User login

VEXAS syndrome: More common, variable, and severe than expected

A recently discovered inflammatory disease known as VEXAS syndrome is more common, variable, and dangerous than previously understood, according to results of a retrospective observational study of a large health care system database. The findings, published in JAMA, found that it struck 1 in 4,269 men over the age of 50 in a largely White population and caused a wide variety of symptoms.

“The disease is quite severe,” study lead author David Beck, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. Patients with the condition “have a variety of clinical symptoms affecting different parts of the body and are being managed by different medical specialties.”

Dr. Beck and colleagues first described VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome in 2020. They linked it to mutations in the UBA1 (ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1) gene. The enzyme initiates a process that identifies misfolded proteins as targets for degradation.

“VEXAS syndrome is characterized by anemia and inflammation in the skin, lungs, cartilage, and joints,” Dr. Beck said. “These symptoms are frequently mistaken for other rheumatic or hematologic diseases. However, this syndrome has a different cause, is treated differently, requires additional monitoring, and can be far more severe.”

According to him, hundreds of people have been diagnosed with the disease in the short time since it was defined. The disease is believed to be fatal in some cases. A previous report found that the median survival was 9 years among patients with a certain variant; that was significantly less than patients with two other variants.

For the new study, researchers searched for UBA1 variants in genetic data from 163,096 subjects (mean age, 52.8 years; 94% White, 61% women) who took part in the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative. The 1996-2022 data comes from patients at 10 Pennsylvania hospitals.

Eleven people (9 males, 2 females) had likely UBA1 variants, and all had anemia. The cases accounted for 1 in 13,591 unrelated people (95% confidence interval, 1:7,775-1:23,758), 1 in 4,269 men older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:2,319-1:7,859), and 1 in 26,238 women older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:7,196-1:147,669).

Other common findings included macrocytosis (91%), skin problems (73%), and pulmonary disease (91%). Ten patients (91%) required transfusions.

Five of the 11 subjects didn’t meet the previously defined criteria for VEXAS syndrome. None had been diagnosed with the condition, which is not surprising considering that it hadn’t been discovered and described until recently.

Just over half of the patients – 55% – had a clinical diagnosis that was previously linked to VEXAS syndrome. “This means that slightly less than half of the patients with VEXAS syndrome had no clear associated clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said. “The lack of associated clinical diagnoses may be due to the variety of nonspecific clinical characteristics that span different subspecialities in VEXAS syndrome. VEXAS syndrome represents an example of a multisystem disease where patients and their symptoms may get lost in the shuffle.”

In the future, “professionals should look out for patients with unexplained inflammation – and some combination of hematologic, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and dermatologic clinical manifestations – that either don’t carry a clinical diagnosis or don’t respond to first-line therapies,” Dr. Beck said. “These patients will also frequently be anemic, have low platelet counts, elevated markers of inflammation in the blood, and be dependent on corticosteroids.”

Diagnosis can be made via genetic testing, but the study authors note that it “is not routinely offered on standard workup for myeloid neoplasms or immune dysregulation diagnostic panels.”

As for treatment, Dr. Beck said the disease “can be partially controlled by multiple different anticytokine therapies or biologics. However, in most cases, patients still need additional steroids and/or disease-modifying antirheumatic agents [DMARDs]. In addition, bone marrow transplantation has shown signs of being a highly effective therapy.”

The study authors say more research is needed to understand the disease’s prevalence in more diverse populations.

In an interview, Matthew J. Koster, MD, a rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who’s studied the disease but didn’t take part in this research project, said the findings are valid and “highly important.

“The findings of this study highlight what many academic and quaternary referral centers were wondering: Is VEXAS really more common than we think, with patients hiding in plain sight? The answer is yes,” he said. “Currently, there are less than 400 cases reported in the literature of VEXAS, but large centers are diagnosing this condition with some frequency. For example, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we diagnose on average one new patient with VEXAS every 7-14 days and have diagnosed 60 in the past 18 months. A national collaborative group in France has diagnosed approximately 250 patients over that same time frame when pooling patients nationwide.”

The prevalence is high enough, he said, that “clinicians should consider that some of the patients with diseases that are not responding to treatment may in fact have VEXAS rather than ‘refractory’ relapsing polychondritis or ‘recalcitrant’ rheumatoid arthritis, etc.”

The National Institute of Health funded the study. Dr. Beck, the other authors, and Dr. Koster report no disclosures.

A recently discovered inflammatory disease known as VEXAS syndrome is more common, variable, and dangerous than previously understood, according to results of a retrospective observational study of a large health care system database. The findings, published in JAMA, found that it struck 1 in 4,269 men over the age of 50 in a largely White population and caused a wide variety of symptoms.

“The disease is quite severe,” study lead author David Beck, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. Patients with the condition “have a variety of clinical symptoms affecting different parts of the body and are being managed by different medical specialties.”

Dr. Beck and colleagues first described VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome in 2020. They linked it to mutations in the UBA1 (ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1) gene. The enzyme initiates a process that identifies misfolded proteins as targets for degradation.

“VEXAS syndrome is characterized by anemia and inflammation in the skin, lungs, cartilage, and joints,” Dr. Beck said. “These symptoms are frequently mistaken for other rheumatic or hematologic diseases. However, this syndrome has a different cause, is treated differently, requires additional monitoring, and can be far more severe.”

According to him, hundreds of people have been diagnosed with the disease in the short time since it was defined. The disease is believed to be fatal in some cases. A previous report found that the median survival was 9 years among patients with a certain variant; that was significantly less than patients with two other variants.

For the new study, researchers searched for UBA1 variants in genetic data from 163,096 subjects (mean age, 52.8 years; 94% White, 61% women) who took part in the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative. The 1996-2022 data comes from patients at 10 Pennsylvania hospitals.

Eleven people (9 males, 2 females) had likely UBA1 variants, and all had anemia. The cases accounted for 1 in 13,591 unrelated people (95% confidence interval, 1:7,775-1:23,758), 1 in 4,269 men older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:2,319-1:7,859), and 1 in 26,238 women older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:7,196-1:147,669).

Other common findings included macrocytosis (91%), skin problems (73%), and pulmonary disease (91%). Ten patients (91%) required transfusions.

Five of the 11 subjects didn’t meet the previously defined criteria for VEXAS syndrome. None had been diagnosed with the condition, which is not surprising considering that it hadn’t been discovered and described until recently.

Just over half of the patients – 55% – had a clinical diagnosis that was previously linked to VEXAS syndrome. “This means that slightly less than half of the patients with VEXAS syndrome had no clear associated clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said. “The lack of associated clinical diagnoses may be due to the variety of nonspecific clinical characteristics that span different subspecialities in VEXAS syndrome. VEXAS syndrome represents an example of a multisystem disease where patients and their symptoms may get lost in the shuffle.”

In the future, “professionals should look out for patients with unexplained inflammation – and some combination of hematologic, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and dermatologic clinical manifestations – that either don’t carry a clinical diagnosis or don’t respond to first-line therapies,” Dr. Beck said. “These patients will also frequently be anemic, have low platelet counts, elevated markers of inflammation in the blood, and be dependent on corticosteroids.”

Diagnosis can be made via genetic testing, but the study authors note that it “is not routinely offered on standard workup for myeloid neoplasms or immune dysregulation diagnostic panels.”

As for treatment, Dr. Beck said the disease “can be partially controlled by multiple different anticytokine therapies or biologics. However, in most cases, patients still need additional steroids and/or disease-modifying antirheumatic agents [DMARDs]. In addition, bone marrow transplantation has shown signs of being a highly effective therapy.”

The study authors say more research is needed to understand the disease’s prevalence in more diverse populations.

In an interview, Matthew J. Koster, MD, a rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who’s studied the disease but didn’t take part in this research project, said the findings are valid and “highly important.

“The findings of this study highlight what many academic and quaternary referral centers were wondering: Is VEXAS really more common than we think, with patients hiding in plain sight? The answer is yes,” he said. “Currently, there are less than 400 cases reported in the literature of VEXAS, but large centers are diagnosing this condition with some frequency. For example, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we diagnose on average one new patient with VEXAS every 7-14 days and have diagnosed 60 in the past 18 months. A national collaborative group in France has diagnosed approximately 250 patients over that same time frame when pooling patients nationwide.”

