User login

A practical guide to appendicitis evaluation and treatment

CASE

A 35-year-old man with a body mass index of 20 presented to the emergency department after 24 hours of abdominal pain that began in the periumbilical region and then migrated to the right lower quadrant. The pain was exacerbated during ambulation and was intense when the car transporting him to the hospital encountered bumps in the road. After his pain started, he had associated anorexia, followed by nausea and emesis. He reported fever and chills. On examination, his temperature was 100.8 °F (38.2 °C), and palpation of the right and left lower quadrants elicited right lower quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 14,000 cells/mcL with 85% neutrophils, C-reactive protein of 40 mg/L, and a negative urinalysis.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of abdominal pain resulting in the need for surgical treatment; lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6% to 7%.1 Appendicitis is caused by intraluminal obstruction in the appendix from enlarged lymphoid tissue or a fecalith. The obstruction leads to elevated intraluminal pressure due to persistent mucus and gas production by bacteria, ultimately leading to ischemia and perforation.1 Additionally, obstruction leads to bacterial overgrowth, most commonly colonic flora such as Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Streptococcus viridans, Enterococcus sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniaei.1,2

The following review provides a look at how 3 clinical scoring systems compare in the identification of acute appendicitis and details which imaging studies you should order—and when. But first, we’ll quickly detail the relevant physical findings and lab values that point to a diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Physical findings. The patient typically first experiences vague abdominal pain that then localizes to the right lower quadrant due to peritoneal inflammation. Anorexia and nausea typically follow the abdominal pain. On examination, the patient often appears ill and exhibits abdominal guarding due to peritonitis. Tachycardia and fever are common; however, the absence of either does not exclude appendicitis. Classically, on palpation, the patient will have pain at McBurney’s point (one-third the distance from the anterior iliac spine to the umbilicus). The exact point of maximal tenderness can differ because of the varying anatomy of the appendix (retrocecal, paracolic, pelvic, pre/post ileal, promontoric, or subcecal).1 Right lower quadrant pain, abdominal rigidity, and radiation of periumbilical pain to the right lower quadrant are the most accurate findings in adults to rule in appendicitis.3 For children, physical exam findings have the highest likelihood in predicting appendicitis and include a positive Obturator sign, positive Rovsing sign, or a positive Psoas sign, and absent or decreased bowel sounds.4

Laboratory studies can support a diagnosis of appendicitis but cannot exclude it. Leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance is present in 90% of cases.5 An elevated C-reactive protein level renders the highest diagnostic accuracy.5 Perform a pregnancy test for any woman of child-bearing age, to assist in the diagnosis and guide imaging choices for evaluation. Additional laboratory tests are not needed unless there are concerns about volume depletion.

