User login

Making a difference

Hospitalists engaging in advocacy efforts

Hospitalists around the country are devoting large portions of their spare time to a wide range of advocacy efforts. From health policy to caring for the unhoused population to diversity and equity to advocating for fellow hospitalists, these physicians are passionate about their causes and determined to make a difference.

Championing the unhoused

Sarah Stella, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health, was initially drawn there because of the population the hospital serves, which includes a high concentration of people experiencing homelessness. As she cared for her patients, Dr. Stella, who is also associate professor of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado, increasingly felt the desire to help prevent the negative downstream outcomes the hospital sees.

To understand the experiences of the unhoused outside the hospital, Dr. Stella started talking to her patients and people in community-based organizations that serve this population. “I learned a ton,” she said. “Homelessness feels like such an intractable, hopeless thing, but the more I talked to people, the more opportunities I saw to work toward something better.”

This led to a pilot grant to work with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to set up a community advisory panel. “My goal was to better understand their experiences and to develop a shared vision for how we collectively can do better,” said Dr. Stella. Eventually, she also received a grant from the University of Colorado, and multiple opportunities have sprung up ever since.

For the past several years, Dr. Stella has worked with Denver Health leadership to improve care for the homeless. “Right now, I’m working with a community team on developing an idea to provide peer support from people with a shared lived experience for people who are experiencing homelessness when they’re hospitalized. That’s really where my passion has been in working on the partnership,” she said.

Her advocacy role has been beneficial in her work as a hospitalist, particularly when COVID began. Dr. Stella again partnered with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to start a joint task force. “Everyone on our task force is motivated by this powerful desire to improve the health and lives of this community and that’s one of the silver linings in this pandemic for me,” said Dr. Stella.

Advocacy work has also increased Dr. Stella’s knowledge of what community support options are available for the unhoused. This allows her to educate her patients about their options and how to access them.

While she has colleagues who are able to compartmentalize their work, “I absolutely could not be a hospitalist without being an advocate,” Dr. Stella said. “For me, it has been a protective strategy in terms of burnout because I have to feel like I’m working to advocate for better policies and more appropriate resources to address the gaps that I’m seeing.”

Dr. Stella believes that physicians have a special credibility to advocate, tell stories, and use data to back their stories up. “We have to realize that we have this power, and we have it so we can empower others,” she said. “The people I’ve seen in my community who are working so hard to help people who are experiencing homelessness are the heroes. Understanding that and giving power to those people through our voice and our well-respected place in society drives me.”

Strengthening diversity, equity, and inclusion

In September 2020, Michael Bryant, MD, became the inaugural vice chair of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the department of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where he is also the division head of pediatric hospital medicine. “I was motivated to apply for this position because I wanted to be an agent for change to eliminate the institutional racism, social injustice, and marginalization that continues to threaten the lives and well-beings of so many Americans,” Dr. Bryant said.

Between the pandemic, the economic decline it has created, and the divisive political landscape, people of color have been especially affected. “These are poignant examples of the ever-widening divide and disenfranchisement many Americans feel,” said Dr. Bryant. “Gandhi said, ‘Be the change that you want to see,’ and that is what I want to model.”

At work, advocacy for diversity, equality, and inclusion is an innate part of everything he does. From the new physicians he recruits to the candidates he considers for leadership positions, Dr. Bryant strives “to have a workforce that mirrors the diversity of the patients we humbly care for and serve.”

Advocacy is intrinsic to Dr. Bryant’s worldview, in his quest to understand and accept each individual’s uniqueness, his desire “to embrace cultural humility,” his recognition that “our differences enhance us instead of diminishing us,” and his willingness to engage in difficult conversations.

“Advocacy means that I acknowledge that intent does not equal impact and that I must accept that what I do and what I say may have unintended consequences,” he said. “When that happens, I must resist becoming defensive and instead be willing to listen and learn.”

Dr. Bryant is proud of his accomplishments and enjoys his advocacy work. In his workplace, there are few African Americans in leadership roles. This means that he is in high demand when it comes to making sure there’s representation during various processes such as hiring and vetting, a disparity known as the “minority tax.”

“I am thankful for the opportunities, but it does take a toll at times,” Dr. Bryant said, which is yet another reason why he is a proponent of increasing diversity and inclusion. “This allows us to build the resource pool as these needs arise and minimizes the toll of the ‘minority tax’ on any single person or small group of individuals.”

This summer, physicians from Dr. Bryant’s hospital participated in the national “White Coats for Black Lives” effort. He found it to be “an incredibly moving event” that hundreds of his colleagues participated in.

Dr. Bryant’s advice for hospitalists who want to get involved in advocacy efforts is to check out the movie “John Lewis: Good Trouble.” “He was a champion of human rights and fought for these rights until his death,” Dr. Bryant said. “He is a true American hero and a wonderful example.”

Bolstering health care change

Since his residency, Joshua Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, has developed an ever-increasing interest in legislative advocacy, particularly health policy. Getting involved in this arena requires an understanding of civics and government that goes beyond just the basics. “My desire to affect change in my own profession really served as the catalyst to get involved,” said Dr. Lenchus, the regional chief medical officer at Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “What better way to do that than by combining what we do on a daily basis in the practice of medicine with this new understanding of how laws are passed and promulgated?”

Dr. Lenchus has been involved with both state and national medical organizations and has served on public policy committees as a member and as a chair. “The charge of these committees is to monitor and navigate position statements and policies that will drive the entire organization,” he said. This means becoming knowledgeable enough about a topic to be able to talk about it eloquently and adding supporting personal or professional illustrations that reinforce the position to lawmakers.

He finds his advocacy efforts “incredibly rewarding” because they contribute to his endeavors “to help my colleagues practice medicine in a safe, efficient, and productive manner.” For instance, some of the organizations Dr. Lenchus was involved with helped make changes to the Affordable Care Act that ended up in its final version, as well as changes after it passed. “There are tangible things that advocacy enables us to do in our daily practice,” he said.

When something his organizations have advocated for does not pass, they know they need to try a different outlet. “You can’t win every fight,” he said. “Every time you go and comment on an issue, you have to understand that you’re there to do your best, and to the extent that the people you’re talking to are willing to listen to what you have to say, that’s where I think you can make the most impact.” When changes he has helped fight for do pass, “it really is amazing that you can tell your colleagues about your role in achieving meaningful change in the profession.”

Dr. Lenchus acknowledges that advocacy “can be all-consuming at times. We have to understand our limits.” That said, he thinks not engaging in advocacy could increase stress and potential burnout. “I think being involved in advocacy efforts really helps people conduct meaningful work and educates them about what it means not just to them, but to the rest of the medical profession and the patients that we serve,” he said.

For hospitalists who are interested in health policy advocacy, there are many ways to get involved, Dr. Lenchus said. You could join an organization (many organized medical societies have public policy committees), participate in advocacy activities, work on a political campaign, or even run for office yourself. “Ultimately, education and some level of involvement really will make the difference in who navigates our future as hospitalists,” he said.

Questioning co-management practices

Though he says he’s in the minority, Hardik Vora, MD, SFHM, medical director for hospital medicine at Riverside Regional Medical Center in Newport News, Va., believes that co-management is going to “make or break hospital medicine. It’s going to have a huge impact on our specialty.”

In the roughly 25-year history of hospital medicine, it has evolved from admitting and caring for patients of primary care physicians to patients of specialists and, more recently, surgical patients. “Now there are (hospital medicine) programs across the country that are pretty much admitting everything,” said Dr. Vora.

