User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Epinephrine for cardiac arrest: Better survival, more brain damage

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

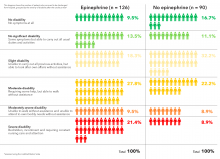

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Epinephrine has been used in resuscitation efforts since the 1960s, yet no reliable evidence on the practice has been collected. Now, PARAMEDIC2 provides the most rigorous data on patient-centered outcomes with respect to epinephrine to date.

Epinephrine increased 30-day survival in patients with nonshockable rhythms by more than 100%, but the benefit was less clear in those with shockable rhythms. Shockable rhythms are more likely to occur in patients with cardiac or cardiovascular causes of arrest, which epinephrine may exacerbate. The results underscore the principle that drug administration should not compete with or delay defibrillation, and that epinephrine may have different effects in patients with different ECG rhythms.

The PARAMEDIC2 results leave us with several questions: Could other, additional treatments after a return of spontaneous circulation improve functional recovery, should drug use differ on the basis of cardiac rhythm, and would lower doses of epinephrine be superior to higher doses among patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

Clifton W. Callaway, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh, and Michael W. Donnino, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1808255). They had no relevant disclosures.

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

Using epinephrine for cardiac arrest improves 30-day survival by less than 1%, and nearly doubles the risk of severe brain damage among survivors, according to PARAMEDIC2, a randomized, double-blind trial in more than 8,000 patients in Great Britain.

It’s clear what patients want. “Our own work with patients and the public before starting the trial identified survival without brain damage [as] more important to patients than survival alone. The findings of this trial will require careful consideration by the wider community and those responsible for clinical practice guidelines for cardiac arrest,” lead investigator Gavin D. Perkins, MD, professor of critical care medicine at the University of Warwick, Coventry, England, and lead author of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, wrote in a statement.

In PARAMEDIC2, after initial attempts with CPR and defibrillation failed, 4,012 patients were given epinephrine 1 mg by intravenous or intraosseous infusion every 3-5 minutes for a maximum of 10 doses, and 3,995 were given a saline placebo in the same fashion. The median time from emergency call to ambulance arrival was just over 6 minutes in both groups, with a further 14 minutes until drug administration.

The heart restarted in a higher proportion of epinephrine patients (36.3% vs. 11.7%), and 3.2% of epinephrine patients were alive at 30 days, versus 2.4% in the placebo arm, a 39% increase.

However, that slight benefit came at a significant cost. Of the 126 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (31%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (17.8%) among the 90 placebo survivors. Severe brain damage meant inability to walk and tend to bodily functions, or a persistent vegetative state (modified Rankin scale grade 4 or 5).

The trial addresses a long-standing question in resuscitation medicine, the role of epinephrine in cardiac arrest. It’s a devil’s bargain: Epinephrine increases blood flow to the heart, so helps with resuscitation, but it also reduces blood flow in the brain’s microvasculature, increasing the risk of brain damage.

“The benefit of epinephrine on survival demonstrated in this trial should be considered in comparison with other treatments in the chain of survival.” Early cardiac arrest recognition saves 1 in every 11 patients, bystander CPR saves 1 in every 15, and early defibrillation saves 1 in 5, the investigators noted.

The trial did not collect data on prearrest neurologic status, but the number of subjects with impaired function was probably very small and balanced between the groups, according to the report.

On average, patients were aged just under 70 years, 65% were men, and bystander CPR was performed in about 60% in both groups. They were enrolled by five ambulance services in England and Wales. Informed consent was obtained, when possible, after resuscitation.

The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of the 128 epinephrine patients who survived to hospital discharge, 39 (30.1%) had severe brain damage, compared with 16 (18.7%) among the 91 placebo survivors.

Study details: A randomized, double-blind trial of over 8,000 U.K. patients experiencing an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Disclosures: The trial was funded by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. The researchers had no relevant disclosures to report.

Source: Perkins GD et al. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 18. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1806842.

National Academies issues 5-step plan to address infections linked to opioid use disorder

Widespread opioid use disorder (OUD) has spawned new epidemics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV infections as well as increased hospitalizations for bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis, according to a report arising from a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) workshop titled Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic.

Optimal treatment of these infections is often impeded by untreated OUD, Sandra A. Springer, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an article published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Failing to address OUD can result in longer hospital stays; frequent readmissions because of a lack of adherence to antibiotic regimens; or reinfection, morbidity, and high costs. “Medical settings that manage such infections offer a potential means of engaging people in treatment of OUD; however, few providers and hospitals treating such infections have the needed resources and capabilities,” Dr. Springer, director, infectious disease outpatient clinic, Veterans Administration, Newington, and of Yale University, New Haven, both in Conn., and her colleagues wrote.

The authors outlined five action steps resulting from the NASEM workshop:

- Implement screening for OUD in all relevant health care settings.

