User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

The branching tree of hospital medicine

Diversity of training backgrounds

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

Diversity of training backgrounds

Diversity of training backgrounds

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

You’ve probably heard of a “nocturnist,” but have you ever heard of a “weekendist?”

The field of hospital medicine (HM) has evolved dramatically since the term “hospitalist” was introduced in the literature in 1996.1 There is a saying in HM that “if you know one HM program, you know one HM program,” alluding to the fact that every HM program is unique. The diversity of individual HM programs combined with the overall evolution of the field has expanded the range of jobs available in HM.

The nomenclature of adding an -ist to the end of the specific roles (e.g., nocturnist, weekendist) has become commonplace. These roles have developed with the increasing need for day and night staffing at many hospitals secondary to increased and more complex patients, less availability of residents because of work hour restrictions, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) rules that require overnight supervision of residents

Additionally, the field of HM increasingly includes physicians trained in internal medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, and medicine-pediatrics (med-peds). In this article, we describe the variety of roles available to trainees joining HM and the multitude of different training backgrounds hospitalists come from.

Nocturnists

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report notes that 76.1% of adult-only HM groups have nocturnists, hospitalists who work primarily at night to admit and to provide coverage for admitted patients.2 Nocturnists often provide benefit to the rest of their hospitalist group by allowing fewer required night shifts for those that prefer to work during the day.

Nocturnists may choose a nighttime schedule for several reasons, including the ability to be home more during the day. They also have the potential to work fewer total hours or shifts while still earning a similar or increased income, compared with predominantly daytime hospitalists, increasing their flexibility to pursue other interests. These nocturnists become experts in navigating the admission process and responding to inpatient emergencies often with less support when compared with daytime hospitalists.

In addition to career nocturnist work, nocturnist jobs can be a great fit for those residency graduates who are undecided about fellowship and enjoy the acuity of inpatient medicine. It provides an opportunity to hone their clinical skill set prior to specialized training while earning an attending salary, and offers flexible hours which may allow for research or other endeavors. In academic centers, nocturnist educational roles take on a different character as well and may involve more 1:1 educational experiences. The role of nocturnists as educators is expanding as ACGME rules call for more oversight and educational opportunities for residents who are working at night.

However, challenges exist for nocturnists, including keeping abreast of new changes in their HM groups and hospital systems and engaging in quality initiatives, given that most meetings occur during the day. Additionally, nocturnists must adapt to sleeping during the day, potentially getting less sleep then they would otherwise and being “off cycle” with family and friends. For nocturnists raising children, being off cycle may be advantageous as it can allow them to be home with their children after school.

Weekendists

Another common hospitalist role is the weekendist, hospitalists who spend much of their clinical time preferentially working weekends. Similar to nocturnists, weekendists provide benefit to their hospitalist group by allowing others to have more weekends off.

Weekendists may prefer working weekends because of fewer total shifts or hours and/or higher compensation per shift. Additionally, weekendists have the flexibility to do other work on weekdays, such as research or another hospitalist job. For those that do nonclinical work during the week, a weekendist position may allow them to keep their clinical skills up to date. However, weekendists may face intense clinical days with a higher census because of fewer hospitalists rounding on the weekends.

Weekendists must balance having more potential time available during the weekdays but less time on the weekends to devote to family and friends. Furthermore, weekendists may feel less engaged with nonclinical opportunities, including quality improvement, educational offerings, and teaching opportunities.

SNFists

With increasing emphasis on transitions of care and the desire to avoid readmission penalties, some hospitalists have transitioned to work partly or primarily in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) and have been referred to as “SNFists.” Some of these hospitalists may split their clinical time between SNFs and acute care hospitals, while others may work exclusively at SNFs.

SNFists have the potential to be invaluable in improving transitions of care after discharge to post–acute care facilities because of increased provider presence in these facilities, comfort with medically complex patients, and appreciation of government regulations.4 SNFists may face potential challenges of needing to staff more than one post–acute care hospital and of having less resources available, compared with an acute care hospital.

Specific specialty hospitalists

For a variety of reasons including clinical interest, many hospitalists have become specialized with regards to their primary inpatient population. Some hospitalists spend the majority of their clinical time on a specific service in the hospital, often working closely with the subspecialist caring for that patient. These hospitalists may focus on hematology, oncology, bone-marrow transplant, neurology, cardiology, surgery services, or critical care, among others. Hospitalists focused on a specific service often become knowledge experts in that specialty. Conversely, by focusing on a specific service, certain pathologies may be less commonly seen, which may narrow the breadth of the hospital medicine job.

Hospitalist training

Internal medicine hospitalists may be the most common hospitalists encountered in many hospitals and at each Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference, but there has also been rapid growth in hospitalists from other specialties and backgrounds.

Family medicine hospitalists are a part of 64.9% of HM groups and about 9% of family medicine graduates are choosing HM as a career path.2,3 Most family medicine hospitalists work in adult HM groups, but some, particularly in rural or academic settings, care for pediatric, newborn, and/or maternity patients. Similarly, pediatric hospitalists have become entrenched at many hospitals where children are admitted. These pediatric hospitalists, like adult hospitalists, may work in a variety of different clinical roles including in EDs, newborn nurseries, and inpatient wards or ICUs; they may also provide consult, sedation, or procedural services.

Med-peds hospitalists that split time between internal medicine and pediatrics are becoming more commonplace in the field. Many work at academic centers where they often work on each side separately, doing the same work as their internal medicine or pediatrics colleagues, and then switching to the other side after a period of time. Some centers offer unique roles for med-peds hospitalists including working on adult consult teams in children’s hospitals, where they provide consult care to older patients that may still receive their care at a children’s hospital. There are also nonacademic hospitals that primarily staff med-peds hospitalists, where they can provide the full spectrum of care from the newborn nursery to the inpatient pediatric and adult wards.

Hospital medicine is a young field that is constantly changing with new and developing roles for hospitalists from a wide variety of backgrounds. Stick around to see which “-ist” will come next in HM.

