User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Melasma Risk Factors: A Matched Cohort Study Using Data From the All of Us Research Program

To the Editor:

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is characterized by symmetric hyperpigmented patches affecting sun-exposed areas. Women commonly develop this condition during pregnancy, suggesting a connection between melasma and increased female sex hormone levels.1 Other hypothesized risk factors include sun exposure, genetic susceptibility, estrogen and/or progesterone therapy, and thyroid abnormalities but have not been corroborated.2 Treatment options are limited because the pathogenesis is poorly understood; thus, we aimed to analyze melasma risk factors using a national database with a nested case-control approach.

We conducted a matched case-control study using the Registered Tier dataset (version 7) from the National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program (https://allofus.nih.gov/), which is available to authorized users through the program’s Researcher Workbench and includes more than 413,000 total participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, through July 1, 2022. Cases included patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of melasma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code L81.1 [Chloasma]; concept ID 4264234 [Chloasma]; and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] code 36209000 [Chloasma]), and controls without a diagnosis of melasma were matched in a 1:10 ratio based on age, sex, and self-reported race. Concept IDs and SNOMED codes were used to identify individuals in each cohort with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (concept IDs 433753, 435243, 4218106; SNOMED codes 15167005, 66590003, 7200002), depression (concept ID 440383; SNOMED code 35489007), hypothyroidism (concept ID 140673; SNOMED code 40930008), hyperthyroidism (concept ID 4142479; SNOMED code 34486009), anxiety (concept IDs 441542, 442077, 434613; SNOMED codes 48694002, 197480006, 21897009), tobacco dependence (concept IDs 37109023, 437264, 4099811; SNOMED codes 16077091000119107, 89765005, 191887008), or obesity (concept IDs 433736 and 434005; SNOMED codes 414916001 and 238136002), or with a history of radiation therapy (concept IDs 4085340, 4311117, 4061844, 4029715; SNOMED codes 24803000, 85983004, 200861004, 108290001) or hormonal medications containing estrogen and/or progesterone, including oral medications and implants (concept IDs 21602445, 40254009, 21602514, 21603814, 19049228, 21602529, 1549080, 1551673, 1549254, 21602472, 21602446, 21602450, 21602515, 21602566, 21602473, 21602567, 21602488, 21602585, 1596779, 1586808, 21602524). In our case cohort, diagnoses and exposures to treatments were only considered for analysis if they occurred prior to melasma diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and P values between melasma and each comorbidity or exposure to the treatments specified. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

