User login

Exercise halves T2D risk in adults with obesity

“Physical exercise combined with diet restriction has been proven to be effective in prevention of diabetes. However, the long-term effect of exercise on prevention of diabetes, and the difference of exercise intensity in prevention of diabetes have not been well studied,” said corresponding author Xiaoying Li, MD, of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, in an interview.

In the research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Li and colleagues analyzed the results of a study of 220 adults with central obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but no incident diabetes, randomized to a 12-month program of vigorous exercise (73 patients), moderate aerobic exercise (73 patients) or no exercise (74 patients).

A total of 208 participants completed the 1-year intervention; of these, 195 and 178 remained to provide data at 2 years and 10 years, respectively. The mean age of the participants was 53.9 years, 32.3% were male, and the mean waist circumference was 96.1 cm at baseline.

The cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes in the vigorous exercise, moderate exercise, and nonexercise groups was 2.1 per 100 person-years 1.9 per 100 person-years, and 4.1 per 100 person-years, respectively, over the 10-year follow-up period. This translated to a reduction in type 2 diabetes risk of 49% in the vigorous exercise group and 53% in the moderate exercise group compared with the nonexercise group.

In addition, individuals in the vigorous and moderate exercise groups significantly reduced their HbA1c and waist circumference compared with the nonexercisers. Levels of plasma fasting glucose and weight regain were lower in both exercise groups compared with nonexercisers, but these differences were not significant.

The exercise intervention was described in a 2016 study, which was also published in JAMA Internal Medicine. That study’s purpose was to compare the effects of exercise on patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Participants were coached and supervised for their exercise programs. The program for the vigorous group involved jogging for 150 minutes per week at 65%-80% of maximum heart rate for 6 months and brisk walking 150 minutes per week at 45%-55% of maximum heart rate for another 6 months. The program for the moderate exercise group involved brisk walking 150 minutes per week for 12 months.

Both exercise groups showed a trend towards higher levels of leisure time physical activity after 10 years compared with the nonexercise groups, although the difference was not significant.

The main limitation of the study was that incident prediabetes was not prespecified, which may have led to some confounding, the researchers noted. In addition, the participants were highly supervised for a 12-month program only. However, the results support the long-term value of physical exercise as a method of obesity management and to delay progression to type 2 diabetes in obese individuals, they said. Vigorous and moderate aerobic exercise programs could be implemented for this patient population, they concluded.

“Surprisingly, our findings demonstrated that a 12-month vigorous aerobic exercise or moderate aerobic exercise could significantly reduce the risk of incident diabetes by 50% over the 10-year follow-up,” Dr. Li said in an interview. The results suggest that physical exercise for some period of time can produce a long-term beneficial effect in prevention of type 2 diabetes, he said.

Potential barriers to the routine use of an exercise intervention in patients with obesity include the unwillingness of this population to engage in vigorous exercise, and the potential for musculoskeletal injury, said Dr. Li. In these cases, obese patients should be encouraged to pursue moderate exercise, Dr. Li said.

Looking ahead, more research is needed to examine the potential mechanism behind the effect of exercise on diabetes prevention, said Dr. Li.

Findings fill gap in long-term outcome data

The current study is important because of the long-term follow-up data, said Jill Kanaley, PhD, professor and interim chair of nutrition and exercise physiology at the University of Missouri, in an interview. “We seldom follow up on our training studies, thus it is important to see if there is any long-term impact of these interventions,” she said.

Dr. Kanaley said she was surprised to see the residual benefits of the exercise intervention 10 years later.

“We often wonder how long the impact of the exercise training will stay with someone so that they continue to exercise and watch their weight; this study seems to indicate that there is an educational component that stays with them,” she said.

The main clinical takeaway from the current study was the minimal weight gain over time, Dr. Kanaley said.

Although time may be a barrier to the routine use of an exercise intervention, patients have to realize that they can usually find the time, especially given the multiple benefits, said Dr. Kanaley. “The exercise interventions provide more benefits than just weight control and glucose levels,” she said.

“The 30-60 minutes of exercise does not have to come all at the same time,” Dr. Kanaley noted. “It could be three 15-minute bouts of exercise/physical activity to get their 45 minutes in,” she noted. Exercise does not have to be heavy vigorous exercise, even walking is beneficial, she said. For people who complain of boredom with an exercise routine, Dr. Kanaley encourages mixing it up, with activities such as different exercise classes, running, or walking on a different day of any given week.

Although the current study was conducted in China, the findings may translate to a U.S. population, Dr. Kanaley said in an interview. However, “frequently our Western diet is less healthy than the traditional Chinese diet. This may have provided an immeasurable benefit to these subjects,” although study participants did not make specific adjustments to their diets, she said.

Additional research is needed to confirm the findings, said Dr. Kanaley. “Ideally, the study should be repeated in a population with a Western diet,” she noted.

Next steps for research include maintenance of activity

Evidence on the long-term benefits of exercise programs is limited, said Amanda Paluch, PhD, a physical activity epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in an interview.

“Chronic diseases such as diabetes can take years to develop, so understanding these important health outcomes requires years of follow-up. This study followed their study participants for 10 years, which gives us a nice glimpse of the long-term benefits of exercise training on diabetes prevention,” she said.

Data from previous observational studies of individuals’ current activity levels (without an intervention) suggest that adults who are more physically active have a lower risk of diabetes over time, said Dr. Paluch. However, the current study is one of the few with rigorous exercise interventions with extensive follow-up on diabetes risk, and it provides important evidence that a 12-month structured exercise program in inactive adults with obesity can result in meaningful long-term health benefits by lowering the risk of diabetes, she said.

“The individuals in the current study participated in a structured exercise program where their exercise sessions were supervised and coached,” Dr. Paluch noted. “Having a personalized coach may not be within the budget or time constraints for many people,” she said. Her message to clinicians for their patients: “When looking to start an exercise routine, identify an activity you enjoy and find feasible to fit into your existing life and schedule,” she said.

“Although this study was conducted in China, the results are meaningful for the U.S. population, as we would expect the physiological benefit of exercise to be consistent across various populations,” Dr. Paluch said. “However, there are certainly differences across countries at the individual level to the larger community-wide level that may influence a person’s ability to maintain physical activity and prevent diabetes, so replicating similar studies in other countries, including the U.S., would be of value.”

“Additionally, we need more research on how to encourage maintenance of physical activity in the long-term, after the initial exercise program is over,” she said.

“From this current study, we cannot tease out whether diabetes risk is reduced because of the 12-month exercise intervention or the benefit is from maintaining physical activity regularly over the 10 years of follow-up, or a combination of the two,” said Dr. Paluch. Future studies should consider teasing out participants who were only active during the exercise intervention, then ceased being active vs. participants who continued with vigorous activity long-term, she said.

The study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project. The researchers, Dr. Kanaley, and Dr. Paluch had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Physical exercise combined with diet restriction has been proven to be effective in prevention of diabetes. However, the long-term effect of exercise on prevention of diabetes, and the difference of exercise intensity in prevention of diabetes have not been well studied,” said corresponding author Xiaoying Li, MD, of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, in an interview.

In the research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Li and colleagues analyzed the results of a study of 220 adults with central obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but no incident diabetes, randomized to a 12-month program of vigorous exercise (73 patients), moderate aerobic exercise (73 patients) or no exercise (74 patients).

A total of 208 participants completed the 1-year intervention; of these, 195 and 178 remained to provide data at 2 years and 10 years, respectively. The mean age of the participants was 53.9 years, 32.3% were male, and the mean waist circumference was 96.1 cm at baseline.

The cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes in the vigorous exercise, moderate exercise, and nonexercise groups was 2.1 per 100 person-years 1.9 per 100 person-years, and 4.1 per 100 person-years, respectively, over the 10-year follow-up period. This translated to a reduction in type 2 diabetes risk of 49% in the vigorous exercise group and 53% in the moderate exercise group compared with the nonexercise group.

