considered in lean persons with biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis.

In contrast, they write that the role of glucagonlike peptide 1 agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors requires further investigation.

The advice also says that lean patients with NAFLD should be routinely evaluated for comorbid conditions, such as type 2 diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and risk-stratified for hepatic fibrosis to identify those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

For lean patients with NAFLD and clinical markers compatible with liver cirrhosis, twice-yearly surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is also advised.

Fatty liver disease in lean people with metabolic conditions

Approached for comment, Liyun Yuan, MD, PhD, assistant professor of clinical medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, said it is very important to have uniform guidelines for general practitioners and other specialties on NAFLD in lean individuals.

Dr. Yuan, who was not involved in the review, told this news organization that it is crucial to raise awareness of NAFLD, just like awareness of breast cancer screening among women of a certain age was increased, so that individuals are screened for metabolic conditions regardless of whether they have obesity or overweight.

Zobair Younossi, MD, MPH, professor of medicine, Virginia Commonwealth University, Inova Campus, Falls Church, Va., added that there is a lack of awareness that NAFLD occurs in lean individuals, especially in those who have diabetes.

He said in an interview that although it is accurate to define individuals as being lean in terms of their BMI, the best way is to look not only at BMI but also at waist circumference.

Dr. Younossi said that he and his colleagues have shown that when BMI is combined with waist circumference, the prediction of mortality risk in NAFLD is affected, such that lean individuals with an obese waist circumference have a higher risk for all-cause mortality.

Dr. Long is supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Gilead Sciences Research Scholars Award, Boston University School of Medicine Department of Medicine Career Investment Award, and Boston University Clinical Translational Science Institute. Dr. Long declares relationships with Novo Nordisk, Echosens Corporation, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Yuan declares relationships with Genfit, Intercept, and Gilead Sciences. Dr. Younossi declares no relevant relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*This article was updated on July 27, 2022.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Children and COVID: Many parents see vaccine as the greater risk

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

New COVID-19 cases rose for the second week in a row as cumulative cases among U.S. children passed the 14-million mark, but a recent survey shows that more than half of parents believe that the vaccine is a greater risk to children under age 5 years than the virus.

In a Kaiser Family Foundation survey conducted July 7-17, 53% of parents with children aged 6 months to 5 years said that the vaccine is “a bigger risk to their child’s health than getting infected with COVID-19, compared to 44% who say getting infected is the bigger risk,” KFF reported July 26.

More than 4 out of 10 of respondents (43%) said that they will “definitely not” get their eligible children vaccinated, while only 7% said that their children had already received it and 10% said their children would get it as soon as possible, according to the KFF survey, which had an overall sample size of 1,847 adults, including an oversample of 471 parents of children under age 5.

Vaccine initiation has been slow in the first month since it was approved for the youngest children. Just 2.8% of all eligible children under age 5 had received an initial dose as of July 19, compared with first-month uptake figures of more than 18% for the 5- to 11-year-olds and 27% for those aged 12-15, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The current rates for vaccination in those aged 5 and older look like this: 70.2% of 12- to 17-year-olds have received at least one dose, versus 37.1% of those aged 5-11. Just over 60% of the older children were fully vaccinated as of July 19, as were 30.2% of the 5- to 11-year-olds, the CDC reported on its COVID Data Tracker.

Number of new cases hits 2-month high

Despite the vaccine, SARS-CoV-2 and its various mutations have continued with their summer travels. With 92,000 newly infected children added for the week of July 15-21, there have now been a total of 14,003,497 pediatric cases reported since the start of the pandemic, which works out to 18.6% of cases in all ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

The 92,000 new cases represent an increase of almost 22% over the previous week and mark the highest 1-week count since May, when the total passed 100,000 for 2 consecutive weeks. More recently the trend had seemed more stable as weekly cases dropped twice and rose twice as the total hovered around 70,000, based on the data collected by the AAP and CHA from state and territorial health departments.

A different scenario has played out for emergency department visits and hospital admissions, which have risen steadily since the beginning of April. The admission rate for children aged 0-17, which was just 0.13 new patients per 100,000 population on April 11, was up to 0.44 per 100,000 on July 21. By comparison, the highest rate reached last year during the Delta surge was 0.47 per 100,000, based on CDC data.

The 7-day average of emergency dept. visits among the youngest age group, 0-11 years, shows the same general increase as hospital admissions, but the older children have diverged form that path (see graph). For those aged 12-15 and 16-17, hospitalizations started dropping in late May and into mid-June before climbing again, although more slowly than for the youngest group, the CDC data show.

The ED visit rate with diagnosed COVID among those aged 0-11, measured at 6.1% of all visits on July 19, is, in fact, considerably higher than at any time during the Delta surge last year, when it never passed 4.0%, although much lower than peak Omicron (14.1%). That 6.1% was also higher than any other age group on that day, adults included, the CDC said.