Dr. Hall is a med-peds hospitalist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Sanyal-Dey is an academic hospitalist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center and the University of California, San Francisco, where she is the director of clinical operations, and director of the faculty inpatient service. Dr. Chang is associate professor and interprofessional education thread director (MD curriculum) at Washington University, St. Louis. Dr. Kwan is a hospitalist at the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System and associate professor at the University of California, San Diego. He is the chair of SHM’s Physicians in Training committee. Dr. Seymour is family medicine hospitalist education director at the University of Massachusetts Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, and associate professor at the University of Massachusetts.

References

1. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The Emerging Role of “Hospitalists” in the American Health Care System. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-7.

2. 2018 State of Hospital Medicine Report. Philadelphia: Society of Hospital Medicine, 2018.

3. Weaver SP, Hill J. Academician Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding the Use of Hospitalists: A CERA Study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):357-61.

4. Teno JM et al. Temporal Trends in the Numbers of Skilled Nursing Facility Specialists From 2007 Through 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(9):1376-8.

Improving sepsis-related outcomes

Early diagnosis a key goal

Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disease among patients in hospitals, and it’s the subject of a recent quality improvement study in the Journal for Healthcare Quality.

“The number of cases per year has been increasing in the U.S., and it is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals,” said lead author M. Courtney Hughes, PhD, of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb.

But early identification of symptoms can be complex and difficult for clinicians, meaning there’s a continuing need for research studies examining sepsis identification and prevention. “The purpose of this study was to examine a quality improvement project that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education at an integrated health care system in the Midwest,” she said.

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers examined data from three health systems to determine the impact of a 10-month sepsis quality improvement program that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education. The results showed that, compared with the control group, the intervention group significantly decreased length of stay and costs per stay.

“One way to improve sepsis health outcomes and decrease costs may be for hospitals to implement a sepsis quality improvement program,” Dr. Hughes said. “Also, providing sepsis performance data and education to hospital providers and administrators can arm staff with the knowledge and tools necessary for improving processes and performance related to sepsis.”

Dr. Hughes said that she hopes this work will encourage hospitalists to seek sepsis-related performance data and training. “By doing so, they may help achieve earlier diagnosis of sepsis cases and initiation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle.”

Reference

Hughes MC et al. A quality improvement project to improve sepsis-related outcomes at an integrated healthcare system. J Healthc Qual. Published online 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000193.

Early diagnosis a key goal

Early diagnosis a key goal

Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disease among patients in hospitals, and it’s the subject of a recent quality improvement study in the Journal for Healthcare Quality.

“The number of cases per year has been increasing in the U.S., and it is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals,” said lead author M. Courtney Hughes, PhD, of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb.

But early identification of symptoms can be complex and difficult for clinicians, meaning there’s a continuing need for research studies examining sepsis identification and prevention. “The purpose of this study was to examine a quality improvement project that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education at an integrated health care system in the Midwest,” she said.

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers examined data from three health systems to determine the impact of a 10-month sepsis quality improvement program that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education. The results showed that, compared with the control group, the intervention group significantly decreased length of stay and costs per stay.

“One way to improve sepsis health outcomes and decrease costs may be for hospitals to implement a sepsis quality improvement program,” Dr. Hughes said. “Also, providing sepsis performance data and education to hospital providers and administrators can arm staff with the knowledge and tools necessary for improving processes and performance related to sepsis.”

Dr. Hughes said that she hopes this work will encourage hospitalists to seek sepsis-related performance data and training. “By doing so, they may help achieve earlier diagnosis of sepsis cases and initiation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle.”

Reference

Hughes MC et al. A quality improvement project to improve sepsis-related outcomes at an integrated healthcare system. J Healthc Qual. Published online 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000193.

Sepsis is a leading cause of death and disease among patients in hospitals, and it’s the subject of a recent quality improvement study in the Journal for Healthcare Quality.

“The number of cases per year has been increasing in the U.S., and it is the most expensive condition treated in U.S. hospitals,” said lead author M. Courtney Hughes, PhD, of Northern Illinois University in DeKalb.

But early identification of symptoms can be complex and difficult for clinicians, meaning there’s a continuing need for research studies examining sepsis identification and prevention. “The purpose of this study was to examine a quality improvement project that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education at an integrated health care system in the Midwest,” she said.

In a retrospective analysis, the researchers examined data from three health systems to determine the impact of a 10-month sepsis quality improvement program that consisted of clinical alerts, audit and feedback, and staff education. The results showed that, compared with the control group, the intervention group significantly decreased length of stay and costs per stay.

“One way to improve sepsis health outcomes and decrease costs may be for hospitals to implement a sepsis quality improvement program,” Dr. Hughes said. “Also, providing sepsis performance data and education to hospital providers and administrators can arm staff with the knowledge and tools necessary for improving processes and performance related to sepsis.”

Dr. Hughes said that she hopes this work will encourage hospitalists to seek sepsis-related performance data and training. “By doing so, they may help achieve earlier diagnosis of sepsis cases and initiation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle.”

Reference

Hughes MC et al. A quality improvement project to improve sepsis-related outcomes at an integrated healthcare system. J Healthc Qual. Published online 2019 Mar 14. doi: 10.1097/JHQ.0000000000000193.

New ASH guideline: VTE prophylaxis after major surgery

ORLANDO – The latest American Society of Hematology guideline on venous thromboembolism (VTE) tackles 30 key questions regarding prophylaxis in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery, according to the chair of the guideline panel, who highlighted 9 of those questions during a special session at the society’s annual meeting.

The clinical practice guideline, published just about a week before the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, focuses mainly on pharmacologic prophylaxis in specific surgical settings, said David R. Anderson, MD, dean of the faculty of medicine of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

“Our guidelines focused upon clinically important symptomatic outcomes, with less emphasis being placed on asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by screening tests,” Dr. Anderson said.

At the special education session, Dr. Anderson highlighted several specific recommendations on prophylaxis in surgical patients.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients experiencing major trauma deemed to be at high risk of bleeding. Its use does reduce risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) by about 10 events per 1,000 patients treated; however, Dr. Anderson said, the panel’s opinion was that this benefit was outweighed by increased risk of major bleeding, at 24 events per 1,000 patients treated.

