User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Creating best practices for APPs

A holistic approach to integration

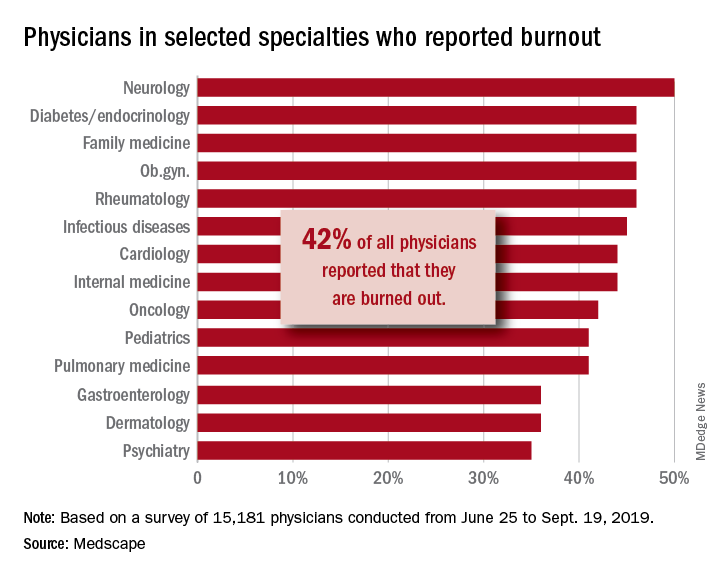

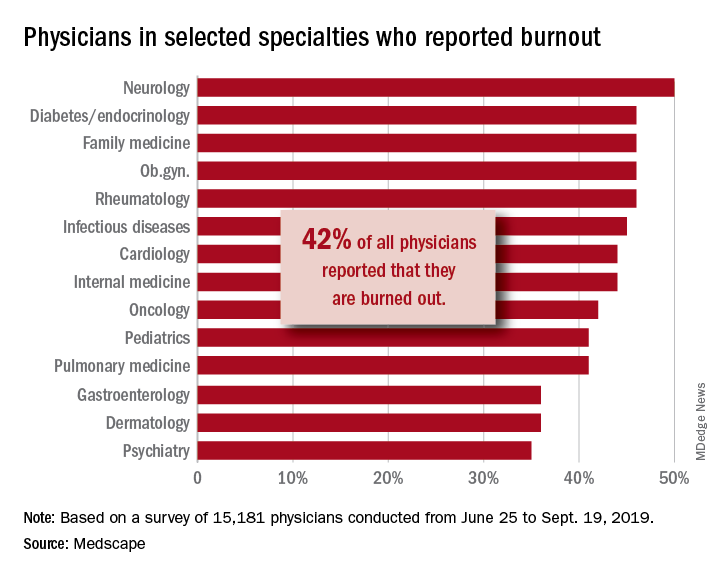

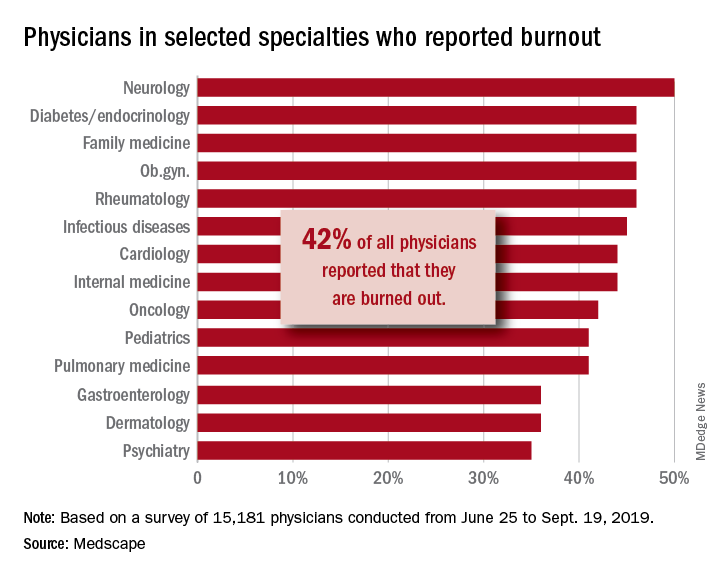

Hospital medicine groups (HMGs) nationally are confronted with a host of challenging issues: increased patient volume/complexities, resident duty-hour restrictions, and a rise in provider burnout. Many are turning to advanced practice providers (APPs) to help lighten these burdens.

But no practical guidelines exist around how to successfully incorporate APPs in a way that meets the needs of the patients, the providers, the HMG, and the health system, according to Kasey Bowden, MSN, FNP, AG-ACNP, lead author of a HM19 abstract on that subject.

“Much of the recent literature around APP utilization involves descriptive anecdotes on how individual HMGs have utilized APPs, and what metrics this helped them to achieve,” she said. “While these stories are often compelling, they provide no tangible value to HMGs looking to incorporate APPs into practice, as they do not address unique elements that limit successful APP integration, including diverse educational backgrounds of APPs and exceedingly high turnover rates (12.6% nationally).”

Ms. Bowden and coauthors created a conceptual framework, which recognizes that, without taking a holistic approach, many HMGs will fail to successfully integrate APPs. “Our hope is that by utilizing this framework to define APP-physician best practices, we will be able to create a useful tool for all HMGs that will promote successful APP-physician collaborative practice models.”

She thinks that hospitalists could also use this framework to examine their current practice models and to see where there may be opportunity for improvement. For example, a group may look at their own APP turnover rate. “If turnover rate is high in the first year, it may suggest inadequate onboarding/training, if it is high after 3 years, this may suggest minimal opportunities for professional growth and advancement,” Ms. Bowden said. “I would love to see a consensus group form within SHM of physician and APP leaders to utilize this framework to establish ‘APP-Physician best practices,’ and create a guideline available to all HMGs so that they can successfully incorporate APPs into their practice,” she said.

Reference

1. Bowden K et al. Creation of APP-physician best practices: A necessary tool for the growing APP workforce. Hospital Medicine 2019, Abstract 436.

A holistic approach to integration

A holistic approach to integration

Hospital medicine groups (HMGs) nationally are confronted with a host of challenging issues: increased patient volume/complexities, resident duty-hour restrictions, and a rise in provider burnout. Many are turning to advanced practice providers (APPs) to help lighten these burdens.

But no practical guidelines exist around how to successfully incorporate APPs in a way that meets the needs of the patients, the providers, the HMG, and the health system, according to Kasey Bowden, MSN, FNP, AG-ACNP, lead author of a HM19 abstract on that subject.

“Much of the recent literature around APP utilization involves descriptive anecdotes on how individual HMGs have utilized APPs, and what metrics this helped them to achieve,” she said. “While these stories are often compelling, they provide no tangible value to HMGs looking to incorporate APPs into practice, as they do not address unique elements that limit successful APP integration, including diverse educational backgrounds of APPs and exceedingly high turnover rates (12.6% nationally).”

Ms. Bowden and coauthors created a conceptual framework, which recognizes that, without taking a holistic approach, many HMGs will fail to successfully integrate APPs. “Our hope is that by utilizing this framework to define APP-physician best practices, we will be able to create a useful tool for all HMGs that will promote successful APP-physician collaborative practice models.”

She thinks that hospitalists could also use this framework to examine their current practice models and to see where there may be opportunity for improvement. For example, a group may look at their own APP turnover rate. “If turnover rate is high in the first year, it may suggest inadequate onboarding/training, if it is high after 3 years, this may suggest minimal opportunities for professional growth and advancement,” Ms. Bowden said. “I would love to see a consensus group form within SHM of physician and APP leaders to utilize this framework to establish ‘APP-Physician best practices,’ and create a guideline available to all HMGs so that they can successfully incorporate APPs into their practice,” she said.

Reference

1. Bowden K et al. Creation of APP-physician best practices: A necessary tool for the growing APP workforce. Hospital Medicine 2019, Abstract 436.

Hospital medicine groups (HMGs) nationally are confronted with a host of challenging issues: increased patient volume/complexities, resident duty-hour restrictions, and a rise in provider burnout. Many are turning to advanced practice providers (APPs) to help lighten these burdens.

But no practical guidelines exist around how to successfully incorporate APPs in a way that meets the needs of the patients, the providers, the HMG, and the health system, according to Kasey Bowden, MSN, FNP, AG-ACNP, lead author of a HM19 abstract on that subject.

“Much of the recent literature around APP utilization involves descriptive anecdotes on how individual HMGs have utilized APPs, and what metrics this helped them to achieve,” she said. “While these stories are often compelling, they provide no tangible value to HMGs looking to incorporate APPs into practice, as they do not address unique elements that limit successful APP integration, including diverse educational backgrounds of APPs and exceedingly high turnover rates (12.6% nationally).”

Ms. Bowden and coauthors created a conceptual framework, which recognizes that, without taking a holistic approach, many HMGs will fail to successfully integrate APPs. “Our hope is that by utilizing this framework to define APP-physician best practices, we will be able to create a useful tool for all HMGs that will promote successful APP-physician collaborative practice models.”

She thinks that hospitalists could also use this framework to examine their current practice models and to see where there may be opportunity for improvement. For example, a group may look at their own APP turnover rate. “If turnover rate is high in the first year, it may suggest inadequate onboarding/training, if it is high after 3 years, this may suggest minimal opportunities for professional growth and advancement,” Ms. Bowden said. “I would love to see a consensus group form within SHM of physician and APP leaders to utilize this framework to establish ‘APP-Physician best practices,’ and create a guideline available to all HMGs so that they can successfully incorporate APPs into their practice,” she said.

Reference

1. Bowden K et al. Creation of APP-physician best practices: A necessary tool for the growing APP workforce. Hospital Medicine 2019, Abstract 436.