- For patients with positive screening results, immediately prescribe effective medication for OUD and/or opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop hospital-based protocols that facilitate OUD treatment initiation and linkage to community-based treatment upon discharge.

- Hospitals, medical schools, physician assistant schools, nursing schools, and residency programs should increase training to identify and treat OUD.

- Increase access to addiction care and funding to states to provide effective medications to treat OUD.

Opioid withdrawal and pain syndromes should be addressed with opioid agonist therapies to optimize infectious disease (ID) treatment and relieve pain, according to Dr. Springer and her colleagues. In addition, “Because ID specialists are likely to be consulted for anyone requiring long-term antibiotic therapy or patients with HIV and HCV infection, OUD screening should be a standard part of an ID consult assessment,” the authors wrote.

“All health care providers have a role in combating the OUD epidemic and its ID consequences. Those who treat infectious complications of OUD are well suited to screen for OUD and begin treatment with effective FDA-approved medications,” the authors concluded.

The workshop was held in March 2018 in Washington and videos and slide presentations from the meeting are available.

Dr. Springer and her colleagues reported grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, but no commercial conflicts.

SOURCE: Springer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 13. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Widespread opioid use disorder (OUD) has spawned new epidemics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV infections as well as increased hospitalizations for bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis, according to a report arising from a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) workshop titled Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic.

Optimal treatment of these infections is often impeded by untreated OUD, Sandra A. Springer, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an article published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Failing to address OUD can result in longer hospital stays; frequent readmissions because of a lack of adherence to antibiotic regimens; or reinfection, morbidity, and high costs. “Medical settings that manage such infections offer a potential means of engaging people in treatment of OUD; however, few providers and hospitals treating such infections have the needed resources and capabilities,” Dr. Springer, director, infectious disease outpatient clinic, Veterans Administration, Newington, and of Yale University, New Haven, both in Conn., and her colleagues wrote.

The authors outlined five action steps resulting from the NASEM workshop:

- Implement screening for OUD in all relevant health care settings.

- For patients with positive screening results, immediately prescribe effective medication for OUD and/or opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop hospital-based protocols that facilitate OUD treatment initiation and linkage to community-based treatment upon discharge.

- Hospitals, medical schools, physician assistant schools, nursing schools, and residency programs should increase training to identify and treat OUD.

- Increase access to addiction care and funding to states to provide effective medications to treat OUD.

Opioid withdrawal and pain syndromes should be addressed with opioid agonist therapies to optimize infectious disease (ID) treatment and relieve pain, according to Dr. Springer and her colleagues. In addition, “Because ID specialists are likely to be consulted for anyone requiring long-term antibiotic therapy or patients with HIV and HCV infection, OUD screening should be a standard part of an ID consult assessment,” the authors wrote.

“All health care providers have a role in combating the OUD epidemic and its ID consequences. Those who treat infectious complications of OUD are well suited to screen for OUD and begin treatment with effective FDA-approved medications,” the authors concluded.

The workshop was held in March 2018 in Washington and videos and slide presentations from the meeting are available.

Dr. Springer and her colleagues reported grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, but no commercial conflicts.

SOURCE: Springer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 13. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

Widespread opioid use disorder (OUD) has spawned new epidemics of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV infections as well as increased hospitalizations for bacteremia, endocarditis, skin and soft tissue infections, and osteomyelitis, according to a report arising from a National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) workshop titled Integrating Infectious Disease Considerations with Response to the Opioid Epidemic.

Optimal treatment of these infections is often impeded by untreated OUD, Sandra A. Springer, MD, and her colleagues wrote in an article published online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Failing to address OUD can result in longer hospital stays; frequent readmissions because of a lack of adherence to antibiotic regimens; or reinfection, morbidity, and high costs. “Medical settings that manage such infections offer a potential means of engaging people in treatment of OUD; however, few providers and hospitals treating such infections have the needed resources and capabilities,” Dr. Springer, director, infectious disease outpatient clinic, Veterans Administration, Newington, and of Yale University, New Haven, both in Conn., and her colleagues wrote.

The authors outlined five action steps resulting from the NASEM workshop:

- Implement screening for OUD in all relevant health care settings.

- For patients with positive screening results, immediately prescribe effective medication for OUD and/or opioid withdrawal symptoms.

- Develop hospital-based protocols that facilitate OUD treatment initiation and linkage to community-based treatment upon discharge.

- Hospitals, medical schools, physician assistant schools, nursing schools, and residency programs should increase training to identify and treat OUD.

- Increase access to addiction care and funding to states to provide effective medications to treat OUD.

Opioid withdrawal and pain syndromes should be addressed with opioid agonist therapies to optimize infectious disease (ID) treatment and relieve pain, according to Dr. Springer and her colleagues. In addition, “Because ID specialists are likely to be consulted for anyone requiring long-term antibiotic therapy or patients with HIV and HCV infection, OUD screening should be a standard part of an ID consult assessment,” the authors wrote.

