User login

The path to becoming an esophagologist

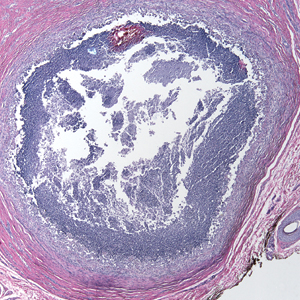

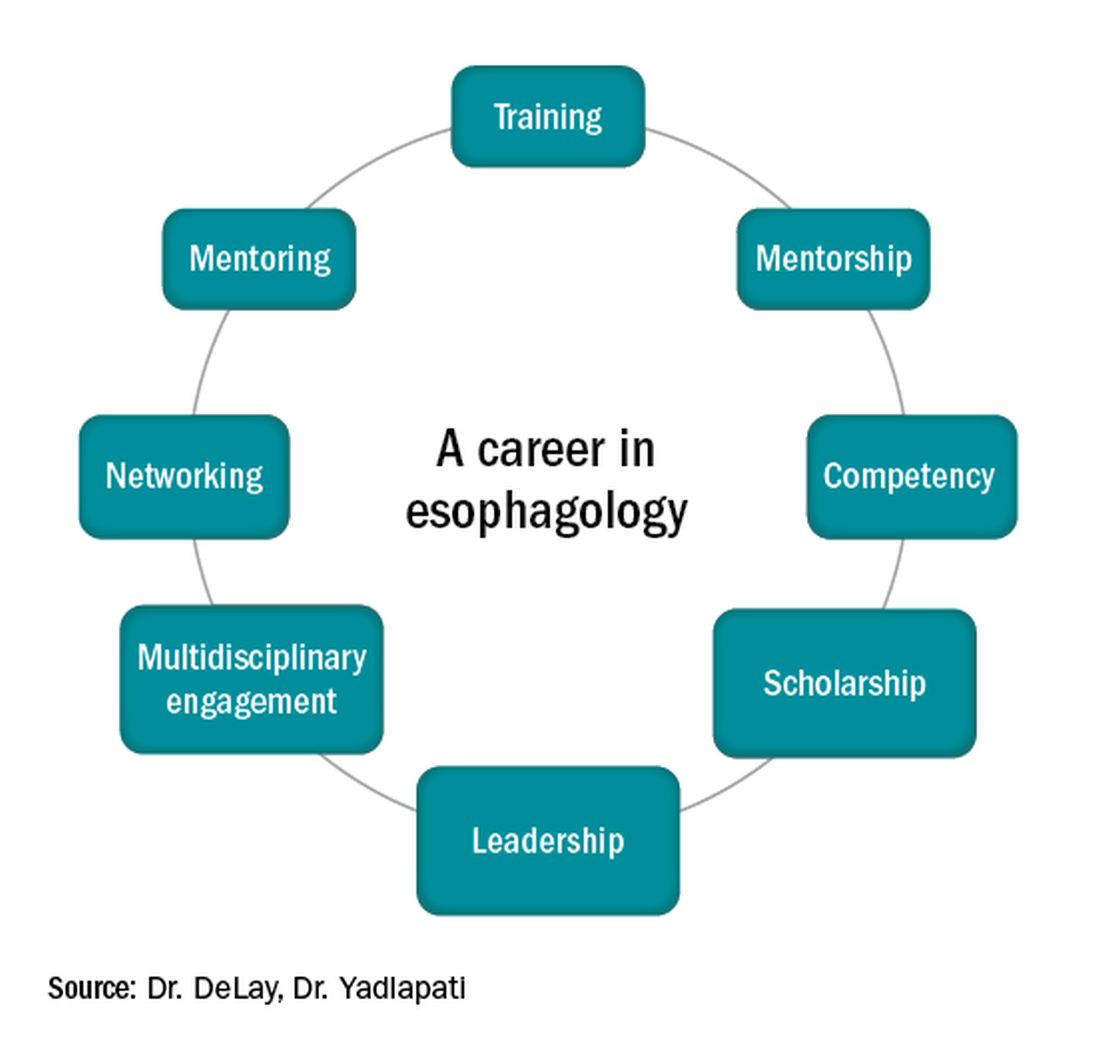

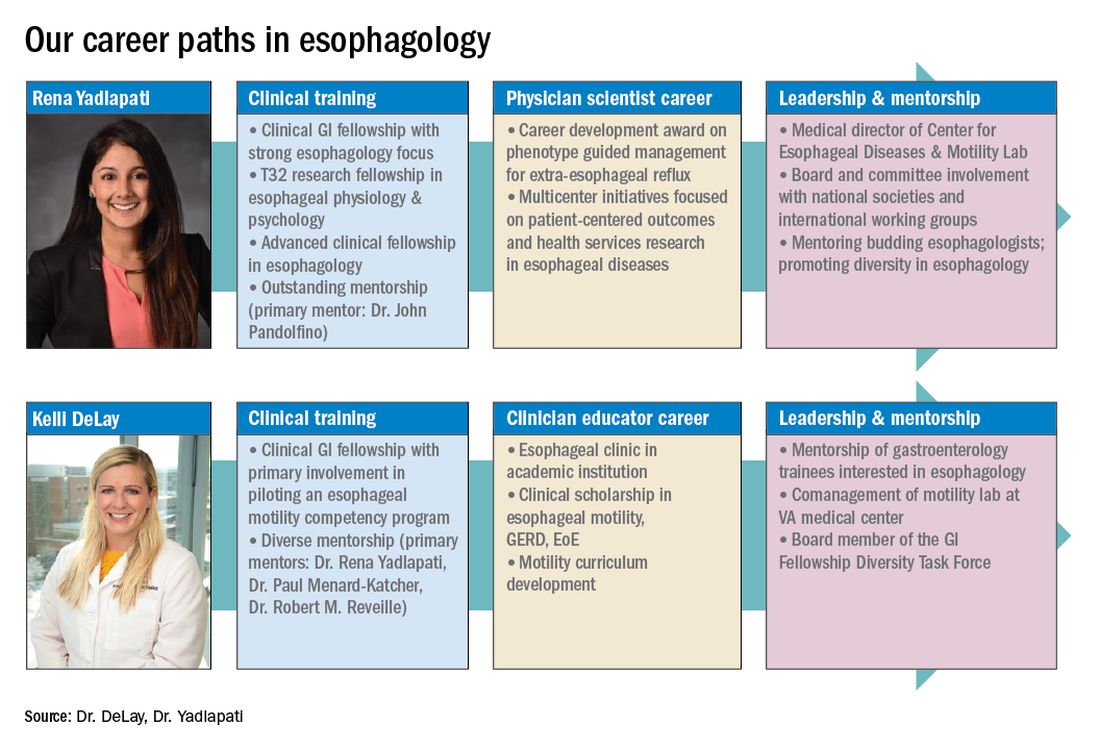

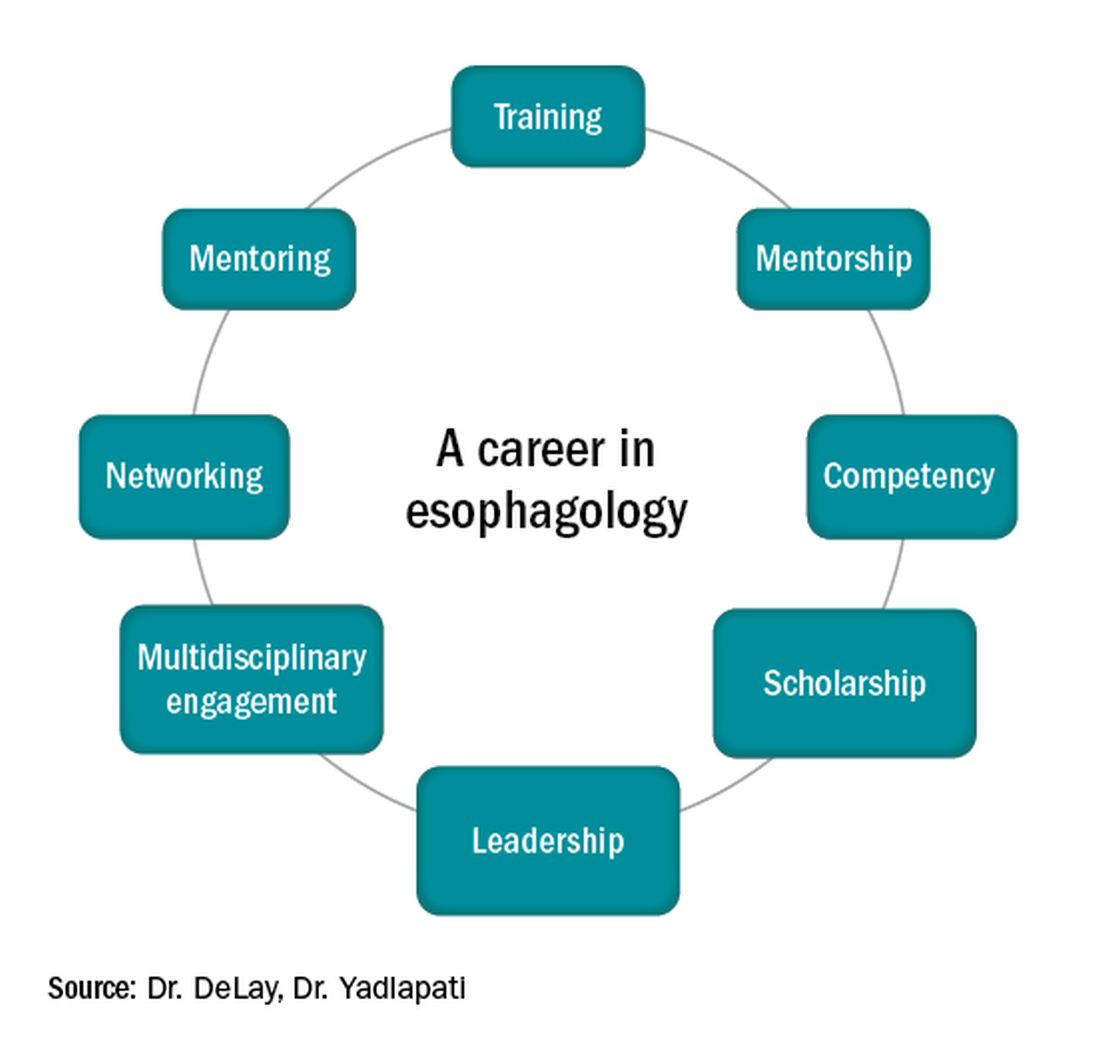

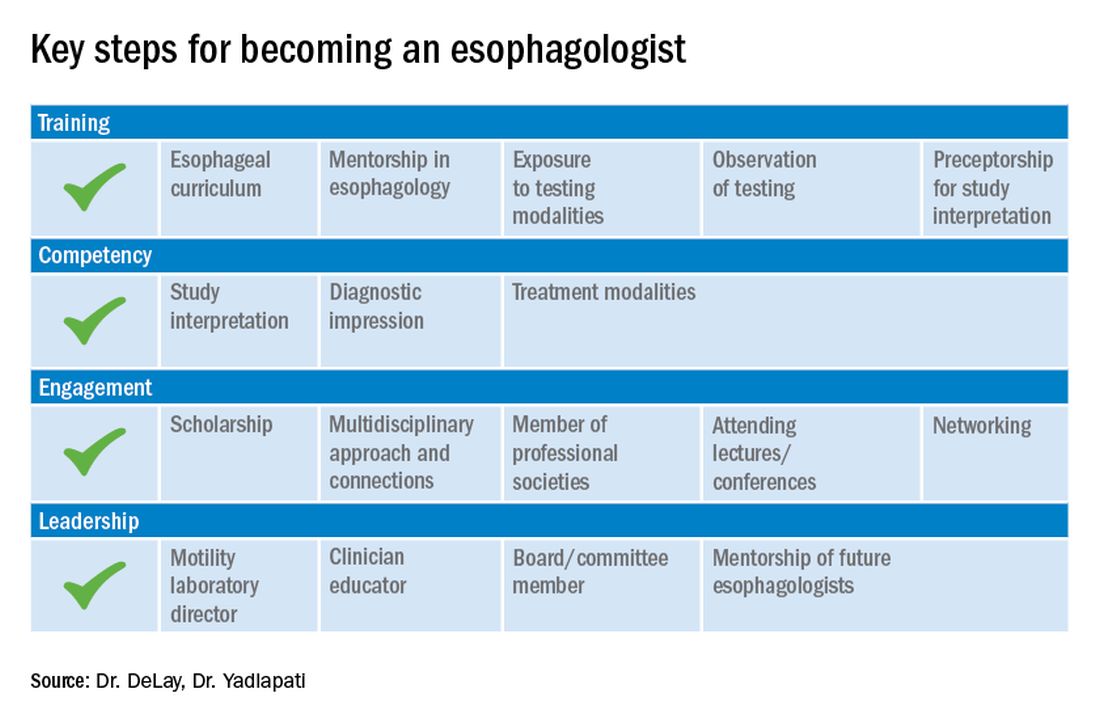

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

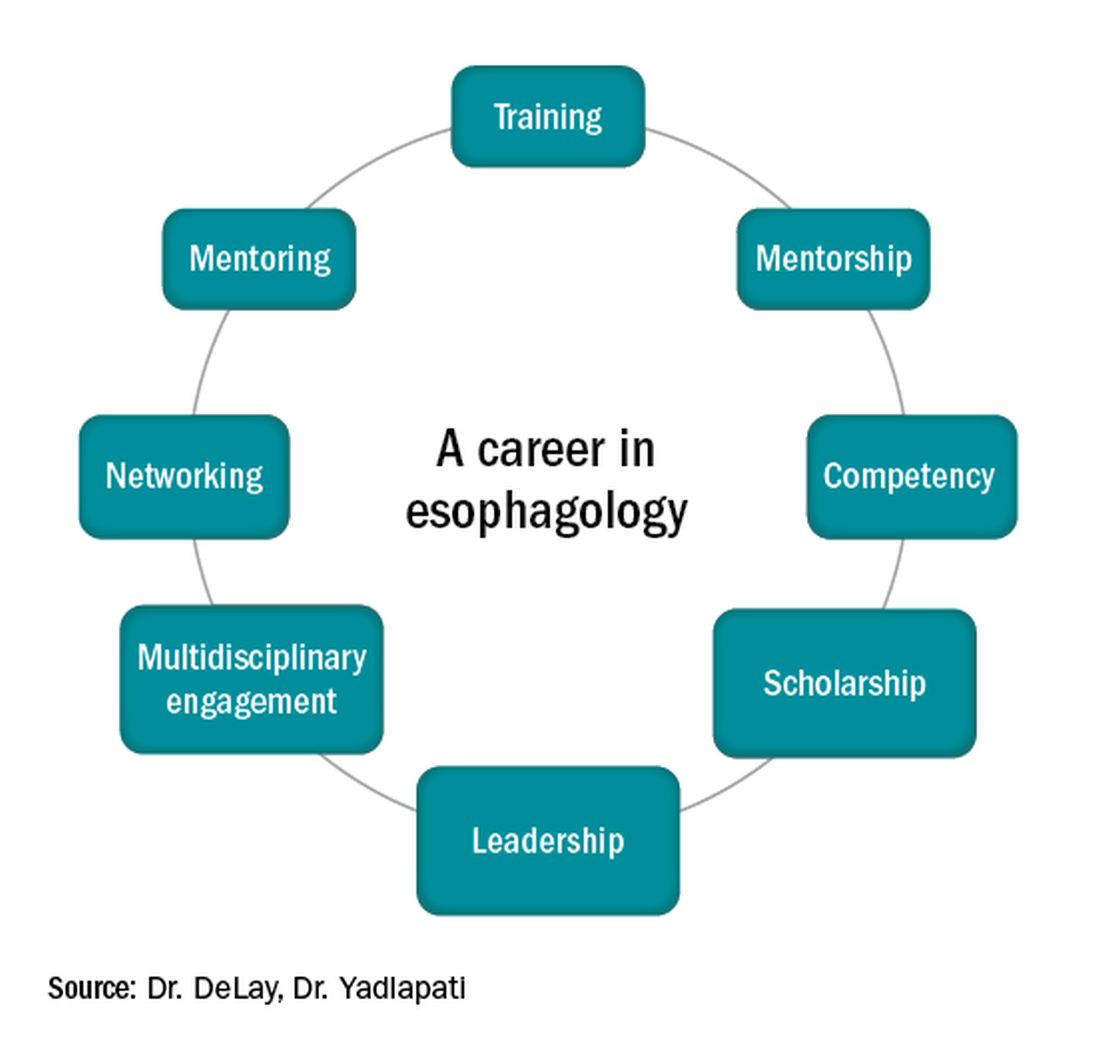

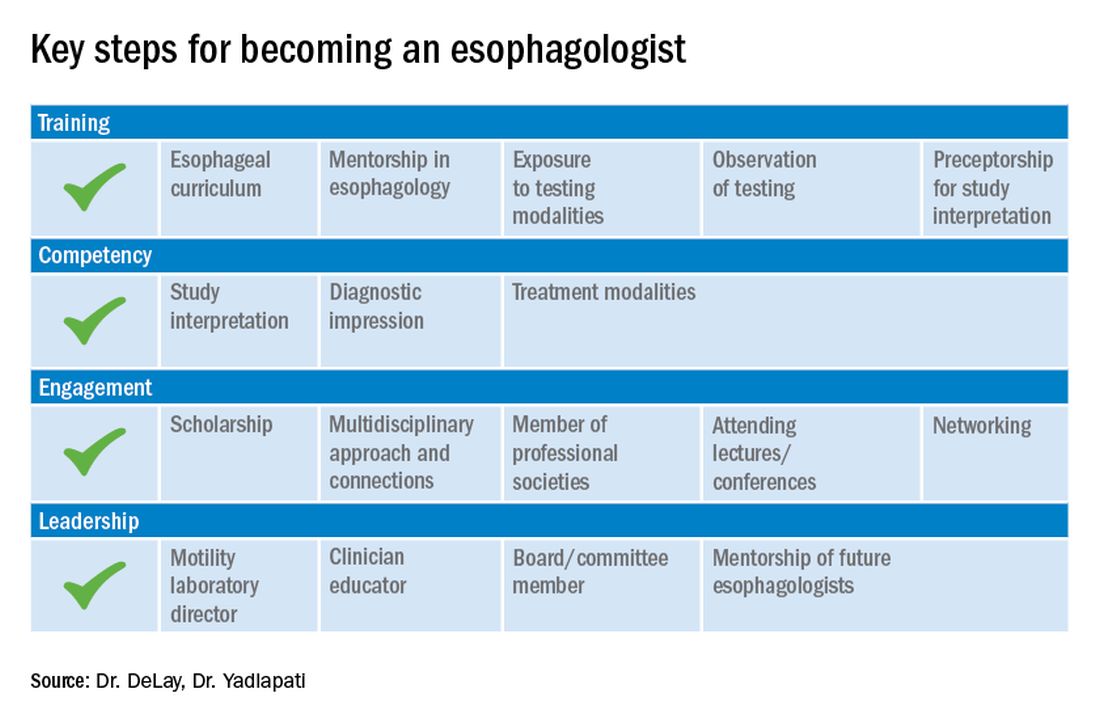

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

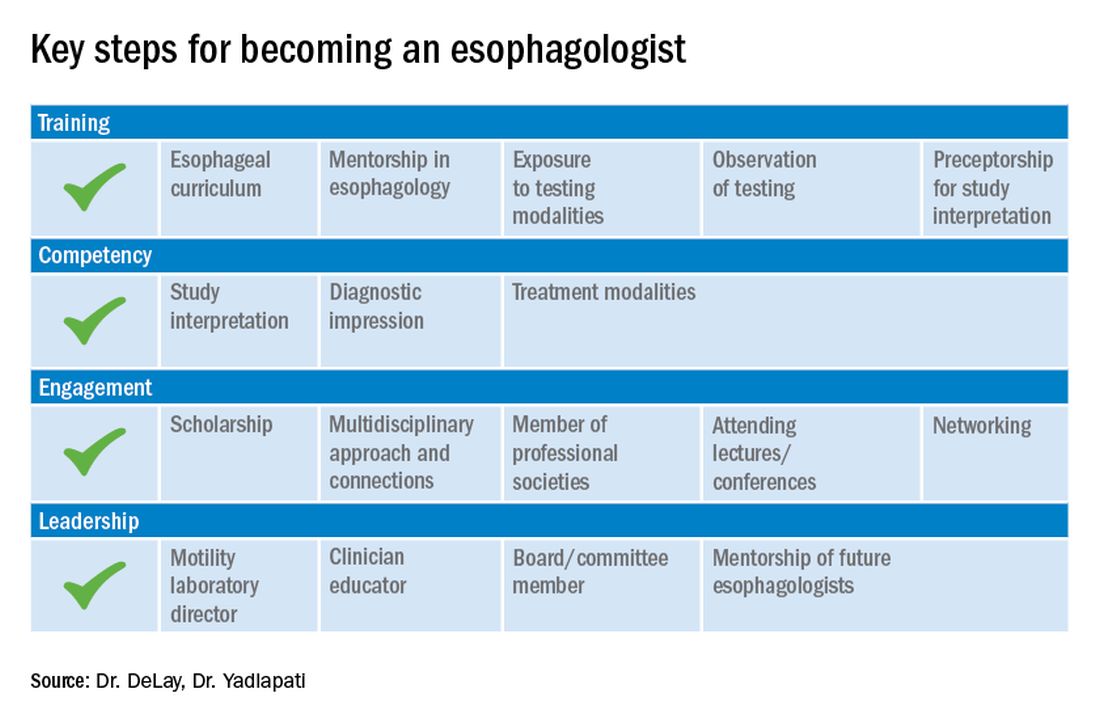

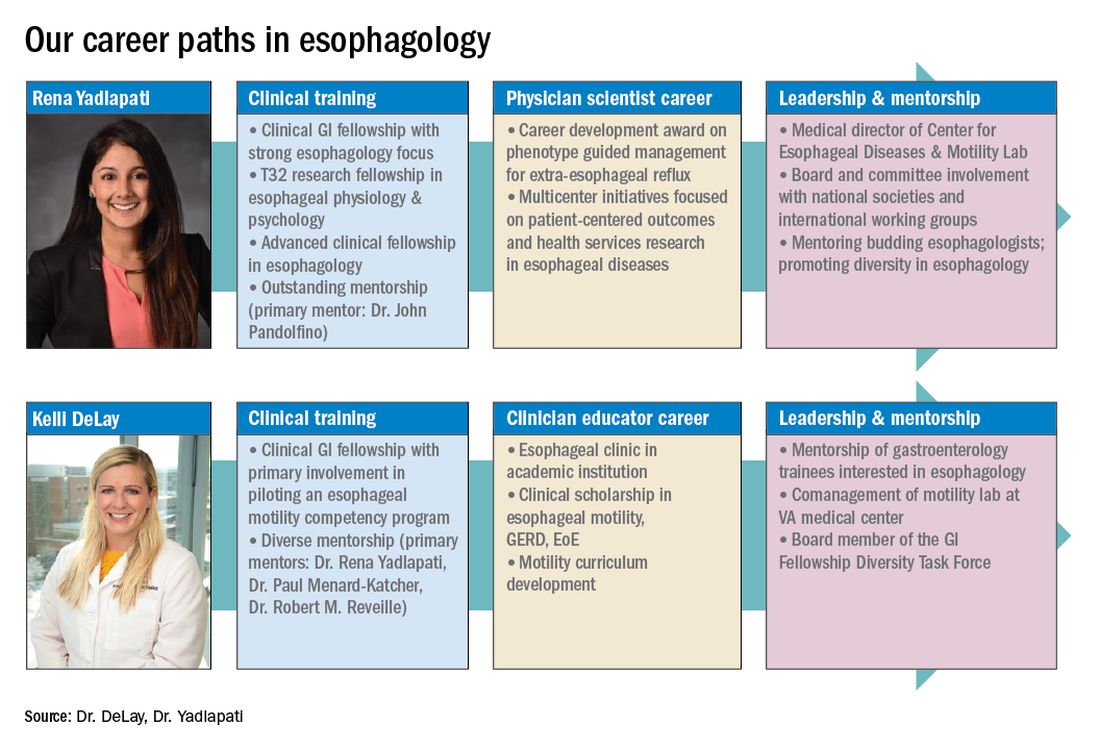

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

Esophagology was a term coined in 1948 to describe a medical specialty devoted to the study of the anatomy, physiology, and pathology of the esophagus. The term was born out of increased interest and evolution in esophagology and supported by development in esophagoscopy.1 While still rooted in these basic tenets, the landscape of esophagology is dramatically different in 2020. The last decade alone has seen unprecedented technological advances in esophagology, from the transformation of line tracings to high-resolution esophageal pressure topography to more recent innovations such as the functional lumen imaging probe. Successful therapeutic developments have increased opportunities for effective and less invasive treatment approaches for achalasia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). With changing concepts in esophageal diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis, successful management now incorporates findings from recent discoveries that have revolutionized care pathways. (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Optimizing esophagology training during fellowship

First, and most importantly, an esophagologist must have a foundation in the basic principles of esophageal anatomy, physiology, and pathology (see Figure 2). While newer digital learning resources exist, tried and true book-based resources – text books, chapters, and reviews – related to esophageal mechanics, the interplay between muscle function and neurogenics, and factors associated with nociception, remain the optimal learning strategy.

Once equipped with a foundation in esophageal physiology, one can readily engage with esophageal technologies, as there exists a vast array of testing to assess esophageal function. A comprehensive understanding of each, including device configuration, clinical protocol, and data storage, promotes a depth of knowledge every esophagologist should develop. Aspiring esophagologists should