As a recruiter for the Riverside Health System for the past eight years, “I have not met a single resident who is trained to do what we’re doing in hospital medicine, because you’re admitting surgical patients all the time and you have primary attending responsibility,” Dr. Vora said. “I see that as a cause of a significant amount of stress because now you’re responsible for something that you don’t have adequate training for.”

In the co-management discussion, Dr. Vora notes that people often bring up the research that shows that the practice has improved surgeon satisfaction. “What bothers me is that…you need to add one more question – how does it affect your hospitalists? And I bet the answer to that question is ‘it has a terrible effect.’”

The expectations surrounding hospitalists these days is a big concern in terms of burnout, Dr. Vora said. “We talk a lot about the drivers of burnout, whether it’s schedule or COVID,” he said. The biggest issue when it comes to burnout, as he sees it, is not COVID; it’s when hospitalists are performing tasks that make them feel they aren’t adding value. “I think that’s a huge topic in hospital medicine right now.”

Dr. Vora believes there should be more discussion and awareness of the potential pitfalls. “Hospitalists should get involved in co-management where they are adding value and certainly not take up the attending responsibility where they’re not adding value and it’s out of the scope of their training and expertise,” he said. “Preventing scope creep and burnout from co-management are some of the key issues I’m really passionate about.”

Dr. Vora said it is important to set realistic goals and remember that it takes time to make change when it comes to advocacy. “You still have to operate within whatever environment is given to you and then you can make change from within,” he said.

His enthusiasm for co-management awareness has led to creating a co-management forum through SHM in his local Hampton Roads chapter. He was also a panelist for an SHM webinar in February 2021 in which the panelists debated co-management.

“I think we really need to look at this as a specialty. Are we going in the right direction?” Dr. Vora asked. “We need to come together as a specialty and make a decision, which is going to be hard because there are competing financial interests and various practice models.”

Improving patient care

Working as a hospitalist at University Medical Center, a safety net hospital in New Orleans, Celeste Newby, MD, PhD, sees plenty of patients who are underinsured or not insured at all. “A lot of my interest in health policy stems from that,” she said.

During her residency, which she finished in 2015, Louisiana became a Medicaid expansion state. This impressed upon Dr. Newby how much Medicaid improved the lives of patients who had previously been uninsured. “We saw procedures getting done that had been put on hold because of financial concerns or medicines that were now affordable that weren’t before,” she said. “It really did make a difference.”

When repeated attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act began, “it was a call to do health policy work for me personally that just hadn’t come up in the past,” said Dr. Newby, who is also assistant professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans. “I personally found that the best way to do (advocacy work) was to go through medical societies because there is a much stronger voice when you have more people saying the same thing,” she said.

Dr. Newby sits on the Council of Legislation for the Louisiana State Medical Society and participates in the Leadership and Health Policy (LEAHP) Program through the Society of General Internal Medicine.

The LEAHP Program has been instrumental in expanding Dr. Newby’s knowledge of how health policy is made and the mechanisms behind it. It has also taught her “how we can either advise, guide, leverage, or advocate for things that we think would be important for change and moving the country in the right direction in terms of health care.”

Another reason involvement in medical societies is helpful is because, as a busy clinician, it is impossible to keep up with everything. “Working with medical societies, you have people who are more directly involved in the legislature and can give you quicker notice about things that are coming up that are going to be important to you or your co-workers or your patients,” Dr. Newby said.

Dr. Newby feels her advocacy work is an outlet for stress and “a way to work at more of a macro level on problems that I see with my individual patients. It’s a nice compliment.” At the hospital, she can only help one person at a time, but with her advocacy efforts, there’s potential to make changes for many.

“Advocacy now is such a large umbrella that encompasses so many different projects at all kinds of levels,” Dr. Newby said. She suggests looking around your community to see where the needs lie. If you’re passionate about a certain topic or population, see what you can do to help advocate for change there.

Hospitalists engaging in advocacy efforts

Hospitalists engaging in advocacy efforts

Hospitalists around the country are devoting large portions of their spare time to a wide range of advocacy efforts. From health policy to caring for the unhoused population to diversity and equity to advocating for fellow hospitalists, these physicians are passionate about their causes and determined to make a difference.

Championing the unhoused

Sarah Stella, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health, was initially drawn there because of the population the hospital serves, which includes a high concentration of people experiencing homelessness. As she cared for her patients, Dr. Stella, who is also associate professor of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado, increasingly felt the desire to help prevent the negative downstream outcomes the hospital sees.

To understand the experiences of the unhoused outside the hospital, Dr. Stella started talking to her patients and people in community-based organizations that serve this population. “I learned a ton,” she said. “Homelessness feels like such an intractable, hopeless thing, but the more I talked to people, the more opportunities I saw to work toward something better.”

This led to a pilot grant to work with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to set up a community advisory panel. “My goal was to better understand their experiences and to develop a shared vision for how we collectively can do better,” said Dr. Stella. Eventually, she also received a grant from the University of Colorado, and multiple opportunities have sprung up ever since.

For the past several years, Dr. Stella has worked with Denver Health leadership to improve care for the homeless. “Right now, I’m working with a community team on developing an idea to provide peer support from people with a shared lived experience for people who are experiencing homelessness when they’re hospitalized. That’s really where my passion has been in working on the partnership,” she said.

Her advocacy role has been beneficial in her work as a hospitalist, particularly when COVID began. Dr. Stella again partnered with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to start a joint task force. “Everyone on our task force is motivated by this powerful desire to improve the health and lives of this community and that’s one of the silver linings in this pandemic for me,” said Dr. Stella.

Advocacy work has also increased Dr. Stella’s knowledge of what community support options are available for the unhoused. This allows her to educate her patients about their options and how to access them.

While she has colleagues who are able to compartmentalize their work, “I absolutely could not be a hospitalist without being an advocate,” Dr. Stella said. “For me, it has been a protective strategy in terms of burnout because I have to feel like I’m working to advocate for better policies and more appropriate resources to address the gaps that I’m seeing.”

Dr. Stella believes that physicians have a special credibility to advocate, tell stories, and use data to back their stories up. “We have to realize that we have this power, and we have it so we can empower others,” she said. “The people I’ve seen in my community who are working so hard to help people who are experiencing homelessness are the heroes. Understanding that and giving power to those people through our voice and our well-respected place in society drives me.”

Strengthening diversity, equity, and inclusion

In September 2020, Michael Bryant, MD, became the inaugural vice chair of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the department of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where he is also the division head of pediatric hospital medicine. “I was motivated to apply for this position because I wanted to be an agent for change to eliminate the institutional racism, social injustice, and marginalization that continues to threaten the lives and well-beings of so many Americans,” Dr. Bryant said.

Between the pandemic, the economic decline it has created, and the divisive political landscape, people of color have been especially affected. “These are poignant examples of the ever-widening divide and disenfranchisement many Americans feel,” said Dr. Bryant. “Gandhi said, ‘Be the change that you want to see,’ and that is what I want to model.”

At work, advocacy for diversity, equality, and inclusion is an innate part of everything he does. From the new physicians he recruits to the candidates he considers for leadership positions, Dr. Bryant strives “to have a workforce that mirrors the diversity of the patients we humbly care for and serve.”

Advocacy is intrinsic to Dr. Bryant’s worldview, in his quest to understand and accept each individual’s uniqueness, his desire “to embrace cultural humility,” his recognition that “our differences enhance us instead of diminishing us,” and his willingness to engage in difficult conversations.

