User login

Surgeon gender not associated with maternal morbidity and hemorrhage after C-section

Surgeon gender was not associated with maternal morbidity or severe blood loss after cesarean delivery, a large prospective cohort study from France reports. The results have important implications for the promotion of gender equality among surgeons, obstetricians in particular, wrote a team led by Hanane Bouchghoul, MD, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Bordeaux (France) University Hospital. The report is in JAMA Surgery.

“Our findings are significant in that they add substantially to the string of studies contradicting the age-old dogma that men are better surgeons than women,” the authors wrote. Previous research has suggested slightly better outcomes with female surgeons or higher complication rates with male surgeons.

The results support those of a recent Canadian retrospective analysis suggesting that patients treated by male or female surgeons for various elective indications experience similar surgical outcomes but with a slight, statistically significant decrease in 30-day mortality when treated by female surgeons.

“Policy makers need to combat prejudice against women in surgical careers, particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, so that women no longer experience conscious or unconscious barriers or difficulties in their professional choices, training, and relationships with colleagues or patients,” study corresponding author Loïc Sentilhes, MD, PhD, of Bordeaux University Hospital, said in an interview.

Facing such barriers, women may doubt their ability to be surgeons, their legitimacy as surgeons, and may not consider this type of career, he continued. “Moreover a teacher may not be as involved in teaching young female surgeons as young male surgeons, or the doctor-patient relationship may be more complicated in the event of complications if the patient thinks that a female surgeon has less competence than a male surgeon.”

The analysis drew on data from the Tranexamic Acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery 2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted from March 2018 through January 2020 in mothers from 27 French maternity hospitals.

Eligible participants had a cesarean delivery before or during labor at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite maternal morbidity variable, and the secondary endpoint was the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, defined by a calculated estimated blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL or transfusion by day 2.

Among the 4,244 women included, male surgeons performed 943 cesarean deliveries (22.2%) and female surgeons performed 3,301 (77.8%). The percentage who were attending obstetricians was higher for men at 441 of 929 (47.5%) than women at 687 of 3,239 (21.2%).

The observed risk of maternal morbidity did not differ between male and female surgeons: 119 of 837 (14.2%) vs. 476 of 2,928 (16.3%), for an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-1.13). Interaction between surgeon gender and level of experience with the risk of maternal morbidity was not statistically significant; nor did the groups differ specifically by risk for postpartum hemorrhage: aRR, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85-1.13).

Despite the longstanding stereotype that men perform surgery better than women, and the traditional preponderance of male surgeons, the authors noted, postoperative morbidity and mortality may be lower after various surgeries performed by women.

The TRAAP2 trial

In an accompanying editorial, Amanda Fader, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and colleagues caution that the French study’s methodology may not fully account for the complex intersection of surgeon volume, experience, gender, clinical decision-making skills, and patient-level and clinical factors affecting outcomes.

That said, appraising surgical outcomes based on gender may be an essential step toward reducing implicit bias and dispelling engendered perceptions regarding gender and technical proficiency, the commentators stated. “To definitively dispel archaic, gender-based notions about performance in clinical or surgical settings, efforts must go beyond peer-reviewed research,” Dr. Fader said in an interview. “Medical institutions and leaders of clinical departments must make concerted efforts to recruit, mentor, support, and promote women and persons of all genders in medicine – as well as confront any discriminatory perceptions and experiences concerning sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or economic class.”

This study was supported by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program. Dr. Sentilhes reported financial relationships with Dilafor, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sigvaris, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The editorial commentators disclosed no funding for their commentary or conflicts of interest.

Surgeon gender was not associated with maternal morbidity or severe blood loss after cesarean delivery, a large prospective cohort study from France reports. The results have important implications for the promotion of gender equality among surgeons, obstetricians in particular, wrote a team led by Hanane Bouchghoul, MD, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Bordeaux (France) University Hospital. The report is in JAMA Surgery.

“Our findings are significant in that they add substantially to the string of studies contradicting the age-old dogma that men are better surgeons than women,” the authors wrote. Previous research has suggested slightly better outcomes with female surgeons or higher complication rates with male surgeons.

The results support those of a recent Canadian retrospective analysis suggesting that patients treated by male or female surgeons for various elective indications experience similar surgical outcomes but with a slight, statistically significant decrease in 30-day mortality when treated by female surgeons.

“Policy makers need to combat prejudice against women in surgical careers, particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, so that women no longer experience conscious or unconscious barriers or difficulties in their professional choices, training, and relationships with colleagues or patients,” study corresponding author Loïc Sentilhes, MD, PhD, of Bordeaux University Hospital, said in an interview.

Facing such barriers, women may doubt their ability to be surgeons, their legitimacy as surgeons, and may not consider this type of career, he continued. “Moreover a teacher may not be as involved in teaching young female surgeons as young male surgeons, or the doctor-patient relationship may be more complicated in the event of complications if the patient thinks that a female surgeon has less competence than a male surgeon.”

The analysis drew on data from the Tranexamic Acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery 2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted from March 2018 through January 2020 in mothers from 27 French maternity hospitals.

Eligible participants had a cesarean delivery before or during labor at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite maternal morbidity variable, and the secondary endpoint was the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, defined by a calculated estimated blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL or transfusion by day 2.

Among the 4,244 women included, male surgeons performed 943 cesarean deliveries (22.2%) and female surgeons performed 3,301 (77.8%). The percentage who were attending obstetricians was higher for men at 441 of 929 (47.5%) than women at 687 of 3,239 (21.2%).

The observed risk of maternal morbidity did not differ between male and female surgeons: 119 of 837 (14.2%) vs. 476 of 2,928 (16.3%), for an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-1.13). Interaction between surgeon gender and level of experience with the risk of maternal morbidity was not statistically significant; nor did the groups differ specifically by risk for postpartum hemorrhage: aRR, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85-1.13).

Despite the longstanding stereotype that men perform surgery better than women, and the traditional preponderance of male surgeons, the authors noted, postoperative morbidity and mortality may be lower after various surgeries performed by women.

The TRAAP2 trial

In an accompanying editorial, Amanda Fader, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and colleagues caution that the French study’s methodology may not fully account for the complex intersection of surgeon volume, experience, gender, clinical decision-making skills, and patient-level and clinical factors affecting outcomes.

That said, appraising surgical outcomes based on gender may be an essential step toward reducing implicit bias and dispelling engendered perceptions regarding gender and technical proficiency, the commentators stated. “To definitively dispel archaic, gender-based notions about performance in clinical or surgical settings, efforts must go beyond peer-reviewed research,” Dr. Fader said in an interview. “Medical institutions and leaders of clinical departments must make concerted efforts to recruit, mentor, support, and promote women and persons of all genders in medicine – as well as confront any discriminatory perceptions and experiences concerning sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or economic class.”

This study was supported by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program. Dr. Sentilhes reported financial relationships with Dilafor, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sigvaris, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The editorial commentators disclosed no funding for their commentary or conflicts of interest.

Surgeon gender was not associated with maternal morbidity or severe blood loss after cesarean delivery, a large prospective cohort study from France reports. The results have important implications for the promotion of gender equality among surgeons, obstetricians in particular, wrote a team led by Hanane Bouchghoul, MD, PhD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Bordeaux (France) University Hospital. The report is in JAMA Surgery.

“Our findings are significant in that they add substantially to the string of studies contradicting the age-old dogma that men are better surgeons than women,” the authors wrote. Previous research has suggested slightly better outcomes with female surgeons or higher complication rates with male surgeons.

The results support those of a recent Canadian retrospective analysis suggesting that patients treated by male or female surgeons for various elective indications experience similar surgical outcomes but with a slight, statistically significant decrease in 30-day mortality when treated by female surgeons.

“Policy makers need to combat prejudice against women in surgical careers, particularly in obstetrics and gynecology, so that women no longer experience conscious or unconscious barriers or difficulties in their professional choices, training, and relationships with colleagues or patients,” study corresponding author Loïc Sentilhes, MD, PhD, of Bordeaux University Hospital, said in an interview.

Facing such barriers, women may doubt their ability to be surgeons, their legitimacy as surgeons, and may not consider this type of career, he continued. “Moreover a teacher may not be as involved in teaching young female surgeons as young male surgeons, or the doctor-patient relationship may be more complicated in the event of complications if the patient thinks that a female surgeon has less competence than a male surgeon.”

The analysis drew on data from the Tranexamic Acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery 2 trial, a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study conducted from March 2018 through January 2020 in mothers from 27 French maternity hospitals.

Eligible participants had a cesarean delivery before or during labor at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary endpoint was the incidence of a composite maternal morbidity variable, and the secondary endpoint was the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, defined by a calculated estimated blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL or transfusion by day 2.

Among the 4,244 women included, male surgeons performed 943 cesarean deliveries (22.2%) and female surgeons performed 3,301 (77.8%). The percentage who were attending obstetricians was higher for men at 441 of 929 (47.5%) than women at 687 of 3,239 (21.2%).

The observed risk of maternal morbidity did not differ between male and female surgeons: 119 of 837 (14.2%) vs. 476 of 2,928 (16.3%), for an adjusted risk ratio (aRR) of 0.92 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.77-1.13). Interaction between surgeon gender and level of experience with the risk of maternal morbidity was not statistically significant; nor did the groups differ specifically by risk for postpartum hemorrhage: aRR, 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85-1.13).

Despite the longstanding stereotype that men perform surgery better than women, and the traditional preponderance of male surgeons, the authors noted, postoperative morbidity and mortality may be lower after various surgeries performed by women.

The TRAAP2 trial

In an accompanying editorial, Amanda Fader, MD, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, and colleagues caution that the French study’s methodology may not fully account for the complex intersection of surgeon volume, experience, gender, clinical decision-making skills, and patient-level and clinical factors affecting outcomes.

That said, appraising surgical outcomes based on gender may be an essential step toward reducing implicit bias and dispelling engendered perceptions regarding gender and technical proficiency, the commentators stated. “To definitively dispel archaic, gender-based notions about performance in clinical or surgical settings, efforts must go beyond peer-reviewed research,” Dr. Fader said in an interview. “Medical institutions and leaders of clinical departments must make concerted efforts to recruit, mentor, support, and promote women and persons of all genders in medicine – as well as confront any discriminatory perceptions and experiences concerning sex, race and ethnicity, sexual orientation, or economic class.”

This study was supported by the French Ministry of Health under its Clinical Research Hospital Program. Dr. Sentilhes reported financial relationships with Dilafor, Bayer, GlaxoSmithKline, Sigvaris, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. The editorial commentators disclosed no funding for their commentary or conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Vitiligo

