User login

Thoracic Oncology and Chest Procedures Network

Pleural Disease Section

Aspirate or wait: changing the paradigm for PSP care

Although observation for small asymptomatic PSP is supported by current guidelines, management recommendations for larger PSP remains unclear (MacDuff, et al. Thorax. 2010;65[Suppl 2]:ii18-ii31; Tschopp JM, et al. Eur Respir J. 2015;46[2]:321). Two recent RCTs explore conservative vs intervention-based management in those with larger or symptomatic PSP. In the PSP trial, Brown and colleagues prospectively randomized 316 patients with moderate to large PSP to either conservative management (≥ 4 hour observation) or small-bore chest tube without suction (Brown, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382[5]:405). Although noninferiority criteria were met, the primary outcome of radiographic resolution of pneumothorax within 8 weeks of randomization was not statistically robust to conservative assumptions about missing data. They concluded that conservative management was noninferior to intervention, and it resulted in a lower risk of serious adverse events or PSP recurrence than interventional management. The multicenter randomized Ambulatory Management of Primary Pneumothorax (RAMPP) trial compared ambulatory management of PSP using an 8F drainage device to a guideline-driven approach (drainage, aspiration, or both) amongst 236 patients with symptomatic PSP. Intervention shortened length of hospital stay (median 0 vs 4 days, P<.0001), but the intervention arm experienced more adverse events (including enlargement of pneumothorax, as well as device malfunction) (Hallifax RJ, et al. Lancet. 2020;396[10243]:39). These two trials challenge the current guidelines for management for patients with PSP, but both had limitations. Though more data are needed to establish a clear consensus, these studies suggest that a conservative pathway for PSP warrants further consideration.

Tejaswi R. Nadig, MBBS

Member-at-Large

Yaron Gesthalter, MD

Member-at-Large

Priya P. Nath, MD

Member-at-Large

Pleural Disease Section

Aspirate or wait: changing the paradigm for PSP care

Although observation for small asymptomatic PSP is supported by current guidelines, management recommendations for larger PSP remains unclear (MacDuff, et al. Thorax. 2010;65[Suppl 2]:ii18-ii31; Tschopp JM, et al. Eur Respir J. 2015;46[2]:321). Two recent RCTs explore conservative vs intervention-based management in those with larger or symptomatic PSP. In the PSP trial, Brown and colleagues prospectively randomized 316 patients with moderate to large PSP to either conservative management (≥ 4 hour observation) or small-bore chest tube without suction (Brown, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382[5]:405). Although noninferiority criteria were met, the primary outcome of radiographic resolution of pneumothorax within 8 weeks of randomization was not statistically robust to conservative assumptions about missing data. They concluded that conservative management was noninferior to intervention, and it resulted in a lower risk of serious adverse events or PSP recurrence than interventional management. The multicenter randomized Ambulatory Management of Primary Pneumothorax (RAMPP) trial compared ambulatory management of PSP using an 8F drainage device to a guideline-driven approach (drainage, aspiration, or both) amongst 236 patients with symptomatic PSP. Intervention shortened length of hospital stay (median 0 vs 4 days, P<.0001), but the intervention arm experienced more adverse events (including enlargement of pneumothorax, as well as device malfunction) (Hallifax RJ, et al. Lancet. 2020;396[10243]:39). These two trials challenge the current guidelines for management for patients with PSP, but both had limitations. Though more data are needed to establish a clear consensus, these studies suggest that a conservative pathway for PSP warrants further consideration.

Tejaswi R. Nadig, MBBS

Member-at-Large

Yaron Gesthalter, MD

Member-at-Large

Priya P. Nath, MD

Member-at-Large

Pleural Disease Section

Aspirate or wait: changing the paradigm for PSP care

Although observation for small asymptomatic PSP is supported by current guidelines, management recommendations for larger PSP remains unclear (MacDuff, et al. Thorax. 2010;65[Suppl 2]:ii18-ii31; Tschopp JM, et al. Eur Respir J. 2015;46[2]:321). Two recent RCTs explore conservative vs intervention-based management in those with larger or symptomatic PSP. In the PSP trial, Brown and colleagues prospectively randomized 316 patients with moderate to large PSP to either conservative management (≥ 4 hour observation) or small-bore chest tube without suction (Brown, et al. N Engl J Med. 2020;382[5]:405). Although noninferiority criteria were met, the primary outcome of radiographic resolution of pneumothorax within 8 weeks of randomization was not statistically robust to conservative assumptions about missing data. They concluded that conservative management was noninferior to intervention, and it resulted in a lower risk of serious adverse events or PSP recurrence than interventional management. The multicenter randomized Ambulatory Management of Primary Pneumothorax (RAMPP) trial compared ambulatory management of PSP using an 8F drainage device to a guideline-driven approach (drainage, aspiration, or both) amongst 236 patients with symptomatic PSP. Intervention shortened length of hospital stay (median 0 vs 4 days, P<.0001), but the intervention arm experienced more adverse events (including enlargement of pneumothorax, as well as device malfunction) (Hallifax RJ, et al. Lancet. 2020;396[10243]:39). These two trials challenge the current guidelines for management for patients with PSP, but both had limitations. Though more data are needed to establish a clear consensus, these studies suggest that a conservative pathway for PSP warrants further consideration.

Tejaswi R. Nadig, MBBS

Member-at-Large

Yaron Gesthalter, MD

Member-at-Large

Priya P. Nath, MD

Member-at-Large

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Expert review of management of subepithelial lesions

The proper management of subepithelial lesions (SELs) depends on the size, histopathology, malignant potential, and presence of symptoms, according to a new American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“SELs are found in 1 in every 300 endoscopies, and two-thirds of these lesions are located in the stomach,” explained Kaveh Sharzehi, MD, an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues. “They represent a heterogeneous group of lesions including nonneoplastic lesions such as ectopic pancreatic tissue and neoplastic lesions. The neoplastic SELs can vary from lesions with no malignant potential such as lipomas to those with malignant potential such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). The majority of SELs are small and found incidentally.”

The authors developed 10 clinical practice advice statements on the diagnosis and management of subepithelial lesions based on a review of the published literature and expert opinion.

First, standard mucosal biopsies often don’t reach deep enough to obtain a pathologic diagnosis for SELs because the lesions have normal overlying mucosa. Forceps bite-on-bite/deep-well biopsies or tunnel biopsies may help to establish a pathologic diagnosis.

Used as an adjunct to standard endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has become the primary method for determining diagnostic and prognostic characteristics of SELs – such as the layer of origin, echogenicity, and presence of blood vessels within the lesion. It can also help with tissue acquisition.

For SELs arising from the submucosa, EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration and fine-needle biopsy have evolved as widely used methods for obtaining tissue. For SELs arising from muscularis propria, fine-needle aspiration and fine-needle biopsy should be used to determine whether the lesion is a GIST or leiomyoma. Using structural assessment and staining will allow for the differentiation of mesenchymal tumors and assessment of their malignant potential.

To remove SELs, multiple endoscopic resection techniques may be appropriate, depending on the layer of origin, size, and location, with the goal of complete, en bloc resection with no disruption to the wall or capsule of the lesion. These techniques should be limited to endoscopists skilled in advanced tissue resection.

SELs without malignant potential, such as lipoma or pancreatic rest, don’t need further evaluation or surveillance.

SELs that are ulcerated, bleeding, or causing symptoms should be considered for resection.

