User login

What are your weaknesses?

In a video posted to TikTok by the comedian Will Flanary, MD, better known to his followers as Dr. Glaucomflecken, he imitates a neurosurgical residency interview. With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Dr. Glaucomflecken poses as the attending, asking: “What are your weaknesses?”

The residency applicant answers without hesitation: “My physiological need for sleep.” “What are your strengths?” The resident replies with the hard, steely stare of the determined and uninitiated: “My desire to eliminate my physiological need for sleep.”

If you follow Dr. Glaucomflecken on Twitter, you might know the skit I’m referencing. For many physicians and physicians-in-training, what makes the satire successful is its reflection of reality.

Many things have changed in medicine since his time, but the tired trope of the sleepless surgeon hangs on. Undaunted, I spent my second and third year of medical school accumulating accolades, conducting research, and connecting with mentors with the singular goal of joining the surgical ranks.

Midway through my third year, I completed a month-long surgical subinternship designed to give students a taste of what life would look like as an intern. I loved the operating room; it felt like the difference between being on dry land and being underwater. There were fewer distractions – your patient in the spotlight while everything else receded to the shadows.

However, as the month wore on, something stronger took hold. I couldn’t keep my eyes open in the darkened operating rooms and had to decline stools, fearing that I would fall asleep if I sat down.

On early morning prerounds, it’s 4:50 a.m. when I glance at the clock and pull back the curtain, already apologizing. My patient rolls over, flashing a wry smile. “Do you ever go home?” I’ve seen residents respond to this exact question in various ways. I live here. Yes. No. Soon. Not enough. My partner doesn’t think so.

There are days and, yes, years when we are led to believe this is what we live for: to be constantly available to our patients. It feels like a hollow victory when the patient, 2 days out from a total colectomy, begins to worry about your personal life. I ask her how she slept (not enough), any fevers (no), vomiting (no), urinating (I pause – she has a catheter).

My favorite part of these early morning rounds is the pause in my scripted litany of questions to listen to heart and lungs. It never fails to feel sacred: Patients become so quiet and still that I can’t help but think they have faith in me. Without prompting, she slides the back of her hospital gown forward like a curtain, already taking deep breaths so I can hear her lungs.

I look outside. The streetlights are still on, and from the seventh-floor window, I can watch staff making their way through the sliding double-doors, just beyond the yellowed pools of streetlight. I smile. I love medicine. I’m so tired.

For many in medicine, we are treated, and thus behave, as though our ability to manipulate physiology should also apply within the borders of our bodies: commanding less sleep, food, or bathroom breaks.

It places health care workers solidly in the realm of superhuman, living beyond one’s corporeal needs. The pandemic only heightened this misappropriation – adding hero and setting out a pedestal for health care workers to make their ungainly ascent. This kind of unsolicited admiration implicitly implies inhumanness, an otherness.

What would it look like if we started treating ourselves less like physicians and more like patients? I wish I was offering a solution, but really this is just a story.

To students rising through the ranks of medical training, identify what it is you need early and often. I can count on one hand how many physicians I’ve seen take a lunch break – even 10 minutes. Embrace hard work and self-preservation equally. My hope is that if enough of us take this path, it just might become a matter of course.

Dr. Meffert is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Washington. Dr. Meffert disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a video posted to TikTok by the comedian Will Flanary, MD, better known to his followers as Dr. Glaucomflecken, he imitates a neurosurgical residency interview. With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Dr. Glaucomflecken poses as the attending, asking: “What are your weaknesses?”

The residency applicant answers without hesitation: “My physiological need for sleep.” “What are your strengths?” The resident replies with the hard, steely stare of the determined and uninitiated: “My desire to eliminate my physiological need for sleep.”

If you follow Dr. Glaucomflecken on Twitter, you might know the skit I’m referencing. For many physicians and physicians-in-training, what makes the satire successful is its reflection of reality.

Many things have changed in medicine since his time, but the tired trope of the sleepless surgeon hangs on. Undaunted, I spent my second and third year of medical school accumulating accolades, conducting research, and connecting with mentors with the singular goal of joining the surgical ranks.

Midway through my third year, I completed a month-long surgical subinternship designed to give students a taste of what life would look like as an intern. I loved the operating room; it felt like the difference between being on dry land and being underwater. There were fewer distractions – your patient in the spotlight while everything else receded to the shadows.

However, as the month wore on, something stronger took hold. I couldn’t keep my eyes open in the darkened operating rooms and had to decline stools, fearing that I would fall asleep if I sat down.

On early morning prerounds, it’s 4:50 a.m. when I glance at the clock and pull back the curtain, already apologizing. My patient rolls over, flashing a wry smile. “Do you ever go home?” I’ve seen residents respond to this exact question in various ways. I live here. Yes. No. Soon. Not enough. My partner doesn’t think so.

There are days and, yes, years when we are led to believe this is what we live for: to be constantly available to our patients. It feels like a hollow victory when the patient, 2 days out from a total colectomy, begins to worry about your personal life. I ask her how she slept (not enough), any fevers (no), vomiting (no), urinating (I pause – she has a catheter).

My favorite part of these early morning rounds is the pause in my scripted litany of questions to listen to heart and lungs. It never fails to feel sacred: Patients become so quiet and still that I can’t help but think they have faith in me. Without prompting, she slides the back of her hospital gown forward like a curtain, already taking deep breaths so I can hear her lungs.

I look outside. The streetlights are still on, and from the seventh-floor window, I can watch staff making their way through the sliding double-doors, just beyond the yellowed pools of streetlight. I smile. I love medicine. I’m so tired.

For many in medicine, we are treated, and thus behave, as though our ability to manipulate physiology should also apply within the borders of our bodies: commanding less sleep, food, or bathroom breaks.

It places health care workers solidly in the realm of superhuman, living beyond one’s corporeal needs. The pandemic only heightened this misappropriation – adding hero and setting out a pedestal for health care workers to make their ungainly ascent. This kind of unsolicited admiration implicitly implies inhumanness, an otherness.

What would it look like if we started treating ourselves less like physicians and more like patients? I wish I was offering a solution, but really this is just a story.

To students rising through the ranks of medical training, identify what it is you need early and often. I can count on one hand how many physicians I’ve seen take a lunch break – even 10 minutes. Embrace hard work and self-preservation equally. My hope is that if enough of us take this path, it just might become a matter of course.

Dr. Meffert is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Washington. Dr. Meffert disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In a video posted to TikTok by the comedian Will Flanary, MD, better known to his followers as Dr. Glaucomflecken, he imitates a neurosurgical residency interview. With glasses perched on the bridge of his nose, Dr. Glaucomflecken poses as the attending, asking: “What are your weaknesses?”

The residency applicant answers without hesitation: “My physiological need for sleep.” “What are your strengths?” The resident replies with the hard, steely stare of the determined and uninitiated: “My desire to eliminate my physiological need for sleep.”

If you follow Dr. Glaucomflecken on Twitter, you might know the skit I’m referencing. For many physicians and physicians-in-training, what makes the satire successful is its reflection of reality.

Many things have changed in medicine since his time, but the tired trope of the sleepless surgeon hangs on. Undaunted, I spent my second and third year of medical school accumulating accolades, conducting research, and connecting with mentors with the singular goal of joining the surgical ranks.

Midway through my third year, I completed a month-long surgical subinternship designed to give students a taste of what life would look like as an intern. I loved the operating room; it felt like the difference between being on dry land and being underwater. There were fewer distractions – your patient in the spotlight while everything else receded to the shadows.

However, as the month wore on, something stronger took hold. I couldn’t keep my eyes open in the darkened operating rooms and had to decline stools, fearing that I would fall asleep if I sat down.

On early morning prerounds, it’s 4:50 a.m. when I glance at the clock and pull back the curtain, already apologizing. My patient rolls over, flashing a wry smile. “Do you ever go home?” I’ve seen residents respond to this exact question in various ways. I live here. Yes. No. Soon. Not enough. My partner doesn’t think so.