Boosting hypertension screening, treatment would cut global mortality 7%

If 80% of individuals with hypertension were screened, 80% received treatment, and 80% then reached guideline-specified targets, up to 200 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 130 million deaths could be averted by 2050, a modeling study suggests.

Achievement of the 80-80-80 target “could be one of the single most important global public health accomplishments of the coming decades,” according to the authors.

“We need to reprioritize hypertension care in our practices,” principal investigator David A. Watkins, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization. “Only about one in five persons with hypertension around the world has their blood pressure well controlled. Oftentimes, clinicians are focused on addressing patients’ other health needs, many of which can be pressing in the short term, and we forget to talk about blood pressure, which has more than earned its reputation as ‘the silent killer.’ ”

The modeling study was published online in Nature Medicine, with lead author Sarah J. Pickersgill, MPH, also from the University of Washington.

Two interventions, three scenarios

Dr. Watkins and colleagues based their analysis on two approaches to blood pressure (BP) control shown to be beneficial: drug treatment to a systolic BP of either 130 mm Hg or 140 mm Hg or less, depending on local guidelines, and dietary sodium reduction, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

The team modeled the impacts of these interventions in 182 countries according to three scenarios:

- Business as usual (control): allowing hypertension to increase at historic rates of change and mean sodium intake to remain at current levels

- Progress: matching historically high-performing countries (for example, accelerating hypertension control by about 3% per year at intermediate levels of intervention coverage) while lowering mean sodium intake by 15% by 2030

- Aspirational: hypertension control achieved faster than historically high-performing countries (about 4% per year) and mean sodium intake decreased by 30% by 2027

The analysis suggests that in the progressive scenario, all countries could achieve 80-80-80 targets by 2050 and most countries by 2040; the aspirational scenario would have all countries meeting them by 2040. That would result in reductions in all-cause mortality of 4%-7% (76 million to 130 million deaths averted) with progressive and aspirational interventions, respectively, compared with the control scenario.

There would also be a slower rise in expected CVD from population growth and aging (110 million to 200 million cases averted). That is, the probability of dying from any CVD cause between the ages of 30 and 80 years would be reduced by 16% in the progressive scenario and 26% in the aspirational scenario.

Of note, about 83%-85% of the potential mortality reductions would result from scaling up hypertension treatment in the progressive and aspirational scenarios, respectively, with the remaining 15%-17% coming from sodium reduction, the researchers state.

Further, they propose, scaling up BP interventions could reduce CVD inequalities across countries, with low-income and lower-middle-income countries likely experiencing the largest reductions in disease rates and mortality.

Implementation barriers

“Health systems in many low- and middle-income countries have not traditionally been set up to succeed in chronic disease management in primary care,” Dr. Watkins noted. For interventions to be successful, he said, “several barriers need to be addressed, including: low population awareness of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which leads to low rates of screening and treatment; high out-of-pocket cost and low availability of medicines for chronic diseases; and need for adherence support and provider incentives for improving quality of chronic disease care in primary care settings.”

“Based on the analysis, achieving the 80-80-80 seems feasible, though actually getting there may be much more complicated. I wonder whether countries have the resources to implement the needed policies,” Rodrigo M. Carrillo-Larco, MD, researcher, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, told this news organization.

“It may be challenging, particularly after COVID-19, which revealed deficiencies in many health care systems, and care for hypertension may have been disturbed,” said Dr. Carrillo-Larco, who is not connected with the analysis.

That said, simplified BP screening approaches could help maximize the number of people screened overall, potentially identifying those with hypertension and raising awareness, he proposed. His team’s recent study showed that such approaches vary from country to country but are generally reliable and can be used effectively for population screening.

In addition, Dr. Carrillo-Larco said, any efforts by clinicians to improve adherence and help patients achieve BP control “would also have positive effects at the population level.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with additional funding by a grant to Dr. Watkins from Resolve to Save Lives. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If 80% of individuals with hypertension were screened, 80% received treatment, and 80% then reached guideline-specified targets, up to 200 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 130 million deaths could be averted by 2050, a modeling study suggests.

Achievement of the 80-80-80 target “could be one of the single most important global public health accomplishments of the coming decades,” according to the authors.

“We need to reprioritize hypertension care in our practices,” principal investigator David A. Watkins, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization. “Only about one in five persons with hypertension around the world has their blood pressure well controlled. Oftentimes, clinicians are focused on addressing patients’ other health needs, many of which can be pressing in the short term, and we forget to talk about blood pressure, which has more than earned its reputation as ‘the silent killer.’ ”

The modeling study was published online in Nature Medicine, with lead author Sarah J. Pickersgill, MPH, also from the University of Washington.