Clinical scoring systems

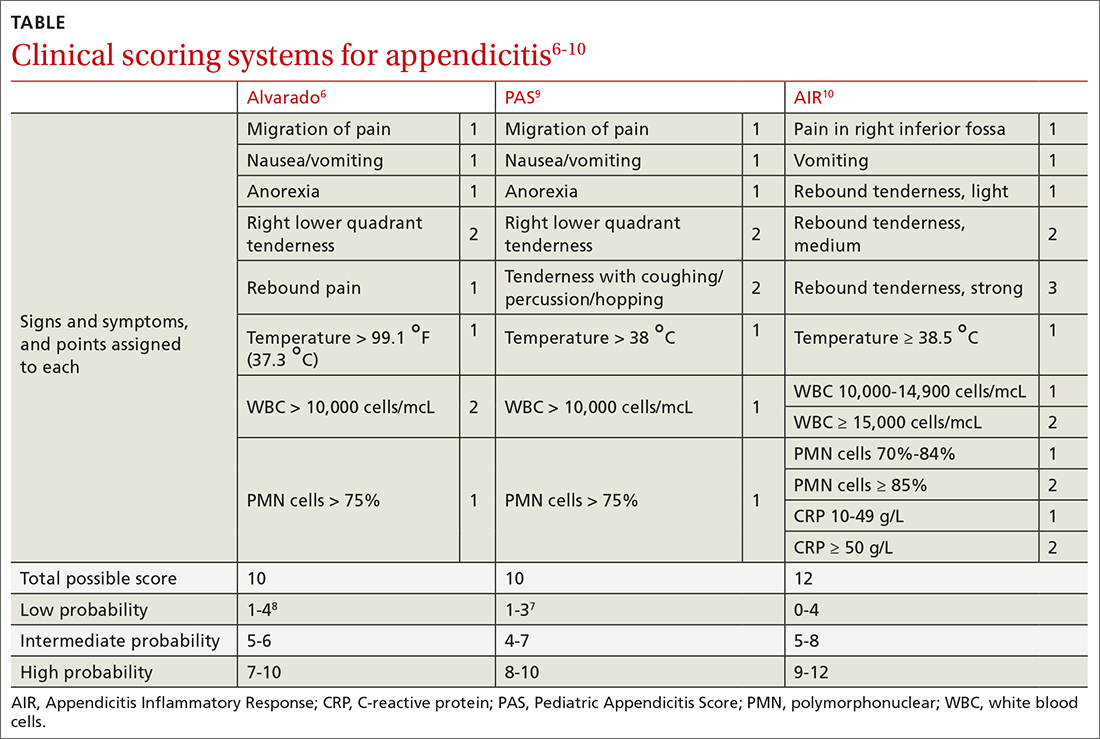

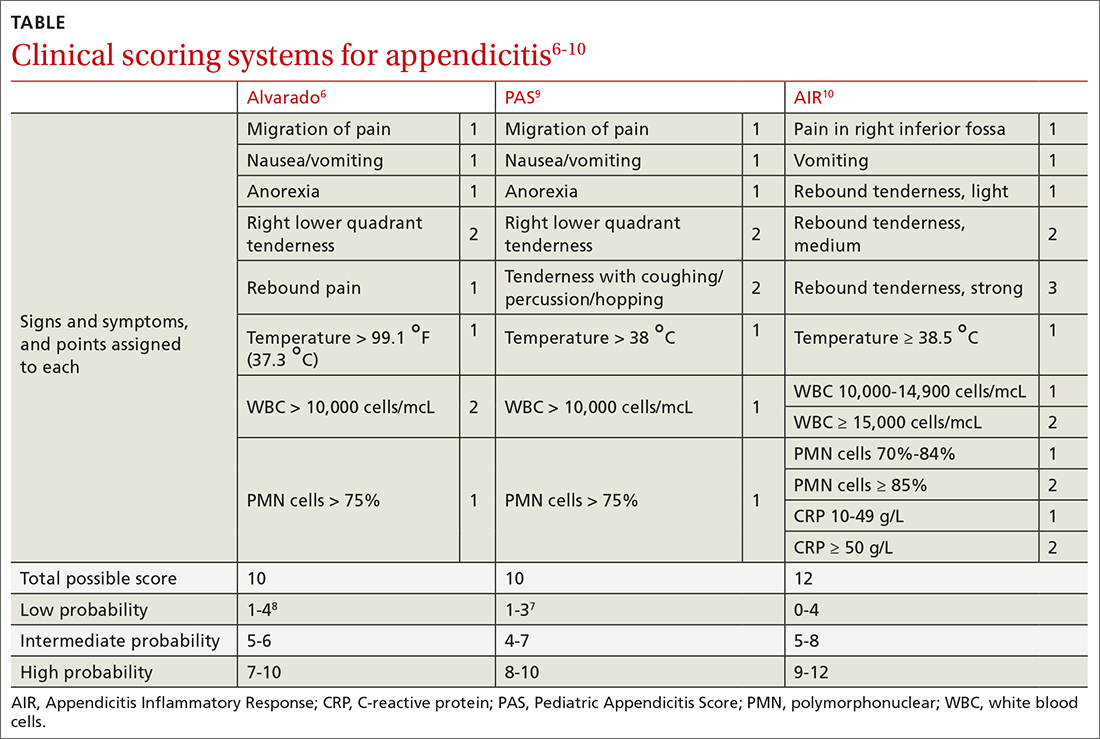

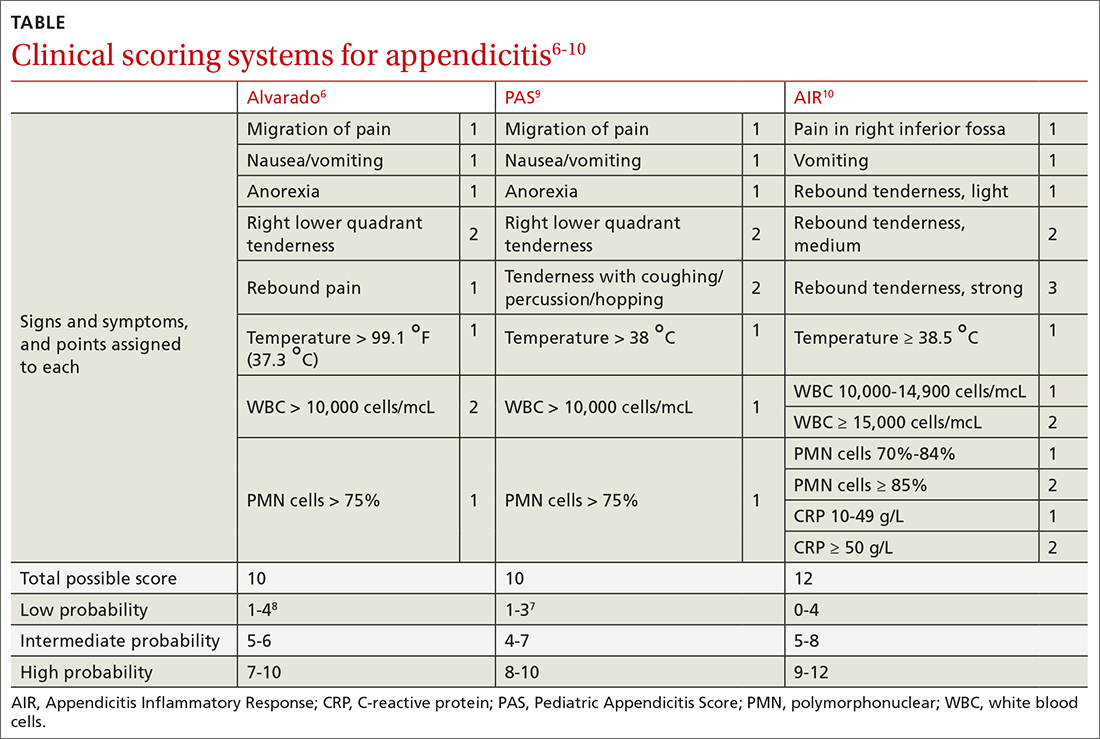

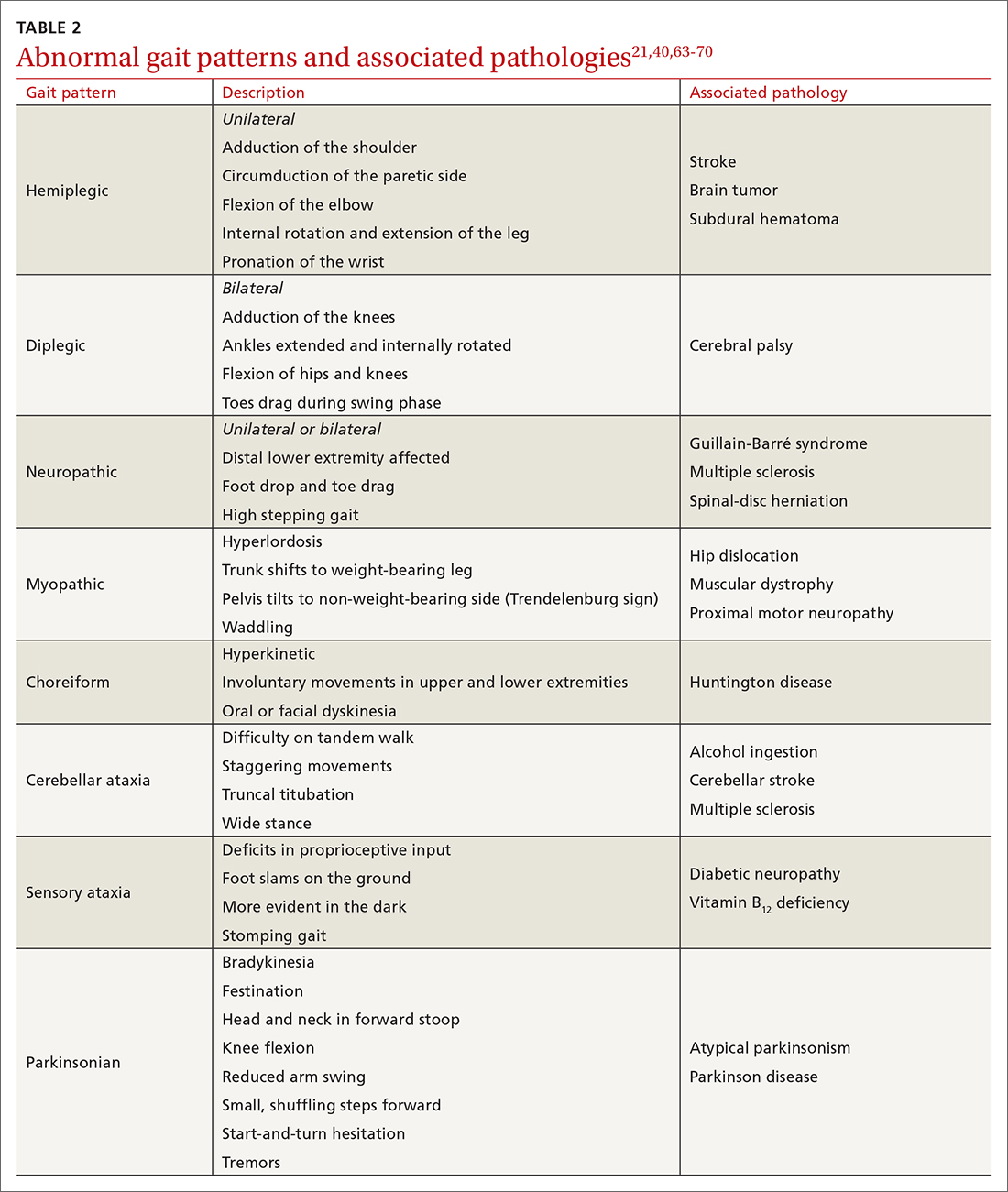

Several clinical scoring systems (TABLE6-10) have been validated to aid clinicians in evaluating patients with possible appendicitis, to decrease unnecessary exposure to ionizing radiation from computed tomography (CT) scans, to identify and reassure patients with low likelihoods of appendicitis, and to conduct outpatient follow-up.

Continue to: The Alvarado score

The Alvarado score is the oldest scoring rule, developed in 1986; it entails 8 clinical and laboratory variables.6 Ebell et al altered the proposed cutoff values of the Alvarado score to be low risk (< 4), intermediate risk (4-8), and high risk (≥ 9), effectively improving the sensitivity and specificity rates.7

In a meta-analysis of the Alvarado score that included 42 studies of men, women, and children, the sensitivity for “ruling out” appendicitis with a cutoff of 5 points was 96% for men, 99% for women, and 99% for children.8 The accuracy of a high-risk score (> 7) for “ruling in” appendicitis was less with an overall specificity of 82%.8 The Alvarado score did seem to overestimate appendicitis in women in all score categories.8

The Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS) is similar to Alvarado and was prospectively validated in 1170 children in 2002 for more specific guidance in this age group.9 The PAS had excellent specificity in the study; those with a score of ≥ 6 had a high probability of appendicitis. In a study comparing Alvarado with PAS in 311 patients, insignificant differences were noted at a score of ≥ 7 for both tests (sensitivity 86% vs 89%, and specificity 59% vs 50%, respectively).11 No scoring system has been found to be sufficiently accurate for use in children 4 years of age and younger.12

The Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) Score was prospectively validated in 545 patients representing all age groups.10 Subsequently, in a larger prospective multicenter study of 3878 patients older than 5 years, the original cut points were altered, thereby improving test sensitivity and negative predictive value to 99% for those with low probability (0 to 3), and test specificity to 98% for those with high-probability (9 to 12).13 Compared with the Alvarado Score, the AIR Score has higher specificity for those in the high-probability range, and similar exclusion rates in the low-probability range.14

Caveats with clinical decision scores. These tools are accepted and often used. However, challenges that affect generalizability of study data include differences in patient selection for each study (undifferentiated abdominal pain vs appendicitis), prospective vs retrospective designs, and age and gender variations in the patient populations. Despite the numerous scoring systems developed, none can accurately be used to rule in appendicitis. They are best used to assist in ruling out appendicitis and to aid in deciding for or against imaging.

Continue to: A look at the imaging options

A look at the imaging options

Abdominal CT has sensitivity and specificity rates between 76% and 100% and 83% and 100%, respectively.15,20,21 Ultrasonography has sensitivity and specificity rates of 71% to 94% and 81% to 98%, respectively.15,20,21 Formal US is reliable to confirm appendicitis, but less so to rule out appendicitis. Special considerations for imagining in pregnant patients and children are discussed in a bit.

Timing of surgical consultation

Surgical consultation is paramount once the diagnosis of appendicitis is probable. Imaging is best obtained prior to surgical consultation to streamline evaluation and enhance decision- making. Typically, patients will be categorized as complicated or uncomplicated based on the presence or absence of perforation, a gangrenous appendix, an intra-abdominal abscess (IAA), or purulent peritonitis. Active continuous surgical involvement (co-management or assumption of care) is recommended in all cases of appendicitis, especially if nonoperative management is selected, given that some cases must convert to immediate operative treatment or may be selected for delayed future (interval) appendectomy.22

Management

Uncomplicated appendicitis

Prompt appendectomy has been the gold standard of care for uncomplicated acute appendicitis for 60 years. However, several studies have investigated an antibiotic-based strategy rather than surgical treatment for uncomplicated appendicitis.

Antibiotics vs appendectomy. In 2020, the CODA Collaborative published a randomized trial comparing a 10-day course of antibiotics with appendectomy in patients with uncomplicated appendicitis. In this multicenter study based in the United States, 1552 patients 18 years of age or older were randomized to receive antibiotics or undergo appendectomy (95% performed laparoscopically). The antibiotic treatment consisted of at least 24 hours of IV antibiotics, with or without admission to the hospital. Antibiotic choice was individualized according to guidelines for intra-abdominal infection published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, with the most common IV medications being ertapenem, cefoxitin, or metronidazole plus one of the following: ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or levofloxacin. For the remaining 10 days, oral metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin or cefdinir were used.22

Continue to: The primary endpoint...