There are days and, yes, years when we are led to believe this is what we live for: to be constantly available to our patients. It feels like a hollow victory when the patient, 2 days out from a total colectomy, begins to worry about your personal life. I ask her how she slept (not enough), any fevers (no), vomiting (no), urinating (I pause – she has a catheter).

My favorite part of these early morning rounds is the pause in my scripted litany of questions to listen to heart and lungs. It never fails to feel sacred: Patients become so quiet and still that I can’t help but think they have faith in me. Without prompting, she slides the back of her hospital gown forward like a curtain, already taking deep breaths so I can hear her lungs.

I look outside. The streetlights are still on, and from the seventh-floor window, I can watch staff making their way through the sliding double-doors, just beyond the yellowed pools of streetlight. I smile. I love medicine. I’m so tired.

For many in medicine, we are treated, and thus behave, as though our ability to manipulate physiology should also apply within the borders of our bodies: commanding less sleep, food, or bathroom breaks.

It places health care workers solidly in the realm of superhuman, living beyond one’s corporeal needs. The pandemic only heightened this misappropriation – adding hero and setting out a pedestal for health care workers to make their ungainly ascent. This kind of unsolicited admiration implicitly implies inhumanness, an otherness.

What would it look like if we started treating ourselves less like physicians and more like patients? I wish I was offering a solution, but really this is just a story.

To students rising through the ranks of medical training, identify what it is you need early and often. I can count on one hand how many physicians I’ve seen take a lunch break – even 10 minutes. Embrace hard work and self-preservation equally. My hope is that if enough of us take this path, it just might become a matter of course.

Dr. Meffert is a resident in the department of emergency medicine, MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington Hospital Center, Washington. Dr. Meffert disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Charcoal could be the cure for the common high-fat diet

Charcoal won’t let high-fat diet weigh you down

Do you want to be the funniest person alive? Of course you do. It’s really simple too, just one joke can make you the greatest comedian of all time. All you have to do is go camping and cook food over a roaring campfire. When someone drops food into the fire (which they always will), get ready. Once they fish out the offending food, which is almost certainly coated in hot coals, tell them: “Ah, eat it anyway. A little texture never hurt!” Trust us, most hilarious and original gag of all time.

But before your hapless friend brushes off his hot dog and forces a laugh, consider this: Japanese researchers have found that a charcoal supplement can prevent weight gain in mice consuming a high-fat diet. Charcoal is actually quite the helpful substance, and not just for grilling. It’s been used as medicine for hundreds of years and even today is used as a treatment for drug overdose and excess gas and flatulence.

The study involved two groups of mice: One was fed a normal diet, the other a high-fat diet. After 12 weeks, the high-fat diet mice had gained weight. At that point, edible activated charcoal was added to their diet. From that point, weight gain was similar between the two groups, and the amount of bile acid, cholesterol, triglyceride, and fatty acid excreted by the high-fat mice increased by two to four times.

The researchers supported the notion that consuming an activated charcoal supplement before or while eating fatty food could prevent weight gain from said fatty food. Which works out well for the classic American barbecue, which is traditionally both high in fat and charcoal. All you have to do is buy some extra charcoal briquettes to pass around and munch on with your friends. Now that’s a party we can get behind.

There’s awake, and then there’s neurologically awake

Time to toss another urban legend onto the trash heap of history. Say goodbye to the benefits of uninterrupted sleep. It’s a fraud, a fake, a myth, a hit or myth, a swing and a myth, an old wives’ tale. You can stuff it and put it on a shelf next to Bigfoot, the Slender Man, and Twinkies.

We all thought we needed 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep every night, but guess who we forgot to tell? Our brains. They’ve been doing exactly the opposite all along, laughing at us the whole time. Smug SOBs.

To straighten out this mess, let’s bring in a scientist, Celia Kjaerby of the Center for Translational Neuromedicine at the University of Copenhagen: “You may think that sleep is a constant state that you are in, and then you wake up. But there is a lot more to sleep than meets the eye. We have learned that noradrenaline causes you to wake up more than 100 times a night. And that is during perfectly normal sleep.”

Those 100 or so sleep interruptions are so brief that we don’t even notice, but they are very important, according to a study conducted at the university. Those tiny little wake-up calls are “the essence for the part of sleep that makes us wake up rested and which enables us to remember what we learned the day before. ... The very short awakenings are created by waves of norepinephrine [and they] reset the brain so that it is ready to store memory when you dive back into sleep,” lead author Maiken Nedergaard, MD, explained.

The investigators compared the level of noradrenaline in sleeping mice with their electrical activity and found that the hormone constantly increased and decreased in a wavelike pattern. A high level meant that the animal was neurologically awake. Deeper valleys between the high points meant better sleep, and the mice with the “highest number of deep noradrenaline valleys were also the ones with the best memory,” the team said in their written statement.

Not just the best memory, they said, but “super memory.” That, of course, was enough to get the attention of Marvel Comics, so the next Disney superhero blockbuster will feature Nocturna, the queen of the night. Her power? Never forgets. Her archnemesis? The Insomniac. Her catchphrase? “Let me sleep on it.”

Words can hurt, literally

Growing up, we’re sure you heard the “sticks and stones” rhyme. Maybe you’ve even recited it once or twice to defend yourself. Well, forget it, because words can hurt and your brain knows it.

In a new study published in Frontiers in Communication, Marijn Struiksma, PhD, of Utrecht University, and colleagues incorporated the use of electroencephalography (EEG) and skin conductance on 79 women to see how words (specifically insults) actually affect the human body.

Each subject was asked to read three different types of statements: an insult, a compliment, and something factual but neutral. Half of the statements contained the subject’s name and half used somebody else’s. The participants were told that these statements were collected from three men.

Nobody interacted with each other, and the setting was completely clinical, yet the results were unmistakable. The EEG showed an effect in P2 amplitude with repetitive insults, no matter who it was about. Even though the insults weren’t real and the participants were aware of it, the brain still recognized them as hurtful, coming across as “mini slaps in the face,” Dr. Struiksma noted in a written statement.

The researchers noted that more needs to be done to better understand the long-term effects that insults can have and create a deeper understanding between words and emotion, but studying the effects of insults in a real-life setting is ethically tricky. This study is a start.

So, yeah, sticks and stones can break your bones, but words will actually hurt you.

This article was updated 7/21/22.

Charcoal won’t let high-fat diet weigh you down

Do you want to be the funniest person alive? Of course you do. It’s really simple too, just one joke can make you the greatest comedian of all time. All you have to do is go camping and cook food over a roaring campfire. When someone drops food into the fire (which they always will), get ready. Once they fish out the offending food, which is almost certainly coated in hot coals, tell them: “Ah, eat it anyway. A little texture never hurt!” Trust us, most hilarious and original gag of all time.

But before your hapless friend brushes off his hot dog and forces a laugh, consider this: Japanese researchers have found that a charcoal supplement can prevent weight gain in mice consuming a high-fat diet. Charcoal is actually quite the helpful substance, and not just for grilling. It’s been used as medicine for hundreds of years and even today is used as a treatment for drug overdose and excess gas and flatulence.

The study involved two groups of mice: One was fed a normal diet, the other a high-fat diet. After 12 weeks, the high-fat diet mice had gained weight. At that point, edible activated charcoal was added to their diet. From that point, weight gain was similar between the two groups, and the amount of bile acid, cholesterol, triglyceride, and fatty acid excreted by the high-fat mice increased by two to four times.

The researchers supported the notion that consuming an activated charcoal supplement before or while eating fatty food could prevent weight gain from said fatty food. Which works out well for the classic American barbecue, which is traditionally both high in fat and charcoal. All you have to do is buy some extra charcoal briquettes to pass around and munch on with your friends. Now that’s a party we can get behind.

There’s awake, and then there’s neurologically awake

Time to toss another urban legend onto the trash heap of history. Say goodbye to the benefits of uninterrupted sleep. It’s a fraud, a fake, a myth, a hit or myth, a swing and a myth, an old wives’ tale. You can stuff it and put it on a shelf next to Bigfoot, the Slender Man, and Twinkies.

