User login

New single-button blood glucose monitor available in U.S.

The POGO Automatic Blood Glucose Monitoring System (Intuity Medical) has been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for people with diabetes aged 13 years and older.

It contains a 10-test cartridge, and once loaded and the monitor is turned on, the user only has to press their finger on a button to activate POGO Automatic, which then does all the work of lancing and blood collection, followed by a 4-second countdown and a result. Users only need to carry the monitor and not separate lancets or strips.

An app called Patterns is available for iOS and Android that allows the results from the device to automatically sync via Bluetooth. It visually presents glucose trends and enables data sharing with health care providers.

“We know that people with diabetes are more effective at managing their diabetes when they regularly check their blood glucose and use the information to take action,” said Daniel Einhorn, MD, medical director of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, president of Diabetes and Endocrine Associates, and chairperson of the Intuity Medical Scientific Advisory Board, in a company statement.

“My patients and millions of others with diabetes have struggled for decades with the burden of checking their glucose because it’s complicated, there’s a lot to carry around, and it’s intrusive,” he added. “What they’ve needed is a simple, quick, and truly discreet way to check their blood glucose, so they’ll actually do it.”

How does POGO compare with CGM?

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), such as the Abbott FreeStyle Libre, Dexcom G6, and Eversense implant, are increasingly employed by people with type 1 diabetes, and some with type 2 diabetes, to keep a close eye on their blood glucose levels.

Asked how the POGO device compares with CGM systems, Intuity Chief Commercial Officer Dean Zikria said: “While [CGM] is certainly an important option for a subset of people with diabetes, CGM is a very different technology, requiring a user to wear a sensor and transmitter on their body.”

“Patients also need to obtain a prescription in order to use CGM.”

“Conversely, POGO Automatic is available with or without a prescription. POGO Automatic also gives people who do not want to wear a device on their body a new choice other than traditional blood glucose monitoring,” Mr. Zikria added.

The POGO system is available at U.S. pharmacies, including CVS and Walgreens, and can also be purchased online.

The device costs $68 from the company website and a pack of 5 cartridges (each containing 10 tests, with an aim of people performing 1-2 tests per day) costs a further $32 as a one-off, or $32 per month as a subscription.

The product is also eligible for purchase using Flexible Spending Accounts and Health Savings Accounts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The POGO Automatic Blood Glucose Monitoring System (Intuity Medical) has been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for people with diabetes aged 13 years and older.

It contains a 10-test cartridge, and once loaded and the monitor is turned on, the user only has to press their finger on a button to activate POGO Automatic, which then does all the work of lancing and blood collection, followed by a 4-second countdown and a result. Users only need to carry the monitor and not separate lancets or strips.

An app called Patterns is available for iOS and Android that allows the results from the device to automatically sync via Bluetooth. It visually presents glucose trends and enables data sharing with health care providers.

“We know that people with diabetes are more effective at managing their diabetes when they regularly check their blood glucose and use the information to take action,” said Daniel Einhorn, MD, medical director of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, president of Diabetes and Endocrine Associates, and chairperson of the Intuity Medical Scientific Advisory Board, in a company statement.

“My patients and millions of others with diabetes have struggled for decades with the burden of checking their glucose because it’s complicated, there’s a lot to carry around, and it’s intrusive,” he added. “What they’ve needed is a simple, quick, and truly discreet way to check their blood glucose, so they’ll actually do it.”

How does POGO compare with CGM?

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), such as the Abbott FreeStyle Libre, Dexcom G6, and Eversense implant, are increasingly employed by people with type 1 diabetes, and some with type 2 diabetes, to keep a close eye on their blood glucose levels.

Asked how the POGO device compares with CGM systems, Intuity Chief Commercial Officer Dean Zikria said: “While [CGM] is certainly an important option for a subset of people with diabetes, CGM is a very different technology, requiring a user to wear a sensor and transmitter on their body.”

“Patients also need to obtain a prescription in order to use CGM.”

“Conversely, POGO Automatic is available with or without a prescription. POGO Automatic also gives people who do not want to wear a device on their body a new choice other than traditional blood glucose monitoring,” Mr. Zikria added.

The POGO system is available at U.S. pharmacies, including CVS and Walgreens, and can also be purchased online.

The device costs $68 from the company website and a pack of 5 cartridges (each containing 10 tests, with an aim of people performing 1-2 tests per day) costs a further $32 as a one-off, or $32 per month as a subscription.

The product is also eligible for purchase using Flexible Spending Accounts and Health Savings Accounts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The POGO Automatic Blood Glucose Monitoring System (Intuity Medical) has been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for people with diabetes aged 13 years and older.

It contains a 10-test cartridge, and once loaded and the monitor is turned on, the user only has to press their finger on a button to activate POGO Automatic, which then does all the work of lancing and blood collection, followed by a 4-second countdown and a result. Users only need to carry the monitor and not separate lancets or strips.

An app called Patterns is available for iOS and Android that allows the results from the device to automatically sync via Bluetooth. It visually presents glucose trends and enables data sharing with health care providers.

“We know that people with diabetes are more effective at managing their diabetes when they regularly check their blood glucose and use the information to take action,” said Daniel Einhorn, MD, medical director of Scripps Whittier Diabetes Institute, president of Diabetes and Endocrine Associates, and chairperson of the Intuity Medical Scientific Advisory Board, in a company statement.

“My patients and millions of others with diabetes have struggled for decades with the burden of checking their glucose because it’s complicated, there’s a lot to carry around, and it’s intrusive,” he added. “What they’ve needed is a simple, quick, and truly discreet way to check their blood glucose, so they’ll actually do it.”

How does POGO compare with CGM?

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), such as the Abbott FreeStyle Libre, Dexcom G6, and Eversense implant, are increasingly employed by people with type 1 diabetes, and some with type 2 diabetes, to keep a close eye on their blood glucose levels.

Asked how the POGO device compares with CGM systems, Intuity Chief Commercial Officer Dean Zikria said: “While [CGM] is certainly an important option for a subset of people with diabetes, CGM is a very different technology, requiring a user to wear a sensor and transmitter on their body.”

“Patients also need to obtain a prescription in order to use CGM.”

“Conversely, POGO Automatic is available with or without a prescription. POGO Automatic also gives people who do not want to wear a device on their body a new choice other than traditional blood glucose monitoring,” Mr. Zikria added.

The POGO system is available at U.S. pharmacies, including CVS and Walgreens, and can also be purchased online.

The device costs $68 from the company website and a pack of 5 cartridges (each containing 10 tests, with an aim of people performing 1-2 tests per day) costs a further $32 as a one-off, or $32 per month as a subscription.

The product is also eligible for purchase using Flexible Spending Accounts and Health Savings Accounts.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia tied to a threefold increased risk for dementia

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Alopecia areata (AA) has been linked to a significantly increased risk for dementia, new research shows.

After controlling for an array of potential confounders, investigators found a threefold higher risk of developing any form of dementia and a fourfold higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in those with AA versus the controls.

“AA shares a similar inflammatory signature with dementia and has great psychological impacts that lead to poor social engagement,” lead author Cheng-Yuan Li, MD, MSc, of the department of dermatology, Taipei (Taiwan) Veterans General Hospital.

“Poor social engagement and shared inflammatory cytokines might both be important links between AA and dementia,” said Dr. Li, who is also affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Institute of Brain Science at National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei.

The study was published online Oct. 26, 2021, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry (doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m13931).

Significant psychological impact

Patients with AA often experience anxiety and depression, possibly caused by the negative emotional and psychological impact of the hair loss and partial or even complete baldness associated with the disease, the authors noted.

However, AA is also associated with an array of other atopic and autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Epidemiologic research has suggested a link between dementia and autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis and SLE, with some evidence suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms may “play a role” in the development of AD.

Dementia in general and AD in particular, “have been shown to include an inflammatory component” that may share some of the same mediators seen in AA (eg, IL-1 beta, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor–alpha).

Moreover, “the great negative psychosocial impact of AA might result in poor social engagement, a typical risk factor for dementia,” said Dr. Li. The investigators sought to investigate whether patients with AA actually do have a higher dementia risk than individuals without AA.

