User login

AGA Clinical Practice Update: Expert review of dietary options for IBS

The American Gastroenterological Association has published a clinical practice update on dietary interventions for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The topics range from identification of suitable candidates for dietary interventions, to levels of evidence for specific diets, which are becoming increasingly recognized for their key role in managing patients with IBS, according to lead author William D. Chey, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“Most medical therapies for IBS improve global symptoms in fewer than one-half of patients, with a therapeutic gain of 7%-15% over placebo,” the researchers wrote in Gastroenterology. “Most patients with IBS associate their GI symptoms with eating food.”

According to Dr. Chey and colleagues, clinicians who are considering dietary modifications for treating IBS should first recognize the inherent challenges presented by this process and be aware that new diets won’t work for everyone.

“Specialty diets require planning and preparation, which may be impractical for some patients,” they wrote, noting that individuals with “decreased cognitive abilities and significant psychiatric disease” may be unable to follow diets or interpret their own responses to specific foods. Special diets may also be inappropriate for patients with financial constraints, and “should be avoided in patients with an eating disorder.”

Because of the challenges involved in dietary interventions, Dr. Chey and colleagues advised clinical support from a registered dietitian nutritionist or other resource.

Patients who are suitable candidates for intervention and willing to try a new diet should first provide information about their current eating habits. A food trial can then be personalized and implemented for a predetermined amount of time. If the patient does not respond, then the diet should be stopped and changed to a new diet or another intervention.

Dr. Chey and colleagues discussed three specific dietary interventions and their corresponding levels of evidence: soluble fiber; the low-fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet; and a gluten-free diet.

“Soluble fiber is efficacious in treating global symptoms of IBS,” they wrote, citing 15 randomized controlled trials. Soluble fiber is most suitable for patients with constipation-predominant IBS, and different soluble fibers may yield different outcomes based on characteristics such as rate of fermentation and viscosity. In contrast, insoluble fiber is unlikely to help with IBS, and may worsen abdominal pain and bloating.

The low-FODMAP diet is “currently the most evidence-based diet intervention for IBS,” especially for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Dr. Chey and colleagues offered a clear roadmap for employing the diet. First, patients should eat only low-FODMAP foods for 4-6 weeks. If symptoms don’t improve, the diet should be stopped. If symptoms do improve, foods containing a single FODMAP should be reintroduced one at a time, each in increasing quantities over 3 days, alongside documentation of symptom responses. Finally, the diet should be personalized based on these responses. The majority of patients (close to 80%) “can liberalize” a low-FODMAP diet based on their responses.

In contrast with the low-FODMAP diet, which has a relatively solid body of supporting evidence, efficacy data are still limited for treating IBS with a gluten-free diet. “Although observational studies found that most patients with IBS improve with a gluten-free diet, randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results,” Dr. Chey and colleagues explained.

Their report cited a recent monograph on the topic that concluded that gluten-free eating offered no significant benefit over placebo (relative risk, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-1.28). While some studies have documented positive results with a gluten-free diet, Dr. Chey and colleagues suggested that confounding variables such as the nocebo effect and the impact of other dietary factors have yet to be ruled out. “At present, it remains unclear whether a gluten-free diet is of benefit to patients with IBS.”

Dr. Chey and colleagues also explored IBS biomarkers. While some early data have shown that biomarkers may predict dietary responses, “there is insufficient evidence to support their routine use in clinical practice. ... Further efforts to identify and validate biomarkers that predict response to dietary interventions are needed to deliver ‘personalized nutrition.’ ”

The clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by the AGA CPU Committee and the AGA Governing Board. The researchers disclosed relationships with Biomerica, Salix, Mauna Kea Technologies, and others.

This article was updated May 19, 2022.

The American Gastroenterological Association has published a clinical practice update on dietary interventions for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The topics range from identification of suitable candidates for dietary interventions, to levels of evidence for specific diets, which are becoming increasingly recognized for their key role in managing patients with IBS, according to lead author William D. Chey, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“Most medical therapies for IBS improve global symptoms in fewer than one-half of patients, with a therapeutic gain of 7%-15% over placebo,” the researchers wrote in Gastroenterology. “Most patients with IBS associate their GI symptoms with eating food.”

According to Dr. Chey and colleagues, clinicians who are considering dietary modifications for treating IBS should first recognize the inherent challenges presented by this process and be aware that new diets won’t work for everyone.

“Specialty diets require planning and preparation, which may be impractical for some patients,” they wrote, noting that individuals with “decreased cognitive abilities and significant psychiatric disease” may be unable to follow diets or interpret their own responses to specific foods. Special diets may also be inappropriate for patients with financial constraints, and “should be avoided in patients with an eating disorder.”

Because of the challenges involved in dietary interventions, Dr. Chey and colleagues advised clinical support from a registered dietitian nutritionist or other resource.

Patients who are suitable candidates for intervention and willing to try a new diet should first provide information about their current eating habits. A food trial can then be personalized and implemented for a predetermined amount of time. If the patient does not respond, then the diet should be stopped and changed to a new diet or another intervention.

Dr. Chey and colleagues discussed three specific dietary interventions and their corresponding levels of evidence: soluble fiber; the low-fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet; and a gluten-free diet.

“Soluble fiber is efficacious in treating global symptoms of IBS,” they wrote, citing 15 randomized controlled trials. Soluble fiber is most suitable for patients with constipation-predominant IBS, and different soluble fibers may yield different outcomes based on characteristics such as rate of fermentation and viscosity. In contrast, insoluble fiber is unlikely to help with IBS, and may worsen abdominal pain and bloating.

The low-FODMAP diet is “currently the most evidence-based diet intervention for IBS,” especially for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Dr. Chey and colleagues offered a clear roadmap for employing the diet. First, patients should eat only low-FODMAP foods for 4-6 weeks. If symptoms don’t improve, the diet should be stopped. If symptoms do improve, foods containing a single FODMAP should be reintroduced one at a time, each in increasing quantities over 3 days, alongside documentation of symptom responses. Finally, the diet should be personalized based on these responses. The majority of patients (close to 80%) “can liberalize” a low-FODMAP diet based on their responses.

In contrast with the low-FODMAP diet, which has a relatively solid body of supporting evidence, efficacy data are still limited for treating IBS with a gluten-free diet. “Although observational studies found that most patients with IBS improve with a gluten-free diet, randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results,” Dr. Chey and colleagues explained.

Their report cited a recent monograph on the topic that concluded that gluten-free eating offered no significant benefit over placebo (relative risk, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-1.28). While some studies have documented positive results with a gluten-free diet, Dr. Chey and colleagues suggested that confounding variables such as the nocebo effect and the impact of other dietary factors have yet to be ruled out. “At present, it remains unclear whether a gluten-free diet is of benefit to patients with IBS.”

Dr. Chey and colleagues also explored IBS biomarkers. While some early data have shown that biomarkers may predict dietary responses, “there is insufficient evidence to support their routine use in clinical practice. ... Further efforts to identify and validate biomarkers that predict response to dietary interventions are needed to deliver ‘personalized nutrition.’ ”

The clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by the AGA CPU Committee and the AGA Governing Board. The researchers disclosed relationships with Biomerica, Salix, Mauna Kea Technologies, and others.

This article was updated May 19, 2022.

The American Gastroenterological Association has published a clinical practice update on dietary interventions for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The topics range from identification of suitable candidates for dietary interventions, to levels of evidence for specific diets, which are becoming increasingly recognized for their key role in managing patients with IBS, according to lead author William D. Chey, MD, of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and colleagues.

“Most medical therapies for IBS improve global symptoms in fewer than one-half of patients, with a therapeutic gain of 7%-15% over placebo,” the researchers wrote in Gastroenterology. “Most patients with IBS associate their GI symptoms with eating food.”

According to Dr. Chey and colleagues, clinicians who are considering dietary modifications for treating IBS should first recognize the inherent challenges presented by this process and be aware that new diets won’t work for everyone.