“All health care providers have a role in combating the OUD epidemic and its ID consequences. Those who treat infectious complications of OUD are well suited to screen for OUD and begin treatment with effective FDA-approved medications,” the authors concluded.

The workshop was held in March 2018 in Washington and videos and slide presentations from the meeting are available.

Dr. Springer and her colleagues reported grant funding from the National Institutes of Health, but no commercial conflicts.

SOURCE: Springer SA et al. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Jul 13. doi: 10.7326/M18-1203.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

HM18: ‘Things we do for no reason’

Be aware of low value care practices

Presenter

Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM

Session summary

In the current climate of increasing national health care expenditures, the Journal of Hospital Medicine continues to expand its series “Things We Do for No Reason” to shed light on areas for improvement in the delivery of high-value care. Physicians, however, continue to practice low value care because of practice habits and lack of cost transparency. In keeping with the spirit of the journal’s series, three low-value practices were highlighted in this HM18 session, including the benefits of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy, the value of serum albumin and prealbumin in malnutrition, and the use of nebulized versus inhaler albuterol.

HFNC oxygen therapy has become a widespread practice internationally, with large variations in implementation across all age ranges. In bronchiolitic infants, variations in time of implementation, duration of therapy, weaning policies, and outcome measures have yielded mixed results to date. Many studies are still underway, but current literature has not shown significant benefits of starting HFNC early in the illness process, and infants receiving HFNC have not had better outcomes than those who received standard therapy (low-flow nasal cannula).

Serum albumin and prealbumin are often cited as markers of malnutrition. In patients on tube feeds, such as those with cerebral palsy and complex medical conditions, current literature shows no benefit in the use of these lab markers for screening or for following to assess improvement. In addition, patients with eating disorders do not have significant correlation of their nutritive status with these markers. Therefore, the use of these labs for screening of malnutrition is of little if any value.

Finally, when comparing albuterol delivery systems, there has been no proof that nebulized albuterol is any better than metered dose inhalers (MDI) in its effect. As long as appropriate dosing of MDIs is done, the benefits are the same. In addition, side effects are fewer, and the length of stay in the ED is shorter. The more a family uses MDI inhalers, the better their technique. Studies have shown it takes approximately three attempts at using an MDI to get the technique correct, so inpatient MDI use would also decrease user error in the outpatient setting.

Key takeaways for HM

- Practice habits, lack of transparency of costs, and regional training lead to low value care practices.

- Early introduction of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalization of an infant with bronchiolitis has not been shown to decrease length of stay or severity outcomes, according to currently available data.

- Serum albumin and prealbumin have little to no benefit in screening of malnutrition.

- Nebulized albuterol has not been proven to be more beneficial that MDI albuterol at appropriate doses.

- Repeat MDI administration has been shown to positively affect user administration techniques.

- MDI albuterol use has fewer side effects and decreased ED length of stay, compared with nebulized albuterol.

Dr. Schwenk is an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and a pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville.

Be aware of low value care practices

Be aware of low value care practices

Presenter

Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM

Session summary

In the current climate of increasing national health care expenditures, the Journal of Hospital Medicine continues to expand its series “Things We Do for No Reason” to shed light on areas for improvement in the delivery of high-value care. Physicians, however, continue to practice low value care because of practice habits and lack of cost transparency. In keeping with the spirit of the journal’s series, three low-value practices were highlighted in this HM18 session, including the benefits of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy, the value of serum albumin and prealbumin in malnutrition, and the use of nebulized versus inhaler albuterol.

HFNC oxygen therapy has become a widespread practice internationally, with large variations in implementation across all age ranges. In bronchiolitic infants, variations in time of implementation, duration of therapy, weaning policies, and outcome measures have yielded mixed results to date. Many studies are still underway, but current literature has not shown significant benefits of starting HFNC early in the illness process, and infants receiving HFNC have not had better outcomes than those who received standard therapy (low-flow nasal cannula).

Serum albumin and prealbumin are often cited as markers of malnutrition. In patients on tube feeds, such as those with cerebral palsy and complex medical conditions, current literature shows no benefit in the use of these lab markers for screening or for following to assess improvement. In addition, patients with eating disorders do not have significant correlation of their nutritive status with these markers. Therefore, the use of these labs for screening of malnutrition is of little if any value.

Finally, when comparing albuterol delivery systems, there has been no proof that nebulized albuterol is any better than metered dose inhalers (MDI) in its effect. As long as appropriate dosing of MDIs is done, the benefits are the same. In addition, side effects are fewer, and the length of stay in the ED is shorter. The more a family uses MDI inhalers, the better their technique. Studies have shown it takes approximately three attempts at using an MDI to get the technique correct, so inpatient MDI use would also decrease user error in the outpatient setting.

Key takeaways for HM

- Practice habits, lack of transparency of costs, and regional training lead to low value care practices.