The prevalence is high enough, he said, that “clinicians should consider that some of the patients with diseases that are not responding to treatment may in fact have VEXAS rather than ‘refractory’ relapsing polychondritis or ‘recalcitrant’ rheumatoid arthritis, etc.”

The National Institute of Health funded the study. Dr. Beck, the other authors, and Dr. Koster report no disclosures.

A recently discovered inflammatory disease known as VEXAS syndrome is more common, variable, and dangerous than previously understood, according to results of a retrospective observational study of a large health care system database. The findings, published in JAMA, found that it struck 1 in 4,269 men over the age of 50 in a largely White population and caused a wide variety of symptoms.

“The disease is quite severe,” study lead author David Beck, MD, PhD, of the department of medicine at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. Patients with the condition “have a variety of clinical symptoms affecting different parts of the body and are being managed by different medical specialties.”

Dr. Beck and colleagues first described VEXAS (vacuoles, E1-ubiquitin-activating enzyme, X-linked, autoinflammatory, somatic) syndrome in 2020. They linked it to mutations in the UBA1 (ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme 1) gene. The enzyme initiates a process that identifies misfolded proteins as targets for degradation.

“VEXAS syndrome is characterized by anemia and inflammation in the skin, lungs, cartilage, and joints,” Dr. Beck said. “These symptoms are frequently mistaken for other rheumatic or hematologic diseases. However, this syndrome has a different cause, is treated differently, requires additional monitoring, and can be far more severe.”

According to him, hundreds of people have been diagnosed with the disease in the short time since it was defined. The disease is believed to be fatal in some cases. A previous report found that the median survival was 9 years among patients with a certain variant; that was significantly less than patients with two other variants.

For the new study, researchers searched for UBA1 variants in genetic data from 163,096 subjects (mean age, 52.8 years; 94% White, 61% women) who took part in the Geisinger MyCode Community Health Initiative. The 1996-2022 data comes from patients at 10 Pennsylvania hospitals.

Eleven people (9 males, 2 females) had likely UBA1 variants, and all had anemia. The cases accounted for 1 in 13,591 unrelated people (95% confidence interval, 1:7,775-1:23,758), 1 in 4,269 men older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:2,319-1:7,859), and 1 in 26,238 women older than 50 years (95% CI, 1:7,196-1:147,669).

Other common findings included macrocytosis (91%), skin problems (73%), and pulmonary disease (91%). Ten patients (91%) required transfusions.

Five of the 11 subjects didn’t meet the previously defined criteria for VEXAS syndrome. None had been diagnosed with the condition, which is not surprising considering that it hadn’t been discovered and described until recently.

Just over half of the patients – 55% – had a clinical diagnosis that was previously linked to VEXAS syndrome. “This means that slightly less than half of the patients with VEXAS syndrome had no clear associated clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Beck said. “The lack of associated clinical diagnoses may be due to the variety of nonspecific clinical characteristics that span different subspecialities in VEXAS syndrome. VEXAS syndrome represents an example of a multisystem disease where patients and their symptoms may get lost in the shuffle.”

In the future, “professionals should look out for patients with unexplained inflammation – and some combination of hematologic, rheumatologic, pulmonary, and dermatologic clinical manifestations – that either don’t carry a clinical diagnosis or don’t respond to first-line therapies,” Dr. Beck said. “These patients will also frequently be anemic, have low platelet counts, elevated markers of inflammation in the blood, and be dependent on corticosteroids.”

Diagnosis can be made via genetic testing, but the study authors note that it “is not routinely offered on standard workup for myeloid neoplasms or immune dysregulation diagnostic panels.”

As for treatment, Dr. Beck said the disease “can be partially controlled by multiple different anticytokine therapies or biologics. However, in most cases, patients still need additional steroids and/or disease-modifying antirheumatic agents [DMARDs]. In addition, bone marrow transplantation has shown signs of being a highly effective therapy.”

The study authors say more research is needed to understand the disease’s prevalence in more diverse populations.

In an interview, Matthew J. Koster, MD, a rheumatologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., who’s studied the disease but didn’t take part in this research project, said the findings are valid and “highly important.

“The findings of this study highlight what many academic and quaternary referral centers were wondering: Is VEXAS really more common than we think, with patients hiding in plain sight? The answer is yes,” he said. “Currently, there are less than 400 cases reported in the literature of VEXAS, but large centers are diagnosing this condition with some frequency. For example, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we diagnose on average one new patient with VEXAS every 7-14 days and have diagnosed 60 in the past 18 months. A national collaborative group in France has diagnosed approximately 250 patients over that same time frame when pooling patients nationwide.”

The prevalence is high enough, he said, that “clinicians should consider that some of the patients with diseases that are not responding to treatment may in fact have VEXAS rather than ‘refractory’ relapsing polychondritis or ‘recalcitrant’ rheumatoid arthritis, etc.”

The National Institute of Health funded the study. Dr. Beck, the other authors, and Dr. Koster report no disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Artificial intelligence applications in colonoscopy

Considerable advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) methodologies have led to the emergence of promising tools in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Computer vision is an application of AI/ML that has been successfully applied for the computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) of colon polyps and numerous other conditions encountered during GI endoscopy. Outside of computer vision, a wide variety of other AI applications have been applied to gastroenterology, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) to optimize clinical documentation and endoscopy quality reporting to ML techniques that predict disease severity/treatment response and augment clinical decision-making.

In the United States, colonoscopy is the standard for colon cancer screening and prevention; however, precancerous polyps can be missed for various reasons, ranging from subtle surface appearance of the polyp or location behind a colonic fold to operator-dependent reasons such as inadequate mucosal inspection. Though clinical practice guidelines have set adenoma detection rate (ADR) thresholds at 20% for women and 30% for men, studies have shown a 4- to 10-fold variation in ADR among physicians in clinical practice settings,1 with an estimated adenoma miss rate (AMR) of 25% and a false-negative colonoscopy rate of 12%.2 Variability in adenoma detection affects the risk of interval colorectal cancer post colonoscopy.3,4