“Specialty diets require planning and preparation, which may be impractical for some patients,” they wrote, noting that individuals with “decreased cognitive abilities and significant psychiatric disease” may be unable to follow diets or interpret their own responses to specific foods. Special diets may also be inappropriate for patients with financial constraints, and “should be avoided in patients with an eating disorder.”

Because of the challenges involved in dietary interventions, Dr. Chey and colleagues advised clinical support from a registered dietitian nutritionist or other resource.

Patients who are suitable candidates for intervention and willing to try a new diet should first provide information about their current eating habits. A food trial can then be personalized and implemented for a predetermined amount of time. If the patient does not respond, then the diet should be stopped and changed to a new diet or another intervention.

Dr. Chey and colleagues discussed three specific dietary interventions and their corresponding levels of evidence: soluble fiber; the low-fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet; and a gluten-free diet.

“Soluble fiber is efficacious in treating global symptoms of IBS,” they wrote, citing 15 randomized controlled trials. Soluble fiber is most suitable for patients with constipation-predominant IBS, and different soluble fibers may yield different outcomes based on characteristics such as rate of fermentation and viscosity. In contrast, insoluble fiber is unlikely to help with IBS, and may worsen abdominal pain and bloating.

The low-FODMAP diet is “currently the most evidence-based diet intervention for IBS,” especially for patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS. Dr. Chey and colleagues offered a clear roadmap for employing the diet. First, patients should eat only low-FODMAP foods for 4-6 weeks. If symptoms don’t improve, the diet should be stopped. If symptoms do improve, foods containing a single FODMAP should be reintroduced one at a time, each in increasing quantities over 3 days, alongside documentation of symptom responses. Finally, the diet should be personalized based on these responses. The majority of patients (close to 80%) “can liberalize” a low-FODMAP diet based on their responses.

In contrast with the low-FODMAP diet, which has a relatively solid body of supporting evidence, efficacy data are still limited for treating IBS with a gluten-free diet. “Although observational studies found that most patients with IBS improve with a gluten-free diet, randomized controlled trials have yielded mixed results,” Dr. Chey and colleagues explained.

Their report cited a recent monograph on the topic that concluded that gluten-free eating offered no significant benefit over placebo (relative risk, 0.46; 95% confidence interval, 0.16-1.28). While some studies have documented positive results with a gluten-free diet, Dr. Chey and colleagues suggested that confounding variables such as the nocebo effect and the impact of other dietary factors have yet to be ruled out. “At present, it remains unclear whether a gluten-free diet is of benefit to patients with IBS.”

Dr. Chey and colleagues also explored IBS biomarkers. While some early data have shown that biomarkers may predict dietary responses, “there is insufficient evidence to support their routine use in clinical practice. ... Further efforts to identify and validate biomarkers that predict response to dietary interventions are needed to deliver ‘personalized nutrition.’ ”

The clinical practice update was commissioned and approved by the AGA CPU Committee and the AGA Governing Board. The researchers disclosed relationships with Biomerica, Salix, Mauna Kea Technologies, and others.

This article was updated May 19, 2022.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Taking cardiac pacing from boring to super cool

For the past 2 decades, catheter ablation stole most of the excitement in electrophysiology. Cardiac pacing was seen as necessary but boring. His-bundle pacing earned only modest attention.

But at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, cardiac pacing consolidated its comeback and entered the super-cool category.

Not one but three late-breaking clinical trials considered the role of pacing the heart’s conduction system for both preventive and therapeutic purposes. Conduction system pacing, or CSP as we call it, includes pacing the His bundle or the left bundle branch. Left bundle–branch pacing has now largely replaced His-bundle pacing.

Before I tell you about the studies, let’s review why CSP disrupts the status quo.

The core idea goes back to basic physiology: After the impulse leaves the atrioventricular node, the heart’s specialized conduction system allows rapid and synchronous conduction to both the right and left ventricles.

Standard cardiac pacing means fixing a pacing lead into the muscle of the right ventricle. From that spot, conduction spreads via slower muscle-to-muscle conduction, which leads to a wide QRS complex and the right ventricle contracts before the left ventricle.

While such dyssynchronous contraction is better than no contraction, this approach leads to a pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in a substantial number of cases. (The incidence reported in many studies varies widely.)

The most disruptive effect of conduction system pacing is that it is a form of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). And that is nifty because, until recently, resynchronizing the ventricles required placing two ventricular leads: one in the right ventricle and the other in the coronary sinus to pace the left ventricle.

Left bundle-branch pacing vs. biventricular pacing

The first of the three HRS studies is the LBBP-RESYNC randomized controlled trial led by Jiangang Zou, MD, PhD, and performed in multiple centers in China. It compared the efficacy of left bundle–branch pacing (LBBP) with that of conventional biventricular pacing in 40 patients with heart failure who were eligible for CRT. The primary endpoint was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from baseline to 6-month follow-up.

The results favored LBBP. Although both pacing techniques improved LVEF from baseline, the between-group difference in LVEF was greater in the LBBP arm than the biventricular pacing arm by a statistically significant 5.6% (95% confidence interval, 0.3%-10.9%). Secondary endpoints, such as reductions in left ventricular end-systolic volume, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, and QRS duration, also favored LBBP.

Conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing

A second late-breaking study, from the Geisinger group, led by Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, was simultaneously published in Heart Rhythm.

This nonrandomized observational study compared nearly 500 patients eligible for CRT treated at two health systems. One group favors conduction system pacing and the other does traditional biventricular pacing, which set up a two-armed comparison.

CSP was accomplished by LBBP (65%) and His-bundle pacing (35%).

The primary endpoint of death or first hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 28.3% of patients in the CSP arm versus 38.4% of the biventricular arm (hazard ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.08-2.09). QRS duration and LVEF also improved from baseline in both groups.

LBB area pacing as a bailout for failed CRT

The Geisinger group also presented and published an international multicenter study that assessed the feasibility of LBBP as a bailout when standard biventricular pacing did not work – because of inadequate coronary sinus anatomy or CRT nonresponse, defined as lack of clinical or echocardiographic improvement.

This series included 212 patients in whom CRT failed and who underwent attempted LBBP pacing. The bailout was successful in 200 patients (91%). The primary endpoint was defined as an increase in LVEF above 5% on echocardiography.

During 12-month follow-up, 61% of patients had an improvement in LVEF above 5% and nearly 30% had a “super-response,” defined as a 20% or greater increase or normalization of LVEF. Similar to the previous studies, LBBP resulted in shorter QRS duration and improved echocardiography parameters.

Am I persuaded?

I was an early adopter of His-bundle pacing. When successful, it delivered both aesthetically pleasing QRS complexes and clinical efficacy. But there were many challenges: it is technically difficult, and capture thresholds are often high at implant and get higher over time, which leads to shorter battery life.

Pacing the left bundle branch mitigates these challenges. Here, the operator approaches from the right side and screws the lead a few millimeters into the septum, so the tip of the lead can capture the left bundle or one of its branches. This allows activation of the heart’s specialized conduction system and thus synchronizes right and left ventricle contraction.

Although there is a learning curve, LBBP is technically easier than His-bundle pacing and ultimately results in far better pacing and sensing parameters. What’s more, the preferred lead for LBBP has a stellar efficacy record – over years.

