User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Nail dystrophy and foot pain

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

These findings are consistent with a type of heritable keratoderma called pachyonychia congenita (also called twenty-nails dystrophy). It is easy to mistake this unusual cause of thickening nails with a more common cause: onychomycosis.

Pachyonychia congenita describes a set of disorders driven by heritable defects in 1 of 5 keratin genes. The disorder is often transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, although a third of patients are thought to have a spontaneous mutation.1 These gene changes can cause 1 or multiple dystrophic nails, thickened nail beds, natal teeth, thick plantar or palmar nodules or plaques, and hearing difficulties. Some patients may have symptoms at birth, while other patients do not develop symptoms until later in life.1

There is currently no cure for pachyonychia congenita. Patients with suspected heritable keratoderma benefit from referral to Medical Genetics and a dermatologist who is comfortable treating keratodermas. Patients can obtain free genetic testing, educational material, and additional resources through pachyonychia.org.

This patient was prescribed topical urea 40% cream that was to be applied to the feet nightly, until the nodules became less painful. He was also evaluated for pressure-offloading orthotics. Nails may be treated with topical urea lacquer nightly until patients are satisfied with the appearance, although this patient chose to forgo the lacquer.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

1. Smith FJD, Hansen CD, Hull PR, et al. Pachyonychia congenita. In: Adam MP, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, et al., eds. GeneReviews. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 2006. Updated November 30, 2017. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1280/

Skin reactions after COVID-19 vaccination have six patterns

Skin manifestations of COVID-19 were among the topics presented in several sessions at the 49th Congress of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Specialists agreed that fewer skin changes associated with this virus have been seen with the latest variants of SARS-CoV-2. They highlighted the results of the most remarkable research on this topic that were presented in this forum.

In the study, which was carried out by Spanish dermatologists with the support of the AEDV, researchers analyzed skin reactions associated with the COVID-19 vaccine.

Study author Cristina Galván, MD, a dermatologist at the University Hospital of Móstoles, Madrid, said, of the dermatological manifestations caused as a reaction to these vaccines.”

The study was carried out during the first months of COVID-19 vaccination, Dr. Galván told this news organization. It was proposed as a continuation of a COVID skin study that was published in the British Journal of Dermatology. That study documented the first classification of skin lesions associated with COVID-19. Dr. Galván is the lead author of the latter study.

“The objectives of this study were to characterize and classify skin reactions after vaccination, identify their chronology, and analyze the associations with a series of antecedents: dermatological and allergic diseases, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, and skin reactions associated with COVID-19,” said Dr. Galván. The study was a team effort, she added.

“It was conducted between Feb. 15 and May 12, 2021, and information was gathered on 405 reactions that appeared during the 21 days after any dose of the COVID-19 vaccines approved at that time in Spain: the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and University of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines,” she added.

Dr. Galván explained that the study shows very clear patterns and investigators reached conclusions that match those of other groups that have investigated this topic. “Six reaction patterns were described according to their frequency. The first is the ‘COVID-19 arm,’ which consists of a local reaction at the injection site and occurs almost exclusively in women and in 70% of cases after inoculation with the Moderna serum. It is a manifestation that resolves well and does not always recur in subsequent doses. More than half are of delayed onset: biopsied patients show signs of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. In line with all the publications in this regard, it was found that this reaction is not a reason to skip or delay a dose.”

Herpes zoster reactivation

The second pattern is urticarial, which, according to the specialist, occurs with equal frequency after the administration of all vaccines and is well controlled with antihistamines. “This is a very nonspecific pattern, which does not prevent it from still being frequent. It was not associated with drug intake.

“The morbilliform pattern is more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. It affects the trunk and extremities, and up to a quarter of the cases required systemic corticosteroids. The papulovesicular and pityriasis rosea–like patterns are equally frequent in all vaccines. The latter is found in a younger age group. Finally, there is the purpuric pattern, more localized in the extremities and more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. On biopsy, this pattern showed small-vessel vasculitis.”

Less frequently, reactivations or de novo onset of different dermatologic diseases were found. “Varicella-zoster virus reactivations were observed with a frequency of 13.8%, being more common after the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine,” said Dr. Galván. “Other studies have corroborated this increase in herpes zoster, although it has been seen that the absolute number is low, so the benefits of the vaccine outweigh this eventual complication. At the same time and along the same lines, vaccination against herpes zoster is recommended for those over 50 years of age.”

Another fact revealed by the study is that these reactions were not significantly more severe in people with dermatologic diseases, those with previous infection, or those with skin manifestation associated with COVID-19.

Dr. Galván highlighted that, except for the COVID-19 arm, these patterns were among those associated with the disease, “which supports [the idea] that it does not demonstrate that the host’s immune reaction to the infection was playing a role.”

Women and young people

“As for pseudoperniosis, it is poorly represented in our series: 0.7% compared to 2% in the American registry. Although neither the SARS-CoV-2–pseudoperniosis association nor its pathophysiology is clear, the idea is that if this manifestation is related to the host’s immune response during infection, pseudoperniosis after vaccination could also be linked to the immune response to the vaccine,” said Dr. Galván.

Many of these reactions are more intense in women. “Before starting to use these vaccines, we already knew that messenger RNA vaccines (a powerful activator of innate immunity) induce frequent reactions, that adjuvants and excipients (polyethylene glycol and polysorbate) also generate them, and that other factors influence reactogenicity, among those of us of the same age and sex, reactions being more frequent in younger people and in women,” said Dr. Galván. “This may be one of the reasons why the COVID-19 arm is so much more prevalent in the female population and that 80% of all reactions that were collected were in women.”

In relation to the fact that manifestations differed, depending on the type of inoculated serum, Dr. Galván said, “Some reactions are just as common after any of the vaccines. However, others are not, as is the case with the COVID-19 arm for the Moderna vaccine or reactivations of the herpes virus, more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

“Undoubtedly, behind these differences are particularities in the immune reaction caused by each of the vaccines and their composition, including the excipients,” she said.

Regarding the fact that these reactions were the same throughout the vaccine regimen or that they varied in intensity, depending on the dose, Dr. Galván said, “In our study, as in those carried out by other groups, there were no significant differences in terms of frequency after the first and second doses. One thing to keep in mind is that, due to the temporary design of our study and the time at which it was conducted, it was not possible to collect reactions after second doses of AstraZeneca.

“Manifestations have generally been mild and well controlled. Many of them did not recur after the second dose, and the vast majority did not prevent completion of the vaccination scheme, but we must not lose sight of the fact that 20% of these manifestations were assessed by the dermatologist as serious or very serious,” Dr. Galván added.

Regarding the next steps planned for this line of research, Dr. Galván commented, “We are awaiting the evolution of the reported cases and the reactions that may arise, although for now, our group does not have any open studies. The most important thing now is to be alert and report the data observed in the pharmacovigilance systems, in open registries, and in scientific literature to generate evidence.”