“We do recommend, however that this risk of bleeding must be reevaluated over the course of recovery of patients, and this may change the decision around this intervention over time,” Dr. Anderson told attendees at the special session.

That’s because pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in surgical patients at low to moderate risk of bleeding. In this scenario, the incremental risk of major bleeding (14 events per 1,000 patients treated) is outweighed by the benefit of the reduction of symptomatic VTE events, according to Dr. Anderson.

When pharmacologic prophylaxis is used, the panel recommends combined prophylaxis – mechanical prophylaxis in addition to pharmacologic prophylaxis – especially in those patients at high or very high risk of VTE. Evidence shows that the combination approach significantly reduces risk of PE, and strongly suggests it may also reduce risk of symptomatic proximal DVT, Dr. Anderson said.

In surgical patients not receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no mechanical prophylaxis, he added. Moreover, in those patients receiving mechanical prophylaxis, the ASH panel recommends use of intermittent compression devices over graduated compression stockings.

The panel comes out against prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter insertion in the guidelines. Dr. Anderson said that the “small reduction” in PE risk seen in observational studies is outweighed by increased risk of DVT, and a resulting trend for increased mortality, associated with insertion of the devices.

“We did not consider other risks of IVC filters such as filter embolization or perforation, which again would be complications that would support our recommendation against routine use of these devices in patients undergoing major surgery,” he said.

In terms of the type of pharmacologic prophylaxis to use, the panel said low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin would be reasonable choices in this setting. Available data do not demonstrate any significant differences between these choices for major clinical outcomes, Dr. Anderson added.

The guideline also addresses duration of pharmacologic prophylaxis, stating that extended prophylaxis – of at least 3 weeks – is favored over short-term prophylaxis, or up to 2 weeks of treatment. The extended approach significantly reduces risk of symptomatic PE and proximal DVT, though most of the supporting data come from studies of major joint arthroplasty and major general surgical procedures for patients with cancer. “We need more studies in other clinical areas to examine this particular question,” Dr. Anderson said.

The guideline on prophylaxis in surgical patients was published in Blood Advances (2019 Dec 3;3[23]:3898-944). Six other ASH VTE guidelines, all published in 2018, covered prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, VTE in pregnancy, optimal anticoagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and pediatric considerations. The guidelines are available on the ASH website.

Dr. Anderson reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The latest American Society of Hematology guideline on venous thromboembolism (VTE) tackles 30 key questions regarding prophylaxis in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery, according to the chair of the guideline panel, who highlighted 9 of those questions during a special session at the society’s annual meeting.

The clinical practice guideline, published just about a week before the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, focuses mainly on pharmacologic prophylaxis in specific surgical settings, said David R. Anderson, MD, dean of the faculty of medicine of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

“Our guidelines focused upon clinically important symptomatic outcomes, with less emphasis being placed on asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by screening tests,” Dr. Anderson said.

At the special education session, Dr. Anderson highlighted several specific recommendations on prophylaxis in surgical patients.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients experiencing major trauma deemed to be at high risk of bleeding. Its use does reduce risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) by about 10 events per 1,000 patients treated; however, Dr. Anderson said, the panel’s opinion was that this benefit was outweighed by increased risk of major bleeding, at 24 events per 1,000 patients treated.

“We do recommend, however that this risk of bleeding must be reevaluated over the course of recovery of patients, and this may change the decision around this intervention over time,” Dr. Anderson told attendees at the special session.

That’s because pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in surgical patients at low to moderate risk of bleeding. In this scenario, the incremental risk of major bleeding (14 events per 1,000 patients treated) is outweighed by the benefit of the reduction of symptomatic VTE events, according to Dr. Anderson.

When pharmacologic prophylaxis is used, the panel recommends combined prophylaxis – mechanical prophylaxis in addition to pharmacologic prophylaxis – especially in those patients at high or very high risk of VTE. Evidence shows that the combination approach significantly reduces risk of PE, and strongly suggests it may also reduce risk of symptomatic proximal DVT, Dr. Anderson said.

In surgical patients not receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no mechanical prophylaxis, he added. Moreover, in those patients receiving mechanical prophylaxis, the ASH panel recommends use of intermittent compression devices over graduated compression stockings.

The panel comes out against prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter insertion in the guidelines. Dr. Anderson said that the “small reduction” in PE risk seen in observational studies is outweighed by increased risk of DVT, and a resulting trend for increased mortality, associated with insertion of the devices.

“We did not consider other risks of IVC filters such as filter embolization or perforation, which again would be complications that would support our recommendation against routine use of these devices in patients undergoing major surgery,” he said.

In terms of the type of pharmacologic prophylaxis to use, the panel said low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin would be reasonable choices in this setting. Available data do not demonstrate any significant differences between these choices for major clinical outcomes, Dr. Anderson added.

The guideline also addresses duration of pharmacologic prophylaxis, stating that extended prophylaxis – of at least 3 weeks – is favored over short-term prophylaxis, or up to 2 weeks of treatment. The extended approach significantly reduces risk of symptomatic PE and proximal DVT, though most of the supporting data come from studies of major joint arthroplasty and major general surgical procedures for patients with cancer. “We need more studies in other clinical areas to examine this particular question,” Dr. Anderson said.

The guideline on prophylaxis in surgical patients was published in Blood Advances (2019 Dec 3;3[23]:3898-944). Six other ASH VTE guidelines, all published in 2018, covered prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, VTE in pregnancy, optimal anticoagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and pediatric considerations. The guidelines are available on the ASH website.

Dr. Anderson reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

ORLANDO – The latest American Society of Hematology guideline on venous thromboembolism (VTE) tackles 30 key questions regarding prophylaxis in hospitalized patients undergoing surgery, according to the chair of the guideline panel, who highlighted 9 of those questions during a special session at the society’s annual meeting.

The clinical practice guideline, published just about a week before the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, focuses mainly on pharmacologic prophylaxis in specific surgical settings, said David R. Anderson, MD, dean of the faculty of medicine of Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

“Our guidelines focused upon clinically important symptomatic outcomes, with less emphasis being placed on asymptomatic deep vein thrombosis detected by screening tests,” Dr. Anderson said.