- Early introduction of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalization of an infant with bronchiolitis has not been shown to decrease length of stay or severity outcomes, according to currently available data.

- Serum albumin and prealbumin have little to no benefit in screening of malnutrition.

- Nebulized albuterol has not been proven to be more beneficial that MDI albuterol at appropriate doses.

- Repeat MDI administration has been shown to positively affect user administration techniques.

- MDI albuterol use has fewer side effects and decreased ED length of stay, compared with nebulized albuterol.

Dr. Schwenk is an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and a pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville.

Presenter

Leonard Feldman, MD, SFHM

Session summary

In the current climate of increasing national health care expenditures, the Journal of Hospital Medicine continues to expand its series “Things We Do for No Reason” to shed light on areas for improvement in the delivery of high-value care. Physicians, however, continue to practice low value care because of practice habits and lack of cost transparency. In keeping with the spirit of the journal’s series, three low-value practices were highlighted in this HM18 session, including the benefits of high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy, the value of serum albumin and prealbumin in malnutrition, and the use of nebulized versus inhaler albuterol.

HFNC oxygen therapy has become a widespread practice internationally, with large variations in implementation across all age ranges. In bronchiolitic infants, variations in time of implementation, duration of therapy, weaning policies, and outcome measures have yielded mixed results to date. Many studies are still underway, but current literature has not shown significant benefits of starting HFNC early in the illness process, and infants receiving HFNC have not had better outcomes than those who received standard therapy (low-flow nasal cannula).

Serum albumin and prealbumin are often cited as markers of malnutrition. In patients on tube feeds, such as those with cerebral palsy and complex medical conditions, current literature shows no benefit in the use of these lab markers for screening or for following to assess improvement. In addition, patients with eating disorders do not have significant correlation of their nutritive status with these markers. Therefore, the use of these labs for screening of malnutrition is of little if any value.

Finally, when comparing albuterol delivery systems, there has been no proof that nebulized albuterol is any better than metered dose inhalers (MDI) in its effect. As long as appropriate dosing of MDIs is done, the benefits are the same. In addition, side effects are fewer, and the length of stay in the ED is shorter. The more a family uses MDI inhalers, the better their technique. Studies have shown it takes approximately three attempts at using an MDI to get the technique correct, so inpatient MDI use would also decrease user error in the outpatient setting.

Key takeaways for HM

- Practice habits, lack of transparency of costs, and regional training lead to low value care practices.

- Early introduction of high-flow nasal cannula in hospitalization of an infant with bronchiolitis has not been shown to decrease length of stay or severity outcomes, according to currently available data.

- Serum albumin and prealbumin have little to no benefit in screening of malnutrition.

- Nebulized albuterol has not been proven to be more beneficial that MDI albuterol at appropriate doses.

- Repeat MDI administration has been shown to positively affect user administration techniques.

- MDI albuterol use has fewer side effects and decreased ED length of stay, compared with nebulized albuterol.

Dr. Schwenk is an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and a pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital, Louisville.

Hospitalist movers and shakers – July 2018

Steven Pantilat, MD, MHM, has been named the first chief of the newly established division of palliative medicine at University of California, San Francisco Health. Dr. Pantilat’s new role commenced on May 1st, with the division launch anticipated for July 1st.

Dr. Pantilat is a Master of the Society of Hospital Medicine and a former president of the society (2005-2006).

Gary J. Carver, MD, recently was named the chief medical officer at Coshocton (Ohio) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Carver has been the hospital’s director of hospital medicine since 2013 and will continue in that role in addition to his duties as CMO.

In his new position, Dr. Carver joins Coshocton Medical Center’s senior leadership team, providing medical oversight, as well as clinical direction and leadership as the facility seeks accreditation, quality improvement, and service line development.

Lisa Shah, MD, has been hired by Sound Physicians as the group’s chief innovation officer. Dr. Shah had been working as senior vice president of Evolent Health’s clinical operations and network. With Sound Physicians, Dr. Shah will lead clinical innovation and transformation for the nationwide organization of physicians providing emergency medical, critical care, and hospital medicine services at more than 180 hospitals.

Dr. Shah will be tasked with developing innovative care models, tech-centered clinical workflows, and telemedicine strategies. She brings a robust hospital medicine background, having served in a 2-year Hospitalist Scholars Fellowship at the University of Chicago, while simultaneously earning a master’s degree in public health.

BUSINESS MOVES

The University of Mississippi Medical Center Children’s of Mississippi, Hattiesburg, branch is joining forces with Memorial Hospital at Gulfport (Miss.) to provide care throughout southern Mississippi.

The highlight of the merger is the acquisition of six pediatric clinics into the UMMC family, with UMMC assuming control of the pediatric hospitalist program at each of the locations. The acquired clinics all have been branded as Children’s of Mississippi as of March 26th.

