User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Real-world study affirms benefits of dupilumab in pediatric patients with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Dupilumab is efficacious and safe in pediatric patients with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis (AD), including those aged 2 to <6 years.

Major finding: At week 16, the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score decreased significantly from 29.0 to 5.1 (P < .0001) and 73.3% and 53.3% of patients achieved ≥75% improvement in EASI and Scoring Atopic Dermatitis scores, respectively. The change in clinical scores was similar among the 2 to <6-year, 6 to <12-year, and 12 to <18-year subgroups. No serious treatment-emergent adverse events were observed.

Study details: This single-center real-world retrospective study included 39 patients aged 2 to <18 years with uncontrolled AD who received dupilumab therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang Y et al. Dupilumab improves clinical scores in pediatric patients aged 2 to <18 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: A single-center, real-world study. Dermatol Ther. 2023;5626410 (Apr 17). Doi: 10.1155/2023/5626410

Key clinical point: Dupilumab is efficacious and safe in pediatric patients with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis (AD), including those aged 2 to <6 years.

Major finding: At week 16, the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score decreased significantly from 29.0 to 5.1 (P < .0001) and 73.3% and 53.3% of patients achieved ≥75% improvement in EASI and Scoring Atopic Dermatitis scores, respectively. The change in clinical scores was similar among the 2 to <6-year, 6 to <12-year, and 12 to <18-year subgroups. No serious treatment-emergent adverse events were observed.

Study details: This single-center real-world retrospective study included 39 patients aged 2 to <18 years with uncontrolled AD who received dupilumab therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang Y et al. Dupilumab improves clinical scores in pediatric patients aged 2 to <18 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: A single-center, real-world study. Dermatol Ther. 2023;5626410 (Apr 17). Doi: 10.1155/2023/5626410

Key clinical point: Dupilumab is efficacious and safe in pediatric patients with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis (AD), including those aged 2 to <6 years.

Major finding: At week 16, the mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score decreased significantly from 29.0 to 5.1 (P < .0001) and 73.3% and 53.3% of patients achieved ≥75% improvement in EASI and Scoring Atopic Dermatitis scores, respectively. The change in clinical scores was similar among the 2 to <6-year, 6 to <12-year, and 12 to <18-year subgroups. No serious treatment-emergent adverse events were observed.

Study details: This single-center real-world retrospective study included 39 patients aged 2 to <18 years with uncontrolled AD who received dupilumab therapy.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Wang Y et al. Dupilumab improves clinical scores in pediatric patients aged 2 to <18 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: A single-center, real-world study. Dermatol Ther. 2023;5626410 (Apr 17). Doi: 10.1155/2023/5626410

Crisaborole induces normalization of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis proteome

Key Clinical Point: Crisaborole induces proteomic changes and modulates the lesional skin phenotype toward normal skin in mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At days 8 and 15, a markedly greater number of biomarkers were down-regulated with crisaborole vs vehicle (123 vs 9 and 162 vs 22, respectively), with a significantly higher rate of improvement in the overall lesional (45.9% vs 12.6% and 57.0% vs 28.3%, respectively; both P < .001) and nonlesional (53.0% vs 15.5% and 62.6% vs 36.8%, respectively; both P < .001) proteomes relative to a normal skin proteome.

Study details: This phase 2a study conducted a proteomic analysis in 20 control individuals and 40 adult patients with mild-to-moderate AD after double-blind, 1:1 random assignment of two target lesions in each patient with AD to crisaborole (2% ointment) or vehicle twice daily for 14 days.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer, New York. Some authors reported ties with various organizations, including Pfizer. One author declared being an employee of and holding shares in Pfizer.

Source: Kim M et al. Crisaborole reverses dysregulation of the mild to moderate atopic dermatitis proteome towards nonlesional and normal skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 10). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.02.064

Key Clinical Point: Crisaborole induces proteomic changes and modulates the lesional skin phenotype toward normal skin in mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At days 8 and 15, a markedly greater number of biomarkers were down-regulated with crisaborole vs vehicle (123 vs 9 and 162 vs 22, respectively), with a significantly higher rate of improvement in the overall lesional (45.9% vs 12.6% and 57.0% vs 28.3%, respectively; both P < .001) and nonlesional (53.0% vs 15.5% and 62.6% vs 36.8%, respectively; both P < .001) proteomes relative to a normal skin proteome.

Study details: This phase 2a study conducted a proteomic analysis in 20 control individuals and 40 adult patients with mild-to-moderate AD after double-blind, 1:1 random assignment of two target lesions in each patient with AD to crisaborole (2% ointment) or vehicle twice daily for 14 days.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer, New York. Some authors reported ties with various organizations, including Pfizer. One author declared being an employee of and holding shares in Pfizer.

Source: Kim M et al. Crisaborole reverses dysregulation of the mild to moderate atopic dermatitis proteome towards nonlesional and normal skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 10). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.02.064

Key Clinical Point: Crisaborole induces proteomic changes and modulates the lesional skin phenotype toward normal skin in mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At days 8 and 15, a markedly greater number of biomarkers were down-regulated with crisaborole vs vehicle (123 vs 9 and 162 vs 22, respectively), with a significantly higher rate of improvement in the overall lesional (45.9% vs 12.6% and 57.0% vs 28.3%, respectively; both P < .001) and nonlesional (53.0% vs 15.5% and 62.6% vs 36.8%, respectively; both P < .001) proteomes relative to a normal skin proteome.

Study details: This phase 2a study conducted a proteomic analysis in 20 control individuals and 40 adult patients with mild-to-moderate AD after double-blind, 1:1 random assignment of two target lesions in each patient with AD to crisaborole (2% ointment) or vehicle twice daily for 14 days.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Pfizer, New York. Some authors reported ties with various organizations, including Pfizer. One author declared being an employee of and holding shares in Pfizer.

Source: Kim M et al. Crisaborole reverses dysregulation of the mild to moderate atopic dermatitis proteome towards nonlesional and normal skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 10). Doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.02.064

Tralokinumab effective against moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis in adolescents

Key clinical point: Tralokinumab-mediated specific targeting of interleukin-13 is effective and safe in treating adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 150 mg or 300 mg tralokinumab vs placebo achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (21.4% and 17.5% vs 4.3%; P < .001 and P = .002, respectively) and ≥75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (28.6% and 27.8% vs 6.4%, respectively; both P < .001) without rescue medication. Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial including 289 adolescents (12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 150 mg tralokinumab (n = 98), 300 mg tralokinumab (n = 97), or placebo (n = 94).

Disclosures: This study was funded by LEO Pharma. Some authors reported ties with various organizations including LEO Pharma. Five authors declared being employees of or holding shares in LEO Pharma.

Source: Paller AS et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: The phase 3 ECZTRA 6 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0627

Key clinical point: Tralokinumab-mediated specific targeting of interleukin-13 is effective and safe in treating adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 150 mg or 300 mg tralokinumab vs placebo achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (21.4% and 17.5% vs 4.3%; P < .001 and P = .002, respectively) and ≥75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (28.6% and 27.8% vs 6.4%, respectively; both P < .001) without rescue medication. Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial including 289 adolescents (12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 150 mg tralokinumab (n = 98), 300 mg tralokinumab (n = 97), or placebo (n = 94).

Disclosures: This study was funded by LEO Pharma. Some authors reported ties with various organizations including LEO Pharma. Five authors declared being employees of or holding shares in LEO Pharma.

Source: Paller AS et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: The phase 3 ECZTRA 6 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0627

Key clinical point: Tralokinumab-mediated specific targeting of interleukin-13 is effective and safe in treating adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD).