Two interventions, three scenarios

Dr. Watkins and colleagues based their analysis on two approaches to blood pressure (BP) control shown to be beneficial: drug treatment to a systolic BP of either 130 mm Hg or 140 mm Hg or less, depending on local guidelines, and dietary sodium reduction, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

The team modeled the impacts of these interventions in 182 countries according to three scenarios:

- Business as usual (control): allowing hypertension to increase at historic rates of change and mean sodium intake to remain at current levels

- Progress: matching historically high-performing countries (for example, accelerating hypertension control by about 3% per year at intermediate levels of intervention coverage) while lowering mean sodium intake by 15% by 2030

- Aspirational: hypertension control achieved faster than historically high-performing countries (about 4% per year) and mean sodium intake decreased by 30% by 2027

The analysis suggests that in the progressive scenario, all countries could achieve 80-80-80 targets by 2050 and most countries by 2040; the aspirational scenario would have all countries meeting them by 2040. That would result in reductions in all-cause mortality of 4%-7% (76 million to 130 million deaths averted) with progressive and aspirational interventions, respectively, compared with the control scenario.

There would also be a slower rise in expected CVD from population growth and aging (110 million to 200 million cases averted). That is, the probability of dying from any CVD cause between the ages of 30 and 80 years would be reduced by 16% in the progressive scenario and 26% in the aspirational scenario.

Of note, about 83%-85% of the potential mortality reductions would result from scaling up hypertension treatment in the progressive and aspirational scenarios, respectively, with the remaining 15%-17% coming from sodium reduction, the researchers state.

Further, they propose, scaling up BP interventions could reduce CVD inequalities across countries, with low-income and lower-middle-income countries likely experiencing the largest reductions in disease rates and mortality.

Implementation barriers

“Health systems in many low- and middle-income countries have not traditionally been set up to succeed in chronic disease management in primary care,” Dr. Watkins noted. For interventions to be successful, he said, “several barriers need to be addressed, including: low population awareness of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which leads to low rates of screening and treatment; high out-of-pocket cost and low availability of medicines for chronic diseases; and need for adherence support and provider incentives for improving quality of chronic disease care in primary care settings.”

“Based on the analysis, achieving the 80-80-80 seems feasible, though actually getting there may be much more complicated. I wonder whether countries have the resources to implement the needed policies,” Rodrigo M. Carrillo-Larco, MD, researcher, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, told this news organization.

“It may be challenging, particularly after COVID-19, which revealed deficiencies in many health care systems, and care for hypertension may have been disturbed,” said Dr. Carrillo-Larco, who is not connected with the analysis.

That said, simplified BP screening approaches could help maximize the number of people screened overall, potentially identifying those with hypertension and raising awareness, he proposed. His team’s recent study showed that such approaches vary from country to country but are generally reliable and can be used effectively for population screening.

In addition, Dr. Carrillo-Larco said, any efforts by clinicians to improve adherence and help patients achieve BP control “would also have positive effects at the population level.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with additional funding by a grant to Dr. Watkins from Resolve to Save Lives. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

If 80% of individuals with hypertension were screened, 80% received treatment, and 80% then reached guideline-specified targets, up to 200 million cases of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and 130 million deaths could be averted by 2050, a modeling study suggests.

Achievement of the 80-80-80 target “could be one of the single most important global public health accomplishments of the coming decades,” according to the authors.

“We need to reprioritize hypertension care in our practices,” principal investigator David A. Watkins, MD, MPH, University of Washington, Seattle, told this news organization. “Only about one in five persons with hypertension around the world has their blood pressure well controlled. Oftentimes, clinicians are focused on addressing patients’ other health needs, many of which can be pressing in the short term, and we forget to talk about blood pressure, which has more than earned its reputation as ‘the silent killer.’ ”

The modeling study was published online in Nature Medicine, with lead author Sarah J. Pickersgill, MPH, also from the University of Washington.

Two interventions, three scenarios

Dr. Watkins and colleagues based their analysis on two approaches to blood pressure (BP) control shown to be beneficial: drug treatment to a systolic BP of either 130 mm Hg or 140 mm Hg or less, depending on local guidelines, and dietary sodium reduction, as recommended by the World Health Organization.

The team modeled the impacts of these interventions in 182 countries according to three scenarios:

- Business as usual (control): allowing hypertension to increase at historic rates of change and mean sodium intake to remain at current levels

- Progress: matching historically high-performing countries (for example, accelerating hypertension control by about 3% per year at intermediate levels of intervention coverage) while lowering mean sodium intake by 15% by 2030

- Aspirational: hypertension control achieved faster than historically high-performing countries (about 4% per year) and mean sodium intake decreased by 30% by 2027

The analysis suggests that in the progressive scenario, all countries could achieve 80-80-80 targets by 2050 and most countries by 2040; the aspirational scenario would have all countries meeting them by 2040. That would result in reductions in all-cause mortality of 4%-7% (76 million to 130 million deaths averted) with progressive and aspirational interventions, respectively, compared with the control scenario.

There would also be a slower rise in expected CVD from population growth and aging (110 million to 200 million cases averted). That is, the probability of dying from any CVD cause between the ages of 30 and 80 years would be reduced by 16% in the progressive scenario and 26% in the aspirational scenario.

Of note, about 83%-85% of the potential mortality reductions would result from scaling up hypertension treatment in the progressive and aspirational scenarios, respectively, with the remaining 15%-17% coming from sodium reduction, the researchers state.

