User login

Easing dementia caregiver burden, addressing interpersonal violence

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

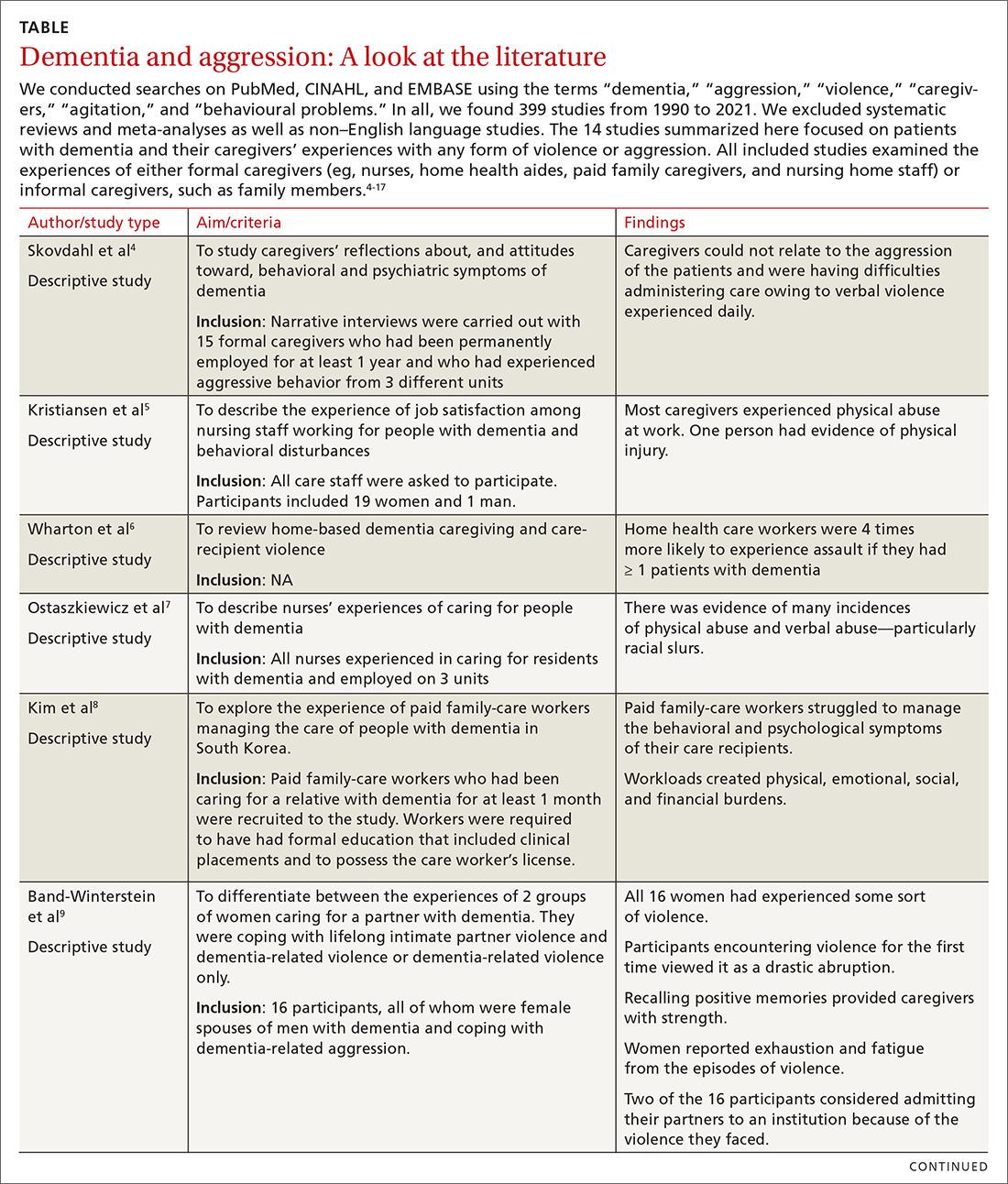

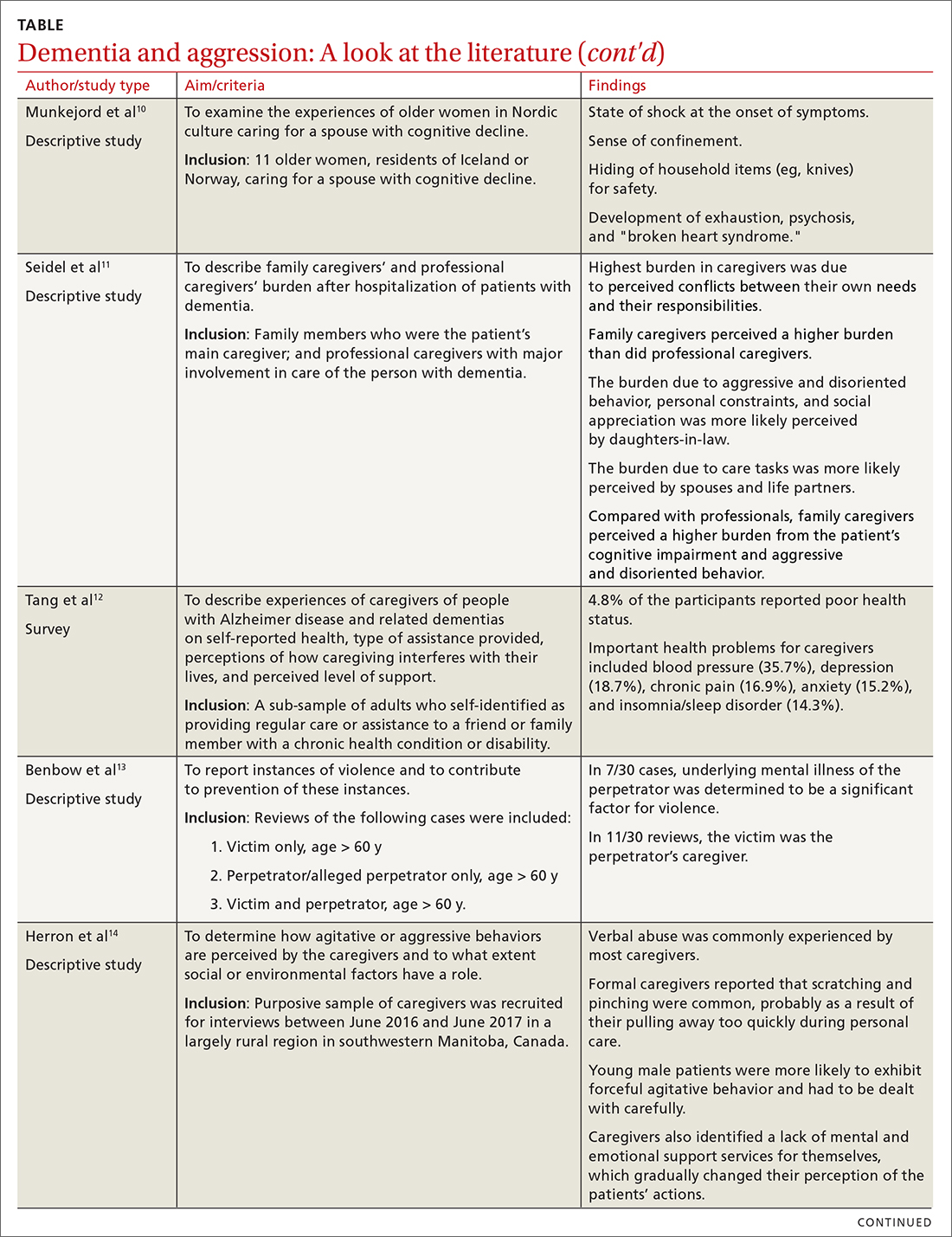

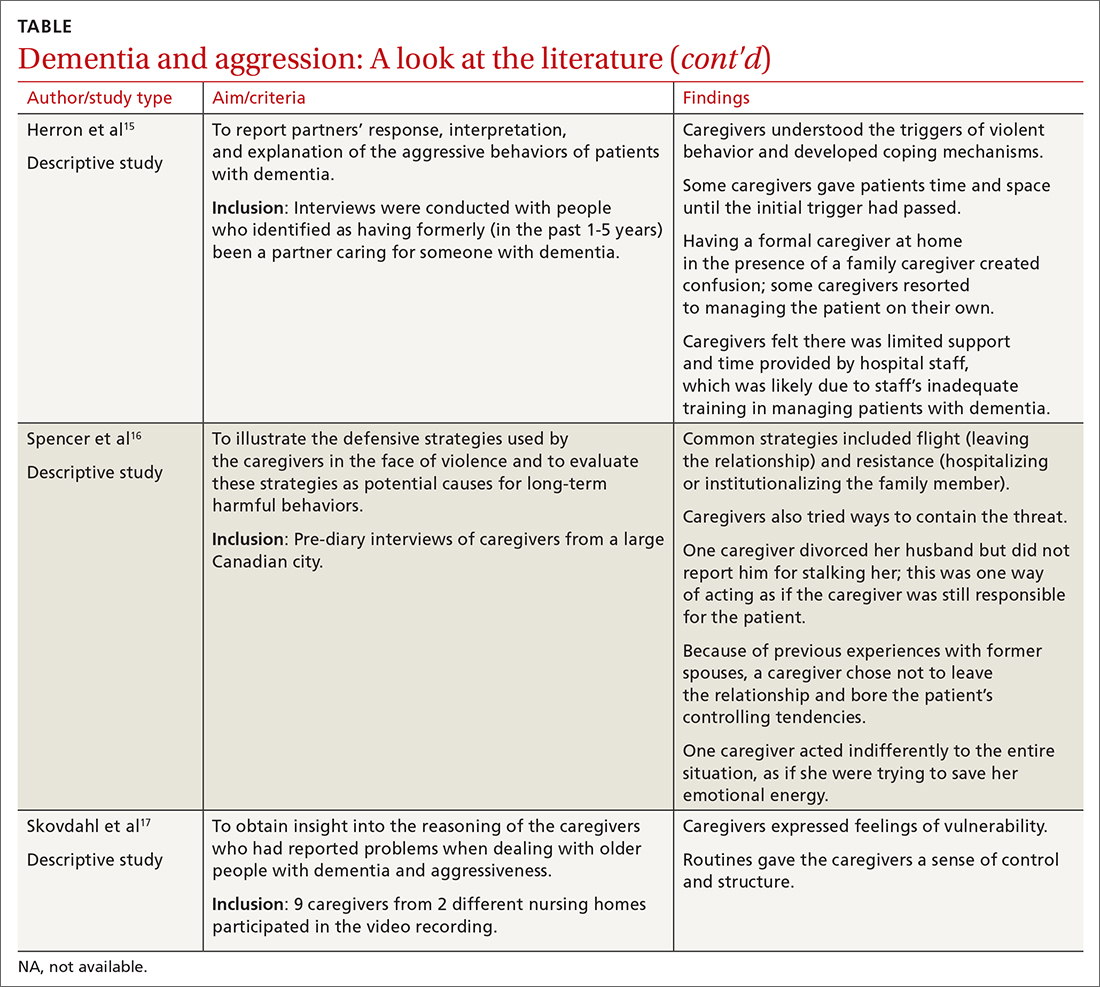

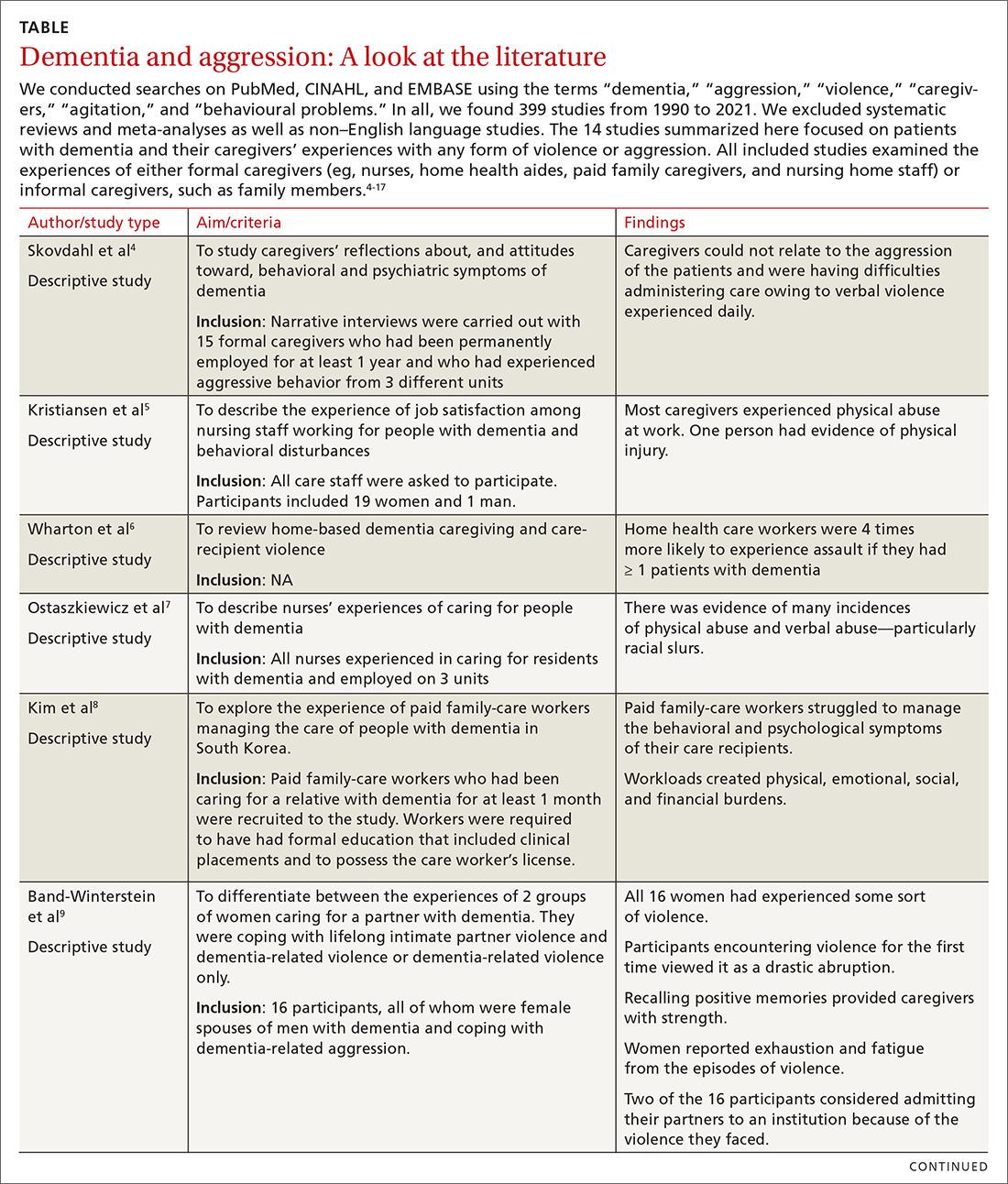

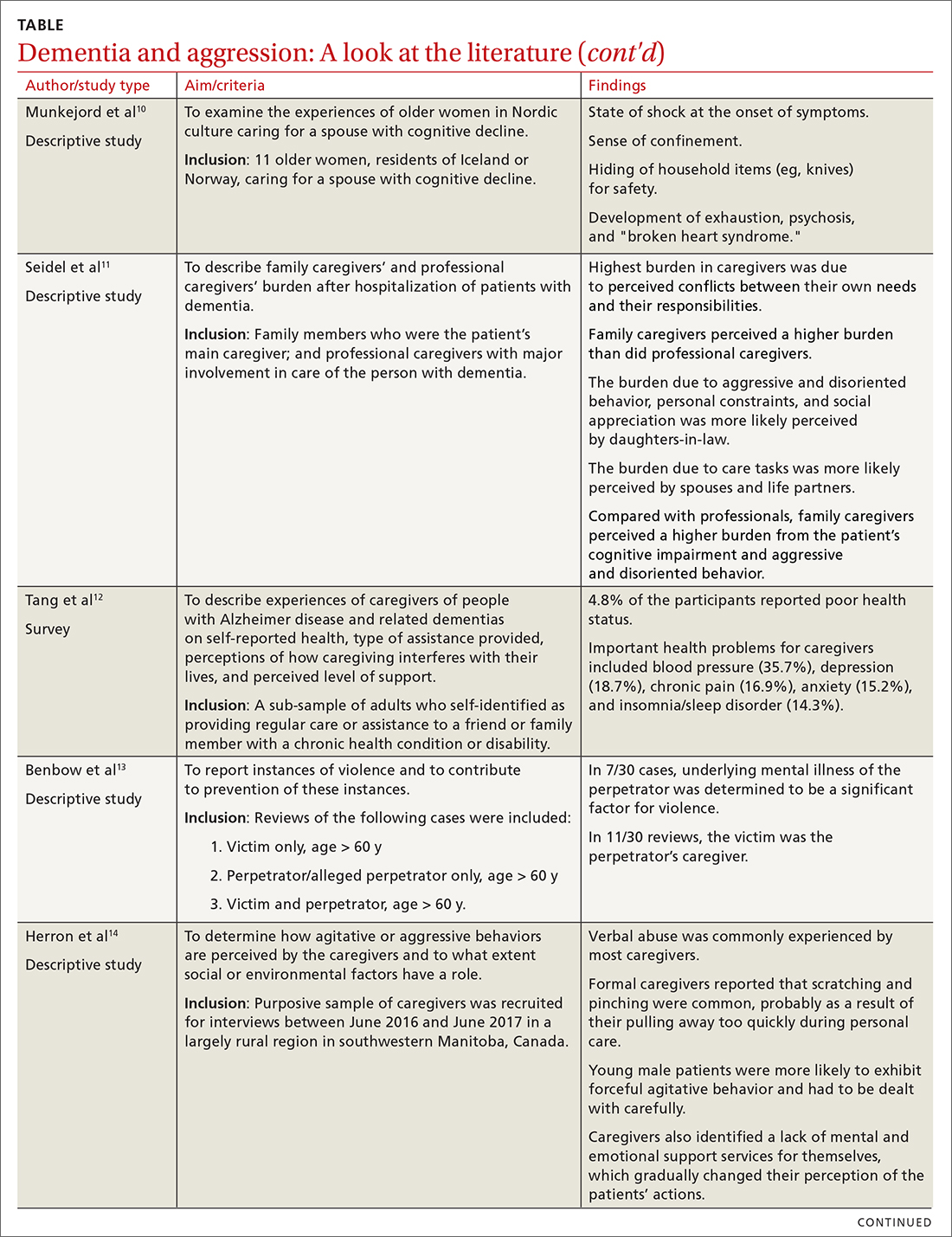

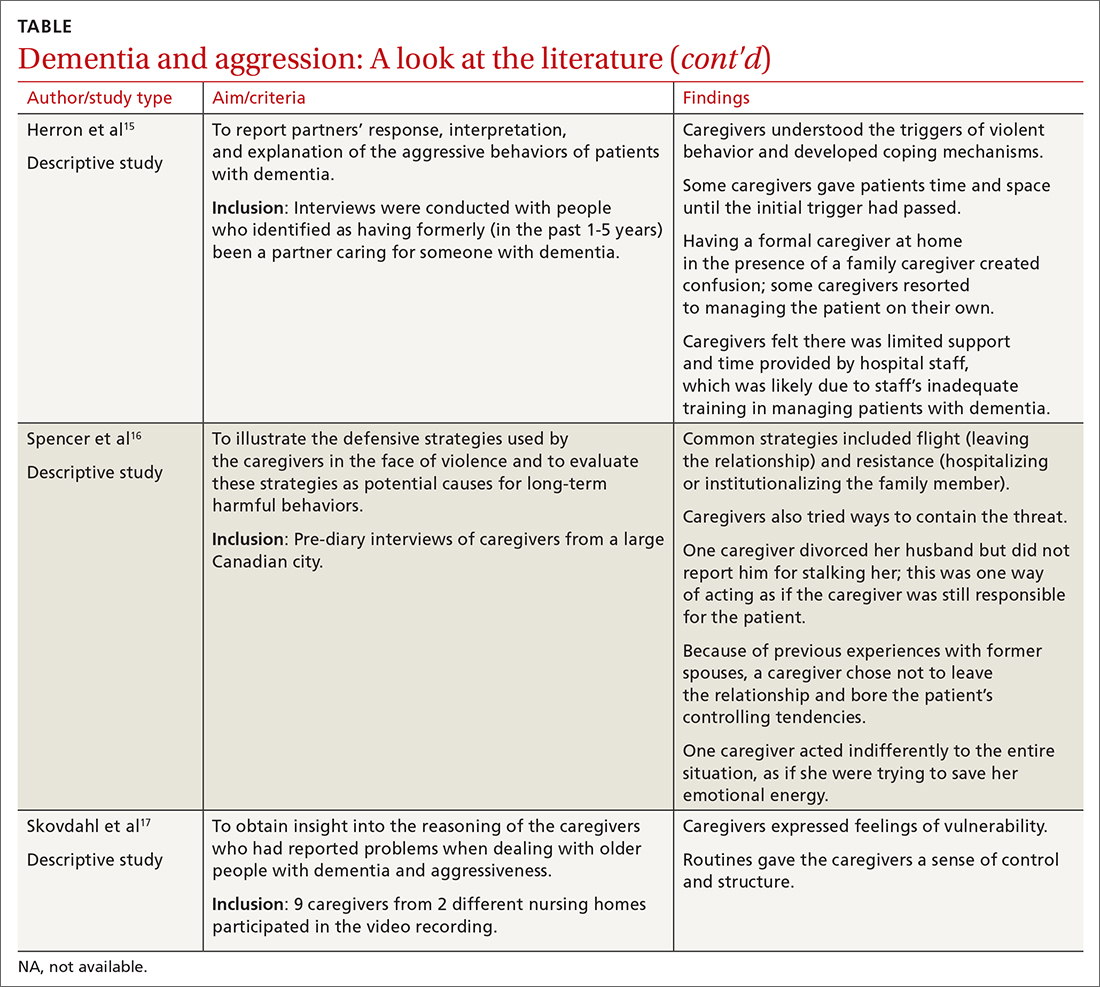

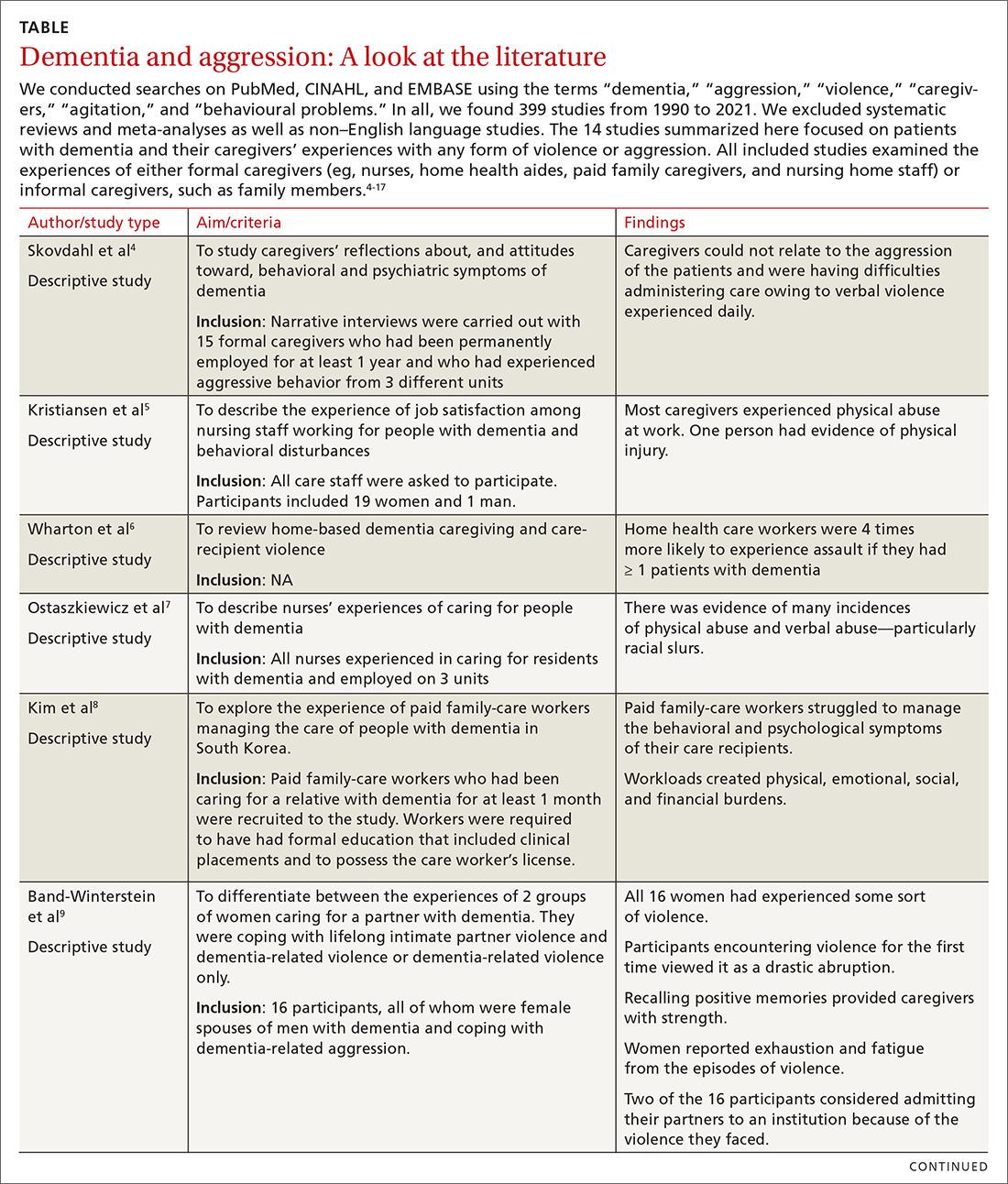

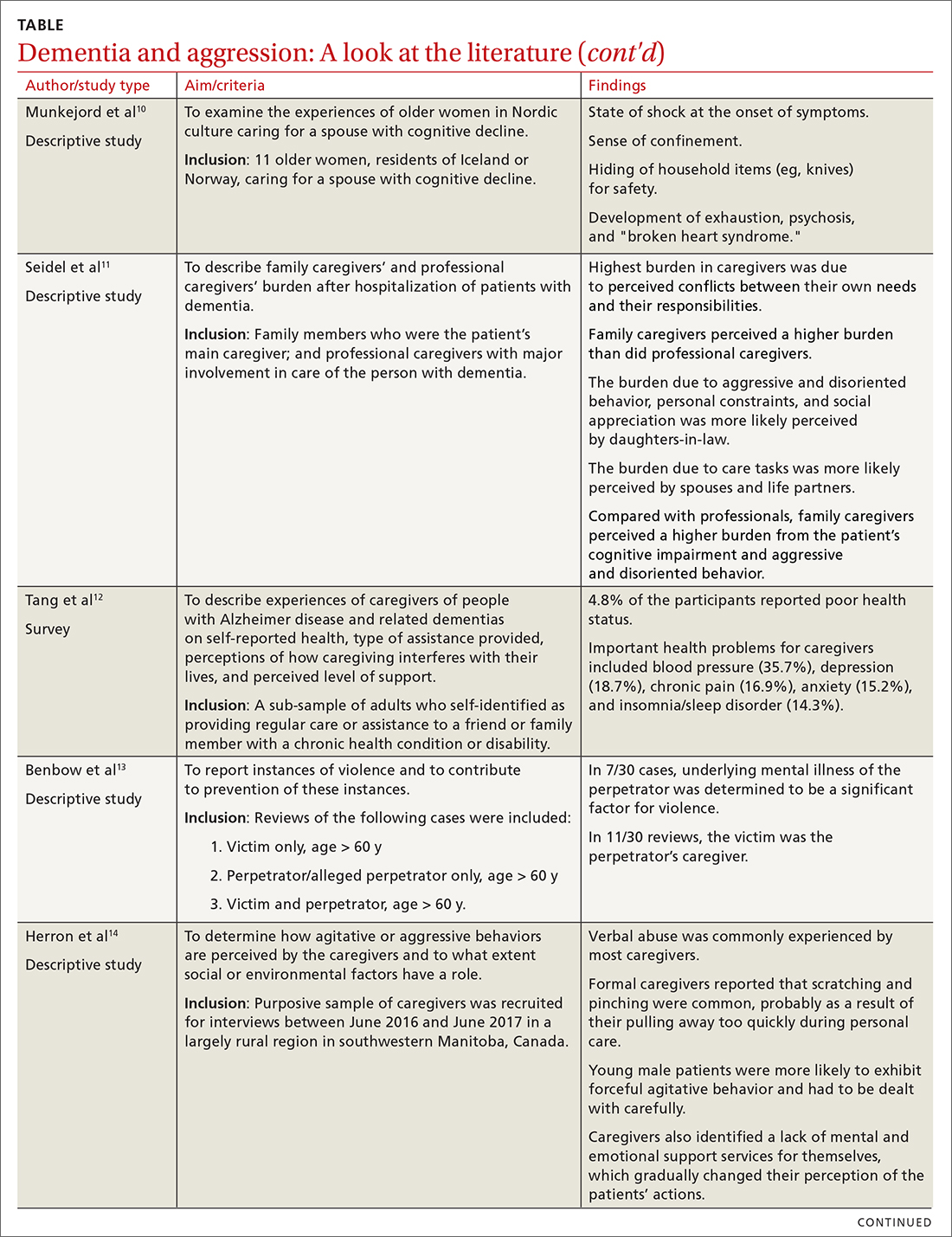

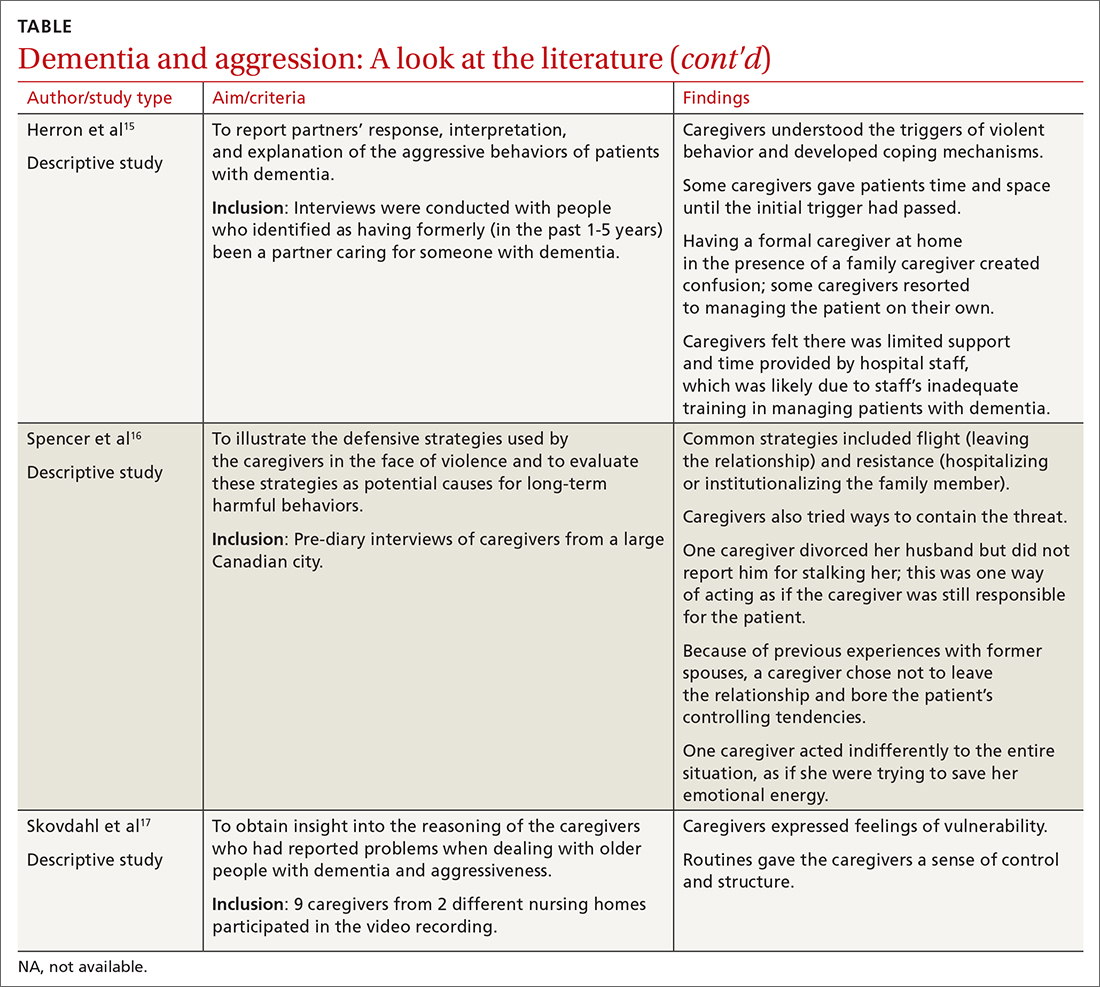

