User login

Formerly Skin & Allergy News

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')]

The leading independent newspaper covering dermatology news and commentary.

TNF inhibitors may dampen COVID-19 severity

Patients on a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for their rheumatic disease when they became infected with COVID-19 were markedly less likely to subsequently require hospitalization, according to intriguing early evidence from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Registry.

On the other hand, those registry patients who were on 10 mg of prednisone or more daily when they got infected were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized than were those who were not on corticosteroids, even after controlling for the severity of their rheumatic disease and other potential confounders, Jinoos Yazdany, MD, reported at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

“We saw a signal with moderate to high-dose steroids. I think it’s something we’re going to have to keep an eye out on as more data come in,” said Dr. Yazdany, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of rheumatology at San Francisco General Hospital.

The global registry launched on March 24, 2020, and was quickly embraced by rheumatologists from around the world. By May 12, the registry included more than 1,300 patients with a range of rheumatic diseases, all with confirmed COVID-19 infection as a requisite for enrollment; the cases were submitted by more than 300 rheumatologists in 40 countries. The registry is supported by the ACR and European League Against Rheumatism.

Dr. Yazdany, a member of the registry steering committee, described the project’s two main goals: To learn the outcomes of COVID-19–infected patients with various rheumatic diseases and to make inferences regarding the impact of the immunosuppressive and antimalarial medications widely prescribed by rheumatologists.

She presented soon-to-be-published data on the characteristics and disposition of the first 600 patients, 46% of whom were hospitalized and 9% died. A caveat regarding the registry, she noted, is that these are observational data and thus potentially subject to unrecognized confounders. Also, the registry population is skewed toward the sicker end of the COVID-19 disease spectrum because while all participants have confirmed infection, testing for the infection has been notoriously uneven. Many people are infected asymptomatically and thus may not undergo testing even where readily available.

Early key findings from registry

The risk factors for more severe infection resulting in hospitalization in patients with rheumatic diseases are by and large the same drivers described in the general population: older age and comorbid conditions including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, chronic kidney disease, and lung disease. Notably, however, patients on the equivalent of 10 mg/day of prednisone or more were at a 105% increased risk for hospitalization, compared with those not on corticosteroids after adjustment for age, comorbid conditions, and rheumatic disease severity.

Patients on a background tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor had an adjusted 60% reduction in risk of hospitalization. This apparent protective effect against more severe COVID-19 disease is mechanistically plausible: In animal studies, being on a TNF inhibitor has been associated with less severe infection following exposure to influenza virus, Dr. Yazdany observed.

COVID-infected patients on any biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug had a 54% decreased risk of hospitalization. However, in this early analysis, the study was sufficiently powered only to specifically assess the impact of TNF inhibitors, since those agents were by far the most commonly used biologics. As the registry grows, it will be possible to analyze the impact of other antirheumatic medications.

Being on hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials at the time of COVID-19 infection had no impact on hospitalization.

The only rheumatic disease diagnosis with an odds of hospitalization significantly different from that of RA patients was systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Lupus patients were at 80% increased risk of hospitalization. Although this was a statistically significant difference, Dr. Yazdany cautioned against making too much of it because of the strong potential for unmeasured confounding. In particular, lupus patients as a group are known to rate on the lower end of measures of social determinants of health, a status that is an established major risk factor for COVID-19 disease.

“A strength of the global registry has been that it provides timely data that’s been very helpful for rheumatologists to rapidly dispel misinformation that has been spread about hydroxychloroquine, especially statements about lupus patients not getting COVID-19. We know from these data that’s not true,” she said.

Being on background NSAIDs at the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with increased risk of hospitalization; in fact, NSAID users were 36% less likely to be hospitalized for their COVID-19 disease, although this difference didn’t reach statistical significance.

Dr. Yazdany urged her fellow rheumatologists to enter their cases on the registry website: rheum-covid.org. There they can also join the registry mailing list and receive weekly updates.

Other recent insights on COVID-19 in rheumatology

An as-yet unpublished U.K. observational study involving electronic health record data on 17 million people included 885,000 individuals with RA, SLE, or psoriasis. After extensive statistical controlling for the known risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection, including a measure of socioeconomic deprivation, the group with one of these autoimmune diseases had an adjusted, statistically significant 23% increased risk of hospital death because of COVID-19 infection.

“This is the largest study of its kind to date. There’s potential for unmeasured confounding and selection bias here due to who gets tested. We’ll have to see where this study lands, but I think it does suggest there’s a slightly higher mortality risk in COVID-infected patients with rheumatic disease,” according to Dr. Yazdany.

On the other hand, there have been at least eight recently published patient surveys and case series of patients with rheumatic diseases in areas of the world hardest hit by the pandemic, and they paint a consistent picture.

“What we’ve learned from these studies was the infection rate was generally in the ballpark of people in the region. It doesn’t seem like there’s a dramatically higher infection rate in people with rheumatic disease in these surveys. The hospitalized rheumatology patients had many of the familiar comorbidities. This is the first glance at how likely people are to become infected and how they fared, and I think overall the data have been quite reassuring,” she said.

Dr. Yazdany reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly and receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients on a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for their rheumatic disease when they became infected with COVID-19 were markedly less likely to subsequently require hospitalization, according to intriguing early evidence from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Registry.

On the other hand, those registry patients who were on 10 mg of prednisone or more daily when they got infected were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized than were those who were not on corticosteroids, even after controlling for the severity of their rheumatic disease and other potential confounders, Jinoos Yazdany, MD, reported at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

“We saw a signal with moderate to high-dose steroids. I think it’s something we’re going to have to keep an eye out on as more data come in,” said Dr. Yazdany, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of rheumatology at San Francisco General Hospital.

The global registry launched on March 24, 2020, and was quickly embraced by rheumatologists from around the world. By May 12, the registry included more than 1,300 patients with a range of rheumatic diseases, all with confirmed COVID-19 infection as a requisite for enrollment; the cases were submitted by more than 300 rheumatologists in 40 countries. The registry is supported by the ACR and European League Against Rheumatism.

Dr. Yazdany, a member of the registry steering committee, described the project’s two main goals: To learn the outcomes of COVID-19–infected patients with various rheumatic diseases and to make inferences regarding the impact of the immunosuppressive and antimalarial medications widely prescribed by rheumatologists.