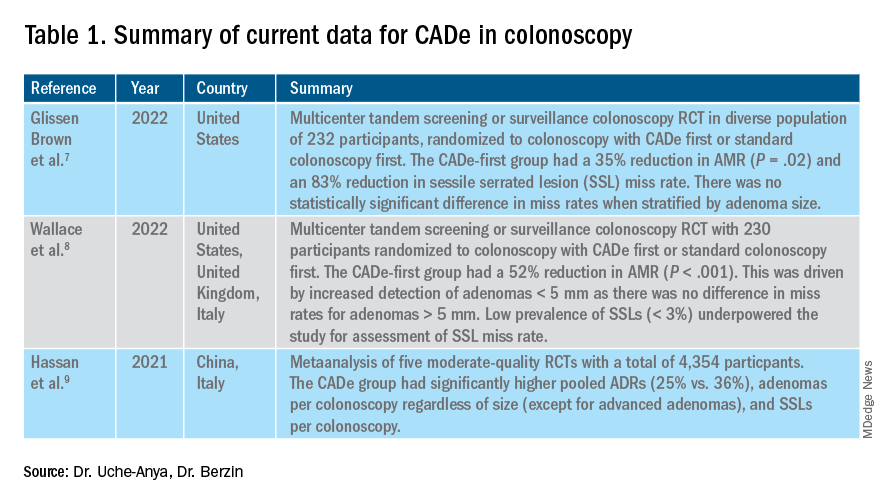

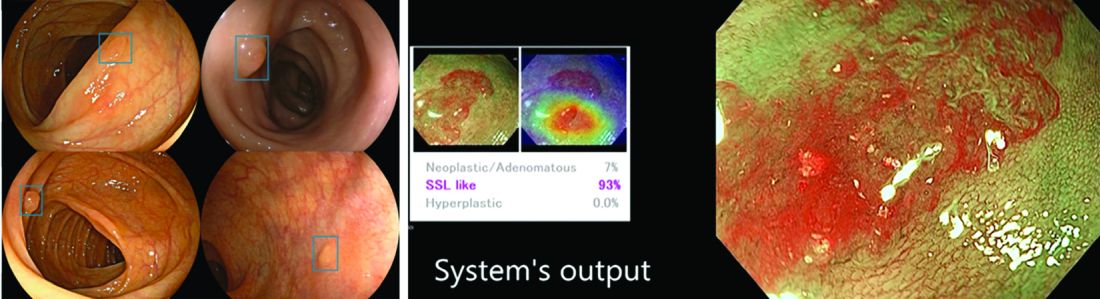

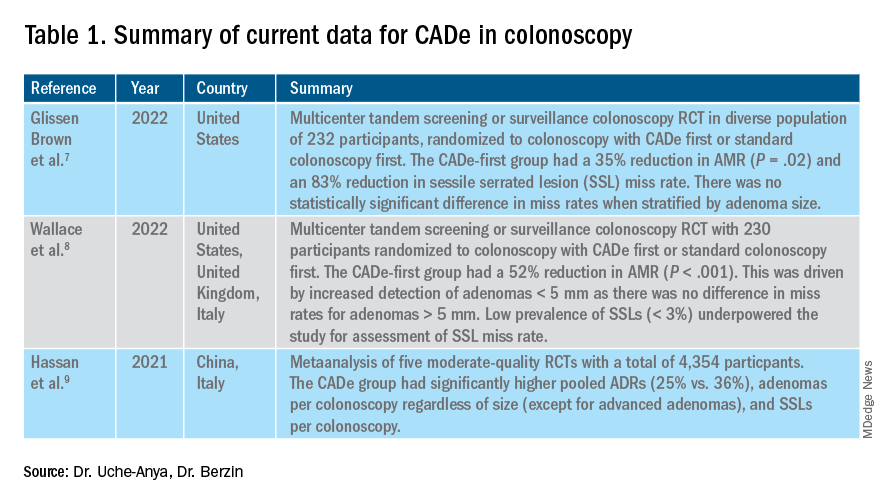

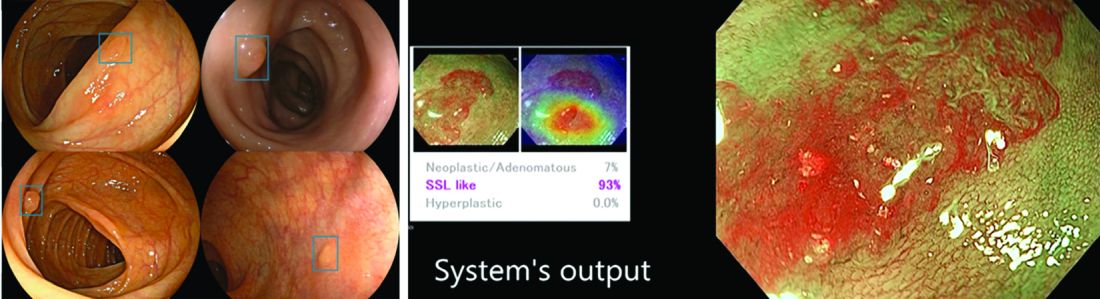

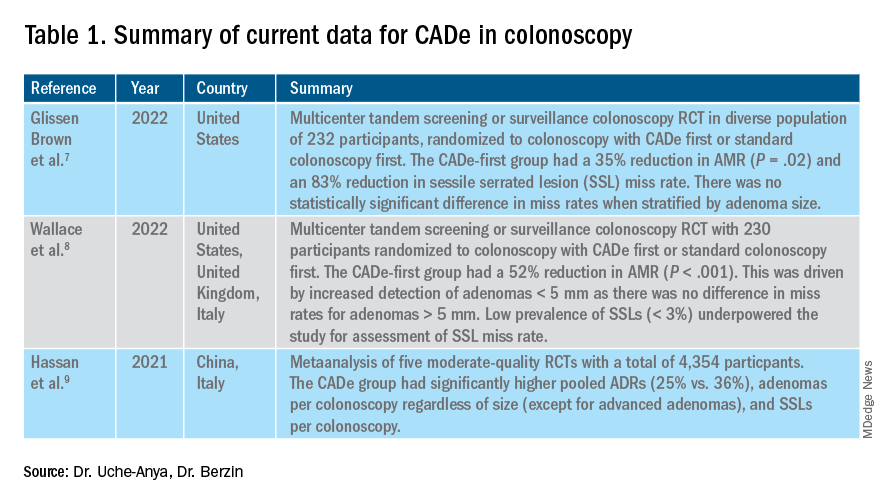

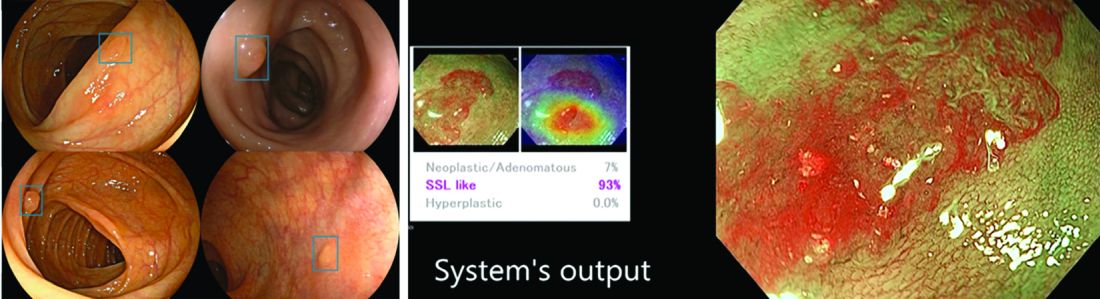

AI provides an opportunity for mitigating this risk. Advances in deep learning and computer vision have led to the development of CADe systems that automatically detect polyps in real time during colonoscopy, resulting in reduced adenoma miss rates (Table 1). In addition to polyp detection, deep-learning technologies are also being used in CADx systems for polyp diagnosis and characterization of malignancy risk. This could aid therapeutic decision-making: Unnecessary resection or histopathologic analysis could be obviated for benign hyperplastic polyps. On the other end of the polyp spectrum, an AI tool that could predict the presence or absence of submucosal invasion could be a powerful tool when evaluating early colon cancers for consideration of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. surgery. Examples of CADe polyp detection and CADx polyp characterization are shown in Figure 1.

Other potential computer vision applications that may improve colonoscopy quality include tools that help measure adequacy of mucosal exposure, segmental inspection time, and a variety of other parameters associated with polyp detection performance. These are promising areas for future research. Beyond improving colonoscopy technique, natural language processing tools already are being used to optimize clinical documentation as well as extract information from colonoscopy and pathology reports that can facilitate reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation adequacy. AI-powered analytics may help unlock large-scale reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics on a health-systems level5 or population-level,6 helping to ensure optimal performance and identifying avenues for colonoscopy quality improvement.

The majority of AI research in colonoscopy has focused on CADe for colon polyp detection and CADx for polyp diagnosis. Over the last few years, several randomized clinical trials – two in the United States – have shown that CADe significantly improves adenoma detection and reduces adenoma miss rates in comparison to standard colonoscopy. The existing data are summarized in Table 1, focusing on the two U.S. studies and an international meta-analysis.