The researchers used data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, comparing 2,534 patients with AA against 25,340 controls matched for age, sex, residence, income, dementia-related comorbidities, systemic steroid use, and annual outpatient visits. Participants were enrolled between 1998 and 2011 and followed to the end of 2013.

The mean age of the cohort was 53.9 years, and a little over half (57.6%) were female. The most common comorbidity was hypertension (32.3%), followed by dyslipidemia (27%) and diabetes (15.4%).

Dual intervention

After adjusting for potential confounders, those with AA were more likely to develop dementia, AD, and unspecified dementia, compared with controls. They also had a numerically higher risk for vascular dementia, compared with controls, but it was not statistically significant.

When participants were stratified by age, investigators found a significant association between AA and higher risk for any dementia as well as unspecified dementia in individuals of all ages and an increased risk for AD in patients with dementia age at onset of 65 years and older.

The mean age of dementia diagnosis was considerably younger in patients with AA versus controls (73.4 vs. 78.9 years, P = .002). The risk for any dementia and unspecified dementia was higher in patients of both sexes, but the risk for AD was higher only in male patients.

Sensitivity analyses that excluded the first year or first 3 years of observation yielded similar and consistent findings.

“Intervention targeting poor social engagement and inflammatory cytokines may be beneficial to AA-associated dementia,” said Dr. Li.

“Physicians should be more aware of this possible association, help reduce disease discrimination among the public, and encourage more social engagement for AA patients,” he said.

“Further studies are needed to elucidate the underlying pathophysiology between AA and dementia risk,” he added.

No cause and effect

Commenting on the study, Heather M. Snyder, PhD, vice president of medical and scientific affairs, Alzheimer’s Association, said, “We continue to learn about and better understand factors that may increase or decrease a person’s risk of dementia.”

“While we know the immune system plays a role in Alzheimer’s and other dementia, we are still investigating links between, and impact of, autoimmune diseases – like alopecia areata, rheumatoid arthritis, and others – on our overall health and our brains, [which] may eventually give us important information on risk reduction strategies as well,” said Dr. Snyder, who was not involved in the research.

She cautioned that although the study did show a correlation between AA and dementia risk, this does not equate to a demonstration of cause and effect.

At present, “the message for clinicians is that when a patient comes to your office with complaints about their memory, they should, No. 1, be taken seriously; and, No. 2, receive a thorough evaluation that takes into account the many factors that may lead to cognitive decline,” Dr. Snyder said.

The study was supported by a grant from Taipei Veterans General Hospital and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan. Dr. Li, coauthors, and Dr. Snyder disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ivermectin–COVID-19 study retracted; authors blame file mix-up

The paper, “Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon,” appeared in the journal Viruses in May. According to the abstract: “A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 100 asymptomatic Lebanese subjects that have tested positive for SARS-CoV2. Fifty patients received standard preventive treatment, mainly supplements, and the experimental group received a single dose (according to body weight) of ivermectin, in addition to the same supplements the control group received.”

Results results results … and: “Ivermectin appears to be efficacious in providing clinical benefits in a randomized treatment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects, effectively resulting in fewer symptoms, lower viral load and reduced hospital admissions. However, larger-scale trials are warranted for this conclusion to be further cemented.”

However, in early October, the BBC reported — in a larger piece about the concerns about ivermectin-Covid-19 research — that the study “was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly – suggesting many of the trial’s apparent patients didn’t really exist.”

The study’s authors told the BBC that the ‘original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file’ and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

That’s not quite what the retraction notice states: “The journal retracts the article, Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon [ 1 ], cited above. Following publication, the authors contacted the editorial office regarding an error between files used for the statistical analysis. Adhering to our complaints procedure, an investigation was conducted that confirmed the error reported by the authors.

This retraction was approved by the Editor in Chief of the journal. The authors agreed to this retraction.”

Ali Samaha, of Lebanese University in Beirut, and the lead author of the study, told us: “It was brought to our attention that we have used wrong file for our paper. We informed immediately the journal and we have run investigations. After revising the raw data we realised that a file that was used to train a research assistant was sent by mistake for analysis. Re-analysing the original data , the conclusions of the paper remained valid. For our transparency we asked for retraction.”

About that BBC report? Samaha said: “The BBC article was generated before the report of independent reviewers who confirmed an innocent mistake by using wrong file.”

Samaha added that he and his colleagues are now considering whether to resubmit the paper.

The article has been cited four times, according to Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science — including in this meta-analysis published in June in the American Journal of Therapeutics , which concluded that: “Moderate-certainty evidence finds that large reductions in COVID-19 deaths are possible using ivermectin. Using ivermectin early in the clinical course may reduce numbers progressing to severe disease. The apparent safety and low cost suggest that ivermectin is likely to have a significant impact on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic globally.”

That article was a social media darling, receiving more than 45,000 tweets and pickups in 90 news outlets, according to Altmetrics, which ranks it No. 7 among all papers published at that time.

A version of this article first appeared on Retraction Watch.

The paper, “Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon,” appeared in the journal Viruses in May. According to the abstract: “A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 100 asymptomatic Lebanese subjects that have tested positive for SARS-CoV2. Fifty patients received standard preventive treatment, mainly supplements, and the experimental group received a single dose (according to body weight) of ivermectin, in addition to the same supplements the control group received.”

Results results results … and: “Ivermectin appears to be efficacious in providing clinical benefits in a randomized treatment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects, effectively resulting in fewer symptoms, lower viral load and reduced hospital admissions. However, larger-scale trials are warranted for this conclusion to be further cemented.”

However, in early October, the BBC reported — in a larger piece about the concerns about ivermectin-Covid-19 research — that the study “was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly – suggesting many of the trial’s apparent patients didn’t really exist.”

The study’s authors told the BBC that the ‘original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file’ and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

That’s not quite what the retraction notice states: “The journal retracts the article, Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon [ 1 ], cited above. Following publication, the authors contacted the editorial office regarding an error between files used for the statistical analysis. Adhering to our complaints procedure, an investigation was conducted that confirmed the error reported by the authors.

This retraction was approved by the Editor in Chief of the journal. The authors agreed to this retraction.”

Ali Samaha, of Lebanese University in Beirut, and the lead author of the study, told us: “It was brought to our attention that we have used wrong file for our paper. We informed immediately the journal and we have run investigations. After revising the raw data we realised that a file that was used to train a research assistant was sent by mistake for analysis. Re-analysing the original data , the conclusions of the paper remained valid. For our transparency we asked for retraction.”

About that BBC report? Samaha said: “The BBC article was generated before the report of independent reviewers who confirmed an innocent mistake by using wrong file.”

Samaha added that he and his colleagues are now considering whether to resubmit the paper.

The article has been cited four times, according to Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science — including in this meta-analysis published in June in the American Journal of Therapeutics , which concluded that: “Moderate-certainty evidence finds that large reductions in COVID-19 deaths are possible using ivermectin. Using ivermectin early in the clinical course may reduce numbers progressing to severe disease. The apparent safety and low cost suggest that ivermectin is likely to have a significant impact on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic globally.”

That article was a social media darling, receiving more than 45,000 tweets and pickups in 90 news outlets, according to Altmetrics, which ranks it No. 7 among all papers published at that time.

A version of this article first appeared on Retraction Watch.

The paper, “Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon,” appeared in the journal Viruses in May. According to the abstract: “A randomized controlled trial was conducted in 100 asymptomatic Lebanese subjects that have tested positive for SARS-CoV2. Fifty patients received standard preventive treatment, mainly supplements, and the experimental group received a single dose (according to body weight) of ivermectin, in addition to the same supplements the control group received.”

Results results results … and: “Ivermectin appears to be efficacious in providing clinical benefits in a randomized treatment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-positive subjects, effectively resulting in fewer symptoms, lower viral load and reduced hospital admissions. However, larger-scale trials are warranted for this conclusion to be further cemented.”

However, in early October, the BBC reported — in a larger piece about the concerns about ivermectin-Covid-19 research — that the study “was found to have blocks of details of 11 patients that had been copied and pasted repeatedly – suggesting many of the trial’s apparent patients didn’t really exist.”

The study’s authors told the BBC that the ‘original set of data was rigged, sabotaged or mistakenly entered in the final file’ and that they have submitted a retraction to the scientific journal which published it.