Dr. Galván has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Skin manifestations of COVID-19 were among the topics presented in several sessions at the 49th Congress of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Specialists agreed that fewer skin changes associated with this virus have been seen with the latest variants of SARS-CoV-2. They highlighted the results of the most remarkable research on this topic that were presented in this forum.

In the study, which was carried out by Spanish dermatologists with the support of the AEDV, researchers analyzed skin reactions associated with the COVID-19 vaccine.

Study author Cristina Galván, MD, a dermatologist at the University Hospital of Móstoles, Madrid, said, of the dermatological manifestations caused as a reaction to these vaccines.”

The study was carried out during the first months of COVID-19 vaccination, Dr. Galván told this news organization. It was proposed as a continuation of a COVID skin study that was published in the British Journal of Dermatology. That study documented the first classification of skin lesions associated with COVID-19. Dr. Galván is the lead author of the latter study.

“The objectives of this study were to characterize and classify skin reactions after vaccination, identify their chronology, and analyze the associations with a series of antecedents: dermatological and allergic diseases, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, and skin reactions associated with COVID-19,” said Dr. Galván. The study was a team effort, she added.

“It was conducted between Feb. 15 and May 12, 2021, and information was gathered on 405 reactions that appeared during the 21 days after any dose of the COVID-19 vaccines approved at that time in Spain: the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and University of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines,” she added.

Dr. Galván explained that the study shows very clear patterns and investigators reached conclusions that match those of other groups that have investigated this topic. “Six reaction patterns were described according to their frequency. The first is the ‘COVID-19 arm,’ which consists of a local reaction at the injection site and occurs almost exclusively in women and in 70% of cases after inoculation with the Moderna serum. It is a manifestation that resolves well and does not always recur in subsequent doses. More than half are of delayed onset: biopsied patients show signs of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. In line with all the publications in this regard, it was found that this reaction is not a reason to skip or delay a dose.”

Herpes zoster reactivation

The second pattern is urticarial, which, according to the specialist, occurs with equal frequency after the administration of all vaccines and is well controlled with antihistamines. “This is a very nonspecific pattern, which does not prevent it from still being frequent. It was not associated with drug intake.

“The morbilliform pattern is more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. It affects the trunk and extremities, and up to a quarter of the cases required systemic corticosteroids. The papulovesicular and pityriasis rosea–like patterns are equally frequent in all vaccines. The latter is found in a younger age group. Finally, there is the purpuric pattern, more localized in the extremities and more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. On biopsy, this pattern showed small-vessel vasculitis.”

Less frequently, reactivations or de novo onset of different dermatologic diseases were found. “Varicella-zoster virus reactivations were observed with a frequency of 13.8%, being more common after the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine,” said Dr. Galván. “Other studies have corroborated this increase in herpes zoster, although it has been seen that the absolute number is low, so the benefits of the vaccine outweigh this eventual complication. At the same time and along the same lines, vaccination against herpes zoster is recommended for those over 50 years of age.”

Another fact revealed by the study is that these reactions were not significantly more severe in people with dermatologic diseases, those with previous infection, or those with skin manifestation associated with COVID-19.

Dr. Galván highlighted that, except for the COVID-19 arm, these patterns were among those associated with the disease, “which supports [the idea] that it does not demonstrate that the host’s immune reaction to the infection was playing a role.”

Women and young people

“As for pseudoperniosis, it is poorly represented in our series: 0.7% compared to 2% in the American registry. Although neither the SARS-CoV-2–pseudoperniosis association nor its pathophysiology is clear, the idea is that if this manifestation is related to the host’s immune response during infection, pseudoperniosis after vaccination could also be linked to the immune response to the vaccine,” said Dr. Galván.

Many of these reactions are more intense in women. “Before starting to use these vaccines, we already knew that messenger RNA vaccines (a powerful activator of innate immunity) induce frequent reactions, that adjuvants and excipients (polyethylene glycol and polysorbate) also generate them, and that other factors influence reactogenicity, among those of us of the same age and sex, reactions being more frequent in younger people and in women,” said Dr. Galván. “This may be one of the reasons why the COVID-19 arm is so much more prevalent in the female population and that 80% of all reactions that were collected were in women.”

In relation to the fact that manifestations differed, depending on the type of inoculated serum, Dr. Galván said, “Some reactions are just as common after any of the vaccines. However, others are not, as is the case with the COVID-19 arm for the Moderna vaccine or reactivations of the herpes virus, more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

“Undoubtedly, behind these differences are particularities in the immune reaction caused by each of the vaccines and their composition, including the excipients,” she said.

Regarding the fact that these reactions were the same throughout the vaccine regimen or that they varied in intensity, depending on the dose, Dr. Galván said, “In our study, as in those carried out by other groups, there were no significant differences in terms of frequency after the first and second doses. One thing to keep in mind is that, due to the temporary design of our study and the time at which it was conducted, it was not possible to collect reactions after second doses of AstraZeneca.

“Manifestations have generally been mild and well controlled. Many of them did not recur after the second dose, and the vast majority did not prevent completion of the vaccination scheme, but we must not lose sight of the fact that 20% of these manifestations were assessed by the dermatologist as serious or very serious,” Dr. Galván added.

Regarding the next steps planned for this line of research, Dr. Galván commented, “We are awaiting the evolution of the reported cases and the reactions that may arise, although for now, our group does not have any open studies. The most important thing now is to be alert and report the data observed in the pharmacovigilance systems, in open registries, and in scientific literature to generate evidence.”

Dr. Galván has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Skin manifestations of COVID-19 were among the topics presented in several sessions at the 49th Congress of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Specialists agreed that fewer skin changes associated with this virus have been seen with the latest variants of SARS-CoV-2. They highlighted the results of the most remarkable research on this topic that were presented in this forum.

In the study, which was carried out by Spanish dermatologists with the support of the AEDV, researchers analyzed skin reactions associated with the COVID-19 vaccine.

Study author Cristina Galván, MD, a dermatologist at the University Hospital of Móstoles, Madrid, said, of the dermatological manifestations caused as a reaction to these vaccines.”

The study was carried out during the first months of COVID-19 vaccination, Dr. Galván told this news organization. It was proposed as a continuation of a COVID skin study that was published in the British Journal of Dermatology. That study documented the first classification of skin lesions associated with COVID-19. Dr. Galván is the lead author of the latter study.

“The objectives of this study were to characterize and classify skin reactions after vaccination, identify their chronology, and analyze the associations with a series of antecedents: dermatological and allergic diseases, previous SARS-CoV-2 infection, and skin reactions associated with COVID-19,” said Dr. Galván. The study was a team effort, she added.

“It was conducted between Feb. 15 and May 12, 2021, and information was gathered on 405 reactions that appeared during the 21 days after any dose of the COVID-19 vaccines approved at that time in Spain: the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and University of Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines,” she added.