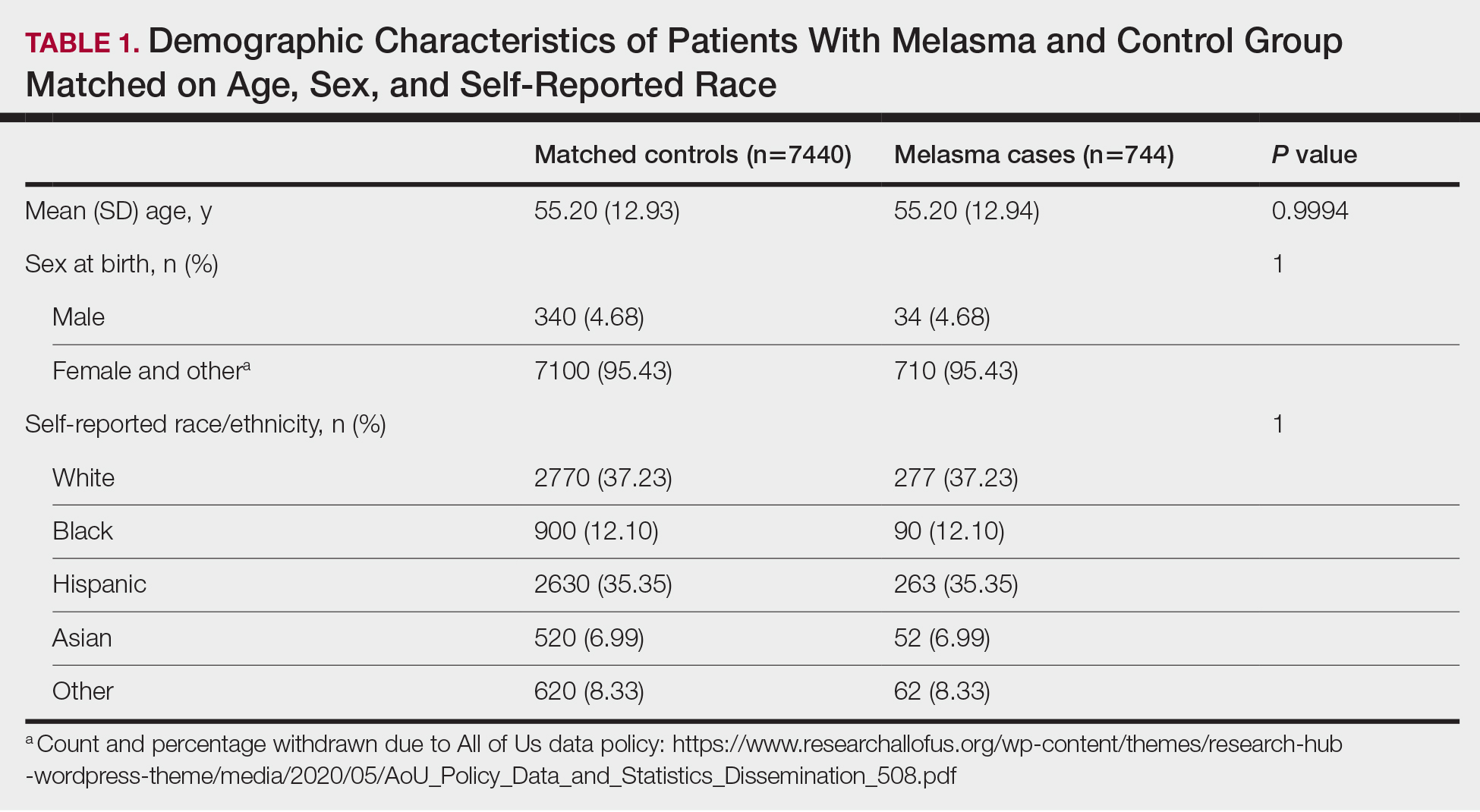

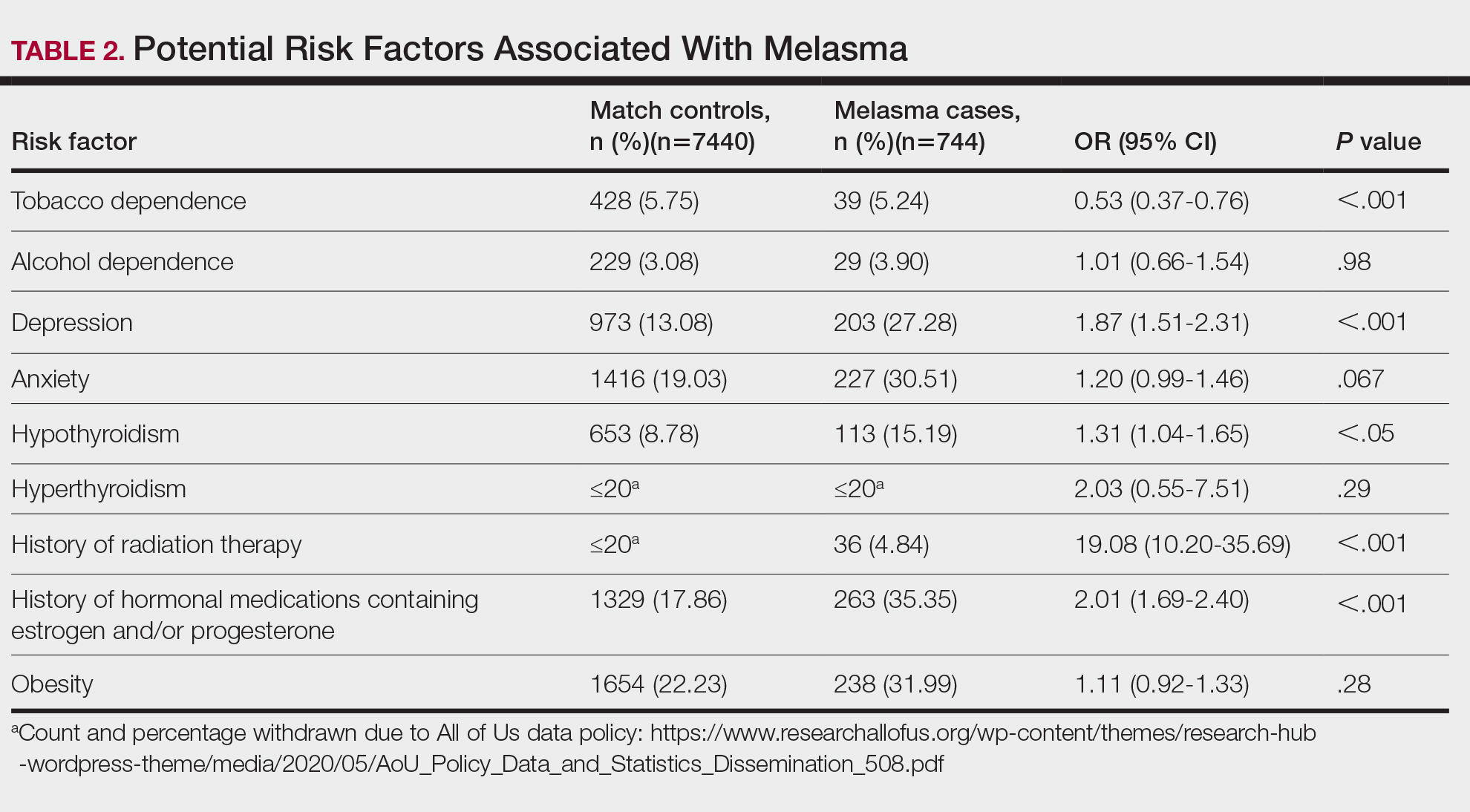

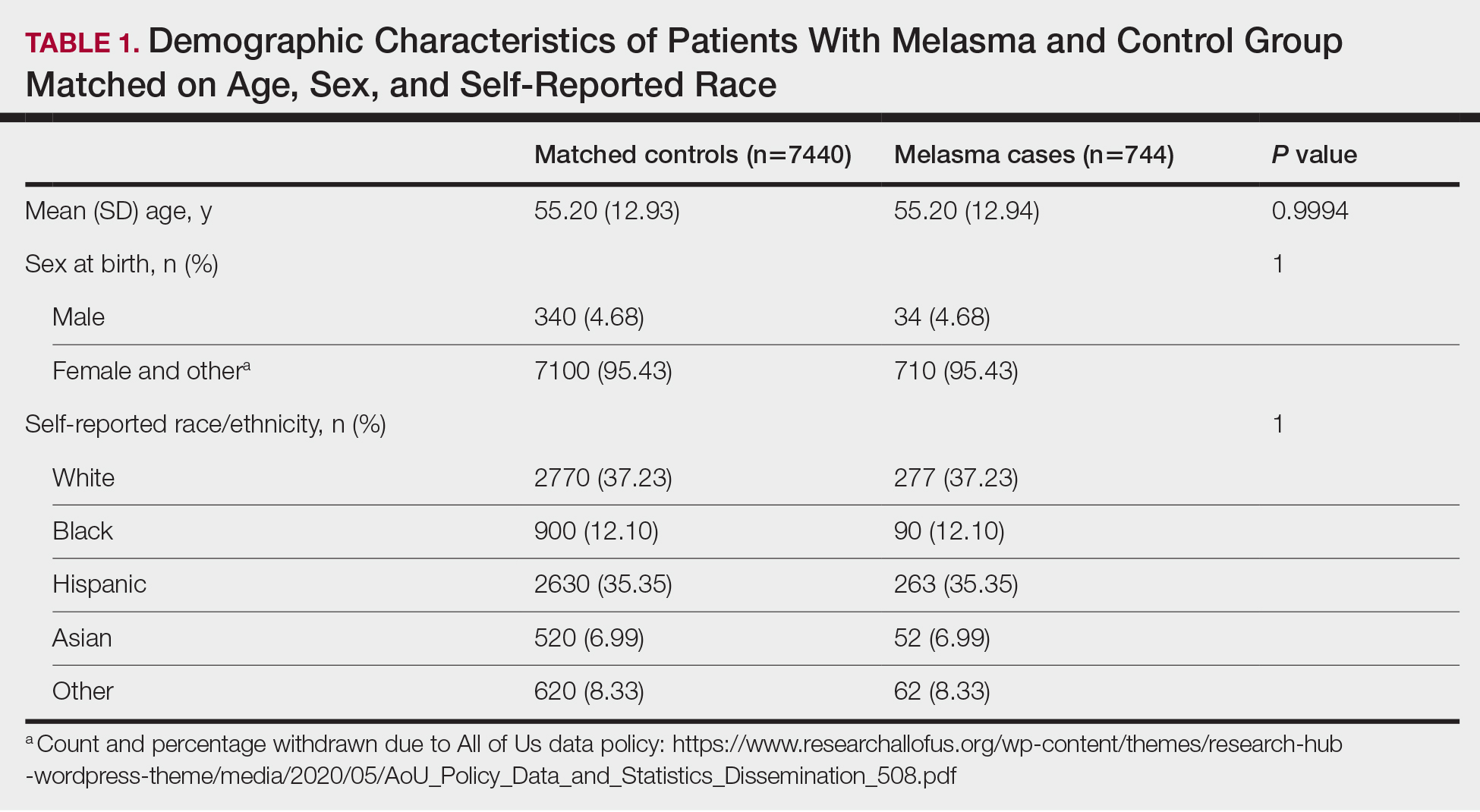

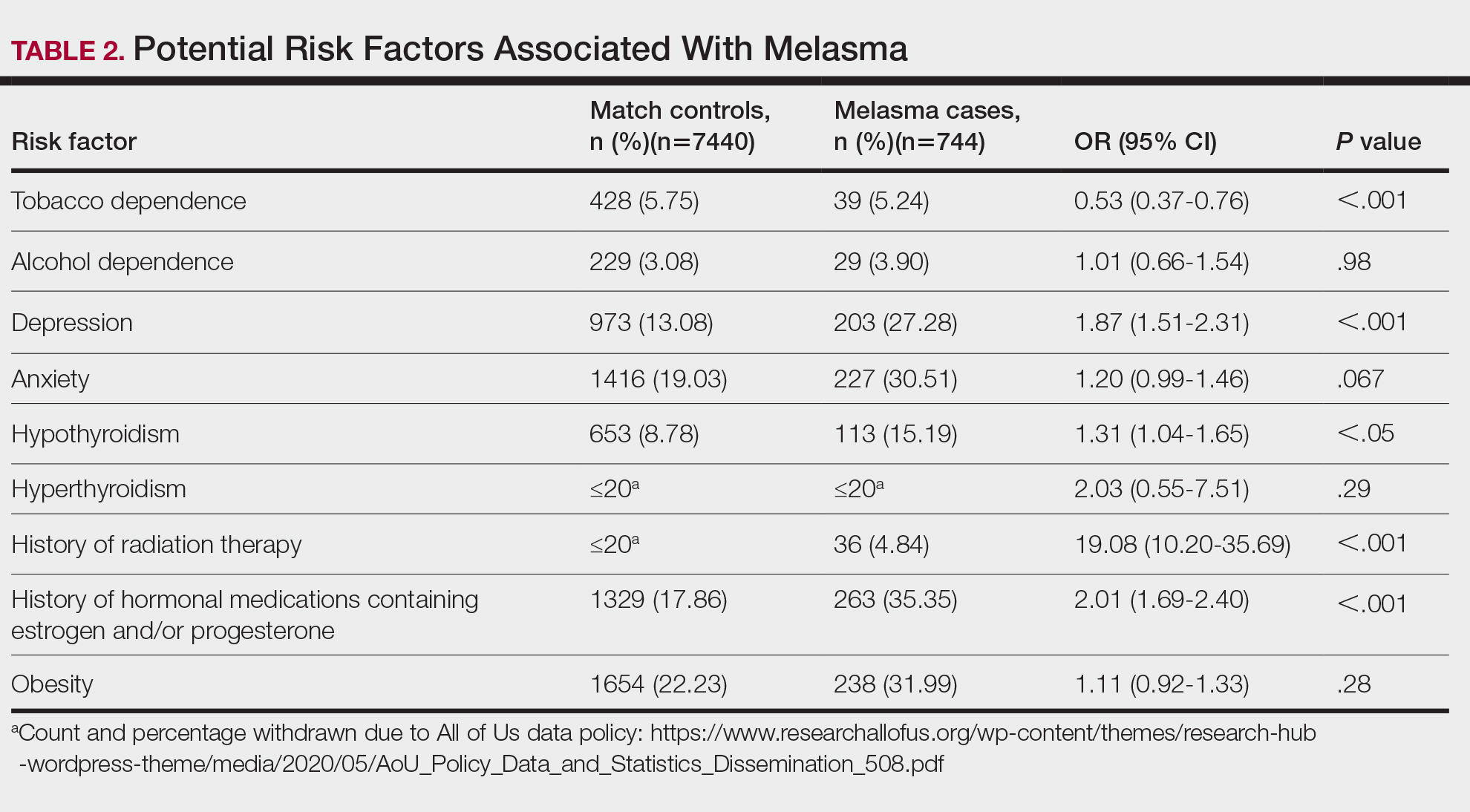

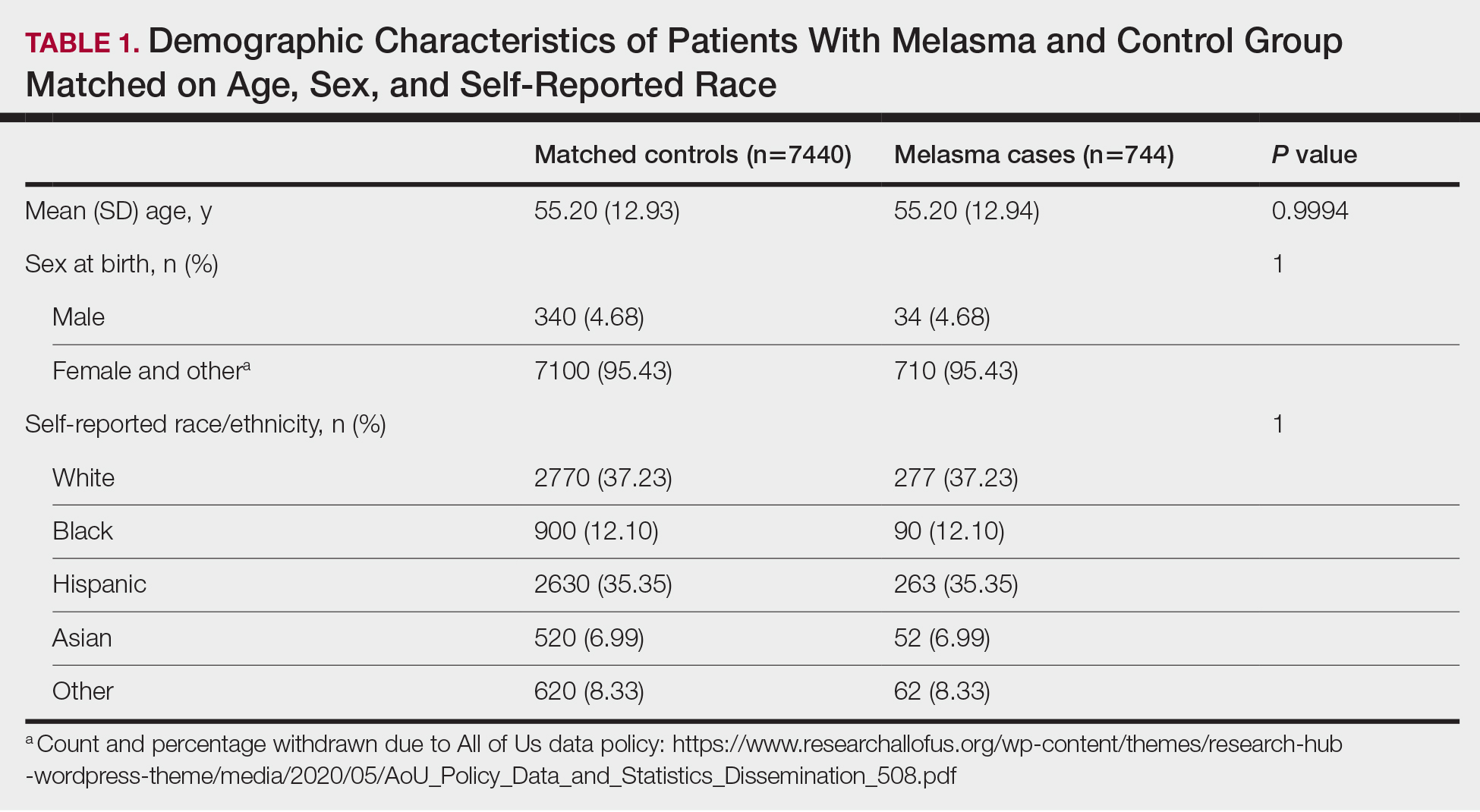

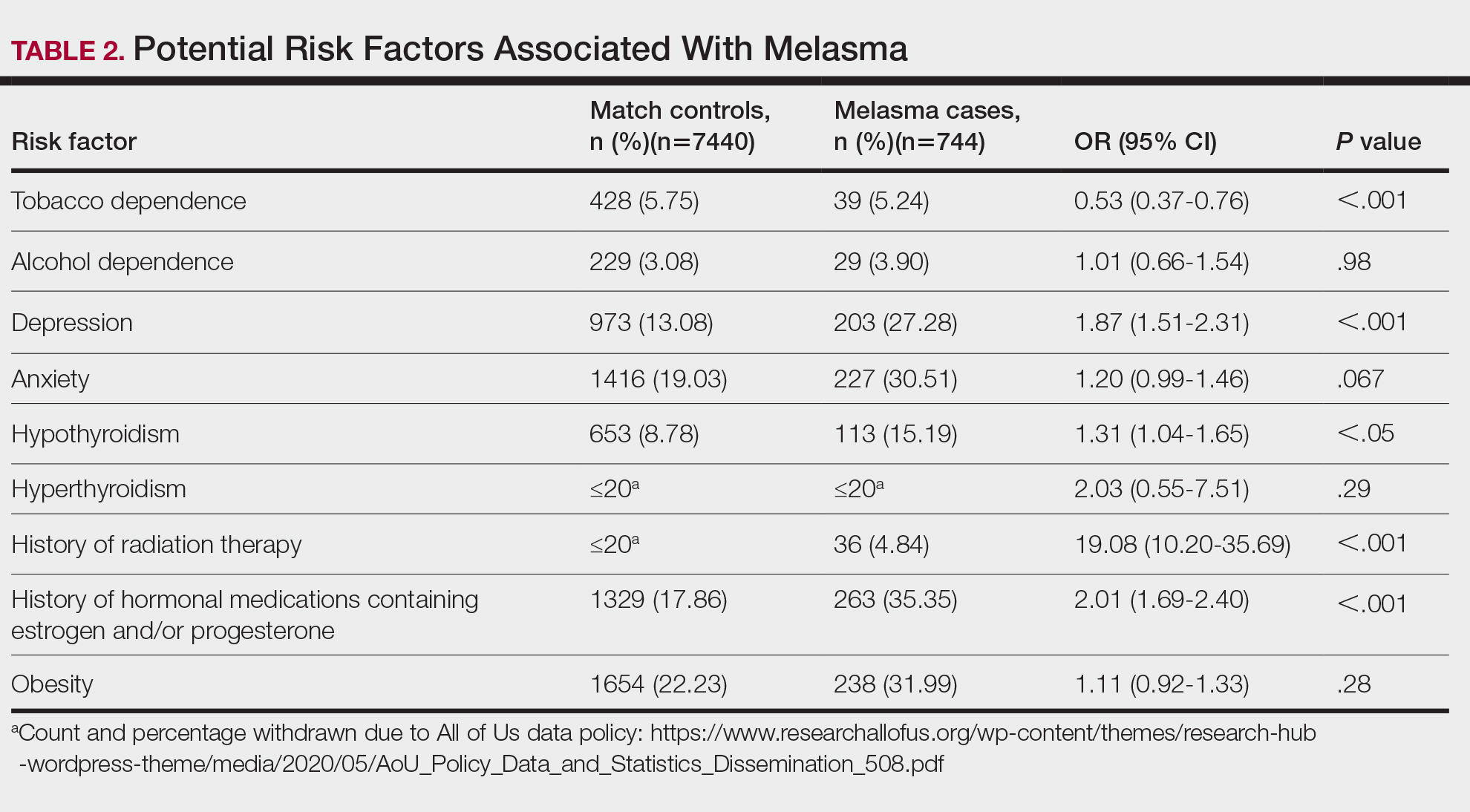

We identified 744 melasma cases (mean age, 55.20 years; 95.43% female; 12.10% Black) and 7440 controls with similar demographics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity) between groups (all P>.05 [Table 1]). Patients with a melasma diagnosis were more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.31 [P<.001]) or hypothyroidism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04-1.65 [P<.05]), or a history of radiation therapy (OR, 19.08; 95% CI, 10.20-35.69 [P<.001]) and/or estrogen and/or progesterone therapy (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.69-2.40 [P<.001]) prior to melasma diagnosis. A diagnosis of anxiety prior to melasma diagnosis trended toward an association with melasma (P=.067). Pre-existing alcohol dependence, obesity, and hyperthyroidism were not associated with melasma (P=.98, P=.28, and P=.29, respectively). A diagnosis of tobacco dependence was associated with a decreased melasma risk (OR, 0.53, 95% CI, 0.37-0.76)[P<.001])(Table 2).

Our study results suggest that pre-existing depression was a risk factor for subsequent melasma diagnosis. Depression may exacerbate stress, leading to increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis as well as increased levels of cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which subsequently act on melanocytes to increase melanogenesis.3 A retrospective study of 254 participants, including 127 with melasma, showed that increased melasma severity was associated with higher rates of depression (P=.002)2; however, the risk for melasma following a depression diagnosis has not been reported.

Our results also showed that hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk for melasma. On a cellular level, hypothyroidism can cause systemic inflammation, potentailly leading to increased stress and melanogenesis via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4 These findings are similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, anti–thyroid peroxidase, and antithyroglobulin antibody levels associated with increased melasma risk (mean difference between cases and controls, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.18-0.47]; pooled association, P=.020; mean difference between cases and controls, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.01-0.55], respectively).5

Patients in our cohort who had a history of radiation therapy were 19 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to findings of a survey-based study of 421 breast cancer survivors in which 336 (79.81%) reported hyperpigmentation in irradiated areas.6 Patients in our cohort who had a history of estrogen and/or progesterone therapy were 2 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to a case-control study of 207 patients with melasma and 207 controls that showed combined oral contraceptives increased risk for melasma (OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41; P<.01).3

Tobacco use is not a well-known protective factor against melasma. Prior studies have indicated that tobacco smoking activates melanocytes via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, leading to hyperpigmentation.7 Although exposure to cigarette smoke decreases angiogenesis and would more likely lead to hyperpigmentation, nicotine exposure has been shown to increase angiogenesis, which could lead to increased blood flow and partially explain the protection against melasma demonstrated in our cohort.8 Future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

Limitations of our study include lack of information about melasma severity and information about prior melasma treatment in our cohort as well as possible misdiagnosis reported in the dataset.

Our results demonstrated that pre-existing depression and hypothyroidism as well as a history of radiation or estrogen and/or progesterone therapies are potential risk factors for melasma. Therefore, we recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction, and patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/or progesterone therapy should be counseled on their increased risk for melasma. Future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of comorbidities such as hypothyroidism and depression improve melasma severity. The decreased risk for melasma associated with tobacco use also requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments—The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants, who we gratefully acknowledge for their contributions and without whom this research would not have been possible. We also thank the All of Us Research Program for making the participant data examined in this study available to us.

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Platsidaki E, Efstathiou V, Markantoni V, et al. Self-esteem, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with melasma living in a sunny mediterranean area: results from a prospective cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:1127-1136. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00915-1

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Erge E, Kiziltunc C, Balci SB, et al. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio (published January 22, 2023). Diseases. 2023;11:15. doi:10.3390/diseases11010015

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, et al. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1231-1238. doi:10.1111/ijd.14497

- Chu CN, Hu KC, Wu RS, et al. Radiation-irritated skin and hyperpigmentation may impact the quality of life of breast cancer patients after whole breast radiotherapy (published March 31, 2021). BMC Cancer. 2021;21:330. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08047-5

- Nakamura M, Ueda Y, Hayashi M, et al. Tobacco smoke-induced skin pigmentation is mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:556-558. doi:10.1111/exd.12170

- Ejaz S, Lim CW. Toxicological overview of cigarette smoking on angiogenesis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:335-344. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2005.03.011

To the Editor:

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is characterized by symmetric hyperpigmented patches affecting sun-exposed areas. Women commonly develop this condition during pregnancy, suggesting a connection between melasma and increased female sex hormone levels.1 Other hypothesized risk factors include sun exposure, genetic susceptibility, estrogen and/or progesterone therapy, and thyroid abnormalities but have not been corroborated.2 Treatment options are limited because the pathogenesis is poorly understood; thus, we aimed to analyze melasma risk factors using a national database with a nested case-control approach.