Further, they propose, scaling up BP interventions could reduce CVD inequalities across countries, with low-income and lower-middle-income countries likely experiencing the largest reductions in disease rates and mortality.

Implementation barriers

“Health systems in many low- and middle-income countries have not traditionally been set up to succeed in chronic disease management in primary care,” Dr. Watkins noted. For interventions to be successful, he said, “several barriers need to be addressed, including: low population awareness of chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes, which leads to low rates of screening and treatment; high out-of-pocket cost and low availability of medicines for chronic diseases; and need for adherence support and provider incentives for improving quality of chronic disease care in primary care settings.”

“Based on the analysis, achieving the 80-80-80 seems feasible, though actually getting there may be much more complicated. I wonder whether countries have the resources to implement the needed policies,” Rodrigo M. Carrillo-Larco, MD, researcher, department of epidemiology and biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, told this news organization.

“It may be challenging, particularly after COVID-19, which revealed deficiencies in many health care systems, and care for hypertension may have been disturbed,” said Dr. Carrillo-Larco, who is not connected with the analysis.

That said, simplified BP screening approaches could help maximize the number of people screened overall, potentially identifying those with hypertension and raising awareness, he proposed. His team’s recent study showed that such approaches vary from country to country but are generally reliable and can be used effectively for population screening.

In addition, Dr. Carrillo-Larco said, any efforts by clinicians to improve adherence and help patients achieve BP control “would also have positive effects at the population level.”

The study was supported by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, with additional funding by a grant to Dr. Watkins from Resolve to Save Lives. No conflicts of interest were declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Multiple Fingerlike Projections on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