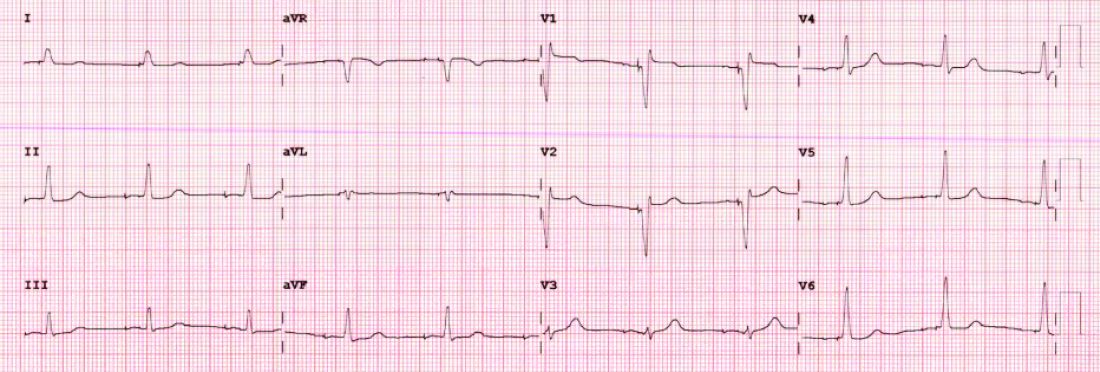

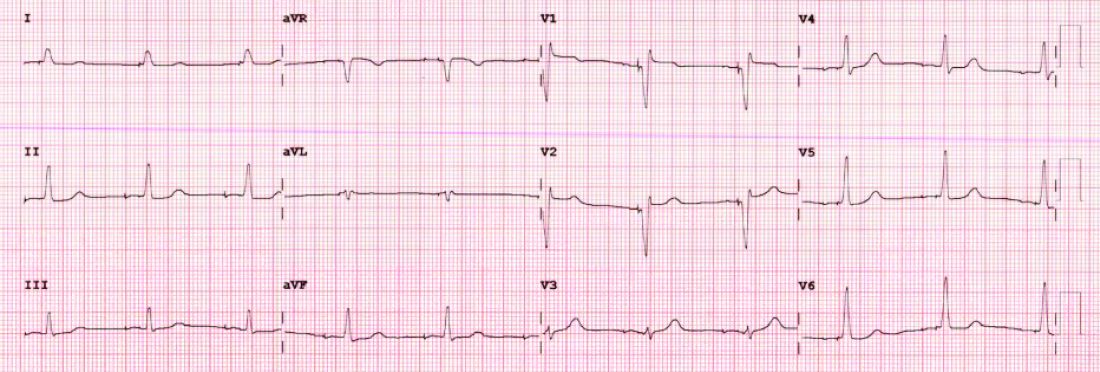

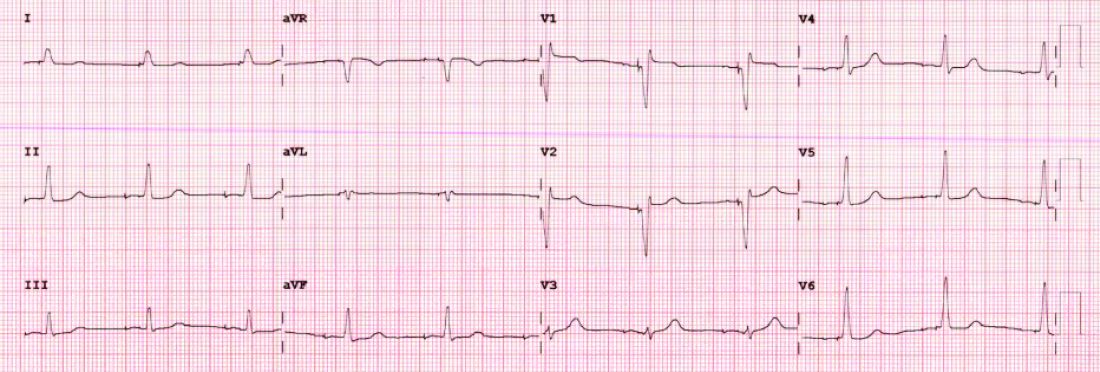

I have become enthralled by the gorgeous QRS complexes from LBBP. The ability to pace the heart without creating dyssynchrony infuses me with joy. I chose cardiology largely because of the beauty of the ECG.

But as a medical conservative who is cautious about unproven therapies, I have questions. How is LBBP defined? Is left septal pacing good enough, or do you need actual left bundle capture? What about long-term performance of a lead in the septum?

Biventricular pacing has set a high bar because it has been proven effective for reducing hard clinical outcomes in large randomized controlled trials.

The studies at HRS begin to answer these questions. The randomized controlled trial from China supports the notion that effective LBBP (the investigators rigorously defined left bundle capture) leads to favorable effects on cardiac contraction. The two observational studies reported similarly encouraging findings on cardiac function.

The three studies therefore tentatively support the notion that LBBP actually produces favorable cardiac performance.

Whether LBBP leads to better clinical outcomes remains uncertain. The nonrandomized comparison study, which found better hard outcomes in the CSP arm, cannot be used to infer causality. There is too much risk for selection bias.

But the LBBP bailout study does suggest that this strategy is reasonable when coronary sinus leads fail – especially since the alternative is surgical placement of an epicardial lead on the left ventricle.

At minimum, the HRS studies persuade me that LBBP will likely prevent pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. If I or a family member required a pacemaker, I’d surely want the operator to be skilled at placing a left bundle lead.

While I am confident that conduction system pacing will become a transformative advance in cardiac pacing, aesthetically pleasing ECG patterns are not enough. There remains much to learn with this nascent approach.

The barriers to getting more CSP trials

The challenge going forward will be funding new trials. CSP stands to prevent pacing-induced cardiomyopathy and offer less costly alternatives to standard biventricular pacing for CRT. This is great for patients, but it would mean that fewer higher-cost CRT devices will be sold.

Heart rhythm research is largely industry-funded because in most cases better therapies for patients mean more profits for industry. In the case of CSP, there is no such confluence of interests.

Conduction system pacing has come about because of the efforts of a few tireless champions who not only published extensively but were also skilled at using social media to spread the excitement. Trials have been small and often self-funded.

The data presented at HRS provides enough equipoise to support a large outcomes-based randomized controlled trial. Imagine if our CSP champions were able to find public-funding sources for such future trials.

Now that would be super cool.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For the past 2 decades, catheter ablation stole most of the excitement in electrophysiology. Cardiac pacing was seen as necessary but boring. His-bundle pacing earned only modest attention.

But at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, cardiac pacing consolidated its comeback and entered the super-cool category.

Not one but three late-breaking clinical trials considered the role of pacing the heart’s conduction system for both preventive and therapeutic purposes. Conduction system pacing, or CSP as we call it, includes pacing the His bundle or the left bundle branch. Left bundle–branch pacing has now largely replaced His-bundle pacing.

Before I tell you about the studies, let’s review why CSP disrupts the status quo.

The core idea goes back to basic physiology: After the impulse leaves the atrioventricular node, the heart’s specialized conduction system allows rapid and synchronous conduction to both the right and left ventricles.

Standard cardiac pacing means fixing a pacing lead into the muscle of the right ventricle. From that spot, conduction spreads via slower muscle-to-muscle conduction, which leads to a wide QRS complex and the right ventricle contracts before the left ventricle.

While such dyssynchronous contraction is better than no contraction, this approach leads to a pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in a substantial number of cases. (The incidence reported in many studies varies widely.)

The most disruptive effect of conduction system pacing is that it is a form of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). And that is nifty because, until recently, resynchronizing the ventricles required placing two ventricular leads: one in the right ventricle and the other in the coronary sinus to pace the left ventricle.

Left bundle-branch pacing vs. biventricular pacing

The first of the three HRS studies is the LBBP-RESYNC randomized controlled trial led by Jiangang Zou, MD, PhD, and performed in multiple centers in China. It compared the efficacy of left bundle–branch pacing (LBBP) with that of conventional biventricular pacing in 40 patients with heart failure who were eligible for CRT. The primary endpoint was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from baseline to 6-month follow-up.

The results favored LBBP. Although both pacing techniques improved LVEF from baseline, the between-group difference in LVEF was greater in the LBBP arm than the biventricular pacing arm by a statistically significant 5.6% (95% confidence interval, 0.3%-10.9%). Secondary endpoints, such as reductions in left ventricular end-systolic volume, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, and QRS duration, also favored LBBP.

Conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing

A second late-breaking study, from the Geisinger group, led by Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, was simultaneously published in Heart Rhythm.

