User login

Patients asking about APOE gene test results? Here’s what to tell them

Advances in Alzheimer disease (AD) genes and biomarkers now allow older adults to undergo testing and learn about their risk for AD.1 Current routes for doing so include testing in cardiology, screening for enrollment in secondary prevention trials (which use these tests to determine trial eligibility),2 and direct-to-consumer (DTC) services that provide these results as part of large panels.3 Patients may also obtain apolipoprotein (APOE) genotype information as part of an assessment of the risks and benefits of treatment with aducanumab (Aduhelm) or other anti-amyloid therapies that have been developed to stop or slow the progression of AD pathologies.

Expanded access to testing, in combination with limited guidance from DTC companies, suggests more older adults may consult their primary care physicians about this testing. In this narrative review, we use a vignette-driven approach to summarize the current scientific knowledge of the topic and to offer guidance on provider-patient discussions and follow-up.

First, a look at APOE genotyping

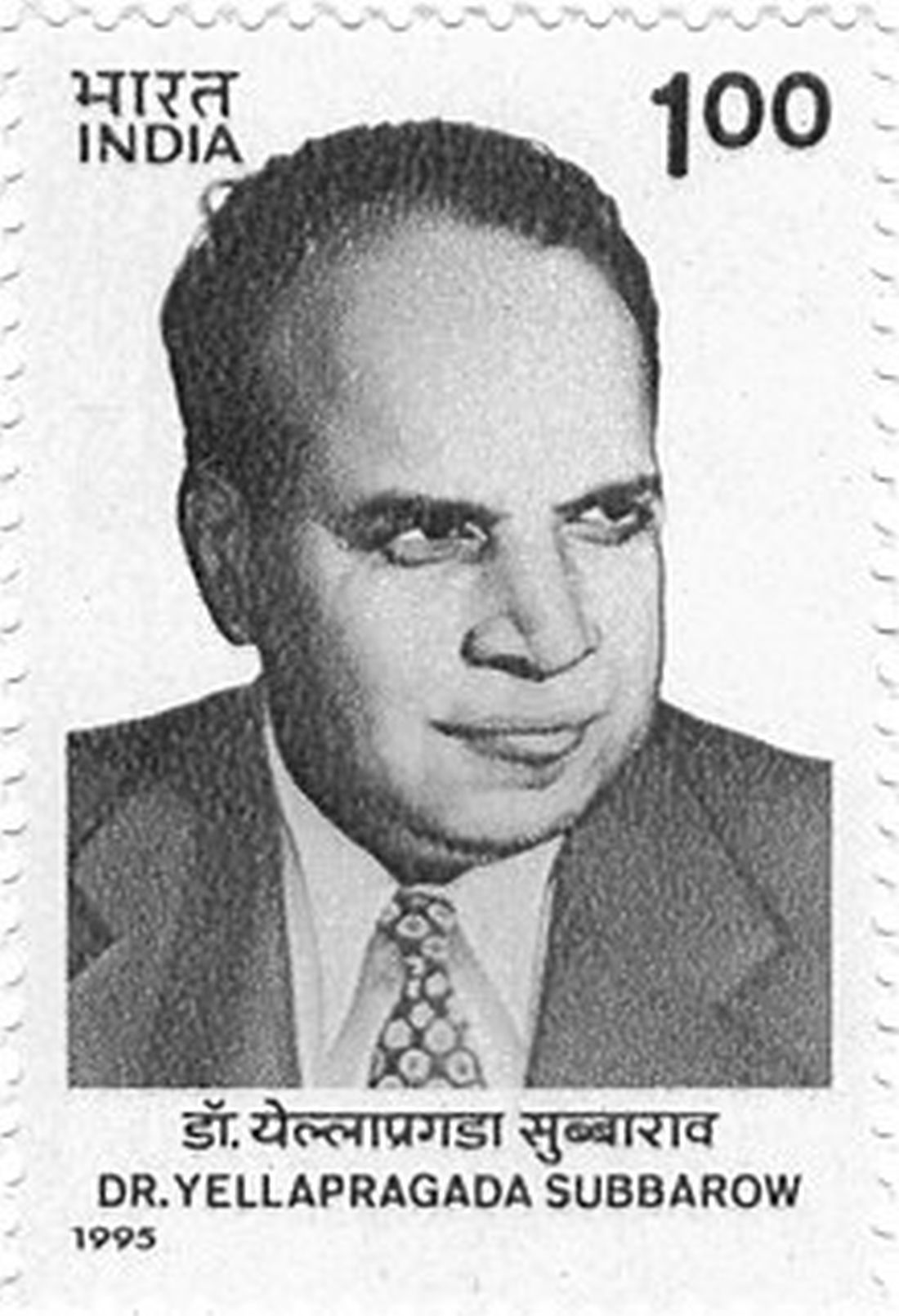

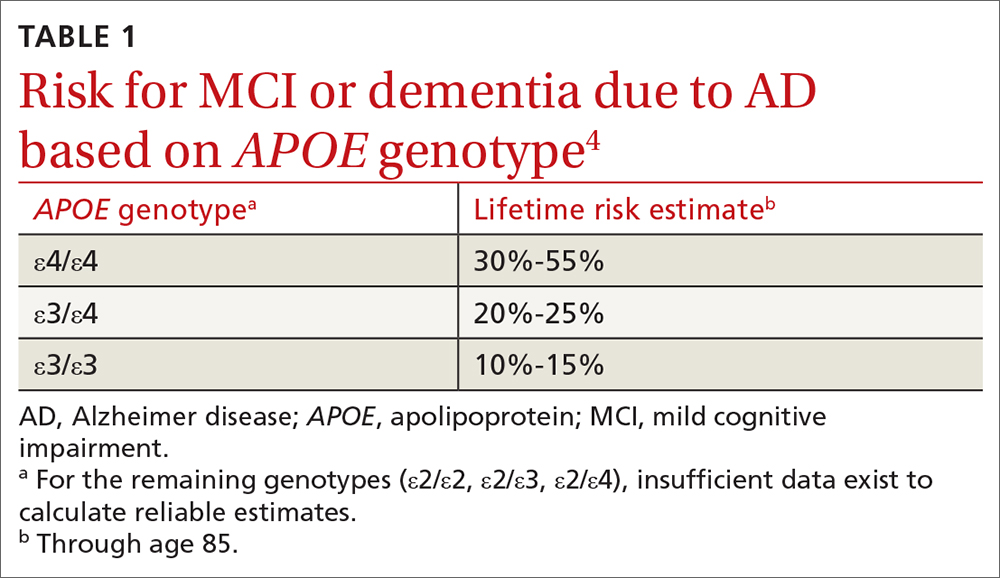

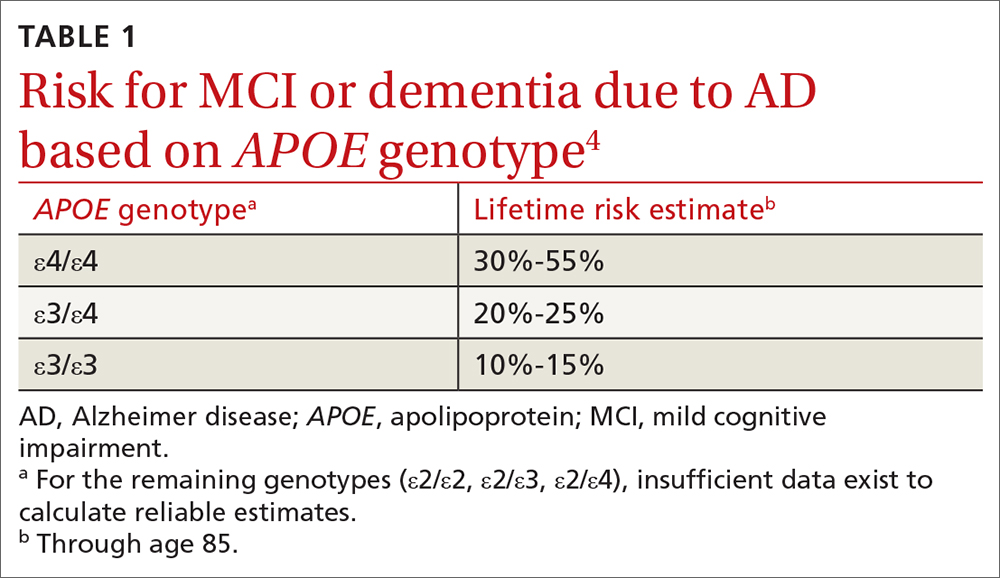

In cognitively unimpaired older adults, the APOE gene is a known risk factor for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD.3 A person has 2 alleles of the APOE gene, which has 3 variants: ε2, ε3, and ε4. The combination of alleles conveys varying levels of risk for developing clinical symptoms (TABLE 14), with ε4 increasing risk and ε2 decreasing risk compared to the more common ε3; thus the ε4/ε4 genotype conveys the most risk and the ε2/ε2 the least.

The APOE gene differs from other genes that have been identified in early-onset familial AD. These other genes, which include APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2, are deterministic genes that are fully penetrant. The APOE gene is not deterministic, meaning there is no combination of APOE alleles that are necessary or sufficient to cause late-onset AD dementia.

In clinical trials of amyloid-modifying therapies, the APOE gene has been shown to convey a risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).5 That is, in addition to conveying a risk for AD, the gene also conveys a risk for adverse effects of emerging treatments that can result in serious injury or death. This includes the drug aducanumab that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).6 In this review, we focus primarily on common clinical scenarios related to APOE. However, in light of the recent controversy over aducanumab and whether the drug should be offered to patients,7-9 we also describe how a patient’s APOE genotype may factor into drug candidacy decisions.