take time to observe and perform procedures in their motility labs, particularly esophageal high-resolution manometry and ambulatory reflux monitoring studies. If afforded the opportunity through a research study or a clinical indication, esophagologists should also undergo the tests themselves. Empathy regarding the discomfort and tolerability of motility tests, which are notoriously challenging for patients, can promote rapport and trust with patients, increase patient satisfaction, and enhance one’s own understanding of resource utilization and safety.

Perhaps most critical to becoming an esophagologist, is acquiring sufficient competency in interpretation of esophageal studies. Prior research highlights the limitations in achieving competency when trainees adhere to the minimum case volume of studies recommended by the GI core curriculum.2,3 With the bar set higher for the burgeoning esophagologist, one must not only practice with a higher case volume, but also engage in competency-based assessments and performance feedback.4 Trainees should start by reviewing tracings for their own patients. Preliminary interpretation of pending studies and review with a mentor before the final sign-off, participation in research that requires study, or even teaching co-trainees basic tenets of motility are other creative approaches to learning. Esophagologists will be expected to know how to navigate the software to access studies, manually review tracings, and generate reports. Trainees should refer to the multitude of societal guidelines and classification scheme recommendations available when developing competency in diagnostic impression.5

Figure 2

While esophagology is a medical specialty, it is imperative that the esophagologist has a robust understanding of therapeutic options and surgical interventions for esophageal pathology. Scrubbing into the operating room during foregut surgeries is an eye-opening experience. This includes thoracic and abdominal approaches, robotic, laparoscopic, and open techniques, and interventions for GERD, achalasia, diverticular disease, and bariatric management. Equally important is working alongside advanced endoscopy faculty to understand utilities of endoscopic ultrasound, ablative methods for Barrett’s esophagus, and advanced techniques such as peroral endoscopic myotomy and transoral incisionless fundoplication. This exposure is critical as the role of the esophagologist is to speak knowledgably of therapeutic options and the risks and benefits of alternative approaches. Further, the patient’s journey rarely ends with the intervention, and an esophagologist must understand how to evaluate symptoms and manage complications following therapy.