This nonrandomized observational study compared nearly 500 patients eligible for CRT treated at two health systems. One group favors conduction system pacing and the other does traditional biventricular pacing, which set up a two-armed comparison.

CSP was accomplished by LBBP (65%) and His-bundle pacing (35%).

The primary endpoint of death or first hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 28.3% of patients in the CSP arm versus 38.4% of the biventricular arm (hazard ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.08-2.09). QRS duration and LVEF also improved from baseline in both groups.

LBB area pacing as a bailout for failed CRT

The Geisinger group also presented and published an international multicenter study that assessed the feasibility of LBBP as a bailout when standard biventricular pacing did not work – because of inadequate coronary sinus anatomy or CRT nonresponse, defined as lack of clinical or echocardiographic improvement.

This series included 212 patients in whom CRT failed and who underwent attempted LBBP pacing. The bailout was successful in 200 patients (91%). The primary endpoint was defined as an increase in LVEF above 5% on echocardiography.

During 12-month follow-up, 61% of patients had an improvement in LVEF above 5% and nearly 30% had a “super-response,” defined as a 20% or greater increase or normalization of LVEF. Similar to the previous studies, LBBP resulted in shorter QRS duration and improved echocardiography parameters.

Am I persuaded?

I was an early adopter of His-bundle pacing. When successful, it delivered both aesthetically pleasing QRS complexes and clinical efficacy. But there were many challenges: it is technically difficult, and capture thresholds are often high at implant and get higher over time, which leads to shorter battery life.

Pacing the left bundle branch mitigates these challenges. Here, the operator approaches from the right side and screws the lead a few millimeters into the septum, so the tip of the lead can capture the left bundle or one of its branches. This allows activation of the heart’s specialized conduction system and thus synchronizes right and left ventricle contraction.

Although there is a learning curve, LBBP is technically easier than His-bundle pacing and ultimately results in far better pacing and sensing parameters. What’s more, the preferred lead for LBBP has a stellar efficacy record – over years.

I have become enthralled by the gorgeous QRS complexes from LBBP. The ability to pace the heart without creating dyssynchrony infuses me with joy. I chose cardiology largely because of the beauty of the ECG.

But as a medical conservative who is cautious about unproven therapies, I have questions. How is LBBP defined? Is left septal pacing good enough, or do you need actual left bundle capture? What about long-term performance of a lead in the septum?

Biventricular pacing has set a high bar because it has been proven effective for reducing hard clinical outcomes in large randomized controlled trials.

The studies at HRS begin to answer these questions. The randomized controlled trial from China supports the notion that effective LBBP (the investigators rigorously defined left bundle capture) leads to favorable effects on cardiac contraction. The two observational studies reported similarly encouraging findings on cardiac function.

The three studies therefore tentatively support the notion that LBBP actually produces favorable cardiac performance.

Whether LBBP leads to better clinical outcomes remains uncertain. The nonrandomized comparison study, which found better hard outcomes in the CSP arm, cannot be used to infer causality. There is too much risk for selection bias.

But the LBBP bailout study does suggest that this strategy is reasonable when coronary sinus leads fail – especially since the alternative is surgical placement of an epicardial lead on the left ventricle.

At minimum, the HRS studies persuade me that LBBP will likely prevent pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. If I or a family member required a pacemaker, I’d surely want the operator to be skilled at placing a left bundle lead.

While I am confident that conduction system pacing will become a transformative advance in cardiac pacing, aesthetically pleasing ECG patterns are not enough. There remains much to learn with this nascent approach.

The barriers to getting more CSP trials

The challenge going forward will be funding new trials. CSP stands to prevent pacing-induced cardiomyopathy and offer less costly alternatives to standard biventricular pacing for CRT. This is great for patients, but it would mean that fewer higher-cost CRT devices will be sold.

Heart rhythm research is largely industry-funded because in most cases better therapies for patients mean more profits for industry. In the case of CSP, there is no such confluence of interests.

Conduction system pacing has come about because of the efforts of a few tireless champions who not only published extensively but were also skilled at using social media to spread the excitement. Trials have been small and often self-funded.

The data presented at HRS provides enough equipoise to support a large outcomes-based randomized controlled trial. Imagine if our CSP champions were able to find public-funding sources for such future trials.

Now that would be super cool.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For the past 2 decades, catheter ablation stole most of the excitement in electrophysiology. Cardiac pacing was seen as necessary but boring. His-bundle pacing earned only modest attention.

But at the annual scientific sessions of the Heart Rhythm Society, cardiac pacing consolidated its comeback and entered the super-cool category.

Not one but three late-breaking clinical trials considered the role of pacing the heart’s conduction system for both preventive and therapeutic purposes. Conduction system pacing, or CSP as we call it, includes pacing the His bundle or the left bundle branch. Left bundle–branch pacing has now largely replaced His-bundle pacing.

Before I tell you about the studies, let’s review why CSP disrupts the status quo.

The core idea goes back to basic physiology: After the impulse leaves the atrioventricular node, the heart’s specialized conduction system allows rapid and synchronous conduction to both the right and left ventricles.

Standard cardiac pacing means fixing a pacing lead into the muscle of the right ventricle. From that spot, conduction spreads via slower muscle-to-muscle conduction, which leads to a wide QRS complex and the right ventricle contracts before the left ventricle.

While such dyssynchronous contraction is better than no contraction, this approach leads to a pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in a substantial number of cases. (The incidence reported in many studies varies widely.)

The most disruptive effect of conduction system pacing is that it is a form of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). And that is nifty because, until recently, resynchronizing the ventricles required placing two ventricular leads: one in the right ventricle and the other in the coronary sinus to pace the left ventricle.

Left bundle-branch pacing vs. biventricular pacing

The first of the three HRS studies is the LBBP-RESYNC randomized controlled trial led by Jiangang Zou, MD, PhD, and performed in multiple centers in China. It compared the efficacy of left bundle–branch pacing (LBBP) with that of conventional biventricular pacing in 40 patients with heart failure who were eligible for CRT. The primary endpoint was the change in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) from baseline to 6-month follow-up.

The results favored LBBP. Although both pacing techniques improved LVEF from baseline, the between-group difference in LVEF was greater in the LBBP arm than the biventricular pacing arm by a statistically significant 5.6% (95% confidence interval, 0.3%-10.9%). Secondary endpoints, such as reductions in left ventricular end-systolic volume, N-terminal of the prohormone brain natriuretic peptide, and QRS duration, also favored LBBP.

Conduction system pacing vs. biventricular pacing

A second late-breaking study, from the Geisinger group, led by Pugazhendhi Vijayaraman, MD, was simultaneously published in Heart Rhythm.

This nonrandomized observational study compared nearly 500 patients eligible for CRT treated at two health systems. One group favors conduction system pacing and the other does traditional biventricular pacing, which set up a two-armed comparison.

CSP was accomplished by LBBP (65%) and His-bundle pacing (35%).

The primary endpoint of death or first hospitalization for heart failure occurred in 28.3% of patients in the CSP arm versus 38.4% of the biventricular arm (hazard ratio, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.08-2.09). QRS duration and LVEF also improved from baseline in both groups.

LBB area pacing as a bailout for failed CRT

The Geisinger group also presented and published an international multicenter study that assessed the feasibility of LBBP as a bailout when standard biventricular pacing did not work – because of inadequate coronary sinus anatomy or CRT nonresponse, defined as lack of clinical or echocardiographic improvement.

This series included 212 patients in whom CRT failed and who underwent attempted LBBP pacing. The bailout was successful in 200 patients (91%). The primary endpoint was defined as an increase in LVEF above 5% on echocardiography.

During 12-month follow-up, 61% of patients had an improvement in LVEF above 5% and nearly 30% had a “super-response,” defined as a 20% or greater increase or normalization of LVEF. Similar to the previous studies, LBBP resulted in shorter QRS duration and improved echocardiography parameters.

Am I persuaded?