DOACs for treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism

Bleeding risk may determine best option

Case

A 52-year-old female with past medical history of diabetes, hypertension, and stage 4 lung cancer on palliative chemotherapy presents with acute-onset dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and cough. Her exam is notable for tachycardia, hypoxemia, and diminished breath sounds. A CT pulmonary embolism study shows new left segmental thrombus. What is her preferred method of anticoagulation?

Brief overview of the issue

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a significant concern in the context of malignancy and is associated with higher rates of mortality at 1 year.

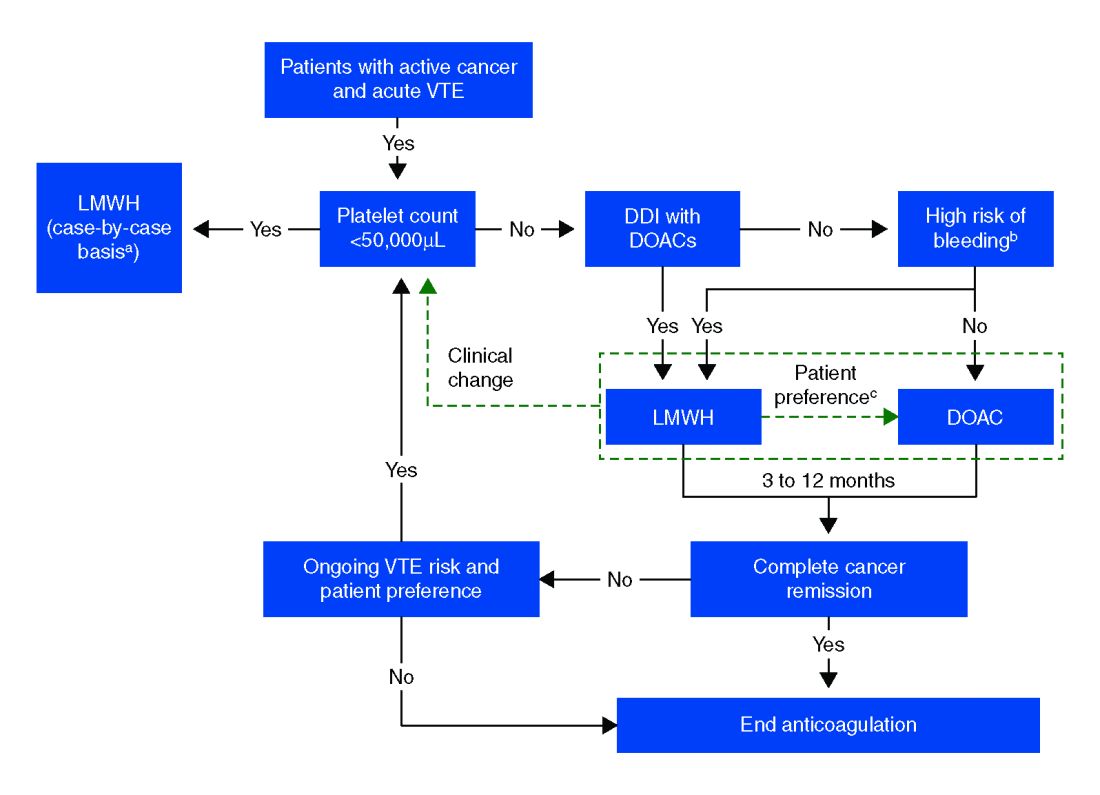

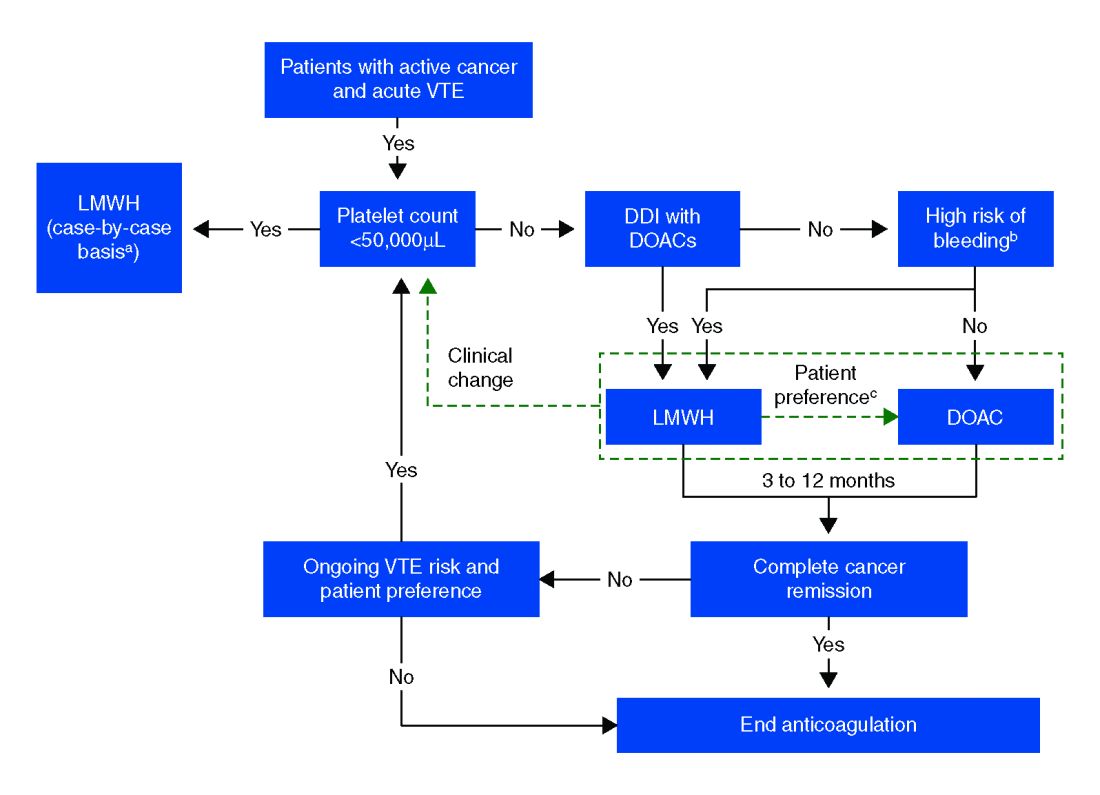

The standard of care in the recent past has relied on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) after several trials showed decreased VTE recurrence in cancer patients, compared with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) treatment.1,2 LMWH has been recommended as a first-line treatment by clinical guidelines for cancer-related VTE given lower drug-drug interactions between LMWH and chemotherapy regimens, as compared with traditional VKAs, and it does not rely on intestinal absorption.3

In more recent years, the focus has shifted to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as potential treatment options for cancer-related VTE given their ease of administration, low side-effect profile, and decreased cost. Until recently, studies have mainly been small and largely retrospective, however, several larger randomized control studies have recently been published.