In addition, individuals in the vigorous and moderate exercise groups significantly reduced their HbA1c and waist circumference compared with the nonexercisers. Levels of plasma fasting glucose and weight regain were lower in both exercise groups compared with nonexercisers, but these differences were not significant.

The exercise intervention was described in a 2016 study, which was also published in JAMA Internal Medicine. That study’s purpose was to compare the effects of exercise on patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Participants were coached and supervised for their exercise programs. The program for the vigorous group involved jogging for 150 minutes per week at 65%-80% of maximum heart rate for 6 months and brisk walking 150 minutes per week at 45%-55% of maximum heart rate for another 6 months. The program for the moderate exercise group involved brisk walking 150 minutes per week for 12 months.

Both exercise groups showed a trend towards higher levels of leisure time physical activity after 10 years compared with the nonexercise groups, although the difference was not significant.

The main limitation of the study was that incident prediabetes was not prespecified, which may have led to some confounding, the researchers noted. In addition, the participants were highly supervised for a 12-month program only. However, the results support the long-term value of physical exercise as a method of obesity management and to delay progression to type 2 diabetes in obese individuals, they said. Vigorous and moderate aerobic exercise programs could be implemented for this patient population, they concluded.

“Surprisingly, our findings demonstrated that a 12-month vigorous aerobic exercise or moderate aerobic exercise could significantly reduce the risk of incident diabetes by 50% over the 10-year follow-up,” Dr. Li said in an interview. The results suggest that physical exercise for some period of time can produce a long-term beneficial effect in prevention of type 2 diabetes, he said.

Potential barriers to the routine use of an exercise intervention in patients with obesity include the unwillingness of this population to engage in vigorous exercise, and the potential for musculoskeletal injury, said Dr. Li. In these cases, obese patients should be encouraged to pursue moderate exercise, Dr. Li said.

Looking ahead, more research is needed to examine the potential mechanism behind the effect of exercise on diabetes prevention, said Dr. Li.

Findings fill gap in long-term outcome data

The current study is important because of the long-term follow-up data, said Jill Kanaley, PhD, professor and interim chair of nutrition and exercise physiology at the University of Missouri, in an interview. “We seldom follow up on our training studies, thus it is important to see if there is any long-term impact of these interventions,” she said.

Dr. Kanaley said she was surprised to see the residual benefits of the exercise intervention 10 years later.

“We often wonder how long the impact of the exercise training will stay with someone so that they continue to exercise and watch their weight; this study seems to indicate that there is an educational component that stays with them,” she said.

The main clinical takeaway from the current study was the minimal weight gain over time, Dr. Kanaley said.

Although time may be a barrier to the routine use of an exercise intervention, patients have to realize that they can usually find the time, especially given the multiple benefits, said Dr. Kanaley. “The exercise interventions provide more benefits than just weight control and glucose levels,” she said.

“The 30-60 minutes of exercise does not have to come all at the same time,” Dr. Kanaley noted. “It could be three 15-minute bouts of exercise/physical activity to get their 45 minutes in,” she noted. Exercise does not have to be heavy vigorous exercise, even walking is beneficial, she said. For people who complain of boredom with an exercise routine, Dr. Kanaley encourages mixing it up, with activities such as different exercise classes, running, or walking on a different day of any given week.

Although the current study was conducted in China, the findings may translate to a U.S. population, Dr. Kanaley said in an interview. However, “frequently our Western diet is less healthy than the traditional Chinese diet. This may have provided an immeasurable benefit to these subjects,” although study participants did not make specific adjustments to their diets, she said.

Additional research is needed to confirm the findings, said Dr. Kanaley. “Ideally, the study should be repeated in a population with a Western diet,” she noted.

Next steps for research include maintenance of activity

Evidence on the long-term benefits of exercise programs is limited, said Amanda Paluch, PhD, a physical activity epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in an interview.

“Chronic diseases such as diabetes can take years to develop, so understanding these important health outcomes requires years of follow-up. This study followed their study participants for 10 years, which gives us a nice glimpse of the long-term benefits of exercise training on diabetes prevention,” she said.

Data from previous observational studies of individuals’ current activity levels (without an intervention) suggest that adults who are more physically active have a lower risk of diabetes over time, said Dr. Paluch. However, the current study is one of the few with rigorous exercise interventions with extensive follow-up on diabetes risk, and it provides important evidence that a 12-month structured exercise program in inactive adults with obesity can result in meaningful long-term health benefits by lowering the risk of diabetes, she said.

“The individuals in the current study participated in a structured exercise program where their exercise sessions were supervised and coached,” Dr. Paluch noted. “Having a personalized coach may not be within the budget or time constraints for many people,” she said. Her message to clinicians for their patients: “When looking to start an exercise routine, identify an activity you enjoy and find feasible to fit into your existing life and schedule,” she said.

“Although this study was conducted in China, the results are meaningful for the U.S. population, as we would expect the physiological benefit of exercise to be consistent across various populations,” Dr. Paluch said. “However, there are certainly differences across countries at the individual level to the larger community-wide level that may influence a person’s ability to maintain physical activity and prevent diabetes, so replicating similar studies in other countries, including the U.S., would be of value.”

“Additionally, we need more research on how to encourage maintenance of physical activity in the long-term, after the initial exercise program is over,” she said.

“From this current study, we cannot tease out whether diabetes risk is reduced because of the 12-month exercise intervention or the benefit is from maintaining physical activity regularly over the 10 years of follow-up, or a combination of the two,” said Dr. Paluch. Future studies should consider teasing out participants who were only active during the exercise intervention, then ceased being active vs. participants who continued with vigorous activity long-term, she said.

The study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project. The researchers, Dr. Kanaley, and Dr. Paluch had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Physical exercise combined with diet restriction has been proven to be effective in prevention of diabetes. However, the long-term effect of exercise on prevention of diabetes, and the difference of exercise intensity in prevention of diabetes have not been well studied,” said corresponding author Xiaoying Li, MD, of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, in an interview.

In the research letter published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dr. Li and colleagues analyzed the results of a study of 220 adults with central obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, but no incident diabetes, randomized to a 12-month program of vigorous exercise (73 patients), moderate aerobic exercise (73 patients) or no exercise (74 patients).

A total of 208 participants completed the 1-year intervention; of these, 195 and 178 remained to provide data at 2 years and 10 years, respectively. The mean age of the participants was 53.9 years, 32.3% were male, and the mean waist circumference was 96.1 cm at baseline.

The cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes in the vigorous exercise, moderate exercise, and nonexercise groups was 2.1 per 100 person-years 1.9 per 100 person-years, and 4.1 per 100 person-years, respectively, over the 10-year follow-up period. This translated to a reduction in type 2 diabetes risk of 49% in the vigorous exercise group and 53% in the moderate exercise group compared with the nonexercise group.

In addition, individuals in the vigorous and moderate exercise groups significantly reduced their HbA1c and waist circumference compared with the nonexercisers. Levels of plasma fasting glucose and weight regain were lower in both exercise groups compared with nonexercisers, but these differences were not significant.

The exercise intervention was described in a 2016 study, which was also published in JAMA Internal Medicine. That study’s purpose was to compare the effects of exercise on patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Participants were coached and supervised for their exercise programs. The program for the vigorous group involved jogging for 150 minutes per week at 65%-80% of maximum heart rate for 6 months and brisk walking 150 minutes per week at 45%-55% of maximum heart rate for another 6 months. The program for the moderate exercise group involved brisk walking 150 minutes per week for 12 months.

Both exercise groups showed a trend towards higher levels of leisure time physical activity after 10 years compared with the nonexercise groups, although the difference was not significant.

The main limitation of the study was that incident prediabetes was not prespecified, which may have led to some confounding, the researchers noted. In addition, the participants were highly supervised for a 12-month program only. However, the results support the long-term value of physical exercise as a method of obesity management and to delay progression to type 2 diabetes in obese individuals, they said. Vigorous and moderate aerobic exercise programs could be implemented for this patient population, they concluded.