The primary endpoint was the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, with secondary outcomes including appendectomy in the antibiotics group and complications through 90 days. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, sepsis, peritonitis, recurrent appendicitis, severe phlegmon on imaging, or evidence of neoplasm.22

Antibiotics were noninferior to appendectomy for the 30-day study. However, antibiotics failed in 29%, who then proceeded to appendectomy by 90 days; these patients also accounted for 41% of those with an appendicolith. Overall complications were more common in the antibiotics group than in the appendectomy group (8.1 vs 3.5 per 100 participants; 95% CI, 1.3-3.98). Also more common in the antibiotic group were serious adverse events (4 vs 3 per 100 participants; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% CI, 0.67-2.50). The presence of an appendicolith in the antibiotics group increased the conversion risk to appendectomy, as well as adverse events risk.22

The takeaway. Antibiotic treatment is a noninferior method to treat acute uncomplicated appendicitis. However, the informed consent process is important, given the ~30% failure rate. Patient factors such as continued access to care should help inform the decision.

Two main surgical approaches exist for appendectomy: open and minimally invasive. At this time, the minimally invasive options include laparoscopic, single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), and robotic appendectomy. A study comparing cost, availability, or complications of these options has not been conducted at this time.

A large Cochrane review of 67 studies examining open vs laparoscopic appendectomy in adults and children completed in 2018 revealed that the laparoscopic approach reduced early postoperative pain intensity and led to a shorter hospital stay, earlier return to work or usual activities, and a decrease in wound infections.23 The odds of IAA occurring with laparoscopic appendectomy increased by 65% compared with an open procedure; however, postoperative bowel obstruction and incisional hernias were less likely to occur.23 Additionally, following laparoscopic surgery, postoperative bowel obstruction and incisional hernias are less likely to occur. The laparoscopic approach is preferred due to overall increased patient satisfaction and a reduction in most, if not all, complications.

Continue to: Complicated appendicitis

Complicated appendicitis

Excluding patients with severe sepsis or purulent peritonitis requiring resuscitation and immediate surgical intervention of intra-abdominal infection, the approach to patients with complicated appendicitis varies between aggressive surgical intervention and nonoperative management.

In a 2007 meta-analysis reviewing nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess/phlegmon, immediate surgery was associated with higher morbidity.24 Within the nonoperative management group 7.2% (CI, 4.0-10.5) required surgical intervention and 19.7% (CI, 11.0-28.3) required abscess drainage. Malignant disease was detected in 1.2% (CI, 0.6-1.7).24 Small subsequent studies concluded different results.25

Ultimately, the 2015 European Association of Endoscopic Surgery guidelines recommend a new systematic review; but with current data, initial nonoperative management is preferred.15 After initial nonoperative treatment, the only benefits from interval appendectomy are identification of an underlying malignancy (6% to 20%) and mitigating the risk of recurrent appendicitis (5% to 44%).15,25-30

Multiple single institutional series found increased neoplasm incidence (9% to 20%) in complicated appendicitis in patients 40 years and older.26-30 Prior to interval appendectomy in patients 45 years and older, ensuring they have an up-to-date screening colonoscopy is important. This is in line with 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force (Grade “B” recommendation), 2018 American Cancer Society (qualified recommendation), and 2021 American College of Gastroenterology (conditional recommendation) guidelines for colorectal cancer screening to start at age 45 in average-risk patients.31 Patients younger than 45 can consider screening through shared decision-making.

Special populations

Pregnant patients

In pregnancy, challenges exist with the presence of traditional signs and symptoms of appendicitis, with the most predictive sign being a WBC count higher than 18,000.32 The American College of Radiology’s (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria recommend US as the imaging modality of choice in pregnancy, with MRI as the best option when US is inconclusive.33 Two meta-analyses demonstrated high sensitivity (91.8%-96.6%) and specificity (95.9%-97.9%) of MRI in diagnosing appendicitis.34,35 CT scan is not the preferred initial imagining modality in pregnancy unless urgent information is needed and other modalities are insufficient or unavailable.36

Continue to: The most common...

The most common nonobstetric surgical intervention during pregnancy is appendectomy, at a rate of 6.3/10,000 person-years, which increases to 9.9/10,000 in the postpartum period.37 Two large population studies demonstrate the rate of appendicitis varies over the course of pregnancy, with the lowest rates in the third trimester,38,39 and a significant rebound lasting for 2 years postpartum.39 Peritonitis, septic shock, pneumonia, postoperative infection, and longer hospital stays occur more frequently in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women with appendicitis.40 Fetal loss is higher in the first trimester.32

In a 14-year review of 63,145 appendicitis cases, an increased risk of fetal loss and maternal death was noted across ages and ethnicities, with the largest risk of maternal death occurring in Hispanics and fetal death in non-Hispanic Blacks.41 In a large study of 1018 adverse events after appendectomy or cholecystectomy, the 3 most common events were preterm delivery (35.4%), preterm labor without preterm delivery (26.4%), and miscarriage (25.7%).42 The surgery itself was not a major risk factor for adverse events. Major risk factors included cervical incompetence (odds ratio [OR] = 24.3), preterm labor in current pregnancy (OR = 18.3), and presence of vulvovaginitis (OR = 5.2).42

Nonoperative management in pregnancy is not recommended; only 1 prospective trial has been done, with 20 patients, showing a 25% failure rate.43 Two meta-analyses published in 2019 highlight the potential increase of fetal loss with laparoscopic approaches to appendectomy.44,45 However, recently published literature demonstrates no significant maternal-fetal morbidity. Current guidelines of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons agree that laparoscopy is the operative choice in pregnancy.36

Children

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in children.4 Physical exam findings and laboratory results are not classic in this population, obtaining an accurate history can be challenging, and results of clinical scoring systems can be inconclusive.4 Additional serum biomarkers, procalcitonin and calprotectin, are gaining evidence for use in improving scoring systems to refine low-risk groups. Unavailability of timely, reliable biomarker testing in rural practice locations limits definitive recommendations at this time.46 ACR recommends no imaging in a pediatric patient whose risk of having appendicitis is low based on any of several scoring systems.47 For those assessed as having higher risk, US is the recommended initial modality,with CT with IV contrast or MRI without contrast equally recommended if the US is equivocal.47

Despite promising data from trials of nonoperative treatment for adults with appendicitis, no definitive evidence and recommendations are available for children. Two systematic reviews show nonoperative treatment is safe, with an efficacy rate of 76% to 82% at long-term follow-up,48,49 although the success of antibiotic regimens varies. Within the nonoperative treatment group, 16% of patients had appendectomy during the follow-up period, which varied from 8 weeks to 4 years.48 A randomized controlled trial is needed for final guidance.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

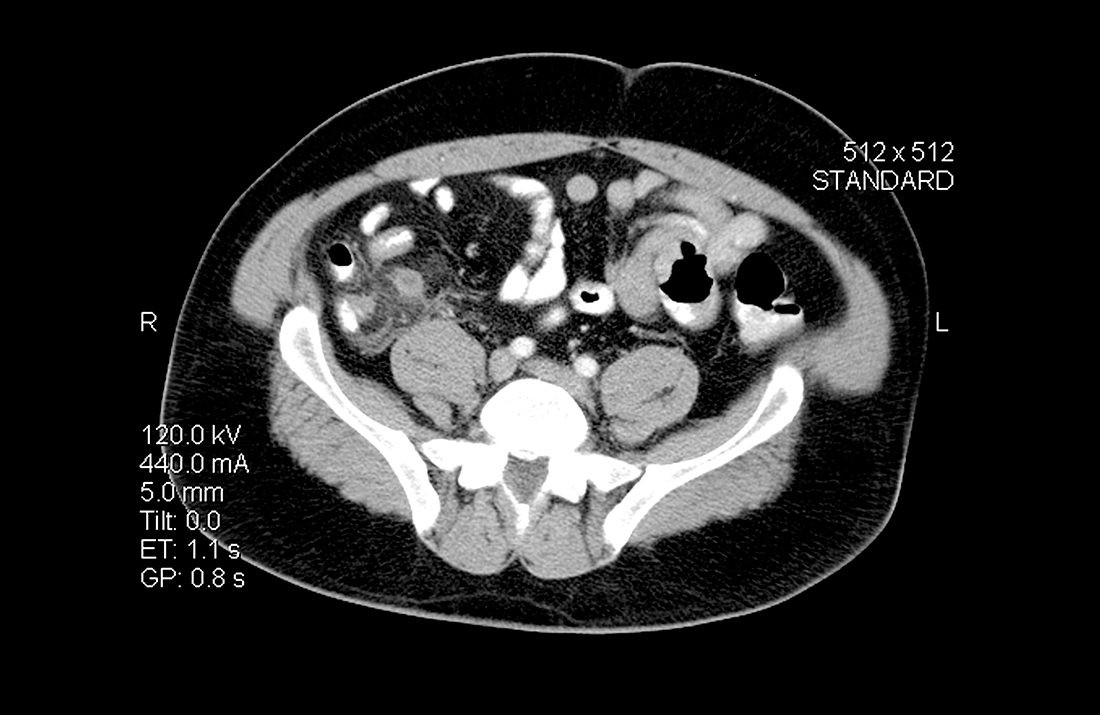

The patient had an Alvarado score of 9 (high probability) and an AIR score of 6 (intermediate probability). A CT with IV contrast showed a 9-mm fluid-filled appendix with periappendiceal fluid. During surgical consultation, he was offered laparoscopic appendectomy or nonoperative treatment with antibiotics. He opted for a preoperative dose of piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV and laparoscopic appendectomy. The patient was discharged home 6 hours after his procedure.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Servey, MD, MHPE, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected]

1. Prystowsky JB, Pugh CM, Nagle AP. Current problems in surgery. Appendicitis. Curr Probl Surg. 2005;42:688-742.

2. Song DW, Park BK, Suh SW, et al. Bacterial culture and antibiotic susceptibility in patients with acute appendicitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:441-447.

3. Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA. 1996;276:1589-1594.

4. Benabbas R, Hanna M, Shah J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and point-of-care ultrasound for pediatric acute appendicitis in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:523-551.

5. Andersson RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28-37.

6. Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557-564.

7. Ebell MH, Shinholser J. What are the most clinically useful cutoffs for the Alvarado and Pediatric Appendicitis Scores? A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:365-372.e2.

8. Ohle R, O’Reilly F, O’Brien KK, et al. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:139.

9. Samuel M. Pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:877-881.

10. Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843-1849.

11. Pogorelić Z, Rak S, Mrklić I, et al. Prospective validation of Alvarado score and Pediatric Appendicitis Score for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:164-168.

12. Rassi R, Muse F, Sánchez-Martínez J, et al. Diagnostic value of clinical prediction scores for acute appendicitis in children younger than 4 years. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2021. [Online ahead of print]

13. Andersson M, Kolodziej B, Andersson RE. Validation of the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) score. World J Surg. 2021;45:2081-2091.

14. Kollár D, McCartan DP, Bourke M, et al. Predicting acute appendicitis? A comparison of the Alvarado score, the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score and clinical assessment. World J Surg. 2015;39:104-109.

15. Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis. EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4668-4690.

16. Matthew Fields J, Davis J, Alsup C, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasonography for diagnosing acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1124-1136.

17. Sharif S, Skitch S, Vlahaki D, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound to diagnose appendicitis in a Canadian emergency department. CJEM. 2018;20:732-735.

18. Doniger SJ, Kornblith A. Point-of-care ultrasound integrated into a staged diagnostic algorithm for pediatric appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:109-115.

19. Menon N, Kumar S, Keeler B, et al. A systematic review of point-of-care abdominal ultrasound scans performed by general surgeons. Surgeon. 2021. [Online ahead of print]

20. Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, et al. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241:83-94.

21. van Randen A, Laméris W, van Es HW, et al. A comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and computed tomography in common diagnoses causing acute abdominal pain. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1535-1545.

22. Flum DR, Davidson GH, Monsell SE, et al. A randomized trial comparing antibiotics with appendectomy for appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1907-1919.

23. Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD001546.

24. Andersson RE, Petzold MG. Nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:741-748.

25. Deelder JD, Richir MC, Schoorl T, et al. How to treat an appendiceal inflammatory mass: operatively or nonoperatively? J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:641-645.

26. Carpenter SG, Chapital AB, Merritt MV, et al. Increased risk of neoplasm in appendicitis treated with interval appendectomy: single-institution experience and literature review. Am Surg. 2012;78:339-343.

27. Hayes D, Reiter S, Hagen E, et al. Is interval appendectomy really needed? A closer look at neoplasm rates in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy after complicated appendicitis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:3855-3860.

28. Peltrini R, Cantoni V, Green R, et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm after interval appendectomy for complicated appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2021. [Online ahead of print.]

29. Mällinen J, Rautio T, Grönroos J, et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm in periappendicular abscess in patients treated with interval appendectomy vs follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging: 1-year outcomes of the peri-appendicitis acuta randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:200-207.

30. Son J, Park YJ, Lee SR, et al. Increased risk of neoplasms in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy. Ann Coloproctol. 2020;36:311-315.

31. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977.

32. Theilen LH, Mellnick VM, Shanks AL, et al. Acute appendicitis in pregnancy: predictive clinical factors and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:523-528.

33. Garcia EM, Camacho MA, Karolyi DR, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria right lower quadrant pain-suspected appendicitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:S373-s387.

34. Kave M, Parooie F, Salarzaei M. Pregnancy and appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the clinical use of MRI in diagnosis of appendicitis in pregnant women. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:37.

35. Repplinger MD, Levy JF, Peethumnongsin E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of MRI to diagnose appendicitis in the general population. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:1346-1354.

36. Pearl JP, Price RR, Tonkin AE, et al. SAGES guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3767-3782.

37. Zingone F, Sultan AA, Humes DJ, et al. Risk of acute appendicitis in and around pregnancy: a population-based cohort study from England. Ann Surg. 2015;261:332-337.

38. Andersson RE, Lambe M. Incidence of appendicitis during pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1281-1285.

39. Moltubak E, Landerholm K, Blomberg M, et al. Major variation in the incidence of appendicitis before, during and after pregnancy: a population-based cohort study. World J Surg. 2020;44:2601-2608.

40. Abbasi N, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. Management and outcomes of acute appendicitis in pregnancy-population-based study of over 7000 cases. BJOG. 2014;121:1509-1514.

41. Dongarwar D, Taylor J, Ajewole V, et al. Trends in appendicitis among pregnant women, the risk for cardiac arrest, and maternal-fetal mortality. World J Surg. 2020;44:3999-4005.

42. Sachs A, Guglielminotti J, Miller R, et al. Risk factors and risk stratification for adverse obstetrical outcomes after appendectomy or cholecystectomy during pregnancy. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:436-441.

43. Joo JI, Park HC, Kim MJ, et al. Outcomes of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated appendicitis in pregnancy. Am J Med. 2017;130:1467-1469.

44. Lee SH, Lee JY, Choi YY, Lee JG. Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy for suspected appendicitis during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19:41.

45. Frountzas M, Nikolaou C, Stergios K, et al. Is the laparoscopic approach a safe choice for the management of acute appendicitis in pregnant women? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:235-248.

46. Di Saverio S, Podda M, De Simone B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:27.

47. Koberlein GC, Trout AT, Rigsby CK, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria suspected appendicitis-child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:S252-S263.

48. Maita S, Andersson B, Svensson JF, et al. Nonoperative treatment for nonperforated appendicitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:261-269.

49. Georgiou R, Eaton S, Stanton MP, et al. Efficacy and safety of nonoperative treatment for acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163003.

CASE

A 35-year-old man with a body mass index of 20 presented to the emergency department after 24 hours of abdominal pain that began in the periumbilical region and then migrated to the right lower quadrant. The pain was exacerbated during ambulation and was intense when the car transporting him to the hospital encountered bumps in the road. After his pain started, he had associated anorexia, followed by nausea and emesis. He reported fever and chills. On examination, his temperature was 100.8 °F (38.2 °C), and palpation of the right and left lower quadrants elicited right lower quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 14,000 cells/mcL with 85% neutrophils, C-reactive protein of 40 mg/L, and a negative urinalysis.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of abdominal pain resulting in the need for surgical treatment; lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6% to 7%.1 Appendicitis is caused by intraluminal obstruction in the appendix from enlarged lymphoid tissue or a fecalith. The obstruction leads to elevated intraluminal pressure due to persistent mucus and gas production by bacteria, ultimately leading to ischemia and perforation.1 Additionally, obstruction leads to bacterial overgrowth, most commonly colonic flora such as Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Streptococcus viridans, Enterococcus sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniaei.1,2

The following review provides a look at how 3 clinical scoring systems compare in the identification of acute appendicitis and details which imaging studies you should order—and when. But first, we’ll quickly detail the relevant physical findings and lab values that point to a diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Physical findings. The patient typically first experiences vague abdominal pain that then localizes to the right lower quadrant due to peritoneal inflammation. Anorexia and nausea typically follow the abdominal pain. On examination, the patient often appears ill and exhibits abdominal guarding due to peritonitis. Tachycardia and fever are common; however, the absence of either does not exclude appendicitis. Classically, on palpation, the patient will have pain at McBurney’s point (one-third the distance from the anterior iliac spine to the umbilicus). The exact point of maximal tenderness can differ because of the varying anatomy of the appendix (retrocecal, paracolic, pelvic, pre/post ileal, promontoric, or subcecal).1 Right lower quadrant pain, abdominal rigidity, and radiation of periumbilical pain to the right lower quadrant are the most accurate findings in adults to rule in appendicitis.3 For children, physical exam findings have the highest likelihood in predicting appendicitis and include a positive Obturator sign, positive Rovsing sign, or a positive Psoas sign, and absent or decreased bowel sounds.4

Laboratory studies can support a diagnosis of appendicitis but cannot exclude it. Leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance is present in 90% of cases.5 An elevated C-reactive protein level renders the highest diagnostic accuracy.5 Perform a pregnancy test for any woman of child-bearing age, to assist in the diagnosis and guide imaging choices for evaluation. Additional laboratory tests are not needed unless there are concerns about volume depletion.

Clinical scoring systems

Several clinical scoring systems (TABLE6-10) have been validated to aid clinicians in evaluating patients with possible appendicitis, to decrease unnecessary exposure to ionizing radiation from computed tomography (CT) scans, to identify and reassure patients with low likelihoods of appendicitis, and to conduct outpatient follow-up.