Other lesions are managed with resection or surveillance based on pathology. For example, leiomyomas, which are benign and most often found in the esophagus, generally don’t require surveillance or resection. On the other hand, all GISTs have some malignant potential, and management varies by size, location, and presence of symptoms. GISTs larger than 2 cm, should be considered for resection. Some GISTs between 2 cm and 4 cm without high-risk features can be removed by using advanced endoscopic resection techniques.

The determination for resection in all cases should include a multidisciplinary approach, with confirmation of a low mitotic index and lack of metastatic disease on cross-sectional imaging.

“The ultimate goal of endoscopic resection is to have a complete resection,” the authors wrote. “Determining the layer of involvement by EUS is critical in planning resection techniques.”

The authors reported no grant support or funding sources for this report. One author serves as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Fujifilm, Intuitive Surgical, Medtronic, and Olympus. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

The proper management of subepithelial lesions (SELs) depends on the size, histopathology, malignant potential, and presence of symptoms, according to a new American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“SELs are found in 1 in every 300 endoscopies, and two-thirds of these lesions are located in the stomach,” explained Kaveh Sharzehi, MD, an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues. “They represent a heterogeneous group of lesions including nonneoplastic lesions such as ectopic pancreatic tissue and neoplastic lesions. The neoplastic SELs can vary from lesions with no malignant potential such as lipomas to those with malignant potential such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). The majority of SELs are small and found incidentally.”

The authors developed 10 clinical practice advice statements on the diagnosis and management of subepithelial lesions based on a review of the published literature and expert opinion.

First, standard mucosal biopsies often don’t reach deep enough to obtain a pathologic diagnosis for SELs because the lesions have normal overlying mucosa. Forceps bite-on-bite/deep-well biopsies or tunnel biopsies may help to establish a pathologic diagnosis.

Used as an adjunct to standard endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has become the primary method for determining diagnostic and prognostic characteristics of SELs – such as the layer of origin, echogenicity, and presence of blood vessels within the lesion. It can also help with tissue acquisition.

For SELs arising from the submucosa, EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration and fine-needle biopsy have evolved as widely used methods for obtaining tissue. For SELs arising from muscularis propria, fine-needle aspiration and fine-needle biopsy should be used to determine whether the lesion is a GIST or leiomyoma. Using structural assessment and staining will allow for the differentiation of mesenchymal tumors and assessment of their malignant potential.

To remove SELs, multiple endoscopic resection techniques may be appropriate, depending on the layer of origin, size, and location, with the goal of complete, en bloc resection with no disruption to the wall or capsule of the lesion. These techniques should be limited to endoscopists skilled in advanced tissue resection.

SELs without malignant potential, such as lipoma or pancreatic rest, don’t need further evaluation or surveillance.

SELs that are ulcerated, bleeding, or causing symptoms should be considered for resection.

Other lesions are managed with resection or surveillance based on pathology. For example, leiomyomas, which are benign and most often found in the esophagus, generally don’t require surveillance or resection. On the other hand, all GISTs have some malignant potential, and management varies by size, location, and presence of symptoms. GISTs larger than 2 cm, should be considered for resection. Some GISTs between 2 cm and 4 cm without high-risk features can be removed by using advanced endoscopic resection techniques.

The determination for resection in all cases should include a multidisciplinary approach, with confirmation of a low mitotic index and lack of metastatic disease on cross-sectional imaging.

“The ultimate goal of endoscopic resection is to have a complete resection,” the authors wrote. “Determining the layer of involvement by EUS is critical in planning resection techniques.”

The authors reported no grant support or funding sources for this report. One author serves as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Fujifilm, Intuitive Surgical, Medtronic, and Olympus. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

The proper management of subepithelial lesions (SELs) depends on the size, histopathology, malignant potential, and presence of symptoms, according to a new American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

“SELs are found in 1 in every 300 endoscopies, and two-thirds of these lesions are located in the stomach,” explained Kaveh Sharzehi, MD, an associate professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, and colleagues. “They represent a heterogeneous group of lesions including nonneoplastic lesions such as ectopic pancreatic tissue and neoplastic lesions. The neoplastic SELs can vary from lesions with no malignant potential such as lipomas to those with malignant potential such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). The majority of SELs are small and found incidentally.”

The authors developed 10 clinical practice advice statements on the diagnosis and management of subepithelial lesions based on a review of the published literature and expert opinion.

First, standard mucosal biopsies often don’t reach deep enough to obtain a pathologic diagnosis for SELs because the lesions have normal overlying mucosa. Forceps bite-on-bite/deep-well biopsies or tunnel biopsies may help to establish a pathologic diagnosis.

Used as an adjunct to standard endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has become the primary method for determining diagnostic and prognostic characteristics of SELs – such as the layer of origin, echogenicity, and presence of blood vessels within the lesion. It can also help with tissue acquisition.

For SELs arising from the submucosa, EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration and fine-needle biopsy have evolved as widely used methods for obtaining tissue. For SELs arising from muscularis propria, fine-needle aspiration and fine-needle biopsy should be used to determine whether the lesion is a GIST or leiomyoma. Using structural assessment and staining will allow for the differentiation of mesenchymal tumors and assessment of their malignant potential.

To remove SELs, multiple endoscopic resection techniques may be appropriate, depending on the layer of origin, size, and location, with the goal of complete, en bloc resection with no disruption to the wall or capsule of the lesion. These techniques should be limited to endoscopists skilled in advanced tissue resection.

SELs without malignant potential, such as lipoma or pancreatic rest, don’t need further evaluation or surveillance.

SELs that are ulcerated, bleeding, or causing symptoms should be considered for resection.

Other lesions are managed with resection or surveillance based on pathology. For example, leiomyomas, which are benign and most often found in the esophagus, generally don’t require surveillance or resection. On the other hand, all GISTs have some malignant potential, and management varies by size, location, and presence of symptoms. GISTs larger than 2 cm, should be considered for resection. Some GISTs between 2 cm and 4 cm without high-risk features can be removed by using advanced endoscopic resection techniques.

The determination for resection in all cases should include a multidisciplinary approach, with confirmation of a low mitotic index and lack of metastatic disease on cross-sectional imaging.

“The ultimate goal of endoscopic resection is to have a complete resection,” the authors wrote. “Determining the layer of involvement by EUS is critical in planning resection techniques.”

The authors reported no grant support or funding sources for this report. One author serves as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Fujifilm, Intuitive Surgical, Medtronic, and Olympus. The remaining authors disclosed no conflicts.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Unusual Bilateral Distribution of Neurofibromatosis Type 5 on the Distal Upper Extremities