In comparison, the data landscape for CADx is nascent and currently limited to several retrospective studies dating back to 2009 and a few prospective studies that have shown promising results.10,11 There is an expectation that integrated CADx also may support the adoption of “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave” strategies for low-risk polyps. About two-thirds of polyps identified on average-risk screening colonoscopies are diminutive polyps (less than 5 mm in size), which rarely have advanced histologic features (about 0.5%) and are sometimes non-neoplastic (30%). Malignancy risk is even lower in the distal colon.12 As routine histopathologic assessment of such polyps is mostly of limited clinical utility and comes with added pathology costs, CADx technologies may offer a more cost-effective approach where polyps that are characterized in real-time as low-risk adenomas or non-neoplastic are “resected and discarded” or “left in” respectively. In 2011, prior to the development of current AI tools, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy set performance thresholds for technologies supporting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. The ASGE recommended 90% histopathologic concordance for “resect and discard” tools and 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology for “diagnose and leave,” tools.13 Narrow-band imaging (NBI), for example, has been shown to meet these benchmarks14,15 with a modeling study suggesting that implementing “resect and discard” strategies with such tools could result in annual savings of $33 million without adversely affecting efficacy, although practical adoption has been limited.16 More recent work has directly explored the feasibility of leveraging CADx to support “leave-in-situ” and “resect-and-discard” strategies.17

Similarly, while CADe use in colonoscopy is associated with additional up-front costs, a modeling study suggests that its associated gains in ADR (as detailed in Table 1) make it a cost-saving strategy for colorectal cancer prevention in the long term.18 There is still uncertainty on whether the incremental CADe-associated gains in adenoma detection will necessarily translate to significant reductions in interval colorectal cancer risk, particularly for endoscopists who are already high-performing polyp detectors. A recent study suggests that, although higher ADRs were associated with lower rates of interval colorectal cancer, the gains in interval colorectal cancer risk reduction appeared to level off with ADRs above 35%-40% (this finding may be limited by statistical power).19 Further, most of the data from CADe trials suggest that gains in adenoma detection are not driven by increased detection of advanced lesions with high malignancy risk but by small polyps with long latency periods of about 5-10 years, which may not significantly alter interval cancer risk. It remains to be determined whether adoption of CADe will have an impact on hard outcomes, most importantly interval colorectal cancer risk, or merely result in increased resource utilization without moving the needle on colorectal cancer prevention. To answer this question, the OperA study – a large-scale randomized clinical trial of 200,000 patients across 18 centers from 13 countries – was launched in 2022. It will investigate the effect of colonoscopy with CADe on a number of critical measures, including long-term interval colon cancer risk.20

Despite commercial availability of regulatory-approved CADe systems and data supporting use for adenoma detection in colonoscopy, mainstream adoption in clinical practice has been sluggish. Physician survey studies have shown that, although there is considerable interest in integrating CADe into clinical practice, there are concerns about access, cost and reimbursement, integration into clinical work-flow, increased procedural times, over-reliance on AI, and algorithmic bias leading to errors.21,22 In addition, without mandatory requirements for ADR reporting or clinical practice guideline recommendations for CADe use, these systems may not be perceived as valuable or ready for prime time even though the evidence suggests otherwise.23,24 For CADe systems to see widespread adoption in clinical practice, it is important that future research studies rigorously investigate and characterize these potential barriers to better inform strategies to address AI hesitancy and implementation challenges. Such efforts can provide an integration framework for future AI applications in gastroenterology beyond colonoscopy, such as CADe of esophageal and gastric premalignant lesions in upper endoscopy, CADx for pancreatic cysts and liver lesions on imaging, NLP tools to optimizing efficient clinical documentation and reporting, and many others.

Dr. Uche-Anya is in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is with the Center for Advanced Endoscopy, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is a consultant for Wision AI, Medtronic, Magentiq Eye, RSIP Vision, and Docbot.

Corresponding Author: Eugenia Uche-Anya [email protected] Twitter: @UcheAnyaMD @tberzin

References

1. Corley DA et al. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2011;74(3):656-65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017.

2. Zhao S et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 05 2019;156(6):1661-74.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.260.

3. Kaminski MF et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. May 13 2010;362(19):1795-803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

4. Corley DA et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. Apr 03 2014;370(14):1298-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086.

5. Laique SN et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 03 2021;93(3):750-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.038.

6. Tinmouth J et al. Validation of a natural language processing algorithm to identify adenomas and measure adenoma detection rates across a health system: a population-level study. Gastrointest Endosc. Jul 14 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.07.009.

7. Glissen Brown JR et al. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multi-center randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2022;20(7):1499-1507.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.009.

8. Wallace MB et al. Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):295-304.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.007.

9. Hassan C et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 01 2021;93(1):77-85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059.

10. Glissen Brown JR and Berzin TM. Adoption of new technologies: Artificial intelligence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Oct 2021;31(4):743-58. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2021.05.010.

11. Larsen SLV and Mori Y. Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A review on the current status. DEN open. Apr 2022;2(1):e109. doi: 10.1002/deo2.109.

12. Gupta N et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2012;75(5):1022-30. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020.

13. Rex DK et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2011;73(3):419-22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2015;81(3):502.e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022.

15. Mori Y et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 18 2018;169(6):357-66. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249.

16. Hassan C et al.. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2010;8(10):865-9, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018.

17. Hassan C et al. Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2022;20(11):2505-13.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.045.

18. Areia M et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for screening colonoscopy: a modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 06 2022;4(6):e436-44. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5.

19. Schottinger JE et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022 Jun 7;327(21):2114-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6644.

20. Oslo Uo. Optimising colorectal cancer prevention through personalised treatment with artificial intelligence. 2022.

21. Wadhwa V et al. Physician sentiment toward artificial intelligence (AI) in colonoscopic practice: a survey of US gastroenterologists. Endosc Int Open. Oct 2020;8(10):E1379-84. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-1926.

22. Kader R et al. Survey on the perceptions of UK gastroenterologists and endoscopists to artificial intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022;13(5):423-9. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101994.

23. Rex DKet al. Artificial intelligence improves detection at colonoscopy: Why aren’t we all already using it? Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):35-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.042.

24. Ahmad OF et al. Establishing key research questions for the implementation of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A modified Delphi method. Endoscopy. 09 2021;53(9):893-901. doi: 10.1055/a-1306-7590

Considerable advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) methodologies have led to the emergence of promising tools in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Computer vision is an application of AI/ML that has been successfully applied for the computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) of colon polyps and numerous other conditions encountered during GI endoscopy. Outside of computer vision, a wide variety of other AI applications have been applied to gastroenterology, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) to optimize clinical documentation and endoscopy quality reporting to ML techniques that predict disease severity/treatment response and augment clinical decision-making.

In the United States, colonoscopy is the standard for colon cancer screening and prevention; however, precancerous polyps can be missed for various reasons, ranging from subtle surface appearance of the polyp or location behind a colonic fold to operator-dependent reasons such as inadequate mucosal inspection. Though clinical practice guidelines have set adenoma detection rate (ADR) thresholds at 20% for women and 30% for men, studies have shown a 4- to 10-fold variation in ADR among physicians in clinical practice settings,1 with an estimated adenoma miss rate (AMR) of 25% and a false-negative colonoscopy rate of 12%.2 Variability in adenoma detection affects the risk of interval colorectal cancer post colonoscopy.3,4

AI provides an opportunity for mitigating this risk. Advances in deep learning and computer vision have led to the development of CADe systems that automatically detect polyps in real time during colonoscopy, resulting in reduced adenoma miss rates (Table 1). In addition to polyp detection, deep-learning technologies are also being used in CADx systems for polyp diagnosis and characterization of malignancy risk. This could aid therapeutic decision-making: Unnecessary resection or histopathologic analysis could be obviated for benign hyperplastic polyps. On the other end of the polyp spectrum, an AI tool that could predict the presence or absence of submucosal invasion could be a powerful tool when evaluating early colon cancers for consideration of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. surgery. Examples of CADe polyp detection and CADx polyp characterization are shown in Figure 1.

Other potential computer vision applications that may improve colonoscopy quality include tools that help measure adequacy of mucosal exposure, segmental inspection time, and a variety of other parameters associated with polyp detection performance. These are promising areas for future research. Beyond improving colonoscopy technique, natural language processing tools already are being used to optimize clinical documentation as well as extract information from colonoscopy and pathology reports that can facilitate reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation adequacy. AI-powered analytics may help unlock large-scale reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics on a health-systems level5 or population-level,6 helping to ensure optimal performance and identifying avenues for colonoscopy quality improvement.

The majority of AI research in colonoscopy has focused on CADe for colon polyp detection and CADx for polyp diagnosis. Over the last few years, several randomized clinical trials – two in the United States – have shown that CADe significantly improves adenoma detection and reduces adenoma miss rates in comparison to standard colonoscopy. The existing data are summarized in Table 1, focusing on the two U.S. studies and an international meta-analysis.

