User login

‘Low and Slow’ hyperthermic treatment being evaluated for superficial and nodular BCCs

DENVER –

At the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, Christopher Zachary, MD, and colleagues described a novel, noninvasive standardized controlled hyperthermia and mapping protocol (CHAMP) designed to help clinicians with margin assessment and treatment of superficial and nodular basal cell cancers (BCCs). “There’s considerable interest on the part of the public in having CHAMP treatment for their BCCs,” Dr. Zachary, professor and chair emeritus, University of California, Irvine, told this news organization in advance of the meeting.

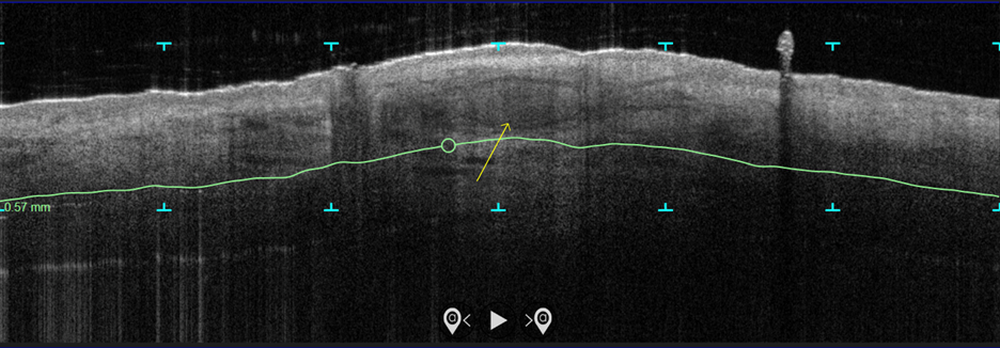

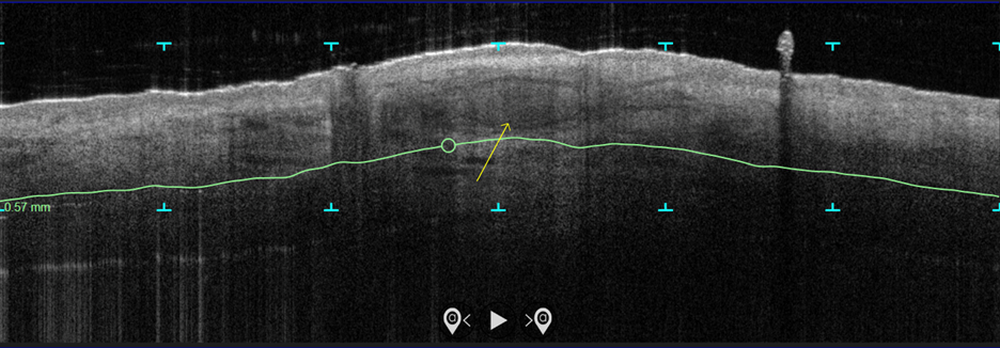

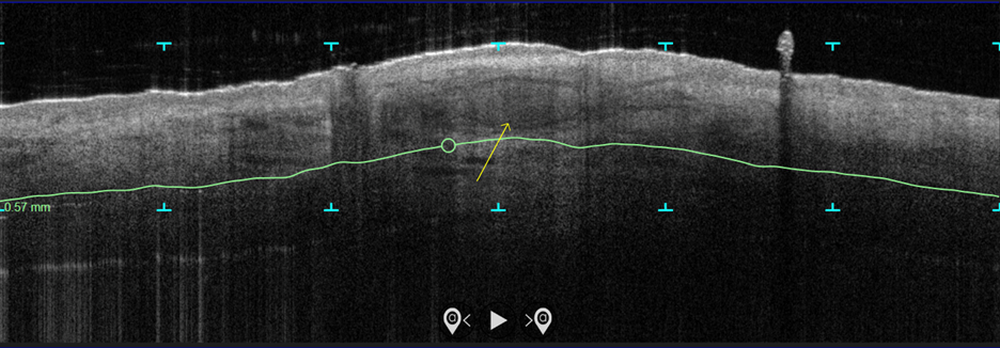

In the study, which is being conducted at three centers and plans to enroll 100 patients, more than 70 patients with biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs have been scanned with the VivoSight Dx optical coherence tomography (OCT) device to map BCC tumor margins. Next, they were treated with the Sciton 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser equipped with a 4-mm beam diameter scan pattern with no overlap and an 8-millisecond pulse duration, randomized to either 120 J/cm2 pulses, until tissue graying and contraction was observed, or a novel controlled hyperthermia technique known as “Low and Slow” using repeated 25 J/cm2 pulses under thermal camera imaging to maintain a consistent temperature of 55º C for 60 seconds.

The researchers reassessed the tissue response both clinically and by OCT at 3 months and the patients were retreated with the same method if residual BCC was demonstrated. At 3-12 months post treatment, the lesion sites were saucerized and examined histologically by step sections to confirm clearance.

“In contrast to the more commonly performed ‘standard’ long-pulse 1,064-nm laser tumor coagulation, where the end point is graying and contraction of tissue, the new controlled ‘Low and Slow’ technique heats the tissue to 55º C for 60 seconds, avoids ulceration, and induces apoptotic tumor disappearance by a caspase-3 and -7 mechanism,” Dr. Zachary explained in an interview. “It’s a gentler process that allows patients an alternative to second intention wounds that occur after electrodessication and curettage or Mohs,” he added, noting that CHAMP is not intended for the treatment of more complex, large, recurrent, or infiltrative BCCs.

In both study arms, the majority of patients enrolled to date have been found to be free of tumor at 3 months by clinical and OCT examination. “The study is ongoing, but the current numbers indicate that 9 out of 10 superficial and nodular BCCs are free of tumor at 3-12 months after the last treatment,” Dr. Zachary said. The standard-treatment arm, where tissue was treated to a gray color with tissue contraction, generally resulted in more blistering and tissue necrosis with prolonged healing, compared with the Low and Slow–controlled hyperthermia arm. BCC lesions treated in the controlled hyperthermia arm had a lilac gray color with “a surprising increase” in the Doppler blood flow rate, compared with those in the standard-treatment arm, he noted.

“Blood flow following the standard technique is dramatically reduced immediately post treatment, which accounts in part for the frequent ulceration and slow healing in that group,” Dr. Zachary said.

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that the optimal treatment parameters of the Low and Slow technique have yet to be realized. “It could be that we will achieve better results at 50º C for 70 seconds or similar,” he said. “While this technique will not in any way reduce the great benefits of Mohs surgery for complex BCCs, it will benefit those with simpler superficial and nodular BCCs, particularly in those who are not good surgical candidates.”

As an aside, Dr. Zachary supports the increased use of OCT scanners to improve the ability to diagnose and assess the lateral and deep margins of skin cancers. “I think that all dermatology residents should understand how to use these devices,” he said. “I’m convinced they are going to be useful in their clinical practice in the future.”

Keith L. Duffy, MD, who was asked to comment on the work, said that the study demonstrates novel ways to use existing and developing technologies in dermatology and highlights the intersection of aesthetic, surgical, and medical dermatology. “CHAMP is promising as shown by the data in the abstract and I am eager to see the final results of the study with an eye toward final cure rate and cosmesis,” said Dr. Duffy, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

“In my estimation, this technology will need to prove to be superior in one or both of these parameters in order to be considered a first- or second-line therapy,” he added. “My practice for these types of basal cell carcinomas is a simple one pass of curettage with aluminum chloride or pressure for hemostasis. The healing is fast, the cosmesis is excellent, and the cure rate is more than 90% for this simple in-office destruction. However, for those with access to this technology and proficiency with its use, CHAMP may become a viable alternative to our existing destructive methods. I look forward to seeing the published results of this multicenter trial.”

This study is being funded by Michelson Diagnostics. Sciton provided the long-pulsed 1,064-nm lasers devices being used in the trial. Neither Dr. Zachary nor Dr. Duffy reported having relevant disclosures.