That’s not quite what the retraction notice states: “The journal retracts the article, Effects of a Single Dose of Ivermectin on Viral and Clinical Outcomes in Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infected Subjects: A Pilot Clinical Trial in Lebanon [ 1 ], cited above. Following publication, the authors contacted the editorial office regarding an error between files used for the statistical analysis. Adhering to our complaints procedure, an investigation was conducted that confirmed the error reported by the authors.

This retraction was approved by the Editor in Chief of the journal. The authors agreed to this retraction.”

Ali Samaha, of Lebanese University in Beirut, and the lead author of the study, told us: “It was brought to our attention that we have used wrong file for our paper. We informed immediately the journal and we have run investigations. After revising the raw data we realised that a file that was used to train a research assistant was sent by mistake for analysis. Re-analysing the original data , the conclusions of the paper remained valid. For our transparency we asked for retraction.”

About that BBC report? Samaha said: “The BBC article was generated before the report of independent reviewers who confirmed an innocent mistake by using wrong file.”

Samaha added that he and his colleagues are now considering whether to resubmit the paper.

The article has been cited four times, according to Clarivate Analytics’ Web of Science — including in this meta-analysis published in June in the American Journal of Therapeutics , which concluded that: “Moderate-certainty evidence finds that large reductions in COVID-19 deaths are possible using ivermectin. Using ivermectin early in the clinical course may reduce numbers progressing to severe disease. The apparent safety and low cost suggest that ivermectin is likely to have a significant impact on the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic globally.”

That article was a social media darling, receiving more than 45,000 tweets and pickups in 90 news outlets, according to Altmetrics, which ranks it No. 7 among all papers published at that time.

A version of this article first appeared on Retraction Watch.

Update on the Pediatric Dermatology Workforce Shortage

Pediatric dermatology is a relatively young subspecialty. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) was established in 1975, followed by the creation of the journal Pediatric Dermatology in 1982 and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Dermatology in 1986.1 In 2000, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) officially recognized pediatric dermatology as a unique subspecialty of the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). During that time, informal fellowship experiences emerged, and formal 1-year training programs approved by the ABD evolved by 2006. A subspecialty certification examination was created and has been administered every other year since 2004.1 Data provided by the SPD indicate that approximately 431 US dermatologists have passed the ABD’s pediatric dermatology board certification examination thus far (unpublished data, September 2021).

In 1986, the first systematic evaluation of the US pediatric dermatology workforce revealed a total of 57 practicing pediatric dermatologists and concluded that job opportunities appeared to be limited at that time.2 Since then, the demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to grow steadily, and the number of board-certified pediatric dermatologists practicing in the United States has increased to at least 317 per data from a 2020 survey.3 However, given that there are more than 11,000 board-certified dermatologists in the United States, there continues to be a severe shortage of pediatric dermatologists.1

Increased Demand for Pediatric Dermatologists

Approximately 10% to 30% of almost 200 million annual outpatient pediatric primary care visits involve a skin concern. Although many of these problems can be handled by primary care physicians, more than 80% of pediatricians report having difficulty accessing dermatology services for their patients.4 In surveys of pediatricians, pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate but has consistently ranked third among the specialties deemed most difficult to access.5-7 In addition, it is not uncommon for the wait time to see a pediatric dermatologist to be 6 weeks or longer.5,8

Recent population data estimate that there are 73 million children living in the United States.9 If there are roughly 317 practicing board-certified pediatric dermatologists, that translates into approximately 4.3 pediatric dermatologists per million children. This number is far smaller than the 4 general dermatologists per 100,000 individuals recommended by Glazer et al10 in 2017. To meet this suggested ratio goal, the workforce of pediatric dermatologists would have to increase to 2920. In addition to this severe workforce shortage, there is an additional problem with geographic maldistribution of pediatric dermatologists. More than 98% of pediatric dermatologists practice in metropolitan areas. At least 8 states and 95% of counties have no pediatric dermatologist, and there are no pediatric dermatologists practicing in rural counties.9 This disparity has considerable implications for barriers to care and lack of access for children living in underserved areas. Suggestions for attracting pediatric dermatologists to practice in these areas have included loan forgiveness programs as well as remote mentorship programs to provide professional support.8,9

Training in Pediatrics

There currently are 38 ABD-approved pediatric dermatology fellowship training programs in the United States. Beginning in 2009, pediatric dermatology fellowship programs have participated in the SF Match program. Data provided by the SPD show that, since 2012, up to 27 programs have participated in the annual Match, offering a total number of positions ranging from 27 to 38; however, only 11 to 21 positions have been filled each year, leaving a large number of post-Match vacancies (unpublished data, September 2021).

Surveys have explored the reasons behind this lack of interest in pediatric dermatology training among dermatology residents. Factors that have been mentioned include lack of exposure and mentorship in medical school and residency, the financial hardship of an additional year of fellowship training, and historically lower salaries for pediatric dermatologists compared to general dermatologists.3,6

A 2004 survey revealed that more than 75% of dermatology department chairs believed it was important to have a pediatric dermatologist on the faculty; however, at that time only 48% of dermatology programs reported having at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatology faculty member.11 By 2008, a follow-up survey showed an increase to 70% of dermatology training programs reporting at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatologist; however, 43% of departments still had at least 1 open position, and 76% of those programs shared that they had been searching for more than 1 year.2 Currently, the Accreditation Data System of the ACGME shows a total of 144 accredited US dermatology training programs. Of those, 117 programs have 1 or more board-certified pediatric dermatology faculty member, and 27 programs still have none (unpublished data, September 2021).

A shortage of pediatric dermatologists in training programs contributes to the lack of exposure and mentorship for medical students and residents during a critical time in professional development. Studies show that up to 91% of pediatric dermatologists decided to pursue training in pediatric dermatology during medical school, pediatrics residency, or dermatology residency. In one survey, 84% of respondents (N=109) cited early mentorship as the most important factor in their decision to pursue pediatric dermatology.6

A lack of pediatric dermatologists also results in suboptimal dermatology training for residents who care for children in primary care specialties, including pediatrics, combined internal medicine and pediatrics, and family practice. Multiple surveys have shown that many pediatricians feel they received inadequate training in dermatology during residency. Up to 38% have cited a need for more pediatric dermatology education (N=755).5,6 In addition, studies show a wide disparity in diagnostic accuracy between dermatologists and pediatricians, with one concluding that more than one-third of referrals to pediatric dermatologists were initially misdiagnosed and/or incorrectly treated.5,7

Recruitment Efforts for Pediatric Dermatologists

There are multiple strategies for recruiting trainees into the pediatric dermatology workforce. First, given the importance of early exposure to the field and role models/mentors, pediatric dermatologists must take advantage of every opportunity to interact with medical students and residents. They can share their genuine enthusiasm and love for the specialty while encouraging and supporting those who show interest. They also should seek opportunities for teaching, lecturing, and advising at every level of training. In addition, they can enhance visibility of the specialty by participating in career forums and/or assuming leadership roles within their departments or institutions.12 Another suggestion is for dermatology training programs to consider giving priority to qualified applicants who express sincere interest in pursuing pediatric dermatology training (including those who have already completed pediatrics residency). Although a 2008 survey revealed that 39% of dermatology residency programs (N=80) favored giving priority to applicants demonstrating interest in pediatric dermatology, others were against it, citing issues such as lack of funding for additional residency training, lack of pediatric dermatology mentors within the program, and an overall mistrust of applicants’ sincerity.2

Final Thoughts

The subspecialty of pediatric dermatology has experienced remarkable growth over the last 40 years; however, demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to outpace supply, resulting in a persistent and notable workforce shortage. Overall, the current supply of pediatric dermatologists can neither meet the clinical demands of the pediatric population nor fulfill academic needs of existing training programs. We must continue to develop novel strategies for increasing the pool of students and residents who are interested in pursuing careers in pediatric dermatology. Ultimately, we also must create incentives and develop tactics to address the geographic maldistribution that exists within the specialty.

- Prindaville B, Antaya R, Siegfried E. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12.

- Craiglow BG, Resneck JS, Lucky AW, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: perspectives from academia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:986-989.

- Ashrafzadeh S, Peters G, Brandling-Bennett H, et al. The geographic distribution of the US pediatric dermatologist workforce: a national cross-sectional study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:1098-1105.

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897.