Dr. Galván explained that the study shows very clear patterns and investigators reached conclusions that match those of other groups that have investigated this topic. “Six reaction patterns were described according to their frequency. The first is the ‘COVID-19 arm,’ which consists of a local reaction at the injection site and occurs almost exclusively in women and in 70% of cases after inoculation with the Moderna serum. It is a manifestation that resolves well and does not always recur in subsequent doses. More than half are of delayed onset: biopsied patients show signs of a delayed hypersensitivity reaction. In line with all the publications in this regard, it was found that this reaction is not a reason to skip or delay a dose.”

Herpes zoster reactivation

The second pattern is urticarial, which, according to the specialist, occurs with equal frequency after the administration of all vaccines and is well controlled with antihistamines. “This is a very nonspecific pattern, which does not prevent it from still being frequent. It was not associated with drug intake.

“The morbilliform pattern is more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. It affects the trunk and extremities, and up to a quarter of the cases required systemic corticosteroids. The papulovesicular and pityriasis rosea–like patterns are equally frequent in all vaccines. The latter is found in a younger age group. Finally, there is the purpuric pattern, more localized in the extremities and more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines. On biopsy, this pattern showed small-vessel vasculitis.”

Less frequently, reactivations or de novo onset of different dermatologic diseases were found. “Varicella-zoster virus reactivations were observed with a frequency of 13.8%, being more common after the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine,” said Dr. Galván. “Other studies have corroborated this increase in herpes zoster, although it has been seen that the absolute number is low, so the benefits of the vaccine outweigh this eventual complication. At the same time and along the same lines, vaccination against herpes zoster is recommended for those over 50 years of age.”

Another fact revealed by the study is that these reactions were not significantly more severe in people with dermatologic diseases, those with previous infection, or those with skin manifestation associated with COVID-19.

Dr. Galván highlighted that, except for the COVID-19 arm, these patterns were among those associated with the disease, “which supports [the idea] that it does not demonstrate that the host’s immune reaction to the infection was playing a role.”

Women and young people

“As for pseudoperniosis, it is poorly represented in our series: 0.7% compared to 2% in the American registry. Although neither the SARS-CoV-2–pseudoperniosis association nor its pathophysiology is clear, the idea is that if this manifestation is related to the host’s immune response during infection, pseudoperniosis after vaccination could also be linked to the immune response to the vaccine,” said Dr. Galván.

Many of these reactions are more intense in women. “Before starting to use these vaccines, we already knew that messenger RNA vaccines (a powerful activator of innate immunity) induce frequent reactions, that adjuvants and excipients (polyethylene glycol and polysorbate) also generate them, and that other factors influence reactogenicity, among those of us of the same age and sex, reactions being more frequent in younger people and in women,” said Dr. Galván. “This may be one of the reasons why the COVID-19 arm is so much more prevalent in the female population and that 80% of all reactions that were collected were in women.”

In relation to the fact that manifestations differed, depending on the type of inoculated serum, Dr. Galván said, “Some reactions are just as common after any of the vaccines. However, others are not, as is the case with the COVID-19 arm for the Moderna vaccine or reactivations of the herpes virus, more frequent after the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

“Undoubtedly, behind these differences are particularities in the immune reaction caused by each of the vaccines and their composition, including the excipients,” she said.

Regarding the fact that these reactions were the same throughout the vaccine regimen or that they varied in intensity, depending on the dose, Dr. Galván said, “In our study, as in those carried out by other groups, there were no significant differences in terms of frequency after the first and second doses. One thing to keep in mind is that, due to the temporary design of our study and the time at which it was conducted, it was not possible to collect reactions after second doses of AstraZeneca.

“Manifestations have generally been mild and well controlled. Many of them did not recur after the second dose, and the vast majority did not prevent completion of the vaccination scheme, but we must not lose sight of the fact that 20% of these manifestations were assessed by the dermatologist as serious or very serious,” Dr. Galván added.

Regarding the next steps planned for this line of research, Dr. Galván commented, “We are awaiting the evolution of the reported cases and the reactions that may arise, although for now, our group does not have any open studies. The most important thing now is to be alert and report the data observed in the pharmacovigilance systems, in open registries, and in scientific literature to generate evidence.”

Dr. Galván has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Monkeypox mutating faster than expected

The monkeypox virus is evolving 6-12 times faster than would be expected, according to a new study.

The virus is thought to have a single origin, the genetic data suggests, and is a likely descendant of the strain involved in the 2017-2018 monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria. It’s not clear if these mutations have aided the transmissibility of the virus among people or have any other clinical implications, João Paulo Gomes, PhD, from Portugal’s National Institute of Health, Lisbon, said in an email.

Since the monkeypox outbreak began in May, nearly 7,000 cases of monkeypox have been reported across 52 countries and territories.

Orthopoxviruses – the genus to which monkeypox belongs – are large DNA viruses that usually only gain one or two mutations every year. (For comparison, SARS-CoV-2 gains around two mutations every month.) One would expect 5 to 10 mutations in the 2022 monkeypox virus, compared with the 2017 strain, Dr. Gomes said.

In the study, Dr. Gomes and colleagues analyzed 15 monkeypox DNA sequences made available by Portugal and the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md., between May 20 and May 27, 2022. The analysis revealed that this most recent strain differed by 50 single-nucleotide polymorphisms, compared with previous strains of the virus in 2017-2018.

“This is far beyond what we would expect, specifically for orthopoxvirus,” Andrew Lover, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Public Health & Health Sciences, told this news organization. He was not involved with the research. “That suggests [the virus] is trying to figure out the best way to deal with a new host species,” he added.

Rodents are thought to be the natural hosts of the monkeypox virus, he explained, and, in 2022, the infection transferred to humans. “Moving into a new species can ‘turbocharge’ mutations as the virus adapts to a new biological environment,” he explained, though it is not clear if the new mutations Dr. Gomes’s team detected help the 2022 virus spread more easily among people.

Researchers also found that the 2022 virus belonged in clade 3 of the virus, which is part of the less-lethal West-African clade. While the West-African clade has a fatality rate of less than 1%, the Central African clade has a fatality rate of over 10%.

The rapid changes in the viral genome could be driven by a family of proteins thought to play a role in antiviral immunity: apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3 (APOBEC3). These enzymes can make changes to a viral genome, Dr. Gomes explained, “but sometimes the system is not ‘well regulated,’ and the changes in the genome are not detrimental to the virus.” These APOBEC3-driven mutations have a signature pattern, he said, which was also detected in most of the 50 new mutations Dr. Gomes’s team identified.

However, it is not known if these mutations have clinical implications, Dr. Lover said.

The 2022 monkeypox virus does appear to behave differently than previous strains of the virus, he noted. In the current outbreak, sexual transmission appears to be very common, which is not the case for previous outbreaks, he said. Also, while monkeypox traditionally presents with a rash that can spread to all parts of the body, there have been several instances of patients presenting with just a few “very innocuous lesions,” he added.