DENVER –

At the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, Christopher Zachary, MD, and colleagues described a novel, noninvasive standardized controlled hyperthermia and mapping protocol (CHAMP) designed to help clinicians with margin assessment and treatment of superficial and nodular basal cell cancers (BCCs). “There’s considerable interest on the part of the public in having CHAMP treatment for their BCCs,” Dr. Zachary, professor and chair emeritus, University of California, Irvine, told this news organization in advance of the meeting.

In the study, which is being conducted at three centers and plans to enroll 100 patients, more than 70 patients with biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs have been scanned with the VivoSight Dx optical coherence tomography (OCT) device to map BCC tumor margins. Next, they were treated with the Sciton 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser equipped with a 4-mm beam diameter scan pattern with no overlap and an 8-millisecond pulse duration, randomized to either 120 J/cm2 pulses, until tissue graying and contraction was observed, or a novel controlled hyperthermia technique known as “Low and Slow” using repeated 25 J/cm2 pulses under thermal camera imaging to maintain a consistent temperature of 55º C for 60 seconds.

The researchers reassessed the tissue response both clinically and by OCT at 3 months and the patients were retreated with the same method if residual BCC was demonstrated. At 3-12 months post treatment, the lesion sites were saucerized and examined histologically by step sections to confirm clearance.

“In contrast to the more commonly performed ‘standard’ long-pulse 1,064-nm laser tumor coagulation, where the end point is graying and contraction of tissue, the new controlled ‘Low and Slow’ technique heats the tissue to 55º C for 60 seconds, avoids ulceration, and induces apoptotic tumor disappearance by a caspase-3 and -7 mechanism,” Dr. Zachary explained in an interview. “It’s a gentler process that allows patients an alternative to second intention wounds that occur after electrodessication and curettage or Mohs,” he added, noting that CHAMP is not intended for the treatment of more complex, large, recurrent, or infiltrative BCCs.

In both study arms, the majority of patients enrolled to date have been found to be free of tumor at 3 months by clinical and OCT examination. “The study is ongoing, but the current numbers indicate that 9 out of 10 superficial and nodular BCCs are free of tumor at 3-12 months after the last treatment,” Dr. Zachary said. The standard-treatment arm, where tissue was treated to a gray color with tissue contraction, generally resulted in more blistering and tissue necrosis with prolonged healing, compared with the Low and Slow–controlled hyperthermia arm. BCC lesions treated in the controlled hyperthermia arm had a lilac gray color with “a surprising increase” in the Doppler blood flow rate, compared with those in the standard-treatment arm, he noted.

“Blood flow following the standard technique is dramatically reduced immediately post treatment, which accounts in part for the frequent ulceration and slow healing in that group,” Dr. Zachary said.

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that the optimal treatment parameters of the Low and Slow technique have yet to be realized. “It could be that we will achieve better results at 50º C for 70 seconds or similar,” he said. “While this technique will not in any way reduce the great benefits of Mohs surgery for complex BCCs, it will benefit those with simpler superficial and nodular BCCs, particularly in those who are not good surgical candidates.”

As an aside, Dr. Zachary supports the increased use of OCT scanners to improve the ability to diagnose and assess the lateral and deep margins of skin cancers. “I think that all dermatology residents should understand how to use these devices,” he said. “I’m convinced they are going to be useful in their clinical practice in the future.”

Keith L. Duffy, MD, who was asked to comment on the work, said that the study demonstrates novel ways to use existing and developing technologies in dermatology and highlights the intersection of aesthetic, surgical, and medical dermatology. “CHAMP is promising as shown by the data in the abstract and I am eager to see the final results of the study with an eye toward final cure rate and cosmesis,” said Dr. Duffy, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

“In my estimation, this technology will need to prove to be superior in one or both of these parameters in order to be considered a first- or second-line therapy,” he added. “My practice for these types of basal cell carcinomas is a simple one pass of curettage with aluminum chloride or pressure for hemostasis. The healing is fast, the cosmesis is excellent, and the cure rate is more than 90% for this simple in-office destruction. However, for those with access to this technology and proficiency with its use, CHAMP may become a viable alternative to our existing destructive methods. I look forward to seeing the published results of this multicenter trial.”

This study is being funded by Michelson Diagnostics. Sciton provided the long-pulsed 1,064-nm lasers devices being used in the trial. Neither Dr. Zachary nor Dr. Duffy reported having relevant disclosures.

DENVER –

At the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, Christopher Zachary, MD, and colleagues described a novel, noninvasive standardized controlled hyperthermia and mapping protocol (CHAMP) designed to help clinicians with margin assessment and treatment of superficial and nodular basal cell cancers (BCCs). “There’s considerable interest on the part of the public in having CHAMP treatment for their BCCs,” Dr. Zachary, professor and chair emeritus, University of California, Irvine, told this news organization in advance of the meeting.

In the study, which is being conducted at three centers and plans to enroll 100 patients, more than 70 patients with biopsy-proven superficial and nodular BCCs have been scanned with the VivoSight Dx optical coherence tomography (OCT) device to map BCC tumor margins. Next, they were treated with the Sciton 1,064-nm Er:YAG laser equipped with a 4-mm beam diameter scan pattern with no overlap and an 8-millisecond pulse duration, randomized to either 120 J/cm2 pulses, until tissue graying and contraction was observed, or a novel controlled hyperthermia technique known as “Low and Slow” using repeated 25 J/cm2 pulses under thermal camera imaging to maintain a consistent temperature of 55º C for 60 seconds.

The researchers reassessed the tissue response both clinically and by OCT at 3 months and the patients were retreated with the same method if residual BCC was demonstrated. At 3-12 months post treatment, the lesion sites were saucerized and examined histologically by step sections to confirm clearance.

“In contrast to the more commonly performed ‘standard’ long-pulse 1,064-nm laser tumor coagulation, where the end point is graying and contraction of tissue, the new controlled ‘Low and Slow’ technique heats the tissue to 55º C for 60 seconds, avoids ulceration, and induces apoptotic tumor disappearance by a caspase-3 and -7 mechanism,” Dr. Zachary explained in an interview. “It’s a gentler process that allows patients an alternative to second intention wounds that occur after electrodessication and curettage or Mohs,” he added, noting that CHAMP is not intended for the treatment of more complex, large, recurrent, or infiltrative BCCs.

In both study arms, the majority of patients enrolled to date have been found to be free of tumor at 3 months by clinical and OCT examination. “The study is ongoing, but the current numbers indicate that 9 out of 10 superficial and nodular BCCs are free of tumor at 3-12 months after the last treatment,” Dr. Zachary said. The standard-treatment arm, where tissue was treated to a gray color with tissue contraction, generally resulted in more blistering and tissue necrosis with prolonged healing, compared with the Low and Slow–controlled hyperthermia arm. BCC lesions treated in the controlled hyperthermia arm had a lilac gray color with “a surprising increase” in the Doppler blood flow rate, compared with those in the standard-treatment arm, he noted.

“Blood flow following the standard technique is dramatically reduced immediately post treatment, which accounts in part for the frequent ulceration and slow healing in that group,” Dr. Zachary said.

He acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its relatively small sample size and the fact that the optimal treatment parameters of the Low and Slow technique have yet to be realized. “It could be that we will achieve better results at 50º C for 70 seconds or similar,” he said. “While this technique will not in any way reduce the great benefits of Mohs surgery for complex BCCs, it will benefit those with simpler superficial and nodular BCCs, particularly in those who are not good surgical candidates.”

As an aside, Dr. Zachary supports the increased use of OCT scanners to improve the ability to diagnose and assess the lateral and deep margins of skin cancers. “I think that all dermatology residents should understand how to use these devices,” he said. “I’m convinced they are going to be useful in their clinical practice in the future.”