- Prindaville B, Simon S, Horii K. Dermatology-related outpatient visits by children: implications for workforce and pediatric education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:228-229.

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim S, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-375.

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. The US pediatric dermatology workforce: an assessment of productivity and practice patterns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:825-829.

- Prindaville B, Horii K, Siegfried E, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:166-168.

- Ugwu-Dike P, Nambudiri V. Access as equity: addressing the distribution of the pediatric dermatology workforce [published online August 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14665

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Hester EJ, McNealy KM, Kelloff JN, et al. Demand outstrips supply of US pediatric dermatologists: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:431-434.

- Wright TS, Huang JT. Comment on “pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States”. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:177-178.

Pediatric dermatology is a relatively young subspecialty. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) was established in 1975, followed by the creation of the journal Pediatric Dermatology in 1982 and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Dermatology in 1986.1 In 2000, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) officially recognized pediatric dermatology as a unique subspecialty of the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). During that time, informal fellowship experiences emerged, and formal 1-year training programs approved by the ABD evolved by 2006. A subspecialty certification examination was created and has been administered every other year since 2004.1 Data provided by the SPD indicate that approximately 431 US dermatologists have passed the ABD’s pediatric dermatology board certification examination thus far (unpublished data, September 2021).

In 1986, the first systematic evaluation of the US pediatric dermatology workforce revealed a total of 57 practicing pediatric dermatologists and concluded that job opportunities appeared to be limited at that time.2 Since then, the demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to grow steadily, and the number of board-certified pediatric dermatologists practicing in the United States has increased to at least 317 per data from a 2020 survey.3 However, given that there are more than 11,000 board-certified dermatologists in the United States, there continues to be a severe shortage of pediatric dermatologists.1

Increased Demand for Pediatric Dermatologists

Approximately 10% to 30% of almost 200 million annual outpatient pediatric primary care visits involve a skin concern. Although many of these problems can be handled by primary care physicians, more than 80% of pediatricians report having difficulty accessing dermatology services for their patients.4 In surveys of pediatricians, pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate but has consistently ranked third among the specialties deemed most difficult to access.5-7 In addition, it is not uncommon for the wait time to see a pediatric dermatologist to be 6 weeks or longer.5,8

Recent population data estimate that there are 73 million children living in the United States.9 If there are roughly 317 practicing board-certified pediatric dermatologists, that translates into approximately 4.3 pediatric dermatologists per million children. This number is far smaller than the 4 general dermatologists per 100,000 individuals recommended by Glazer et al10 in 2017. To meet this suggested ratio goal, the workforce of pediatric dermatologists would have to increase to 2920. In addition to this severe workforce shortage, there is an additional problem with geographic maldistribution of pediatric dermatologists. More than 98% of pediatric dermatologists practice in metropolitan areas. At least 8 states and 95% of counties have no pediatric dermatologist, and there are no pediatric dermatologists practicing in rural counties.9 This disparity has considerable implications for barriers to care and lack of access for children living in underserved areas. Suggestions for attracting pediatric dermatologists to practice in these areas have included loan forgiveness programs as well as remote mentorship programs to provide professional support.8,9

Training in Pediatrics

There currently are 38 ABD-approved pediatric dermatology fellowship training programs in the United States. Beginning in 2009, pediatric dermatology fellowship programs have participated in the SF Match program. Data provided by the SPD show that, since 2012, up to 27 programs have participated in the annual Match, offering a total number of positions ranging from 27 to 38; however, only 11 to 21 positions have been filled each year, leaving a large number of post-Match vacancies (unpublished data, September 2021).

Surveys have explored the reasons behind this lack of interest in pediatric dermatology training among dermatology residents. Factors that have been mentioned include lack of exposure and mentorship in medical school and residency, the financial hardship of an additional year of fellowship training, and historically lower salaries for pediatric dermatologists compared to general dermatologists.3,6

A 2004 survey revealed that more than 75% of dermatology department chairs believed it was important to have a pediatric dermatologist on the faculty; however, at that time only 48% of dermatology programs reported having at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatology faculty member.11 By 2008, a follow-up survey showed an increase to 70% of dermatology training programs reporting at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatologist; however, 43% of departments still had at least 1 open position, and 76% of those programs shared that they had been searching for more than 1 year.2 Currently, the Accreditation Data System of the ACGME shows a total of 144 accredited US dermatology training programs. Of those, 117 programs have 1 or more board-certified pediatric dermatology faculty member, and 27 programs still have none (unpublished data, September 2021).

A shortage of pediatric dermatologists in training programs contributes to the lack of exposure and mentorship for medical students and residents during a critical time in professional development. Studies show that up to 91% of pediatric dermatologists decided to pursue training in pediatric dermatology during medical school, pediatrics residency, or dermatology residency. In one survey, 84% of respondents (N=109) cited early mentorship as the most important factor in their decision to pursue pediatric dermatology.6

A lack of pediatric dermatologists also results in suboptimal dermatology training for residents who care for children in primary care specialties, including pediatrics, combined internal medicine and pediatrics, and family practice. Multiple surveys have shown that many pediatricians feel they received inadequate training in dermatology during residency. Up to 38% have cited a need for more pediatric dermatology education (N=755).5,6 In addition, studies show a wide disparity in diagnostic accuracy between dermatologists and pediatricians, with one concluding that more than one-third of referrals to pediatric dermatologists were initially misdiagnosed and/or incorrectly treated.5,7

Recruitment Efforts for Pediatric Dermatologists

There are multiple strategies for recruiting trainees into the pediatric dermatology workforce. First, given the importance of early exposure to the field and role models/mentors, pediatric dermatologists must take advantage of every opportunity to interact with medical students and residents. They can share their genuine enthusiasm and love for the specialty while encouraging and supporting those who show interest. They also should seek opportunities for teaching, lecturing, and advising at every level of training. In addition, they can enhance visibility of the specialty by participating in career forums and/or assuming leadership roles within their departments or institutions.12 Another suggestion is for dermatology training programs to consider giving priority to qualified applicants who express sincere interest in pursuing pediatric dermatology training (including those who have already completed pediatrics residency). Although a 2008 survey revealed that 39% of dermatology residency programs (N=80) favored giving priority to applicants demonstrating interest in pediatric dermatology, others were against it, citing issues such as lack of funding for additional residency training, lack of pediatric dermatology mentors within the program, and an overall mistrust of applicants’ sincerity.2

Final Thoughts

The subspecialty of pediatric dermatology has experienced remarkable growth over the last 40 years; however, demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to outpace supply, resulting in a persistent and notable workforce shortage. Overall, the current supply of pediatric dermatologists can neither meet the clinical demands of the pediatric population nor fulfill academic needs of existing training programs. We must continue to develop novel strategies for increasing the pool of students and residents who are interested in pursuing careers in pediatric dermatology. Ultimately, we also must create incentives and develop tactics to address the geographic maldistribution that exists within the specialty.

Pediatric dermatology is a relatively young subspecialty. The Society for Pediatric Dermatology (SPD) was established in 1975, followed by the creation of the journal Pediatric Dermatology in 1982 and the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Dermatology in 1986.1 In 2000, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) officially recognized pediatric dermatology as a unique subspecialty of the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). During that time, informal fellowship experiences emerged, and formal 1-year training programs approved by the ABD evolved by 2006. A subspecialty certification examination was created and has been administered every other year since 2004.1 Data provided by the SPD indicate that approximately 431 US dermatologists have passed the ABD’s pediatric dermatology board certification examination thus far (unpublished data, September 2021).