Continue to: The Alvarado score

The Alvarado score is the oldest scoring rule, developed in 1986; it entails 8 clinical and laboratory variables.6 Ebell et al altered the proposed cutoff values of the Alvarado score to be low risk (< 4), intermediate risk (4-8), and high risk (≥ 9), effectively improving the sensitivity and specificity rates.7

In a meta-analysis of the Alvarado score that included 42 studies of men, women, and children, the sensitivity for “ruling out” appendicitis with a cutoff of 5 points was 96% for men, 99% for women, and 99% for children.8 The accuracy of a high-risk score (> 7) for “ruling in” appendicitis was less with an overall specificity of 82%.8 The Alvarado score did seem to overestimate appendicitis in women in all score categories.8

The Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS) is similar to Alvarado and was prospectively validated in 1170 children in 2002 for more specific guidance in this age group.9 The PAS had excellent specificity in the study; those with a score of ≥ 6 had a high probability of appendicitis. In a study comparing Alvarado with PAS in 311 patients, insignificant differences were noted at a score of ≥ 7 for both tests (sensitivity 86% vs 89%, and specificity 59% vs 50%, respectively).11 No scoring system has been found to be sufficiently accurate for use in children 4 years of age and younger.12

The Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) Score was prospectively validated in 545 patients representing all age groups.10 Subsequently, in a larger prospective multicenter study of 3878 patients older than 5 years, the original cut points were altered, thereby improving test sensitivity and negative predictive value to 99% for those with low probability (0 to 3), and test specificity to 98% for those with high-probability (9 to 12).13 Compared with the Alvarado Score, the AIR Score has higher specificity for those in the high-probability range, and similar exclusion rates in the low-probability range.14

Caveats with clinical decision scores. These tools are accepted and often used. However, challenges that affect generalizability of study data include differences in patient selection for each study (undifferentiated abdominal pain vs appendicitis), prospective vs retrospective designs, and age and gender variations in the patient populations. Despite the numerous scoring systems developed, none can accurately be used to rule in appendicitis. They are best used to assist in ruling out appendicitis and to aid in deciding for or against imaging.

Continue to: A look at the imaging options

A look at the imaging options

Abdominal CT has sensitivity and specificity rates between 76% and 100% and 83% and 100%, respectively.15,20,21 Ultrasonography has sensitivity and specificity rates of 71% to 94% and 81% to 98%, respectively.15,20,21 Formal US is reliable to confirm appendicitis, but less so to rule out appendicitis. Special considerations for imagining in pregnant patients and children are discussed in a bit.

Timing of surgical consultation

Surgical consultation is paramount once the diagnosis of appendicitis is probable. Imaging is best obtained prior to surgical consultation to streamline evaluation and enhance decision- making. Typically, patients will be categorized as complicated or uncomplicated based on the presence or absence of perforation, a gangrenous appendix, an intra-abdominal abscess (IAA), or purulent peritonitis. Active continuous surgical involvement (co-management or assumption of care) is recommended in all cases of appendicitis, especially if nonoperative management is selected, given that some cases must convert to immediate operative treatment or may be selected for delayed future (interval) appendectomy.22

Management

Uncomplicated appendicitis

Prompt appendectomy has been the gold standard of care for uncomplicated acute appendicitis for 60 years. However, several studies have investigated an antibiotic-based strategy rather than surgical treatment for uncomplicated appendicitis.

Antibiotics vs appendectomy. In 2020, the CODA Collaborative published a randomized trial comparing a 10-day course of antibiotics with appendectomy in patients with uncomplicated appendicitis. In this multicenter study based in the United States, 1552 patients 18 years of age or older were randomized to receive antibiotics or undergo appendectomy (95% performed laparoscopically). The antibiotic treatment consisted of at least 24 hours of IV antibiotics, with or without admission to the hospital. Antibiotic choice was individualized according to guidelines for intra-abdominal infection published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, with the most common IV medications being ertapenem, cefoxitin, or metronidazole plus one of the following: ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or levofloxacin. For the remaining 10 days, oral metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin or cefdinir were used.22

Continue to: The primary endpoint...

The primary endpoint was the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, with secondary outcomes including appendectomy in the antibiotics group and complications through 90 days. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, sepsis, peritonitis, recurrent appendicitis, severe phlegmon on imaging, or evidence of neoplasm.22

Antibiotics were noninferior to appendectomy for the 30-day study. However, antibiotics failed in 29%, who then proceeded to appendectomy by 90 days; these patients also accounted for 41% of those with an appendicolith. Overall complications were more common in the antibiotics group than in the appendectomy group (8.1 vs 3.5 per 100 participants; 95% CI, 1.3-3.98). Also more common in the antibiotic group were serious adverse events (4 vs 3 per 100 participants; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% CI, 0.67-2.50). The presence of an appendicolith in the antibiotics group increased the conversion risk to appendectomy, as well as adverse events risk.22

The takeaway. Antibiotic treatment is a noninferior method to treat acute uncomplicated appendicitis. However, the informed consent process is important, given the ~30% failure rate. Patient factors such as continued access to care should help inform the decision.

Two main surgical approaches exist for appendectomy: open and minimally invasive. At this time, the minimally invasive options include laparoscopic, single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), and robotic appendectomy. A study comparing cost, availability, or complications of these options has not been conducted at this time.

A large Cochrane review of 67 studies examining open vs laparoscopic appendectomy in adults and children completed in 2018 revealed that the laparoscopic approach reduced early postoperative pain intensity and led to a shorter hospital stay, earlier return to work or usual activities, and a decrease in wound infections.23 The odds of IAA occurring with laparoscopic appendectomy increased by 65% compared with an open procedure; however, postoperative bowel obstruction and incisional hernias were less likely to occur.23 Additionally, following laparoscopic surgery, postoperative bowel obstruction and incisional hernias are less likely to occur. The laparoscopic approach is preferred due to overall increased patient satisfaction and a reduction in most, if not all, complications.

Continue to: Complicated appendicitis

Complicated appendicitis

Excluding patients with severe sepsis or purulent peritonitis requiring resuscitation and immediate surgical intervention of intra-abdominal infection, the approach to patients with complicated appendicitis varies between aggressive surgical intervention and nonoperative management.

In a 2007 meta-analysis reviewing nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess/phlegmon, immediate surgery was associated with higher morbidity.24 Within the nonoperative management group 7.2% (CI, 4.0-10.5) required surgical intervention and 19.7% (CI, 11.0-28.3) required abscess drainage. Malignant disease was detected in 1.2% (CI, 0.6-1.7).24 Small subsequent studies concluded different results.25

Ultimately, the 2015 European Association of Endoscopic Surgery guidelines recommend a new systematic review; but with current data, initial nonoperative management is preferred.15 After initial nonoperative treatment, the only benefits from interval appendectomy are identification of an underlying malignancy (6% to 20%) and mitigating the risk of recurrent appendicitis (5% to 44%).15,25-30

Multiple single institutional series found increased neoplasm incidence (9% to 20%) in complicated appendicitis in patients 40 years and older.26-30 Prior to interval appendectomy in patients 45 years and older, ensuring they have an up-to-date screening colonoscopy is important. This is in line with 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force (Grade “B” recommendation), 2018 American Cancer Society (qualified recommendation), and 2021 American College of Gastroenterology (conditional recommendation) guidelines for colorectal cancer screening to start at age 45 in average-risk patients.31 Patients younger than 45 can consider screening through shared decision-making.

Special populations

Pregnant patients

In pregnancy, challenges exist with the presence of traditional signs and symptoms of appendicitis, with the most predictive sign being a WBC count higher than 18,000.32 The American College of Radiology’s (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria recommend US as the imaging modality of choice in pregnancy, with MRI as the best option when US is inconclusive.33 Two meta-analyses demonstrated high sensitivity (91.8%-96.6%) and specificity (95.9%-97.9%) of MRI in diagnosing appendicitis.34,35 CT scan is not the preferred initial imagining modality in pregnancy unless urgent information is needed and other modalities are insufficient or unavailable.36

Continue to: The most common...

The most common nonobstetric surgical intervention during pregnancy is appendectomy, at a rate of 6.3/10,000 person-years, which increases to 9.9/10,000 in the postpartum period.37 Two large population studies demonstrate the rate of appendicitis varies over the course of pregnancy, with the lowest rates in the third trimester,38,39 and a significant rebound lasting for 2 years postpartum.39 Peritonitis, septic shock, pneumonia, postoperative infection, and longer hospital stays occur more frequently in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women with appendicitis.40 Fetal loss is higher in the first trimester.32

In a 14-year review of 63,145 appendicitis cases, an increased risk of fetal loss and maternal death was noted across ages and ethnicities, with the largest risk of maternal death occurring in Hispanics and fetal death in non-Hispanic Blacks.41 In a large study of 1018 adverse events after appendectomy or cholecystectomy, the 3 most common events were preterm delivery (35.4%), preterm labor without preterm delivery (26.4%), and miscarriage (25.7%).42 The surgery itself was not a major risk factor for adverse events. Major risk factors included cervical incompetence (odds ratio [OR] = 24.3), preterm labor in current pregnancy (OR = 18.3), and presence of vulvovaginitis (OR = 5.2).42

Nonoperative management in pregnancy is not recommended; only 1 prospective trial has been done, with 20 patients, showing a 25% failure rate.43 Two meta-analyses published in 2019 highlight the potential increase of fetal loss with laparoscopic approaches to appendectomy.44,45 However, recently published literature demonstrates no significant maternal-fetal morbidity. Current guidelines of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons agree that laparoscopy is the operative choice in pregnancy.36

Children

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in children.4 Physical exam findings and laboratory results are not classic in this population, obtaining an accurate history can be challenging, and results of clinical scoring systems can be inconclusive.4 Additional serum biomarkers, procalcitonin and calprotectin, are gaining evidence for use in improving scoring systems to refine low-risk groups. Unavailability of timely, reliable biomarker testing in rural practice locations limits definitive recommendations at this time.46 ACR recommends no imaging in a pediatric patient whose risk of having appendicitis is low based on any of several scoring systems.47 For those assessed as having higher risk, US is the recommended initial modality,with CT with IV contrast or MRI without contrast equally recommended if the US is equivocal.47

Despite promising data from trials of nonoperative treatment for adults with appendicitis, no definitive evidence and recommendations are available for children. Two systematic reviews show nonoperative treatment is safe, with an efficacy rate of 76% to 82% at long-term follow-up,48,49 although the success of antibiotic regimens varies. Within the nonoperative treatment group, 16% of patients had appendectomy during the follow-up period, which varied from 8 weeks to 4 years.48 A randomized controlled trial is needed for final guidance.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

The patient had an Alvarado score of 9 (high probability) and an AIR score of 6 (intermediate probability). A CT with IV contrast showed a 9-mm fluid-filled appendix with periappendiceal fluid. During surgical consultation, he was offered laparoscopic appendectomy or nonoperative treatment with antibiotics. He opted for a preoperative dose of piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV and laparoscopic appendectomy. The patient was discharged home 6 hours after his procedure.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Servey, MD, MHPE, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected]

CASE

A 35-year-old man with a body mass index of 20 presented to the emergency department after 24 hours of abdominal pain that began in the periumbilical region and then migrated to the right lower quadrant. The pain was exacerbated during ambulation and was intense when the car transporting him to the hospital encountered bumps in the road. After his pain started, he had associated anorexia, followed by nausea and emesis. He reported fever and chills. On examination, his temperature was 100.8 °F (38.2 °C), and palpation of the right and left lower quadrants elicited right lower quadrant pain. Laboratory evaluation revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 14,000 cells/mcL with 85% neutrophils, C-reactive protein of 40 mg/L, and a negative urinalysis.