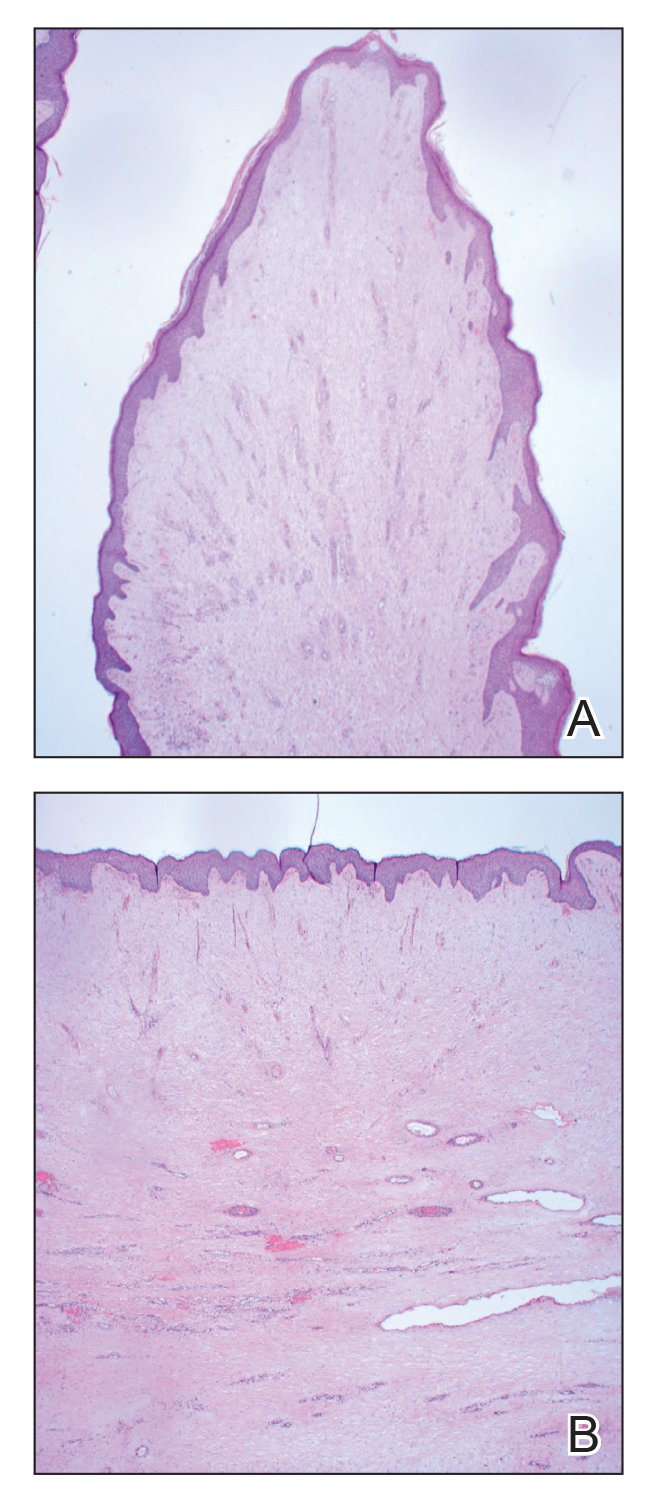

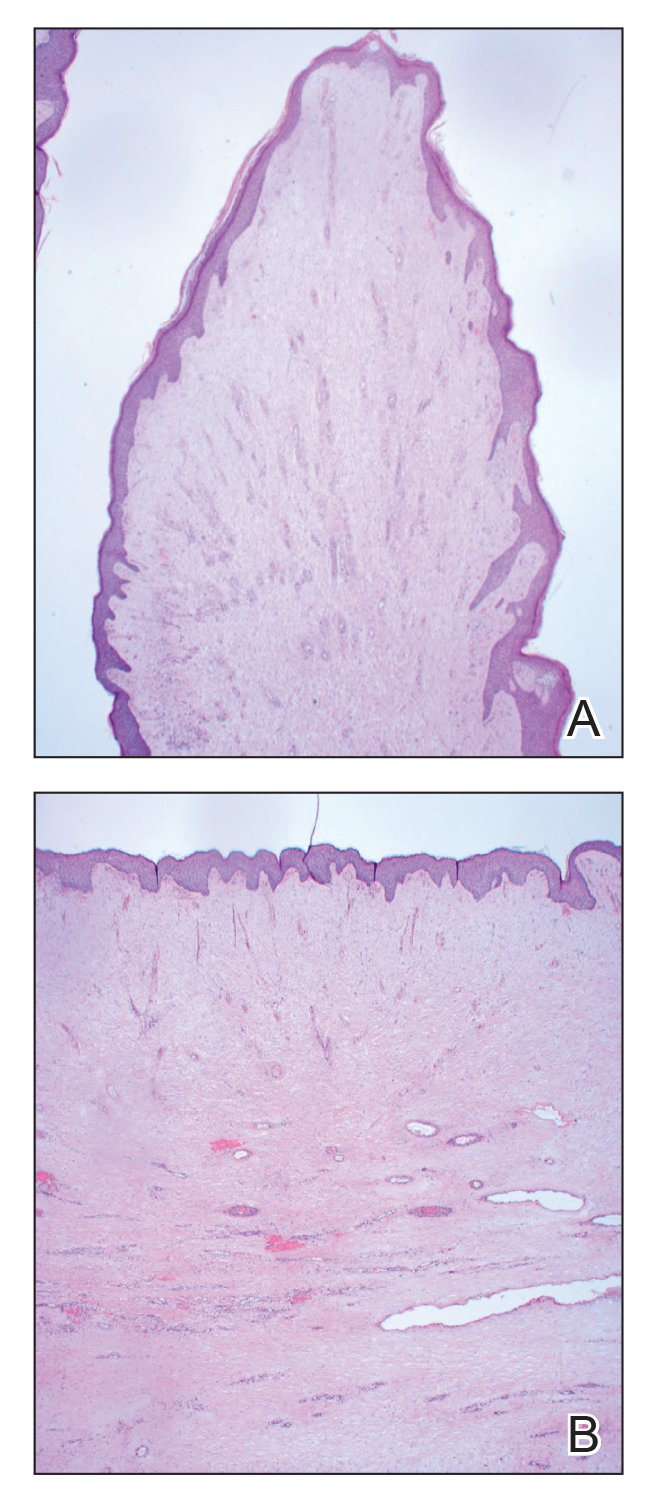

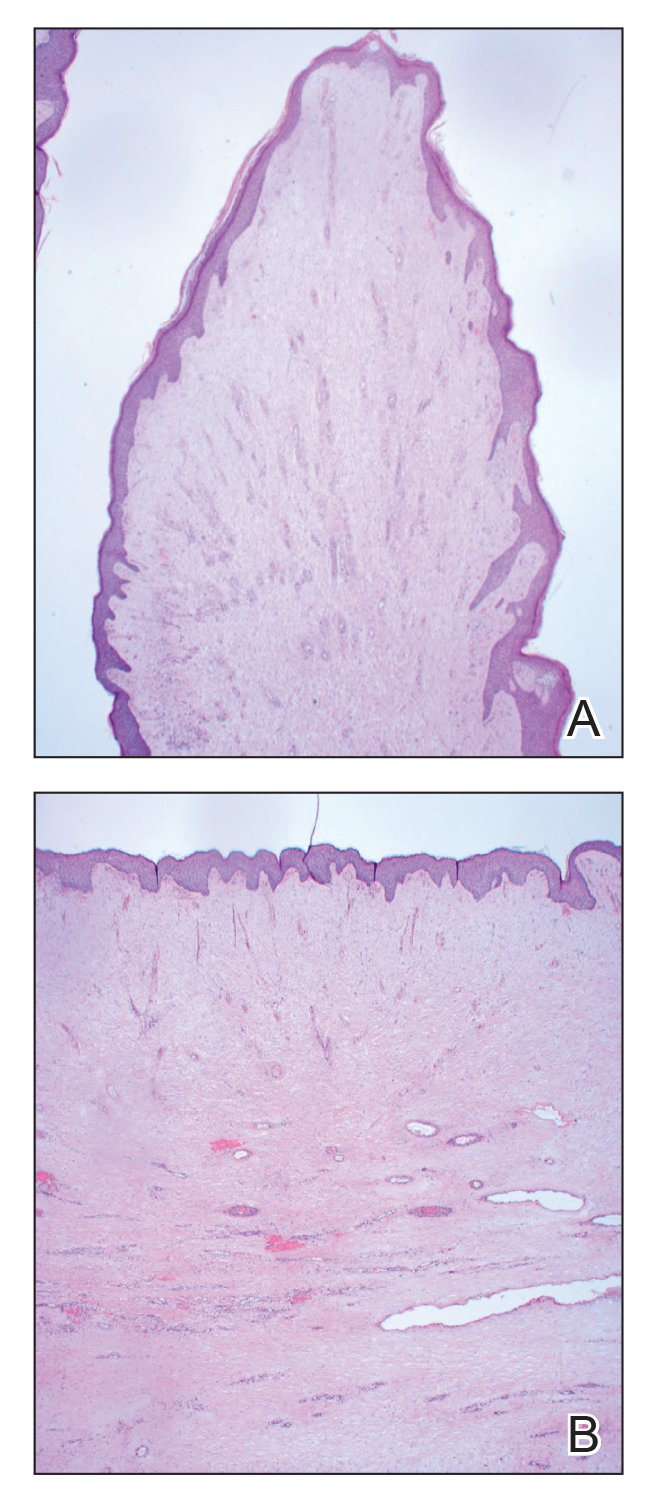

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

The Diagnosis: Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa

Histopathology revealed a benign fibroepithelial polyp demonstrating areas of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and focal papillomatosis (Figure, A). Increased superficial vessels with dilated lymphatics, stellate fibroblasts, edematous stroma, and plasmolymphocytosis also were noted (Figure, B). Clinical and histopathological findings led to a diagnosis of lymphedema papules in the setting of elephantiasis nostra verrucosa (ENV).

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of long-standing nonfilarial obstruction of lymphatic drainage leading to grotesque enlargement of the affected areas. Common cutaneous manifestations of ENV include nonpitting edema, dermal fibrosis, and extensive hyperkeratosis with verrucous and papillomatous lesions.1 In the beginning stages of ENV, the skin has a cobblestonelike appearance. As the disease progresses, the verrucous lesions continue to enlarge, giving the affected area a mossy appearance. Although less common, groupings of large papillomas similar to our patient’s presentation also can form.2 Ulcer formation is more likely to occur in advanced disease states, increasing the risk for bacterial and fungal colonization. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa classically affects the legs; however, this condition can develop in any area with chronic lymphedema. Cases of ENV involving the arms, abdomen, scrotum, and ear have been documented.3-5

The pathogenesis of ENV involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and fibrosis secondary to lymphostasis and inflammation.6 When interstitial fluid builds up in the affected region, the protein-rich fluid is believed to trigger fibrogenesis and increase macrophage, keratinocyte, and adipocyte activity.7 Because of this inflammatory process, dilation and fibrosis of the lymphatic channels develop. Lymphatic obstruction can have several etiologies, most notably infection and malignancy. Staphylococcal lymphangitis and erysipelas create fibrosis of the lymphatic system and are the main infectious causes of ENV.6 Large tumors or lymphomas are insidious causes of lymphatic obstruction and should be ruled out when investigating for ENV. Other risk factors include obesity, chronic venous insufficiency, surgery, trauma, radiation, and uncontrolled congestive heart failure.1,6,8

