User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Vitiligo

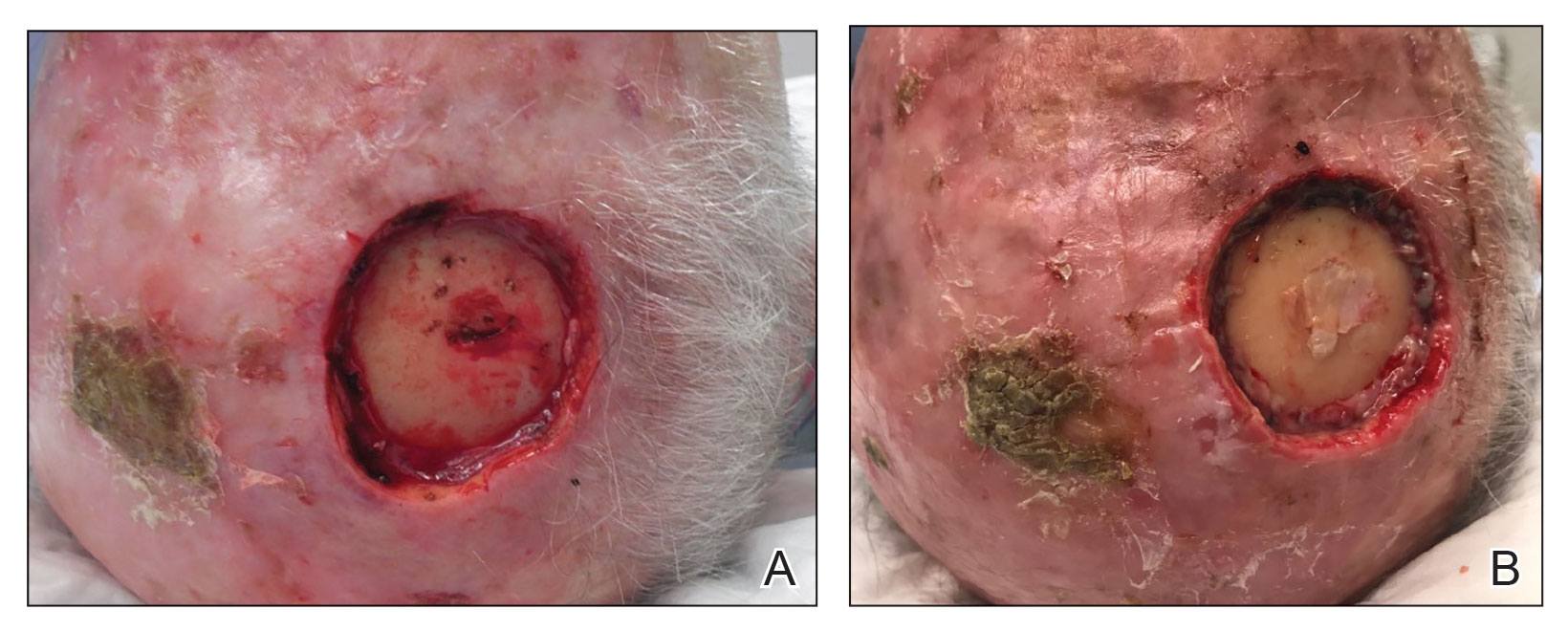

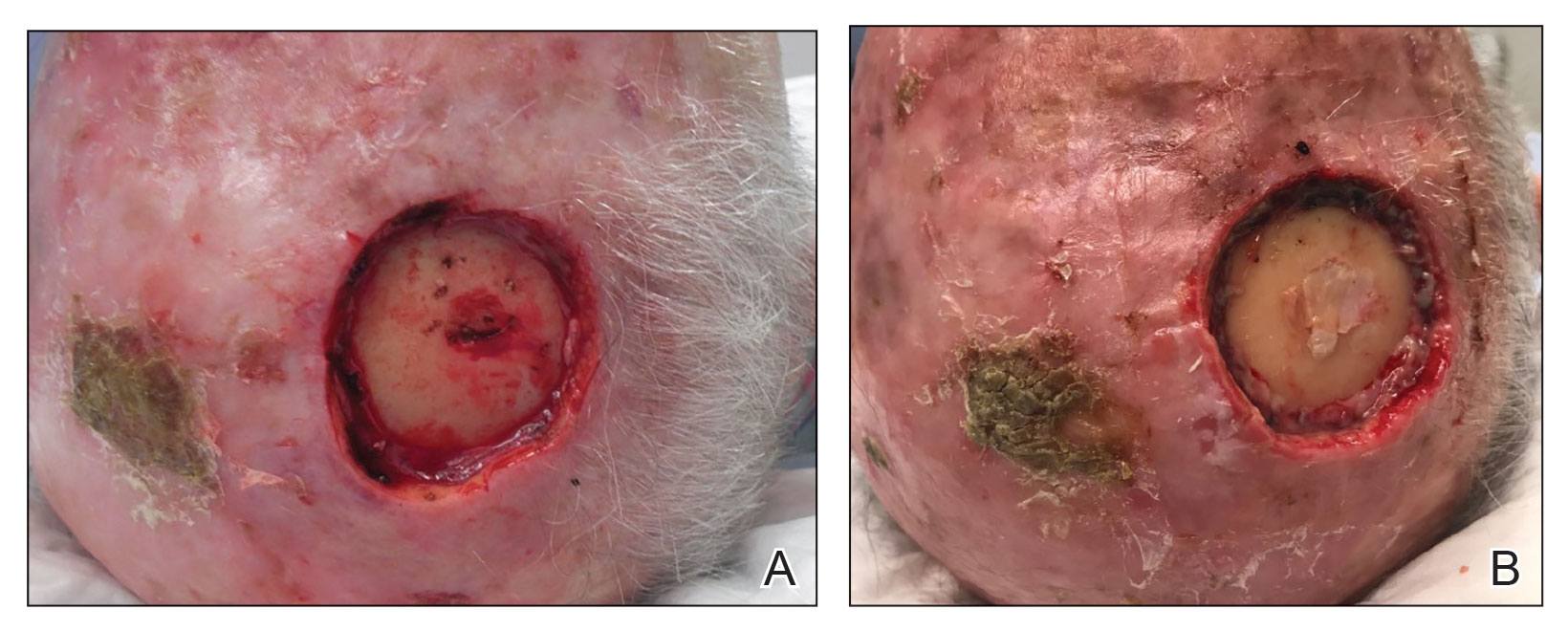

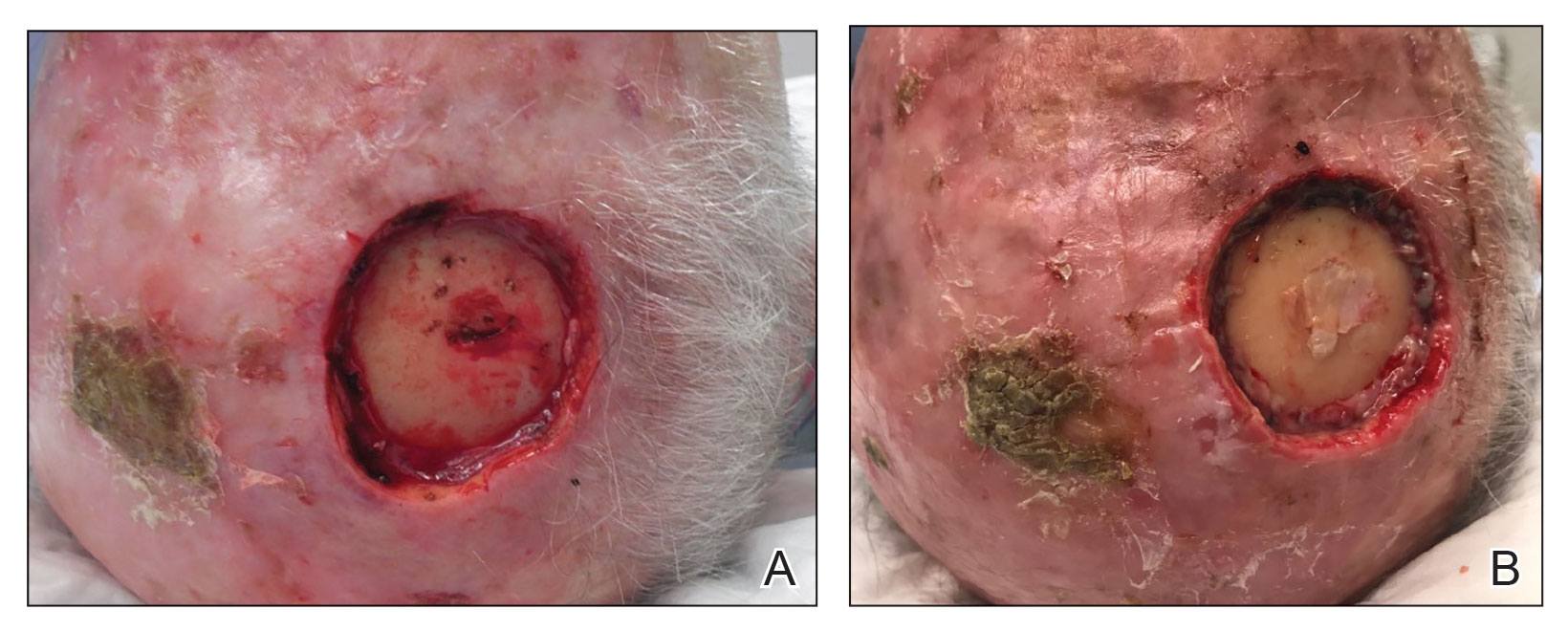

THE COMPARISON

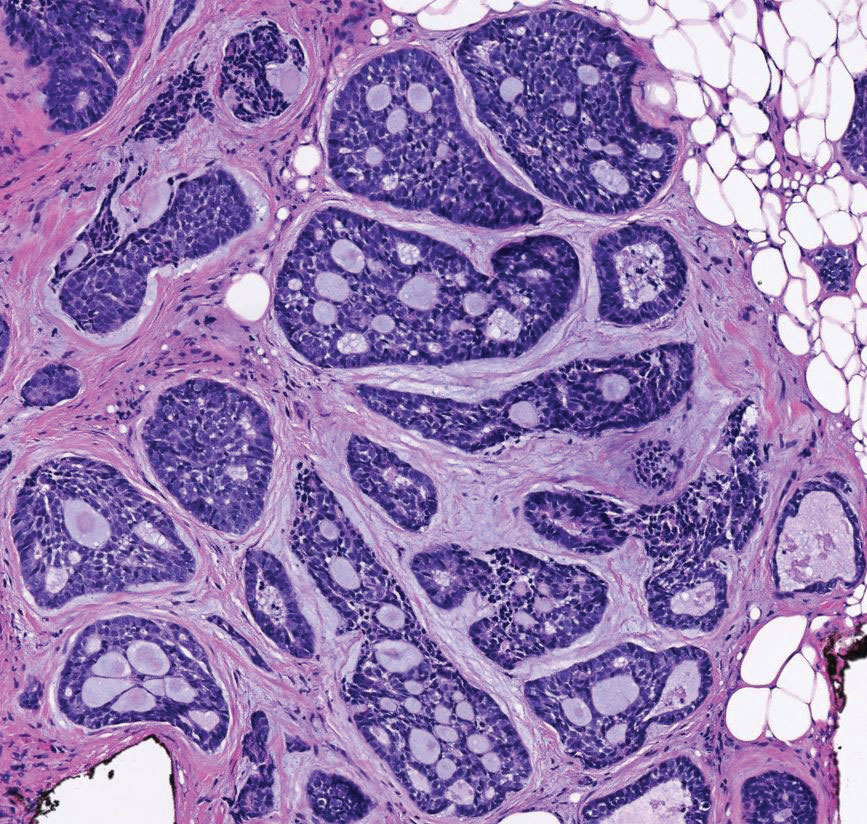