I was an early adopter of His-bundle pacing. When successful, it delivered both aesthetically pleasing QRS complexes and clinical efficacy. But there were many challenges: it is technically difficult, and capture thresholds are often high at implant and get higher over time, which leads to shorter battery life.

Pacing the left bundle branch mitigates these challenges. Here, the operator approaches from the right side and screws the lead a few millimeters into the septum, so the tip of the lead can capture the left bundle or one of its branches. This allows activation of the heart’s specialized conduction system and thus synchronizes right and left ventricle contraction.

Although there is a learning curve, LBBP is technically easier than His-bundle pacing and ultimately results in far better pacing and sensing parameters. What’s more, the preferred lead for LBBP has a stellar efficacy record – over years.

I have become enthralled by the gorgeous QRS complexes from LBBP. The ability to pace the heart without creating dyssynchrony infuses me with joy. I chose cardiology largely because of the beauty of the ECG.

But as a medical conservative who is cautious about unproven therapies, I have questions. How is LBBP defined? Is left septal pacing good enough, or do you need actual left bundle capture? What about long-term performance of a lead in the septum?

Biventricular pacing has set a high bar because it has been proven effective for reducing hard clinical outcomes in large randomized controlled trials.

The studies at HRS begin to answer these questions. The randomized controlled trial from China supports the notion that effective LBBP (the investigators rigorously defined left bundle capture) leads to favorable effects on cardiac contraction. The two observational studies reported similarly encouraging findings on cardiac function.

The three studies therefore tentatively support the notion that LBBP actually produces favorable cardiac performance.

Whether LBBP leads to better clinical outcomes remains uncertain. The nonrandomized comparison study, which found better hard outcomes in the CSP arm, cannot be used to infer causality. There is too much risk for selection bias.

But the LBBP bailout study does suggest that this strategy is reasonable when coronary sinus leads fail – especially since the alternative is surgical placement of an epicardial lead on the left ventricle.

At minimum, the HRS studies persuade me that LBBP will likely prevent pacing-induced cardiomyopathy. If I or a family member required a pacemaker, I’d surely want the operator to be skilled at placing a left bundle lead.

While I am confident that conduction system pacing will become a transformative advance in cardiac pacing, aesthetically pleasing ECG patterns are not enough. There remains much to learn with this nascent approach.

The barriers to getting more CSP trials

The challenge going forward will be funding new trials. CSP stands to prevent pacing-induced cardiomyopathy and offer less costly alternatives to standard biventricular pacing for CRT. This is great for patients, but it would mean that fewer higher-cost CRT devices will be sold.

Heart rhythm research is largely industry-funded because in most cases better therapies for patients mean more profits for industry. In the case of CSP, there is no such confluence of interests.

Conduction system pacing has come about because of the efforts of a few tireless champions who not only published extensively but were also skilled at using social media to spread the excitement. Trials have been small and often self-funded.

The data presented at HRS provides enough equipoise to support a large outcomes-based randomized controlled trial. Imagine if our CSP champions were able to find public-funding sources for such future trials.

Now that would be super cool.

Dr. Mandrola practices cardiac electrophysiology in Louisville, Ky., and is a writer and podcaster for Medscape. He participates in clinical research and writes often about the state of medical evidence. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Colorado law would lift veil of secrecy on sperm donations

Legislation nearing passage in Colorado would lift a veil of secrecy around sperm donation and grant other protections to people conceived with donated gametes.

The bipartisan bill, which was passed by the state’s house of representatives May 10 after previous approval by the senate, would enable offspring to learn the identity of a sperm or egg donor when they turn 18 and receive a donor’s medical information prior to that. Fertility clinics would be required to update donors’ contact information and medical records every 3 years.

In addition, clinics would have to make “good-faith efforts” to track births to ensure that no more than 25 families conceive babies from a single donor’s sperm. Egg donors could donate up to six times, based on medical risk.

The bill would establish a minimum donor age of 21 years and require dissemination of educational materials to donors and prospective parents about the psychological needs of donor-conceived children.

The provisions would take effect with donations collected on or after Jan. 1, 2025. Violators would be subject to fines of up to $20,000 per day.

Advocates point out that in addition to the benefits of knowing one’s genetic identity, the anonymity of sperm donors has been scuttled by the availability of commercial genetic testing. (Egg donation has tended to be more open.)

Some sperm banks already have adopted systems in which adult offspring can learn the identity of donors if both parties agree. However, a survey by the United States Donor Conceived Council, an advocacy group, found “significant problems” with some of those policies, such as requirements that donor-conceived offspring sign nondisclosure agreements or sperm banks refusing to release information if a donor-conceived person’s parents never registered the child’s birth with the bank.

Some measures in the bill reflect the guidelines of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, although not all companies follow them, according to the council’s survey. For example, no sperm bank adheres to a recommendation that donors be at least 21 years old.

“The industry is shifting very fast, but there are definitely banks that I think need an extra push to protect the rights of the people that they’re producing,” Tiffany Gardner, a spokesperson for the council, told this news organization.

At a senate hearing, fertility care providers voiced concerns that the legislation would impose undue burdens on the industry and discourage men from donating sperm. In response, sponsors made several amendments, including capping a licensing fee for clinics and banks at $500 and increasing the family limit for each donor, which was originally set at 10.

Still, some in the industry said the bill, introduced April 22, was too rushed to receive adequate scrutiny. While everyone agreed that limiting the number of a person’s half siblings is a good thing, for example, the best way to go about it is unclear, they said.

“There wasn’t enough time to really get experts together to provide more formal, thoughtful, evidence-based feedback on what should be on this bill,” said Cassandra Roeca, MD, of Shady Grove Fertility, which has clinics in Denver and Colorado Springs. Dr. Roeca testified on behalf of Colorado Fertility Advocates, a nonprofit that promotes access to fertility care.

Gov. Jared Polis (D) is expected to sign the bill, an aide to one of the co-sponsors, Rep. Kerry Tipper (D-Lakewood), said in an interview.

Colorado is not the only state considering transparency for donor-conceived offspring. A New York bill would require fertility clinics to verify the medical, educational, and criminal histories of donors and allow donor-conceived people access to the information.

The New York measure is championed by the family of Steven Gunner, a 27-year-old man who died in May 2020 of an opioid overdose. The Wall Street Journal reported that Mr. Gunner’s family had been unaware of his biological father’s history of psychiatric problems.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Legislation nearing passage in Colorado would lift a veil of secrecy around sperm donation and grant other protections to people conceived with donated gametes.

The bipartisan bill, which was passed by the state’s house of representatives May 10 after previous approval by the senate, would enable offspring to learn the identity of a sperm or egg donor when they turn 18 and receive a donor’s medical information prior to that. Fertility clinics would be required to update donors’ contact information and medical records every 3 years.

In addition, clinics would have to make “good-faith efforts” to track births to ensure that no more than 25 families conceive babies from a single donor’s sperm. Egg donors could donate up to six times, based on medical risk.

The bill would establish a minimum donor age of 21 years and require dissemination of educational materials to donors and prospective parents about the psychological needs of donor-conceived children.

The provisions would take effect with donations collected on or after Jan. 1, 2025. Violators would be subject to fines of up to $20,000 per day.

Advocates point out that in addition to the benefits of knowing one’s genetic identity, the anonymity of sperm donors has been scuttled by the availability of commercial genetic testing. (Egg donation has tended to be more open.)

Some sperm banks already have adopted systems in which adult offspring can learn the identity of donors if both parties agree. However, a survey by the United States Donor Conceived Council, an advocacy group, found “significant problems” with some of those policies, such as requirements that donor-conceived offspring sign nondisclosure agreements or sperm banks refusing to release information if a donor-conceived person’s parents never registered the child’s birth with the bank.

Some measures in the bill reflect the guidelines of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, although not all companies follow them, according to the council’s survey. For example, no sperm bank adheres to a recommendation that donors be at least 21 years old.

“The industry is shifting very fast, but there are definitely banks that I think need an extra push to protect the rights of the people that they’re producing,” Tiffany Gardner, a spokesperson for the council, told this news organization.