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

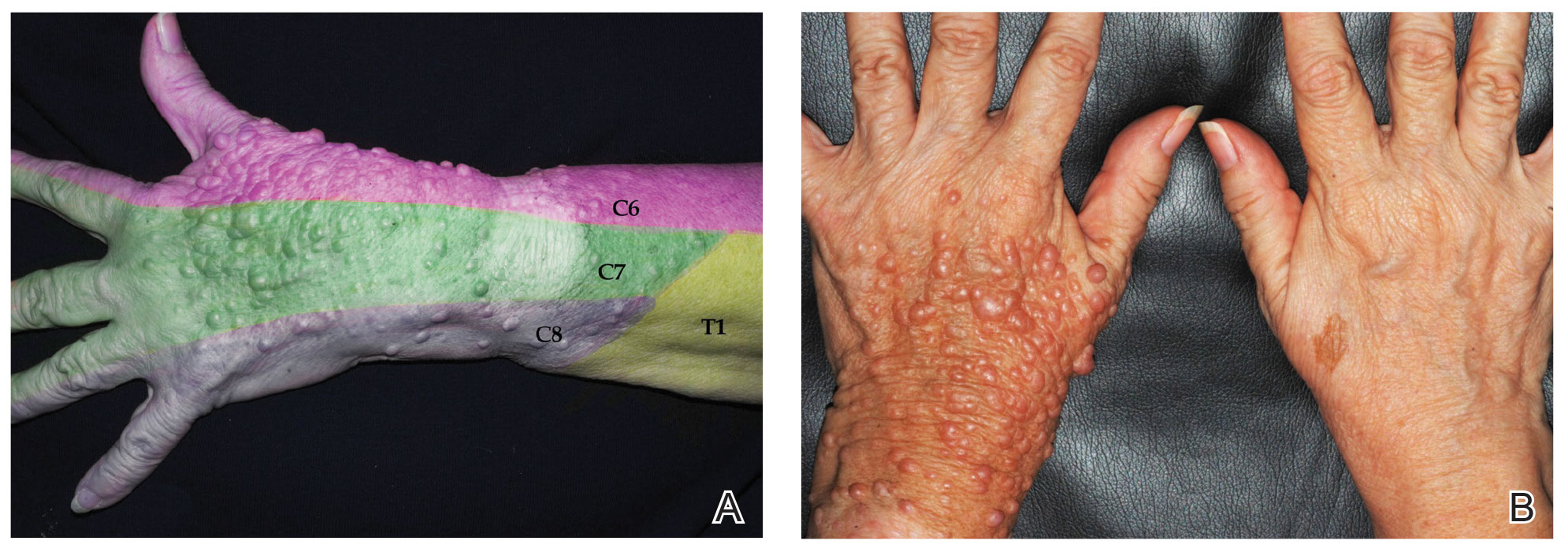

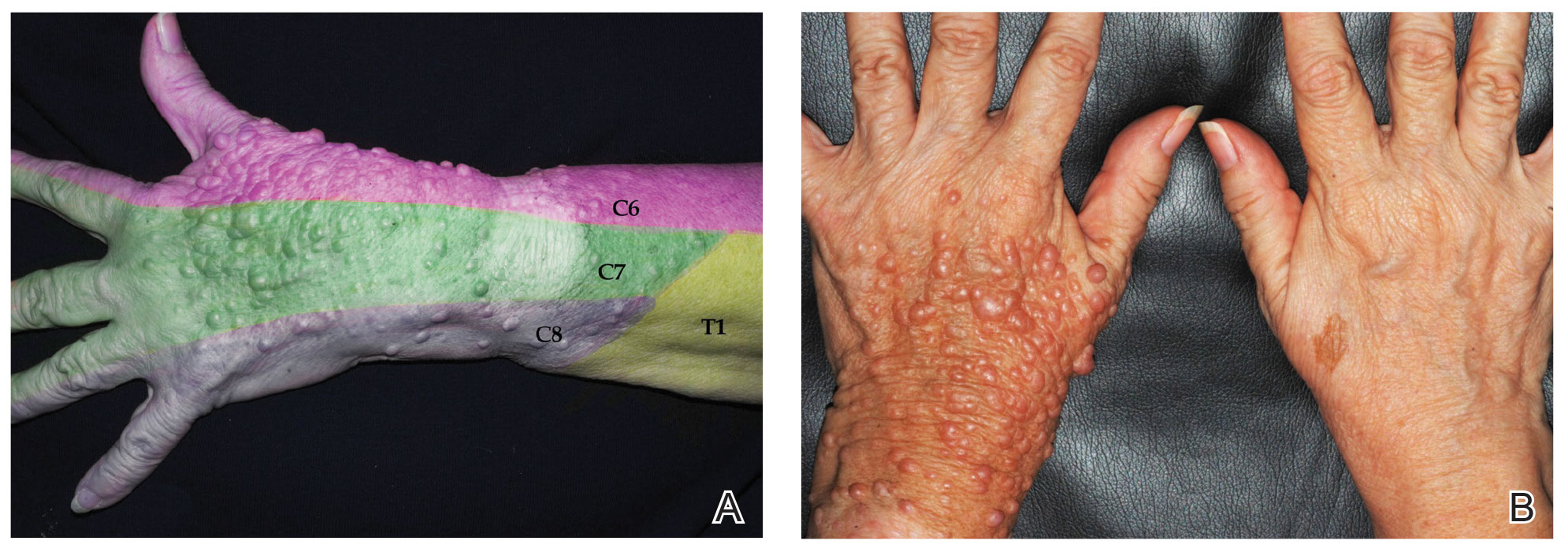

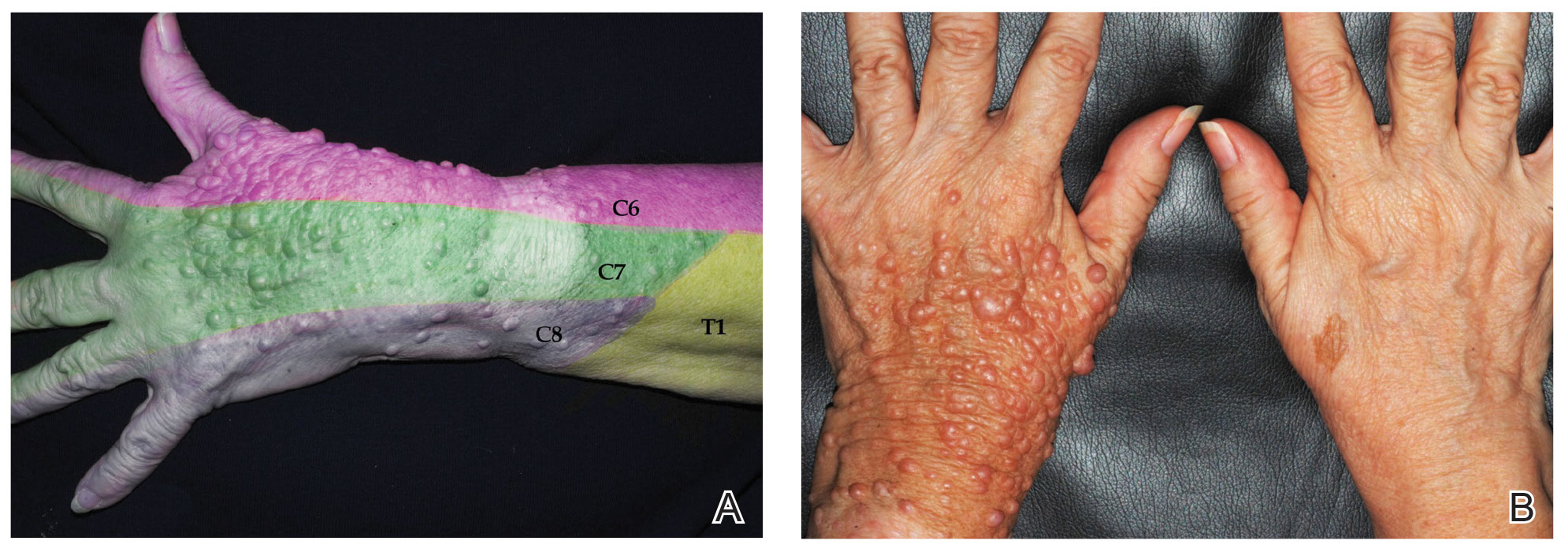

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

To the Editor:

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease). Phenotypic manifestations of NF5 include café-au-lait macules, neurofibromas, or both in 1 or more adjacent dermatomes. In contrast to the systemic features of NF1, the dermatomal distribution of NF5 demonstrates mosaicism due to a spontaneous postzygotic mutation in the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. We describe an atypical presentation of NF5 with bilateral features on the upper extremities.