Overview of the data

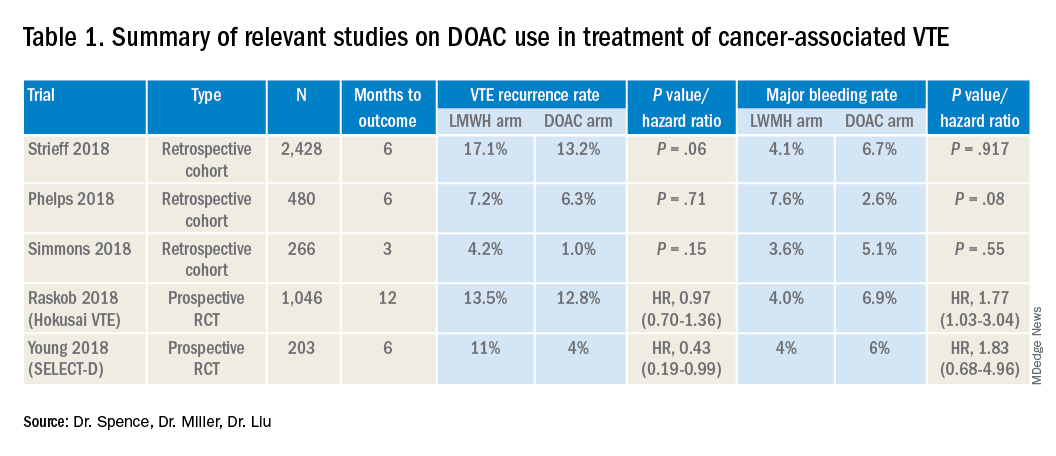

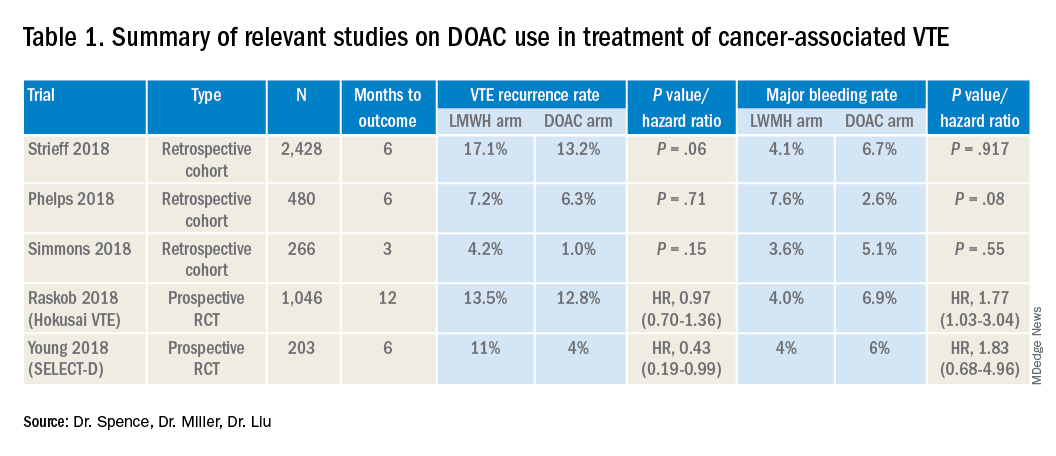

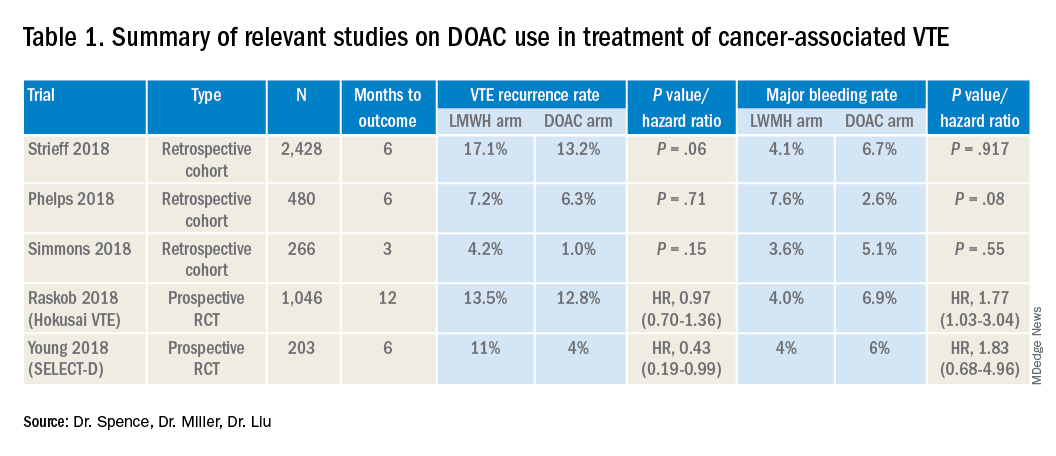

Several retrospective trials have investigated the use of DOACs in cancer-associated VTE. One study looking at VTE recurrence rates showed a trend towards lower rates with rivaroxaban, compared with LMWH at 6 months (13% vs. 17%) that was significantly lower at 12 months (16.5 % vs. 22%). Similar results were found when comparing rivaroxaban to warfarin. Major bleeding rates were similar among cohorts.4

Several other retrospective cohort studies looking at treatment of cancer-associated VTE treated with LMWH vs. DOACs found that overall patients treated with DOACs had cancers with lower risk for VTE and had lower burden of metastatic disease. When this was adjusted for, there was no significant difference in the rate of recurrent cancer-associated thrombosis or major bleeding.5,6

Recently several prospective studies have corroborated the noninferiority or slight superiority of DOACs when compared with LMWH in treatment of cancer-associated VTE, while showing similar rates of bleeding. These are summarized as follows: a prospective, open-label, randomized controlled (RCT), noninferiority trial of 1,046 patients with malignancy-related VTE assigned to either LMWH for at least 5 days, followed by oral edoxaban vs. subcutaneous dalteparin for at least 6 months and up to 12 months. Investigators found no significant difference in the rate of recurrent VTE in the edoxaban group (12.8%), as compared to the dalteparin group (13.5%, P = .006 for noninferiority). Risk of major bleeding was not significantly different between the groups.7

A small RCT of 203 patients comparing recurrent VTE rates with rivaroxaban vs. dalteparin found significantly fewer recurrent clots in the rivaroxaban group compared to the dalteparin group (11% vs 4%) with no significant difference in the 6-month cumulative rate of major bleeding, 4% in the dalteparin group and 6% for the rivaroxaban group.8 Preliminary results from the ADAM VTE trial comparing apixaban to dalteparin found significantly fewer recurrent VTE in the apixaban group (3.4% vs. 14.1%) with no significant difference in major bleeding events (0% vs 2.1%).9 The Caravaggio study is a large multinational randomized, controlled, open-label, noninferiority trial looking at apixaban vs. dalteparin with endpoints being 6-month recurrent VTE and bleeding risk that will likely report results soon.

Risk of bleeding is also a major consideration in VTE treatment as studies suggest that patients with metastatic cancer are at sixfold higher risk for anticoagulant-associated bleeding.3 Subgroup analysis of Hokusai VTE cancer study found that major bleeding occurred in 32 of 522 patients given edoxaban and 16 of 524 patients treated with dalteparin. Excess of major bleeding with edoxaban was confined to patients with GI cancer. However, rates of severe major bleeding at presentation were similar.10

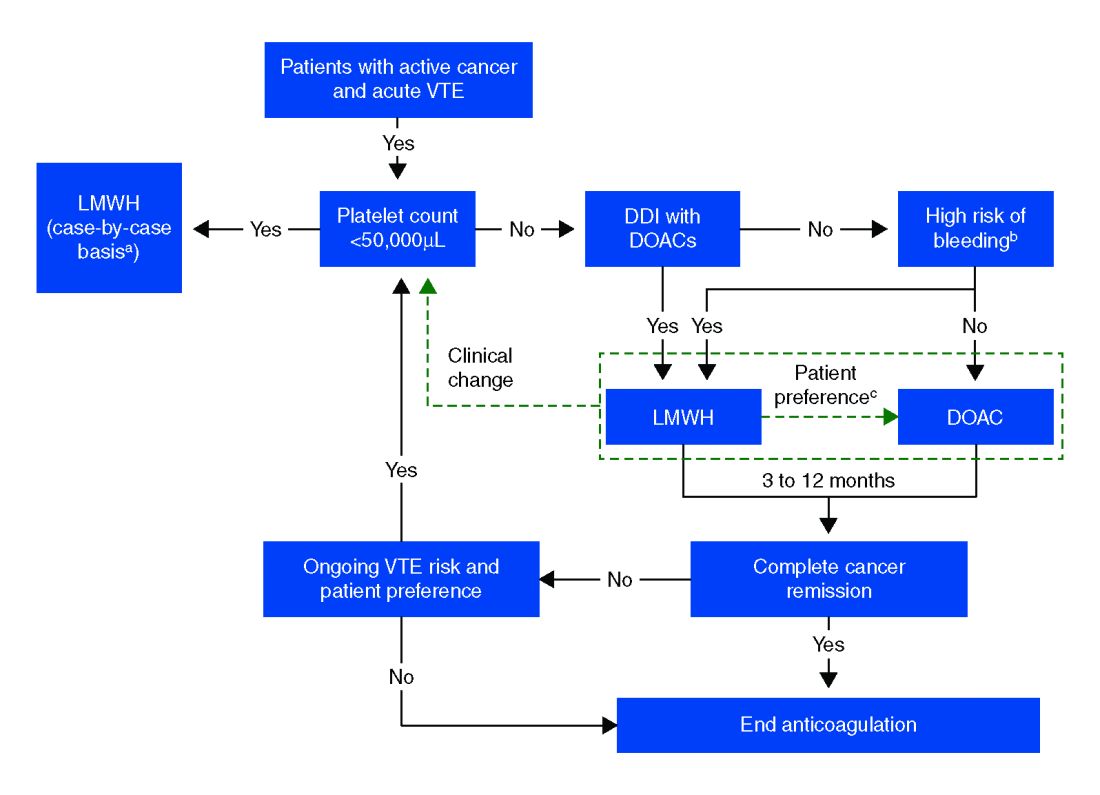

Overall, the existing data suggests that DOACs may be a viable option in the treatment of malignancy-associated VTE given its similar efficacy in preventing recurrent VTE without significant increased risk of major bleeding. The 2018 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis VTE in cancer guidelines have been updated to include rivaroxaban and edoxaban for use in patients at low risk of bleeding, but recommend an informed discussion between patients and clinicians in deciding between DOAC and LMWH.11 The Chest VTE guidelines have not been updated since 2016, prior to when the above mentioned DOAC studies were published.

Application of data to our patient

Compared with patients without cancer, anticoagulation in cancer patients with acute VTE is challenging because of higher rates of VTE recurrence and bleeding, as well as the potential for drug interactions with anticancer agents. Our patient is not at increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and no drug interactions exist between her current chemotherapy regimen and the available DOACs, therefore she is a candidate for treatment with a DOAC.

After an informed discussion, she chose to start rivaroxaban for treatment of her pulmonary embolism. While more studies are needed to definitively determine the best treatment for cancer-associated VTE, DOACs appear to be an attractive alternative to LMWH. Patient preferences of taking oral medications over injections as well as the significant cost savings of DOACs over LMWH will likely play into many patients’ and providers’ anticoagulant choices.

Bottom line

Direct oral anticoagulants are a treatment option for cancer-associated VTE in patients at low risk of bleeding complications. Patients at increased risk of bleeding (especially patients with GI malignancies) should continue to be treated with LMWH.

Dr. Spence is a hospitalist and palliative care physician at Denver Health, and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Miller and Dr. Liu are hospitalists at Denver Health, and assistant professors of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver.

References

1. Hull RD et al. Long term low-molecular-weight heparin versus usual care in proximal-vein thrombosis patient with cancer. Am J Med. 2006;19(12):1062-72.

2. Lee AY et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus Coumadin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-53.

3. Ay C et al. Treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in the age of direct oral anticoagulants. Ann Oncol. 2019 Mar 27 [epub].

4. Streiff MB et al. Effectiveness and safety of anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Am J Hematol. 2018 May;93(5):664-71.

5. Phelps MK et al. A single center retrospective cohort study comparing low-molecular-weight heparins to direct oral anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer – A real-world experience. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019 Jun;25(4):793-800.

6. Simmons B et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared to enoxaparin in treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. Eur J Haematol. 2018 Apr 4. (Epub).

7. Raskob GE et al.; Hokusai VTE Cancer Investigators. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 15;378(7):615-24.