In 1986, the first systematic evaluation of the US pediatric dermatology workforce revealed a total of 57 practicing pediatric dermatologists and concluded that job opportunities appeared to be limited at that time.2 Since then, the demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to grow steadily, and the number of board-certified pediatric dermatologists practicing in the United States has increased to at least 317 per data from a 2020 survey.3 However, given that there are more than 11,000 board-certified dermatologists in the United States, there continues to be a severe shortage of pediatric dermatologists.1

Increased Demand for Pediatric Dermatologists

Approximately 10% to 30% of almost 200 million annual outpatient pediatric primary care visits involve a skin concern. Although many of these problems can be handled by primary care physicians, more than 80% of pediatricians report having difficulty accessing dermatology services for their patients.4 In surveys of pediatricians, pediatric dermatology has the third highest referral rate but has consistently ranked third among the specialties deemed most difficult to access.5-7 In addition, it is not uncommon for the wait time to see a pediatric dermatologist to be 6 weeks or longer.5,8

Recent population data estimate that there are 73 million children living in the United States.9 If there are roughly 317 practicing board-certified pediatric dermatologists, that translates into approximately 4.3 pediatric dermatologists per million children. This number is far smaller than the 4 general dermatologists per 100,000 individuals recommended by Glazer et al10 in 2017. To meet this suggested ratio goal, the workforce of pediatric dermatologists would have to increase to 2920. In addition to this severe workforce shortage, there is an additional problem with geographic maldistribution of pediatric dermatologists. More than 98% of pediatric dermatologists practice in metropolitan areas. At least 8 states and 95% of counties have no pediatric dermatologist, and there are no pediatric dermatologists practicing in rural counties.9 This disparity has considerable implications for barriers to care and lack of access for children living in underserved areas. Suggestions for attracting pediatric dermatologists to practice in these areas have included loan forgiveness programs as well as remote mentorship programs to provide professional support.8,9

Training in Pediatrics

There currently are 38 ABD-approved pediatric dermatology fellowship training programs in the United States. Beginning in 2009, pediatric dermatology fellowship programs have participated in the SF Match program. Data provided by the SPD show that, since 2012, up to 27 programs have participated in the annual Match, offering a total number of positions ranging from 27 to 38; however, only 11 to 21 positions have been filled each year, leaving a large number of post-Match vacancies (unpublished data, September 2021).

Surveys have explored the reasons behind this lack of interest in pediatric dermatology training among dermatology residents. Factors that have been mentioned include lack of exposure and mentorship in medical school and residency, the financial hardship of an additional year of fellowship training, and historically lower salaries for pediatric dermatologists compared to general dermatologists.3,6

A 2004 survey revealed that more than 75% of dermatology department chairs believed it was important to have a pediatric dermatologist on the faculty; however, at that time only 48% of dermatology programs reported having at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatology faculty member.11 By 2008, a follow-up survey showed an increase to 70% of dermatology training programs reporting at least 1 full-time pediatric dermatologist; however, 43% of departments still had at least 1 open position, and 76% of those programs shared that they had been searching for more than 1 year.2 Currently, the Accreditation Data System of the ACGME shows a total of 144 accredited US dermatology training programs. Of those, 117 programs have 1 or more board-certified pediatric dermatology faculty member, and 27 programs still have none (unpublished data, September 2021).

A shortage of pediatric dermatologists in training programs contributes to the lack of exposure and mentorship for medical students and residents during a critical time in professional development. Studies show that up to 91% of pediatric dermatologists decided to pursue training in pediatric dermatology during medical school, pediatrics residency, or dermatology residency. In one survey, 84% of respondents (N=109) cited early mentorship as the most important factor in their decision to pursue pediatric dermatology.6

A lack of pediatric dermatologists also results in suboptimal dermatology training for residents who care for children in primary care specialties, including pediatrics, combined internal medicine and pediatrics, and family practice. Multiple surveys have shown that many pediatricians feel they received inadequate training in dermatology during residency. Up to 38% have cited a need for more pediatric dermatology education (N=755).5,6 In addition, studies show a wide disparity in diagnostic accuracy between dermatologists and pediatricians, with one concluding that more than one-third of referrals to pediatric dermatologists were initially misdiagnosed and/or incorrectly treated.5,7

Recruitment Efforts for Pediatric Dermatologists

There are multiple strategies for recruiting trainees into the pediatric dermatology workforce. First, given the importance of early exposure to the field and role models/mentors, pediatric dermatologists must take advantage of every opportunity to interact with medical students and residents. They can share their genuine enthusiasm and love for the specialty while encouraging and supporting those who show interest. They also should seek opportunities for teaching, lecturing, and advising at every level of training. In addition, they can enhance visibility of the specialty by participating in career forums and/or assuming leadership roles within their departments or institutions.12 Another suggestion is for dermatology training programs to consider giving priority to qualified applicants who express sincere interest in pursuing pediatric dermatology training (including those who have already completed pediatrics residency). Although a 2008 survey revealed that 39% of dermatology residency programs (N=80) favored giving priority to applicants demonstrating interest in pediatric dermatology, others were against it, citing issues such as lack of funding for additional residency training, lack of pediatric dermatology mentors within the program, and an overall mistrust of applicants’ sincerity.2

Final Thoughts

The subspecialty of pediatric dermatology has experienced remarkable growth over the last 40 years; however, demand for pediatric dermatology services has continued to outpace supply, resulting in a persistent and notable workforce shortage. Overall, the current supply of pediatric dermatologists can neither meet the clinical demands of the pediatric population nor fulfill academic needs of existing training programs. We must continue to develop novel strategies for increasing the pool of students and residents who are interested in pursuing careers in pediatric dermatology. Ultimately, we also must create incentives and develop tactics to address the geographic maldistribution that exists within the specialty.

- Prindaville B, Antaya R, Siegfried E. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12.

- Craiglow BG, Resneck JS, Lucky AW, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: perspectives from academia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:986-989.

- Ashrafzadeh S, Peters G, Brandling-Bennett H, et al. The geographic distribution of the US pediatric dermatologist workforce: a national cross-sectional study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:1098-1105.

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897.

- Prindaville B, Simon S, Horii K. Dermatology-related outpatient visits by children: implications for workforce and pediatric education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:228-229.

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim S, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-375.

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. The US pediatric dermatology workforce: an assessment of productivity and practice patterns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:825-829.

- Prindaville B, Horii K, Siegfried E, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:166-168.

- Ugwu-Dike P, Nambudiri V. Access as equity: addressing the distribution of the pediatric dermatology workforce [published online August 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14665

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Hester EJ, McNealy KM, Kelloff JN, et al. Demand outstrips supply of US pediatric dermatologists: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:431-434.

- Wright TS, Huang JT. Comment on “pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States”. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:177-178.

- Prindaville B, Antaya R, Siegfried E. Pediatric dermatology: past, present, and future. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:1-12.

- Craiglow BG, Resneck JS, Lucky AW, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: perspectives from academia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:986-989.

- Ashrafzadeh S, Peters G, Brandling-Bennett H, et al. The geographic distribution of the US pediatric dermatologist workforce: a national cross-sectional study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37:1098-1105.

- Stephens MR, Murthy AS, McMahon PJ. Wait times, health care touchpoints, and nonattendance in an academic pediatric dermatology clinic. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:893-897.

- Prindaville B, Simon S, Horii K. Dermatology-related outpatient visits by children: implications for workforce and pediatric education. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:228-229.

- Admani S, Caufield M, Kim S, et al. Understanding the pediatric dermatology workforce shortage: mentoring matters. J Pediatr. 2014;164:372-375.

- Fogel AL, Teng JM. The US pediatric dermatology workforce: an assessment of productivity and practice patterns. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:825-829.

- Prindaville B, Horii K, Siegfried E, et al. Pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:166-168.

- Ugwu-Dike P, Nambudiri V. Access as equity: addressing the distribution of the pediatric dermatology workforce [published online August 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14665

- Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:472-473.

- Hester EJ, McNealy KM, Kelloff JN, et al. Demand outstrips supply of US pediatric dermatologists: results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:431-434.

- Wright TS, Huang JT. Comment on “pediatric dermatology workforce in the United States”. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:177-178.