A 74-year-old woman presented with soft pink- to flesh-colored growths on the left dorsal forearm and hand that were observed incidentally during a Mohs procedure for treatment of a basal cell carcinoma on the upper cutaneous lip. The patient reported that the lesions initially appeared on the left dorsal hand at approximately 16 years of age and had since spread proximally up to the mid dorsal forearm over the course of her lifetime. She denied any pain but claimed the affected area could be itchy. The lesions did not interfere with her daily activities, but they negatively impacted her social life due to their cosmetic appearance as well as her fear that they could be contagious. She denied any family history of NF1.

Physical examination revealed innumerable soft, pink- to flesh-colored cutaneous nodules ranging from 3 to 9 mm in diameter clustered uniformly on the left dorsal hand and lower forearm within the C6, C7, and C8 dermatomal regions (Figure, A). A singular brown patch measuring 20 mm in diameter also was observed on the right dorsal hand within the C6 dermatome, which the patient reported had been present since birth (Figure, B). The nodules and pigmented patch were clinically diagnosed as cutaneous neurofibromas on the left arm and a café-au-lait macule on the right arm, each manifesting within the C6 dermatome on separate upper extremities. Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, and acoustic schwannomas were not observed. Because of the dermatomal distribution of the lesions and lack of family history of NF1, a diagnosis of bilateral NF5 was made. The patient stated she had declined treatment of the neurofibromas from her referring general dermatologist due to possible risk for recurrence.

Segmental neurofibromatosis was first described in 1931 by Gammel,1 and in 1982, segmental neurofibromatosis was classified as NF5 by Riccardi.2 After Tinschert et al3 later demonstrated NF5 to be a somatic mutation of NF1,3 Ruggieri and Huson4 proposed the term mosaic neurofibromatosis 1 in 2001.

While the prevalence of NF1 is 1 in 3000 individuals,5 NF5 is rare with an occurrence of 1 in 40,000.6 In NF5, a spontaneous NF1 gene mutation occurs on chromosome 17 in a dividing cell after conception.7 Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the NF1 gene.8 This contrasts with the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells. Patients with NF5 generally are not expected to have affected offspring because the spontaneous mutation usually arises in somatic cells; however, a postzygotic mutation in the gonadal region could potentially affect germline cells, resulting in vertical transmission, with documented cases of offspring with systemic NF1.4 Because of the risk for malignancy with systemic neurofibromatosis, early diagnosis with genetic counseling is imperative in patients with both NF1 and NF5.

Neurofibromatosis type 5 is a clinical diagnosis based on the presence of neurofibromas and/or café-au-lait macules in a dermatomal distribution. The clinical presentation depends on when and where the NF1 gene mutation occurs in utero as cells multiply, differentiate, and migrate.8 Earlier mutations result in a broader manifestation of NF5 in comparison to late mutations, which have more localized features. An NF1 gene mutation causes a loss of function of neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein, in Schwann cells and fibroblasts.8 This produces neurofibromas and café-au-lait macules, respectively.8

A large literature review on segmental neurofibromatosis by Garcia-Romero et al6 identified 320 individuals who did not meet full inclusion criteria for NF1 between 1977 and 2012. Overall, 76% of cases were unilaterally distributed. The investigators identified 157 individual case reports in which the most to least common presentation was pigmentary changes only, neurofibromas only, mixed pigmentary changes with neurofibromas, and plexiform neurofibromas only; however, many of these cases were children who may have later developed both neurofibromas and pigmentary changes during puberty.6 Additional features of NF5 may include freckling, Lisch nodules, optic gliomas, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, skeletal abnormalities, precocious puberty, vascular malformations, hypertension, seizures, and/or learning difficulties based on the affected anatomy.

Segmental neurofibromatosis, or NF5, is a rare subtype of NF1. Our case demonstrates an unusual bilateral distribution of NF5 with cutaneous neurofibromas and a café-au-lait macule on the upper extremities. Awareness of variations of neurofibromatosis and their genetic implications is essential in establishing earlier clinical diagnoses in cases with subtle manifestations.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

- Gammel JA. Localized neurofibromatosis. Arch Dermatol. 1931;24:712-713.

- Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis: clinical heterogeneity. Curr Probl Cancer. 1982;7:1-34.

- Tinschert S, Naumann I, Stegmann E, et al. Segmental neurofibromatosis is caused by somatic mutation of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:455-459.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Crowe FW, Schull WJ, Neel JV. A Clinical, Pathological and Genetic Study of Multiple Neurofibromatosis. Charles C Thomas; 1956.

- García-Romero MT, Parkin P, Lara-Corrales I. Mosaic neurofibromatosis type 1: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:9-17.

- Ledbetter DH, Rich DC, O’Connell P, et al. Precise localization of NF1 to 17q11.2 by balanced translocation. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:20-24.

- Redlick FP, Shaw JC. Segmental neurofibromatosis follows Blaschko’s lines or dermatomes depending on the cell line affected: case report and literature review. J Cutan Med Surg. 2004;8:353-356.

Practice Points

- Segmental neurofibromatosis, or neurofibromatosis type 5 (NF5), is a rare subtype of neurofibromatosistype 1 (NF1)(also known as von Recklinghausen disease).

- Individuals with NF5 are born mosaic with 2 genotypes—one normal and one abnormal—for the neurofibromin 1 gene, NF1. This is in contrast to the autosomal-dominant and systemic characteristics of NF1, which has the NF1 gene mutation in all cells.

What role does the uterine microbiome play in fertility?

Until the second half of the 20th century, it was believed that the uterine cavity was sterile. Since then, technological advances have provided insight into the nature of the microbiome throughout the female reproductive tract. The role of these microorganisms on the fertility of women of reproductive age has been the subject of research. Is there an “optimal microbiome” for fertility? Can changing the microbiome of the uterine cavity affect fertility? There is still no definitive scientific response to these questions.

Several studies describe the healthy state of the uterine microbiota in women of reproductive age, with most of these studies reporting dominance of Lactobacillus species. However, by contrast, some studies did not observe Lactobacillus predominance inside the uterine cavity in cases of healthy uterine microbiomes. The presence of other microorganisms, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, was associated with reduced success in patients attempting in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, such as, for example, embryo implantation failure and miscarriage.

It is also possible that a physiologic endometrial microbiome could be considered healthy despite a minor presence of pathogenic bacteria. Importantly, responses from the host also modulate many aspects of human conception. These shifts correlate with parameters such as age, hormonal changes, ethnicity, sexual activity, and intrauterine devices.

Carlos Simón, MD, PhD, is a gynecologist and obstetrician and professor at the University of Valencia in Valencia, Spain; Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.; and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He was in São Paulo at the time of the XXVI Brazilian Congress of Assisted Reproduction and agreed to be interviewed by Medscape Portuguese Edition. Dr. Simón, who is Spanish and is an international reference in uterine microbiome studies, created an endometrial receptivity analysis (ERA).

“What we know is that the human uterus has its own microbiome. Thanks to next-generation sequencing (NGS), we can detect microbial DNA. We’re talking about a microbiome that, if changed, affects [embryo] implantation. We have identified that Lactobacilli are the good [microorganisms], but if there are Streptococci, Gardnerella, or other bacteria, the implantation [of the embryo] is affected.”

In 2018, Dr. Simón’s team published a pilot study assessing the microbiome of 30 patients during fertilization treatment. It was observed that, when there is a change in the microbiome, the implantation rate drops to half and the miscarriage rate doubles.

Following this study, also in 2018, the team published a multicenter, prospective, observational study. A 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing technique was used to analyze endometrial fluid and biopsy samples before embryo transfer in a cohort of 342 infertile patients asymptomatic for infection. Participants underwent fertilization procedures in 13 centers on three continents.