An ENV diagnosis is clinicopathologic, involving a comprehensive metabolic panel and complete blood cell count with differential. A biopsy is needed for pathologic confirmation and to rule out malignancy. Histologically, ENV is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, dermal fibrosis, hyperkeratosis of the epidermis, and dilated lymphatic vessels.6,8 Additional studies for diagnosis include wound and lymph node culture, Wood lamp examination, and lymphoscintigraphy.

Given the chronic and progressive nature of the disease, ENV is difficult to treat. There currently is no standard of treatment, but the mainstay of management involves reducing peripheral edema. Lifestyle changes including weight loss, extremity elevation, and increased ambulation are helpful first-line therapies.3 Compression of the affected extremity using stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices has proven to be beneficial with long-term use.7 Patients should be followed for wound care to prevent the infection of ulcers.2 Pharmacologic treatments include systemic retinoids, which have been shown to reduce the appearance of hyperkeratosis, verrucous lesions, and papillomatous nodules.6 Prophylactic antibiotics are reserved for advanced stages of disease or in patients with recurrent infections.2,7 In severe cases of ENV that are unresponsive to medical management, surgical intervention such as lymphatic anastomosis and debulking may be considered.9,10

Other diagnoses to consider for ENV include pretibial myxedema, lymphatic filariasis, Stewart-Treves syndrome, and papillomatosis cutis carcinoides. Pretibial myxedema is an uncommon dermatologic manifestation of Graves disease. It is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue characterized by hyperpigmentation, nonpitting edema, and nodules on the anterior leg. Histopathology shows increased hyaluronic acid and chondroitin as well as compression of dermal lymphatics.11

Filariasis is a parasitic infection caused by Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi or Brugia timori, and Onchocerca volvulus.6 This condition presents with elephantiasis of the affected extremities but should be considered in areas endemic for filarial parasites such as tropical and subtropical countries.12 Eosinophilia and identification of microfilaria in a peripheral blood smear would indicate parasitic infection. Stewart-Treves syndrome is a rare angiosarcoma that arises in areas of chronic lymphedema. This condition classically is seen on the upper extremities following a mastectomy with lymphadenectomy, lymph node irradiation, or both.