Dr. Gomes hopes that specialized lab groups will now be able to tease out whether there is a connection between these identified mutations and changes in the behavior of the virus, including transmissibility.

While none of the findings in this analysis raises any serious concerns, the study “suggests there [are] definitely gaps in our knowledge about monkeypox,” Dr. Lover said. As for the global health response, he said, “We probably should err on the side of caution. ... There are clearly things that we absolutely don’t understand here, in terms of how quickly mutations are popping up.”

Dr. Gomes and Dr. Lover report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The monkeypox virus is evolving 6-12 times faster than would be expected, according to a new study.

The virus is thought to have a single origin, the genetic data suggests, and is a likely descendant of the strain involved in the 2017-2018 monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria. It’s not clear if these mutations have aided the transmissibility of the virus among people or have any other clinical implications, João Paulo Gomes, PhD, from Portugal’s National Institute of Health, Lisbon, said in an email.

Since the monkeypox outbreak began in May, nearly 7,000 cases of monkeypox have been reported across 52 countries and territories.

Orthopoxviruses – the genus to which monkeypox belongs – are large DNA viruses that usually only gain one or two mutations every year. (For comparison, SARS-CoV-2 gains around two mutations every month.) One would expect 5 to 10 mutations in the 2022 monkeypox virus, compared with the 2017 strain, Dr. Gomes said.

In the study, Dr. Gomes and colleagues analyzed 15 monkeypox DNA sequences made available by Portugal and the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md., between May 20 and May 27, 2022. The analysis revealed that this most recent strain differed by 50 single-nucleotide polymorphisms, compared with previous strains of the virus in 2017-2018.

“This is far beyond what we would expect, specifically for orthopoxvirus,” Andrew Lover, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Public Health & Health Sciences, told this news organization. He was not involved with the research. “That suggests [the virus] is trying to figure out the best way to deal with a new host species,” he added.

Rodents are thought to be the natural hosts of the monkeypox virus, he explained, and, in 2022, the infection transferred to humans. “Moving into a new species can ‘turbocharge’ mutations as the virus adapts to a new biological environment,” he explained, though it is not clear if the new mutations Dr. Gomes’s team detected help the 2022 virus spread more easily among people.

Researchers also found that the 2022 virus belonged in clade 3 of the virus, which is part of the less-lethal West-African clade. While the West-African clade has a fatality rate of less than 1%, the Central African clade has a fatality rate of over 10%.

The rapid changes in the viral genome could be driven by a family of proteins thought to play a role in antiviral immunity: apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3 (APOBEC3). These enzymes can make changes to a viral genome, Dr. Gomes explained, “but sometimes the system is not ‘well regulated,’ and the changes in the genome are not detrimental to the virus.” These APOBEC3-driven mutations have a signature pattern, he said, which was also detected in most of the 50 new mutations Dr. Gomes’s team identified.

However, it is not known if these mutations have clinical implications, Dr. Lover said.

The 2022 monkeypox virus does appear to behave differently than previous strains of the virus, he noted. In the current outbreak, sexual transmission appears to be very common, which is not the case for previous outbreaks, he said. Also, while monkeypox traditionally presents with a rash that can spread to all parts of the body, there have been several instances of patients presenting with just a few “very innocuous lesions,” he added.

Dr. Gomes hopes that specialized lab groups will now be able to tease out whether there is a connection between these identified mutations and changes in the behavior of the virus, including transmissibility.

While none of the findings in this analysis raises any serious concerns, the study “suggests there [are] definitely gaps in our knowledge about monkeypox,” Dr. Lover said. As for the global health response, he said, “We probably should err on the side of caution. ... There are clearly things that we absolutely don’t understand here, in terms of how quickly mutations are popping up.”

Dr. Gomes and Dr. Lover report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The monkeypox virus is evolving 6-12 times faster than would be expected, according to a new study.

The virus is thought to have a single origin, the genetic data suggests, and is a likely descendant of the strain involved in the 2017-2018 monkeypox outbreak in Nigeria. It’s not clear if these mutations have aided the transmissibility of the virus among people or have any other clinical implications, João Paulo Gomes, PhD, from Portugal’s National Institute of Health, Lisbon, said in an email.

Since the monkeypox outbreak began in May, nearly 7,000 cases of monkeypox have been reported across 52 countries and territories.

Orthopoxviruses – the genus to which monkeypox belongs – are large DNA viruses that usually only gain one or two mutations every year. (For comparison, SARS-CoV-2 gains around two mutations every month.) One would expect 5 to 10 mutations in the 2022 monkeypox virus, compared with the 2017 strain, Dr. Gomes said.

In the study, Dr. Gomes and colleagues analyzed 15 monkeypox DNA sequences made available by Portugal and the National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, Md., between May 20 and May 27, 2022. The analysis revealed that this most recent strain differed by 50 single-nucleotide polymorphisms, compared with previous strains of the virus in 2017-2018.

“This is far beyond what we would expect, specifically for orthopoxvirus,” Andrew Lover, PhD, an epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst School of Public Health & Health Sciences, told this news organization. He was not involved with the research. “That suggests [the virus] is trying to figure out the best way to deal with a new host species,” he added.

Rodents are thought to be the natural hosts of the monkeypox virus, he explained, and, in 2022, the infection transferred to humans. “Moving into a new species can ‘turbocharge’ mutations as the virus adapts to a new biological environment,” he explained, though it is not clear if the new mutations Dr. Gomes’s team detected help the 2022 virus spread more easily among people.

Researchers also found that the 2022 virus belonged in clade 3 of the virus, which is part of the less-lethal West-African clade. While the West-African clade has a fatality rate of less than 1%, the Central African clade has a fatality rate of over 10%.

The rapid changes in the viral genome could be driven by a family of proteins thought to play a role in antiviral immunity: apolipoprotein B mRNA editing enzyme, catalytic polypeptide-like 3 (APOBEC3). These enzymes can make changes to a viral genome, Dr. Gomes explained, “but sometimes the system is not ‘well regulated,’ and the changes in the genome are not detrimental to the virus.” These APOBEC3-driven mutations have a signature pattern, he said, which was also detected in most of the 50 new mutations Dr. Gomes’s team identified.

However, it is not known if these mutations have clinical implications, Dr. Lover said.

The 2022 monkeypox virus does appear to behave differently than previous strains of the virus, he noted. In the current outbreak, sexual transmission appears to be very common, which is not the case for previous outbreaks, he said. Also, while monkeypox traditionally presents with a rash that can spread to all parts of the body, there have been several instances of patients presenting with just a few “very innocuous lesions,” he added.

Dr. Gomes hopes that specialized lab groups will now be able to tease out whether there is a connection between these identified mutations and changes in the behavior of the virus, including transmissibility.