We conducted a matched case-control study using the Registered Tier dataset (version 7) from the National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program (https://allofus.nih.gov/), which is available to authorized users through the program’s Researcher Workbench and includes more than 413,000 total participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, through July 1, 2022. Cases included patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of melasma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code L81.1 [Chloasma]; concept ID 4264234 [Chloasma]; and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] code 36209000 [Chloasma]), and controls without a diagnosis of melasma were matched in a 1:10 ratio based on age, sex, and self-reported race. Concept IDs and SNOMED codes were used to identify individuals in each cohort with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (concept IDs 433753, 435243, 4218106; SNOMED codes 15167005, 66590003, 7200002), depression (concept ID 440383; SNOMED code 35489007), hypothyroidism (concept ID 140673; SNOMED code 40930008), hyperthyroidism (concept ID 4142479; SNOMED code 34486009), anxiety (concept IDs 441542, 442077, 434613; SNOMED codes 48694002, 197480006, 21897009), tobacco dependence (concept IDs 37109023, 437264, 4099811; SNOMED codes 16077091000119107, 89765005, 191887008), or obesity (concept IDs 433736 and 434005; SNOMED codes 414916001 and 238136002), or with a history of radiation therapy (concept IDs 4085340, 4311117, 4061844, 4029715; SNOMED codes 24803000, 85983004, 200861004, 108290001) or hormonal medications containing estrogen and/or progesterone, including oral medications and implants (concept IDs 21602445, 40254009, 21602514, 21603814, 19049228, 21602529, 1549080, 1551673, 1549254, 21602472, 21602446, 21602450, 21602515, 21602566, 21602473, 21602567, 21602488, 21602585, 1596779, 1586808, 21602524). In our case cohort, diagnoses and exposures to treatments were only considered for analysis if they occurred prior to melasma diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and P values between melasma and each comorbidity or exposure to the treatments specified. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

We identified 744 melasma cases (mean age, 55.20 years; 95.43% female; 12.10% Black) and 7440 controls with similar demographics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity) between groups (all P>.05 [Table 1]). Patients with a melasma diagnosis were more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.31 [P<.001]) or hypothyroidism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04-1.65 [P<.05]), or a history of radiation therapy (OR, 19.08; 95% CI, 10.20-35.69 [P<.001]) and/or estrogen and/or progesterone therapy (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.69-2.40 [P<.001]) prior to melasma diagnosis. A diagnosis of anxiety prior to melasma diagnosis trended toward an association with melasma (P=.067). Pre-existing alcohol dependence, obesity, and hyperthyroidism were not associated with melasma (P=.98, P=.28, and P=.29, respectively). A diagnosis of tobacco dependence was associated with a decreased melasma risk (OR, 0.53, 95% CI, 0.37-0.76)[P<.001])(Table 2).

Our study results suggest that pre-existing depression was a risk factor for subsequent melasma diagnosis. Depression may exacerbate stress, leading to increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis as well as increased levels of cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which subsequently act on melanocytes to increase melanogenesis.3 A retrospective study of 254 participants, including 127 with melasma, showed that increased melasma severity was associated with higher rates of depression (P=.002)2; however, the risk for melasma following a depression diagnosis has not been reported.

Our results also showed that hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk for melasma. On a cellular level, hypothyroidism can cause systemic inflammation, potentailly leading to increased stress and melanogenesis via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4 These findings are similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, anti–thyroid peroxidase, and antithyroglobulin antibody levels associated with increased melasma risk (mean difference between cases and controls, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.18-0.47]; pooled association, P=.020; mean difference between cases and controls, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.01-0.55], respectively).5

Patients in our cohort who had a history of radiation therapy were 19 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to findings of a survey-based study of 421 breast cancer survivors in which 336 (79.81%) reported hyperpigmentation in irradiated areas.6 Patients in our cohort who had a history of estrogen and/or progesterone therapy were 2 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to a case-control study of 207 patients with melasma and 207 controls that showed combined oral contraceptives increased risk for melasma (OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41; P<.01).3

Tobacco use is not a well-known protective factor against melasma. Prior studies have indicated that tobacco smoking activates melanocytes via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, leading to hyperpigmentation.7 Although exposure to cigarette smoke decreases angiogenesis and would more likely lead to hyperpigmentation, nicotine exposure has been shown to increase angiogenesis, which could lead to increased blood flow and partially explain the protection against melasma demonstrated in our cohort.8 Future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

Limitations of our study include lack of information about melasma severity and information about prior melasma treatment in our cohort as well as possible misdiagnosis reported in the dataset.

Our results demonstrated that pre-existing depression and hypothyroidism as well as a history of radiation or estrogen and/or progesterone therapies are potential risk factors for melasma. Therefore, we recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction, and patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/or progesterone therapy should be counseled on their increased risk for melasma. Future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of comorbidities such as hypothyroidism and depression improve melasma severity. The decreased risk for melasma associated with tobacco use also requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments—The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants, who we gratefully acknowledge for their contributions and without whom this research would not have been possible. We also thank the All of Us Research Program for making the participant data examined in this study available to us.