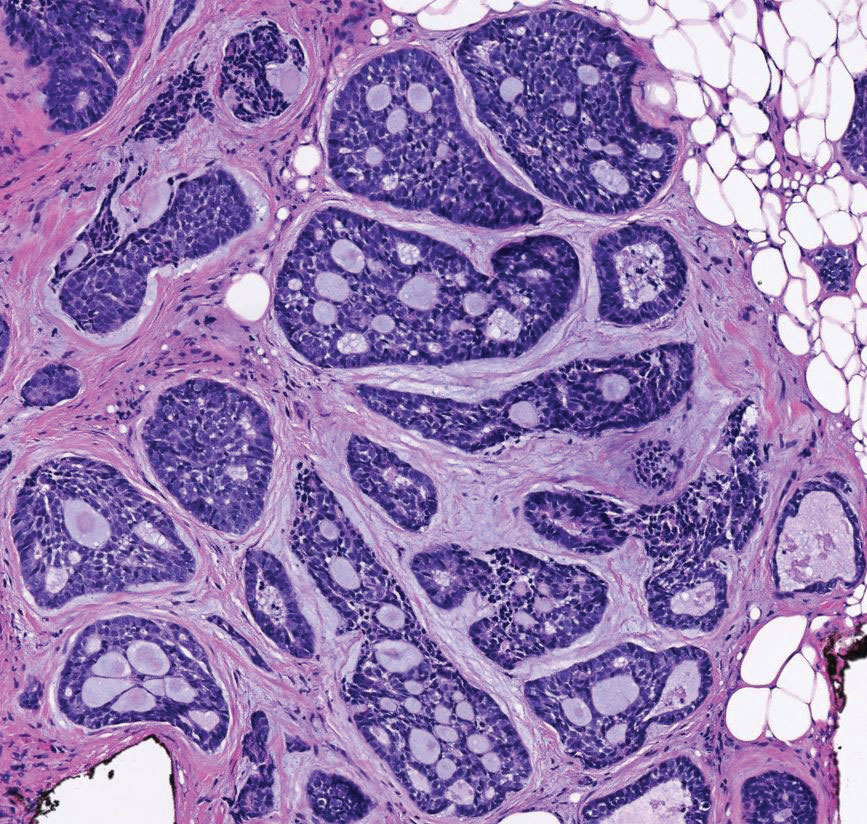

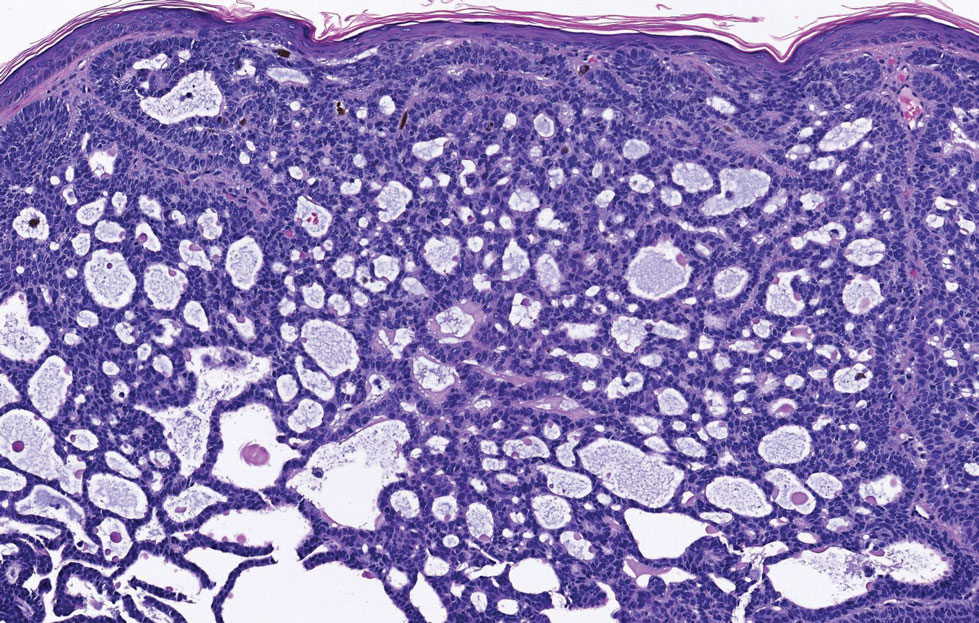

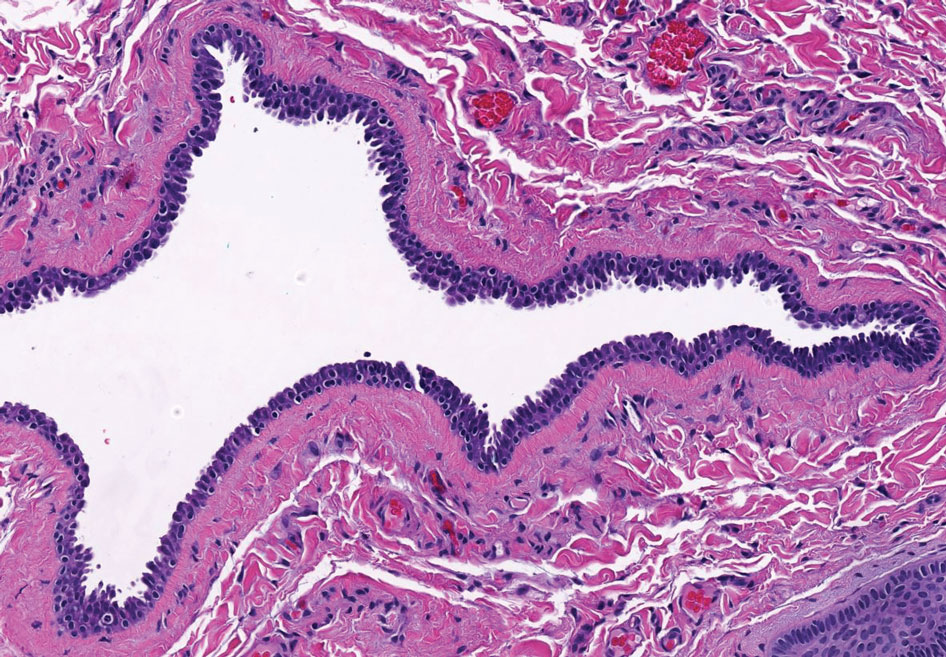

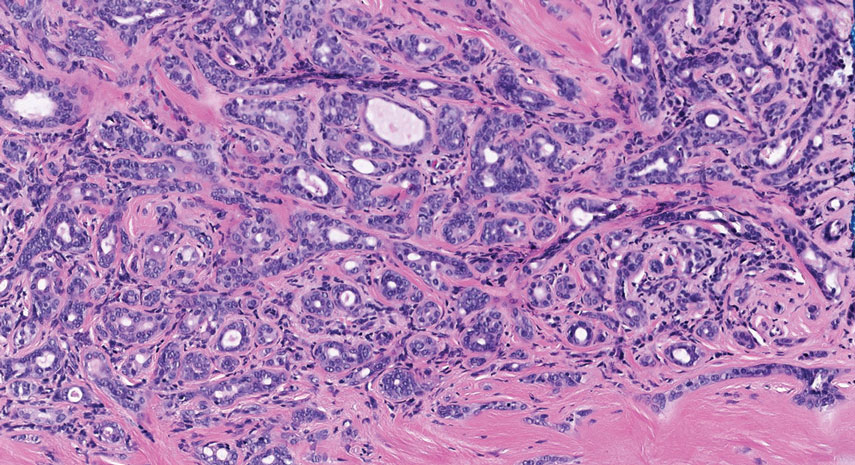

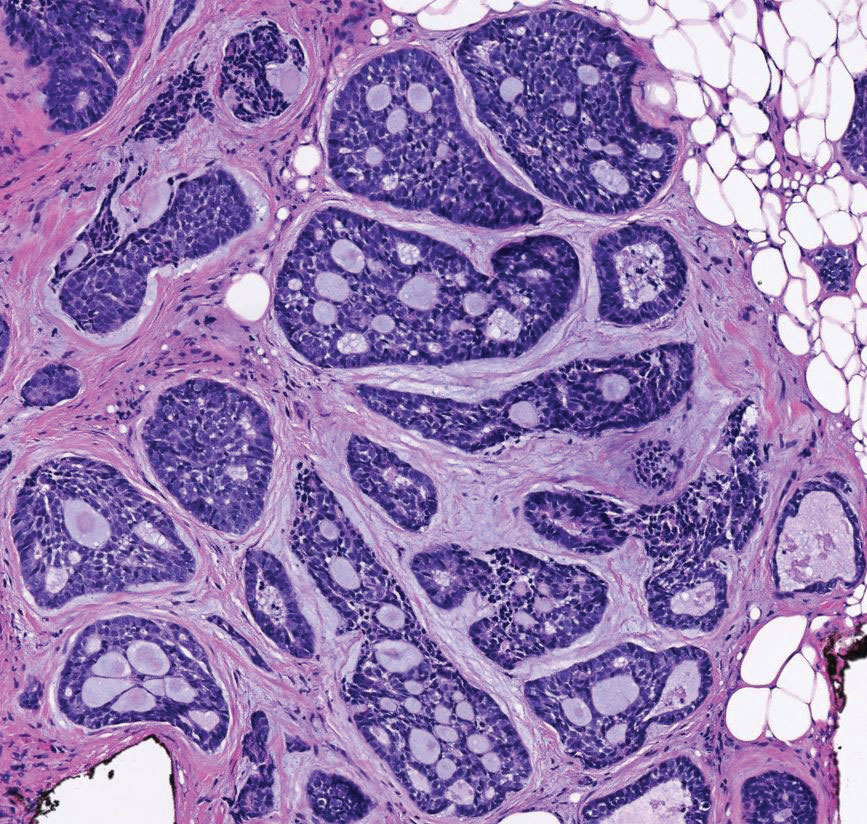

A Vitiligo in a young Hispanic female, which