A dysbiotic endometrial microbiota profile composed of Atopobium, Bifidobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Gardnerella, Haemophilus, Klebsiella, Neisseria, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus was associated with unsuccessful outcomes. In contrast, Lactobacillus was consistently enriched in patients with live birth outcomes. The authors concluded that endometrial microbiota composition before embryo transfer is a useful biomarker to predict reproductive outcome.

“You see a microbial signature in patients who become pregnant, another in those who do not become pregnant, and yet another in those who miscarry,” Dr. Simón summarized. “By knowing this signature, the microbiome can be analyzed and treated so that it is stabilized before the embryo is transferred.”

What should be done?

Endometrial microbiome profiles do not use microbial cultures. They are obtained by NGS of the endometrial sample. This is because the 16S rRNA gene, which can be found in bacteria, presents hypervariable regions that serve as markers to identify the bacteria present.

If a microbiome is found to be somewhat unhealthy, it is theoretically possible to change its composition, increasing the chances of successful assisted reproduction. The administration of antibiotics and vaginal probiotics are two treatment approaches.

According to Dr. Simón, treatment is specific to the bacterium (metronidazole, and, if that fails, rifampicin for Gardnerella, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for Streptococci). Once the pathogenic bacterium has been treated, the probiotics can be administered. “If all is well, we can then go ahead with the procedure,” he explained.

Dr. Simón pointed out that, with respect to treatment, knowledge is still limited and primarily based on case reports. “You look for issues in the microbiome when the patient experiences reproductive failure and there are no other causes,” he emphasized. “Microbiology plays a role in reproduction, affecting the human uterus. It’s good to know about it to improve reproductive outcomes. When there are repeated [embryo] implantation failures, we suggest an endometrial biopsy to identify the implantation window and determine whether the uterine microbiome is healthy or not. And if there are any abnormalities in the microbiome, they can be treated.”

There are still many open questions, such as how long the “good microbiome” lasts after antibiotic therapy. “We suggest checking the microbiome after [antibiotic] treatment and before implanting the embryo,” said Dr. Simón.

Although there is no consensus on how the endometrial microbiota relate to reproductive outcomes, the analysis and change in microbiome are already being offered in clinical practice as a way to increase the chances of conception. Márcia Riboldi, PhD, a genetics specialist serving as Country Manager for Igenomix Brasil and Argentina, the company that offers the analyses, provides an idea of the market for such analyses in Brazil. “We perform approximately 500 analyses per month,” she said, adding that most patients have a history of [embryo] implantation failure or miscarriage.

Matheus Roque, MD, PhD, an IVF specialist, shared two IVF case reports from the Mater Prime Human Reproduction Clinic in the southern region of the city of São Paulo. He emphasized that the decision to perform a microbiome analysis was made only after repeated implantation failure.

“With the outcomes the doctors started to see, the paradigm started to shift,” said Dr. Riboldi. “Why wait for the patient to have [an embryo] transfer failure? Let’s study the endometrium, check the ideal moment for the transfer, see whether it’s receptive or not, if there’s any disease and if there are Lactobacilli,” she proposed. “We need medical training and awareness, and we need to use them appropriately. We have the tests. Doctors need to learn about them and know when and how to use them.” The microbiome analysis costs approximately BRL 2,000, plus expenses for the medical procedure.

Is it too early?

Caio Parente Barbosa, MD, PhD, is an obstetrician/gynecologist specializing in human reproduction, as well as the director general and founder of the Fertile Idea Institute for Reproductive Health. He shared a few of his experiences in an interview with this news organization. “I would say it is still too early to confirm that [the microbiome analysis] produces effective outcomes.”

Dr. Barbosa, who is also provost of graduate studies, research, and innovation of the ABC School of Medicine, Santo André, Brazil, emphasized there is still little global experience with these analyses. “There are doubts worldwide regarding whether these analyses produce effective outcomes. Scientific studies are entirely controversial.”

He stated that some professionals recommend the microbiome analysis for “patients who don’t know what else to do,” but also recognized that there is already a demand for patients who don’t fit this category, who research the analyses on social networks and YouTube. “But it is the smallest of demands. Patients are not as worried about this yet.”

Dr. Barbosa recognized that the idea of an increasingly tailored treatment plan is inevitable. He believes that the study and treatment of the microbiome will become more critical in the future, but he thinks it still “does not offer any value.”

Dr. Barbosa emphasized that the financial side of things must also be considered. “If we add all these tests when investigating a patient’s issues, the treatment becomes ridiculously expensive.” He pointed out that health care professionals need to be careful to perform minimal testing. “We have already added some tests, such as the karyotype test, to the minimal testing for all patients.”

Dr. Simón responded to this criticism, stating: “The cost of repeating cycles is always greater than that of being thorough and knowing what’s going on. Nothing is certain, but if my daughter or wife needed it, I would like to have as much information as possible to make this decision.”

Dr. Barbosa and Dr. Simón reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Riboldi is Country Manager for Igenomix Brasil and Argentina, the company that offers the analyses.

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition and appeared on Medscape.com.

Until the second half of the 20th century, it was believed that the uterine cavity was sterile. Since then, technological advances have provided insight into the nature of the microbiome throughout the female reproductive tract. The role of these microorganisms on the fertility of women of reproductive age has been the subject of research. Is there an “optimal microbiome” for fertility? Can changing the microbiome of the uterine cavity affect fertility? There is still no definitive scientific response to these questions.

Several studies describe the healthy state of the uterine microbiota in women of reproductive age, with most of these studies reporting dominance of Lactobacillus species. However, by contrast, some studies did not observe Lactobacillus predominance inside the uterine cavity in cases of healthy uterine microbiomes. The presence of other microorganisms, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, was associated with reduced success in patients attempting in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, such as, for example, embryo implantation failure and miscarriage.

It is also possible that a physiologic endometrial microbiome could be considered healthy despite a minor presence of pathogenic bacteria. Importantly, responses from the host also modulate many aspects of human conception. These shifts correlate with parameters such as age, hormonal changes, ethnicity, sexual activity, and intrauterine devices.

Carlos Simón, MD, PhD, is a gynecologist and obstetrician and professor at the University of Valencia in Valencia, Spain; Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.; and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He was in São Paulo at the time of the XXVI Brazilian Congress of Assisted Reproduction and agreed to be interviewed by Medscape Portuguese Edition. Dr. Simón, who is Spanish and is an international reference in uterine microbiome studies, created an endometrial receptivity analysis (ERA).

“What we know is that the human uterus has its own microbiome. Thanks to next-generation sequencing (NGS), we can detect microbial DNA. We’re talking about a microbiome that, if changed, affects [embryo] implantation. We have identified that Lactobacilli are the good [microorganisms], but if there are Streptococci, Gardnerella, or other bacteria, the implantation [of the embryo] is affected.”

In 2018, Dr. Simón’s team published a pilot study assessing the microbiome of 30 patients during fertilization treatment. It was observed that, when there is a change in the microbiome, the implantation rate drops to half and the miscarriage rate doubles.

Following this study, also in 2018, the team published a multicenter, prospective, observational study. A 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing technique was used to analyze endometrial fluid and biopsy samples before embryo transfer in a cohort of 342 infertile patients asymptomatic for infection. Participants underwent fertilization procedures in 13 centers on three continents.

A dysbiotic endometrial microbiota profile composed of Atopobium, Bifidobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Gardnerella, Haemophilus, Klebsiella, Neisseria, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus was associated with unsuccessful outcomes. In contrast, Lactobacillus was consistently enriched in patients with live birth outcomes. The authors concluded that endometrial microbiota composition before embryo transfer is a useful biomarker to predict reproductive outcome.