Testing, in clinic and “at home.” To date, practice guidelines have consistently recommended against APOE genetic testing in routine clinical practice. This is primarily due to low clinical prognostic utility and the lack of actionable results. Furthermore, no lifestyle or pharmaceutical interventions based on APOE genotype currently exist (although trials are underway10).

In 2017, the FDA approved marketing of DTC testing for the APOE gene.11 While DTC companies tend to issue standardized test result reports, the content and quality can vary widely. In fact, some provide risk estimates that are too high and too definitive and may not reflect the most recent science.12

Continue to: 7 clinical scenarios and how to approach them

7 clinical scenarios and how to approach them

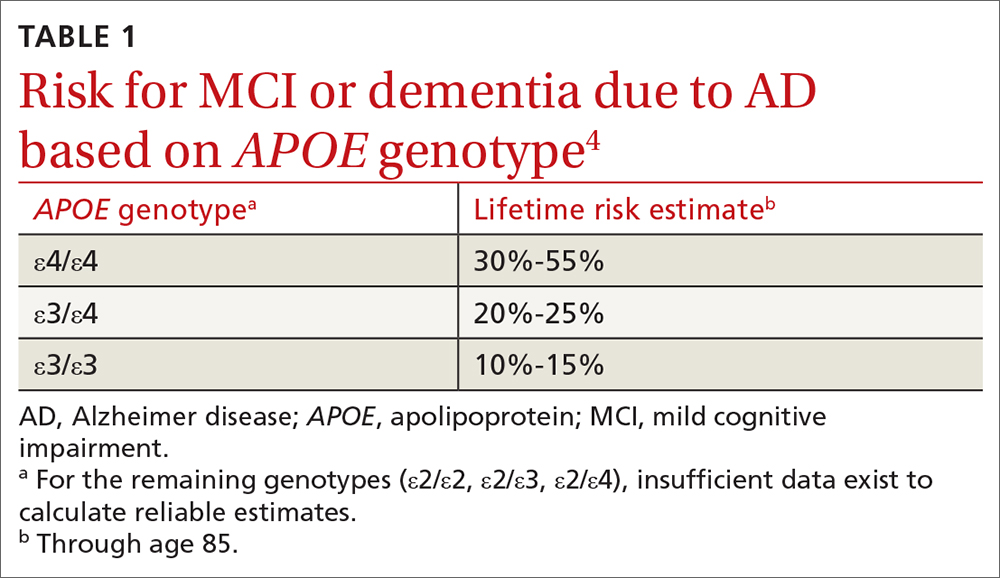

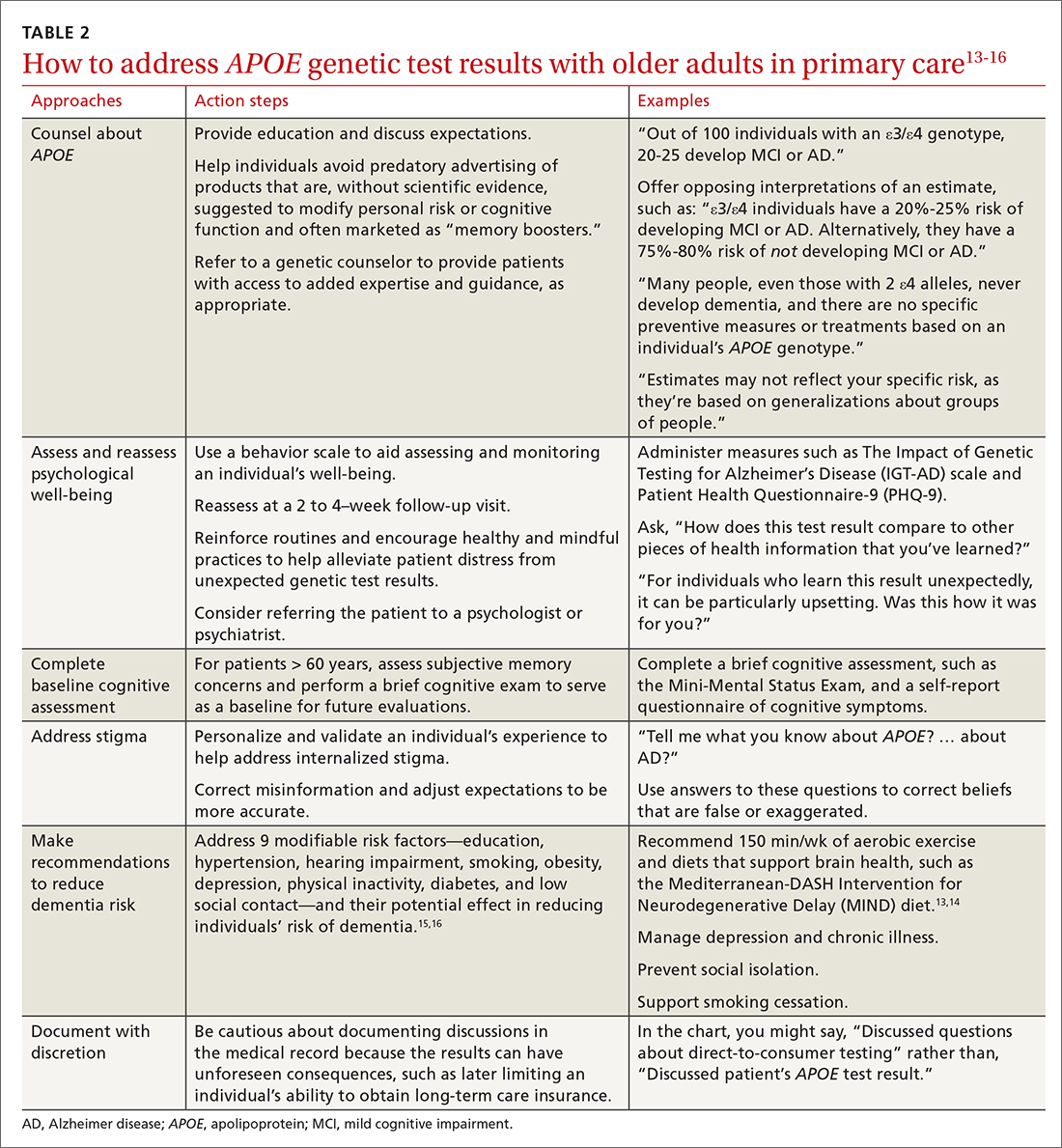

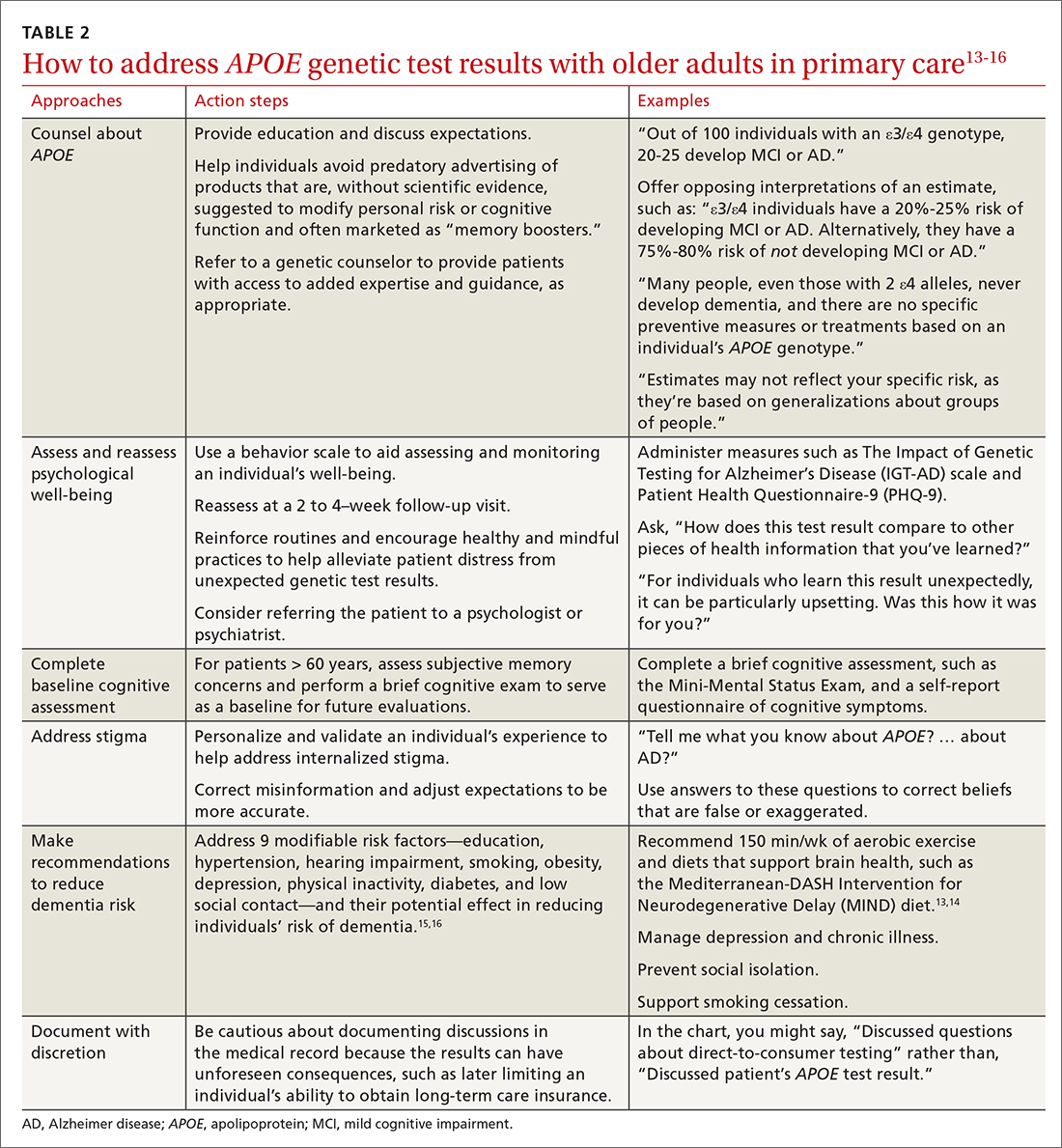

Six of the following vignettes describe common clinical scenarios in which patients seek medical advice regarding APOE test results. The seventh vignette describes a patient whose APOE genotype may play a role in possible disease-modifying treatments down the road. Each vignette is designed to guide your approach to patient discussions and follow-up. Recommendations and considerations are also summarized in TABLE 213-16.