In comparison, the data landscape for CADx is nascent and currently limited to several retrospective studies dating back to 2009 and a few prospective studies that have shown promising results.10,11 There is an expectation that integrated CADx also may support the adoption of “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave” strategies for low-risk polyps. About two-thirds of polyps identified on average-risk screening colonoscopies are diminutive polyps (less than 5 mm in size), which rarely have advanced histologic features (about 0.5%) and are sometimes non-neoplastic (30%). Malignancy risk is even lower in the distal colon.12 As routine histopathologic assessment of such polyps is mostly of limited clinical utility and comes with added pathology costs, CADx technologies may offer a more cost-effective approach where polyps that are characterized in real-time as low-risk adenomas or non-neoplastic are “resected and discarded” or “left in” respectively. In 2011, prior to the development of current AI tools, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy set performance thresholds for technologies supporting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. The ASGE recommended 90% histopathologic concordance for “resect and discard” tools and 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology for “diagnose and leave,” tools.13 Narrow-band imaging (NBI), for example, has been shown to meet these benchmarks14,15 with a modeling study suggesting that implementing “resect and discard” strategies with such tools could result in annual savings of $33 million without adversely affecting efficacy, although practical adoption has been limited.16 More recent work has directly explored the feasibility of leveraging CADx to support “leave-in-situ” and “resect-and-discard” strategies.17

Similarly, while CADe use in colonoscopy is associated with additional up-front costs, a modeling study suggests that its associated gains in ADR (as detailed in Table 1) make it a cost-saving strategy for colorectal cancer prevention in the long term.18 There is still uncertainty on whether the incremental CADe-associated gains in adenoma detection will necessarily translate to significant reductions in interval colorectal cancer risk, particularly for endoscopists who are already high-performing polyp detectors. A recent study suggests that, although higher ADRs were associated with lower rates of interval colorectal cancer, the gains in interval colorectal cancer risk reduction appeared to level off with ADRs above 35%-40% (this finding may be limited by statistical power).19 Further, most of the data from CADe trials suggest that gains in adenoma detection are not driven by increased detection of advanced lesions with high malignancy risk but by small polyps with long latency periods of about 5-10 years, which may not significantly alter interval cancer risk. It remains to be determined whether adoption of CADe will have an impact on hard outcomes, most importantly interval colorectal cancer risk, or merely result in increased resource utilization without moving the needle on colorectal cancer prevention. To answer this question, the OperA study – a large-scale randomized clinical trial of 200,000 patients across 18 centers from 13 countries – was launched in 2022. It will investigate the effect of colonoscopy with CADe on a number of critical measures, including long-term interval colon cancer risk.20

Despite commercial availability of regulatory-approved CADe systems and data supporting use for adenoma detection in colonoscopy, mainstream adoption in clinical practice has been sluggish. Physician survey studies have shown that, although there is considerable interest in integrating CADe into clinical practice, there are concerns about access, cost and reimbursement, integration into clinical work-flow, increased procedural times, over-reliance on AI, and algorithmic bias leading to errors.21,22 In addition, without mandatory requirements for ADR reporting or clinical practice guideline recommendations for CADe use, these systems may not be perceived as valuable or ready for prime time even though the evidence suggests otherwise.23,24 For CADe systems to see widespread adoption in clinical practice, it is important that future research studies rigorously investigate and characterize these potential barriers to better inform strategies to address AI hesitancy and implementation challenges. Such efforts can provide an integration framework for future AI applications in gastroenterology beyond colonoscopy, such as CADe of esophageal and gastric premalignant lesions in upper endoscopy, CADx for pancreatic cysts and liver lesions on imaging, NLP tools to optimizing efficient clinical documentation and reporting, and many others.

Dr. Uche-Anya is in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is with the Center for Advanced Endoscopy, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is a consultant for Wision AI, Medtronic, Magentiq Eye, RSIP Vision, and Docbot.

Corresponding Author: Eugenia Uche-Anya [email protected] Twitter: @UcheAnyaMD @tberzin

References

1. Corley DA et al. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2011;74(3):656-65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017.

2. Zhao S et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 05 2019;156(6):1661-74.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.260.

3. Kaminski MF et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. May 13 2010;362(19):1795-803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

4. Corley DA et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. Apr 03 2014;370(14):1298-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086.

5. Laique SN et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 03 2021;93(3):750-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.038.

6. Tinmouth J et al. Validation of a natural language processing algorithm to identify adenomas and measure adenoma detection rates across a health system: a population-level study. Gastrointest Endosc. Jul 14 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.07.009.

7. Glissen Brown JR et al. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multi-center randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2022;20(7):1499-1507.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.009.

8. Wallace MB et al. Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):295-304.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.007.

9. Hassan C et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 01 2021;93(1):77-85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059.

10. Glissen Brown JR and Berzin TM. Adoption of new technologies: Artificial intelligence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Oct 2021;31(4):743-58. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2021.05.010.

11. Larsen SLV and Mori Y. Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A review on the current status. DEN open. Apr 2022;2(1):e109. doi: 10.1002/deo2.109.

12. Gupta N et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2012;75(5):1022-30. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020.

13. Rex DK et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2011;73(3):419-22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2015;81(3):502.e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022.

15. Mori Y et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 18 2018;169(6):357-66. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249.

16. Hassan C et al.. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2010;8(10):865-9, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018.

17. Hassan C et al. Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2022;20(11):2505-13.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.045.

18. Areia M et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for screening colonoscopy: a modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 06 2022;4(6):e436-44. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5.

19. Schottinger JE et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022 Jun 7;327(21):2114-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6644.

20. Oslo Uo. Optimising colorectal cancer prevention through personalised treatment with artificial intelligence. 2022.

21. Wadhwa V et al. Physician sentiment toward artificial intelligence (AI) in colonoscopic practice: a survey of US gastroenterologists. Endosc Int Open. Oct 2020;8(10):E1379-84. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-1926.

22. Kader R et al. Survey on the perceptions of UK gastroenterologists and endoscopists to artificial intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022;13(5):423-9. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101994.

23. Rex DKet al. Artificial intelligence improves detection at colonoscopy: Why aren’t we all already using it? Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):35-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.042.

24. Ahmad OF et al. Establishing key research questions for the implementation of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A modified Delphi method. Endoscopy. 09 2021;53(9):893-901. doi: 10.1055/a-1306-7590

Considerable advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine-learning (ML) methodologies have led to the emergence of promising tools in the field of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Computer vision is an application of AI/ML that has been successfully applied for the computer-aided detection (CADe) and computer-aided diagnosis (CADx) of colon polyps and numerous other conditions encountered during GI endoscopy. Outside of computer vision, a wide variety of other AI applications have been applied to gastroenterology, ranging from natural language processing (NLP) to optimize clinical documentation and endoscopy quality reporting to ML techniques that predict disease severity/treatment response and augment clinical decision-making.

In the United States, colonoscopy is the standard for colon cancer screening and prevention; however, precancerous polyps can be missed for various reasons, ranging from subtle surface appearance of the polyp or location behind a colonic fold to operator-dependent reasons such as inadequate mucosal inspection. Though clinical practice guidelines have set adenoma detection rate (ADR) thresholds at 20% for women and 30% for men, studies have shown a 4- to 10-fold variation in ADR among physicians in clinical practice settings,1 with an estimated adenoma miss rate (AMR) of 25% and a false-negative colonoscopy rate of 12%.2 Variability in adenoma detection affects the risk of interval colorectal cancer post colonoscopy.3,4

AI provides an opportunity for mitigating this risk. Advances in deep learning and computer vision have led to the development of CADe systems that automatically detect polyps in real time during colonoscopy, resulting in reduced adenoma miss rates (Table 1). In addition to polyp detection, deep-learning technologies are also being used in CADx systems for polyp diagnosis and characterization of malignancy risk. This could aid therapeutic decision-making: Unnecessary resection or histopathologic analysis could be obviated for benign hyperplastic polyps. On the other end of the polyp spectrum, an AI tool that could predict the presence or absence of submucosal invasion could be a powerful tool when evaluating early colon cancers for consideration of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs. surgery. Examples of CADe polyp detection and CADx polyp characterization are shown in Figure 1.