We all thought we needed 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep every night, but guess who we forgot to tell? Our brains. They’ve been doing exactly the opposite all along, laughing at us the whole time. Smug SOBs.

To straighten out this mess, let’s bring in a scientist, Celia Kjaerby of the Center for Translational Neuromedicine at the University of Copenhagen: “You may think that sleep is a constant state that you are in, and then you wake up. But there is a lot more to sleep than meets the eye. We have learned that noradrenaline causes you to wake up more than 100 times a night. And that is during perfectly normal sleep.”

Those 100 or so sleep interruptions are so brief that we don’t even notice, but they are very important, according to a study conducted at the university. Those tiny little wake-up calls are “the essence for the part of sleep that makes us wake up rested and which enables us to remember what we learned the day before. ... The very short awakenings are created by waves of norepinephrine [and they] reset the brain so that it is ready to store memory when you dive back into sleep,” lead author Maiken Nedergaard, MD, explained.

The investigators compared the level of noradrenaline in sleeping mice with their electrical activity and found that the hormone constantly increased and decreased in a wavelike pattern. A high level meant that the animal was neurologically awake. Deeper valleys between the high points meant better sleep, and the mice with the “highest number of deep noradrenaline valleys were also the ones with the best memory,” the team said in their written statement.

Not just the best memory, they said, but “super memory.” That, of course, was enough to get the attention of Marvel Comics, so the next Disney superhero blockbuster will feature Nocturna, the queen of the night. Her power? Never forgets. Her archnemesis? The Insomniac. Her catchphrase? “Let me sleep on it.”

Words can hurt, literally

Growing up, we’re sure you heard the “sticks and stones” rhyme. Maybe you’ve even recited it once or twice to defend yourself. Well, forget it, because words can hurt and your brain knows it.

In a new study published in Frontiers in Communication, Marijn Struiksma, PhD, of Utrecht University, and colleagues incorporated the use of electroencephalography (EEG) and skin conductance on 79 women to see how words (specifically insults) actually affect the human body.

Each subject was asked to read three different types of statements: an insult, a compliment, and something factual but neutral. Half of the statements contained the subject’s name and half used somebody else’s. The participants were told that these statements were collected from three men.

Nobody interacted with each other, and the setting was completely clinical, yet the results were unmistakable. The EEG showed an effect in P2 amplitude with repetitive insults, no matter who it was about. Even though the insults weren’t real and the participants were aware of it, the brain still recognized them as hurtful, coming across as “mini slaps in the face,” Dr. Struiksma noted in a written statement.

The researchers noted that more needs to be done to better understand the long-term effects that insults can have and create a deeper understanding between words and emotion, but studying the effects of insults in a real-life setting is ethically tricky. This study is a start.

So, yeah, sticks and stones can break your bones, but words will actually hurt you.

This article was updated 7/21/22.

Charcoal won’t let high-fat diet weigh you down

Do you want to be the funniest person alive? Of course you do. It’s really simple too, just one joke can make you the greatest comedian of all time. All you have to do is go camping and cook food over a roaring campfire. When someone drops food into the fire (which they always will), get ready. Once they fish out the offending food, which is almost certainly coated in hot coals, tell them: “Ah, eat it anyway. A little texture never hurt!” Trust us, most hilarious and original gag of all time.

But before your hapless friend brushes off his hot dog and forces a laugh, consider this: Japanese researchers have found that a charcoal supplement can prevent weight gain in mice consuming a high-fat diet. Charcoal is actually quite the helpful substance, and not just for grilling. It’s been used as medicine for hundreds of years and even today is used as a treatment for drug overdose and excess gas and flatulence.

The study involved two groups of mice: One was fed a normal diet, the other a high-fat diet. After 12 weeks, the high-fat diet mice had gained weight. At that point, edible activated charcoal was added to their diet. From that point, weight gain was similar between the two groups, and the amount of bile acid, cholesterol, triglyceride, and fatty acid excreted by the high-fat mice increased by two to four times.

The researchers supported the notion that consuming an activated charcoal supplement before or while eating fatty food could prevent weight gain from said fatty food. Which works out well for the classic American barbecue, which is traditionally both high in fat and charcoal. All you have to do is buy some extra charcoal briquettes to pass around and munch on with your friends. Now that’s a party we can get behind.

There’s awake, and then there’s neurologically awake

Time to toss another urban legend onto the trash heap of history. Say goodbye to the benefits of uninterrupted sleep. It’s a fraud, a fake, a myth, a hit or myth, a swing and a myth, an old wives’ tale. You can stuff it and put it on a shelf next to Bigfoot, the Slender Man, and Twinkies.

We all thought we needed 8 hours of uninterrupted sleep every night, but guess who we forgot to tell? Our brains. They’ve been doing exactly the opposite all along, laughing at us the whole time. Smug SOBs.

To straighten out this mess, let’s bring in a scientist, Celia Kjaerby of the Center for Translational Neuromedicine at the University of Copenhagen: “You may think that sleep is a constant state that you are in, and then you wake up. But there is a lot more to sleep than meets the eye. We have learned that noradrenaline causes you to wake up more than 100 times a night. And that is during perfectly normal sleep.”

Those 100 or so sleep interruptions are so brief that we don’t even notice, but they are very important, according to a study conducted at the university. Those tiny little wake-up calls are “the essence for the part of sleep that makes us wake up rested and which enables us to remember what we learned the day before. ... The very short awakenings are created by waves of norepinephrine [and they] reset the brain so that it is ready to store memory when you dive back into sleep,” lead author Maiken Nedergaard, MD, explained.

The investigators compared the level of noradrenaline in sleeping mice with their electrical activity and found that the hormone constantly increased and decreased in a wavelike pattern. A high level meant that the animal was neurologically awake. Deeper valleys between the high points meant better sleep, and the mice with the “highest number of deep noradrenaline valleys were also the ones with the best memory,” the team said in their written statement.

Not just the best memory, they said, but “super memory.” That, of course, was enough to get the attention of Marvel Comics, so the next Disney superhero blockbuster will feature Nocturna, the queen of the night. Her power? Never forgets. Her archnemesis? The Insomniac. Her catchphrase? “Let me sleep on it.”

Words can hurt, literally

Growing up, we’re sure you heard the “sticks and stones” rhyme. Maybe you’ve even recited it once or twice to defend yourself. Well, forget it, because words can hurt and your brain knows it.

In a new study published in Frontiers in Communication, Marijn Struiksma, PhD, of Utrecht University, and colleagues incorporated the use of electroencephalography (EEG) and skin conductance on 79 women to see how words (specifically insults) actually affect the human body.

Each subject was asked to read three different types of statements: an insult, a compliment, and something factual but neutral. Half of the statements contained the subject’s name and half used somebody else’s. The participants were told that these statements were collected from three men.

Nobody interacted with each other, and the setting was completely clinical, yet the results were unmistakable. The EEG showed an effect in P2 amplitude with repetitive insults, no matter who it was about. Even though the insults weren’t real and the participants were aware of it, the brain still recognized them as hurtful, coming across as “mini slaps in the face,” Dr. Struiksma noted in a written statement.

The researchers noted that more needs to be done to better understand the long-term effects that insults can have and create a deeper understanding between words and emotion, but studying the effects of insults in a real-life setting is ethically tricky. This study is a start.

So, yeah, sticks and stones can break your bones, but words will actually hurt you.

This article was updated 7/21/22.

Hormone therapy didn’t increase recurrence or mortality in women treated for breast cancer

Hormone therapy did not increase mortality in postmenopausal women treated for early-stage estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, but, in longitudinal data from Denmark, there was a recurrence risk with vaginal estrogen therapy among those treated with aromatase inhibitors.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) – including vaginal dryness, burning, and urinary incontinence – is common in women treated for breast cancer. Adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly aromatase inhibitors, can aggravate these symptoms. Both local and systemic estrogen therapy are recommended for alleviating GSM symptoms in healthy women, but concerns have been raised about their use in women with breast cancer. Previous studies examining this have suggested possible risks for breast cancer recurrence, but those studies have had several limitations including small samples and short follow-up, particularly for vaginal estrogen therapy.