How would you proceed with this patient?

Acute appendicitis is the most common cause of abdominal pain resulting in the need for surgical treatment; lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6% to 7%.1 Appendicitis is caused by intraluminal obstruction in the appendix from enlarged lymphoid tissue or a fecalith. The obstruction leads to elevated intraluminal pressure due to persistent mucus and gas production by bacteria, ultimately leading to ischemia and perforation.1 Additionally, obstruction leads to bacterial overgrowth, most commonly colonic flora such as Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Streptococcus viridans, Enterococcus sp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniaei.1,2

The following review provides a look at how 3 clinical scoring systems compare in the identification of acute appendicitis and details which imaging studies you should order—and when. But first, we’ll quickly detail the relevant physical findings and lab values that point to a diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Physical findings. The patient typically first experiences vague abdominal pain that then localizes to the right lower quadrant due to peritoneal inflammation. Anorexia and nausea typically follow the abdominal pain. On examination, the patient often appears ill and exhibits abdominal guarding due to peritonitis. Tachycardia and fever are common; however, the absence of either does not exclude appendicitis. Classically, on palpation, the patient will have pain at McBurney’s point (one-third the distance from the anterior iliac spine to the umbilicus). The exact point of maximal tenderness can differ because of the varying anatomy of the appendix (retrocecal, paracolic, pelvic, pre/post ileal, promontoric, or subcecal).1 Right lower quadrant pain, abdominal rigidity, and radiation of periumbilical pain to the right lower quadrant are the most accurate findings in adults to rule in appendicitis.3 For children, physical exam findings have the highest likelihood in predicting appendicitis and include a positive Obturator sign, positive Rovsing sign, or a positive Psoas sign, and absent or decreased bowel sounds.4

Laboratory studies can support a diagnosis of appendicitis but cannot exclude it. Leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance is present in 90% of cases.5 An elevated C-reactive protein level renders the highest diagnostic accuracy.5 Perform a pregnancy test for any woman of child-bearing age, to assist in the diagnosis and guide imaging choices for evaluation. Additional laboratory tests are not needed unless there are concerns about volume depletion.

Clinical scoring systems

Several clinical scoring systems (TABLE6-10) have been validated to aid clinicians in evaluating patients with possible appendicitis, to decrease unnecessary exposure to ionizing radiation from computed tomography (CT) scans, to identify and reassure patients with low likelihoods of appendicitis, and to conduct outpatient follow-up.

Continue to: The Alvarado score

The Alvarado score is the oldest scoring rule, developed in 1986; it entails 8 clinical and laboratory variables.6 Ebell et al altered the proposed cutoff values of the Alvarado score to be low risk (< 4), intermediate risk (4-8), and high risk (≥ 9), effectively improving the sensitivity and specificity rates.7

In a meta-analysis of the Alvarado score that included 42 studies of men, women, and children, the sensitivity for “ruling out” appendicitis with a cutoff of 5 points was 96% for men, 99% for women, and 99% for children.8 The accuracy of a high-risk score (> 7) for “ruling in” appendicitis was less with an overall specificity of 82%.8 The Alvarado score did seem to overestimate appendicitis in women in all score categories.8

The Pediatric Appendicitis Score (PAS) is similar to Alvarado and was prospectively validated in 1170 children in 2002 for more specific guidance in this age group.9 The PAS had excellent specificity in the study; those with a score of ≥ 6 had a high probability of appendicitis. In a study comparing Alvarado with PAS in 311 patients, insignificant differences were noted at a score of ≥ 7 for both tests (sensitivity 86% vs 89%, and specificity 59% vs 50%, respectively).11 No scoring system has been found to be sufficiently accurate for use in children 4 years of age and younger.12

The Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) Score was prospectively validated in 545 patients representing all age groups.10 Subsequently, in a larger prospective multicenter study of 3878 patients older than 5 years, the original cut points were altered, thereby improving test sensitivity and negative predictive value to 99% for those with low probability (0 to 3), and test specificity to 98% for those with high-probability (9 to 12).13 Compared with the Alvarado Score, the AIR Score has higher specificity for those in the high-probability range, and similar exclusion rates in the low-probability range.14

Caveats with clinical decision scores. These tools are accepted and often used. However, challenges that affect generalizability of study data include differences in patient selection for each study (undifferentiated abdominal pain vs appendicitis), prospective vs retrospective designs, and age and gender variations in the patient populations. Despite the numerous scoring systems developed, none can accurately be used to rule in appendicitis. They are best used to assist in ruling out appendicitis and to aid in deciding for or against imaging.

Continue to: A look at the imaging options

A look at the imaging options

Abdominal CT has sensitivity and specificity rates between 76% and 100% and 83% and 100%, respectively.15,20,21 Ultrasonography has sensitivity and specificity rates of 71% to 94% and 81% to 98%, respectively.15,20,21 Formal US is reliable to confirm appendicitis, but less so to rule out appendicitis. Special considerations for imagining in pregnant patients and children are discussed in a bit.

Timing of surgical consultation

Surgical consultation is paramount once the diagnosis of appendicitis is probable. Imaging is best obtained prior to surgical consultation to streamline evaluation and enhance decision- making. Typically, patients will be categorized as complicated or uncomplicated based on the presence or absence of perforation, a gangrenous appendix, an intra-abdominal abscess (IAA), or purulent peritonitis. Active continuous surgical involvement (co-management or assumption of care) is recommended in all cases of appendicitis, especially if nonoperative management is selected, given that some cases must convert to immediate operative treatment or may be selected for delayed future (interval) appendectomy.22

Management

Uncomplicated appendicitis

Prompt appendectomy has been the gold standard of care for uncomplicated acute appendicitis for 60 years. However, several studies have investigated an antibiotic-based strategy rather than surgical treatment for uncomplicated appendicitis.

Antibiotics vs appendectomy. In 2020, the CODA Collaborative published a randomized trial comparing a 10-day course of antibiotics with appendectomy in patients with uncomplicated appendicitis. In this multicenter study based in the United States, 1552 patients 18 years of age or older were randomized to receive antibiotics or undergo appendectomy (95% performed laparoscopically). The antibiotic treatment consisted of at least 24 hours of IV antibiotics, with or without admission to the hospital. Antibiotic choice was individualized according to guidelines for intra-abdominal infection published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, with the most common IV medications being ertapenem, cefoxitin, or metronidazole plus one of the following: ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or levofloxacin. For the remaining 10 days, oral metronidazole plus ciprofloxacin or cefdinir were used.22

Continue to: The primary endpoint...

The primary endpoint was the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire, with secondary outcomes including appendectomy in the antibiotics group and complications through 90 days. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, sepsis, peritonitis, recurrent appendicitis, severe phlegmon on imaging, or evidence of neoplasm.22

Antibiotics were noninferior to appendectomy for the 30-day study. However, antibiotics failed in 29%, who then proceeded to appendectomy by 90 days; these patients also accounted for 41% of those with an appendicolith. Overall complications were more common in the antibiotics group than in the appendectomy group (8.1 vs 3.5 per 100 participants; 95% CI, 1.3-3.98). Also more common in the antibiotic group were serious adverse events (4 vs 3 per 100 participants; hazard ratio [HR] = 1.29; 95% CI, 0.67-2.50). The presence of an appendicolith in the antibiotics group increased the conversion risk to appendectomy, as well as adverse events risk.22

The takeaway. Antibiotic treatment is a noninferior method to treat acute uncomplicated appendicitis. However, the informed consent process is important, given the ~30% failure rate. Patient factors such as continued access to care should help inform the decision.

Two main surgical approaches exist for appendectomy: open and minimally invasive. At this time, the minimally invasive options include laparoscopic, single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS), and robotic appendectomy. A study comparing cost, availability, or complications of these options has not been conducted at this time.

A large Cochrane review of 67 studies examining open vs laparoscopic appendectomy in adults and children completed in 2018 revealed that the laparoscopic approach reduced early postoperative pain intensity and led to a shorter hospital stay, earlier return to work or usual activities, and a decrease in wound infections.23 The odds of IAA occurring with laparoscopic appendectomy increased by 65% compared with an open procedure; however, postoperative bowel obstruction and incisional hernias were less likely to occur.23 Additionally, following laparoscopic surgery, postoperative bowel obstruction and incisional hernias are less likely to occur. The laparoscopic approach is preferred due to overall increased patient satisfaction and a reduction in most, if not all, complications.