“Surprisingly, our findings demonstrated that a 12-month vigorous aerobic exercise or moderate aerobic exercise could significantly reduce the risk of incident diabetes by 50% over the 10-year follow-up,” Dr. Li said in an interview. The results suggest that physical exercise for some period of time can produce a long-term beneficial effect in prevention of type 2 diabetes, he said.

Potential barriers to the routine use of an exercise intervention in patients with obesity include the unwillingness of this population to engage in vigorous exercise, and the potential for musculoskeletal injury, said Dr. Li. In these cases, obese patients should be encouraged to pursue moderate exercise, Dr. Li said.

Looking ahead, more research is needed to examine the potential mechanism behind the effect of exercise on diabetes prevention, said Dr. Li.

Findings fill gap in long-term outcome data

The current study is important because of the long-term follow-up data, said Jill Kanaley, PhD, professor and interim chair of nutrition and exercise physiology at the University of Missouri, in an interview. “We seldom follow up on our training studies, thus it is important to see if there is any long-term impact of these interventions,” she said.

Dr. Kanaley said she was surprised to see the residual benefits of the exercise intervention 10 years later.

“We often wonder how long the impact of the exercise training will stay with someone so that they continue to exercise and watch their weight; this study seems to indicate that there is an educational component that stays with them,” she said.

The main clinical takeaway from the current study was the minimal weight gain over time, Dr. Kanaley said.

Although time may be a barrier to the routine use of an exercise intervention, patients have to realize that they can usually find the time, especially given the multiple benefits, said Dr. Kanaley. “The exercise interventions provide more benefits than just weight control and glucose levels,” she said.

“The 30-60 minutes of exercise does not have to come all at the same time,” Dr. Kanaley noted. “It could be three 15-minute bouts of exercise/physical activity to get their 45 minutes in,” she noted. Exercise does not have to be heavy vigorous exercise, even walking is beneficial, she said. For people who complain of boredom with an exercise routine, Dr. Kanaley encourages mixing it up, with activities such as different exercise classes, running, or walking on a different day of any given week.

Although the current study was conducted in China, the findings may translate to a U.S. population, Dr. Kanaley said in an interview. However, “frequently our Western diet is less healthy than the traditional Chinese diet. This may have provided an immeasurable benefit to these subjects,” although study participants did not make specific adjustments to their diets, she said.

Additional research is needed to confirm the findings, said Dr. Kanaley. “Ideally, the study should be repeated in a population with a Western diet,” she noted.

Next steps for research include maintenance of activity

Evidence on the long-term benefits of exercise programs is limited, said Amanda Paluch, PhD, a physical activity epidemiologist at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in an interview.

“Chronic diseases such as diabetes can take years to develop, so understanding these important health outcomes requires years of follow-up. This study followed their study participants for 10 years, which gives us a nice glimpse of the long-term benefits of exercise training on diabetes prevention,” she said.

Data from previous observational studies of individuals’ current activity levels (without an intervention) suggest that adults who are more physically active have a lower risk of diabetes over time, said Dr. Paluch. However, the current study is one of the few with rigorous exercise interventions with extensive follow-up on diabetes risk, and it provides important evidence that a 12-month structured exercise program in inactive adults with obesity can result in meaningful long-term health benefits by lowering the risk of diabetes, she said.

“The individuals in the current study participated in a structured exercise program where their exercise sessions were supervised and coached,” Dr. Paluch noted. “Having a personalized coach may not be within the budget or time constraints for many people,” she said. Her message to clinicians for their patients: “When looking to start an exercise routine, identify an activity you enjoy and find feasible to fit into your existing life and schedule,” she said.

“Although this study was conducted in China, the results are meaningful for the U.S. population, as we would expect the physiological benefit of exercise to be consistent across various populations,” Dr. Paluch said. “However, there are certainly differences across countries at the individual level to the larger community-wide level that may influence a person’s ability to maintain physical activity and prevent diabetes, so replicating similar studies in other countries, including the U.S., would be of value.”

“Additionally, we need more research on how to encourage maintenance of physical activity in the long-term, after the initial exercise program is over,” she said.

“From this current study, we cannot tease out whether diabetes risk is reduced because of the 12-month exercise intervention or the benefit is from maintaining physical activity regularly over the 10 years of follow-up, or a combination of the two,” said Dr. Paluch. Future studies should consider teasing out participants who were only active during the exercise intervention, then ceased being active vs. participants who continued with vigorous activity long-term, she said.

The study was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, and the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project. The researchers, Dr. Kanaley, and Dr. Paluch had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Running does not cause lasting cartilage damage

Running does not appear to cause sustained wear and tear of healthy knee cartilage, with research suggesting that the small, short-term changes to cartilage after a run reverse within hours.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in the most recent issue of Osteoarthritis and Cartilage presents the findings involving 396 adults, which compared the “before” and “after” state of healthy knee cartilage in runners.

Running is often thought to be detrimental to joint health, wrote Sally Coburn, PhD candidate at the La Trobe Sport & Exercise Medicine Research Centre at La Trobe University in Melbourne and coauthors, but this perception is not supported by evidence.

For the analysis, the researchers included studies that looked at either knee or hip cartilage using MRI to assess its size, shape, structure, and/or composition both in the 48 hours before a single bout of running and in the 48 hours after. The analysis aimed to include adults with or at risk of osteoarthritis, but only 57 of the 446 knees in the analysis fit these criteria.

In studies where participants underwent MRI within 20 minutes of running, there was an immediate postrun decrease in the volume of cartilage, ranging from –3.3% for weight-bearing femoral cartilage to –4.1% for tibial cartilage volume. This also revealed a decrease in T1 and T2 relaxation times, which are specialized MRI measures that reflect the composition of cartilage and which can indicate a breakdown of cartilage structure in the case of diseases such as arthritis.

Reversal of short-term cartilage changes

However, within 48 hours of the run, data from studies that repeated the MRIs more than once after the initial prerun scan suggested these changes reversed back to prerun levels.

“We were able to pool delayed T2 relaxation time measures from studies that repeated scans of the same participants 60 minutes and 91 minutes post-run and found no effect of running on tibiofemoral joint cartilage composition,” the authors write.

For example, one study in marathon runners found no difference in cartilage thickness in the tibiofemoral joint between baseline and at 2-10 hours and 12 hours after the marathon. Another showed the immediate post-run decrease in patellofemoral joint cartilage thickness had reverted back to prerun levels when the scan was repeated 24 hours after the run.

“The changes are very minimal and not inconsistent with what’s expected for your cartilage which is functioning normally,” Ms. Coburn told this news organization.

Sparse data in people with osteoarthritis

The authors said there were not enough data from individuals with osteoarthritis to be able to pool and quantify their cartilage changes. However, one study in the analysis found that cartilage lesions in people considered at risk of osteoarthritis because of prior anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction were unchanged after running.

Another suggested that the decrease in femoral cartilage volume recorded at 15 minutes persisted at 45 minutes, while a separate study found significantly increased T2 relaxation times at 45 minutes after a run in those with knee osteoarthritis but not in those without osteoarthritis.

Senior author Adam Culvenor, PhD, senior research fellow at the La Trobe Centre, said their analysis suggested running was healthy, with small changes in cartilage that resolve quickly, but “we really don’t know yet if running is safe for people with osteoarthritis,” he said. “We need much more work in that space.”

Overall, the study evidence was rated as being of low certainty, which Dr. Coburn said was related to the small numbers in each study, which in turn relates to the cost and logistical challenges of the specialized MRI scan used.

“Study of a repeated exposure over a long duration of time on a disease that has a long natural history, like osteoarthritis, is challenging in that most funding agencies will not fund studies longer than 5 years,” Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo, MD, of the department of immunology, allergy, and rheumatology at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said in an email.

Dr. Lo, who was not involved with this review and meta-analysis, said there are still concerns about the effect of running on knee osteoarthritis among those with the disease, although there are some data to suggest that among those who self-select to run, there are no negative outcomes for the knee.