8. Young AM et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: Results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 10;36(20):2017-23.

9. McBane, RD et al. Apixaban, dalteparin, in active cancer associated venous thromboembolism, the ADAM VTE trial. Blood. 2018 Nov 29;132(suppl 1):421.

10. Kraaijpoel N et al. Clinical impact of bleeding in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: Results from the Hokusai VTE cancer study. Thromb Haemost. 2018 Aug;118(8):1439-49.

11. Khorana AA et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: Guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Sep;16(9):1891-94.

Key points

- DOACs are a reasonable treatment option for malignancy-associated VTE in patients without GI tract malignancies and at low risk for bleeding complications.

- In patients with gastrointestinal malignancies or increased risk of bleeding, DOACs may have an increased bleeding risk and therefore LMWH is recommended.

- An informed discussion should occur between providers and patients to determine the best treatment option for cancer patients with VTE.

Additional reading

Dong Y et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019 May 6.

Khorana AA et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Sep;16(9):1891-94.

Tritschler T et al. Venous thromboembolism advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018 Oct;320(15):1583-94.

Quiz

Which of the following is the recommended treatment of VTE in a patient with brain metastases?

A. Unfractionated heparin

B. Low molecular weight heparin

C. Direct oral anticoagulant

D. Vitamin K antagonist

The answer is B. Although there are very few data, LMWH is the recommended agent in patients with VTE and brain metastases.

A. LMWH has been shown to decrease mortality in patients with VTE and cancer, compared with unfractionated heparin (risk ratio, 0.66).

C. The safety of DOACs is not yet well established in patients with brain tumors. Antidotes and/or specific reversal agents for some DOACs are not available.

D. Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin are not recommended in cancer patients because LMWH has a reduced risk of recurrent VTE without increased risk of bleeding.

Bleeding risk may determine best option

Bleeding risk may determine best option

Case

A 52-year-old female with past medical history of diabetes, hypertension, and stage 4 lung cancer on palliative chemotherapy presents with acute-onset dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and cough. Her exam is notable for tachycardia, hypoxemia, and diminished breath sounds. A CT pulmonary embolism study shows new left segmental thrombus. What is her preferred method of anticoagulation?

Brief overview of the issue

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a significant concern in the context of malignancy and is associated with higher rates of mortality at 1 year.

The standard of care in the recent past has relied on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) after several trials showed decreased VTE recurrence in cancer patients, compared with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) treatment.1,2 LMWH has been recommended as a first-line treatment by clinical guidelines for cancer-related VTE given lower drug-drug interactions between LMWH and chemotherapy regimens, as compared with traditional VKAs, and it does not rely on intestinal absorption.3

In more recent years, the focus has shifted to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as potential treatment options for cancer-related VTE given their ease of administration, low side-effect profile, and decreased cost. Until recently, studies have mainly been small and largely retrospective, however, several larger randomized control studies have recently been published.

Overview of the data

Several retrospective trials have investigated the use of DOACs in cancer-associated VTE. One study looking at VTE recurrence rates showed a trend towards lower rates with rivaroxaban, compared with LMWH at 6 months (13% vs. 17%) that was significantly lower at 12 months (16.5 % vs. 22%). Similar results were found when comparing rivaroxaban to warfarin. Major bleeding rates were similar among cohorts.4

Several other retrospective cohort studies looking at treatment of cancer-associated VTE treated with LMWH vs. DOACs found that overall patients treated with DOACs had cancers with lower risk for VTE and had lower burden of metastatic disease. When this was adjusted for, there was no significant difference in the rate of recurrent cancer-associated thrombosis or major bleeding.5,6

Recently several prospective studies have corroborated the noninferiority or slight superiority of DOACs when compared with LMWH in treatment of cancer-associated VTE, while showing similar rates of bleeding. These are summarized as follows: a prospective, open-label, randomized controlled (RCT), noninferiority trial of 1,046 patients with malignancy-related VTE assigned to either LMWH for at least 5 days, followed by oral edoxaban vs. subcutaneous dalteparin for at least 6 months and up to 12 months. Investigators found no significant difference in the rate of recurrent VTE in the edoxaban group (12.8%), as compared to the dalteparin group (13.5%, P = .006 for noninferiority). Risk of major bleeding was not significantly different between the groups.7

A small RCT of 203 patients comparing recurrent VTE rates with rivaroxaban vs. dalteparin found significantly fewer recurrent clots in the rivaroxaban group compared to the dalteparin group (11% vs 4%) with no significant difference in the 6-month cumulative rate of major bleeding, 4% in the dalteparin group and 6% for the rivaroxaban group.8 Preliminary results from the ADAM VTE trial comparing apixaban to dalteparin found significantly fewer recurrent VTE in the apixaban group (3.4% vs. 14.1%) with no significant difference in major bleeding events (0% vs 2.1%).9 The Caravaggio study is a large multinational randomized, controlled, open-label, noninferiority trial looking at apixaban vs. dalteparin with endpoints being 6-month recurrent VTE and bleeding risk that will likely report results soon.

Risk of bleeding is also a major consideration in VTE treatment as studies suggest that patients with metastatic cancer are at sixfold higher risk for anticoagulant-associated bleeding.3 Subgroup analysis of Hokusai VTE cancer study found that major bleeding occurred in 32 of 522 patients given edoxaban and 16 of 524 patients treated with dalteparin. Excess of major bleeding with edoxaban was confined to patients with GI cancer. However, rates of severe major bleeding at presentation were similar.10

Overall, the existing data suggests that DOACs may be a viable option in the treatment of malignancy-associated VTE given its similar efficacy in preventing recurrent VTE without significant increased risk of major bleeding. The 2018 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis VTE in cancer guidelines have been updated to include rivaroxaban and edoxaban for use in patients at low risk of bleeding, but recommend an informed discussion between patients and clinicians in deciding between DOAC and LMWH.11 The Chest VTE guidelines have not been updated since 2016, prior to when the above mentioned DOAC studies were published.

Application of data to our patient

Compared with patients without cancer, anticoagulation in cancer patients with acute VTE is challenging because of higher rates of VTE recurrence and bleeding, as well as the potential for drug interactions with anticancer agents. Our patient is not at increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and no drug interactions exist between her current chemotherapy regimen and the available DOACs, therefore she is a candidate for treatment with a DOAC.

After an informed discussion, she chose to start rivaroxaban for treatment of her pulmonary embolism. While more studies are needed to definitively determine the best treatment for cancer-associated VTE, DOACs appear to be an attractive alternative to LMWH. Patient preferences of taking oral medications over injections as well as the significant cost savings of DOACs over LMWH will likely play into many patients’ and providers’ anticoagulant choices.

Bottom line

Direct oral anticoagulants are a treatment option for cancer-associated VTE in patients at low risk of bleeding complications. Patients at increased risk of bleeding (especially patients with GI malignancies) should continue to be treated with LMWH.

Dr. Spence is a hospitalist and palliative care physician at Denver Health, and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Miller and Dr. Liu are hospitalists at Denver Health, and assistant professors of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver.

References

1. Hull RD et al. Long term low-molecular-weight heparin versus usual care in proximal-vein thrombosis patient with cancer. Am J Med. 2006;19(12):1062-72.

2. Lee AY et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus Coumadin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-53.

3. Ay C et al. Treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in the age of direct oral anticoagulants. Ann Oncol. 2019 Mar 27 [epub].

4. Streiff MB et al. Effectiveness and safety of anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Am J Hematol. 2018 May;93(5):664-71.

5. Phelps MK et al. A single center retrospective cohort study comparing low-molecular-weight heparins to direct oral anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer – A real-world experience. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019 Jun;25(4):793-800.

6. Simmons B et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared to enoxaparin in treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. Eur J Haematol. 2018 Apr 4. (Epub).

7. Raskob GE et al.; Hokusai VTE Cancer Investigators. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 15;378(7):615-24.

8. Young AM et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: Results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 10;36(20):2017-23.

9. McBane, RD et al. Apixaban, dalteparin, in active cancer associated venous thromboembolism, the ADAM VTE trial. Blood. 2018 Nov 29;132(suppl 1):421.

10. Kraaijpoel N et al. Clinical impact of bleeding in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: Results from the Hokusai VTE cancer study. Thromb Haemost. 2018 Aug;118(8):1439-49.

11. Khorana AA et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: Guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Sep;16(9):1891-94.

Key points

- DOACs are a reasonable treatment option for malignancy-associated VTE in patients without GI tract malignancies and at low risk for bleeding complications.

- In patients with gastrointestinal malignancies or increased risk of bleeding, DOACs may have an increased bleeding risk and therefore LMWH is recommended.

- An informed discussion should occur between providers and patients to determine the best treatment option for cancer patients with VTE.

Additional reading

Dong Y et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019 May 6.

Khorana AA et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Sep;16(9):1891-94.

Tritschler T et al. Venous thromboembolism advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018 Oct;320(15):1583-94.

Quiz

Which of the following is the recommended treatment of VTE in a patient with brain metastases?

A. Unfractionated heparin

B. Low molecular weight heparin

C. Direct oral anticoagulant

D. Vitamin K antagonist

The answer is B. Although there are very few data, LMWH is the recommended agent in patients with VTE and brain metastases.

A. LMWH has been shown to decrease mortality in patients with VTE and cancer, compared with unfractionated heparin (risk ratio, 0.66).

C. The safety of DOACs is not yet well established in patients with brain tumors. Antidotes and/or specific reversal agents for some DOACs are not available.

D. Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin are not recommended in cancer patients because LMWH has a reduced risk of recurrent VTE without increased risk of bleeding.