“You see a microbial signature in patients who become pregnant, another in those who do not become pregnant, and yet another in those who miscarry,” Dr. Simón summarized. “By knowing this signature, the microbiome can be analyzed and treated so that it is stabilized before the embryo is transferred.”

What should be done?

Endometrial microbiome profiles do not use microbial cultures. They are obtained by NGS of the endometrial sample. This is because the 16S rRNA gene, which can be found in bacteria, presents hypervariable regions that serve as markers to identify the bacteria present.

If a microbiome is found to be somewhat unhealthy, it is theoretically possible to change its composition, increasing the chances of successful assisted reproduction. The administration of antibiotics and vaginal probiotics are two treatment approaches.

According to Dr. Simón, treatment is specific to the bacterium (metronidazole, and, if that fails, rifampicin for Gardnerella, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for Streptococci). Once the pathogenic bacterium has been treated, the probiotics can be administered. “If all is well, we can then go ahead with the procedure,” he explained.

Dr. Simón pointed out that, with respect to treatment, knowledge is still limited and primarily based on case reports. “You look for issues in the microbiome when the patient experiences reproductive failure and there are no other causes,” he emphasized. “Microbiology plays a role in reproduction, affecting the human uterus. It’s good to know about it to improve reproductive outcomes. When there are repeated [embryo] implantation failures, we suggest an endometrial biopsy to identify the implantation window and determine whether the uterine microbiome is healthy or not. And if there are any abnormalities in the microbiome, they can be treated.”

There are still many open questions, such as how long the “good microbiome” lasts after antibiotic therapy. “We suggest checking the microbiome after [antibiotic] treatment and before implanting the embryo,” said Dr. Simón.

Although there is no consensus on how the endometrial microbiota relate to reproductive outcomes, the analysis and change in microbiome are already being offered in clinical practice as a way to increase the chances of conception. Márcia Riboldi, PhD, a genetics specialist serving as Country Manager for Igenomix Brasil and Argentina, the company that offers the analyses, provides an idea of the market for such analyses in Brazil. “We perform approximately 500 analyses per month,” she said, adding that most patients have a history of [embryo] implantation failure or miscarriage.

Matheus Roque, MD, PhD, an IVF specialist, shared two IVF case reports from the Mater Prime Human Reproduction Clinic in the southern region of the city of São Paulo. He emphasized that the decision to perform a microbiome analysis was made only after repeated implantation failure.

“With the outcomes the doctors started to see, the paradigm started to shift,” said Dr. Riboldi. “Why wait for the patient to have [an embryo] transfer failure? Let’s study the endometrium, check the ideal moment for the transfer, see whether it’s receptive or not, if there’s any disease and if there are Lactobacilli,” she proposed. “We need medical training and awareness, and we need to use them appropriately. We have the tests. Doctors need to learn about them and know when and how to use them.” The microbiome analysis costs approximately BRL 2,000, plus expenses for the medical procedure.

Is it too early?

Caio Parente Barbosa, MD, PhD, is an obstetrician/gynecologist specializing in human reproduction, as well as the director general and founder of the Fertile Idea Institute for Reproductive Health. He shared a few of his experiences in an interview with this news organization. “I would say it is still too early to confirm that [the microbiome analysis] produces effective outcomes.”

Dr. Barbosa, who is also provost of graduate studies, research, and innovation of the ABC School of Medicine, Santo André, Brazil, emphasized there is still little global experience with these analyses. “There are doubts worldwide regarding whether these analyses produce effective outcomes. Scientific studies are entirely controversial.”

He stated that some professionals recommend the microbiome analysis for “patients who don’t know what else to do,” but also recognized that there is already a demand for patients who don’t fit this category, who research the analyses on social networks and YouTube. “But it is the smallest of demands. Patients are not as worried about this yet.”

Dr. Barbosa recognized that the idea of an increasingly tailored treatment plan is inevitable. He believes that the study and treatment of the microbiome will become more critical in the future, but he thinks it still “does not offer any value.”

Dr. Barbosa emphasized that the financial side of things must also be considered. “If we add all these tests when investigating a patient’s issues, the treatment becomes ridiculously expensive.” He pointed out that health care professionals need to be careful to perform minimal testing. “We have already added some tests, such as the karyotype test, to the minimal testing for all patients.”

Dr. Simón responded to this criticism, stating: “The cost of repeating cycles is always greater than that of being thorough and knowing what’s going on. Nothing is certain, but if my daughter or wife needed it, I would like to have as much information as possible to make this decision.”

Dr. Barbosa and Dr. Simón reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Riboldi is Country Manager for Igenomix Brasil and Argentina, the company that offers the analyses.

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition and appeared on Medscape.com.

Until the second half of the 20th century, it was believed that the uterine cavity was sterile. Since then, technological advances have provided insight into the nature of the microbiome throughout the female reproductive tract. The role of these microorganisms on the fertility of women of reproductive age has been the subject of research. Is there an “optimal microbiome” for fertility? Can changing the microbiome of the uterine cavity affect fertility? There is still no definitive scientific response to these questions.

Several studies describe the healthy state of the uterine microbiota in women of reproductive age, with most of these studies reporting dominance of Lactobacillus species. However, by contrast, some studies did not observe Lactobacillus predominance inside the uterine cavity in cases of healthy uterine microbiomes. The presence of other microorganisms, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, was associated with reduced success in patients attempting in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatment, such as, for example, embryo implantation failure and miscarriage.

It is also possible that a physiologic endometrial microbiome could be considered healthy despite a minor presence of pathogenic bacteria. Importantly, responses from the host also modulate many aspects of human conception. These shifts correlate with parameters such as age, hormonal changes, ethnicity, sexual activity, and intrauterine devices.

Carlos Simón, MD, PhD, is a gynecologist and obstetrician and professor at the University of Valencia in Valencia, Spain; Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.; and Baylor College of Medicine, Houston. He was in São Paulo at the time of the XXVI Brazilian Congress of Assisted Reproduction and agreed to be interviewed by Medscape Portuguese Edition. Dr. Simón, who is Spanish and is an international reference in uterine microbiome studies, created an endometrial receptivity analysis (ERA).

“What we know is that the human uterus has its own microbiome. Thanks to next-generation sequencing (NGS), we can detect microbial DNA. We’re talking about a microbiome that, if changed, affects [embryo] implantation. We have identified that Lactobacilli are the good [microorganisms], but if there are Streptococci, Gardnerella, or other bacteria, the implantation [of the embryo] is affected.”

In 2018, Dr. Simón’s team published a pilot study assessing the microbiome of 30 patients during fertilization treatment. It was observed that, when there is a change in the microbiome, the implantation rate drops to half and the miscarriage rate doubles.

Following this study, also in 2018, the team published a multicenter, prospective, observational study. A 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) gene sequencing technique was used to analyze endometrial fluid and biopsy samples before embryo transfer in a cohort of 342 infertile patients asymptomatic for infection. Participants underwent fertilization procedures in 13 centers on three continents.

A dysbiotic endometrial microbiota profile composed of Atopobium, Bifidobacterium, Chryseobacterium, Gardnerella, Haemophilus, Klebsiella, Neisseria, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus was associated with unsuccessful outcomes. In contrast, Lactobacillus was consistently enriched in patients with live birth outcomes. The authors concluded that endometrial microbiota composition before embryo transfer is a useful biomarker to predict reproductive outcome.