At a senate hearing, fertility care providers voiced concerns that the legislation would impose undue burdens on the industry and discourage men from donating sperm. In response, sponsors made several amendments, including capping a licensing fee for clinics and banks at $500 and increasing the family limit for each donor, which was originally set at 10.

Still, some in the industry said the bill, introduced April 22, was too rushed to receive adequate scrutiny. While everyone agreed that limiting the number of a person’s half siblings is a good thing, for example, the best way to go about it is unclear, they said.

“There wasn’t enough time to really get experts together to provide more formal, thoughtful, evidence-based feedback on what should be on this bill,” said Cassandra Roeca, MD, of Shady Grove Fertility, which has clinics in Denver and Colorado Springs. Dr. Roeca testified on behalf of Colorado Fertility Advocates, a nonprofit that promotes access to fertility care.

Gov. Jared Polis (D) is expected to sign the bill, an aide to one of the co-sponsors, Rep. Kerry Tipper (D-Lakewood), said in an interview.

Colorado is not the only state considering transparency for donor-conceived offspring. A New York bill would require fertility clinics to verify the medical, educational, and criminal histories of donors and allow donor-conceived people access to the information.

The New York measure is championed by the family of Steven Gunner, a 27-year-old man who died in May 2020 of an opioid overdose. The Wall Street Journal reported that Mr. Gunner’s family had been unaware of his biological father’s history of psychiatric problems.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Legislation nearing passage in Colorado would lift a veil of secrecy around sperm donation and grant other protections to people conceived with donated gametes.

The bipartisan bill, which was passed by the state’s house of representatives May 10 after previous approval by the senate, would enable offspring to learn the identity of a sperm or egg donor when they turn 18 and receive a donor’s medical information prior to that. Fertility clinics would be required to update donors’ contact information and medical records every 3 years.

In addition, clinics would have to make “good-faith efforts” to track births to ensure that no more than 25 families conceive babies from a single donor’s sperm. Egg donors could donate up to six times, based on medical risk.

The bill would establish a minimum donor age of 21 years and require dissemination of educational materials to donors and prospective parents about the psychological needs of donor-conceived children.

The provisions would take effect with donations collected on or after Jan. 1, 2025. Violators would be subject to fines of up to $20,000 per day.

Advocates point out that in addition to the benefits of knowing one’s genetic identity, the anonymity of sperm donors has been scuttled by the availability of commercial genetic testing. (Egg donation has tended to be more open.)

Some sperm banks already have adopted systems in which adult offspring can learn the identity of donors if both parties agree. However, a survey by the United States Donor Conceived Council, an advocacy group, found “significant problems” with some of those policies, such as requirements that donor-conceived offspring sign nondisclosure agreements or sperm banks refusing to release information if a donor-conceived person’s parents never registered the child’s birth with the bank.

Some measures in the bill reflect the guidelines of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, although not all companies follow them, according to the council’s survey. For example, no sperm bank adheres to a recommendation that donors be at least 21 years old.

“The industry is shifting very fast, but there are definitely banks that I think need an extra push to protect the rights of the people that they’re producing,” Tiffany Gardner, a spokesperson for the council, told this news organization.

At a senate hearing, fertility care providers voiced concerns that the legislation would impose undue burdens on the industry and discourage men from donating sperm. In response, sponsors made several amendments, including capping a licensing fee for clinics and banks at $500 and increasing the family limit for each donor, which was originally set at 10.

Still, some in the industry said the bill, introduced April 22, was too rushed to receive adequate scrutiny. While everyone agreed that limiting the number of a person’s half siblings is a good thing, for example, the best way to go about it is unclear, they said.

“There wasn’t enough time to really get experts together to provide more formal, thoughtful, evidence-based feedback on what should be on this bill,” said Cassandra Roeca, MD, of Shady Grove Fertility, which has clinics in Denver and Colorado Springs. Dr. Roeca testified on behalf of Colorado Fertility Advocates, a nonprofit that promotes access to fertility care.

Gov. Jared Polis (D) is expected to sign the bill, an aide to one of the co-sponsors, Rep. Kerry Tipper (D-Lakewood), said in an interview.

Colorado is not the only state considering transparency for donor-conceived offspring. A New York bill would require fertility clinics to verify the medical, educational, and criminal histories of donors and allow donor-conceived people access to the information.

The New York measure is championed by the family of Steven Gunner, a 27-year-old man who died in May 2020 of an opioid overdose. The Wall Street Journal reported that Mr. Gunner’s family had been unaware of his biological father’s history of psychiatric problems.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Senate GOP Puts Up Roadblocks to Bipartisan House Bill for Veterans’ Burn Pit Care

Thousands of military veterans who are sick after being exposed to toxic smoke and dust while on duty are facing a Senate roadblock to ambitious legislation designed to provide them care.

The Senate could start work as soon as this week on a bipartisan bill, called the Honoring Our PACT Act, that passed the House of Representatives in March. It would make it much easier for veterans to get health care and benefits from the Veterans Health Administration if they get sick because of the air they breathed around massive, open-air incineration pits. The military used those pits in war zones around the globe — sometimes the size of football fields — to burn anything from human and medical waste to plastics and munitions, setting it alight with jet fuel.

As it stands now, more than three-quarters of all veterans who submit claims for cancer, breathing disorders, and other illnesses that they believe are caused by inhaling poisonous burn pit smoke have their claims denied, according to estimates from the Department of Veterans Affairs and service organizations.

The reason so few are approved is that the military and VA require injured war fighters to prove an illness is directly connected to their service — something that is extremely difficult when it comes to toxic exposures. The House’s PACT Act would make that easier by declaring that any of the 3.5 million veterans who served in the global war on terror — including operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Persian Gulf — would be presumed eligible for benefits if they come down with any of 23 ailments linked to the burn pits.

Although 34 Republicans voted with Democrats to pass the bill in the House, only one Republican, Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida, has signaled support for the measure. At least 10 GOP members would have to join all Democrats to avoid the threat of a filibuster in the Senate and allow the bill to advance to President Joe Biden’s desk. Biden called on Congress to pass such legislation in his State of the Union address, citing the death of his son Beau Biden, who served in Iraq in 2008 and died in 2015 of glioblastoma, a brain cancer included on the bill’s list of qualifying conditions.

Senate Republicans are raising concerns about the measure, however, suggesting it won’t be paid for, that it is too big, too ambitious, and could end up promising more than the government can deliver.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates the bill would cost more than $300 billion over 10 years, and the VA already has struggled for years to meet surging demand from troops serving deployments since the 2001 terror attacks on America, with a backlog of delayed claims running into the hundreds of thousands. Besides addressing burn pits, the bill would expand benefits for veterans who served at certain nuclear sites, and cover more conditions related to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam, among several other issues.

While the bill phases in coverage for new groups of beneficiaries over 10 years, some Republicans involved in writing legislation about burn pits fear it is all too much.

Sen. Mike Rounds (R-S.D.), a member of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, summed up the concern as stemming from promising lots of assistance “that might look really good,” but the bottom line is that those “who really need the care would never get into a VA facility.”

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), another member of the panel, agreed. “What we’re concerned with is that you’ve got a backlog of 222,000 cases now, and if you implement, by legislative fiat, the 23 presumptions, we’re gonna go to a million and a half to two and a half million backlog,” he said. Tillis has advanced his own burn pits bill that would leave it to the military and VA to determine which illnesses automatically were presumed to be service-connected. That tally is likely to cover fewer people. “So the question we have is, while making a new promise, are we going to be breaking a promise for all those veterans that need care today?”

Republicans have insisted they want to do something to help veterans who are increasingly getting sick with illnesses that appear related to toxic exposure. About 300,000 veterans have signed up with the VA’s burn pits registry.

Sen. Jerry Moran from Kansas, the top Republican on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, held a press conference in February with Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), the committee chairman, advocating a more gradual process to expand access to benefits and define the illnesses that would qualify.

The event was designed to show what would easily gain bipartisan support in the Senate while the House was still working on its bill.