As with broader digestive health, the management of esophageal disorders is becoming increasingly integrated with psychological, lifestyle, and dietary interventions. Observing and understanding how other health care members interact with the patient and relay concepts of brain-gut interaction is helpful in one’s own practice and ability to speak to the value of focused interventions.

These key training aspects in esophagology can be acquired through different avenues (see Figure 3). Formal 1-year advanced esophageal or motility focused fellowships are available at leading esophageal centers. The American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society (ANMS) offers a clinical training program for selected fellows to pursue apprenticeship-based training in gastrointestinal motility. A review of the benefits of additional training, available programs, and how to apply, can be found at The New Gastroenterologist. It may be possible to customize parts of the general clinical fellowship with a strong focus on esophagology. All budding esophagologists are strongly encouraged to attend and participate in subspecialty national meetings such as through the ANMS or the American Foregut Society.

Figure 3

Steep learning curve post fellowship

Regardless of the robust nature of clinical esophagology training, early career esophagologists will face challenges and learn on the job.

Many esophagologists are directors of a motility lab early in their careers. This is often uncharted territory in terms of managing a team of nurses, technicians, and other providers. The director of a motility lab will be called upon to troubleshoot various arenas of diagnostic workup, from study acquisition and interpretation to technical barriers with equipment or software. Keys to maintaining a successful motility lab further include optimizing schedules and protocols, delineating roles and responsibilities of team members, ensuring adequate training across staff and providers, communicating expectations, and cultivating an open relationship with the motility lab supervisor. Crucial, yet often neglected during fellowship training, are the economic considerations of operating and expanding the motility lab, and the financial implications for one’s own practice.6 Participating in professional development workshops can be especially valuable in cultivating leadership skills.