Keith L. Duffy, MD, who was asked to comment on the work, said that the study demonstrates novel ways to use existing and developing technologies in dermatology and highlights the intersection of aesthetic, surgical, and medical dermatology. “CHAMP is promising as shown by the data in the abstract and I am eager to see the final results of the study with an eye toward final cure rate and cosmesis,” said Dr. Duffy, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

“In my estimation, this technology will need to prove to be superior in one or both of these parameters in order to be considered a first- or second-line therapy,” he added. “My practice for these types of basal cell carcinomas is a simple one pass of curettage with aluminum chloride or pressure for hemostasis. The healing is fast, the cosmesis is excellent, and the cure rate is more than 90% for this simple in-office destruction. However, for those with access to this technology and proficiency with its use, CHAMP may become a viable alternative to our existing destructive methods. I look forward to seeing the published results of this multicenter trial.”

This study is being funded by Michelson Diagnostics. Sciton provided the long-pulsed 1,064-nm lasers devices being used in the trial. Neither Dr. Zachary nor Dr. Duffy reported having relevant disclosures.

AT ASDS 2022

Liquid injectable silicone safe for acne scarring in dark-skinned patients, study finds

DENVER – Highly , results from a recent study showed.

“Acne is pervasive, and acne scarring disproportionately affects darker skin types,” lead study author Nicole Salame, MD, told this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where she presented the results of the study. “Treatment of acne scarring in darker skin is also particularly challenging since resurfacing can be problematic. Numerous treatment options exist but vary in effectiveness, sustainability, and side-effect profile, especially for patients with darker skin.”

Highly purified liquid injectable silicone (also known as LIS) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating intraocular tamponade of retinal detachment, and has been used off label for skin augmentation. A 2005 study of LIS for five patients with acne scarring, with up to 30 years of follow-up, showed efficacy and preservation of product without complications for depressed, broad-based acne scars .

“Use of LIS as a permanent treatment for acne scarring in darker skin types has yet to be evaluated,” said Dr. Salame, a 4th-year dermatology resident at Emory University, Atlanta. “Our study is the first to retrospectively evaluate the safety and efficacy of highly purified LIS for the treatment of acne scars in all skin types.”

Dr. Salame and coauthor Harold J. Brody, MD, evaluated the charts of 96 patients with a mean age of 51 years who received highly purified LIS for the treatment of acne scars at Dr. Brody’s Atlanta-based private dermatology practice between July 2010 and March 2021. Of the 96 patients, 31 had darker skin types (20 were Fitzpatrick skin type IV and 11 were Fitzpatrick skin type V). Dr. Brody performed all treatments: a total of 206 in the 96 patients.

The average time of follow-up was 6.31 years; 19 patients had a follow-up of 1-3 years, 25 had a follow-up of 3-5 years, and 52 had a follow-up of greater than 5 years. The researchers did not observe any complications along the course of the patients’ treatments, and no patients reported complications or dissatisfaction with treatment.

“Among the most impressive findings of our study was the permanence of effectiveness of LIS for acne scarring in patients who had treatment over a decade before,” Dr. Salame said. “Our longest follow up was 12 years. These patients continued to show improvement in their acne scarring years after treatment with LIS, even as they lost collagen and volume in their face with advancing age.”

In addition, she said, none of the patients experienced complications of granulomatous reactions, migration, or extrusion of product, which were previously documented with the use of macrodroplet injectable silicone techniques. “This is likely due to the consistent use of the microdroplet injection technique in our study – less than 0.01 cc per injection at minimum 6- to 8-week intervals or more,” Dr. Salame said.

Lawrence J. Green, MD, of the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the findings “show safety and durability of highly purified microdroplet liquid silicone to treat acne scars. The numbers of patients reviewed are small and selective (one highly skilled dermatologist), but with the right material (highly purified liquid silicone) and in a qualified and experienced physician’s hand, this treatment seems like a great option.”

Dr. Salame acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center, retrospective design. “Future prospective studies with larger patient populations of all skin types recruited from multiple centers may be needed,” she said.

The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest or funding sources to disclose. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

DENVER – Highly , results from a recent study showed.

“Acne is pervasive, and acne scarring disproportionately affects darker skin types,” lead study author Nicole Salame, MD, told this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where she presented the results of the study. “Treatment of acne scarring in darker skin is also particularly challenging since resurfacing can be problematic. Numerous treatment options exist but vary in effectiveness, sustainability, and side-effect profile, especially for patients with darker skin.”

Highly purified liquid injectable silicone (also known as LIS) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating intraocular tamponade of retinal detachment, and has been used off label for skin augmentation. A 2005 study of LIS for five patients with acne scarring, with up to 30 years of follow-up, showed efficacy and preservation of product without complications for depressed, broad-based acne scars .

“Use of LIS as a permanent treatment for acne scarring in darker skin types has yet to be evaluated,” said Dr. Salame, a 4th-year dermatology resident at Emory University, Atlanta. “Our study is the first to retrospectively evaluate the safety and efficacy of highly purified LIS for the treatment of acne scars in all skin types.”

Dr. Salame and coauthor Harold J. Brody, MD, evaluated the charts of 96 patients with a mean age of 51 years who received highly purified LIS for the treatment of acne scars at Dr. Brody’s Atlanta-based private dermatology practice between July 2010 and March 2021. Of the 96 patients, 31 had darker skin types (20 were Fitzpatrick skin type IV and 11 were Fitzpatrick skin type V). Dr. Brody performed all treatments: a total of 206 in the 96 patients.

The average time of follow-up was 6.31 years; 19 patients had a follow-up of 1-3 years, 25 had a follow-up of 3-5 years, and 52 had a follow-up of greater than 5 years. The researchers did not observe any complications along the course of the patients’ treatments, and no patients reported complications or dissatisfaction with treatment.

“Among the most impressive findings of our study was the permanence of effectiveness of LIS for acne scarring in patients who had treatment over a decade before,” Dr. Salame said. “Our longest follow up was 12 years. These patients continued to show improvement in their acne scarring years after treatment with LIS, even as they lost collagen and volume in their face with advancing age.”

In addition, she said, none of the patients experienced complications of granulomatous reactions, migration, or extrusion of product, which were previously documented with the use of macrodroplet injectable silicone techniques. “This is likely due to the consistent use of the microdroplet injection technique in our study – less than 0.01 cc per injection at minimum 6- to 8-week intervals or more,” Dr. Salame said.

Lawrence J. Green, MD, of the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the findings “show safety and durability of highly purified microdroplet liquid silicone to treat acne scars. The numbers of patients reviewed are small and selective (one highly skilled dermatologist), but with the right material (highly purified liquid silicone) and in a qualified and experienced physician’s hand, this treatment seems like a great option.”

Dr. Salame acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center, retrospective design. “Future prospective studies with larger patient populations of all skin types recruited from multiple centers may be needed,” she said.

The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest or funding sources to disclose. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

DENVER – Highly , results from a recent study showed.

“Acne is pervasive, and acne scarring disproportionately affects darker skin types,” lead study author Nicole Salame, MD, told this news organization in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where she presented the results of the study. “Treatment of acne scarring in darker skin is also particularly challenging since resurfacing can be problematic. Numerous treatment options exist but vary in effectiveness, sustainability, and side-effect profile, especially for patients with darker skin.”

Highly purified liquid injectable silicone (also known as LIS) is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating intraocular tamponade of retinal detachment, and has been used off label for skin augmentation. A 2005 study of LIS for five patients with acne scarring, with up to 30 years of follow-up, showed efficacy and preservation of product without complications for depressed, broad-based acne scars .

“Use of LIS as a permanent treatment for acne scarring in darker skin types has yet to be evaluated,” said Dr. Salame, a 4th-year dermatology resident at Emory University, Atlanta. “Our study is the first to retrospectively evaluate the safety and efficacy of highly purified LIS for the treatment of acne scars in all skin types.”