An accompanying editorial noted that research into the effect of running on those with osteoarthritis was still in its infancy. “This would help to guide clinical practice on how to support people with osteoarthritis, with regard to accessing the health benefits of running participation,” write Jean-Francois Esculier, PT, PhD, from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and Christian Barton, PhD, with the La Trobe Centre, pointing out there were a lack of evidence-based clinical recommendations for people with osteoarthritis who want to start or continue running.

It’s a question that PhD candidate Michaela Khan, MSc, is trying to answer at the University of British Columbia. “Our lab did a pilot study for my current study now, and they found that osteoarthritic cartilage took a little bit longer to recover than their healthy counterparts,” Ms. Khan said. Her research is suggesting that people with osteoarthritis not only can run, but even those with severe disease, who might be candidates for knee replacement, can run long distances.

Commenting on the analysis, Ms. Khan said the main take-home message was that healthy cartilage seems to recover after running, and that there is not an ongoing effect of ‘wear and tear.’

“That’s changing the narrative that if you keep running, it will wear away your cartilage, it’ll hurt your knees,” she said. “Now, we have a good synthesis of scientific evidence to prove maybe otherwise.”

Ms. Coburn and Dr. Culvenor report grant support from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, and another author reports grant support from the U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors, as well as Dr. Lo and Ms. Khan, report relevant financial relationships.

Running does not appear to cause sustained wear and tear of healthy knee cartilage, with research suggesting that the small, short-term changes to cartilage after a run reverse within hours.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in the most recent issue of Osteoarthritis and Cartilage presents the findings involving 396 adults, which compared the “before” and “after” state of healthy knee cartilage in runners.

Running is often thought to be detrimental to joint health, wrote Sally Coburn, PhD candidate at the La Trobe Sport & Exercise Medicine Research Centre at La Trobe University in Melbourne and coauthors, but this perception is not supported by evidence.

For the analysis, the researchers included studies that looked at either knee or hip cartilage using MRI to assess its size, shape, structure, and/or composition both in the 48 hours before a single bout of running and in the 48 hours after. The analysis aimed to include adults with or at risk of osteoarthritis, but only 57 of the 446 knees in the analysis fit these criteria.

In studies where participants underwent MRI within 20 minutes of running, there was an immediate postrun decrease in the volume of cartilage, ranging from –3.3% for weight-bearing femoral cartilage to –4.1% for tibial cartilage volume. This also revealed a decrease in T1 and T2 relaxation times, which are specialized MRI measures that reflect the composition of cartilage and which can indicate a breakdown of cartilage structure in the case of diseases such as arthritis.

Reversal of short-term cartilage changes

However, within 48 hours of the run, data from studies that repeated the MRIs more than once after the initial prerun scan suggested these changes reversed back to prerun levels.

“We were able to pool delayed T2 relaxation time measures from studies that repeated scans of the same participants 60 minutes and 91 minutes post-run and found no effect of running on tibiofemoral joint cartilage composition,” the authors write.

For example, one study in marathon runners found no difference in cartilage thickness in the tibiofemoral joint between baseline and at 2-10 hours and 12 hours after the marathon. Another showed the immediate post-run decrease in patellofemoral joint cartilage thickness had reverted back to prerun levels when the scan was repeated 24 hours after the run.

“The changes are very minimal and not inconsistent with what’s expected for your cartilage which is functioning normally,” Ms. Coburn told this news organization.

Sparse data in people with osteoarthritis

The authors said there were not enough data from individuals with osteoarthritis to be able to pool and quantify their cartilage changes. However, one study in the analysis found that cartilage lesions in people considered at risk of osteoarthritis because of prior anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction were unchanged after running.

Another suggested that the decrease in femoral cartilage volume recorded at 15 minutes persisted at 45 minutes, while a separate study found significantly increased T2 relaxation times at 45 minutes after a run in those with knee osteoarthritis but not in those without osteoarthritis.

Senior author Adam Culvenor, PhD, senior research fellow at the La Trobe Centre, said their analysis suggested running was healthy, with small changes in cartilage that resolve quickly, but “we really don’t know yet if running is safe for people with osteoarthritis,” he said. “We need much more work in that space.”

Overall, the study evidence was rated as being of low certainty, which Dr. Coburn said was related to the small numbers in each study, which in turn relates to the cost and logistical challenges of the specialized MRI scan used.

“Study of a repeated exposure over a long duration of time on a disease that has a long natural history, like osteoarthritis, is challenging in that most funding agencies will not fund studies longer than 5 years,” Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo, MD, of the department of immunology, allergy, and rheumatology at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said in an email.

Dr. Lo, who was not involved with this review and meta-analysis, said there are still concerns about the effect of running on knee osteoarthritis among those with the disease, although there are some data to suggest that among those who self-select to run, there are no negative outcomes for the knee.

An accompanying editorial noted that research into the effect of running on those with osteoarthritis was still in its infancy. “This would help to guide clinical practice on how to support people with osteoarthritis, with regard to accessing the health benefits of running participation,” write Jean-Francois Esculier, PT, PhD, from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and Christian Barton, PhD, with the La Trobe Centre, pointing out there were a lack of evidence-based clinical recommendations for people with osteoarthritis who want to start or continue running.

It’s a question that PhD candidate Michaela Khan, MSc, is trying to answer at the University of British Columbia. “Our lab did a pilot study for my current study now, and they found that osteoarthritic cartilage took a little bit longer to recover than their healthy counterparts,” Ms. Khan said. Her research is suggesting that people with osteoarthritis not only can run, but even those with severe disease, who might be candidates for knee replacement, can run long distances.

Commenting on the analysis, Ms. Khan said the main take-home message was that healthy cartilage seems to recover after running, and that there is not an ongoing effect of ‘wear and tear.’

“That’s changing the narrative that if you keep running, it will wear away your cartilage, it’ll hurt your knees,” she said. “Now, we have a good synthesis of scientific evidence to prove maybe otherwise.”

Ms. Coburn and Dr. Culvenor report grant support from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, and another author reports grant support from the U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors, as well as Dr. Lo and Ms. Khan, report relevant financial relationships.

Running does not appear to cause sustained wear and tear of healthy knee cartilage, with research suggesting that the small, short-term changes to cartilage after a run reverse within hours.

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in the most recent issue of Osteoarthritis and Cartilage presents the findings involving 396 adults, which compared the “before” and “after” state of healthy knee cartilage in runners.

Running is often thought to be detrimental to joint health, wrote Sally Coburn, PhD candidate at the La Trobe Sport & Exercise Medicine Research Centre at La Trobe University in Melbourne and coauthors, but this perception is not supported by evidence.

For the analysis, the researchers included studies that looked at either knee or hip cartilage using MRI to assess its size, shape, structure, and/or composition both in the 48 hours before a single bout of running and in the 48 hours after. The analysis aimed to include adults with or at risk of osteoarthritis, but only 57 of the 446 knees in the analysis fit these criteria.

In studies where participants underwent MRI within 20 minutes of running, there was an immediate postrun decrease in the volume of cartilage, ranging from –3.3% for weight-bearing femoral cartilage to –4.1% for tibial cartilage volume. This also revealed a decrease in T1 and T2 relaxation times, which are specialized MRI measures that reflect the composition of cartilage and which can indicate a breakdown of cartilage structure in the case of diseases such as arthritis.

Reversal of short-term cartilage changes

However, within 48 hours of the run, data from studies that repeated the MRIs more than once after the initial prerun scan suggested these changes reversed back to prerun levels.

“We were able to pool delayed T2 relaxation time measures from studies that repeated scans of the same participants 60 minutes and 91 minutes post-run and found no effect of running on tibiofemoral joint cartilage composition,” the authors write.

For example, one study in marathon runners found no difference in cartilage thickness in the tibiofemoral joint between baseline and at 2-10 hours and 12 hours after the marathon. Another showed the immediate post-run decrease in patellofemoral joint cartilage thickness had reverted back to prerun levels when the scan was repeated 24 hours after the run.