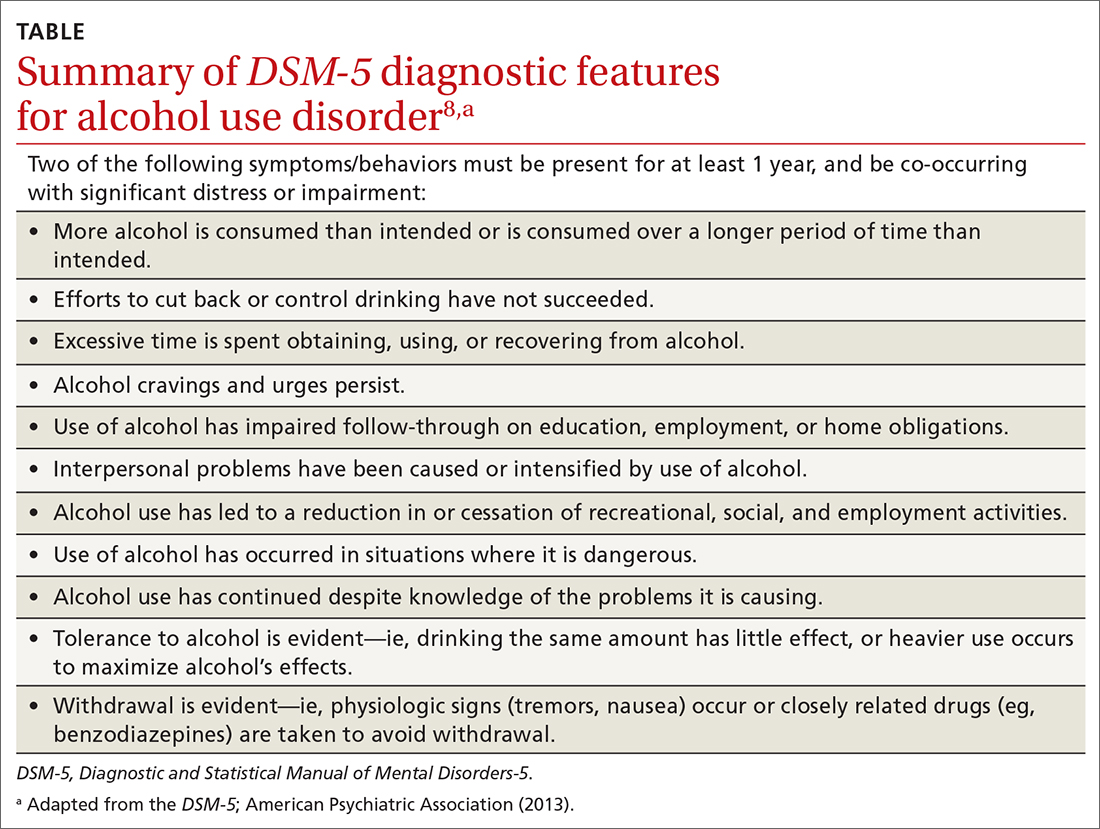

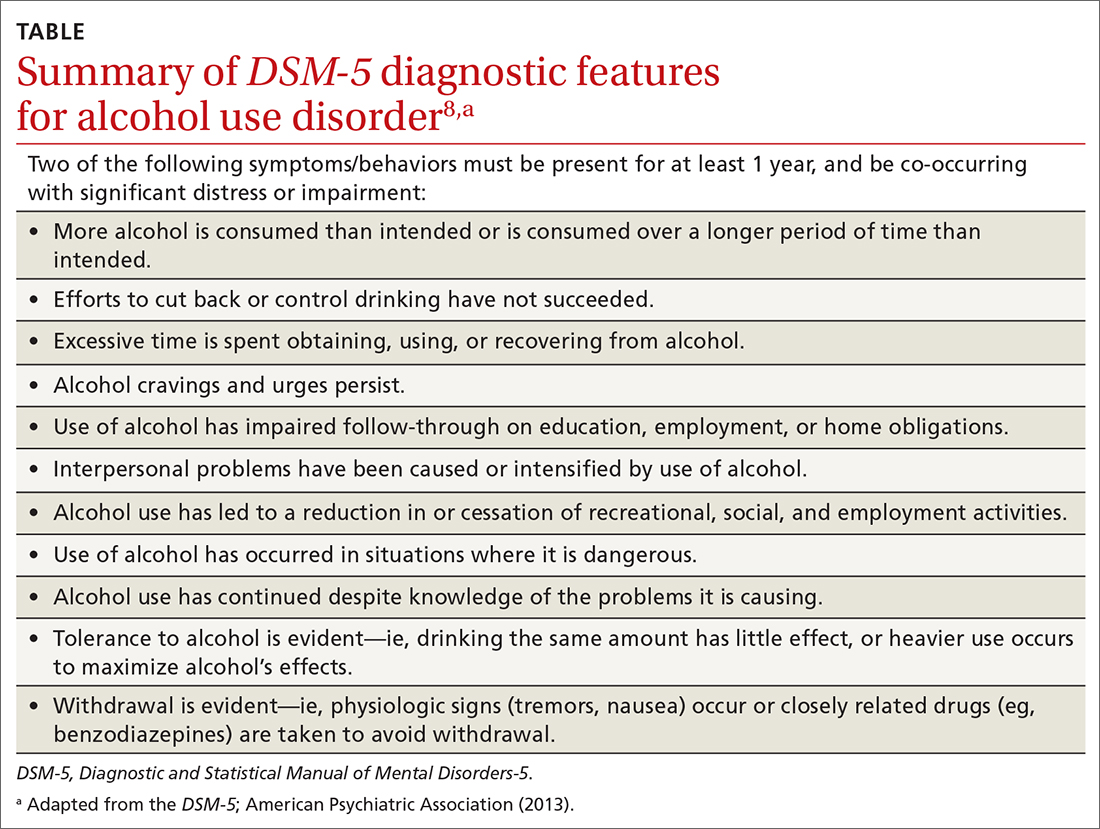

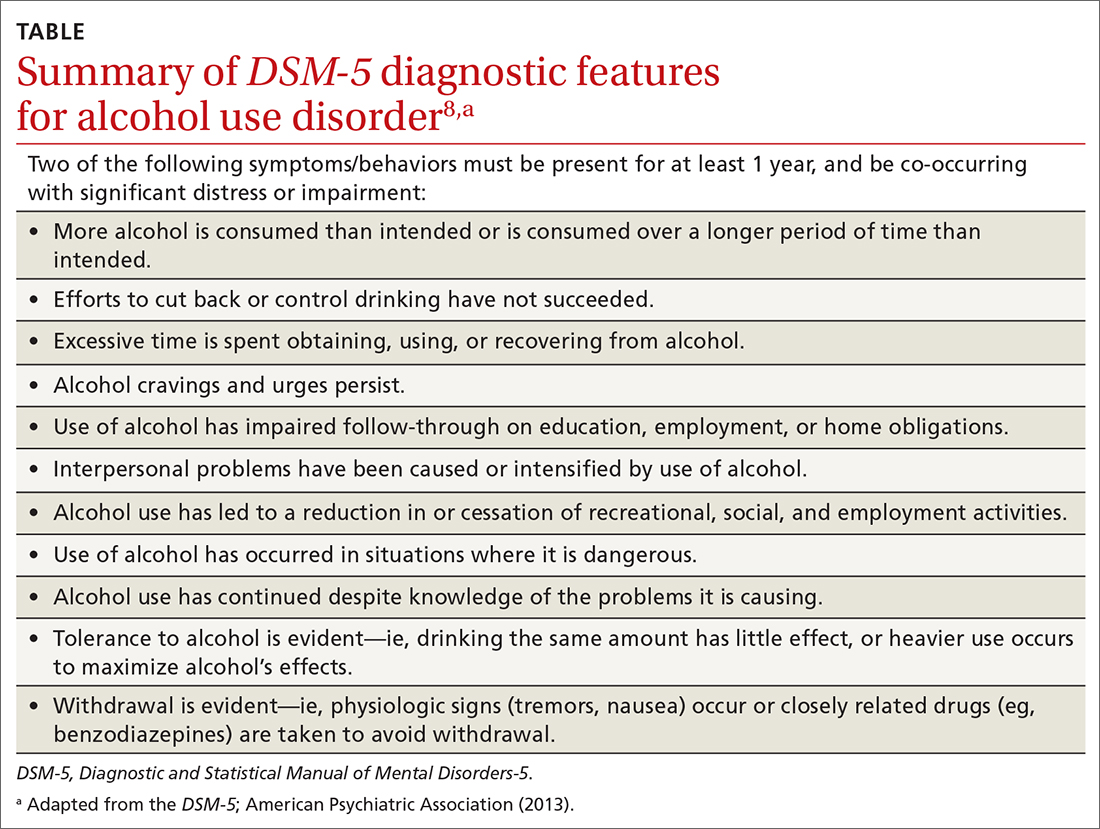

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

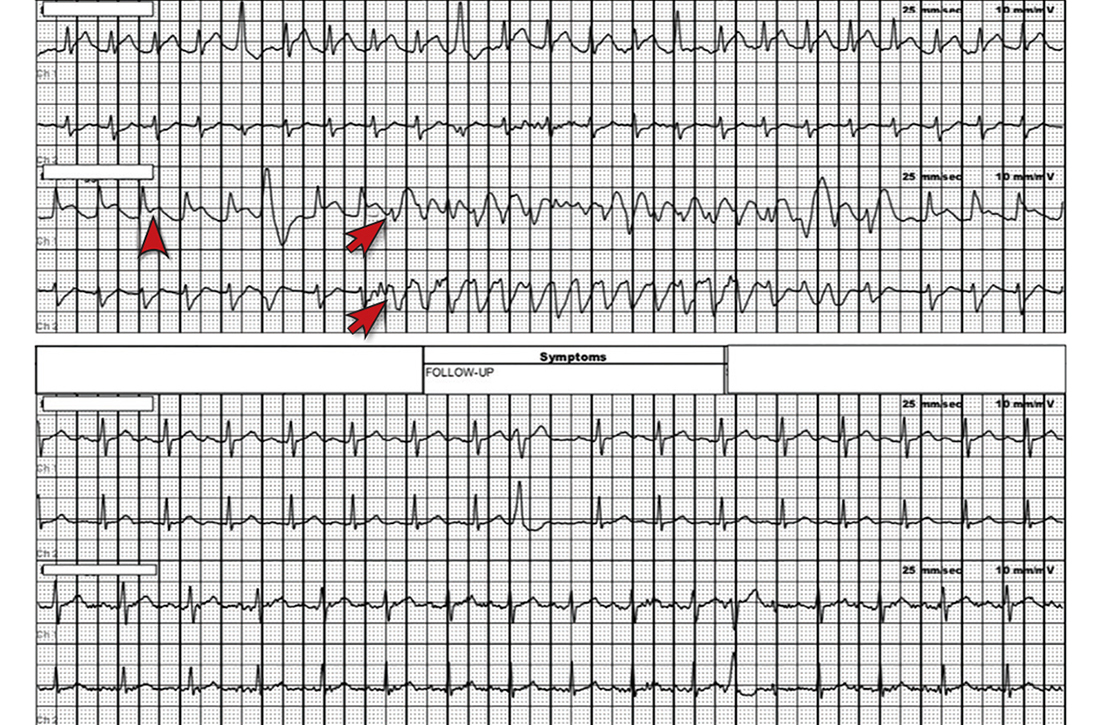

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; [email protected].

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; [email protected].

The number of people with dementia globally is expected to reach 74.7 million by 2030 and 131.5 million by 2050.1 Because dementia is progressive, many patients will exhibit severe symptoms termed behavioral crises. Deteriorating interpersonal conduct and escalating antisocial acts result in an acquired sociopathy.2 Increasing cognitive impairment causes these patients to misunderstand intimate care and perceive it as a threat, often resulting in outbursts of violence against their caregivers.3

Available studies (TABLE4-17) make evident the incidence of interpersonal violence experienced by caregivers secondary to aggressive acts by patients with dementia. This violence ranges from verbal abuse, including racial slurs, to physical abuse—sometimes resulting in significant physical injury. Aggressive behavior by patients with dementia, resulting in violence towards their caregivers or partners, stems from progressive cognitive decline, which can make optimal care difficult. Such episodes may also impair the psychological and physical well-being of caregivers, increasing their risk of depression, anxiety, and even post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).18 The extent of the impact is also determined by the interpretation of the abuse by the caregivers themselves. One study suggested that the perception of aggressive or violent behavior as “normal” by a caregiver reduced the overall negative effect of the interactions.7Our review emphasizes the unintended burden that can fall to caregivers of patients with dementia. We also address the role of primary care providers (PCPs) in identifying these instances of violence and intervening appropriately by providing safety strategies, education, resources, and support.