Dr. Salame and coauthor Harold J. Brody, MD, evaluated the charts of 96 patients with a mean age of 51 years who received highly purified LIS for the treatment of acne scars at Dr. Brody’s Atlanta-based private dermatology practice between July 2010 and March 2021. Of the 96 patients, 31 had darker skin types (20 were Fitzpatrick skin type IV and 11 were Fitzpatrick skin type V). Dr. Brody performed all treatments: a total of 206 in the 96 patients.

The average time of follow-up was 6.31 years; 19 patients had a follow-up of 1-3 years, 25 had a follow-up of 3-5 years, and 52 had a follow-up of greater than 5 years. The researchers did not observe any complications along the course of the patients’ treatments, and no patients reported complications or dissatisfaction with treatment.

“Among the most impressive findings of our study was the permanence of effectiveness of LIS for acne scarring in patients who had treatment over a decade before,” Dr. Salame said. “Our longest follow up was 12 years. These patients continued to show improvement in their acne scarring years after treatment with LIS, even as they lost collagen and volume in their face with advancing age.”

In addition, she said, none of the patients experienced complications of granulomatous reactions, migration, or extrusion of product, which were previously documented with the use of macrodroplet injectable silicone techniques. “This is likely due to the consistent use of the microdroplet injection technique in our study – less than 0.01 cc per injection at minimum 6- to 8-week intervals or more,” Dr. Salame said.

Lawrence J. Green, MD, of the department of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, who was asked to comment on the study, said that the findings “show safety and durability of highly purified microdroplet liquid silicone to treat acne scars. The numbers of patients reviewed are small and selective (one highly skilled dermatologist), but with the right material (highly purified liquid silicone) and in a qualified and experienced physician’s hand, this treatment seems like a great option.”

Dr. Salame acknowledged certain limitations of the study, including its single-center, retrospective design. “Future prospective studies with larger patient populations of all skin types recruited from multiple centers may be needed,” she said.

The researchers reported having no relevant conflicts of interest or funding sources to disclose. Dr. Green disclosed that he is a speaker, consultant, or investigator for numerous pharmaceutical companies.

AT ASDS 2022

Blindness from PRP injections a rare but potentially devastating side effect

DENVER – None of the cases involved scalp injections.

“Both soft tissue fillers and [PRP] are common injection-type treatments that dermatologists perform on the head and neck area,” lead study author Sean Wu, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session. “Fillers are usually used to replace volume and fill in lines while PRP is usually used for skin rejuvenation and certain forms of hair loss. We know that fillers may rarely cause blindness if accidentally injected into a facial artery.”

Certain facial areas such as the glabella, nose, and forehead are considered high risk for blindness with filler injections. But whether PRP injections in those areas may also result in blindness is not yet known, so Dr. Wu and his colleagues, Xu He, MD, and Robert Weiss, MD, at the Maryland Laser, Skin, and Vein Institute in Hunt Valley, Md., performed what is believed to be the first systematic review of the topic. In January 2022 they searched the PubMed database, which yielded 224 articles from which they selected four for full review. The results were recently published in Dermatologic Surgery.

Collectively, the four articles reported a total of seven patients with unilateral vision loss or impairment following PRP injection. They ranged in age from 41 to 63 years. Skin rejuvenation was the indication for PRP injection in six patients and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder in one. Three of the cases occurred in Venezuela while one each occurred in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia. All patients had signs of arterial occlusion or ischemia on retinal examination or imaging.

Dr. Wu and colleagues found that the glabella was the most common site of injection associated with vision loss (five cases), followed by the forehead (two cases), and one case each in the lateral canthus, nasolabial fold, and the TMJ. In all but two cases, vision loss occurred immediately after injection. (The number of injections exceeded seven because two patients received PRP in more than one site.)

Associated symptoms included ocular pain, fullness, eyelid ptosis, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tinnitus, and urinary urgency. At their initial ophthalmology evaluation, six patients had no light perception in the affected eye. Only one patient reported recovery of visual acuity at 3 months but with residual deficits on eye exam. This person had been evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

“The other cases reported complete blindness in one eye,” Dr. Wu said. “There is no reversing agent for PRP, unlike for many fillers, so there is no clear-cut solution for this issue.”

Based on the results of the systematic review, Dr. Wu concluded that blindness is a rare complication of PRP. “We should take the same precautions when injecting PRP on the face as we do when injecting fillers,” he advised. “This may include not injecting in high-risk areas and aspirating prior to injection to make sure we are not accidentally injecting into an artery.”

It was “notable,” he added, that no cases of blindness occurred following scalp injections of PRP for hair loss, indicating “that this use of PRP is likely very safe from a vision loss standpoint.”

Dr. Wu acknowledged certain imitations of the analysis, including the low quality of some case reports/series. “There is a notable lack of detail on the PRP injection technique, as the authors of the case reports were generally not the PRP injectors themselves,” he said. “There was also no attempt at treatment in a series of four cases.”

Asked to comment on the review, Terrence Keaney, MD, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va., said that the analysis underscores the importance of considering blindness as a possible side effect when injecting PRP into the face. “Using techniques that can minimize intravascular injections including the use of cannulas, aspiration, and larger needle size may help reduce this rare side effect,” said Dr. Keaney, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“It is important to recognize the lack of cases of blindness when injecting the scalp, one of the most popular PRP injection locations. This reduced risk may be due to the reduced communication between the scalp vasculature and the ophthalmic vasculature,” he added.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Keaney disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Crown Aesthetics.

DENVER – None of the cases involved scalp injections.

“Both soft tissue fillers and [PRP] are common injection-type treatments that dermatologists perform on the head and neck area,” lead study author Sean Wu, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session. “Fillers are usually used to replace volume and fill in lines while PRP is usually used for skin rejuvenation and certain forms of hair loss. We know that fillers may rarely cause blindness if accidentally injected into a facial artery.”

Certain facial areas such as the glabella, nose, and forehead are considered high risk for blindness with filler injections. But whether PRP injections in those areas may also result in blindness is not yet known, so Dr. Wu and his colleagues, Xu He, MD, and Robert Weiss, MD, at the Maryland Laser, Skin, and Vein Institute in Hunt Valley, Md., performed what is believed to be the first systematic review of the topic. In January 2022 they searched the PubMed database, which yielded 224 articles from which they selected four for full review. The results were recently published in Dermatologic Surgery.

Collectively, the four articles reported a total of seven patients with unilateral vision loss or impairment following PRP injection. They ranged in age from 41 to 63 years. Skin rejuvenation was the indication for PRP injection in six patients and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder in one. Three of the cases occurred in Venezuela while one each occurred in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia. All patients had signs of arterial occlusion or ischemia on retinal examination or imaging.

Dr. Wu and colleagues found that the glabella was the most common site of injection associated with vision loss (five cases), followed by the forehead (two cases), and one case each in the lateral canthus, nasolabial fold, and the TMJ. In all but two cases, vision loss occurred immediately after injection. (The number of injections exceeded seven because two patients received PRP in more than one site.)

Associated symptoms included ocular pain, fullness, eyelid ptosis, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tinnitus, and urinary urgency. At their initial ophthalmology evaluation, six patients had no light perception in the affected eye. Only one patient reported recovery of visual acuity at 3 months but with residual deficits on eye exam. This person had been evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

“The other cases reported complete blindness in one eye,” Dr. Wu said. “There is no reversing agent for PRP, unlike for many fillers, so there is no clear-cut solution for this issue.”

Based on the results of the systematic review, Dr. Wu concluded that blindness is a rare complication of PRP. “We should take the same precautions when injecting PRP on the face as we do when injecting fillers,” he advised. “This may include not injecting in high-risk areas and aspirating prior to injection to make sure we are not accidentally injecting into an artery.”

It was “notable,” he added, that no cases of blindness occurred following scalp injections of PRP for hair loss, indicating “that this use of PRP is likely very safe from a vision loss standpoint.”