Sound Physicians’ parent company Fresenius Medical Care, which has held a controlling interest in Sound since 2014, has sold that interest to Germany-based Summit Partners for a reported $2.15 billion. The acquisition is expected to be finalized later this calendar year.

Sound, which reported revenues of approximately $1.5 billion in 2017, is optimistic that it can tap into new markets while under the Summit umbrella.

The Ob Hospitalist Group, Greenville, S.C., the nation’s largest Ob/Gyn hospitalist organization, recently announced the rollout of its CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery, and Encourage) program. CARE uses peer support to assist clinicians facing psychological and emotional impacts from adverse Ob events.

CARE peer counseling focuses on confidentiality, empathy, trust, and respect for colleagues suffering from a negative patient-care event. The program is available to more than 600 Ob hospitalist clinicians at more than 120 hospitals nationwide.

Steven Pantilat, MD, MHM, has been named the first chief of the newly established division of palliative medicine at University of California, San Francisco Health. Dr. Pantilat’s new role commenced on May 1st, with the division launch anticipated for July 1st.

Dr. Pantilat is a Master of the Society of Hospital Medicine and a former president of the society (2005-2006).

Gary J. Carver, MD, recently was named the chief medical officer at Coshocton (Ohio) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Carver has been the hospital’s director of hospital medicine since 2013 and will continue in that role in addition to his duties as CMO.

In his new position, Dr. Carver joins Coshocton Medical Center’s senior leadership team, providing medical oversight, as well as clinical direction and leadership as the facility seeks accreditation, quality improvement, and service line development.

Lisa Shah, MD, has been hired by Sound Physicians as the group’s chief innovation officer. Dr. Shah had been working as senior vice president of Evolent Health’s clinical operations and network. With Sound Physicians, Dr. Shah will lead clinical innovation and transformation for the nationwide organization of physicians providing emergency medical, critical care, and hospital medicine services at more than 180 hospitals.

Dr. Shah will be tasked with developing innovative care models, tech-centered clinical workflows, and telemedicine strategies. She brings a robust hospital medicine background, having served in a 2-year Hospitalist Scholars Fellowship at the University of Chicago, while simultaneously earning a master’s degree in public health.

BUSINESS MOVES

The University of Mississippi Medical Center Children’s of Mississippi, Hattiesburg, branch is joining forces with Memorial Hospital at Gulfport (Miss.) to provide care throughout southern Mississippi.

The highlight of the merger is the acquisition of six pediatric clinics into the UMMC family, with UMMC assuming control of the pediatric hospitalist program at each of the locations. The acquired clinics all have been branded as Children’s of Mississippi as of March 26th.

Sound Physicians’ parent company Fresenius Medical Care, which has held a controlling interest in Sound since 2014, has sold that interest to Germany-based Summit Partners for a reported $2.15 billion. The acquisition is expected to be finalized later this calendar year.

Sound, which reported revenues of approximately $1.5 billion in 2017, is optimistic that it can tap into new markets while under the Summit umbrella.

The Ob Hospitalist Group, Greenville, S.C., the nation’s largest Ob/Gyn hospitalist organization, recently announced the rollout of its CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery, and Encourage) program. CARE uses peer support to assist clinicians facing psychological and emotional impacts from adverse Ob events.

CARE peer counseling focuses on confidentiality, empathy, trust, and respect for colleagues suffering from a negative patient-care event. The program is available to more than 600 Ob hospitalist clinicians at more than 120 hospitals nationwide.

Steven Pantilat, MD, MHM, has been named the first chief of the newly established division of palliative medicine at University of California, San Francisco Health. Dr. Pantilat’s new role commenced on May 1st, with the division launch anticipated for July 1st.

Dr. Pantilat is a Master of the Society of Hospital Medicine and a former president of the society (2005-2006).

Gary J. Carver, MD, recently was named the chief medical officer at Coshocton (Ohio) Regional Medical Center. Dr. Carver has been the hospital’s director of hospital medicine since 2013 and will continue in that role in addition to his duties as CMO.

In his new position, Dr. Carver joins Coshocton Medical Center’s senior leadership team, providing medical oversight, as well as clinical direction and leadership as the facility seeks accreditation, quality improvement, and service line development.

Lisa Shah, MD, has been hired by Sound Physicians as the group’s chief innovation officer. Dr. Shah had been working as senior vice president of Evolent Health’s clinical operations and network. With Sound Physicians, Dr. Shah will lead clinical innovation and transformation for the nationwide organization of physicians providing emergency medical, critical care, and hospital medicine services at more than 180 hospitals.

Dr. Shah will be tasked with developing innovative care models, tech-centered clinical workflows, and telemedicine strategies. She brings a robust hospital medicine background, having served in a 2-year Hospitalist Scholars Fellowship at the University of Chicago, while simultaneously earning a master’s degree in public health.