CASE

A 67-year-old man with a medical history of PTSD with depression, type 2 diabetes, alcohol use disorder/dependence, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea was brought to his PCP by his wife. She said he had recently been unable to keep appointment times, pay bills, or take his usual medications, venlafaxine and bupropion. She also said his PTSD symptoms had worsened. He was sleeping 12 to 14 hours per day and was increasingly irritable. The patient denied any concerns or changes in his behavior.

The PCP administered a Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination to screen for cognitive impairment.19 The patient scored 14/30 (less than 20 is indicative of dementia). He was unable to complete a simple math problem, recall any items from a list of 5, count in reverse, draw a clock correctly, or recall a full story. Throughout the exam, the patient demonstrated minimal effort and was often only able to complete a task after further prompting by the examiner.

A computed tomography scan of the head revealed no signs of hemorrhage or damage. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels and vitamin B12 levels were normal. A rapid plasma reagin test result was negative. The patient was given a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Donepezil was added to the patient’s medications, starting at 5 mg and then increased to 10 mg. His wife began to assist him with his tasks of daily living. His mood improved, and his wife noted he began to remember his appointments and take his medications with assistance.

However, the patient’s irritability continued to escalate. He grew paranoid and accused his wife of mismanaging their money. This pattern steadily worsened over the course of 6 months. The situation escalated until one day the patient’s wife called a mental health hotline reporting that her husband was holding her hostage and threatening to kill her with a gun. He told her, “I can do something to you, and they won’t even find a fingernail. It doesn’t have to be with a gun either.” She was counseled to try to stay calm to avoid aggravating the situation and to go to a safe place and stay there until help arrived.

His memory had worsened to the point that he could not recall any events from the previous 2 years. He was paranoid about anyone entering his home and would not allow his deteriorating roof to be repaired or his yard to be maintained. He did not shower for weeks at a time. He slept holding a rifle and accused his wife of embezzlement.

Continue to: The patient was evaluated...

The patient was evaluated by another specialist, who assessed his SLUMS score to be 18/30. He increased the patient’s donepezil dose, initiated a bupropion taper, and added sertraline to the regimen. The PCP spoke to the patient’s wife regarding options for her safety including leaving the home, hiding firearms, and calling the police in cases of interpersonal violence. The wife said she did not want to pursue these options. She expressed worry that he might be harmed if he was uncooperative with the police and said there was no one except her to take care of him.

Caregivers struggle to care for their loved ones

Instances of personal violence lead to shock, astonishment, heartbreak, and fear. Anticipation of a recurrence of violence causes many partners and caregivers to feel exhausted, because there is minimal hope for any chance of improvement. There are a few exceptions, however, as our case will show. In addition to emotional exhaustion, there is also a never-ending sense of self-doubt, leading many caregivers to question their ability to handle their family member.20,21 Over time, this leads to caregiver burnout, leaving them unable to understand their family member’s aggression. The sudden loss of caregiver control in dealing with the patient may also result in the family member exhibiting behavioral changes reflecting emotional trauma. For caregivers who do not live with the patient, they may choose to make fewer or shorter visits—or not visit at all—because they fear being abused.7,22

Caregivers of patients with dementia often feel helpless and powerless once abrupt and drastic changes in personality lead to some form of interpersonal violence. Additionally, caregivers with a poor health status are more likely to have lower physical function and experience greater caregiving stress overall.23 Other factors increasing stress are longer years of caregiving and the severity of a patient’s dementia and functional impairment.23

Interventions to reduce caregiver burden

Many studies have assessed the role of different interventions to reduce caregiver burden, such as teaching them problem-solving skills, increasing their knowledge of dementia, recommending social resources, providing emotional support, changing caregiver perceptions of the care situation, introducing coping strategies, relying on strengths and experiences in caregiving, help-seeking, and engaging in activity programs.24-28 For Hispanic caregivers, a structured and self-paced online telenovela format has been effective in improving care and relieving caregiver stress.29 Online positive emotion regulators helped in significantly improving quality of life and physical health in the caregivers.30 In this last intervention, caregivers had 6 online sessions with a facilitator who taught them emotional regulation skills that included: noticing positive events, capitalizing on them, and feeling gratitude; practicing mindfulness; doing a positive reappraisal; acknowledging personal strengths and setting attainable goals; and performing acts of kindness. Empowerment programs have also shown significant improvement in the well-being of caregivers.31

Caregivers may reject support.

Continue to: These practical tips can help

These practical tips can help

Based on our review of the literature, we recommend offering the following supports to caregivers:

- Counsel caregivers early on in a patient’s dementia that behavior changes are likely and may be unpredictable. Explain that dementia can involve changes to personality and behavior as well as memory difficulties.33,34

- Describe resources for support, such as day programs for senior adults, insurance coverage for caregiver respite programs, and the Alzheimer’s Association (www.alz.org/). Encourage caregivers to seek general medical and mental health care for themselves. Caregivers should have opportunities and support to discuss their experiences and to be appropriately trained for the challenge of caring for a family member with dementia.35

- Encourage disclosure about abrupt changes in the patient’s behavior. This invites families to discuss issues with you and may make them more comfortable with such conversations.

- Involve ancillary services (eg, social worker) to plan for a higher level of care well in advance of it becoming necessary.

- Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter a patient’s set routines such as bedtimes and mealtimes.33,34

- Discuss when and how to involve law enforcement, if necessary.33,34 Emphasize the importance of removing firearms from the home as a safety measure. Although federal laws do not explicitly prohibit possession of arms by patients with neurologic damage, a few states mention “organic brain syndrome” or “dementia” as conditions prohibiting use or possession of firearms.36

- Suggest, as feasible, nonpharmacologic aids for the patient such as massage therapy, animal-assisted therapy, personalized interventions, music therapy, and light therapy.37 Prescribe medications to the patient to aid in behavior modification when appropriate.

- Screen caregivers and family members for signs of interpersonal violence. Take notice of changes in caregiver behavior or irregularity in attending follow-up appointments.

CASE

Over the next month, the patient’s symptoms further deteriorated. His PCP recommended hospitalization, but the patient and his wife declined. Magnetic resonance imaging of the patient’s brain revealed severe confluent and patchy regions of white matter and T2 signal hyperintensity, consistent with chronic microvascular ischemic disease. An old, small, left parietal lobe infarct was also noted.

One month later, the patient presented to the emergency department. His symptoms were largely unchanged, but his wife indicated that she could no longer live at home due to burnout. The patient’s medications were adjusted, but he was not admitted for inpatient care. His wife said they needed help at home, but the patient opposed the idea any time that it was mentioned.

A few weeks later, the patient presented for outpatient follow-up. He was delusional, believing that the government was compelling citizens to take sertraline in order to harm their mental health. He had also begun viewing online pornography in front of his wife and attempting to remove all of his money from the bank. He was prescribed aripiprazole 15 mg, and his symptoms began to improve. Soon after, however, he threatened to kill his grandson, then took all his Lasix pills (a 7-day supply) simultaneously. The patient denied that this was a suicide attempt.

Over the course of the next month, the patient began to report hearing voices. A neuropsychological evaluation confirmed a diagnosis of dementia with psychiatric symptoms due to neurologic injury. The patient was referred to a geriatric psychiatrist and continued to be managed medically. He was assigned a multidisciplinary team comprising palliative care, social work, and care management to assist in his care and provide support to the family. His behavior improved.

Continue to: At the time of this publication...

At the time of this publication, the patient’s irritability and paranoia had subsided and he had made no further threats to his family. He has allowed a home health aide into the house and has agreed to have his roof repaired. His wife still lives with him and assists him with activities of daily living.

Interprofessional teams are key

Caregiver burnout increases the risk of patient neglect or abuse, as individuals who have been the targets of aggressive behavior are more likely to leave demented patients unattended.8,16,23 Although tools are available to screen caregivers for depression and burnout, an important step forward would be to develop an interprofessional team to aid in identifying and closely following high-risk patient–caregiver groups. This continual and varied assessment of psychosocial stressors could help prevent the development of violent interactions. These teams would allow integration with the primary health care system by frequent and effective shared communication of knowledge, development of goals, and shared decision-making.38 Setting expectations, providing support, and discussing safety strategies can improve the health and welfare of caregivers and patients with dementia alike.

CORRESPONDENCE

Abu Baker Sheikh, MD, MSC 10-5550, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; [email protected].

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

1. Wu YT, Beiser AS, Breteler MMB, et al. The changing prevalence and incidence of dementia over time - current evidence. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:327-339.

2. Cipriani G, Borin G, Vedovello M, et al. Sociopathic behavior and dementia. Acta Neurol Belg. 2013;113:111-115.

3. Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Danti S, et al. Violent and criminal manifestations in dementia patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:541-549.

4. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Different attitudes when handling aggressive behaviour in dementia—narratives from two caregiver groups. Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:277-286.

5. Kristiansen L, Hellzén O, Asplund K. Swedish assistant nurses’ experiences of job satisfaction when caring for persons suffering from dementia and behavioural disturbances. An interview study. Int J Qualitat Stud Health Well-being. 2006;1:245-256.

6. Wharton TC, Ford BK. What is known about dementia care recipient violence and aggression against caregivers? J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57:460-477.

7. Ostaszkiewicz J, Lakhan P, O’Connell B, et al. Ongoing challenges responding to behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Int Nurs Rev. 2015;62:506-516.