Other potential computer vision applications that may improve colonoscopy quality include tools that help measure adequacy of mucosal exposure, segmental inspection time, and a variety of other parameters associated with polyp detection performance. These are promising areas for future research. Beyond improving colonoscopy technique, natural language processing tools already are being used to optimize clinical documentation as well as extract information from colonoscopy and pathology reports that can facilitate reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics such as ADR, cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation adequacy. AI-powered analytics may help unlock large-scale reporting of colonoscopy quality metrics on a health-systems level5 or population-level,6 helping to ensure optimal performance and identifying avenues for colonoscopy quality improvement.

The majority of AI research in colonoscopy has focused on CADe for colon polyp detection and CADx for polyp diagnosis. Over the last few years, several randomized clinical trials – two in the United States – have shown that CADe significantly improves adenoma detection and reduces adenoma miss rates in comparison to standard colonoscopy. The existing data are summarized in Table 1, focusing on the two U.S. studies and an international meta-analysis.

In comparison, the data landscape for CADx is nascent and currently limited to several retrospective studies dating back to 2009 and a few prospective studies that have shown promising results.10,11 There is an expectation that integrated CADx also may support the adoption of “resect and discard” or “diagnose and leave” strategies for low-risk polyps. About two-thirds of polyps identified on average-risk screening colonoscopies are diminutive polyps (less than 5 mm in size), which rarely have advanced histologic features (about 0.5%) and are sometimes non-neoplastic (30%). Malignancy risk is even lower in the distal colon.12 As routine histopathologic assessment of such polyps is mostly of limited clinical utility and comes with added pathology costs, CADx technologies may offer a more cost-effective approach where polyps that are characterized in real-time as low-risk adenomas or non-neoplastic are “resected and discarded” or “left in” respectively. In 2011, prior to the development of current AI tools, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy set performance thresholds for technologies supporting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. The ASGE recommended 90% histopathologic concordance for “resect and discard” tools and 90% negative predictive value for adenomatous histology for “diagnose and leave,” tools.13 Narrow-band imaging (NBI), for example, has been shown to meet these benchmarks14,15 with a modeling study suggesting that implementing “resect and discard” strategies with such tools could result in annual savings of $33 million without adversely affecting efficacy, although practical adoption has been limited.16 More recent work has directly explored the feasibility of leveraging CADx to support “leave-in-situ” and “resect-and-discard” strategies.17

Similarly, while CADe use in colonoscopy is associated with additional up-front costs, a modeling study suggests that its associated gains in ADR (as detailed in Table 1) make it a cost-saving strategy for colorectal cancer prevention in the long term.18 There is still uncertainty on whether the incremental CADe-associated gains in adenoma detection will necessarily translate to significant reductions in interval colorectal cancer risk, particularly for endoscopists who are already high-performing polyp detectors. A recent study suggests that, although higher ADRs were associated with lower rates of interval colorectal cancer, the gains in interval colorectal cancer risk reduction appeared to level off with ADRs above 35%-40% (this finding may be limited by statistical power).19 Further, most of the data from CADe trials suggest that gains in adenoma detection are not driven by increased detection of advanced lesions with high malignancy risk but by small polyps with long latency periods of about 5-10 years, which may not significantly alter interval cancer risk. It remains to be determined whether adoption of CADe will have an impact on hard outcomes, most importantly interval colorectal cancer risk, or merely result in increased resource utilization without moving the needle on colorectal cancer prevention. To answer this question, the OperA study – a large-scale randomized clinical trial of 200,000 patients across 18 centers from 13 countries – was launched in 2022. It will investigate the effect of colonoscopy with CADe on a number of critical measures, including long-term interval colon cancer risk.20

Despite commercial availability of regulatory-approved CADe systems and data supporting use for adenoma detection in colonoscopy, mainstream adoption in clinical practice has been sluggish. Physician survey studies have shown that, although there is considerable interest in integrating CADe into clinical practice, there are concerns about access, cost and reimbursement, integration into clinical work-flow, increased procedural times, over-reliance on AI, and algorithmic bias leading to errors.21,22 In addition, without mandatory requirements for ADR reporting or clinical practice guideline recommendations for CADe use, these systems may not be perceived as valuable or ready for prime time even though the evidence suggests otherwise.23,24 For CADe systems to see widespread adoption in clinical practice, it is important that future research studies rigorously investigate and characterize these potential barriers to better inform strategies to address AI hesitancy and implementation challenges. Such efforts can provide an integration framework for future AI applications in gastroenterology beyond colonoscopy, such as CADe of esophageal and gastric premalignant lesions in upper endoscopy, CADx for pancreatic cysts and liver lesions on imaging, NLP tools to optimizing efficient clinical documentation and reporting, and many others.

Dr. Uche-Anya is in the division of gastroenterology, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is with the Center for Advanced Endoscopy, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Berzin is a consultant for Wision AI, Medtronic, Magentiq Eye, RSIP Vision, and Docbot.

Corresponding Author: Eugenia Uche-Anya [email protected] Twitter: @UcheAnyaMD @tberzin

References

1. Corley DA et al. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc. Sep 2011;74(3):656-65. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017.

2. Zhao S et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 05 2019;156(6):1661-74.e11. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.260.

3. Kaminski MF et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. May 13 2010;362(19):1795-803. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907667.

4. Corley DA et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. Apr 03 2014;370(14):1298-306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086.

5. Laique SN et al. Application of optical character recognition with natural language processing for large-scale quality metric data extraction in colonoscopy reports. Gastrointest Endosc. 03 2021;93(3):750-7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.08.038.

6. Tinmouth J et al. Validation of a natural language processing algorithm to identify adenomas and measure adenoma detection rates across a health system: a population-level study. Gastrointest Endosc. Jul 14 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2022.07.009.

7. Glissen Brown JR et al. Deep learning computer-aided polyp detection reduces adenoma miss rate: A United States multi-center randomized tandem colonoscopy study (CADeT-CS Trial). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 07 2022;20(7):1499-1507.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.09.009.

8. Wallace MB et al. Impact of artificial intelligence on miss rate of colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):295-304.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.007.

9. Hassan C et al. Performance of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy for adenoma and polyp detection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 01 2021;93(1):77-85.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.059.

10. Glissen Brown JR and Berzin TM. Adoption of new technologies: Artificial intelligence. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. Oct 2021;31(4):743-58. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2021.05.010.

11. Larsen SLV and Mori Y. Artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A review on the current status. DEN open. Apr 2022;2(1):e109. doi: 10.1002/deo2.109.

12. Gupta N et al. Prevalence of advanced histological features in diminutive and small colon polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. May 2012;75(5):1022-30. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.01.020.

13. Rex DK et al. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy PIVI (Preservation and Incorporation of Valuable Endoscopic Innovations) on real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2011;73(3):419-22. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.023.

14. Abu Dayyeh BK et al. ASGE Technology Committee systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting real-time endoscopic assessment of the histology of diminutive colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. Mar 2015;81(3):502.e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.022.

15. Mori Y et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. Sep 18 2018;169(6):357-66. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249.

16. Hassan C et al.. A resect and discard strategy would improve cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Oct 2010;8(10):865-9, 869.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.05.018.

17. Hassan C et al. Artificial intelligence allows leaving-in-situ colorectal polyps. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Nov 2022;20(11):2505-13.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.045.

18. Areia M et al. Cost-effectiveness of artificial intelligence for screening colonoscopy: a modelling study. Lancet Digit Health. 06 2022;4(6):e436-44. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00042-5.

19. Schottinger JE et al. Association of physician adenoma detection rates with postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2022 Jun 7;327(21):2114-22. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.6644.

20. Oslo Uo. Optimising colorectal cancer prevention through personalised treatment with artificial intelligence. 2022.

21. Wadhwa V et al. Physician sentiment toward artificial intelligence (AI) in colonoscopic practice: a survey of US gastroenterologists. Endosc Int Open. Oct 2020;8(10):E1379-84. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-1926.