Major finding: At week 16, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 150 mg or 300 mg tralokinumab vs placebo achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1 (21.4% and 17.5% vs 4.3%; P < .001 and P = .002, respectively) and ≥75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index score (28.6% and 27.8% vs 6.4%, respectively; both P < .001) without rescue medication. Most adverse events were mild or moderate in severity.

Study details: Findings are from the phase 3 ECZTRA 6 trial including 289 adolescents (12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 150 mg tralokinumab (n = 98), 300 mg tralokinumab (n = 97), or placebo (n = 94).

Disclosures: This study was funded by LEO Pharma. Some authors reported ties with various organizations including LEO Pharma. Five authors declared being employees of or holding shares in LEO Pharma.

Source: Paller AS et al. Efficacy and safety of tralokinumab in adolescents with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: The phase 3 ECZTRA 6 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 19). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0627

Upadacitinib shows a favorable benefit-risk profile in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib is as effective and safe in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) as in adults with AD.

Major finding: At week 16, in Measure Up 1 and 2 and AD Up, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 15/30 mg upadacitinib vs placebo achieved Eczema Area and Severity Index-75 (73%/78%, 69%/73%, and 63%/84% vs 12%, 13%, and 30%, respectively; all P < .001) and Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 (45%/64%, 45%/59%, and 38%/67% vs 7%, 5%, and 11%, respectively; all P < .001). The safety profile was consistent in adolescents and adults.

Study details: This interim analysis of 3 phase 3 trials included 552 adolescents (12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 15 mg upadacitinib, 30 mg upadacitinib, or placebo alone (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2) or with topical corticosteroids (AD Up).

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. Some authors reported ties with various organizations, including AbbVie. Nine authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Paller AS et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib treatment in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Analysis of the Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2, and AD Up randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 12). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0391

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib is as effective and safe in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) as in adults with AD.

Major finding: At week 16, in Measure Up 1 and 2 and AD Up, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 15/30 mg upadacitinib vs placebo achieved Eczema Area and Severity Index-75 (73%/78%, 69%/73%, and 63%/84% vs 12%, 13%, and 30%, respectively; all P < .001) and Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 (45%/64%, 45%/59%, and 38%/67% vs 7%, 5%, and 11%, respectively; all P < .001). The safety profile was consistent in adolescents and adults.

Study details: This interim analysis of 3 phase 3 trials included 552 adolescents (12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 15 mg upadacitinib, 30 mg upadacitinib, or placebo alone (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2) or with topical corticosteroids (AD Up).

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. Some authors reported ties with various organizations, including AbbVie. Nine authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Paller AS et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib treatment in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Analysis of the Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2, and AD Up randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 12). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0391

Key clinical point: Upadacitinib is as effective and safe in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) as in adults with AD.

Major finding: At week 16, in Measure Up 1 and 2 and AD Up, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving 15/30 mg upadacitinib vs placebo achieved Eczema Area and Severity Index-75 (73%/78%, 69%/73%, and 63%/84% vs 12%, 13%, and 30%, respectively; all P < .001) and Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0/1 (45%/64%, 45%/59%, and 38%/67% vs 7%, 5%, and 11%, respectively; all P < .001). The safety profile was consistent in adolescents and adults.

Study details: This interim analysis of 3 phase 3 trials included 552 adolescents (12-17 years) with moderate-to-severe AD who were randomly assigned to receive 15 mg upadacitinib, 30 mg upadacitinib, or placebo alone (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2) or with topical corticosteroids (AD Up).

Disclosures: This study was funded by AbbVie Inc. Some authors reported ties with various organizations, including AbbVie. Nine authors declared being employees of or holding stock or stock options in AbbVie.

Source: Paller AS et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib treatment in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: Analysis of the Measure Up 1, Measure Up 2, and AD Up randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2023 (Apr 12). Doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0391

The antimicrobial peptide that even Pharma can love

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

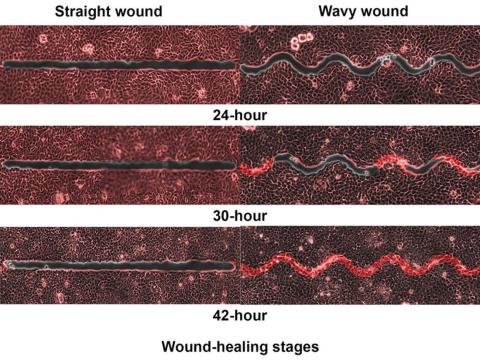

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Expunging ‘penicillin allergy’: Your questions answered

Last month, I described a 28-year-old patient with a history of injection drug use who presented with pain in his left forearm. His history showed that, within the past 2 years, he’d been seen for cutaneous infections multiple times as an outpatient and in the emergency department. His records indicated that he was diagnosed with a penicillin allergy as a child when he developed a rash after receiving amoxicillin. I believed the next course of action should be to test for a penicillin allergy with an oral amoxicillin challenge.

Thank you for your excellent questions regarding this case. Great to hear the enthusiasm for testing for penicillin allergy!

One question focused on the course of action in the case of a mild or moderate IgE-mediated reaction after a single dose test with amoxicillin. Treatment for these reactions should include an antihistamine. I would reserve intravenous antihistamines for more severe cases, which also require treatment with a course of corticosteroids. However, the risk for a moderate to severe reaction to amoxicillin on retesting is quite low.

Clinicians need to exercise caution in the use of systemic corticosteroids. These drugs can be lifesaving, but even short courses of corticosteroids are associated with potentially serious adverse events. In a review of adverse events associated with short-course systemic corticosteroids among children, the rate of vomiting was 5.4%; behavioral change, 4.7%; and sleep disturbance, 4.3%. One child died after contracting herpes zoster, more than one-third of children developed elevated blood pressure, and 81.1% had evidence of suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Among adults, short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with acute increases in the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hypertension. Cumulative exposure to short courses of corticosteroids over time results in higher risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Another question prompted by this young man’s case focused on the durability of IgE reactions against penicillin. The IgE response to penicillin does indeed wane over time; 80% of patients with a previous true penicillin allergy can tolerate the antibiotic after 10 years. Thus, about 95% of patients with a remote history of penicillin allergy are tolerant of penicillin, and testing can be performed using the algorithm described.

Clinicians should avoid applying current guidelines for the evaluation of patients with penicillin allergy to other common drug allergies. The overall prevalence of sulfonamide allergy is 3%-8%, and the vast majority of these reactions follow treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sulfa allergy is even more common among persons living with HIV infection. The natural history of sulfa allergy is not as well established as penicillin allergy. Allergy testing is encouraged in these cases. Graded oral challenge testing is best reserved for patients who are unlikely to have a true sulfa allergy based on their history.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last month, I described a 28-year-old patient with a history of injection drug use who presented with pain in his left forearm. His history showed that, within the past 2 years, he’d been seen for cutaneous infections multiple times as an outpatient and in the emergency department. His records indicated that he was diagnosed with a penicillin allergy as a child when he developed a rash after receiving amoxicillin. I believed the next course of action should be to test for a penicillin allergy with an oral amoxicillin challenge.

Thank you for your excellent questions regarding this case. Great to hear the enthusiasm for testing for penicillin allergy!

One question focused on the course of action in the case of a mild or moderate IgE-mediated reaction after a single dose test with amoxicillin. Treatment for these reactions should include an antihistamine. I would reserve intravenous antihistamines for more severe cases, which also require treatment with a course of corticosteroids. However, the risk for a moderate to severe reaction to amoxicillin on retesting is quite low.