Veterans’ service organizations, which try to avoid taking partisan positions, have praised such efforts. But they’ve also made clear they like the House bill. More than 40 of the groups endorsed the PACT Act before it passed the lower chamber.

Aleks Morosky, a governmental affairs specialist for the Wounded Warrior Project, plans to meet with senators this month in hope of advancing the PACT Act.

“This is an urgent issue. I mean, people are dying,” Morosky said.

He added that he believes some minor changes and input from the VA would eliminate the sorts of problems senators are raising.

“This bill was meticulously put together, and these are the provisions that veterans need,” Morosky said. “The VA is telling us that they can implement it the way they’ve implemented large numbers of people coming into the system in the past.”

He pointed to the recent expansion of Agent Orange benefits to Navy veterans and to VA Secretary Denis McDonough’s testimony to the Senate Veterans’ Affairs committee in March. McDonough largely supported the legislation but said the VA would need new leasing authority to ensure it had adequate facilities, as well as more say over adding illnesses to be covered.

Senate Republicans are not so sure about the VA’s ability to absorb such a large group of new patients. Tillis and Rounds suggested one solution would be to greatly expand the access to care veterans can seek outside the VA. They pointed to the Mission Act, a law passed in 2018 that was meant to grant veterans access to private health care. Some critics say it has not lived up to its promise. It’s also been expensive, requiring emergency appropriations from Congress.

“You better think about having community care — because there’s no way you’re going to be able to ramp up the medical infrastructure to provide that purely through the VA,” Tillis said.

Tester said in a statement that the committee was working on McDonough’s requests — and could have a modified bill for a vote before Memorial Day.

“In addition to delivering historic reform for all generations of toxic-exposed veterans, I’m working to ensure this legislation provides VA with additional resources and authorities to hire more staff, establish new facilities, and make critical investments to better ensure it can meet the current and future needs of our nation’s veterans,” Tester said.

Whether or not those changes satisfy enough Republicans remains to be seen.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), who chairs the Armed Services subcommittee on personnel and earlier wrote a burn pits bill, said neither cost nor fears about problems on implementation should get in the way of passing the bill. Her proposal was incorporated into the House’s PACT Act.

“To deny service because of a lack of resources or a lack of personnel is an outrageous statement,” Gillibrand said. “We promised these men and women when they went to war that when they came back, we would protect them. And that is our solemn obligation. And if it needs more resources, we will get them more resources.”

She predicted Republicans would come along to help pass a bill.

“I’m optimistic, actually. I think we just need a little more time to talk to more Republicans to get everybody on board,” she said.

Thousands of military veterans who are sick after being exposed to toxic smoke and dust while on duty are facing a Senate roadblock to ambitious legislation designed to provide them care.

The Senate could start work as soon as this week on a bipartisan bill, called the Honoring Our PACT Act, that passed the House of Representatives in March. It would make it much easier for veterans to get health care and benefits from the Veterans Health Administration if they get sick because of the air they breathed around massive, open-air incineration pits. The military used those pits in war zones around the globe — sometimes the size of football fields — to burn anything from human and medical waste to plastics and munitions, setting it alight with jet fuel.

As it stands now, more than three-quarters of all veterans who submit claims for cancer, breathing disorders, and other illnesses that they believe are caused by inhaling poisonous burn pit smoke have their claims denied, according to estimates from the Department of Veterans Affairs and service organizations.

The reason so few are approved is that the military and VA require injured war fighters to prove an illness is directly connected to their service — something that is extremely difficult when it comes to toxic exposures. The House’s PACT Act would make that easier by declaring that any of the 3.5 million veterans who served in the global war on terror — including operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Persian Gulf — would be presumed eligible for benefits if they come down with any of 23 ailments linked to the burn pits.

Although 34 Republicans voted with Democrats to pass the bill in the House, only one Republican, Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida, has signaled support for the measure. At least 10 GOP members would have to join all Democrats to avoid the threat of a filibuster in the Senate and allow the bill to advance to President Joe Biden’s desk. Biden called on Congress to pass such legislation in his State of the Union address, citing the death of his son Beau Biden, who served in Iraq in 2008 and died in 2015 of glioblastoma, a brain cancer included on the bill’s list of qualifying conditions.

Senate Republicans are raising concerns about the measure, however, suggesting it won’t be paid for, that it is too big, too ambitious, and could end up promising more than the government can deliver.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates the bill would cost more than $300 billion over 10 years, and the VA already has struggled for years to meet surging demand from troops serving deployments since the 2001 terror attacks on America, with a backlog of delayed claims running into the hundreds of thousands. Besides addressing burn pits, the bill would expand benefits for veterans who served at certain nuclear sites, and cover more conditions related to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam, among several other issues.

While the bill phases in coverage for new groups of beneficiaries over 10 years, some Republicans involved in writing legislation about burn pits fear it is all too much.

Sen. Mike Rounds (R-S.D.), a member of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, summed up the concern as stemming from promising lots of assistance “that might look really good,” but the bottom line is that those “who really need the care would never get into a VA facility.”

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), another member of the panel, agreed. “What we’re concerned with is that you’ve got a backlog of 222,000 cases now, and if you implement, by legislative fiat, the 23 presumptions, we’re gonna go to a million and a half to two and a half million backlog,” he said. Tillis has advanced his own burn pits bill that would leave it to the military and VA to determine which illnesses automatically were presumed to be service-connected. That tally is likely to cover fewer people. “So the question we have is, while making a new promise, are we going to be breaking a promise for all those veterans that need care today?”

Republicans have insisted they want to do something to help veterans who are increasingly getting sick with illnesses that appear related to toxic exposure. About 300,000 veterans have signed up with the VA’s burn pits registry.

Sen. Jerry Moran from Kansas, the top Republican on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, held a press conference in February with Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), the committee chairman, advocating a more gradual process to expand access to benefits and define the illnesses that would qualify.

The event was designed to show what would easily gain bipartisan support in the Senate while the House was still working on its bill.

Veterans’ service organizations, which try to avoid taking partisan positions, have praised such efforts. But they’ve also made clear they like the House bill. More than 40 of the groups endorsed the PACT Act before it passed the lower chamber.

Aleks Morosky, a governmental affairs specialist for the Wounded Warrior Project, plans to meet with senators this month in hope of advancing the PACT Act.

“This is an urgent issue. I mean, people are dying,” Morosky said.

He added that he believes some minor changes and input from the VA would eliminate the sorts of problems senators are raising.

“This bill was meticulously put together, and these are the provisions that veterans need,” Morosky said. “The VA is telling us that they can implement it the way they’ve implemented large numbers of people coming into the system in the past.”

He pointed to the recent expansion of Agent Orange benefits to Navy veterans and to VA Secretary Denis McDonough’s testimony to the Senate Veterans’ Affairs committee in March. McDonough largely supported the legislation but said the VA would need new leasing authority to ensure it had adequate facilities, as well as more say over adding illnesses to be covered.

Senate Republicans are not so sure about the VA’s ability to absorb such a large group of new patients. Tillis and Rounds suggested one solution would be to greatly expand the access to care veterans can seek outside the VA. They pointed to the Mission Act, a law passed in 2018 that was meant to grant veterans access to private health care. Some critics say it has not lived up to its promise. It’s also been expensive, requiring emergency appropriations from Congress.

“You better think about having community care — because there’s no way you’re going to be able to ramp up the medical infrastructure to provide that purely through the VA,” Tillis said.

Tester said in a statement that the committee was working on McDonough’s requests — and could have a modified bill for a vote before Memorial Day.

“In addition to delivering historic reform for all generations of toxic-exposed veterans, I’m working to ensure this legislation provides VA with additional resources and authorities to hire more staff, establish new facilities, and make critical investments to better ensure it can meet the current and future needs of our nation’s veterans,” Tester said.

Whether or not those changes satisfy enough Republicans remains to be seen.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), who chairs the Armed Services subcommittee on personnel and earlier wrote a burn pits bill, said neither cost nor fears about problems on implementation should get in the way of passing the bill. Her proposal was incorporated into the House’s PACT Act.