Dr. Wu acknowledged certain imitations of the analysis, including the low quality of some case reports/series. “There is a notable lack of detail on the PRP injection technique, as the authors of the case reports were generally not the PRP injectors themselves,” he said. “There was also no attempt at treatment in a series of four cases.”

Asked to comment on the review, Terrence Keaney, MD, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va., said that the analysis underscores the importance of considering blindness as a possible side effect when injecting PRP into the face. “Using techniques that can minimize intravascular injections including the use of cannulas, aspiration, and larger needle size may help reduce this rare side effect,” said Dr. Keaney, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“It is important to recognize the lack of cases of blindness when injecting the scalp, one of the most popular PRP injection locations. This reduced risk may be due to the reduced communication between the scalp vasculature and the ophthalmic vasculature,” he added.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Keaney disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Crown Aesthetics.

DENVER – None of the cases involved scalp injections.

“Both soft tissue fillers and [PRP] are common injection-type treatments that dermatologists perform on the head and neck area,” lead study author Sean Wu, MD, said in an interview in advance of the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery, where he presented the results during an oral abstract session. “Fillers are usually used to replace volume and fill in lines while PRP is usually used for skin rejuvenation and certain forms of hair loss. We know that fillers may rarely cause blindness if accidentally injected into a facial artery.”

Certain facial areas such as the glabella, nose, and forehead are considered high risk for blindness with filler injections. But whether PRP injections in those areas may also result in blindness is not yet known, so Dr. Wu and his colleagues, Xu He, MD, and Robert Weiss, MD, at the Maryland Laser, Skin, and Vein Institute in Hunt Valley, Md., performed what is believed to be the first systematic review of the topic. In January 2022 they searched the PubMed database, which yielded 224 articles from which they selected four for full review. The results were recently published in Dermatologic Surgery.

Collectively, the four articles reported a total of seven patients with unilateral vision loss or impairment following PRP injection. They ranged in age from 41 to 63 years. Skin rejuvenation was the indication for PRP injection in six patients and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder in one. Three of the cases occurred in Venezuela while one each occurred in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Malaysia. All patients had signs of arterial occlusion or ischemia on retinal examination or imaging.

Dr. Wu and colleagues found that the glabella was the most common site of injection associated with vision loss (five cases), followed by the forehead (two cases), and one case each in the lateral canthus, nasolabial fold, and the TMJ. In all but two cases, vision loss occurred immediately after injection. (The number of injections exceeded seven because two patients received PRP in more than one site.)

Associated symptoms included ocular pain, fullness, eyelid ptosis, headache, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tinnitus, and urinary urgency. At their initial ophthalmology evaluation, six patients had no light perception in the affected eye. Only one patient reported recovery of visual acuity at 3 months but with residual deficits on eye exam. This person had been evaluated and treated by an ophthalmologist within 3 hours of symptom onset.

“The other cases reported complete blindness in one eye,” Dr. Wu said. “There is no reversing agent for PRP, unlike for many fillers, so there is no clear-cut solution for this issue.”

Based on the results of the systematic review, Dr. Wu concluded that blindness is a rare complication of PRP. “We should take the same precautions when injecting PRP on the face as we do when injecting fillers,” he advised. “This may include not injecting in high-risk areas and aspirating prior to injection to make sure we are not accidentally injecting into an artery.”

It was “notable,” he added, that no cases of blindness occurred following scalp injections of PRP for hair loss, indicating “that this use of PRP is likely very safe from a vision loss standpoint.”

Dr. Wu acknowledged certain imitations of the analysis, including the low quality of some case reports/series. “There is a notable lack of detail on the PRP injection technique, as the authors of the case reports were generally not the PRP injectors themselves,” he said. “There was also no attempt at treatment in a series of four cases.”

Asked to comment on the review, Terrence Keaney, MD, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va., said that the analysis underscores the importance of considering blindness as a possible side effect when injecting PRP into the face. “Using techniques that can minimize intravascular injections including the use of cannulas, aspiration, and larger needle size may help reduce this rare side effect,” said Dr. Keaney, a clinical associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington.

“It is important to recognize the lack of cases of blindness when injecting the scalp, one of the most popular PRP injection locations. This reduced risk may be due to the reduced communication between the scalp vasculature and the ophthalmic vasculature,” he added.

The study authors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Keaney disclosed that he is a member of the advisory board for Crown Aesthetics.

AT ASDS 2022

Pulmonary Vascular Disease & Cardiovascular Disease Network

Cardiovascular Medicine & Surgery Section

Emerging role of cardiopulmonary obstetric critical care

, with 23.8 women dying per 100,000 live births (Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. Maternal mortality in the United States. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 69 no 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020). The care of this vulnerable population testifies to the quality of care provided across the country. Some of these poor outcomes are directly attributed to in-hospital deaths due to preexisting or newly discovered heart or lung diseases, such as valvular heart diseases, cardiomyopathies, pulmonary arterial hypertension, eclampsia, or other etiologies. With the development of advanced heart and lung programs across the nation capable of providing mechanical circulatory support and extracorporeal life support, we believe that incorporating a heart-lung-OB team approach to high-risk cases can identify knowledge gaps early and predict and prevent maternal complications.

In this proposed model, patients funnel to the hub facility to be cared for by a team of intensive care physicians, advanced heart failure physicians, cardiovascular and obstetric anesthesiologists, and maternal/fetal medicine physicians, with the potential addition of an adult ECMO team member.

A team huddle, using a virtual platform, would be organized by a designated OB coordinator at the patient’s admission with follow-up huddles every 2 to 3 days, to ensure the team stays engaged through delivery into the postpartum period. Value could be added with subsequent cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation. With an emphasis on shared decision making, we can make it a national priority to save every woman during the birthing process.

Bindu Akkanti, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Mark Warner, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Cardiovascular Medicine & Surgery Section

Emerging role of cardiopulmonary obstetric critical care

, with 23.8 women dying per 100,000 live births (Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. Maternal mortality in the United States. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 69 no 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020). The care of this vulnerable population testifies to the quality of care provided across the country. Some of these poor outcomes are directly attributed to in-hospital deaths due to preexisting or newly discovered heart or lung diseases, such as valvular heart diseases, cardiomyopathies, pulmonary arterial hypertension, eclampsia, or other etiologies. With the development of advanced heart and lung programs across the nation capable of providing mechanical circulatory support and extracorporeal life support, we believe that incorporating a heart-lung-OB team approach to high-risk cases can identify knowledge gaps early and predict and prevent maternal complications.

In this proposed model, patients funnel to the hub facility to be cared for by a team of intensive care physicians, advanced heart failure physicians, cardiovascular and obstetric anesthesiologists, and maternal/fetal medicine physicians, with the potential addition of an adult ECMO team member.

A team huddle, using a virtual platform, would be organized by a designated OB coordinator at the patient’s admission with follow-up huddles every 2 to 3 days, to ensure the team stays engaged through delivery into the postpartum period. Value could be added with subsequent cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation. With an emphasis on shared decision making, we can make it a national priority to save every woman during the birthing process.

Bindu Akkanti, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Mark Warner, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Cardiovascular Medicine & Surgery Section

Emerging role of cardiopulmonary obstetric critical care

, with 23.8 women dying per 100,000 live births (Hoyert DL, Miniño AM. Maternal mortality in the United States. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 69 no 2. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020). The care of this vulnerable population testifies to the quality of care provided across the country. Some of these poor outcomes are directly attributed to in-hospital deaths due to preexisting or newly discovered heart or lung diseases, such as valvular heart diseases, cardiomyopathies, pulmonary arterial hypertension, eclampsia, or other etiologies. With the development of advanced heart and lung programs across the nation capable of providing mechanical circulatory support and extracorporeal life support, we believe that incorporating a heart-lung-OB team approach to high-risk cases can identify knowledge gaps early and predict and prevent maternal complications.