While none of the findings in this analysis raises any serious concerns, the study “suggests there [are] definitely gaps in our knowledge about monkeypox,” Dr. Lover said. As for the global health response, he said, “We probably should err on the side of caution. ... There are clearly things that we absolutely don’t understand here, in terms of how quickly mutations are popping up.”

Dr. Gomes and Dr. Lover report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis Induced by the Second-Generation Antipsychotic Cariprazine

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

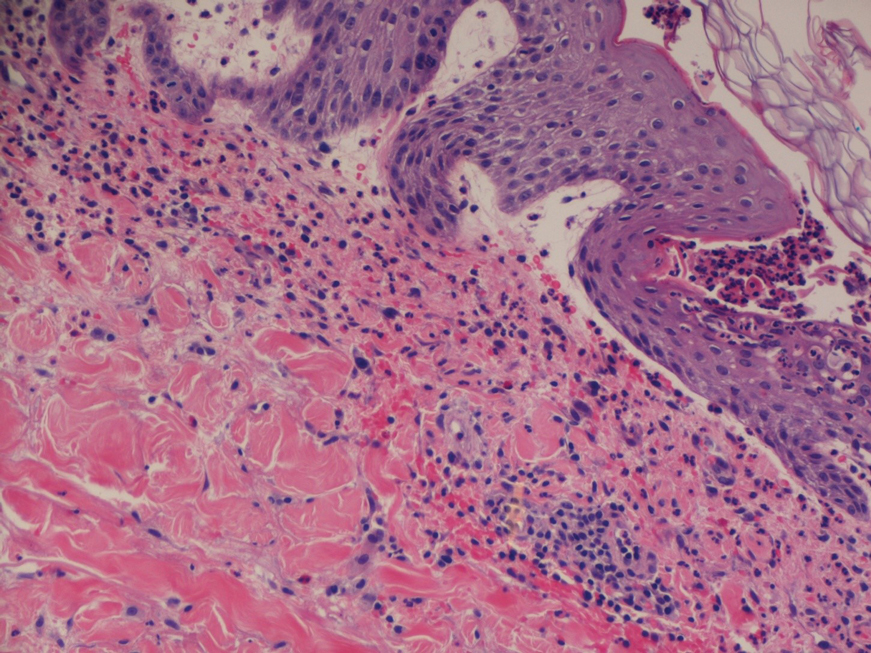

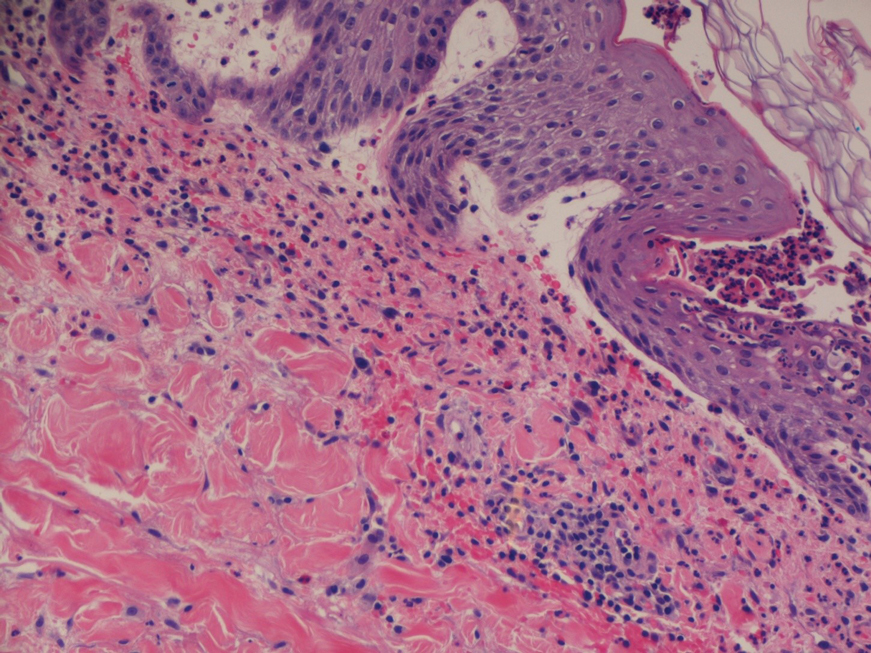

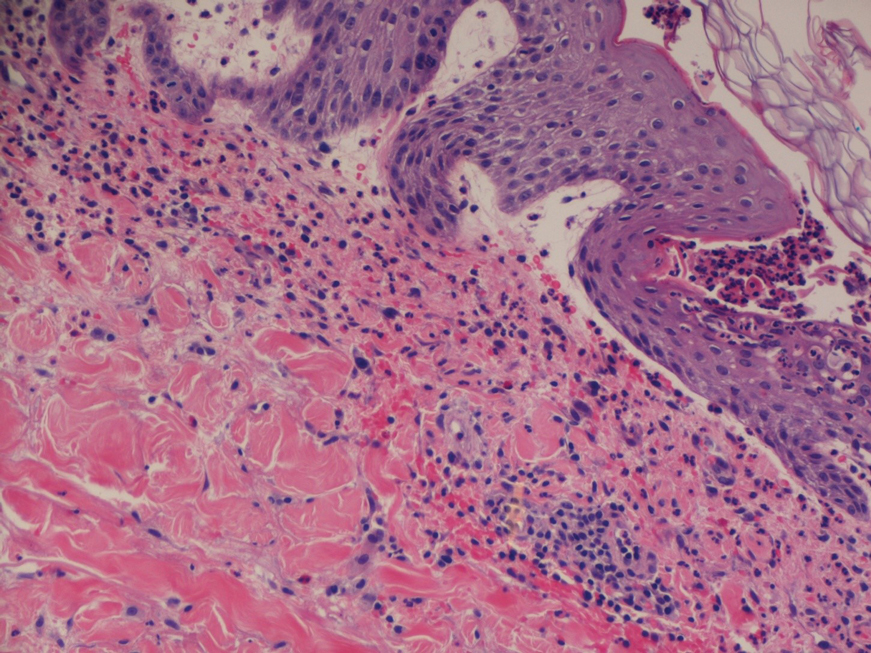

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old woman presented to an outpatient clinic with severe pruritus and burning of the skin as well as subjective fevers and chills. She had been discharged from a psychiatric hospital for attempted suicide 1 day prior. There were no recent changes in the medication regimen, which consisted of linaclotide, fluoxetine, lorazepam, and gabapentin. While admitted, the patient was started on the atypical antipsychotic cariprazine. Within 24 hours of the first dose, she developed severe facial erythema that progressed to diffuse erythema over more than 60% of the body surface area. The attending psychiatrist promptly discontinued cariprazine. During the next 24 hours, there were no reports of fever, leukocytosis, or signs of systemic organ involvement. Given the patient’s mental and medical stability, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with the outpatient dermatology clinic.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed innumerable 1- to 4-mm pustules coalescing to lakes of pus on an erythematous base over more than 60% of the body surface area (Figure 1). The mucous membranes were clear of lesions, the Nikolsky sign was negative, and the patient’s temperature was 99.6 °F in the office. Complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panel results were within reference range.