22. Kader R et al. Survey on the perceptions of UK gastroenterologists and endoscopists to artificial intelligence. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2022;13(5):423-9. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2021-101994.

23. Rex DKet al. Artificial intelligence improves detection at colonoscopy: Why aren’t we all already using it? Gastroenterology. 07 2022;163(1):35-7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.04.042.

24. Ahmad OF et al. Establishing key research questions for the implementation of artificial intelligence in colonoscopy: A modified Delphi method. Endoscopy. 09 2021;53(9):893-901. doi: 10.1055/a-1306-7590

How does SARS-CoV-2 affect other respiratory diseases?

In 2020, the rapid spread of the newly identified SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus led various global public health institutions to establish strategies to stop transmission and reduce mortality. Nonpharmacological measures – including social distancing, regular hand washing, and the use of face masks – contributed to reducing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health systems in different regions of the world. However, because of the implementation of these measures, the transmission of other infectious agents also experienced a marked reduction.

Approximately 3 years after the start of the pandemic, , generating phenomena ranging from an immunity gap, which favors the increase in some diseases, to the apparent disappearance of an influenza virus lineage.

Understanding the phenomenon

In mid-2021, doctors and researchers around the world began to share their opinions about the side effect of the strict measures implemented to contain COVID-19.

In May 2021, along with some coresearchers, Emmanuel Grimprel, MD, of the Pediatric Infectious Pathology Group in Créteil, France, wrote for Infectious Disease Now, “The transmission of some pathogens is often similar to that of SARS-CoV-2, essentially large droplets, aerosols, and direct hand contact, often with lower transmissibility. The lack of immune system stimulation due to nonpharmaceutical measures induces an ‘immune debt’ that may have negative consequences when the pandemic is under control.” According to the authors, mathematical models evaluated up to that point were already suggesting that the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza A epidemics would be more serious in subsequent years.

In July 2022, a commentary in The Lancet led by Kevin Messacar, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, grew in relevance and gave prominence to the phenomenon. In the commentary, Dr. Messacar and a group of experts explained how the decrease in exposure to endemic viruses had given rise to an immunity gap.

“The immunity gap phenomenon that has been reported in articles such as The Lancet publication is mainly due to the isolation that took place to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although this distancing was a good response to combat infections, or at least delay them while coronavirus research advanced, what we are now experiencing is the increase in cases of respiratory diseases caused by other agents such as respiratory syncytial virus and influenza due to lack of exposure,” as explained to this news organization by Erandeni Martínez Jiménez, biomedicine graduate and member of the Medical Virology Laboratory of the Mexican Institute of Social Security, at the Zone No. 5 General Hospital in Metepec-Atlixco, Mexico.

“This phenomenon occurs in all age groups. However, it is more evident in children and babies, since at their age, they have been exposed to fewer pathogens and, when added to isolation, makes this immunity gap more evident. Many immunologists compare this to hygiene theory in which it is explained that a ‘sterile’ environment will cause children to avoid the everyday and common pathogens required to be able to develop an adequate immune system,” added Martínez Jimenez.

“In addition, due to the isolation, the vaccination rate in children decreased, since many parents did not risk their children going out. This causes the immunity gap to grow even further as these children are not protected against common pathogens. While a mother passes antibodies to the child through the uterus via her placenta, the mother will only pass on those antibodies to which she has been exposed and as expected due to the lockdown, exposure to other pathogens has been greatly reduced.”

On the other hand, Andreu Comas, MD, PhD, MHS, of the Center for Research in Health Sciences and Biomedicine of the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí (Mexico), considered that there are other immunity gaps that are not limited to respiratory infections and that are related to the fall in vaccination coverage. “Children are going to experience several immunity gaps. In the middle of the previous 6-year term, we had a vaccination schedule coverage of around 70% for children. Now that vaccination coverage has fallen to 30%, today we have an immunity gap for measles, rubella, mumps, tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, and meningeal tuberculosis. We have a significant growth or risk for other diseases.”

Lineage extinction

Three types of influenza viruses – A, B, and C – cause infections in humans. Although influenza A virus is the main type associated with infections during seasonal periods, as of 2020, influenza B virus was considered the causative agent of about a quarter of annual influenza cases.

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, cocirculation of the two distinct lineages of influenza B viruses, B/Victoria/2/1987 (B/Victoria) and B/Yamagata/16/1988 (B/Yamagata), decreased significantly. According to data from the FluNet tool, which is coordinated by the World Health Organization, since March 2020 the isolation or sequencing of viruses belonging to the Yamagata lineage was not conclusively carried out.

Specialists like John Paget, PhD, from the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (Nivel) in Utrecht, have indicated that determining the extinction of the B/Yamagata lineage is critical. There is the possibility of a reintroduction of the lineage, as has occurred in the past with the reemergence of influenza A (H1N1) in 1997, which could represent a risk in subsequent years.

“In the next few years, research related to viruses such as influenza B and the impact on population immunity will be important. Let’s remember that influenza changes every year due to its characteristics, so a lack of exposure will also have an impact on the development of the disease,” said Martínez Jiménez.

Vaccination is essential

According to Dr. Comas, the only way to overcome the immunity gap phenomenon is through vaccination campaigns. “There is no other way to overcome the phenomenon, and how fast it is done will depend on the effort,” he said.

“In the case of COVID-19, it is not planned to vaccinate children under 5 years of age, and if we do not vaccinate children under 5 years of age, that gap will exist. In addition, this winter season will be important to know whether we are already endemic or not. It will be the key point, and it will determine if we will have a peak or not in the summer.

“In the case of the rest of the diseases, we need to correct what has been deficient in different governments, and we are going to have the resurgence of other infectious diseases that had already been forgotten. We have the example of poliomyelitis, the increase in meningeal tuberculosis, and we will have an increase in whooping cough and pertussislike syndrome. In this sense, we are going back to the point where Mexico and the world were around the ‘60s and ‘70s, and we have to be very alert to detect, isolate, and revaccinate.”

Finally, Dr. Comas called for continuing precautionary measures before the arrival of the sixth wave. “At a national level, the sixth wave of COVID-19 has already begun, and an increase in cases is expected in January. Regarding vaccines, if you are over 18 years of age and have not had any vaccine dose, you can get Abdala, however, there are no studies on this vaccine as a booster, and it is not authorized by the Mexican government for this purpose. Therefore, it is necessary to continue with measures such as the use of face masks in crowded places or with poor ventilation, and in the event of having symptoms, avoid going out and encourage ventilation at work and schools. If we do this, at least in the case of diseases that are transmitted by the respiratory route, the impact will be minimal.”

Martínez Jiménez and Dr. Comas have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2020, the rapid spread of the newly identified SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus led various global public health institutions to establish strategies to stop transmission and reduce mortality. Nonpharmacological measures – including social distancing, regular hand washing, and the use of face masks – contributed to reducing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health systems in different regions of the world. However, because of the implementation of these measures, the transmission of other infectious agents also experienced a marked reduction.

Approximately 3 years after the start of the pandemic, , generating phenomena ranging from an immunity gap, which favors the increase in some diseases, to the apparent disappearance of an influenza virus lineage.

Understanding the phenomenon

In mid-2021, doctors and researchers around the world began to share their opinions about the side effect of the strict measures implemented to contain COVID-19.

In May 2021, along with some coresearchers, Emmanuel Grimprel, MD, of the Pediatric Infectious Pathology Group in Créteil, France, wrote for Infectious Disease Now, “The transmission of some pathogens is often similar to that of SARS-CoV-2, essentially large droplets, aerosols, and direct hand contact, often with lower transmissibility. The lack of immune system stimulation due to nonpharmaceutical measures induces an ‘immune debt’ that may have negative consequences when the pandemic is under control.” According to the authors, mathematical models evaluated up to that point were already suggesting that the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza A epidemics would be more serious in subsequent years.

In July 2022, a commentary in The Lancet led by Kevin Messacar, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, grew in relevance and gave prominence to the phenomenon. In the commentary, Dr. Messacar and a group of experts explained how the decrease in exposure to endemic viruses had given rise to an immunity gap.