Continue to: Complicated appendicitis

Complicated appendicitis

Excluding patients with severe sepsis or purulent peritonitis requiring resuscitation and immediate surgical intervention of intra-abdominal infection, the approach to patients with complicated appendicitis varies between aggressive surgical intervention and nonoperative management.

In a 2007 meta-analysis reviewing nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess/phlegmon, immediate surgery was associated with higher morbidity.24 Within the nonoperative management group 7.2% (CI, 4.0-10.5) required surgical intervention and 19.7% (CI, 11.0-28.3) required abscess drainage. Malignant disease was detected in 1.2% (CI, 0.6-1.7).24 Small subsequent studies concluded different results.25

Ultimately, the 2015 European Association of Endoscopic Surgery guidelines recommend a new systematic review; but with current data, initial nonoperative management is preferred.15 After initial nonoperative treatment, the only benefits from interval appendectomy are identification of an underlying malignancy (6% to 20%) and mitigating the risk of recurrent appendicitis (5% to 44%).15,25-30

Multiple single institutional series found increased neoplasm incidence (9% to 20%) in complicated appendicitis in patients 40 years and older.26-30 Prior to interval appendectomy in patients 45 years and older, ensuring they have an up-to-date screening colonoscopy is important. This is in line with 2021 US Preventive Services Task Force (Grade “B” recommendation), 2018 American Cancer Society (qualified recommendation), and 2021 American College of Gastroenterology (conditional recommendation) guidelines for colorectal cancer screening to start at age 45 in average-risk patients.31 Patients younger than 45 can consider screening through shared decision-making.

Special populations

Pregnant patients

In pregnancy, challenges exist with the presence of traditional signs and symptoms of appendicitis, with the most predictive sign being a WBC count higher than 18,000.32 The American College of Radiology’s (ACR) Appropriateness Criteria recommend US as the imaging modality of choice in pregnancy, with MRI as the best option when US is inconclusive.33 Two meta-analyses demonstrated high sensitivity (91.8%-96.6%) and specificity (95.9%-97.9%) of MRI in diagnosing appendicitis.34,35 CT scan is not the preferred initial imagining modality in pregnancy unless urgent information is needed and other modalities are insufficient or unavailable.36

Continue to: The most common...

The most common nonobstetric surgical intervention during pregnancy is appendectomy, at a rate of 6.3/10,000 person-years, which increases to 9.9/10,000 in the postpartum period.37 Two large population studies demonstrate the rate of appendicitis varies over the course of pregnancy, with the lowest rates in the third trimester,38,39 and a significant rebound lasting for 2 years postpartum.39 Peritonitis, septic shock, pneumonia, postoperative infection, and longer hospital stays occur more frequently in pregnant women than in nonpregnant women with appendicitis.40 Fetal loss is higher in the first trimester.32

In a 14-year review of 63,145 appendicitis cases, an increased risk of fetal loss and maternal death was noted across ages and ethnicities, with the largest risk of maternal death occurring in Hispanics and fetal death in non-Hispanic Blacks.41 In a large study of 1018 adverse events after appendectomy or cholecystectomy, the 3 most common events were preterm delivery (35.4%), preterm labor without preterm delivery (26.4%), and miscarriage (25.7%).42 The surgery itself was not a major risk factor for adverse events. Major risk factors included cervical incompetence (odds ratio [OR] = 24.3), preterm labor in current pregnancy (OR = 18.3), and presence of vulvovaginitis (OR = 5.2).42

Nonoperative management in pregnancy is not recommended; only 1 prospective trial has been done, with 20 patients, showing a 25% failure rate.43 Two meta-analyses published in 2019 highlight the potential increase of fetal loss with laparoscopic approaches to appendectomy.44,45 However, recently published literature demonstrates no significant maternal-fetal morbidity. Current guidelines of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons agree that laparoscopy is the operative choice in pregnancy.36

Children

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in children.4 Physical exam findings and laboratory results are not classic in this population, obtaining an accurate history can be challenging, and results of clinical scoring systems can be inconclusive.4 Additional serum biomarkers, procalcitonin and calprotectin, are gaining evidence for use in improving scoring systems to refine low-risk groups. Unavailability of timely, reliable biomarker testing in rural practice locations limits definitive recommendations at this time.46 ACR recommends no imaging in a pediatric patient whose risk of having appendicitis is low based on any of several scoring systems.47 For those assessed as having higher risk, US is the recommended initial modality,with CT with IV contrast or MRI without contrast equally recommended if the US is equivocal.47

Despite promising data from trials of nonoperative treatment for adults with appendicitis, no definitive evidence and recommendations are available for children. Two systematic reviews show nonoperative treatment is safe, with an efficacy rate of 76% to 82% at long-term follow-up,48,49 although the success of antibiotic regimens varies. Within the nonoperative treatment group, 16% of patients had appendectomy during the follow-up period, which varied from 8 weeks to 4 years.48 A randomized controlled trial is needed for final guidance.

Continue to: CASE

CASE

The patient had an Alvarado score of 9 (high probability) and an AIR score of 6 (intermediate probability). A CT with IV contrast showed a 9-mm fluid-filled appendix with periappendiceal fluid. During surgical consultation, he was offered laparoscopic appendectomy or nonoperative treatment with antibiotics. He opted for a preoperative dose of piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 g IV and laparoscopic appendectomy. The patient was discharged home 6 hours after his procedure.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Servey, MD, MHPE, 4301 Jones Bridge Road, Bethesda, MD 20814; [email protected]

1. Prystowsky JB, Pugh CM, Nagle AP. Current problems in surgery. Appendicitis. Curr Probl Surg. 2005;42:688-742.

2. Song DW, Park BK, Suh SW, et al. Bacterial culture and antibiotic susceptibility in patients with acute appendicitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:441-447.

3. Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA. 1996;276:1589-1594.

4. Benabbas R, Hanna M, Shah J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and point-of-care ultrasound for pediatric acute appendicitis in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:523-551.

5. Andersson RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28-37.

6. Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557-564.

7. Ebell MH, Shinholser J. What are the most clinically useful cutoffs for the Alvarado and Pediatric Appendicitis Scores? A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:365-372.e2.

8. Ohle R, O’Reilly F, O’Brien KK, et al. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:139.

9. Samuel M. Pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:877-881.

10. Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843-1849.

11. Pogorelić Z, Rak S, Mrklić I, et al. Prospective validation of Alvarado score and Pediatric Appendicitis Score for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:164-168.

12. Rassi R, Muse F, Sánchez-Martínez J, et al. Diagnostic value of clinical prediction scores for acute appendicitis in children younger than 4 years. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2021. [Online ahead of print]

13. Andersson M, Kolodziej B, Andersson RE. Validation of the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) score. World J Surg. 2021;45:2081-2091.

14. Kollár D, McCartan DP, Bourke M, et al. Predicting acute appendicitis? A comparison of the Alvarado score, the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score and clinical assessment. World J Surg. 2015;39:104-109.

15. Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis. EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4668-4690.

16. Matthew Fields J, Davis J, Alsup C, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasonography for diagnosing acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1124-1136.

17. Sharif S, Skitch S, Vlahaki D, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound to diagnose appendicitis in a Canadian emergency department. CJEM. 2018;20:732-735.

18. Doniger SJ, Kornblith A. Point-of-care ultrasound integrated into a staged diagnostic algorithm for pediatric appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:109-115.

19. Menon N, Kumar S, Keeler B, et al. A systematic review of point-of-care abdominal ultrasound scans performed by general surgeons. Surgeon. 2021. [Online ahead of print]

20. Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, et al. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241:83-94.

21. van Randen A, Laméris W, van Es HW, et al. A comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and computed tomography in common diagnoses causing acute abdominal pain. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1535-1545.

22. Flum DR, Davidson GH, Monsell SE, et al. A randomized trial comparing antibiotics with appendectomy for appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1907-1919.

23. Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD001546.

24. Andersson RE, Petzold MG. Nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:741-748.

25. Deelder JD, Richir MC, Schoorl T, et al. How to treat an appendiceal inflammatory mass: operatively or nonoperatively? J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:641-645.

26. Carpenter SG, Chapital AB, Merritt MV, et al. Increased risk of neoplasm in appendicitis treated with interval appendectomy: single-institution experience and literature review. Am Surg. 2012;78:339-343.

27. Hayes D, Reiter S, Hagen E, et al. Is interval appendectomy really needed? A closer look at neoplasm rates in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy after complicated appendicitis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:3855-3860.

28. Peltrini R, Cantoni V, Green R, et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm after interval appendectomy for complicated appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2021. [Online ahead of print.]

29. Mällinen J, Rautio T, Grönroos J, et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm in periappendicular abscess in patients treated with interval appendectomy vs follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging: 1-year outcomes of the peri-appendicitis acuta randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:200-207.

30. Son J, Park YJ, Lee SR, et al. Increased risk of neoplasms in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy. Ann Coloproctol. 2020;36:311-315.

31. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977.

32. Theilen LH, Mellnick VM, Shanks AL, et al. Acute appendicitis in pregnancy: predictive clinical factors and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:523-528.

33. Garcia EM, Camacho MA, Karolyi DR, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria right lower quadrant pain-suspected appendicitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:S373-s387.

34. Kave M, Parooie F, Salarzaei M. Pregnancy and appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the clinical use of MRI in diagnosis of appendicitis in pregnant women. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:37.

35. Repplinger MD, Levy JF, Peethumnongsin E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of MRI to diagnose appendicitis in the general population. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:1346-1354.