Clinicians need to exercise caution in the use of systemic corticosteroids. These drugs can be lifesaving, but even short courses of corticosteroids are associated with potentially serious adverse events. In a review of adverse events associated with short-course systemic corticosteroids among children, the rate of vomiting was 5.4%; behavioral change, 4.7%; and sleep disturbance, 4.3%. One child died after contracting herpes zoster, more than one-third of children developed elevated blood pressure, and 81.1% had evidence of suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Among adults, short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with acute increases in the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hypertension. Cumulative exposure to short courses of corticosteroids over time results in higher risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Another question prompted by this young man’s case focused on the durability of IgE reactions against penicillin. The IgE response to penicillin does indeed wane over time; 80% of patients with a previous true penicillin allergy can tolerate the antibiotic after 10 years. Thus, about 95% of patients with a remote history of penicillin allergy are tolerant of penicillin, and testing can be performed using the algorithm described.

Clinicians should avoid applying current guidelines for the evaluation of patients with penicillin allergy to other common drug allergies. The overall prevalence of sulfonamide allergy is 3%-8%, and the vast majority of these reactions follow treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sulfa allergy is even more common among persons living with HIV infection. The natural history of sulfa allergy is not as well established as penicillin allergy. Allergy testing is encouraged in these cases. Graded oral challenge testing is best reserved for patients who are unlikely to have a true sulfa allergy based on their history.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last month, I described a 28-year-old patient with a history of injection drug use who presented with pain in his left forearm. His history showed that, within the past 2 years, he’d been seen for cutaneous infections multiple times as an outpatient and in the emergency department. His records indicated that he was diagnosed with a penicillin allergy as a child when he developed a rash after receiving amoxicillin. I believed the next course of action should be to test for a penicillin allergy with an oral amoxicillin challenge.

Thank you for your excellent questions regarding this case. Great to hear the enthusiasm for testing for penicillin allergy!

One question focused on the course of action in the case of a mild or moderate IgE-mediated reaction after a single dose test with amoxicillin. Treatment for these reactions should include an antihistamine. I would reserve intravenous antihistamines for more severe cases, which also require treatment with a course of corticosteroids. However, the risk for a moderate to severe reaction to amoxicillin on retesting is quite low.

Clinicians need to exercise caution in the use of systemic corticosteroids. These drugs can be lifesaving, but even short courses of corticosteroids are associated with potentially serious adverse events. In a review of adverse events associated with short-course systemic corticosteroids among children, the rate of vomiting was 5.4%; behavioral change, 4.7%; and sleep disturbance, 4.3%. One child died after contracting herpes zoster, more than one-third of children developed elevated blood pressure, and 81.1% had evidence of suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Among adults, short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with acute increases in the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hypertension. Cumulative exposure to short courses of corticosteroids over time results in higher risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Another question prompted by this young man’s case focused on the durability of IgE reactions against penicillin. The IgE response to penicillin does indeed wane over time; 80% of patients with a previous true penicillin allergy can tolerate the antibiotic after 10 years. Thus, about 95% of patients with a remote history of penicillin allergy are tolerant of penicillin, and testing can be performed using the algorithm described.

Clinicians should avoid applying current guidelines for the evaluation of patients with penicillin allergy to other common drug allergies. The overall prevalence of sulfonamide allergy is 3%-8%, and the vast majority of these reactions follow treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sulfa allergy is even more common among persons living with HIV infection. The natural history of sulfa allergy is not as well established as penicillin allergy. Allergy testing is encouraged in these cases. Graded oral challenge testing is best reserved for patients who are unlikely to have a true sulfa allergy based on their history.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