Vignette 1

Janet W, age 65, comes to the clinic for a new patient visit. She has no concerns about her memory but recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about her genetic health risks. Her results showed an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. She is now concerned about developing AD. Her mother was diagnosed with AD in her 70s.

Several important pieces of information can be conveyed by the primary care physician. First, patients such as Ms. W should be told that the APOE gene is not deterministic; many people, even those with 2 ε4 alleles, never develop dementia. Second, no specific preventive measures or treatments exist based on an individual’s APOE genotype (see Vignette 5 for additional discussion).

In this scenario, patients may ask for numeric quantification of their risk for dementia (see TABLE 14 for estimates). When conveying probabilistic risk, consider using simple percentages or pictographs (eg, out of 100 individuals with an ε4/ε4 genotype, 30 to 55 develop MCI or AD). Additionally, because people tend to exhibit confirmatory bias in thinking about probabilistic risk, providing opposing interpretations of an estimate may help them to consider alternative possibilities.17 For example

There are important caveats to the interpretation of APOE risk estimates. Because APOE risk estimates are probabilistic and averaged across a broader spectrum of people in large population cohorts,4 estimates may not accurately reflect a given individual’s risk. The ranges reflect the uncertainty in the estimates. The uncertainty arises from relatively small samples, the rareness of some genotypes (notably ε4/ε4) even in large samples, and variations in methods and sampling that can lead to differences in estimates beyond statistical variation.

Vignette 2

Eric J, age 85, presents for a new patient visit accompanied by his daughter. He lives independently, volunteers at a senior center several times a week, and exercises regularly, and neither he nor his daughter has any concerns about his memory. As a gift, he recently underwent DTC genetic testing and unexpectedly learned his APOE result, which is ε4/ε4. He wants to know about his chances of developing AD.

Risk conveyed by APOE genotype can be modified by a patient’s age. At age 85, Mr. J is healthy, highly functional, and cognitively unimpaired. Given his age, Mr. J has likely “outlived” much of the risk for dementia attributable to the ε4/ε4 genotype. His risk for dementia remains high, but this risk is likely driven more by age than by his APOE genotype. Data for individuals older than age 80 are limited, and thus risk estimates lack precision. Given Mr. J’s good health and functional status, his physician may want to perform a brief cognitive screening test to serve as a baseline for future evaluations.

Continue to: Vignette 3

Vignette 3

Audrey S is a 60-year-old African American woman who comes to the clinic for her annual visit. Because her father had AD, she recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about her APOE genotype and risk for AD. Her results are ε3/ε4. She is wondering what this may mean for her future.

Lack of diversity in research cohorts often limits the generalizability of estimates. For example, both the frequency and impact of APOE ε4 differ across racial groups.18 But most of the data on APOE lifetime risk estimates are from largely White patient samples. While APOE ε4 seems to confer increased risk for AD across sociocultural groups, these effects may be attenuated in African American and Hispanic populations.19,20 If Ms. S is interested in numeric risk estimates, the physician can provide the estimate for ε3/ε4 (20%-25% lifetime risk), with the important caveat that this estimate may not be reflective of her individual risk.

It may be prudent to determine whether Ms. S, at age 60, has subjective memory concerns and if she does, to perform a brief cognitive exam to serve as a baseline for future evaluations. Additionally, while the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA, 2008) prohibits health insurers and employers from discriminating based on genetic testing results, no legal provisions exist regarding long-term care, disability, or life insurance. Documented conversations about APOE test results in the medical record may become part of patients’ applications for these insurance products, and physicians should be cautious before documenting such discussions in the medical record.

Vignette 4

Tina L, age 60, comes to the clinic for a routine wellness visit. She recently developed an interest in genealogy and purchased a DNA testing kit to learn more about her family tree. As part of this testing, she unexpectedly learned that she has an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. She describes feeling distraught and anxious about what the result means for her future.

Ms. L’s reaction to receiving unexpected genetic results highlights a concern of DTC APOE testing. Her experience is quite different from individuals undergoing medically recommended genetic testing or those who are participating in research studies. They receive comprehensive pre-test counseling by licensed genetic counselors. The counseling includes psychological assessment, education, and discussion of expectations.2

In Ms. L’s case, it may be helpful to explain the limits of APOE lifetime risk estimates (see Vignettes 1-3). But it’s also important to address her concerns. There are behavior scales that can aid the assessment and monitoring of an individual’s well-being. The Impact of Genetic Testing for Alzheimer’s Disease (IGT-AD) scale is a tool that assesses psychological impact. It can help physicians to identify, monitor, and address concerns.21 Other useful tools include the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for depression, and a suicide or self-harm assessment.2,22,23 Finally, a follow-up visit at 2 to 4 weeks may be useful to reassess psychological well-being.

Vignette 4 (cont’d)

Ms. L returns to the clinic 2 weeks later, reporting continued anxiety about her APOE test result and feelings of hopelessness and despair.

Continue to: Some patients struggle...

Some patients struggle with knowing their APOE test result. Test result–related distress is often a combination of depression (as with Ms. L), anger, confusion, and grief.24 Cognitions often include worries about uncertainty, stereotyped threat, and internalized stigma.25,26 These issues can spill over to patient concerns about sharing an APOE test result with others.27

Intolerance of uncertainty is a transdiagnostic risk factor that can influence psychological suffering.28 Brief cognitive behavioral interventions that reinforce routines and encourage healthy and mindful practices may help alleviate patient distress from unexpected genetic test results.29 Interventions that personalize and validate an individual’s experience can help address internalized stigma.30 Referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist could be warranted. Additionally, referral to a genetic counselor may help provide patients with access to added expertise and guidance; useful web-based resources for identifying an appropriate referral include https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/consult/findingprofessional/ and https://findageneticcounselor.nsgc.org/.

Vignette 5

Bob K, age 65, comes to the clinic for his annual exam. He is a current smoker and says he’s hoping to be more physically active now that he is retired. He says that his mother and grandmother both had AD. He recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn more about his risk for AD. His learned his APOE genotype is ε3/ε4 and is wondering what he can do to decrease his chances of developing AD.

Mr. K likely would have benefited from pre-test counseling regarding the lack of current therapies to modify one’s genetic risk for AD. A pre-test counseling session often includes education about APOE testing and a brief evaluation to assess psychological readiness to undergo testing. Posttest educational information may help Mr. K avoid predatory advertising of products claiming—without scientific evidence—to modify risk for cognitive decline or to improve cognitive function.

There are several important pieces of information that should be communicated to Mr. K. Emerging evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that healthy lifestyle modifications may benefit cognition in individuals with APOE ε4 alleles.31 It would be prudent to address proper blood pressure control32 and counsel Mr. K on how he may be able to avoid diabetes through exercise and weight maintenance. Lifestyle recommendations for Mr. K could include: smoking cessation, regular aerobic exercise (eg, 150 min/wk), and a brain-healthy diet (eg, the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay [MIND] diet).13,14 Moreover, dementia prevention also includes appropriately managing depression and chronic illnesses and preventing social isolation and hearing loss.15,16 This information should be thoughtfully conveyed, as these interventions can improve overall (especially cardiovascular) health, as well as mitigating one’s personal risk for AD.

Vignette 6

Juan L, age 45, comes in for his annual physical exam. He has a strong family history of heart disease. His cardiologist recently ordered lipid disorder genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia. This panel included APOE testing and showed Mr. L’s genotype is ε2/ε4. He read that the APOE gene can be associated with an increased AD risk and asks for information about his genotype.

Mr. L received genetic testing results that were ordered by a physician for another health purpose. Current recommendations for genetic testing in cardiology advise pre-test genetic counseling.33 But this counseling may not include discussion of the relationship of APOE and risk for MCI or AD. This additional information may be unexpected for Mr. L. Moreover, its significance in the context of his present concerns about cardiovascular disease may influence his reaction.

Continue to: The ε2/ε4 genotype...