“Advocacy means that I acknowledge that intent does not equal impact and that I must accept that what I do and what I say may have unintended consequences,” he said. “When that happens, I must resist becoming defensive and instead be willing to listen and learn.”

Dr. Bryant is proud of his accomplishments and enjoys his advocacy work. In his workplace, there are few African Americans in leadership roles. This means that he is in high demand when it comes to making sure there’s representation during various processes such as hiring and vetting, a disparity known as the “minority tax.”

“I am thankful for the opportunities, but it does take a toll at times,” Dr. Bryant said, which is yet another reason why he is a proponent of increasing diversity and inclusion. “This allows us to build the resource pool as these needs arise and minimizes the toll of the ‘minority tax’ on any single person or small group of individuals.”

This summer, physicians from Dr. Bryant’s hospital participated in the national “White Coats for Black Lives” effort. He found it to be “an incredibly moving event” that hundreds of his colleagues participated in.

Dr. Bryant’s advice for hospitalists who want to get involved in advocacy efforts is to check out the movie “John Lewis: Good Trouble.” “He was a champion of human rights and fought for these rights until his death,” Dr. Bryant said. “He is a true American hero and a wonderful example.”

Bolstering health care change

Since his residency, Joshua Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, has developed an ever-increasing interest in legislative advocacy, particularly health policy. Getting involved in this arena requires an understanding of civics and government that goes beyond just the basics. “My desire to affect change in my own profession really served as the catalyst to get involved,” said Dr. Lenchus, the regional chief medical officer at Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “What better way to do that than by combining what we do on a daily basis in the practice of medicine with this new understanding of how laws are passed and promulgated?”

Dr. Lenchus has been involved with both state and national medical organizations and has served on public policy committees as a member and as a chair. “The charge of these committees is to monitor and navigate position statements and policies that will drive the entire organization,” he said. This means becoming knowledgeable enough about a topic to be able to talk about it eloquently and adding supporting personal or professional illustrations that reinforce the position to lawmakers.

He finds his advocacy efforts “incredibly rewarding” because they contribute to his endeavors “to help my colleagues practice medicine in a safe, efficient, and productive manner.” For instance, some of the organizations Dr. Lenchus was involved with helped make changes to the Affordable Care Act that ended up in its final version, as well as changes after it passed. “There are tangible things that advocacy enables us to do in our daily practice,” he said.

When something his organizations have advocated for does not pass, they know they need to try a different outlet. “You can’t win every fight,” he said. “Every time you go and comment on an issue, you have to understand that you’re there to do your best, and to the extent that the people you’re talking to are willing to listen to what you have to say, that’s where I think you can make the most impact.” When changes he has helped fight for do pass, “it really is amazing that you can tell your colleagues about your role in achieving meaningful change in the profession.”

Dr. Lenchus acknowledges that advocacy “can be all-consuming at times. We have to understand our limits.” That said, he thinks not engaging in advocacy could increase stress and potential burnout. “I think being involved in advocacy efforts really helps people conduct meaningful work and educates them about what it means not just to them, but to the rest of the medical profession and the patients that we serve,” he said.

For hospitalists who are interested in health policy advocacy, there are many ways to get involved, Dr. Lenchus said. You could join an organization (many organized medical societies have public policy committees), participate in advocacy activities, work on a political campaign, or even run for office yourself. “Ultimately, education and some level of involvement really will make the difference in who navigates our future as hospitalists,” he said.

Questioning co-management practices

Though he says he’s in the minority, Hardik Vora, MD, SFHM, medical director for hospital medicine at Riverside Regional Medical Center in Newport News, Va., believes that co-management is going to “make or break hospital medicine. It’s going to have a huge impact on our specialty.”

In the roughly 25-year history of hospital medicine, it has evolved from admitting and caring for patients of primary care physicians to patients of specialists and, more recently, surgical patients. “Now there are (hospital medicine) programs across the country that are pretty much admitting everything,” said Dr. Vora.

As a recruiter for the Riverside Health System for the past eight years, “I have not met a single resident who is trained to do what we’re doing in hospital medicine, because you’re admitting surgical patients all the time and you have primary attending responsibility,” Dr. Vora said. “I see that as a cause of a significant amount of stress because now you’re responsible for something that you don’t have adequate training for.”

In the co-management discussion, Dr. Vora notes that people often bring up the research that shows that the practice has improved surgeon satisfaction. “What bothers me is that…you need to add one more question – how does it affect your hospitalists? And I bet the answer to that question is ‘it has a terrible effect.’”

The expectations surrounding hospitalists these days is a big concern in terms of burnout, Dr. Vora said. “We talk a lot about the drivers of burnout, whether it’s schedule or COVID,” he said. The biggest issue when it comes to burnout, as he sees it, is not COVID; it’s when hospitalists are performing tasks that make them feel they aren’t adding value. “I think that’s a huge topic in hospital medicine right now.”

Dr. Vora believes there should be more discussion and awareness of the potential pitfalls. “Hospitalists should get involved in co-management where they are adding value and certainly not take up the attending responsibility where they’re not adding value and it’s out of the scope of their training and expertise,” he said. “Preventing scope creep and burnout from co-management are some of the key issues I’m really passionate about.”

Dr. Vora said it is important to set realistic goals and remember that it takes time to make change when it comes to advocacy. “You still have to operate within whatever environment is given to you and then you can make change from within,” he said.

His enthusiasm for co-management awareness has led to creating a co-management forum through SHM in his local Hampton Roads chapter. He was also a panelist for an SHM webinar in February 2021 in which the panelists debated co-management.

“I think we really need to look at this as a specialty. Are we going in the right direction?” Dr. Vora asked. “We need to come together as a specialty and make a decision, which is going to be hard because there are competing financial interests and various practice models.”

Improving patient care

Working as a hospitalist at University Medical Center, a safety net hospital in New Orleans, Celeste Newby, MD, PhD, sees plenty of patients who are underinsured or not insured at all. “A lot of my interest in health policy stems from that,” she said.

During her residency, which she finished in 2015, Louisiana became a Medicaid expansion state. This impressed upon Dr. Newby how much Medicaid improved the lives of patients who had previously been uninsured. “We saw procedures getting done that had been put on hold because of financial concerns or medicines that were now affordable that weren’t before,” she said. “It really did make a difference.”

When repeated attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act began, “it was a call to do health policy work for me personally that just hadn’t come up in the past,” said Dr. Newby, who is also assistant professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans. “I personally found that the best way to do (advocacy work) was to go through medical societies because there is a much stronger voice when you have more people saying the same thing,” she said.

Dr. Newby sits on the Council of Legislation for the Louisiana State Medical Society and participates in the Leadership and Health Policy (LEAHP) Program through the Society of General Internal Medicine.

The LEAHP Program has been instrumental in expanding Dr. Newby’s knowledge of how health policy is made and the mechanisms behind it. It has also taught her “how we can either advise, guide, leverage, or advocate for things that we think would be important for change and moving the country in the right direction in terms of health care.”

Another reason involvement in medical societies is helpful is because, as a busy clinician, it is impossible to keep up with everything. “Working with medical societies, you have people who are more directly involved in the legislature and can give you quicker notice about things that are coming up that are going to be important to you or your co-workers or your patients,” Dr. Newby said.