The care an esophagologist provides relies heavily on collaborative relationships within the organization and peer mentorship, cooperation, and feedback. It is essential to cultivate multidisciplinary relationships with surgical (e.g., foregut surgery, laryngology), medical (e.g., pulmonology, allergy), radiology, and pathology colleagues, as well as with integrated health specialists including psychologists, dietitians, and speech language pathologists. It is also important to have open industry partnerships to ensure appropriate technical support and access to advancements.

Often organizations will have only one esophageal specialist within the group. Fortunately, the national and global community of esophagologists is highly collaborative and collegial. All esophagologists should have a network of mentors and colleagues within and outside of their organization to review complex cases, discuss challenges in the workplace, and foster research and innovation. Along these lines, both aspiring and practicing esophagologists should engage with professional societies as opportunities are abundant. Esophageal-focused societies include the ANMS, American Foregut Society, and International Society of Diseases of Esophagus, and the overarching GI societies also have a strong esophageal focus.

The path to becoming an esophagologist does not mirror the structure of the organ itself. Development is neither confined, unidirectional, nor set in length, but gradual, each step thoughtfully built on the last. Esophageal pathology is diverse, complex, and fascinating. With the appropriate training, mentorship, engagement, and leadership, esophagologists have the privilege of making a great impact on the lives of patients we meet, a fulfilling journey worth the time and effort it takes.

Dr. Delay is in the division of gastroenterology & hepatology, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora. Dr. Yadlapati is at the Center for Esophageal Diseases, division of gastroenterology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla. She is a consultant through institutional agreement to Medtronic, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, and Diversatek; she has received research support from Ironwood Pharmaceuticals; and is on the advisory board of Phathom Pharmaceuticals.

References

1. Holinger PH. Arch Otolaryngol. 1948;47:119-26.

2. Yadlapati R et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1708-14.e3.

3. Oversight Working Network et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:16-27.

4. DeLay K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1453-9.

5. Gyawali CP et al. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(9):e13341.

6. Yadlapati R et al. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1202-10.

Photosensitivity diagnosis made simple

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

“When a patient comes in who makes you suspect a photosensitivity, there will be two different presentations,” he said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In some cases, the patient presents with a reaction they believe is sun related, although they don’t have a rash currently, he said. In other cases, “you as a good clinician suspect photosensitivity because the eruption is in a photo distribution,” although the patient may or may not relate it to sun exposure, he added.

Dr. DeLeo noted a few key points to include when taking the history in patients with likely photosensitivity, whether or not they present with a rash.

“I always ask patients when did the episode occur? Is it chronic?” Also ask about timing: Does the reaction occur in the sun, or later? Does it occur quickly and go away within hours, or occur within days or weeks of exposure?

“Always take a good drug history, as photosensitivity can often be related to drugs,” Dr. DeLeo noted. For example, approximately 50% of individuals on amiodarone will have some type of photosensitivity, he said.

Other drug-induced photosensitive conditions include drug-induced subacute cutaneous lupus and pseudoporphyria from NSAIDs, as well as hyperpigmentation from diltiazem, which most often occurs in Black women, he said.

“Photodrug reactions are usually related to UVA radiation, and that is important because you can develop it through the window while driving in your car”: The car windows do not protect against UVA, Dr. DeLeo said. If you have a patient who tells you about a photosensitivity or has a rash and they are on a photosensitizing drug, first rule out connective tissue disease, then discontinue the drug in collaboration with the patient’s internist and wait for the reaction to disappear, and it should, he said.

Some photosensitivity rashes have characteristic patterns, notably connective tissue disease patterns in lupus and dermatomyositis patients, bullous eruptions in cases of porphyria or phototoxic contact dermatitis, and eczematous eruptions, Dr. DeLeo noted.

Patients who present without a rash, but report a history of a reaction that they believe is related to sun exposure, fall into two categories: some had a rash that occurred while in the sun and disappeared quickly, and some had one that occurred hours or days after exposure and lasted a few days to weeks, said Dr. DeLeo.

The differential diagnosis in the patient with immediate photosensitivity is fairly clear: These patients usually have solar urticaria, he said. However, some lupus patients may report this reaction so it is important to rule out connective tissue disease. The diagnosis can be made with phototesting or do a simple test by having the patient sit out in the sunshine, he said.

For the patient who has a delayed reactivity after sun exposure, and doesn’t have the reaction when they come to the office, the differential diagnosis in a simply applied way is that, if the reaction spared the face, it is likely polymorphous light eruption (PMLE); but if the face is involved, the patient likely has photoallergic contact dermatitis, Dr. DeLeo explained. However, always consider the alternatives of connective tissue disease, drug reactions, and contact dermatitis that is not photoallergic, he noted.

PMLE “is the most common photosensitivity reaction that we see in the United States,” and it almost always occurs when people are away from home, usually on vacation, said Dr. DeLeo. The differential diagnosis for patients with recurrent or delayed rash involving the face could be photoallergic contact dermatitis, but rule out airborne contact dermatitis, personal care product contact dermatitis, and chronic actinic dermatitis, he said. A work-up for these patients could include a photo test, photopatch test, or patch test.

Dr. DeLeo disclosed serving as a consultant for Estee Lauder.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Sunscreen myths, controversies continue

, according to Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J.

Although sunscreens are regulated as an OTC drug under the Food and Drug Administration, concerns persist about the safety of sunscreen active ingredients, including avobenzone, oxybenzone, and octocrylene, Dr. Wang said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In 2019, the FDA proposed a rule that requested additional information on sunscreen ingredients. In response, researchers examined six active ingredients used in sunscreen products. The preliminary results were published in JAMA Dermatology in 2019, with a follow-up study published in 2020 . The studies examined the effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration as a sign of absorption of sunscreen active ingredients.

High absorption

Overall, the maximum level of blood concentration went above the 0.5 ng/mL threshold for waiving nonclinical toxicology studies for all six ingredients. However, the studies had several key limitations, Dr. Wang pointed out. “The maximum usage condition applied in these studies was unrealistic,” he said. “Most people when they use a sunscreen don’t reapply and don’t use enough,” he said.

Also, just because an ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream does not mean it is toxic or harmful to humans, he said. Sunscreens have been used for 5 or 6 decades with almost zero reports of systemic toxicity, he observed.

The conclusions from the studies were that the FDA wanted additional research, but “they do not indicate that individuals should refrain from using sunscreen as a way to protect themselves from skin cancer,” Dr. Wang emphasized.

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 to provide financial relief for individuals affected by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “Within that act, there is a provision to reform modernized U.S. regulatory framework on OTC drug reviews,” which will add confusion to the development of a comprehensive monograph about sunscreen because the regulatory process will change, he said.

In the meantime, confusion will likely increase among patients, who may, among other strategies, attempt to make their own sunscreen products at home, as evidenced by videos of individuals making their own products that have had thousands of views, said Dr. Wang. However, these products have no UV protection, he said.

For current sunscreen products, manufacturers are likely to focus on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide products, which fall into the GRASE I category for active ingredients recognized as safe and effective. More research is needed on homosalate, avobenzone, octisalate, and octocrylene, which are currently in the GRASE III category, meaning the data are insufficient to make statements about safety, he said.

Vitamin D concerns

Another sunscreen concern is that use will block healthy vitamin D production, Dr. Wang said. Vitamin D enters the body in two ways, either through food or through the skin, and the latter requires UVB exposure, he explained. “If you started using a sunscreen with SPF 15 that blocks 93% of UVB, you can essentially shut down vitamin D production in the skin,” but that is in the laboratory setting, he said. What happens in reality is different, as people use much less than in a lab setting, and many people put on a small amount of sunscreen and then spend more time in the sun, thereby increasing exposure, Dr. Wang noted.

For example, a study published in 1988 showed that long-term sunscreen users had levels of vitamin D that were less than 50% of those seen in non–sunscreen users. However, another study published in 1995 showed that serum vitamin D levels were not significantly different between users of an SPF 17 sunscreen and a placebo over a 7-month period.

Is a higher SPF better?

Many patients believe that the difference between a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 and 60 is negligible. “People generally say that SPF 30 blocks 96.7% of UVB and SPF 60 blocks 98.3%, but that’s the wrong way of looking at it,” said Dr. Wang. Instead, consider “how much of the UV ray is able to pass through the sunscreen and reach your skin and do damage,” he said. If a product with SPF 30 allows a transmission of 3.3% and a product with SPF 60 allows a transmission of 1.7%, “the SPF 60 product has 194% better protection in preventing the UV reaching the skin,” he said.

Over a lifetime, individuals will build up more UV damage with consistent use of SPF 30, compared with SPF 60 products, so this myth is important to dispel, Dr. Wang emphasized. “It is the transmission we should focus on, not the blockage,” he said.

Also, consider that the inactive ingredients matter in sunscreens, such as water resistance and film-forming technology that helps promote full coverage, Dr. Wang said, but don’t discount features such as texture, aesthetics, smell, and color, all of which impact compliance.

“Sunscreen is very personal, and people do not want to use a product just because of the SPF value, they want to use a product based on how it makes them feel,” he said.

At the end of the day, “the best sunscreen is the one a patient will use regularly and actually enjoy using,” Dr. Wang concluded.

Dr. Wang had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, according to Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J.

Although sunscreens are regulated as an OTC drug under the Food and Drug Administration, concerns persist about the safety of sunscreen active ingredients, including avobenzone, oxybenzone, and octocrylene, Dr. Wang said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In 2019, the FDA proposed a rule that requested additional information on sunscreen ingredients. In response, researchers examined six active ingredients used in sunscreen products. The preliminary results were published in JAMA Dermatology in 2019, with a follow-up study published in 2020 . The studies examined the effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration as a sign of absorption of sunscreen active ingredients.