She presented soon-to-be-published data on the characteristics and disposition of the first 600 patients, 46% of whom were hospitalized and 9% died. A caveat regarding the registry, she noted, is that these are observational data and thus potentially subject to unrecognized confounders. Also, the registry population is skewed toward the sicker end of the COVID-19 disease spectrum because while all participants have confirmed infection, testing for the infection has been notoriously uneven. Many people are infected asymptomatically and thus may not undergo testing even where readily available.

Early key findings from registry

The risk factors for more severe infection resulting in hospitalization in patients with rheumatic diseases are by and large the same drivers described in the general population: older age and comorbid conditions including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, chronic kidney disease, and lung disease. Notably, however, patients on the equivalent of 10 mg/day of prednisone or more were at a 105% increased risk for hospitalization, compared with those not on corticosteroids after adjustment for age, comorbid conditions, and rheumatic disease severity.

Patients on a background tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor had an adjusted 60% reduction in risk of hospitalization. This apparent protective effect against more severe COVID-19 disease is mechanistically plausible: In animal studies, being on a TNF inhibitor has been associated with less severe infection following exposure to influenza virus, Dr. Yazdany observed.

COVID-infected patients on any biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug had a 54% decreased risk of hospitalization. However, in this early analysis, the study was sufficiently powered only to specifically assess the impact of TNF inhibitors, since those agents were by far the most commonly used biologics. As the registry grows, it will be possible to analyze the impact of other antirheumatic medications.

Being on hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials at the time of COVID-19 infection had no impact on hospitalization.

The only rheumatic disease diagnosis with an odds of hospitalization significantly different from that of RA patients was systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Lupus patients were at 80% increased risk of hospitalization. Although this was a statistically significant difference, Dr. Yazdany cautioned against making too much of it because of the strong potential for unmeasured confounding. In particular, lupus patients as a group are known to rate on the lower end of measures of social determinants of health, a status that is an established major risk factor for COVID-19 disease.

“A strength of the global registry has been that it provides timely data that’s been very helpful for rheumatologists to rapidly dispel misinformation that has been spread about hydroxychloroquine, especially statements about lupus patients not getting COVID-19. We know from these data that’s not true,” she said.

Being on background NSAIDs at the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with increased risk of hospitalization; in fact, NSAID users were 36% less likely to be hospitalized for their COVID-19 disease, although this difference didn’t reach statistical significance.

Dr. Yazdany urged her fellow rheumatologists to enter their cases on the registry website: rheum-covid.org. There they can also join the registry mailing list and receive weekly updates.

Other recent insights on COVID-19 in rheumatology

An as-yet unpublished U.K. observational study involving electronic health record data on 17 million people included 885,000 individuals with RA, SLE, or psoriasis. After extensive statistical controlling for the known risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection, including a measure of socioeconomic deprivation, the group with one of these autoimmune diseases had an adjusted, statistically significant 23% increased risk of hospital death because of COVID-19 infection.

“This is the largest study of its kind to date. There’s potential for unmeasured confounding and selection bias here due to who gets tested. We’ll have to see where this study lands, but I think it does suggest there’s a slightly higher mortality risk in COVID-infected patients with rheumatic disease,” according to Dr. Yazdany.

On the other hand, there have been at least eight recently published patient surveys and case series of patients with rheumatic diseases in areas of the world hardest hit by the pandemic, and they paint a consistent picture.

“What we’ve learned from these studies was the infection rate was generally in the ballpark of people in the region. It doesn’t seem like there’s a dramatically higher infection rate in people with rheumatic disease in these surveys. The hospitalized rheumatology patients had many of the familiar comorbidities. This is the first glance at how likely people are to become infected and how they fared, and I think overall the data have been quite reassuring,” she said.

Dr. Yazdany reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly and receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Patients on a tumor necrosis factor inhibitor for their rheumatic disease when they became infected with COVID-19 were markedly less likely to subsequently require hospitalization, according to intriguing early evidence from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance Registry.

On the other hand, those registry patients who were on 10 mg of prednisone or more daily when they got infected were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized than were those who were not on corticosteroids, even after controlling for the severity of their rheumatic disease and other potential confounders, Jinoos Yazdany, MD, reported at the virtual edition of the American College of Rheumatology’s 2020 State-of-the-Art Clinical Symposium.

“We saw a signal with moderate to high-dose steroids. I think it’s something we’re going to have to keep an eye out on as more data come in,” said Dr. Yazdany, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and chief of rheumatology at San Francisco General Hospital.

The global registry launched on March 24, 2020, and was quickly embraced by rheumatologists from around the world. By May 12, the registry included more than 1,300 patients with a range of rheumatic diseases, all with confirmed COVID-19 infection as a requisite for enrollment; the cases were submitted by more than 300 rheumatologists in 40 countries. The registry is supported by the ACR and European League Against Rheumatism.

Dr. Yazdany, a member of the registry steering committee, described the project’s two main goals: To learn the outcomes of COVID-19–infected patients with various rheumatic diseases and to make inferences regarding the impact of the immunosuppressive and antimalarial medications widely prescribed by rheumatologists.

She presented soon-to-be-published data on the characteristics and disposition of the first 600 patients, 46% of whom were hospitalized and 9% died. A caveat regarding the registry, she noted, is that these are observational data and thus potentially subject to unrecognized confounders. Also, the registry population is skewed toward the sicker end of the COVID-19 disease spectrum because while all participants have confirmed infection, testing for the infection has been notoriously uneven. Many people are infected asymptomatically and thus may not undergo testing even where readily available.

Early key findings from registry

The risk factors for more severe infection resulting in hospitalization in patients with rheumatic diseases are by and large the same drivers described in the general population: older age and comorbid conditions including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, obesity, chronic kidney disease, and lung disease. Notably, however, patients on the equivalent of 10 mg/day of prednisone or more were at a 105% increased risk for hospitalization, compared with those not on corticosteroids after adjustment for age, comorbid conditions, and rheumatic disease severity.

Patients on a background tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor had an adjusted 60% reduction in risk of hospitalization. This apparent protective effect against more severe COVID-19 disease is mechanistically plausible: In animal studies, being on a TNF inhibitor has been associated with less severe infection following exposure to influenza virus, Dr. Yazdany observed.

COVID-infected patients on any biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug had a 54% decreased risk of hospitalization. However, in this early analysis, the study was sufficiently powered only to specifically assess the impact of TNF inhibitors, since those agents were by far the most commonly used biologics. As the registry grows, it will be possible to analyze the impact of other antirheumatic medications.

Being on hydroxychloroquine or other antimalarials at the time of COVID-19 infection had no impact on hospitalization.

The only rheumatic disease diagnosis with an odds of hospitalization significantly different from that of RA patients was systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Lupus patients were at 80% increased risk of hospitalization. Although this was a statistically significant difference, Dr. Yazdany cautioned against making too much of it because of the strong potential for unmeasured confounding. In particular, lupus patients as a group are known to rate on the lower end of measures of social determinants of health, a status that is an established major risk factor for COVID-19 disease.

“A strength of the global registry has been that it provides timely data that’s been very helpful for rheumatologists to rapidly dispel misinformation that has been spread about hydroxychloroquine, especially statements about lupus patients not getting COVID-19. We know from these data that’s not true,” she said.

Being on background NSAIDs at the time of SARS-CoV-2 infection was not associated with increased risk of hospitalization; in fact, NSAID users were 36% less likely to be hospitalized for their COVID-19 disease, although this difference didn’t reach statistical significance.

Dr. Yazdany urged her fellow rheumatologists to enter their cases on the registry website: rheum-covid.org. There they can also join the registry mailing list and receive weekly updates.

Other recent insights on COVID-19 in rheumatology

An as-yet unpublished U.K. observational study involving electronic health record data on 17 million people included 885,000 individuals with RA, SLE, or psoriasis. After extensive statistical controlling for the known risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection, including a measure of socioeconomic deprivation, the group with one of these autoimmune diseases had an adjusted, statistically significant 23% increased risk of hospital death because of COVID-19 infection.

“This is the largest study of its kind to date. There’s potential for unmeasured confounding and selection bias here due to who gets tested. We’ll have to see where this study lands, but I think it does suggest there’s a slightly higher mortality risk in COVID-infected patients with rheumatic disease,” according to Dr. Yazdany.

On the other hand, there have been at least eight recently published patient surveys and case series of patients with rheumatic diseases in areas of the world hardest hit by the pandemic, and they paint a consistent picture.

“What we’ve learned from these studies was the infection rate was generally in the ballpark of people in the region. It doesn’t seem like there’s a dramatically higher infection rate in people with rheumatic disease in these surveys. The hospitalized rheumatology patients had many of the familiar comorbidities. This is the first glance at how likely people are to become infected and how they fared, and I think overall the data have been quite reassuring,” she said.

Dr. Yazdany reported serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca and Eli Lilly and receiving research funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REPORTING FROM SOTA 2020

Antibody testing suggests COVID-19 cases are being missed

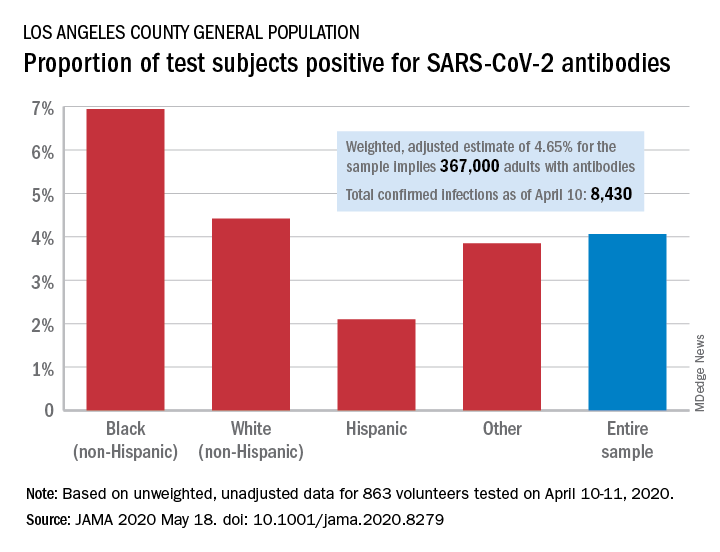

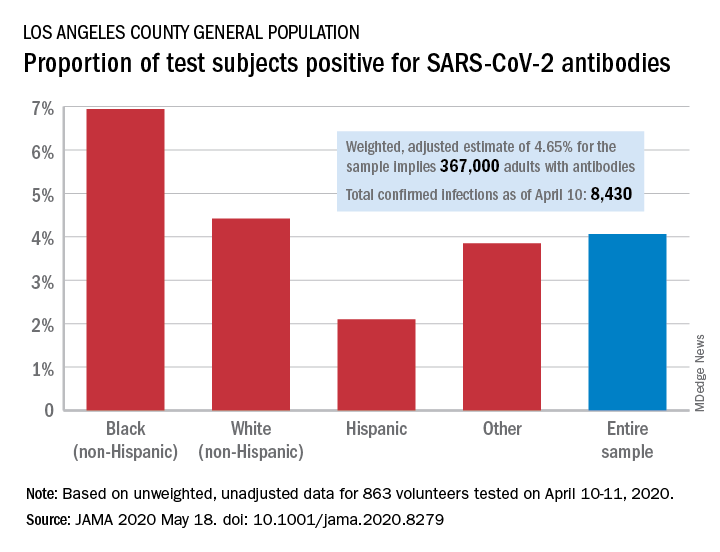

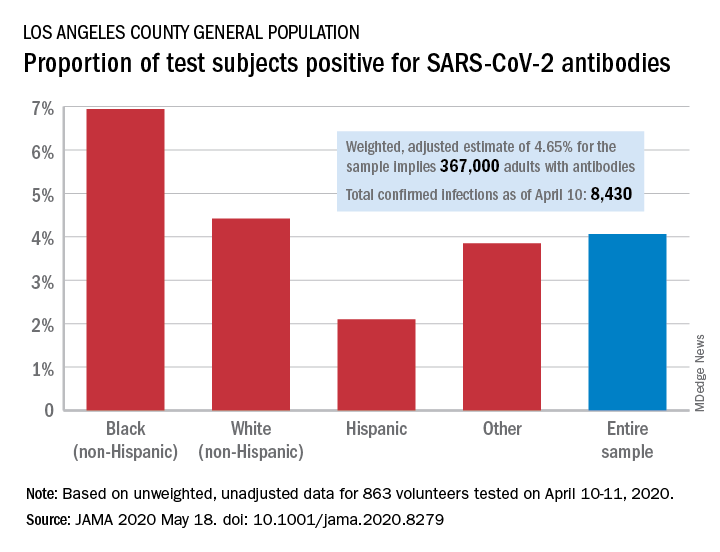

The number of COVID-19 infections in the community may be “substantially greater” than totals confirmed by authorities, based on SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing among a random sample of adults in Los Angeles County, Calif.