Case

A 52-year-old female with past medical history of diabetes, hypertension, and stage 4 lung cancer on palliative chemotherapy presents with acute-onset dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and cough. Her exam is notable for tachycardia, hypoxemia, and diminished breath sounds. A CT pulmonary embolism study shows new left segmental thrombus. What is her preferred method of anticoagulation?

Brief overview of the issue

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a significant concern in the context of malignancy and is associated with higher rates of mortality at 1 year.

The standard of care in the recent past has relied on low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) after several trials showed decreased VTE recurrence in cancer patients, compared with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) treatment.1,2 LMWH has been recommended as a first-line treatment by clinical guidelines for cancer-related VTE given lower drug-drug interactions between LMWH and chemotherapy regimens, as compared with traditional VKAs, and it does not rely on intestinal absorption.3

In more recent years, the focus has shifted to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as potential treatment options for cancer-related VTE given their ease of administration, low side-effect profile, and decreased cost. Until recently, studies have mainly been small and largely retrospective, however, several larger randomized control studies have recently been published.

Overview of the data

Several retrospective trials have investigated the use of DOACs in cancer-associated VTE. One study looking at VTE recurrence rates showed a trend towards lower rates with rivaroxaban, compared with LMWH at 6 months (13% vs. 17%) that was significantly lower at 12 months (16.5 % vs. 22%). Similar results were found when comparing rivaroxaban to warfarin. Major bleeding rates were similar among cohorts.4

Several other retrospective cohort studies looking at treatment of cancer-associated VTE treated with LMWH vs. DOACs found that overall patients treated with DOACs had cancers with lower risk for VTE and had lower burden of metastatic disease. When this was adjusted for, there was no significant difference in the rate of recurrent cancer-associated thrombosis or major bleeding.5,6

Recently several prospective studies have corroborated the noninferiority or slight superiority of DOACs when compared with LMWH in treatment of cancer-associated VTE, while showing similar rates of bleeding. These are summarized as follows: a prospective, open-label, randomized controlled (RCT), noninferiority trial of 1,046 patients with malignancy-related VTE assigned to either LMWH for at least 5 days, followed by oral edoxaban vs. subcutaneous dalteparin for at least 6 months and up to 12 months. Investigators found no significant difference in the rate of recurrent VTE in the edoxaban group (12.8%), as compared to the dalteparin group (13.5%, P = .006 for noninferiority). Risk of major bleeding was not significantly different between the groups.7

A small RCT of 203 patients comparing recurrent VTE rates with rivaroxaban vs. dalteparin found significantly fewer recurrent clots in the rivaroxaban group compared to the dalteparin group (11% vs 4%) with no significant difference in the 6-month cumulative rate of major bleeding, 4% in the dalteparin group and 6% for the rivaroxaban group.8 Preliminary results from the ADAM VTE trial comparing apixaban to dalteparin found significantly fewer recurrent VTE in the apixaban group (3.4% vs. 14.1%) with no significant difference in major bleeding events (0% vs 2.1%).9 The Caravaggio study is a large multinational randomized, controlled, open-label, noninferiority trial looking at apixaban vs. dalteparin with endpoints being 6-month recurrent VTE and bleeding risk that will likely report results soon.

Risk of bleeding is also a major consideration in VTE treatment as studies suggest that patients with metastatic cancer are at sixfold higher risk for anticoagulant-associated bleeding.3 Subgroup analysis of Hokusai VTE cancer study found that major bleeding occurred in 32 of 522 patients given edoxaban and 16 of 524 patients treated with dalteparin. Excess of major bleeding with edoxaban was confined to patients with GI cancer. However, rates of severe major bleeding at presentation were similar.10

Overall, the existing data suggests that DOACs may be a viable option in the treatment of malignancy-associated VTE given its similar efficacy in preventing recurrent VTE without significant increased risk of major bleeding. The 2018 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis VTE in cancer guidelines have been updated to include rivaroxaban and edoxaban for use in patients at low risk of bleeding, but recommend an informed discussion between patients and clinicians in deciding between DOAC and LMWH.11 The Chest VTE guidelines have not been updated since 2016, prior to when the above mentioned DOAC studies were published.

Application of data to our patient

Compared with patients without cancer, anticoagulation in cancer patients with acute VTE is challenging because of higher rates of VTE recurrence and bleeding, as well as the potential for drug interactions with anticancer agents. Our patient is not at increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and no drug interactions exist between her current chemotherapy regimen and the available DOACs, therefore she is a candidate for treatment with a DOAC.

After an informed discussion, she chose to start rivaroxaban for treatment of her pulmonary embolism. While more studies are needed to definitively determine the best treatment for cancer-associated VTE, DOACs appear to be an attractive alternative to LMWH. Patient preferences of taking oral medications over injections as well as the significant cost savings of DOACs over LMWH will likely play into many patients’ and providers’ anticoagulant choices.

Bottom line

Direct oral anticoagulants are a treatment option for cancer-associated VTE in patients at low risk of bleeding complications. Patients at increased risk of bleeding (especially patients with GI malignancies) should continue to be treated with LMWH.

Dr. Spence is a hospitalist and palliative care physician at Denver Health, and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. Dr. Miller and Dr. Liu are hospitalists at Denver Health, and assistant professors of medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver.

References

1. Hull RD et al. Long term low-molecular-weight heparin versus usual care in proximal-vein thrombosis patient with cancer. Am J Med. 2006;19(12):1062-72.

2. Lee AY et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin versus Coumadin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(2):146-53.

3. Ay C et al. Treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in the age of direct oral anticoagulants. Ann Oncol. 2019 Mar 27 [epub].

4. Streiff MB et al. Effectiveness and safety of anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. Am J Hematol. 2018 May;93(5):664-71.

5. Phelps MK et al. A single center retrospective cohort study comparing low-molecular-weight heparins to direct oral anticoagulants for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer – A real-world experience. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019 Jun;25(4):793-800.

6. Simmons B et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban compared to enoxaparin in treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. Eur J Haematol. 2018 Apr 4. (Epub).

7. Raskob GE et al.; Hokusai VTE Cancer Investigators. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2018 Feb 15;378(7):615-24.

8. Young AM et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: Results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol. 2018 Jul 10;36(20):2017-23.

9. McBane, RD et al. Apixaban, dalteparin, in active cancer associated venous thromboembolism, the ADAM VTE trial. Blood. 2018 Nov 29;132(suppl 1):421.

10. Kraaijpoel N et al. Clinical impact of bleeding in cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: Results from the Hokusai VTE cancer study. Thromb Haemost. 2018 Aug;118(8):1439-49.

11. Khorana AA et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: Guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Sep;16(9):1891-94.

Key points

- DOACs are a reasonable treatment option for malignancy-associated VTE in patients without GI tract malignancies and at low risk for bleeding complications.

- In patients with gastrointestinal malignancies or increased risk of bleeding, DOACs may have an increased bleeding risk and therefore LMWH is recommended.

- An informed discussion should occur between providers and patients to determine the best treatment option for cancer patients with VTE.

Additional reading

Dong Y et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants versus low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2019 May 6.

Khorana AA et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2018 Sep;16(9):1891-94.

Tritschler T et al. Venous thromboembolism advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2018 Oct;320(15):1583-94.

Quiz

Which of the following is the recommended treatment of VTE in a patient with brain metastases?

A. Unfractionated heparin

B. Low molecular weight heparin

C. Direct oral anticoagulant

D. Vitamin K antagonist

The answer is B. Although there are very few data, LMWH is the recommended agent in patients with VTE and brain metastases.

A. LMWH has been shown to decrease mortality in patients with VTE and cancer, compared with unfractionated heparin (risk ratio, 0.66).

C. The safety of DOACs is not yet well established in patients with brain tumors. Antidotes and/or specific reversal agents for some DOACs are not available.

D. Vitamin K antagonists such as warfarin are not recommended in cancer patients because LMWH has a reduced risk of recurrent VTE without increased risk of bleeding.

Cardiac biomarkers refine antihypertensive drug initiation decisions

PHILADELPHIA – Incorporation of cardiac biomarkers into current guideline-based decision-making regarding initiation of antihypertensive medication in patients with previously untreated mild or moderate high blood pressure leads to more appropriate and selective matching of intensive blood pressure control with true patient risk, Ambarish Pandey, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

That’s because the 2017 American College of Cardiology/AHA blood pressure guidelines recommend incorporating the ACC/AHA 10-Year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Calculator into decision making as to whether to start antihypertensive drug therapy in patients with stage 1 hypertension (130-139/80-89 mm Hg), but the risk calculator doesn’t account for the risk of heart failure.

Yet by far the greatest benefit of intensive BP lowering is in reducing the risk of developing heart failure, as demonstrated in the landmark SPRINT trial, which showed that intensive BP lowering achieved much greater risk reduction in new-onset heart failure than in atherosclerotic cardiovascular events.

Thus, there’s a need for better strategies to guide antihypertensive therapy. And therein lies the rationale for incorporating into the risk assessment an individual’s values for N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which reflects chronic myocardial stress, and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), which when elevated signals myocardial injury.

“Cardiac biomarkers are intermediate phenotypes from hypertension to future cardiovascular events. They can identify individuals at increased risk for atherosclerotic events, and at even higher risk for heart failure events,” explained Dr. Pandey, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

He presented a study of 12,987 participants in three major U.S. cohort studies: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Dallas Heart Study. At baseline, none of the participants were on antihypertensive therapy or had known cardiovascular disease. During 10 years of prospective follow-up, 825 of them experienced a first cardiovascular disease event: 251 developed heart failure and 574 had an MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death. Dr. Pandey and his coworkers calculated the cardiovascular event incidence rate and number-needed-to-treat with intensive antihypertensive drug therapy to prevent a first cardiovascular disease event on the basis of whether patients in the various BP categories were positive or negative for one or more biomarkers.