In the new study, from a national Danish cohort of 8,461 postmenopausal women diagnosed between 1997 and 2004 and treated for early-stage invasive estrogen receptor–positive nonmetastatic breast cancer, neither systemic menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) nor local vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) were associated with an overall increased risk for either breast cancer recurrence or mortality. However, in the subset who had received an aromatase inhibitor – with or without tamoxifen – there was a statistically significant increased risk for breast cancer recurrence, but not mortality.

The results were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“The data are reassuring for the majority of women with no adjuvant therapy or tamoxifen. But for those using adjuvant aromatase inhibitors, there might be a small risk,” study lead author Søren Cold, MD, PhD, senior oncologist in the department of oncology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, Odense, said in an interview.

Moreover, Dr. Cold noted, while this study didn’t find an increased recurrence risk with MHT for women taking aromatase inhibitors, other studies have. One in particular was stopped because of harm. The reason for the difference here is likely that the previous sample was small – just 133 women.

“Our study is mainly focusing on the use of vaginal estrogen. We had so few patients using systemic menopausal hormone therapy, those data don’t mean much. ... The risk with systemic therapy has been established. The vaginal use hasn’t been thoroughly studied before,” he noted.

Breast cancer recurrence elevated with VET and aromatase inhibitors

The study pool was 9,710 women who underwent complete resection for estrogen-positive breast cancer and were all allocated to 5 years of adjuvant endocrine treatment or no adjuvant treatment, according to guidelines. Overall, 3,112 received no adjuvant endocrine treatment, 2,007 were treated with tamoxifen only, 403 with an aromatase inhibitor, and 2,939 with a sequence of tamoxifen and an aromatase inhibitor.

After exclusion of 1,249 who had received VET or MHT prior to breast cancer diagnosis, there were 6,391 not prescribed any estrogen hormonal treatment, 1,957 prescribed VET, and 133 prescribed MHT with or without VET.

During an estimated median 9.8 years’ follow-up, 1,333 women (16%) had a breast cancer recurrence. Of those, 111 had received VET, 16 MHT, and 1,206 neither. Compared with those receiving no hormonal treatment, the adjusted risk of recurrence was similar for the VET users (hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.32).

However, there was an increased risk for recurrence associated with initiating VET during aromatase inhibitor treatment (HR, 1.39, 95% CI, 1.04-1.85). For women receiving MHT, the adjusted relative risk of recurrence with aromatase inhibitors wasn’t significant (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.62-1.78).

Overall, compared with women who never used hormonal treatment, the absolute 10-year breast cancer recurrence risk was 19.2% for never-users of VET or MHT, 15.4% in VET users, and 17.1% in MHT users.

No differences found for mortality

Of the 8,461 women in the study, 40% (3,370) died during an estimated median follow-up of 15.2 years. Of those, 497 had received VET, 47 MHT, and 2,826 neither. Compared with the never-users of estrogen therapy, the adjusted HR for overall survival in VET users was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.71-0.87). The analysis stratified by adjuvant endocrine therapy didn’t show an increase in VET users by use of aromatase inhibitors (aHR, 0.94, 95% CI, 0.70-1.26). The same was found for women prescribed MHT, compared with never-users (aHR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.70-1.26).

Never-users of VET or MHT had an absolute 10-year overall survival of 73.8% versus 79.5% and 80.5% among the women who used VET or MHT, respectively.

Asked to comment, Nanette Santoro, MD, professor and E. Stewart Taylor Chair of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview: “It is important to look at this issue. These findings raise but don’t answer the question that vaginal estradiol may not be as safe as we hope it is for women with breast cancer using an aromatase inhibitor.”

However, she also pointed out that “the overall increase in risk is not enormous; mortality risk was not increased. Women need to consider that there may be some risk associated with this option in their decision making about taking it. Having a satisfying sex life is also important for many women! It is really compassionate use for quality of life, so there is always that unknown element of risk in the discussion. That unknown risk has to be balanced against the benefit that the estrogen provides.”

And, Dr. Santoro also noted that the use of prescription data poses limitations. “It cannot tell us what was going on in the minds of the patient and the prescriber. There may be differences in the prescriber’s impression of the patient’s risk of recurrence that influenced the decision to provide a prescription. ... Women using AIs [aromatase inhibitors] often get pretty severe vaginal dryness symptoms and may need more estrogen to be comfortable with intercourse, but we really cannot tell this from what is in this paper.”

Indeed, Dr. Cold said: “We admit it’s not a randomized study, but we’ve done what was possible to take [confounding] factors into account, including age, tumor size, nodal status, histology, and comorbidities.”

He suggested that a potential therapeutic approach to reducing the recurrence risk might be to switch VET-treated women to tamoxifen after 2-3 years of aromatase inhibitors.

This work was supported by Breast Friends, a part of the Danish Cancer Society. Dr. Cold received support from Breast Friends for the current study. Some of the other coauthors have pharmaceutical company disclosures. Dr. Santoro is a member of the scientific advisory boards for Astellas, Menogenix, Que Oncology, and Amazon Ember, and is a consultant for Ansh Labs.

Hormone therapy did not increase mortality in postmenopausal women treated for early-stage estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, but, in longitudinal data from Denmark, there was a recurrence risk with vaginal estrogen therapy among those treated with aromatase inhibitors.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) – including vaginal dryness, burning, and urinary incontinence – is common in women treated for breast cancer. Adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly aromatase inhibitors, can aggravate these symptoms. Both local and systemic estrogen therapy are recommended for alleviating GSM symptoms in healthy women, but concerns have been raised about their use in women with breast cancer. Previous studies examining this have suggested possible risks for breast cancer recurrence, but those studies have had several limitations including small samples and short follow-up, particularly for vaginal estrogen therapy.

In the new study, from a national Danish cohort of 8,461 postmenopausal women diagnosed between 1997 and 2004 and treated for early-stage invasive estrogen receptor–positive nonmetastatic breast cancer, neither systemic menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) nor local vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) were associated with an overall increased risk for either breast cancer recurrence or mortality. However, in the subset who had received an aromatase inhibitor – with or without tamoxifen – there was a statistically significant increased risk for breast cancer recurrence, but not mortality.

The results were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“The data are reassuring for the majority of women with no adjuvant therapy or tamoxifen. But for those using adjuvant aromatase inhibitors, there might be a small risk,” study lead author Søren Cold, MD, PhD, senior oncologist in the department of oncology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, Odense, said in an interview.

Moreover, Dr. Cold noted, while this study didn’t find an increased recurrence risk with MHT for women taking aromatase inhibitors, other studies have. One in particular was stopped because of harm. The reason for the difference here is likely that the previous sample was small – just 133 women.

“Our study is mainly focusing on the use of vaginal estrogen. We had so few patients using systemic menopausal hormone therapy, those data don’t mean much. ... The risk with systemic therapy has been established. The vaginal use hasn’t been thoroughly studied before,” he noted.

Breast cancer recurrence elevated with VET and aromatase inhibitors

The study pool was 9,710 women who underwent complete resection for estrogen-positive breast cancer and were all allocated to 5 years of adjuvant endocrine treatment or no adjuvant treatment, according to guidelines. Overall, 3,112 received no adjuvant endocrine treatment, 2,007 were treated with tamoxifen only, 403 with an aromatase inhibitor, and 2,939 with a sequence of tamoxifen and an aromatase inhibitor.

After exclusion of 1,249 who had received VET or MHT prior to breast cancer diagnosis, there were 6,391 not prescribed any estrogen hormonal treatment, 1,957 prescribed VET, and 133 prescribed MHT with or without VET.