THE COMPARISON

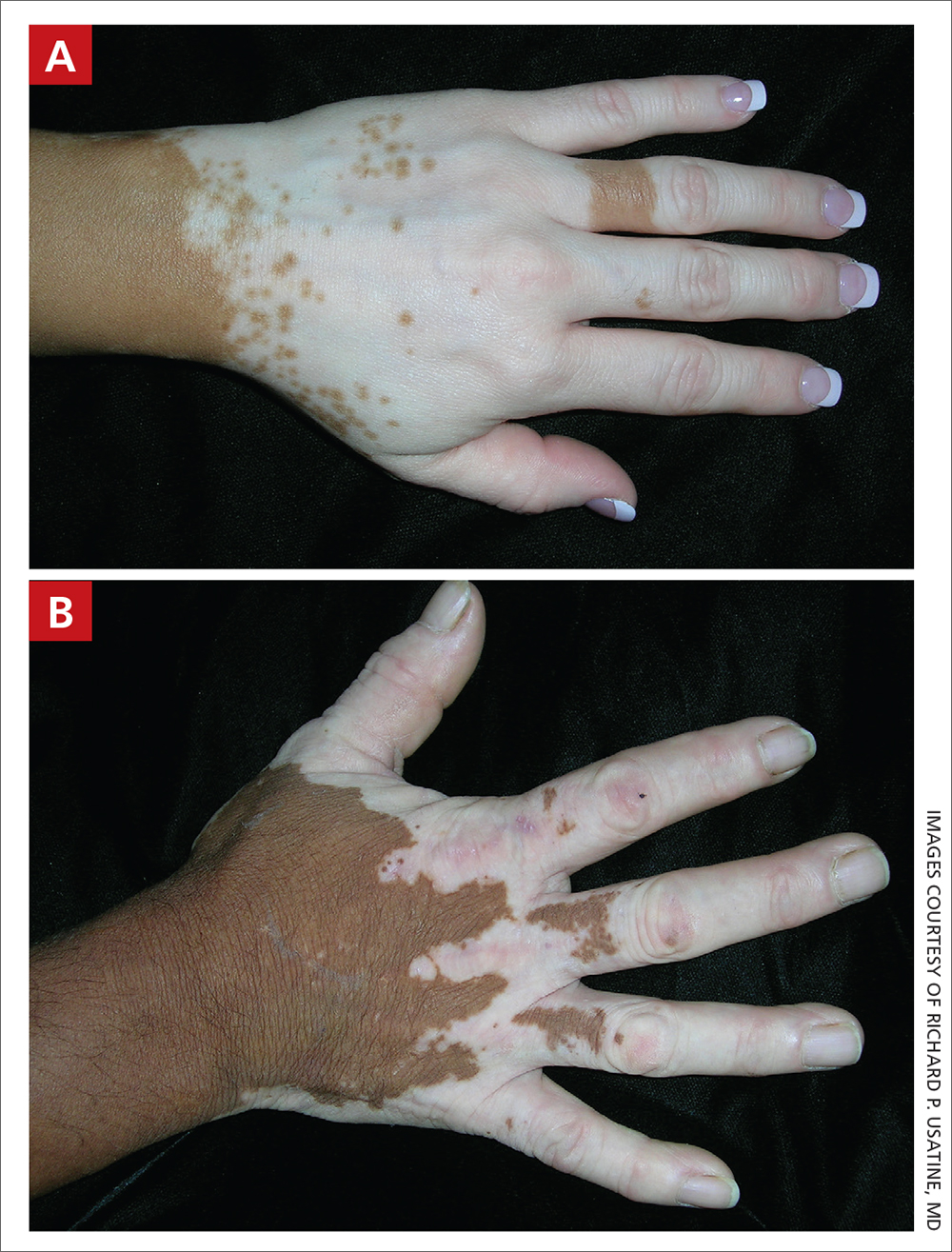

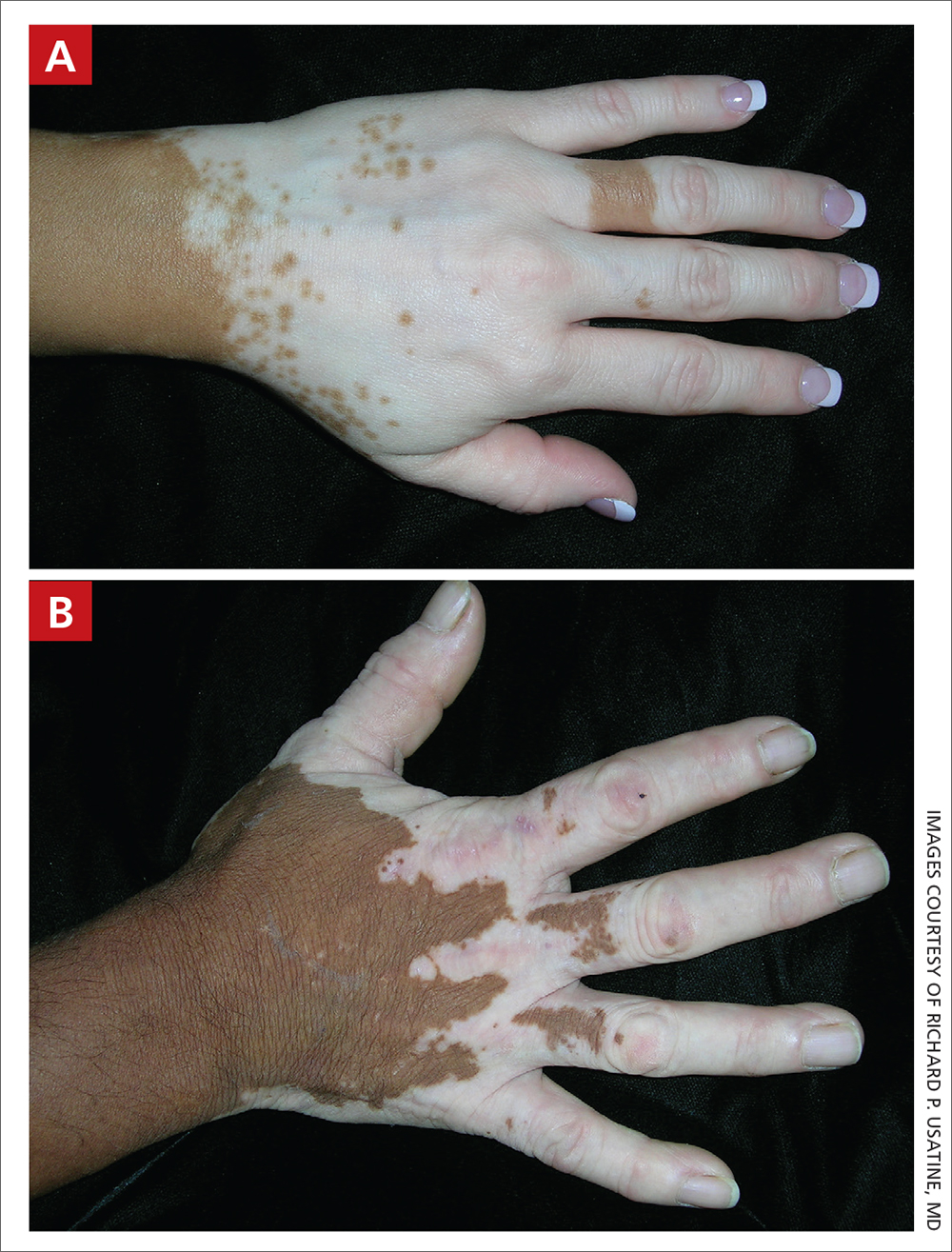

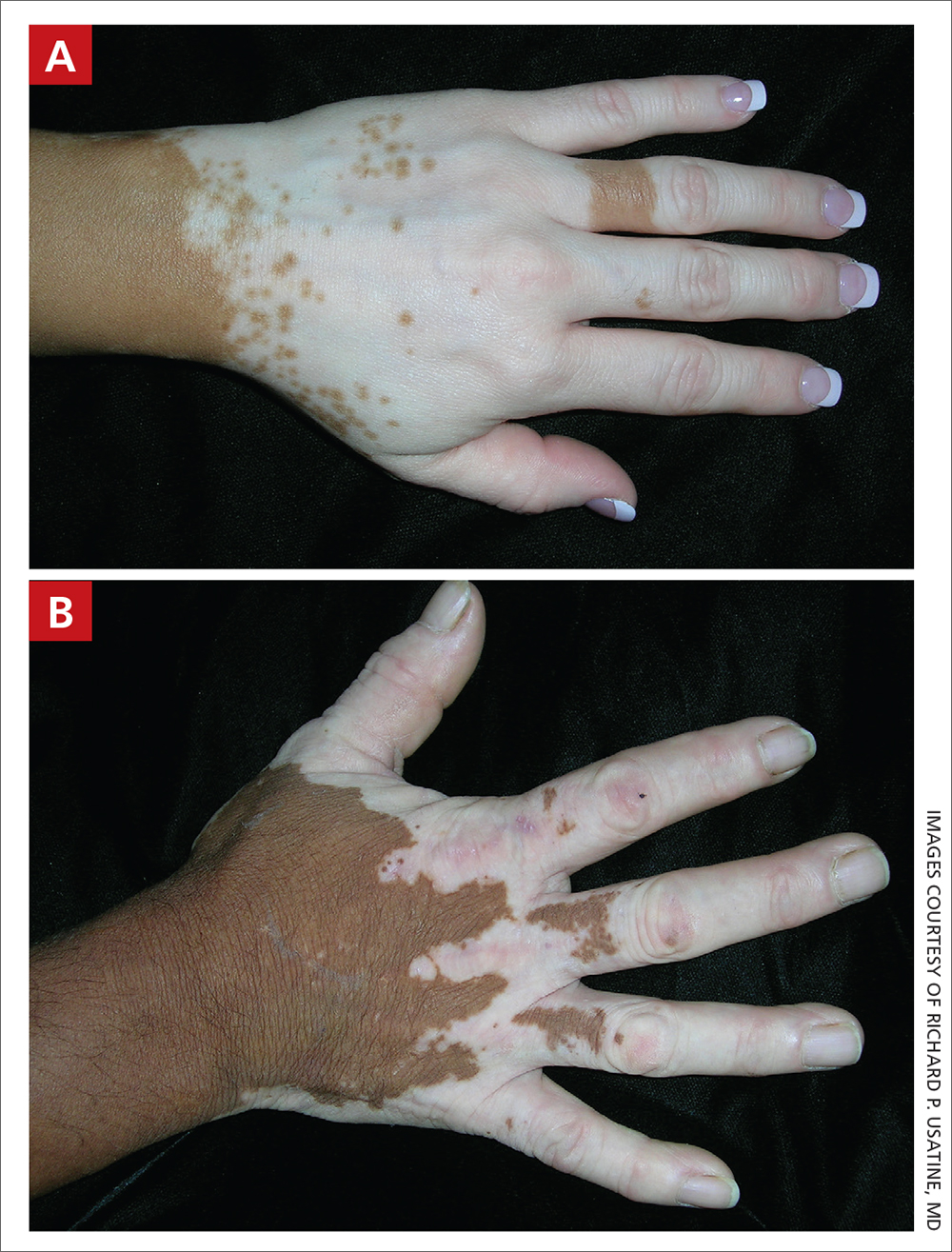

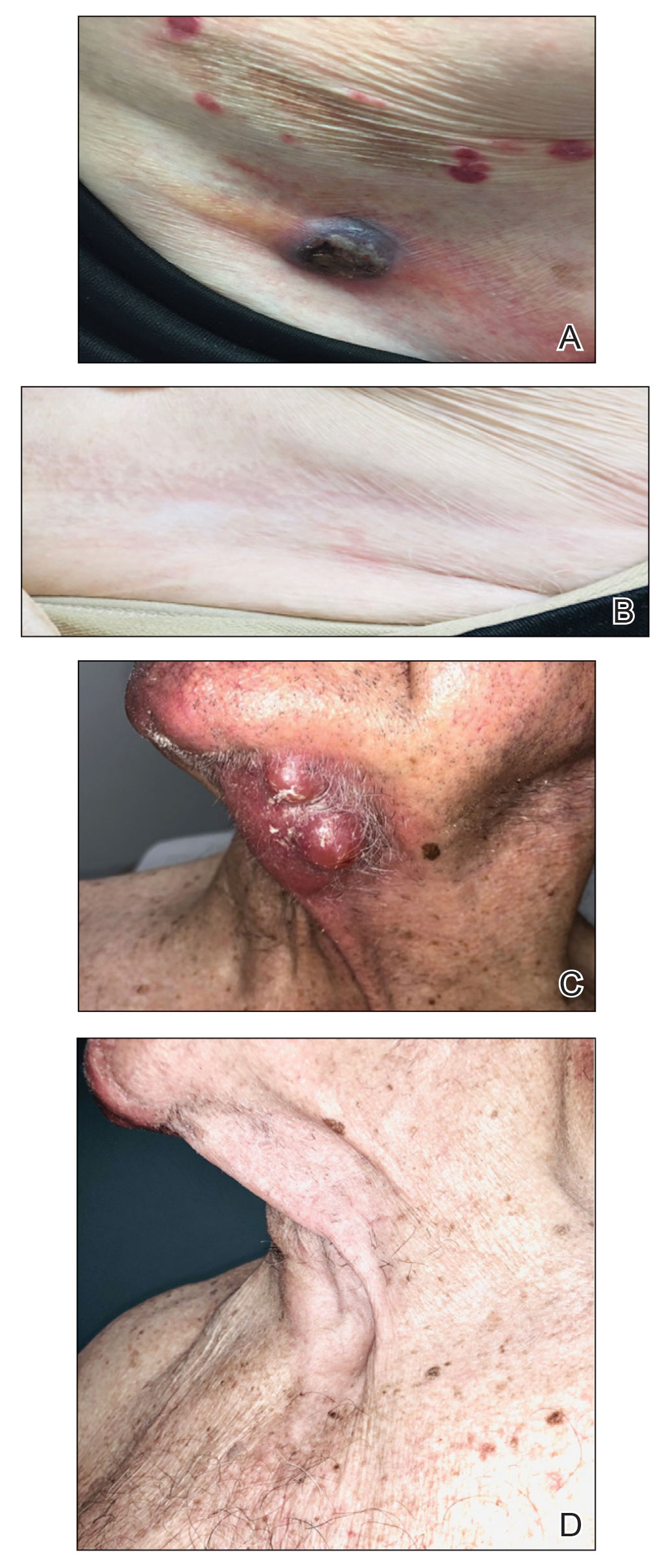

A Vitiligo in a young Hispanic female, which spared the area under a ring. The patient has spotty return of pigment on the hand after narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB) treatment.

B Vitiligo on the hand in a young Hispanic male.

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by areas of depigmented white patches on the skin due to the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis. Various theories on the pathogenesis of vitiligo exist; however, autoimmune destruction of melanocytes remains the leading hypothesis, followed by intrinsic defects in melanocytes.1

Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune diseases but is most frequently reported in conjunction with thyroid disorders.2

Epidemiology

Vitiligo affects approximately 1% of the US population and up to 8% worldwide.2 There is no difference in prevalence between races or genders. Females typically acquire the disease earlier than males. Onset may occur at any age, although about half of patients will have vitiligo by 20 years of age.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Bright white patches are characteristic of vitiligo. The patches typically are asymptomatic and often affect the hands (FIGURES A and B), perioral skin, feet, and scalp, as well as areas more vulnerable to friction and trauma, such as the elbows and knees.2 Trichrome lesions—consisting of varying zones of white (depigmented), lighter brown (hypopigmented), and normal skin—are most commonly seen in individuals with darker skin. Trichrome vitiligo is considered an actively progressing variant of vitiligo.2

An important distinction when making the diagnosis is evaluating for segmental vs nonsegmental vitiligo. Although nonsegmental vitiligo—the more common subtype—is characterized by symmetric distribution and a less predictable course, segmental vitiligo manifests in a localized and unilateral distribution, often avoiding extension past the midline. Segmental vitiligo typically manifests at a younger age and follows a more rapidly stabilizing course.3

Worth noting

Given that stark contrasts between pigmented and depigmented lesions are more prominent in darker skin tones, vitiligo can be more socially stigmatizing and psychologically devastating in these patients.4,5

Continue to: Treatment of vitiligo...