“The changes are very minimal and not inconsistent with what’s expected for your cartilage which is functioning normally,” Ms. Coburn told this news organization.

Sparse data in people with osteoarthritis

The authors said there were not enough data from individuals with osteoarthritis to be able to pool and quantify their cartilage changes. However, one study in the analysis found that cartilage lesions in people considered at risk of osteoarthritis because of prior anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction were unchanged after running.

Another suggested that the decrease in femoral cartilage volume recorded at 15 minutes persisted at 45 minutes, while a separate study found significantly increased T2 relaxation times at 45 minutes after a run in those with knee osteoarthritis but not in those without osteoarthritis.

Senior author Adam Culvenor, PhD, senior research fellow at the La Trobe Centre, said their analysis suggested running was healthy, with small changes in cartilage that resolve quickly, but “we really don’t know yet if running is safe for people with osteoarthritis,” he said. “We need much more work in that space.”

Overall, the study evidence was rated as being of low certainty, which Dr. Coburn said was related to the small numbers in each study, which in turn relates to the cost and logistical challenges of the specialized MRI scan used.

“Study of a repeated exposure over a long duration of time on a disease that has a long natural history, like osteoarthritis, is challenging in that most funding agencies will not fund studies longer than 5 years,” Grace Hsiao-Wei Lo, MD, of the department of immunology, allergy, and rheumatology at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, said in an email.

Dr. Lo, who was not involved with this review and meta-analysis, said there are still concerns about the effect of running on knee osteoarthritis among those with the disease, although there are some data to suggest that among those who self-select to run, there are no negative outcomes for the knee.

An accompanying editorial noted that research into the effect of running on those with osteoarthritis was still in its infancy. “This would help to guide clinical practice on how to support people with osteoarthritis, with regard to accessing the health benefits of running participation,” write Jean-Francois Esculier, PT, PhD, from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and Christian Barton, PhD, with the La Trobe Centre, pointing out there were a lack of evidence-based clinical recommendations for people with osteoarthritis who want to start or continue running.

It’s a question that PhD candidate Michaela Khan, MSc, is trying to answer at the University of British Columbia. “Our lab did a pilot study for my current study now, and they found that osteoarthritic cartilage took a little bit longer to recover than their healthy counterparts,” Ms. Khan said. Her research is suggesting that people with osteoarthritis not only can run, but even those with severe disease, who might be candidates for knee replacement, can run long distances.

Commenting on the analysis, Ms. Khan said the main take-home message was that healthy cartilage seems to recover after running, and that there is not an ongoing effect of ‘wear and tear.’

“That’s changing the narrative that if you keep running, it will wear away your cartilage, it’ll hurt your knees,” she said. “Now, we have a good synthesis of scientific evidence to prove maybe otherwise.”

Ms. Coburn and Dr. Culvenor report grant support from the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia, and another author reports grant support from the U.S. National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The authors, as well as Dr. Lo and Ms. Khan, report relevant financial relationships.

Adult stem cells can heal intractable perianal Crohn’s fistulae

AURORA, COLO. – Perianal Crohn’s disease with fistula is notoriously difficult to treat and can make patients’ lives miserable, but a new, minimally invasive approach involving local injection of mesenchymal stem cells is both safe and, in a significant proportion of patients, highly effective, according to a colorectal surgeon.

“It’s a really debilitating phenotype, a spectrum of phenotypes,” Amy Lightner, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Although some patients have minimal symptoms, others may require multiple setons to aid in drainage and healing, while others may require fistulotomy, endorectal advancement flap, intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure, diversion, or proctectomy.

“Why is it so difficult to treat? Well, part of it is that this is an anatomic defect, and this is why 90% of patients will come to the operating room and will see their surgeons on a frequent basis. The other part of that is that we have medical therapies to treat these fistulas but they’re really largely ineffective, because there is that anatomical defect, the hole there that needs to be closed,” Dr. Lightner said.

Up to 20% of patients may require a permanent stoma, and an additional 20% may require temporary fecal diversion.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are derived from bone marrow, fat stores, or umbilical cord tissues. Unlike embryonic stem cells, which have the ability to metamorphose into a multitude of other cell types, mesenchymal stem cells are differentiated “adult” cells.

They work by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines and recruiting immune cells to stimulate tissue repair and healing. The cells are delivered in a minimally invasive outpatient setting, and there is no risk of incontinence compared with more invasive procedures such as fistulotomy or advancement flaps.

Effective and safe

MSCs were first used in Spain in 2003 to successfully treat a young women with a complex fistula with five perianal tracts converging into a rectovaginal fistula. The investigators injected a single dose of 9 x 106 MSCs into the site, and the fistula healed within 3 months.

Since then in multiple clinical trials involving more than 400 patients, injection of MSCs has resulted in fistula closure and complete healing by 8-12 weeks in 50%-85% of patients, Dr. Lightner said.

The treatment effect is also durable, she said, pointing to data from the ADMIRE-CD study, in which 51.5% of Crohn’s disease patients with treatment-refractory complex perianal fistula were healed at 24 weeks following injection of adipose-derived stem cells, compared with 35.6% of controls. At 1 year of follow-up, respective rates of healing were 56.3% vs. 38.6%.

Dr. Lightner also cited a case report of a patient whose fistula remained healed 4 years after receiving MSCs for refractory perianal Crohn’s fistulas.

Although MSCs are derived from healthy donors, they do not bear cellular surface antigens that would instigate a destructive host immune response, and to date, there have been no reports from clinical trials of systemic infections or complications. The most frequently reported adverse events have been injection-site pain in about 12%-15% of patients, and perianal abscess in 5%-13%, with similar frequencies in treatment and control groups.

Dr. Lightner and colleagues are currently exploring additional indications for stem cell therapy with MSCs, including other complex fistula phenotypes, intestinal Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

Other approaches

In a separate presentation, James D. Lewis, MD, MSCE, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia talked about what would be needed to achieve a “medical moonshot” with the goal of curing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and touched on hematopoietic stem cell transplants as a potential option for patients with chronic, severe, and intractable disease.

One of his patients was a woman in her 60s who was diagnosed with stricturing and penetrating Crohn’s disease in her 30s, with the disease involving the ileum and entire colon. She had previously undergone three small bowel resections and a partial colon resection, and had never experienced remission despite taking steroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, four anti-TNF drugs, ustekinumab (Stelara), and vedolizumab (Entyvio).

Following an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, she had a Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) of 0. Her course was complicated by demand ischemia and acute kidney injury.

An IBD specialist who was not involved in either study commented in an interview that both MSCs and stem cell transplants show promise for treatment-refractory IBD,

“Both approaches are very promising, but stem cell transplants for IBD haven’t been formally studied yet so the data aren’t as strong, but there is promise for the future,” said Berkeley N. Limketkai, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The challenges, however, are also the morbidity associated with actually undergoing such procedures,” he continued. Short- and long-term morbidities associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplants may include mucositis; hemorrhagic cystitis; prolonged, severe pancytopenia; infection; graft-versus-host disease; graft failure; pulmonary complications, veno-occlusive disease of the liver; and thrombotic microangiopathy.

Dr. Limketkai said that over time as the protocols for stem cell transplants in IBD improve, the benefits for select patients may more clearly outweigh the risks.

Dr. Lightner’s work is supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgery. She disclosed consulting fees from Boomerang Medical, Mesoblast Limited, Ossium Health, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA. Dr. Lewis’ work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and from AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, and Nestlé Health Science. He has also served as a consultant to and data safety monitoring board member for several entities. Dr. Limketkai disclosed consulting for Azora Therapeutics.

AURORA, COLO. – Perianal Crohn’s disease with fistula is notoriously difficult to treat and can make patients’ lives miserable, but a new, minimally invasive approach involving local injection of mesenchymal stem cells is both safe and, in a significant proportion of patients, highly effective, according to a colorectal surgeon.