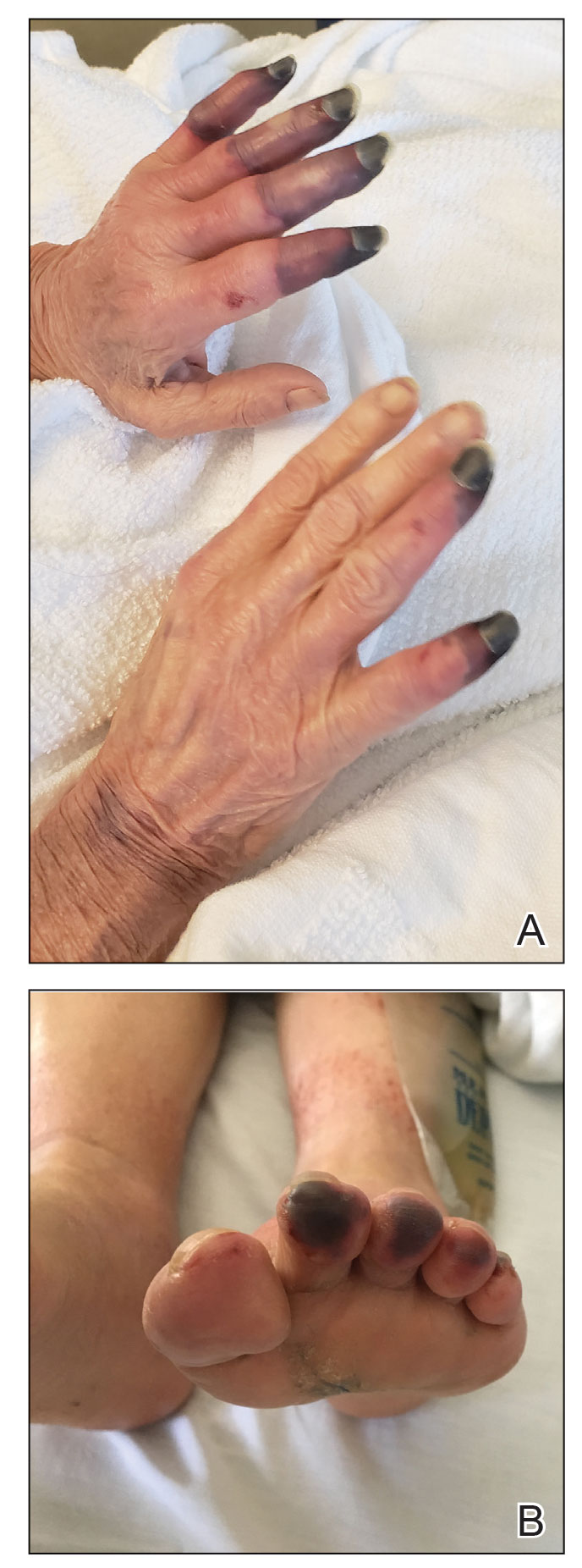

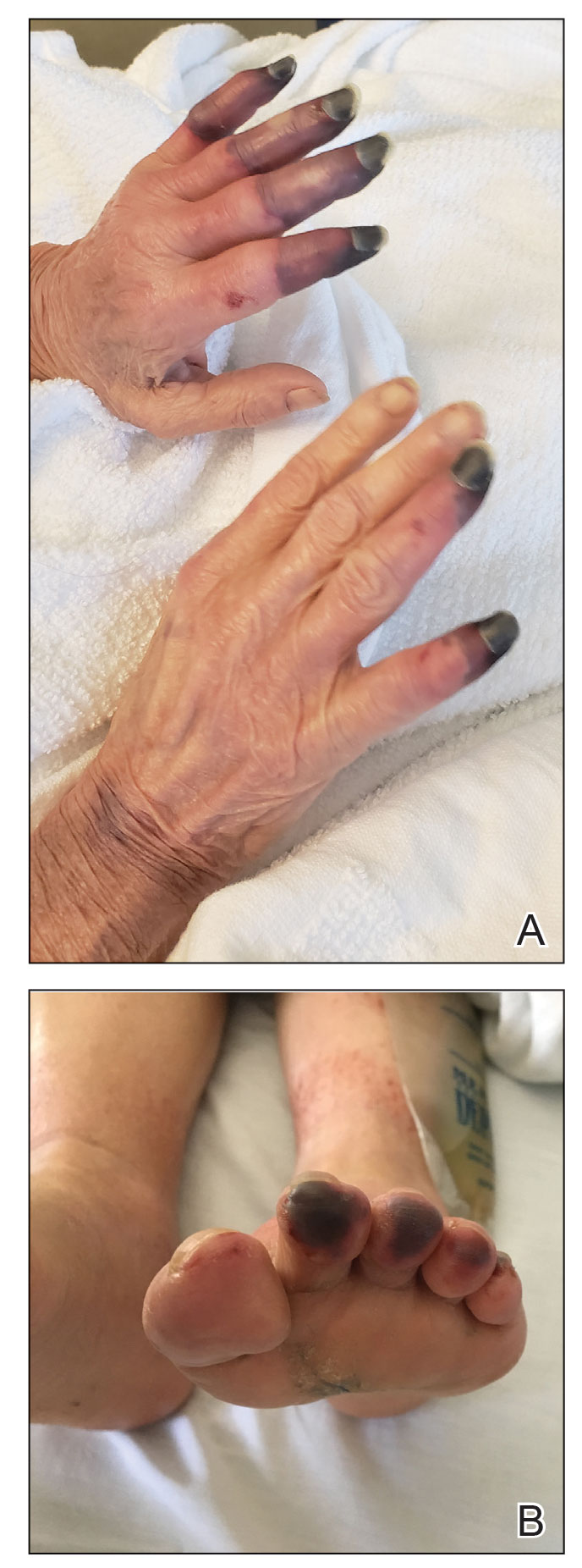

Acral Necrosis After PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy

To the Editor:

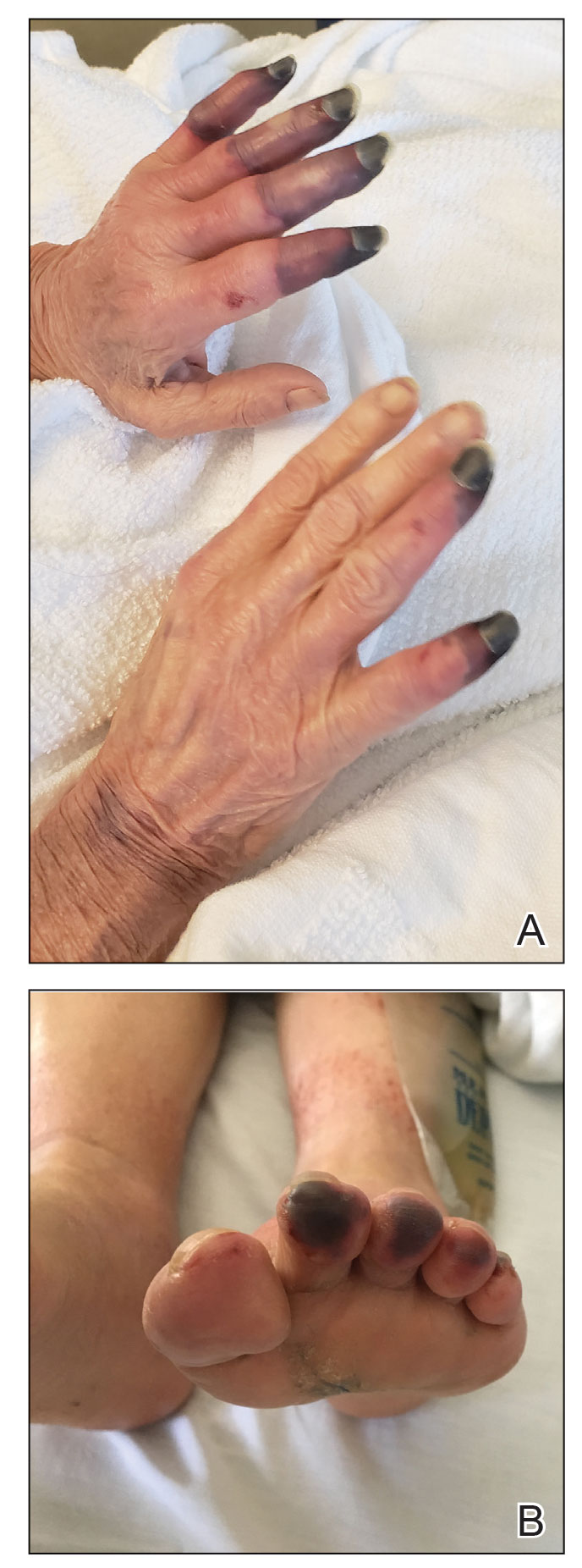

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

To the Editor:

A 67-year-old woman presented to the hospital with painful hands and feet. Two weeks prior, the patient experienced a few days of intermittent purple discoloration of the fingers, followed by black discoloration of the fingers, toes, and nose with notable pain. She reported no illness preceding the presenting symptoms, and there was no progression of symptoms in the days preceding presentation.

The patient had a history of smoking. She had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as well as recurrent non–small cell lung cancer that was treated most recently with a 1-year course of the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab (last treatment was 4 months prior to the current presentation).

Physical examination revealed necrosis of the tips of the second, third, and fourth fingers of the left hand, as well as the tips of the third and fourth fingers of the right hand, progressing to purpura proximally on all involved fingers (Figure, A); scattered purpura and necrotic papules on the toe pads (Figure, B); and a 2- to 3-cm black plaque on the nasal tip. The patient was afebrile.

An embolic and vascular workup was performed. Transthoracic echocardiography was negative for thrombi, ankle brachial indices were within reference range, and computed tomography angiography revealed a few nonocclusive coronary plaques. Conventional angiography was not performed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mildly elevated level of cryofibrinogens (cryocrit, 2.5%); cold agglutinins (1:32); mild monoclonal κ IgG gammopathy (0.1 g/dL); and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, 76 mg/L [reference range, 0–10 mg/L]; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 38 mm/h [reference range, 0–20 mm/h]; fibrinogen, 571 mg/dL [reference range, 150–450 mg/dL]; and ferritin, 394 ng/mL [reference range, 10–180 ng/mL]). Additional laboratory studies were negative or within reference range, including tests of anti-RNA polymerase antibody, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, anticardiolipin antibody, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (myeloperoxidase and proteinase-3), cryoglobulins, and complement; human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B and C virus serologic studies; prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and lupus anticoagulant; and a heparin-induced thrombocytopenia panel.

A skin biopsy adjacent to an area of necrosis on the finger showed thickened walls of dermal vessels, sparse leukocytoclastic debris, and evidence of recanalizing medium-sized vessels. Direct immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Based on the clinical history and histologic findings showing an absence of vasculitis, a diagnosis of acral necrosis associated with the PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitor durvalumab—a delayed immune-related event (DIRE)—was favored. The calcium channel blocker amlodipine was started at a dosage of 2.5 mg/d orally. Necrosis of the toes resolved over the course of 1 week; however, necrosis of the fingers remained unchanged. After 1 week of hospitalization, the patient was discharged at her request.

Acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy has been reported as a rare and recalcitrant immune-related adverse event (AE).1-4 However, our patient’s symptoms occurred months after treatment was discontinued, which is consistent with a DIRE.5 The course of acral necrosis begins with acrocyanosis (a Raynaud disease–like phenomenon) of the fingers that progresses to necrosis. A history of Raynaud disease or other autoimmune disorder generally is absent.1 Our patient’s history indicated actively smoking at the time of presentation, similar to a case described by Khaddour et al.1 Similarly, in a case presented by Comont et al,3 the patient also had a history of smoking. In a recent study of acute vascular events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, 16 of 31 patients had a history of smoking.6

No definitive diagnostic laboratory or pathologic findings are associated with acral necrosis following immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Histopathologic analysis does not demonstrate vasculitis or other overt vascular pathology.2,3

The optimal treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor–associated digital necrosis is unclear. Corticosteroids and discontinuation of the immune checkpoint inhibitor generally are employed,1-4 though treatment response has been variable. Other therapies such as calcium channel blockers (as in our case), sympathectomy,1 epoprostenol, botulinum injection, rituximab,2 and alprostadil4 have been attempted without clear effect.

We considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in our patient, which was ruled out because the syndrome typically occurs in the setting of a worsening underlying malignancy7; our patient’s cancer was stable to improved. Thromboangiitis obliterans was ruled out by the absence of a characteristic thrombus on biopsy, the patient’s older age, and involvement of the nose.

We report an unusual case of acral necrosis occurring as a DIRE in response to administration of an immune checkpoint inhibitor. Further description is needed to clarify the diagnostic criteria for and treatment of this rare autoimmune phenomenon.

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

- Khaddour K, Singh V, Shayuk M. Acral vascular necrosis associated with immune-check point inhibitors: case report with literature review. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:449. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5661-x

- Padda A, Schiopu E, Sovich J, et al. Ipilimumab induced digital vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:12. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0321-2

- Comont T, Sibaud V, Mourey L, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related acral vasculitis. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:120. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0443-6

- Gambichler T, Strutzmann S, Tannapfel A, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome in a patient with metastatic melanoma under immune checkpoint blockade. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:327. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3313-6

- Couey MA, Bell RB, Patel AA, et al. Delayed immune-related events (DIRE) after discontinuation of immunotherapy: diagnostic hazard of autoimmunity at a distance. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:165. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0645-6

- Bar J, Markel G, Gottfried T, et al. Acute vascular events as a possibly related adverse event of immunotherapy: a single-institute retrospective study. Eur J Cancer. 2019;120:122-131. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2019.06.021

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, et al. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:47-52. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.120474

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware of acral necrosis as a rare adverse event of treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

- Delayed immune-related events are sequelae of immune checkpoint inhibitors that can occur months after treatment is discontinued.

Eruptive Keratoacanthomas After Nivolumab Treatment of Stage III Melanoma

To the Editor:

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors have been widely used in the treatment of various cancers. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-ligand 2 located on cancer cells will bind to PD-1 receptors on T cells and suppress them, which will prevent cancer cell destruction. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors block the binding of PD-L1 to cancer cells, which then prevents T-cell immunosuppression.1 However, cutaneous adverse effects have been associated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatitis associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy occurs more frequently in patients with cutaneous tumors such as melanoma compared to those with head and neck cancers.2 Curry et al1 reported that treatment with an immune checkpoint blockade can lead to immune-related adverse effects, most commonly affecting the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and skin. The same report cited dermatologic toxicity as an adverse effect in approximately 39% of patients treated with anti–PD-1 and approximately 17% of anti–PD-L1.1 The 4 main categories of dermatologic toxicities to immunotherapies in general include inflammatory disorders, immunobullous disorders, alterations of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes. The most common adverse effects from the use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab were skin rashes, not otherwise specified (14%–20%), pruritus (13%–18%), and vitiligo (~8%).1 Of the cutaneous dermatitic reactions to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors that were biopsied, the 2 most common were lichenoid dermatitis and spongiotic dermatitis.2 Seldomly, there have been reports of keratoacanthomas (KAs) in association with anti–PD-1 therapy.3

A KA is a common skin tumor that appears most frequently as a solitary lesion and is thought to arise from the hair follicle.4 It resembles squamous cell carcinoma and commonly regresses within months without intervention. Exposure to UV light is a known risk factor for the development of KAs.

Eruptive KAs have been found in association with 10 cases of various cancers treated with the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab.3 Multiple lesions on photodistributed areas of the body were reported in all 10 cases. Various treatments were used in these 10 cases—doxycycline and niacinamide, electrodesiccation and curettage, clobetasol ointment and/or intralesional triamcinolone, cryotherapy, imiquimod, or no treatment—as well as the cessation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, with 4 cases continuing therapy and 6 cases discontinuing therapy. Nine cases regressed by 6 months; electrodesiccation and curettage of the lesions was used in the tenth case.3 We report a case of eruptive KA after 1 cycle of nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma.

A 79-year-old woman with stage III melanoma presented to her dermatologist after developing generalized pruritic lichenoid eruptions involving the torso, arms, and legs, as well as erosions on the lips, buccal mucosa, and palate 1 month after starting nivolumab therapy. The patient initially presented to dermatology with an irregularly shaped lesion on the left upper back 3 months prior. Biopsy results at that time revealed a diagnosis of malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna type. The lesion was 1.5-mm thick and classified as Clark level IV with a mitotic count of 6 per mm2. Molecular genetic studies showed expression of PD-L1 and no expression of c-KIT. The patient underwent wide local excision, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive. Positron emission tomography did not show any hypermetabolic lesions, and magnetic resonance imaging did not indicate brain metastasis. The patient underwent an axillary dissection, which did not show any residual melanoma. She was started on adjuvant immunotherapy with intravenous nivolumab 480 mg monthly and developed pruritic crusted lesions on the arms, legs, and torso 1 month later, which prompted follow-up to dermatology.