Testing of 863 people on April 10-11 revealed that 35 (4.06%) were positive for SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies (IgM or IgG), and after adjustment for test sensitivity and specificity, the weighted prevalence for the entire sample was 4.65%, Neeraj Sood, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

The estimate of 4.65% “implies that approximately 367,000 adults [in Los Angeles County] had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which is substantially greater than the 8,430 cumulative number of confirmed infections in the county on April 10,” they wrote.

It also suggests that fatality rates based on the larger number of infections may be lower than rates based on confirmed cases. “In addition, contact tracing methods to limit the spread of infection will face considerable challenges,” Dr. Sood and associates said.

Test positivity varied by race/ethnicity, sex, and income. The proportion of non-Hispanic blacks with a positive result was 6.94%, compared with 4.42% for non-Hispanic whites, 2.10% for Hispanics, and 3.85% for others. Men were much more likely than women to be positive for SARS-CoV-2: 5.18% vs. 3.31%, the investigators said.

Household income favored the middle ground. Those individuals making less than $50,000 a year had a positivity rate of 5.14% and those with an income of $100,000 or more had a rate of 4.90%, but only 1.58% of those making $50,000-$99,999 tested positive, they reported.

The authors reported numerous sources of nonprofit organization support.

SOURCE: Sood N et al. JAMA 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8279.

The number of COVID-19 infections in the community may be “substantially greater” than totals confirmed by authorities, based on SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing among a random sample of adults in Los Angeles County, Calif.

Testing of 863 people on April 10-11 revealed that 35 (4.06%) were positive for SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies (IgM or IgG), and after adjustment for test sensitivity and specificity, the weighted prevalence for the entire sample was 4.65%, Neeraj Sood, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

The estimate of 4.65% “implies that approximately 367,000 adults [in Los Angeles County] had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which is substantially greater than the 8,430 cumulative number of confirmed infections in the county on April 10,” they wrote.

It also suggests that fatality rates based on the larger number of infections may be lower than rates based on confirmed cases. “In addition, contact tracing methods to limit the spread of infection will face considerable challenges,” Dr. Sood and associates said.

Test positivity varied by race/ethnicity, sex, and income. The proportion of non-Hispanic blacks with a positive result was 6.94%, compared with 4.42% for non-Hispanic whites, 2.10% for Hispanics, and 3.85% for others. Men were much more likely than women to be positive for SARS-CoV-2: 5.18% vs. 3.31%, the investigators said.

Household income favored the middle ground. Those individuals making less than $50,000 a year had a positivity rate of 5.14% and those with an income of $100,000 or more had a rate of 4.90%, but only 1.58% of those making $50,000-$99,999 tested positive, they reported.

The authors reported numerous sources of nonprofit organization support.

SOURCE: Sood N et al. JAMA 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8279.

The number of COVID-19 infections in the community may be “substantially greater” than totals confirmed by authorities, based on SARS-CoV-2 antibody testing among a random sample of adults in Los Angeles County, Calif.

Testing of 863 people on April 10-11 revealed that 35 (4.06%) were positive for SARS-CoV-2–specific antibodies (IgM or IgG), and after adjustment for test sensitivity and specificity, the weighted prevalence for the entire sample was 4.65%, Neeraj Sood, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

The estimate of 4.65% “implies that approximately 367,000 adults [in Los Angeles County] had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which is substantially greater than the 8,430 cumulative number of confirmed infections in the county on April 10,” they wrote.

It also suggests that fatality rates based on the larger number of infections may be lower than rates based on confirmed cases. “In addition, contact tracing methods to limit the spread of infection will face considerable challenges,” Dr. Sood and associates said.

Test positivity varied by race/ethnicity, sex, and income. The proportion of non-Hispanic blacks with a positive result was 6.94%, compared with 4.42% for non-Hispanic whites, 2.10% for Hispanics, and 3.85% for others. Men were much more likely than women to be positive for SARS-CoV-2: 5.18% vs. 3.31%, the investigators said.

Household income favored the middle ground. Those individuals making less than $50,000 a year had a positivity rate of 5.14% and those with an income of $100,000 or more had a rate of 4.90%, but only 1.58% of those making $50,000-$99,999 tested positive, they reported.

The authors reported numerous sources of nonprofit organization support.

SOURCE: Sood N et al. JAMA 2020 May 18. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8279.

FROM JAMA

COVID-19 in kids: Severe illness most common in infants, teens

Children and young adults in all age groups can develop severe illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the oldest and youngest appear most likely to be hospitalized and possibly critically ill, based on data from a retrospective cohort study of 177 pediatric patients seen at a single center.

“Although children and young adults clearly are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, attention has focused primarily on their potential role in influencing spread and community transmission rather than the potential severity of infection in children and young adults themselves,” wrote Roberta L. DeBiasi, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 44 hospitalized and 133 non-hospitalized children and young adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of the 44 hospitalized patients, 35 were noncritically ill and 9 were critically ill. The study population ranged from 0.1-34 years of age, with a median of 10 years, which was similar between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. However, the median age of critically ill patients was significantly higher, compared with noncritically ill patients (17 years vs. 4 years). All age groups were represented in all cohorts. “However, we noted a bimodal distribution of patients less than 1 year of age and patients greater than 15 years of age representing the largest proportion of patients within the SARS-CoV-2–infected hospitalized and critically ill cohorts,” the researchers noted. Children less than 1 year and adolescents/young adults over 15 years each represented 32% of the 44 hospitalized patients.