spared the area under a ring. The patient has spotty return of pigment on the hand after narrowband UVB treatment.

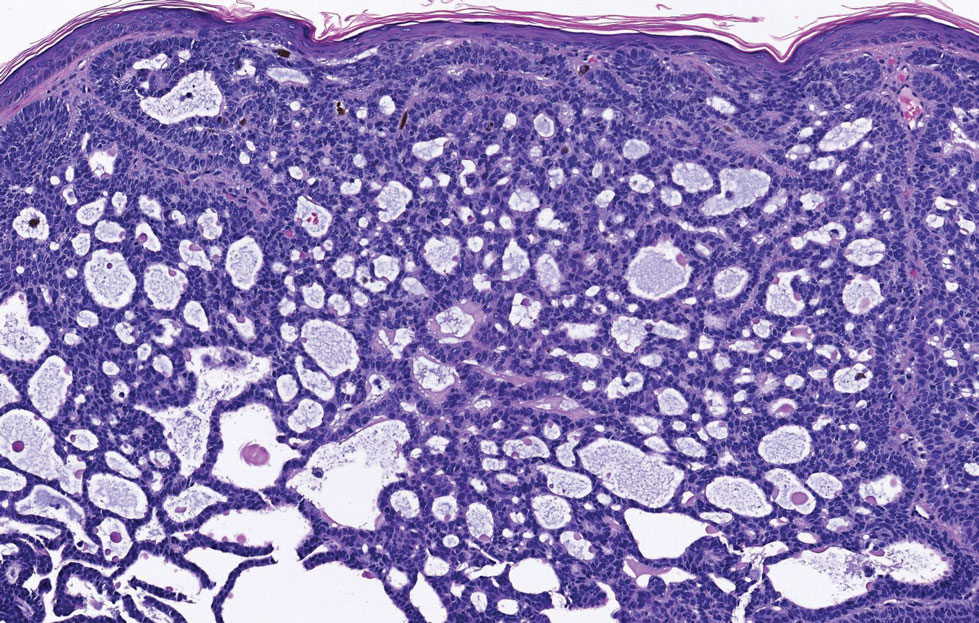

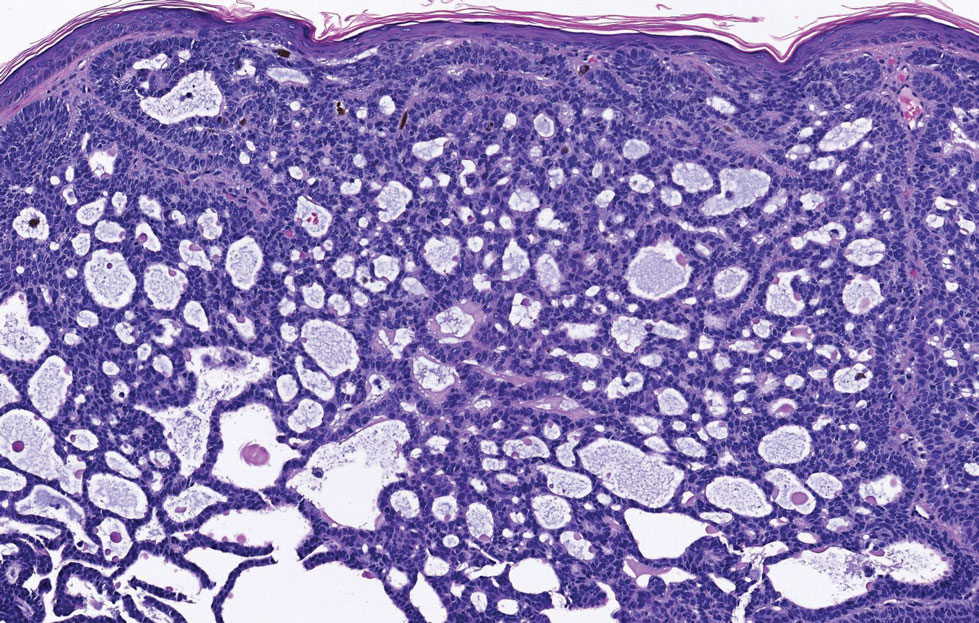

B Vitiligo on the hand in a young Hispanic male.