Stewart-Treves syndrome presents with coalescing purpuric macules and nodules that eventually coalesce into cutaneous masses. Histopathology reveals proliferating vascular channels that split apart dermal collagen with hyperchromatism and pleomorphism in the tumor endothelial cells that line these channels.13

Papillomatosis cutis carcinoides is a low-grade squamous cell carcinoma that occurs secondary to human papillomavirus commonly affecting the mouth, anogenital area, and the plantar surfaces of the feet. It presents with exophytic growths and ulcerated tumors that are unilateral and asymmetrical. The presence of blunt-shaped tumor projections extending deep into the dermis to form sinuses and keratin-filled cysts is characteristic of papillomatosis cutis carcinoides.14

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

- Dean SM, Zirwas MJ, Horst AV. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: an institutional analysis of 21 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64: 1104-1110. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.047

- Fife CE, Farrow W, Hebert AA, et al. Skin and wound care in lymphedema patients: a taxonomy, primer, and literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2017;30:305-318. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000520501.23702.82

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004; 3:446-448.

- Nakai K, Taoka R, Sugimoto M, et al. Genital elephantiasis possibly caused by chronic inguinal eczema with streptococcal infection. J Dermatol. 2019;46:E196-E198. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.14746

- Carlson JA, Mazza J, Kircher K, et al. Otophyma: a case report and review of the literature of lymphedema (elephantiasis) of the ear. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:67-72. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815cd937

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146. doi:10.2165/00128071-200809030-00001

- Yoho RM, Budny AM, Pea AS. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2006;96:442-444. doi:10.7547/0960442

- Yosipovitch G, DeVore A, Dawn A. Obesity and the skin: skin physiology and skin manifestations of obesity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:901-920. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.12.004

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30267.x

- Tiwari A, Cheng KS, Button M, et al. Differential diagnosis, investigation, and current treatment of lower limb lymphedema. Arch Surg. 2003;138:152-161. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.2.152

- Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. doi:10.2165 /00128071-200506050-00003

- Addiss DG, Brady MA. Morbidity management in the Global Programme to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis: a review of the scientific literature. Filaria J. 2007;6:2. doi:10.1186/1475-2883-6-2

- Bernia E, Rios-Viñuela E, Requena C. Stewart-Treves syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:721. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.0341

- Schwartz RA. Verrucous carcinoma of the skin and mucosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:1-24. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90177-9

A 61-year-old man presented with painful skin growths on the right pretibial region of several months’ duration. The patient reported pain due to friction between the lesions and underlying skin, leading to erosions. His medical history was remarkable for morbid obesity (body mass index of 62), chronic venous stasis, and chronic lymphedema. The patient was followed for wound care of venous stasis ulcers. Dermatologic examination revealed multiple 5- to 30-mm, flesh-colored, fingerlike projections on the right tibial region. A biopsy was obtained and submitted for histopathologic analysis.

The next blood pressure breakthrough: temporary tattoos

As scientists work on wearable technology that promises to revolutionize health care, researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University, College Station, are reporting a big win in the pursuit of one highly popular target: a noninvasive solution for continuous blood pressure monitoring at home.

Not only that, but this development comes in the surprising form of a temporary tattoo. That’s right: Just like the kind that children like to wear.

the researchers report in their new study.

“With this new technology, we are going to have an opportunity to understand how our blood pressure fluctuates during the day. We will be able to quantify how stress is impacting us,” says Roozbeh Jafari, PhD, a professor of biomedical engineering, electrical engineering, and computer science at Texas A&M, College Station, and a coauthor of the study.

Revealing the whole picture, not just dots

At-home blood pressure monitors have been around for many years now. They work just like the blood pressure machines doctors use at their office: You place your arm inside a cuff, press a button, feel a squeeze on your arm, and get a reading.

While results from this method are accurate, they are also just a moment in time. Our blood pressure can vary greatly throughout the day – especially among people who have labile hypertension, where blood pressure changes from one extreme to the other. So, looking at point-in-time readings is a bit like focusing on a few dots inside of a pointillism painting – one might miss the bigger picture.

Doctors may also find continuous monitoring useful for getting rid of false readings from “white coat syndrome.” Basically, this means a person’s blood pressure rises due to the anxiety of being in a doctor’s office but is not true hypertension.

Bottom line: The ability to monitor a person’s blood pressure continuously for hours or even days can provide clearer, and more accurate, insights into a person’s health.

