User login

MicroRNAs May Predict Pancreatic Cancer Risk Years Before Diagnosis

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Early detection of pancreatic cancer could improve patient prognosis, but clinically viable biomarkers are lacking. In a two-stage study, researchers screened and validated circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for early detection using prediagnostic plasma samples from 462 case-control pairs across multiple cohorts.

- The discovery stage included 185 pairs from the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial, and the replication stage included 277 pairs from Shanghai Women’s/Men’s Health Study, Southern Community Cohort Study, and Multiethnic Cohort Study.

- Overall, 798 plasma microRNAs were measured using the NanoString nCounter Analysis System, and odds ratios (ORs) for pancreatic cancer risk were calculated on the basis of miRNA concentrations.

- Statistical analysis involved conditional logistic regression, stratified by age and time from sample collection to diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the discovery stage, the researchers identified 120 miRNAs significantly associated with pancreatic cancer risk.

- Three of these miRNAs showed consistent significant associations in the replication stage. Specifically, hsa-miR-199a-3p/hsa-miR-199b-3p and hsa-miR-191-5p were associated with a 10%-11% lower risk for pancreatic cancer (OR, 0.89 and 0.90, respectively), and hsa-miR-767-5p was associated with an 8% higher risk for pancreatic cancer (OR, 1.08) within 5 years of the blood draw.

- In age-stratified analyses, hsa-miR-767-5p (OR, 1.23) along with four other miRNAs — hsa-miR-640 (OR, 1.33), hsa-miR-874-5p (OR, 1.25), hsa-miR-1299 (OR, 1.28), and hsa-miR-449b-5p (OR, 1.22) — were associated with an increased risk for pancreatic cancer among patients diagnosed at age 65 or older.

- One miRNA, hsa-miR-22-3p (OR, 0.76), was associated with a lower risk for pancreatic cancer in this older age group.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings provide evidence that miRNAs “have a potential utilization in clinical practice” to help “identify high-risk individuals who could subsequently undergo a more definitive but invasive diagnostic procedure,” the authors said. “Such a multistep strategy for pancreatic cancer screening and early detection, likely cost-efficient and low-risk, could be critical to improve survival.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Cong Wang, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers lacked miRNA profiles of patients with pancreatic cancer at diagnosis and were not able to track the miRNA changes among pancreatic cancer cases at the time of clinical diagnosis. Sample collection protocols differed across study cohorts, and the researchers changed assay panels during the study.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Early detection of pancreatic cancer could improve patient prognosis, but clinically viable biomarkers are lacking. In a two-stage study, researchers screened and validated circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for early detection using prediagnostic plasma samples from 462 case-control pairs across multiple cohorts.

- The discovery stage included 185 pairs from the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial, and the replication stage included 277 pairs from Shanghai Women’s/Men’s Health Study, Southern Community Cohort Study, and Multiethnic Cohort Study.

- Overall, 798 plasma microRNAs were measured using the NanoString nCounter Analysis System, and odds ratios (ORs) for pancreatic cancer risk were calculated on the basis of miRNA concentrations.

- Statistical analysis involved conditional logistic regression, stratified by age and time from sample collection to diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the discovery stage, the researchers identified 120 miRNAs significantly associated with pancreatic cancer risk.

- Three of these miRNAs showed consistent significant associations in the replication stage. Specifically, hsa-miR-199a-3p/hsa-miR-199b-3p and hsa-miR-191-5p were associated with a 10%-11% lower risk for pancreatic cancer (OR, 0.89 and 0.90, respectively), and hsa-miR-767-5p was associated with an 8% higher risk for pancreatic cancer (OR, 1.08) within 5 years of the blood draw.

- In age-stratified analyses, hsa-miR-767-5p (OR, 1.23) along with four other miRNAs — hsa-miR-640 (OR, 1.33), hsa-miR-874-5p (OR, 1.25), hsa-miR-1299 (OR, 1.28), and hsa-miR-449b-5p (OR, 1.22) — were associated with an increased risk for pancreatic cancer among patients diagnosed at age 65 or older.

- One miRNA, hsa-miR-22-3p (OR, 0.76), was associated with a lower risk for pancreatic cancer in this older age group.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings provide evidence that miRNAs “have a potential utilization in clinical practice” to help “identify high-risk individuals who could subsequently undergo a more definitive but invasive diagnostic procedure,” the authors said. “Such a multistep strategy for pancreatic cancer screening and early detection, likely cost-efficient and low-risk, could be critical to improve survival.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Cong Wang, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers lacked miRNA profiles of patients with pancreatic cancer at diagnosis and were not able to track the miRNA changes among pancreatic cancer cases at the time of clinical diagnosis. Sample collection protocols differed across study cohorts, and the researchers changed assay panels during the study.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Early detection of pancreatic cancer could improve patient prognosis, but clinically viable biomarkers are lacking. In a two-stage study, researchers screened and validated circulating miRNAs as biomarkers for early detection using prediagnostic plasma samples from 462 case-control pairs across multiple cohorts.

- The discovery stage included 185 pairs from the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial, and the replication stage included 277 pairs from Shanghai Women’s/Men’s Health Study, Southern Community Cohort Study, and Multiethnic Cohort Study.

- Overall, 798 plasma microRNAs were measured using the NanoString nCounter Analysis System, and odds ratios (ORs) for pancreatic cancer risk were calculated on the basis of miRNA concentrations.

- Statistical analysis involved conditional logistic regression, stratified by age and time from sample collection to diagnosis.

TAKEAWAY:

- In the discovery stage, the researchers identified 120 miRNAs significantly associated with pancreatic cancer risk.

- Three of these miRNAs showed consistent significant associations in the replication stage. Specifically, hsa-miR-199a-3p/hsa-miR-199b-3p and hsa-miR-191-5p were associated with a 10%-11% lower risk for pancreatic cancer (OR, 0.89 and 0.90, respectively), and hsa-miR-767-5p was associated with an 8% higher risk for pancreatic cancer (OR, 1.08) within 5 years of the blood draw.

- In age-stratified analyses, hsa-miR-767-5p (OR, 1.23) along with four other miRNAs — hsa-miR-640 (OR, 1.33), hsa-miR-874-5p (OR, 1.25), hsa-miR-1299 (OR, 1.28), and hsa-miR-449b-5p (OR, 1.22) — were associated with an increased risk for pancreatic cancer among patients diagnosed at age 65 or older.

- One miRNA, hsa-miR-22-3p (OR, 0.76), was associated with a lower risk for pancreatic cancer in this older age group.

IN PRACTICE:

The findings provide evidence that miRNAs “have a potential utilization in clinical practice” to help “identify high-risk individuals who could subsequently undergo a more definitive but invasive diagnostic procedure,” the authors said. “Such a multistep strategy for pancreatic cancer screening and early detection, likely cost-efficient and low-risk, could be critical to improve survival.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Cong Wang, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tennessee, was published online in the International Journal of Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The researchers lacked miRNA profiles of patients with pancreatic cancer at diagnosis and were not able to track the miRNA changes among pancreatic cancer cases at the time of clinical diagnosis. Sample collection protocols differed across study cohorts, and the researchers changed assay panels during the study.

DISCLOSURES:

The research was funded by grants from the National Cancer Institute. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

‘Bread and Butter’: Societies Issue T2D Management Guidance

Two professional societies have issued new guidance for type 2 diabetes management in primary care, with one focused specifically on the use of the newer medications.

On April 19, 2024, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published Newer Pharmacologic Treatments in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians. The internal medicine group recommends the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, and sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as second-line treatment after metformin. They also advise against the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

The document was also presented simultaneously at the ACP annual meeting.

And on April 15, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) posted its comprehensive Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024 Abridged for Primary Care Professionals as a follow-up to the December 2023 publication of its full-length Standards. Section 9, Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment, covers the same ground as the ACP guidelines.

General Agreement but Some Differences

The recommendations generally agree regarding medication use, although there are some differences. Both societies continue to endorse metformin and lifestyle modification as first-line therapy for glycemic management in type 2 diabetes. However, while ADA also gives the option of initial combination therapy with prioritization of avoiding hypoglycemia, ACP advises adding new medications only if glycemic goals aren’t met with lifestyle and metformin alone.

The new ACP document gives two general recommendations:

1. Add an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 agonist to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control.

*Use an SGLT2 inhibitor to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, progression of chronic kidney disease, and hospitalization due to congestive heart failure.

*Use a GLP-1 agonist to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and stroke.

2. ACP recommends against adding a DPP-4 inhibitor to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control to reduce morbidity and all-cause mortality.

Both ADA and ACP advise using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with congestive heart failure and/or chronic kidney disease, and using GLP-1 agonists in patients for whom weight management is a priority. The ADA also advises using agents of either drug class with proven cardiovascular benefit for people with type 2 diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease or who are at high risk.

ADA doesn’t advise against the use of DPP-4 inhibitors but doesn’t prioritize them either. Both insulin and sulfonylureas remain options for both, but they also are lower priority due to their potential for causing hypoglycemia. ACP says that sulfonylureas and long-acting insulin are “inferior to SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists in reducing all-cause mortality and morbidity but may still have some limited value for glycemic control.”

The two groups continue to differ regarding A1c goals, although both recommend individualization. The ACP generally advises levels between 7% and 8% for most adults with type 2 diabetes, and de-intensification of pharmacologic agents for those with A1c levels below 6.5%. On the other hand, ADA recommends A1c levels < 7% as long as that can be achieved safely.

This is the first time ACP has addressed this topic in a guideline, panel chair Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, told this news organization. “Diabetes treatment, of course, is our bread and butter…but what we had done before was based on the need to identify a target, like glycosylated hemoglobin. What patients and physicians really want to know now is, who should receive these new drugs? Should they receive these new drugs? And what benefits do they have?”

Added Dr. Crandall, who is professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “At ACP we have a complicated process that I’m actually very proud of, where we’ve asked a lay public panel, as well at the members of our guideline committee, to rank what’s most important in terms of the health outcomes for this condition…And then we look at how to balance those risks and benefits to make the recommendations.”