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by areas of depigmented white patches on the skin due to the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis. Various theories on the pathogenesis of vitiligo exist; however, autoimmune destruction of melanocytes remains the leading hypothesis, followed by intrinsic defects in melanocytes.1 Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune diseases but is most frequently reported in conjunction with thyroid disorders.2

Epidemiology

Vitiligo affects approximately 1% of the US population and up to 8% worldwide.2 There is no difference in prevalence between races or genders. Females typically acquire the disease earlier than males. Onset may occur at any age, although about half of patients will have vitiligo by 20 years of age.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Bright white patches are characteristic of vitiligo. The patches typically are asymptomatic and often affect the hands (Figures A and B), perioral skin, feet, and scalp, as well as areas more vulnerable to friction and trauma, such as the elbows and knees.2 Trichrome lesions—consisting of varying zones of white (depigmented), lighter brown (hypopigmented), and normal skin—are most commonly seen in individuals with darker skin. Trichrome vitiligo is considered an actively progressing variant of vitiligo.2

An important distinction when diagnosing vitiligo is evaluating for segmental vs nonsegmental vitiligo. Although nonsegmental vitiligo—the more common subtype—is characterized by symmetric distribution and a less predictable course, segmental vitiligo manifests in a localized and unilateral distribution, often avoiding extension past the midline. Segmental vitiligo typically manifests at a younger age and follows a more rapidly stabilizing course.3

Worth noting

Given that stark contrasts between pigmented and depigmented lesions are more prominent in darker skin tones, vitiligo can be more socially stigmatizing and psychologically devastating in these patients.4,5

Treatment of vitiligo includes narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, excimer laser, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and surgical melanocyte transplantation.1 In July 2022, ruxolitinib cream 1.5% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years and older.6,7 It is the only FDA-approved therapy for vitiligo. It is thought to work by inhibiting the Janus kinase– signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway.6 However, topical ruxolitinib is expensive, costing more than $2000 for 60 g.8

Health disparity highlight

A 2021 study reviewing the coverage policies of 15 commercial health care insurance companies, 50 BlueCross BlueShield plans, Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs plans found inequities in the insurance coverage patterns for therapies used to treat vitiligo. There were 2 commonly cited reasons for denying coverage for therapies: vitiligo was considered cosmetic and therapies were not FDA approved.7 In comparison, NB-UVB light phototherapy for psoriasis is not considered cosmetic and has a much higher insurance coverage rate.9,10 The out-of-pocket cost for a patient to purchase their own NB-UVB light phototherapy is more than $5000.11 Not all patients of color are economically disadvantaged, but in the United States, Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of poverty (19% and 17%, respectively) compared to their White counterparts (8%).12

Final thoughts

US Food and Drug Administration approval of new drugs or new treatment indications comes after years of research discovery and large-scale trials. This pursuit of new discovery, however, is uneven. Vitiligo has historically been understudied and underfunded for research; this is common among several conditions adversely affecting people of color in the United States.13

- Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.014

- Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R. Segmental vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:145-150. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.005

- Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review [published online September 23, 2021]. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:757-774. doi:10.1007/s40257 -021-00631-6

- FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 19, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients -aged-12-and-older

- Blundell A, Sachar M, Gabel CK, et al. The scope of health insurance coverage of vitiligo treatments in the United States: implications for health care outcomes and disparities in children of color [published online July 16, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021; 38(suppl 2):79-85. doi:10.1111/pde.14714

- Opzelura prices, coupons, and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.drugs.com /price-guide/opzelura#:~:text=Opzelura%20Prices%2C%20 Coupons%20and%20Patient,on%20the%20pharmacy%20you%20visit

- Bhutani T, Liao W. A practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7:31-35.

- Castro Porto Silva Lopes F, Ahmed A. Insurance coverage for phototherapy for vitiligo in comparison to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine. 2022;6:217-224. https://doi.org/10.25251/skin.6.3.6

- Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Home phototherapy for patients with vitiligo: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:451-459. doi:10.2147/CCID.S185798

- Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau. September 14, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

- Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003263.pub4

THE COMPARISON

A Vitiligo in a young Hispanic female, which spared the area under a ring. The patient has spotty return of pigment on the hand after narrowband UVB treatment.

B Vitiligo on the hand in a young Hispanic male.

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by areas of depigmented white patches on the skin due to the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis. Various theories on the pathogenesis of vitiligo exist; however, autoimmune destruction of melanocytes remains the leading hypothesis, followed by intrinsic defects in melanocytes.1 Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune diseases but is most frequently reported in conjunction with thyroid disorders.2

Epidemiology

Vitiligo affects approximately 1% of the US population and up to 8% worldwide.2 There is no difference in prevalence between races or genders. Females typically acquire the disease earlier than males. Onset may occur at any age, although about half of patients will have vitiligo by 20 years of age.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Bright white patches are characteristic of vitiligo. The patches typically are asymptomatic and often affect the hands (Figures A and B), perioral skin, feet, and scalp, as well as areas more vulnerable to friction and trauma, such as the elbows and knees.2 Trichrome lesions—consisting of varying zones of white (depigmented), lighter brown (hypopigmented), and normal skin—are most commonly seen in individuals with darker skin. Trichrome vitiligo is considered an actively progressing variant of vitiligo.2

An important distinction when diagnosing vitiligo is evaluating for segmental vs nonsegmental vitiligo. Although nonsegmental vitiligo—the more common subtype—is characterized by symmetric distribution and a less predictable course, segmental vitiligo manifests in a localized and unilateral distribution, often avoiding extension past the midline. Segmental vitiligo typically manifests at a younger age and follows a more rapidly stabilizing course.3

Worth noting

Given that stark contrasts between pigmented and depigmented lesions are more prominent in darker skin tones, vitiligo can be more socially stigmatizing and psychologically devastating in these patients.4,5

Treatment of vitiligo includes narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, excimer laser, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and surgical melanocyte transplantation.1 In July 2022, ruxolitinib cream 1.5% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years and older.6,7 It is the only FDA-approved therapy for vitiligo. It is thought to work by inhibiting the Janus kinase– signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway.6 However, topical ruxolitinib is expensive, costing more than $2000 for 60 g.8

Health disparity highlight

A 2021 study reviewing the coverage policies of 15 commercial health care insurance companies, 50 BlueCross BlueShield plans, Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs plans found inequities in the insurance coverage patterns for therapies used to treat vitiligo. There were 2 commonly cited reasons for denying coverage for therapies: vitiligo was considered cosmetic and therapies were not FDA approved.7 In comparison, NB-UVB light phototherapy for psoriasis is not considered cosmetic and has a much higher insurance coverage rate.9,10 The out-of-pocket cost for a patient to purchase their own NB-UVB light phototherapy is more than $5000.11 Not all patients of color are economically disadvantaged, but in the United States, Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of poverty (19% and 17%, respectively) compared to their White counterparts (8%).12

Final thoughts

US Food and Drug Administration approval of new drugs or new treatment indications comes after years of research discovery and large-scale trials. This pursuit of new discovery, however, is uneven. Vitiligo has historically been understudied and underfunded for research; this is common among several conditions adversely affecting people of color in the United States.13

THE COMPARISON

A Vitiligo in a young Hispanic female, which spared the area under a ring. The patient has spotty return of pigment on the hand after narrowband UVB treatment.

B Vitiligo on the hand in a young Hispanic male.