A 4-mm abdominal punch biopsy showed subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, papillary dermal edema, and superficial dermal lymphohistiocytic inflammation with numerous neutrophils, eosinophils, and extravasated red blood cells, consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)(Figure 2). The patient was started on wet wraps with triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

Two days later, physical examination revealed the erythema noted on initial examination had notably decreased, and the patient no longer reported burning or pruritus. One week after initial presentation to the clinic, the patient’s rash had resolved, and only a few small areas of desquamation remained.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is a severe cutaneous adverse reaction characterized by the development of numerous nonfollicular sterile pustules on an edematous and erythematous base. In almost 90% of reported cases, the cause is related to use of antibiotics, antifungals, antimalarials, or diltiazem (a calcium channel blocker). This rare cutaneous reaction occurs in 1 to 5 patients per million per year1; it carries a 1% to 2% mortality rate with proper supportive treatment.

The clinical symptoms of AGEP typically present 24 to 48 hours after drug initiation with the rapid development of dozens to thousands of 1- to 4-mm pustules, typically localized to the flexor surfaces and face. In the setting of AGEP, acute onset of fever and leukocytosis typically occur at the time of the cutaneous eruption. These features were absent in this patient. The eruption usually starts on the face and then migrates to the trunk and extremities, sparing the palms and soles. Systemic involvement most commonly presents as hepatic, renal, or pulmonary insufficiency, which has been seen in 20% of cases.2

The immunologic response associated with the reaction has been studied in vitro. Drug-specific CD8 T cells use perforin/granzyme B and Fas ligand mechanisms to induce apoptosis of the keratinocytes within the epidermis, leading to vesicle formation.3 During the very first stages of formation, vesicles mainly comprise CD8 T cells and keratinocytes. These cells then begin producing CXC-18, a potent neutrophil chemokine, leading to extensive chemotaxis of neutrophils into vesicles, which then rapidly transform to pustules.3 This rapid transformation leads to the lakes of pustules, a description often associated with AGEP.

Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuing use of the causative agent. Topical corticosteroids can be used during the pustular phase for symptom management. There is no evidence that systemic steroids reduce the duration of the disease.2 Other supportive measures such as application of wet wraps can be used to provide comfort.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions commonly are associated with psychiatric pharmacotherapy, but first-and second-generation antipsychotics rarely are associated with these types of reactions. In this patient, the causative agent of the AGEP was cariprazine, an atypical antipsychotic that had no reported association with AGEP or cutaneous adverse drug reactions prior to this presentation.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

- Fernando SL. Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2012;53:87-92.

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1214.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:843-848.

Practice Points

- The second-generation antipsychotic cariprazine has been shown to be a potential causative agent in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP).

- Treatment of AGEP is mainly supportive and consists of discontinuation of the causative agent as well as symptom control using cold compresses and topical corticosteroids.

Nevus Lipomatosis Deemed Suspicious by Airport Security

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented at the dermatology clinic with a growing lesion on the left medial thigh.

Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, pedunculated, fatty nodule on the left medial thigh that was clinically consistent with nevus lipomatosis (NL)(Figure). Although benign, trouble traveling through airport security prompted the patient to request shave removal, which subsequently was performed. Histology showed a large pedunculated nodule with prominent adipose tissue, consistent with NL. At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported getting through airport security multiple times without incident.

Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion most commonly found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults. The lesion usually is asymptomatic but can become irritated by rubbing or catching on clothing. Our patient had symptomatic NL that caused delays getting through airport security; he experienced full resolution after simple shave removal. In rare instances, both benign and malignant skin conditions have been seen on airport scanning devices since the introduction of increased security measures following September 11, 2001. In 2016, Heymann1 reported a man with a 1.5-cm epidermal inclusion cyst detected by airport security scanners, prompting the traveler to request and carry a medically explanatory letter used to get through security. In 2015 Mayer and Adams2 described a case of nodular melanoma that was detected 20 times over a period of 2 months by airport scanners, and in 2016, Caine et al3 reported a case of desmoplastic melanoma that was detected by airport security, but after its removal was not identified by security for the next 40 flights. Noncutaneous pathology also can be detected by airport scanners. In 2013, Naraynsingh et al4 reported a man with a large left reducible inguinal hernia who was stopped by airport security and subjected to an invasive physical examination of the area. These instances demonstrate the breadth of conditions that can be cumbersome when individuals are traveling by airplane in our current security climate.

Our patient had to go through the trouble of having the benign NL lesion removed to avoid the hassle of repeatedly being stopped by airport security. The patient had the lesion removed and is doing well, but the procedure could have been avoided if systems existed to help patients with dermatologic and medical conditions at airport security. Our patient likely will never be stopped again for the suspicious lump on the left inner thigh, but many others will be stopped for similar reasons.

- Heymann WR. A cyst misinterpreted on airport scan as security threat. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3329

- Mayer JE, Adams BB. Nodular melanoma serendipitously detected by airport full body scanners. Dermatology. 2015;230:16-17. doi:10.1159/000368045

- Caine P, Javed MU, Karoo ROS. A desmoplastic melanoma detected by an airport security scanner. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.022

- Naraynsingh V, Cawich SO, Maharaj R, et al. Inguinal hernia and airport scanners: an emerging indication for repair? 2013;2013:952835. Case Rep Med. doi:10.1155/2013/952835

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented at the dermatology clinic with a growing lesion on the left medial thigh.

Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, pedunculated, fatty nodule on the left medial thigh that was clinically consistent with nevus lipomatosis (NL)(Figure). Although benign, trouble traveling through airport security prompted the patient to request shave removal, which subsequently was performed. Histology showed a large pedunculated nodule with prominent adipose tissue, consistent with NL. At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported getting through airport security multiple times without incident.

Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion most commonly found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults. The lesion usually is asymptomatic but can become irritated by rubbing or catching on clothing. Our patient had symptomatic NL that caused delays getting through airport security; he experienced full resolution after simple shave removal. In rare instances, both benign and malignant skin conditions have been seen on airport scanning devices since the introduction of increased security measures following September 11, 2001. In 2016, Heymann1 reported a man with a 1.5-cm epidermal inclusion cyst detected by airport security scanners, prompting the traveler to request and carry a medically explanatory letter used to get through security. In 2015 Mayer and Adams2 described a case of nodular melanoma that was detected 20 times over a period of 2 months by airport scanners, and in 2016, Caine et al3 reported a case of desmoplastic melanoma that was detected by airport security, but after its removal was not identified by security for the next 40 flights. Noncutaneous pathology also can be detected by airport scanners. In 2013, Naraynsingh et al4 reported a man with a large left reducible inguinal hernia who was stopped by airport security and subjected to an invasive physical examination of the area. These instances demonstrate the breadth of conditions that can be cumbersome when individuals are traveling by airplane in our current security climate.