The results

Fifty-four percent of subjects had normal BP, defined in the guidelines as less than 120/80 mm Hg. Another 3% had BP in excess of 160/100 mm Hg. No controversy exists regarding pharmacotherapy in either of these groups: It’s not warranted in the former, essential in the latter.

Another 3,000 individuals had what the ACC/AHA guidelines define as elevated BP, meaning 120-129/<80 mm Hg, or low-risk stage 1 hypertension of 130-139/80-89 mm Hg and a 10-year ASCVD risk score of less than 10%. Initiation of antihypertensive medication in these groups is not recommended in the guidelines. Yet 36% of these individuals had at least one positive cardiac biomarker. And here’s the eye-opening finding: Notably, the 10-year cardiovascular event incidence rate in this biomarker group not currently recommended for antihypertensive pharmacotherapy was 11%, more than double the 4.6% rate in the biomarker-negative group, which in turn was comparable to the 3.8% in the normal BP participants.

Antihypertensive therapy was recommended according to the guidelines in 20% of the total study population, comprising patients with stage 1 hypertension who had an ASCVD risk score of 10% or more as well as those with stage 2 hypertension, defined as BP greater than 140/90 mm Hg but less than 160/100 mm Hg. Forty-eight percent of these subjects were positive for at least one biomarker. Their cardiovascular incidence rate was 15.1%, compared to the 7.9% rate in biomarker-negative individuals.

The estimated number-needed-to-treat (NNT) with intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy to a target systolic BP of less than 120 mm Hg, as in SPRINT, to prevent one cardiovascular event in individuals not currently guideline-recommended for antihypertensive medications was 86 in those who were biomarker-negative. The NNT dropped to 36 in the biomarker-positive subgroup, a far more attractive figure that suggests a reasonable likelihood of benefit from intensive blood pressure control, in Dr. Pandey’s view.

Similarly, among individuals currently recommended for pharmacotherapy initiation, the NNTs were 49 if biomarker-negative, improving to 26 in those positive for one or both biomarkers, which was comparable to the NNT of 22 in the group with blood pressures greater than 160/100 mm Hg. The NNT of 49 in the biomarker-negative subgroup is in a borderline gray zone warranting individualized shared decision-making regarding pharmacotherapy, Dr. Pandey said.

In this study, an elevated hs-cTnT was defined as 6 ng/L or more, while an elevated NT-proBNP was considered to be at least 100 pg/mL.

“It’s noteworthy that the degree of elevation in hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP which were observed in our study were pretty subtle and much below the threshold used for diagnosis of ischemic events or heart failure. Thus, these elevations were largely representative of subtle chronic injury and not acute events,” according to the cardiologist.

One audience member asked if the elevated biomarkers could simply be a surrogate for longer duration of exposure of the heart to high BP. Sure, Dr. Pandey replied, pointing to the 6-year greater average age of the biomarker-positive participants.

“It is likely that biomarker-positive status is capturing the culmination of longstanding exposure. But the thing about hypertension is there are no symptoms that can signal to the patient or the doctor that they have this disease, so testing for the biomarkers can actually capture the high-risk group that may have had hypertension for a long duration but now needs to be treated in order to prevent the advance of downstream adverse events,” he said.

Dr. Pandey reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Pandey A. AHA 2019 Abstract EP.AOS.521.141

PHILADELPHIA – Incorporation of cardiac biomarkers into current guideline-based decision-making regarding initiation of antihypertensive medication in patients with previously untreated mild or moderate high blood pressure leads to more appropriate and selective matching of intensive blood pressure control with true patient risk, Ambarish Pandey, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

That’s because the 2017 American College of Cardiology/AHA blood pressure guidelines recommend incorporating the ACC/AHA 10-Year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Calculator into decision making as to whether to start antihypertensive drug therapy in patients with stage 1 hypertension (130-139/80-89 mm Hg), but the risk calculator doesn’t account for the risk of heart failure.

Yet by far the greatest benefit of intensive BP lowering is in reducing the risk of developing heart failure, as demonstrated in the landmark SPRINT trial, which showed that intensive BP lowering achieved much greater risk reduction in new-onset heart failure than in atherosclerotic cardiovascular events.

Thus, there’s a need for better strategies to guide antihypertensive therapy. And therein lies the rationale for incorporating into the risk assessment an individual’s values for N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which reflects chronic myocardial stress, and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), which when elevated signals myocardial injury.

“Cardiac biomarkers are intermediate phenotypes from hypertension to future cardiovascular events. They can identify individuals at increased risk for atherosclerotic events, and at even higher risk for heart failure events,” explained Dr. Pandey, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

He presented a study of 12,987 participants in three major U.S. cohort studies: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Dallas Heart Study. At baseline, none of the participants were on antihypertensive therapy or had known cardiovascular disease. During 10 years of prospective follow-up, 825 of them experienced a first cardiovascular disease event: 251 developed heart failure and 574 had an MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death. Dr. Pandey and his coworkers calculated the cardiovascular event incidence rate and number-needed-to-treat with intensive antihypertensive drug therapy to prevent a first cardiovascular disease event on the basis of whether patients in the various BP categories were positive or negative for one or more biomarkers.

The results

Fifty-four percent of subjects had normal BP, defined in the guidelines as less than 120/80 mm Hg. Another 3% had BP in excess of 160/100 mm Hg. No controversy exists regarding pharmacotherapy in either of these groups: It’s not warranted in the former, essential in the latter.

Another 3,000 individuals had what the ACC/AHA guidelines define as elevated BP, meaning 120-129/<80 mm Hg, or low-risk stage 1 hypertension of 130-139/80-89 mm Hg and a 10-year ASCVD risk score of less than 10%. Initiation of antihypertensive medication in these groups is not recommended in the guidelines. Yet 36% of these individuals had at least one positive cardiac biomarker. And here’s the eye-opening finding: Notably, the 10-year cardiovascular event incidence rate in this biomarker group not currently recommended for antihypertensive pharmacotherapy was 11%, more than double the 4.6% rate in the biomarker-negative group, which in turn was comparable to the 3.8% in the normal BP participants.

Antihypertensive therapy was recommended according to the guidelines in 20% of the total study population, comprising patients with stage 1 hypertension who had an ASCVD risk score of 10% or more as well as those with stage 2 hypertension, defined as BP greater than 140/90 mm Hg but less than 160/100 mm Hg. Forty-eight percent of these subjects were positive for at least one biomarker. Their cardiovascular incidence rate was 15.1%, compared to the 7.9% rate in biomarker-negative individuals.

The estimated number-needed-to-treat (NNT) with intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy to a target systolic BP of less than 120 mm Hg, as in SPRINT, to prevent one cardiovascular event in individuals not currently guideline-recommended for antihypertensive medications was 86 in those who were biomarker-negative. The NNT dropped to 36 in the biomarker-positive subgroup, a far more attractive figure that suggests a reasonable likelihood of benefit from intensive blood pressure control, in Dr. Pandey’s view.

Similarly, among individuals currently recommended for pharmacotherapy initiation, the NNTs were 49 if biomarker-negative, improving to 26 in those positive for one or both biomarkers, which was comparable to the NNT of 22 in the group with blood pressures greater than 160/100 mm Hg. The NNT of 49 in the biomarker-negative subgroup is in a borderline gray zone warranting individualized shared decision-making regarding pharmacotherapy, Dr. Pandey said.

In this study, an elevated hs-cTnT was defined as 6 ng/L or more, while an elevated NT-proBNP was considered to be at least 100 pg/mL.

“It’s noteworthy that the degree of elevation in hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP which were observed in our study were pretty subtle and much below the threshold used for diagnosis of ischemic events or heart failure. Thus, these elevations were largely representative of subtle chronic injury and not acute events,” according to the cardiologist.

One audience member asked if the elevated biomarkers could simply be a surrogate for longer duration of exposure of the heart to high BP. Sure, Dr. Pandey replied, pointing to the 6-year greater average age of the biomarker-positive participants.

“It is likely that biomarker-positive status is capturing the culmination of longstanding exposure. But the thing about hypertension is there are no symptoms that can signal to the patient or the doctor that they have this disease, so testing for the biomarkers can actually capture the high-risk group that may have had hypertension for a long duration but now needs to be treated in order to prevent the advance of downstream adverse events,” he said.

Dr. Pandey reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Pandey A. AHA 2019 Abstract EP.AOS.521.141

PHILADELPHIA – Incorporation of cardiac biomarkers into current guideline-based decision-making regarding initiation of antihypertensive medication in patients with previously untreated mild or moderate high blood pressure leads to more appropriate and selective matching of intensive blood pressure control with true patient risk, Ambarish Pandey, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

That’s because the 2017 American College of Cardiology/AHA blood pressure guidelines recommend incorporating the ACC/AHA 10-Year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) Risk Calculator into decision making as to whether to start antihypertensive drug therapy in patients with stage 1 hypertension (130-139/80-89 mm Hg), but the risk calculator doesn’t account for the risk of heart failure.

Yet by far the greatest benefit of intensive BP lowering is in reducing the risk of developing heart failure, as demonstrated in the landmark SPRINT trial, which showed that intensive BP lowering achieved much greater risk reduction in new-onset heart failure than in atherosclerotic cardiovascular events.

Thus, there’s a need for better strategies to guide antihypertensive therapy. And therein lies the rationale for incorporating into the risk assessment an individual’s values for N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which reflects chronic myocardial stress, and high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), which when elevated signals myocardial injury.