To the Editor:

Melasma (also known as chloasma) is characterized by symmetric hyperpigmented patches affecting sun-exposed areas. Women commonly develop this condition during pregnancy, suggesting a connection between melasma and increased female sex hormone levels.1 Other hypothesized risk factors include sun exposure, genetic susceptibility, estrogen and/or progesterone therapy, and thyroid abnormalities but have not been corroborated.2 Treatment options are limited because the pathogenesis is poorly understood; thus, we aimed to analyze melasma risk factors using a national database with a nested case-control approach.

We conducted a matched case-control study using the Registered Tier dataset (version 7) from the National Institute of Health’s All of Us Research Program (https://allofus.nih.gov/), which is available to authorized users through the program’s Researcher Workbench and includes more than 413,000 total participants enrolled from May 1, 2018, through July 1, 2022. Cases included patients 18 years and older with a diagnosis of melasma (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification code L81.1 [Chloasma]; concept ID 4264234 [Chloasma]; and Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine [SNOMED] code 36209000 [Chloasma]), and controls without a diagnosis of melasma were matched in a 1:10 ratio based on age, sex, and self-reported race. Concept IDs and SNOMED codes were used to identify individuals in each cohort with a diagnosis of alcohol dependence (concept IDs 433753, 435243, 4218106; SNOMED codes 15167005, 66590003, 7200002), depression (concept ID 440383; SNOMED code 35489007), hypothyroidism (concept ID 140673; SNOMED code 40930008), hyperthyroidism (concept ID 4142479; SNOMED code 34486009), anxiety (concept IDs 441542, 442077, 434613; SNOMED codes 48694002, 197480006, 21897009), tobacco dependence (concept IDs 37109023, 437264, 4099811; SNOMED codes 16077091000119107, 89765005, 191887008), or obesity (concept IDs 433736 and 434005; SNOMED codes 414916001 and 238136002), or with a history of radiation therapy (concept IDs 4085340, 4311117, 4061844, 4029715; SNOMED codes 24803000, 85983004, 200861004, 108290001) or hormonal medications containing estrogen and/or progesterone, including oral medications and implants (concept IDs 21602445, 40254009, 21602514, 21603814, 19049228, 21602529, 1549080, 1551673, 1549254, 21602472, 21602446, 21602450, 21602515, 21602566, 21602473, 21602567, 21602488, 21602585, 1596779, 1586808, 21602524). In our case cohort, diagnoses and exposures to treatments were only considered for analysis if they occurred prior to melasma diagnosis.

Multivariate logistic regression was performed to calculate odds ratios and P values between melasma and each comorbidity or exposure to the treatments specified. Statistical significance was set at P<.05.

We identified 744 melasma cases (mean age, 55.20 years; 95.43% female; 12.10% Black) and 7440 controls with similar demographics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity) between groups (all P>.05 [Table 1]). Patients with a melasma diagnosis were more likely to have a pre-existing diagnosis of depression (OR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.51-2.31 [P<.001]) or hypothyroidism (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.04-1.65 [P<.05]), or a history of radiation therapy (OR, 19.08; 95% CI, 10.20-35.69 [P<.001]) and/or estrogen and/or progesterone therapy (OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.69-2.40 [P<.001]) prior to melasma diagnosis. A diagnosis of anxiety prior to melasma diagnosis trended toward an association with melasma (P=.067). Pre-existing alcohol dependence, obesity, and hyperthyroidism were not associated with melasma (P=.98, P=.28, and P=.29, respectively). A diagnosis of tobacco dependence was associated with a decreased melasma risk (OR, 0.53, 95% CI, 0.37-0.76)[P<.001])(Table 2).

Our study results suggest that pre-existing depression was a risk factor for subsequent melasma diagnosis. Depression may exacerbate stress, leading to increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis as well as increased levels of cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone, which subsequently act on melanocytes to increase melanogenesis.3 A retrospective study of 254 participants, including 127 with melasma, showed that increased melasma severity was associated with higher rates of depression (P=.002)2; however, the risk for melasma following a depression diagnosis has not been reported.

Our results also showed that hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk for melasma. On a cellular level, hypothyroidism can cause systemic inflammation, potentailly leading to increased stress and melanogenesis via activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.4 These findings are similar to a systematic review and meta-analysis reporting increased thyroid-stimulating hormone, anti–thyroid peroxidase, and antithyroglobulin antibody levels associated with increased melasma risk (mean difference between cases and controls, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.18-0.47]; pooled association, P=.020; mean difference between cases and controls, 0.28 [95% CI, 0.01-0.55], respectively).5

Patients in our cohort who had a history of radiation therapy were 19 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to findings of a survey-based study of 421 breast cancer survivors in which 336 (79.81%) reported hyperpigmentation in irradiated areas.6 Patients in our cohort who had a history of estrogen and/or progesterone therapy were 2 times more likely to develop melasma, similar to a case-control study of 207 patients with melasma and 207 controls that showed combined oral contraceptives increased risk for melasma (OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 1.08-1.41; P<.01).3

Tobacco use is not a well-known protective factor against melasma. Prior studies have indicated that tobacco smoking activates melanocytes via the Wnt/β-Catenin pathway, leading to hyperpigmentation.7 Although exposure to cigarette smoke decreases angiogenesis and would more likely lead to hyperpigmentation, nicotine exposure has been shown to increase angiogenesis, which could lead to increased blood flow and partially explain the protection against melasma demonstrated in our cohort.8 Future studies are needed to explore this relationship.

Limitations of our study include lack of information about melasma severity and information about prior melasma treatment in our cohort as well as possible misdiagnosis reported in the dataset.

Our results demonstrated that pre-existing depression and hypothyroidism as well as a history of radiation or estrogen and/or progesterone therapies are potential risk factors for melasma. Therefore, we recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction, and patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/or progesterone therapy should be counseled on their increased risk for melasma. Future studies are needed to determine whether treatment of comorbidities such as hypothyroidism and depression improve melasma severity. The decreased risk for melasma associated with tobacco use also requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments—The All of Us Research Program is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Office of the Director: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA #: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; The Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276.

In addition, the All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants, who we gratefully acknowledge for their contributions and without whom this research would not have been possible. We also thank the All of Us Research Program for making the participant data examined in this study available to us.

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Platsidaki E, Efstathiou V, Markantoni V, et al. Self-esteem, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with melasma living in a sunny mediterranean area: results from a prospective cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:1127-1136. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00915-1

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Erge E, Kiziltunc C, Balci SB, et al. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio (published January 22, 2023). Diseases. 2023;11:15. doi:10.3390/diseases11010015

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, et al. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1231-1238. doi:10.1111/ijd.14497

- Chu CN, Hu KC, Wu RS, et al. Radiation-irritated skin and hyperpigmentation may impact the quality of life of breast cancer patients after whole breast radiotherapy (published March 31, 2021). BMC Cancer. 2021;21:330. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08047-5

- Nakamura M, Ueda Y, Hayashi M, et al. Tobacco smoke-induced skin pigmentation is mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:556-558. doi:10.1111/exd.12170

- Ejaz S, Lim CW. Toxicological overview of cigarette smoking on angiogenesis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:335-344. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2005.03.011

- Filoni A, Mariano M, Cameli N. Melasma: how hormones can modulate skin pigmentation. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18:458-463. doi:10.1111/jocd.12877

- Platsidaki E, Efstathiou V, Markantoni V, et al. Self-esteem, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with melasma living in a sunny mediterranean area: results from a prospective cross-sectional study. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2023;13:1127-1136. doi:10.1007/s13555-023-00915-1

- Handel AC, Lima PB, Tonolli VM, et al. Risk factors for facial melasma in women: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:588-594. doi:10.1111/bjd.13059

- Erge E, Kiziltunc C, Balci SB, et al. A novel inflammatory marker for the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: platelet-count-to-lymphocyte-count ratio (published January 22, 2023). Diseases. 2023;11:15. doi:10.3390/diseases11010015

- Kheradmand M, Afshari M, Damiani G, et al. Melasma and thyroid disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1231-1238. doi:10.1111/ijd.14497

- Chu CN, Hu KC, Wu RS, et al. Radiation-irritated skin and hyperpigmentation may impact the quality of life of breast cancer patients after whole breast radiotherapy (published March 31, 2021). BMC Cancer. 2021;21:330. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-08047-5

- Nakamura M, Ueda Y, Hayashi M, et al. Tobacco smoke-induced skin pigmentation is mediated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:556-558. doi:10.1111/exd.12170

- Ejaz S, Lim CW. Toxicological overview of cigarette smoking on angiogenesis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;20:335-344. doi:10.1016/j.etap.2005.03.011

Practice Points

- Treatment options for melasma are limited due to its poorly understood pathogenesis.

- Depression and hypothyroidism and/or history of exposure to radiation and hormonal therapies may increase melasma risk.

- We recommend that patients with melasma be screened for depression and thyroid dysfunction. Patients undergoing radiation therapy or starting estrogen and/ or progesterone therapy should be counseled on the increased risk for melasma.