The ε2/ε4 genotype is rare. One study showed that in healthy adults, the frequency was 7 in 210 (0.02 [0.01-0.04]).34 Given the rarity of the ε2/ε4 genotype, data about it are sparse. However, since the ε4 allele increases risk but the ε2 allele decreases risk, it is likely that any increase in risk is more modest than with ε3/ε4. In addition, it would help Mr. L to know that AD occurs infrequently before age 60.35 Given his relatively young age, he is unlikely to develop AD any time in the near future. In addition, particularly if he starts early, he might be able to mitigate any increased risk through some of the advice provided to Mr. K in Vignette 5.

Vignette 7

Joe J, age 65, comes to the clinic for a new patient visit. He has no concerns about his memory but has a family history of dementia and recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about his genetic health risks. His results showed an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. He is concerned about developing AD. He heard on the news that there is a drug that can treat AD and wants to know if he is a candidate for this treatment.

Mr. J would benefit from the education provided to Ms. W in Vignette 1. Patients such as Mr. J should be advised that while an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype conveys an increased risk for AD, it is not deterministic of the disease. While there are no specific preventive measures or treatments based on APOE genotype, careful medical care and lifestyle factors can offset some of the risk (see Vignette 5 for discussion).

Recently (and controversially), the FDA approved aducanumab, a drug that targets amyloid.6,36 Of note, brain amyloid is more common in individuals with the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype, such as Mr. J. However, there would be no point in testing Mr. J for brain amyloid because at present the drug is only indicated in symptomatic individuals—and, even in this setting, it is controversial. One reason for the controversy is that aducanumab has potentially severe adverse effects. Patients with the ε4/ε4 genotype should know that this genotype carries increased risk for the most serious adverse event, ARIA—which can include brain edema and microhemorrhages.

What lies ahead?

More research is needed to explore the impact that greater AD gene and biomarker testing will have on the health system and workforce development. In addition, graduate schools and training programs will need to prepare clinicians to address probabilistic risk estimates for common diseases, such as AD. Finally, health systems and medical groups that employ clinicians may want to offer simulated training—similar to the vignettes in this article—as a practice requirement or as continuing medical education. This may also allow health systems or medical groups to put in place frameworks that support clinicians in proactively answering questions for patients and families about APOE and other emerging markers of disease risk.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shana Stites, University of Pennsylvania, 3615 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected]

1. Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2018;14:535-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 PMCID:PMC5958625

2. Langlois CM, Bradbury A, Wood EM, et al. Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Generation Program: development of an APOE genetic counseling and disclosure process in the context of clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2019;5:705-716. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.013

3. Frank L, Wesson Ashford J, Bayley PJ, et al. Genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease: three wishes now that the genie is out of the bottle. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:421-423. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180629

4. Qian J, Wolters FJ, Beiser A, et al. APOE-related risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia for prevention trials: an analysis of four cohorts. PLOS Med. 2017;14:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002254

5. Sperling RA, Jack CR, Black SE, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:367-385. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2351

6. FDA. November 6, 2020: Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2021. www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting

7. Cummings J. Why aducanumab is important. Nat Med. 2021;27:1498-1498. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01478-4

8. Alexander GC, Karlawish J. The problem of aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1303-1304. doi: 10.7326/M21-2603

9. Mullard A. More Alzheimer’s drugs head for FDA review: what scientists are watching. Nature. 2021;599:544-545. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03410-9

10. Rosenberg A, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T, et al. Multidomain interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia: from finger to world-wide fingers. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019:1-8. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.41

11. FDA. Commissioner of the FDA allows marketing of first direct-to-consumer tests that provide genetic risk information for certain conditions. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed November 7, 2020. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-allows-marketing-first-direct-consumer-tests-provide-genetic-risk-information-certain-conditions

12. Blell M, Hunter MA. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing’s red herring: “genetic ancestry” and personalized medicine. Front Med. 2019;6:48. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00048

13. Ekstrand B, Scheers N, Rasmussen MK, et al. Brain foods - the role of diet in brain performance and health. Nutr Rev. 2021;79:693-708. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa091

14. Cherian L, Wang Y, Fakuda K, et al. Mediterranean-Dash Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019;6:267-273. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.28

15. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2020;396:413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

16. Livingston PG, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. The Lancet International Commission on Dementia Prevention and Care. 2017. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1567635/1/Livingston_Dementia_prevention_intervention_care.pdf

17. Peters U. What is the function of confirmation bias? Erkenntnis. April 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10670-020-00252-1

18. Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Cognitive resilience in APOE*ε4 carriers—is race important? Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:190-191. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.38

19. Farrer LA. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278:1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041

20. Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community: relation to apolipoprotein E allele status. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:185. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.185

21. Chung WW, Chen CA, Cupples LA, et al. A new scale measuring psychologic impact of genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:50-56. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318188429e

22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

23. Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165-173. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09

24. Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, et al. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:245-254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809578

25. Lineweaver TT, Bondi MW, Galasko D, et al. Effect of knowledge of APOE genotype on subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:201-208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121590

26. Karlawish J. Understanding the impact of learning an amyloid PET scan result: preliminary findings from the SOKRATES study. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2016;12:P325. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.594

27. Stites SD. Cognitively healthy individuals want to know their risk for Alzheimer’s disease: what should we do? J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:499-502. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171089

28. Milne S, Lomax C, Freeston MH. A review of the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and threat appraisal in anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;12:e38. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X19000230

29. Hebert EA, Dugas MJ. Behavioral experiments for intolerance of uncertainty: challenging the unknown in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019;26:421-436. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.07.007

30. Stites SD, Karlawish, J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Pract Neurol. Published June 2018. Accessed January 31, 2019. http://practicalneurology.com/2018/06/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia/

31. Solomon A, Turunen H, Ngandu T, et al. Effect of the apolipoprotein E genotype on cognitive change during a multidomain lifestyle intervention: a subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:462. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365

32. Peters R, Warwick J, Anstey KJ, et al. Blood pressure and dementia: what the SPRINT-MIND trial adds and what we still need to know. Neurology. 2019;92:1017-1018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007543

33. Musunuru K, Hershberger RE, Day SM, et al. Genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular diseases: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13: e000067. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067

34. Margaglione M, Seripa D, Gravina C, et al. Prevalence of apolipoprotein E alleles in healthy subjects and survivors of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:399-403. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.2.399

35. National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease genetics fact sheet. Reviewed December 24, 2019. Accessed April 10, 2022. www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet

36. Belluck P, Kaplan S, Robbins R. How Aduhelm, an unproven Alzheimer’s drug, got approved. The New York Times. Published July 19, 2021. Updated Oct. 20, 2021. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.nytimes.com/2021/07/19/health/alzheimers-drug-aduhelm-fda.html

Advances in Alzheimer disease (AD) genes and biomarkers now allow older adults to undergo testing and learn about their risk for AD.1 Current routes for doing so include testing in cardiology, screening for enrollment in secondary prevention trials (which use these tests to determine trial eligibility),2 and direct-to-consumer (DTC) services that provide these results as part of large panels.3 Patients may also obtain apolipoprotein (APOE) genotype information as part of an assessment of the risks and benefits of treatment with aducanumab (Aduhelm) or other anti-amyloid therapies that have been developed to stop or slow the progression of AD pathologies.

Expanded access to testing, in combination with limited guidance from DTC companies, suggests more older adults may consult their primary care physicians about this testing. In this narrative review, we use a vignette-driven approach to summarize the current scientific knowledge of the topic and to offer guidance on provider-patient discussions and follow-up.

First, a look at APOE genotyping

In cognitively unimpaired older adults, the APOE gene is a known risk factor for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD.3 A person has 2 alleles of the APOE gene, which has 3 variants: ε2, ε3, and ε4. The combination of alleles conveys varying levels of risk for developing clinical symptoms (TABLE 14), with ε4 increasing risk and ε2 decreasing risk compared to the more common ε3; thus the ε4/ε4 genotype conveys the most risk and the ε2/ε2 the least.

The APOE gene differs from other genes that have been identified in early-onset familial AD. These other genes, which include APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2, are deterministic genes that are fully penetrant. The APOE gene is not deterministic, meaning there is no combination of APOE alleles that are necessary or sufficient to cause late-onset AD dementia.

In clinical trials of amyloid-modifying therapies, the APOE gene has been shown to convey a risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).5 That is, in addition to conveying a risk for AD, the gene also conveys a risk for adverse effects of emerging treatments that can result in serious injury or death. This includes the drug aducanumab that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).6 In this review, we focus primarily on common clinical scenarios related to APOE. However, in light of the recent controversy over aducanumab and whether the drug should be offered to patients,7-9 we also describe how a patient’s APOE genotype may factor into drug candidacy decisions.

Testing, in clinic and “at home.” To date, practice guidelines have consistently recommended against APOE genetic testing in routine clinical practice. This is primarily due to low clinical prognostic utility and the lack of actionable results. Furthermore, no lifestyle or pharmaceutical interventions based on APOE genotype currently exist (although trials are underway10).

In 2017, the FDA approved marketing of DTC testing for the APOE gene.11 While DTC companies tend to issue standardized test result reports, the content and quality can vary widely. In fact, some provide risk estimates that are too high and too definitive and may not reflect the most recent science.12

Continue to: 7 clinical scenarios and how to approach them

7 clinical scenarios and how to approach them

Six of the following vignettes describe common clinical scenarios in which patients seek medical advice regarding APOE test results. The seventh vignette describes a patient whose APOE genotype may play a role in possible disease-modifying treatments down the road. Each vignette is designed to guide your approach to patient discussions and follow-up. Recommendations and considerations are also summarized in TABLE 213-16.