Treatment of vitiligo includes narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, excimer laser, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and surgical melanocyte transplantation.1 In July 2022, ruxolitinib cream 1.5% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nonsegmental vitiligo in patients ages 12 years and older.6,7 It is the only FDA-approved therapy for vitiligo. It is thought to work by inhibiting the Janus kinase–signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway.6 However, topical ruxolitinib is expensive, costing more than $2000 for 60 g.8

Health disparity highlight

A 2021 study reviewing the coverage policies of 15 commercial health care insurance companies, 50 BlueCross BlueShield plans, Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs plans found inequities in the insurance coverage patterns for therapies used to treat vitiligo. There were 2 commonly cited reasons for denying coverage for therapies: vitiligo was considered cosmetic and therapies were not FDA approved.7 In comparison, NB-UVB light phototherapy for psoriasis is not considered cosmetic and has a much higher insurance coverage rate.9,10 The out-of-pocket cost for a patient to purchase their own NB-UVB light phototherapy is more than $5000.11 Not all patients of color are economically disadvantaged, but in the United States, Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of poverty (19% and 17%, respectively) compared to their White counterparts (8%).12

Final thoughts

FDA approval of new drugs or new treatment indications comes after years of research discovery and large-scale trials. This pursuit of new discovery, however, is uneven. Vitiligo has historically been understudied and underfunded for research; this is common among several conditions adversely affecting people of color in the United States.13

1. Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi: 10.1016/j.det. 2016.11.014

2. Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061

3. van Geel N, Speeckaert R. Segmental vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:145-150. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2016.11.005

4. Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005

5. Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021; 22:757-774. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00631-6

6. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 19, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical- treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged- 12-and-older

7. Blundell A, Sachar M, Gabel CK, et al. The scope of health insurance coverage of vitiligo treatments in the United States: implications for health care outcomes and disparities in children of color. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(suppl 2):79-85. doi: 10.1111/ pde.14714

8. Opzelura prices, coupons, and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com. Accessed January 10, 2023. www.drugs.com/priceguide/opzelura

9. Bhutani T, Liao W. A practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7:31-35.

10. Castro Porto Silva Lopes F, Ahmed A. Insurance coverage for phototherapy for vitiligo in comparison to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine. 2022;6:217-224. doi: 10.25251/skin.6.3.6

11. Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Home phototherapy for patients with vitiligo: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:451-459. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S185798

12. Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau. September 14, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

13. Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003263.pub4

THE COMPARISON

A Vitiligo in a young Hispanic female, which spared the area under a ring. The patient has spotty return of pigment on the hand after narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB) treatment.

B Vitiligo on the hand in a young Hispanic male.

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by areas of depigmented white patches on the skin due to the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis. Various theories on the pathogenesis of vitiligo exist; however, autoimmune destruction of melanocytes remains the leading hypothesis, followed by intrinsic defects in melanocytes.1

Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune diseases but is most frequently reported in conjunction with thyroid disorders.2

Epidemiology

Vitiligo affects approximately 1% of the US population and up to 8% worldwide.2 There is no difference in prevalence between races or genders. Females typically acquire the disease earlier than males. Onset may occur at any age, although about half of patients will have vitiligo by 20 years of age.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Bright white patches are characteristic of vitiligo. The patches typically are asymptomatic and often affect the hands (FIGURES A and B), perioral skin, feet, and scalp, as well as areas more vulnerable to friction and trauma, such as the elbows and knees.2 Trichrome lesions—consisting of varying zones of white (depigmented), lighter brown (hypopigmented), and normal skin—are most commonly seen in individuals with darker skin. Trichrome vitiligo is considered an actively progressing variant of vitiligo.2

An important distinction when making the diagnosis is evaluating for segmental vs nonsegmental vitiligo. Although nonsegmental vitiligo—the more common subtype—is characterized by symmetric distribution and a less predictable course, segmental vitiligo manifests in a localized and unilateral distribution, often avoiding extension past the midline. Segmental vitiligo typically manifests at a younger age and follows a more rapidly stabilizing course.3

Worth noting

Given that stark contrasts between pigmented and depigmented lesions are more prominent in darker skin tones, vitiligo can be more socially stigmatizing and psychologically devastating in these patients.4,5

Continue to: Treatment of vitiligo...

Treatment of vitiligo includes narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, excimer laser, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and surgical melanocyte transplantation.1 In July 2022, ruxolitinib cream 1.5% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nonsegmental vitiligo in patients ages 12 years and older.6,7 It is the only FDA-approved therapy for vitiligo. It is thought to work by inhibiting the Janus kinase–signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway.6 However, topical ruxolitinib is expensive, costing more than $2000 for 60 g.8

Health disparity highlight

A 2021 study reviewing the coverage policies of 15 commercial health care insurance companies, 50 BlueCross BlueShield plans, Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs plans found inequities in the insurance coverage patterns for therapies used to treat vitiligo. There were 2 commonly cited reasons for denying coverage for therapies: vitiligo was considered cosmetic and therapies were not FDA approved.7 In comparison, NB-UVB light phototherapy for psoriasis is not considered cosmetic and has a much higher insurance coverage rate.9,10 The out-of-pocket cost for a patient to purchase their own NB-UVB light phototherapy is more than $5000.11 Not all patients of color are economically disadvantaged, but in the United States, Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of poverty (19% and 17%, respectively) compared to their White counterparts (8%).12

Final thoughts

FDA approval of new drugs or new treatment indications comes after years of research discovery and large-scale trials. This pursuit of new discovery, however, is uneven. Vitiligo has historically been understudied and underfunded for research; this is common among several conditions adversely affecting people of color in the United States.13

THE COMPARISON

A Vitiligo in a young Hispanic female, which spared the area under a ring. The patient has spotty return of pigment on the hand after narrowband ultraviolet B (UVB) treatment.

B Vitiligo on the hand in a young Hispanic male.

Vitiligo is a chronic autoimmune disorder characterized by areas of depigmented white patches on the skin due to the loss of melanocytes in the epidermis. Various theories on the pathogenesis of vitiligo exist; however, autoimmune destruction of melanocytes remains the leading hypothesis, followed by intrinsic defects in melanocytes.1

Vitiligo is associated with various autoimmune diseases but is most frequently reported in conjunction with thyroid disorders.2

Epidemiology

Vitiligo affects approximately 1% of the US population and up to 8% worldwide.2 There is no difference in prevalence between races or genders. Females typically acquire the disease earlier than males. Onset may occur at any age, although about half of patients will have vitiligo by 20 years of age.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Bright white patches are characteristic of vitiligo. The patches typically are asymptomatic and often affect the hands (FIGURES A and B), perioral skin, feet, and scalp, as well as areas more vulnerable to friction and trauma, such as the elbows and knees.2 Trichrome lesions—consisting of varying zones of white (depigmented), lighter brown (hypopigmented), and normal skin—are most commonly seen in individuals with darker skin. Trichrome vitiligo is considered an actively progressing variant of vitiligo.2

An important distinction when making the diagnosis is evaluating for segmental vs nonsegmental vitiligo. Although nonsegmental vitiligo—the more common subtype—is characterized by symmetric distribution and a less predictable course, segmental vitiligo manifests in a localized and unilateral distribution, often avoiding extension past the midline. Segmental vitiligo typically manifests at a younger age and follows a more rapidly stabilizing course.3

Worth noting

Given that stark contrasts between pigmented and depigmented lesions are more prominent in darker skin tones, vitiligo can be more socially stigmatizing and psychologically devastating in these patients.4,5

Continue to: Treatment of vitiligo...

Treatment of vitiligo includes narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) light phototherapy, excimer laser, topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus and pimecrolimus, and surgical melanocyte transplantation.1 In July 2022, ruxolitinib cream 1.5% was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for nonsegmental vitiligo in patients ages 12 years and older.6,7 It is the only FDA-approved therapy for vitiligo. It is thought to work by inhibiting the Janus kinase–signal transducers and activators of the transcription pathway.6 However, topical ruxolitinib is expensive, costing more than $2000 for 60 g.8

Health disparity highlight

A 2021 study reviewing the coverage policies of 15 commercial health care insurance companies, 50 BlueCross BlueShield plans, Medicaid, Medicare, and Veterans Affairs plans found inequities in the insurance coverage patterns for therapies used to treat vitiligo. There were 2 commonly cited reasons for denying coverage for therapies: vitiligo was considered cosmetic and therapies were not FDA approved.7 In comparison, NB-UVB light phototherapy for psoriasis is not considered cosmetic and has a much higher insurance coverage rate.9,10 The out-of-pocket cost for a patient to purchase their own NB-UVB light phototherapy is more than $5000.11 Not all patients of color are economically disadvantaged, but in the United States, Black and Hispanic populations experience disproportionately higher rates of poverty (19% and 17%, respectively) compared to their White counterparts (8%).12

Final thoughts

FDA approval of new drugs or new treatment indications comes after years of research discovery and large-scale trials. This pursuit of new discovery, however, is uneven. Vitiligo has historically been understudied and underfunded for research; this is common among several conditions adversely affecting people of color in the United States.13

1. Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi: 10.1016/j.det. 2016.11.014

2. Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061

3. van Geel N, Speeckaert R. Segmental vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:145-150. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2016.11.005

4. Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005

5. Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021; 22:757-774. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00631-6

6. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 19, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical- treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged- 12-and-older

7. Blundell A, Sachar M, Gabel CK, et al. The scope of health insurance coverage of vitiligo treatments in the United States: implications for health care outcomes and disparities in children of color. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(suppl 2):79-85. doi: 10.1111/ pde.14714

8. Opzelura prices, coupons, and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com. Accessed January 10, 2023. www.drugs.com/priceguide/opzelura

9. Bhutani T, Liao W. A practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7:31-35.

10. Castro Porto Silva Lopes F, Ahmed A. Insurance coverage for phototherapy for vitiligo in comparison to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine. 2022;6:217-224. doi: 10.25251/skin.6.3.6

11. Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Home phototherapy for patients with vitiligo: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:451-459. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S185798

12. Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau. September 14, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

13. Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003263.pub4

1. Rashighi M, Harris JE. Vitiligo pathogenesis and emerging treatments. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:257-265. doi: 10.1016/j.det. 2016.11.014

2. Alikhan A, Felsten LM, Daly M, et al. Vitiligo: a comprehensive overview part I. introduction, epidemiology, quality of life, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, associations, histopathology, etiology, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:473-491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.061

3. van Geel N, Speeckaert R. Segmental vitiligo. Dermatol Clin. 2017; 35:145-150. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2016.11.005

4. Grimes PE, Miller MM. Vitiligo: patient stories, self-esteem, and the psychological burden of disease. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:32-37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.005

5. Ezzedine K, Eleftheriadou V, Jones H, et al. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo: a systematic literature review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021; 22:757-774. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00631-6

6. FDA approves topical treatment addressing repigmentation in vitiligo in patients aged 12 and older. News release. US Food and Drug Administration; July 19, 2022. Accessed December 27, 2022. www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/fda-approves-topical- treatment-addressing-repigmentation-vitiligo-patients-aged- 12-and-older

7. Blundell A, Sachar M, Gabel CK, et al. The scope of health insurance coverage of vitiligo treatments in the United States: implications for health care outcomes and disparities in children of color. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(suppl 2):79-85. doi: 10.1111/ pde.14714

8. Opzelura prices, coupons, and patient assistance programs. Drugs.com. Accessed January 10, 2023. www.drugs.com/priceguide/opzelura

9. Bhutani T, Liao W. A practical approach to home UVB phototherapy for the treatment of generalized psoriasis. Pract Dermatol. 2010;7:31-35.

10. Castro Porto Silva Lopes F, Ahmed A. Insurance coverage for phototherapy for vitiligo in comparison to psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine. 2022;6:217-224. doi: 10.25251/skin.6.3.6

11. Smith MP, Ly K, Thibodeaux Q, et al. Home phototherapy for patients with vitiligo: challenges and solutions. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:451-459. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S185798

12. Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. US Census Bureau. September 14, 2021. Accessed December 27, 2022. www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

13. Whitton ME, Pinart M, Batchelor J, et al. Interventions for vitiligo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD003263. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003263.pub4

FDA wants annual COVID boosters, just like annual flu shots

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is suggesting a single annual shot. The formulation would be selected in June targeting the most threatening COVID-19 strains, and then people could get a shot in the fall when people begin spending more time indoors and exposure increases.

Some people, such as those who are older or immunocompromised, may need more than one dose.

A national advisory committee is expected to vote on the proposal at a meeting Jan. 26.

People in the United States have been much less likely to get an updated COVID-19 booster shot, compared with widespread uptake of the primary vaccine series. In its proposal, the FDA indicated it hoped a single annual shot would overcome challenges created by the complexity of the process – both in messaging and administration – attributed to that low booster rate. Nine in 10 people age 12 or older got the primary vaccine series in the United States, but only 15% got the latest booster shot for COVID-19.

About half of children and adults in the U.S. get an annual flu shot, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The FDA also wants to move to a single COVID-19 vaccine formulation that would be used for primary vaccine series and for booster shots.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are trending downward, according to the data tracker from the New York Times. Cases are down 28%, with 47,290 tallied daily. Hospitalizations are down 22%, with 37,474 daily. Deaths are down 4%, with an average of 489 per day as of Jan. 22.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is suggesting a single annual shot. The formulation would be selected in June targeting the most threatening COVID-19 strains, and then people could get a shot in the fall when people begin spending more time indoors and exposure increases.

Some people, such as those who are older or immunocompromised, may need more than one dose.

A national advisory committee is expected to vote on the proposal at a meeting Jan. 26.

People in the United States have been much less likely to get an updated COVID-19 booster shot, compared with widespread uptake of the primary vaccine series. In its proposal, the FDA indicated it hoped a single annual shot would overcome challenges created by the complexity of the process – both in messaging and administration – attributed to that low booster rate. Nine in 10 people age 12 or older got the primary vaccine series in the United States, but only 15% got the latest booster shot for COVID-19.

About half of children and adults in the U.S. get an annual flu shot, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The FDA also wants to move to a single COVID-19 vaccine formulation that would be used for primary vaccine series and for booster shots.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are trending downward, according to the data tracker from the New York Times. Cases are down 28%, with 47,290 tallied daily. Hospitalizations are down 22%, with 37,474 daily. Deaths are down 4%, with an average of 489 per day as of Jan. 22.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is suggesting a single annual shot. The formulation would be selected in June targeting the most threatening COVID-19 strains, and then people could get a shot in the fall when people begin spending more time indoors and exposure increases.

Some people, such as those who are older or immunocompromised, may need more than one dose.

A national advisory committee is expected to vote on the proposal at a meeting Jan. 26.

People in the United States have been much less likely to get an updated COVID-19 booster shot, compared with widespread uptake of the primary vaccine series. In its proposal, the FDA indicated it hoped a single annual shot would overcome challenges created by the complexity of the process – both in messaging and administration – attributed to that low booster rate. Nine in 10 people age 12 or older got the primary vaccine series in the United States, but only 15% got the latest booster shot for COVID-19.

About half of children and adults in the U.S. get an annual flu shot, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

The FDA also wants to move to a single COVID-19 vaccine formulation that would be used for primary vaccine series and for booster shots.

COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths are trending downward, according to the data tracker from the New York Times. Cases are down 28%, with 47,290 tallied daily. Hospitalizations are down 22%, with 37,474 daily. Deaths are down 4%, with an average of 489 per day as of Jan. 22.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMD.com.