In the same Annals of Internal Medicine issue are two systematic reviews/meta-analyses that informed the new document, one on drug effectiveness and the other on cost-effectiveness.

In the accompanying editorial from Fatima Z. Syed, MD, an internist and medical weight management specialist at Duke University Division of General Internal Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, she notes, “the potential added benefits of these newer medications, including weight loss and cardiovascular and renal benefits, motivate their prescription, but cost and prior authorization hurdles can bar their use.”

Dr. Syed cites as “missing” from the ACP guidelines an analysis of comorbidities, including obesity. The reason for that, according to the document, is that “weight loss, as measured by percentage of participants who achieved at least 10% total body weight loss, was a prioritized outcome, but data were insufficient for network meta-analysis.”

However, Dr. Syed notes that factoring in weight loss could improve the cost-effectiveness of the newer medications. She points out that the ADA Standards suggest a GLP-1 agonist with or without metformin as initial therapy options for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes who might benefit from weight loss.

“The ACP guidelines strengthen the case for metformin as first-line medication for diabetes when comorbid conditions are not present. Metformin is cost-effective and has excellent hemoglobin A1c reduction. The accompanying economic analysis tells us that in the absence of comorbidity, the newer medication classes do not seem to be cost-effective. However, given that many patients with type 2 diabetes have obesity or existing cardiovascular or renal disease, the choice and accessibility of newer medications can be nuanced. The cost-effectiveness of GLP1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors as initial diabetes therapy in the setting of various comorbid conditions warrants careful exploration.”

Dr. Crandall has no disclosures. Dr. Syed disclosed that her husband is employed by Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two professional societies have issued new guidance for type 2 diabetes management in primary care, with one focused specifically on the use of the newer medications.

On April 19, 2024, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published Newer Pharmacologic Treatments in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians. The internal medicine group recommends the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, and sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as second-line treatment after metformin. They also advise against the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

The document was also presented simultaneously at the ACP annual meeting.

And on April 15, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) posted its comprehensive Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024 Abridged for Primary Care Professionals as a follow-up to the December 2023 publication of its full-length Standards. Section 9, Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment, covers the same ground as the ACP guidelines.

General Agreement but Some Differences

The recommendations generally agree regarding medication use, although there are some differences. Both societies continue to endorse metformin and lifestyle modification as first-line therapy for glycemic management in type 2 diabetes. However, while ADA also gives the option of initial combination therapy with prioritization of avoiding hypoglycemia, ACP advises adding new medications only if glycemic goals aren’t met with lifestyle and metformin alone.

The new ACP document gives two general recommendations:

1. Add an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 agonist to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control.

*Use an SGLT2 inhibitor to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, progression of chronic kidney disease, and hospitalization due to congestive heart failure.

*Use a GLP-1 agonist to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and stroke.

2. ACP recommends against adding a DPP-4 inhibitor to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control to reduce morbidity and all-cause mortality.

Both ADA and ACP advise using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with congestive heart failure and/or chronic kidney disease, and using GLP-1 agonists in patients for whom weight management is a priority. The ADA also advises using agents of either drug class with proven cardiovascular benefit for people with type 2 diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease or who are at high risk.

ADA doesn’t advise against the use of DPP-4 inhibitors but doesn’t prioritize them either. Both insulin and sulfonylureas remain options for both, but they also are lower priority due to their potential for causing hypoglycemia. ACP says that sulfonylureas and long-acting insulin are “inferior to SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists in reducing all-cause mortality and morbidity but may still have some limited value for glycemic control.”

The two groups continue to differ regarding A1c goals, although both recommend individualization. The ACP generally advises levels between 7% and 8% for most adults with type 2 diabetes, and de-intensification of pharmacologic agents for those with A1c levels below 6.5%. On the other hand, ADA recommends A1c levels < 7% as long as that can be achieved safely.

This is the first time ACP has addressed this topic in a guideline, panel chair Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, told this news organization. “Diabetes treatment, of course, is our bread and butter…but what we had done before was based on the need to identify a target, like glycosylated hemoglobin. What patients and physicians really want to know now is, who should receive these new drugs? Should they receive these new drugs? And what benefits do they have?”

Added Dr. Crandall, who is professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “At ACP we have a complicated process that I’m actually very proud of, where we’ve asked a lay public panel, as well at the members of our guideline committee, to rank what’s most important in terms of the health outcomes for this condition…And then we look at how to balance those risks and benefits to make the recommendations.”

In the same Annals of Internal Medicine issue are two systematic reviews/meta-analyses that informed the new document, one on drug effectiveness and the other on cost-effectiveness.

In the accompanying editorial from Fatima Z. Syed, MD, an internist and medical weight management specialist at Duke University Division of General Internal Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, she notes, “the potential added benefits of these newer medications, including weight loss and cardiovascular and renal benefits, motivate their prescription, but cost and prior authorization hurdles can bar their use.”

Dr. Syed cites as “missing” from the ACP guidelines an analysis of comorbidities, including obesity. The reason for that, according to the document, is that “weight loss, as measured by percentage of participants who achieved at least 10% total body weight loss, was a prioritized outcome, but data were insufficient for network meta-analysis.”

However, Dr. Syed notes that factoring in weight loss could improve the cost-effectiveness of the newer medications. She points out that the ADA Standards suggest a GLP-1 agonist with or without metformin as initial therapy options for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes who might benefit from weight loss.

“The ACP guidelines strengthen the case for metformin as first-line medication for diabetes when comorbid conditions are not present. Metformin is cost-effective and has excellent hemoglobin A1c reduction. The accompanying economic analysis tells us that in the absence of comorbidity, the newer medication classes do not seem to be cost-effective. However, given that many patients with type 2 diabetes have obesity or existing cardiovascular or renal disease, the choice and accessibility of newer medications can be nuanced. The cost-effectiveness of GLP1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors as initial diabetes therapy in the setting of various comorbid conditions warrants careful exploration.”

Dr. Crandall has no disclosures. Dr. Syed disclosed that her husband is employed by Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Two professional societies have issued new guidance for type 2 diabetes management in primary care, with one focused specifically on the use of the newer medications.

On April 19, 2024, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published Newer Pharmacologic Treatments in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes: A Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians. The internal medicine group recommends the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, and sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors as second-line treatment after metformin. They also advise against the use of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors.

The document was also presented simultaneously at the ACP annual meeting.

And on April 15, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) posted its comprehensive Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024 Abridged for Primary Care Professionals as a follow-up to the December 2023 publication of its full-length Standards. Section 9, Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment, covers the same ground as the ACP guidelines.

General Agreement but Some Differences

The recommendations generally agree regarding medication use, although there are some differences. Both societies continue to endorse metformin and lifestyle modification as first-line therapy for glycemic management in type 2 diabetes. However, while ADA also gives the option of initial combination therapy with prioritization of avoiding hypoglycemia, ACP advises adding new medications only if glycemic goals aren’t met with lifestyle and metformin alone.

The new ACP document gives two general recommendations:

1. Add an SGLT2 inhibitor or a GLP-1 agonist to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control.

*Use an SGLT2 inhibitor to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, progression of chronic kidney disease, and hospitalization due to congestive heart failure.

*Use a GLP-1 agonist to reduce the risk for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and stroke.

2. ACP recommends against adding a DPP-4 inhibitor to metformin and lifestyle modifications in adults with type 2 diabetes and inadequate glycemic control to reduce morbidity and all-cause mortality.

Both ADA and ACP advise using SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with congestive heart failure and/or chronic kidney disease, and using GLP-1 agonists in patients for whom weight management is a priority. The ADA also advises using agents of either drug class with proven cardiovascular benefit for people with type 2 diabetes who have established cardiovascular disease or who are at high risk.

ADA doesn’t advise against the use of DPP-4 inhibitors but doesn’t prioritize them either. Both insulin and sulfonylureas remain options for both, but they also are lower priority due to their potential for causing hypoglycemia. ACP says that sulfonylureas and long-acting insulin are “inferior to SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists in reducing all-cause mortality and morbidity but may still have some limited value for glycemic control.”

The two groups continue to differ regarding A1c goals, although both recommend individualization. The ACP generally advises levels between 7% and 8% for most adults with type 2 diabetes, and de-intensification of pharmacologic agents for those with A1c levels below 6.5%. On the other hand, ADA recommends A1c levels < 7% as long as that can be achieved safely.

This is the first time ACP has addressed this topic in a guideline, panel chair Carolyn J. Crandall, MD, told this news organization. “Diabetes treatment, of course, is our bread and butter…but what we had done before was based on the need to identify a target, like glycosylated hemoglobin. What patients and physicians really want to know now is, who should receive these new drugs? Should they receive these new drugs? And what benefits do they have?”

Added Dr. Crandall, who is professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. “At ACP we have a complicated process that I’m actually very proud of, where we’ve asked a lay public panel, as well at the members of our guideline committee, to rank what’s most important in terms of the health outcomes for this condition…And then we look at how to balance those risks and benefits to make the recommendations.”

In the same Annals of Internal Medicine issue are two systematic reviews/meta-analyses that informed the new document, one on drug effectiveness and the other on cost-effectiveness.

In the accompanying editorial from Fatima Z. Syed, MD, an internist and medical weight management specialist at Duke University Division of General Internal Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, she notes, “the potential added benefits of these newer medications, including weight loss and cardiovascular and renal benefits, motivate their prescription, but cost and prior authorization hurdles can bar their use.”

Dr. Syed cites as “missing” from the ACP guidelines an analysis of comorbidities, including obesity. The reason for that, according to the document, is that “weight loss, as measured by percentage of participants who achieved at least 10% total body weight loss, was a prioritized outcome, but data were insufficient for network meta-analysis.”

However, Dr. Syed notes that factoring in weight loss could improve the cost-effectiveness of the newer medications. She points out that the ADA Standards suggest a GLP-1 agonist with or without metformin as initial therapy options for people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes who might benefit from weight loss.