Our patient had to go through the trouble of having the benign NL lesion removed to avoid the hassle of repeatedly being stopped by airport security. The patient had the lesion removed and is doing well, but the procedure could have been avoided if systems existed to help patients with dermatologic and medical conditions at airport security. Our patient likely will never be stopped again for the suspicious lump on the left inner thigh, but many others will be stopped for similar reasons.

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented at the dermatology clinic with a growing lesion on the left medial thigh.

Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, pedunculated, fatty nodule on the left medial thigh that was clinically consistent with nevus lipomatosis (NL)(Figure). Although benign, trouble traveling through airport security prompted the patient to request shave removal, which subsequently was performed. Histology showed a large pedunculated nodule with prominent adipose tissue, consistent with NL. At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported getting through airport security multiple times without incident.

Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion most commonly found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults. The lesion usually is asymptomatic but can become irritated by rubbing or catching on clothing. Our patient had symptomatic NL that caused delays getting through airport security; he experienced full resolution after simple shave removal. In rare instances, both benign and malignant skin conditions have been seen on airport scanning devices since the introduction of increased security measures following September 11, 2001. In 2016, Heymann1 reported a man with a 1.5-cm epidermal inclusion cyst detected by airport security scanners, prompting the traveler to request and carry a medically explanatory letter used to get through security. In 2015 Mayer and Adams2 described a case of nodular melanoma that was detected 20 times over a period of 2 months by airport scanners, and in 2016, Caine et al3 reported a case of desmoplastic melanoma that was detected by airport security, but after its removal was not identified by security for the next 40 flights. Noncutaneous pathology also can be detected by airport scanners. In 2013, Naraynsingh et al4 reported a man with a large left reducible inguinal hernia who was stopped by airport security and subjected to an invasive physical examination of the area. These instances demonstrate the breadth of conditions that can be cumbersome when individuals are traveling by airplane in our current security climate.

Our patient had to go through the trouble of having the benign NL lesion removed to avoid the hassle of repeatedly being stopped by airport security. The patient had the lesion removed and is doing well, but the procedure could have been avoided if systems existed to help patients with dermatologic and medical conditions at airport security. Our patient likely will never be stopped again for the suspicious lump on the left inner thigh, but many others will be stopped for similar reasons.

- Heymann WR. A cyst misinterpreted on airport scan as security threat. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3329

- Mayer JE, Adams BB. Nodular melanoma serendipitously detected by airport full body scanners. Dermatology. 2015;230:16-17. doi:10.1159/000368045

- Caine P, Javed MU, Karoo ROS. A desmoplastic melanoma detected by an airport security scanner. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.022

- Naraynsingh V, Cawich SO, Maharaj R, et al. Inguinal hernia and airport scanners: an emerging indication for repair? 2013;2013:952835. Case Rep Med. doi:10.1155/2013/952835

- Heymann WR. A cyst misinterpreted on airport scan as security threat. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3329

- Mayer JE, Adams BB. Nodular melanoma serendipitously detected by airport full body scanners. Dermatology. 2015;230:16-17. doi:10.1159/000368045

- Caine P, Javed MU, Karoo ROS. A desmoplastic melanoma detected by an airport security scanner. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.022

- Naraynsingh V, Cawich SO, Maharaj R, et al. Inguinal hernia and airport scanners: an emerging indication for repair? 2013;2013:952835. Case Rep Med. doi:10.1155/2013/952835

Practice Points

- Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion that most commonly is found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults.

- Both benign and malignant skin conditions have been detected on airport scanning devices.

- At times, patients must go through the hassle of having the benign lesions removed to avoid repeated problems at airport security.

Is a single dose of HPV vaccine enough?

In an April press release, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) of the World Health Organization (WHO) reported the findings of their review concerning the efficacy of various dose schedules for human papillomavirus (HPV). “A single-dose HPV vaccine delivers solid protection against HPV, the virus that causes cervical cancer, that is comparable to 2-dose schedules,” according to SAGE.

This statement comes on the heels of an article published in the November 2021 issue of Lancet Oncology about a study in India. It found that a single dose of the vaccine provides protection against persistent infection from HPV 16 and 18 similar to that provided by two or three doses.

Will this new information lead French authorities to change their recommendations? What do French specialists think? At the 45th Congress of the French Society for Colposcopy and Cervical and Vaginal Diseases (SFCPCV), Geoffroy Canlorbe, MD, PhD, of the department of gynecologic and breast surgery and oncology, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, shared his thoughts.

With respect to the Indian study, Dr. Canlorbe pointed out that while its findings would need “to be confirmed by other studies,” they were, nonetheless,

India and France

During the congress press conference, he went on to say that, at this stage, the findings “cannot be extrapolated” to France. This is because the country’s situation is different. HPV vaccination coverage is low; estimates put it at 23.7%, placing the country 28th out of 31 in Europe.

“This poor coverage has nothing to do with health care–related logistical or organizational issues; instead, it has to do with people’s mistrust when it comes to vaccination. Here, people who get the first dose get the subsequent ones,” said Dr. Canlorbe. “The very fact of getting two to three doses allows the person’s body to increase the production of antibodies and get a longer-lasting response to the vaccine.”

In addition, he drew attention to several limitations of the Indian study. Initially, the team had planned to enroll 20,000 participants. In the end, there were around 17,000, and these were allocated to three cohorts: single-dose, two-dose, and three-dose. Furthermore, the primary objective, which had initially been focused on precancerous and cancerous lesions, was revised. The new aim was to compare vaccine efficacy of single dose to that of three and two doses in protecting against persistent HPV 16 and 18 infection at 10 years postvaccination. In about 90% of cases, the HPV infection went away spontaneously in 2 years without inducing lesions. Finally, the participants were women in India; therefore, the results cannot necessarily be generalized to the French population.

“This information has to be confirmed. However, as far as I know, there are no new studies going on at the moment. The Indian study, on the other hand, is still in progress,” said Dr. Canlorbe.

“In France, I think that for the time being we should stick to the studies that are currently available, which have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of two or three doses,” he concluded. In support of this approach, he cited a study on the effects of the national HPV vaccination program in England; there, the vaccination coverage is 80%.

This program was associated with a 95% risk reduction for precancerous lesions and an 87% reduction in the number of cancers, confirming the good results already achieved by Sweden and Australia.

In his comments on the WHO’s stance (which differs from that of the French experts), Jean-Luc Mergui, MD, gynecologist in the department of colposcopy and hysteroscopy at Pitié-Salpêtrière, and former president of the SFCPCV, offered an eloquent comparison: “The WHO also recommends 6 months of breastfeeding as a method of contraception, but this isn’t what’s recommended in France, for the risk of getting pregnant nevertheless remains.”