Not COVID Toes: Pool Palms and Feet in Pediatric Patients

Practice Gap

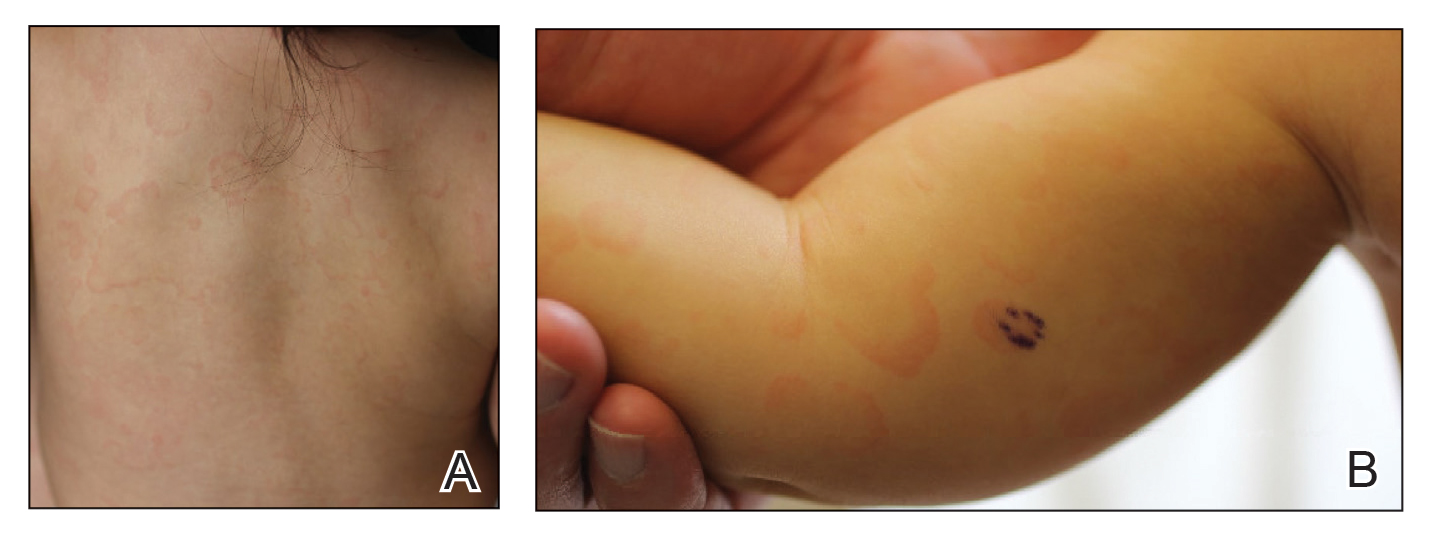

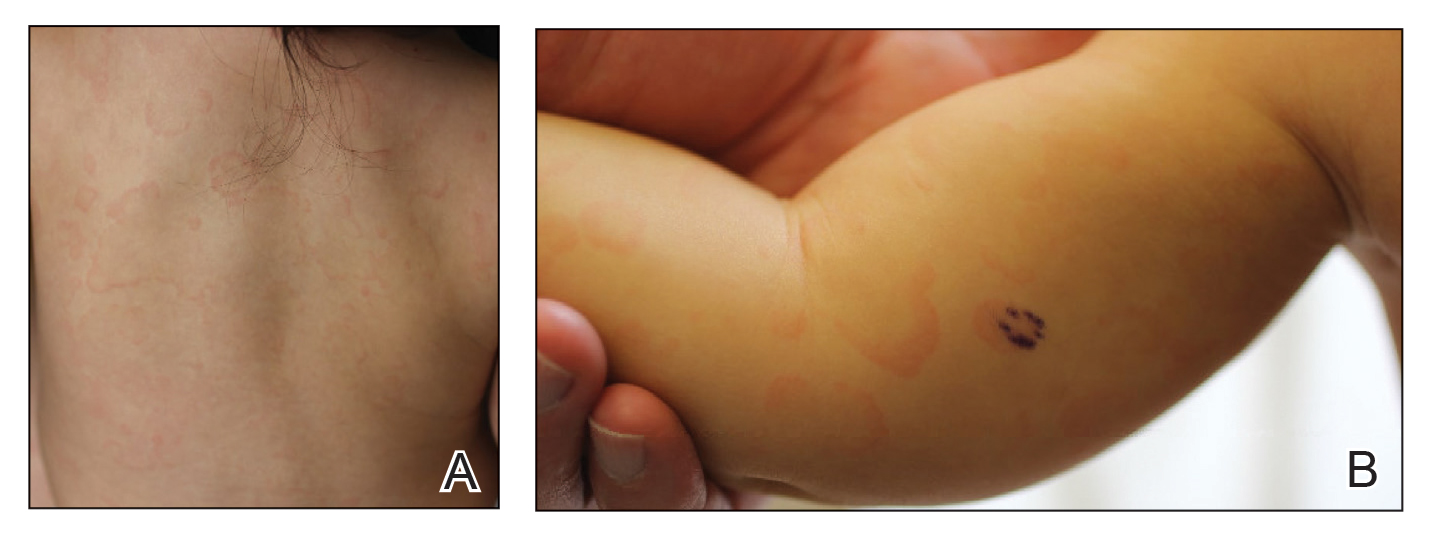

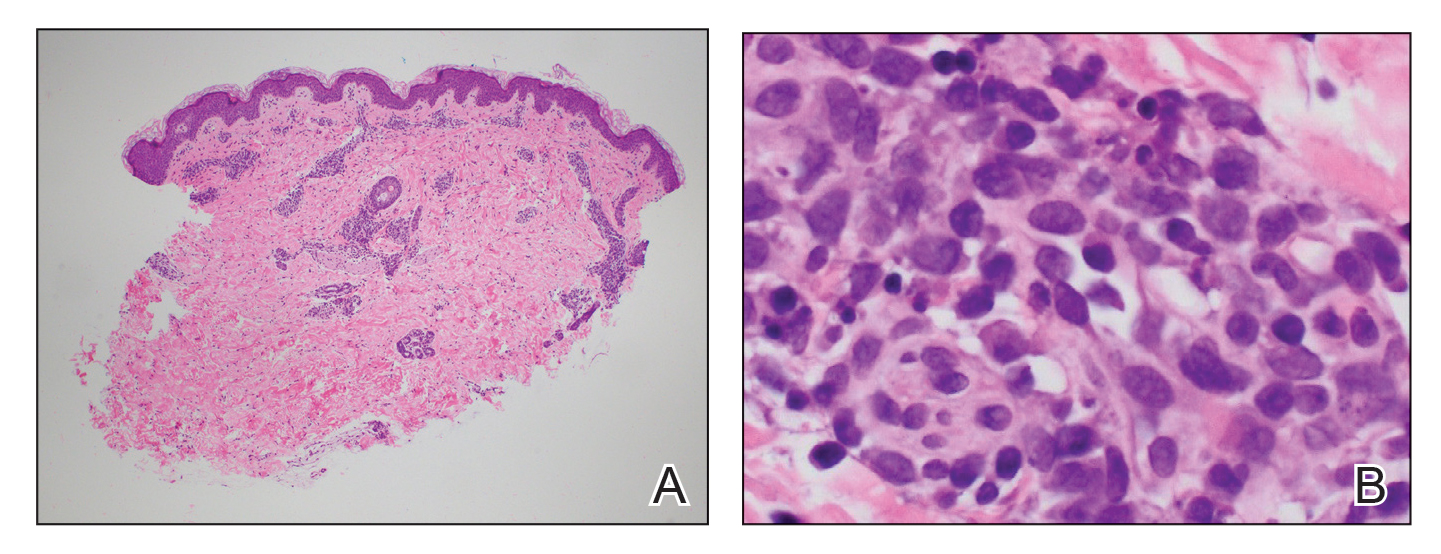

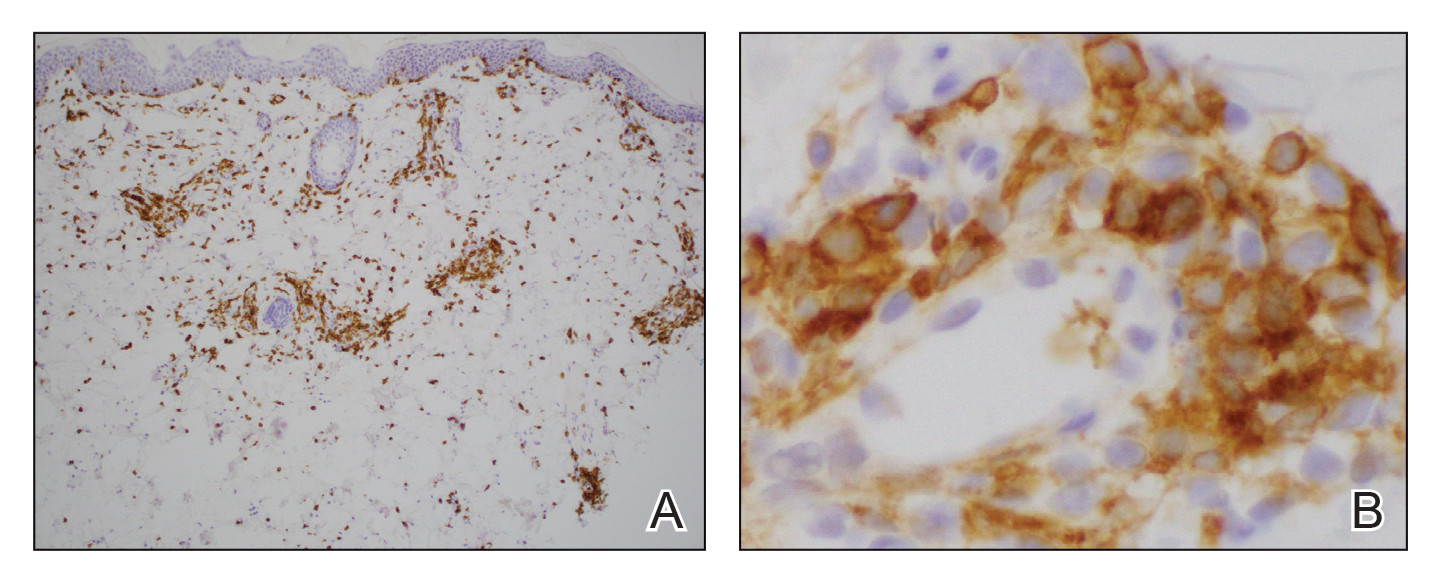

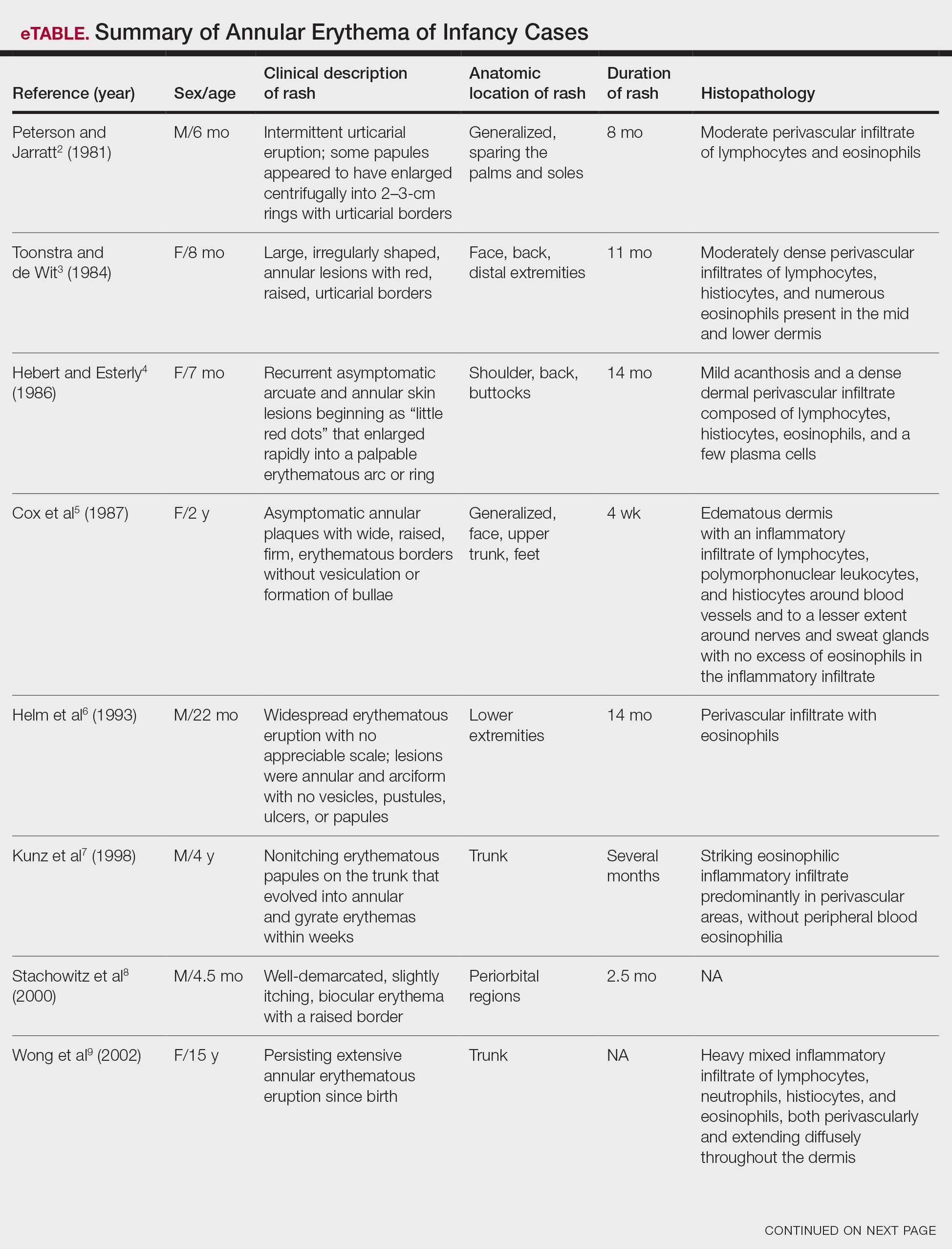

Frictional, symmetric, asymptomatic, erythematous macules of the hands and feet can be mistaken for perniolike lesions associated with COVID-19, commonly known as COVID toes. However, in a low-risk setting without other associated symptoms or concerning findings on examination, consider and inquire about frequent use of a swimming pool. This activity can lead to localized pressure- and friction-induced erythema on palmar and plantar surfaces, called “pool palms and feet,” expanding on the already-named lesion “pool palms”—an entity that is distinct from COVID toes.

Technique for Diagnosis

We evaluated 4 patients in the outpatient setting who presented with localized, patterned, erythematous lesions of the hands or feet, or both, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The parents of our patients were concerned that the rash represented “COVID fingers and toes,” which are perniolike lesions seen in patients with suspected or confirmed current or prior COVID-19.1

Pernio, also known as chilblains, is a superficial inflammatory vascular response, usually in the setting of exposure to cold.2 This phenomenon usually appears as erythematous or violaceous macules and papules on acral skin, particularly on the dorsum and sides of the fingers and toes, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in more severe cases. Initially, it is pruritic and painful at times.

With COVID toes, there often is a delayed presentation of perniolike lesions after the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, cough, headache, and sore throat.2,3 It has been described more often in younger patients and those with milder disease. However, because our patients had no known exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or other associated symptoms, our suspicion was low.