“To deny service because of a lack of resources or a lack of personnel is an outrageous statement,” Gillibrand said. “We promised these men and women when they went to war that when they came back, we would protect them. And that is our solemn obligation. And if it needs more resources, we will get them more resources.”

She predicted Republicans would come along to help pass a bill.

“I’m optimistic, actually. I think we just need a little more time to talk to more Republicans to get everybody on board,” she said.

Thousands of military veterans who are sick after being exposed to toxic smoke and dust while on duty are facing a Senate roadblock to ambitious legislation designed to provide them care.

The Senate could start work as soon as this week on a bipartisan bill, called the Honoring Our PACT Act, that passed the House of Representatives in March. It would make it much easier for veterans to get health care and benefits from the Veterans Health Administration if they get sick because of the air they breathed around massive, open-air incineration pits. The military used those pits in war zones around the globe — sometimes the size of football fields — to burn anything from human and medical waste to plastics and munitions, setting it alight with jet fuel.

As it stands now, more than three-quarters of all veterans who submit claims for cancer, breathing disorders, and other illnesses that they believe are caused by inhaling poisonous burn pit smoke have their claims denied, according to estimates from the Department of Veterans Affairs and service organizations.

The reason so few are approved is that the military and VA require injured war fighters to prove an illness is directly connected to their service — something that is extremely difficult when it comes to toxic exposures. The House’s PACT Act would make that easier by declaring that any of the 3.5 million veterans who served in the global war on terror — including operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and the Persian Gulf — would be presumed eligible for benefits if they come down with any of 23 ailments linked to the burn pits.

Although 34 Republicans voted with Democrats to pass the bill in the House, only one Republican, Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida, has signaled support for the measure. At least 10 GOP members would have to join all Democrats to avoid the threat of a filibuster in the Senate and allow the bill to advance to President Joe Biden’s desk. Biden called on Congress to pass such legislation in his State of the Union address, citing the death of his son Beau Biden, who served in Iraq in 2008 and died in 2015 of glioblastoma, a brain cancer included on the bill’s list of qualifying conditions.

Senate Republicans are raising concerns about the measure, however, suggesting it won’t be paid for, that it is too big, too ambitious, and could end up promising more than the government can deliver.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates the bill would cost more than $300 billion over 10 years, and the VA already has struggled for years to meet surging demand from troops serving deployments since the 2001 terror attacks on America, with a backlog of delayed claims running into the hundreds of thousands. Besides addressing burn pits, the bill would expand benefits for veterans who served at certain nuclear sites, and cover more conditions related to Agent Orange exposure in Vietnam, among several other issues.

While the bill phases in coverage for new groups of beneficiaries over 10 years, some Republicans involved in writing legislation about burn pits fear it is all too much.

Sen. Mike Rounds (R-S.D.), a member of the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, summed up the concern as stemming from promising lots of assistance “that might look really good,” but the bottom line is that those “who really need the care would never get into a VA facility.”

Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), another member of the panel, agreed. “What we’re concerned with is that you’ve got a backlog of 222,000 cases now, and if you implement, by legislative fiat, the 23 presumptions, we’re gonna go to a million and a half to two and a half million backlog,” he said. Tillis has advanced his own burn pits bill that would leave it to the military and VA to determine which illnesses automatically were presumed to be service-connected. That tally is likely to cover fewer people. “So the question we have is, while making a new promise, are we going to be breaking a promise for all those veterans that need care today?”

Republicans have insisted they want to do something to help veterans who are increasingly getting sick with illnesses that appear related to toxic exposure. About 300,000 veterans have signed up with the VA’s burn pits registry.

Sen. Jerry Moran from Kansas, the top Republican on the Veterans’ Affairs Committee, held a press conference in February with Sen. Jon Tester (D-Mont.), the committee chairman, advocating a more gradual process to expand access to benefits and define the illnesses that would qualify.

The event was designed to show what would easily gain bipartisan support in the Senate while the House was still working on its bill.

Veterans’ service organizations, which try to avoid taking partisan positions, have praised such efforts. But they’ve also made clear they like the House bill. More than 40 of the groups endorsed the PACT Act before it passed the lower chamber.

Aleks Morosky, a governmental affairs specialist for the Wounded Warrior Project, plans to meet with senators this month in hope of advancing the PACT Act.

“This is an urgent issue. I mean, people are dying,” Morosky said.

He added that he believes some minor changes and input from the VA would eliminate the sorts of problems senators are raising.

“This bill was meticulously put together, and these are the provisions that veterans need,” Morosky said. “The VA is telling us that they can implement it the way they’ve implemented large numbers of people coming into the system in the past.”

He pointed to the recent expansion of Agent Orange benefits to Navy veterans and to VA Secretary Denis McDonough’s testimony to the Senate Veterans’ Affairs committee in March. McDonough largely supported the legislation but said the VA would need new leasing authority to ensure it had adequate facilities, as well as more say over adding illnesses to be covered.

Senate Republicans are not so sure about the VA’s ability to absorb such a large group of new patients. Tillis and Rounds suggested one solution would be to greatly expand the access to care veterans can seek outside the VA. They pointed to the Mission Act, a law passed in 2018 that was meant to grant veterans access to private health care. Some critics say it has not lived up to its promise. It’s also been expensive, requiring emergency appropriations from Congress.

“You better think about having community care — because there’s no way you’re going to be able to ramp up the medical infrastructure to provide that purely through the VA,” Tillis said.

Tester said in a statement that the committee was working on McDonough’s requests — and could have a modified bill for a vote before Memorial Day.

“In addition to delivering historic reform for all generations of toxic-exposed veterans, I’m working to ensure this legislation provides VA with additional resources and authorities to hire more staff, establish new facilities, and make critical investments to better ensure it can meet the current and future needs of our nation’s veterans,” Tester said.

Whether or not those changes satisfy enough Republicans remains to be seen.

Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), who chairs the Armed Services subcommittee on personnel and earlier wrote a burn pits bill, said neither cost nor fears about problems on implementation should get in the way of passing the bill. Her proposal was incorporated into the House’s PACT Act.

“To deny service because of a lack of resources or a lack of personnel is an outrageous statement,” Gillibrand said. “We promised these men and women when they went to war that when they came back, we would protect them. And that is our solemn obligation. And if it needs more resources, we will get them more resources.”

She predicted Republicans would come along to help pass a bill.

“I’m optimistic, actually. I think we just need a little more time to talk to more Republicans to get everybody on board,” she said.

Does noninvasive brain stimulation augment CBT for depression?

Results of a multicenter, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trials showed adjunctive transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) was not superior to sham-tDCS plus CBT or CBT alone.

“Combining these interventions does not lead to added value. This is an example where negative findings guide the way of future studies. What we learned is that we might change things in a few dimensions,” study investigator Malek Bajbouj, MD, Charité University Hospital, Berlin, told this news organization.

The study was published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

Urgent need for better treatment

MDD affects 10% of the global population. However, up to 30% of patients have an inadequate response to standard treatment of CBT, pharmacotherapy, or a combination of the two, highlighting the need to develop more effective therapeutic strategies, the investigators note.

A noninvasive approach, tDCS, in healthy populations, has been shown to enhance cognitive function in brain regions that are also relevant for CBT. Specifically, the investigators point out that tDCS can “positively modulate neuronal activity in prefrontal structures central for affective and cognitive processes,” including emotion regulation, cognitive control working memory, and learning.

Based on this early data, the investigators conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine whether tDCS combined with CBT might have clinically relevant synergistic effects.

The multicenter study included adults aged 20-65 years with a single or recurrent depressive episode who were either not receiving medication or receiving a stable regimen of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or mirtazapine (Remeron).

A total of 148 participants (89 women, 59 men) with a mean age of 41 years were randomly assigned to receive CBT alone (n = 53), CBT+ tDCS (n = 48) or CBT + sham tDCS (n = 47).