“The ACP guidelines strengthen the case for metformin as first-line medication for diabetes when comorbid conditions are not present. Metformin is cost-effective and has excellent hemoglobin A1c reduction. The accompanying economic analysis tells us that in the absence of comorbidity, the newer medication classes do not seem to be cost-effective. However, given that many patients with type 2 diabetes have obesity or existing cardiovascular or renal disease, the choice and accessibility of newer medications can be nuanced. The cost-effectiveness of GLP1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors as initial diabetes therapy in the setting of various comorbid conditions warrants careful exploration.”

Dr. Crandall has no disclosures. Dr. Syed disclosed that her husband is employed by Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatric Clinic Doubles Well-Visit Data Capture by Going Completely Paperless

TORONTO — , and, of course, it eliminated the work associated with managing paper records.

Due to the efficacy of the pre-visit capture, “all of the information — including individual responses and total scores — is available to the provider at a glance” by the time of the examination encounter, according to Brian T. Ketterman, MD, a third-year resident in pediatrics at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Urgent issues, such as suicidality risk, “are flagged so that they are seen first,” he added.

The goal of going paperless was to improve the amount and the consistency of data captured with each well visit, according to Dr. Ketterman. He described a major undertaking involving fundamental changes in the electronic medical record (EMR) system to accommodate the new approach.

Characterizing screening at well visits as “one of the most important jobs of a pediatrician” when he presented these data at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, he added that a paperless approach comes with many advantages.

Raising the Rate of Complete Data Capture

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has identified more than 30 screening elements at well-child visits. At his institution several additional screening elements have been added. Prior to going paperless, about 45.6% on average of this well-visit data was being captured in any specific patient encounter, even if the institution was doing well overall in capturing essential information, such as key laboratory values and immunizations.

The vast majority of the information that was missing depended on patient or family input, such as social determinants of health (SDoH), which includes the aspects of home environment, such as nutrition and safety. Dr. Ketterman said that going paperless was inspired by positive experiences reported elsewhere.

“We wanted to build on this work,” he said.

The goal of the program was to raise the rate of complete data capture at well visits to at least 80% and do this across all languages. The first step was to create digital forms in English and Spanish for completion unique to each milestone well-child visit defined by age. For those who speak English or Spanish, these forms were supplied through the patient portal several days before the visit.

For those who spoke one of the more than 40 other languages encountered among patients at Dr. Ketterman’s institution, an interpreter was supplied. If patients arrived at the clinic without completing the digital entry, they completed it on a tablet with the help of an interpreter if one was needed.

Prior to going paperless, all screening data were captured on paper forms completed in the waiting room. The provider then manually reviewed and scored the forms before they were then scanned into the medical records. The paperless approach has eliminated all of these steps and the information is already available for review by the time the pediatrician enters the examination room.

With more than 50,000 well-child checkups captured over a recent 15-month period of paperless questionnaires, the proportion with 100% data capture using what Dr. Ketterman characterized as “strict criteria” was 84%, surpassing the goal at the initiation of the program.

“We improved in almost every screening measure,” Dr. Ketterman said, providing P values that were mostly < .001 for a range of standard tests such as M-CHAT-R (Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers), QPA (Quick Parenting Assessment), and PSC-17 (Pediatric Symptom Checklist) when compared to the baseline period.

Additional Advantages

The improvement in well-visit data capture was the goal, but the list of other advantages of the paperless system is long. For one, the EMR system now automatically uses the data to offer guidance that might improve patient outcomes. For example, if the family reports that the child does not see a dentist or does not know how to swim, these lead prompt the EMR to provide resources, such as the names of dentists of swim programs, to address the problem.

As another example, screening questions that reveal food insecurity automatically trigger guidance for enrolling in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) food program. According to Dr. Ketterman, the proportion of children now enrolled in WIC has increased 10-fold from baseline. He also reported there was a twofold increase in the proportion of patients enrolled in a free book program as a result of a screening questions that ask about reading at home.

The improvement in well-visit data capture was seen across all languages. Even if the gains were not quite as good in languages other than English or Spanish, they were still highly significant relative to baseline.

A ‘Life-Changing’ Improvement

The discussion following his talk made it clear that similar approaches are being actively pursued nationwide. Several in the audience working on similar programs identified such challenges as getting electronic medical record (EMR) systems to cooperate, ensuring patient enrollment in the portals, and avoiding form completion fatigue, but the comments were uniformly supportive of the benefits of this approach.

“This has been life-changing for us,” said Katie E. McPeak, MD, a primary care pediatrician and Medical Director for Health Equity at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “The information is more accurate in the digital format and it reduces time for the clinician reviewing the data in the exam room.” She also agreed that paperless completion of screen captures better information on more topics, like sleep, nutrition, and mood disorders.

However, Dr. McPeak was one of those who was concerned about form fatigue. Patients have to enter extensive information over multiple screens for each well-child visit. She said this problem might need to be addressed if the success of paperless screening leads to even greater expansion of data requested.

In addressing the work behind creating a system of the depth and scope of the one he described, Dr. Ketterman acknowledged that it involved a daunting development process with substantial coding and testing. Referring to the EMR system used at his hospital, he said the preparation required an “epic guru,” but he said that input fatigue has not yet arisen as a major issue.

“Many of the screens are mandatory, so you cannot advance without completing them, but some are optional,” he noted. “However, we are seeing a high rate of response even on the screens they could click past.”

Dr. Ketterman and Dr. McPeak report no potential conflicts of interest.

TORONTO — , and, of course, it eliminated the work associated with managing paper records.

Due to the efficacy of the pre-visit capture, “all of the information — including individual responses and total scores — is available to the provider at a glance” by the time of the examination encounter, according to Brian T. Ketterman, MD, a third-year resident in pediatrics at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Urgent issues, such as suicidality risk, “are flagged so that they are seen first,” he added.

The goal of going paperless was to improve the amount and the consistency of data captured with each well visit, according to Dr. Ketterman. He described a major undertaking involving fundamental changes in the electronic medical record (EMR) system to accommodate the new approach.

Characterizing screening at well visits as “one of the most important jobs of a pediatrician” when he presented these data at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, he added that a paperless approach comes with many advantages.

Raising the Rate of Complete Data Capture

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has identified more than 30 screening elements at well-child visits. At his institution several additional screening elements have been added. Prior to going paperless, about 45.6% on average of this well-visit data was being captured in any specific patient encounter, even if the institution was doing well overall in capturing essential information, such as key laboratory values and immunizations.

The vast majority of the information that was missing depended on patient or family input, such as social determinants of health (SDoH), which includes the aspects of home environment, such as nutrition and safety. Dr. Ketterman said that going paperless was inspired by positive experiences reported elsewhere.

“We wanted to build on this work,” he said.

The goal of the program was to raise the rate of complete data capture at well visits to at least 80% and do this across all languages. The first step was to create digital forms in English and Spanish for completion unique to each milestone well-child visit defined by age. For those who speak English or Spanish, these forms were supplied through the patient portal several days before the visit.

For those who spoke one of the more than 40 other languages encountered among patients at Dr. Ketterman’s institution, an interpreter was supplied. If patients arrived at the clinic without completing the digital entry, they completed it on a tablet with the help of an interpreter if one was needed.

Prior to going paperless, all screening data were captured on paper forms completed in the waiting room. The provider then manually reviewed and scored the forms before they were then scanned into the medical records. The paperless approach has eliminated all of these steps and the information is already available for review by the time the pediatrician enters the examination room.

With more than 50,000 well-child checkups captured over a recent 15-month period of paperless questionnaires, the proportion with 100% data capture using what Dr. Ketterman characterized as “strict criteria” was 84%, surpassing the goal at the initiation of the program.

“We improved in almost every screening measure,” Dr. Ketterman said, providing P values that were mostly < .001 for a range of standard tests such as M-CHAT-R (Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers), QPA (Quick Parenting Assessment), and PSC-17 (Pediatric Symptom Checklist) when compared to the baseline period.

Additional Advantages

The improvement in well-visit data capture was the goal, but the list of other advantages of the paperless system is long. For one, the EMR system now automatically uses the data to offer guidance that might improve patient outcomes. For example, if the family reports that the child does not see a dentist or does not know how to swim, these lead prompt the EMR to provide resources, such as the names of dentists of swim programs, to address the problem.

As another example, screening questions that reveal food insecurity automatically trigger guidance for enrolling in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) food program. According to Dr. Ketterman, the proportion of children now enrolled in WIC has increased 10-fold from baseline. He also reported there was a twofold increase in the proportion of patients enrolled in a free book program as a result of a screening questions that ask about reading at home.

The improvement in well-visit data capture was seen across all languages. Even if the gains were not quite as good in languages other than English or Spanish, they were still highly significant relative to baseline.

A ‘Life-Changing’ Improvement

The discussion following his talk made it clear that similar approaches are being actively pursued nationwide. Several in the audience working on similar programs identified such challenges as getting electronic medical record (EMR) systems to cooperate, ensuring patient enrollment in the portals, and avoiding form completion fatigue, but the comments were uniformly supportive of the benefits of this approach.

“This has been life-changing for us,” said Katie E. McPeak, MD, a primary care pediatrician and Medical Director for Health Equity at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “The information is more accurate in the digital format and it reduces time for the clinician reviewing the data in the exam room.” She also agreed that paperless completion of screen captures better information on more topics, like sleep, nutrition, and mood disorders.

However, Dr. McPeak was one of those who was concerned about form fatigue. Patients have to enter extensive information over multiple screens for each well-child visit. She said this problem might need to be addressed if the success of paperless screening leads to even greater expansion of data requested.

In addressing the work behind creating a system of the depth and scope of the one he described, Dr. Ketterman acknowledged that it involved a daunting development process with substantial coding and testing. Referring to the EMR system used at his hospital, he said the preparation required an “epic guru,” but he said that input fatigue has not yet arisen as a major issue.

“Many of the screens are mandatory, so you cannot advance without completing them, but some are optional,” he noted. “However, we are seeing a high rate of response even on the screens they could click past.”

Dr. Ketterman and Dr. McPeak report no potential conflicts of interest.