Dr. Newby feels her advocacy work is an outlet for stress and “a way to work at more of a macro level on problems that I see with my individual patients. It’s a nice compliment.” At the hospital, she can only help one person at a time, but with her advocacy efforts, there’s potential to make changes for many.

“Advocacy now is such a large umbrella that encompasses so many different projects at all kinds of levels,” Dr. Newby said. She suggests looking around your community to see where the needs lie. If you’re passionate about a certain topic or population, see what you can do to help advocate for change there.

Hospitalists around the country are devoting large portions of their spare time to a wide range of advocacy efforts. From health policy to caring for the unhoused population to diversity and equity to advocating for fellow hospitalists, these physicians are passionate about their causes and determined to make a difference.

Championing the unhoused

Sarah Stella, MD, FHM, a hospitalist at Denver Health, was initially drawn there because of the population the hospital serves, which includes a high concentration of people experiencing homelessness. As she cared for her patients, Dr. Stella, who is also associate professor of hospital medicine at the University of Colorado, increasingly felt the desire to help prevent the negative downstream outcomes the hospital sees.

To understand the experiences of the unhoused outside the hospital, Dr. Stella started talking to her patients and people in community-based organizations that serve this population. “I learned a ton,” she said. “Homelessness feels like such an intractable, hopeless thing, but the more I talked to people, the more opportunities I saw to work toward something better.”

This led to a pilot grant to work with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to set up a community advisory panel. “My goal was to better understand their experiences and to develop a shared vision for how we collectively can do better,” said Dr. Stella. Eventually, she also received a grant from the University of Colorado, and multiple opportunities have sprung up ever since.

For the past several years, Dr. Stella has worked with Denver Health leadership to improve care for the homeless. “Right now, I’m working with a community team on developing an idea to provide peer support from people with a shared lived experience for people who are experiencing homelessness when they’re hospitalized. That’s really where my passion has been in working on the partnership,” she said.

Her advocacy role has been beneficial in her work as a hospitalist, particularly when COVID began. Dr. Stella again partnered with the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless to start a joint task force. “Everyone on our task force is motivated by this powerful desire to improve the health and lives of this community and that’s one of the silver linings in this pandemic for me,” said Dr. Stella.

Advocacy work has also increased Dr. Stella’s knowledge of what community support options are available for the unhoused. This allows her to educate her patients about their options and how to access them.

While she has colleagues who are able to compartmentalize their work, “I absolutely could not be a hospitalist without being an advocate,” Dr. Stella said. “For me, it has been a protective strategy in terms of burnout because I have to feel like I’m working to advocate for better policies and more appropriate resources to address the gaps that I’m seeing.”

Dr. Stella believes that physicians have a special credibility to advocate, tell stories, and use data to back their stories up. “We have to realize that we have this power, and we have it so we can empower others,” she said. “The people I’ve seen in my community who are working so hard to help people who are experiencing homelessness are the heroes. Understanding that and giving power to those people through our voice and our well-respected place in society drives me.”

Strengthening diversity, equity, and inclusion

In September 2020, Michael Bryant, MD, became the inaugural vice chair of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for the department of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, where he is also the division head of pediatric hospital medicine. “I was motivated to apply for this position because I wanted to be an agent for change to eliminate the institutional racism, social injustice, and marginalization that continues to threaten the lives and well-beings of so many Americans,” Dr. Bryant said.

Between the pandemic, the economic decline it has created, and the divisive political landscape, people of color have been especially affected. “These are poignant examples of the ever-widening divide and disenfranchisement many Americans feel,” said Dr. Bryant. “Gandhi said, ‘Be the change that you want to see,’ and that is what I want to model.”

At work, advocacy for diversity, equality, and inclusion is an innate part of everything he does. From the new physicians he recruits to the candidates he considers for leadership positions, Dr. Bryant strives “to have a workforce that mirrors the diversity of the patients we humbly care for and serve.”

Advocacy is intrinsic to Dr. Bryant’s worldview, in his quest to understand and accept each individual’s uniqueness, his desire “to embrace cultural humility,” his recognition that “our differences enhance us instead of diminishing us,” and his willingness to engage in difficult conversations.

“Advocacy means that I acknowledge that intent does not equal impact and that I must accept that what I do and what I say may have unintended consequences,” he said. “When that happens, I must resist becoming defensive and instead be willing to listen and learn.”

Dr. Bryant is proud of his accomplishments and enjoys his advocacy work. In his workplace, there are few African Americans in leadership roles. This means that he is in high demand when it comes to making sure there’s representation during various processes such as hiring and vetting, a disparity known as the “minority tax.”

“I am thankful for the opportunities, but it does take a toll at times,” Dr. Bryant said, which is yet another reason why he is a proponent of increasing diversity and inclusion. “This allows us to build the resource pool as these needs arise and minimizes the toll of the ‘minority tax’ on any single person or small group of individuals.”

This summer, physicians from Dr. Bryant’s hospital participated in the national “White Coats for Black Lives” effort. He found it to be “an incredibly moving event” that hundreds of his colleagues participated in.

Dr. Bryant’s advice for hospitalists who want to get involved in advocacy efforts is to check out the movie “John Lewis: Good Trouble.” “He was a champion of human rights and fought for these rights until his death,” Dr. Bryant said. “He is a true American hero and a wonderful example.”

Bolstering health care change

Since his residency, Joshua Lenchus, DO, FACP, SFHM, has developed an ever-increasing interest in legislative advocacy, particularly health policy. Getting involved in this arena requires an understanding of civics and government that goes beyond just the basics. “My desire to affect change in my own profession really served as the catalyst to get involved,” said Dr. Lenchus, the regional chief medical officer at Broward Health Medical Center in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. “What better way to do that than by combining what we do on a daily basis in the practice of medicine with this new understanding of how laws are passed and promulgated?”

Dr. Lenchus has been involved with both state and national medical organizations and has served on public policy committees as a member and as a chair. “The charge of these committees is to monitor and navigate position statements and policies that will drive the entire organization,” he said. This means becoming knowledgeable enough about a topic to be able to talk about it eloquently and adding supporting personal or professional illustrations that reinforce the position to lawmakers.

He finds his advocacy efforts “incredibly rewarding” because they contribute to his endeavors “to help my colleagues practice medicine in a safe, efficient, and productive manner.” For instance, some of the organizations Dr. Lenchus was involved with helped make changes to the Affordable Care Act that ended up in its final version, as well as changes after it passed. “There are tangible things that advocacy enables us to do in our daily practice,” he said.

When something his organizations have advocated for does not pass, they know they need to try a different outlet. “You can’t win every fight,” he said. “Every time you go and comment on an issue, you have to understand that you’re there to do your best, and to the extent that the people you’re talking to are willing to listen to what you have to say, that’s where I think you can make the most impact.” When changes he has helped fight for do pass, “it really is amazing that you can tell your colleagues about your role in achieving meaningful change in the profession.”

Dr. Lenchus acknowledges that advocacy “can be all-consuming at times. We have to understand our limits.” That said, he thinks not engaging in advocacy could increase stress and potential burnout. “I think being involved in advocacy efforts really helps people conduct meaningful work and educates them about what it means not just to them, but to the rest of the medical profession and the patients that we serve,” he said.

For hospitalists who are interested in health policy advocacy, there are many ways to get involved, Dr. Lenchus said. You could join an organization (many organized medical societies have public policy committees), participate in advocacy activities, work on a political campaign, or even run for office yourself. “Ultimately, education and some level of involvement really will make the difference in who navigates our future as hospitalists,” he said.