Moving Beyond Traditional Methods for Treatment of Acne Keloidalis Nuchae

The Comparison

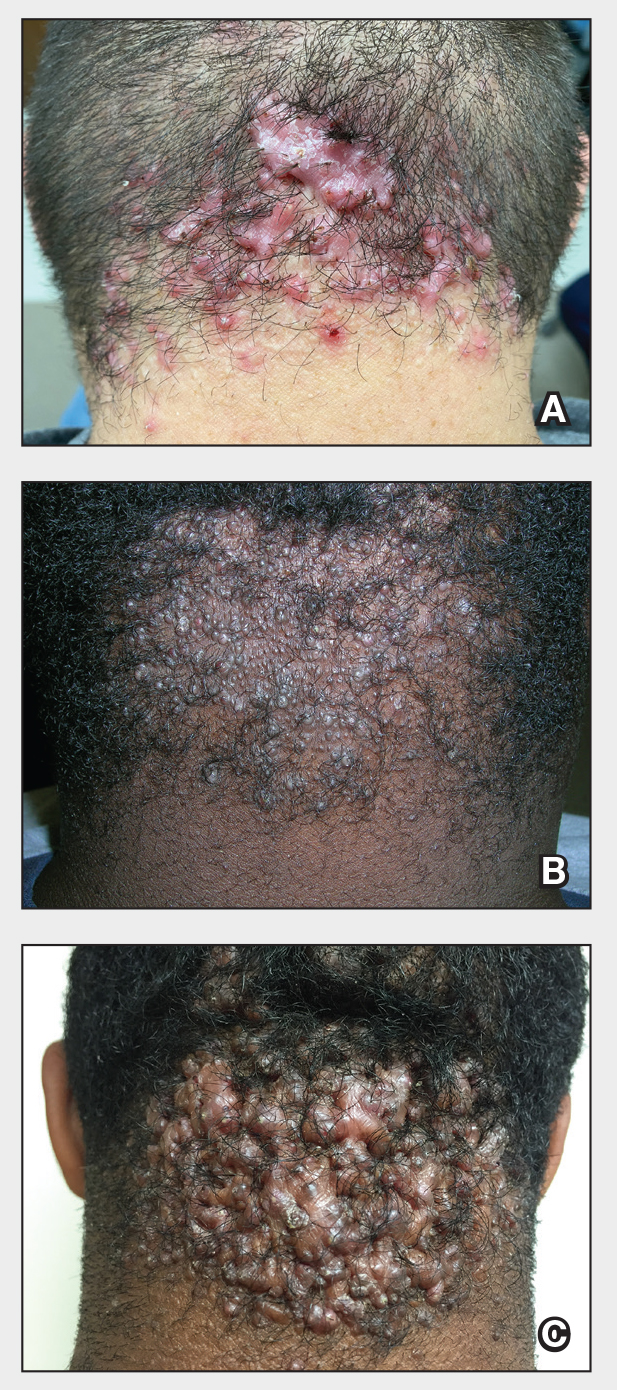

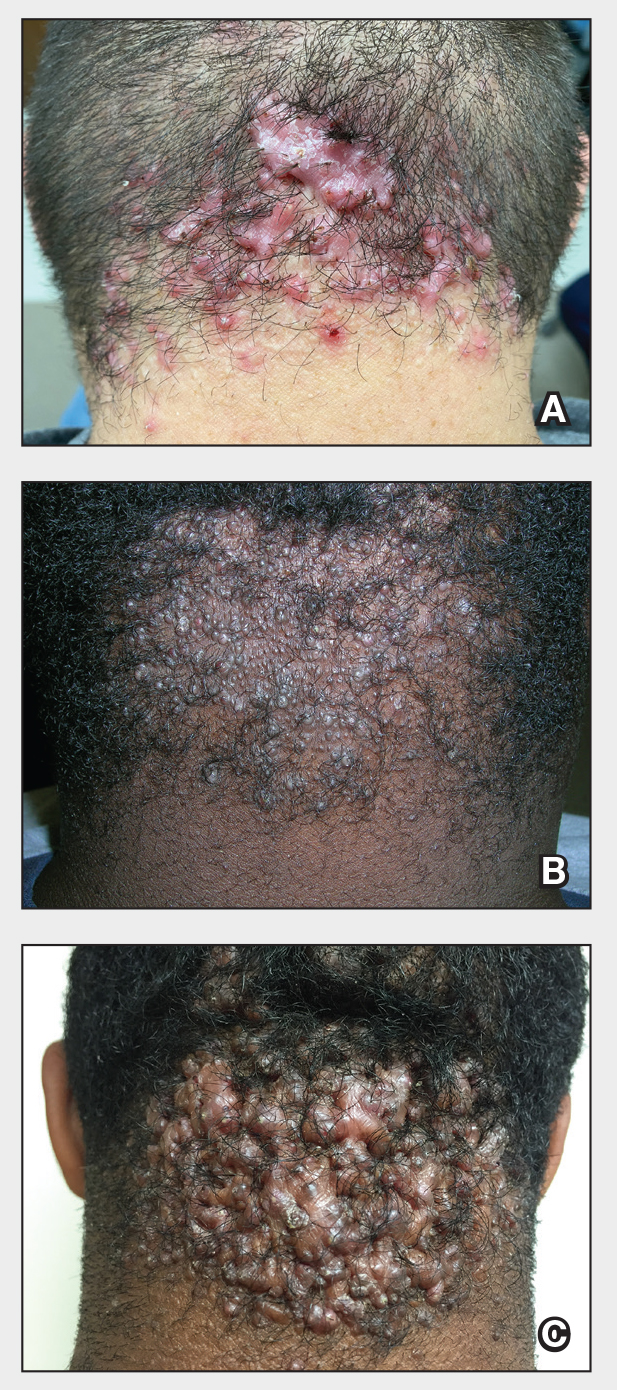

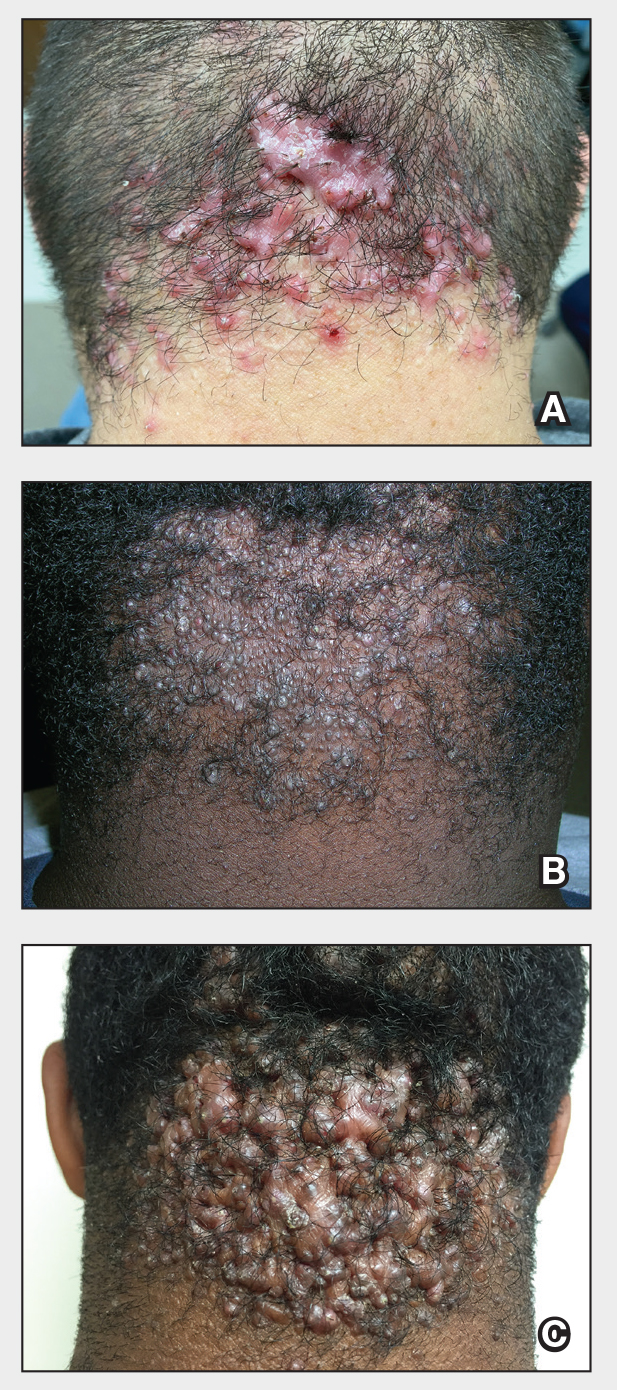

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory condition commonly affecting the occipital scalp and posterior neck. It causes discrete or extensive fibrosing papules that may coalesce to form pronounced tumorlike masses1,2 with scarring alopecia (Figure, A–C).3 Pustules, hair tufts, secondary bacterial infections, abscesses, and sinus tracts also may occur.1 The pathogenesis of AKN has been characterized as varying stages of follicular inflammation at the infundibular and isthmus levels followed by fibrotic occlusion of the follicular lumen.4 Pruritus, pain, bleeding, oozing, and a feeling of scalp tightness may occur.1,5

Umar et al6 performed a retrospective review of 108 men with AKN—58% of African descent, 37% Hispanic, 3% Asian, and 2% Middle Eastern—and proposed a 3-tier classification system for AKN. Tier 1 focused on the distribution and sagittal spread of AKN lesions between the clinical demarcation lines of the occipital notch and posterior hairline. Tier 2 focused on the type of lesions present—discrete papules or nodules, coalescing/abutting lesions, plaques (raised, atrophic, or indurated), or dome-shaped tumoral masses. Tier 3 focused on the presence or absence of co-existing dissecting cellulitis or folliculitis decalvans.6

Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae primarily manifests in adolescent and adult men of African or Afro-Caribbean descent.7 Among African American men, the prevalence of AKN ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%.8 Similar ranges have been reported among Nigerian, South African, and West African men.1 Acne keloidalis nuchae also affects Asian and Hispanic men but rarely is seen in non-Hispanic White men or in women of any ethnicity.9,10 The male to female ratio is 20:1.1,11 Hair texture, hairstyling practices such as closely shaved or faded haircuts, and genetics likely contribute to development of AKN. Sports and occupations that require the use of headgear or a tight collar may increase the risk for AKN.12

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

- The lesions of AKN range in color from pink to dark brown or black. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hyperchromia may be present around AKN lesions.

- Chronicity of AKN may lead to extended use of high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids, which causes transient or long-lasting hypopigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

Worth noting

- Acne keloidalis nuchae can be disfiguring, which negatively impacts quality of life and self-esteem.12

- Some occupations (eg, military, police) have hair policies that may not be favorable to those with or at risk for AKN.

- Patients with AKN are 2 to 3 times more likely to present with metabolic syndrome, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or obesity.13

Treatment

There are no treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically for AKN. Treatment approaches are based on the pathophysiology, secondary impacts on the skin, and disease severity. Growing out the hair may prevent worsening and/or decrease the risk for new lesions.6

- Options include but are not limited to topical and systemic therapies (eg, topical corticosteroids, oral or topical antibiotics, isotretinoin, topical retinoids, imiquimod, pimecrolimus), light devices (eg, phototherapy, laser), ablative therapies (eg, laser, cryotherapy, radiotherapy), and surgery (eg, excision, follicular unit excision), often in combination.6,14,15

- Intralesional triamcinolone injections are considered standard of care. Adotama et al16 found that injecting triamcinolone into the deep dermis in the area of flat or papular AKN yielded better control of inflammation and decreased appearance of lesions compared with injecting individual lesions.

- For extensive AKN lesions that do not respond to less-invasive therapies, consider surgical techniques,6,17 such as follicular unit excision18 and more extensive surgical excisions building on approaches from pioneers Drs. John Kenney and Harold Pierce.19 An innovative surgical approach for removal of large AKNs is the bat excision technique—wound shape resembles a bat in a spread-eagled position—with secondary intention healing with or without debridement and/or tension sutures. The resulting linear scar acts as a new posterior hair line.20

Health disparity highlights

Access to a dermatologic or plastic surgeon with expertise in the surgical treatment of large AKNs may be challenging but is needed to reduce risk for recurrence and adverse events.

Close-cropped haircuts on the occipital scalp, which are particularly popular among men of African descent, increase the risk for AKN.5 Although this grooming style may be a personal preference, other hairstyles commonly worn by those with tightly coiled hair may be deemed “unprofessional” in society or the workplace,21 which leads to hairstyling practices that may increase the risk for AKN.

Acne keloidalis nuchae remains an understudied entity that adversely affects patients with skin of color.

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489. doi:10.2147/CCID.S99225

- Al Aboud DM, Badri T. Acne keloidalis nuchae. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459135/ 3.

- Sperling LC, Homoky C, Pratt L, et al. Acne keloidalis is a form of primary scarring alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:479-484.

- Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis: transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121. doi:10.1097/00000372-199004000-00001

- Saka B, Akakpo A-S, Téclessou JN, et al. Risk factors associated with acne keloidalis nuchae in black subjects: a case-control study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2020;147:350-354. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2020.01.007

- Umar S, Lee DJ, Lullo JJ. A retrospective cohort study and clinical classification system of acne keloidalis nuchae. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:E61-E67.

- Reja M, Silverberg NB. Acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Silverberg NB, Durán-McKinster C, Tay YK, eds. Pediatric Skin of Color. Springer; 2015:141-145. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6654-3_16 8.