TORONTO — , and, of course, it eliminated the work associated with managing paper records.

Due to the efficacy of the pre-visit capture, “all of the information — including individual responses and total scores — is available to the provider at a glance” by the time of the examination encounter, according to Brian T. Ketterman, MD, a third-year resident in pediatrics at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee.

Urgent issues, such as suicidality risk, “are flagged so that they are seen first,” he added.

The goal of going paperless was to improve the amount and the consistency of data captured with each well visit, according to Dr. Ketterman. He described a major undertaking involving fundamental changes in the electronic medical record (EMR) system to accommodate the new approach.

Characterizing screening at well visits as “one of the most important jobs of a pediatrician” when he presented these data at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting, he added that a paperless approach comes with many advantages.

Raising the Rate of Complete Data Capture

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has identified more than 30 screening elements at well-child visits. At his institution several additional screening elements have been added. Prior to going paperless, about 45.6% on average of this well-visit data was being captured in any specific patient encounter, even if the institution was doing well overall in capturing essential information, such as key laboratory values and immunizations.

The vast majority of the information that was missing depended on patient or family input, such as social determinants of health (SDoH), which includes the aspects of home environment, such as nutrition and safety. Dr. Ketterman said that going paperless was inspired by positive experiences reported elsewhere.

“We wanted to build on this work,” he said.

The goal of the program was to raise the rate of complete data capture at well visits to at least 80% and do this across all languages. The first step was to create digital forms in English and Spanish for completion unique to each milestone well-child visit defined by age. For those who speak English or Spanish, these forms were supplied through the patient portal several days before the visit.

For those who spoke one of the more than 40 other languages encountered among patients at Dr. Ketterman’s institution, an interpreter was supplied. If patients arrived at the clinic without completing the digital entry, they completed it on a tablet with the help of an interpreter if one was needed.

Prior to going paperless, all screening data were captured on paper forms completed in the waiting room. The provider then manually reviewed and scored the forms before they were then scanned into the medical records. The paperless approach has eliminated all of these steps and the information is already available for review by the time the pediatrician enters the examination room.

With more than 50,000 well-child checkups captured over a recent 15-month period of paperless questionnaires, the proportion with 100% data capture using what Dr. Ketterman characterized as “strict criteria” was 84%, surpassing the goal at the initiation of the program.

“We improved in almost every screening measure,” Dr. Ketterman said, providing P values that were mostly < .001 for a range of standard tests such as M-CHAT-R (Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers), QPA (Quick Parenting Assessment), and PSC-17 (Pediatric Symptom Checklist) when compared to the baseline period.

Additional Advantages

The improvement in well-visit data capture was the goal, but the list of other advantages of the paperless system is long. For one, the EMR system now automatically uses the data to offer guidance that might improve patient outcomes. For example, if the family reports that the child does not see a dentist or does not know how to swim, these lead prompt the EMR to provide resources, such as the names of dentists of swim programs, to address the problem.

As another example, screening questions that reveal food insecurity automatically trigger guidance for enrolling in the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s WIC (Women, Infants, and Children) food program. According to Dr. Ketterman, the proportion of children now enrolled in WIC has increased 10-fold from baseline. He also reported there was a twofold increase in the proportion of patients enrolled in a free book program as a result of a screening questions that ask about reading at home.

The improvement in well-visit data capture was seen across all languages. Even if the gains were not quite as good in languages other than English or Spanish, they were still highly significant relative to baseline.

A ‘Life-Changing’ Improvement

The discussion following his talk made it clear that similar approaches are being actively pursued nationwide. Several in the audience working on similar programs identified such challenges as getting electronic medical record (EMR) systems to cooperate, ensuring patient enrollment in the portals, and avoiding form completion fatigue, but the comments were uniformly supportive of the benefits of this approach.

“This has been life-changing for us,” said Katie E. McPeak, MD, a primary care pediatrician and Medical Director for Health Equity at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “The information is more accurate in the digital format and it reduces time for the clinician reviewing the data in the exam room.” She also agreed that paperless completion of screen captures better information on more topics, like sleep, nutrition, and mood disorders.

However, Dr. McPeak was one of those who was concerned about form fatigue. Patients have to enter extensive information over multiple screens for each well-child visit. She said this problem might need to be addressed if the success of paperless screening leads to even greater expansion of data requested.

In addressing the work behind creating a system of the depth and scope of the one he described, Dr. Ketterman acknowledged that it involved a daunting development process with substantial coding and testing. Referring to the EMR system used at his hospital, he said the preparation required an “epic guru,” but he said that input fatigue has not yet arisen as a major issue.

“Many of the screens are mandatory, so you cannot advance without completing them, but some are optional,” he noted. “However, we are seeing a high rate of response even on the screens they could click past.”

Dr. Ketterman and Dr. McPeak report no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM PAS 2024