Questioning co-management practices

Though he says he’s in the minority, Hardik Vora, MD, SFHM, medical director for hospital medicine at Riverside Regional Medical Center in Newport News, Va., believes that co-management is going to “make or break hospital medicine. It’s going to have a huge impact on our specialty.”

In the roughly 25-year history of hospital medicine, it has evolved from admitting and caring for patients of primary care physicians to patients of specialists and, more recently, surgical patients. “Now there are (hospital medicine) programs across the country that are pretty much admitting everything,” said Dr. Vora.

As a recruiter for the Riverside Health System for the past eight years, “I have not met a single resident who is trained to do what we’re doing in hospital medicine, because you’re admitting surgical patients all the time and you have primary attending responsibility,” Dr. Vora said. “I see that as a cause of a significant amount of stress because now you’re responsible for something that you don’t have adequate training for.”

In the co-management discussion, Dr. Vora notes that people often bring up the research that shows that the practice has improved surgeon satisfaction. “What bothers me is that…you need to add one more question – how does it affect your hospitalists? And I bet the answer to that question is ‘it has a terrible effect.’”

The expectations surrounding hospitalists these days is a big concern in terms of burnout, Dr. Vora said. “We talk a lot about the drivers of burnout, whether it’s schedule or COVID,” he said. The biggest issue when it comes to burnout, as he sees it, is not COVID; it’s when hospitalists are performing tasks that make them feel they aren’t adding value. “I think that’s a huge topic in hospital medicine right now.”

Dr. Vora believes there should be more discussion and awareness of the potential pitfalls. “Hospitalists should get involved in co-management where they are adding value and certainly not take up the attending responsibility where they’re not adding value and it’s out of the scope of their training and expertise,” he said. “Preventing scope creep and burnout from co-management are some of the key issues I’m really passionate about.”

Dr. Vora said it is important to set realistic goals and remember that it takes time to make change when it comes to advocacy. “You still have to operate within whatever environment is given to you and then you can make change from within,” he said.

His enthusiasm for co-management awareness has led to creating a co-management forum through SHM in his local Hampton Roads chapter. He was also a panelist for an SHM webinar in February 2021 in which the panelists debated co-management.

“I think we really need to look at this as a specialty. Are we going in the right direction?” Dr. Vora asked. “We need to come together as a specialty and make a decision, which is going to be hard because there are competing financial interests and various practice models.”

Improving patient care

Working as a hospitalist at University Medical Center, a safety net hospital in New Orleans, Celeste Newby, MD, PhD, sees plenty of patients who are underinsured or not insured at all. “A lot of my interest in health policy stems from that,” she said.

During her residency, which she finished in 2015, Louisiana became a Medicaid expansion state. This impressed upon Dr. Newby how much Medicaid improved the lives of patients who had previously been uninsured. “We saw procedures getting done that had been put on hold because of financial concerns or medicines that were now affordable that weren’t before,” she said. “It really did make a difference.”

When repeated attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act began, “it was a call to do health policy work for me personally that just hadn’t come up in the past,” said Dr. Newby, who is also assistant professor of medicine at Tulane University in New Orleans. “I personally found that the best way to do (advocacy work) was to go through medical societies because there is a much stronger voice when you have more people saying the same thing,” she said.

Dr. Newby sits on the Council of Legislation for the Louisiana State Medical Society and participates in the Leadership and Health Policy (LEAHP) Program through the Society of General Internal Medicine.

The LEAHP Program has been instrumental in expanding Dr. Newby’s knowledge of how health policy is made and the mechanisms behind it. It has also taught her “how we can either advise, guide, leverage, or advocate for things that we think would be important for change and moving the country in the right direction in terms of health care.”

Another reason involvement in medical societies is helpful is because, as a busy clinician, it is impossible to keep up with everything. “Working with medical societies, you have people who are more directly involved in the legislature and can give you quicker notice about things that are coming up that are going to be important to you or your co-workers or your patients,” Dr. Newby said.

Dr. Newby feels her advocacy work is an outlet for stress and “a way to work at more of a macro level on problems that I see with my individual patients. It’s a nice compliment.” At the hospital, she can only help one person at a time, but with her advocacy efforts, there’s potential to make changes for many.

“Advocacy now is such a large umbrella that encompasses so many different projects at all kinds of levels,” Dr. Newby said. She suggests looking around your community to see where the needs lie. If you’re passionate about a certain topic or population, see what you can do to help advocate for change there.

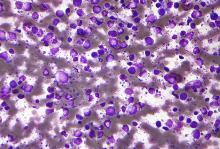

Low-calorie diet linked to improved chemo response in leukemia

Children and adolescents with leukemia who were placed on a restrictive diet and exercise regimen concurrent with starting chemotherapy showed responses to treatment that were better than those historically seen in such patients.

This apparently improved response suggests it is possible to boost treatment efficacy without raising the dose – or toxicity – of chemotherapy.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study in any hematologic malignancy to demonstrate potential benefit from caloric restriction via diet and exercise to augment chemotherapy efficacy and improve disease response, the authors reported.

The findings come from the IDEAL pilot trial, conducted in 40 young patients (mean age, 15 years; range, 10-21 years) diagnosed with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

The study was published online April 1 in Blood Advances.

The diet and exercise regimen is a departure from current recommendations for patients with leukemia.

“This was a major paradigm shift – until now, many oncologists encouraged ‘comfort foods’ and increased calories to get through the rigor of chemotherapy,” first author Etan Orgel, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California, also in Los Angeles.

The results from this pilot trial suggest that “the era of encouraging comfort food should be in the past; over-nutrition is likely harmful, and diet and exercise are important tools to harness during chemotherapy,” he said.

Dr. Orgel added that childhood ALL was selected because it is the most common cancer of childhood, but the findings could have potential relevance in other cancer types in children as well as adults.

Commenting on the study, Patrick Brown, MD, director of the pediatric leukemia program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said the findings are important, albeit preliminary.

“I think the most important contribution of this pilot study is to show that it is possible to change the nutrition and exercise habits of children and adolescents during the initial month of treatment for ALL,” he said in an interview.

“We have to be cautious about the preliminary finding that these changes resulted in deeper remissions – this will need to be confirmed in a larger study,” added Dr. Brown, who was not involved with the research.

Dr. Orgel noted that a prospective, randomized trial, IDEAL-2, is launching later this year to further evaluate the intervention.

Obesity linked to poorer chemotherapy response

Among children and adolescents who start treatment for B-ALL, as many as 40% are overweight or obese, noted the study authors.

Those who are obese have more than a twofold greater risk of having persistent minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of chemotherapy, considered the strongest patient-level predictor of poor outcome and a common guide for therapy intensification.

The problem is compounded by weight gain that is common during treatment as a result of prolonged chemotherapy and sedentary behavior, they commented.

With studies of obese mice linking calorie and fat restriction to improved survival after chemotherapy, the authors theorized that a calorie- and fat-restrictive diet and exercise could help improve outcomes after chemotherapy in humans.

Participants were enrolled at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and City of Hope National Medical Center in nearby Duarte. After they were started on chemotherapy, they were placed on a low-carb, low-fat, and low-sugar diet tailored to patient needs and preferences, as well as a moderate daily exercise regimen, and continued on this regimen throughout the 4-week induction phase.

Following the intervention, there were no significant reductions observed in median gain of fat mass at the end of the intervention, compared with baseline (P = .13). However, in the subgroup of patients who were overweight or obese at baseline, the reduction in fat mass was indeed significant versus baseline (+1.5% vs. +9.7% at baseline; P = .02).