BUSINESS MOVES

The University of Mississippi Medical Center Children’s of Mississippi, Hattiesburg, branch is joining forces with Memorial Hospital at Gulfport (Miss.) to provide care throughout southern Mississippi.

The highlight of the merger is the acquisition of six pediatric clinics into the UMMC family, with UMMC assuming control of the pediatric hospitalist program at each of the locations. The acquired clinics all have been branded as Children’s of Mississippi as of March 26th.

Sound Physicians’ parent company Fresenius Medical Care, which has held a controlling interest in Sound since 2014, has sold that interest to Germany-based Summit Partners for a reported $2.15 billion. The acquisition is expected to be finalized later this calendar year.

Sound, which reported revenues of approximately $1.5 billion in 2017, is optimistic that it can tap into new markets while under the Summit umbrella.

The Ob Hospitalist Group, Greenville, S.C., the nation’s largest Ob/Gyn hospitalist organization, recently announced the rollout of its CARE (Clinician Assistance, Recovery, and Encourage) program. CARE uses peer support to assist clinicians facing psychological and emotional impacts from adverse Ob events.

CARE peer counseling focuses on confidentiality, empathy, trust, and respect for colleagues suffering from a negative patient-care event. The program is available to more than 600 Ob hospitalist clinicians at more than 120 hospitals nationwide.

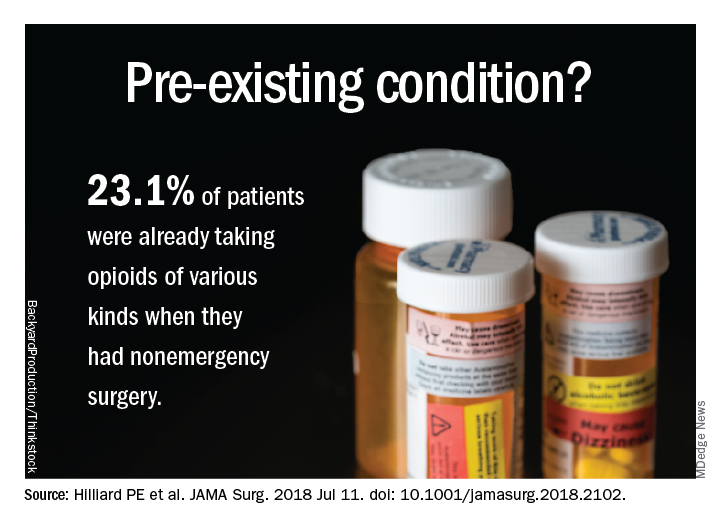

Nearly one-quarter of presurgery patients already using opioids

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. ... Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