- Knable AL Jr, Hanke CW, Gonin R. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in football players. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:570-574. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70173-7

- Umar S, Ton D, Carter MJ, et al. Unveiling a shared precursor condition for acne keloidalis nuchae and primary cicatricial alopecias. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:2315-2327. doi:10.2147/CCID.S422310

- Na K, Oh SH, Kim SK. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Asian: a single institutional experience. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189790. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189790

- Ogunbiyi A, George A. Acne keloidalis in females: case report and review of literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:736-738.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Kridin K, Solomon A, Tzur-Bitan D, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae and the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:733-739. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00541-z

- Smart K, Rodriguez I, Worswick S. Comorbidities and treatment options for acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Ther. Published online May 25, 2024. doi:10.1155/2024/8336926

- Callender VD, Young CM, Haverstock CL, et al. An open label study of clobetasol propionate 0.05% and betamethasone valerate 0.12% foams in the treatment of mild to moderate acne keloidalis. Cutis. 2005;75:317-321.

- Adotama P, Grullon K, Ali S, et al. How we do it: our method for triamcinolone injections of acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:713-714. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003803

- Beckett N, Lawson C, Cohen G. Electrosurgical excision of acne keloidalis nuchae with secondary intention healing. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:36-39.

- Esmat SM, Abdel Hay RM, Abu Zeid OM, et al. The efficacy of laser-assisted hair removal in the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae; a pilot study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:645-650. doi:10.1684/ejd.2012.1830

- Dillard AD, Quarles FN. African-American pioneers in dermatology. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:717-730.

- Umar S, David CV, Castillo JR, et al. Innovative surgical approaches and selection criteria of large acne keloidalis nuchae lesions. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:E2215. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002215

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

The Comparison

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory condition commonly affecting the occipital scalp and posterior neck. It causes discrete or extensive fibrosing papules that may coalesce to form pronounced tumorlike masses1,2 with scarring alopecia (Figure, A–C).3 Pustules, hair tufts, secondary bacterial infections, abscesses, and sinus tracts also may occur.1 The pathogenesis of AKN has been characterized as varying stages of follicular inflammation at the infundibular and isthmus levels followed by fibrotic occlusion of the follicular lumen.4 Pruritus, pain, bleeding, oozing, and a feeling of scalp tightness may occur.1,5

Umar et al6 performed a retrospective review of 108 men with AKN—58% of African descent, 37% Hispanic, 3% Asian, and 2% Middle Eastern—and proposed a 3-tier classification system for AKN. Tier 1 focused on the distribution and sagittal spread of AKN lesions between the clinical demarcation lines of the occipital notch and posterior hairline. Tier 2 focused on the type of lesions present—discrete papules or nodules, coalescing/abutting lesions, plaques (raised, atrophic, or indurated), or dome-shaped tumoral masses. Tier 3 focused on the presence or absence of co-existing dissecting cellulitis or folliculitis decalvans.6

Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae primarily manifests in adolescent and adult men of African or Afro-Caribbean descent.7 Among African American men, the prevalence of AKN ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%.8 Similar ranges have been reported among Nigerian, South African, and West African men.1 Acne keloidalis nuchae also affects Asian and Hispanic men but rarely is seen in non-Hispanic White men or in women of any ethnicity.9,10 The male to female ratio is 20:1.1,11 Hair texture, hairstyling practices such as closely shaved or faded haircuts, and genetics likely contribute to development of AKN. Sports and occupations that require the use of headgear or a tight collar may increase the risk for AKN.12

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

- The lesions of AKN range in color from pink to dark brown or black. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hyperchromia may be present around AKN lesions.

- Chronicity of AKN may lead to extended use of high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids, which causes transient or long-lasting hypopigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

Worth noting

- Acne keloidalis nuchae can be disfiguring, which negatively impacts quality of life and self-esteem.12

- Some occupations (eg, military, police) have hair policies that may not be favorable to those with or at risk for AKN.

- Patients with AKN are 2 to 3 times more likely to present with metabolic syndrome, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or obesity.13

Treatment

There are no treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically for AKN. Treatment approaches are based on the pathophysiology, secondary impacts on the skin, and disease severity. Growing out the hair may prevent worsening and/or decrease the risk for new lesions.6

- Options include but are not limited to topical and systemic therapies (eg, topical corticosteroids, oral or topical antibiotics, isotretinoin, topical retinoids, imiquimod, pimecrolimus), light devices (eg, phototherapy, laser), ablative therapies (eg, laser, cryotherapy, radiotherapy), and surgery (eg, excision, follicular unit excision), often in combination.6,14,15

- Intralesional triamcinolone injections are considered standard of care. Adotama et al16 found that injecting triamcinolone into the deep dermis in the area of flat or papular AKN yielded better control of inflammation and decreased appearance of lesions compared with injecting individual lesions.

- For extensive AKN lesions that do not respond to less-invasive therapies, consider surgical techniques,6,17 such as follicular unit excision18 and more extensive surgical excisions building on approaches from pioneers Drs. John Kenney and Harold Pierce.19 An innovative surgical approach for removal of large AKNs is the bat excision technique—wound shape resembles a bat in a spread-eagled position—with secondary intention healing with or without debridement and/or tension sutures. The resulting linear scar acts as a new posterior hair line.20

Health disparity highlights

Access to a dermatologic or plastic surgeon with expertise in the surgical treatment of large AKNs may be challenging but is needed to reduce risk for recurrence and adverse events.

Close-cropped haircuts on the occipital scalp, which are particularly popular among men of African descent, increase the risk for AKN.5 Although this grooming style may be a personal preference, other hairstyles commonly worn by those with tightly coiled hair may be deemed “unprofessional” in society or the workplace,21 which leads to hairstyling practices that may increase the risk for AKN.

Acne keloidalis nuchae remains an understudied entity that adversely affects patients with skin of color.

The Comparison

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a chronic inflammatory condition commonly affecting the occipital scalp and posterior neck. It causes discrete or extensive fibrosing papules that may coalesce to form pronounced tumorlike masses1,2 with scarring alopecia (Figure, A–C).3 Pustules, hair tufts, secondary bacterial infections, abscesses, and sinus tracts also may occur.1 The pathogenesis of AKN has been characterized as varying stages of follicular inflammation at the infundibular and isthmus levels followed by fibrotic occlusion of the follicular lumen.4 Pruritus, pain, bleeding, oozing, and a feeling of scalp tightness may occur.1,5

Umar et al6 performed a retrospective review of 108 men with AKN—58% of African descent, 37% Hispanic, 3% Asian, and 2% Middle Eastern—and proposed a 3-tier classification system for AKN. Tier 1 focused on the distribution and sagittal spread of AKN lesions between the clinical demarcation lines of the occipital notch and posterior hairline. Tier 2 focused on the type of lesions present—discrete papules or nodules, coalescing/abutting lesions, plaques (raised, atrophic, or indurated), or dome-shaped tumoral masses. Tier 3 focused on the presence or absence of co-existing dissecting cellulitis or folliculitis decalvans.6

Epidemiology

Acne keloidalis nuchae primarily manifests in adolescent and adult men of African or Afro-Caribbean descent.7 Among African American men, the prevalence of AKN ranges from 0.5% to 13.6%.8 Similar ranges have been reported among Nigerian, South African, and West African men.1 Acne keloidalis nuchae also affects Asian and Hispanic men but rarely is seen in non-Hispanic White men or in women of any ethnicity.9,10 The male to female ratio is 20:1.1,11 Hair texture, hairstyling practices such as closely shaved or faded haircuts, and genetics likely contribute to development of AKN. Sports and occupations that require the use of headgear or a tight collar may increase the risk for AKN.12

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

- The lesions of AKN range in color from pink to dark brown or black. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or hyperchromia may be present around AKN lesions.

- Chronicity of AKN may lead to extended use of high-potency topical or intralesional corticosteroids, which causes transient or long-lasting hypopigmentation, especially in those with darker skin tones.

Worth noting

- Acne keloidalis nuchae can be disfiguring, which negatively impacts quality of life and self-esteem.12

- Some occupations (eg, military, police) have hair policies that may not be favorable to those with or at risk for AKN.

- Patients with AKN are 2 to 3 times more likely to present with metabolic syndrome, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or obesity.13

Treatment

There are no treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically for AKN. Treatment approaches are based on the pathophysiology, secondary impacts on the skin, and disease severity. Growing out the hair may prevent worsening and/or decrease the risk for new lesions.6

- Options include but are not limited to topical and systemic therapies (eg, topical corticosteroids, oral or topical antibiotics, isotretinoin, topical retinoids, imiquimod, pimecrolimus), light devices (eg, phototherapy, laser), ablative therapies (eg, laser, cryotherapy, radiotherapy), and surgery (eg, excision, follicular unit excision), often in combination.6,14,15

- Intralesional triamcinolone injections are considered standard of care. Adotama et al16 found that injecting triamcinolone into the deep dermis in the area of flat or papular AKN yielded better control of inflammation and decreased appearance of lesions compared with injecting individual lesions.

- For extensive AKN lesions that do not respond to less-invasive therapies, consider surgical techniques,6,17 such as follicular unit excision18 and more extensive surgical excisions building on approaches from pioneers Drs. John Kenney and Harold Pierce.19 An innovative surgical approach for removal of large AKNs is the bat excision technique—wound shape resembles a bat in a spread-eagled position—with secondary intention healing with or without debridement and/or tension sutures. The resulting linear scar acts as a new posterior hair line.20

Health disparity highlights

Access to a dermatologic or plastic surgeon with expertise in the surgical treatment of large AKNs may be challenging but is needed to reduce risk for recurrence and adverse events.

Close-cropped haircuts on the occipital scalp, which are particularly popular among men of African descent, increase the risk for AKN.5 Although this grooming style may be a personal preference, other hairstyles commonly worn by those with tightly coiled hair may be deemed “unprofessional” in society or the workplace,21 which leads to hairstyling practices that may increase the risk for AKN.

Acne keloidalis nuchae remains an understudied entity that adversely affects patients with skin of color.

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489. doi:10.2147/CCID.S99225

- Al Aboud DM, Badri T. Acne keloidalis nuchae. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459135/ 3.

- Sperling LC, Homoky C, Pratt L, et al. Acne keloidalis is a form of primary scarring alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:479-484.

- Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis: transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121. doi:10.1097/00000372-199004000-00001

- Saka B, Akakpo A-S, Téclessou JN, et al. Risk factors associated with acne keloidalis nuchae in black subjects: a case-control study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2020;147:350-354. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2020.01.007

- Umar S, Lee DJ, Lullo JJ. A retrospective cohort study and clinical classification system of acne keloidalis nuchae. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:E61-E67.

- Reja M, Silverberg NB. Acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Silverberg NB, Durán-McKinster C, Tay YK, eds. Pediatric Skin of Color. Springer; 2015:141-145. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6654-3_16 8.

- Knable AL Jr, Hanke CW, Gonin R. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in football players. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:570-574. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70173-7

- Umar S, Ton D, Carter MJ, et al. Unveiling a shared precursor condition for acne keloidalis nuchae and primary cicatricial alopecias. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:2315-2327. doi:10.2147/CCID.S422310

- Na K, Oh SH, Kim SK. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Asian: a single institutional experience. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189790. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189790

- Ogunbiyi A, George A. Acne keloidalis in females: case report and review of literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:736-738.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Kridin K, Solomon A, Tzur-Bitan D, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae and the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:733-739. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00541-z

- Smart K, Rodriguez I, Worswick S. Comorbidities and treatment options for acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Ther. Published online May 25, 2024. doi:10.1155/2024/8336926

- Callender VD, Young CM, Haverstock CL, et al. An open label study of clobetasol propionate 0.05% and betamethasone valerate 0.12% foams in the treatment of mild to moderate acne keloidalis. Cutis. 2005;75:317-321.