At the special education session, Dr. Anderson highlighted several specific recommendations on prophylaxis in surgical patients.

Pharmacologic prophylaxis is not recommended for patients experiencing major trauma deemed to be at high risk of bleeding. Its use does reduce risk of symptomatic pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) by about 10 events per 1,000 patients treated; however, Dr. Anderson said, the panel’s opinion was that this benefit was outweighed by increased risk of major bleeding, at 24 events per 1,000 patients treated.

“We do recommend, however that this risk of bleeding must be reevaluated over the course of recovery of patients, and this may change the decision around this intervention over time,” Dr. Anderson told attendees at the special session.

That’s because pharmacologic prophylaxis is recommended in surgical patients at low to moderate risk of bleeding. In this scenario, the incremental risk of major bleeding (14 events per 1,000 patients treated) is outweighed by the benefit of the reduction of symptomatic VTE events, according to Dr. Anderson.

When pharmacologic prophylaxis is used, the panel recommends combined prophylaxis – mechanical prophylaxis in addition to pharmacologic prophylaxis – especially in those patients at high or very high risk of VTE. Evidence shows that the combination approach significantly reduces risk of PE, and strongly suggests it may also reduce risk of symptomatic proximal DVT, Dr. Anderson said.

In surgical patients not receiving pharmacologic prophylaxis, mechanical prophylaxis is recommended over no mechanical prophylaxis, he added. Moreover, in those patients receiving mechanical prophylaxis, the ASH panel recommends use of intermittent compression devices over graduated compression stockings.

The panel comes out against prophylactic inferior vena cava (IVC) filter insertion in the guidelines. Dr. Anderson said that the “small reduction” in PE risk seen in observational studies is outweighed by increased risk of DVT, and a resulting trend for increased mortality, associated with insertion of the devices.

“We did not consider other risks of IVC filters such as filter embolization or perforation, which again would be complications that would support our recommendation against routine use of these devices in patients undergoing major surgery,” he said.

In terms of the type of pharmacologic prophylaxis to use, the panel said low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin would be reasonable choices in this setting. Available data do not demonstrate any significant differences between these choices for major clinical outcomes, Dr. Anderson added.

The guideline also addresses duration of pharmacologic prophylaxis, stating that extended prophylaxis – of at least 3 weeks – is favored over short-term prophylaxis, or up to 2 weeks of treatment. The extended approach significantly reduces risk of symptomatic PE and proximal DVT, though most of the supporting data come from studies of major joint arthroplasty and major general surgical procedures for patients with cancer. “We need more studies in other clinical areas to examine this particular question,” Dr. Anderson said.

The guideline on prophylaxis in surgical patients was published in Blood Advances (2019 Dec 3;3[23]:3898-944). Six other ASH VTE guidelines, all published in 2018, covered prophylaxis in medical patients, diagnosis, VTE in pregnancy, optimal anticoagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and pediatric considerations. The guidelines are available on the ASH website.

Dr. Anderson reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ASH 2019

Cardiac arrhythmia heightens mortality risk during epilepsy hospitalizations

BALTIMORE – Patients hospitalized for epilepsy may have higher odds of death if they have a secondary diagnosis of arrhythmia, whereas the presence of apnea alone may not significantly increase mortality, according to an analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“If you have someone with arrhythmia and epilepsy, you have to be more concerned about possible SUDEP [sudden unexpected death in epilepsy],” relative to someone with apnea and epilepsy, said senior study author Sanjay P. Singh, MD, professor of neurology at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

Research indicates that apnea and cardiac arrhythmias may contribute to SUDEP, and the incidence of SUDEP is higher in patients with intractable epilepsy.

To identify the prevalence of apnea, arrhythmia, and both conditions in epilepsy hospitalizations, as well as the prevalence of intractable epilepsy and mortality, Dr. Singh and colleagues performed a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of pediatric and adult epilepsy hospitalizations between 2003 and 2014 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. They determined apnea and arrhythmia diagnoses using ICD-9-CM codes.

Among more than 2.6 million epilepsy hospitalizations, the prevalence of apnea was 2.75%, the prevalence of arrhythmia was 8.91%, and the prevalence of both was 0.49%. The proportion of patients with intractable epilepsy was 7.7%. Among the more than 207,000 hospitalizations with intractable epilepsy, the prevalence of apnea was 3.62%, the prevalence of arrhythmia was 3.34%, and the prevalence of both was 0.36%. The prevalence trend of apnea, arrhythmia, and both together increased between 2003 and 2014.

“In univariate analysis, prevalence of mortality was highest among patients with arrhythmia,” the researchers reported, at – 3.1% in patients with arrhythmia versus 0.48% in patients with apnea, 2.91% in patients with both, and 0.46% in patients without apnea or arrhythmia.

In a multivariable regression analysis, significant and independent predictors of death included intractable epilepsy (odds ratio, 1.17), apnea (OR, 0.84), arrhythmia (OR, 3.29), and the presence of both apnea and arrhythmia (OR, 3.24). When hospitalization was complicated by intractable epilepsy, the odds of death rose with the presence of apnea (OR, 2.07), arrhythmia (OR, 8.39), and with both apnea and arrhythmia (OR, 11.64).

The results highlight the importance of effective epilepsy management, said first author Urvish K. Patel, MBBS, also with Creighton University. “If we can stop [conversion to intractable epilepsy], then this odds ratio can go down.”

Attention to arrhythmias, as well as the combination of arrhythmias and apnea, may “be important in identifying patients at risk for SUDEP,” the authors concluded.

The researchers had no disclosures and reported receiving no outside funding for their work.

SOURCE: Patel UK et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.140.