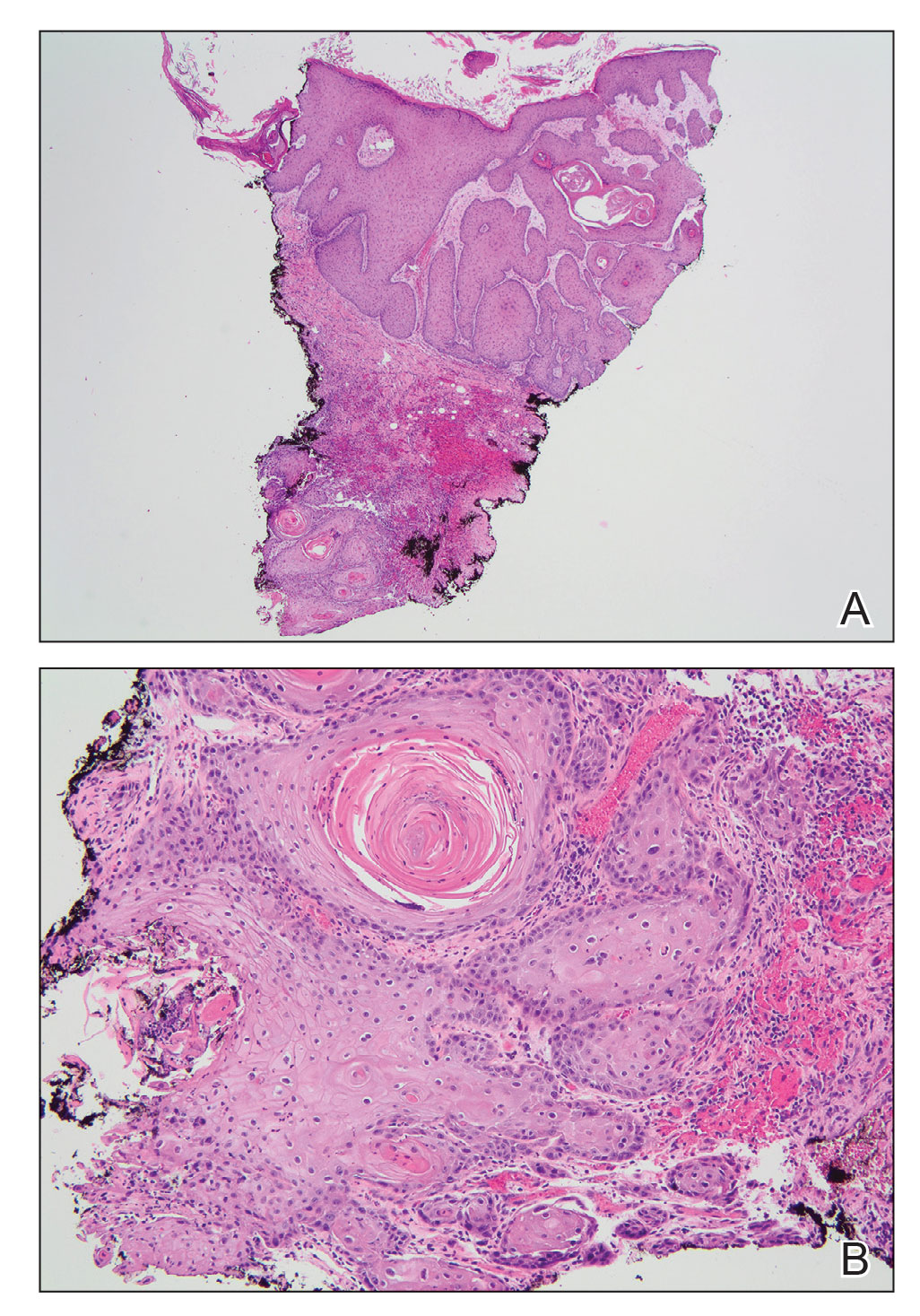

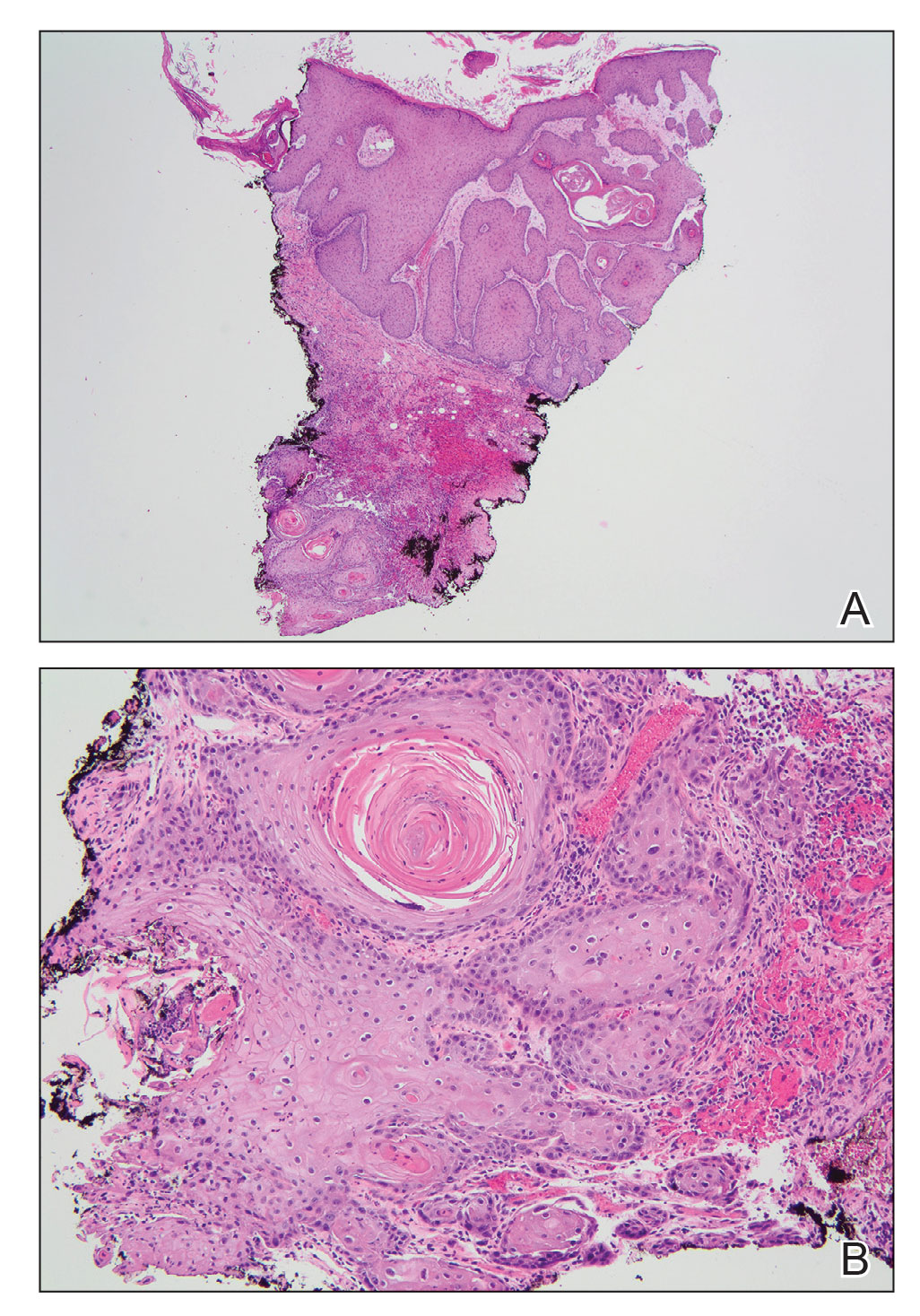

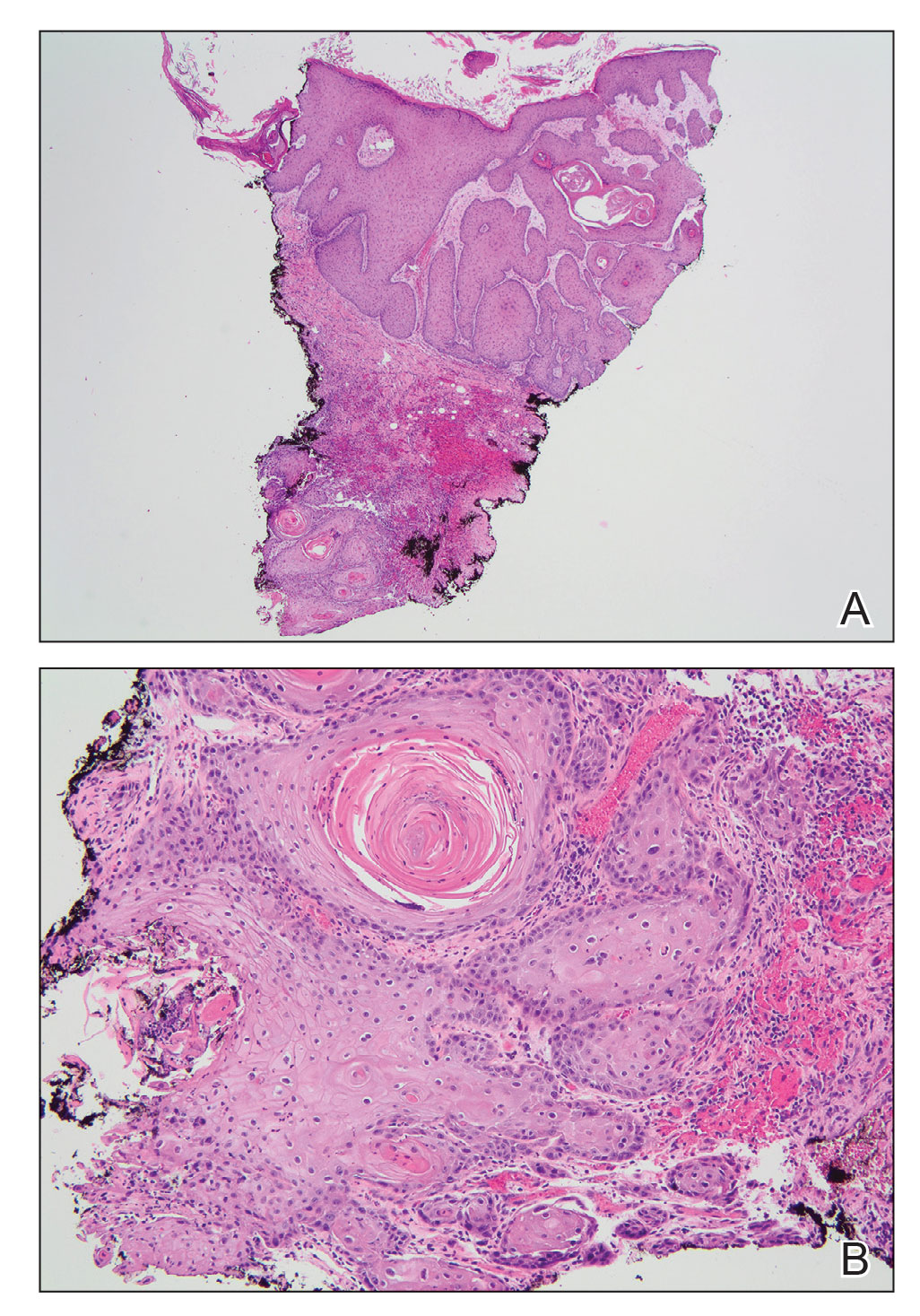

Dissociating Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus From Internal Malignancy: A Single-Center Retrospective Study

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP), or Pinkus tumor, is a rare tumor with a presentation similar to benign neoplasms such as acrochordons and seborrheic keratoses. Classically, FeP presents as a nontender, solitary, flesh-colored, firm, dome-shaped papule or plaque with a predilection for the lumbosacral region rather than sun-exposed areas. This tumor typically develops in fair-skinned older adults, more often in females.1

The association between cutaneous lesions and internal malignancies is well known to include dermatoses such as erythema repens in patients with lung cancer, or tripe palms and acanthosis nigricans in patients with gastrointestinal malignancy. Outside of paraneoplastic presentations, many syndromes have unique constellations of clinical findings that require the clinician to investigate for internal malignancy. Cancer-associated genodermatoses such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé, neurofibromatosis, and Cowden syndrome have key findings to alert the provider of potential internal malignancies.2 Given the rarity and relative novelty of FeP, few studies have been performed that evaluate for an association with internal malignancies.

There potentially is a common pathophysiologic mechanism between FeP and other benign and malignant tumors. Some have noted a possible common embryonic origin, such as Merkel cells, and even a common gene mutation involving tumor protein p53 or PTCH1 gene.3,4 Carcinoembryonic antigen is a glycoprotein often found in association with gastrointestinal tract tumors and also is elevated in some cases of FeP.5 A single-center retrospective study performed by Longo et al3 demonstrated an association between FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy by calculating a percentage of those with FeP who also had gastrointestinal tract tumors. Moreover, they noted that FeP preceded gastrointestinal tract tumors by up to 1 to 2 years. Using the results of this study, they suggested that a similar pathogenesis underlies the association between FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy, but a shared pathogenesis has not yet been elucidated.3

With a transition to preventive medicine and age-adjusted malignancy screening in the US medical community, the findings of FeP as a marker of gastrointestinal tract tumors could alter current recommendations of routine skin examinations and colorectal cancer screening. This study investigates the association between FeP and internal malignancy, especially gastrointestinal tract tumors.

Methods

Patient Selection—A single-center, retrospective, case-control study was designed to investigate an association between FeP and internal malignancy. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Naval Medical Center San Diego, California, in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. A medical record review was initiated using the Department of Defense (DoD) electronic health record to identify patients with a history of FeP. The query used a natural language search for patients who had received a histopathology report that included Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, Pinkus, or Pinkus tumor within the diagnosis or comment section for pathology specimens processed at our institution (Naval Medical Center San Diego). A total of 45 patients evaluated at Naval Medical Center San Diego had biopsy specimens that met inclusion criteria. Only 42 electronic medical records were available to review between January 1, 2003, and March 1, 2020. Three patients were excluded from the study for absent or incomplete medical records.