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by areas of depigmented white patches on the skin due to the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis. Various theories on the pathogenesis of vitiligo exist; however, autoimmune destruction of melanocytes remains the leading hypothesis, followed by intrinsic defects in melanocytes.1 Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune diseases but is most frequently reported in conjunction with thyroid disorders.2

Epidemiology

Vitiligo affects approximately 1% of the US population and up to 8% worldwide.2 There is no difference in prevalence between races or genders. Females typically acquire the disease earlier than males. Onset may occur at any age, although about half of patients will have vitiligo by 20 years of age.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Bright white patches are characteristic of vitiligo. The patches typically are asymptomatic and often affect the hands (Figures A and B), perioral skin, feet, and scalp, as well as areas more vulnerable to friction and trauma, such as the elbows and knees.2 Trichrome lesions—consisting of varying zones of white (depigmented), lighter brown (hypopigmented), and normal skin—are most commonly seen in individuals with darker skin. Trichrome vitiligo is considered an actively progressing variant of vitiligo.2

An important distinction when diagnosing vitiligo is evaluating for segmental vs nonsegmental vitiligo. Although nonsegmental vitiligo—the more common subtype—is characterized by symmetric distribution and a less predictable course, segmental vitiligo manifests in a localized and unilateral distribution, often avoiding extension past the midline. Segmental vitiligo typically manifests at a younger age and follows a more rapidly stabilizing course.3

Worth noting

Given that stark contrasts between pigmented and depigmented lesions are more prominent in darker skin tones, vitiligo can be more socially stigmatizing and psychologically devastating in these patients.4,5

Treatment of vitiligo includes narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, excimer laser, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and surgical melanocyte transplantation.1 In July 2022, ruxolitinib cream 1.5% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nonsegmental vitiligo in patients 12 years and older.6,7 It is the only FDA-approved therapy for vitiligo. It is thought to work by inhibiting the Janus kinase– signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway.6 However, topical ruxolitinib is expensive, costing more than $2000 for 60 g.8

Health disparity highlight

A 2021 study reviewing the coverage policies of 15 commercial health care insurance companies, 50 BlueCross BlueShield plans, Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs plans found inequities in the insurance coverage patterns for therapies used to treat vitiligo. There were 2 commonly cited reasons for denying coverage for therapies: vitiligo was considered cosmetic and therapies were not FDA approved.7 In comparison, NB-UVB light phototherapy for psoriasis is not considered cosmetic and has a much higher insurance coverage rate.9,10 The out-of-pocket cost for a patient to purchase their own NB-UVB light phototherapy is more than $5000.11 Not all patients of color are economically disadvantaged, but in the United States, Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of poverty (19% and 17%, respectively) compared to their White counterparts (8%).12

Final thoughts

US Food and Drug Administration approval of new drugs or new treatment indications comes after years of research discovery and large-scale trials. This pursuit of new discovery, however, is uneven. Vitiligo has historically been understudied and underfunded for research; this is common among several conditions adversely affecting people of color in the United States.13

- Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.014

- Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R. Segmental vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:145-150. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.005

- Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review [published online September 23, 2021]. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:757-774. doi:10.1007/s40257 -021-00631-6

- FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 19, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients -aged-12-and-older

- Blundell A, Sachar M, Gabel CK, et al. The scope of health insurance coverage of vitiligo treatments in the United States: implications for health care outcomes and disparities in children of color [published online July 16, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021; 38(suppl 2):79-85. doi:10.1111/pde.14714

- Opzelura prices, coupons, and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.drugs.com /price-guide/opzelura#:~:text=Opzelura%20Prices%2C%20 Coupons%20and%20Patient,on%20the%20pharmacy%20you%20visit

- Bhutani T, Liao W. A practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7:31-35.

- Castro Porto Silva Lopes F, Ahmed A. Insurance coverage for phototherapy for vitiligo in comparison to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine. 2022;6:217-224. https://doi.org/10.25251/skin.6.3.6

- Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Home phototherapy for patients with vitiligo: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:451-459. doi:10.2147/CCID.S185798

- Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau. September 14, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

- Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003263.pub4

- Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.014

- Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061

- van Geel N, Speeckaert R. Segmental vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:145-150. doi:10.1016/j.det.2016.11.005

- Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-37. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005

- Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review [published online September 23, 2021]. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:757-774. doi:10.1007/s40257 -021-00631-6

- FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 19, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical-treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients -aged-12-and-older

- Blundell A, Sachar M, Gabel CK, et al. The scope of health insurance coverage of vitiligo treatments in the United States: implications for health care outcomes and disparities in children of color [published online July 16, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021; 38(suppl 2):79-85. doi:10.1111/pde.14714

- Opzelura prices, coupons, and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com. Accessed January 10, 2023. https://www.drugs.com /price-guide/opzelura#:~:text=Opzelura%20Prices%2C%20 Coupons%20and%20Patient,on%20the%20pharmacy%20you%20visit

- Bhutani T, Liao W. A practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7:31-35.

- Castro Porto Silva Lopes F, Ahmed A. Insurance coverage for phototherapy for vitiligo in comparison to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine. 2022;6:217-224. https://doi.org/10.25251/skin.6.3.6

- Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Home phototherapy for patients with vitiligo: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:451-459. doi:10.2147/CCID.S185798

- Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau. September 14, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

- Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003263.pub4

Janus Kinase Inhibitors: A Promising Therapeutic Option for Allergic Contact Dermatitis