- Adotama P, Grullon K, Ali S, et al. How we do it: our method for triamcinolone injections of acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:713-714. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003803

- Beckett N, Lawson C, Cohen G. Electrosurgical excision of acne keloidalis nuchae with secondary intention healing. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:36-39.

- Esmat SM, Abdel Hay RM, Abu Zeid OM, et al. The efficacy of laser-assisted hair removal in the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae; a pilot study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:645-650. doi:10.1684/ejd.2012.1830

- Dillard AD, Quarles FN. African-American pioneers in dermatology. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:717-730.

- Umar S, David CV, Castillo JR, et al. Innovative surgical approaches and selection criteria of large acne keloidalis nuchae lesions. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:E2215. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002215

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

- Ogunbiyi A. Acne keloidalis nuchae: prevalence, impact, and management challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:483-489. doi:10.2147/CCID.S99225

- Al Aboud DM, Badri T. Acne keloidalis nuchae. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Updated July 31, 2023. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459135/ 3.

- Sperling LC, Homoky C, Pratt L, et al. Acne keloidalis is a form of primary scarring alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:479-484.

- Herzberg AJ, Dinehart SM, Kerns BJ, et al. Acne keloidalis: transverse microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and electron microscopy. Am J Dermatopathol. 1990;12:109-121. doi:10.1097/00000372-199004000-00001

- Saka B, Akakpo A-S, Téclessou JN, et al. Risk factors associated with acne keloidalis nuchae in black subjects: a case-control study. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2020;147:350-354. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2020.01.007

- Umar S, Lee DJ, Lullo JJ. A retrospective cohort study and clinical classification system of acne keloidalis nuchae. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2021;14:E61-E67.

- Reja M, Silverberg NB. Acne keloidalis nuchae. In: Silverberg NB, Durán-McKinster C, Tay YK, eds. Pediatric Skin of Color. Springer; 2015:141-145. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-6654-3_16 8.

- Knable AL Jr, Hanke CW, Gonin R. Prevalence of acne keloidalis nuchae in football players. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:570-574. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70173-7

- Umar S, Ton D, Carter MJ, et al. Unveiling a shared precursor condition for acne keloidalis nuchae and primary cicatricial alopecias. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2023;16:2315-2327. doi:10.2147/CCID.S422310

- Na K, Oh SH, Kim SK. Acne keloidalis nuchae in Asian: a single institutional experience. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189790. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189790

- Ogunbiyi A, George A. Acne keloidalis in females: case report and review of literature. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:736-738.

- Alexis A, Heath CR, Halder RM. Folliculitis keloidalis nuchae and pseudofolliculitis barbae: are prevention and effective treatment within reach? Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:183-191. doi:10.1016/j.det.2013.12.001

- Kridin K, Solomon A, Tzur-Bitan D, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae and the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:733-739. doi:10.1007/s40257-020-00541-z

- Smart K, Rodriguez I, Worswick S. Comorbidities and treatment options for acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Ther. Published online May 25, 2024. doi:10.1155/2024/8336926

- Callender VD, Young CM, Haverstock CL, et al. An open label study of clobetasol propionate 0.05% and betamethasone valerate 0.12% foams in the treatment of mild to moderate acne keloidalis. Cutis. 2005;75:317-321.

- Adotama P, Grullon K, Ali S, et al. How we do it: our method for triamcinolone injections of acne keloidalis nuchae. Dermatol Surg. 2023;49:713-714. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000003803

- Beckett N, Lawson C, Cohen G. Electrosurgical excision of acne keloidalis nuchae with secondary intention healing. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:36-39.

- Esmat SM, Abdel Hay RM, Abu Zeid OM, et al. The efficacy of laser-assisted hair removal in the treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae; a pilot study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:645-650. doi:10.1684/ejd.2012.1830

- Dillard AD, Quarles FN. African-American pioneers in dermatology. In: Taylor SC, Kelly AP, Lim HW, et al, eds. Dermatology for Skin of Color. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016:717-730.

- Umar S, David CV, Castillo JR, et al. Innovative surgical approaches and selection criteria of large acne keloidalis nuchae lesions. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:E2215. doi:10.1097/GOX.0000000000002215

- Lee MS, Nambudiri VE. The CROWN act and dermatology: taking a stand against race-based hair discrimination. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1181-1182. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.11.065

Benefits of High-Dose Vitamin D in Managing Cutaneous Adverse Events Induced by Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy

Vitamin D (VD) regulates keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation, modulates inflammatory pathways, and protects against cellular damage in the skin. 1 In the setting of tissue injury and acute skin inflammation, active vitamin D—1,25(OH) 2 D—suppresses signaling from pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines such as IFN- γ and IL-17. 2,3 This suppression reduces proliferation of helper T cells (T H 1, T H 17) and B cells, decreasing tissue damage from reactive oxygen species release while enhancing secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 by antigen-presenting cells. 2-4

Suboptimal VD levels have been associated with numerous health consequences including malignancy, prompting interest in VD supplementation for improving cancer-related outcomes.5 Beyond disease prognosis, high-dose VD supplementation has been suggested as a potential therapy for adverse events (AEs) related to cancer treatments. In one study, mice that received oral vitamin D3 supplementation of 11,500 IU/kg daily had fewer doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxic effects on ejection fraction (P<.0001) and stroke volume (P<.01) than mice that received VD supplementation of 1500 IU/kg daily.6

In this review, we examine the impact of chemoradiation on 25(OH)D levels—which more accurately reflects VD stores than 1,25(OH)2D levels—and the impact of suboptimal VD on cutaneous toxicities related to chemoradiation. To define the suboptimal VD threshold, we used the Endocrine Society’s clinical practice guidelines, which characterize suboptimal 25(OH)D levels as insufficiency (21–29 ng/mL [52.5–72.5 nmol/L]) or deficiency (<20 ng/mL [50 nmol/L])7; deficiency can be further categorized as severe deficiency (<12 ng/mL [30 nmol/L]).8 This review also evaluates the evidence for vitamin D3 supplementation to alleviate the cutaneous AEs of chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

Effects of Chemotherapy on Vitamin D Levels

A high prevalence of VD deficiency is seen in various cancers. In a retrospective review of 25(OH)D levels in 2098 adults with solid tumors of any stage (6% had metastatic disease [n=124]), suboptimal levels were found in 69% of patients with breast cancer (n=617), 75% with colorectal cancer (n=84), 72% with gynecologic cancer (n=65), 79% with kidney and bladder cancer (n=145), 83% with pancreatic and upper gastrointestinal tract cancer (n=178), 73% with lung cancer (n=73), 69% with prostate cancer (n=225), 61% with skin cancer (n=399), and 63% with thyroid cancer (n=172).5 Suboptimal VD also has been found in hematologic malignancies. In a prospective cohort study, mean serum 25(OH)D levels in 23 patients with recently diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia demonstrated VD deficiency (mean [SD], 18.6 [6.6] nmol/L).9 Given that many patients already exhibit a baseline VD deficiency at cancer diagnosis, it is important to understand the relationship between VD and cancer treatment modalities.5

In the United States, breast and colorectal cancers were estimated to be the first and fourth most common cancers, with 313,510 and 152,810 predicted new cases in 2024, respectively.10 This review will focus on breast and colorectal cancer when describing VD variation associated with chemotherapy exposure due to their high prevalence.

Effects of Chemotherapy on Vitamin D Levels in Breast Cancer—Breast cancer studies have shown suboptimal VD levels in 76% of females 75 years or younger with any T1, T2, or T3; N0 or N1; and M0 breast cancer, in which 38.5% (n=197) had insufficient and 37.5% (n=192) had deficient 25(OH)D levels.11 In a study of female patients with primary breast cancer (stage I, II, or III and T1 with high Ki67 expression [≥30%], T2, or T3), VD deficiency was seen in 60% of patients not receiving VD supplementation.12,13 A systematic review that included 7 studies of different types of breast cancer suggested that circulating 25(OH)D may be associated with improved prognosis.14 Thus, studies have investigated risk factors associated with poor or worsening VD status in individuals with breast cancer, including exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment.12,15-18

A prospective cohort study assessed 25(OH)D levels in 95 patients with any breast cancer (stages I, II, IIIA, IIIB) before and after initiating chemotherapy with docetaxel, doxorubicin, epirubicin, 5-fluorouracil, or cyclophosphamide, compared with a group of 52 females without cancer.17 In the breast cancer group, approximately 80% (76/95) had suboptimal and 50% (47/95) had deficient VD levels before chemotherapy initiation (mean [SD], 54.1 [22.8] nmol/L). In the comparison group, 60% (31/52) had suboptimal and 30% (15/52) had deficient VD at baseline (mean [SD], 66.1 [23.5] nmol/L), which was higher than the breast cancer group (P=.03). A subgroup analysis excluded participants who started, stopped, or lacked data on dietary supplements containing VD (n=39); in the remaining 56 participants, a significant decrease in 25(OH)D levels was observed shortly after finishing chemotherapy compared with the prechemotherapy baseline value (mean, −7.9 nmol/L; P=.004). Notably, 6 months after chemotherapy completion, 25(OH)D levels increased (mean, +12.8 nmol/L; P<.001). Vitamin D levels remained stable in the comparison group (P=.987).17

Consistent with these findings, a cross-sectional study assessing VD status in 394 female patients with primary breast cancer (stage I, II, or III and T1 with high Ki67 expression [≥30%], T2, or T3), found that a history of chemotherapy was associated with increased odds of 25(OH)D levels less than 20 ng/mL compared with breast cancer patients with no prior chemotherapy (odds ratio, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.03-3.38).12 Although the study data included chemotherapy history, no information was provided on specific chemotherapy agents or regimens used in this cohort, limiting the ability to detect the drugs most often implicated.

Both studies indicated a complex interplay between chemotherapy and VD levels in breast cancer patients. Although Kok et al17 suggested a transient decrease in VD levels during chemotherapy with a subsequent recovery after cessation, Fassio et al12 highlighted the increased odds of VD deficiency associated with chemotherapy. Ultimately, larger randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the relationship between chemotherapy and VD status in breast cancer patients.