8. Kim J, De Bellis AM, Xiao LD. The experience of paid family-care workers of people with dementia in South Korea. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12:34-41.

9. Band-Winterstein T, Avieli H. Women coping with a partner’s dementia-related violence: a qualitative study. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2019; 51:368-379.

10. Munkejord MC, Stefansdottir OA, Sveinbjarnardottir EK. Who cares for the carer? The suffering, struggles and unmet needs of older women caring for husbands living with cognitive decline. Int Pract Devel J. 2020;10:1-11.

11. Seidel D, Thyrian JR. Burden of caring for people with dementia - comparing family caregivers and professional caregivers. A descriptive study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2019;12:655-663.

12. Tang W, Friedman DB, Kannaley K, et al. Experiences of caregivers by care recipient’s health condition: a study of caregivers for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias versus other chronic conditions. Geriatr Nurs. 2019;40:181-184.

13. Benbow SM, Bhattacharyya S, Kingston P. Older adults and violence: an analysis of domestic homicide reviews in England involving adults over 60 years of age. Ageing Soc. 2018;39:1097-1121.

14. Herron RV, Wrathall MA. Putting responsive behaviours in place: examining how formal and informal carers understand the actions of people with dementia. Soc Sci Med. 2018;204:9-15.

15. Herron RV, Rosenberg MW. Responding to aggression and reactive behaviours in the home. Dementia (London). 2019;18:1328-1340.

16. Spencer D, Funk LM, Herron RV, et al. Fear, defensive strategies and caring for cognitively impaired family members. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2019;62:67-85.

17. Skovdahl K, Kihlgren AL, Kihlgren M. Dementia and aggressiveness: stimulated recall interviews with caregivers after video-recorded interactions. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:515-525.

18. Needham I, Abderhalden C, Halfens RJ, et al. Non-somatic effects of patient aggression on nurses: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:283-296.

19. Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Examination for detecting mild cognitive impairment and dementia is more sensitive than the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) - a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;14:900-910.

20. Janzen S, Zecevic AA, Kloseck M, et al. Managing agitation using nonpharmacological interventions for seniors with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28:524-532.

21. Zeller A, Dassen T, Kok G, et al. Nursing home caregivers’ explanations for and coping strategies with residents’ aggression: a qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2469-2478.

22. Alzheimer’s Society. Fix dementia care: homecare. Accessed December 28, 2021. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/fix_dementia_care_homecare_report.pdf

23. von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, et al. Refining caregiver vulnerability for clinical practice: determinants of self-rated health in spousal dementia caregivers. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:18.

24. Chen HM, Huang MF, Yeh YC, et al. Effectiveness of coping strategies intervention on caregiver burden among caregivers of elderly patients with dementia. Psychogeriatrics. 2015; 15:20-25.

25. Wawrziczny E, Larochette C, Papo D, et al. A customized intervention for dementia caregivers: a quasi-experimental design. J Aging Health. 2019;31:1172-1195.

26. Gitlin LN, Piersol CV, Hodgson N, et al. Reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms in persons with dementia and associated burden in family caregivers using tailored activities: Design and methods of a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2016;49:92-102.

27. de Oliveira AM, Radanovic M, Homem de Mello PC, et al. An intervention to reduce neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia: preliminary results from a randomized trial of the tailored activity program-outpatient version. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:1301-1307.

28. Livingston G, Barber J, Rapaport P, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6276.

29. Kajiyama B, Fernandez G, Carter EA, et al. Helping Hispanic dementia caregivers cope with stress using technology-based resources. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41:209-216.

30. Moskowitz JT, Cheung EO, Snowberg KE, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a facilitated online positive emotion regulation intervention for dementia caregivers. Health Psychol. 2019;38:391-402.

31. Yoon HK, Kim GS. An empowerment program for family caregivers of people with dementia. Public Health Nurs. 2020;37:222-233.

32. Zwingmann I, Dreier-Wolfgramm A, Esser A, et al. Why do family dementia caregivers reject caregiver support services? Analyzing types of rejection and associated health-impairments in a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:121.

33. Nybakken S, Strandås M, Bondas T. Caregivers’ perceptions of aggressive behaviour in nursing home residents living with dementia: A meta-ethnography. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:2713-2726.

34. Nakaishi L, Moss H, Weinstein M, et al. Exploring workplace violence among home care workers in a consumer-driven home health care program. Workplace Health Saf. 2013;61:441-450.

35. Medical Advisory Secretariat. Caregiver- and patient-directed interventions for dementia: an evidence-based analysis. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2008;8:1-98.

36. Betz ME, McCourt AD, Vernick JS, et al. Firearms and dementia: clinical considerations. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:47-49.

37. Leng M, Zhao Y, Wang Z. Comparative efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions on agitation in people with dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;102:103489.

38. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Screen caregivers and family members of patients with dementia for signs of interpersonal violence. C

› Counsel caregivers early on that behavior changes in patients with dementia are likely and may be unpredictable. C

› Discuss safety strategies for the caregiver, including when it is appropriate to alter routines such as bedtimes and meals. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

An overlooked cause of dyspepsia?

Discussion of a common cause of dyspepsia was missing from your September article, “Dyspepsia: A stepwise approach to evaluation and management” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:320-325). After more than 25 years of practice, I have found that most people with dyspepsia have hypochlorhydria1—a condition that results in the inability to produce adequate amounts of hydrochloric acid, or stomach acid. With lower amounts of stomach acid, food does not break down but ferments instead, producing gas and discomfort.

I use a simple test to diagnose patients with hypochlorhydria. The patient takes a capsule of hydrochloric acid directly after eating a meal; failure to experience epigastric burning within 30 minutes of ingesting the capsule indicates a need for additional stomach acid with a meal. If they do experience a burning sensation within 30 minutes, it indicates they do not need additional stomach acid. The burning sensation is relieved by drinking 2 teaspoons of baking soda in 4 oz of water to neutralize the excess acid.

In my experience, most people who take the test do not experience a sense of burning. I find that once these patients with hypochlorhydria start taking betaine hydrochloride with their meals, they no longer need the many over-the-counter or prescription antacids and their dyspepsia disappears. Many of my patients find that after a few months, they begin to experience burning and can discontinue the supplement, without facing a return of their dyspepsia.

Marianne Rothschild, MD

Mount Airy, MD

1. Iwai W, Abe Y, Iijima K, et al. Gastric hypochlorhydria is associated with an exacerbation of dyspeptic symptoms in female patients. J Gastoenterol. 2012;48:214-221. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0634-8

Editor’s note

After reading Dr. Rothschild’s letter, I decided to do a little digging to find out if there is any research evidence to support her approach to dyspepsia. I carefully searched PubMed and found only 2 observational studies showing an association between dyspepsia and hypochlorhydria. There are no randomized trials of dyspepsia treatment with hydrochloric acid to support her clinical observations. Placebo effect? Until there is a good, randomized trial, we will not know. But who would have guessed that H pylori causes peptic ulcers?

John Hickner, MD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief, The Journal of Family Practice

Discussion of a common cause of dyspepsia was missing from your September article, “Dyspepsia: A stepwise approach to evaluation and management” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:320-325). After more than 25 years of practice, I have found that most people with dyspepsia have hypochlorhydria1—a condition that results in the inability to produce adequate amounts of hydrochloric acid, or stomach acid. With lower amounts of stomach acid, food does not break down but ferments instead, producing gas and discomfort.

I use a simple test to diagnose patients with hypochlorhydria. The patient takes a capsule of hydrochloric acid directly after eating a meal; failure to experience epigastric burning within 30 minutes of ingesting the capsule indicates a need for additional stomach acid with a meal. If they do experience a burning sensation within 30 minutes, it indicates they do not need additional stomach acid. The burning sensation is relieved by drinking 2 teaspoons of baking soda in 4 oz of water to neutralize the excess acid.

In my experience, most people who take the test do not experience a sense of burning. I find that once these patients with hypochlorhydria start taking betaine hydrochloride with their meals, they no longer need the many over-the-counter or prescription antacids and their dyspepsia disappears. Many of my patients find that after a few months, they begin to experience burning and can discontinue the supplement, without facing a return of their dyspepsia.

Marianne Rothschild, MD

Mount Airy, MD

1. Iwai W, Abe Y, Iijima K, et al. Gastric hypochlorhydria is associated with an exacerbation of dyspeptic symptoms in female patients. J Gastoenterol. 2012;48:214-221. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0634-8

Editor’s note

After reading Dr. Rothschild’s letter, I decided to do a little digging to find out if there is any research evidence to support her approach to dyspepsia. I carefully searched PubMed and found only 2 observational studies showing an association between dyspepsia and hypochlorhydria. There are no randomized trials of dyspepsia treatment with hydrochloric acid to support her clinical observations. Placebo effect? Until there is a good, randomized trial, we will not know. But who would have guessed that H pylori causes peptic ulcers?

John Hickner, MD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief, The Journal of Family Practice

Discussion of a common cause of dyspepsia was missing from your September article, “Dyspepsia: A stepwise approach to evaluation and management” (J Fam Pract. 2021;70:320-325). After more than 25 years of practice, I have found that most people with dyspepsia have hypochlorhydria1—a condition that results in the inability to produce adequate amounts of hydrochloric acid, or stomach acid. With lower amounts of stomach acid, food does not break down but ferments instead, producing gas and discomfort.