BALTIMORE – Patients hospitalized for epilepsy may have higher odds of death if they have a secondary diagnosis of arrhythmia, whereas the presence of apnea alone may not significantly increase mortality, according to an analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“If you have someone with arrhythmia and epilepsy, you have to be more concerned about possible SUDEP [sudden unexpected death in epilepsy],” relative to someone with apnea and epilepsy, said senior study author Sanjay P. Singh, MD, professor of neurology at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

Research indicates that apnea and cardiac arrhythmias may contribute to SUDEP, and the incidence of SUDEP is higher in patients with intractable epilepsy.

To identify the prevalence of apnea, arrhythmia, and both conditions in epilepsy hospitalizations, as well as the prevalence of intractable epilepsy and mortality, Dr. Singh and colleagues performed a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of pediatric and adult epilepsy hospitalizations between 2003 and 2014 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. They determined apnea and arrhythmia diagnoses using ICD-9-CM codes.

Among more than 2.6 million epilepsy hospitalizations, the prevalence of apnea was 2.75%, the prevalence of arrhythmia was 8.91%, and the prevalence of both was 0.49%. The proportion of patients with intractable epilepsy was 7.7%. Among the more than 207,000 hospitalizations with intractable epilepsy, the prevalence of apnea was 3.62%, the prevalence of arrhythmia was 3.34%, and the prevalence of both was 0.36%. The prevalence trend of apnea, arrhythmia, and both together increased between 2003 and 2014.

“In univariate analysis, prevalence of mortality was highest among patients with arrhythmia,” the researchers reported, at – 3.1% in patients with arrhythmia versus 0.48% in patients with apnea, 2.91% in patients with both, and 0.46% in patients without apnea or arrhythmia.

In a multivariable regression analysis, significant and independent predictors of death included intractable epilepsy (odds ratio, 1.17), apnea (OR, 0.84), arrhythmia (OR, 3.29), and the presence of both apnea and arrhythmia (OR, 3.24). When hospitalization was complicated by intractable epilepsy, the odds of death rose with the presence of apnea (OR, 2.07), arrhythmia (OR, 8.39), and with both apnea and arrhythmia (OR, 11.64).

The results highlight the importance of effective epilepsy management, said first author Urvish K. Patel, MBBS, also with Creighton University. “If we can stop [conversion to intractable epilepsy], then this odds ratio can go down.”

Attention to arrhythmias, as well as the combination of arrhythmias and apnea, may “be important in identifying patients at risk for SUDEP,” the authors concluded.

The researchers had no disclosures and reported receiving no outside funding for their work.

SOURCE: Patel UK et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.140.

BALTIMORE – Patients hospitalized for epilepsy may have higher odds of death if they have a secondary diagnosis of arrhythmia, whereas the presence of apnea alone may not significantly increase mortality, according to an analysis of data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

“If you have someone with arrhythmia and epilepsy, you have to be more concerned about possible SUDEP [sudden unexpected death in epilepsy],” relative to someone with apnea and epilepsy, said senior study author Sanjay P. Singh, MD, professor of neurology at Creighton University, Omaha, Neb.

Research indicates that apnea and cardiac arrhythmias may contribute to SUDEP, and the incidence of SUDEP is higher in patients with intractable epilepsy.

To identify the prevalence of apnea, arrhythmia, and both conditions in epilepsy hospitalizations, as well as the prevalence of intractable epilepsy and mortality, Dr. Singh and colleagues performed a retrospective, cross-sectional analysis of pediatric and adult epilepsy hospitalizations between 2003 and 2014 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample. They determined apnea and arrhythmia diagnoses using ICD-9-CM codes.

Among more than 2.6 million epilepsy hospitalizations, the prevalence of apnea was 2.75%, the prevalence of arrhythmia was 8.91%, and the prevalence of both was 0.49%. The proportion of patients with intractable epilepsy was 7.7%. Among the more than 207,000 hospitalizations with intractable epilepsy, the prevalence of apnea was 3.62%, the prevalence of arrhythmia was 3.34%, and the prevalence of both was 0.36%. The prevalence trend of apnea, arrhythmia, and both together increased between 2003 and 2014.

“In univariate analysis, prevalence of mortality was highest among patients with arrhythmia,” the researchers reported, at – 3.1% in patients with arrhythmia versus 0.48% in patients with apnea, 2.91% in patients with both, and 0.46% in patients without apnea or arrhythmia.

In a multivariable regression analysis, significant and independent predictors of death included intractable epilepsy (odds ratio, 1.17), apnea (OR, 0.84), arrhythmia (OR, 3.29), and the presence of both apnea and arrhythmia (OR, 3.24). When hospitalization was complicated by intractable epilepsy, the odds of death rose with the presence of apnea (OR, 2.07), arrhythmia (OR, 8.39), and with both apnea and arrhythmia (OR, 11.64).

The results highlight the importance of effective epilepsy management, said first author Urvish K. Patel, MBBS, also with Creighton University. “If we can stop [conversion to intractable epilepsy], then this odds ratio can go down.”

Attention to arrhythmias, as well as the combination of arrhythmias and apnea, may “be important in identifying patients at risk for SUDEP,” the authors concluded.

The researchers had no disclosures and reported receiving no outside funding for their work.

SOURCE: Patel UK et al. AES 2019, Abstract 2.140.

REPORTING FROM AES 2019

Unit-based rounding in the real world

Balance and flexibility are essential

Many hospitalists agree that their most productive and also sometimes least productive work can happen in the setting of interdisciplinary rounds. How can this paradox be true?

Most hospitals strive to assemble the health care team every day for a brief discussion of each patient’s needs as well as barriers to a safe/successful discharge. On most floors this requires a well-choreographed “dance” of nurses, case managers, social workers, physicians, and advanced practice providers coming together at agreed-upon times. All team members commit to efficient synchronized swimming through the most high-yield details for each patient in order to benefit the patients and families being served.

Of course, there are always challenges to this process in the unpredictable world of patients with acute needs. One variable that is at least partially controllable and tends to promote a more cohesive interdisciplinary experience is that of hospitalist unit-based rounding.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) survey reveals that 68% of hospital medicine groups serving adults with greater than 30 physicians employ some degree of unit-based rounding; this trend decreases with smaller group size. About 54% of academic hospital medicine groups use some amount of unit-based rounding. Not surprisingly, smaller hospitals are less likely to have this routine, likely because of fewer total nursing units.