Indian study highlights

Partha Basu, MD, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in Lyon, France, and colleagues compared vaccine efficacy of a single dose of Gardasil (HPV 9-valent vaccine, recombinant) to that of two and three doses in protecting against persistent HPV 16 and HPV 18 infection at 10 years postvaccination.

According to the protocol, the plan was to recruit 20,000 unmarried girls, aged 10-18 years, from across India. Recruitment was initiated in September 2009. However, in response to seven unexplained deaths reported in another ongoing HPV vaccination demonstration program in the country, the Indian government issued a notification in April 2010 to stop further recruitment and HPV vaccination in all clinical trials. At this point, Dr. Basu and his team had recruited 17,729 eligible girls.

After suspension of recruitment and vaccination, their randomized trial was converted to a longitudinal, prospective, cohort study by default.

Vaccinated participants were followed up over a median duration of 9 years. In all, 4,348 participants had three doses, 4,980 had two doses (at 0 and 6 months), and 4,949 had a single dose. Cervical specimens were collected from participants 18 months after marriage or 6 months after first childbirth, whichever was earlier, to assess incident and persistent HPV infections. Participants were invited to an annual cervical cancer screening once they reached age 25 years and were married.

A single dose of HPV vaccine provides similar protection against persistent infection from HPV 16 and HPV 18, the genotypes responsible for nearly 70% of cervical cancers, compared with that provided by two or three doses. Vaccine efficacy against persistent HPV 16 and 18 infection among participants evaluable for the endpoint was 95.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85.0-99.9) in the single-dose default cohort (2,135 women assessed), 93.1% (95% CI, 77.3-99.8) in the two-dose cohort (1,452 women assessed), and 93.3% (95% CI, 77.5-99.7) in three-dose recipients (1,460 women assessed).

Dr. Canlorbe reported no relevant financial relationships regarding the content of this article.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. An English version appeared on Medscape.com.

In an April press release, the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE) of the World Health Organization (WHO) reported the findings of their review concerning the efficacy of various dose schedules for human papillomavirus (HPV). “A single-dose HPV vaccine delivers solid protection against HPV, the virus that causes cervical cancer, that is comparable to 2-dose schedules,” according to SAGE.

This statement comes on the heels of an article published in the November 2021 issue of Lancet Oncology about a study in India. It found that a single dose of the vaccine provides protection against persistent infection from HPV 16 and 18 similar to that provided by two or three doses.

Will this new information lead French authorities to change their recommendations? What do French specialists think? At the 45th Congress of the French Society for Colposcopy and Cervical and Vaginal Diseases (SFCPCV), Geoffroy Canlorbe, MD, PhD, of the department of gynecologic and breast surgery and oncology, Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, Paris, shared his thoughts.

With respect to the Indian study, Dr. Canlorbe pointed out that while its findings would need “to be confirmed by other studies,” they were, nonetheless,

India and France

During the congress press conference, he went on to say that, at this stage, the findings “cannot be extrapolated” to France. This is because the country’s situation is different. HPV vaccination coverage is low; estimates put it at 23.7%, placing the country 28th out of 31 in Europe.

“This poor coverage has nothing to do with health care–related logistical or organizational issues; instead, it has to do with people’s mistrust when it comes to vaccination. Here, people who get the first dose get the subsequent ones,” said Dr. Canlorbe. “The very fact of getting two to three doses allows the person’s body to increase the production of antibodies and get a longer-lasting response to the vaccine.”

In addition, he drew attention to several limitations of the Indian study. Initially, the team had planned to enroll 20,000 participants. In the end, there were around 17,000, and these were allocated to three cohorts: single-dose, two-dose, and three-dose. Furthermore, the primary objective, which had initially been focused on precancerous and cancerous lesions, was revised. The new aim was to compare vaccine efficacy of single dose to that of three and two doses in protecting against persistent HPV 16 and 18 infection at 10 years postvaccination. In about 90% of cases, the HPV infection went away spontaneously in 2 years without inducing lesions. Finally, the participants were women in India; therefore, the results cannot necessarily be generalized to the French population.

“This information has to be confirmed. However, as far as I know, there are no new studies going on at the moment. The Indian study, on the other hand, is still in progress,” said Dr. Canlorbe.

“In France, I think that for the time being we should stick to the studies that are currently available, which have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of two or three doses,” he concluded. In support of this approach, he cited a study on the effects of the national HPV vaccination program in England; there, the vaccination coverage is 80%.

This program was associated with a 95% risk reduction for precancerous lesions and an 87% reduction in the number of cancers, confirming the good results already achieved by Sweden and Australia.

In his comments on the WHO’s stance (which differs from that of the French experts), Jean-Luc Mergui, MD, gynecologist in the department of colposcopy and hysteroscopy at Pitié-Salpêtrière, and former president of the SFCPCV, offered an eloquent comparison: “The WHO also recommends 6 months of breastfeeding as a method of contraception, but this isn’t what’s recommended in France, for the risk of getting pregnant nevertheless remains.”

Indian study highlights

Partha Basu, MD, PhD, of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in Lyon, France, and colleagues compared vaccine efficacy of a single dose of Gardasil (HPV 9-valent vaccine, recombinant) to that of two and three doses in protecting against persistent HPV 16 and HPV 18 infection at 10 years postvaccination.

According to the protocol, the plan was to recruit 20,000 unmarried girls, aged 10-18 years, from across India. Recruitment was initiated in September 2009. However, in response to seven unexplained deaths reported in another ongoing HPV vaccination demonstration program in the country, the Indian government issued a notification in April 2010 to stop further recruitment and HPV vaccination in all clinical trials. At this point, Dr. Basu and his team had recruited 17,729 eligible girls.

After suspension of recruitment and vaccination, their randomized trial was converted to a longitudinal, prospective, cohort study by default.

Vaccinated participants were followed up over a median duration of 9 years. In all, 4,348 participants had three doses, 4,980 had two doses (at 0 and 6 months), and 4,949 had a single dose. Cervical specimens were collected from participants 18 months after marriage or 6 months after first childbirth, whichever was earlier, to assess incident and persistent HPV infections. Participants were invited to an annual cervical cancer screening once they reached age 25 years and were married.

A single dose of HPV vaccine provides similar protection against persistent infection from HPV 16 and HPV 18, the genotypes responsible for nearly 70% of cervical cancers, compared with that provided by two or three doses. Vaccine efficacy against persistent HPV 16 and 18 infection among participants evaluable for the endpoint was 95.4% (95% confidence interval [CI], 85.0-99.9) in the single-dose default cohort (2,135 women assessed), 93.1% (95% CI, 77.3-99.8) in the two-dose cohort (1,452 women assessed), and 93.3% (95% CI, 77.5-99.7) in three-dose recipients (1,460 women assessed).

Dr. Canlorbe reported no relevant financial relationships regarding the content of this article.

This article was translated from the Medscape French edition. An English version appeared on Medscape.com.