“You see a microbial signature in patients who become pregnant, another in those who do not become pregnant, and yet another in those who miscarry,” Dr. Simón summarized. “By knowing this signature, the microbiome can be analyzed and treated so that it is stabilized before the embryo is transferred.”

What should be done?

Endometrial microbiome profiles do not use microbial cultures. They are obtained by NGS of the endometrial sample. This is because the 16S rRNA gene, which can be found in bacteria, presents hypervariable regions that serve as markers to identify the bacteria present.

If a microbiome is found to be somewhat unhealthy, it is theoretically possible to change its composition, increasing the chances of successful assisted reproduction. The administration of antibiotics and vaginal probiotics are two treatment approaches.

According to Dr. Simón, treatment is specific to the bacterium (metronidazole, and, if that fails, rifampicin for Gardnerella, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid for Streptococci). Once the pathogenic bacterium has been treated, the probiotics can be administered. “If all is well, we can then go ahead with the procedure,” he explained.

Dr. Simón pointed out that, with respect to treatment, knowledge is still limited and primarily based on case reports. “You look for issues in the microbiome when the patient experiences reproductive failure and there are no other causes,” he emphasized. “Microbiology plays a role in reproduction, affecting the human uterus. It’s good to know about it to improve reproductive outcomes. When there are repeated [embryo] implantation failures, we suggest an endometrial biopsy to identify the implantation window and determine whether the uterine microbiome is healthy or not. And if there are any abnormalities in the microbiome, they can be treated.”

There are still many open questions, such as how long the “good microbiome” lasts after antibiotic therapy. “We suggest checking the microbiome after [antibiotic] treatment and before implanting the embryo,” said Dr. Simón.

Although there is no consensus on how the endometrial microbiota relate to reproductive outcomes, the analysis and change in microbiome are already being offered in clinical practice as a way to increase the chances of conception. Márcia Riboldi, PhD, a genetics specialist serving as Country Manager for Igenomix Brasil and Argentina, the company that offers the analyses, provides an idea of the market for such analyses in Brazil. “We perform approximately 500 analyses per month,” she said, adding that most patients have a history of [embryo] implantation failure or miscarriage.

Matheus Roque, MD, PhD, an IVF specialist, shared two IVF case reports from the Mater Prime Human Reproduction Clinic in the southern region of the city of São Paulo. He emphasized that the decision to perform a microbiome analysis was made only after repeated implantation failure.

“With the outcomes the doctors started to see, the paradigm started to shift,” said Dr. Riboldi. “Why wait for the patient to have [an embryo] transfer failure? Let’s study the endometrium, check the ideal moment for the transfer, see whether it’s receptive or not, if there’s any disease and if there are Lactobacilli,” she proposed. “We need medical training and awareness, and we need to use them appropriately. We have the tests. Doctors need to learn about them and know when and how to use them.” The microbiome analysis costs approximately BRL 2,000, plus expenses for the medical procedure.

Is it too early?

Caio Parente Barbosa, MD, PhD, is an obstetrician/gynecologist specializing in human reproduction, as well as the director general and founder of the Fertile Idea Institute for Reproductive Health. He shared a few of his experiences in an interview with this news organization. “I would say it is still too early to confirm that [the microbiome analysis] produces effective outcomes.”

Dr. Barbosa, who is also provost of graduate studies, research, and innovation of the ABC School of Medicine, Santo André, Brazil, emphasized there is still little global experience with these analyses. “There are doubts worldwide regarding whether these analyses produce effective outcomes. Scientific studies are entirely controversial.”

He stated that some professionals recommend the microbiome analysis for “patients who don’t know what else to do,” but also recognized that there is already a demand for patients who don’t fit this category, who research the analyses on social networks and YouTube. “But it is the smallest of demands. Patients are not as worried about this yet.”

Dr. Barbosa recognized that the idea of an increasingly tailored treatment plan is inevitable. He believes that the study and treatment of the microbiome will become more critical in the future, but he thinks it still “does not offer any value.”

Dr. Barbosa emphasized that the financial side of things must also be considered. “If we add all these tests when investigating a patient’s issues, the treatment becomes ridiculously expensive.” He pointed out that health care professionals need to be careful to perform minimal testing. “We have already added some tests, such as the karyotype test, to the minimal testing for all patients.”

Dr. Simón responded to this criticism, stating: “The cost of repeating cycles is always greater than that of being thorough and knowing what’s going on. Nothing is certain, but if my daughter or wife needed it, I would like to have as much information as possible to make this decision.”

Dr. Barbosa and Dr. Simón reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Riboldi is Country Manager for Igenomix Brasil and Argentina, the company that offers the analyses.

This article was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition and appeared on Medscape.com.

Early FMT shows promise for preventing recurrent C. difficile

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is safe and highly effective as first-line therapy for patients with first or second Clostridioides difficile infection, according to the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of its kind.

Study enrollment was halted after an interim analysis revealed significantly better outcomes among patients who received vancomycin plus FMT versus vancomycin alone, reported lead author Simon Mark Dahl Baunwall, MD, of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital and colleagues in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

The investigators noted that the participants represented a real-world patient population, so the data support FMT “as a necessary, effective first-line option” in routine management of C. difficile infection.

“Previous studies have demonstrated clinical cure rates [with FMT] of up to 92%,” Dr. Baunwall and colleagues wrote. “Early use of FMT for first or second C. difficile infection has therapeutic potential, but no formal randomized trials to support use of the approach as a first-line therapy have been done.”

The present trial, conducted at a university hospital in Denmark, involved 42 adult patients with first or second C. difficile infection. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either vancomycin alone or vancomycin plus FMT. All patients received 125 mg oral vancomycin four times daily for a minimum of 10 days after diagnosis. On day 1 after completion of vancomycin therapy and again between day 3 and 7, patients received either oral FMT or matching placebo, depending on their group. After completing the protocol, patients were followed for 8 weeks or C. difficile recurrence to evaluate resolution of C. difficile–associated diarrhea.

“In this trial, patients were treated with two sequential FMT procedures on separate days,” the investigators noted. “This practice might have overtreated some patients and differs from previous trials. It remains unknown whether optimal effect is achieved by one or two treatments.”

The trial design called for 84 patients, but enrollment was halted after an interim analysis of the above cohort of 42 patients because of significantly lower rate resolution in the placebo group. At the 2-month mark, 90% (95% confidence interval, 70%-99%) of patients in the FMT group had resolution, compared with only 33% (95% CI, 15%-57%) of patients in the placebo group (P = .0003), constituting a 57% (95% CI, 33%-81%) absolute risk reduction.

Most patients experienced adverse events, including 20 in the FMT group and all 21 in the placebo group, although most were transient and nonserious. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, which occurred more frequently in the FMT group (23 vs. 14 events), followed by abdominal pain(14 vs. 11 events) and nausea (12 vs. 5 events).

One limitation of the study was its single-center design with regional uptake; the authors noted that, despite having high statistical power for the clinical effect, the study’s premature termination and low patient number prevent inferences regarding mortality, time to effect, and cost.

“The results of this trial highlight how the use of fecal microbiota transplantation as a first-line treatment can effectively prevent C. difficile recurrence and suggests that microbiota restoration might be necessary to obtain sustained resolution,” the investigators wrote. “At present, only 10% of patients with multiple, recurrent C. difficile infection and indication for FMT receive it. International initiatives address the unmet need, but logistic and regulatory obstacles remain unsolved.”

Encouraging findings, lingering concerns

Nicholas Turner, MD, assistant professor in the division of infectious diseases at Duke University, Durham, N.C., praised the study for “pushing the boundaries for FMT,” and noted that the methodology appeared sound. Results in the placebo group, however, cast doubt on the generalizability of the findings, he said.