How do health monitoring tattoos work?

Electronic tattoos for health monitoring are not completely new. John A. Rogers, PhD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, first put forth the idea of monitoring through temporary tattoos 12 years ago. Some concepts, such as UV monitoring tattoos, had already been adopted by scientists and put on the market. But the existing models weren’t suitable for monitoring blood pressure, according to Deji Akinwande, PhD, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Texas at Austin and another coauthor of the study.

“[UV monitoring tattoos] are very thick,” he says. “They create too much movement when used to measure blood pressure because they slide around.”

So, the Texas-based research team worked to develop an option that was slimmer and more stable.

“The key ingredient within e-tattoos is graphene,” says Dr. Akinwande.

Graphene is carbon that’s similar to what’s inside your graphite pencil. The material is conductive, meaning it can conduct small electrical currents through the skin. For blood pressure monitoring, graphene promotes bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), which is like the technology used in smart scales that measure body fat.

With e-tattoos, the thin layers of graphene stick to the skin and do not slide around, getting rid of “artifacts,” or bad data. The graphene e-tattoos can be worn on the skin for about a week – or roughly as long as the temporary tattoos kids love.

Once the graphene captures the raw data, a machine learning algorithm interprets the information and provides results in units used for measuring blood pressure: millimeters of mercury (mmHg), commonly referred to as blood pressure “points.”

How accurate are the results? The tests measured blood pressure within 0.2 ± 5.8 mmHg (systolic), 0.2 ± 4.5 mmHg (diastolic), and 0.1 ± 5.3 mmHg (mean arterial pressure). In other words: If this were a basketball player shooting baskets, the great majority of shots taken would be swishes and occasionally a few would hit the rim. That means good accuracy.

When will e-tattoos be available?

The teams of Dr. Jafari and Dr. Akinwande are working on a second generation of their e-tattoo that they expect to be available in the next 5 years.

The upgrade they envision will be smaller and compatible with smartwatches and phones that use Bluetooth technology and near-field communication (NFC) to transfer data and give it power. With these updates, e-tattoos for continuous blood pressure monitoring will be ready for clinical trials and mainstream use soon after.

“Everyone can benefit from knowing their blood pressure recordings,” Dr. Akinwande says. “It is not just for people at risk for hypertension but for others to proactively monitor their health, for stress and other factors.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As scientists work on wearable technology that promises to revolutionize health care, researchers from the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University, College Station, are reporting a big win in the pursuit of one highly popular target: a noninvasive solution for continuous blood pressure monitoring at home.

Not only that, but this development comes in the surprising form of a temporary tattoo. That’s right: Just like the kind that children like to wear.

the researchers report in their new study.

“With this new technology, we are going to have an opportunity to understand how our blood pressure fluctuates during the day. We will be able to quantify how stress is impacting us,” says Roozbeh Jafari, PhD, a professor of biomedical engineering, electrical engineering, and computer science at Texas A&M, College Station, and a coauthor of the study.

Revealing the whole picture, not just dots

At-home blood pressure monitors have been around for many years now. They work just like the blood pressure machines doctors use at their office: You place your arm inside a cuff, press a button, feel a squeeze on your arm, and get a reading.

While results from this method are accurate, they are also just a moment in time. Our blood pressure can vary greatly throughout the day – especially among people who have labile hypertension, where blood pressure changes from one extreme to the other. So, looking at point-in-time readings is a bit like focusing on a few dots inside of a pointillism painting – one might miss the bigger picture.

Doctors may also find continuous monitoring useful for getting rid of false readings from “white coat syndrome.” Basically, this means a person’s blood pressure rises due to the anxiety of being in a doctor’s office but is not true hypertension.

Bottom line: The ability to monitor a person’s blood pressure continuously for hours or even days can provide clearer, and more accurate, insights into a person’s health.

How do health monitoring tattoos work?

Electronic tattoos for health monitoring are not completely new. John A. Rogers, PhD, of Northwestern University, Chicago, first put forth the idea of monitoring through temporary tattoos 12 years ago. Some concepts, such as UV monitoring tattoos, had already been adopted by scientists and put on the market. But the existing models weren’t suitable for monitoring blood pressure, according to Deji Akinwande, PhD, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Texas at Austin and another coauthor of the study.

“[UV monitoring tattoos] are very thick,” he says. “They create too much movement when used to measure blood pressure because they slide around.”

So, the Texas-based research team worked to develop an option that was slimmer and more stable.

“The key ingredient within e-tattoos is graphene,” says Dr. Akinwande.

Graphene is carbon that’s similar to what’s inside your graphite pencil. The material is conductive, meaning it can conduct small electrical currents through the skin. For blood pressure monitoring, graphene promotes bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), which is like the technology used in smart scales that measure body fat.

With e-tattoos, the thin layers of graphene stick to the skin and do not slide around, getting rid of “artifacts,” or bad data. The graphene e-tattoos can be worn on the skin for about a week – or roughly as long as the temporary tattoos kids love.