Study Procedures—Data extracted by researchers were analyzed for statistical significance. All available data in current electronic health records prior to the FeP diagnosis until March 1, 2020, was reviewed for other documented malignancy or colonoscopy data. Data extracted included age, sex, date of diagnosis of FeP, location of FeP, social history, and medical and surgical history to identify prior malignancy. Colorectal cancer screening results were drawn from original reports, gastrointestinal clinic notes, biopsy results, and/or primary care provider documentation of colonoscopy results. If the exact date of internal tumor diagnosis could not be determined but the year was known, the value “July, year” was utilized as the diagnosis date.

Statistical Analysis—Data were reviewed for validity, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. Graphical visualization assisted in reviewing the distribution of the data in relation to the internal tumors. The Fisher exact test was performed to test for associations, while continuous variables were assessed using the Student t test or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Analysis was conducted with StataCorp. 2017 Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 (StataCorp LLC). Significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Patient Demographics—Of the 42 patients with FeP included in this study, 28 (66.7%) were male and 14 (33.3%) were female. The overall mean age at FeP diagnosis was 56.83 years. The mean age (SD) at FeP diagnosis for males was 59.21 (19.00) years and 52.07 (21.61) for females (P=.2792)(Table 1). Other pertinent medical history, including alcohol and tobacco use, obesity, and diabetes mellitus, is included in Table 1.

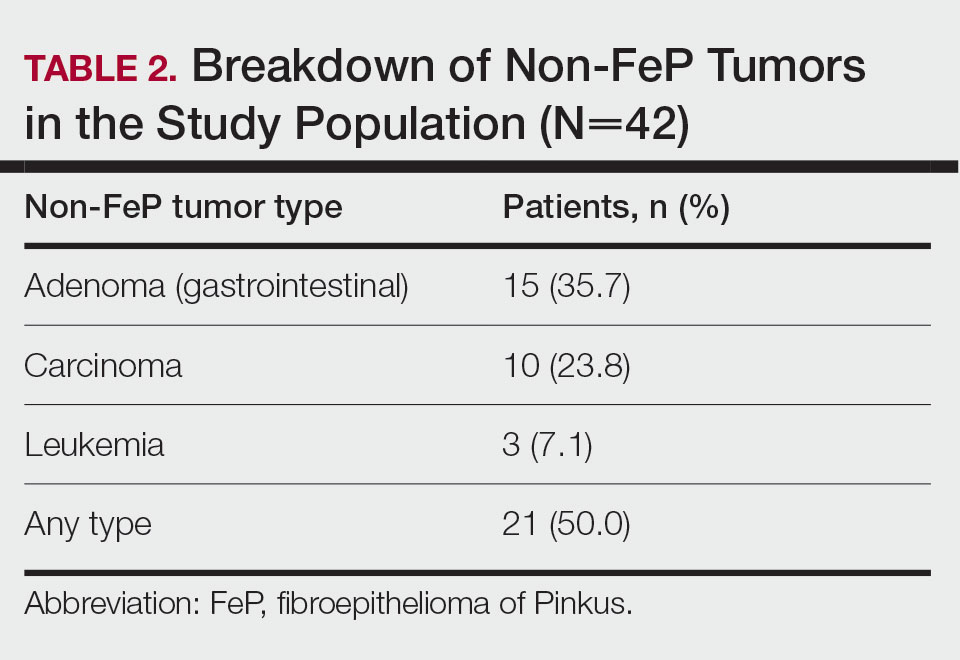

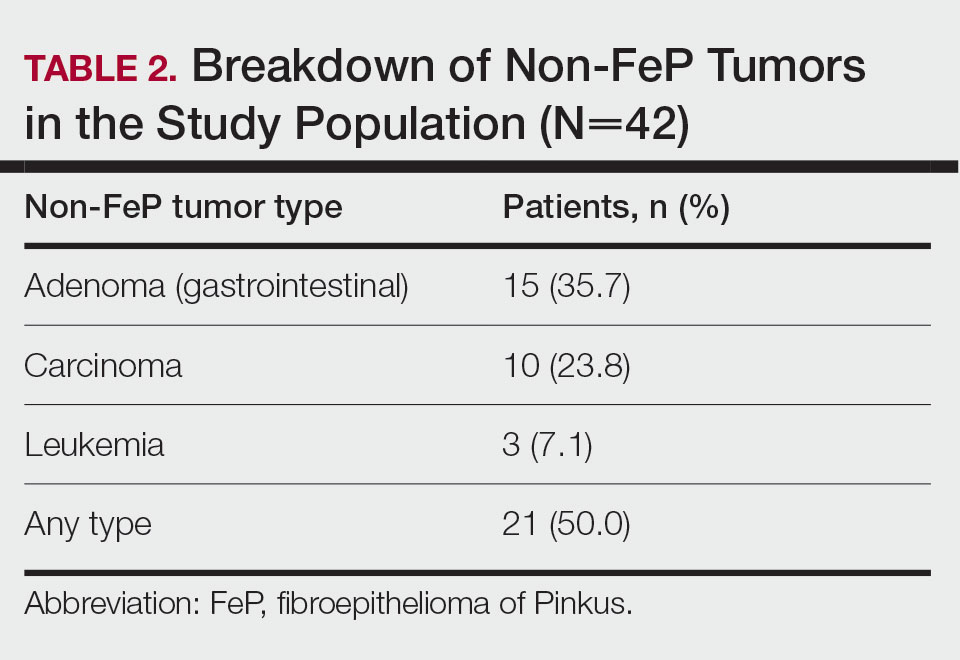

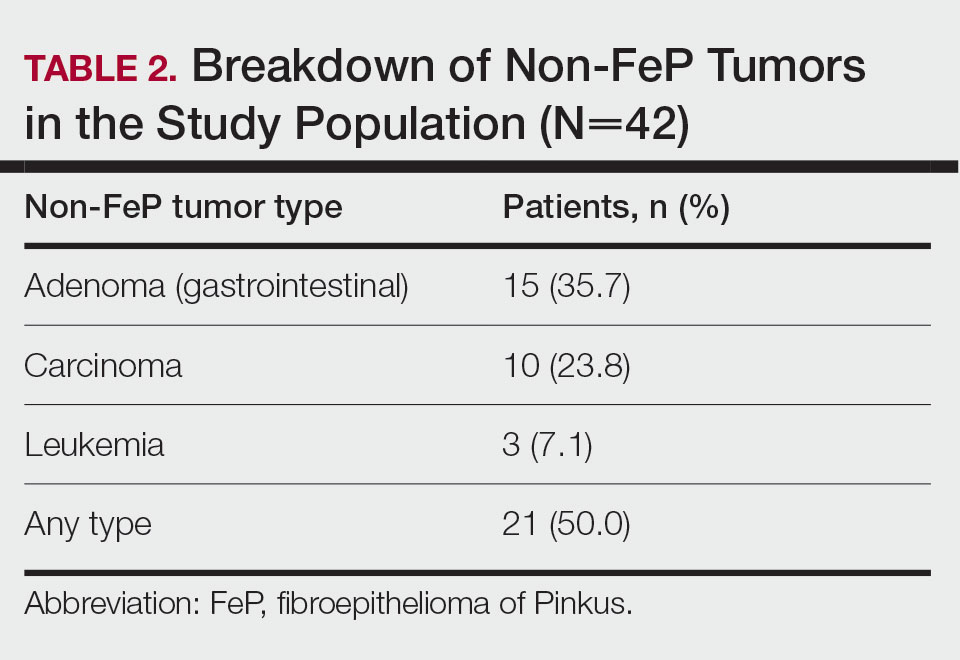

Characterization of Tumors—The classification of the number of patients with any other nonskin neoplasm is presented in Table 2. Fifteen (35.7%) patients had 1 or more gastrointestinal tubular adenomas. Three patients were found to have colorectal adenocarcinoma. Karsenti et al6 published a large study of colonic adenoma detection rates in the World Journal of Gastroenterology stratified by age and found that the incidence of adenoma for those aged 55 to 59 years was 28.3% vs 35.7% in our study (P=.2978 [Fisher exact test]).