Effects of Chemotherapy on Vitamin D Levels in Colorectal Cancer—Similar to patterns seen in breast cancer, a systematic review with 6 studies of different types of colorectal cancer suggested that circulating 25(OH)D levels may be associated with prognosis.14 Studies also have investigated the relationship between colorectal chemotherapy regimens and VD status.15,16,18,19

A retrospective study assessed 25(OH)D levels in 315 patients with any colorectal cancer (stage I–IV).15 Patients were included in the analysis if they received less than 400 IU daily of VD supplementation at baseline. For the whole study sample, the mean (SD) VD level was 23.7 (13.71) ng/mL. Patients who had not received chemotherapy within 3 months of the VD level assessment were categorized as the no chemotherapy group, and the others were designated as the chemotherapy group; the latter group was exposed to various chemotherapy regimens, including combinations of irinotecan, oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, bevacizumab, or cetuximab. Multivariate analysis showed that the chemotherapy group was 3.7 times more likely to have very low VD levels (≤15 ng/mL) compared with those in the no chemotherapy group (P<.0001).15

A separate cross-sectional study examined serum 25(OH)D concentrations in 1201 patients with any newly diagnosed colorectal carcinoma (stage I–III); 91% of cases were adenocarcinoma.18 In a multivariate analysis, chemotherapy plus surgery was associated with lower VD levels than surgery alone 6 months after diagnosis (mean, −8.74 nmol/L; 95% CI, −11.30 to −6.18 nmol/L), specifically decreasing by a mean of 6.7 nmol/L (95% CI, −9.8 to −3.8 nmol/L) after adjusting for demographic and lifestyle factors.18 However, a prospective cohort study demonstrated different findings.19 Comparing 58 patients with newly diagnosed colorectal adenocarcinoma (stages I–IV) who underwent chemotherapy and 36 patients who did not receive chemotherapy, there was no significant change in 25(OH)D levels from the time of diagnosis to 6 months later. Median VD levels decreased by 0.7 ng/mL in those who received chemotherapy, while a minimal (and not significant) increase of 1.6 ng/mL was observed in those without chemotherapy intervention (P=.26). Notably, supplementation was not restricted in this cohort, which may have resulted in higher VD levels in those taking supplements.19

Since time of year and geographic location can influence VD levels, one prospective cohort study controlled for differential sun exposure due to these factors in their analysis.16 Assessment of 25(OH)D levels was completed in 81 chemotherapy-naïve cancer patients immediately before beginning chemotherapy as well as 6 and 12 weeks into treatment. More than 8 primary cancer types were represented in this study, with breast (34% [29/81]) and colorectal (14% [12/81]) cancer being the most common, but the cancer stages of the participants were not detailed. Vitamin D levels decreased after commencing chemotherapy, with the largest drop occurring 6 weeks into treatment. From the 6- to 12-week end points, VD increased but remained below the original baseline level (baseline: mean [SD], 49.2 [22.3] nmol/L; 6 weeks: mean [SD], 40.9 [19.0] nmol/L; 12 weeks: mean [SD], 45.9 [19.7] nmol/L; P=.05).16

Although focused on breast and colorectal cancers, these studies suggest that various chemotherapy regimens may confer a higher risk for VD deficiency compared with VD status at diagnosis and/or prior to chemotherapy treatment. However, most of these studies only discussed stage-based differences, excluding analysis of the variety of cancer subtypes that comprise breast and colorectal malignancies, which may limit our ability to extrapolate from these data. Ultimately, larger randomized controlled trials are needed to better understand the relationship between chemotherapy and VD status across various primary cancer types.

Effects of Radiation Therapy on Vitamin D Levels

Unlike chemotherapy, studies on the association between radiation therapy and VD levels are minimal, with most reports in the literature discussing the use of VD to potentiate the effects of radiation therapy. In one cross-sectional analysis of 1201 patients with newly diagnosed stage I, II, or III colorectal cancer of any type (94% were adenocarcinoma), radiation plus surgery was associated with slightly lower 25(OH)D levels than surgery alone for tumor treatment 6 months after diagnosis (mean, −3.17; 95% CI, −6.07 to −0.28 nmol/L). However, after adjustment for demographic and lifestyle factors, this decrease in VD levels attributable to radiotherapy was not statistically significant compared with the surgery-only cohort (mean, −1.78; 95% CI, −5.07 to 1.52 nmol/L).18

Similarly, a cross-sectional study assessing VD status in 394 female patients with primary breast cancer (stage I, II, or III and T1 with high Ki67 expression [≥30%], T2, or T3), found that a history of radiotherapy was not associated with a difference in serum 25(OH)D levels compared with those with breast cancer without prior radiotherapy (odds ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.52-1.54).12 From the limited existing literature specifically addressing variations of VD levels with radiation, radiation therapy does not appear to significantly impact VD levels.

Vitamin D Levels and the Severity of Chemotherapy- or Radiation Therapy–Induced AEs

A prospective cohort of 241 patients did not find an increase in the incidence or severity of chemotherapy-induced cutaneous toxicities in those with suboptimal 1,25(OH)2D3 levels (≤75 nmol/L).20 Eight different primary cancer types were represented, including breast and colorectal cancer; the tumor stages of the participants were not detailed. Forty-one patients had normal 1,25(OH)2D3 levels, while the remaining 200 had suboptimal levels. There was no significant association between serum VD levels and the following dermatologic toxicities: desquamation (P=.26), xerosis (P=.15), mucositis (P=.30), or painful rash (P=.87). Surprisingly, nail changes and hand-foot reactions occurred with greater frequency in patients with normal VD levels (P=.01 and P=.03, respectively).20 Hand-foot reaction is part of the toxic erythema of chemotherapy (TEC) spectrum, which is comprised of a range of cytotoxic skin injuries that typically manifest within 2 to 3 weeks of exposure to the offending chemotherapeutic agents, often characterized by erythema, pain, swelling, and blistering, particularly in intertriginous and acral areas.21-23 Recovery from TEC generally takes at least 2 to 4 weeks and may necessitate cessation of the offending chemotherapeutic agent.21,24 Notably, this study measured 1,25(OH)2D3 levels instead of 25(OH)D levels, which may not reliably indicate body stores of VD.7,20 These results underscore the complex nature between chemotherapy and VD; however, VD levels alone do not appear to be a sufficient biomarker for predicting chemotherapy-associated cutaneous AEs.

Interestingly, radiation therapy–induced AEs may be associated with VD levels. A prospective cohort study of 98 patients with prostate, bladder, or gynecologic cancers (tumor stages were not detailed) undergoing pelvic radiotherapy found that females and males with 25(OH)D levels below a threshold of 35 and 40 nmol/L, respectively, were more likely to experience higher Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) grade acute proctitis compared with those with VD above these thresholds.25 Specifically, VD below these thresholds was associated with increased odds of RTOG grade 2 or higher radiation-induced proctitis (OR, 3.07; 95% CI, 1.27-7.50 [P=.013]). Additionally, a weak correlation was noted between VD below these thresholds and the RTOG grade, with a Spearman correlation value of −0.189 (P=.031).25

One prospective cohort study included 28 patients with any cancer of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, or larynx stages II, III, or IVA; 93% (26/28) were stage III or IVA.26 The 20 (71%) patients with suboptimal 25(OH)D levels (≤75 nmol/L) experienced a higher prevalence of grade II radiation dermatitis compared with the 8 (29%) patients with optimal VD levels (χ22 =5.973; P=.0505). This pattern persisted with the severity of mucositis; patients from the suboptimal VD group presented with higher rates of grades II and III mucositis compared with the VD optimal group (χ22 =13.627; P=.0011).26 Recognizing the small cohort evaluated in the study, we highlight the importance of further studies to clarify these associations.

Chemotherapy-Induced Cutaneous Events Treated with High-Dose Vitamin D

Chemotherapeutic agents are known to induce cellular damage, resulting in a range of cutaneous AEs that can invoke discontinuation of otherwise effective chemotherapeutic interventions.27,28 Recent research has explored the potential of high-dose vitamin D3 as a therapeutic agent to mitigate cutaneous reactions.29,30

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial investigated the use of a single high dose of oral 25(OH)D to treat topical nitrogen mustard (NM)–induced rash.29 To characterize baseline inflammatory responses from NM injury without intervention, clinical measures, serum studies, and tissue analyses from skin biopsies were performed on 28 healthy adults after exposure to topical NM—a chemotherapeutic agent classified as a DNA alkylator. Two weeks later, participants were exposed to topical NM a second time and were split into 2 groups: 14 patients received a single 200,000-IU dose of oral 25(OH)D while the other 14 participants were given a placebo. Using the inflammatory markers induced from baseline exposure to NM alone, posttreatment analysis revealed that the punch biopsies from

Although Ernst et al29 did not observe any clinically significant improvements with VD treatment, a case series of 6 patients with either glioblastoma multiforme, acute myeloid leukemia, or aplastic anemia did demonstrate clinical improvement of TEC after receiving high-dose vitamin D3.30 The mean time to onset of TEC was noted at 8.5 days following administration of the inciting chemotherapeutic agent, which included combinations of anthracycline, antimetabolite, kinase inhibitor, B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, purine analogue, and alkylating agents. A combination of clinical and histologic findings was used to diagnose TEC. Baseline 25(OH)D levels were not established prior to treatment. The treatment regimen for 1 patient included 2 doses of 50,000 IU of VD spaced 1 week apart, totaling 100,000 IU, while the remaining 5 patients received a total of 200,000 IU, also split into 2 doses given 1 week apart. All patients received their first dose of VD within a week of the cutaneous eruption. Following the initial VD dose, there was a notable improvement in pain, pruritus, or swelling by the next day. Reduction in erythema also was observed within 1 to 4 days.30

No AEs associated with VD supplementation were reported, suggesting a potential beneficial role of high-dose VD in accelerating recovery from chemotherapy-induced rashes without evident safety concerns.

Radiation Therapy–Induced Cutaneous Events Treated with High-Dose Vitamin D

Radiation dermatitis is a common and often severe complication of radiation therapy that affects more than 90% of patients undergoing treatment, with half of these individuals experiencing grade 2 toxicity, according to the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.31,32 Radiation damage to basal keratinocytes and hair follicle stem cells disrupts the renewal of the skin’s outer layer, while a surge of free radicals causes irreversible DNA damage.33 Symptoms of radiation dermatitis can vary from mild pink erythema to tissue ulceration and necrosis, typically within 1 to 4 weeks of radiation exposure.34 The resulting dermatitis can take 2 to 4 weeks to heal, notably impacting patient quality of life and often necessitating modifications or interruptions in cancer therapy.33

Prior studies have demonstrated the use of high-dose VD to improve the healing of UV-irradiated skin. A randomized controlled trial investigated high-dose vitamin D3 to treat experimentally induced sunburn in 20 healthy adults. Compared with those who received a placebo, participants receiving the oral dose of 200,000 IU of vitamin D3 demonstrated suppression of the pro-inflammatory mediators tumor necrosis factor α (P=.04) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (P=.02), while expression of tissue repair enhancer arginase 1 was increased (P<.005).35 The mechanism of this enhanced tissue repair was investigated using a mouse model, in which intraperitoneal 25(OH)D was administered following severe UV-induced skin injury. On immunofluorescence microscopy, mice treated with VD showed enhanced autophagy within the macrophages infiltrating UV-irradiated skin.36 The use of high-dose VD to treat UV-irradiated skin in these studies established a precedent for using VD to heal cutaneous injury caused by ionizing radiation therapy.

Some studies have focused on the role of VD for treating acute radiation dermatitis. A study of 23 patients with ductal carcinoma in situ or localized invasive ductal carcinoma breast cancer compared the effectiveness of topical calcipotriol to that of a standard hydrating ointment.37 Participants were randomized to 1 of 2 treatments before starting adjuvant radiotherapy to evaluate their potential in preventing radiation dermatitis. In 87% (20/23) of these patients, no difference in skin reaction was observed between the 2 treatments, suggesting that topical VD application may not offer any advantage over the standard hydrating ointment for the prevention of radiation dermatitis.37

Benefits of high-dose oral VD for treating radiation dermatitis also have been reported. Nguyen et al38 documented 3 cases in which patients with neuroendocrine carcinoma of the pancreas, tonsillar carcinoma, and breast cancer received 200,000 IU of oral ergocalciferol distributed over 2 doses given 7 days apart for radiation dermatitis. These patients experienced substantial improvements in pain, swelling, and redness within a week of the initial dose. Additionally, a case of radiation recall dermatitis, which occurred a week after vinorelbine chemotherapy, was treated with 2 doses totaling 100,000 IU of oral ergocalciferol. This patient also had improvement in pain and swelling but continued to have tumor-related induration and ulceration.39

Although topical VD did not show significant benefits over standard treatments for radiation dermatitis, high-dose oral VD appears promising in improving patient outcomes of pain and swelling more rapidly than current practices. Further research is needed to confirm these findings and establish standardized treatment protocols.

Final Thoughts