One of the most obvious benefits to unit-based rounding is that the physician or advanced practice provider is more reliably able to participate in the interdisciplinary discussions that day. When more of the team members are at the table each day, patients and families have the best chance of hearing a consistent message around the treatment and discharge plans.

There are challenges to unit-based rounding as well. If patients transfer to different floors for any variety of reasons, strict unit-based rounding may increase handoffs in care. If a hospital has times when it isn’t completely full and nursing units have a varying percentage of being occupied, strict unit-based rounding can cause significant workload inequities among physicians on different units, depending on numbers of patients on each unit.

If there is no attempt at unit-based rounding in larger hospitals, some physicians may be running among five or more units. They work to find different care managers, nurses, and pharmacists – not to mention the challenges of catching patients in their rooms between their departures for diagnostic studies and procedures.

It is often good to balance the benefit of promoting unit-based rounds with the reality of everyday patient care. Some groups maintain that the physician/patient relationship trumps the idea of perfect unit-based rounding. In other words, if a physician establishes a relationship with a patient while they are in the ED being admitted or boarding from overnight, that physician will continue seeing the patient regardless of the patient being assigned to a different unit. It can help for groups to agree that the pursuit of unit-based rounding may create some inequity in the numbers of patients seen each day because of these issues.

In a larger hospital, certain units are often dedicated to specialty care such as cardiac or stroke care. While most hospitalists want to maintain general medical knowledge, there are some who may enjoy having portions of their practice devoted to perioperative medicine or cardiac care, for instance. This promotes familiarity among hospitalists and groups of consultant physicians and nurse practitioners/physician assistants. Over time this allows for enhanced teamwork among those physicians, the nursing team, and the specialty physicians.

Depending on the group’s schedule, patients can be reassigned coinciding with the primary change of service day. This resets the physicians’ patients in the most ideal unit-based way on the evening prior to the first day of rounding for that week or group of shifts.

No matter how you do it, the goal of unit-based rounding is time efficiency for the care team and care coordination benefits for patients and families. If you have other suggestions or questions, go online to SHM HMX to join the discussion.

Take-home message: Unit-based rounding likely has its benefits. Don’t let the inability to achieve perfection in patient distribution to the physicians each day lead to abandonment of attempting these processes.

Dr. McNeal is the division director of inpatient medicine at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Temple, Tex.

Balance and flexibility are essential

Balance and flexibility are essential

Many hospitalists agree that their most productive and also sometimes least productive work can happen in the setting of interdisciplinary rounds. How can this paradox be true?

Most hospitals strive to assemble the health care team every day for a brief discussion of each patient’s needs as well as barriers to a safe/successful discharge. On most floors this requires a well-choreographed “dance” of nurses, case managers, social workers, physicians, and advanced practice providers coming together at agreed-upon times. All team members commit to efficient synchronized swimming through the most high-yield details for each patient in order to benefit the patients and families being served.

Of course, there are always challenges to this process in the unpredictable world of patients with acute needs. One variable that is at least partially controllable and tends to promote a more cohesive interdisciplinary experience is that of hospitalist unit-based rounding.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) survey reveals that 68% of hospital medicine groups serving adults with greater than 30 physicians employ some degree of unit-based rounding; this trend decreases with smaller group size. About 54% of academic hospital medicine groups use some amount of unit-based rounding. Not surprisingly, smaller hospitals are less likely to have this routine, likely because of fewer total nursing units.

One of the most obvious benefits to unit-based rounding is that the physician or advanced practice provider is more reliably able to participate in the interdisciplinary discussions that day. When more of the team members are at the table each day, patients and families have the best chance of hearing a consistent message around the treatment and discharge plans.

There are challenges to unit-based rounding as well. If patients transfer to different floors for any variety of reasons, strict unit-based rounding may increase handoffs in care. If a hospital has times when it isn’t completely full and nursing units have a varying percentage of being occupied, strict unit-based rounding can cause significant workload inequities among physicians on different units, depending on numbers of patients on each unit.

If there is no attempt at unit-based rounding in larger hospitals, some physicians may be running among five or more units. They work to find different care managers, nurses, and pharmacists – not to mention the challenges of catching patients in their rooms between their departures for diagnostic studies and procedures.

It is often good to balance the benefit of promoting unit-based rounds with the reality of everyday patient care. Some groups maintain that the physician/patient relationship trumps the idea of perfect unit-based rounding. In other words, if a physician establishes a relationship with a patient while they are in the ED being admitted or boarding from overnight, that physician will continue seeing the patient regardless of the patient being assigned to a different unit. It can help for groups to agree that the pursuit of unit-based rounding may create some inequity in the numbers of patients seen each day because of these issues.

In a larger hospital, certain units are often dedicated to specialty care such as cardiac or stroke care. While most hospitalists want to maintain general medical knowledge, there are some who may enjoy having portions of their practice devoted to perioperative medicine or cardiac care, for instance. This promotes familiarity among hospitalists and groups of consultant physicians and nurse practitioners/physician assistants. Over time this allows for enhanced teamwork among those physicians, the nursing team, and the specialty physicians.

Depending on the group’s schedule, patients can be reassigned coinciding with the primary change of service day. This resets the physicians’ patients in the most ideal unit-based way on the evening prior to the first day of rounding for that week or group of shifts.

No matter how you do it, the goal of unit-based rounding is time efficiency for the care team and care coordination benefits for patients and families. If you have other suggestions or questions, go online to SHM HMX to join the discussion.

Take-home message: Unit-based rounding likely has its benefits. Don’t let the inability to achieve perfection in patient distribution to the physicians each day lead to abandonment of attempting these processes.

Dr. McNeal is the division director of inpatient medicine at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Temple, Tex.

Many hospitalists agree that their most productive and also sometimes least productive work can happen in the setting of interdisciplinary rounds. How can this paradox be true?

Most hospitals strive to assemble the health care team every day for a brief discussion of each patient’s needs as well as barriers to a safe/successful discharge. On most floors this requires a well-choreographed “dance” of nurses, case managers, social workers, physicians, and advanced practice providers coming together at agreed-upon times. All team members commit to efficient synchronized swimming through the most high-yield details for each patient in order to benefit the patients and families being served.