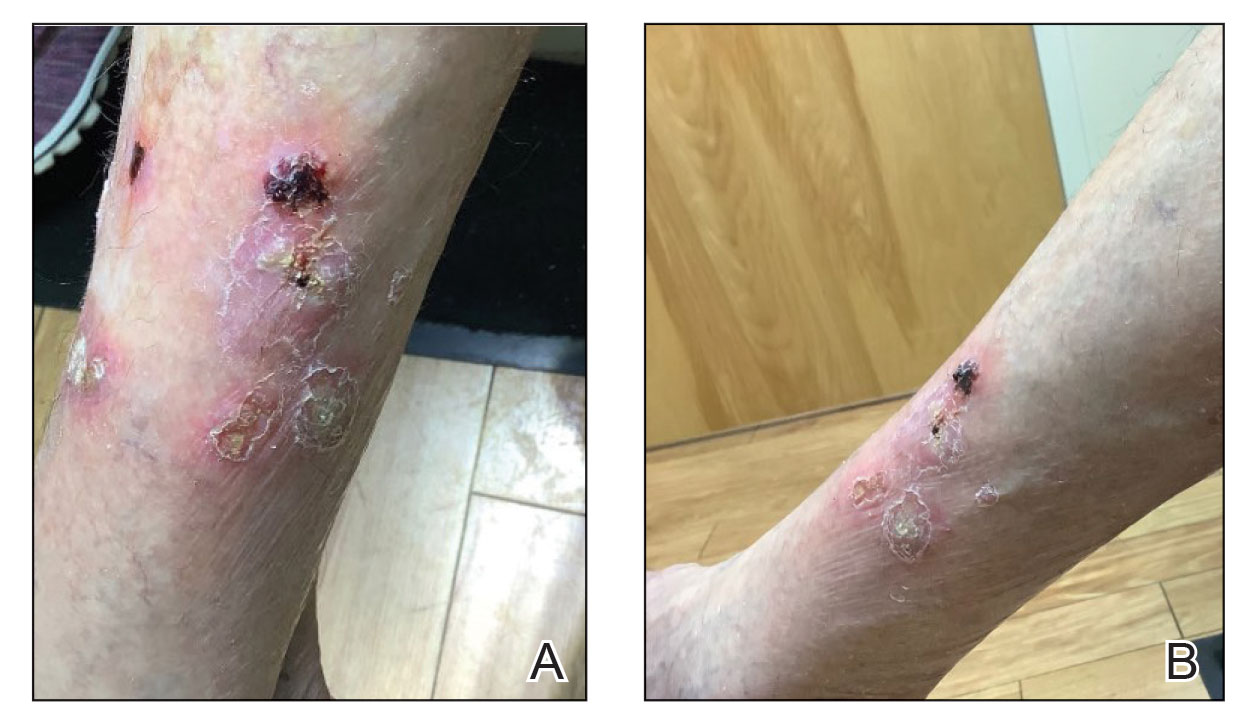

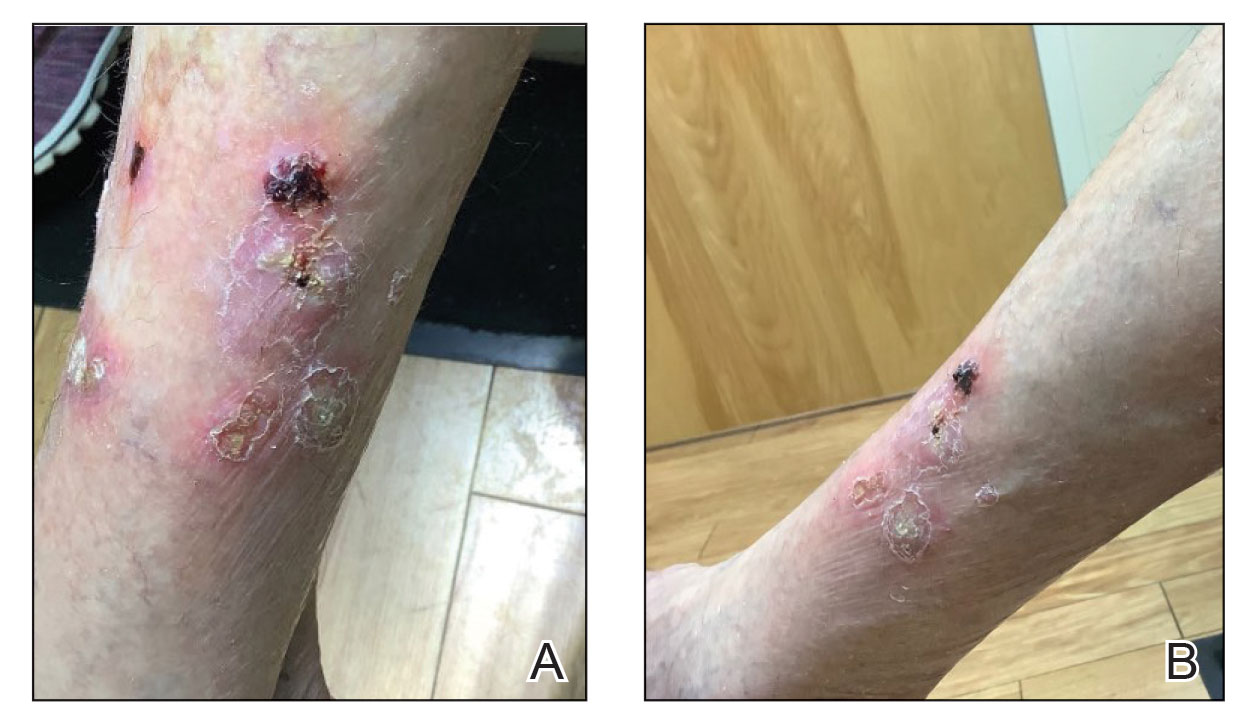

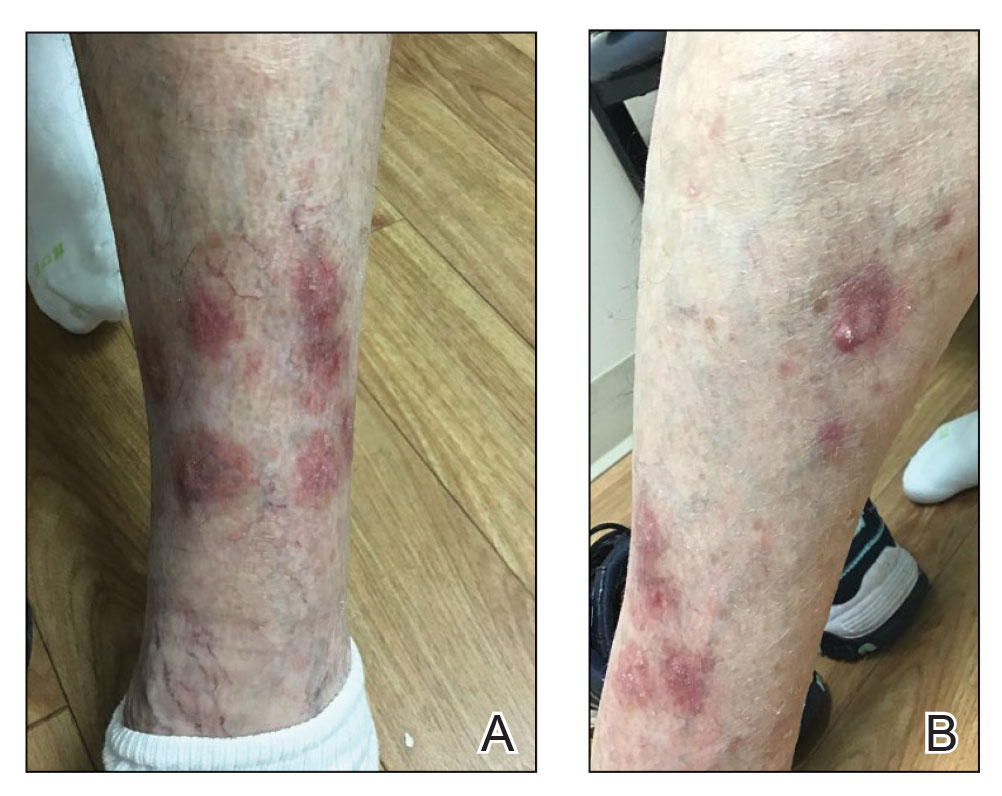

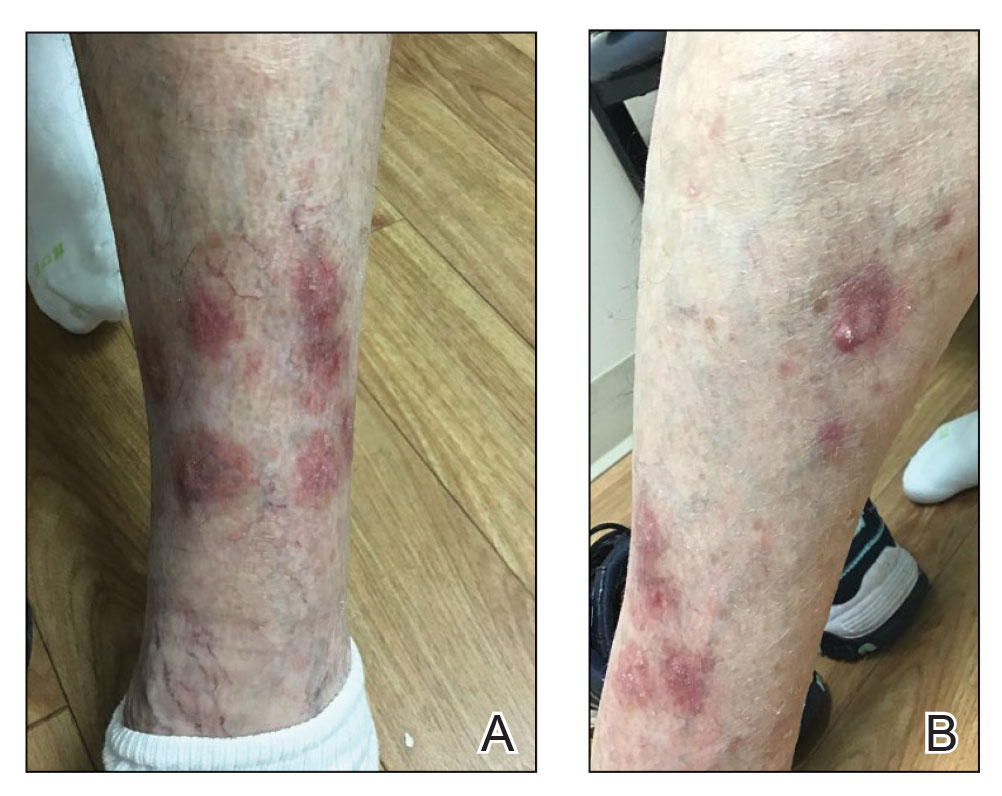

At the current presentation 4 months after the onset of lesions, physical examination revealed lichenoid patches with serous crusting that were concentrated on the torso but also affected the arms and legs. She developed erosions on the upper and lower lips, buccal mucosa, and hard and soft palates, as well as painful, erythematous, dome-shaped papules and nodules on the legs (Figure 1). Her oncologist previously had initiated treatment at the onset of the lesions with clobetasol cream and valacyclovir for the lesions, but the patient showed no improvement.

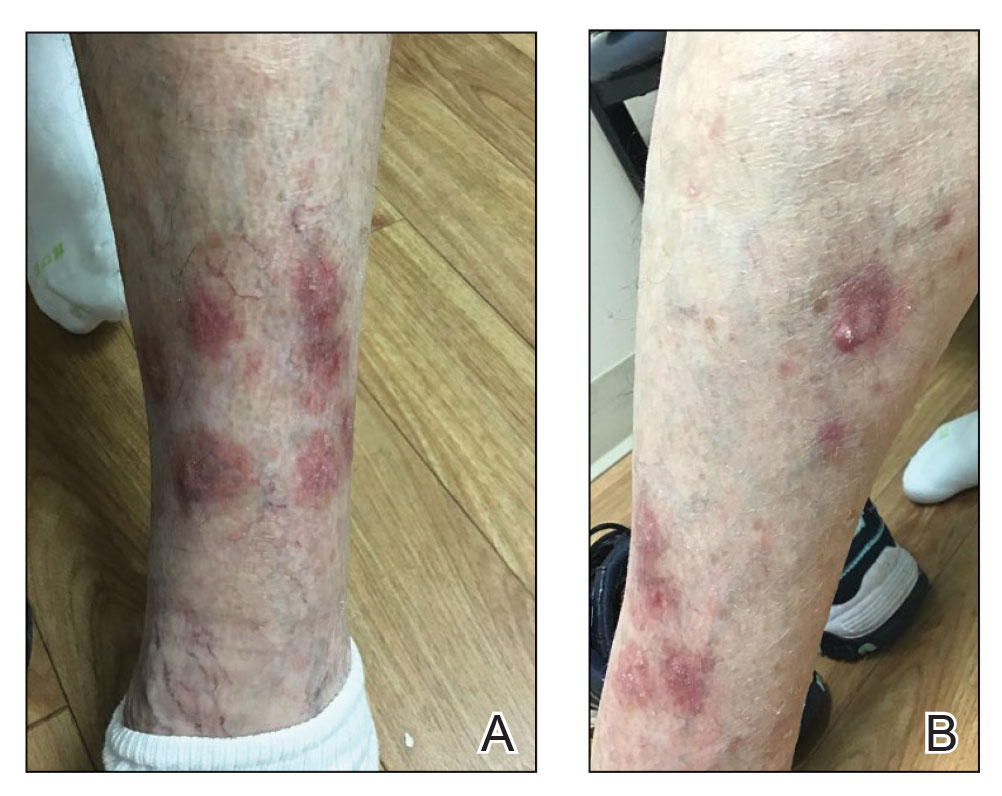

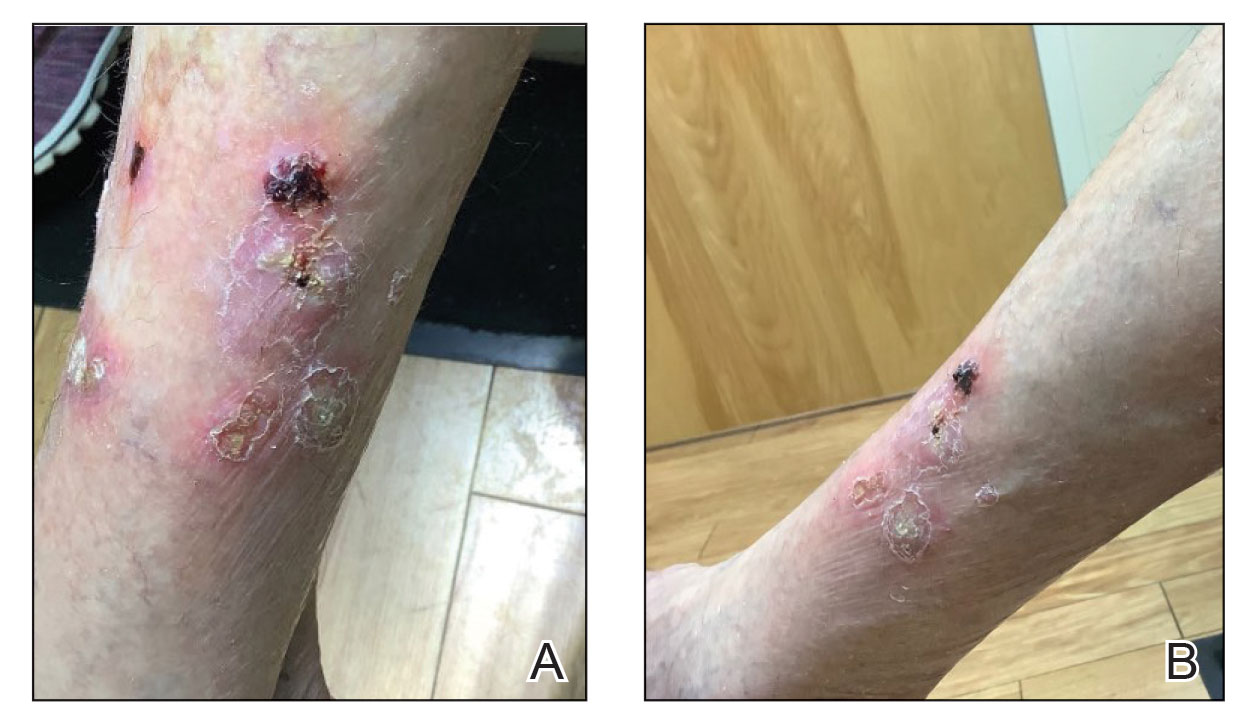

Four months after the onset of the lesions, the patient was re-referred to her dermatologist, and a biopsy was performed on the left lower leg that showed squamous cell carcinoma, KA type. Additionally, flat erythematous patches were seen on the legs that were consistent with a lichenoid drug eruption. Two weeks later, she was started on halobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% for treatment of the KAs. At 2-week follow-up, 5 months after the onset of the lesions, the patient showed no signs of improvement. An oral prednisone taper of 60 mg for 3 days, 40 mg for 3 days, and then 20 mg daily for a total of 4 weeks was started to treat the lichenoid dermatitis and eruptive KAs. At the next follow-up 6.5 months following the first eruptive KAs, she was no longer using topical or oral steroids, she did not have any new eruptive KAs, and old lesions showed regression (Figure 2). The patient still experienced postinflammatory erythema and hyperpigmentation at the location of the KAs but showed improvement of the lichenoid drug eruption.