Multiple Asymptomatic Dome-Shaped Papules on the Scalp

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

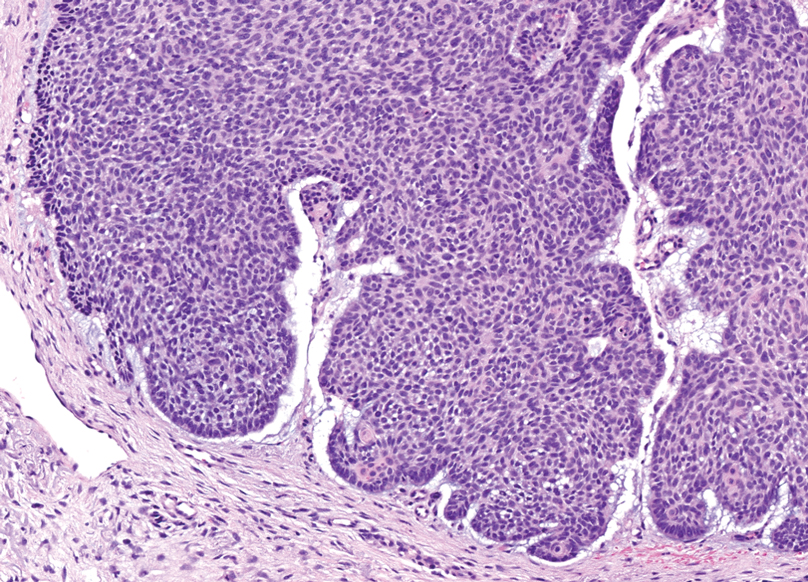

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

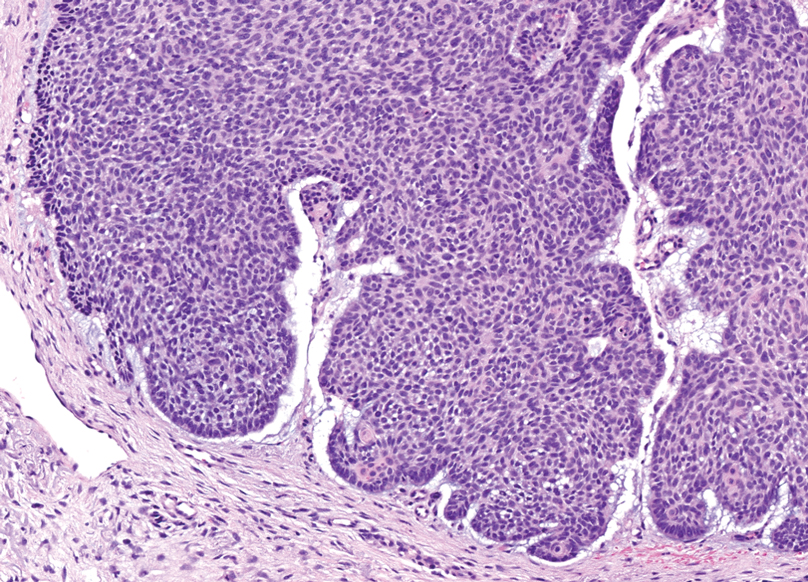

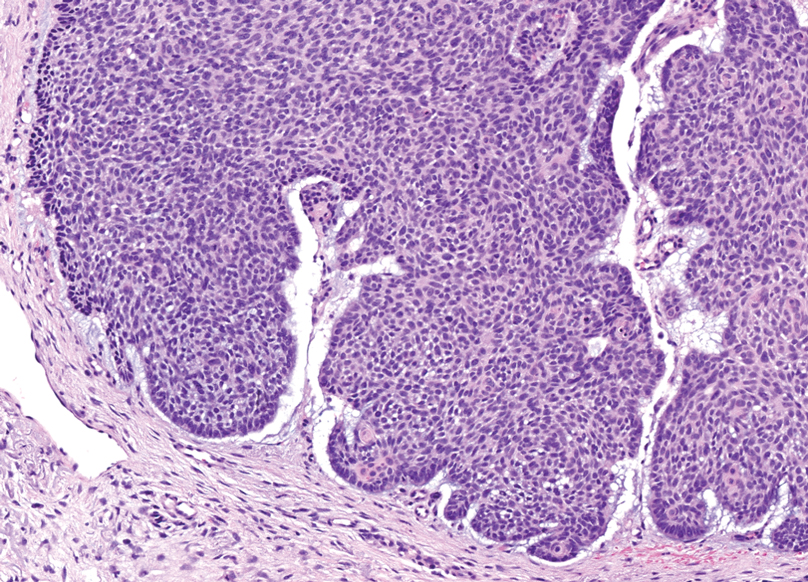

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

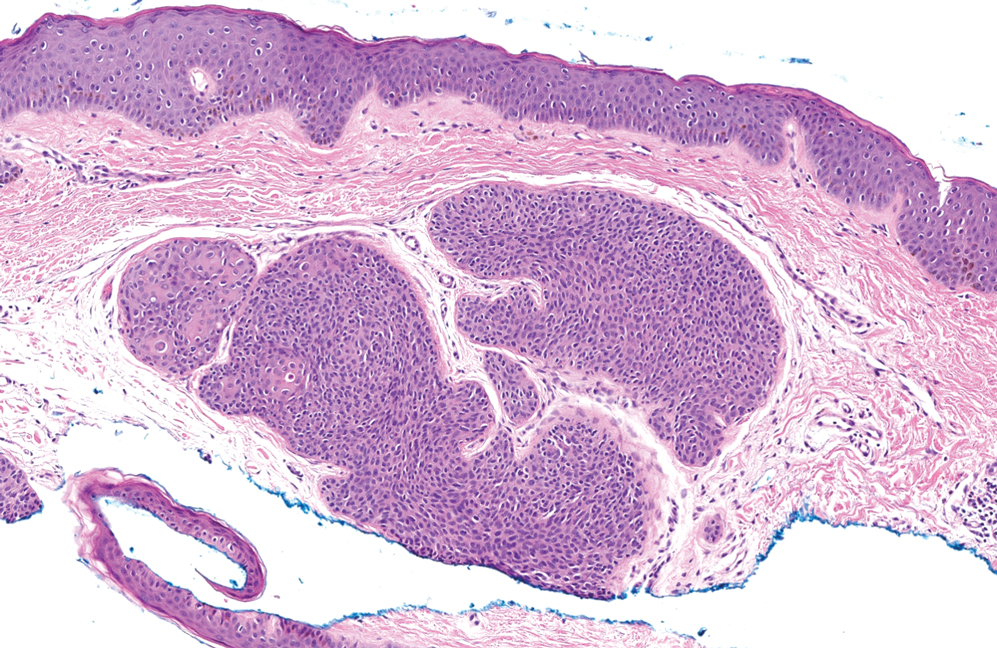

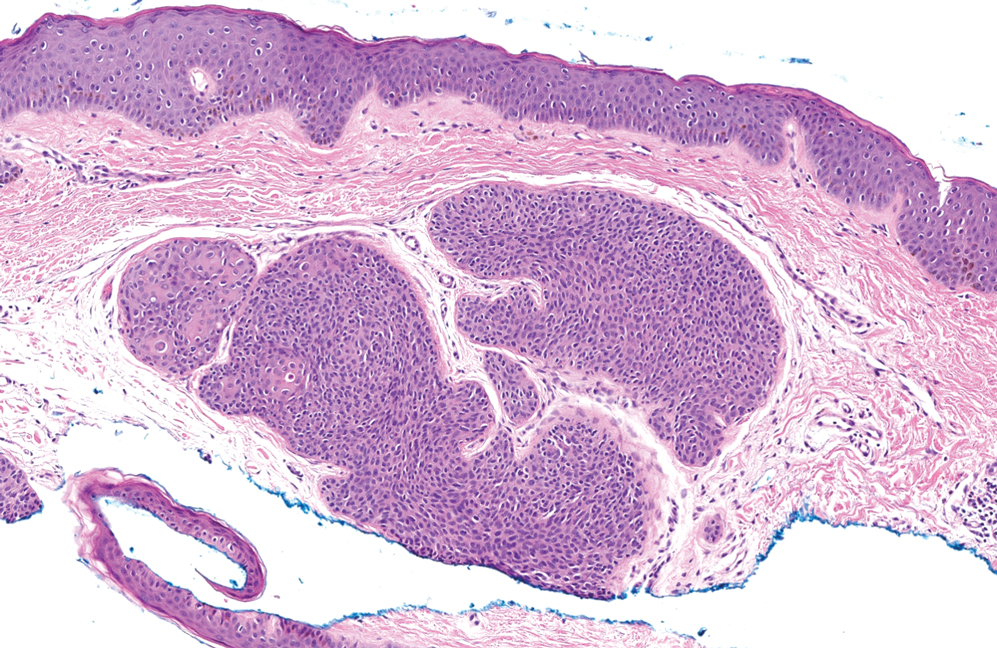

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

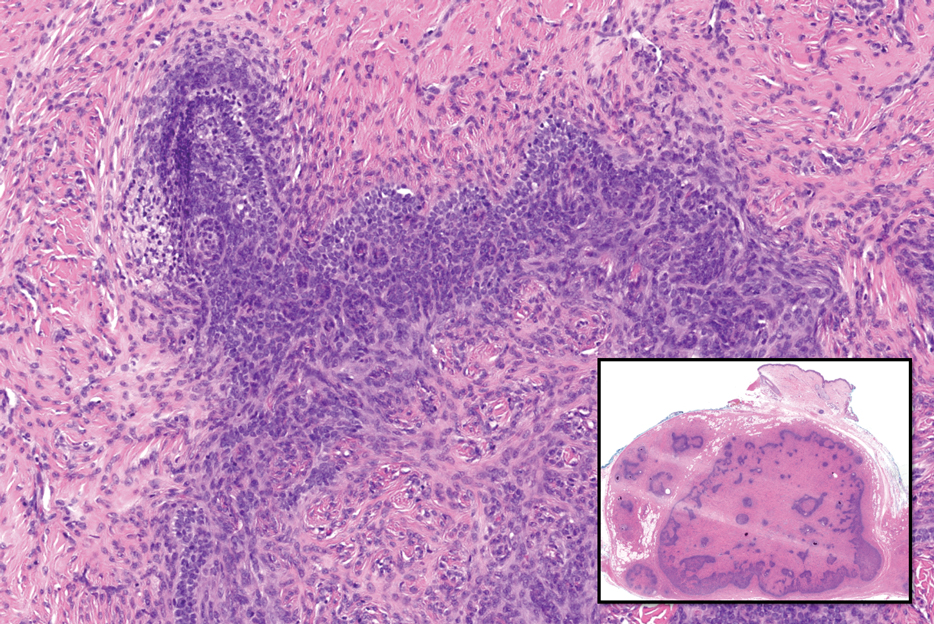

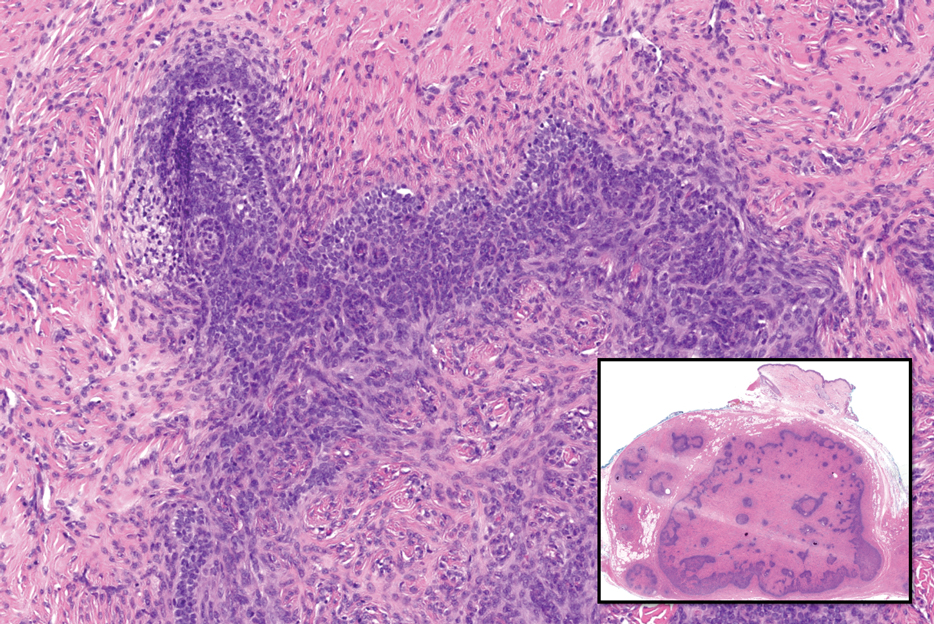

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

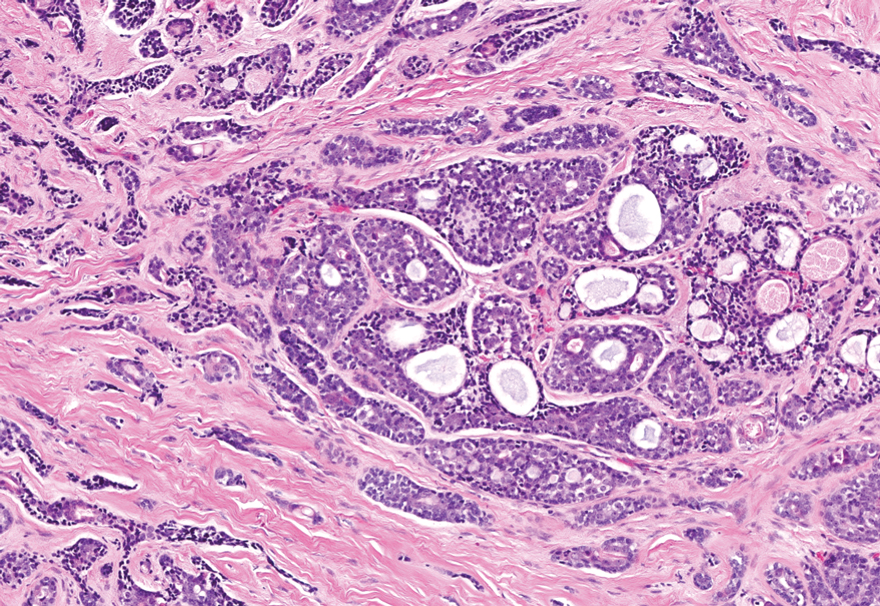

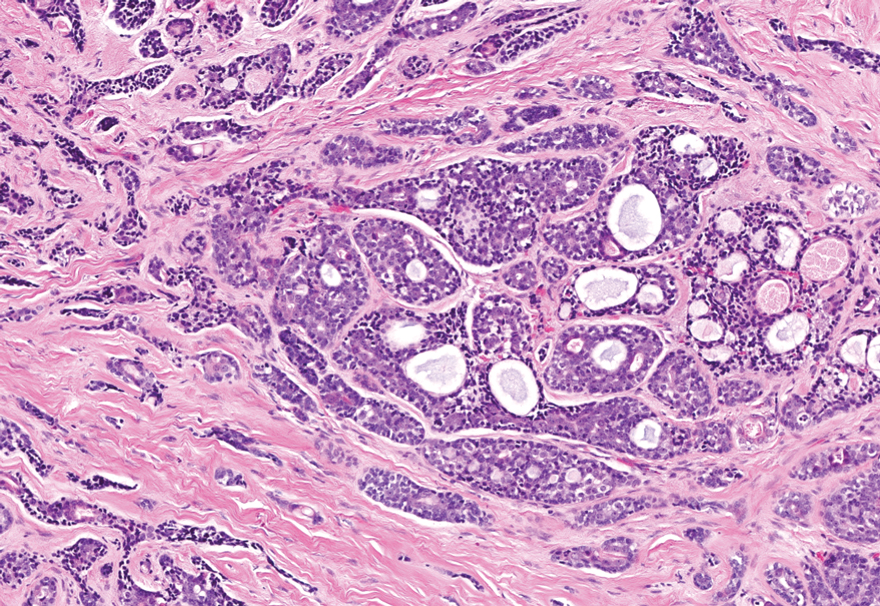

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

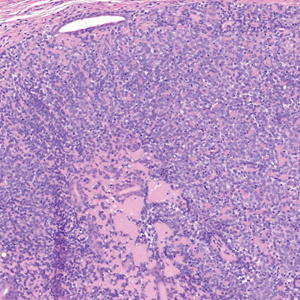