Importantly, after adjustment for prognostic factors, adherence to the intervention was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of MRD, compared with recent historical controls who received the same induction therapy at the same institution, but no intervention (odds ratio, 0.30; P = .02).

The intervention was also associated with a lower detectable MRD, compared with the historical controls (OR, 0.16; one-sided P = .002).

“Most importantly, the IDEAL intervention reduced risk of MRD at the end of induction in all patients, irrespective of starting [body mass index] and after accounting for prognostic features,” the authors noted.

Adherence to diet high, exercise low

As many as 82% of study participants achieved the goal of 20% or more caloric deficit throughout the chemotherapy.

“Adherence to the diet was excellent, with caloric deficits and macronutrient goals achieved in nearly all patients, including in the lean group,” the authors reported.

Dr. Orgel added that families embraced the chance to play an active role in the cancer therapy. “In our view, they couldn’t control their disease or their chemotherapy, but this, they could,” he said.

Conversely, adherence to the prescribed exercise was low – just 31.2%, with the inactivity during the first month likely contributed to the similar loss of muscle mass that occurred in both cohorts, Dr. Orgel noted.

“The [low exercise adherence] unfortunately was not a surprise, as it is often difficult to exercise and be active during chemotherapy,” he said.

Key aspects of physical activity will be refined in further studies, Dr. Orgel added.

Insulin sensitivity, adiponectin key factors?

Patients receiving the intervention showed improved insulin sensitivity and reductions in circulating insulin, which are notable in that insulin has been linked to mechanisms that counter chemoresistance, the authors noted.

Furthermore, the decreases in insulin were accompanied by notable elevations in circulating adiponectin, a protein hormone produced and secreted by fat cells.

“Adiponectin was certainly a surprise, as until now it did not appear to play a major role in cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy,” Dr. Orgel said.

“It is too soon to say they are central to the mechanism of the intervention, but the large differences in adiponectin and insulin sensitivity found in children in the trial have definitely highlighted these as important for future study,” he added.

Dr. Orgel, the study coauthors, and Dr. Brown disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and adolescents with leukemia who were placed on a restrictive diet and exercise regimen concurrent with starting chemotherapy showed responses to treatment that were better than those historically seen in such patients.

This apparently improved response suggests it is possible to boost treatment efficacy without raising the dose – or toxicity – of chemotherapy.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study in any hematologic malignancy to demonstrate potential benefit from caloric restriction via diet and exercise to augment chemotherapy efficacy and improve disease response, the authors reported.

The findings come from the IDEAL pilot trial, conducted in 40 young patients (mean age, 15 years; range, 10-21 years) diagnosed with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

The study was published online April 1 in Blood Advances.

The diet and exercise regimen is a departure from current recommendations for patients with leukemia.

“This was a major paradigm shift – until now, many oncologists encouraged ‘comfort foods’ and increased calories to get through the rigor of chemotherapy,” first author Etan Orgel, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California, also in Los Angeles.

The results from this pilot trial suggest that “the era of encouraging comfort food should be in the past; over-nutrition is likely harmful, and diet and exercise are important tools to harness during chemotherapy,” he said.

Dr. Orgel added that childhood ALL was selected because it is the most common cancer of childhood, but the findings could have potential relevance in other cancer types in children as well as adults.

Commenting on the study, Patrick Brown, MD, director of the pediatric leukemia program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said the findings are important, albeit preliminary.

“I think the most important contribution of this pilot study is to show that it is possible to change the nutrition and exercise habits of children and adolescents during the initial month of treatment for ALL,” he said in an interview.

“We have to be cautious about the preliminary finding that these changes resulted in deeper remissions – this will need to be confirmed in a larger study,” added Dr. Brown, who was not involved with the research.

Dr. Orgel noted that a prospective, randomized trial, IDEAL-2, is launching later this year to further evaluate the intervention.

Obesity linked to poorer chemotherapy response

Among children and adolescents who start treatment for B-ALL, as many as 40% are overweight or obese, noted the study authors.

Those who are obese have more than a twofold greater risk of having persistent minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of chemotherapy, considered the strongest patient-level predictor of poor outcome and a common guide for therapy intensification.

The problem is compounded by weight gain that is common during treatment as a result of prolonged chemotherapy and sedentary behavior, they commented.

With studies of obese mice linking calorie and fat restriction to improved survival after chemotherapy, the authors theorized that a calorie- and fat-restrictive diet and exercise could help improve outcomes after chemotherapy in humans.

Participants were enrolled at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and City of Hope National Medical Center in nearby Duarte. After they were started on chemotherapy, they were placed on a low-carb, low-fat, and low-sugar diet tailored to patient needs and preferences, as well as a moderate daily exercise regimen, and continued on this regimen throughout the 4-week induction phase.

Following the intervention, there were no significant reductions observed in median gain of fat mass at the end of the intervention, compared with baseline (P = .13). However, in the subgroup of patients who were overweight or obese at baseline, the reduction in fat mass was indeed significant versus baseline (+1.5% vs. +9.7% at baseline; P = .02).

Importantly, after adjustment for prognostic factors, adherence to the intervention was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of MRD, compared with recent historical controls who received the same induction therapy at the same institution, but no intervention (odds ratio, 0.30; P = .02).

The intervention was also associated with a lower detectable MRD, compared with the historical controls (OR, 0.16; one-sided P = .002).

“Most importantly, the IDEAL intervention reduced risk of MRD at the end of induction in all patients, irrespective of starting [body mass index] and after accounting for prognostic features,” the authors noted.

Adherence to diet high, exercise low

As many as 82% of study participants achieved the goal of 20% or more caloric deficit throughout the chemotherapy.

“Adherence to the diet was excellent, with caloric deficits and macronutrient goals achieved in nearly all patients, including in the lean group,” the authors reported.

Dr. Orgel added that families embraced the chance to play an active role in the cancer therapy. “In our view, they couldn’t control their disease or their chemotherapy, but this, they could,” he said.

Conversely, adherence to the prescribed exercise was low – just 31.2%, with the inactivity during the first month likely contributed to the similar loss of muscle mass that occurred in both cohorts, Dr. Orgel noted.

“The [low exercise adherence] unfortunately was not a surprise, as it is often difficult to exercise and be active during chemotherapy,” he said.

Key aspects of physical activity will be refined in further studies, Dr. Orgel added.

Insulin sensitivity, adiponectin key factors?

Patients receiving the intervention showed improved insulin sensitivity and reductions in circulating insulin, which are notable in that insulin has been linked to mechanisms that counter chemoresistance, the authors noted.

Furthermore, the decreases in insulin were accompanied by notable elevations in circulating adiponectin, a protein hormone produced and secreted by fat cells.

“Adiponectin was certainly a surprise, as until now it did not appear to play a major role in cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy,” Dr. Orgel said.

“It is too soon to say they are central to the mechanism of the intervention, but the large differences in adiponectin and insulin sensitivity found in children in the trial have definitely highlighted these as important for future study,” he added.

Dr. Orgel, the study coauthors, and Dr. Brown disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Children and adolescents with leukemia who were placed on a restrictive diet and exercise regimen concurrent with starting chemotherapy showed responses to treatment that were better than those historically seen in such patients.

This apparently improved response suggests it is possible to boost treatment efficacy without raising the dose – or toxicity – of chemotherapy.