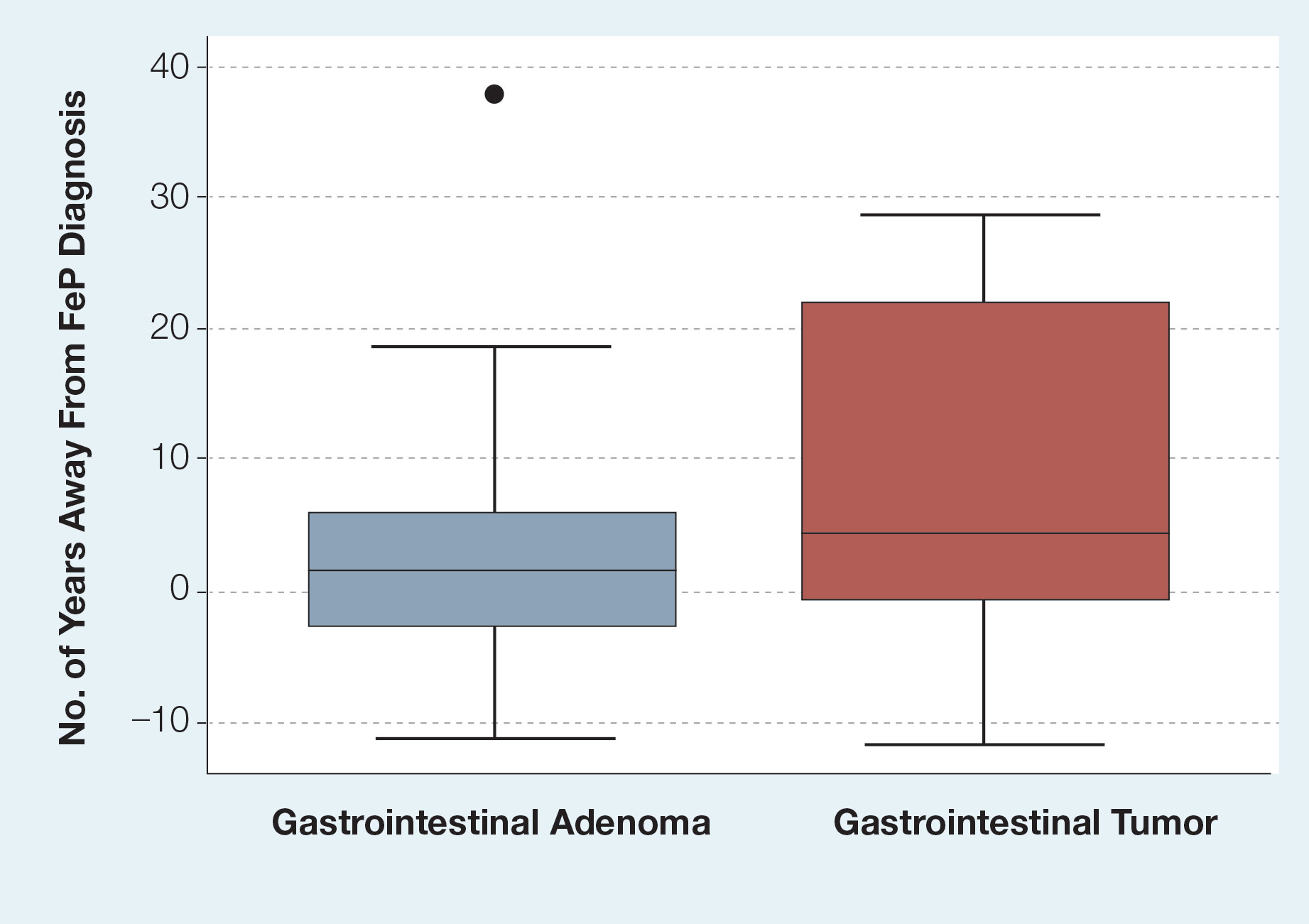

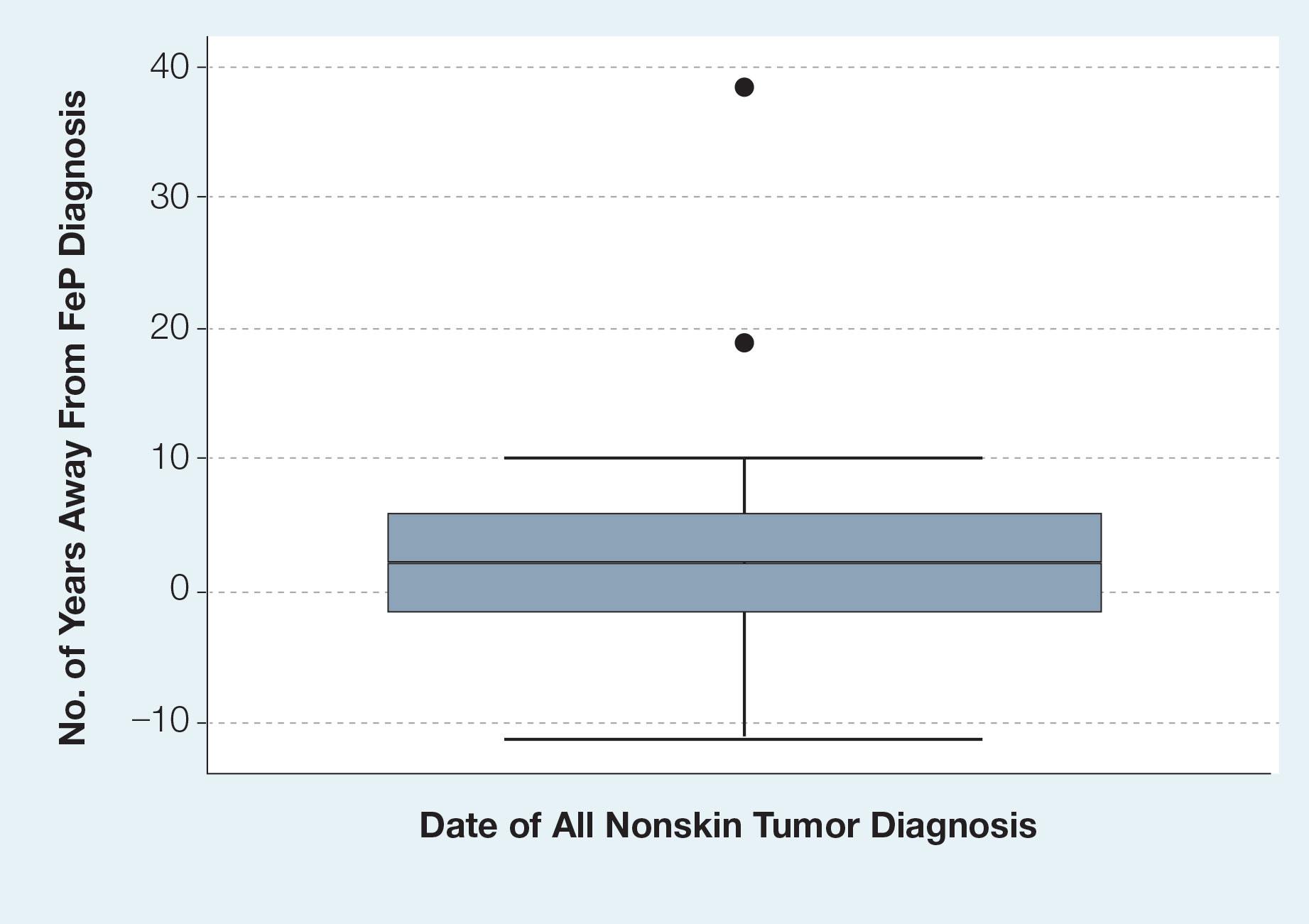

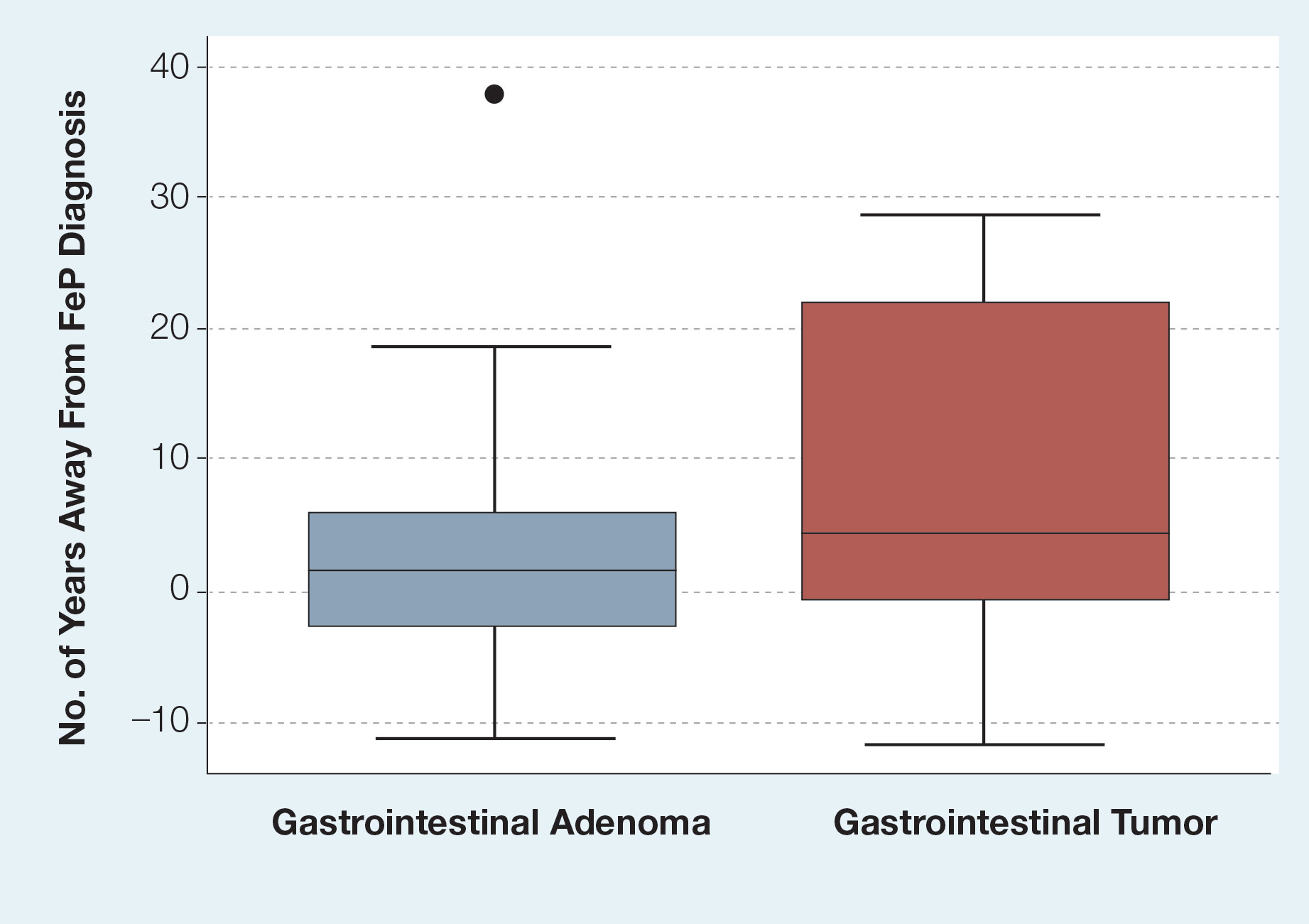

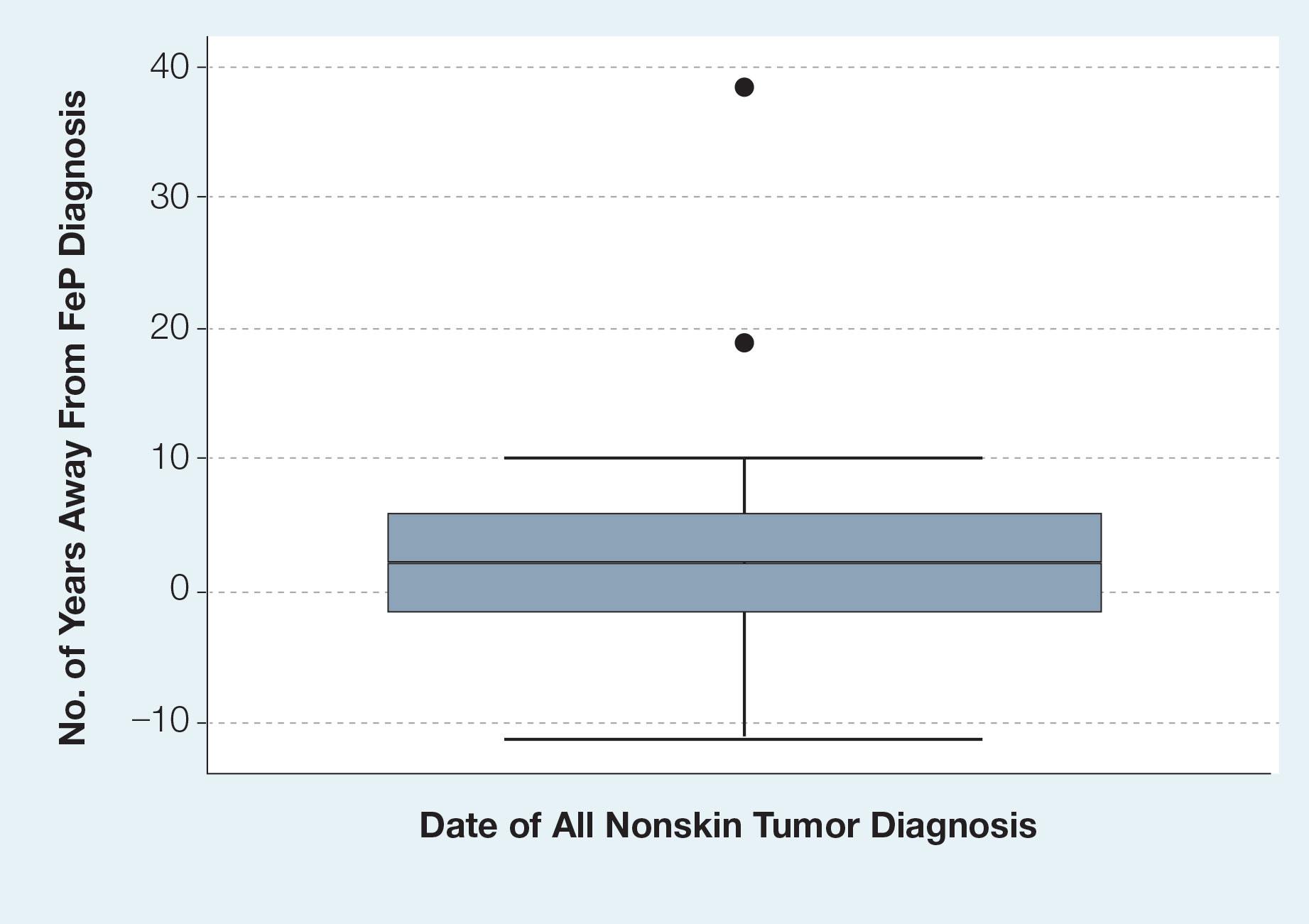

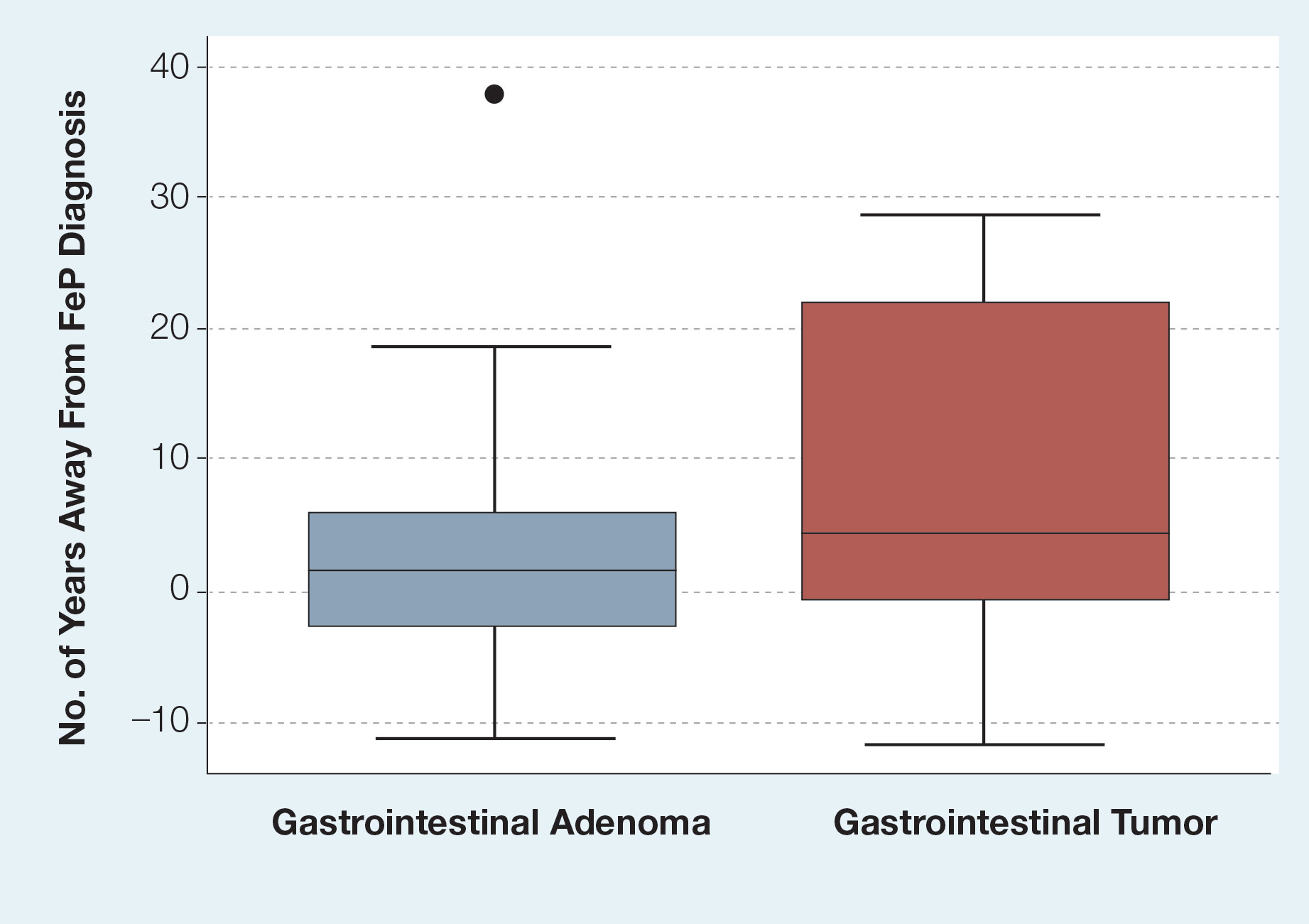

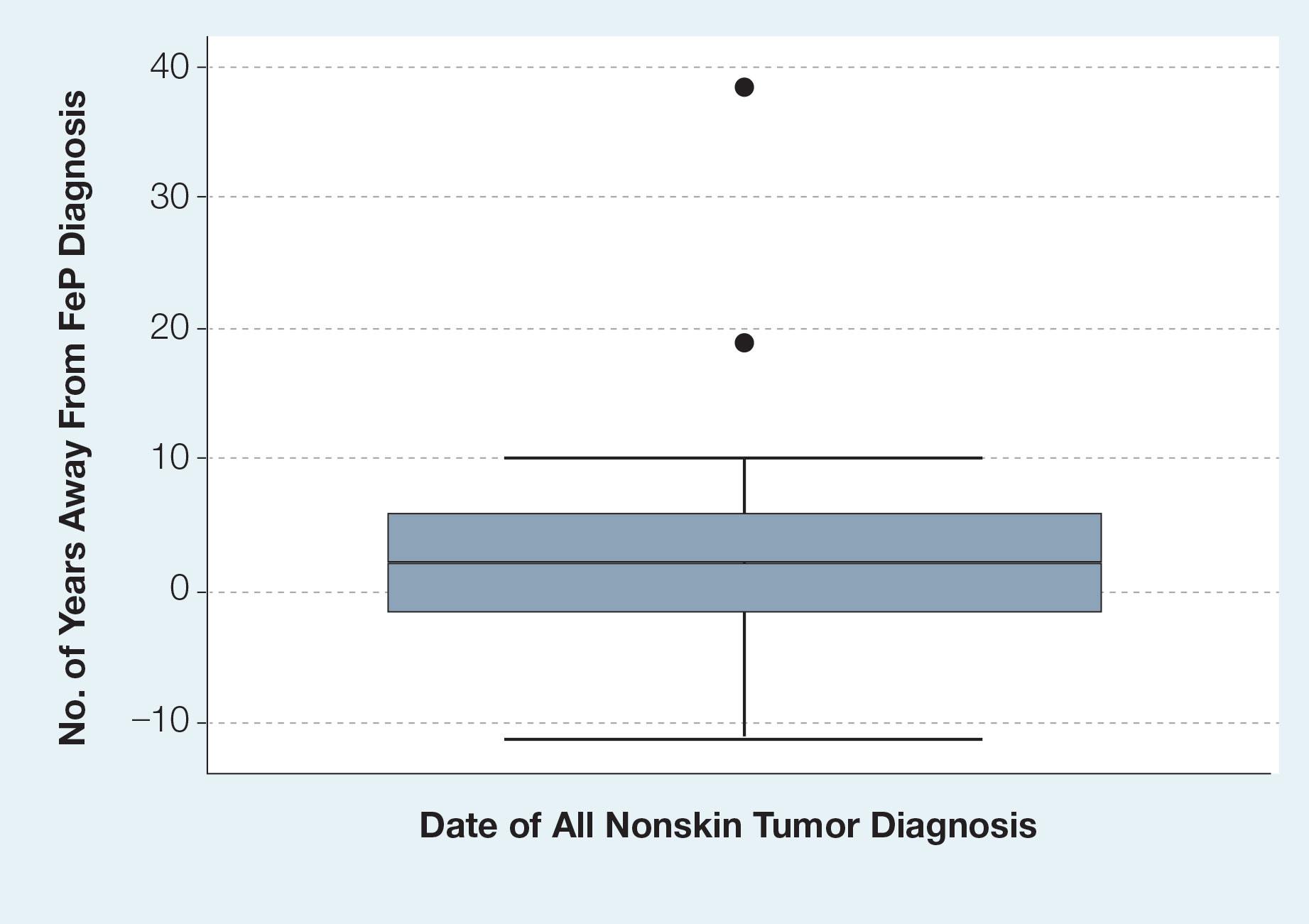

Given the number of gastrointestinal tract tumors detected, most of which were found during routine surveillance, and a prior study6 suggesting a relationship between FeP and gastrointestinal tract tumors, we analyzed the temporal relationship between the date of gastrointestinal tract tumor diagnosis and the date of FeP diagnosis to assess if gastrointestinal tract tumor or FeP might predict the onset of the other (Figure 1). By assigning a temporal category to each gastrointestinal tract tumor as occurring either before or after the FeP diagnosis by 0 to 3 years, 3 to 10 years, 10 to 15 years, and 15 or more years, the box plot in Figure 1 shows that gastrointestinal adenoma development had no significant temporal relationship to the presence of FeP, excluding any outliers (shown as dots). Additionally, in Figure 1, the same concept was applied to assess the relationship between the dates of all gastrointestinal tract tumors—benign, precancerous, or malignant—and the date of FeP diagnosis, which again showed that FeP and gastrointestinal tract tumors did not predict the onset of the other. Figure 2 showed the same for all nonskin tumor diagnoses and again demonstrated that FeP and all other nondermatologic tumors did not predict the onset of the other.

Comment

Malignancy Potential—The malignant potential of FeP—characterized as a trichoblastoma (an adnexal tumor) or a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) variant—has been documented.1 Haddock and Cohen1 noted that FeP can be considered as an intermediate variant between BCC and trichoblastomas. Furthermore, they questioned the relevance of differentiating FeP as benign or malignant.1 There are additional elements of FeP that currently are unknown, which can be partially attributed to its rarity. If we can clarify a more accurate pathogenic model of FeP, then common mutational pathways with other malignancies may be identified.

Screening for Malignancy in FeP Patients—Until recently, FeP has not been demonstrated to be associated with other cancers or to have increased metastatic potential.1 In a 1985 case series of 2 patients, FeP was found to be specifically overlying infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. After a unilateral mastectomy, examination of the overlying skin of the breast showed a solitary, lightly pigmented nodule, which was identified as an FeP after histopathologic evaluation.7 There have been limited investigations of whether FeP is simply a solitary tumor or a harbinger for other malignancies, despite a study by Longo et al3 that attempted to establish this temporal relationship. They recommended that patients with FeP be clinically evaluated and screened for gastrointestinal tract tumors.3 Based on these recommendations, textbooks for dermatopathology now highlight the possible correlation of FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy,8 which may lead to earlier and unwarranted screening.

Comparison to the General Population—Although our analysis showed a portion of patients with FeP have gastrointestinal tract tumors, we do not detect a significant difference from the general population. The average age at the time of FeP diagnosis in our study was 56.83 years compared with the average age of 64.0 years by Longo et al,3 where they found an association with gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors. As the rate of gastrointestinal adenoma and malignancy increases with age, the older population in the study by Longo et al3 may have developed colorectal cancer independent of FeP development. However, the rate of gastrointestinal or other malignancies in their study was substantially higher than that of the general population. The Longo et al3 study found that 22 of 49 patients developed nondermatologic malignancies within 2 years of FeP diagnosis. Additionally, no data were provided in the study regarding precancerous lesions.

In our study population, benign gastrointestinal tract tumors, specifically tubular adenomas, were noted in 35.7% of patients with FeP compared with 28.3% of the general population in the same age group reported by Karsenti et al.6 Although limited by our sample size, our study demonstrated that patients with FeP diagnosis showed no significant difference in age-stratified incidence of tubular adenoma compared with the general population (P=.2978). Figures 1 and 2 showed no obvious temporal relationship between the development of FeP and the diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumor—either precancerous or malignant lesions—suggesting that diagnosis of one does not indicate the presence of the other.

Relationship With Colonoscopy Results—By analyzing those patients with FeP who specifically had documented colonoscopy results, we did not find a correlation between FeP and gastrointestinal tubular adenoma or carcinoma at any time during the patients’ available records. Although some patients may have had undocumented colonoscopies performed outside the DoD medical system, most had evidence that these procedures were being performed by transcription into primary care provider notes, uploaded gastroenterologist clinical notes, or colonoscopy reports. It is unlikely a true colorectal or other malignancy would remain undocumented over years within the electronic medical record.

Study Limitations—Because of the nature of electronic medical records at multiple institutions, the quality and/or the quantity of medical documentation is not standardized across all patients. Not all pathology reports may include FeP as the primary diagnosis or description, as FeP may simply be reported as BCC. Despite thorough data extraction by physicians, we were limited to the data available within our electronic medical records. Colonoscopies and other specialty care often were performed by civilian providers. Documentation regarding where patients were referred for such procedures outside the DoD was not available unless reports were transmitted to the DoD or transcribed by primary care providers. Incomplete records may make it more difficult to identify and document the number and characteristics of patients’ tubular adenomas. Therefore, a complete review of civilian records was not possible, causing some patients’ medical records to be documented for a longer period of their lives than for others.

Conclusion

Given the discrepancies in our findings with the previous study,3 future investigations on FeP and associated tumors should focus on integrated health care systems with longitudinal data sets for all age-appropriate cancer screenings in a larger sample size. Another related study is needed to evaluate the pathophysiologic mechanisms of FeP development relative to known cancer lines.

- Haddock ES, Cohen PR. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus revisited. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:347-362.

- Ponti G, Pellacani G, Seidenari S, et al. Cancer-associated genodermatoses: skin neoplasms as clues to hereditary tumor syndromes. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85:239-256.

- Longo C, Pellacani G, Tomasi A, et al. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus: solitary tumor or sign of a complex gastrointestinal syndrome. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4:797-800.

- Warner TF, Burgess H, Mohs FE. Extramammary Paget’s disease in fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. J Cutan Pathol. 1982;9:340-344.

- Stern JB, Haupt HM, Smith RR. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus. eccrine duct spread of basal cell carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:585-587.