High absorption

Overall, the maximum level of blood concentration went above the 0.5 ng/mL threshold for waiving nonclinical toxicology studies for all six ingredients. However, the studies had several key limitations, Dr. Wang pointed out. “The maximum usage condition applied in these studies was unrealistic,” he said. “Most people when they use a sunscreen don’t reapply and don’t use enough,” he said.

Also, just because an ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream does not mean it is toxic or harmful to humans, he said. Sunscreens have been used for 5 or 6 decades with almost zero reports of systemic toxicity, he observed.

The conclusions from the studies were that the FDA wanted additional research, but “they do not indicate that individuals should refrain from using sunscreen as a way to protect themselves from skin cancer,” Dr. Wang emphasized.

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 to provide financial relief for individuals affected by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “Within that act, there is a provision to reform modernized U.S. regulatory framework on OTC drug reviews,” which will add confusion to the development of a comprehensive monograph about sunscreen because the regulatory process will change, he said.

In the meantime, confusion will likely increase among patients, who may, among other strategies, attempt to make their own sunscreen products at home, as evidenced by videos of individuals making their own products that have had thousands of views, said Dr. Wang. However, these products have no UV protection, he said.

For current sunscreen products, manufacturers are likely to focus on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide products, which fall into the GRASE I category for active ingredients recognized as safe and effective. More research is needed on homosalate, avobenzone, octisalate, and octocrylene, which are currently in the GRASE III category, meaning the data are insufficient to make statements about safety, he said.

Vitamin D concerns

Another sunscreen concern is that use will block healthy vitamin D production, Dr. Wang said. Vitamin D enters the body in two ways, either through food or through the skin, and the latter requires UVB exposure, he explained. “If you started using a sunscreen with SPF 15 that blocks 93% of UVB, you can essentially shut down vitamin D production in the skin,” but that is in the laboratory setting, he said. What happens in reality is different, as people use much less than in a lab setting, and many people put on a small amount of sunscreen and then spend more time in the sun, thereby increasing exposure, Dr. Wang noted.

For example, a study published in 1988 showed that long-term sunscreen users had levels of vitamin D that were less than 50% of those seen in non–sunscreen users. However, another study published in 1995 showed that serum vitamin D levels were not significantly different between users of an SPF 17 sunscreen and a placebo over a 7-month period.

Is a higher SPF better?

Many patients believe that the difference between a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 and 60 is negligible. “People generally say that SPF 30 blocks 96.7% of UVB and SPF 60 blocks 98.3%, but that’s the wrong way of looking at it,” said Dr. Wang. Instead, consider “how much of the UV ray is able to pass through the sunscreen and reach your skin and do damage,” he said. If a product with SPF 30 allows a transmission of 3.3% and a product with SPF 60 allows a transmission of 1.7%, “the SPF 60 product has 194% better protection in preventing the UV reaching the skin,” he said.

Over a lifetime, individuals will build up more UV damage with consistent use of SPF 30, compared with SPF 60 products, so this myth is important to dispel, Dr. Wang emphasized. “It is the transmission we should focus on, not the blockage,” he said.

Also, consider that the inactive ingredients matter in sunscreens, such as water resistance and film-forming technology that helps promote full coverage, Dr. Wang said, but don’t discount features such as texture, aesthetics, smell, and color, all of which impact compliance.

“Sunscreen is very personal, and people do not want to use a product just because of the SPF value, they want to use a product based on how it makes them feel,” he said.

At the end of the day, “the best sunscreen is the one a patient will use regularly and actually enjoy using,” Dr. Wang concluded.

Dr. Wang had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

, according to Steven Q. Wang, MD, director of dermatologic surgery and dermatology, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, Basking Ridge, N.J.

Although sunscreens are regulated as an OTC drug under the Food and Drug Administration, concerns persist about the safety of sunscreen active ingredients, including avobenzone, oxybenzone, and octocrylene, Dr. Wang said in a virtual presentation at MedscapeLive’s annual Las Vegas Dermatology Seminar.

In 2019, the FDA proposed a rule that requested additional information on sunscreen ingredients. In response, researchers examined six active ingredients used in sunscreen products. The preliminary results were published in JAMA Dermatology in 2019, with a follow-up study published in 2020 . The studies examined the effect of sunscreen application on plasma concentration as a sign of absorption of sunscreen active ingredients.

High absorption

Overall, the maximum level of blood concentration went above the 0.5 ng/mL threshold for waiving nonclinical toxicology studies for all six ingredients. However, the studies had several key limitations, Dr. Wang pointed out. “The maximum usage condition applied in these studies was unrealistic,” he said. “Most people when they use a sunscreen don’t reapply and don’t use enough,” he said.

Also, just because an ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream does not mean it is toxic or harmful to humans, he said. Sunscreens have been used for 5 or 6 decades with almost zero reports of systemic toxicity, he observed.

The conclusions from the studies were that the FDA wanted additional research, but “they do not indicate that individuals should refrain from using sunscreen as a way to protect themselves from skin cancer,” Dr. Wang emphasized.

Congress passed the CARES Act in March 2020 to provide financial relief for individuals affected by the novel coronavirus, COVID-19. “Within that act, there is a provision to reform modernized U.S. regulatory framework on OTC drug reviews,” which will add confusion to the development of a comprehensive monograph about sunscreen because the regulatory process will change, he said.

In the meantime, confusion will likely increase among patients, who may, among other strategies, attempt to make their own sunscreen products at home, as evidenced by videos of individuals making their own products that have had thousands of views, said Dr. Wang. However, these products have no UV protection, he said.

For current sunscreen products, manufacturers are likely to focus on titanium dioxide and zinc oxide products, which fall into the GRASE I category for active ingredients recognized as safe and effective. More research is needed on homosalate, avobenzone, octisalate, and octocrylene, which are currently in the GRASE III category, meaning the data are insufficient to make statements about safety, he said.

Vitamin D concerns

Another sunscreen concern is that use will block healthy vitamin D production, Dr. Wang said. Vitamin D enters the body in two ways, either through food or through the skin, and the latter requires UVB exposure, he explained. “If you started using a sunscreen with SPF 15 that blocks 93% of UVB, you can essentially shut down vitamin D production in the skin,” but that is in the laboratory setting, he said. What happens in reality is different, as people use much less than in a lab setting, and many people put on a small amount of sunscreen and then spend more time in the sun, thereby increasing exposure, Dr. Wang noted.

For example, a study published in 1988 showed that long-term sunscreen users had levels of vitamin D that were less than 50% of those seen in non–sunscreen users. However, another study published in 1995 showed that serum vitamin D levels were not significantly different between users of an SPF 17 sunscreen and a placebo over a 7-month period.

Is a higher SPF better?

Many patients believe that the difference between a sunscreen with an SPF of 30 and 60 is negligible. “People generally say that SPF 30 blocks 96.7% of UVB and SPF 60 blocks 98.3%, but that’s the wrong way of looking at it,” said Dr. Wang. Instead, consider “how much of the UV ray is able to pass through the sunscreen and reach your skin and do damage,” he said. If a product with SPF 30 allows a transmission of 3.3% and a product with SPF 60 allows a transmission of 1.7%, “the SPF 60 product has 194% better protection in preventing the UV reaching the skin,” he said.

Over a lifetime, individuals will build up more UV damage with consistent use of SPF 30, compared with SPF 60 products, so this myth is important to dispel, Dr. Wang emphasized. “It is the transmission we should focus on, not the blockage,” he said.

Also, consider that the inactive ingredients matter in sunscreens, such as water resistance and film-forming technology that helps promote full coverage, Dr. Wang said, but don’t discount features such as texture, aesthetics, smell, and color, all of which impact compliance.

“Sunscreen is very personal, and people do not want to use a product just because of the SPF value, they want to use a product based on how it makes them feel,” he said.

At the end of the day, “the best sunscreen is the one a patient will use regularly and actually enjoy using,” Dr. Wang concluded.

Dr. Wang had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE LAS VEGAS DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Recurrent Cutaneous Exophiala Phaeohyphomycosis in an Immunosuppressed Patient

To the Editor:

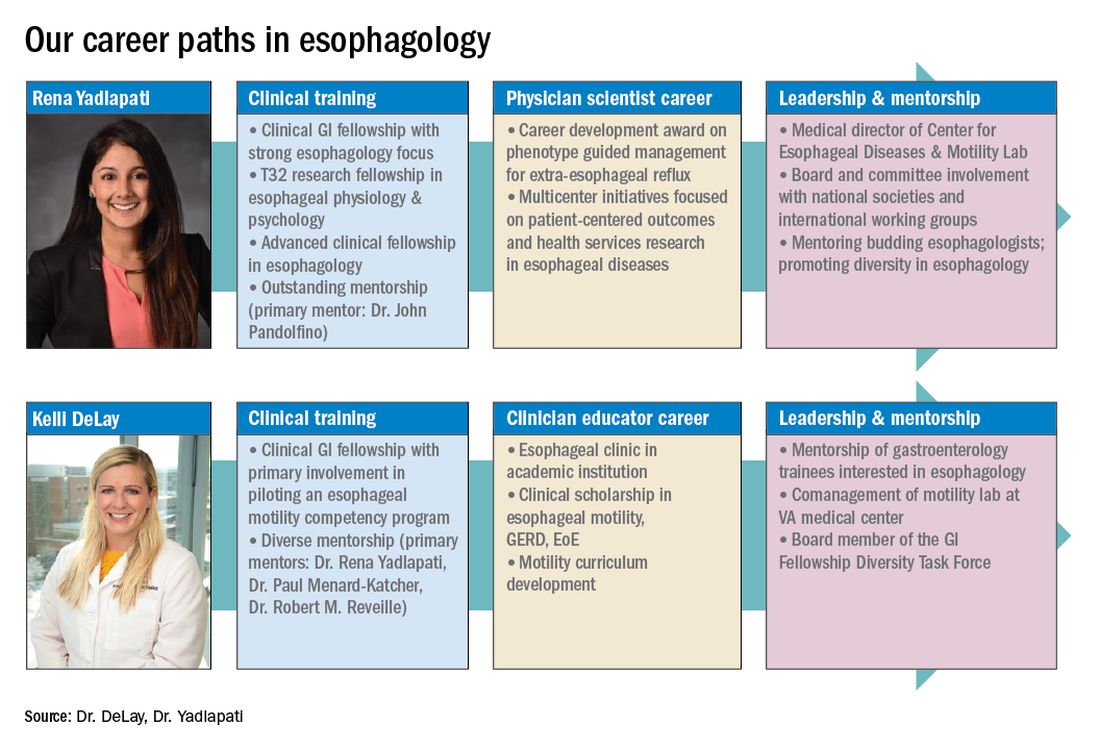

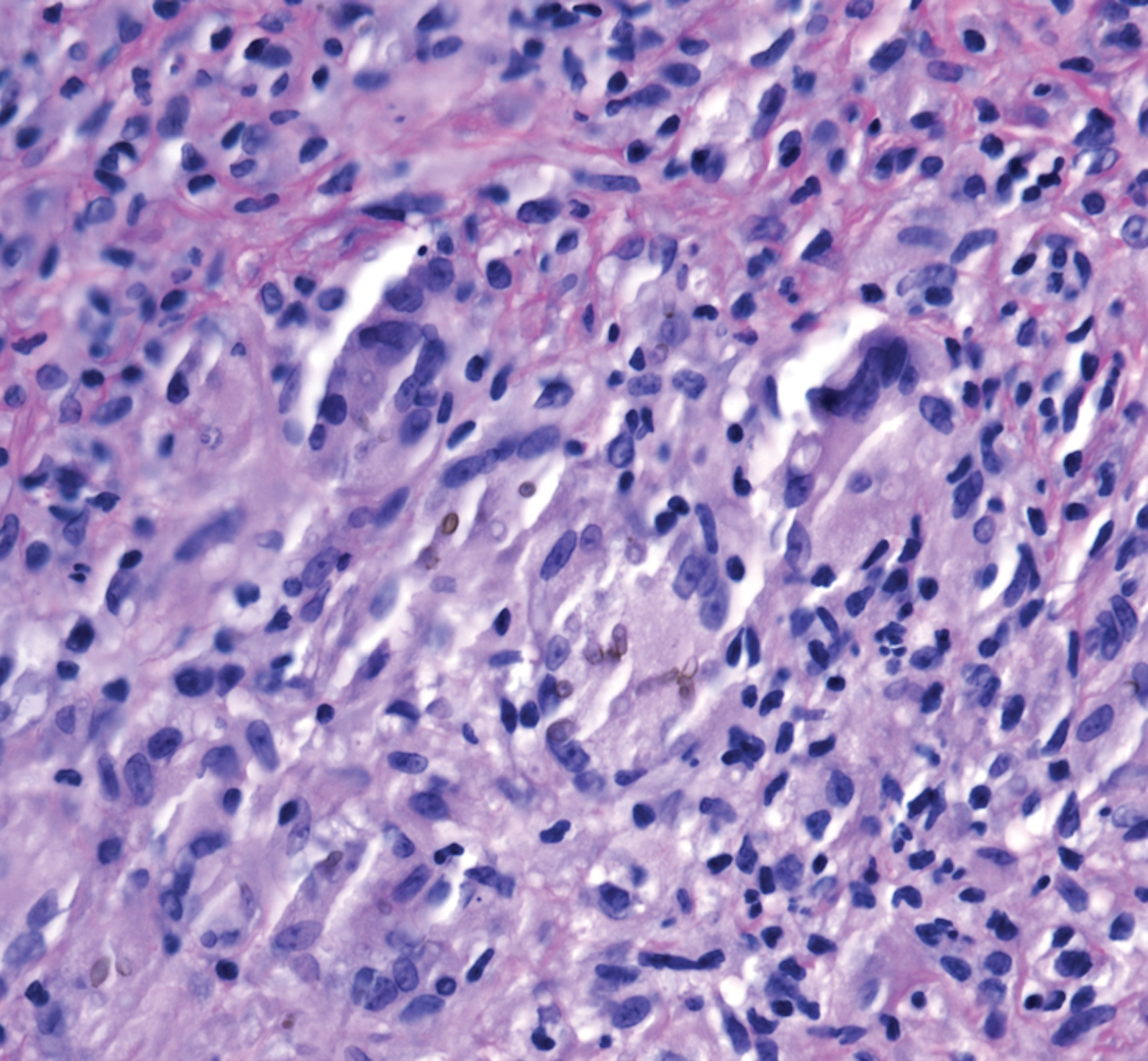

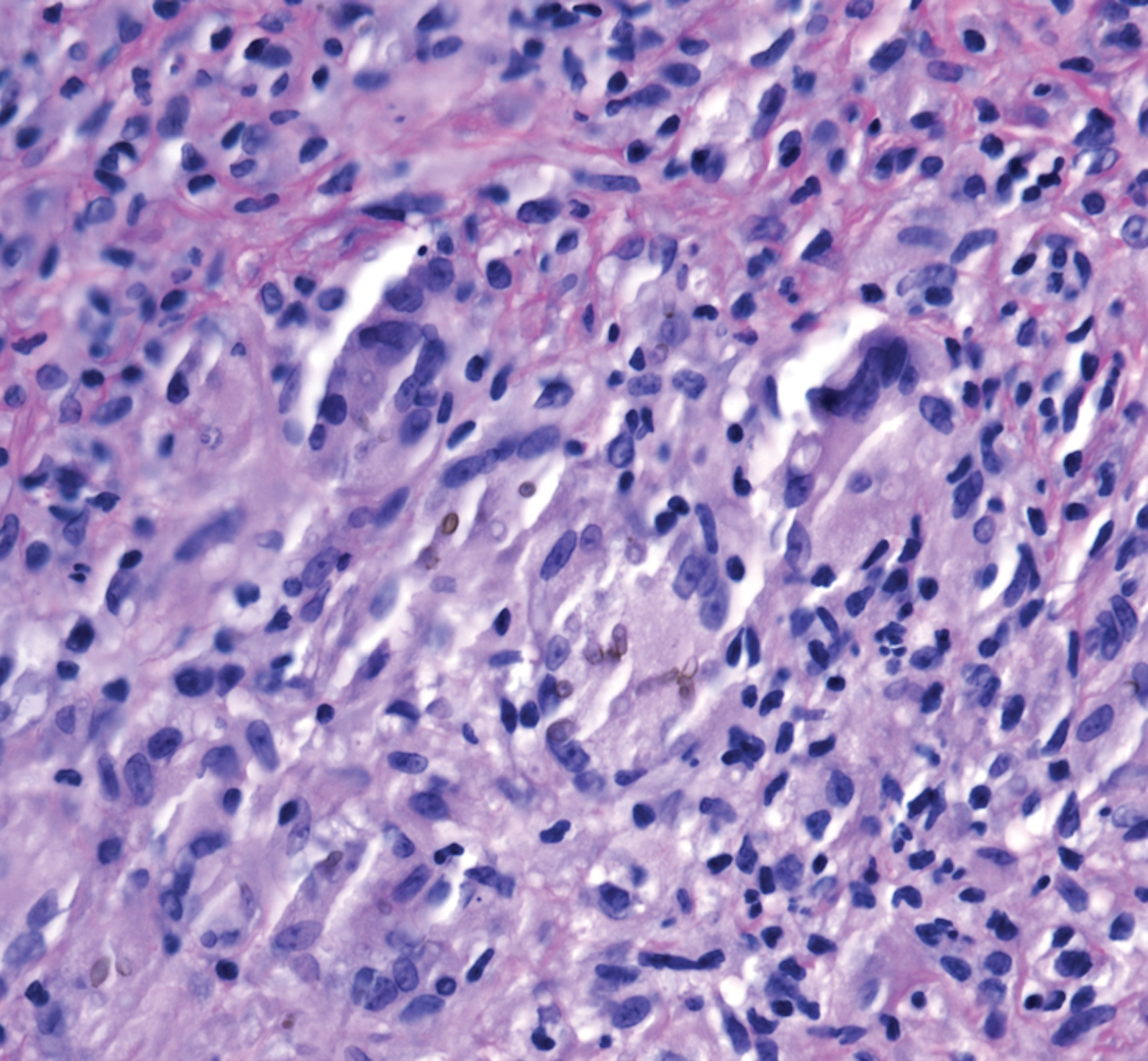

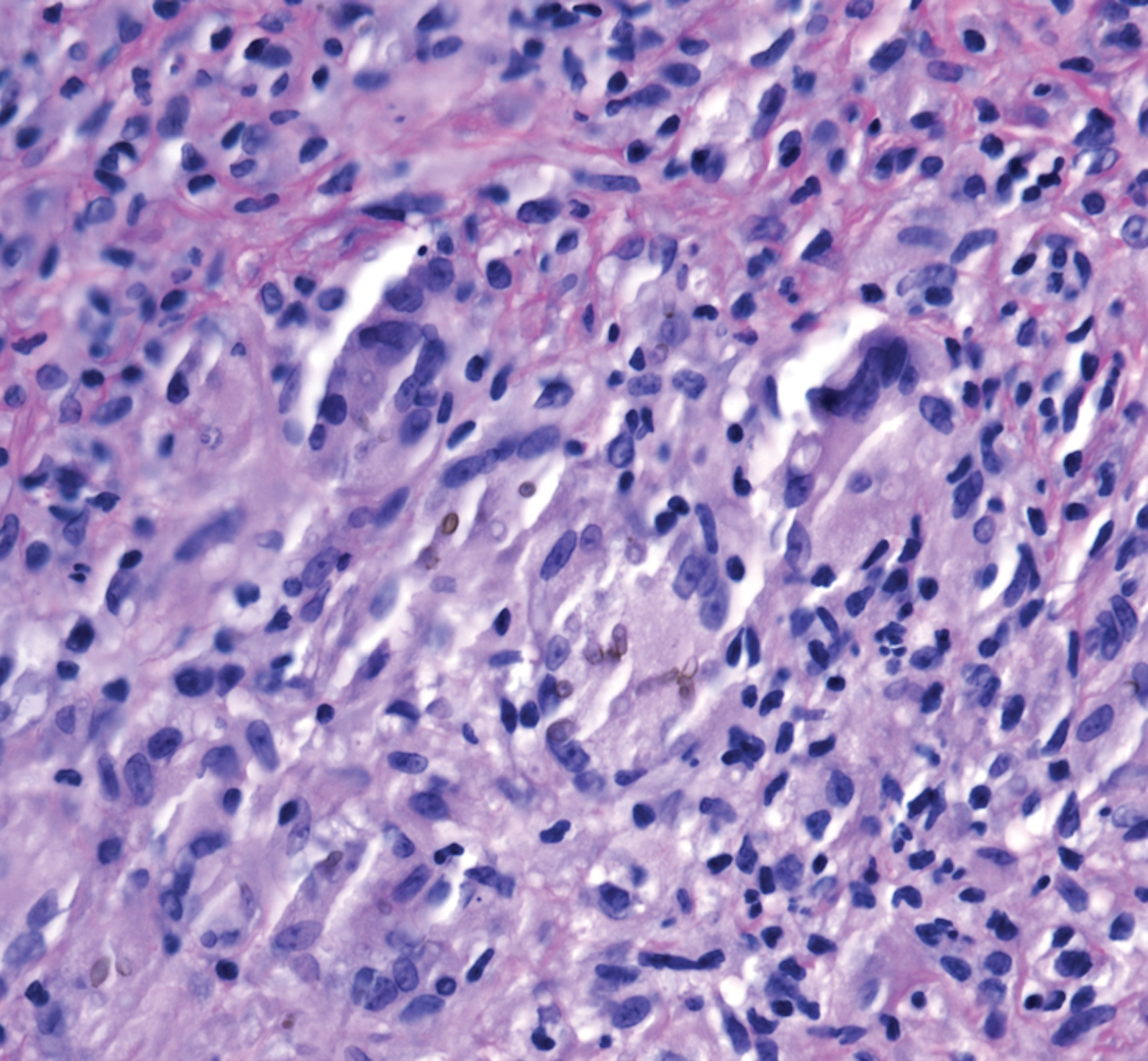

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

To the Editor:

A 73-year-old man presented with a 2.5-cm, recurrent, fluctuant, multiloculated nodule on the left forearm. The lesion was nontender with occasional chalky, white to yellow discharge from multiple sinus tracts. He was otherwise well appearing without signs of systemic infection. He reported similar lesions in slightly different anatomic locations on the left forearm both 7 and 4 years prior to the current presentation. In both instances, the nodules were excised at an outside hospital without any additional treatment. Histopathology of the excised tissue from both prior occasions demonstrated brown septate hyphae surrounded by suppurative and granulomatous inflammation consistent with dematiaceous fungal infection of the dermis (Figures 1 and 2); the organisms were highlighted with periodic acid–Schiff stain.

The patient’s medical history was notable for advanced heart failure with an ejection fraction of 25% and autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. He received an orthotopic kidney transplant 17 years prior to the current presentation. Medications included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone. He denied any trauma or notable exposures to vegetation, and his travel history was unremarkable. A review of systems was negative.

At the current presentation, a sterile fungal culture was performed and found positive for Exophiala species, while bacterial and mycobacterial cultures were negative. A diagnosis of phaeohyphomycosis was made, and he was scheduled for re-excision. Out of concern for interactions with his immunosuppressive regimen, he chose to forgo any systemic antifungal therapy. He died from hospital-acquired pneumonia and volume overload unresponsive to diuretics or dialysis.

Phaeohyphomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by several genera of dematiaceous fungi that are characterized by the presence of melaninlike cell wall pigments thought to locally hinder immune clearance by scavenging phagocyte-derived free radicals. These fungi are ubiquitous in soil and vegetation and usually penetrate the skin at sites of minor trauma.1 Phaeohyphomycosis typically affects immunosuppressed hosts, and its incidence among organ transplant recipients currently is 9%.2 The incidence in this population has been rising, however, as recent advances in immunosuppressive therapies have increased posttransplant survival.3

Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis can present with nodules, cysts, tumors, and/or verrucous plaques, and the diagnosis almost always requires clinicopathologic correlation.3 Rapid diagnosis can be made when septate brown hyphae and/or yeast forms are observed on hematoxylin and eosin stain. Rarely, patients present with disseminated infection, characterized by fungemia; central nervous system involvement; and/or infection of multiple deep structures including the eyes, lungs, bones, and sinuses.4 The risk for dissemination from the skin likely is related to the culprit organism’s genus; Lomentospora, Cladophialophora, and Verruconis often are associated with dissemination, while Alternaria, Exophiala, and Fonsecaea typically remain confined to the skin and subcutis.5 Due to this difference and its potential to impact management, obtaining a tissue fungal culture is advisable when phaeohyphomycosis is suspected.