“If you look at the group that received vancomycin plus placebo, their failure rate was really astoundingly high,” Dr. Turner said in an interview, referring to the 67% failure rate in the control group; he noted previous studies had reported failure rates closer to 10%. “I think that just calls into question just a little bit what happened with that control group.”

Dr. Turner said his confidence would go “way, way up” if the findings were reproduced in a larger study. Ideally, these future trials would use fidaxomicin, he added, which is becoming the preferred option over vancomycin for treating C. difficile.

John Y. Kao, MD, professor of medicine and codirector of the FMT program at University of Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, offered a different perspective, suggesting that the control group findings shouldn’t overshadow the efficacy of FMT.

“I agree that historical data would tell us that the placebo population should see a much higher response,” Dr. Kao said in an interview. “In my mind though, the success rate of FMT over placebo is what I would expect. The message of the study should be upheld: that FMT is an effective therapy whether it’s given early or, as the way we give it now, as a sort of rescue therapy.”

Despite this confidence in FMT as an efficacious first-line option, Dr. Kao said it is unlikely to be routinely used in this way anytime soon, even if a larger trial echoes the present results.

“We don’t know the long-term risks of FMT therapy, although we’ve been doing this now probably close to 20 years,” Dr. Kao said.

Specifically, Dr. Kao was most concerned about the long-term risk of colon cancer, as mouse models suggest that microbiome characteristics may affect risk level, and risk may vary based on host-microbiome relationships. In other words, an organism may pose no risk in the gut of the donor, but the same may not be true for the recipient.

While increased rates of colon cancer or other serious illnesses have not been detected in humans who have undergone FMT over the past 2 decades, Dr. Kao said that these findings cannot be extrapolated over a patient’s entire lifetime, especially for younger individuals.

“In a patient that’s 80, you would say, yeah, let’s go ahead and treat you [with FMT] as first-line therapy, whereas someone who’s 20, and has maybe another 50 or 60 years longevity, you may not want to give FMT as first-line therapy,” Dr. Kao said.

This study was supported by Innovation Fund Denmark. The investigators disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Turner previously performed statistical analyses for a Merck study comparing vancomycin, fidaxomicin, and metronidazole for C. difficile infection. Dr. Kao disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is safe and highly effective as first-line therapy for patients with first or second Clostridioides difficile infection, according to the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of its kind.

Study enrollment was halted after an interim analysis revealed significantly better outcomes among patients who received vancomycin plus FMT versus vancomycin alone, reported lead author Simon Mark Dahl Baunwall, MD, of Aarhus (Denmark) University Hospital and colleagues in The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

The investigators noted that the participants represented a real-world patient population, so the data support FMT “as a necessary, effective first-line option” in routine management of C. difficile infection.

“Previous studies have demonstrated clinical cure rates [with FMT] of up to 92%,” Dr. Baunwall and colleagues wrote. “Early use of FMT for first or second C. difficile infection has therapeutic potential, but no formal randomized trials to support use of the approach as a first-line therapy have been done.”

The present trial, conducted at a university hospital in Denmark, involved 42 adult patients with first or second C. difficile infection. Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive either vancomycin alone or vancomycin plus FMT. All patients received 125 mg oral vancomycin four times daily for a minimum of 10 days after diagnosis. On day 1 after completion of vancomycin therapy and again between day 3 and 7, patients received either oral FMT or matching placebo, depending on their group. After completing the protocol, patients were followed for 8 weeks or C. difficile recurrence to evaluate resolution of C. difficile–associated diarrhea.

“In this trial, patients were treated with two sequential FMT procedures on separate days,” the investigators noted. “This practice might have overtreated some patients and differs from previous trials. It remains unknown whether optimal effect is achieved by one or two treatments.”

The trial design called for 84 patients, but enrollment was halted after an interim analysis of the above cohort of 42 patients because of significantly lower rate resolution in the placebo group. At the 2-month mark, 90% (95% confidence interval, 70%-99%) of patients in the FMT group had resolution, compared with only 33% (95% CI, 15%-57%) of patients in the placebo group (P = .0003), constituting a 57% (95% CI, 33%-81%) absolute risk reduction.

Most patients experienced adverse events, including 20 in the FMT group and all 21 in the placebo group, although most were transient and nonserious. The most common adverse events were diarrhea, which occurred more frequently in the FMT group (23 vs. 14 events), followed by abdominal pain(14 vs. 11 events) and nausea (12 vs. 5 events).

One limitation of the study was its single-center design with regional uptake; the authors noted that, despite having high statistical power for the clinical effect, the study’s premature termination and low patient number prevent inferences regarding mortality, time to effect, and cost.

“The results of this trial highlight how the use of fecal microbiota transplantation as a first-line treatment can effectively prevent C. difficile recurrence and suggests that microbiota restoration might be necessary to obtain sustained resolution,” the investigators wrote. “At present, only 10% of patients with multiple, recurrent C. difficile infection and indication for FMT receive it. International initiatives address the unmet need, but logistic and regulatory obstacles remain unsolved.”

Encouraging findings, lingering concerns

Nicholas Turner, MD, assistant professor in the division of infectious diseases at Duke University, Durham, N.C., praised the study for “pushing the boundaries for FMT,” and noted that the methodology appeared sound. Results in the placebo group, however, cast doubt on the generalizability of the findings, he said.

“If you look at the group that received vancomycin plus placebo, their failure rate was really astoundingly high,” Dr. Turner said in an interview, referring to the 67% failure rate in the control group; he noted previous studies had reported failure rates closer to 10%. “I think that just calls into question just a little bit what happened with that control group.”

Dr. Turner said his confidence would go “way, way up” if the findings were reproduced in a larger study. Ideally, these future trials would use fidaxomicin, he added, which is becoming the preferred option over vancomycin for treating C. difficile.

John Y. Kao, MD, professor of medicine and codirector of the FMT program at University of Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor, offered a different perspective, suggesting that the control group findings shouldn’t overshadow the efficacy of FMT.

“I agree that historical data would tell us that the placebo population should see a much higher response,” Dr. Kao said in an interview. “In my mind though, the success rate of FMT over placebo is what I would expect. The message of the study should be upheld: that FMT is an effective therapy whether it’s given early or, as the way we give it now, as a sort of rescue therapy.”

Despite this confidence in FMT as an efficacious first-line option, Dr. Kao said it is unlikely to be routinely used in this way anytime soon, even if a larger trial echoes the present results.

“We don’t know the long-term risks of FMT therapy, although we’ve been doing this now probably close to 20 years,” Dr. Kao said.

Specifically, Dr. Kao was most concerned about the long-term risk of colon cancer, as mouse models suggest that microbiome characteristics may affect risk level, and risk may vary based on host-microbiome relationships. In other words, an organism may pose no risk in the gut of the donor, but the same may not be true for the recipient.

While increased rates of colon cancer or other serious illnesses have not been detected in humans who have undergone FMT over the past 2 decades, Dr. Kao said that these findings cannot be extrapolated over a patient’s entire lifetime, especially for younger individuals.

“In a patient that’s 80, you would say, yeah, let’s go ahead and treat you [with FMT] as first-line therapy, whereas someone who’s 20, and has maybe another 50 or 60 years longevity, you may not want to give FMT as first-line therapy,” Dr. Kao said.

This study was supported by Innovation Fund Denmark. The investigators disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Turner previously performed statistical analyses for a Merck study comparing vancomycin, fidaxomicin, and metronidazole for C. difficile infection. Dr. Kao disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.