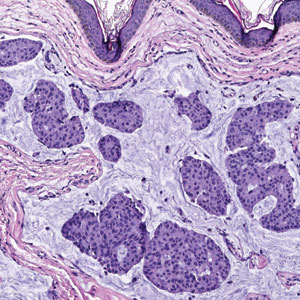

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

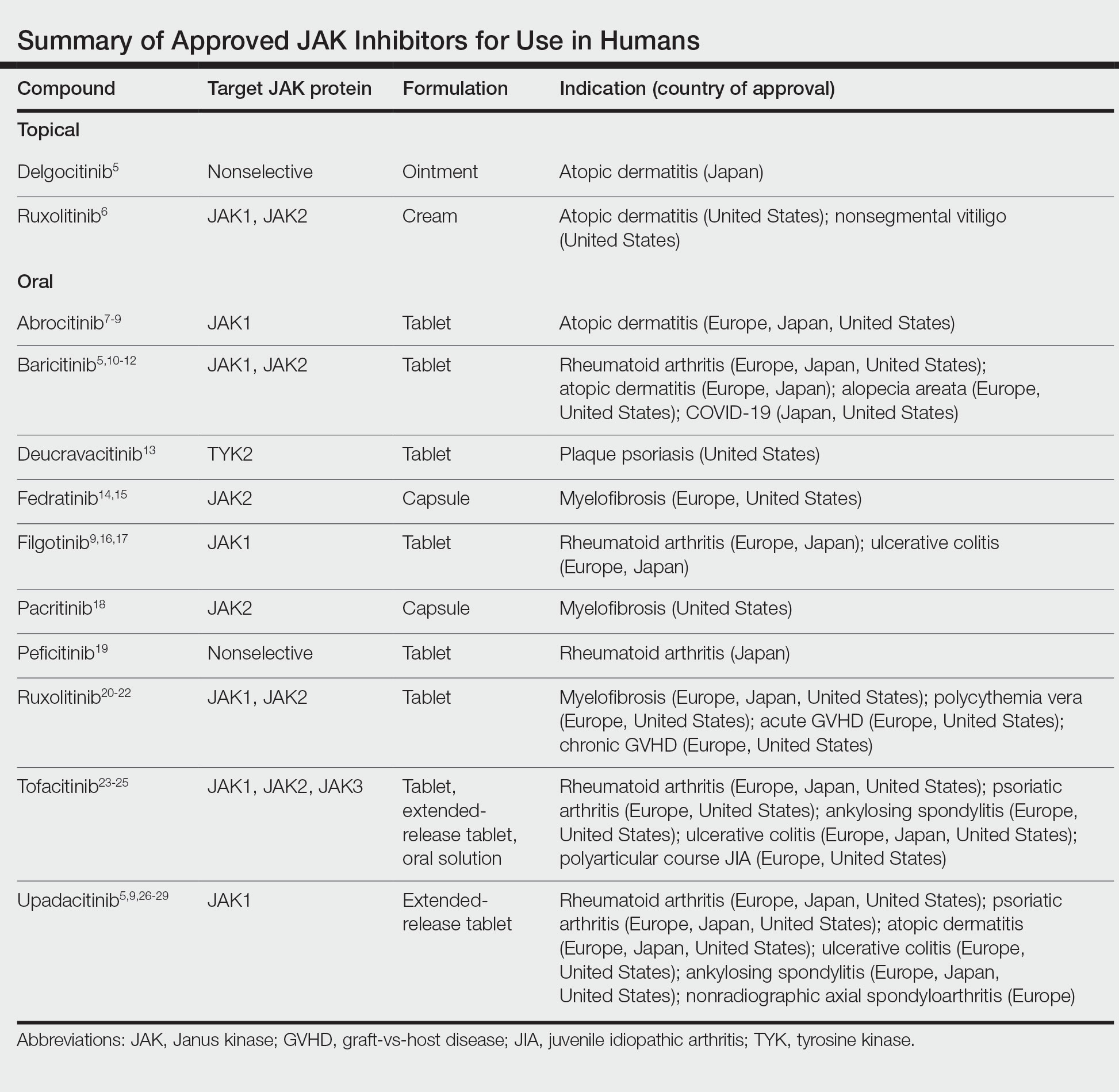

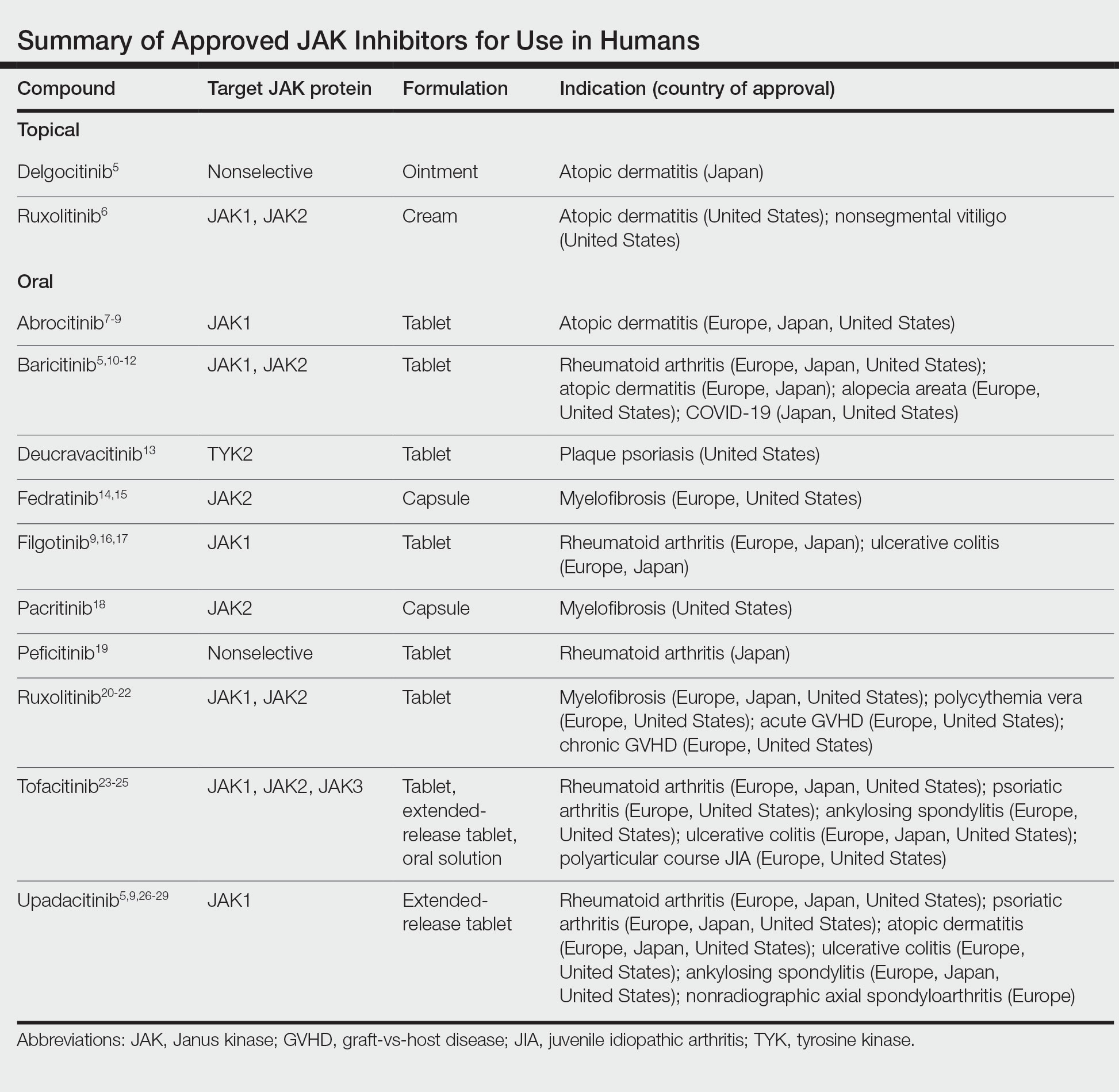

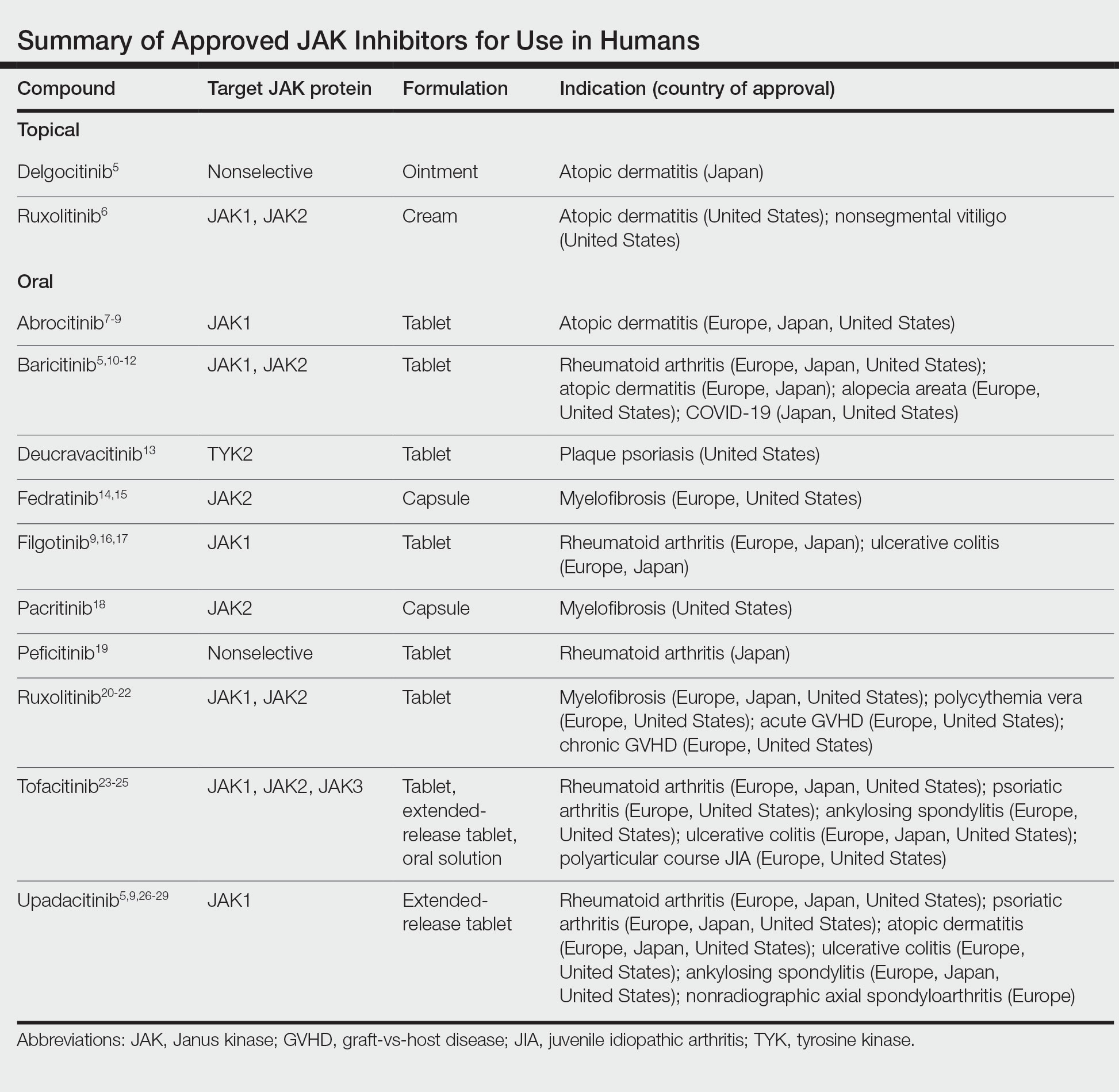

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf

- Jakavi. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published October 4, 2012. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi

- New drugs approved in FY 2014. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000229076.pdf

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/203214s028,208246s013,213082s003lbl.pdf

- Xeljanz. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Xeljanz. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000237584.pdf

- Rinvoq (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf

- Rinvoq. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 18, 2019. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq

- New drugs approved in FY 2019. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235289.pdfs

- New drugs approved in May 2022. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000248626.pdf

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:823-831. Erratum appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1069.

- Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4974.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:863-872.

- Radi G, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Baricitinib: the first Jak inhibitor approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1575.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. Erratum appears in Lancet. 2021;397:2150.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142.

- Amano W, Nakajima S, Yamamoto Y, et al. JAK inhibitor JTE-052 regulates contact hypersensitivity by downmodulating T cell activation and differentiation. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:258-265.

- O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328.

- Bechara R, Antonios D, Azouri H, et al. Nickel sulfate promotes IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells by an IL-23-dependent mechanism regulated by TLR4 and JAK-STAT pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2140-2148.

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171:217-228.e13.

- Fujii Y, Sengoku T. Effects of the Janus kinase inhibitor CP-690550 (tofacitinib) in a rat model of oxazolone-induced chronic dermatitis. Pharmacology. 2013;91:207-213.

- Fukuyama T, Ehling S, Cook E, et al. Topically administered Janus-kinase inhibitors tofacitinib and oclacitinib display impressive antipruritic and anti-inflammatory responses in a model of allergic dermatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:394-405.

- Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:479, E114.

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544.

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis [published online October 12, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Worm M, Bauer A, Elsner P, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical delgocitinib in patients with chronic hand eczema: data from a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1103-1110.

- Chen J, Cheng J, Yang H, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:495-496.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Updated December 7, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, et al. Association of risk of incident venous thromboembolism with atopic dermatitis and treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1254-1261.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:395-405.

- Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, et al. Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: a consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:71-87.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. The suitability of treating atopic dermatitis with Janus kinase inhibitors. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:439-459.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction that usually manifests with eczematous lesions within hours to days after exposure to a contact allergen. The primary treatment of ACD consists of allergen avoidance, but medications also may be necessary to manage symptoms, particularly in cases where avoidance alone does not lead to resolution of dermatitis. At present, no medical therapies are explicitly approved for use in the management of ACD. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors are a class of small molecule inhibitors that are used for the treatment of a range of inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Several oral and topical JAK inhibitors also have recently been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for atopic dermatitis (AD). In this article, we discuss this important class of medications and the role that they may play in the off-label management of refractory ACD.

JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway

The JAK/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway plays a crucial role in many biologic processes. Notably, JAK/STAT signaling is involved in the development and regulation of the immune system.1 The cascade begins when a particular transmembrane receptor binds a ligand, such as an interferon or interleukin.2 Upon ligand binding, the receptor dimerizes or oligomerizes, bringing the relevant JAK proteins into close approximation to each other.3 This allows the JAK proteins to autophosphorylate or transphosphorylate.2-4 Phosphorylation activates the JAK proteins and increases their kinase activity.3 In humans, there are 4 JAK proteins: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2.4 When activated, the JAK proteins phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues on the receptor, which creates a docking site for STAT proteins. After binding, the STAT proteins then are phosphorylated, leading to their dimerization and translocation to the nucleus.2,3 Once in the nucleus, the STAT proteins act as transcription factors for target genes.3

JAK Inhibitors

Janus kinase inhibitors are immunomodulatory medications that work through inhibition of 1 or more of the JAK proteins in the JAK/STAT pathway. Through this mechanism, JAK inhibitors can impede the activity of proinflammatory cytokines and T cells.4 A brief overview of the commercially available JAK inhibitors in Europe, Japan, and the United States is provided in the Table.5-29

Of the approved JAK inhibitors, more than 40% are indicated for AD. The first JAK inhibitor to be approved in the topical form was delgocitinib in 2020 in Japan.5 In a phase 3 trial, delgocitinib demonstrated significant reductions in modified Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) score (P<.001) as well as Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) when compared with vehicle.30 Topical ruxolitinib soon followed when its approval for AD was announced by the FDA in 2021.31 Results from 2 phase 3 trials found that significantly more patients achieved investigator global assessment (IGA) treatment success (P<.0001) and a significant reduction in itch as measured by the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (P<.001) with topical ruxolitinib vs vehicle.32

The first oral JAK inhibitor to attain approval for AD was baricitinib in Europe and Japan, but it is not currently approved for this indication in the United States by the FDA.11,12,33 Consistent findings across phase 3 trials revealed that baricitinib was more effective at achieving IGA treatment success and improved EASI scores compared with placebo.33

Upadacitinib, another oral JAK inhibitor, was subsequently approved for AD in Europe and Japan in 2021 and in the United States in early 2022.5,9,26,27 Two replicate phase 3 trials demonstrated significant improvement in EASI score, itch, and quality of life with upadacitinib compared with placebo (P<.0001).34 Abrocitinib was granted FDA approval for AD in the same time period, with phase 3 trials exhibiting greater responses in IGA and EASI scores vs placebo.35

Potential for Use in ACD

Given the successful use of JAK inhibitors in the management of AD, there is optimism that these medications also may have potential application in ACD. Recent literature suggests that the 2 conditions may be more closely related mechanistically than previously understood. As a result, AD and ACD often are managed with the same therapeutic agents.36

Although the exact etiology of ACD is still being elucidated, activation of T cells and cytokines plays an important role.37 Notably, more than 40 cytokines exert their effects through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, including IL-2, IL-6, IL-17, IL-22, and IFN-γ.37,38 A study on nickel contact allergy revealed that JAK/STAT activation may regulate the balance between IL-12 and IL-23 and increase type 1 T-helper (TH1) polarization.39 Skin inflammation and chronic pruritus, which are major components of ACD, also are thought to be mediated in part by JAK signaling.34,40

Animal studies have suggested that JAK inhibitors may show benefit in the management of ACD. Rats with oxazolone-induced ACD were found to have less swelling and epidermal thickening in the area of induced dermatitis after treatment with oral tofacitinib, comparable to the effects of cyclosporine. Tofacitinib was presumed to exert its effects through cytokine suppression, particularly that of IFN-γ, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor α.41 In a separate study on mice with toluene-2,4-diisocyanate–induced ACD, both tofacitinib and another JAK inhibitor, oclacitinib, demonstrated inhibition of cytokine production, migration, and maturation of bone marrow–derived dendritic cells. Both topical and oral formulations of these 2 JAK inhibitors also were found to decrease scratching behavior; only the topicals improved ear thickness (used as a marker of skin inflammation), suggesting potential benefits to local application.42 In a murine model, oral delgocitinib also attenuated contact hypersensitivity via inhibition of antigen-specific T-cell proliferation and cytokine production.37 Finally, in a randomized clinical trial conducted on dogs with allergic dermatitis (of which 10% were presumed to be from contact allergy), oral oclacitinib significantly reduced pruritus and clinical severity scores vs placebo (P<.0001).43

There also are early clinical studies and case reports highlighting the effective use of JAK inhibitors in the management of ACD in humans. A 37-year-old man with occupational airborne ACD to Compositae saw full clearance of his dermatitis with daily oral abrocitinib after topical corticosteroids and dupilumab failed.44 Another patient, a 57-year-old woman, had near-complete resolution of chronic Parthenium-induced airborne ACD after starting twice-daily oral tofacitinib. Allergen avoidance, as well as multiple medications, including topical and oral corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, and azathioprine, previously failed in this patient.45 Finally, a phase 2 study on patients with irritant and nonirritant chronic hand eczema found that significantly more patients achieved treatment success (as measured by the physician global assessment) with topical delgocitinib vs vehicle (P=.009).46 Chronic hand eczema may be due to a variety of causes, including AD, irritant contact dermatitis, and ACD. Thus, these studies begin to highlight the potential role for JAK inhibitors in the management of refractory ACD.

Side Effects of JAK Inhibitors

The safety profile of JAK inhibitors must be taken into consideration. In general, topical JAK inhibitors are safe and well tolerated, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) seen in clinical trials considered mild or unrelated to the medication.30,32 Nasopharyngitis, local skin infection, and acne were reported; a systematic review found no increased risk of AEs with topical JAK inhibitors compared with placebo.30,32,47 Application-site reactions, a common concern among the existing topical calcineurin and phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, were rare (approximately 2% of patients).47 The most frequent AEs seen in clinical trials of oral JAK inhibitors included acne, nasopharyngitis/upper respiratory tract infections, nausea, and headache.33-35 Herpes simplex virus infection and worsening of AD also were seen. Although elevations in creatine phosphokinase levels were reported, patients often were asymptomatic and elevations were related to exercise or resolved without treatment interruption.33-35

As a class, JAK inhibitors carry a boxed warning for serious infections, malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, thrombosis, and mortality. The FDA placed this label on JAK inhibitors because of the results of a randomized controlled trial of oral tofacitinib vs tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors in RA.48,49 Notably, participants in the trial had to be 50 years or older and have at least 1 additional cardiovascular risk factor. Postmarket safety data are still being collected for patients with AD and other dermatologic conditions, but the findings of safety analyses have been reassuring to date.50,51 Regular follow-up and routine laboratory monitoring are recommended for any patient started on an oral JAK inhibitor, which often includes monitoring of the complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and lipids, as well as baseline screening for tuberculosis and hepatitis.52,53 For topical JAK inhibitors, no specific laboratory monitoring is recommended.