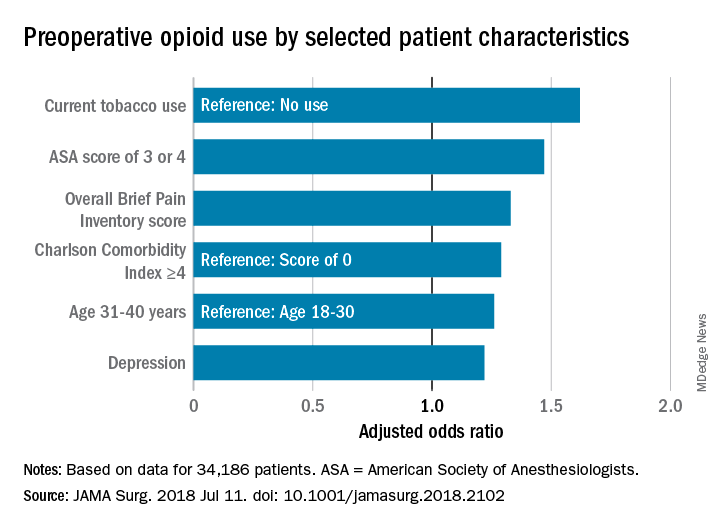

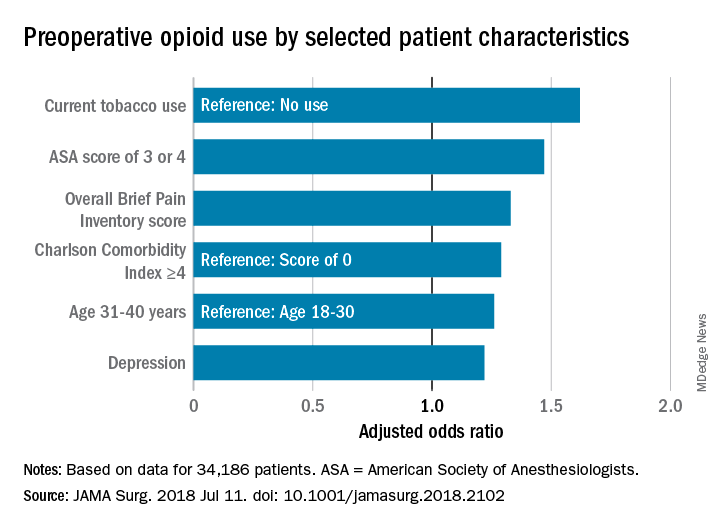

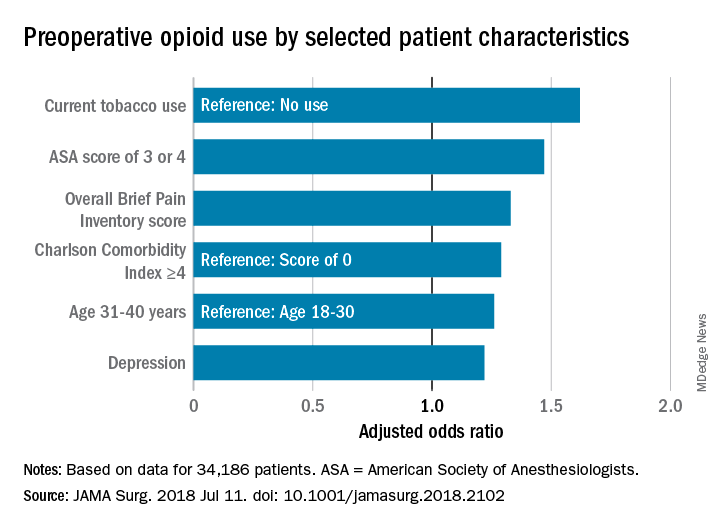

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).

The study also broke out the data by presurgery opioid usage and surgery service. Of patients having spine neurosurgery, 55.1% were already taking opioids, and among those having orthopedic spine surgery, 65.1% were taking opioids. General surgery patients were not among those mostly likely to be using opioids (gastrointestinal surgery, 19.3% and endocrine surgery 14.3%). “Certain surgical services may be more likely to encounter patients with high comorbidities for opioid use, and more targeted opioid education strategies aimed at those services may help to mitigate risk in the postoperative period,” the authors wrote.

“All surgeons should take a preop pain history. They should ask about current pain and previous pain experiences. They should also ask about a history of substance use disorder. This should lead into a discussion of the pain expectations from the procedure. Patients should expect to be in pain, that is normal. Pain-free surgery is rare. If a patient has a complex pain history or takes chronic opioids, the surgeon should consider referring them to anesthesia for formal preop pain management planning and potentially weaning of opioid dose prior to elective surgery,” noted Dr. Englesbe, the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., MD and Cyrenus G Darling Jr., MD Professor of Surgery, and faculty at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Surgeons are likely to see patients with a past history of opioid dependence or who are recovering from substance abuse. “Every effort should be made to avoid opioids in these patients. We have developed a Pain Optimization Pathway which facilitates no postoperative opioids for these and other patients. These patients are at high risk to relapse and surgeons must know who these patients are so they can provide optimal care,” Dr. Englesbe added.The limitations of this study as reported by the authors include the single-center design, the nondiverse racial makeup of the sample, and the difficulty of ascertaining the dosing and duration of opioid use, both prescription and illegal.

The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

SOURCE: Hilliard PE et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. ... Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).

The study also broke out the data by presurgery opioid usage and surgery service. Of patients having spine neurosurgery, 55.1% were already taking opioids, and among those having orthopedic spine surgery, 65.1% were taking opioids. General surgery patients were not among those mostly likely to be using opioids (gastrointestinal surgery, 19.3% and endocrine surgery 14.3%). “Certain surgical services may be more likely to encounter patients with high comorbidities for opioid use, and more targeted opioid education strategies aimed at those services may help to mitigate risk in the postoperative period,” the authors wrote.

“All surgeons should take a preop pain history. They should ask about current pain and previous pain experiences. They should also ask about a history of substance use disorder. This should lead into a discussion of the pain expectations from the procedure. Patients should expect to be in pain, that is normal. Pain-free surgery is rare. If a patient has a complex pain history or takes chronic opioids, the surgeon should consider referring them to anesthesia for formal preop pain management planning and potentially weaning of opioid dose prior to elective surgery,” noted Dr. Englesbe, the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., MD and Cyrenus G Darling Jr., MD Professor of Surgery, and faculty at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Surgeons are likely to see patients with a past history of opioid dependence or who are recovering from substance abuse. “Every effort should be made to avoid opioids in these patients. We have developed a Pain Optimization Pathway which facilitates no postoperative opioids for these and other patients. These patients are at high risk to relapse and surgeons must know who these patients are so they can provide optimal care,” Dr. Englesbe added.The limitations of this study as reported by the authors include the single-center design, the nondiverse racial makeup of the sample, and the difficulty of ascertaining the dosing and duration of opioid use, both prescription and illegal.

The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

SOURCE: Hilliard PE et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

at a large academic medical center, a cross-sectional observational study has determined.