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

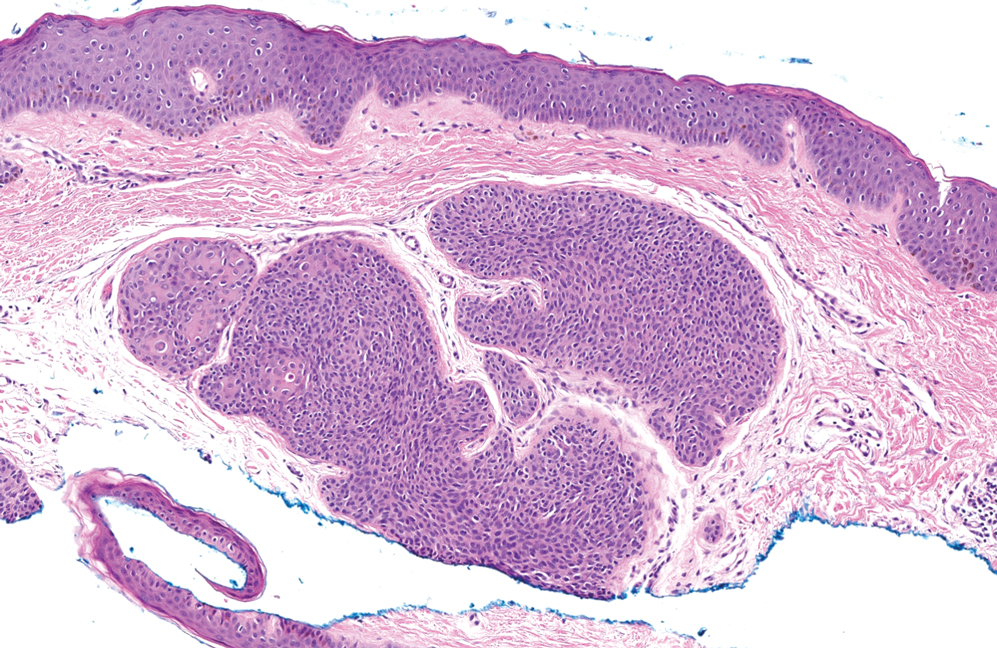

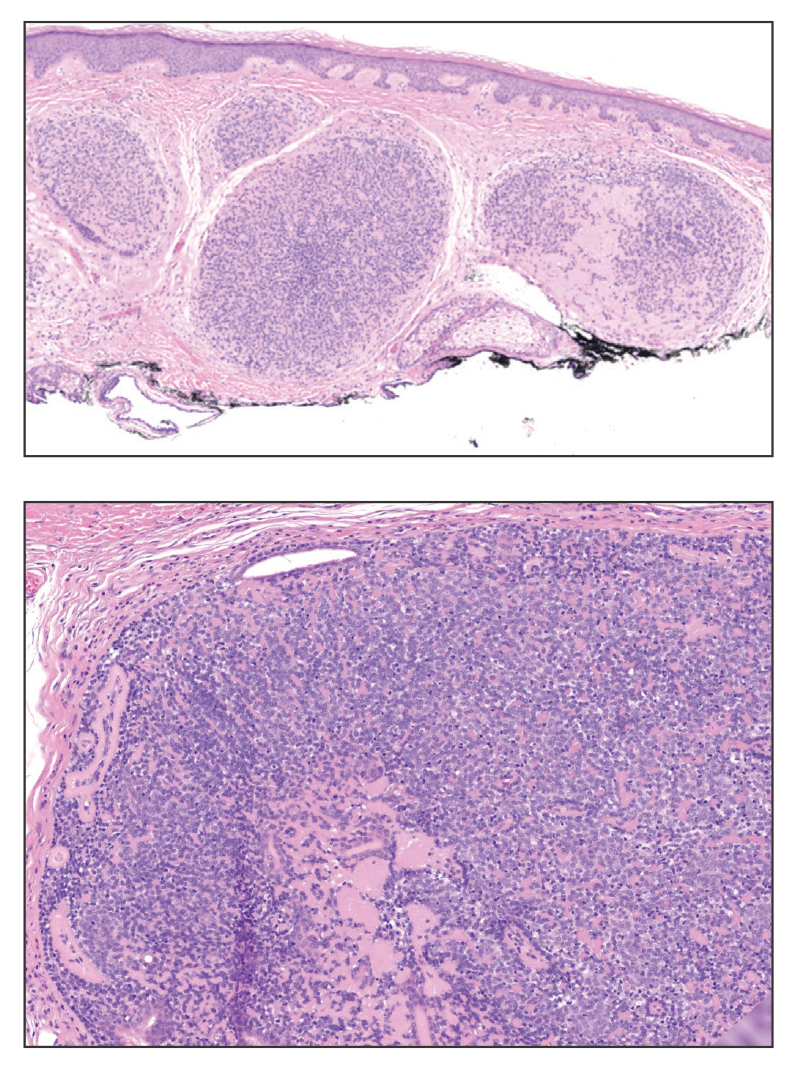

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

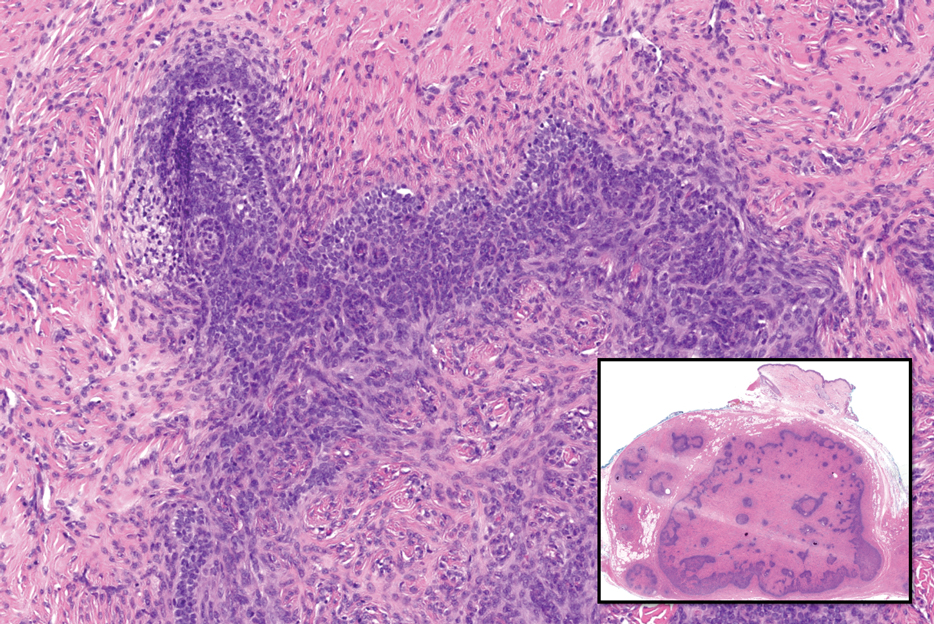

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

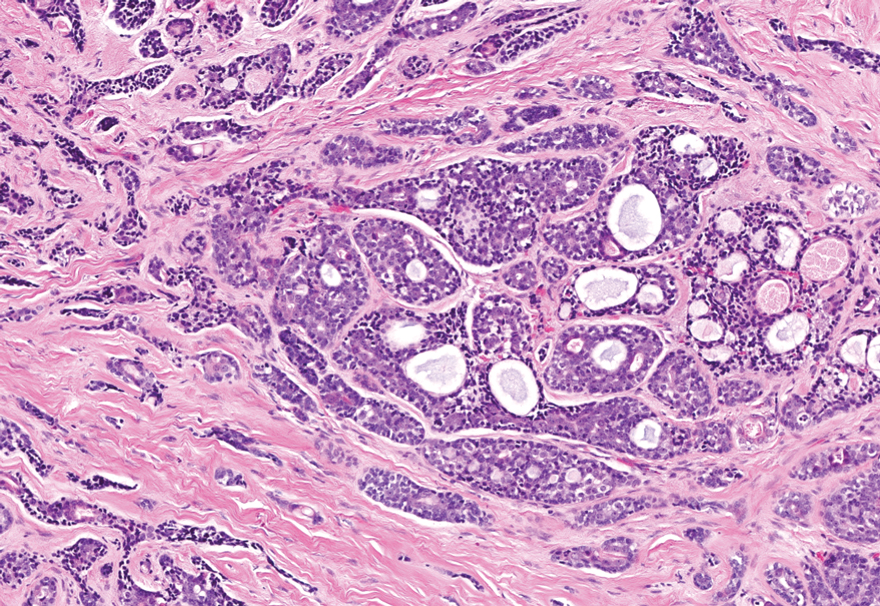

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

The Diagnosis: Spiradenocylindroma

Shave biopsies of our patient’s lesions showed wellcircumscribed dermal nodules resembling a spiradenoma with 3 cell populations: those with lighter nuclei, darker nuclei, and scattered lymphocytes. However, the conspicuous globules of basement membrane material were reminiscent of a cylindroma. These overlapping features and the patient’s history of cylindroma were suggestive of a diagnosis of spiradenocylindroma.