During an estimated median 9.8 years’ follow-up, 1,333 women (16%) had a breast cancer recurrence. Of those, 111 had received VET, 16 MHT, and 1,206 neither. Compared with those receiving no hormonal treatment, the adjusted risk of recurrence was similar for the VET users (hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.32).

However, there was an increased risk for recurrence associated with initiating VET during aromatase inhibitor treatment (HR, 1.39, 95% CI, 1.04-1.85). For women receiving MHT, the adjusted relative risk of recurrence with aromatase inhibitors wasn’t significant (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.62-1.78).

Overall, compared with women who never used hormonal treatment, the absolute 10-year breast cancer recurrence risk was 19.2% for never-users of VET or MHT, 15.4% in VET users, and 17.1% in MHT users.

No differences found for mortality

Of the 8,461 women in the study, 40% (3,370) died during an estimated median follow-up of 15.2 years. Of those, 497 had received VET, 47 MHT, and 2,826 neither. Compared with the never-users of estrogen therapy, the adjusted HR for overall survival in VET users was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.71-0.87). The analysis stratified by adjuvant endocrine therapy didn’t show an increase in VET users by use of aromatase inhibitors (aHR, 0.94, 95% CI, 0.70-1.26). The same was found for women prescribed MHT, compared with never-users (aHR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.70-1.26).

Never-users of VET or MHT had an absolute 10-year overall survival of 73.8% versus 79.5% and 80.5% among the women who used VET or MHT, respectively.

Asked to comment, Nanette Santoro, MD, professor and E. Stewart Taylor Chair of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview: “It is important to look at this issue. These findings raise but don’t answer the question that vaginal estradiol may not be as safe as we hope it is for women with breast cancer using an aromatase inhibitor.”

However, she also pointed out that “the overall increase in risk is not enormous; mortality risk was not increased. Women need to consider that there may be some risk associated with this option in their decision making about taking it. Having a satisfying sex life is also important for many women! It is really compassionate use for quality of life, so there is always that unknown element of risk in the discussion. That unknown risk has to be balanced against the benefit that the estrogen provides.”

And, Dr. Santoro also noted that the use of prescription data poses limitations. “It cannot tell us what was going on in the minds of the patient and the prescriber. There may be differences in the prescriber’s impression of the patient’s risk of recurrence that influenced the decision to provide a prescription. ... Women using AIs [aromatase inhibitors] often get pretty severe vaginal dryness symptoms and may need more estrogen to be comfortable with intercourse, but we really cannot tell this from what is in this paper.”

Indeed, Dr. Cold said: “We admit it’s not a randomized study, but we’ve done what was possible to take [confounding] factors into account, including age, tumor size, nodal status, histology, and comorbidities.”

He suggested that a potential therapeutic approach to reducing the recurrence risk might be to switch VET-treated women to tamoxifen after 2-3 years of aromatase inhibitors.

This work was supported by Breast Friends, a part of the Danish Cancer Society. Dr. Cold received support from Breast Friends for the current study. Some of the other coauthors have pharmaceutical company disclosures. Dr. Santoro is a member of the scientific advisory boards for Astellas, Menogenix, Que Oncology, and Amazon Ember, and is a consultant for Ansh Labs.

Hormone therapy did not increase mortality in postmenopausal women treated for early-stage estrogen receptor–positive breast cancer, but, in longitudinal data from Denmark, there was a recurrence risk with vaginal estrogen therapy among those treated with aromatase inhibitors.

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) – including vaginal dryness, burning, and urinary incontinence – is common in women treated for breast cancer. Adjuvant endocrine therapy, particularly aromatase inhibitors, can aggravate these symptoms. Both local and systemic estrogen therapy are recommended for alleviating GSM symptoms in healthy women, but concerns have been raised about their use in women with breast cancer. Previous studies examining this have suggested possible risks for breast cancer recurrence, but those studies have had several limitations including small samples and short follow-up, particularly for vaginal estrogen therapy.

In the new study, from a national Danish cohort of 8,461 postmenopausal women diagnosed between 1997 and 2004 and treated for early-stage invasive estrogen receptor–positive nonmetastatic breast cancer, neither systemic menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) nor local vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) were associated with an overall increased risk for either breast cancer recurrence or mortality. However, in the subset who had received an aromatase inhibitor – with or without tamoxifen – there was a statistically significant increased risk for breast cancer recurrence, but not mortality.

The results were published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“The data are reassuring for the majority of women with no adjuvant therapy or tamoxifen. But for those using adjuvant aromatase inhibitors, there might be a small risk,” study lead author Søren Cold, MD, PhD, senior oncologist in the department of oncology at Odense (Denmark) University Hospital, Odense, said in an interview.

Moreover, Dr. Cold noted, while this study didn’t find an increased recurrence risk with MHT for women taking aromatase inhibitors, other studies have. One in particular was stopped because of harm. The reason for the difference here is likely that the previous sample was small – just 133 women.

“Our study is mainly focusing on the use of vaginal estrogen. We had so few patients using systemic menopausal hormone therapy, those data don’t mean much. ... The risk with systemic therapy has been established. The vaginal use hasn’t been thoroughly studied before,” he noted.

Breast cancer recurrence elevated with VET and aromatase inhibitors

The study pool was 9,710 women who underwent complete resection for estrogen-positive breast cancer and were all allocated to 5 years of adjuvant endocrine treatment or no adjuvant treatment, according to guidelines. Overall, 3,112 received no adjuvant endocrine treatment, 2,007 were treated with tamoxifen only, 403 with an aromatase inhibitor, and 2,939 with a sequence of tamoxifen and an aromatase inhibitor.

After exclusion of 1,249 who had received VET or MHT prior to breast cancer diagnosis, there were 6,391 not prescribed any estrogen hormonal treatment, 1,957 prescribed VET, and 133 prescribed MHT with or without VET.

During an estimated median 9.8 years’ follow-up, 1,333 women (16%) had a breast cancer recurrence. Of those, 111 had received VET, 16 MHT, and 1,206 neither. Compared with those receiving no hormonal treatment, the adjusted risk of recurrence was similar for the VET users (hazard ratio, 1.08; 95% confidence interval, 0.89-1.32).

However, there was an increased risk for recurrence associated with initiating VET during aromatase inhibitor treatment (HR, 1.39, 95% CI, 1.04-1.85). For women receiving MHT, the adjusted relative risk of recurrence with aromatase inhibitors wasn’t significant (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.62-1.78).

Overall, compared with women who never used hormonal treatment, the absolute 10-year breast cancer recurrence risk was 19.2% for never-users of VET or MHT, 15.4% in VET users, and 17.1% in MHT users.

No differences found for mortality

Of the 8,461 women in the study, 40% (3,370) died during an estimated median follow-up of 15.2 years. Of those, 497 had received VET, 47 MHT, and 2,826 neither. Compared with the never-users of estrogen therapy, the adjusted HR for overall survival in VET users was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.71-0.87). The analysis stratified by adjuvant endocrine therapy didn’t show an increase in VET users by use of aromatase inhibitors (aHR, 0.94, 95% CI, 0.70-1.26). The same was found for women prescribed MHT, compared with never-users (aHR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.70-1.26).

Never-users of VET or MHT had an absolute 10-year overall survival of 73.8% versus 79.5% and 80.5% among the women who used VET or MHT, respectively.

Asked to comment, Nanette Santoro, MD, professor and E. Stewart Taylor Chair of Obstetrics & Gynecology at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, said in an interview: “It is important to look at this issue. These findings raise but don’t answer the question that vaginal estradiol may not be as safe as we hope it is for women with breast cancer using an aromatase inhibitor.”

However, she also pointed out that “the overall increase in risk is not enormous; mortality risk was not increased. Women need to consider that there may be some risk associated with this option in their decision making about taking it. Having a satisfying sex life is also important for many women! It is really compassionate use for quality of life, so there is always that unknown element of risk in the discussion. That unknown risk has to be balanced against the benefit that the estrogen provides.”