“To our knowledge, this is the first study in any hematologic malignancy to demonstrate potential benefit from caloric restriction via diet and exercise to augment chemotherapy efficacy and improve disease response, the authors reported.

The findings come from the IDEAL pilot trial, conducted in 40 young patients (mean age, 15 years; range, 10-21 years) diagnosed with high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

The study was published online April 1 in Blood Advances.

The diet and exercise regimen is a departure from current recommendations for patients with leukemia.

“This was a major paradigm shift – until now, many oncologists encouraged ‘comfort foods’ and increased calories to get through the rigor of chemotherapy,” first author Etan Orgel, MD, of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California, also in Los Angeles.

The results from this pilot trial suggest that “the era of encouraging comfort food should be in the past; over-nutrition is likely harmful, and diet and exercise are important tools to harness during chemotherapy,” he said.

Dr. Orgel added that childhood ALL was selected because it is the most common cancer of childhood, but the findings could have potential relevance in other cancer types in children as well as adults.

Commenting on the study, Patrick Brown, MD, director of the pediatric leukemia program at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said the findings are important, albeit preliminary.

“I think the most important contribution of this pilot study is to show that it is possible to change the nutrition and exercise habits of children and adolescents during the initial month of treatment for ALL,” he said in an interview.

“We have to be cautious about the preliminary finding that these changes resulted in deeper remissions – this will need to be confirmed in a larger study,” added Dr. Brown, who was not involved with the research.

Dr. Orgel noted that a prospective, randomized trial, IDEAL-2, is launching later this year to further evaluate the intervention.

Obesity linked to poorer chemotherapy response

Among children and adolescents who start treatment for B-ALL, as many as 40% are overweight or obese, noted the study authors.

Those who are obese have more than a twofold greater risk of having persistent minimal residual disease (MRD) at the end of chemotherapy, considered the strongest patient-level predictor of poor outcome and a common guide for therapy intensification.

The problem is compounded by weight gain that is common during treatment as a result of prolonged chemotherapy and sedentary behavior, they commented.

With studies of obese mice linking calorie and fat restriction to improved survival after chemotherapy, the authors theorized that a calorie- and fat-restrictive diet and exercise could help improve outcomes after chemotherapy in humans.

Participants were enrolled at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and City of Hope National Medical Center in nearby Duarte. After they were started on chemotherapy, they were placed on a low-carb, low-fat, and low-sugar diet tailored to patient needs and preferences, as well as a moderate daily exercise regimen, and continued on this regimen throughout the 4-week induction phase.

Following the intervention, there were no significant reductions observed in median gain of fat mass at the end of the intervention, compared with baseline (P = .13). However, in the subgroup of patients who were overweight or obese at baseline, the reduction in fat mass was indeed significant versus baseline (+1.5% vs. +9.7% at baseline; P = .02).

Importantly, after adjustment for prognostic factors, adherence to the intervention was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of MRD, compared with recent historical controls who received the same induction therapy at the same institution, but no intervention (odds ratio, 0.30; P = .02).

The intervention was also associated with a lower detectable MRD, compared with the historical controls (OR, 0.16; one-sided P = .002).

“Most importantly, the IDEAL intervention reduced risk of MRD at the end of induction in all patients, irrespective of starting [body mass index] and after accounting for prognostic features,” the authors noted.

Adherence to diet high, exercise low

As many as 82% of study participants achieved the goal of 20% or more caloric deficit throughout the chemotherapy.

“Adherence to the diet was excellent, with caloric deficits and macronutrient goals achieved in nearly all patients, including in the lean group,” the authors reported.

Dr. Orgel added that families embraced the chance to play an active role in the cancer therapy. “In our view, they couldn’t control their disease or their chemotherapy, but this, they could,” he said.

Conversely, adherence to the prescribed exercise was low – just 31.2%, with the inactivity during the first month likely contributed to the similar loss of muscle mass that occurred in both cohorts, Dr. Orgel noted.

“The [low exercise adherence] unfortunately was not a surprise, as it is often difficult to exercise and be active during chemotherapy,” he said.

Key aspects of physical activity will be refined in further studies, Dr. Orgel added.

Insulin sensitivity, adiponectin key factors?

Patients receiving the intervention showed improved insulin sensitivity and reductions in circulating insulin, which are notable in that insulin has been linked to mechanisms that counter chemoresistance, the authors noted.

Furthermore, the decreases in insulin were accompanied by notable elevations in circulating adiponectin, a protein hormone produced and secreted by fat cells.

“Adiponectin was certainly a surprise, as until now it did not appear to play a major role in cancer cell resistance to chemotherapy,” Dr. Orgel said.

“It is too soon to say they are central to the mechanism of the intervention, but the large differences in adiponectin and insulin sensitivity found in children in the trial have definitely highlighted these as important for future study,” he added.

Dr. Orgel, the study coauthors, and Dr. Brown disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Helping psychiatric patients heal holistically

When I was asked to write a regular “Holistic Mental Health” column, I decided to write about the Herculean forces that must come together to create a holistic psychiatrist – someone who specializes in helping patients off their medications rather than on.

My journey began when I told a training psychiatrist that I wanted to stop being a psychiatrist. It was a year after my daughter was born, and I had started my third year of adult psychiatry residency at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. I was stressed and exhausted from working on inpatient psychiatric wards for 2 years, countless unpleasant nights on call, and additional sleepless nights caring for an infant.

I told the training psychiatrist that life wasn’t worth living. Was I suicidal, he asked? I laughed bitterly: “All the time!” Once he heard the S-word, he wanted me to take an antidepressant. I finally gave in and began taking Zoloft 25 mg every morning. Within a week, my angst disappeared; but 5 years, another child, and a fellowship later, I was still taking Zoloft. Why? Without much thought, I stopped it. A month later, I found myself brooding on the sofa, numb with depression, and feeling astonishingly suicidal. This “depression” led me to restart my Zoloft. In a week, my mood normalized. I did this on and off for about a year until a light bulb went off: This can’t be depression. It’s withdrawal. I’ve become dependent on Zoloft! Once I realized this, I began taking some St. John’s wort, an herbal alternative that was supposed to help with depression. I used cheaper brands and discovered that brands do matter, because the cheaper ones didn’t work. Through my haphazard exploration of natural alternatives, I came off Zoloft completely. During this time, I developed greater empathy for my patients, openness to natural alternatives, appreciation for supplement quality, and learned about psychotropic withdrawal. Most importantly, I came to understand a patient’s need to be free.

Five years later, in 2002, I had a thriving, but conventional, private practice. Instead of being content, however, I once again wanted to quit psychiatry. Medicating patients felt unrewarding, but I didn’t have another approach. Simultaneously, my practice was filling up with chronically ill, heavily medicated, bipolar patients. Their intense suffering combined with my discontent with psychiatry made me desperate for something better. In this ripe setting, the mother of a patient with bipolar disorder casually mentioned a supplement called EMPower by Truehope that lessened bipolar symptoms. Though my withdrawal from Zoloft allowed me to be more open to holistic approaches, I waited 3 months before calling. I used the supplement for the first time to help a heavily medicated bipolar patient in her 30’s, whose Depakote side effects caused her to wear a diaper, lack any emotions, and suffer severe tremors. Once I made this decision to walk down this new path, I never went back. With guidance from the company, I used this supplement to help many patients lower their medications. At the time, I wondered whether EMPower would be the solution for all my patients. The simplicity and ease of one supplement approach for all mental illnesses appealed to my laziness, so I continued down the holistic path.