“Cardiac biomarkers are intermediate phenotypes from hypertension to future cardiovascular events. They can identify individuals at increased risk for atherosclerotic events, and at even higher risk for heart failure events,” explained Dr. Pandey, a cardiologist at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

He presented a study of 12,987 participants in three major U.S. cohort studies: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities (ARIC) study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and the Dallas Heart Study. At baseline, none of the participants were on antihypertensive therapy or had known cardiovascular disease. During 10 years of prospective follow-up, 825 of them experienced a first cardiovascular disease event: 251 developed heart failure and 574 had an MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death. Dr. Pandey and his coworkers calculated the cardiovascular event incidence rate and number-needed-to-treat with intensive antihypertensive drug therapy to prevent a first cardiovascular disease event on the basis of whether patients in the various BP categories were positive or negative for one or more biomarkers.

The results

Fifty-four percent of subjects had normal BP, defined in the guidelines as less than 120/80 mm Hg. Another 3% had BP in excess of 160/100 mm Hg. No controversy exists regarding pharmacotherapy in either of these groups: It’s not warranted in the former, essential in the latter.

Another 3,000 individuals had what the ACC/AHA guidelines define as elevated BP, meaning 120-129/<80 mm Hg, or low-risk stage 1 hypertension of 130-139/80-89 mm Hg and a 10-year ASCVD risk score of less than 10%. Initiation of antihypertensive medication in these groups is not recommended in the guidelines. Yet 36% of these individuals had at least one positive cardiac biomarker. And here’s the eye-opening finding: Notably, the 10-year cardiovascular event incidence rate in this biomarker group not currently recommended for antihypertensive pharmacotherapy was 11%, more than double the 4.6% rate in the biomarker-negative group, which in turn was comparable to the 3.8% in the normal BP participants.

Antihypertensive therapy was recommended according to the guidelines in 20% of the total study population, comprising patients with stage 1 hypertension who had an ASCVD risk score of 10% or more as well as those with stage 2 hypertension, defined as BP greater than 140/90 mm Hg but less than 160/100 mm Hg. Forty-eight percent of these subjects were positive for at least one biomarker. Their cardiovascular incidence rate was 15.1%, compared to the 7.9% rate in biomarker-negative individuals.

The estimated number-needed-to-treat (NNT) with intensive blood pressure–lowering therapy to a target systolic BP of less than 120 mm Hg, as in SPRINT, to prevent one cardiovascular event in individuals not currently guideline-recommended for antihypertensive medications was 86 in those who were biomarker-negative. The NNT dropped to 36 in the biomarker-positive subgroup, a far more attractive figure that suggests a reasonable likelihood of benefit from intensive blood pressure control, in Dr. Pandey’s view.

Similarly, among individuals currently recommended for pharmacotherapy initiation, the NNTs were 49 if biomarker-negative, improving to 26 in those positive for one or both biomarkers, which was comparable to the NNT of 22 in the group with blood pressures greater than 160/100 mm Hg. The NNT of 49 in the biomarker-negative subgroup is in a borderline gray zone warranting individualized shared decision-making regarding pharmacotherapy, Dr. Pandey said.

In this study, an elevated hs-cTnT was defined as 6 ng/L or more, while an elevated NT-proBNP was considered to be at least 100 pg/mL.

“It’s noteworthy that the degree of elevation in hs-cTnT and NT-proBNP which were observed in our study were pretty subtle and much below the threshold used for diagnosis of ischemic events or heart failure. Thus, these elevations were largely representative of subtle chronic injury and not acute events,” according to the cardiologist.

One audience member asked if the elevated biomarkers could simply be a surrogate for longer duration of exposure of the heart to high BP. Sure, Dr. Pandey replied, pointing to the 6-year greater average age of the biomarker-positive participants.

“It is likely that biomarker-positive status is capturing the culmination of longstanding exposure. But the thing about hypertension is there are no symptoms that can signal to the patient or the doctor that they have this disease, so testing for the biomarkers can actually capture the high-risk group that may have had hypertension for a long duration but now needs to be treated in order to prevent the advance of downstream adverse events,” he said.

Dr. Pandey reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Pandey A. AHA 2019 Abstract EP.AOS.521.141

REPORTING FROM AHA 2019

FDA advisers set high bar for new opioids

During an opioid-addiction epidemic, can any new opioid pain drug meet prevailing safety demands to gain regulatory approval?

On Jan. 14 and 15, a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee voted virtually unanimously against two new opioid formulations and evenly split for and against a third; the 2 days of data and discussion showed how high a bar new opioids face these days for getting onto the U.S. market.

The bar’s height is very understandable given how many Americans have become addicted to opioids over the past decade, more often than not by accident while using pain medications as they believed they had been directed, said experts during the sessions held on the FDA’s campus in White Oak, Md.

Among the many upshots of the opioid crisis, the meetings held to discuss these three contender opioids highlighted the bitter irony confronting attempts to bring new, safer opioids to the U.S. market: While less abusable pain-relief medications that still harness the potent analgesic power of mu opioid receptor agonists are desperately desired, new agents in this space now receive withering scrutiny over their safeguards against misuse and abuse, and over whether they add anything meaningfully new to what’s already available. While these demands seem reasonable, perhaps even essential, it’s unclear whether any new opioid-based pain drugs will ever fully meet the safety that researchers, clinicians, and the public now seek.

A special FDA advisory committee that combined the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee with members of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee considered the application for three different opioid drugs from three separate companies. None received a clear endorsement. Oxycodegol, a new type of orally delivered opioid molecule engineered to slow brain entry and thereby delay an abuser’s high, got voted down without any votes in favor and 27 votes against agency approval. Aximris XR, an extended-release oxycodone formulation that successfully deterred intravenous abuse but had no deterrence efficacy for intranasal or oral abuse failed by a 2-24 vote against. The third agent, CTC, a novel formulation of the schedule IV opioid tramadol with the NSAID celecoxib designed to be analgesic but with limited opioid-abuse appeal, came the closest to meaningful support with a tied 13-13 vote from advisory committee members for and against agency approval. FDA staff takes advisory committee opinions and votes into account when making their final decisions about drug marketing approvals.

In each case, the committee members, mostly the same roster assembled for each of the three agents, identified specific concerns with the data purported to show each drug’s safety and efficacy. But the gathered experts and consumer representatives also consistently cited holistic challenges to approving new opioids and the stiffer criteria these agents face amid a continuing wave of opioid misuse and abuse.

“In the context of the public health issues, we don’t want to be perceived in any way of taking shortcuts,” said Linda S. Tyler, PharmD,, an advisory committee member and professor of pharmacy and chief pharmacy officer at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “There is no question that for a new product to come to market in this space it needs to add to what’s on the market, meet a high bar, and provide advantages compared with what’s already on the market,” she said.

Tramadol plus celecoxib gains some support

The proposed combined formulation of tramadol and celecoxib came closest to meeting that bar, as far as the advisory committee was concerned, coming away with 13 votes favoring approval to match 13 votes against. The premise behind this agent, know as CTC (cocrystal of tramadol and celecoxib), was that it combined a modest dose (44 mg) of the schedule IV opioid tramadol with a 56-mg dose of celecoxib in a twice-daily pill. Eugene R. Viscusi, MD, professor of anesthesiology and director of acute pain management at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia and a speaker at the session on behalf of the applicant company, spelled out the rationale behind CTC: “We are caught in a dilemma. We need to reduce opioid use, but we also need to treat pain. We have an urgent need to have pain treatment options that are effective but have low potential for abuse and dependence. We are looking at multimodal analgesia, that uses combination of agents, recognizing that postoperative pain is a mixed pain syndrome. Multimodal pain treatments are now considered standard care. We want to minimize opioids to the lowest dose possible to produce safe analgesia. Tramadol is the least-preferred opioid for abuse,” and is rated as schedule IV, the U.S. designation for drugs considered to have a low level of potential for causing abuse or dependence. “Opioids used as stand-alone agents have contributed to the current opioid crisis,” Dr. Viscusi told the committee.

In contrast to tramadol’s schedule IV status, the mainstays of recent opioid pain therapy have been hydrocodone and oxycodone, schedule II opioids rated as having a “high potential for abuse.”

Several advisory committee members agreed that CTC minimized patient exposure to an opioid. “This drug isn’t even tramadol; it’s tramadol light. It has about as low a dose [of an opioid] as you can have and still have a drug,” said member Lee A. Hoffer, PhD, a medical anthropologist at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, who studies substance use disorders. “All opioids are dangerous, even at a low dose, but there is a linear relationship based on potency, so if we want to have an opioid for acute pain, I’d like it to have the lowest morphine milligram equivalent possible. The ideal is no opioids, but that is not what happens,” he said. The CTC formulation delivers 17.6 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per pill, the manufacturer’s representatives said. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a “relatively low” daily opioid dose as 20-50 MME.

Some committee members hailed the CTC formulation as a meaningful step toward cutting opioid consumption.

“We may be very nervous about abuse of scheduled opioids, but a schedule IV opioid in an opioid-sparing formulation is as good as it gets in 2020,” said committee member Kevin L. Zacharoff, MD, a pain medicine specialist at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. “Any opioid has potential for abuse, but this is a safer alternative to the schedule II drugs. There is less public health risk with this,” said committee member Sherif Zaafran, MD, a Houston anesthesiologist. “This represents an incremental but important approach to addressing the opioid crisis, especially if used to replace schedule II opioids,” said Brandon D.L. Marshall, PhD, an epidemiologist and substance abuse researcher at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

But despite agreement that CTC represented a new low in the MME of an opioid given to patients, several committee members still saw the formulation as problematic by introducing any opioid, no matter how small the dose.

“The landscape of tramadol use and prescribing is evolving. There’s been an exponential upturn in tramadol prescribing. It’s perceived [as] safer, but it’s not completely safe. Will this change tramadol abuse and open the door to abuse of other opioids? This is what got us into trouble with opioids in the first place. Patients start with a prescription opioid that they perceive is safe. Patients don’t start with oxycodone or heroin. They start with drugs that are believed to be safe. I feel this combination has less risk for abuse, but I’m worried that it would produce a false sense of security for tolerability and safety,” said committee member Maryann E. Amirshahi, MD, a medical toxicologist at Georgetown University and MedStar Health in Washington.