Prescription or illegal opioid use can have profound implications for surgical outcomes and continued postoperative medication abuse. “Preoperative opioid use was associated with a greater burden of comorbid disease and multiple risk factors for poor recovery. ... Opioid-tolerant patients are at risk for opioid-associated adverse events and are less likely to discontinue opioid-based therapy after their surgery,” wrote Paul E. Hilliard, MD, and a team of researchers at the University of Michigan Health System. Although the question of preoperative opioid use has been examined and the Michigan findings are consistent with earlier estimates of prevalence (Ann Surg. 2017;265[4]:695-701), this study sought a more detailed profile of both the characteristics of these patients and the types of procedures correlated with opioid use.

Patient data were derived primarily from two ongoing institutional registries, the Michigan Genomics Initiative and the Analgesic Outcomes Study. Each of these projects involved recruiting nonemergency surgery patients to participate and self-report on pain and affect issues. Opioid use data were extracted from the preop anesthesia history and from physical examination. A total of 34,186 patients were recruited for this study; 54.2% were women, 89.1% were white, and the mean age was 53.1 years. Overall, 23.1% of these patients were taking opioids of various kinds, mostly by prescription along with nonprescription opioids and illegal drugs of other kinds.

The most common opioids found in this patient sample were hydrocodone bitartrate (59.4%), tramadol hydrochloride (21.2%) and oxycodone hydrochloride (18.5%), although the duration or frequency of use was not determined.

“In our experience, in surveys like this patients are pretty honest. [The data do not] track to their medical record, but was done privately for research. That having been said, I am sure there is significant underreporting,” study coauthor Michael J. Englesbe, MD, FACS, said in an interview. In addition to some nondisclosure by study participants, the exclusion of patients admitted to surgery from the ED could mean that 23.1% is a conservative estimate, he noted.

Patient characteristics included in the study (tobacco use, alcohol use, sleep apnea, pain, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety) were self-reported and validated using tools such as the Brief Pain Inventory, the Fibromyalgia Survey, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Procedural data were derived from patient records and ICD-10 data and rated via the ASA score and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

A multivariate analysis of patient characteristics found that age between 31 and 40, tobacco use, heavy alcohol use, pain score, depression, comorbidities reflected in a higher ASA score, and Charlson Comorbidity Score were all significant risk factors for presurgical opiate use.

Patients who were scheduled for surgical procedures involving lower extremities (adjusted odds ratio 3.61, 95% confidence interval, 2.81-4.64) were at the highest risk for opioid use, followed by pelvis surgery, excluding hip (aOR, 3.09, 95% CI, 1.88-5.08), upper arm or elbow (aOR, 3.07, 95% CI, 2.12-4.45), and spine surgery (aOR, 2.68, 95% CI, 2.15-3.32).

The study also broke out the data by presurgery opioid usage and surgery service. Of patients having spine neurosurgery, 55.1% were already taking opioids, and among those having orthopedic spine surgery, 65.1% were taking opioids. General surgery patients were not among those mostly likely to be using opioids (gastrointestinal surgery, 19.3% and endocrine surgery 14.3%). “Certain surgical services may be more likely to encounter patients with high comorbidities for opioid use, and more targeted opioid education strategies aimed at those services may help to mitigate risk in the postoperative period,” the authors wrote.

“All surgeons should take a preop pain history. They should ask about current pain and previous pain experiences. They should also ask about a history of substance use disorder. This should lead into a discussion of the pain expectations from the procedure. Patients should expect to be in pain, that is normal. Pain-free surgery is rare. If a patient has a complex pain history or takes chronic opioids, the surgeon should consider referring them to anesthesia for formal preop pain management planning and potentially weaning of opioid dose prior to elective surgery,” noted Dr. Englesbe, the Cyrenus G. Darling Sr., MD and Cyrenus G Darling Jr., MD Professor of Surgery, and faculty at the Center for Healthcare Outcomes & Policy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Surgeons are likely to see patients with a past history of opioid dependence or who are recovering from substance abuse. “Every effort should be made to avoid opioids in these patients. We have developed a Pain Optimization Pathway which facilitates no postoperative opioids for these and other patients. These patients are at high risk to relapse and surgeons must know who these patients are so they can provide optimal care,” Dr. Englesbe added.The limitations of this study as reported by the authors include the single-center design, the nondiverse racial makeup of the sample, and the difficulty of ascertaining the dosing and duration of opioid use, both prescription and illegal.

The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

SOURCE: Hilliard PE et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Key clinical point: Preoperative opioid use is prevalent in patients who are having spinal surgery and have depression.

Major finding:

Study details: An observational study of 34,186 surgical patients in the University of Michigan Health system.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no disclosures relevant to this study. This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, the American College of Surgeons, and other noncommercial sources.

Source: Hilliard P E et al. JAMA Surg. 2018 Jul 11;. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2102.

CMS considers expanding telemedicine payments

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

Better ICU staff communication with family may improve end-of-life choices

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.