“It’s a really debilitating phenotype, a spectrum of phenotypes,” Amy Lightner, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Although some patients have minimal symptoms, others may require multiple setons to aid in drainage and healing, while others may require fistulotomy, endorectal advancement flap, intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure, diversion, or proctectomy.

“Why is it so difficult to treat? Well, part of it is that this is an anatomic defect, and this is why 90% of patients will come to the operating room and will see their surgeons on a frequent basis. The other part of that is that we have medical therapies to treat these fistulas but they’re really largely ineffective, because there is that anatomical defect, the hole there that needs to be closed,” Dr. Lightner said.

Up to 20% of patients may require a permanent stoma, and an additional 20% may require temporary fecal diversion.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are derived from bone marrow, fat stores, or umbilical cord tissues. Unlike embryonic stem cells, which have the ability to metamorphose into a multitude of other cell types, mesenchymal stem cells are differentiated “adult” cells.

They work by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines and recruiting immune cells to stimulate tissue repair and healing. The cells are delivered in a minimally invasive outpatient setting, and there is no risk of incontinence compared with more invasive procedures such as fistulotomy or advancement flaps.

Effective and safe

MSCs were first used in Spain in 2003 to successfully treat a young women with a complex fistula with five perianal tracts converging into a rectovaginal fistula. The investigators injected a single dose of 9 x 106 MSCs into the site, and the fistula healed within 3 months.

Since then in multiple clinical trials involving more than 400 patients, injection of MSCs has resulted in fistula closure and complete healing by 8-12 weeks in 50%-85% of patients, Dr. Lightner said.

The treatment effect is also durable, she said, pointing to data from the ADMIRE-CD study, in which 51.5% of Crohn’s disease patients with treatment-refractory complex perianal fistula were healed at 24 weeks following injection of adipose-derived stem cells, compared with 35.6% of controls. At 1 year of follow-up, respective rates of healing were 56.3% vs. 38.6%.

Dr. Lightner also cited a case report of a patient whose fistula remained healed 4 years after receiving MSCs for refractory perianal Crohn’s fistulas.

Although MSCs are derived from healthy donors, they do not bear cellular surface antigens that would instigate a destructive host immune response, and to date, there have been no reports from clinical trials of systemic infections or complications. The most frequently reported adverse events have been injection-site pain in about 12%-15% of patients, and perianal abscess in 5%-13%, with similar frequencies in treatment and control groups.

Dr. Lightner and colleagues are currently exploring additional indications for stem cell therapy with MSCs, including other complex fistula phenotypes, intestinal Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

Other approaches

In a separate presentation, James D. Lewis, MD, MSCE, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia talked about what would be needed to achieve a “medical moonshot” with the goal of curing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and touched on hematopoietic stem cell transplants as a potential option for patients with chronic, severe, and intractable disease.

One of his patients was a woman in her 60s who was diagnosed with stricturing and penetrating Crohn’s disease in her 30s, with the disease involving the ileum and entire colon. She had previously undergone three small bowel resections and a partial colon resection, and had never experienced remission despite taking steroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, four anti-TNF drugs, ustekinumab (Stelara), and vedolizumab (Entyvio).

Following an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, she had a Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) of 0. Her course was complicated by demand ischemia and acute kidney injury.

An IBD specialist who was not involved in either study commented in an interview that both MSCs and stem cell transplants show promise for treatment-refractory IBD,

“Both approaches are very promising, but stem cell transplants for IBD haven’t been formally studied yet so the data aren’t as strong, but there is promise for the future,” said Berkeley N. Limketkai, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The challenges, however, are also the morbidity associated with actually undergoing such procedures,” he continued. Short- and long-term morbidities associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplants may include mucositis; hemorrhagic cystitis; prolonged, severe pancytopenia; infection; graft-versus-host disease; graft failure; pulmonary complications, veno-occlusive disease of the liver; and thrombotic microangiopathy.

Dr. Limketkai said that over time as the protocols for stem cell transplants in IBD improve, the benefits for select patients may more clearly outweigh the risks.

Dr. Lightner’s work is supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgery. She disclosed consulting fees from Boomerang Medical, Mesoblast Limited, Ossium Health, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA. Dr. Lewis’ work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and from AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, and Nestlé Health Science. He has also served as a consultant to and data safety monitoring board member for several entities. Dr. Limketkai disclosed consulting for Azora Therapeutics.

AURORA, COLO. – Perianal Crohn’s disease with fistula is notoriously difficult to treat and can make patients’ lives miserable, but a new, minimally invasive approach involving local injection of mesenchymal stem cells is both safe and, in a significant proportion of patients, highly effective, according to a colorectal surgeon.

“It’s a really debilitating phenotype, a spectrum of phenotypes,” Amy Lightner, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said at the annual Crohn’s & Colitis Congress®, a partnership of the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation and the American Gastroenterological Association.

Although some patients have minimal symptoms, others may require multiple setons to aid in drainage and healing, while others may require fistulotomy, endorectal advancement flap, intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) procedure, diversion, or proctectomy.

“Why is it so difficult to treat? Well, part of it is that this is an anatomic defect, and this is why 90% of patients will come to the operating room and will see their surgeons on a frequent basis. The other part of that is that we have medical therapies to treat these fistulas but they’re really largely ineffective, because there is that anatomical defect, the hole there that needs to be closed,” Dr. Lightner said.

Up to 20% of patients may require a permanent stoma, and an additional 20% may require temporary fecal diversion.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) are derived from bone marrow, fat stores, or umbilical cord tissues. Unlike embryonic stem cells, which have the ability to metamorphose into a multitude of other cell types, mesenchymal stem cells are differentiated “adult” cells.

They work by secreting anti-inflammatory cytokines and recruiting immune cells to stimulate tissue repair and healing. The cells are delivered in a minimally invasive outpatient setting, and there is no risk of incontinence compared with more invasive procedures such as fistulotomy or advancement flaps.

Effective and safe

MSCs were first used in Spain in 2003 to successfully treat a young women with a complex fistula with five perianal tracts converging into a rectovaginal fistula. The investigators injected a single dose of 9 x 106 MSCs into the site, and the fistula healed within 3 months.

Since then in multiple clinical trials involving more than 400 patients, injection of MSCs has resulted in fistula closure and complete healing by 8-12 weeks in 50%-85% of patients, Dr. Lightner said.

The treatment effect is also durable, she said, pointing to data from the ADMIRE-CD study, in which 51.5% of Crohn’s disease patients with treatment-refractory complex perianal fistula were healed at 24 weeks following injection of adipose-derived stem cells, compared with 35.6% of controls. At 1 year of follow-up, respective rates of healing were 56.3% vs. 38.6%.

Dr. Lightner also cited a case report of a patient whose fistula remained healed 4 years after receiving MSCs for refractory perianal Crohn’s fistulas.

Although MSCs are derived from healthy donors, they do not bear cellular surface antigens that would instigate a destructive host immune response, and to date, there have been no reports from clinical trials of systemic infections or complications. The most frequently reported adverse events have been injection-site pain in about 12%-15% of patients, and perianal abscess in 5%-13%, with similar frequencies in treatment and control groups.

Dr. Lightner and colleagues are currently exploring additional indications for stem cell therapy with MSCs, including other complex fistula phenotypes, intestinal Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

Other approaches

In a separate presentation, James D. Lewis, MD, MSCE, of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia talked about what would be needed to achieve a “medical moonshot” with the goal of curing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and touched on hematopoietic stem cell transplants as a potential option for patients with chronic, severe, and intractable disease.

One of his patients was a woman in her 60s who was diagnosed with stricturing and penetrating Crohn’s disease in her 30s, with the disease involving the ileum and entire colon. She had previously undergone three small bowel resections and a partial colon resection, and had never experienced remission despite taking steroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, four anti-TNF drugs, ustekinumab (Stelara), and vedolizumab (Entyvio).

Following an autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, she had a Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) of 0. Her course was complicated by demand ischemia and acute kidney injury.