Several other committee members returned to this point throughout the 2 days of discussions: The majority of Americans who have become hooked on opioids reached that point by taking an opioid pain medication for a legitimate medical reason and using the drug the way they had understood they should.

“I’m most concerned about unintentional misuse leading to addiction and abuse. Most people with an opioid addiction got it inadvertently, misusing it by mistake,” said committee member Suzanne B. Robotti, a consumer representative and executive director of DES Action USA. “I’m concerned about approving an opioid, even an opioid with a low abuse history, without a clearer picture of the human abuse potential data and what would happen if this drug were abused,” she added, referring to the proposed CTC formulation.

“All the patients I work with started [their opioid addiction] as pain patients,” Dr. Hoffer said.

“The most common use and abuse of opioids is orally. We need to avoid having patients who use the drug as prescribed and still end up addicted,” said committee member Friedhelm Sandbrink, MD, a neurologist and director of pain management at the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Washington.

What this means, said several panelists, is functionally clamping down a class-wide lid on new opioids. “The way to reduce deaths from abuse is to reduce addiction, and to have an impact you need to reduce opioid exposure.” said committee member Sonia Hernandez-Diaz, MD, professor of epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston.

“In this opioid crisis, we ask for data that we wouldn’t ordinarily ask for. I feel there are unanswered questions about the abuse potential [of CTC]. We have seen a recent reduction in oxycodone use, which is great, but also an increase in tramadol use. We should not be fooled. Tramadol is an opioid, even if it’s schedule IV,” Dr. Tyler said.

Two other opioids faced greater opposition

The other two agents that the committee considered received much less support and sharper skepticism. The application for Aximris XR, an extended release form of oxycodone with a purported abuse-deterrent formulation (ADF) that relies on being difficult to extract for intravenous use as well as possibly having effective deterrence mechanisms for other forms of abuse. But FDA staffers reported that the only effective deterrence they could document was against manipulation for intravenous use, making Aximris XR the first opioid seeking ADF labeling based on deterrence to a single delivery route. This led several committee members, as well as the FDA, to comment on the clinical meaningfulness of ADF for one route. So far, the FDA approved ADF labeling for seven opioids, most notably OxyContin, an extended-release oxycodone with the biggest share of the U.S. market for opioids with ADF labeling.

“For ADF, we label based on what we expect from the premarket data. We don’t really know how that translates into what happens once the drug is on the market. Every company with an ADF in their label is required to do postmarketing studies on the abuse routes that are supposed to be deterred. We see shifts to other routes. Assessment of ADF is incredibly challenging, both scientifically and logistically, because there has not been a lot of uptake of these products, for a variety of reasons,” said Judy Staffa, PhD, associate director for Public Health Initiatives in the Office of Surveillance & Epidemiology in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. The company that markets OxyContin has been the first to submit to the FDA all of its required postmarketing data on ADF efficacy, and the agency is now reviewing this filing, Dr. Staffa said.

The data presented for Aximris XR appeared to generally fail to convince committee members that it provided a meaningful addition to the range of opioids with ADF designations already available, which meant that their decision mostly came down to whether they felt it made sense to bring a me-too opioid to the U.S. market. Their answer was mostly no.

“In the end, it’s another opioid, and I’m not sure we need another opioid,” said committee member Lonnie K. Zeltzer, MD, professor of pediatrics, anesthesiology, psychiatry, and biobehavioral sciences and director of pediatric pain at the University of California, Los Angeles “There are so many options for patients and for people who abuse these drug. I don’t see this formulation as having a profound impact, but I’m very concerned about adding more prescription opioids,” said Martin Garcia-Bunuel, MD, deputy chief of staff for the VA Maryland Health Care System in Baltimore. Another concern of some committee members was that ADF remains a designation with an uncertain meaning, pending the FDA’s analysis of the OxyContin data.

“At the end of the day, we don’t know whether any of the [ADF] stuff makes a difference,” noted Steve B. Meisel, PharmD, system director of medication safety for M Health Fairview in Minneapolis and a committee member,

The third agent, oxycodegol, a molecule designed to pass more slowly across the blood-brain barrier because of an attached polyethylene glycol chain that’s supposed to prevent a rapid high after ingestion and hence cut abuse potential. It received unanimous committee rejection, primarily because its safety and efficacy evidence had so many holes, but the shadow of opioid abuse permeated the committee’s discussion.

“One dogma in the abuse world is that slowing entry into the brain reduces abuse potential, but the opioid crisis showed that this is not the only factor. Some people have become addicted to slow-acting drugs. The abuse potential of this drug, oxycodegol, needs to be considered given where we’ve been with the opioid crisis,” said Jane B. Acri, PhD, chief of the Medications Discovery and Toxicology Branch of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

“During the opioid epidemic, do we want to approve more opioids? If the [pain] efficacy is about the same as oxycodone, is better safety or abuse potential a reason to approve it? We need guidance [from the FDA] about what is ‘better enough.’ No opioid will ever be perfect; there will always be abuse and misuse. But what is good enough to justify bringing another opioid onto the market? What is a good enough improvement? I don’t have an answer,” Dr. Hernandez-Diaz said.

Adviser comments showed that the continued threat of widespread opioid addiction has cooled prospects for new opioid approvals by making FDA advisers skittish over how to properly score the incremental value of a new opioid.

“Do we need to go back to the drawing board on how we make decisions on exposing the American public to these kinds of agents?” Dr. Garcia-Bunuel asked. “I don’t think we have the tools to make these decisions.”

During an opioid-addiction epidemic, can any new opioid pain drug meet prevailing safety demands to gain regulatory approval?

On Jan. 14 and 15, a Food and Drug Administration advisory committee voted virtually unanimously against two new opioid formulations and evenly split for and against a third; the 2 days of data and discussion showed how high a bar new opioids face these days for getting onto the U.S. market.

The bar’s height is very understandable given how many Americans have become addicted to opioids over the past decade, more often than not by accident while using pain medications as they believed they had been directed, said experts during the sessions held on the FDA’s campus in White Oak, Md.

Among the many upshots of the opioid crisis, the meetings held to discuss these three contender opioids highlighted the bitter irony confronting attempts to bring new, safer opioids to the U.S. market: While less abusable pain-relief medications that still harness the potent analgesic power of mu opioid receptor agonists are desperately desired, new agents in this space now receive withering scrutiny over their safeguards against misuse and abuse, and over whether they add anything meaningfully new to what’s already available. While these demands seem reasonable, perhaps even essential, it’s unclear whether any new opioid-based pain drugs will ever fully meet the safety that researchers, clinicians, and the public now seek.

A special FDA advisory committee that combined the Anesthetic and Analgesic Drug Products Advisory Committee with members of the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee considered the application for three different opioid drugs from three separate companies. None received a clear endorsement. Oxycodegol, a new type of orally delivered opioid molecule engineered to slow brain entry and thereby delay an abuser’s high, got voted down without any votes in favor and 27 votes against agency approval. Aximris XR, an extended-release oxycodone formulation that successfully deterred intravenous abuse but had no deterrence efficacy for intranasal or oral abuse failed by a 2-24 vote against. The third agent, CTC, a novel formulation of the schedule IV opioid tramadol with the NSAID celecoxib designed to be analgesic but with limited opioid-abuse appeal, came the closest to meaningful support with a tied 13-13 vote from advisory committee members for and against agency approval. FDA staff takes advisory committee opinions and votes into account when making their final decisions about drug marketing approvals.

In each case, the committee members, mostly the same roster assembled for each of the three agents, identified specific concerns with the data purported to show each drug’s safety and efficacy. But the gathered experts and consumer representatives also consistently cited holistic challenges to approving new opioids and the stiffer criteria these agents face amid a continuing wave of opioid misuse and abuse.

“In the context of the public health issues, we don’t want to be perceived in any way of taking shortcuts,” said Linda S. Tyler, PharmD,, an advisory committee member and professor of pharmacy and chief pharmacy officer at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. “There is no question that for a new product to come to market in this space it needs to add to what’s on the market, meet a high bar, and provide advantages compared with what’s already on the market,” she said.

Tramadol plus celecoxib gains some support

The proposed combined formulation of tramadol and celecoxib came closest to meeting that bar, as far as the advisory committee was concerned, coming away with 13 votes favoring approval to match 13 votes against. The premise behind this agent, know as CTC (cocrystal of tramadol and celecoxib), was that it combined a modest dose (44 mg) of the schedule IV opioid tramadol with a 56-mg dose of celecoxib in a twice-daily pill. Eugene R. Viscusi, MD, professor of anesthesiology and director of acute pain management at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia and a speaker at the session on behalf of the applicant company, spelled out the rationale behind CTC: “We are caught in a dilemma. We need to reduce opioid use, but we also need to treat pain. We have an urgent need to have pain treatment options that are effective but have low potential for abuse and dependence. We are looking at multimodal analgesia, that uses combination of agents, recognizing that postoperative pain is a mixed pain syndrome. Multimodal pain treatments are now considered standard care. We want to minimize opioids to the lowest dose possible to produce safe analgesia. Tramadol is the least-preferred opioid for abuse,” and is rated as schedule IV, the U.S. designation for drugs considered to have a low level of potential for causing abuse or dependence. “Opioids used as stand-alone agents have contributed to the current opioid crisis,” Dr. Viscusi told the committee.

In contrast to tramadol’s schedule IV status, the mainstays of recent opioid pain therapy have been hydrocodone and oxycodone, schedule II opioids rated as having a “high potential for abuse.”