“The immunity gap phenomenon that has been reported in articles such as The Lancet publication is mainly due to the isolation that took place to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although this distancing was a good response to combat infections, or at least delay them while coronavirus research advanced, what we are now experiencing is the increase in cases of respiratory diseases caused by other agents such as respiratory syncytial virus and influenza due to lack of exposure,” as explained to this news organization by Erandeni Martínez Jiménez, biomedicine graduate and member of the Medical Virology Laboratory of the Mexican Institute of Social Security, at the Zone No. 5 General Hospital in Metepec-Atlixco, Mexico.

“This phenomenon occurs in all age groups. However, it is more evident in children and babies, since at their age, they have been exposed to fewer pathogens and, when added to isolation, makes this immunity gap more evident. Many immunologists compare this to hygiene theory in which it is explained that a ‘sterile’ environment will cause children to avoid the everyday and common pathogens required to be able to develop an adequate immune system,” added Martínez Jimenez.

“In addition, due to the isolation, the vaccination rate in children decreased, since many parents did not risk their children going out. This causes the immunity gap to grow even further as these children are not protected against common pathogens. While a mother passes antibodies to the child through the uterus via her placenta, the mother will only pass on those antibodies to which she has been exposed and as expected due to the lockdown, exposure to other pathogens has been greatly reduced.”

On the other hand, Andreu Comas, MD, PhD, MHS, of the Center for Research in Health Sciences and Biomedicine of the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí (Mexico), considered that there are other immunity gaps that are not limited to respiratory infections and that are related to the fall in vaccination coverage. “Children are going to experience several immunity gaps. In the middle of the previous 6-year term, we had a vaccination schedule coverage of around 70% for children. Now that vaccination coverage has fallen to 30%, today we have an immunity gap for measles, rubella, mumps, tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, and meningeal tuberculosis. We have a significant growth or risk for other diseases.”

Lineage extinction

Three types of influenza viruses – A, B, and C – cause infections in humans. Although influenza A virus is the main type associated with infections during seasonal periods, as of 2020, influenza B virus was considered the causative agent of about a quarter of annual influenza cases.

During the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, cocirculation of the two distinct lineages of influenza B viruses, B/Victoria/2/1987 (B/Victoria) and B/Yamagata/16/1988 (B/Yamagata), decreased significantly. According to data from the FluNet tool, which is coordinated by the World Health Organization, since March 2020 the isolation or sequencing of viruses belonging to the Yamagata lineage was not conclusively carried out.

Specialists like John Paget, PhD, from the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (Nivel) in Utrecht, have indicated that determining the extinction of the B/Yamagata lineage is critical. There is the possibility of a reintroduction of the lineage, as has occurred in the past with the reemergence of influenza A (H1N1) in 1997, which could represent a risk in subsequent years.

“In the next few years, research related to viruses such as influenza B and the impact on population immunity will be important. Let’s remember that influenza changes every year due to its characteristics, so a lack of exposure will also have an impact on the development of the disease,” said Martínez Jiménez.

Vaccination is essential

According to Dr. Comas, the only way to overcome the immunity gap phenomenon is through vaccination campaigns. “There is no other way to overcome the phenomenon, and how fast it is done will depend on the effort,” he said.

“In the case of COVID-19, it is not planned to vaccinate children under 5 years of age, and if we do not vaccinate children under 5 years of age, that gap will exist. In addition, this winter season will be important to know whether we are already endemic or not. It will be the key point, and it will determine if we will have a peak or not in the summer.

“In the case of the rest of the diseases, we need to correct what has been deficient in different governments, and we are going to have the resurgence of other infectious diseases that had already been forgotten. We have the example of poliomyelitis, the increase in meningeal tuberculosis, and we will have an increase in whooping cough and pertussislike syndrome. In this sense, we are going back to the point where Mexico and the world were around the ‘60s and ‘70s, and we have to be very alert to detect, isolate, and revaccinate.”

Finally, Dr. Comas called for continuing precautionary measures before the arrival of the sixth wave. “At a national level, the sixth wave of COVID-19 has already begun, and an increase in cases is expected in January. Regarding vaccines, if you are over 18 years of age and have not had any vaccine dose, you can get Abdala, however, there are no studies on this vaccine as a booster, and it is not authorized by the Mexican government for this purpose. Therefore, it is necessary to continue with measures such as the use of face masks in crowded places or with poor ventilation, and in the event of having symptoms, avoid going out and encourage ventilation at work and schools. If we do this, at least in the case of diseases that are transmitted by the respiratory route, the impact will be minimal.”

Martínez Jiménez and Dr. Comas have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article was translated from the Medscape Spanish Edition.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2020, the rapid spread of the newly identified SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus led various global public health institutions to establish strategies to stop transmission and reduce mortality. Nonpharmacological measures – including social distancing, regular hand washing, and the use of face masks – contributed to reducing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health systems in different regions of the world. However, because of the implementation of these measures, the transmission of other infectious agents also experienced a marked reduction.

Approximately 3 years after the start of the pandemic, , generating phenomena ranging from an immunity gap, which favors the increase in some diseases, to the apparent disappearance of an influenza virus lineage.

Understanding the phenomenon

In mid-2021, doctors and researchers around the world began to share their opinions about the side effect of the strict measures implemented to contain COVID-19.

In May 2021, along with some coresearchers, Emmanuel Grimprel, MD, of the Pediatric Infectious Pathology Group in Créteil, France, wrote for Infectious Disease Now, “The transmission of some pathogens is often similar to that of SARS-CoV-2, essentially large droplets, aerosols, and direct hand contact, often with lower transmissibility. The lack of immune system stimulation due to nonpharmaceutical measures induces an ‘immune debt’ that may have negative consequences when the pandemic is under control.” According to the authors, mathematical models evaluated up to that point were already suggesting that the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza A epidemics would be more serious in subsequent years.

In July 2022, a commentary in The Lancet led by Kevin Messacar, MD, of the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, grew in relevance and gave prominence to the phenomenon. In the commentary, Dr. Messacar and a group of experts explained how the decrease in exposure to endemic viruses had given rise to an immunity gap.

“The immunity gap phenomenon that has been reported in articles such as The Lancet publication is mainly due to the isolation that took place to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infections. Although this distancing was a good response to combat infections, or at least delay them while coronavirus research advanced, what we are now experiencing is the increase in cases of respiratory diseases caused by other agents such as respiratory syncytial virus and influenza due to lack of exposure,” as explained to this news organization by Erandeni Martínez Jiménez, biomedicine graduate and member of the Medical Virology Laboratory of the Mexican Institute of Social Security, at the Zone No. 5 General Hospital in Metepec-Atlixco, Mexico.

“This phenomenon occurs in all age groups. However, it is more evident in children and babies, since at their age, they have been exposed to fewer pathogens and, when added to isolation, makes this immunity gap more evident. Many immunologists compare this to hygiene theory in which it is explained that a ‘sterile’ environment will cause children to avoid the everyday and common pathogens required to be able to develop an adequate immune system,” added Martínez Jimenez.

“In addition, due to the isolation, the vaccination rate in children decreased, since many parents did not risk their children going out. This causes the immunity gap to grow even further as these children are not protected against common pathogens. While a mother passes antibodies to the child through the uterus via her placenta, the mother will only pass on those antibodies to which she has been exposed and as expected due to the lockdown, exposure to other pathogens has been greatly reduced.”

On the other hand, Andreu Comas, MD, PhD, MHS, of the Center for Research in Health Sciences and Biomedicine of the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí (Mexico), considered that there are other immunity gaps that are not limited to respiratory infections and that are related to the fall in vaccination coverage. “Children are going to experience several immunity gaps. In the middle of the previous 6-year term, we had a vaccination schedule coverage of around 70% for children. Now that vaccination coverage has fallen to 30%, today we have an immunity gap for measles, rubella, mumps, tetanus, diphtheria, whooping cough, and meningeal tuberculosis. We have a significant growth or risk for other diseases.”

Lineage extinction