And, Dr. Santoro also noted that the use of prescription data poses limitations. “It cannot tell us what was going on in the minds of the patient and the prescriber. There may be differences in the prescriber’s impression of the patient’s risk of recurrence that influenced the decision to provide a prescription. ... Women using AIs [aromatase inhibitors] often get pretty severe vaginal dryness symptoms and may need more estrogen to be comfortable with intercourse, but we really cannot tell this from what is in this paper.”

Indeed, Dr. Cold said: “We admit it’s not a randomized study, but we’ve done what was possible to take [confounding] factors into account, including age, tumor size, nodal status, histology, and comorbidities.”

He suggested that a potential therapeutic approach to reducing the recurrence risk might be to switch VET-treated women to tamoxifen after 2-3 years of aromatase inhibitors.

This work was supported by Breast Friends, a part of the Danish Cancer Society. Dr. Cold received support from Breast Friends for the current study. Some of the other coauthors have pharmaceutical company disclosures. Dr. Santoro is a member of the scientific advisory boards for Astellas, Menogenix, Que Oncology, and Amazon Ember, and is a consultant for Ansh Labs.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Former nurses of historic Black hospital sue to preserve its legacy

A training facility for Black doctors and nurses in St. Louis, which was the only public hospital for Black community from the late 1930s through the mid-1950s, has been at the center of many contentious community protests over the years and is facing another.

A federal lawsuit was filed recently by the nurses’ alumni of Homer G. Phillips Hospital against a St. Louis developer who is using the hospital’s name for a small for-profit urgent care health facility.

Homer G. Phillips was a St. Louis attorney and civic leader who joined with other Black leaders in 1922 to gain money for a hospital that would serve the Black community, according to online sources. He didn’t live to see the hospital named in his honor completed in 1937.

The former Homer G. Phillips Hospital closed in 1979 despite the community’s outcry at that time, according to The Missouri Independent. The building sat vacant for many years before being converted into a senior center, Yvonne Jones, alumni president, said in an interview.

She said of the new health center, which hasn’t opened yet, “We are not against the facility; we want to protect the name and legacy” of the original hospital, which remains at the heart of the historic St. Louis Black community.

At press time, the developer and his attorneys had not returned this news organization’s request for comment.

Having a new center with the name of the iconic hospital would mean that “the goodwill and the pride it represents has been usurped,” said Zenobia Thompson, who served as head nurse of Homer G. Phillips and is now the co-chair of the Change the Name Coalition. It formed last year after Ms. Thompson and others noticed a sign posted at the site of the new health center that lists it as the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, with a trademark symbol that the nurses say it doesn’t have a right to.

The coalition, which meets weekly, sponsored a petition and has been protesting at the site of the new center twice a month, Ms. Thompson said.

“We wrote a letter to [developer] Paul McKee that the legacy not be trivialized for commercial reasons,” Ms. Thompson said.

Richard Voytas, attorney for the alumni group, said in an interview that the developer did not ask permission from the nurses to use the trademark and he didn’t know if the nurses will grant that permission now. “If they [the developers] use the name, it is very important that they honor the Homer G. Phillips legacy,” Mr. Voytas said.

Honoring a legacy or taking advantage of a name?

In her new book, Climbing the Ladder, Chasing the Dream: A History of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, author Candace O’Connor cites the importance of the hospital’s heritage.

“Several nurses came from rural, impoverished backgrounds and went on to get jobs all across the country,” Ms. O’Connor wrote in the book. “Because all you had to do was say, ‘I’m from Homer Phillips,’ and they would say ‘you’re hired.’ It didn’t just change the nurse. It created opportunities for whole families.”

The area where the hospital remains once boasted a grocery store, high school, college, ice cream shop, and renowned Black churches, some of which still exist as historical sites. “They built up the area for Blacks who couldn’t go anywhere else,” Ms. Jones said.

In the suit, the alumni group describes itself as a 100-year-old philanthropic organization that brought healthcare to St. Louis’ historically underserved Black community and remains very active in the area today in fundraising and community outreach efforts. The group has been fighting with the developers since learning in 2019 about the proposed use of the name that is “confusingly similar” to the trademark and immediately voiced its objections via lawsuit, demanding that another name be chosen, stating:

“…in its name and efforts to market its for-profit urgent care facility immediately within plaintiff’s primary market to directly compete with plaintiff for name recognition and goodwill, only increases the likelihood of consumer confusion and, upon information and belief, represents an effort by defendants’ to pass off their products and services as those offered by plaintiff and its members.”

“Defendants stated purpose in using the mark, or a phrase confusingly similar to the mark, for its name is to ‘honor’ the name of Homer G. Phillips and to ‘emulate his spirit andtenacity in serving the health care needs of North St. Louis,’” the suit continues.

The St. Louis Board of Aldermen passed a resolution in December calling the use of the name for the new health center an “inappropriate cultural appropriation.” Mayor Tishaura Jones and Congresswoman Cori Bush followed that with a joint statement: “Profiting off of Homer G. Phillips’ name on a small 3-bed facility that will fail to meet the needs of the most vulnerable in our communities is an insult to Homer G. Phillips’ legacy and the Black community.”

The alumni group is requesting a jury trial and damages to be determined at trial, three times the defendant’s profits or plaintiffs’ damages, whichever is greater, along with attorneys’ fees and interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A training facility for Black doctors and nurses in St. Louis, which was the only public hospital for Black community from the late 1930s through the mid-1950s, has been at the center of many contentious community protests over the years and is facing another.

A federal lawsuit was filed recently by the nurses’ alumni of Homer G. Phillips Hospital against a St. Louis developer who is using the hospital’s name for a small for-profit urgent care health facility.

Homer G. Phillips was a St. Louis attorney and civic leader who joined with other Black leaders in 1922 to gain money for a hospital that would serve the Black community, according to online sources. He didn’t live to see the hospital named in his honor completed in 1937.

The former Homer G. Phillips Hospital closed in 1979 despite the community’s outcry at that time, according to The Missouri Independent. The building sat vacant for many years before being converted into a senior center, Yvonne Jones, alumni president, said in an interview.

She said of the new health center, which hasn’t opened yet, “We are not against the facility; we want to protect the name and legacy” of the original hospital, which remains at the heart of the historic St. Louis Black community.

At press time, the developer and his attorneys had not returned this news organization’s request for comment.

Having a new center with the name of the iconic hospital would mean that “the goodwill and the pride it represents has been usurped,” said Zenobia Thompson, who served as head nurse of Homer G. Phillips and is now the co-chair of the Change the Name Coalition. It formed last year after Ms. Thompson and others noticed a sign posted at the site of the new health center that lists it as the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, with a trademark symbol that the nurses say it doesn’t have a right to.

The coalition, which meets weekly, sponsored a petition and has been protesting at the site of the new center twice a month, Ms. Thompson said.

“We wrote a letter to [developer] Paul McKee that the legacy not be trivialized for commercial reasons,” Ms. Thompson said.

Richard Voytas, attorney for the alumni group, said in an interview that the developer did not ask permission from the nurses to use the trademark and he didn’t know if the nurses will grant that permission now. “If they [the developers] use the name, it is very important that they honor the Homer G. Phillips legacy,” Mr. Voytas said.

Honoring a legacy or taking advantage of a name?

In her new book, Climbing the Ladder, Chasing the Dream: A History of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, author Candace O’Connor cites the importance of the hospital’s heritage.

“Several nurses came from rural, impoverished backgrounds and went on to get jobs all across the country,” Ms. O’Connor wrote in the book. “Because all you had to do was say, ‘I’m from Homer Phillips,’ and they would say ‘you’re hired.’ It didn’t just change the nurse. It created opportunities for whole families.”

The area where the hospital remains once boasted a grocery store, high school, college, ice cream shop, and renowned Black churches, some of which still exist as historical sites. “They built up the area for Blacks who couldn’t go anywhere else,” Ms. Jones said.