- Karsenti D, Tharsis G, Burtin P, et al. Adenoma and advanced neoplasia detection rates increase from 45 years of age. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:447-456.

- Bryant J. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus overlying breast cancer. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:310.

- Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar A, et al. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin: With Clinical Correlations. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020.

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP), or Pinkus tumor, is a rare tumor with a presentation similar to benign neoplasms such as acrochordons and seborrheic keratoses. Classically, FeP presents as a nontender, solitary, flesh-colored, firm, dome-shaped papule or plaque with a predilection for the lumbosacral region rather than sun-exposed areas. This tumor typically develops in fair-skinned older adults, more often in females.1

The association between cutaneous lesions and internal malignancies is well known to include dermatoses such as erythema repens in patients with lung cancer, or tripe palms and acanthosis nigricans in patients with gastrointestinal malignancy. Outside of paraneoplastic presentations, many syndromes have unique constellations of clinical findings that require the clinician to investigate for internal malignancy. Cancer-associated genodermatoses such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé, neurofibromatosis, and Cowden syndrome have key findings to alert the provider of potential internal malignancies.2 Given the rarity and relative novelty of FeP, few studies have been performed that evaluate for an association with internal malignancies.

There potentially is a common pathophysiologic mechanism between FeP and other benign and malignant tumors. Some have noted a possible common embryonic origin, such as Merkel cells, and even a common gene mutation involving tumor protein p53 or PTCH1 gene.3,4 Carcinoembryonic antigen is a glycoprotein often found in association with gastrointestinal tract tumors and also is elevated in some cases of FeP.5 A single-center retrospective study performed by Longo et al3 demonstrated an association between FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy by calculating a percentage of those with FeP who also had gastrointestinal tract tumors. Moreover, they noted that FeP preceded gastrointestinal tract tumors by up to 1 to 2 years. Using the results of this study, they suggested that a similar pathogenesis underlies the association between FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy, but a shared pathogenesis has not yet been elucidated.3

With a transition to preventive medicine and age-adjusted malignancy screening in the US medical community, the findings of FeP as a marker of gastrointestinal tract tumors could alter current recommendations of routine skin examinations and colorectal cancer screening. This study investigates the association between FeP and internal malignancy, especially gastrointestinal tract tumors.

Methods

Patient Selection—A single-center, retrospective, case-control study was designed to investigate an association between FeP and internal malignancy. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Naval Medical Center San Diego, California, in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. A medical record review was initiated using the Department of Defense (DoD) electronic health record to identify patients with a history of FeP. The query used a natural language search for patients who had received a histopathology report that included Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, Pinkus, or Pinkus tumor within the diagnosis or comment section for pathology specimens processed at our institution (Naval Medical Center San Diego). A total of 45 patients evaluated at Naval Medical Center San Diego had biopsy specimens that met inclusion criteria. Only 42 electronic medical records were available to review between January 1, 2003, and March 1, 2020. Three patients were excluded from the study for absent or incomplete medical records.

Study Procedures—Data extracted by researchers were analyzed for statistical significance. All available data in current electronic health records prior to the FeP diagnosis until March 1, 2020, was reviewed for other documented malignancy or colonoscopy data. Data extracted included age, sex, date of diagnosis of FeP, location of FeP, social history, and medical and surgical history to identify prior malignancy. Colorectal cancer screening results were drawn from original reports, gastrointestinal clinic notes, biopsy results, and/or primary care provider documentation of colonoscopy results. If the exact date of internal tumor diagnosis could not be determined but the year was known, the value “July, year” was utilized as the diagnosis date.

Statistical Analysis—Data were reviewed for validity, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. Graphical visualization assisted in reviewing the distribution of the data in relation to the internal tumors. The Fisher exact test was performed to test for associations, while continuous variables were assessed using the Student t test or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Analysis was conducted with StataCorp. 2017 Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 (StataCorp LLC). Significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Patient Demographics—Of the 42 patients with FeP included in this study, 28 (66.7%) were male and 14 (33.3%) were female. The overall mean age at FeP diagnosis was 56.83 years. The mean age (SD) at FeP diagnosis for males was 59.21 (19.00) years and 52.07 (21.61) for females (P=.2792)(Table 1). Other pertinent medical history, including alcohol and tobacco use, obesity, and diabetes mellitus, is included in Table 1.

Characterization of Tumors—The classification of the number of patients with any other nonskin neoplasm is presented in Table 2. Fifteen (35.7%) patients had 1 or more gastrointestinal tubular adenomas. Three patients were found to have colorectal adenocarcinoma. Karsenti et al6 published a large study of colonic adenoma detection rates in the World Journal of Gastroenterology stratified by age and found that the incidence of adenoma for those aged 55 to 59 years was 28.3% vs 35.7% in our study (P=.2978 [Fisher exact test]).

Given the number of gastrointestinal tract tumors detected, most of which were found during routine surveillance, and a prior study6 suggesting a relationship between FeP and gastrointestinal tract tumors, we analyzed the temporal relationship between the date of gastrointestinal tract tumor diagnosis and the date of FeP diagnosis to assess if gastrointestinal tract tumor or FeP might predict the onset of the other (Figure 1). By assigning a temporal category to each gastrointestinal tract tumor as occurring either before or after the FeP diagnosis by 0 to 3 years, 3 to 10 years, 10 to 15 years, and 15 or more years, the box plot in Figure 1 shows that gastrointestinal adenoma development had no significant temporal relationship to the presence of FeP, excluding any outliers (shown as dots). Additionally, in Figure 1, the same concept was applied to assess the relationship between the dates of all gastrointestinal tract tumors—benign, precancerous, or malignant—and the date of FeP diagnosis, which again showed that FeP and gastrointestinal tract tumors did not predict the onset of the other. Figure 2 showed the same for all nonskin tumor diagnoses and again demonstrated that FeP and all other nondermatologic tumors did not predict the onset of the other.