Of course, there are always challenges to this process in the unpredictable world of patients with acute needs. One variable that is at least partially controllable and tends to promote a more cohesive interdisciplinary experience is that of hospitalist unit-based rounding.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) survey reveals that 68% of hospital medicine groups serving adults with greater than 30 physicians employ some degree of unit-based rounding; this trend decreases with smaller group size. About 54% of academic hospital medicine groups use some amount of unit-based rounding. Not surprisingly, smaller hospitals are less likely to have this routine, likely because of fewer total nursing units.

One of the most obvious benefits to unit-based rounding is that the physician or advanced practice provider is more reliably able to participate in the interdisciplinary discussions that day. When more of the team members are at the table each day, patients and families have the best chance of hearing a consistent message around the treatment and discharge plans.

There are challenges to unit-based rounding as well. If patients transfer to different floors for any variety of reasons, strict unit-based rounding may increase handoffs in care. If a hospital has times when it isn’t completely full and nursing units have a varying percentage of being occupied, strict unit-based rounding can cause significant workload inequities among physicians on different units, depending on numbers of patients on each unit.

If there is no attempt at unit-based rounding in larger hospitals, some physicians may be running among five or more units. They work to find different care managers, nurses, and pharmacists – not to mention the challenges of catching patients in their rooms between their departures for diagnostic studies and procedures.

It is often good to balance the benefit of promoting unit-based rounds with the reality of everyday patient care. Some groups maintain that the physician/patient relationship trumps the idea of perfect unit-based rounding. In other words, if a physician establishes a relationship with a patient while they are in the ED being admitted or boarding from overnight, that physician will continue seeing the patient regardless of the patient being assigned to a different unit. It can help for groups to agree that the pursuit of unit-based rounding may create some inequity in the numbers of patients seen each day because of these issues.

In a larger hospital, certain units are often dedicated to specialty care such as cardiac or stroke care. While most hospitalists want to maintain general medical knowledge, there are some who may enjoy having portions of their practice devoted to perioperative medicine or cardiac care, for instance. This promotes familiarity among hospitalists and groups of consultant physicians and nurse practitioners/physician assistants. Over time this allows for enhanced teamwork among those physicians, the nursing team, and the specialty physicians.

Depending on the group’s schedule, patients can be reassigned coinciding with the primary change of service day. This resets the physicians’ patients in the most ideal unit-based way on the evening prior to the first day of rounding for that week or group of shifts.

No matter how you do it, the goal of unit-based rounding is time efficiency for the care team and care coordination benefits for patients and families. If you have other suggestions or questions, go online to SHM HMX to join the discussion.

Take-home message: Unit-based rounding likely has its benefits. Don’t let the inability to achieve perfection in patient distribution to the physicians each day lead to abandonment of attempting these processes.

Dr. McNeal is the division director of inpatient medicine at Baylor Scott & White Medical Center in Temple, Tex.