In the suit, the alumni group describes itself as a 100-year-old philanthropic organization that brought healthcare to St. Louis’ historically underserved Black community and remains very active in the area today in fundraising and community outreach efforts. The group has been fighting with the developers since learning in 2019 about the proposed use of the name that is “confusingly similar” to the trademark and immediately voiced its objections via lawsuit, demanding that another name be chosen, stating:

“…in its name and efforts to market its for-profit urgent care facility immediately within plaintiff’s primary market to directly compete with plaintiff for name recognition and goodwill, only increases the likelihood of consumer confusion and, upon information and belief, represents an effort by defendants’ to pass off their products and services as those offered by plaintiff and its members.”

“Defendants stated purpose in using the mark, or a phrase confusingly similar to the mark, for its name is to ‘honor’ the name of Homer G. Phillips and to ‘emulate his spirit andtenacity in serving the health care needs of North St. Louis,’” the suit continues.

The St. Louis Board of Aldermen passed a resolution in December calling the use of the name for the new health center an “inappropriate cultural appropriation.” Mayor Tishaura Jones and Congresswoman Cori Bush followed that with a joint statement: “Profiting off of Homer G. Phillips’ name on a small 3-bed facility that will fail to meet the needs of the most vulnerable in our communities is an insult to Homer G. Phillips’ legacy and the Black community.”

The alumni group is requesting a jury trial and damages to be determined at trial, three times the defendant’s profits or plaintiffs’ damages, whichever is greater, along with attorneys’ fees and interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A training facility for Black doctors and nurses in St. Louis, which was the only public hospital for Black community from the late 1930s through the mid-1950s, has been at the center of many contentious community protests over the years and is facing another.

A federal lawsuit was filed recently by the nurses’ alumni of Homer G. Phillips Hospital against a St. Louis developer who is using the hospital’s name for a small for-profit urgent care health facility.

Homer G. Phillips was a St. Louis attorney and civic leader who joined with other Black leaders in 1922 to gain money for a hospital that would serve the Black community, according to online sources. He didn’t live to see the hospital named in his honor completed in 1937.

The former Homer G. Phillips Hospital closed in 1979 despite the community’s outcry at that time, according to The Missouri Independent. The building sat vacant for many years before being converted into a senior center, Yvonne Jones, alumni president, said in an interview.

She said of the new health center, which hasn’t opened yet, “We are not against the facility; we want to protect the name and legacy” of the original hospital, which remains at the heart of the historic St. Louis Black community.

At press time, the developer and his attorneys had not returned this news organization’s request for comment.

Having a new center with the name of the iconic hospital would mean that “the goodwill and the pride it represents has been usurped,” said Zenobia Thompson, who served as head nurse of Homer G. Phillips and is now the co-chair of the Change the Name Coalition. It formed last year after Ms. Thompson and others noticed a sign posted at the site of the new health center that lists it as the Homer G. Phillips Hospital, with a trademark symbol that the nurses say it doesn’t have a right to.

The coalition, which meets weekly, sponsored a petition and has been protesting at the site of the new center twice a month, Ms. Thompson said.

“We wrote a letter to [developer] Paul McKee that the legacy not be trivialized for commercial reasons,” Ms. Thompson said.

Richard Voytas, attorney for the alumni group, said in an interview that the developer did not ask permission from the nurses to use the trademark and he didn’t know if the nurses will grant that permission now. “If they [the developers] use the name, it is very important that they honor the Homer G. Phillips legacy,” Mr. Voytas said.

Honoring a legacy or taking advantage of a name?

In her new book, Climbing the Ladder, Chasing the Dream: A History of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, author Candace O’Connor cites the importance of the hospital’s heritage.

“Several nurses came from rural, impoverished backgrounds and went on to get jobs all across the country,” Ms. O’Connor wrote in the book. “Because all you had to do was say, ‘I’m from Homer Phillips,’ and they would say ‘you’re hired.’ It didn’t just change the nurse. It created opportunities for whole families.”

The area where the hospital remains once boasted a grocery store, high school, college, ice cream shop, and renowned Black churches, some of which still exist as historical sites. “They built up the area for Blacks who couldn’t go anywhere else,” Ms. Jones said.

In the suit, the alumni group describes itself as a 100-year-old philanthropic organization that brought healthcare to St. Louis’ historically underserved Black community and remains very active in the area today in fundraising and community outreach efforts. The group has been fighting with the developers since learning in 2019 about the proposed use of the name that is “confusingly similar” to the trademark and immediately voiced its objections via lawsuit, demanding that another name be chosen, stating:

“…in its name and efforts to market its for-profit urgent care facility immediately within plaintiff’s primary market to directly compete with plaintiff for name recognition and goodwill, only increases the likelihood of consumer confusion and, upon information and belief, represents an effort by defendants’ to pass off their products and services as those offered by plaintiff and its members.”

“Defendants stated purpose in using the mark, or a phrase confusingly similar to the mark, for its name is to ‘honor’ the name of Homer G. Phillips and to ‘emulate his spirit andtenacity in serving the health care needs of North St. Louis,’” the suit continues.

The St. Louis Board of Aldermen passed a resolution in December calling the use of the name for the new health center an “inappropriate cultural appropriation.” Mayor Tishaura Jones and Congresswoman Cori Bush followed that with a joint statement: “Profiting off of Homer G. Phillips’ name on a small 3-bed facility that will fail to meet the needs of the most vulnerable in our communities is an insult to Homer G. Phillips’ legacy and the Black community.”

The alumni group is requesting a jury trial and damages to be determined at trial, three times the defendant’s profits or plaintiffs’ damages, whichever is greater, along with attorneys’ fees and interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Parkinson’s disease: Is copper culpable?

, according to investigators. The techniques used in this research also may enable rapid identification of blood-borne cofactors driving abnormal protein development in a range of other neurodegenerative diseases, reported lead author Olena Synhaivska, MSc, of the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

“While alpha‑synuclein oligomers are the known neurotoxic species in Parkinson’s disease, the development of effective anti–Parkinson’s disease drugs requires targeting of specific structures arising in the early stages of alpha‑synuclein phase transitions or the nucleation-dependent elongation of oligomers into protofibrils,” the investigators wrote in ACS Chemical Neuroscience. “In parallel, advanced methods are required to routinely characterize the size and morphology of intermediary nano- and microstructures formed during self-assembly and aggregation in the presence of aqueous metal ions to track disease progression in, for example, a blood test, to provide effective personalized patient care.”

Pathologic aggregation of alpha‑synuclein

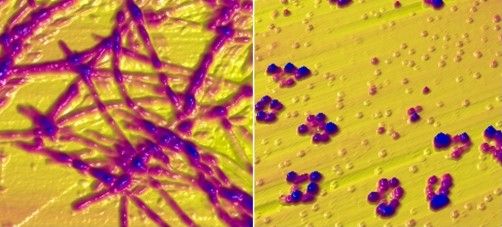

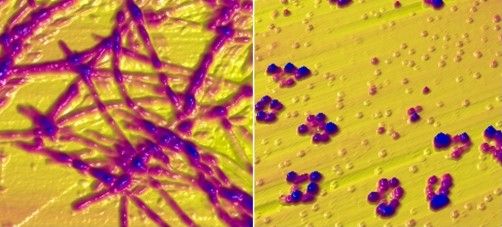

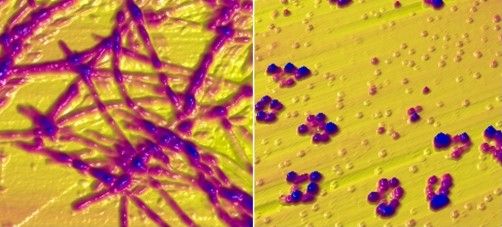

To better understand the relationship between copper and alpha‑synuclein, the investigators used liquid-based atomic force microscopy to observe the protein in solution over 10 days as it transitioned from a simple monomer to a complex, three-dimensional aggregate. Protein aggregation occurred in the absence or presence of copper; however, when incubated in solution with Cu2+ ions, alpha‑synuclein aggregated faster, predominantly forming annular (ring-shaped) structures that were not observed in the absence of copper.