An IBD specialist who was not involved in either study commented in an interview that both MSCs and stem cell transplants show promise for treatment-refractory IBD,

“Both approaches are very promising, but stem cell transplants for IBD haven’t been formally studied yet so the data aren’t as strong, but there is promise for the future,” said Berkeley N. Limketkai, MD, PhD, from the University of California, Los Angeles.

“The challenges, however, are also the morbidity associated with actually undergoing such procedures,” he continued. Short- and long-term morbidities associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplants may include mucositis; hemorrhagic cystitis; prolonged, severe pancytopenia; infection; graft-versus-host disease; graft failure; pulmonary complications, veno-occlusive disease of the liver; and thrombotic microangiopathy.

Dr. Limketkai said that over time as the protocols for stem cell transplants in IBD improve, the benefits for select patients may more clearly outweigh the risks.

Dr. Lightner’s work is supported by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgery. She disclosed consulting fees from Boomerang Medical, Mesoblast Limited, Ossium Health, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA. Dr. Lewis’ work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, and from AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, and Nestlé Health Science. He has also served as a consultant to and data safety monitoring board member for several entities. Dr. Limketkai disclosed consulting for Azora Therapeutics.

AT CROHN’S & COLITIS CONGRESS

Massive rise in drug overdose deaths driven by opioids

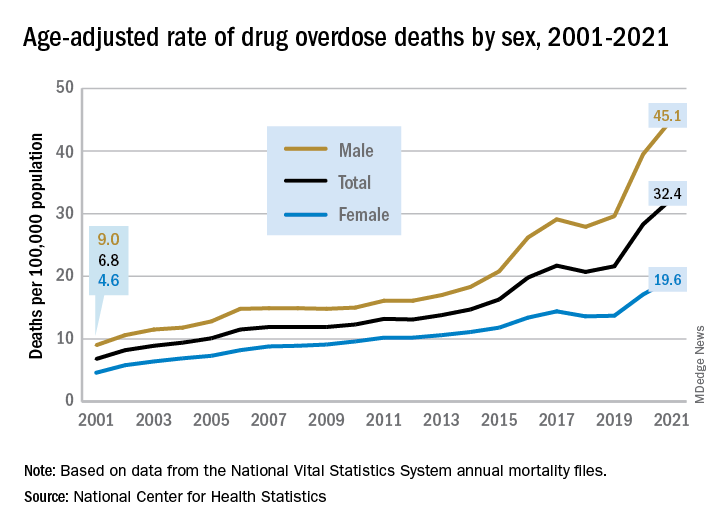

The 376% represents the change in age-adjusted overdose deaths per 100,000 population, which went from 6.9 in 2001 to 32.4 in 2021, as the total number of deaths rose from 19,394 to 106,699 (450%) over that time period, the NCHS said in a recent data brief. That total made 2021 the first year ever with more than 100,000 overdose deaths.

Since the age-adjusted rate stood at 21.6 per 100,000 in 2019, that means 42% of the total increase over 20 years actually occurred in 2020 and 2021. The number of deaths increased by about 36,000 over those 2 years, accounting for 41% of the total annual increase from 2001 to 2021, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System mortality files.

The overdose death rate was significantly higher for males than females for all of the years from 2001 to 2021, with males seeing an increase from 9.0 to 45.1 per 100,000 and females going from 4.6 to 19.6 deaths per 100,000. In the single year from 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted rate was up by 14% for males and 15% for females, the mortality-file data show.

Analysis by age showed an even larger effect in some groups from 2020 to 2021. Drug overdose deaths jumped 28% among adults aged 65 years and older, more than any other group, and by 21% in those aged 55-64 years, according to the NCHS.

The only age group for which deaths didn’t increase significantly from 2020 to 2021 was 15- to 24-year-olds, whose rate rose by just 3%. The age group with the highest rate in both 2020 and 2021, however, was the 35- to 44-year-olds: 53.9 and 62.0 overdose deaths per 100,000, respectively, for an increase of 15%, the NCHS said in the report.

The drugs now involved in overdose deaths are most often opioids, a change from 2001. That year, opioids were involved in 49% of all overdose deaths, but by 2021 that share had increased to 75%. The trend for opioid-related deaths almost matches that of overall deaths over the 20-year span, and the significantly increasing trend that began for all overdose deaths in 2013 closely follows that of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol, the report shows.

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate also show similar increases. The cocaine-related death rate rose 22% from 2020 to 2021 and is up by 421% since 2012, while the corresponding increases for psychostimulant deaths were 33% and 2,400%, the NCHS said.

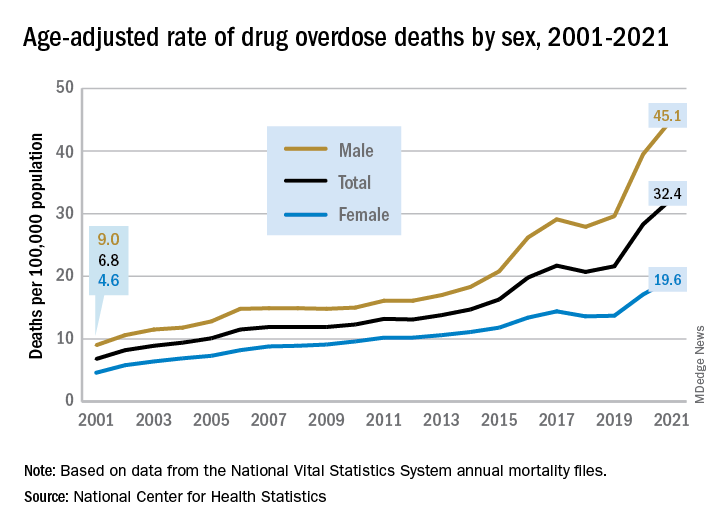

The 376% represents the change in age-adjusted overdose deaths per 100,000 population, which went from 6.9 in 2001 to 32.4 in 2021, as the total number of deaths rose from 19,394 to 106,699 (450%) over that time period, the NCHS said in a recent data brief. That total made 2021 the first year ever with more than 100,000 overdose deaths.

Since the age-adjusted rate stood at 21.6 per 100,000 in 2019, that means 42% of the total increase over 20 years actually occurred in 2020 and 2021. The number of deaths increased by about 36,000 over those 2 years, accounting for 41% of the total annual increase from 2001 to 2021, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System mortality files.

The overdose death rate was significantly higher for males than females for all of the years from 2001 to 2021, with males seeing an increase from 9.0 to 45.1 per 100,000 and females going from 4.6 to 19.6 deaths per 100,000. In the single year from 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted rate was up by 14% for males and 15% for females, the mortality-file data show.

Analysis by age showed an even larger effect in some groups from 2020 to 2021. Drug overdose deaths jumped 28% among adults aged 65 years and older, more than any other group, and by 21% in those aged 55-64 years, according to the NCHS.

The only age group for which deaths didn’t increase significantly from 2020 to 2021 was 15- to 24-year-olds, whose rate rose by just 3%. The age group with the highest rate in both 2020 and 2021, however, was the 35- to 44-year-olds: 53.9 and 62.0 overdose deaths per 100,000, respectively, for an increase of 15%, the NCHS said in the report.

The drugs now involved in overdose deaths are most often opioids, a change from 2001. That year, opioids were involved in 49% of all overdose deaths, but by 2021 that share had increased to 75%. The trend for opioid-related deaths almost matches that of overall deaths over the 20-year span, and the significantly increasing trend that began for all overdose deaths in 2013 closely follows that of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol, the report shows.

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate also show similar increases. The cocaine-related death rate rose 22% from 2020 to 2021 and is up by 421% since 2012, while the corresponding increases for psychostimulant deaths were 33% and 2,400%, the NCHS said.

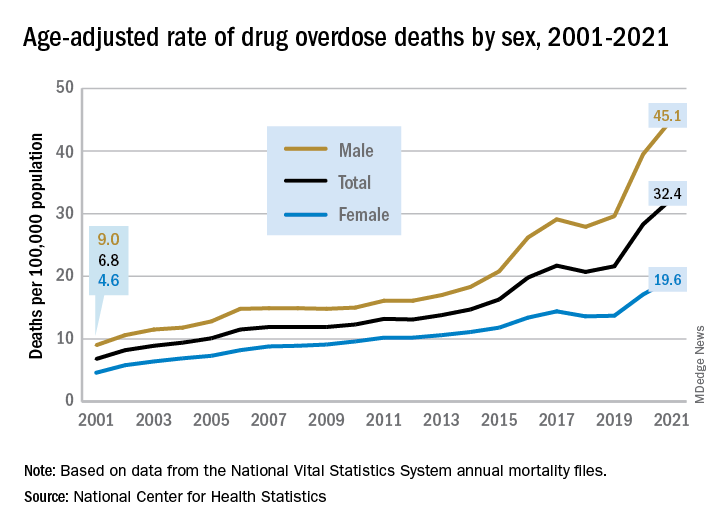

The 376% represents the change in age-adjusted overdose deaths per 100,000 population, which went from 6.9 in 2001 to 32.4 in 2021, as the total number of deaths rose from 19,394 to 106,699 (450%) over that time period, the NCHS said in a recent data brief. That total made 2021 the first year ever with more than 100,000 overdose deaths.

Since the age-adjusted rate stood at 21.6 per 100,000 in 2019, that means 42% of the total increase over 20 years actually occurred in 2020 and 2021. The number of deaths increased by about 36,000 over those 2 years, accounting for 41% of the total annual increase from 2001 to 2021, based on data from the National Vital Statistics System mortality files.

The overdose death rate was significantly higher for males than females for all of the years from 2001 to 2021, with males seeing an increase from 9.0 to 45.1 per 100,000 and females going from 4.6 to 19.6 deaths per 100,000. In the single year from 2020 to 2021, the age-adjusted rate was up by 14% for males and 15% for females, the mortality-file data show.

Analysis by age showed an even larger effect in some groups from 2020 to 2021. Drug overdose deaths jumped 28% among adults aged 65 years and older, more than any other group, and by 21% in those aged 55-64 years, according to the NCHS.

The only age group for which deaths didn’t increase significantly from 2020 to 2021 was 15- to 24-year-olds, whose rate rose by just 3%. The age group with the highest rate in both 2020 and 2021, however, was the 35- to 44-year-olds: 53.9 and 62.0 overdose deaths per 100,000, respectively, for an increase of 15%, the NCHS said in the report.

The drugs now involved in overdose deaths are most often opioids, a change from 2001. That year, opioids were involved in 49% of all overdose deaths, but by 2021 that share had increased to 75%. The trend for opioid-related deaths almost matches that of overall deaths over the 20-year span, and the significantly increasing trend that began for all overdose deaths in 2013 closely follows that of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl and tramadol, the report shows.

Overdose deaths involving cocaine and psychostimulants such as methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate also show similar increases. The cocaine-related death rate rose 22% from 2020 to 2021 and is up by 421% since 2012, while the corresponding increases for psychostimulant deaths were 33% and 2,400%, the NCHS said.

Lipid signature may flag schizophrenia

Although such a test remains a long way off, investigators said, the identification of the unique lipid signature is a critical first step. However, one expert noted that the lipid signature not accurately differentiating patients with schizophrenia from those with bipolar disorder (BD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) limits the findings’ applicability.

The profile includes 77 lipids identified from a large analysis of many different classes of lipid species. Lipids such as cholesterol and triglycerides made up only a small fraction of the classes assessed.

The investigators noted that some of the lipids in the profile associated with schizophrenia are involved in determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging, which could be important to synaptic function.

“These 77 lipids jointly constitute a lipidomic profile that discriminated between individuals with schizophrenia and individuals without a mental health diagnosis with very high accuracy,” investigator Eva C. Schulte, MD, PhD, of the Institute of Psychiatric Phenomics and Genomics (IPPG) and the department of psychiatry and psychotherapy at University Hospital of Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Munich, told this news organization.

“Of note, we did not see large profile differences between patients with a first psychotic episode who had only been treated for a few days and individuals on long-term antipsychotic therapy,” Dr. Schulte said.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Detailed analysis

Lipid profiles in patients with psychiatric diagnoses have been reported previously, but those studies were small and did not identify a reliable signature independent of demographic and environmental factors.

For the current study, researchers analyzed blood plasma lipid levels from 980 individuals with severe psychiatric illness and 572 people without mental illness from three cohorts in China, Germany, Austria, and Russia.

The study sample included patients with schizophrenia (n = 478), BD (n = 184), and MDD (n = 256), as well as 104 patients with a first psychotic episode who had no long-term psychopharmacology use.

Results showed 77 lipids in 14 classes were significantly altered between participants with schizophrenia and the healthy control in all three cohorts.

The most prominent alterations at the lipid class level included increases in ceramide, triacylglyceride, and phosphatidylcholine and decreases in acylcarnitine and phosphatidylcholine plasmalogen (P < .05 for each cohort).

Schizophrenia-associated lipid differences were similar between patients with high and low symptom severity (P < .001), suggesting that the lipid alterations might represent a trait of the psychiatric disorder.

No medication effect

Most patients in the study received long-term antipsychotic medication, which has been shown previously to affect some plasma lipid compounds.

So, to assess a possible effect of medication, the investigators evaluated 13 patients with schizophrenia who were not medicated for at least 6 months prior to blood sample collection and the cohort of patients with a first psychotic episode who had been medicated for less than 1 week.

Comparison of the lipid intensity differences between the healthy controls group and either participants receiving medication or those who were not medicated revealed highly correlated alterations in both patient groups (P < .001).

“Taken together, these results indicate that the identified schizophrenia-associated alterations cannot be attributed to medication effects,” the investigators wrote.

Lipidome alterations in BPD and MDD, assessed in 184 and 256 individuals, respectively, were similar to those of schizophrenia but not identical.

Researchers isolated 97 lipids altered in the MDD cohorts and 47 in the BPD cohorts – with 30 and 28, respectively, overlapping with the schizophrenia-associated features and seven of the lipids found among all three disorders.

Although this was significantly more than expected by chance (P < .001), it was not strong enough to demonstrate a clear association, the investigators wrote.

“The profiles were very successful at differentiating individuals with severe mental health conditions from individuals without a diagnosed mental health condition, but much less so at differentiating between the different diagnostic entities,” coinvestigator Thomas G. Schulze, MD, director of IPPG, said in an interview.

“An important caveat, however, is that the available sample sizes for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder were smaller than those for schizophrenia, which makes a direct comparison between these difficult,” added Dr. Schulze, clinical professor in psychiatry and behavioral sciences at State University of New York, Syracuse.

More work remains

Although the study is thought to be the largest to date to examine lipid profiles associated with serious psychiatric illness, much work remains, Dr. Schulze noted.

“At this time, based on these first results, no clinical diagnostic test can be derived from these results,” he said.

He added that the development of reliable biomarkers based on lipidomic profiles would require large prospective randomized trials, complemented by observational studies assessing full lipidomic profiles across the lifespan.

Researchers also need to better understand the exact mechanism by which lipid alterations are associated with schizophrenia and other illnesses.

Physiologically, the investigated lipids have many additional functions, such as determining cell membrane structure and fluidity or cell-to-cell messaging.

Dr. Schulte noted that several lipid species may be involved in determining mechanisms important to synaptic function, such as cell membrane fluidity and vesicle release.

“As is commonly known, alterations in synaptic function underly many severe psychiatric disorders,” she said. “Changes in lipid species could theoretically be related to these synaptic alterations.”

A better marker needed

In a comment, Stephen Strakowski, MD, professor and vice chair of research in the department of psychiatry, Indiana University, Indianapolis and Evansville, noted that while the findings are interesting, they don’t really offer the kind of information clinicians who treat patients with serious mental illness need most.