We describe a case of eruptive KAs after use of a PD-1 inhibitor for treatment of melanoma. Our patient developed eruptive KAs after only 1 nivolumab treatment. Another report described onset of eruptive KAs after 1 month of nivolumab infusions.3 The KAs experienced by our patient took 6.5 months to regress, which is unusual compared to other case reports in which the KAs self-resolved within a few months, though one other case described lesions that persisted for 6 months.3

Our patient was treated with topical steroids and an oral steroid taper for the concomitant lichenoid drug eruption. It is unknown if the steroids affected the course of the KAs or if they spontaneously regressed on their own. Freites-Martinez et al5 described that regression of KAs may be related to an immune response, but corticosteroids are inherently immunosuppressive. They hypothesized that corticosteroids help to temper the heightened immune response of eruptive KAs.5

Our patient had oral ulcers, which may have been indicative of an oral lichenoid drug eruption, as well as skin lesions representative of a cutaneous lichenoid drug eruption. This is a favorable reaction, as lichenoid dermatitis is thought to represent successful PD-1 inhibition and therefore a better response to oncologic therapies.2 Comorbid lichenoid drug eruption lesions and eruptive KAs may be suggestive of increased T-cell activity,2,6,7 though some prior case studies have reported eruptive KAs in isolation.3

Discontinuation of immunotherapy due to development of eruptive KAs presents a challenge in the treatment of underlying malignancies such as melanoma. Immunotherapy was discontinued in 7 of 11 cases due to these cutaneous reactions.3 Similarly, our patient underwent only 1 cycle of immunotherapy before developing eruptive KAs and discontinuing PD-1 inhibitor therapy. If we are better able to treat eruptive KAs, then patients can remain on immunotherapy to treat underlying malignancies. Crow et al8 showed improvement in lesions when 3 patients with eruptive KAs were treated with hydroxychloroquine; the Goeckerman regimen consisting of steroids, UVB phototherapy, and crude coal tar; and Unna boots with zinc oxide and compression stockings. The above may be added to a list of possible treatments to consider for hastening the regression of eruptive KAs.

Our patient’s clinical course was similar to reports on the regressive nature of eruptive KAs within 6 months after initial eruption. Although it is likely that KAs will regress on their own, treatment modalities that speed up recovery are a future source for research.

- Curry JL, Tetzlaff MT, Nagarajan P, et al. Diverse types of dermatologic toxicities from immune checkpoint blockade therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:158-176.

- Min Lee CK, Li S, Tran DC, et al. Characterization of dermatitis after PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor therapy and association with multiple oncologic outcomes: a retrospective case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:1047-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.035

- Antonov NK, Nair KG, Halasz CL. Transient eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with nivolumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5:342-345. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.01.025

- Kwiek B, Schwartz RA. Keratoacanthoma (KA): an update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1220-1233.

- Freites-Martinez A, Kwong BY, Rieger KE, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas associated with pembrolizumab therapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:694-697. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0989

- Bednarek R, Marks K, Lin G. Eruptive keratoacanthomas secondary to nivolumab immunotherapy. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:E28-E29.

- Feldstein SI, Patel F, Kim E, et al. Eruptive keratoacanthomas arising in the setting of lichenoid toxicity after programmed cell death 1 inhibition with nivolumab. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:E58-E59.

- Crow LD, Perkins I, Twigg AR, et al. Treatment of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitor-induced dermatitis resolves concomitant eruptive keratoacanthomas. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:598-600. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0176

To the Editor:

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitors have been widely used in the treatment of various cancers. Programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-ligand 2 located on cancer cells will bind to PD-1 receptors on T cells and suppress them, which will prevent cancer cell destruction. Programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors block the binding of PD-L1 to cancer cells, which then prevents T-cell immunosuppression.1 However, cutaneous adverse effects have been associated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatitis associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy occurs more frequently in patients with cutaneous tumors such as melanoma compared to those with head and neck cancers.2 Curry et al1 reported that treatment with an immune checkpoint blockade can lead to immune-related adverse effects, most commonly affecting the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and skin. The same report cited dermatologic toxicity as an adverse effect in approximately 39% of patients treated with anti–PD-1 and approximately 17% of anti–PD-L1.1 The 4 main categories of dermatologic toxicities to immunotherapies in general include inflammatory disorders, immunobullous disorders, alterations of keratinocytes, and alteration of melanocytes. The most common adverse effects from the use of the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab were skin rashes, not otherwise specified (14%–20%), pruritus (13%–18%), and vitiligo (~8%).1 Of the cutaneous dermatitic reactions to PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors that were biopsied, the 2 most common were lichenoid dermatitis and spongiotic dermatitis.2 Seldomly, there have been reports of keratoacanthomas (KAs) in association with anti–PD-1 therapy.3

A KA is a common skin tumor that appears most frequently as a solitary lesion and is thought to arise from the hair follicle.4 It resembles squamous cell carcinoma and commonly regresses within months without intervention. Exposure to UV light is a known risk factor for the development of KAs.

Eruptive KAs have been found in association with 10 cases of various cancers treated with the PD-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and nivolumab.3 Multiple lesions on photodistributed areas of the body were reported in all 10 cases. Various treatments were used in these 10 cases—doxycycline and niacinamide, electrodesiccation and curettage, clobetasol ointment and/or intralesional triamcinolone, cryotherapy, imiquimod, or no treatment—as well as the cessation of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, with 4 cases continuing therapy and 6 cases discontinuing therapy. Nine cases regressed by 6 months; electrodesiccation and curettage of the lesions was used in the tenth case.3 We report a case of eruptive KA after 1 cycle of nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma.

A 79-year-old woman with stage III melanoma presented to her dermatologist after developing generalized pruritic lichenoid eruptions involving the torso, arms, and legs, as well as erosions on the lips, buccal mucosa, and palate 1 month after starting nivolumab therapy. The patient initially presented to dermatology with an irregularly shaped lesion on the left upper back 3 months prior. Biopsy results at that time revealed a diagnosis of malignant melanoma, lentigo maligna type. The lesion was 1.5-mm thick and classified as Clark level IV with a mitotic count of 6 per mm2. Molecular genetic studies showed expression of PD-L1 and no expression of c-KIT. The patient underwent wide local excision, and a sentinel lymph node biopsy was positive. Positron emission tomography did not show any hypermetabolic lesions, and magnetic resonance imaging did not indicate brain metastasis. The patient underwent an axillary dissection, which did not show any residual melanoma. She was started on adjuvant immunotherapy with intravenous nivolumab 480 mg monthly and developed pruritic crusted lesions on the arms, legs, and torso 1 month later, which prompted follow-up to dermatology.

At the current presentation 4 months after the onset of lesions, physical examination revealed lichenoid patches with serous crusting that were concentrated on the torso but also affected the arms and legs. She developed erosions on the upper and lower lips, buccal mucosa, and hard and soft palates, as well as painful, erythematous, dome-shaped papules and nodules on the legs (Figure 1). Her oncologist previously had initiated treatment at the onset of the lesions with clobetasol cream and valacyclovir for the lesions, but the patient showed no improvement.