Vignette 1

Janet W, age 65, comes to the clinic for a new patient visit. She has no concerns about her memory but recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about her genetic health risks. Her results showed an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. She is now concerned about developing AD. Her mother was diagnosed with AD in her 70s.

Several important pieces of information can be conveyed by the primary care physician. First, patients such as Ms. W should be told that the APOE gene is not deterministic; many people, even those with 2 ε4 alleles, never develop dementia. Second, no specific preventive measures or treatments exist based on an individual’s APOE genotype (see Vignette 5 for additional discussion).

In this scenario, patients may ask for numeric quantification of their risk for dementia (see TABLE 14 for estimates). When conveying probabilistic risk, consider using simple percentages or pictographs (eg, out of 100 individuals with an ε4/ε4 genotype, 30 to 55 develop MCI or AD). Additionally, because people tend to exhibit confirmatory bias in thinking about probabilistic risk, providing opposing interpretations of an estimate may help them to consider alternative possibilities.17 For example

There are important caveats to the interpretation of APOE risk estimates. Because APOE risk estimates are probabilistic and averaged across a broader spectrum of people in large population cohorts,4 estimates may not accurately reflect a given individual’s risk. The ranges reflect the uncertainty in the estimates. The uncertainty arises from relatively small samples, the rareness of some genotypes (notably ε4/ε4) even in large samples, and variations in methods and sampling that can lead to differences in estimates beyond statistical variation.

Vignette 2

Eric J, age 85, presents for a new patient visit accompanied by his daughter. He lives independently, volunteers at a senior center several times a week, and exercises regularly, and neither he nor his daughter has any concerns about his memory. As a gift, he recently underwent DTC genetic testing and unexpectedly learned his APOE result, which is ε4/ε4. He wants to know about his chances of developing AD.

Risk conveyed by APOE genotype can be modified by a patient’s age. At age 85, Mr. J is healthy, highly functional, and cognitively unimpaired. Given his age, Mr. J has likely “outlived” much of the risk for dementia attributable to the ε4/ε4 genotype. His risk for dementia remains high, but this risk is likely driven more by age than by his APOE genotype. Data for individuals older than age 80 are limited, and thus risk estimates lack precision. Given Mr. J’s good health and functional status, his physician may want to perform a brief cognitive screening test to serve as a baseline for future evaluations.

Continue to: Vignette 3

Vignette 3

Audrey S is a 60-year-old African American woman who comes to the clinic for her annual visit. Because her father had AD, she recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about her APOE genotype and risk for AD. Her results are ε3/ε4. She is wondering what this may mean for her future.

Lack of diversity in research cohorts often limits the generalizability of estimates. For example, both the frequency and impact of APOE ε4 differ across racial groups.18 But most of the data on APOE lifetime risk estimates are from largely White patient samples. While APOE ε4 seems to confer increased risk for AD across sociocultural groups, these effects may be attenuated in African American and Hispanic populations.19,20 If Ms. S is interested in numeric risk estimates, the physician can provide the estimate for ε3/ε4 (20%-25% lifetime risk), with the important caveat that this estimate may not be reflective of her individual risk.

It may be prudent to determine whether Ms. S, at age 60, has subjective memory concerns and if she does, to perform a brief cognitive exam to serve as a baseline for future evaluations. Additionally, while the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA, 2008) prohibits health insurers and employers from discriminating based on genetic testing results, no legal provisions exist regarding long-term care, disability, or life insurance. Documented conversations about APOE test results in the medical record may become part of patients’ applications for these insurance products, and physicians should be cautious before documenting such discussions in the medical record.

Vignette 4

Tina L, age 60, comes to the clinic for a routine wellness visit. She recently developed an interest in genealogy and purchased a DNA testing kit to learn more about her family tree. As part of this testing, she unexpectedly learned that she has an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. She describes feeling distraught and anxious about what the result means for her future.

Ms. L’s reaction to receiving unexpected genetic results highlights a concern of DTC APOE testing. Her experience is quite different from individuals undergoing medically recommended genetic testing or those who are participating in research studies. They receive comprehensive pre-test counseling by licensed genetic counselors. The counseling includes psychological assessment, education, and discussion of expectations.2

In Ms. L’s case, it may be helpful to explain the limits of APOE lifetime risk estimates (see Vignettes 1-3). But it’s also important to address her concerns. There are behavior scales that can aid the assessment and monitoring of an individual’s well-being. The Impact of Genetic Testing for Alzheimer’s Disease (IGT-AD) scale is a tool that assesses psychological impact. It can help physicians to identify, monitor, and address concerns.21 Other useful tools include the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for depression, and a suicide or self-harm assessment.2,22,23 Finally, a follow-up visit at 2 to 4 weeks may be useful to reassess psychological well-being.

Vignette 4 (cont’d)

Ms. L returns to the clinic 2 weeks later, reporting continued anxiety about her APOE test result and feelings of hopelessness and despair.

Continue to: Some patients struggle...

Some patients struggle with knowing their APOE test result. Test result–related distress is often a combination of depression (as with Ms. L), anger, confusion, and grief.24 Cognitions often include worries about uncertainty, stereotyped threat, and internalized stigma.25,26 These issues can spill over to patient concerns about sharing an APOE test result with others.27

Intolerance of uncertainty is a transdiagnostic risk factor that can influence psychological suffering.28 Brief cognitive behavioral interventions that reinforce routines and encourage healthy and mindful practices may help alleviate patient distress from unexpected genetic test results.29 Interventions that personalize and validate an individual’s experience can help address internalized stigma.30 Referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist could be warranted. Additionally, referral to a genetic counselor may help provide patients with access to added expertise and guidance; useful web-based resources for identifying an appropriate referral include https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/consult/findingprofessional/ and https://findageneticcounselor.nsgc.org/.

Vignette 5

Bob K, age 65, comes to the clinic for his annual exam. He is a current smoker and says he’s hoping to be more physically active now that he is retired. He says that his mother and grandmother both had AD. He recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn more about his risk for AD. His learned his APOE genotype is ε3/ε4 and is wondering what he can do to decrease his chances of developing AD.

Mr. K likely would have benefited from pre-test counseling regarding the lack of current therapies to modify one’s genetic risk for AD. A pre-test counseling session often includes education about APOE testing and a brief evaluation to assess psychological readiness to undergo testing. Posttest educational information may help Mr. K avoid predatory advertising of products claiming—without scientific evidence—to modify risk for cognitive decline or to improve cognitive function.

There are several important pieces of information that should be communicated to Mr. K. Emerging evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that healthy lifestyle modifications may benefit cognition in individuals with APOE ε4 alleles.31 It would be prudent to address proper blood pressure control32 and counsel Mr. K on how he may be able to avoid diabetes through exercise and weight maintenance. Lifestyle recommendations for Mr. K could include: smoking cessation, regular aerobic exercise (eg, 150 min/wk), and a brain-healthy diet (eg, the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay [MIND] diet).13,14 Moreover, dementia prevention also includes appropriately managing depression and chronic illnesses and preventing social isolation and hearing loss.15,16 This information should be thoughtfully conveyed, as these interventions can improve overall (especially cardiovascular) health, as well as mitigating one’s personal risk for AD.

Vignette 6

Juan L, age 45, comes in for his annual physical exam. He has a strong family history of heart disease. His cardiologist recently ordered lipid disorder genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia. This panel included APOE testing and showed Mr. L’s genotype is ε2/ε4. He read that the APOE gene can be associated with an increased AD risk and asks for information about his genotype.

Mr. L received genetic testing results that were ordered by a physician for another health purpose. Current recommendations for genetic testing in cardiology advise pre-test genetic counseling.33 But this counseling may not include discussion of the relationship of APOE and risk for MCI or AD. This additional information may be unexpected for Mr. L. Moreover, its significance in the context of his present concerns about cardiovascular disease may influence his reaction.

Continue to: The ε2/ε4 genotype...

The ε2/ε4 genotype is rare. One study showed that in healthy adults, the frequency was 7 in 210 (0.02 [0.01-0.04]).34 Given the rarity of the ε2/ε4 genotype, data about it are sparse. However, since the ε4 allele increases risk but the ε2 allele decreases risk, it is likely that any increase in risk is more modest than with ε3/ε4. In addition, it would help Mr. L to know that AD occurs infrequently before age 60.35 Given his relatively young age, he is unlikely to develop AD any time in the near future. In addition, particularly if he starts early, he might be able to mitigate any increased risk through some of the advice provided to Mr. K in Vignette 5.

Vignette 7

Joe J, age 65, comes to the clinic for a new patient visit. He has no concerns about his memory but has a family history of dementia and recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about his genetic health risks. His results showed an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. He is concerned about developing AD. He heard on the news that there is a drug that can treat AD and wants to know if he is a candidate for this treatment.

Mr. J would benefit from the education provided to Ms. W in Vignette 1. Patients such as Mr. J should be advised that while an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype conveys an increased risk for AD, it is not deterministic of the disease. While there are no specific preventive measures or treatments based on APOE genotype, careful medical care and lifestyle factors can offset some of the risk (see Vignette 5 for discussion).

Recently (and controversially), the FDA approved aducanumab, a drug that targets amyloid.6,36 Of note, brain amyloid is more common in individuals with the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype, such as Mr. J. However, there would be no point in testing Mr. J for brain amyloid because at present the drug is only indicated in symptomatic individuals—and, even in this setting, it is controversial. One reason for the controversy is that aducanumab has potentially severe adverse effects. Patients with the ε4/ε4 genotype should know that this genotype carries increased risk for the most serious adverse event, ARIA—which can include brain edema and microhemorrhages.

What lies ahead?

More research is needed to explore the impact that greater AD gene and biomarker testing will have on the health system and workforce development. In addition, graduate schools and training programs will need to prepare clinicians to address probabilistic risk estimates for common diseases, such as AD. Finally, health systems and medical groups that employ clinicians may want to offer simulated training—similar to the vignettes in this article—as a practice requirement or as continuing medical education. This may also allow health systems or medical groups to put in place frameworks that support clinicians in proactively answering questions for patients and families about APOE and other emerging markers of disease risk.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shana Stites, University of Pennsylvania, 3615 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected]

Advances in Alzheimer disease (AD) genes and biomarkers now allow older adults to undergo testing and learn about their risk for AD.1 Current routes for doing so include testing in cardiology, screening for enrollment in secondary prevention trials (which use these tests to determine trial eligibility),2 and direct-to-consumer (DTC) services that provide these results as part of large panels.3 Patients may also obtain apolipoprotein (APOE) genotype information as part of an assessment of the risks and benefits of treatment with aducanumab (Aduhelm) or other anti-amyloid therapies that have been developed to stop or slow the progression of AD pathologies.

Expanded access to testing, in combination with limited guidance from DTC companies, suggests more older adults may consult their primary care physicians about this testing. In this narrative review, we use a vignette-driven approach to summarize the current scientific knowledge of the topic and to offer guidance on provider-patient discussions and follow-up.

First, a look at APOE genotyping

In cognitively unimpaired older adults, the APOE gene is a known risk factor for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or AD.3 A person has 2 alleles of the APOE gene, which has 3 variants: ε2, ε3, and ε4. The combination of alleles conveys varying levels of risk for developing clinical symptoms (TABLE 14), with ε4 increasing risk and ε2 decreasing risk compared to the more common ε3; thus the ε4/ε4 genotype conveys the most risk and the ε2/ε2 the least.

The APOE gene differs from other genes that have been identified in early-onset familial AD. These other genes, which include APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2, are deterministic genes that are fully penetrant. The APOE gene is not deterministic, meaning there is no combination of APOE alleles that are necessary or sufficient to cause late-onset AD dementia.

In clinical trials of amyloid-modifying therapies, the APOE gene has been shown to convey a risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA).5 That is, in addition to conveying a risk for AD, the gene also conveys a risk for adverse effects of emerging treatments that can result in serious injury or death. This includes the drug aducanumab that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).6 In this review, we focus primarily on common clinical scenarios related to APOE. However, in light of the recent controversy over aducanumab and whether the drug should be offered to patients,7-9 we also describe how a patient’s APOE genotype may factor into drug candidacy decisions.

Testing, in clinic and “at home.” To date, practice guidelines have consistently recommended against APOE genetic testing in routine clinical practice. This is primarily due to low clinical prognostic utility and the lack of actionable results. Furthermore, no lifestyle or pharmaceutical interventions based on APOE genotype currently exist (although trials are underway10).

In 2017, the FDA approved marketing of DTC testing for the APOE gene.11 While DTC companies tend to issue standardized test result reports, the content and quality can vary widely. In fact, some provide risk estimates that are too high and too definitive and may not reflect the most recent science.12

Continue to: 7 clinical scenarios and how to approach them

7 clinical scenarios and how to approach them

Six of the following vignettes describe common clinical scenarios in which patients seek medical advice regarding APOE test results. The seventh vignette describes a patient whose APOE genotype may play a role in possible disease-modifying treatments down the road. Each vignette is designed to guide your approach to patient discussions and follow-up. Recommendations and considerations are also summarized in TABLE 213-16.

Vignette 1

Janet W, age 65, comes to the clinic for a new patient visit. She has no concerns about her memory but recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about her genetic health risks. Her results showed an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. She is now concerned about developing AD. Her mother was diagnosed with AD in her 70s.

Several important pieces of information can be conveyed by the primary care physician. First, patients such as Ms. W should be told that the APOE gene is not deterministic; many people, even those with 2 ε4 alleles, never develop dementia. Second, no specific preventive measures or treatments exist based on an individual’s APOE genotype (see Vignette 5 for additional discussion).

In this scenario, patients may ask for numeric quantification of their risk for dementia (see TABLE 14 for estimates). When conveying probabilistic risk, consider using simple percentages or pictographs (eg, out of 100 individuals with an ε4/ε4 genotype, 30 to 55 develop MCI or AD). Additionally, because people tend to exhibit confirmatory bias in thinking about probabilistic risk, providing opposing interpretations of an estimate may help them to consider alternative possibilities.17 For example

There are important caveats to the interpretation of APOE risk estimates. Because APOE risk estimates are probabilistic and averaged across a broader spectrum of people in large population cohorts,4 estimates may not accurately reflect a given individual’s risk. The ranges reflect the uncertainty in the estimates. The uncertainty arises from relatively small samples, the rareness of some genotypes (notably ε4/ε4) even in large samples, and variations in methods and sampling that can lead to differences in estimates beyond statistical variation.

Vignette 2

Eric J, age 85, presents for a new patient visit accompanied by his daughter. He lives independently, volunteers at a senior center several times a week, and exercises regularly, and neither he nor his daughter has any concerns about his memory. As a gift, he recently underwent DTC genetic testing and unexpectedly learned his APOE result, which is ε4/ε4. He wants to know about his chances of developing AD.

Risk conveyed by APOE genotype can be modified by a patient’s age. At age 85, Mr. J is healthy, highly functional, and cognitively unimpaired. Given his age, Mr. J has likely “outlived” much of the risk for dementia attributable to the ε4/ε4 genotype. His risk for dementia remains high, but this risk is likely driven more by age than by his APOE genotype. Data for individuals older than age 80 are limited, and thus risk estimates lack precision. Given Mr. J’s good health and functional status, his physician may want to perform a brief cognitive screening test to serve as a baseline for future evaluations.

Continue to: Vignette 3

Vignette 3

Audrey S is a 60-year-old African American woman who comes to the clinic for her annual visit. Because her father had AD, she recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about her APOE genotype and risk for AD. Her results are ε3/ε4. She is wondering what this may mean for her future.

Lack of diversity in research cohorts often limits the generalizability of estimates. For example, both the frequency and impact of APOE ε4 differ across racial groups.18 But most of the data on APOE lifetime risk estimates are from largely White patient samples. While APOE ε4 seems to confer increased risk for AD across sociocultural groups, these effects may be attenuated in African American and Hispanic populations.19,20 If Ms. S is interested in numeric risk estimates, the physician can provide the estimate for ε3/ε4 (20%-25% lifetime risk), with the important caveat that this estimate may not be reflective of her individual risk.

It may be prudent to determine whether Ms. S, at age 60, has subjective memory concerns and if she does, to perform a brief cognitive exam to serve as a baseline for future evaluations. Additionally, while the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA, 2008) prohibits health insurers and employers from discriminating based on genetic testing results, no legal provisions exist regarding long-term care, disability, or life insurance. Documented conversations about APOE test results in the medical record may become part of patients’ applications for these insurance products, and physicians should be cautious before documenting such discussions in the medical record.

Vignette 4

Tina L, age 60, comes to the clinic for a routine wellness visit. She recently developed an interest in genealogy and purchased a DNA testing kit to learn more about her family tree. As part of this testing, she unexpectedly learned that she has an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. She describes feeling distraught and anxious about what the result means for her future.

Ms. L’s reaction to receiving unexpected genetic results highlights a concern of DTC APOE testing. Her experience is quite different from individuals undergoing medically recommended genetic testing or those who are participating in research studies. They receive comprehensive pre-test counseling by licensed genetic counselors. The counseling includes psychological assessment, education, and discussion of expectations.2

In Ms. L’s case, it may be helpful to explain the limits of APOE lifetime risk estimates (see Vignettes 1-3). But it’s also important to address her concerns. There are behavior scales that can aid the assessment and monitoring of an individual’s well-being. The Impact of Genetic Testing for Alzheimer’s Disease (IGT-AD) scale is a tool that assesses psychological impact. It can help physicians to identify, monitor, and address concerns.21 Other useful tools include the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) for depression, and a suicide or self-harm assessment.2,22,23 Finally, a follow-up visit at 2 to 4 weeks may be useful to reassess psychological well-being.

Vignette 4 (cont’d)

Ms. L returns to the clinic 2 weeks later, reporting continued anxiety about her APOE test result and feelings of hopelessness and despair.

Continue to: Some patients struggle...

Some patients struggle with knowing their APOE test result. Test result–related distress is often a combination of depression (as with Ms. L), anger, confusion, and grief.24 Cognitions often include worries about uncertainty, stereotyped threat, and internalized stigma.25,26 These issues can spill over to patient concerns about sharing an APOE test result with others.27

Intolerance of uncertainty is a transdiagnostic risk factor that can influence psychological suffering.28 Brief cognitive behavioral interventions that reinforce routines and encourage healthy and mindful practices may help alleviate patient distress from unexpected genetic test results.29 Interventions that personalize and validate an individual’s experience can help address internalized stigma.30 Referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist could be warranted. Additionally, referral to a genetic counselor may help provide patients with access to added expertise and guidance; useful web-based resources for identifying an appropriate referral include https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/understanding/consult/findingprofessional/ and https://findageneticcounselor.nsgc.org/.

Vignette 5

Bob K, age 65, comes to the clinic for his annual exam. He is a current smoker and says he’s hoping to be more physically active now that he is retired. He says that his mother and grandmother both had AD. He recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn more about his risk for AD. His learned his APOE genotype is ε3/ε4 and is wondering what he can do to decrease his chances of developing AD.

Mr. K likely would have benefited from pre-test counseling regarding the lack of current therapies to modify one’s genetic risk for AD. A pre-test counseling session often includes education about APOE testing and a brief evaluation to assess psychological readiness to undergo testing. Posttest educational information may help Mr. K avoid predatory advertising of products claiming—without scientific evidence—to modify risk for cognitive decline or to improve cognitive function.

There are several important pieces of information that should be communicated to Mr. K. Emerging evidence from randomized controlled trials suggests that healthy lifestyle modifications may benefit cognition in individuals with APOE ε4 alleles.31 It would be prudent to address proper blood pressure control32 and counsel Mr. K on how he may be able to avoid diabetes through exercise and weight maintenance. Lifestyle recommendations for Mr. K could include: smoking cessation, regular aerobic exercise (eg, 150 min/wk), and a brain-healthy diet (eg, the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay [MIND] diet).13,14 Moreover, dementia prevention also includes appropriately managing depression and chronic illnesses and preventing social isolation and hearing loss.15,16 This information should be thoughtfully conveyed, as these interventions can improve overall (especially cardiovascular) health, as well as mitigating one’s personal risk for AD.

Vignette 6

Juan L, age 45, comes in for his annual physical exam. He has a strong family history of heart disease. His cardiologist recently ordered lipid disorder genetic testing for familial hypercholesterolemia. This panel included APOE testing and showed Mr. L’s genotype is ε2/ε4. He read that the APOE gene can be associated with an increased AD risk and asks for information about his genotype.

Mr. L received genetic testing results that were ordered by a physician for another health purpose. Current recommendations for genetic testing in cardiology advise pre-test genetic counseling.33 But this counseling may not include discussion of the relationship of APOE and risk for MCI or AD. This additional information may be unexpected for Mr. L. Moreover, its significance in the context of his present concerns about cardiovascular disease may influence his reaction.

Continue to: The ε2/ε4 genotype...

The ε2/ε4 genotype is rare. One study showed that in healthy adults, the frequency was 7 in 210 (0.02 [0.01-0.04]).34 Given the rarity of the ε2/ε4 genotype, data about it are sparse. However, since the ε4 allele increases risk but the ε2 allele decreases risk, it is likely that any increase in risk is more modest than with ε3/ε4. In addition, it would help Mr. L to know that AD occurs infrequently before age 60.35 Given his relatively young age, he is unlikely to develop AD any time in the near future. In addition, particularly if he starts early, he might be able to mitigate any increased risk through some of the advice provided to Mr. K in Vignette 5.

Vignette 7

Joe J, age 65, comes to the clinic for a new patient visit. He has no concerns about his memory but has a family history of dementia and recently purchased DTC genetic testing to learn about his genetic health risks. His results showed an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype. He is concerned about developing AD. He heard on the news that there is a drug that can treat AD and wants to know if he is a candidate for this treatment.

Mr. J would benefit from the education provided to Ms. W in Vignette 1. Patients such as Mr. J should be advised that while an APOE ε4/ε4 genotype conveys an increased risk for AD, it is not deterministic of the disease. While there are no specific preventive measures or treatments based on APOE genotype, careful medical care and lifestyle factors can offset some of the risk (see Vignette 5 for discussion).

Recently (and controversially), the FDA approved aducanumab, a drug that targets amyloid.6,36 Of note, brain amyloid is more common in individuals with the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype, such as Mr. J. However, there would be no point in testing Mr. J for brain amyloid because at present the drug is only indicated in symptomatic individuals—and, even in this setting, it is controversial. One reason for the controversy is that aducanumab has potentially severe adverse effects. Patients with the ε4/ε4 genotype should know that this genotype carries increased risk for the most serious adverse event, ARIA—which can include brain edema and microhemorrhages.

What lies ahead?

More research is needed to explore the impact that greater AD gene and biomarker testing will have on the health system and workforce development. In addition, graduate schools and training programs will need to prepare clinicians to address probabilistic risk estimates for common diseases, such as AD. Finally, health systems and medical groups that employ clinicians may want to offer simulated training—similar to the vignettes in this article—as a practice requirement or as continuing medical education. This may also allow health systems or medical groups to put in place frameworks that support clinicians in proactively answering questions for patients and families about APOE and other emerging markers of disease risk.

CORRESPONDENCE

Shana Stites, University of Pennsylvania, 3615 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected]

1. Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2018;14:535-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 PMCID:PMC5958625

2. Langlois CM, Bradbury A, Wood EM, et al. Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Generation Program: development of an APOE genetic counseling and disclosure process in the context of clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2019;5:705-716. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.013

3. Frank L, Wesson Ashford J, Bayley PJ, et al. Genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease: three wishes now that the genie is out of the bottle. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:421-423. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180629

4. Qian J, Wolters FJ, Beiser A, et al. APOE-related risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia for prevention trials: an analysis of four cohorts. PLOS Med. 2017;14:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002254

5. Sperling RA, Jack CR, Black SE, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:367-385. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2351

6. FDA. November 6, 2020: Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2021. www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting

7. Cummings J. Why aducanumab is important. Nat Med. 2021;27:1498-1498. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01478-4

8. Alexander GC, Karlawish J. The problem of aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1303-1304. doi: 10.7326/M21-2603

9. Mullard A. More Alzheimer’s drugs head for FDA review: what scientists are watching. Nature. 2021;599:544-545. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03410-9

10. Rosenberg A, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T, et al. Multidomain interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia: from finger to world-wide fingers. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019:1-8. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.41

11. FDA. Commissioner of the FDA allows marketing of first direct-to-consumer tests that provide genetic risk information for certain conditions. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed November 7, 2020. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-allows-marketing-first-direct-consumer-tests-provide-genetic-risk-information-certain-conditions

12. Blell M, Hunter MA. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing’s red herring: “genetic ancestry” and personalized medicine. Front Med. 2019;6:48. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00048

13. Ekstrand B, Scheers N, Rasmussen MK, et al. Brain foods - the role of diet in brain performance and health. Nutr Rev. 2021;79:693-708. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa091

14. Cherian L, Wang Y, Fakuda K, et al. Mediterranean-Dash Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019;6:267-273. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.28

15. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2020;396:413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

16. Livingston PG, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. The Lancet International Commission on Dementia Prevention and Care. 2017. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1567635/1/Livingston_Dementia_prevention_intervention_care.pdf

17. Peters U. What is the function of confirmation bias? Erkenntnis. April 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10670-020-00252-1

18. Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Cognitive resilience in APOE*ε4 carriers—is race important? Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:190-191. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.38

19. Farrer LA. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278:1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041

20. Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community: relation to apolipoprotein E allele status. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:185. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.185

21. Chung WW, Chen CA, Cupples LA, et al. A new scale measuring psychologic impact of genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:50-56. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318188429e

22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

23. Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165-173. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09

24. Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, et al. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:245-254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809578

25. Lineweaver TT, Bondi MW, Galasko D, et al. Effect of knowledge of APOE genotype on subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:201-208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121590

26. Karlawish J. Understanding the impact of learning an amyloid PET scan result: preliminary findings from the SOKRATES study. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2016;12:P325. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.594

27. Stites SD. Cognitively healthy individuals want to know their risk for Alzheimer’s disease: what should we do? J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:499-502. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171089

28. Milne S, Lomax C, Freeston MH. A review of the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and threat appraisal in anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;12:e38. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X19000230

29. Hebert EA, Dugas MJ. Behavioral experiments for intolerance of uncertainty: challenging the unknown in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019;26:421-436. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.07.007

30. Stites SD, Karlawish, J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Pract Neurol. Published June 2018. Accessed January 31, 2019. http://practicalneurology.com/2018/06/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia/

31. Solomon A, Turunen H, Ngandu T, et al. Effect of the apolipoprotein E genotype on cognitive change during a multidomain lifestyle intervention: a subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:462. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365

32. Peters R, Warwick J, Anstey KJ, et al. Blood pressure and dementia: what the SPRINT-MIND trial adds and what we still need to know. Neurology. 2019;92:1017-1018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007543

33. Musunuru K, Hershberger RE, Day SM, et al. Genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular diseases: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13: e000067. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067

34. Margaglione M, Seripa D, Gravina C, et al. Prevalence of apolipoprotein E alleles in healthy subjects and survivors of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:399-403. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.2.399

35. National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease genetics fact sheet. Reviewed December 24, 2019. Accessed April 10, 2022. www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet

36. Belluck P, Kaplan S, Robbins R. How Aduhelm, an unproven Alzheimer’s drug, got approved. The New York Times. Published July 19, 2021. Updated Oct. 20, 2021. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.nytimes.com/2021/07/19/health/alzheimers-drug-aduhelm-fda.html

1. Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2018;14:535-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 PMCID:PMC5958625

2. Langlois CM, Bradbury A, Wood EM, et al. Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative Generation Program: development of an APOE genetic counseling and disclosure process in the context of clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2019;5:705-716. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.013

3. Frank L, Wesson Ashford J, Bayley PJ, et al. Genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease: three wishes now that the genie is out of the bottle. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:421-423. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180629

4. Qian J, Wolters FJ, Beiser A, et al. APOE-related risk of mild cognitive impairment and dementia for prevention trials: an analysis of four cohorts. PLOS Med. 2017;14:e1002254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002254

5. Sperling RA, Jack CR, Black SE, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:367-385. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.05.2351

6. FDA. November 6, 2020: Meeting of the Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting Announcement. Published November 12, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2021. www.fda.gov/advisory-committees/advisory-committee-calendar/november-6-2020-meeting-peripheral-and-central-nervous-system-drugs-advisory-committee-meeting

7. Cummings J. Why aducanumab is important. Nat Med. 2021;27:1498-1498. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01478-4

8. Alexander GC, Karlawish J. The problem of aducanumab for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:1303-1304. doi: 10.7326/M21-2603

9. Mullard A. More Alzheimer’s drugs head for FDA review: what scientists are watching. Nature. 2021;599:544-545. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03410-9

10. Rosenberg A, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T, et al. Multidomain interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and dementia: from finger to world-wide fingers. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019:1-8. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.41

11. FDA. Commissioner of the FDA allows marketing of first direct-to-consumer tests that provide genetic risk information for certain conditions. Published March 24, 2020. Accessed November 7, 2020. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-allows-marketing-first-direct-consumer-tests-provide-genetic-risk-information-certain-conditions

12. Blell M, Hunter MA. Direct-to-consumer genetic testing’s red herring: “genetic ancestry” and personalized medicine. Front Med. 2019;6:48. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00048

13. Ekstrand B, Scheers N, Rasmussen MK, et al. Brain foods - the role of diet in brain performance and health. Nutr Rev. 2021;79:693-708. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa091

14. Cherian L, Wang Y, Fakuda K, et al. Mediterranean-Dash Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2019;6:267-273. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2019.28

15. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. The Lancet. 2020;396:413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

16. Livingston PG, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. The Lancet International Commission on Dementia Prevention and Care. 2017. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1567635/1/Livingston_Dementia_prevention_intervention_care.pdf

17. Peters U. What is the function of confirmation bias? Erkenntnis. April 2020. doi: 10.1007/s10670-020-00252-1

18. Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Cognitive resilience in APOE*ε4 carriers—is race important? Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:190-191. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.38

19. Farrer LA. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1997;278:1349. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041

20. Evans DA, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, et al. Incidence of Alzheimer disease in a biracial urban community: relation to apolipoprotein E allele status. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:185. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.2.185

21. Chung WW, Chen CA, Cupples LA, et al. A new scale measuring psychologic impact of genetic susceptibility testing for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:50-56. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318188429e

22. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

23. Yesavage JA, Sheikh JI. 9/Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:165-173. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09

24. Green RC, Roberts JS, Cupples LA, et al. Disclosure of APOE genotype for risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:245-254. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809578

25. Lineweaver TT, Bondi MW, Galasko D, et al. Effect of knowledge of APOE genotype on subjective and objective memory performance in healthy older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:201-208. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121590

26. Karlawish J. Understanding the impact of learning an amyloid PET scan result: preliminary findings from the SOKRATES study. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2016;12:P325. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.594

27. Stites SD. Cognitively healthy individuals want to know their risk for Alzheimer’s disease: what should we do? J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:499-502. doi: 10.3233/JAD-171089

28. Milne S, Lomax C, Freeston MH. A review of the relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and threat appraisal in anxiety. Cogn Behav Ther. 2019;12:e38. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X19000230

29. Hebert EA, Dugas MJ. Behavioral experiments for intolerance of uncertainty: challenging the unknown in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Pract. 2019;26:421-436. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2018.07.007

30. Stites SD, Karlawish, J. Stigma of Alzheimer’s disease dementia: considerations for practice. Pract Neurol. Published June 2018. Accessed January 31, 2019. http://practicalneurology.com/2018/06/stigma-of-alzheimers-disease-dementia/

31. Solomon A, Turunen H, Ngandu T, et al. Effect of the apolipoprotein E genotype on cognitive change during a multidomain lifestyle intervention: a subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:462. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.4365

32. Peters R, Warwick J, Anstey KJ, et al. Blood pressure and dementia: what the SPRINT-MIND trial adds and what we still need to know. Neurology. 2019;92:1017-1018. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007543

33. Musunuru K, Hershberger RE, Day SM, et al. Genetic testing for inherited cardiovascular diseases: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2020;13: e000067. doi: 10.1161/HCG.0000000000000067

34. Margaglione M, Seripa D, Gravina C, et al. Prevalence of apolipoprotein E alleles in healthy subjects and survivors of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1998;29:399-403. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.29.2.399

35. National Institute on Aging. Alzheimer’s disease genetics fact sheet. Reviewed December 24, 2019. Accessed April 10, 2022. www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-disease-genetics-fact-sheet

36. Belluck P, Kaplan S, Robbins R. How Aduhelm, an unproven Alzheimer’s drug, got approved. The New York Times. Published July 19, 2021. Updated Oct. 20, 2021. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.nytimes.com/2021/07/19/health/alzheimers-drug-aduhelm-fda.html

Ex–hospital porter a neglected giant of cancer research

We have a half-forgotten Indian immigrant to thank – a hospital night porter turned biochemist –for revolutionizing treatment of leukemia, the once deadly childhood scourge that is still the most common pediatric cancer.

Dr. Yellapragada SubbaRow has been called the “father of chemotherapy” for developing methotrexate, a powerful, inexpensive therapy for leukemia and other diseases, and he is celebrated for additional scientific achievements. Yet Dr. SubbaRow’s life was marked more by struggle than glory.

Born poor in southeastern India, he nearly succumbed to a tropical disease that killed two older brothers, and he didn’t focus on schoolwork until his father died. Later, prejudice dogged his years as an immigrant to the United States, and a blood clot took his life at the age of 53.

Scientifically, however, Dr. SubbaRow (pronounced sue-buh-rao) triumphed, despite mammoth challenges and a lack of recognition that persists to this day. National Cancer Research Month is a fitting time to look back on his extraordinary life and work and pay tribute to his accomplishments.

‘Yella,’ folic acid, and a paradigm shift

No one appreciates Dr. SubbaRow more than a cadre of Indian-born physicians who have kept his legacy alive in journal articles, presentations, and a Pulitzer Prize-winning book. Among them is author and oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee, MD, who chronicled Dr. SubbaRow’s achievements in his New York Times No. 1 bestseller, “The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer.”

As Dr. Mukherjee wrote, Dr. SubbaRow was a “pioneer in many ways, a physician turned cellular physiologist, a chemist who had accidentally wandered into biology.” (Per Indian tradition, SubbaRow is the doctor’s first name, and Yellapragada is his surname, but medical literature uses SubbaRow as his cognomen, with some variations in spelling. Dr. Mukherjee wrote that his friends called him “Yella.”)

Dr. SubbaRow came to the United States in 1923, after enduring a difficult childhood and young adulthood. He’d survived bouts of religious fervor, childhood rebellion (including a bid to run away from home and become a banana trader), and a failed arranged marriage. His wife bore him a child who died in infancy. He left it all behind.

In Boston, medical officials rejected his degree. Broke, he worked for a time as a night porter at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, changing sheets and cleaning urinals. To a poor but proud high-caste Indian Brahmin, the culture shock of carrying out these tasks must have been especially jarring.

Dr. SubbaRow went on to earn a diploma from Harvard Medical School, also in Boston, and became a junior faculty member. As a foreigner, Dr. Mukherjee wrote, Dr. SubbaRow was a “reclusive, nocturnal, heavily accented vegetarian,” so different from his colleagues that advancement seemed impossible. Despite his pioneering biochemistry work, Harvard later declined to offer Dr. SubbaRow a tenured faculty position.

By the early 1940s, he took a job at an upstate New York pharmaceutical company called Lederle Labs (later purchased by Pfizer). At Lederle, Dr. SubbaRow strove to synthesize the vitamin known as folic acid. He ended up creating a kind of antivitamin, a lookalike that acted like folic acid but only succeeded in gumming up the works in receptors. But what good would it do to stop the body from absorbing folic acid? Plenty, it turned out.

Discoveries pile up, but credit and fame prove elusive

Dr. SubbaRow was no stranger to producing landmark biological work. He’d previously codiscovered phosphocreatine and ATP, which are crucial to muscular contractions. However, “in 1935, he had to disown the extent of his role in the discovery of the color test related to phosphorus, instead giving the credit to his co-author, who was being considered for promotion to a full professorship at Harvard,” wrote author Gerald Posner in his 2020 book, “Pharma: Greed, Lies and the Poisoning of America.”

Houston-area oncologist Kirtan Nautiyal, MD, who paid tribute to Dr. SubbaRow in a 2018 article, contended that “with his Indian instinct for self-effacement, he had irreparably sabotaged his own career.”

Dr. SubbaRow and his team also developed “the first effective treatment of filariasis, which causes elephantiasis of the lower limbs and genitals in millions of people, mainly in tropical countries,” Dr. Nautiyal wrote. “Later in the decade, his antibiotic program generated polymyxin, the first effective treatment against the class of bacteria called Gram negatives, and aureomycin, the first “broad-spectrum’ antibiotic.” (Aureomycin is also the first tetracycline antibiotic.)

Dr. SubbaRow’s discovery of a folic acid antagonist would again go largely unheralded. But first came the realization that folic acid made childhood leukemia worse, not better, and the prospect that this process could potentially be reversed.

Rise of methotrexate and fall of leukemia