There is no standard treatment of phaeohyphomycosis. Regimens typically consist of excision and prolonged courses of azole therapy, though excision alone with close follow-up may be a reasonable alternative.6 The latter is a particularly important consideration when managing phaeohyphomycosis in organ transplant recipients, as azoles are known cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibitors that can affect serum levels of common immunosuppressive medications including calcineurin inhibitors and mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors.3 Local recurrence is common regardless of whether azole therapy is pursued,7 and dissemination of localized Exophiala infections is exceedingly rare.8 There is a strong argument to be made for our patient’s decision to forgo antifungal therapy.

This case underscores the difficulty inherent to eradicating local subcutaneous Exophiala phaeohyphomycosis while providing reassurance that with treatment, the risk of life-threatening complications is low. Obtaining tissue for both hematoxylin and eosin stain and sterile culture is crucial to ensuring prompt diagnosis and tailoring the optimal treatment and surveillance strategy to the culprit organism. To avoid delays in diagnosis and treatment, it is important for clinicians to consider phaeohyphomycosis in the differential diagnosis for recurrent nodulocystic lesions in immunosuppressed patients and to recognize that presentations may span many years.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

- Bhardwaj S, Capoor MR, Kolte S, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala jeanselmei: an emerging pathogen in India—case report and review. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:279-284.

- Isa-Isa R, Garcia C, Isa M, et al. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst). Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425-431.

- Tirico MCCP, Neto CF, Cruz LL, et al. Clinical spectrum of phaeohyphomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:465-469.

- Revankar SG, Patterson JE, Sutton DA, et al. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:467-476.

- Revankar SG, Baddley JW, Chen SC-A, et al. A mycoses study group international prospective study of phaeohyphomycosis: an analysis of 99 proven/probable cases. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx200.

- Oberlin KE, Nichols AJ, Rosa R, et al. Phaeohyphomycosis due to Exophiala infections in solid organ transplant recipients: case report and literature review [published online June 26, 2017]. Transpl Infect Dis. 2017;19. doi:10.1111/tid.12723.

- Shirbur S, Telkar S, Goudar B, et al. Recurrent phaeohyphomycosis: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:2015-2016.

- Li D-M, Li R-Y, de Hoog GS, et al. Fatal Exophiala infections in China, with a report of seven cases. Mycoses. 2011;54:E136-E142.

Practice Points

- Phaeohyphomycosis is an infection with dematiaceous fungi that most commonly affects immunosuppressed patients.

- Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis may present with nodulocystic lesions that recur over the course of years.

- Tissue fungal culture should be obtained when the diagnosis is suspected, as the risk for dissemination is related to the culprit organism.

- Surgical excision with close follow-up may be an appropriate management strategy for patients on immunosuppressive medications to avoid interactions with azole therapy.

Scalp Arteriovenous Fistula With Intracranial Communication

To the Editor:

A 71-year-old man presented with a nodule on the vertex of the scalp of 1 year’s duration. The lesion had become soft and tender during the week prior to presentation. He noted that he was experiencing headaches and a buzzing sound in his head. He denied all other neurologic symptoms. The patient was given amoxicillin from a primary care physician and was referred to our institution for evaluation of a presumed inflamed cyst.

The patient’s medical history included an intracranial arteriovenous fistula (AVF) treated with endovascular embolization 1 year prior to presentation, 2 substantial falls in childhood with head trauma and loss of consciousness, essential hypertension, and an aortic aneurysm. His medications included amlodipine, lisinopril, amoxicillin, a multivitamin, and grape seed extract.