Comment

Malignancy Potential—The malignant potential of FeP—characterized as a trichoblastoma (an adnexal tumor) or a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) variant—has been documented.1 Haddock and Cohen1 noted that FeP can be considered as an intermediate variant between BCC and trichoblastomas. Furthermore, they questioned the relevance of differentiating FeP as benign or malignant.1 There are additional elements of FeP that currently are unknown, which can be partially attributed to its rarity. If we can clarify a more accurate pathogenic model of FeP, then common mutational pathways with other malignancies may be identified.

Screening for Malignancy in FeP Patients—Until recently, FeP has not been demonstrated to be associated with other cancers or to have increased metastatic potential.1 In a 1985 case series of 2 patients, FeP was found to be specifically overlying infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. After a unilateral mastectomy, examination of the overlying skin of the breast showed a solitary, lightly pigmented nodule, which was identified as an FeP after histopathologic evaluation.7 There have been limited investigations of whether FeP is simply a solitary tumor or a harbinger for other malignancies, despite a study by Longo et al3 that attempted to establish this temporal relationship. They recommended that patients with FeP be clinically evaluated and screened for gastrointestinal tract tumors.3 Based on these recommendations, textbooks for dermatopathology now highlight the possible correlation of FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy,8 which may lead to earlier and unwarranted screening.

Comparison to the General Population—Although our analysis showed a portion of patients with FeP have gastrointestinal tract tumors, we do not detect a significant difference from the general population. The average age at the time of FeP diagnosis in our study was 56.83 years compared with the average age of 64.0 years by Longo et al,3 where they found an association with gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors. As the rate of gastrointestinal adenoma and malignancy increases with age, the older population in the study by Longo et al3 may have developed colorectal cancer independent of FeP development. However, the rate of gastrointestinal or other malignancies in their study was substantially higher than that of the general population. The Longo et al3 study found that 22 of 49 patients developed nondermatologic malignancies within 2 years of FeP diagnosis. Additionally, no data were provided in the study regarding precancerous lesions.

In our study population, benign gastrointestinal tract tumors, specifically tubular adenomas, were noted in 35.7% of patients with FeP compared with 28.3% of the general population in the same age group reported by Karsenti et al.6 Although limited by our sample size, our study demonstrated that patients with FeP diagnosis showed no significant difference in age-stratified incidence of tubular adenoma compared with the general population (P=.2978). Figures 1 and 2 showed no obvious temporal relationship between the development of FeP and the diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumor—either precancerous or malignant lesions—suggesting that diagnosis of one does not indicate the presence of the other.

Relationship With Colonoscopy Results—By analyzing those patients with FeP who specifically had documented colonoscopy results, we did not find a correlation between FeP and gastrointestinal tubular adenoma or carcinoma at any time during the patients’ available records. Although some patients may have had undocumented colonoscopies performed outside the DoD medical system, most had evidence that these procedures were being performed by transcription into primary care provider notes, uploaded gastroenterologist clinical notes, or colonoscopy reports. It is unlikely a true colorectal or other malignancy would remain undocumented over years within the electronic medical record.

Study Limitations—Because of the nature of electronic medical records at multiple institutions, the quality and/or the quantity of medical documentation is not standardized across all patients. Not all pathology reports may include FeP as the primary diagnosis or description, as FeP may simply be reported as BCC. Despite thorough data extraction by physicians, we were limited to the data available within our electronic medical records. Colonoscopies and other specialty care often were performed by civilian providers. Documentation regarding where patients were referred for such procedures outside the DoD was not available unless reports were transmitted to the DoD or transcribed by primary care providers. Incomplete records may make it more difficult to identify and document the number and characteristics of patients’ tubular adenomas. Therefore, a complete review of civilian records was not possible, causing some patients’ medical records to be documented for a longer period of their lives than for others.

Conclusion

Given the discrepancies in our findings with the previous study,3 future investigations on FeP and associated tumors should focus on integrated health care systems with longitudinal data sets for all age-appropriate cancer screenings in a larger sample size. Another related study is needed to evaluate the pathophysiologic mechanisms of FeP development relative to known cancer lines.

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus (FeP), or Pinkus tumor, is a rare tumor with a presentation similar to benign neoplasms such as acrochordons and seborrheic keratoses. Classically, FeP presents as a nontender, solitary, flesh-colored, firm, dome-shaped papule or plaque with a predilection for the lumbosacral region rather than sun-exposed areas. This tumor typically develops in fair-skinned older adults, more often in females.1

The association between cutaneous lesions and internal malignancies is well known to include dermatoses such as erythema repens in patients with lung cancer, or tripe palms and acanthosis nigricans in patients with gastrointestinal malignancy. Outside of paraneoplastic presentations, many syndromes have unique constellations of clinical findings that require the clinician to investigate for internal malignancy. Cancer-associated genodermatoses such as Birt-Hogg-Dubé, neurofibromatosis, and Cowden syndrome have key findings to alert the provider of potential internal malignancies.2 Given the rarity and relative novelty of FeP, few studies have been performed that evaluate for an association with internal malignancies.

There potentially is a common pathophysiologic mechanism between FeP and other benign and malignant tumors. Some have noted a possible common embryonic origin, such as Merkel cells, and even a common gene mutation involving tumor protein p53 or PTCH1 gene.3,4 Carcinoembryonic antigen is a glycoprotein often found in association with gastrointestinal tract tumors and also is elevated in some cases of FeP.5 A single-center retrospective study performed by Longo et al3 demonstrated an association between FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy by calculating a percentage of those with FeP who also had gastrointestinal tract tumors. Moreover, they noted that FeP preceded gastrointestinal tract tumors by up to 1 to 2 years. Using the results of this study, they suggested that a similar pathogenesis underlies the association between FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy, but a shared pathogenesis has not yet been elucidated.3

With a transition to preventive medicine and age-adjusted malignancy screening in the US medical community, the findings of FeP as a marker of gastrointestinal tract tumors could alter current recommendations of routine skin examinations and colorectal cancer screening. This study investigates the association between FeP and internal malignancy, especially gastrointestinal tract tumors.

Methods

Patient Selection—A single-center, retrospective, case-control study was designed to investigate an association between FeP and internal malignancy. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the Naval Medical Center San Diego, California, in compliance with all applicable federal regulations governing the protection of human subjects. A medical record review was initiated using the Department of Defense (DoD) electronic health record to identify patients with a history of FeP. The query used a natural language search for patients who had received a histopathology report that included Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus, Pinkus, or Pinkus tumor within the diagnosis or comment section for pathology specimens processed at our institution (Naval Medical Center San Diego). A total of 45 patients evaluated at Naval Medical Center San Diego had biopsy specimens that met inclusion criteria. Only 42 electronic medical records were available to review between January 1, 2003, and March 1, 2020. Three patients were excluded from the study for absent or incomplete medical records.

Study Procedures—Data extracted by researchers were analyzed for statistical significance. All available data in current electronic health records prior to the FeP diagnosis until March 1, 2020, was reviewed for other documented malignancy or colonoscopy data. Data extracted included age, sex, date of diagnosis of FeP, location of FeP, social history, and medical and surgical history to identify prior malignancy. Colorectal cancer screening results were drawn from original reports, gastrointestinal clinic notes, biopsy results, and/or primary care provider documentation of colonoscopy results. If the exact date of internal tumor diagnosis could not be determined but the year was known, the value “July, year” was utilized as the diagnosis date.

Statistical Analysis—Data were reviewed for validity, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. Graphical visualization assisted in reviewing the distribution of the data in relation to the internal tumors. The Fisher exact test was performed to test for associations, while continuous variables were assessed using the Student t test or the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Analysis was conducted with StataCorp. 2017 Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 (StataCorp LLC). Significance was set at P<.05.

Results

Patient Demographics—Of the 42 patients with FeP included in this study, 28 (66.7%) were male and 14 (33.3%) were female. The overall mean age at FeP diagnosis was 56.83 years. The mean age (SD) at FeP diagnosis for males was 59.21 (19.00) years and 52.07 (21.61) for females (P=.2792)(Table 1). Other pertinent medical history, including alcohol and tobacco use, obesity, and diabetes mellitus, is included in Table 1.

Characterization of Tumors—The classification of the number of patients with any other nonskin neoplasm is presented in Table 2. Fifteen (35.7%) patients had 1 or more gastrointestinal tubular adenomas. Three patients were found to have colorectal adenocarcinoma. Karsenti et al6 published a large study of colonic adenoma detection rates in the World Journal of Gastroenterology stratified by age and found that the incidence of adenoma for those aged 55 to 59 years was 28.3% vs 35.7% in our study (P=.2978 [Fisher exact test]).

Given the number of gastrointestinal tract tumors detected, most of which were found during routine surveillance, and a prior study6 suggesting a relationship between FeP and gastrointestinal tract tumors, we analyzed the temporal relationship between the date of gastrointestinal tract tumor diagnosis and the date of FeP diagnosis to assess if gastrointestinal tract tumor or FeP might predict the onset of the other (Figure 1). By assigning a temporal category to each gastrointestinal tract tumor as occurring either before or after the FeP diagnosis by 0 to 3 years, 3 to 10 years, 10 to 15 years, and 15 or more years, the box plot in Figure 1 shows that gastrointestinal adenoma development had no significant temporal relationship to the presence of FeP, excluding any outliers (shown as dots). Additionally, in Figure 1, the same concept was applied to assess the relationship between the dates of all gastrointestinal tract tumors—benign, precancerous, or malignant—and the date of FeP diagnosis, which again showed that FeP and gastrointestinal tract tumors did not predict the onset of the other. Figure 2 showed the same for all nonskin tumor diagnoses and again demonstrated that FeP and all other nondermatologic tumors did not predict the onset of the other.

Comment

Malignancy Potential—The malignant potential of FeP—characterized as a trichoblastoma (an adnexal tumor) or a basal cell carcinoma (BCC) variant—has been documented.1 Haddock and Cohen1 noted that FeP can be considered as an intermediate variant between BCC and trichoblastomas. Furthermore, they questioned the relevance of differentiating FeP as benign or malignant.1 There are additional elements of FeP that currently are unknown, which can be partially attributed to its rarity. If we can clarify a more accurate pathogenic model of FeP, then common mutational pathways with other malignancies may be identified.

Screening for Malignancy in FeP Patients—Until recently, FeP has not been demonstrated to be associated with other cancers or to have increased metastatic potential.1 In a 1985 case series of 2 patients, FeP was found to be specifically overlying infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast. After a unilateral mastectomy, examination of the overlying skin of the breast showed a solitary, lightly pigmented nodule, which was identified as an FeP after histopathologic evaluation.7 There have been limited investigations of whether FeP is simply a solitary tumor or a harbinger for other malignancies, despite a study by Longo et al3 that attempted to establish this temporal relationship. They recommended that patients with FeP be clinically evaluated and screened for gastrointestinal tract tumors.3 Based on these recommendations, textbooks for dermatopathology now highlight the possible correlation of FeP and gastrointestinal malignancy,8 which may lead to earlier and unwarranted screening.

Comparison to the General Population—Although our analysis showed a portion of patients with FeP have gastrointestinal tract tumors, we do not detect a significant difference from the general population. The average age at the time of FeP diagnosis in our study was 56.83 years compared with the average age of 64.0 years by Longo et al,3 where they found an association with gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine tumors. As the rate of gastrointestinal adenoma and malignancy increases with age, the older population in the study by Longo et al3 may have developed colorectal cancer independent of FeP development. However, the rate of gastrointestinal or other malignancies in their study was substantially higher than that of the general population. The Longo et al3 study found that 22 of 49 patients developed nondermatologic malignancies within 2 years of FeP diagnosis. Additionally, no data were provided in the study regarding precancerous lesions.

In our study population, benign gastrointestinal tract tumors, specifically tubular adenomas, were noted in 35.7% of patients with FeP compared with 28.3% of the general population in the same age group reported by Karsenti et al.6 Although limited by our sample size, our study demonstrated that patients with FeP diagnosis showed no significant difference in age-stratified incidence of tubular adenoma compared with the general population (P=.2978). Figures 1 and 2 showed no obvious temporal relationship between the development of FeP and the diagnosis of gastrointestinal tumor—either precancerous or malignant lesions—suggesting that diagnosis of one does not indicate the presence of the other.

Relationship With Colonoscopy Results—By analyzing those patients with FeP who specifically had documented colonoscopy results, we did not find a correlation between FeP and gastrointestinal tubular adenoma or carcinoma at any time during the patients’ available records. Although some patients may have had undocumented colonoscopies performed outside the DoD medical system, most had evidence that these procedures were being performed by transcription into primary care provider notes, uploaded gastroenterologist clinical notes, or colonoscopy reports. It is unlikely a true colorectal or other malignancy would remain undocumented over years within the electronic medical record.

Study Limitations—Because of the nature of electronic medical records at multiple institutions, the quality and/or the quantity of medical documentation is not standardized across all patients. Not all pathology reports may include FeP as the primary diagnosis or description, as FeP may simply be reported as BCC. Despite thorough data extraction by physicians, we were limited to the data available within our electronic medical records. Colonoscopies and other specialty care often were performed by civilian providers. Documentation regarding where patients were referred for such procedures outside the DoD was not available unless reports were transmitted to the DoD or transcribed by primary care providers. Incomplete records may make it more difficult to identify and document the number and characteristics of patients’ tubular adenomas. Therefore, a complete review of civilian records was not possible, causing some patients’ medical records to be documented for a longer period of their lives than for others.

Conclusion

Given the discrepancies in our findings with the previous study,3 future investigations on FeP and associated tumors should focus on integrated health care systems with longitudinal data sets for all age-appropriate cancer screenings in a larger sample size. Another related study is needed to evaluate the pathophysiologic mechanisms of FeP development relative to known cancer lines.

- Haddock ES, Cohen PR. Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus revisited. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:347-362.