Spiradenocylindroma is an uncommon dermal tumor with features that overlap with spiradenoma and cylindroma.1 It may manifest as a solitary lesion or multiple lesions and can occur sporadically or in the context of a family history. Histologically, it must be distinguished from other intradermal basaloid neoplasms including conventional cylindroma and spiradenoma, dermal duct tumor, hidradenoma, and trichoblastoma.

When patients present with multiple cylindromas, spiradenomas, or spiradenocylindromas, physicians should consider genetic testing and review of the family history to assess for cylindromatosis gene mutations or Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. Biopsy and histologic examination are important because malignant tumors can evolve from pre-existing spiradenocylindromas, cylindromas, and spiradenomas,2 with an increased risk in patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome.1 Our patient declined further genetic workup but continues to follow up with dermatology for monitoring of lesions.

Dermal duct tumors are morphologic variants of poromas that are derived from sweat gland lineage and usually manifest as solitary dome-shaped papules, plaques, or nodules most often seen on acral surfaces as well as the head and neck.3 Clinically, they may be indistinguishable from spiradenocylindromas and require biopsy for histologic evaluation. They can be distinguished from spiradenocylindroma by the presence of small dermal nodules composed of cuboidal cells with ample pink cytoplasm and cuticle-lined ducts (Figure 1).

Trichoblastomas typically are deep-seated basaloid follicular neoplasms on the scalp with papillary mesenchyme resembling the normal fibrous sheath of the hair follicle, often replete with papillary mesenchymal bodies (Figure 2). There generally are no retraction spaces between its basaloid nests and the surrounding stroma, which is unlikely to contain mucin relative to basal cell carcinoma (BCC).4,5

Adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare salivary gland tumor that can metastasize to the skin and rarely arises as a primary skin adnexal tumor. It manifests as a slowgrowing mass that can be tender to palpation.6 Histologic examination shows dermal islands with cribriform blue and pink spaces. Compared to BCC, adenoid cystic carcinoma cells are enlarged and epithelioid with relatively scarce cytoplasm (Figure 3).6,7 Adenoid cystic carcinoma can show variable growth patterns including infiltrative nests and trabeculae. Perineural invasion is common, and there is a high risk for local recurrence.7 First-line therapy usually is surgical, and postoperative radiotherapy may be required.6,7

Nodular BCC commonly manifests as an enlarging nonhealing lesion on sun-exposed skin and has many subtypes, typically with arborizing telangiectases on dermoscopy. Histopathologic examination of nodular BCC reveals a nest of basaloid follicular germinative cells in the dermis with peripheral palisading and a fibromyxoid stroma (Figure 4).8 Patients with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome are at increased risk for nodular BCC, which may be clinically indistinguishable from spiradenoma, cylindroma, and spiradenocylindroma, necessitating histologic assessment.

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Facchini V, Colangeli W, Bozza F, et al. A rare histopathological spiradenocylindroma: a case report. Clin Ter. 2022;173:292-294. doi:10.7417/ CT.2022.2433

- Kazakov DV. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and phenotypic variants: an update [published online March 14, 2016]. Head Neck Pathol. 2016;10:125-30. doi:10.1007/s12105-016-0705-x

- Miller AC, Adjei S, Temiz LA, et al. Dermal duct tumor: a diagnostic dilemma. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022;9:36-47. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology9010007

- Elston DM. Pilar and sebaceous neoplasms. In: Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko C, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018:71-85.

- McCalmont TH, Pincus LB. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni, L. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2017:1930-1953.

- Coca-Pelaz A, Rodrigo JP, Bradley PJ, et al. Adenoid cystic carcinoma of the head and neck—an update [published online May 2, 2015]. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:652-661. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.04.005

- Tonev ID, Pirgova YS, Conev NV. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the skin with multiple local recurrences. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8:251- 255. doi:10.1159/000431082

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations [published online May 18, 2018]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

A 62-year-old man with a history of cylindromas presented to our clinic with multiple asymptomatic, 3- to 4-mm, nonmobile, dome-shaped, telangiectatic, pink papules over the parietal and vertex scalp that had been present for more than 10 years without change. Several family members had similar lesions that had not been evaluated by a physician, and there had been no genetic evaluation. Shave biopsies of several lesions were performed.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Care for Patients With Skin Cancer