In this proposed model, patients funnel to the hub facility to be cared for by a team of intensive care physicians, advanced heart failure physicians, cardiovascular and obstetric anesthesiologists, and maternal/fetal medicine physicians, with the potential addition of an adult ECMO team member.

A team huddle, using a virtual platform, would be organized by a designated OB coordinator at the patient’s admission with follow-up huddles every 2 to 3 days, to ensure the team stays engaged through delivery into the postpartum period. Value could be added with subsequent cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation. With an emphasis on shared decision making, we can make it a national priority to save every woman during the birthing process.

Bindu Akkanti, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Mark Warner, MD, FCCP, Member-at-Large

Diffuse Lung Disease & Transplant Network

Lung Transplant Section

Strengthening lung transplant education

The number of lung transplants (LT) performed reached an all-time high in 2019 with a 52.3% increase over the previous decade. Transplants are being performed in older and sicker patients with 35% of recipients being over 65 years of age and 25% with lung allocation scores (LAS) over 60. (Valapour, et al. Am J Transplant. 2021;21[Suppl 2]:441). This growth has led to an increased demand for transplant pulmonologists. There are about 15 dedicated LT fellowship programs located at 68 transplant centers with widely variable curricula. The vast majority of the 160 general pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) fellowship programs do not have access to hands-on clinical transplant training and are guided by vague ACGME guidelines. A U.S. national survey (Town JA, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13[4]:568) of PCCM programs found that about 41% of centers did not have a transplant curriculum, and training was very variable. Another report found that a structured educational LT curriculum at a transplant center was associated with improved performance of PCCM fellows (Hayes, et al. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25[1]:59). The lack of a structured curriculum and wide variability coupled with lack of information about the training pathways impedes effective training.

Recognizing these issues, the lung transplant steering committee developed two webinars for the online CHEST learning portal (tinyurl.com/53pnne2k). These provide resources and information for fellows and junior faculty interested in a transplant pulmonology career as well as discuss needs and opportunities to develop a program for specialized training in LT. There is need for a multipronged approach addressing:

–Increase access to specialized transplant education for PCCM fellows.

–Develop a uniform structured curriculum for lung transplant education engaging the PCCM and transplant fellowship program directors as stakeholders.

–Increase collaboration between the transplant fellowship programs to address gaps in training.

Hakim Azhfar Ali, MBBS, FCCP

Member-at-Large

Lung Transplant Section

Strengthening lung transplant education

The number of lung transplants (LT) performed reached an all-time high in 2019 with a 52.3% increase over the previous decade. Transplants are being performed in older and sicker patients with 35% of recipients being over 65 years of age and 25% with lung allocation scores (LAS) over 60. (Valapour, et al. Am J Transplant. 2021;21[Suppl 2]:441). This growth has led to an increased demand for transplant pulmonologists. There are about 15 dedicated LT fellowship programs located at 68 transplant centers with widely variable curricula. The vast majority of the 160 general pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) fellowship programs do not have access to hands-on clinical transplant training and are guided by vague ACGME guidelines. A U.S. national survey (Town JA, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13[4]:568) of PCCM programs found that about 41% of centers did not have a transplant curriculum, and training was very variable. Another report found that a structured educational LT curriculum at a transplant center was associated with improved performance of PCCM fellows (Hayes, et al. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25[1]:59). The lack of a structured curriculum and wide variability coupled with lack of information about the training pathways impedes effective training.

Recognizing these issues, the lung transplant steering committee developed two webinars for the online CHEST learning portal (tinyurl.com/53pnne2k). These provide resources and information for fellows and junior faculty interested in a transplant pulmonology career as well as discuss needs and opportunities to develop a program for specialized training in LT. There is need for a multipronged approach addressing:

–Increase access to specialized transplant education for PCCM fellows.

–Develop a uniform structured curriculum for lung transplant education engaging the PCCM and transplant fellowship program directors as stakeholders.

–Increase collaboration between the transplant fellowship programs to address gaps in training.

Hakim Azhfar Ali, MBBS, FCCP

Member-at-Large

Lung Transplant Section

Strengthening lung transplant education

The number of lung transplants (LT) performed reached an all-time high in 2019 with a 52.3% increase over the previous decade. Transplants are being performed in older and sicker patients with 35% of recipients being over 65 years of age and 25% with lung allocation scores (LAS) over 60. (Valapour, et al. Am J Transplant. 2021;21[Suppl 2]:441). This growth has led to an increased demand for transplant pulmonologists. There are about 15 dedicated LT fellowship programs located at 68 transplant centers with widely variable curricula. The vast majority of the 160 general pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) fellowship programs do not have access to hands-on clinical transplant training and are guided by vague ACGME guidelines. A U.S. national survey (Town JA, et al. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13[4]:568) of PCCM programs found that about 41% of centers did not have a transplant curriculum, and training was very variable. Another report found that a structured educational LT curriculum at a transplant center was associated with improved performance of PCCM fellows (Hayes, et al. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25[1]:59). The lack of a structured curriculum and wide variability coupled with lack of information about the training pathways impedes effective training.

Recognizing these issues, the lung transplant steering committee developed two webinars for the online CHEST learning portal (tinyurl.com/53pnne2k). These provide resources and information for fellows and junior faculty interested in a transplant pulmonology career as well as discuss needs and opportunities to develop a program for specialized training in LT. There is need for a multipronged approach addressing:

–Increase access to specialized transplant education for PCCM fellows.

–Develop a uniform structured curriculum for lung transplant education engaging the PCCM and transplant fellowship program directors as stakeholders.

–Increase collaboration between the transplant fellowship programs to address gaps in training.

Hakim Azhfar Ali, MBBS, FCCP

Member-at-Large

Nifedipine during labor controls BP in severe preeclampsia

Women with preeclampsia with severe features benefit from treatment with oral nifedipine during labor and delivery, results of a randomized controlled trial suggest.

The study showed that intrapartum administration of extended-release oral nifedipine was safe and reduced the need for acute intravenous or immediate-release oral hypertensive therapy. There was a trend toward fewer cesarean deliveries and less need for neonatal intensive care.

The results suggest that providers “consider initiating long-acting nifedipine every 24 hours for individuals with preeclampsia with severe features who are undergoing induction of labor,” Erin M. Cleary, MD, with the Ohio State University, Columbus, told this news organization.

“There is no need to wait until patients require one or more doses of acute [antihypertensive] therapy before starting long-acting nifedipine, as long as they otherwise meet criteria for preeclampsia with severe features,” Dr. Cleary said.

The study was published online in Hypertension.

Clear benefits for mom and baby

Preeclampsia complicates up to 8% of pregnancies and often leads to significant maternal and perinatal morbidity.

“We know that bringing down very high blood pressure to a safer range will help prevent maternal and fetal complications. However, besides rapid-acting, intravenous medicines for severe hypertension during pregnancy, optimal management for hypertension during the labor and delivery process has not been studied,” Dr. Cleary explains in a news release.

In a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study, the researchers assessed whether treatment with long-acting nifedipine could prevent severe hypertension in women with a singleton or twin gestation and preeclampsia with severe features, as defined according to American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology criteria.

During induction of labor between 22 and 41 weeks’ gestation, 55 women were assigned to 30-mg oral extended-release nifedipine, and 55 received matching placebo, administered every 24 hours until delivery.

The primary outcome was receipt of one or more doses of acute hypertension therapy for blood pressure of at least 160/110 mm Hg that was sustained for 10 minutes or longer.

The primary outcome occurred in significantly fewer women in the nifedipine group than in the placebo group (34% vs. 55%; relative risk, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39-0.97; number needed to treat, 4.7).

Fewer women in the nifedipine group than in the placebo group required cesarean delivery, although this difference did not meet statistical significance (21% vs. 35%; RR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.31-1.15).

There was no between-group difference in the rate of hypotensive episodes, including symptomatic hypotension requiring phenylephrine for pressure support following neuraxial anesthesia (9.4% vs. 8.2%; RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.33-4.06).