Overall, 39% of the 177 patients had underlying medical conditions, the most frequent of which was asthma (20%), which was not significantly more common between hospitalized/nonhospitalized patients or critically ill/noncritically ill patients. Patients also presented with neurologic conditions (6%), diabetes (3%), obesity (2%), cardiac conditions (3%), hematologic conditions (3%) and oncologic conditions (1%). Underlying conditions occurred more commonly in the hospitalized cohort (63%) than in the nonhospitalized cohort (32%).

Neurologic disorders, cardiac conditions, hematologic conditions, and oncologic conditions were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, but not significantly more common among those critically ill versus noncritically ill.

About 76% of the patients presented with respiratory symptoms including rhinorrhea, congestion, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath – with or without fever; 66% had fevers; and 48% had both respiratory symptoms and fever. Shortness of breath was significantly more common among hospitalized patients versus nonhospitalized patients (26% vs. 12%), but less severe respiratory symptoms were significantly more common among nonhospitalized patients, the researchers noted.

Other symptoms – such as diarrhea, vomiting, chest pain, and loss of sense or smell occurred in a small percentage of patients – but were not more likely to occur in any of the cohorts.

Among the critically ill patients, eight of nine needed some level of respiratory support, and four were on ventilators.

“One patient had features consistent with the recently emerged Kawasaki disease–like presentation with hyperinflammatory state, hypotension, and profound myocardial depression,” Dr. DiBiasi and associates noted.

The researchers found coinfection with routine coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or rhinovirus/enterovirus in 4 of 63 (6%) patients, but the clinical impact of these coinfections are unclear.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the ongoing transmission of COVID-19 in the Washington area, the researchers noted. “One potential bias of this study is our regional role in providing critical care for young adults age 21-35 years with COVID-19.” In addition, “we plan to address the role of race and ethnicity after validation of current administrative data and have elected to defer this analysis until completed.”

“Our findings highlight the potential for severe disease in this age group and inform other regions to anticipate and prepare their COVID-19 response to include a significant burden of hospitalized and critically ill children and young adults. As SARS-CoV-2 spreads within the United States, regional differences may be apparent based on virus and host factors that are yet to be identified,” Dr. DeBiasi and colleagues concluded.

Robin Steinhorn, MD, serves as an associate editor for the Journal of Pediatrics. The other researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DeBiasi RL et al. J Pediatr. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007.

This article was updated 5/19/20.

Children and young adults in all age groups can develop severe illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the oldest and youngest appear most likely to be hospitalized and possibly critically ill, based on data from a retrospective cohort study of 177 pediatric patients seen at a single center.

“Although children and young adults clearly are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, attention has focused primarily on their potential role in influencing spread and community transmission rather than the potential severity of infection in children and young adults themselves,” wrote Roberta L. DeBiasi, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 44 hospitalized and 133 non-hospitalized children and young adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of the 44 hospitalized patients, 35 were noncritically ill and 9 were critically ill. The study population ranged from 0.1-34 years of age, with a median of 10 years, which was similar between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. However, the median age of critically ill patients was significantly higher, compared with noncritically ill patients (17 years vs. 4 years). All age groups were represented in all cohorts. “However, we noted a bimodal distribution of patients less than 1 year of age and patients greater than 15 years of age representing the largest proportion of patients within the SARS-CoV-2–infected hospitalized and critically ill cohorts,” the researchers noted. Children less than 1 year and adolescents/young adults over 15 years each represented 32% of the 44 hospitalized patients.

Overall, 39% of the 177 patients had underlying medical conditions, the most frequent of which was asthma (20%), which was not significantly more common between hospitalized/nonhospitalized patients or critically ill/noncritically ill patients. Patients also presented with neurologic conditions (6%), diabetes (3%), obesity (2%), cardiac conditions (3%), hematologic conditions (3%) and oncologic conditions (1%). Underlying conditions occurred more commonly in the hospitalized cohort (63%) than in the nonhospitalized cohort (32%).

Neurologic disorders, cardiac conditions, hematologic conditions, and oncologic conditions were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, but not significantly more common among those critically ill versus noncritically ill.

About 76% of the patients presented with respiratory symptoms including rhinorrhea, congestion, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath – with or without fever; 66% had fevers; and 48% had both respiratory symptoms and fever. Shortness of breath was significantly more common among hospitalized patients versus nonhospitalized patients (26% vs. 12%), but less severe respiratory symptoms were significantly more common among nonhospitalized patients, the researchers noted.

Other symptoms – such as diarrhea, vomiting, chest pain, and loss of sense or smell occurred in a small percentage of patients – but were not more likely to occur in any of the cohorts.

Among the critically ill patients, eight of nine needed some level of respiratory support, and four were on ventilators.

“One patient had features consistent with the recently emerged Kawasaki disease–like presentation with hyperinflammatory state, hypotension, and profound myocardial depression,” Dr. DiBiasi and associates noted.

The researchers found coinfection with routine coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or rhinovirus/enterovirus in 4 of 63 (6%) patients, but the clinical impact of these coinfections are unclear.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the ongoing transmission of COVID-19 in the Washington area, the researchers noted. “One potential bias of this study is our regional role in providing critical care for young adults age 21-35 years with COVID-19.” In addition, “we plan to address the role of race and ethnicity after validation of current administrative data and have elected to defer this analysis until completed.”

“Our findings highlight the potential for severe disease in this age group and inform other regions to anticipate and prepare their COVID-19 response to include a significant burden of hospitalized and critically ill children and young adults. As SARS-CoV-2 spreads within the United States, regional differences may be apparent based on virus and host factors that are yet to be identified,” Dr. DeBiasi and colleagues concluded.

Robin Steinhorn, MD, serves as an associate editor for the Journal of Pediatrics. The other researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DeBiasi RL et al. J Pediatr. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007.

This article was updated 5/19/20.

Children and young adults in all age groups can develop severe illness after SARS-CoV-2 infection, but the oldest and youngest appear most likely to be hospitalized and possibly critically ill, based on data from a retrospective cohort study of 177 pediatric patients seen at a single center.