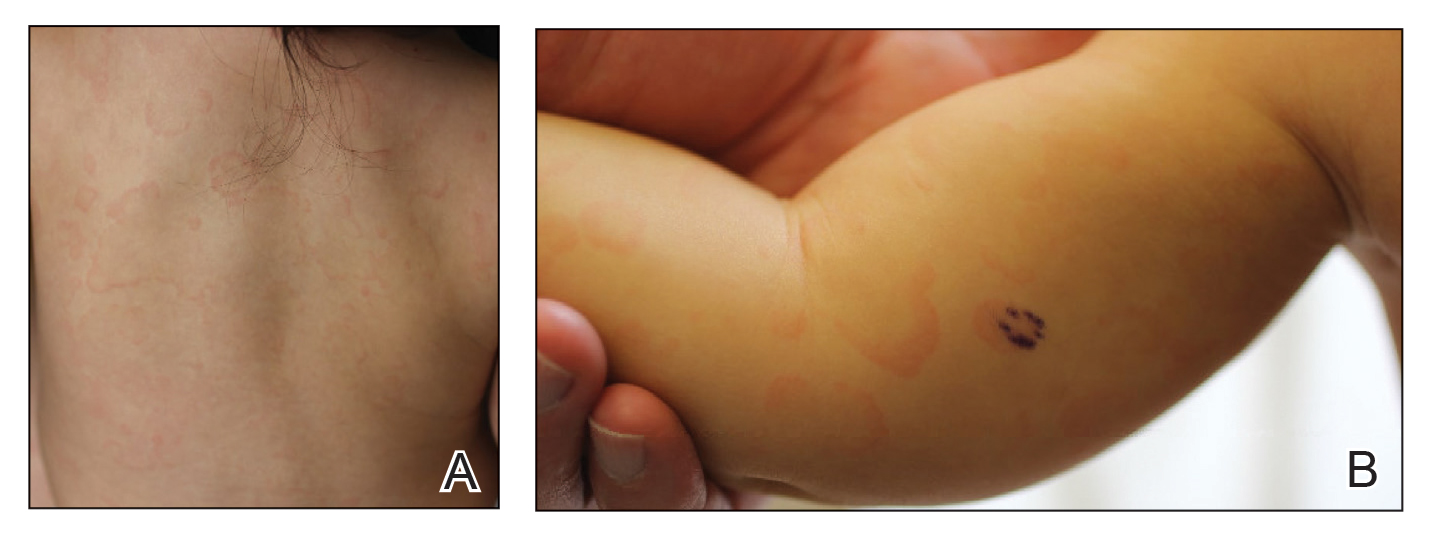

The 4 patients we evaluated—aged 4 to 12 years and in their usual good health—had blanchable erythema of the palmar fingers, palmar eminences of both hands, and plantar surfaces of both feet (Figure). There was no swelling or tenderness, and the lesions had no violaceous coloration, vesiculation, or ulceration. There was no associated pruritus or pain. One patient reported rough texture and mild peeling of the hands.

Upon further inquiry, the patients reported a history of extended time spent in home swimming pools, including holding on to the edge of the pool, due to limitation of activities because of COVID restrictions. One parent noted that the pool that caused the rash had a rough nonslip surface, whereas other pools that the children used, which had a smoother surface, caused no problems.

The morphology of symmetric blanching erythema in areas of pressure and friction, in the absence of a notable medical history, signs, or symptoms, was consistent with a diagnosis of pool palms, which has been described in the medical literature.4-9 Pool palms can affect the palms and soles, which are subject to substantial friction, especially when a person is getting in and out of the pool. There is a general consensus that pool palms is a frictional dermatitis affecting children because the greater fragility of their skin is exacerbated by immersion in water.4-9

Pool palms and feet is benign. Only supportive care, with cessation of swimming and application of emollients, is necessary.

Apart from COVID-19, other conditions to consider in a patient with erythematous lesions of the palms and soles include eczematous dermatitis; neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis; and, if lesions are vesicular, hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Juvenile plantar dermatosis, which is thought to be due to moisture with occlusion in shoes, also might be considered but is distinguished by more scales and fissures that can be painful.

Location of the lesions is a critical variable. The patients we evaluated had lesions primarily on palmar and plantar surfaces where contact with pool surfaces was greatest, such as at bony prominences, which supported a diagnosis of frictional dermatitis, such as pool palms and feet. A thorough history and physical examination are helpful in determining the diagnosis.

Practical Implications

It is important to consider and recognize this localized pressure phenomenon of pool palms and feet, thus obviating an unnecessary workup or therapeutic interventions. Specifically, a finding of erythematous asymptomatic macules, with or without scaling, on bony prominences of the palms and soles is more consistent with pool palms and feet.

Pernio and COVID toes both present as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in severe cases, often on the dorsum and sides of fingers and toes; typically the conditions are pruritic and painful at times.

Explaining the diagnosis of pool palms and feet and sharing one’s experience with similar cases might help alleviate parental fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- de Masson A, Bouaziz J-D, Sulimovic L, et al; SNDV (French National Union of Dermatologists–Venereologists). Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:667-670. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.161

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al; American Academy of Dermatology Ad Hoc Task Force on COVID-19. Pernio-like skin lesions associated with COVID-19: a case series of 318 patients from 8 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:486-492. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.109

- Freeman EE, McMahon DE, Lipoff JB, et al. The spectrum of COVID-19-associated dermatologic manifestations: an international registry of 716 patients from 31 countries. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1118-1129. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.1016

- Blauvelt A, Duarte AM, Schachner LA. Pool palms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:111. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80819-5

- Wong L-C, Rogers M. Pool palms. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:95. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00347.x

- Novoa A, Klear S. Pool palms. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:41. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-309633

- Morgado-Carasco D, Feola H, Vargas-Mora P. Pool palms. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2020;10:e2020009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1001a09

- Cutrone M, Valerio E, Grimalt R. Pool palms: a case report. Dermatol Case Rep. 2019;4:1000154.

- Martína JM, Ricart JM. Erythematous–violaceous lesions on the palms. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:507-508.

Practice Gap

Frictional, symmetric, asymptomatic, erythematous macules of the hands and feet can be mistaken for perniolike lesions associated with COVID-19, commonly known as COVID toes. However, in a low-risk setting without other associated symptoms or concerning findings on examination, consider and inquire about frequent use of a swimming pool. This activity can lead to localized pressure- and friction-induced erythema on palmar and plantar surfaces, called “pool palms and feet,” expanding on the already-named lesion “pool palms”—an entity that is distinct from COVID toes.

Technique for Diagnosis

We evaluated 4 patients in the outpatient setting who presented with localized, patterned, erythematous lesions of the hands or feet, or both, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The parents of our patients were concerned that the rash represented “COVID fingers and toes,” which are perniolike lesions seen in patients with suspected or confirmed current or prior COVID-19.1

Pernio, also known as chilblains, is a superficial inflammatory vascular response, usually in the setting of exposure to cold.2 This phenomenon usually appears as erythematous or violaceous macules and papules on acral skin, particularly on the dorsum and sides of the fingers and toes, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in more severe cases. Initially, it is pruritic and painful at times.

With COVID toes, there often is a delayed presentation of perniolike lesions after the onset of other COVID-19 symptoms, such as fever, cough, headache, and sore throat.2,3 It has been described more often in younger patients and those with milder disease. However, because our patients had no known exposure to SARS-CoV-2 or other associated symptoms, our suspicion was low.

The 4 patients we evaluated—aged 4 to 12 years and in their usual good health—had blanchable erythema of the palmar fingers, palmar eminences of both hands, and plantar surfaces of both feet (Figure). There was no swelling or tenderness, and the lesions had no violaceous coloration, vesiculation, or ulceration. There was no associated pruritus or pain. One patient reported rough texture and mild peeling of the hands.

Upon further inquiry, the patients reported a history of extended time spent in home swimming pools, including holding on to the edge of the pool, due to limitation of activities because of COVID restrictions. One parent noted that the pool that caused the rash had a rough nonslip surface, whereas other pools that the children used, which had a smoother surface, caused no problems.

The morphology of symmetric blanching erythema in areas of pressure and friction, in the absence of a notable medical history, signs, or symptoms, was consistent with a diagnosis of pool palms, which has been described in the medical literature.4-9 Pool palms can affect the palms and soles, which are subject to substantial friction, especially when a person is getting in and out of the pool. There is a general consensus that pool palms is a frictional dermatitis affecting children because the greater fragility of their skin is exacerbated by immersion in water.4-9

Pool palms and feet is benign. Only supportive care, with cessation of swimming and application of emollients, is necessary.

Apart from COVID-19, other conditions to consider in a patient with erythematous lesions of the palms and soles include eczematous dermatitis; neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis; and, if lesions are vesicular, hand-foot-and-mouth disease. Juvenile plantar dermatosis, which is thought to be due to moisture with occlusion in shoes, also might be considered but is distinguished by more scales and fissures that can be painful.

Location of the lesions is a critical variable. The patients we evaluated had lesions primarily on palmar and plantar surfaces where contact with pool surfaces was greatest, such as at bony prominences, which supported a diagnosis of frictional dermatitis, such as pool palms and feet. A thorough history and physical examination are helpful in determining the diagnosis.

Practical Implications

It is important to consider and recognize this localized pressure phenomenon of pool palms and feet, thus obviating an unnecessary workup or therapeutic interventions. Specifically, a finding of erythematous asymptomatic macules, with or without scaling, on bony prominences of the palms and soles is more consistent with pool palms and feet.

Pernio and COVID toes both present as erythematous to violaceous papules and macules, with edema, vesiculation, and ulceration in severe cases, often on the dorsum and sides of fingers and toes; typically the conditions are pruritic and painful at times.

Explaining the diagnosis of pool palms and feet and sharing one’s experience with similar cases might help alleviate parental fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Practice Gap