I use a simple test to diagnose patients with hypochlorhydria. The patient takes a capsule of hydrochloric acid directly after eating a meal; failure to experience epigastric burning within 30 minutes of ingesting the capsule indicates a need for additional stomach acid with a meal. If they do experience a burning sensation within 30 minutes, it indicates they do not need additional stomach acid. The burning sensation is relieved by drinking 2 teaspoons of baking soda in 4 oz of water to neutralize the excess acid.

In my experience, most people who take the test do not experience a sense of burning. I find that once these patients with hypochlorhydria start taking betaine hydrochloride with their meals, they no longer need the many over-the-counter or prescription antacids and their dyspepsia disappears. Many of my patients find that after a few months, they begin to experience burning and can discontinue the supplement, without facing a return of their dyspepsia.

Marianne Rothschild, MD

Mount Airy, MD

1. Iwai W, Abe Y, Iijima K, et al. Gastric hypochlorhydria is associated with an exacerbation of dyspeptic symptoms in female patients. J Gastoenterol. 2012;48:214-221. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0634-8

Editor’s note

After reading Dr. Rothschild’s letter, I decided to do a little digging to find out if there is any research evidence to support her approach to dyspepsia. I carefully searched PubMed and found only 2 observational studies showing an association between dyspepsia and hypochlorhydria. There are no randomized trials of dyspepsia treatment with hydrochloric acid to support her clinical observations. Placebo effect? Until there is a good, randomized trial, we will not know. But who would have guessed that H pylori causes peptic ulcers?

John Hickner, MD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief, The Journal of Family Practice

Gut Microbiota for Health World Summit 2022

Registration is now open for the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2022, taking place March 12-13 in Washington, D.C., and virtually.

Organized by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the GMFH World Summit is the preeminent international meeting on the gut microbiome for clinicians, dietitians and researchers.

Now in its 10th year, the program for this year’s conference will focus on “The Gut Microbiome in Precision Nutrition and Medicine.” Join us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in precision medicine and discover personalized approaches to modulating the gut microbiome that may promote health and improve patient outcomes for a variety of disorders and diseases.

Registration is now open for the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2022, taking place March 12-13 in Washington, D.C., and virtually.

Organized by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the GMFH World Summit is the preeminent international meeting on the gut microbiome for clinicians, dietitians and researchers.

Now in its 10th year, the program for this year’s conference will focus on “The Gut Microbiome in Precision Nutrition and Medicine.” Join us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in precision medicine and discover personalized approaches to modulating the gut microbiome that may promote health and improve patient outcomes for a variety of disorders and diseases.

Registration is now open for the Gut Microbiota for Health (GMFH) World Summit 2022, taking place March 12-13 in Washington, D.C., and virtually.

Organized by AGA and the European Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM), the GMFH World Summit is the preeminent international meeting on the gut microbiome for clinicians, dietitians and researchers.

Now in its 10th year, the program for this year’s conference will focus on “The Gut Microbiome in Precision Nutrition and Medicine.” Join us to gain a deeper understanding of the role of the gut microbiome in precision medicine and discover personalized approaches to modulating the gut microbiome that may promote health and improve patient outcomes for a variety of disorders and diseases.

Keeping an open mind about functional medicine

Considering the controversy surrounding functional medicine, you may be wondering why JFP published an article about it last month.1 David Gorski, MD, PhD, FACS, a vocal critic of functional medicine, commented: “Functional medicine. It sounds so … scientific and reasonable. It’s anything but. In fact, functional medicine combines the worst features of conventional medicine with a heapin’ helpin’ of quackery.”2 On its website, however, The Institute for Functional Medicine claims that “functional medicine determines how and why illness occurs and restores health by addressing the root causes of disease for each individual.”3

I suspect the truth lies somewhere in between.

Because functional medicine has gained a certain degree of popularity, I felt it was important for family physicians and other primary care clinicians to know enough about this alternative healing method to discuss it with patients who express interest.

In their review article in JFP, Orlando and colleagues tell us there are 7 defining characteristics of functional medicine.1 It is patient centered rather than disease centered, uses a “systems biology” approach, considers the dynamic balance of gene-environment interactions, is personalized based on biochemical individuality, promotes organ reserve and sustained health span, sees health as a positive vitality (not merely the absence of disease), and focuses on function rather than pathology.

Most of these statements about functional medicine apply to traditional family medicine. The clinical approach stressing lifestyle changes is mainstream, not unique. The focus on digestion and the microbiome as an important determinant of health is based on interesting basic science studies and associations noted between certain microbiome profiles and diseases.

But association is not causation. So far there is scant evidence that changing the microbiome results in better health, although some preliminary case series have generated intriguing hypotheses. And there is evidence that probiotics improve some symptoms. Ongoing research into the microbiome and health will, no doubt, be illuminating. We have much to learn.

What does seem unique, but suspect, about functional medicine is its focus on biochemical testing of unproven value and the prescribing of diets and supplements based on the test results. There are no sound scientific studies showing the benefit of this approach.

I suggest you read Orlando et al’s article. Functional medicine is an interesting, mostly unproven, approach to patient care. But I will keep an open mind until we see better research that either does—or doesn’t—support the validity of its practices.

1. Orlando FA, Chang KL, Estores IM. Functional medicine: focusing on imbalances in core metabolic processes. J Fam Pract. 2021;70:482-488,498.

2. Gorski D. Functional medicine: the ultimate misnomer in the world of integrative medicine. Science-Based Medicine. April 11, 2016. Accessed January 4, 2022. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/functional-medicine-the-ultimate-misnomer-in-the-world-of-integrative-medicine/

3. The Institute for Functional Medicine. Accessed January 4, 2022. www.ifm.org

Considering the controversy surrounding functional medicine, you may be wondering why JFP published an article about it last month.1 David Gorski, MD, PhD, FACS, a vocal critic of functional medicine, commented: “Functional medicine. It sounds so … scientific and reasonable. It’s anything but. In fact, functional medicine combines the worst features of conventional medicine with a heapin’ helpin’ of quackery.”2 On its website, however, The Institute for Functional Medicine claims that “functional medicine determines how and why illness occurs and restores health by addressing the root causes of disease for each individual.”3

I suspect the truth lies somewhere in between.

Because functional medicine has gained a certain degree of popularity, I felt it was important for family physicians and other primary care clinicians to know enough about this alternative healing method to discuss it with patients who express interest.

In their review article in JFP, Orlando and colleagues tell us there are 7 defining characteristics of functional medicine.1 It is patient centered rather than disease centered, uses a “systems biology” approach, considers the dynamic balance of gene-environment interactions, is personalized based on biochemical individuality, promotes organ reserve and sustained health span, sees health as a positive vitality (not merely the absence of disease), and focuses on function rather than pathology.

Most of these statements about functional medicine apply to traditional family medicine. The clinical approach stressing lifestyle changes is mainstream, not unique. The focus on digestion and the microbiome as an important determinant of health is based on interesting basic science studies and associations noted between certain microbiome profiles and diseases.

But association is not causation. So far there is scant evidence that changing the microbiome results in better health, although some preliminary case series have generated intriguing hypotheses. And there is evidence that probiotics improve some symptoms. Ongoing research into the microbiome and health will, no doubt, be illuminating. We have much to learn.

What does seem unique, but suspect, about functional medicine is its focus on biochemical testing of unproven value and the prescribing of diets and supplements based on the test results. There are no sound scientific studies showing the benefit of this approach.

I suggest you read Orlando et al’s article. Functional medicine is an interesting, mostly unproven, approach to patient care. But I will keep an open mind until we see better research that either does—or doesn’t—support the validity of its practices.

Considering the controversy surrounding functional medicine, you may be wondering why JFP published an article about it last month.1 David Gorski, MD, PhD, FACS, a vocal critic of functional medicine, commented: “Functional medicine. It sounds so … scientific and reasonable. It’s anything but. In fact, functional medicine combines the worst features of conventional medicine with a heapin’ helpin’ of quackery.”2 On its website, however, The Institute for Functional Medicine claims that “functional medicine determines how and why illness occurs and restores health by addressing the root causes of disease for each individual.”3

I suspect the truth lies somewhere in between.

Because functional medicine has gained a certain degree of popularity, I felt it was important for family physicians and other primary care clinicians to know enough about this alternative healing method to discuss it with patients who express interest.

In their review article in JFP, Orlando and colleagues tell us there are 7 defining characteristics of functional medicine.1 It is patient centered rather than disease centered, uses a “systems biology” approach, considers the dynamic balance of gene-environment interactions, is personalized based on biochemical individuality, promotes organ reserve and sustained health span, sees health as a positive vitality (not merely the absence of disease), and focuses on function rather than pathology.

Most of these statements about functional medicine apply to traditional family medicine. The clinical approach stressing lifestyle changes is mainstream, not unique. The focus on digestion and the microbiome as an important determinant of health is based on interesting basic science studies and associations noted between certain microbiome profiles and diseases.

But association is not causation. So far there is scant evidence that changing the microbiome results in better health, although some preliminary case series have generated intriguing hypotheses. And there is evidence that probiotics improve some symptoms. Ongoing research into the microbiome and health will, no doubt, be illuminating. We have much to learn.

What does seem unique, but suspect, about functional medicine is its focus on biochemical testing of unproven value and the prescribing of diets and supplements based on the test results. There are no sound scientific studies showing the benefit of this approach.