“Although children and young adults clearly are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, attention has focused primarily on their potential role in influencing spread and community transmission rather than the potential severity of infection in children and young adults themselves,” wrote Roberta L. DeBiasi, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Children’s National Hospital, Washington, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Pediatrics, the researchers reviewed data from 44 hospitalized and 133 non-hospitalized children and young adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Of the 44 hospitalized patients, 35 were noncritically ill and 9 were critically ill. The study population ranged from 0.1-34 years of age, with a median of 10 years, which was similar between hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients. However, the median age of critically ill patients was significantly higher, compared with noncritically ill patients (17 years vs. 4 years). All age groups were represented in all cohorts. “However, we noted a bimodal distribution of patients less than 1 year of age and patients greater than 15 years of age representing the largest proportion of patients within the SARS-CoV-2–infected hospitalized and critically ill cohorts,” the researchers noted. Children less than 1 year and adolescents/young adults over 15 years each represented 32% of the 44 hospitalized patients.

Overall, 39% of the 177 patients had underlying medical conditions, the most frequent of which was asthma (20%), which was not significantly more common between hospitalized/nonhospitalized patients or critically ill/noncritically ill patients. Patients also presented with neurologic conditions (6%), diabetes (3%), obesity (2%), cardiac conditions (3%), hematologic conditions (3%) and oncologic conditions (1%). Underlying conditions occurred more commonly in the hospitalized cohort (63%) than in the nonhospitalized cohort (32%).

Neurologic disorders, cardiac conditions, hematologic conditions, and oncologic conditions were significantly more common in hospitalized patients, but not significantly more common among those critically ill versus noncritically ill.

About 76% of the patients presented with respiratory symptoms including rhinorrhea, congestion, sore throat, cough, or shortness of breath – with or without fever; 66% had fevers; and 48% had both respiratory symptoms and fever. Shortness of breath was significantly more common among hospitalized patients versus nonhospitalized patients (26% vs. 12%), but less severe respiratory symptoms were significantly more common among nonhospitalized patients, the researchers noted.

Other symptoms – such as diarrhea, vomiting, chest pain, and loss of sense or smell occurred in a small percentage of patients – but were not more likely to occur in any of the cohorts.

Among the critically ill patients, eight of nine needed some level of respiratory support, and four were on ventilators.

“One patient had features consistent with the recently emerged Kawasaki disease–like presentation with hyperinflammatory state, hypotension, and profound myocardial depression,” Dr. DiBiasi and associates noted.

The researchers found coinfection with routine coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, or rhinovirus/enterovirus in 4 of 63 (6%) patients, but the clinical impact of these coinfections are unclear.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the ongoing transmission of COVID-19 in the Washington area, the researchers noted. “One potential bias of this study is our regional role in providing critical care for young adults age 21-35 years with COVID-19.” In addition, “we plan to address the role of race and ethnicity after validation of current administrative data and have elected to defer this analysis until completed.”

“Our findings highlight the potential for severe disease in this age group and inform other regions to anticipate and prepare their COVID-19 response to include a significant burden of hospitalized and critically ill children and young adults. As SARS-CoV-2 spreads within the United States, regional differences may be apparent based on virus and host factors that are yet to be identified,” Dr. DeBiasi and colleagues concluded.

Robin Steinhorn, MD, serves as an associate editor for the Journal of Pediatrics. The other researchers declared no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DeBiasi RL et al. J Pediatr. 2020 May 6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.007.

This article was updated 5/19/20.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF PEDIATRICS

Dermatologic changes with COVID-19: What we know and don’t know

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

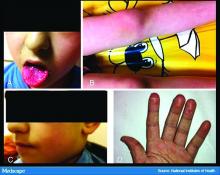

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?

The many dermatologic manifestations of COVID-19

Dr. Lipper: In the series in Spain, almost 1 out of 10 patients were found to have a widespread vesicular rash. And just under half had maculopapular exanthems. The information arising from the AAD registry will be of great interest and build on this paper.

In England, the National Health Service and the Paediatric Intensive Care Society recently put out a warning about an alarming number of children with COVID-19 who developed symptoms mimicking Kawasaki disease (high fever, abdominal pain, rash, swollen lymph nodes, mucositis, and conjunctivitis). These kids have systemic inflammation and vasculitis and are critically ill. That was followed by an alert from the New York City Health Department about cases there, which as of May 6 numbered 64. Another 25 children with similar findings have been identified in France.

This is such a scary development, especially because children were supposed to be relatively “safe” from this virus. Any thoughts on who is at risk or why?

Dr. Fox: It’s very alarming. It appears that these cases look just like Kawasaki disease.

It was once hypothesized that Coronaviridae was the cause of Kawasaki disease. Then that got debunked. But these cases now raise the question of whether Kawasaki disease may be virally mediated. Is it an immune reaction to an infectious trigger? Is it actually Coronaviridae that triggers it?

As with these pernio cases, I think we’re going to learn about the pathophysiology of these diseases that we currently look at as secondary responses or immune reactions to unknown triggers. We’re going to learn a lot about them and about the immune system because of how this virus is acting on the immune system.

Dr. Lipper: As is the case with patients with pernio-like lesions, some of these children with Kawasaki-like disease are PCR negative for SARS-CoV-2. It will be interesting to see what happens with antibody testing in this population.

Dr. Fox: Agree. While some of the manufacturers of serology tests have claimed that they have very high sensitivity and specificity, that has not been my experience.

Dr. Lipper: I’ve had a number of patients with a clinical picture that strongly suggests COVID whose serology tests have been negative.

Dr. Fox: As have I. While this could be the result of faulty tests, my biggest worry is that it means that people with mild disease do not mount an antibody response. And if people who have disease can’t make antibodies, then there’s no herd immunity. If there’s no herd immunity, we’re stuck in lockdown until there’s a vaccine.

Dr. Lipper: That is a scary but real possibility. We need evidence – evidence like that provided by the AAD registry.

Dr. Fox: Agree. I look forward to sharing those results with you when we have them.

Dr. Lipper is a clinical assistant professor at the University of Vermont, Burlington, and a partner at Advanced DermCare in Danbury, Conn.

Dr. Fox is a professor in the department of dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. She is a hospital-based dermatologist who specializes in the care of patients with complex skin conditions. She is immediate past president of the Medical Dermatology Society and current president of the Society of Dermatology Hospitalists.

This article was first published on Medscape.com.

The dermatologic manifestations associated with SARS-CoV-2 are many and varied, with new information virtually daily. Graeme Lipper, MD, a member of the Medscape Dermatology advisory board, discussed what we know and what is still to be learned with Lindy Fox, MD, a professor of dermatology at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry task force.