36. Pearl JP, Price RR, Tonkin AE, et al. SAGES guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3767-3782.

37. Zingone F, Sultan AA, Humes DJ, et al. Risk of acute appendicitis in and around pregnancy: a population-based cohort study from England. Ann Surg. 2015;261:332-337.

38. Andersson RE, Lambe M. Incidence of appendicitis during pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1281-1285.

39. Moltubak E, Landerholm K, Blomberg M, et al. Major variation in the incidence of appendicitis before, during and after pregnancy: a population-based cohort study. World J Surg. 2020;44:2601-2608.

40. Abbasi N, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. Management and outcomes of acute appendicitis in pregnancy-population-based study of over 7000 cases. BJOG. 2014;121:1509-1514.

41. Dongarwar D, Taylor J, Ajewole V, et al. Trends in appendicitis among pregnant women, the risk for cardiac arrest, and maternal-fetal mortality. World J Surg. 2020;44:3999-4005.

42. Sachs A, Guglielminotti J, Miller R, et al. Risk factors and risk stratification for adverse obstetrical outcomes after appendectomy or cholecystectomy during pregnancy. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:436-441.

43. Joo JI, Park HC, Kim MJ, et al. Outcomes of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated appendicitis in pregnancy. Am J Med. 2017;130:1467-1469.

44. Lee SH, Lee JY, Choi YY, Lee JG. Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy for suspected appendicitis during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19:41.

45. Frountzas M, Nikolaou C, Stergios K, et al. Is the laparoscopic approach a safe choice for the management of acute appendicitis in pregnant women? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:235-248.

46. Di Saverio S, Podda M, De Simone B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:27.

47. Koberlein GC, Trout AT, Rigsby CK, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria suspected appendicitis-child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:S252-S263.

48. Maita S, Andersson B, Svensson JF, et al. Nonoperative treatment for nonperforated appendicitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:261-269.

49. Georgiou R, Eaton S, Stanton MP, et al. Efficacy and safety of nonoperative treatment for acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163003.

1. Prystowsky JB, Pugh CM, Nagle AP. Current problems in surgery. Appendicitis. Curr Probl Surg. 2005;42:688-742.

2. Song DW, Park BK, Suh SW, et al. Bacterial culture and antibiotic susceptibility in patients with acute appendicitis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:441-447.

3. Wagner JM, McKinney WP, Carpenter JL. Does this patient have appendicitis? JAMA. 1996;276:1589-1594.

4. Benabbas R, Hanna M, Shah J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and point-of-care ultrasound for pediatric acute appendicitis in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:523-551.

5. Andersson RE. Meta-analysis of the clinical and laboratory diagnosis of appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2004;91:28-37.

6. Alvarado A. A practical score for the early diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Ann Emerg Med. 1986;15:557-564.

7. Ebell MH, Shinholser J. What are the most clinically useful cutoffs for the Alvarado and Pediatric Appendicitis Scores? A systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:365-372.e2.

8. Ohle R, O’Reilly F, O’Brien KK, et al. The Alvarado score for predicting acute appendicitis: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:139.

9. Samuel M. Pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:877-881.

10. Andersson M, Andersson RE. The appendicitis inflammatory response score: a tool for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis that outperforms the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2008;32:1843-1849.

11. Pogorelić Z, Rak S, Mrklić I, et al. Prospective validation of Alvarado score and Pediatric Appendicitis Score for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:164-168.

12. Rassi R, Muse F, Sánchez-Martínez J, et al. Diagnostic value of clinical prediction scores for acute appendicitis in children younger than 4 years. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2021. [Online ahead of print]

13. Andersson M, Kolodziej B, Andersson RE. Validation of the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response (AIR) score. World J Surg. 2021;45:2081-2091.

14. Kollár D, McCartan DP, Bourke M, et al. Predicting acute appendicitis? A comparison of the Alvarado score, the Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score and clinical assessment. World J Surg. 2015;39:104-109.

15. Gorter RR, Eker HH, Gorter-Stam MA, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute appendicitis. EAES consensus development conference 2015. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4668-4690.

16. Matthew Fields J, Davis J, Alsup C, et al. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasonography for diagnosing acute appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24:1124-1136.

17. Sharif S, Skitch S, Vlahaki D, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound to diagnose appendicitis in a Canadian emergency department. CJEM. 2018;20:732-735.

18. Doniger SJ, Kornblith A. Point-of-care ultrasound integrated into a staged diagnostic algorithm for pediatric appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34:109-115.

19. Menon N, Kumar S, Keeler B, et al. A systematic review of point-of-care abdominal ultrasound scans performed by general surgeons. Surgeon. 2021. [Online ahead of print]

20. Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, et al. US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology. 2006;241:83-94.

21. van Randen A, Laméris W, van Es HW, et al. A comparison of the accuracy of ultrasound and computed tomography in common diagnoses causing acute abdominal pain. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:1535-1545.

22. Flum DR, Davidson GH, Monsell SE, et al. A randomized trial comparing antibiotics with appendectomy for appendicitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1907-1919.

23. Jaschinski T, Mosch CG, Eikermann M, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;11:CD001546.

24. Andersson RE, Petzold MG. Nonsurgical treatment of appendiceal abscess or phlegmon: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2007;246:741-748.

25. Deelder JD, Richir MC, Schoorl T, et al. How to treat an appendiceal inflammatory mass: operatively or nonoperatively? J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:641-645.

26. Carpenter SG, Chapital AB, Merritt MV, et al. Increased risk of neoplasm in appendicitis treated with interval appendectomy: single-institution experience and literature review. Am Surg. 2012;78:339-343.

27. Hayes D, Reiter S, Hagen E, et al. Is interval appendectomy really needed? A closer look at neoplasm rates in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy after complicated appendicitis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:3855-3860.

28. Peltrini R, Cantoni V, Green R, et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm after interval appendectomy for complicated appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgeon. 2021. [Online ahead of print.]

29. Mällinen J, Rautio T, Grönroos J, et al. Risk of appendiceal neoplasm in periappendicular abscess in patients treated with interval appendectomy vs follow-up with magnetic resonance imaging: 1-year outcomes of the peri-appendicitis acuta randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:200-207.

30. Son J, Park YJ, Lee SR, et al. Increased risk of neoplasms in adult patients undergoing interval appendectomy. Ann Coloproctol. 2020;36:311-315.

31. Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325:1965-1977.

32. Theilen LH, Mellnick VM, Shanks AL, et al. Acute appendicitis in pregnancy: predictive clinical factors and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2017;34:523-528.

33. Garcia EM, Camacho MA, Karolyi DR, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria right lower quadrant pain-suspected appendicitis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15:S373-s387.

34. Kave M, Parooie F, Salarzaei M. Pregnancy and appendicitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the clinical use of MRI in diagnosis of appendicitis in pregnant women. World J Emerg Surg. 2019;14:37.

35. Repplinger MD, Levy JF, Peethumnongsin E, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the accuracy of MRI to diagnose appendicitis in the general population. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;43:1346-1354.

36. Pearl JP, Price RR, Tonkin AE, et al. SAGES guidelines for the use of laparoscopy during pregnancy. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3767-3782.

37. Zingone F, Sultan AA, Humes DJ, et al. Risk of acute appendicitis in and around pregnancy: a population-based cohort study from England. Ann Surg. 2015;261:332-337.

38. Andersson RE, Lambe M. Incidence of appendicitis during pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1281-1285.

39. Moltubak E, Landerholm K, Blomberg M, et al. Major variation in the incidence of appendicitis before, during and after pregnancy: a population-based cohort study. World J Surg. 2020;44:2601-2608.

40. Abbasi N, Patenaude V, Abenhaim HA. Management and outcomes of acute appendicitis in pregnancy-population-based study of over 7000 cases. BJOG. 2014;121:1509-1514.

41. Dongarwar D, Taylor J, Ajewole V, et al. Trends in appendicitis among pregnant women, the risk for cardiac arrest, and maternal-fetal mortality. World J Surg. 2020;44:3999-4005.

42. Sachs A, Guglielminotti J, Miller R, et al. Risk factors and risk stratification for adverse obstetrical outcomes after appendectomy or cholecystectomy during pregnancy. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:436-441.

43. Joo JI, Park HC, Kim MJ, et al. Outcomes of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated appendicitis in pregnancy. Am J Med. 2017;130:1467-1469.

44. Lee SH, Lee JY, Choi YY, Lee JG. Laparoscopic appendectomy versus open appendectomy for suspected appendicitis during pregnancy: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. BMC Surg. 2019;19:41.

45. Frountzas M, Nikolaou C, Stergios K, et al. Is the laparoscopic approach a safe choice for the management of acute appendicitis in pregnant women? A meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2019;101:235-248.

46. Di Saverio S, Podda M, De Simone B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:27.

47. Koberlein GC, Trout AT, Rigsby CK, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria suspected appendicitis-child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:S252-S263.

48. Maita S, Andersson B, Svensson JF, et al. Nonoperative treatment for nonperforated appendicitis in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2020;36:261-269.

49. Georgiou R, Eaton S, Stanton MP, et al. Efficacy and safety of nonoperative treatment for acute appendicitis: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20163003.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Use the Alvarado Score, Pediatric Appendicitis Score, or Appendicitis Inflammatory Response Score to help rule out appendicitis and thereby reduce unnecessary imaging. A

› Choose ultrasound first as the imaging procedure for children and pregnant women, followed by magnetic resonance imaging if needed, to reduce ionizing radiation in these populations. B

› Consider an antibiotic-based strategy under the care of a surgeon in lieu of immediate surgery for uncomplicated appendicitis. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence