User login

Mosquitoes genetically modified to stop disease pass early test

As part of the test, scientists released nearly 5 million genetically engineered male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of 7 months in the Florida Keys.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite people, and these were also modified so they would transmit a gene to female offspring that causes them to die before they can reproduce. In theory, this means the population of A. aegypti mosquitoes would die off over time, so they wouldn’t spread diseases any more.

The goal of this pilot project in Florida was to see if these genetically modified male mosquitoes could successfully mate with females in the wild, and to confirm whether their female offspring would indeed die before they could reproduce. On both counts, the experiment was a success, Oxitec, the biotechnology company developing these engineered A. aegypti mosquitoes, said in a webinar.

More testing in Florida and California

Based on the results from this preliminary research, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved additional pilot projects in Florida and California, the company said in a statement.

“Given the growing health threat this mosquito poses across the U.S., we’re working to make this technology available and accessible,” Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s chief executive, said in the statement. “These pilot programs, wherein we can demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in different climate settings, will play an important role in doing so.”

A. aegypti mosquitoes can spread several serious infectious diseases to humans, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preliminary tests of the genetically modified mosquitoes weren’t designed to determine whether these engineered insects might stop the spread of these diseases. The goal of the initial tests was simply to see how reproduction played out once the genetically modified males were released.

The genetically engineered males successfully mated with females in the wild, the company reports. Scientists collected more than 22,000 eggs laid by these females from traps set out around the community in spots like flowerpots and trash cans.

In the lab, researchers confirmed that the female offspring from these pairings inherited a lethal gene designed to cause their death before adulthood. The lethal gene was transmitted to female offspring across multiple generations, scientists also found.

Many more trials would be needed before these genetically modified mosquitoes could be released in the wild on a larger scale – particularly because the tests done so far haven’t demonstrated that these engineered bugs can prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Releasing genetically modified A. aegypti mosquitoes into the wild won’t reduce the need for pesticides because most mosquitoes in the United States aren’t from this species.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As part of the test, scientists released nearly 5 million genetically engineered male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of 7 months in the Florida Keys.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite people, and these were also modified so they would transmit a gene to female offspring that causes them to die before they can reproduce. In theory, this means the population of A. aegypti mosquitoes would die off over time, so they wouldn’t spread diseases any more.

The goal of this pilot project in Florida was to see if these genetically modified male mosquitoes could successfully mate with females in the wild, and to confirm whether their female offspring would indeed die before they could reproduce. On both counts, the experiment was a success, Oxitec, the biotechnology company developing these engineered A. aegypti mosquitoes, said in a webinar.

More testing in Florida and California

Based on the results from this preliminary research, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved additional pilot projects in Florida and California, the company said in a statement.

“Given the growing health threat this mosquito poses across the U.S., we’re working to make this technology available and accessible,” Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s chief executive, said in the statement. “These pilot programs, wherein we can demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in different climate settings, will play an important role in doing so.”

A. aegypti mosquitoes can spread several serious infectious diseases to humans, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preliminary tests of the genetically modified mosquitoes weren’t designed to determine whether these engineered insects might stop the spread of these diseases. The goal of the initial tests was simply to see how reproduction played out once the genetically modified males were released.

The genetically engineered males successfully mated with females in the wild, the company reports. Scientists collected more than 22,000 eggs laid by these females from traps set out around the community in spots like flowerpots and trash cans.

In the lab, researchers confirmed that the female offspring from these pairings inherited a lethal gene designed to cause their death before adulthood. The lethal gene was transmitted to female offspring across multiple generations, scientists also found.

Many more trials would be needed before these genetically modified mosquitoes could be released in the wild on a larger scale – particularly because the tests done so far haven’t demonstrated that these engineered bugs can prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Releasing genetically modified A. aegypti mosquitoes into the wild won’t reduce the need for pesticides because most mosquitoes in the United States aren’t from this species.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

As part of the test, scientists released nearly 5 million genetically engineered male Aedes aegypti mosquitoes over the course of 7 months in the Florida Keys.

Male mosquitoes don’t bite people, and these were also modified so they would transmit a gene to female offspring that causes them to die before they can reproduce. In theory, this means the population of A. aegypti mosquitoes would die off over time, so they wouldn’t spread diseases any more.

The goal of this pilot project in Florida was to see if these genetically modified male mosquitoes could successfully mate with females in the wild, and to confirm whether their female offspring would indeed die before they could reproduce. On both counts, the experiment was a success, Oxitec, the biotechnology company developing these engineered A. aegypti mosquitoes, said in a webinar.

More testing in Florida and California

Based on the results from this preliminary research, the Environmental Protection Agency has approved additional pilot projects in Florida and California, the company said in a statement.

“Given the growing health threat this mosquito poses across the U.S., we’re working to make this technology available and accessible,” Grey Frandsen, Oxitec’s chief executive, said in the statement. “These pilot programs, wherein we can demonstrate the technology’s effectiveness in different climate settings, will play an important role in doing so.”

A. aegypti mosquitoes can spread several serious infectious diseases to humans, including dengue, Zika, yellow fever and chikungunya, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Preliminary tests of the genetically modified mosquitoes weren’t designed to determine whether these engineered insects might stop the spread of these diseases. The goal of the initial tests was simply to see how reproduction played out once the genetically modified males were released.

The genetically engineered males successfully mated with females in the wild, the company reports. Scientists collected more than 22,000 eggs laid by these females from traps set out around the community in spots like flowerpots and trash cans.

In the lab, researchers confirmed that the female offspring from these pairings inherited a lethal gene designed to cause their death before adulthood. The lethal gene was transmitted to female offspring across multiple generations, scientists also found.

Many more trials would be needed before these genetically modified mosquitoes could be released in the wild on a larger scale – particularly because the tests done so far haven’t demonstrated that these engineered bugs can prevent the spread of infectious disease.

Releasing genetically modified A. aegypti mosquitoes into the wild won’t reduce the need for pesticides because most mosquitoes in the United States aren’t from this species.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette

A 63-YEAR-OLD SOUTHEAST ASIAN WOMAN presented with early satiety, mild swelling of her lower extremities, and several months of progressive shortness of breath that had become severe (provoked by activities of daily living). She had a history of longstanding, rate-controlled atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation. She also had a history of mitral valve stenosis that was treated 30 years earlier with mechanical valve replacement. The patient had previously been treated out of state and prior records were not available.

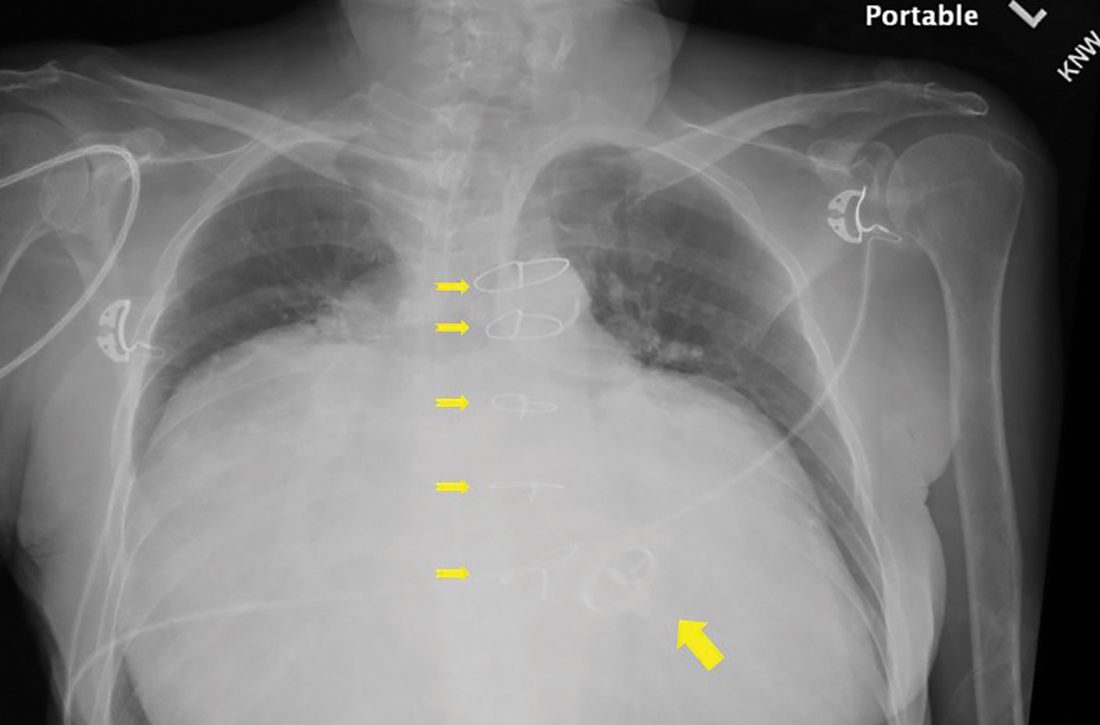

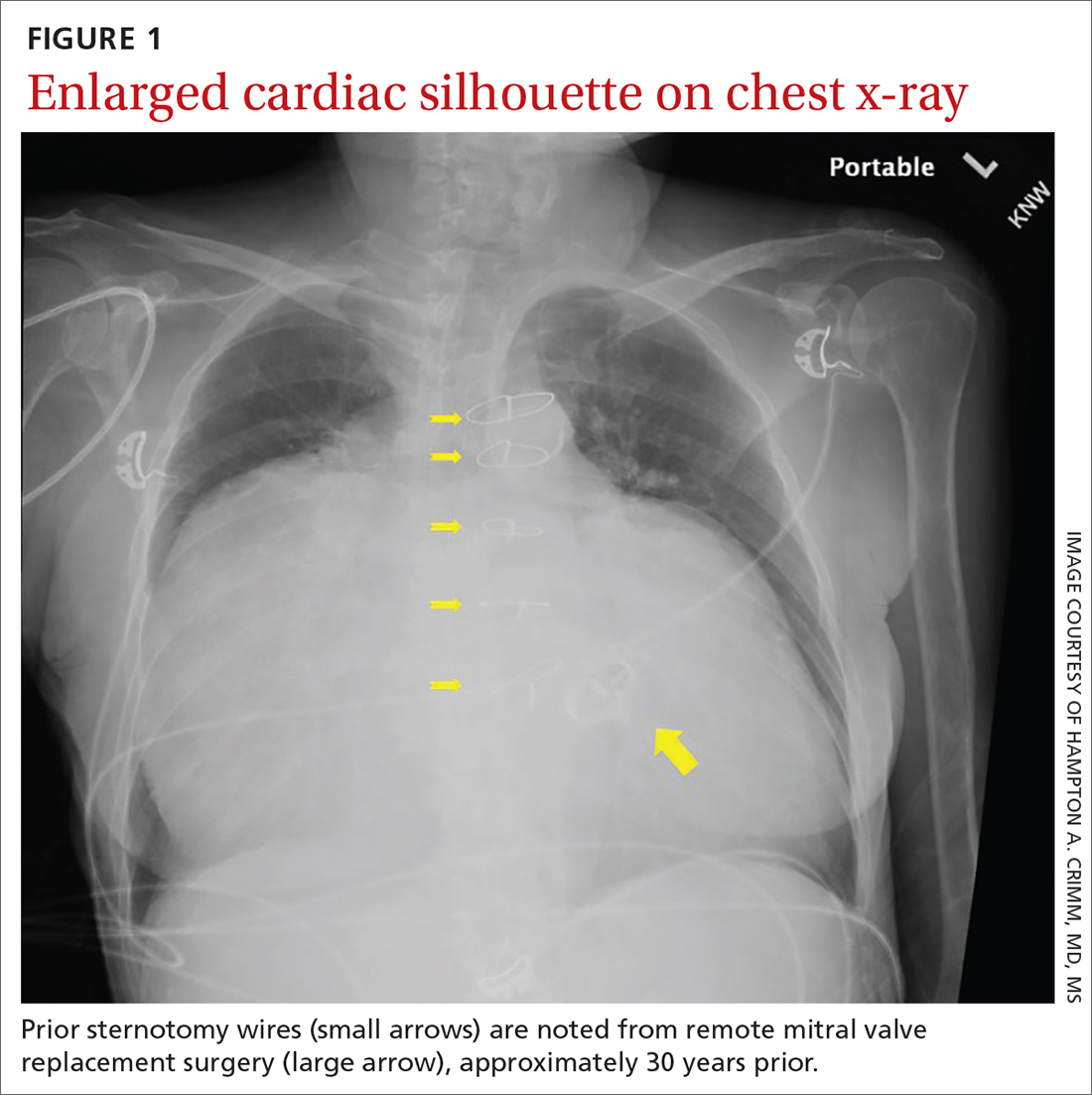

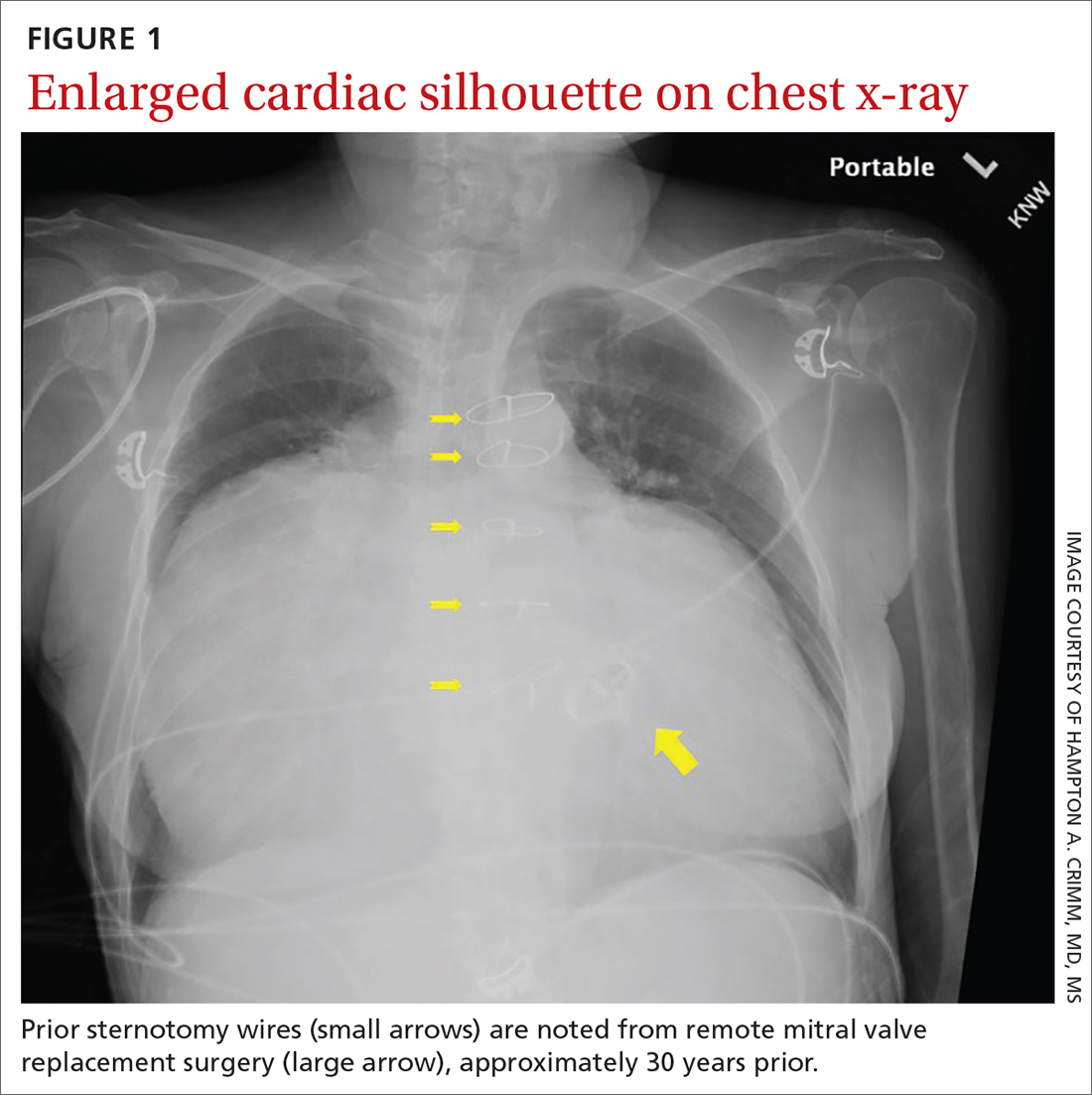

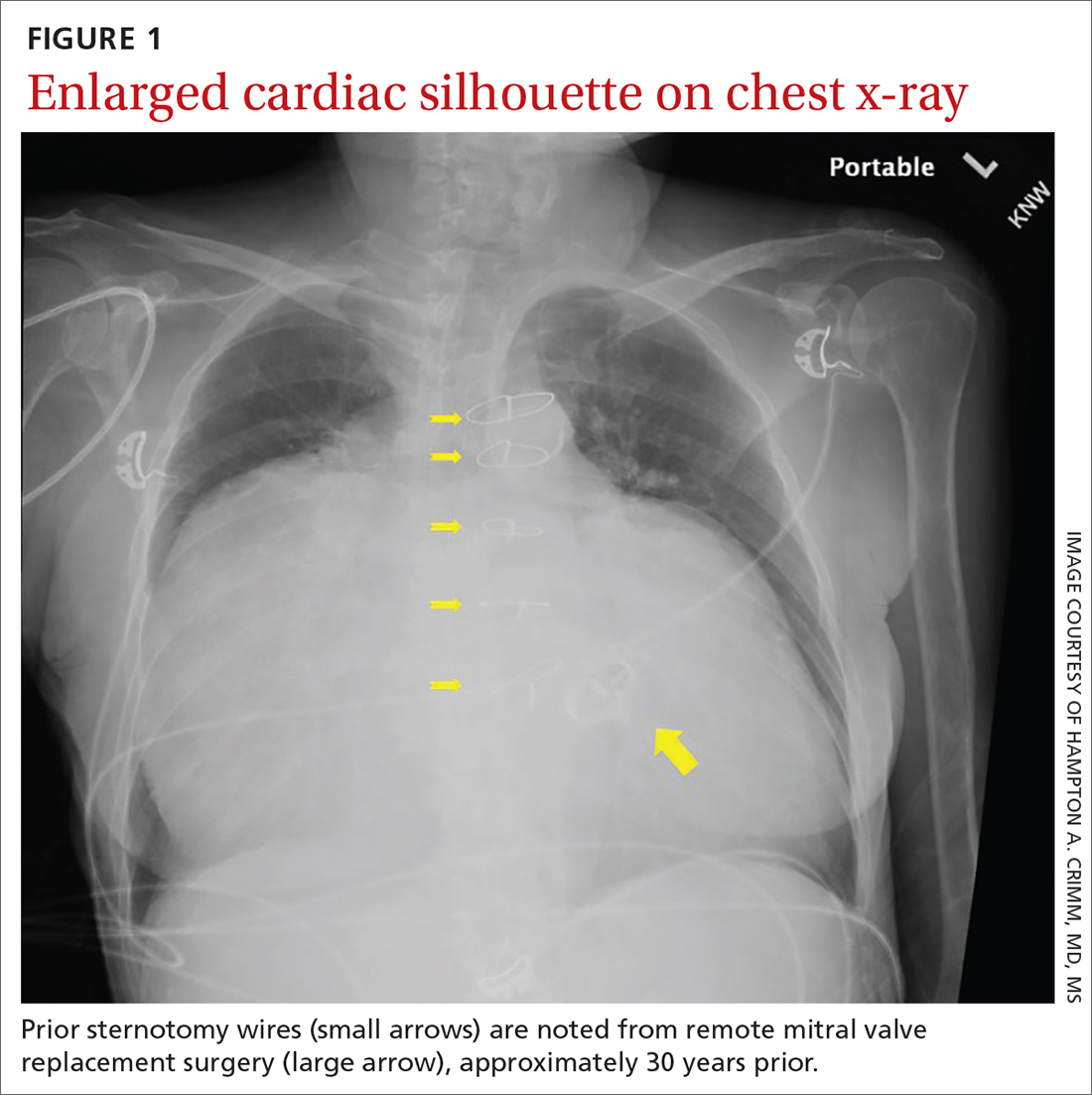

Chest radiography (CXR) was performed as part of the initial work-up (FIGURE 1) and demonstrated a substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette spanning the entire width of the chest without significant pleural effusion or evidence of airspace disease. Suspecting a primary cardiac pathology in this patient, we explored clinical findings of heart failure with transthoracic echocardiography.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Severe tricuspid valve regurgitation secondary to rheumatic heart disease

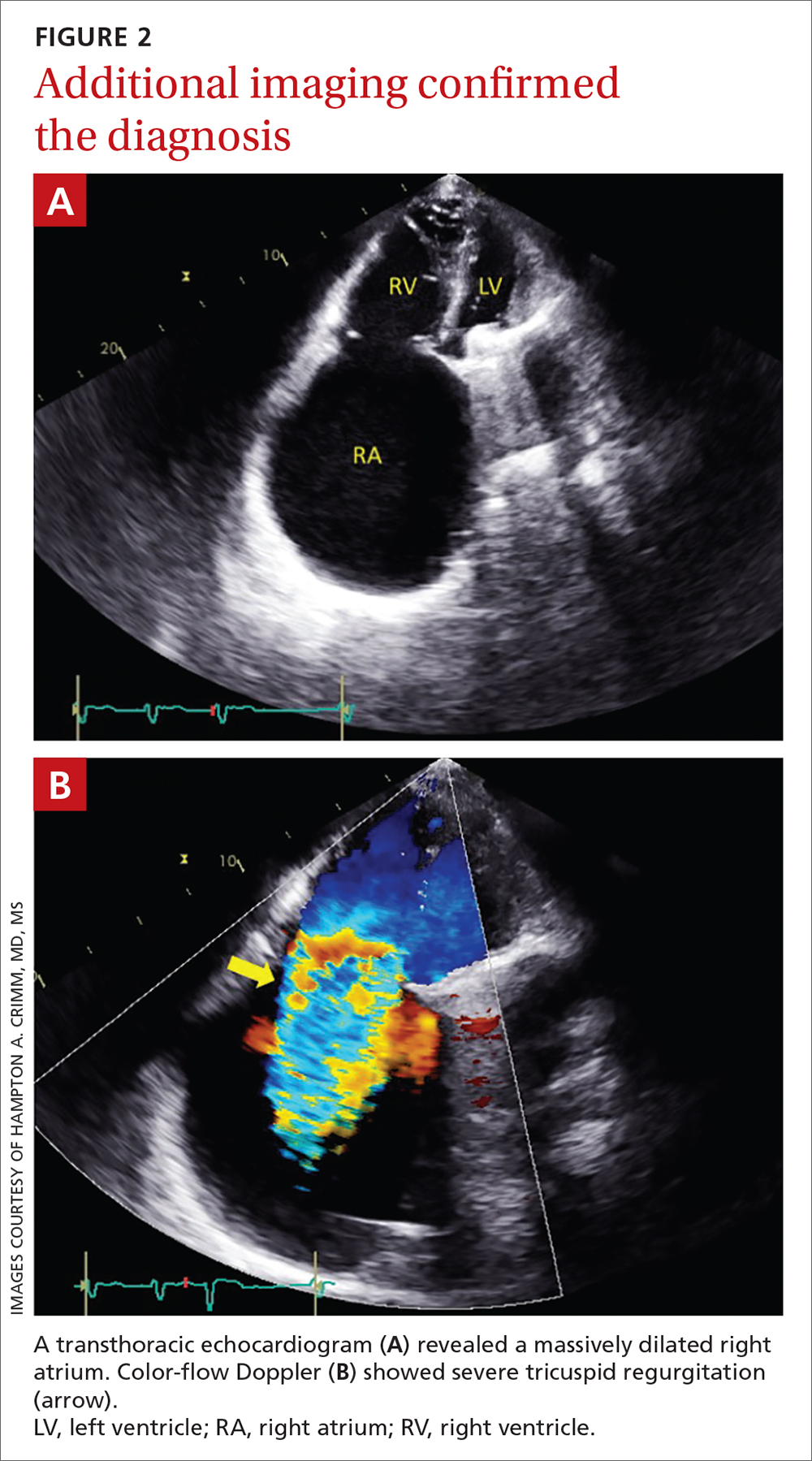

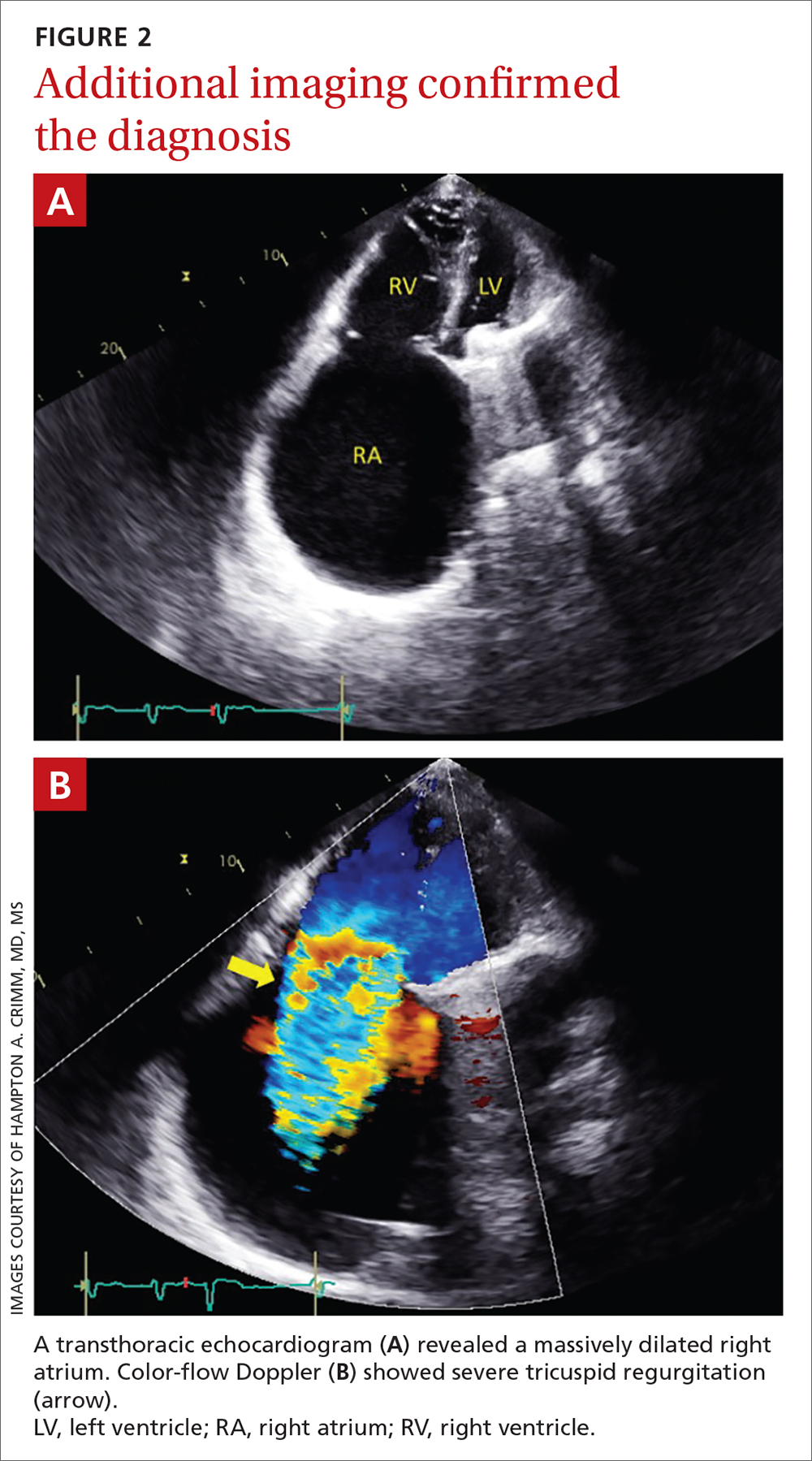

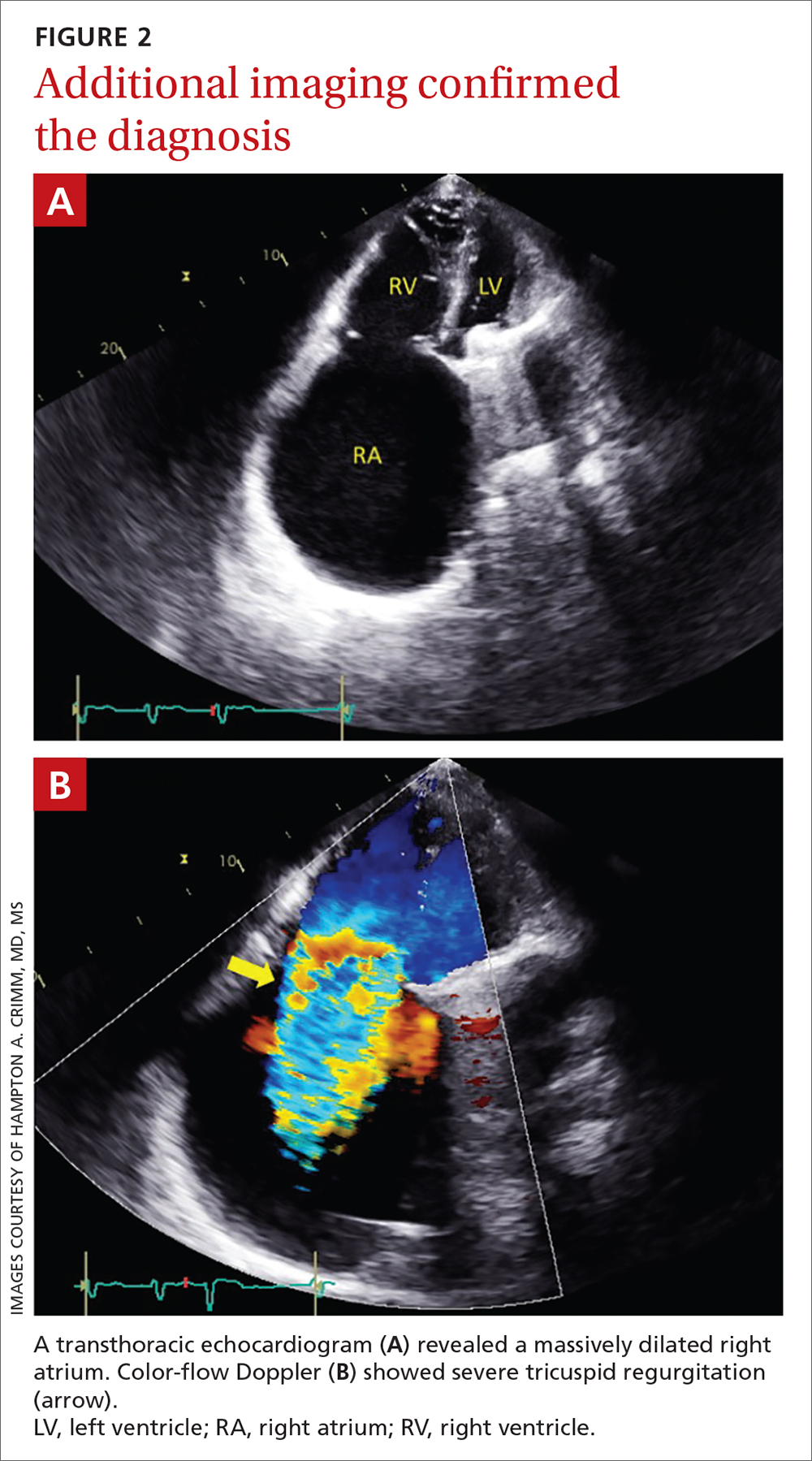

A transthoracic echocardiogram (FIGURE 2A) revealed cardiomegaly with massive right atrial enlargement; a color-flow Doppler (FIGURE 2B) revealed severe tricuspid regurgitation, reduced right ventricular systolic function, and preserved left ventricular systolic function. All of these findings pointed to the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease (RHD), especially in the context of prior mitral valve stenosis.