Graeme M. Lipper, MD

Earlier this spring, before there was any real talk about skin manifestations of COVID, my partner called me in to see an unusual case. His patient was a healthy 20-year-old who had just come back from college and had tender, purple discoloration and swelling on his toes. I shrugged and said “looks like chilblains,” but there was something weird about the case. It seemed more severe, with areas of blistering and erosions, and the discomfort was unusual for run-of-the-mill pernio. This young man had experienced a cough and shortness of breath a few weeks earlier but those symptoms had resolved when we saw him.

That evening, I was on a derm social media site and saw a series of pictures from Italy that blew me away. All of these pictures looked just like this kid’s toes. That’s the first I heard of “COVID toes,” but now they seem to be everywhere. How would you describe this presentation, and how does it differ from typical chilblains?

Lindy P. Fox, MD

I am so proud of dermatologists around the world who have really jumped into action to examine the pathophysiology and immunology behind these findings.

Your experience matches mine. Like you, I first heard about these pernio- or chilblains-like lesions when Europe was experiencing its surge in cases. And while it does indeed look like chilblains, I think the reality is that it is more severe and symptomatic than we would expect. I think your observation is exactly right. There are certainly clinicians who do not believe that this is an association with COVID-19 because the testing is often negative. But to my mind, there are just too many cases at the wrong time of year, all happening concomitantly, and simultaneous with a new virus for me to accept that they are not somehow related.

Dr. Lipper: Some have referred to this as “quarantine toes,” the result of more people at home and walking around barefoot. That doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of sense because it’s happening in both warm and cold climates.

Others have speculated that there is another, unrelated circulating virus causing these pernio cases, but that seems far-fetched.

But the idea of a reporting bias – more patients paying attention to these lesions because they’ve read something in the mass media or seen a report on television and are concerned, and thus present with mild lesions they might otherwise have ignored – may be contributing somewhat. But even that cannot be the sole reason behind the increase.

Dr. Fox: Agree.

Evaluation of the patient with chilblains – then and now

Dr. Lipper: In the past, how did you perform a workup for someone with chilblains?

Dr. Fox: Pre-COVID – and I think we all have divided our world into pre- and post-COVID – the most common thing that I’d be looking for would be a clotting disorder or an autoimmune disease, typically lupus. So I take a good history, review of systems, and look at the skin for signs of lupus or other autoimmune connective tissue diseases. My lab workup is probably limited to an antinuclear antibody (ANA). If the findings are severe and recurrent, I might check for hypercoagulability with an antiphospholipid antibody panel. But that was usually it unless there was something in the history or physical exam that would lead me to look for something less common – for example, cryoglobulins or an underlying hematologic disease that would lead to a predominance of lesions in acral sites.

My approach was the same. In New England, where I practice, I also always look at environmental factors. We would sometimes see chilblains in someone from a warmer climate who came home to the Northeast to ski.

Dr. Lipper: Now, in the post-COVID world, how do you assess these patients? What has changed?

Dr. Fox: That’s a great question. To be frank, our focus now is on not missing a secondary consequence of COVID infection that we might not have picked up before. I’m the first to admit that the workup that we have been doing at UCSF is extremely comprehensive. We may be ordering tests that don’t need to be done. But until we know better what might and might not be affected by COVID, we don’t actually have a sense of whether they’re worth looking for or not.

Right now, my workup includes nasal swab polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for COVID, as well as IgG and IgM serology if available. We have IgG easily available to us. IgM needs approval; at UCSF, it is primarily done in neonates as of now. I also do a workup for autoimmunity and cold-associated disease, which includes an ANA, rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulin, and cold agglutinins.

Because of reported concerns about hypercoagulability in COVID patients, particularly in those who are doing poorly in the hospital, we look for elevations in d-dimers and fibrinogen. We check antiphospholipid antibodies, anticardiolipin antibodies, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. That is probably too much of a workup for the healthy young person, but as of yet, we are just unable to say that those things are universally normal.

There has also been concern that complement may be involved in patients who do poorly and tend to clot a lot. So we are also checking C3, C4, and CH50.

To date, in my patients who have had this workup, I have found one with a positive ANA that was significant (1:320) who also had low complements.

There have been a couple of patients at my institution, not my own patients, who are otherwise fine but have some slight elevation in d-dimers.

Dr. Lipper: Is COVID toes more than one condition?

Some of the initial reports of finger/toe cyanosis out of China were very alarming, with many patients developing skin necrosis or even gangrene. These were critically ill adults with pneumonia and blood markers of disseminated intravascular coagulation, and five out of seven died. In contrast, the cases of pseudo-pernio reported in Europe, and now the United States, seem to be much milder, usually occurring late in the illness or in asymptomatic young people. Do you think these are two different conditions?

Dr. Fox: I believe you have hit the nail on the head. I think it is really important that we don’t confuse those two things. In the inpatient setting, we are clearly seeing patients with a prothrombotic state with associated retiform purpura. For nondermatologists, that usually means star-like, stellate-like, or even lacy purpuric changes with potential for necrosis of the skin. In hospitalized patients, the fingers and toes are usually affected but, interestingly, also the buttocks. When these lesions are biopsied, as has been done by our colleague at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, Joanna Harp, MD, we tend to find thrombosis.

A study of endothelial cell function in patients with COVID-19, published in the Lancet tried to determine whether viral particles could be found in endothelial cells. And the investigators did indeed find these particles. So it appears that the virus is endothelially active, and this might provide some insight into the thromboses seen in hospitalized patients. These patients can develop purple necrotic toes that may progress to gangrene. But that is completely different from what we’re seeing when we say pernio-like or chilblains-like lesions.

The chilblains-like lesions come in several forms. They may be purple, red bumps, often involving the tops of the toes and sometimes the bottom of the feet. Some have been described as target-like or erythema multiforme–like. In others, there may not be individual discrete lesions but rather a redness or bluish, purplish discoloration accompanied by edema of the entire toe or several toes.

Biopsies that I am aware of have identified features consistent with an inflammatory process, all of which can be seen in a typical biopsy of pernio. You can sometimes see lymphocytes surrounding a vessel (called lymphocytic vasculitis) that may damage a vessel and cause a small clot, but the primary process is an inflammatory rather than thrombotic one. You may get a clot in a little tiny vessel secondary to inflammation, and that may lead to some blisters or little areas of necrosis. But you’re not going to see digital necrosis and gangrene. I think that’s an important distinction.