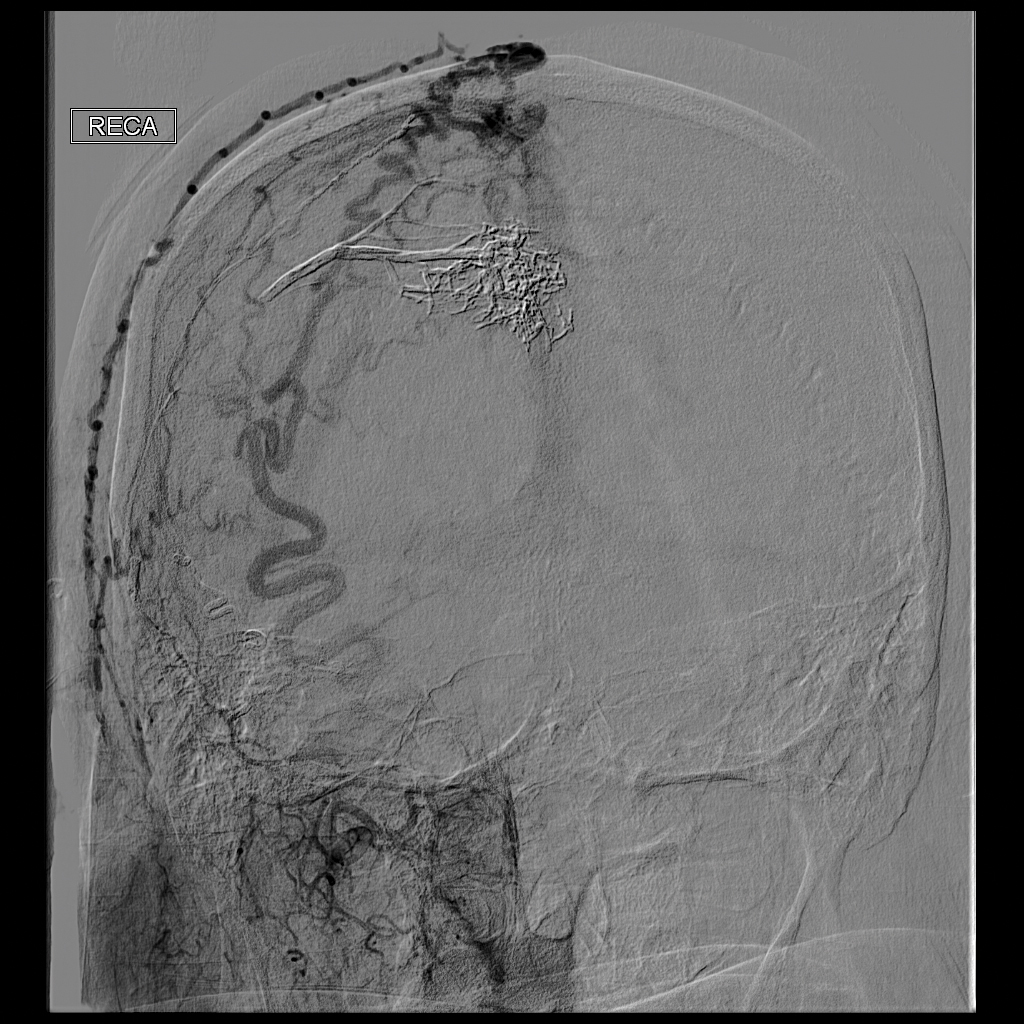

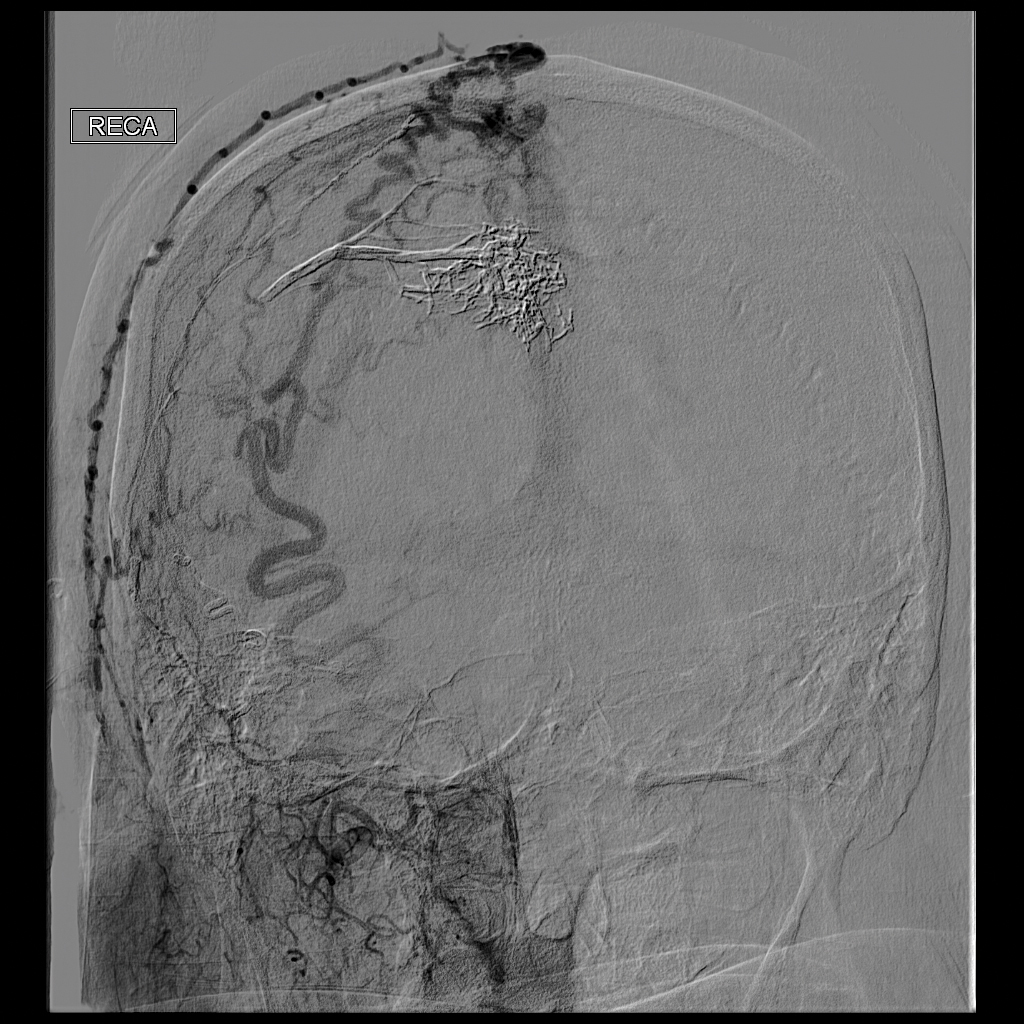

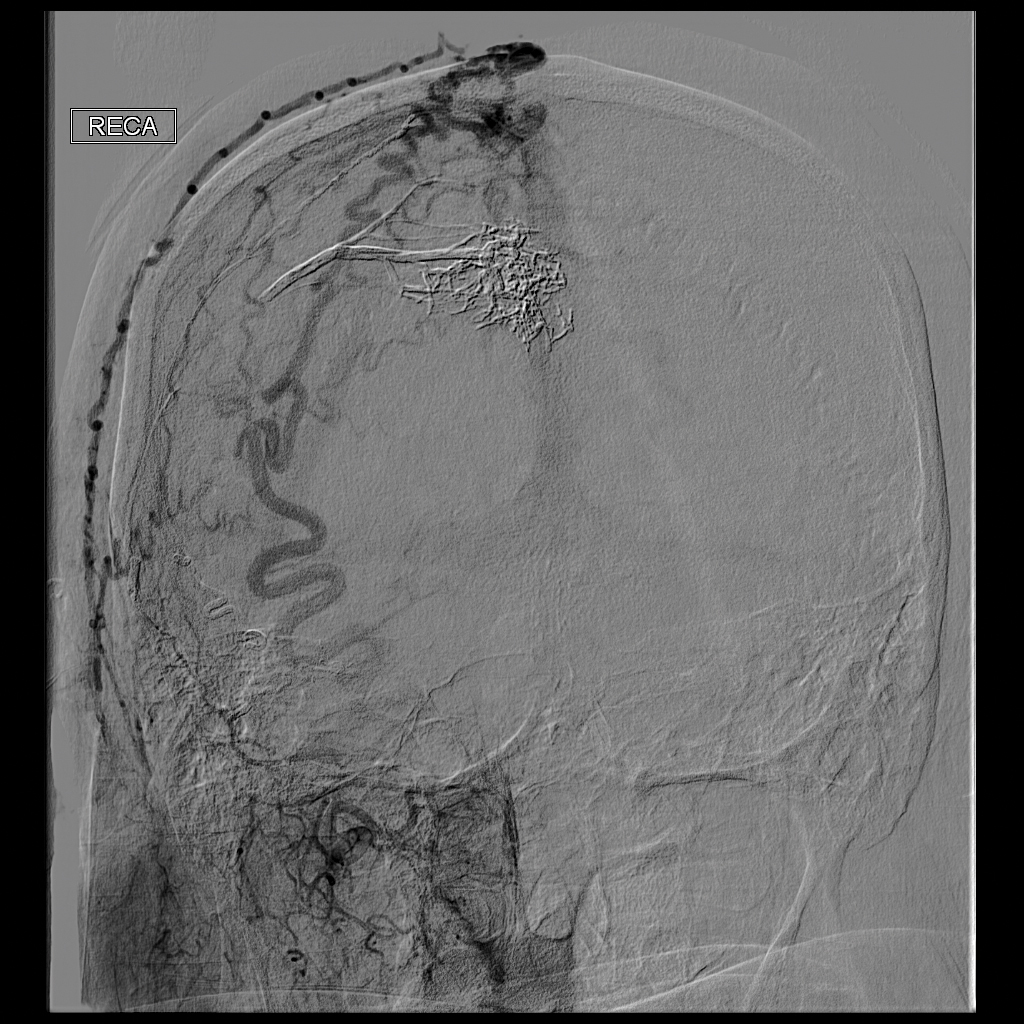

Physical examination revealed a 2-cm, pink, somewhat rubbery, subcutaneous, nonmobile nodule on the vertex of the scalp (Figure 1). The lesion was not consistent with a common pilar cyst, and an excisional biopsy was performed to exclude malignancy. Upon superficial incision, the lesion bled moderately, and the procedure was immediately discontinued. Hemostasis was obtained, and the patient was sent for ultrasonography of the lesion.

Ultrasonography demonstrated a small hypoechoic nodule measuring up to 0.5 cm containing a tangle of vessels in the subcutaneous soft tissue corresponding to the palpable abnormality. A cerebral angiogram demonstrated a dural AVF of the superior sagittal sinus with multifocal supply that connected with this scalp nodule (Figure 2). The patient was treated by interventional neuroradiology with endovascular embolization, which resulted in complete resolution of the scalp nodule.