RHD affects more than 33 million people annually and remains a significant problem globally.1 It’s associated with a relatively poor prognosis, especially if heart failure is present (as it was in this case).2,3 Although the mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected, approximately 34% of patients will develop tricuspid regurgitation.4 Right-side cardiac manifestations of RHD may lead to clinical heart failure with chronic venous congestion and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Suspect RHD when encountering a new murmur in a patient with prior history of acute rheumatic fever, especially if they are living in or are from a country where rheumatic disease is endemic (most of the developing world).

The diagnosis is confirmed when echocardiographic findings demonstrate characteristic pathologic valve changes (eg, thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, especially the leaflet tips and subvalvular apparatus).

The differential for an enlarged cardiac silhouette

The differential diagnosis for an enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR includes cardiomegaly (as in this case), pericardial effusion, or a thoracic mass (either mediastinal or pericardial). Imaging artifact from patient orientation may also yield the appearance of an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Distinguishing between these entities may be accomplished by incorporating the history with selection of more definitive imaging (eg, echocardiogram or computed tomography).

Continue to: Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Percutaneous or surgical intervention may be required with RHD, depending on the clinical scenario. If the patient also has atrial fibrillation, medical management includes oral anticoagulation (with a vitamin K antagonist). Additionally, secondary prophylaxis with long-term antibiotics (directed against recurrent group A Streptococcus infection) is recommended for RHD patients with mitral stenosis.5 If the patient in this case had engaged in more regular cardiology follow-up, the progression of her tricuspid regurgitation may have been mitigated by surgical intervention and aggressive medical management (although the progression of RHD can eclipse standard treatments).5

In this case, a liver biopsy was pursued for prognostication. Unfortunately, the biopsy demonstrated cirrhosis with perisinusoidal fibrosis suggesting an advanced, end-stage clinical state. This diagnosis precluded the patient’s eligibility for advanced therapies such as right ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplantation. Surgical intervention (repair or replacement) was also deemed likely to be futile due to right ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the context of antecedent left-side valve intervention.

The patient elected to pursue palliative care and died at home several months later. In the years since this case occurred, less invasive tricuspid valve interventions have been explored, offering promise of amelioration of such cases in the future.6

1. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et. al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713-722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

2. Zühlke L, Karthikeyan G, Engel ME, et al. Clinical outcomes in 3343 children and adults with rheumatic heart disease from 14 low- and middle-income countries: 2-year follow-up of the global rheumatic heart disease registry (the REMEDY study). Circulation. 2016;134:1456-1466. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

3. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297-309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

4. Sriharibabu M, Himabindu Y, Kabir, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in rural south India: a clinico-observational study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:25-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.011

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:4:e25-e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

6. Fam NP, von Bardeleben RS, Hensey M, et al. Transfemoral transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement with the EVOQUE System: a multicenter, observational, first-in-human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.045

A 63-YEAR-OLD SOUTHEAST ASIAN WOMAN presented with early satiety, mild swelling of her lower extremities, and several months of progressive shortness of breath that had become severe (provoked by activities of daily living). She had a history of longstanding, rate-controlled atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation. She also had a history of mitral valve stenosis that was treated 30 years earlier with mechanical valve replacement. The patient had previously been treated out of state and prior records were not available.

Chest radiography (CXR) was performed as part of the initial work-up (FIGURE 1) and demonstrated a substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette spanning the entire width of the chest without significant pleural effusion or evidence of airspace disease. Suspecting a primary cardiac pathology in this patient, we explored clinical findings of heart failure with transthoracic echocardiography.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Severe tricuspid valve regurgitation secondary to rheumatic heart disease

A transthoracic echocardiogram (FIGURE 2A) revealed cardiomegaly with massive right atrial enlargement; a color-flow Doppler (FIGURE 2B) revealed severe tricuspid regurgitation, reduced right ventricular systolic function, and preserved left ventricular systolic function. All of these findings pointed to the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease (RHD), especially in the context of prior mitral valve stenosis.

RHD affects more than 33 million people annually and remains a significant problem globally.1 It’s associated with a relatively poor prognosis, especially if heart failure is present (as it was in this case).2,3 Although the mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected, approximately 34% of patients will develop tricuspid regurgitation.4 Right-side cardiac manifestations of RHD may lead to clinical heart failure with chronic venous congestion and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Suspect RHD when encountering a new murmur in a patient with prior history of acute rheumatic fever, especially if they are living in or are from a country where rheumatic disease is endemic (most of the developing world).

The diagnosis is confirmed when echocardiographic findings demonstrate characteristic pathologic valve changes (eg, thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, especially the leaflet tips and subvalvular apparatus).

The differential for an enlarged cardiac silhouette

The differential diagnosis for an enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR includes cardiomegaly (as in this case), pericardial effusion, or a thoracic mass (either mediastinal or pericardial). Imaging artifact from patient orientation may also yield the appearance of an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Distinguishing between these entities may be accomplished by incorporating the history with selection of more definitive imaging (eg, echocardiogram or computed tomography).

Continue to: Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Percutaneous or surgical intervention may be required with RHD, depending on the clinical scenario. If the patient also has atrial fibrillation, medical management includes oral anticoagulation (with a vitamin K antagonist). Additionally, secondary prophylaxis with long-term antibiotics (directed against recurrent group A Streptococcus infection) is recommended for RHD patients with mitral stenosis.5 If the patient in this case had engaged in more regular cardiology follow-up, the progression of her tricuspid regurgitation may have been mitigated by surgical intervention and aggressive medical management (although the progression of RHD can eclipse standard treatments).5

In this case, a liver biopsy was pursued for prognostication. Unfortunately, the biopsy demonstrated cirrhosis with perisinusoidal fibrosis suggesting an advanced, end-stage clinical state. This diagnosis precluded the patient’s eligibility for advanced therapies such as right ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplantation. Surgical intervention (repair or replacement) was also deemed likely to be futile due to right ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the context of antecedent left-side valve intervention.

The patient elected to pursue palliative care and died at home several months later. In the years since this case occurred, less invasive tricuspid valve interventions have been explored, offering promise of amelioration of such cases in the future.6

A 63-YEAR-OLD SOUTHEAST ASIAN WOMAN presented with early satiety, mild swelling of her lower extremities, and several months of progressive shortness of breath that had become severe (provoked by activities of daily living). She had a history of longstanding, rate-controlled atrial fibrillation on oral anticoagulation. She also had a history of mitral valve stenosis that was treated 30 years earlier with mechanical valve replacement. The patient had previously been treated out of state and prior records were not available.

Chest radiography (CXR) was performed as part of the initial work-up (FIGURE 1) and demonstrated a substantially enlarged cardiac silhouette spanning the entire width of the chest without significant pleural effusion or evidence of airspace disease. Suspecting a primary cardiac pathology in this patient, we explored clinical findings of heart failure with transthoracic echocardiography.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Severe tricuspid valve regurgitation secondary to rheumatic heart disease

A transthoracic echocardiogram (FIGURE 2A) revealed cardiomegaly with massive right atrial enlargement; a color-flow Doppler (FIGURE 2B) revealed severe tricuspid regurgitation, reduced right ventricular systolic function, and preserved left ventricular systolic function. All of these findings pointed to the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease (RHD), especially in the context of prior mitral valve stenosis.

RHD affects more than 33 million people annually and remains a significant problem globally.1 It’s associated with a relatively poor prognosis, especially if heart failure is present (as it was in this case).2,3 Although the mitral and aortic valves are most commonly affected, approximately 34% of patients will develop tricuspid regurgitation.4 Right-side cardiac manifestations of RHD may lead to clinical heart failure with chronic venous congestion and, ultimately, cirrhosis.

Suspect RHD when encountering a new murmur in a patient with prior history of acute rheumatic fever, especially if they are living in or are from a country where rheumatic disease is endemic (most of the developing world).

The diagnosis is confirmed when echocardiographic findings demonstrate characteristic pathologic valve changes (eg, thickening of the anterior mitral valve leaflet, especially the leaflet tips and subvalvular apparatus).

The differential for an enlarged cardiac silhouette

The differential diagnosis for an enlarged cardiac silhouette on CXR includes cardiomegaly (as in this case), pericardial effusion, or a thoracic mass (either mediastinal or pericardial). Imaging artifact from patient orientation may also yield the appearance of an enlarged cardiac silhouette. Distinguishing between these entities may be accomplished by incorporating the history with selection of more definitive imaging (eg, echocardiogram or computed tomography).

Continue to: Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Management depends on the severity and symptoms

Percutaneous or surgical intervention may be required with RHD, depending on the clinical scenario. If the patient also has atrial fibrillation, medical management includes oral anticoagulation (with a vitamin K antagonist). Additionally, secondary prophylaxis with long-term antibiotics (directed against recurrent group A Streptococcus infection) is recommended for RHD patients with mitral stenosis.5 If the patient in this case had engaged in more regular cardiology follow-up, the progression of her tricuspid regurgitation may have been mitigated by surgical intervention and aggressive medical management (although the progression of RHD can eclipse standard treatments).5

In this case, a liver biopsy was pursued for prognostication. Unfortunately, the biopsy demonstrated cirrhosis with perisinusoidal fibrosis suggesting an advanced, end-stage clinical state. This diagnosis precluded the patient’s eligibility for advanced therapies such as right ventricular assist device implantation or cardiac transplantation. Surgical intervention (repair or replacement) was also deemed likely to be futile due to right ventricular dilatation and systolic dysfunction in the context of antecedent left-side valve intervention.

The patient elected to pursue palliative care and died at home several months later. In the years since this case occurred, less invasive tricuspid valve interventions have been explored, offering promise of amelioration of such cases in the future.6

1. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et. al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713-722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

2. Zühlke L, Karthikeyan G, Engel ME, et al. Clinical outcomes in 3343 children and adults with rheumatic heart disease from 14 low- and middle-income countries: 2-year follow-up of the global rheumatic heart disease registry (the REMEDY study). Circulation. 2016;134:1456-1466. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

3. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297-309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

4. Sriharibabu M, Himabindu Y, Kabir, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in rural south India: a clinico-observational study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:25-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.011

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:4:e25-e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

6. Fam NP, von Bardeleben RS, Hensey M, et al. Transfemoral transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement with the EVOQUE System: a multicenter, observational, first-in-human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.045

1. Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, et. al. Global, regional, and national burden of rheumatic heart disease, 1990-2015. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:713-722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603693

2. Zühlke L, Karthikeyan G, Engel ME, et al. Clinical outcomes in 3343 children and adults with rheumatic heart disease from 14 low- and middle-income countries: 2-year follow-up of the global rheumatic heart disease registry (the REMEDY study). Circulation. 2016;134:1456-1466. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA

3. Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A, et al. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:297-309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7

4. Sriharibabu M, Himabindu Y, Kabir, et al. Rheumatic heart disease in rural south India: a clinico-observational study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;4:25-29. doi: 10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.02.011

5. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:4:e25-e197. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.018

6. Fam NP, von Bardeleben RS, Hensey M, et al. Transfemoral transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement with the EVOQUE System: a multicenter, observational, first-in-human experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:501-511. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.11.045

Does platelet-rich plasma improve patellar tendinopathy symptoms?

Evidence summary

Symptoms improve with PRP—but not significantly

A 2014 double-blind RCT (n = 23) explored recovery outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who received either 1 injection of leukocyte-rich PRP or ultrasound-guided dry needling.1 Both groups also completed standardized eccentric exercises. Participants were predominantly men, ages ≥ 18 years. Symptomatic improvement was assessed using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment–Patella (VISA-P), an 8-item subjective questionnaire of functionality with a range of 0 to 100, with 100 as the maximum score for an asymptomatic individual.

At 12 weeks posttreatment, VISA-P scores improved in both groups. However, the improvement in the dry needling group was not statistically significant (5.2 points; 95% CI, –2.2 to 12.6; P = .20), while in the PRP group it was statistically significant (25.4 points; 95% CI, 10.3 to 40.6; P = .01). At ≥ 26 weeks, statistically significant improvement was observed in both treatment groups: scores improved by 33.2 points (95% CI, 24.1 to 42.4; P = .001) in the dry needling group and by 28.9 points (95% CI, 11.4 to 46.3; P = .01) in the PRP group. However, the difference between the groups’ VISA-P scores at ≥ 26 weeks was not significant (P = .66).1

No significant differences observed for PRP vs placebo or physical therapy

A 2019 single-blind RCT (n = 57) involved patients who were treated with 1 injection of either leukocyte-rich PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP, or saline, all in combination with 6 weeks of physical therapy.2 Participants were predominantly men, ages 18 to 50 years, and engaged in recreational sporting activities. There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in VISA-P score at any timepoint of the 2-year study period. P values were not reported.2

A 2010 RCT (n = 31) compared PRP (unspecified whether leukocyte-rich or -poor) in combination with physical therapy to physical therapy alone.3 Groups were matched for sex, age, and sports activity level; patients in the PRP group were required to have failed previous treatment, while control subjects must not have received any treatment for at least 2 months. Subjects were evaluated pretreatment, immediately posttreatment, and 6 months posttreatment. Clinical evaluation was aided by use of the Tegner activity score, a 1-item score that grades activity level on a scale of 0 to 10; the EuroQol-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which evaluates subjective rating of overall health; and pain level scores.

At 6 months posttreatment, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups in EQ-VAS and pain level scores. However, Tegner activity scores among PRP recipients showed significant percent improvement over controls at 6 months posttreatment (39% vs 20%; P = .048).3

Recommendations from others

Currently, national orthopedic and professional athletic medical associations have recommended that further research be conducted in order to make a strong statement in favor of or against PRP.4,5

Editor’s takeaway

Existing data regarding PRP fails, again, to show consistent benefits. These small sample sizes, inconsistent comparators, and heterogeneous results limit our certainty. This lack of quality evidence does not prove a lack of effect, but it raises serious doubts.

1. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416

2. Scott A, LaPrade R, Harmon K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial of leukocyte-rich PRP or leukocyte-poor PRP versus saline. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1654-1661. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837954

3. Filardo G, Kon E, Villa S Della, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34:909. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7

4. LaPrade R, Dragoo J, Koh J, et al. AAOS Research Symposium updates and consensus: biologic treatment of orthopaedic injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:e62-e78. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00086

5. Rodeo SA, Bedi A. 2019-2020 NFL and NFL Physician Society orthobiologics consensus statement. Sports Health. 2020;12:58-60. doi: 10.1177/1941738119889013

Evidence summary

Symptoms improve with PRP—but not significantly

A 2014 double-blind RCT (n = 23) explored recovery outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who received either 1 injection of leukocyte-rich PRP or ultrasound-guided dry needling.1 Both groups also completed standardized eccentric exercises. Participants were predominantly men, ages ≥ 18 years. Symptomatic improvement was assessed using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment–Patella (VISA-P), an 8-item subjective questionnaire of functionality with a range of 0 to 100, with 100 as the maximum score for an asymptomatic individual.

At 12 weeks posttreatment, VISA-P scores improved in both groups. However, the improvement in the dry needling group was not statistically significant (5.2 points; 95% CI, –2.2 to 12.6; P = .20), while in the PRP group it was statistically significant (25.4 points; 95% CI, 10.3 to 40.6; P = .01). At ≥ 26 weeks, statistically significant improvement was observed in both treatment groups: scores improved by 33.2 points (95% CI, 24.1 to 42.4; P = .001) in the dry needling group and by 28.9 points (95% CI, 11.4 to 46.3; P = .01) in the PRP group. However, the difference between the groups’ VISA-P scores at ≥ 26 weeks was not significant (P = .66).1

No significant differences observed for PRP vs placebo or physical therapy

A 2019 single-blind RCT (n = 57) involved patients who were treated with 1 injection of either leukocyte-rich PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP, or saline, all in combination with 6 weeks of physical therapy.2 Participants were predominantly men, ages 18 to 50 years, and engaged in recreational sporting activities. There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in VISA-P score at any timepoint of the 2-year study period. P values were not reported.2

A 2010 RCT (n = 31) compared PRP (unspecified whether leukocyte-rich or -poor) in combination with physical therapy to physical therapy alone.3 Groups were matched for sex, age, and sports activity level; patients in the PRP group were required to have failed previous treatment, while control subjects must not have received any treatment for at least 2 months. Subjects were evaluated pretreatment, immediately posttreatment, and 6 months posttreatment. Clinical evaluation was aided by use of the Tegner activity score, a 1-item score that grades activity level on a scale of 0 to 10; the EuroQol-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which evaluates subjective rating of overall health; and pain level scores.

At 6 months posttreatment, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups in EQ-VAS and pain level scores. However, Tegner activity scores among PRP recipients showed significant percent improvement over controls at 6 months posttreatment (39% vs 20%; P = .048).3

Recommendations from others

Currently, national orthopedic and professional athletic medical associations have recommended that further research be conducted in order to make a strong statement in favor of or against PRP.4,5

Editor’s takeaway

Existing data regarding PRP fails, again, to show consistent benefits. These small sample sizes, inconsistent comparators, and heterogeneous results limit our certainty. This lack of quality evidence does not prove a lack of effect, but it raises serious doubts.

Evidence summary

Symptoms improve with PRP—but not significantly

A 2014 double-blind RCT (n = 23) explored recovery outcomes in patients with patellar tendinopathy who received either 1 injection of leukocyte-rich PRP or ultrasound-guided dry needling.1 Both groups also completed standardized eccentric exercises. Participants were predominantly men, ages ≥ 18 years. Symptomatic improvement was assessed using the Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment–Patella (VISA-P), an 8-item subjective questionnaire of functionality with a range of 0 to 100, with 100 as the maximum score for an asymptomatic individual.

At 12 weeks posttreatment, VISA-P scores improved in both groups. However, the improvement in the dry needling group was not statistically significant (5.2 points; 95% CI, –2.2 to 12.6; P = .20), while in the PRP group it was statistically significant (25.4 points; 95% CI, 10.3 to 40.6; P = .01). At ≥ 26 weeks, statistically significant improvement was observed in both treatment groups: scores improved by 33.2 points (95% CI, 24.1 to 42.4; P = .001) in the dry needling group and by 28.9 points (95% CI, 11.4 to 46.3; P = .01) in the PRP group. However, the difference between the groups’ VISA-P scores at ≥ 26 weeks was not significant (P = .66).1

No significant differences observed for PRP vs placebo or physical therapy

A 2019 single-blind RCT (n = 57) involved patients who were treated with 1 injection of either leukocyte-rich PRP, leukocyte-poor PRP, or saline, all in combination with 6 weeks of physical therapy.2 Participants were predominantly men, ages 18 to 50 years, and engaged in recreational sporting activities. There was no statistically significant difference in mean change in VISA-P score at any timepoint of the 2-year study period. P values were not reported.2

A 2010 RCT (n = 31) compared PRP (unspecified whether leukocyte-rich or -poor) in combination with physical therapy to physical therapy alone.3 Groups were matched for sex, age, and sports activity level; patients in the PRP group were required to have failed previous treatment, while control subjects must not have received any treatment for at least 2 months. Subjects were evaluated pretreatment, immediately posttreatment, and 6 months posttreatment. Clinical evaluation was aided by use of the Tegner activity score, a 1-item score that grades activity level on a scale of 0 to 10; the EuroQol-visual analog scale (EQ-VAS), which evaluates subjective rating of overall health; and pain level scores.

At 6 months posttreatment, no statistically significant differences were observed between groups in EQ-VAS and pain level scores. However, Tegner activity scores among PRP recipients showed significant percent improvement over controls at 6 months posttreatment (39% vs 20%; P = .048).3

Recommendations from others

Currently, national orthopedic and professional athletic medical associations have recommended that further research be conducted in order to make a strong statement in favor of or against PRP.4,5

Editor’s takeaway

Existing data regarding PRP fails, again, to show consistent benefits. These small sample sizes, inconsistent comparators, and heterogeneous results limit our certainty. This lack of quality evidence does not prove a lack of effect, but it raises serious doubts.

1. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416

2. Scott A, LaPrade R, Harmon K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial of leukocyte-rich PRP or leukocyte-poor PRP versus saline. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1654-1661. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837954

3. Filardo G, Kon E, Villa S Della, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34:909. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7

4. LaPrade R, Dragoo J, Koh J, et al. AAOS Research Symposium updates and consensus: biologic treatment of orthopaedic injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:e62-e78. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00086

5. Rodeo SA, Bedi A. 2019-2020 NFL and NFL Physician Society orthobiologics consensus statement. Sports Health. 2020;12:58-60. doi: 10.1177/1941738119889013

1. Dragoo JL, Wasterlain AS, Braun HJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma as a treatment for patellar tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:610-618. doi: 10.1177/0363546513518416

2. Scott A, LaPrade R, Harmon K, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial of leukocyte-rich PRP or leukocyte-poor PRP versus saline. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1654-1661. doi: 10.1177/0363546519837954

3. Filardo G, Kon E, Villa S Della, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of refractory jumper’s knee. Int Orthop. 2010;34:909. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0845-7

4. LaPrade R, Dragoo J, Koh J, et al. AAOS Research Symposium updates and consensus: biologic treatment of orthopaedic injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24:e62-e78. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-16-00086

5. Rodeo SA, Bedi A. 2019-2020 NFL and NFL Physician Society orthobiologics consensus statement. Sports Health. 2020;12:58-60. doi: 10.1177/1941738119889013

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

IT’S UNCLEAR. High-quality data have not consistently established the effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections to improve symptomatic recovery in patellar tendinopathy, compared to placebo (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on 3 small randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). The 3 small RCTs included only 111 patients, total. One found no evidence of significant improvement with PRP compared to controls. The other 2 studies showed mixed results, with different outcome measures favoring different treatment groups and heterogeneous results depending on follow-up duration.

Relugolix combo eases a long-neglected fibroid symptom: Pain

Combination therapy with relugolix (Orgovyx, Relumina), a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, significantly reduced the pain of uterine fibroids, an undertreated aspect of this disease.

In pooled results from the multicenter randomized placebo-controlled LIBERTY 1 and 2 trials, relugolix combination therapy (CT) with the progestin norethindrone (Aygestin, Camila) markedly decreased both menstrual and nonmenstrual fibroid pain, as well as heavy bleeding and other symptoms of leiomyomas. This hormone-dependent condition occurs in 70%-80% of premenopausal women.

“Historically, studies of uterine fibroids have not asked about pain, so one of strengths of these studies is that they asked women to rate their pain and found a substantial proportion listed pain as a symptom,” lead author Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, director of reproductive endocrinology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

The combination was effective against all categories of leiomyoma symptoms, she said, and adverse events were few.

Bleeding has been the main focus of studies of leiomyoma therapies, while chronic pain has been largely neglected, said James H. Segars Jr., MD, director of the division of reproductive science and women’s health research at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, who was not involved in the studies. Across both of the LIBERTY trials, involving 509 women randomized during the period April 2017 to December 2018, more than half overall (54.4%) met their pain reduction goals in a subpopulation analysis. Pain reduction was a secondary outcome of the trials, with bleeding reduction the primary endpoint. Other fibroid symptoms are abdominal bloating and pressure.

“The consistent and significant reduction in measures of pain with relugolix-CT observed in the LIBERTY program is clinically meaningful, patient-relevant, and together with an improvement of heavy menstrual bleeding and other uterine leiomyoma–associated symptoms, is likely to have a substantial effect on the life of women with symptomatic uterine leiomyomas,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote. Their report was published online in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Dr. Segars concurred. “This study is important because sometimes the only fibroid symptom women have is pain. If we ignore that, we miss a lot of women who have pain but no bleeding.”

The study

The premenopausal participants had a mean age of just over 42 years (range, 18-50) and were enrolled from North and South America, Europe, and Africa. All reported leiomyoma-associated heavy menstrual bleeding of 80 mL or greater per cycle for two cycles, or 160 mL or greater during one cycle.

In both arms, the mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, while menstrual blood loss volume was 245.4 (± 186.4) mL in the relugolix-CT and 207.4 (± 114.3) mL in the placebo group.

Pain was a frequent symptom, with approximately 70% in the intervention group and 74% in the placebo group reporting fibroid pain at baseline.

Women were randomized 1:1:1 to receive:

- Relugolix-CT (relugolix 40 mg, estradiol 1 mg, norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg)

- Delayed relugolix-CT (relugolix 40 mg monotherapy followed by relugolix-CT, each for 12 weeks)

- Placebo, taken orally once daily for 24 weeks

The therapy was well tolerated and adverse events were low.

The subpopulation analysis found that over the study period, the proportion of women achieving minimal to no pain (level 0 to 1) during the last 35 days of treatment was notably higher in the relugolix-CT arm than in the placebo arm: 45.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 36.4%-54.3%) versus 13.9% (95% CI, 8.8%-20.5%) in the placebo group (nominal P = .001).

Moreover, the proportions of women with minimal to no pain during both menstrual days and nonmenstrual days were significantly higher with relugolix-CT: 65.0% (95% CI, 55.6%-73.5%) and 44.6% (95% CI, 32.3%-7.5%), respectively, compared with placebo: 19.3% (95% CI 13.2%–26.7%, nominal P = 001), and 21.6% (95% CI, 12.9%-32.7%, nominal P = 004), respectively.

Studies of relugolix monotherapy in Japanese women with uterine leiomyomas have demonstrated reductions in pain.

“Significantly, this combination therapy allows women to be treated over 2 years and to take the oral tablet themselves, unlike Lupron [leuprolide], which is injected and can only be taken for a couple of months because of bone loss,” Dr. Segars said. And the add-back component of combination therapy prevents the adverse symptoms of a hypoestrogenic state.

“The pain of fibroids is chronic, and the longer treatment allows time for the pain fibers to revert to a normal state,” he explained. “The pain pathways get etched into the nerves and it takes time to revert.”

He noted that the LIBERTY trials showed a slight downward trend in pain continuing after 24 weeks of treatment. Other studies of similar hormonal treatments have shown a reduction in the size of fibroids, which can be as large as a tennis ball.

As in endometriosis, leiomyomas are associated with elevated circulating cytokines and a systemic proinflammatory state. In endometriosis, this milieu is linked to the risk of inflammatory arthritis, fibromyalgia, lupus, and cardiovascular disease, Dr. Segars said. “If we did a deeper dive, we might find the same associations for fibroids.” Apart from chronic depression and fatigue, fibroids are linked to downstream pregnancy complications and poor outcomes such as miscarriage and preterm birth, he said.

“There remains a high unmet need for effective treatments, especially nonsurgical interventions, for women with uterine leiomyomas,” the authors wrote. Dr. Stewart added that “it would be helpful to learn more about how relugolix and other drugs in its class work in fibroids. No category of symptoms has been unresponsive to these medications – they are powerful drugs to help women with uterine fibroids.” She noted that relugolix-CT has already been approved outside the United States for symptoms beyond heavy menstrual bleeding.

Future research should focus on developing a therapy that does not interfere with fertility, Dr. Segars said. “We need a treatment that will allow women to get pregnant on it.”

Myovant Sciences GmbH sponsored LIBERTY 1 and 2 and oversaw all aspects of the studies. Dr. Stewart has provided consulting services to Myovant, Bayer, AbbVie, and ObsEva. She has received royalties from UpToDate and fees from Med Learning Group, Med-IQ, Medscape, Peer View, and PER, as well as honoraria from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Massachusetts Medical Society. She holds a patent for methods and compounds for treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding. Dr. Segars has consulted for Bayer and Organon. Several coauthors reported similar financial relationships with private-sector entities and two coauthors are employees of Myovant.

Combination therapy with relugolix (Orgovyx, Relumina), a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, significantly reduced the pain of uterine fibroids, an undertreated aspect of this disease.

In pooled results from the multicenter randomized placebo-controlled LIBERTY 1 and 2 trials, relugolix combination therapy (CT) with the progestin norethindrone (Aygestin, Camila) markedly decreased both menstrual and nonmenstrual fibroid pain, as well as heavy bleeding and other symptoms of leiomyomas. This hormone-dependent condition occurs in 70%-80% of premenopausal women.

“Historically, studies of uterine fibroids have not asked about pain, so one of strengths of these studies is that they asked women to rate their pain and found a substantial proportion listed pain as a symptom,” lead author Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, director of reproductive endocrinology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

The combination was effective against all categories of leiomyoma symptoms, she said, and adverse events were few.

Bleeding has been the main focus of studies of leiomyoma therapies, while chronic pain has been largely neglected, said James H. Segars Jr., MD, director of the division of reproductive science and women’s health research at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, who was not involved in the studies. Across both of the LIBERTY trials, involving 509 women randomized during the period April 2017 to December 2018, more than half overall (54.4%) met their pain reduction goals in a subpopulation analysis. Pain reduction was a secondary outcome of the trials, with bleeding reduction the primary endpoint. Other fibroid symptoms are abdominal bloating and pressure.

“The consistent and significant reduction in measures of pain with relugolix-CT observed in the LIBERTY program is clinically meaningful, patient-relevant, and together with an improvement of heavy menstrual bleeding and other uterine leiomyoma–associated symptoms, is likely to have a substantial effect on the life of women with symptomatic uterine leiomyomas,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote. Their report was published online in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Dr. Segars concurred. “This study is important because sometimes the only fibroid symptom women have is pain. If we ignore that, we miss a lot of women who have pain but no bleeding.”

The study

The premenopausal participants had a mean age of just over 42 years (range, 18-50) and were enrolled from North and South America, Europe, and Africa. All reported leiomyoma-associated heavy menstrual bleeding of 80 mL or greater per cycle for two cycles, or 160 mL or greater during one cycle.

In both arms, the mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, while menstrual blood loss volume was 245.4 (± 186.4) mL in the relugolix-CT and 207.4 (± 114.3) mL in the placebo group.

Pain was a frequent symptom, with approximately 70% in the intervention group and 74% in the placebo group reporting fibroid pain at baseline.

Women were randomized 1:1:1 to receive:

- Relugolix-CT (relugolix 40 mg, estradiol 1 mg, norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg)

- Delayed relugolix-CT (relugolix 40 mg monotherapy followed by relugolix-CT, each for 12 weeks)

- Placebo, taken orally once daily for 24 weeks

The therapy was well tolerated and adverse events were low.

The subpopulation analysis found that over the study period, the proportion of women achieving minimal to no pain (level 0 to 1) during the last 35 days of treatment was notably higher in the relugolix-CT arm than in the placebo arm: 45.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 36.4%-54.3%) versus 13.9% (95% CI, 8.8%-20.5%) in the placebo group (nominal P = .001).

Moreover, the proportions of women with minimal to no pain during both menstrual days and nonmenstrual days were significantly higher with relugolix-CT: 65.0% (95% CI, 55.6%-73.5%) and 44.6% (95% CI, 32.3%-7.5%), respectively, compared with placebo: 19.3% (95% CI 13.2%–26.7%, nominal P = 001), and 21.6% (95% CI, 12.9%-32.7%, nominal P = 004), respectively.

Studies of relugolix monotherapy in Japanese women with uterine leiomyomas have demonstrated reductions in pain.

“Significantly, this combination therapy allows women to be treated over 2 years and to take the oral tablet themselves, unlike Lupron [leuprolide], which is injected and can only be taken for a couple of months because of bone loss,” Dr. Segars said. And the add-back component of combination therapy prevents the adverse symptoms of a hypoestrogenic state.

“The pain of fibroids is chronic, and the longer treatment allows time for the pain fibers to revert to a normal state,” he explained. “The pain pathways get etched into the nerves and it takes time to revert.”

He noted that the LIBERTY trials showed a slight downward trend in pain continuing after 24 weeks of treatment. Other studies of similar hormonal treatments have shown a reduction in the size of fibroids, which can be as large as a tennis ball.

As in endometriosis, leiomyomas are associated with elevated circulating cytokines and a systemic proinflammatory state. In endometriosis, this milieu is linked to the risk of inflammatory arthritis, fibromyalgia, lupus, and cardiovascular disease, Dr. Segars said. “If we did a deeper dive, we might find the same associations for fibroids.” Apart from chronic depression and fatigue, fibroids are linked to downstream pregnancy complications and poor outcomes such as miscarriage and preterm birth, he said.

“There remains a high unmet need for effective treatments, especially nonsurgical interventions, for women with uterine leiomyomas,” the authors wrote. Dr. Stewart added that “it would be helpful to learn more about how relugolix and other drugs in its class work in fibroids. No category of symptoms has been unresponsive to these medications – they are powerful drugs to help women with uterine fibroids.” She noted that relugolix-CT has already been approved outside the United States for symptoms beyond heavy menstrual bleeding.

Future research should focus on developing a therapy that does not interfere with fertility, Dr. Segars said. “We need a treatment that will allow women to get pregnant on it.”

Myovant Sciences GmbH sponsored LIBERTY 1 and 2 and oversaw all aspects of the studies. Dr. Stewart has provided consulting services to Myovant, Bayer, AbbVie, and ObsEva. She has received royalties from UpToDate and fees from Med Learning Group, Med-IQ, Medscape, Peer View, and PER, as well as honoraria from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Massachusetts Medical Society. She holds a patent for methods and compounds for treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding. Dr. Segars has consulted for Bayer and Organon. Several coauthors reported similar financial relationships with private-sector entities and two coauthors are employees of Myovant.

Combination therapy with relugolix (Orgovyx, Relumina), a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist, significantly reduced the pain of uterine fibroids, an undertreated aspect of this disease.

In pooled results from the multicenter randomized placebo-controlled LIBERTY 1 and 2 trials, relugolix combination therapy (CT) with the progestin norethindrone (Aygestin, Camila) markedly decreased both menstrual and nonmenstrual fibroid pain, as well as heavy bleeding and other symptoms of leiomyomas. This hormone-dependent condition occurs in 70%-80% of premenopausal women.

“Historically, studies of uterine fibroids have not asked about pain, so one of strengths of these studies is that they asked women to rate their pain and found a substantial proportion listed pain as a symptom,” lead author Elizabeth A. Stewart, MD, director of reproductive endocrinology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., said in an interview.

The combination was effective against all categories of leiomyoma symptoms, she said, and adverse events were few.

Bleeding has been the main focus of studies of leiomyoma therapies, while chronic pain has been largely neglected, said James H. Segars Jr., MD, director of the division of reproductive science and women’s health research at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, who was not involved in the studies. Across both of the LIBERTY trials, involving 509 women randomized during the period April 2017 to December 2018, more than half overall (54.4%) met their pain reduction goals in a subpopulation analysis. Pain reduction was a secondary outcome of the trials, with bleeding reduction the primary endpoint. Other fibroid symptoms are abdominal bloating and pressure.

“The consistent and significant reduction in measures of pain with relugolix-CT observed in the LIBERTY program is clinically meaningful, patient-relevant, and together with an improvement of heavy menstrual bleeding and other uterine leiomyoma–associated symptoms, is likely to have a substantial effect on the life of women with symptomatic uterine leiomyomas,” Dr. Stewart and colleagues wrote. Their report was published online in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

Dr. Segars concurred. “This study is important because sometimes the only fibroid symptom women have is pain. If we ignore that, we miss a lot of women who have pain but no bleeding.”

The study

The premenopausal participants had a mean age of just over 42 years (range, 18-50) and were enrolled from North and South America, Europe, and Africa. All reported leiomyoma-associated heavy menstrual bleeding of 80 mL or greater per cycle for two cycles, or 160 mL or greater during one cycle.

In both arms, the mean body mass index was 32 kg/m2, while menstrual blood loss volume was 245.4 (± 186.4) mL in the relugolix-CT and 207.4 (± 114.3) mL in the placebo group.

Pain was a frequent symptom, with approximately 70% in the intervention group and 74% in the placebo group reporting fibroid pain at baseline.

Women were randomized 1:1:1 to receive:

- Relugolix-CT (relugolix 40 mg, estradiol 1 mg, norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg)

- Delayed relugolix-CT (relugolix 40 mg monotherapy followed by relugolix-CT, each for 12 weeks)

- Placebo, taken orally once daily for 24 weeks

The therapy was well tolerated and adverse events were low.

The subpopulation analysis found that over the study period, the proportion of women achieving minimal to no pain (level 0 to 1) during the last 35 days of treatment was notably higher in the relugolix-CT arm than in the placebo arm: 45.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 36.4%-54.3%) versus 13.9% (95% CI, 8.8%-20.5%) in the placebo group (nominal P = .001).

Moreover, the proportions of women with minimal to no pain during both menstrual days and nonmenstrual days were significantly higher with relugolix-CT: 65.0% (95% CI, 55.6%-73.5%) and 44.6% (95% CI, 32.3%-7.5%), respectively, compared with placebo: 19.3% (95% CI 13.2%–26.7%, nominal P = 001), and 21.6% (95% CI, 12.9%-32.7%, nominal P = 004), respectively.

Studies of relugolix monotherapy in Japanese women with uterine leiomyomas have demonstrated reductions in pain.

“Significantly, this combination therapy allows women to be treated over 2 years and to take the oral tablet themselves, unlike Lupron [leuprolide], which is injected and can only be taken for a couple of months because of bone loss,” Dr. Segars said. And the add-back component of combination therapy prevents the adverse symptoms of a hypoestrogenic state.

“The pain of fibroids is chronic, and the longer treatment allows time for the pain fibers to revert to a normal state,” he explained. “The pain pathways get etched into the nerves and it takes time to revert.”

He noted that the LIBERTY trials showed a slight downward trend in pain continuing after 24 weeks of treatment. Other studies of similar hormonal treatments have shown a reduction in the size of fibroids, which can be as large as a tennis ball.

As in endometriosis, leiomyomas are associated with elevated circulating cytokines and a systemic proinflammatory state. In endometriosis, this milieu is linked to the risk of inflammatory arthritis, fibromyalgia, lupus, and cardiovascular disease, Dr. Segars said. “If we did a deeper dive, we might find the same associations for fibroids.” Apart from chronic depression and fatigue, fibroids are linked to downstream pregnancy complications and poor outcomes such as miscarriage and preterm birth, he said.

“There remains a high unmet need for effective treatments, especially nonsurgical interventions, for women with uterine leiomyomas,” the authors wrote. Dr. Stewart added that “it would be helpful to learn more about how relugolix and other drugs in its class work in fibroids. No category of symptoms has been unresponsive to these medications – they are powerful drugs to help women with uterine fibroids.” She noted that relugolix-CT has already been approved outside the United States for symptoms beyond heavy menstrual bleeding.

Future research should focus on developing a therapy that does not interfere with fertility, Dr. Segars said. “We need a treatment that will allow women to get pregnant on it.”

Myovant Sciences GmbH sponsored LIBERTY 1 and 2 and oversaw all aspects of the studies. Dr. Stewart has provided consulting services to Myovant, Bayer, AbbVie, and ObsEva. She has received royalties from UpToDate and fees from Med Learning Group, Med-IQ, Medscape, Peer View, and PER, as well as honoraria from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and Massachusetts Medical Society. She holds a patent for methods and compounds for treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding. Dr. Segars has consulted for Bayer and Organon. Several coauthors reported similar financial relationships with private-sector entities and two coauthors are employees of Myovant.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Twenty years and counting: Tamoxifen’s lasting improvement in breast cancer

The study was a secondary analysis of women with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive HER2-negative breast cancer who were treated between 1976 and 1996 in Sweden.

“Our findings suggest a significant long-term tamoxifen treatment benefit among patients with larger tumors, lymph node-negative tumors, PR-positive tumors, and Ki-67 low tumors,” according to Huma Dar, a doctoral candidate at Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who authored the study.

The analysis found that patients with tumor size T1c, grade 2, lymph node-negative, PR-positive, and Ki-67-low tumors significantly benefited from treatment with tamoxifen for 20 years. And, for patients with tumor size T2-3, benefited significantly after 10 years of treatment with tamoxifen.

It is known that breast cancer patients with ER-positive tumors have a greater risk of distant recurrence – cancer spreading to tissues and organs far from the original tumor site. The selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen, when used as an adjuvant therapy, has been shown to reduce the risk of tumor recurrence and increase survival in patients with ER-positive breast cancer, but not all patients benefit from this therapy.

To examine the long-term benefit of tamoxifen, Ms. Dar and colleagues analyzed data from randomized clinical trials of tamoxifen that took place in Stockholm between 1976 and 1997. The study included 1,242 patients with ER-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer and included a 20-year follow-up. Researchers looked at the relationship between tumor characteristics – including size, grade, lymph node status, the presence of progesterone receptor (PR), and levels of Ki-67, a protein linked with cell proliferation – and patient outcomes.

In a related study published last year in JAMA Network Open, Ms. Dar and colleagues examined the long-term effects of tamoxifen in patients with low risk, postmenopausal, and lymph-node negative cancer. They found that patients with larger tumors, lower tumor grade and PR-positive tumors appeared to significantly benefit from tamoxifen treatment for up to 25 years. The team has since extended that work by looking at pre- and postmenopausal as well as low- and high-risk patients, Ms. Dar said.

“We believe that our findings together with other study findings are important to understand the lifetime risk for patients diagnosed with breast cancer,” Ms. Dar said. “One potential clinical implication is related to tamoxifen benefit, which in our study we don’t see for patients with the smallest tumors.” She said that more studies are needed to confirm this result.

A limitation of this study is that clinical recommendations for disease management and treatment have changed since the initiation of the clinical trials. “The STO-trials were performed before aromatase inhibitors or ovarian function suppression became one of the recommended treatment options for ER-positive breast cancer, and when the duration of tamoxifen therapy was shorter than current recommendations,” Ms. Dar said.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare, The Gösta Milton Donation Fund, and Swedish Cancer Society. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

The study was a secondary analysis of women with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive HER2-negative breast cancer who were treated between 1976 and 1996 in Sweden.

“Our findings suggest a significant long-term tamoxifen treatment benefit among patients with larger tumors, lymph node-negative tumors, PR-positive tumors, and Ki-67 low tumors,” according to Huma Dar, a doctoral candidate at Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who authored the study.

The analysis found that patients with tumor size T1c, grade 2, lymph node-negative, PR-positive, and Ki-67-low tumors significantly benefited from treatment with tamoxifen for 20 years. And, for patients with tumor size T2-3, benefited significantly after 10 years of treatment with tamoxifen.

It is known that breast cancer patients with ER-positive tumors have a greater risk of distant recurrence – cancer spreading to tissues and organs far from the original tumor site. The selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen, when used as an adjuvant therapy, has been shown to reduce the risk of tumor recurrence and increase survival in patients with ER-positive breast cancer, but not all patients benefit from this therapy.

To examine the long-term benefit of tamoxifen, Ms. Dar and colleagues analyzed data from randomized clinical trials of tamoxifen that took place in Stockholm between 1976 and 1997. The study included 1,242 patients with ER-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer and included a 20-year follow-up. Researchers looked at the relationship between tumor characteristics – including size, grade, lymph node status, the presence of progesterone receptor (PR), and levels of Ki-67, a protein linked with cell proliferation – and patient outcomes.

In a related study published last year in JAMA Network Open, Ms. Dar and colleagues examined the long-term effects of tamoxifen in patients with low risk, postmenopausal, and lymph-node negative cancer. They found that patients with larger tumors, lower tumor grade and PR-positive tumors appeared to significantly benefit from tamoxifen treatment for up to 25 years. The team has since extended that work by looking at pre- and postmenopausal as well as low- and high-risk patients, Ms. Dar said.

“We believe that our findings together with other study findings are important to understand the lifetime risk for patients diagnosed with breast cancer,” Ms. Dar said. “One potential clinical implication is related to tamoxifen benefit, which in our study we don’t see for patients with the smallest tumors.” She said that more studies are needed to confirm this result.

A limitation of this study is that clinical recommendations for disease management and treatment have changed since the initiation of the clinical trials. “The STO-trials were performed before aromatase inhibitors or ovarian function suppression became one of the recommended treatment options for ER-positive breast cancer, and when the duration of tamoxifen therapy was shorter than current recommendations,” Ms. Dar said.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare, The Gösta Milton Donation Fund, and Swedish Cancer Society. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

The study was a secondary analysis of women with estrogen receptor (ER)-positive HER2-negative breast cancer who were treated between 1976 and 1996 in Sweden.

“Our findings suggest a significant long-term tamoxifen treatment benefit among patients with larger tumors, lymph node-negative tumors, PR-positive tumors, and Ki-67 low tumors,” according to Huma Dar, a doctoral candidate at Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, who authored the study.

The analysis found that patients with tumor size T1c, grade 2, lymph node-negative, PR-positive, and Ki-67-low tumors significantly benefited from treatment with tamoxifen for 20 years. And, for patients with tumor size T2-3, benefited significantly after 10 years of treatment with tamoxifen.

It is known that breast cancer patients with ER-positive tumors have a greater risk of distant recurrence – cancer spreading to tissues and organs far from the original tumor site. The selective estrogen receptor modulator tamoxifen, when used as an adjuvant therapy, has been shown to reduce the risk of tumor recurrence and increase survival in patients with ER-positive breast cancer, but not all patients benefit from this therapy.

To examine the long-term benefit of tamoxifen, Ms. Dar and colleagues analyzed data from randomized clinical trials of tamoxifen that took place in Stockholm between 1976 and 1997. The study included 1,242 patients with ER-positive/HER2-negative breast cancer and included a 20-year follow-up. Researchers looked at the relationship between tumor characteristics – including size, grade, lymph node status, the presence of progesterone receptor (PR), and levels of Ki-67, a protein linked with cell proliferation – and patient outcomes.

In a related study published last year in JAMA Network Open, Ms. Dar and colleagues examined the long-term effects of tamoxifen in patients with low risk, postmenopausal, and lymph-node negative cancer. They found that patients with larger tumors, lower tumor grade and PR-positive tumors appeared to significantly benefit from tamoxifen treatment for up to 25 years. The team has since extended that work by looking at pre- and postmenopausal as well as low- and high-risk patients, Ms. Dar said.

“We believe that our findings together with other study findings are important to understand the lifetime risk for patients diagnosed with breast cancer,” Ms. Dar said. “One potential clinical implication is related to tamoxifen benefit, which in our study we don’t see for patients with the smallest tumors.” She said that more studies are needed to confirm this result.

A limitation of this study is that clinical recommendations for disease management and treatment have changed since the initiation of the clinical trials. “The STO-trials were performed before aromatase inhibitors or ovarian function suppression became one of the recommended treatment options for ER-positive breast cancer, and when the duration of tamoxifen therapy was shorter than current recommendations,” Ms. Dar said.

The study was funded by the Swedish Research Council, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare, The Gösta Milton Donation Fund, and Swedish Cancer Society. The authors had no relevant disclosures.

FROM ESMO 2022

Unique residency track focuses on rural placement of graduates

BOSTON – As a former active-duty cavalry officer in the U.S. Army who served a 15-month tour in Iraq in 2003, Adam C. Byrd, MD, isn’t easily rattled.

On any given day, as the only dermatologist in his hometown of Louisville, Miss., which has a population of about 6,500, he sees 35-40 patients who present with conditions ranging from an infantile hemangioma to dermatomyositis and porphyria cutanea tarda. Being the go-to specialist for hundreds of miles with no on-site lab and no immediate personal access to Mohs surgeons and other subspecialists might unnerve some dermatologists, but not him.

“They’re a text message away, but they’re not in my office,” he said during a session on rural dermatology at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. “I don’t have a mid-level practitioner, either. It’s just me and the residents, so it can be somewhat isolating. But in a rural area, you’re doing your patients a disservice if you can’t handle broad-spectrum medical dermatology. I consider myself a family dermatologist; I do a little bit of everything.” This includes prescribing treatments ranging from methotrexate for psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, eczema, and other conditions; cyclosporine and azathioprine for pediatric eczema; propranolol for infantile hemangiomas; to IV infusions for dermatomyositis; phlebotomy for porphyria cutanea tarda; and biologics.

With no on-site pathology lab, Dr. Byrd sends specimens twice a week to the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson via FedEx to be read. “I have to wait 3 days for results instead of 2,” he said. At the end of each workday, he personally carries microbiology samples to Winston Medical Center in Louisville – the area’s only hospital and where he was born – for processing.

After completing a 5-year integrated internal medicine-dermatology residency at the University of Minnesota in 2016, Dr. Byrd worked with Robert T. Brodell, MD, who chairs the department of dermatology at UMMC, and other university officials to open a satellite clinic in Louisville, where he provides full-spectrum skin care for Northern Mississippians. The clinic, located about 95 miles from UMMC’s “mothership” in Jackson, has become a vital training ground for the university, which created the only rural-specific dermatology residency of the 142 accredited dermatology programs in the United States. Of the three to four residents accepted per year, one is a rural track resident who spends 3-month–long rotations at rural clinic sites such as Dr. Byrd’s during each of the 3 years of general dermatology training, and the remaining 9 months of each year alongside their non–rural track coresidents.

One of the program’s rural track residents, Joshua R. Ortego, MD, worked in Dr. Byrd’s clinic during PGY-2. “It’s unique for one attending and one resident to work together for 3 months straight,” said Dr. Ortego, who grew up in Bay St. Louis on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi, which has a population of about 9,200. “Dr. Byrd learns our weaknesses and knows our strengths and areas for improvement. You get close. And there’s continuity; you see some patients back. With all the shuffling in the traditional dermatology residency model, sometimes you’re not seeing patients for follow-up appointments. But here you do.”

Rural dermatology track residents who rotate through Dr. Byrd’s Louisville clinic spend each Monday at the main campus in Jackson for a continuity clinic and didactics with non–rural track residents, “which allows for collegiality,” Dr. Ortego said. “My coresidents are like family; it would be hard to spend 3 months or even a year away from family like that.” The department foots the cost of lodging in a Louisville hotel 4 nights per week during these 3 months of training.

Dr. Ortego said that he performed a far greater number of procedures during PGY-2, compared with the averages performed in UMMC’s general dermatology rotation: 75 excisions (vs. 17), 71 repairs (vs. 15), and 23 excisions on the face or scalp (vs. none). He also cared for patients who presented with advanced disease because of access issues, and others with rare conditions. For example, in one afternoon clinic he and Dr. Byrd saw two patients with porphyria cutanea tarda, and one case each of dermatomyositis, bullous pemphigoid, and pyoderma gangrenosum. “We have an autoimmune blistering disease clinic in Jackson, but patients don’t want to drive there,” he said.

Then there are the perks that come with practicing in a rural area, including ready access to hiking, fishing, hunting, and spending time with family and friends. “Rural residents should be comfortable with the lifestyle,” he said. “Some cities don’t have the same amenities as San Francisco or Boston, but not everyone requires that. They just love where they’re from.”

The residency’s structure is designed to address the dire shortage of rural-based dermatologists in the United States. A study published in 2018 found that the difference in dermatologist density between metropolitan and rural counties in the United States increased from 3.41 per 100,000 people (3.47 vs. 0.065 per 100,000 people) in 1995 to 4.03 per 100, 000 people (4.11 vs. 0.085 per 100,000 people in 2013; P = .053). That’s about 40 times the number of dermatologists in metro areas, compared with rural areas.

Residents enrolled in UMMC’s rural dermatology track are expected to serve at least 3 years at a rural location upon graduation at a site mutually agreed upon by the resident and the UMMC. Dr. Ortego plans to practice in Bay St. Louis after completing his residency. “The idea is that you’re happy, that you’re in your hometown,” he said.

According to Dr. Byrd, the 3-year commitment brings job security to rural track residents in their preferred location while meeting the demands of an underserved population. “We are still tweaking this,” he said of the residency track, which includes plans to establish more satellite clinics in other areas of rural Mississippi. “Our department chair does not have 100% control over hiring and office expansion. We are subject to the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning, which is a branch of the state government. This has to be addressed at the council of chairs and university chancellor level and even state government. It can be done, but you really must be dedicated.”

Meanwhile, the effect that dermatologists like Dr. Byrd have on citizens of his area of rural Mississippi is palpable. Many refuse to travel outside of Louisville city limits to see a specialist, so when surgery for a suspicious lesion is indicated, they tell him, “You’re going to do it, or it’s not going to get done,” said Dr. Byrd, who continues to serve in the Mississippi Army National Guard as a field surgeon. “I don’t say ‘no’ a whole lot.” He refers patients to Mohs micrographic surgery colleagues in Jackson daily and is transparent with patients who hesitate to elect Mohs surgery. “I’ll say, ‘I can do the job, but there’s a higher risk of positive margins, and a Mohs surgeon could do a much better job.’”

He acknowledged that rural dermatology “isn’t for everyone. It requires a physician that has a good training foundation in medical and surgical dermatology, someone with a ‘can do’ attitude and a healthy level of confidence. I try to do the best for my patients. It’s endearing when they trust you.”