EVALI outbreak ongoing, but new cases decline

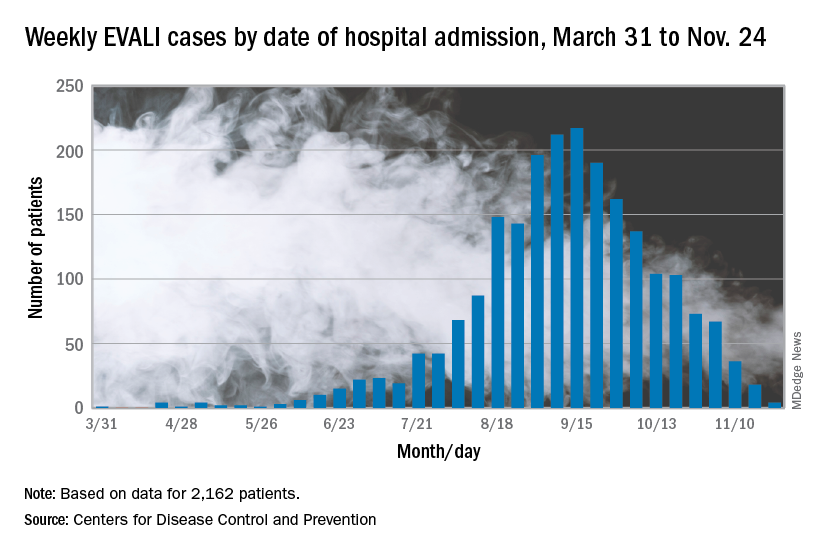

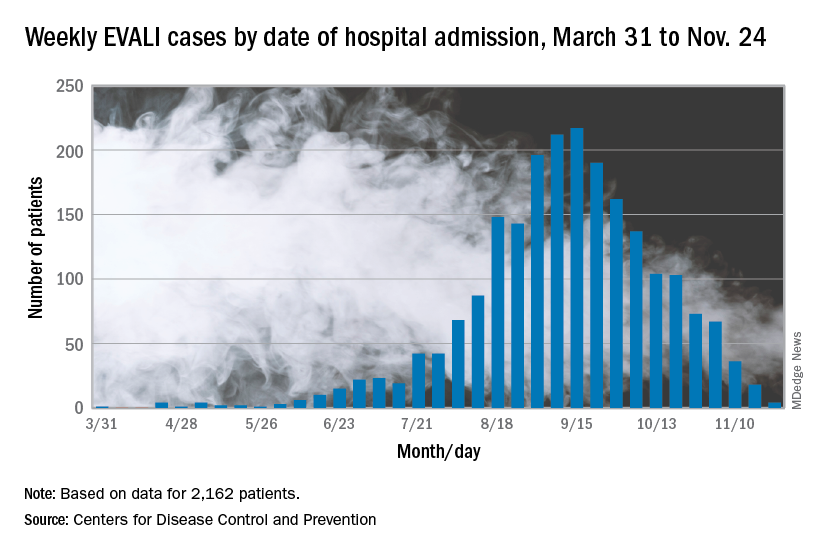

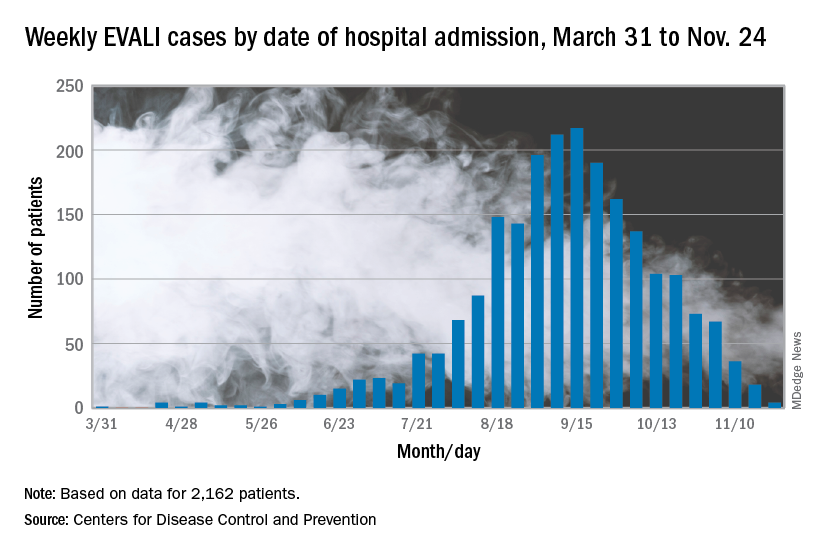

The vaping lung disease outbreak continues, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may have peaked and the number of new hospitalized cases reported to the CDC may be decreasing.

In the Dec. 6, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC has updated information about cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI): As of Dec. 3, there have been 2,291 cases reported from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands). A total of 48 deaths have been confirmed in 25 states and Washington, D.C., the CDC reported.

The largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of Sept. 15, 2019; since then, hospitalized cases have steadily declined. “Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3,” the report stated.

About 80%of hospitalized EVALI patients reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)–containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. “Dank Vapes,” counterfeit THC-containing products of unknown origin, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products used. Dank Vapes were used by 56% of hospitalized EVALI patients nationwide, followed by TKO brand (15%), Smart Cart (13%), and Rove (12%).

Of EVALI patients for whom data were available, 67% were male, and the median age was 24 years (range, 13-77 years); 78% were aged under 35 years and 16% were under 18 years. About 75% of EVALI patients were non-Hispanic white and 16% were Hispanic. Among the 48 deaths, 54% of patients were male, and the median age was 52 years (range, 17-75 years).

CDC research on EVALI continues to be limited by the self-reported data, lack of data on substances used, missing data, loss to follow-up, and reporting lags, but the intensive investigation and data collection is ongoing.

The report concludes: “While the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Adults using e-cigarette, or vaping, products to quit smoking should not return to smoking cigarettes; they should weigh all risks and benefits and consider using [Food and Drug Administration]–approved cessation medications. Adults who continue to use e-cigarette, or vaping, products should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms similar to those reported in this outbreak. Irrespective of the ongoing investigation, e-cigarette, or vaping, products should never be used by youths, young adults or pregnant women.”

Information on the current investigation, reporting of cases, and other resources can be found on the CDC website.

SOURCE: Lozier MJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6849e1.

The vaping lung disease outbreak continues, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may have peaked and the number of new hospitalized cases reported to the CDC may be decreasing.

In the Dec. 6, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC has updated information about cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI): As of Dec. 3, there have been 2,291 cases reported from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands). A total of 48 deaths have been confirmed in 25 states and Washington, D.C., the CDC reported.

The largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of Sept. 15, 2019; since then, hospitalized cases have steadily declined. “Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3,” the report stated.

About 80%of hospitalized EVALI patients reported using tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)–containing e-cigarette, or vaping, products. “Dank Vapes,” counterfeit THC-containing products of unknown origin, were the most commonly reported THC-containing branded products used. Dank Vapes were used by 56% of hospitalized EVALI patients nationwide, followed by TKO brand (15%), Smart Cart (13%), and Rove (12%).

Of EVALI patients for whom data were available, 67% were male, and the median age was 24 years (range, 13-77 years); 78% were aged under 35 years and 16% were under 18 years. About 75% of EVALI patients were non-Hispanic white and 16% were Hispanic. Among the 48 deaths, 54% of patients were male, and the median age was 52 years (range, 17-75 years).

CDC research on EVALI continues to be limited by the self-reported data, lack of data on substances used, missing data, loss to follow-up, and reporting lags, but the intensive investigation and data collection is ongoing.

The report concludes: “While the investigation continues, persons should consider refraining from the use of all e-cigarette, or vaping, products. Adults using e-cigarette, or vaping, products to quit smoking should not return to smoking cigarettes; they should weigh all risks and benefits and consider using [Food and Drug Administration]–approved cessation medications. Adults who continue to use e-cigarette, or vaping, products should carefully monitor themselves for symptoms and see a health care provider immediately if they develop symptoms similar to those reported in this outbreak. Irrespective of the ongoing investigation, e-cigarette, or vaping, products should never be used by youths, young adults or pregnant women.”

Information on the current investigation, reporting of cases, and other resources can be found on the CDC website.

SOURCE: Lozier MJ et al. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Dec 6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6849e1.

The vaping lung disease outbreak continues, but according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, it may have peaked and the number of new hospitalized cases reported to the CDC may be decreasing.

In the Dec. 6, 2019, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the CDC has updated information about cases of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use–associated lung injury (EVALI): As of Dec. 3, there have been 2,291 cases reported from all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and two U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands). A total of 48 deaths have been confirmed in 25 states and Washington, D.C., the CDC reported.

The largest number of weekly hospitalized cases occurred during the week of Sept. 15, 2019; since then, hospitalized cases have steadily declined. “Among all hospitalized EVALI patients reported to CDC weekly, the percentage of recent cases (patients hospitalized within the preceding 3 weeks) declined from 58% reported November 12 to 30% reported December 3,” the report stated.