After delivery, there was no difference in the rate of persistently severe blood pressure that required acute therapy and maintenance therapy at time of discharge home.

Birth weight and rates of births of neonates who were small for gestational age were similar in the two groups. There was a trend for decreased rates of neonatal intensive care unit admission among infants born to mothers who received nifedipine (29% vs. 47%; RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.37-1.02).

The neonatal composite outcome was also similar between the nifedipine group and the placebo group (36% vs. 41%; RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.51-1.37). The composite outcome included Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 minutes, hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, hypoglycemia requiring intravenous therapy, or supplemental oxygen therapy beyond the first 24 hours of life.

“Our findings support the growing trend in more active management of hypertension in pregnancy with daily maintenance medications,” Dr. Cleary and colleagues note in their article.

“Even in the absence of preeclampsia, emerging research suggests pregnant individuals may benefit from initiating and titrating antihypertensive therapy at goals similar to the nonobstetric population,” they add.

Potentially practice changing

Reached for comment, Vesna Garovic, MD, PhD, with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that this is an “important initial paper to start a very important conversation about blood pressure treatment goals in preeclampsia.”

Dr. Garovic noted that for chronic hypertension in pregnancy, the blood pressure treatment goal is now less than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg.

“However, this does not apply to preeclampsia, where quite high blood pressures, such 160/110 mm Hg or higher, are still allowed before treatment is considered,” Dr. Garovic said.

“This study shows that as soon as you reach that level, treatment with oral nifedipine should be initiated and that timely initiation of oral nifedipine may optimize blood pressure control and decrease the need for intravenous therapy subsequently, and that has good effects on the mother without adversely affecting the baby,” Dr. Garovic said.

“This is potentially practice changing,” Dr. Garovic added. “But the elephant in the room is the question of why we are waiting for blood pressure to reach such dangerous levels before initiating treatment, and whether initiating treatment at a blood pressure of 140/90 or higher may prevent blood pressure reaching these high levels and women developing complications that are the consequence of severe hypertension.”

The study was funded by the Ohio State University’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Dr. Cleary and Dr. Garovic have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with preeclampsia with severe features benefit from treatment with oral nifedipine during labor and delivery, results of a randomized controlled trial suggest.

The study showed that intrapartum administration of extended-release oral nifedipine was safe and reduced the need for acute intravenous or immediate-release oral hypertensive therapy. There was a trend toward fewer cesarean deliveries and less need for neonatal intensive care.

The results suggest that providers “consider initiating long-acting nifedipine every 24 hours for individuals with preeclampsia with severe features who are undergoing induction of labor,” Erin M. Cleary, MD, with the Ohio State University, Columbus, told this news organization.

“There is no need to wait until patients require one or more doses of acute [antihypertensive] therapy before starting long-acting nifedipine, as long as they otherwise meet criteria for preeclampsia with severe features,” Dr. Cleary said.

The study was published online in Hypertension.

Clear benefits for mom and baby

Preeclampsia complicates up to 8% of pregnancies and often leads to significant maternal and perinatal morbidity.

“We know that bringing down very high blood pressure to a safer range will help prevent maternal and fetal complications. However, besides rapid-acting, intravenous medicines for severe hypertension during pregnancy, optimal management for hypertension during the labor and delivery process has not been studied,” Dr. Cleary explains in a news release.

In a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study, the researchers assessed whether treatment with long-acting nifedipine could prevent severe hypertension in women with a singleton or twin gestation and preeclampsia with severe features, as defined according to American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology criteria.

During induction of labor between 22 and 41 weeks’ gestation, 55 women were assigned to 30-mg oral extended-release nifedipine, and 55 received matching placebo, administered every 24 hours until delivery.

The primary outcome was receipt of one or more doses of acute hypertension therapy for blood pressure of at least 160/110 mm Hg that was sustained for 10 minutes or longer.

The primary outcome occurred in significantly fewer women in the nifedipine group than in the placebo group (34% vs. 55%; relative risk, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39-0.97; number needed to treat, 4.7).

Fewer women in the nifedipine group than in the placebo group required cesarean delivery, although this difference did not meet statistical significance (21% vs. 35%; RR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.31-1.15).

There was no between-group difference in the rate of hypotensive episodes, including symptomatic hypotension requiring phenylephrine for pressure support following neuraxial anesthesia (9.4% vs. 8.2%; RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.33-4.06).

After delivery, there was no difference in the rate of persistently severe blood pressure that required acute therapy and maintenance therapy at time of discharge home.

Birth weight and rates of births of neonates who were small for gestational age were similar in the two groups. There was a trend for decreased rates of neonatal intensive care unit admission among infants born to mothers who received nifedipine (29% vs. 47%; RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.37-1.02).

The neonatal composite outcome was also similar between the nifedipine group and the placebo group (36% vs. 41%; RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.51-1.37). The composite outcome included Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 minutes, hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, hypoglycemia requiring intravenous therapy, or supplemental oxygen therapy beyond the first 24 hours of life.

“Our findings support the growing trend in more active management of hypertension in pregnancy with daily maintenance medications,” Dr. Cleary and colleagues note in their article.

“Even in the absence of preeclampsia, emerging research suggests pregnant individuals may benefit from initiating and titrating antihypertensive therapy at goals similar to the nonobstetric population,” they add.

Potentially practice changing

Reached for comment, Vesna Garovic, MD, PhD, with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that this is an “important initial paper to start a very important conversation about blood pressure treatment goals in preeclampsia.”

Dr. Garovic noted that for chronic hypertension in pregnancy, the blood pressure treatment goal is now less than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg.

“However, this does not apply to preeclampsia, where quite high blood pressures, such 160/110 mm Hg or higher, are still allowed before treatment is considered,” Dr. Garovic said.

“This study shows that as soon as you reach that level, treatment with oral nifedipine should be initiated and that timely initiation of oral nifedipine may optimize blood pressure control and decrease the need for intravenous therapy subsequently, and that has good effects on the mother without adversely affecting the baby,” Dr. Garovic said.

“This is potentially practice changing,” Dr. Garovic added. “But the elephant in the room is the question of why we are waiting for blood pressure to reach such dangerous levels before initiating treatment, and whether initiating treatment at a blood pressure of 140/90 or higher may prevent blood pressure reaching these high levels and women developing complications that are the consequence of severe hypertension.”

The study was funded by the Ohio State University’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Dr. Cleary and Dr. Garovic have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with preeclampsia with severe features benefit from treatment with oral nifedipine during labor and delivery, results of a randomized controlled trial suggest.

The study showed that intrapartum administration of extended-release oral nifedipine was safe and reduced the need for acute intravenous or immediate-release oral hypertensive therapy. There was a trend toward fewer cesarean deliveries and less need for neonatal intensive care.

The results suggest that providers “consider initiating long-acting nifedipine every 24 hours for individuals with preeclampsia with severe features who are undergoing induction of labor,” Erin M. Cleary, MD, with the Ohio State University, Columbus, told this news organization.

“There is no need to wait until patients require one or more doses of acute [antihypertensive] therapy before starting long-acting nifedipine, as long as they otherwise meet criteria for preeclampsia with severe features,” Dr. Cleary said.

The study was published online in Hypertension.

Clear benefits for mom and baby

Preeclampsia complicates up to 8% of pregnancies and often leads to significant maternal and perinatal morbidity.

“We know that bringing down very high blood pressure to a safer range will help prevent maternal and fetal complications. However, besides rapid-acting, intravenous medicines for severe hypertension during pregnancy, optimal management for hypertension during the labor and delivery process has not been studied,” Dr. Cleary explains in a news release.

In a randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study, the researchers assessed whether treatment with long-acting nifedipine could prevent severe hypertension in women with a singleton or twin gestation and preeclampsia with severe features, as defined according to American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology criteria.

During induction of labor between 22 and 41 weeks’ gestation, 55 women were assigned to 30-mg oral extended-release nifedipine, and 55 received matching placebo, administered every 24 hours until delivery.