The patients who get the pernio-like lesions are typically children or young adults and are otherwise healthy. Half of them didn’t even have COVID symptoms. If they did have COVID symptoms they were typically mild. So we think the pernio-like lesions are most often occurring in the late stage of the disease and now represent a secondary inflammatory response.

Managing COVID toes

Dr. Lipper: One question I’ve been struggling with is, what do we tell these otherwise healthy patients with purple toes, especially those with no other symptoms? Many of them are testing SARS-CoV-2 negative, both with viral swabs and serologies. Some have suggestive histories like known COVID exposure, recent cough, or travel to high-risk areas. Do we tell them they’re at risk of transmitting the virus? Should they self-quarantine, and for how long? Is there any consensus emerging?

Dr. Fox: This is a good opportunity to plug the American Academy of Dermatology’s COVID-19 Registry, which is run by Esther Freeman, MD, at Massachusetts General Hospital. She has done a phenomenal job in helping us figure out the answers to these exact questions.

I’d encourage any clinicians who have a suspected COVID patient with a skin finding, whether or not infection is confirmed with testing, to enter information about that patient into the registry. That is the only way we will figure out evidence-based answers to a lot of the questions that we’re talking about today.

Based on working with the registry, we know that, rarely, patients who develop pernio-like changes will do so before they get COVID symptoms or at the same time as more typical symptoms. Some patients with these findings are PCR positive, and it is therefore theoretically possible that you could be shedding virus while you’re having the pernio toes. However, more commonly – and this is the experience of most of my colleagues and what we’re seeing at UCSF – pernio is a later finding and most patients are no longer shedding the virus. It appears that pseudo-pernio is an immune reaction and most people are not actively infectious at that point.

The only way to know for sure is to send patients for both PCR testing and antibody testing. If the PCR is negative, the most likely interpretation is that the person is no longer shedding virus, though there can be some false negatives. Therefore, these patients do not need to isolate outside of what I call their COVID pod – family or roommates who have probably been with them the whole time. Any transmission likely would have already occurred.

I tell people who call me concerned about their toes that I do think they should be given a workup for COVID. However, I reassure them that it is usually a good prognostic sign.

What is puzzling is that even in patients with pseudo-chilblains who have a clinical history consistent with COVID or exposure to a COVID-positive family member, antibody testing is often – in fact, most often – negative. There are many hypotheses as to why this is. Maybe the tests just aren’t good. Maybe people with mild disease don’t generate enough antibodies to be detected, Maybe we’re testing at the wrong time. Those are all things that we’re trying to figure out.

But currently, I tell patients that they do not need to strictly isolate. They should still practice social distancing, wear a mask, practice good hand hygiene, and do all of the careful things that we should all be doing. However, they can live within their home environment and be reassured that most likely they are in the convalescent stage.

Dr. Lipper: I find the antibody issue both fascinating and confusing.

In my practice, we’ve noticed a range of symptoms associated with pseudo-pernio. Some people barely realize it’s there and only called because they saw a headline in the news. Others complain of severe burning, throbbing, or itching that keeps them up at night and can sometimes last for weeks. Are there any treatments that seem to help?

Dr. Fox: We can start by saying, as you note, that a lot of patients don’t need interventions. They want reassurance that their toes aren’t going to fall off, that nothing terrible is going to happen to them, and often that’s enough. So far, many patients have contacted us just because they heard about the link between what they were seeing on their feet and COVID. They were likely toward the end of any other symptoms they may have had. But moving forward, I think we’re going to be seeing patients at the more active stage as the public is more aware of this finding.

Most of the time we can manage with clobetasol ointment and low-dose aspirin. I wouldn’t give aspirin to a young child with a high fever, but otherwise I think aspirin is not harmful. A paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings in 2014, before COVID, by Jonathan Cappel, MD, and David Wetter, MD, provides a nice therapeutic algorithm. Assuming that the findings we are seeing now are inflammatory, then I think that algorithm should apply. Nifedipine 20-60 mg/day is an option. Hydroxychloroquine, a maximum of 5 mg/kg per day, is an option. I have used hydroxychloroquine most commonly, pre-COVID, in patients who have symptomatic pernio.

I also use pentoxifylline 400 mg three times a day, which has a slight anti-inflammatory effect, when I think a blood vessel is incidentally involved or the patient has a predisposition to clotting. Nicotinamide 500 mg three times a day can be used, though I have not used it.

Some topical options are nitroglycerin, tacrolimus, and minoxidil.

However, during this post-COVID period, I have not come across many with pseudo-pernio who needed anything more than a topical steroid and some aspirin. But I do know of other physicians who have been taking care of patients with much more symptomatic disease.

Dr. Lipper: That is a comprehensive list. You’ve mentioned some options that I’ve wondered about, especially pentoxifylline, which I have found to be very helpful for livedoid vasculopathy. I should note that these are all off-label uses.

Let’s talk about some other suspected skin manifestations of COVID. A prospective nationwide study in Spain of 375 patients reported on a number of different skin manifestations of COVID.

You’re part of a team doing critically important work with the American Academy of Dermatology COVID-19 Dermatology Registry. I know it’s early going, but what are some of the other common skin presentations you’re finding?

Dr. Fox: I’m glad you brought up that paper out of Spain. I think it is really good and does highlight the difference in acute versus convalescent cutaneous manifestations and prognosis. It confirms what we’re seeing. Retiform purpura is an early finding associated with ill patients in the hospital. Pseudo pernio-like lesions tend to be later-stage and in younger, healthier patients.

Interestingly, the vesicular eruption that those investigators describe – monomorphic vesicles on the trunk and extremity – can occur in the more acute phase. That’s fascinating to me because widespread vesicular eruptions are not a thing that we commonly see. If it is not an autoimmune blistering disease, and not a drug-induced blistering process, then you’re really left with viral. Rickettsialpox can do that, as can primary varicella, disseminated herpes, disseminated zoster, and now COVID. So that’s intriguing.

I got called to see a patient yesterday who had symptoms of COVID about a month ago. She was not PCR tested at the time but she is now negative. She has a widespread eruption of tiny vesicles on an erythematous base. An IgG for COVID is positive. How do we decide whether her skin lesions have active virus in them?