Finally, it must be considered that the challenges of off-label prescribing combined with high costs may limit access to JAK inhibitors for use in ACD.

Final Interpretation

Early investigations, including studies on animals and humans, suggest that JAK inhibitors are a promising option in the management of treatment-refractory ACD. Patients and providers should be aware of both the benefits and known side effects of JAK inhibitors prior to treatment initiation.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf

- Jakavi. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published October 4, 2012. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi

- New drugs approved in FY 2014. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000229076.pdf

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/203214s028,208246s013,213082s003lbl.pdf

- Xeljanz. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Xeljanz. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000237584.pdf

- Rinvoq (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf

- Rinvoq. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 18, 2019. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq

- New drugs approved in FY 2019. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235289.pdfs

- New drugs approved in May 2022. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000248626.pdf

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:823-831. Erratum appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1069.

- Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4974.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:863-872.

- Radi G, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Baricitinib: the first Jak inhibitor approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1575.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. Erratum appears in Lancet. 2021;397:2150.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142.

- Amano W, Nakajima S, Yamamoto Y, et al. JAK inhibitor JTE-052 regulates contact hypersensitivity by downmodulating T cell activation and differentiation. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:258-265.

- O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328.

- Bechara R, Antonios D, Azouri H, et al. Nickel sulfate promotes IL-17A producing CD4+ T cells by an IL-23-dependent mechanism regulated by TLR4 and JAK-STAT pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:2140-2148.

- Oetjen LK, Mack MR, Feng J, et al. Sensory neurons co-opt classical immune signaling pathways to mediate chronic itch. Cell. 2017;171:217-228.e13.

- Fujii Y, Sengoku T. Effects of the Janus kinase inhibitor CP-690550 (tofacitinib) in a rat model of oxazolone-induced chronic dermatitis. Pharmacology. 2013;91:207-213.

- Fukuyama T, Ehling S, Cook E, et al. Topically administered Janus-kinase inhibitors tofacitinib and oclacitinib display impressive antipruritic and anti-inflammatory responses in a model of allergic dermatitis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;354:394-405.

- Cosgrove SB, Wren JA, Cleaver DM, et al. Efficacy and safety of oclacitinib for the control of pruritus and associated skin lesions in dogs with canine allergic dermatitis. Vet Dermatol. 2013;24:479, E114.

- Baltazar D, Shinamoto SR, Hamann CP, et al. Occupational airborne allergic contact dermatitis to invasive Compositae species treated with abrocitinib: a case report. Contact Dermatitis. 2022;87:542-544.

- Muddebihal A, Sardana K, Sinha S, et al. Tofacitinib in refractory Parthenium-induced airborne allergic contact dermatitis [published online October 12, 2022]. Contact Dermatitis. doi:10.1111/cod.14234

- Worm M, Bauer A, Elsner P, et al. Efficacy and safety of topical delgocitinib in patients with chronic hand eczema: data from a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182:1103-1110.

- Chen J, Cheng J, Yang H, et al. The efficacy and safety of Janus kinase inhibitors in patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:495-496.

- Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, et al. Cardiovascular and cancer risk with tofacitinib in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:316-326.

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA requires warnings about increased risk of serious heart-related events, cancer, blood clots, and death for JAK inhibitors that treat certain chronic inflammatory conditions. Updated December 7, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-warnings-about-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-events-cancer-blood-clots-and-death

- Chen TL, Lee LL, Huang HK, et al. Association of risk of incident venous thromboembolism with atopic dermatitis and treatment with Janus kinase inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1254-1261.

- King B, Maari C, Lain E, et al. Extended safety analysis of baricitinib 2 mg in adult patients with atopic dermatitis: an integrated analysis from eight randomized clinical trials. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:395-405.

- Nash P, Kerschbaumer A, Dörner T, et al. Points to consider for the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases with Janus kinase inhibitors: a consensus statement. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:71-87.

- Narla S, Silverberg JI. The suitability of treating atopic dermatitis with Janus kinase inhibitors. Exp Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:439-459.

- Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases in immune cell signaling. Immunol Rev. 2009;228:273-287.

- Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. “Do we know Jack” about JAK? a closer look at JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287.

- Jatiani SS, Baker SJ, Silverman LR, et al. Jak/STAT pathways in cytokine signaling and myeloproliferative disorders: approaches for targeted therapies. Genes Cancer. 2010;1:979-993.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2017;15:23.

- Traidl S, Freimooser S, Werfel T. Janus kinase inhibitors for the therapy of atopic dermatitis. Allergol Select. 2021;5:293-304.

- Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215309s001lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo (abrocitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/213871s000lbl.pdf

- Cibinqo. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 17, 2021. Updated November 10, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/cibinqo

- New drugs approved in FY 2021. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000246734.pdf

- Olumiant (baricitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Eli Lilly and Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/207924s007lbl.pdf

- Olumiant. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 16, 2017. Updated June 29, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant

- Review report: Olumiant. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. April 21, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000243207.pdf

- Sotyktu (deucravacitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023.https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/214958s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic (fedratinib) capsules. Prescribing information. Celgene Corporation; 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212327s000lbl.pdf

- Inrebic. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published March 3, 2021. Updated December 8, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/inrebic

- Jyseleca. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published September 28, 2020. Updated November 9, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/jyseleca-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Jyseleca. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. September 8, 2020. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000247830.pdf

- Vonjo (pacritinib) capsules. Prescribing information. CTI BioPharma Corp; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/208712s000lbl.pdf

- Review report: Smyraf. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. February 28, 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233074.pdf

- Jakafi (ruxolitinib) tablets. Prescribing information. Incyte Corporation; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/202192s023lbl.pdf

- Jakavi. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published October 4, 2012. Updated May 18, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/jakavi

- New drugs approved in FY 2014. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000229076.pdf

- Xeljanz (tofacitinib). Prescribing information. Pfizer Labs; 2021. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/203214s028,208246s013,213082s003lbl.pdf

- Xeljanz. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/xeljanz-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- Review report: Xeljanz. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000237584.pdf

- Rinvoq (upadacitinib) extended-release tablets. Prescribing information. AbbVie Inc; 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/211675s003lbl.pdf

- Rinvoq. Product information. European Medicines Agency. Published December 18, 2019. Updated December 7, 2022. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/rinvoq

- New drugs approved in FY 2019. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000235289.pdfs

- New drugs approved in May 2022. Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. Accessed January 20, 2023. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000248626.pdf

- Nakagawa H, Nemoto O, Igarashi A, et al. Delgocitinib ointment, a topical Janus kinase inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study and an open-label, long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:823-831. Erratum appears in J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1069.

- Sideris N, Paschou E, Bakirtzi K, et al. New and upcoming topical treatments for atopic dermatitis: a review of the literature. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4974.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Efficacy and safety of ruxolitinib cream for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: results from 2 phase 3, randomized, double-blind studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:863-872.

- Radi G, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Baricitinib: the first Jak inhibitor approved in Europe for the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adult patients. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1575.

- Guttman-Yassky E, Teixeira HD, Simpson EL, et al. Once-daily upadacitinib versus placebo in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (Measure Up 1 and Measure Up 2): results from two replicate double-blind, randomised controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2021;397:2151-2168. Erratum appears in Lancet. 2021;397:2150.

- Bieber T, Simpson EL, Silverberg JI, et al. Abrocitinib versus placebo or dupilumab for atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1101-1112.

- Johnson H, Novack DE, Adler BL, et al. Can atopic dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis coexist? Cutis. 2022;110:139-142.

- Amano W, Nakajima S, Yamamoto Y, et al. JAK inhibitor JTE-052 regulates contact hypersensitivity by downmodulating T cell activation and differentiation. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;84:258-265.

- O’Shea JJ, Schwartz DM, Villarino AV, et al. The JAK-STAT pathway: impact on human disease and therapeutic intervention. Annu Rev Med. 2015;66:311-328.