The primary outcome was receipt of one or more doses of acute hypertension therapy for blood pressure of at least 160/110 mm Hg that was sustained for 10 minutes or longer.

The primary outcome occurred in significantly fewer women in the nifedipine group than in the placebo group (34% vs. 55%; relative risk, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.39-0.97; number needed to treat, 4.7).

Fewer women in the nifedipine group than in the placebo group required cesarean delivery, although this difference did not meet statistical significance (21% vs. 35%; RR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.31-1.15).

There was no between-group difference in the rate of hypotensive episodes, including symptomatic hypotension requiring phenylephrine for pressure support following neuraxial anesthesia (9.4% vs. 8.2%; RR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.33-4.06).

After delivery, there was no difference in the rate of persistently severe blood pressure that required acute therapy and maintenance therapy at time of discharge home.

Birth weight and rates of births of neonates who were small for gestational age were similar in the two groups. There was a trend for decreased rates of neonatal intensive care unit admission among infants born to mothers who received nifedipine (29% vs. 47%; RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.37-1.02).

The neonatal composite outcome was also similar between the nifedipine group and the placebo group (36% vs. 41%; RR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.51-1.37). The composite outcome included Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 minutes, hyperbilirubinemia requiring phototherapy, hypoglycemia requiring intravenous therapy, or supplemental oxygen therapy beyond the first 24 hours of life.

“Our findings support the growing trend in more active management of hypertension in pregnancy with daily maintenance medications,” Dr. Cleary and colleagues note in their article.

“Even in the absence of preeclampsia, emerging research suggests pregnant individuals may benefit from initiating and titrating antihypertensive therapy at goals similar to the nonobstetric population,” they add.

Potentially practice changing

Reached for comment, Vesna Garovic, MD, PhD, with Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said that this is an “important initial paper to start a very important conversation about blood pressure treatment goals in preeclampsia.”

Dr. Garovic noted that for chronic hypertension in pregnancy, the blood pressure treatment goal is now less than or equal to 140/90 mm Hg.

“However, this does not apply to preeclampsia, where quite high blood pressures, such 160/110 mm Hg or higher, are still allowed before treatment is considered,” Dr. Garovic said.

“This study shows that as soon as you reach that level, treatment with oral nifedipine should be initiated and that timely initiation of oral nifedipine may optimize blood pressure control and decrease the need for intravenous therapy subsequently, and that has good effects on the mother without adversely affecting the baby,” Dr. Garovic said.

“This is potentially practice changing,” Dr. Garovic added. “But the elephant in the room is the question of why we are waiting for blood pressure to reach such dangerous levels before initiating treatment, and whether initiating treatment at a blood pressure of 140/90 or higher may prevent blood pressure reaching these high levels and women developing complications that are the consequence of severe hypertension.”

The study was funded by the Ohio State University’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Dr. Cleary and Dr. Garovic have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HYPERTENSION

Key Data on Comorbidities in Type 2 Diabetes From EASD 2022

Key data on chronic conditions in type 2 diabetes, presented at the 2022 European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), are discussed by Dr Carol Wysham, from the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Focusing on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Dr Wysham reports on a large national registry out of Sweden that explored the rates of microvascular complications in patients with NAFLD. The study showed that NAFLD is independently associated with chronic kidney disease and retinopathy. Coupling the findings with the rise in diabetes risk per population, the presence of NAFLD may represent an additional risk factor for microvascular complications.

Next, Dr Wysham comments on another large, real-world study using data from the UK National Health Service (NHS), investigating a scoring system for noninvasive fibrosis, which the study concludes is a promising prognostic biomarker of liver and cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes.

She then turns to a clinical study that evaluated whether the 2018 EASD/ADA routine treatment recommendation algorithm is associated with decreasing cardiovascular events and death in type 2 diabetes. The study found that nonadherence to the recommendations was associated with an increase in major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality.

--

Carol Wysham, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine; Clinical Endocrinologist, Rockwood Center for Diabetes and Endocrinology, MultiCare Health Systems, Spokane, Washington

Carol Wysham, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Endocrine Society; MultiCare Health Systems

Received research grant from: Allergan; Abbott; Corcept; Eli Lilly; Mylan; Novo Nordisk; Regeneron

Key data on chronic conditions in type 2 diabetes, presented at the 2022 European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), are discussed by Dr Carol Wysham, from the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Focusing on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Dr Wysham reports on a large national registry out of Sweden that explored the rates of microvascular complications in patients with NAFLD. The study showed that NAFLD is independently associated with chronic kidney disease and retinopathy. Coupling the findings with the rise in diabetes risk per population, the presence of NAFLD may represent an additional risk factor for microvascular complications.

Next, Dr Wysham comments on another large, real-world study using data from the UK National Health Service (NHS), investigating a scoring system for noninvasive fibrosis, which the study concludes is a promising prognostic biomarker of liver and cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes.

She then turns to a clinical study that evaluated whether the 2018 EASD/ADA routine treatment recommendation algorithm is associated with decreasing cardiovascular events and death in type 2 diabetes. The study found that nonadherence to the recommendations was associated with an increase in major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality.

--

Carol Wysham, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine; Clinical Endocrinologist, Rockwood Center for Diabetes and Endocrinology, MultiCare Health Systems, Spokane, Washington

Carol Wysham, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Endocrine Society; MultiCare Health Systems

Received research grant from: Allergan; Abbott; Corcept; Eli Lilly; Mylan; Novo Nordisk; Regeneron

Key data on chronic conditions in type 2 diabetes, presented at the 2022 European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), are discussed by Dr Carol Wysham, from the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Focusing on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), Dr Wysham reports on a large national registry out of Sweden that explored the rates of microvascular complications in patients with NAFLD. The study showed that NAFLD is independently associated with chronic kidney disease and retinopathy. Coupling the findings with the rise in diabetes risk per population, the presence of NAFLD may represent an additional risk factor for microvascular complications.

Next, Dr Wysham comments on another large, real-world study using data from the UK National Health Service (NHS), investigating a scoring system for noninvasive fibrosis, which the study concludes is a promising prognostic biomarker of liver and cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes.

She then turns to a clinical study that evaluated whether the 2018 EASD/ADA routine treatment recommendation algorithm is associated with decreasing cardiovascular events and death in type 2 diabetes. The study found that nonadherence to the recommendations was associated with an increase in major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality.

--

Carol Wysham, MD, Clinical Professor of Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Washington School of Medicine; Clinical Endocrinologist, Rockwood Center for Diabetes and Endocrinology, MultiCare Health Systems, Spokane, Washington

Carol Wysham, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant, or trustee for: Endocrine Society; MultiCare Health Systems

Received research grant from: Allergan; Abbott; Corcept; Eli Lilly; Mylan; Novo Nordisk; Regeneron

Ultra-processed food intake by moms linked with childhood obesity

A mother’s consumption of ultra-processed foods appears to be related to an increased risk of overweight or obesity in her children, according to new research.

Among the 19,958 mother-child pairs studied, 12.4% of children developed obesity or overweight in the full analytic study group, and the offspring of those mothers who ate the most ultra-processed foods had a 26% higher risk of obesity/overweight (12.1 servings/day), compared with those with the lowest consumption (3.4 servings/day), report Andrew T. Chan, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues.

This study demonstrates the possible advantages of restricting ultra-processed food consumption among women and mothers who are in their reproductive years to potentially lower the risk of childhood obesity, the investigators note.

“These data support the importance of refining dietary recommendations and the development of programs to improve nutrition for women of reproductive age to promote offspring health,” they write in their article, published in BMJ.

“As a medical and public health community, we have to understand that the period of time in which a woman is carrying a child or ... the time when she is raising her children represents a unique opportunity to potentially intervene to affect both the health of the mother and also the health of the children,” Dr. Chan said in an interview.

It is important to address these trends both on an individual clinician level and on a societal level, noted Dr. Chan.