Hundreds of supplements, glandulars, essential oils, and homeopathic remedies later, I learned that every patient requires their own unique approach. A year into using the supplement, I discovered that, if patients took too much of it, their old symptoms would reappear. Eventually, I moved out of my comfort zone and tried other supplements. Subsequently, the universe orchestrated two people to tell me about the miraculous outcomes from “thought-field therapy,” an energy-medicine technique. I began exploring “energy medicine” through the support and instruction of a holistic psychotherapist, Mark Bottinick, LCSW-C. Soon, I was connecting the dots between emotional freedom technique and immediate positive changes. Energy medicine allowed me to heal problems without using a pill! I felt as if I had arrived at Solla Sollew by the banks of the Beautiful River Wah-Hoo.

As I discovered and attended conferences in holistic medicine, I got certified in integrative medicine and became a Reiki master. Even as a novice in holistic medicine, I began to experience patients crying with joy, rather than sadness. One psychotic patient got better on some supplements and got a new job in just 2 weeks.

On Feb. 17, 2021, I launched a podcast called “The Holistic Psychiatrist,” with interviews of patients, conversations with practitioners, and insights from me. Of the initial interviews, two of the three patients had bipolar disorder, and were able to safely and successfully withdraw from many medications. They are no longer patients and are free to move on with their lives. A patient who smoothly and successfully lowered six psychiatric medications will be sharing her wisdom and healing journey soon. A naturopathic doctor will also be sharing his insights and successes. He once was a suicidal high school student failing his classes, depressed and anxious, and dependent on marijuana. His recovery occurred more than a decade ago in my holistic practice.

These patients are living proof that holistic approaches can be very powerful and effective. They demonstrate that chronicity may reflect inadequate treatment and not a definition of disease. Over the course of this Holistic Mental Health column, I want to share many incredible healing journeys and insights on holistic psychiatry. I hope that you will be open to this new paradigm and begin your own holistic journey.

Dr. Lee is a psychiatrist with a solo private practice in Lehi, Utah. She integrates functional/orthomolecular medicine and mind/body/energy medicine in her work with patients. Contact her at holisticpsychiatrist.com. She has no conflicts of interest.

When I was asked to write a regular “Holistic Mental Health” column, I decided to write about the Herculean forces that must come together to create a holistic psychiatrist – someone who specializes in helping patients off their medications rather than on.

My journey began when I told a training psychiatrist that I wanted to stop being a psychiatrist. It was a year after my daughter was born, and I had started my third year of adult psychiatry residency at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. I was stressed and exhausted from working on inpatient psychiatric wards for 2 years, countless unpleasant nights on call, and additional sleepless nights caring for an infant.

I told the training psychiatrist that life wasn’t worth living. Was I suicidal, he asked? I laughed bitterly: “All the time!” Once he heard the S-word, he wanted me to take an antidepressant. I finally gave in and began taking Zoloft 25 mg every morning. Within a week, my angst disappeared; but 5 years, another child, and a fellowship later, I was still taking Zoloft. Why? Without much thought, I stopped it. A month later, I found myself brooding on the sofa, numb with depression, and feeling astonishingly suicidal. This “depression” led me to restart my Zoloft. In a week, my mood normalized. I did this on and off for about a year until a light bulb went off: This can’t be depression. It’s withdrawal. I’ve become dependent on Zoloft! Once I realized this, I began taking some St. John’s wort, an herbal alternative that was supposed to help with depression. I used cheaper brands and discovered that brands do matter, because the cheaper ones didn’t work. Through my haphazard exploration of natural alternatives, I came off Zoloft completely. During this time, I developed greater empathy for my patients, openness to natural alternatives, appreciation for supplement quality, and learned about psychotropic withdrawal. Most importantly, I came to understand a patient’s need to be free.

Five years later, in 2002, I had a thriving, but conventional, private practice. Instead of being content, however, I once again wanted to quit psychiatry. Medicating patients felt unrewarding, but I didn’t have another approach. Simultaneously, my practice was filling up with chronically ill, heavily medicated, bipolar patients. Their intense suffering combined with my discontent with psychiatry made me desperate for something better. In this ripe setting, the mother of a patient with bipolar disorder casually mentioned a supplement called EMPower by Truehope that lessened bipolar symptoms. Though my withdrawal from Zoloft allowed me to be more open to holistic approaches, I waited 3 months before calling. I used the supplement for the first time to help a heavily medicated bipolar patient in her 30’s, whose Depakote side effects caused her to wear a diaper, lack any emotions, and suffer severe tremors. Once I made this decision to walk down this new path, I never went back. With guidance from the company, I used this supplement to help many patients lower their medications. At the time, I wondered whether EMPower would be the solution for all my patients. The simplicity and ease of one supplement approach for all mental illnesses appealed to my laziness, so I continued down the holistic path.

Hundreds of supplements, glandulars, essential oils, and homeopathic remedies later, I learned that every patient requires their own unique approach. A year into using the supplement, I discovered that, if patients took too much of it, their old symptoms would reappear. Eventually, I moved out of my comfort zone and tried other supplements. Subsequently, the universe orchestrated two people to tell me about the miraculous outcomes from “thought-field therapy,” an energy-medicine technique. I began exploring “energy medicine” through the support and instruction of a holistic psychotherapist, Mark Bottinick, LCSW-C. Soon, I was connecting the dots between emotional freedom technique and immediate positive changes. Energy medicine allowed me to heal problems without using a pill! I felt as if I had arrived at Solla Sollew by the banks of the Beautiful River Wah-Hoo.

As I discovered and attended conferences in holistic medicine, I got certified in integrative medicine and became a Reiki master. Even as a novice in holistic medicine, I began to experience patients crying with joy, rather than sadness. One psychotic patient got better on some supplements and got a new job in just 2 weeks.

On Feb. 17, 2021, I launched a podcast called “The Holistic Psychiatrist,” with interviews of patients, conversations with practitioners, and insights from me. Of the initial interviews, two of the three patients had bipolar disorder, and were able to safely and successfully withdraw from many medications. They are no longer patients and are free to move on with their lives. A patient who smoothly and successfully lowered six psychiatric medications will be sharing her wisdom and healing journey soon. A naturopathic doctor will also be sharing his insights and successes. He once was a suicidal high school student failing his classes, depressed and anxious, and dependent on marijuana. His recovery occurred more than a decade ago in my holistic practice.

These patients are living proof that holistic approaches can be very powerful and effective. They demonstrate that chronicity may reflect inadequate treatment and not a definition of disease. Over the course of this Holistic Mental Health column, I want to share many incredible healing journeys and insights on holistic psychiatry. I hope that you will be open to this new paradigm and begin your own holistic journey.

Dr. Lee is a psychiatrist with a solo private practice in Lehi, Utah. She integrates functional/orthomolecular medicine and mind/body/energy medicine in her work with patients. Contact her at holisticpsychiatrist.com. She has no conflicts of interest.

When I was asked to write a regular “Holistic Mental Health” column, I decided to write about the Herculean forces that must come together to create a holistic psychiatrist – someone who specializes in helping patients off their medications rather than on.

My journey began when I told a training psychiatrist that I wanted to stop being a psychiatrist. It was a year after my daughter was born, and I had started my third year of adult psychiatry residency at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. I was stressed and exhausted from working on inpatient psychiatric wards for 2 years, countless unpleasant nights on call, and additional sleepless nights caring for an infant.