These annular oligomers are noteworthy because they are cytotoxic, and they nucleate formation of alpha‑synuclein filaments, meaning they could serve as early therapeutic targets, according to the investigators.

The above experiments were supported by Raman spectroscopy, which confirmed the various superstructures of alpha‑synuclein formed with or without copper. In addition, the investigators used molecular dynamics computer simulations to map “the dimensions, supramolecular packing interactions, and thermodynamic stabilities” involved in aggregation.

These findings “could potentially serve as guidelines for better understanding protein aggregated states in body fluids from individuals who have been exposed to environmental metals over their lifetime,” the investigators wrote. “The nanoscale imaging, chemical spectroscopy, and integrated modeling-measurement methodologies presented here may inform rapid screening of other potential blood-borne cofactors, for example, other biometals, heavy metals, physiological amino acids, and metabolites, in directing and potentially rerouting intrinsically disordered protein aggregation in the initiation and pathology of neurodegenerative diseases.”

What is copper’s role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis?

In a joint written comment, Vikram Khurana MD, PhD, and Richard Krolewski MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said, “This study is important in that it demonstrates that the presence of copper can accelerate and alter the aggregation of wild type alpha‑synuclein. We know that pathologic aggregation of alpha‑synuclein is critical for diseases like Parkinson’s disease known as synucleinopathies – so any insight into how this is happening at the biophysical level has potential implications for altering that process.”

While Dr. Khurana and Dr. Krolewski praised the elegance of the study, including the techniques used to observe alpha‑synuclein aggregation in near real-time, they suggested that more work is needed to determine relevance for patients with Parkinson’s disease.

“It is not clear whether this process is happening in cells, how alpha‑synuclein fibrils might be directly exposed to copper intracellularly (with most of the copper being bound to proteins), and the relevance of the copper concentrations used here are in question,” they said. “Substantially more cell biology and in vivo modeling would be needed to further evaluate the connection of copper specifically to synucleinopathy. All this notwithstanding, the findings are exciting and intriguing and definitely warrant follow-up.”

In the meantime, an increasing number of studies, including a recent preprint by Dr. Khurana and Dr. Krolewski, are strengthening the case for a link between copper exposure and Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. This body of evidence, they noted, “now spans epidemiology, cell biology, and biophysics.”

Their study, which tested 53 pesticides associated with Parkinson’s disease in patient-derived pluripotent stem cells, found that 2 out of 10 pesticides causing cell death were copper compounds.

“Ongoing work will explore the mechanism of this cell death and investigate ways to mitigate it,” said Dr. Khurana and Dr. Krolewski. “Our hope is that this line of research will raise public awareness about these and other pesticides to reduce potential harm from their use and highlight protective approaches. The study by Dr. Synhaivska and colleagues now raises the possibility of new mechanisms.”

The study by Dr. Synhaivska and colleagues was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Science Foundation Ireland. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Krolewski has been retained as an expert consultant for plaintiffs in a lawsuit on the role of pesticides in Parkinson’s disease causation.

, according to investigators. The techniques used in this research also may enable rapid identification of blood-borne cofactors driving abnormal protein development in a range of other neurodegenerative diseases, reported lead author Olena Synhaivska, MSc, of the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

“While alpha‑synuclein oligomers are the known neurotoxic species in Parkinson’s disease, the development of effective anti–Parkinson’s disease drugs requires targeting of specific structures arising in the early stages of alpha‑synuclein phase transitions or the nucleation-dependent elongation of oligomers into protofibrils,” the investigators wrote in ACS Chemical Neuroscience. “In parallel, advanced methods are required to routinely characterize the size and morphology of intermediary nano- and microstructures formed during self-assembly and aggregation in the presence of aqueous metal ions to track disease progression in, for example, a blood test, to provide effective personalized patient care.”

Pathologic aggregation of alpha‑synuclein

To better understand the relationship between copper and alpha‑synuclein, the investigators used liquid-based atomic force microscopy to observe the protein in solution over 10 days as it transitioned from a simple monomer to a complex, three-dimensional aggregate. Protein aggregation occurred in the absence or presence of copper; however, when incubated in solution with Cu2+ ions, alpha‑synuclein aggregated faster, predominantly forming annular (ring-shaped) structures that were not observed in the absence of copper.

These annular oligomers are noteworthy because they are cytotoxic, and they nucleate formation of alpha‑synuclein filaments, meaning they could serve as early therapeutic targets, according to the investigators.

The above experiments were supported by Raman spectroscopy, which confirmed the various superstructures of alpha‑synuclein formed with or without copper. In addition, the investigators used molecular dynamics computer simulations to map “the dimensions, supramolecular packing interactions, and thermodynamic stabilities” involved in aggregation.

These findings “could potentially serve as guidelines for better understanding protein aggregated states in body fluids from individuals who have been exposed to environmental metals over their lifetime,” the investigators wrote. “The nanoscale imaging, chemical spectroscopy, and integrated modeling-measurement methodologies presented here may inform rapid screening of other potential blood-borne cofactors, for example, other biometals, heavy metals, physiological amino acids, and metabolites, in directing and potentially rerouting intrinsically disordered protein aggregation in the initiation and pathology of neurodegenerative diseases.”

What is copper’s role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis?

In a joint written comment, Vikram Khurana MD, PhD, and Richard Krolewski MD, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said, “This study is important in that it demonstrates that the presence of copper can accelerate and alter the aggregation of wild type alpha‑synuclein. We know that pathologic aggregation of alpha‑synuclein is critical for diseases like Parkinson’s disease known as synucleinopathies – so any insight into how this is happening at the biophysical level has potential implications for altering that process.”

While Dr. Khurana and Dr. Krolewski praised the elegance of the study, including the techniques used to observe alpha‑synuclein aggregation in near real-time, they suggested that more work is needed to determine relevance for patients with Parkinson’s disease.

“It is not clear whether this process is happening in cells, how alpha‑synuclein fibrils might be directly exposed to copper intracellularly (with most of the copper being bound to proteins), and the relevance of the copper concentrations used here are in question,” they said. “Substantially more cell biology and in vivo modeling would be needed to further evaluate the connection of copper specifically to synucleinopathy. All this notwithstanding, the findings are exciting and intriguing and definitely warrant follow-up.”

In the meantime, an increasing number of studies, including a recent preprint by Dr. Khurana and Dr. Krolewski, are strengthening the case for a link between copper exposure and Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. This body of evidence, they noted, “now spans epidemiology, cell biology, and biophysics.”

Their study, which tested 53 pesticides associated with Parkinson’s disease in patient-derived pluripotent stem cells, found that 2 out of 10 pesticides causing cell death were copper compounds.

“Ongoing work will explore the mechanism of this cell death and investigate ways to mitigate it,” said Dr. Khurana and Dr. Krolewski. “Our hope is that this line of research will raise public awareness about these and other pesticides to reduce potential harm from their use and highlight protective approaches. The study by Dr. Synhaivska and colleagues now raises the possibility of new mechanisms.”

The study by Dr. Synhaivska and colleagues was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Science Foundation Ireland. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Krolewski has been retained as an expert consultant for plaintiffs in a lawsuit on the role of pesticides in Parkinson’s disease causation.

, according to investigators. The techniques used in this research also may enable rapid identification of blood-borne cofactors driving abnormal protein development in a range of other neurodegenerative diseases, reported lead author Olena Synhaivska, MSc, of the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, Dübendorf, Switzerland.

“While alpha‑synuclein oligomers are the known neurotoxic species in Parkinson’s disease, the development of effective anti–Parkinson’s disease drugs requires targeting of specific structures arising in the early stages of alpha‑synuclein phase transitions or the nucleation-dependent elongation of oligomers into protofibrils,” the investigators wrote in ACS Chemical Neuroscience. “In parallel, advanced methods are required to routinely characterize the size and morphology of intermediary nano- and microstructures formed during self-assembly and aggregation in the presence of aqueous metal ions to track disease progression in, for example, a blood test, to provide effective personalized patient care.”

Pathologic aggregation of alpha‑synuclein