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

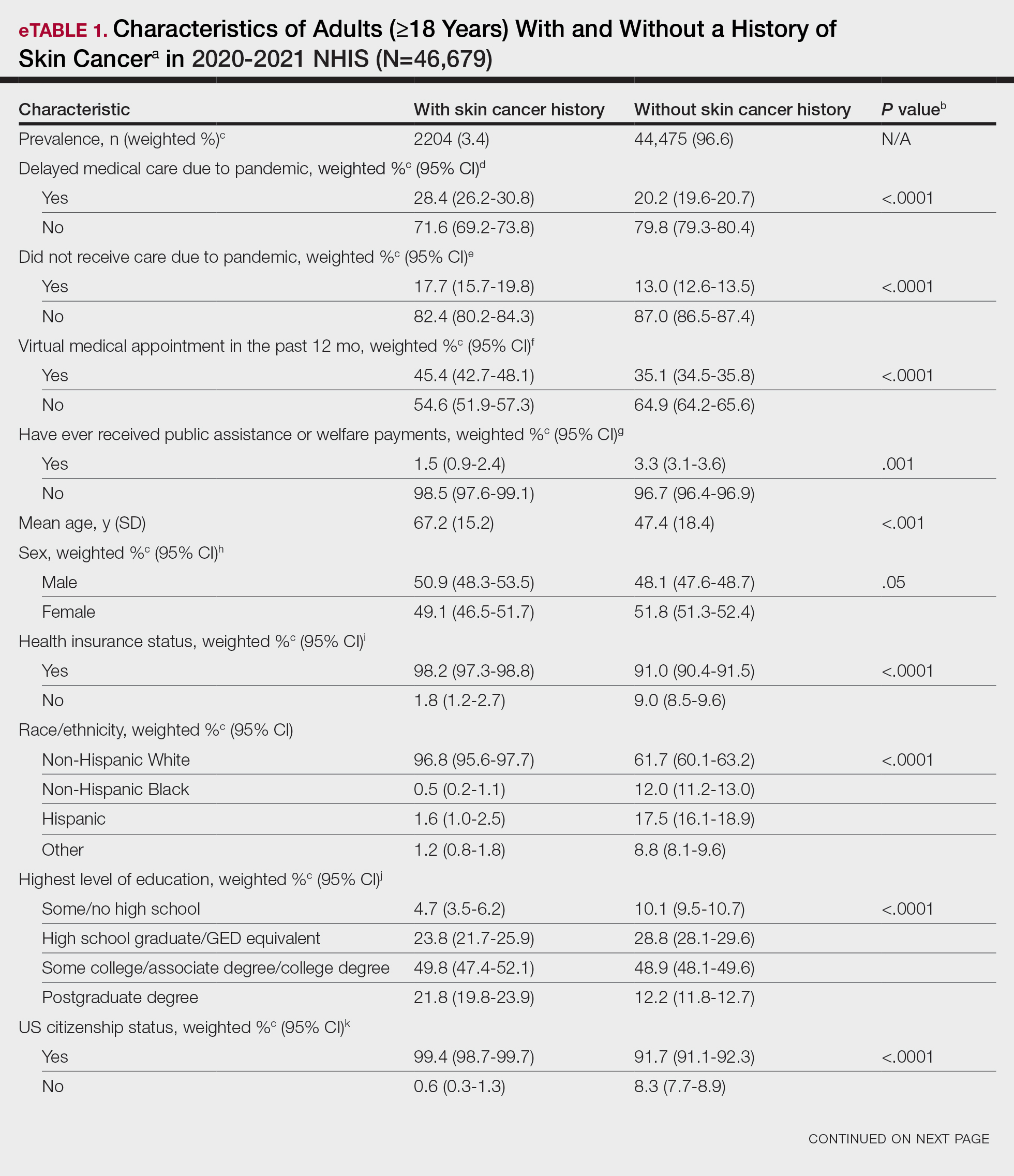

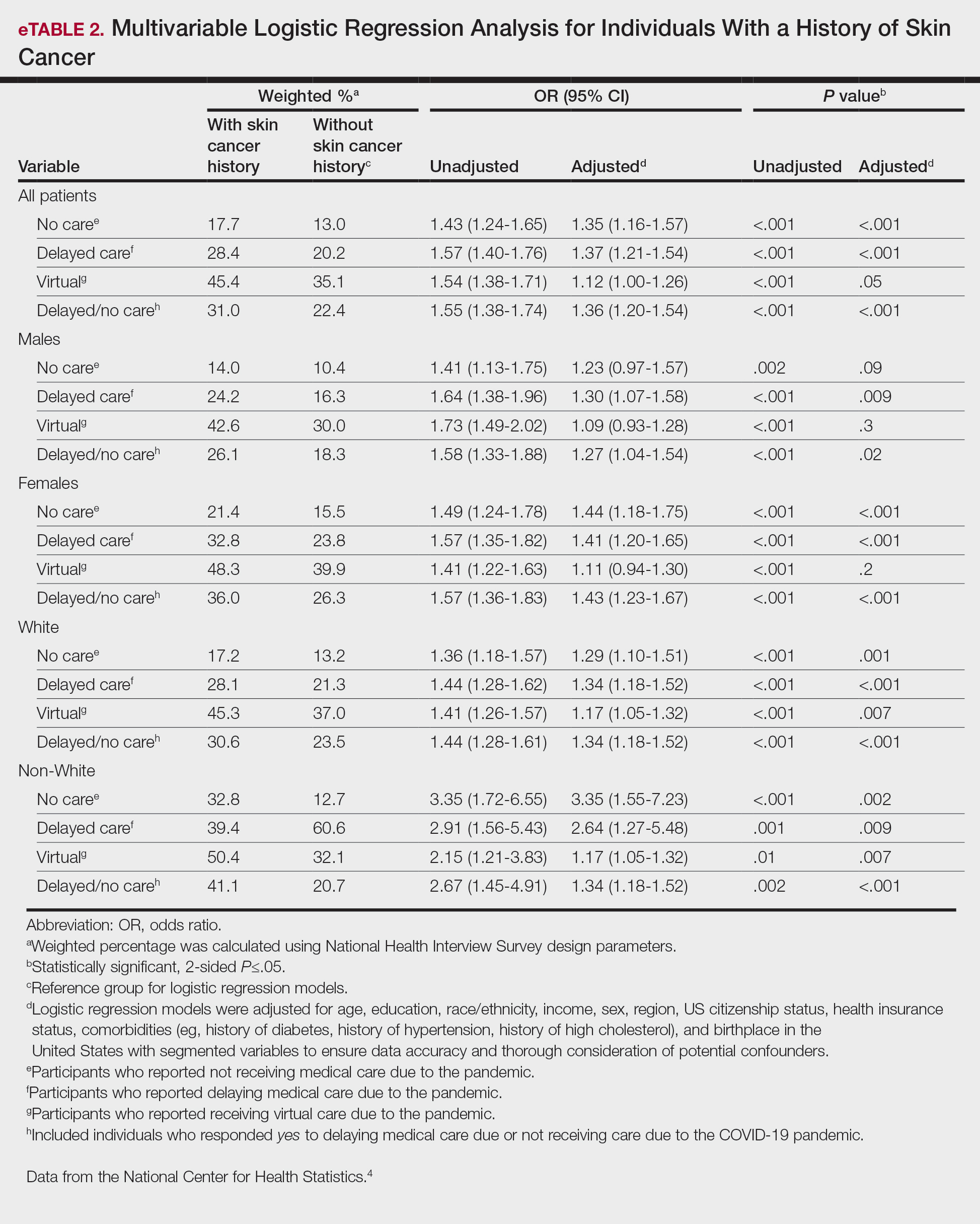

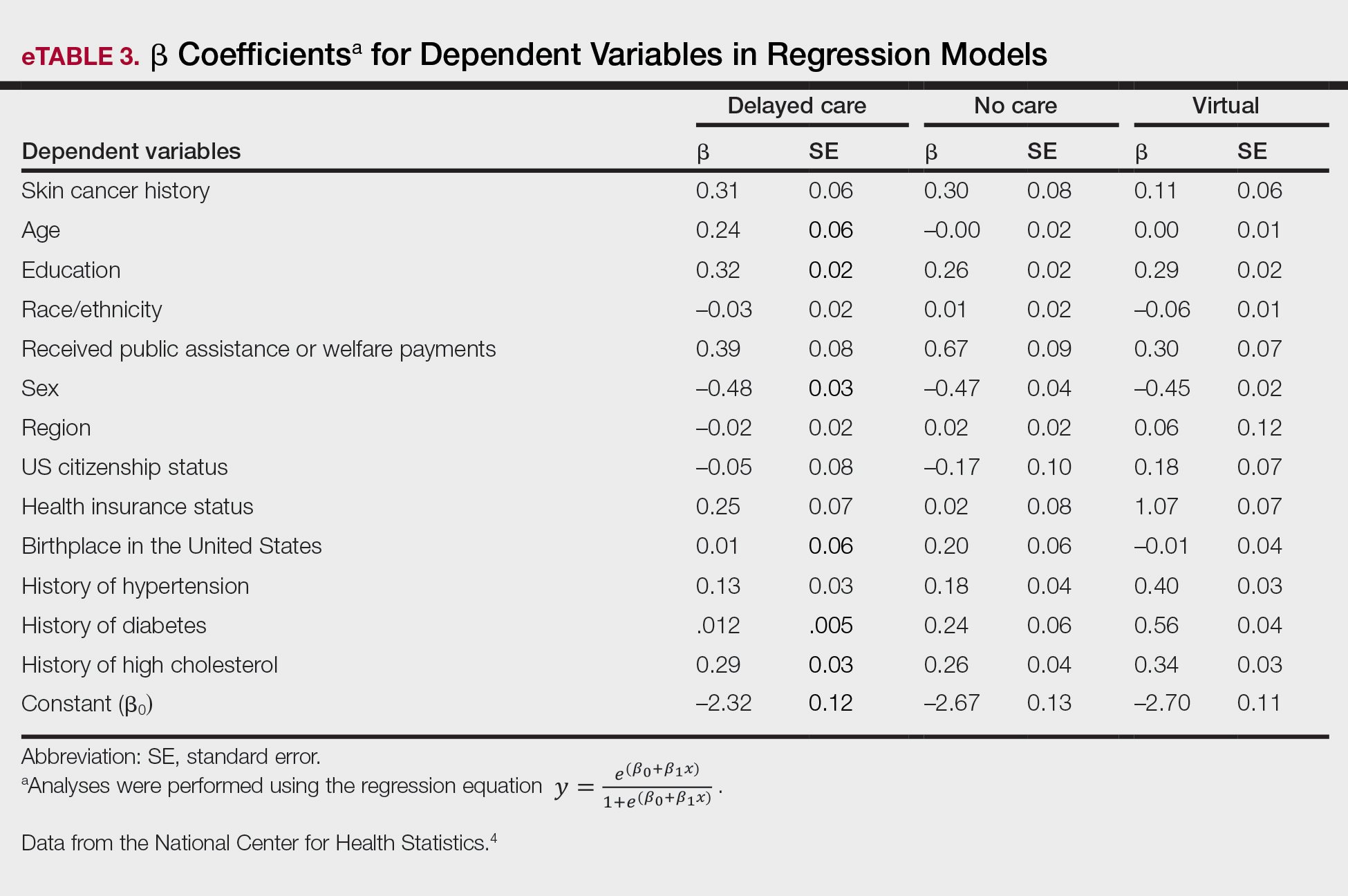

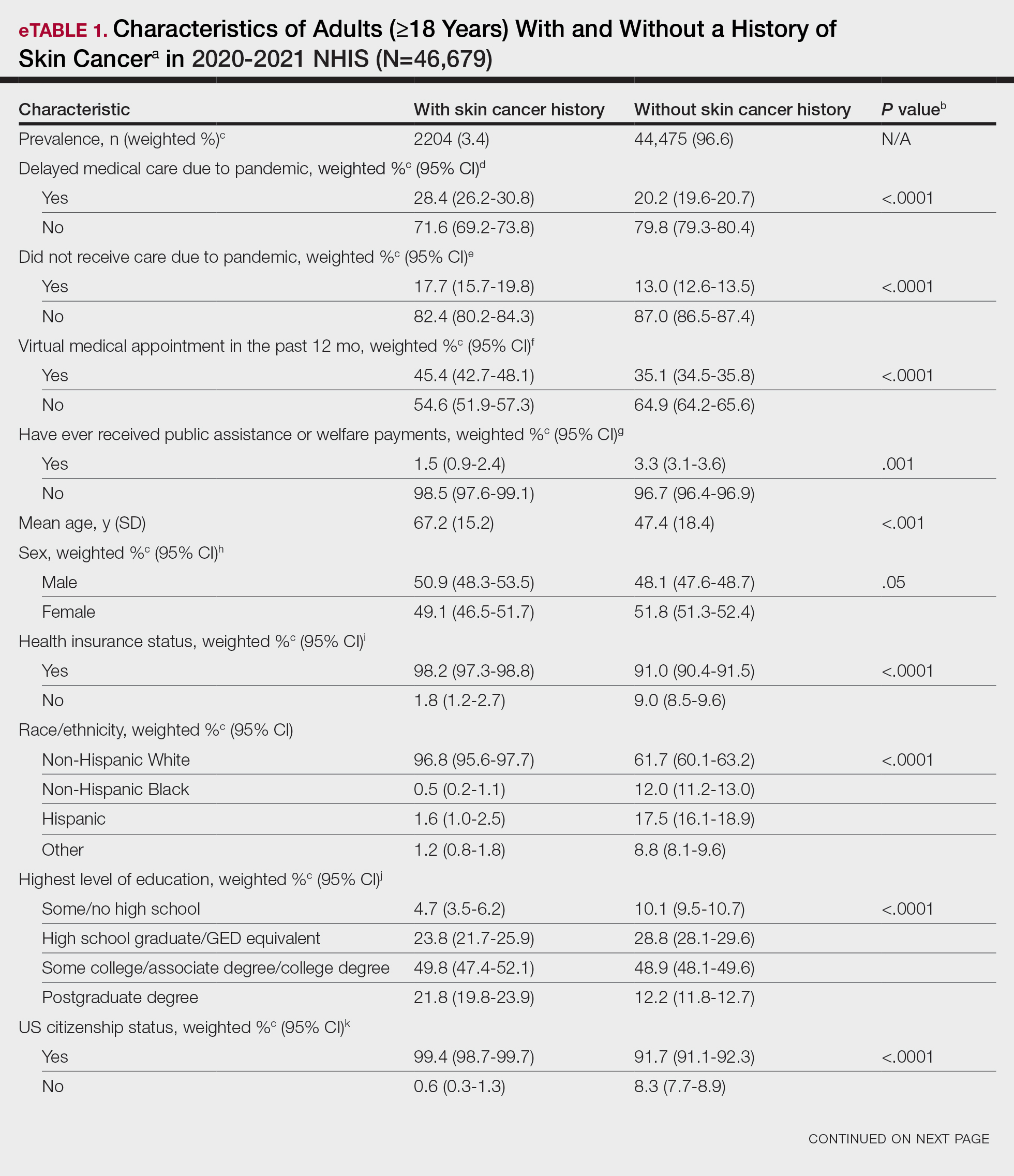

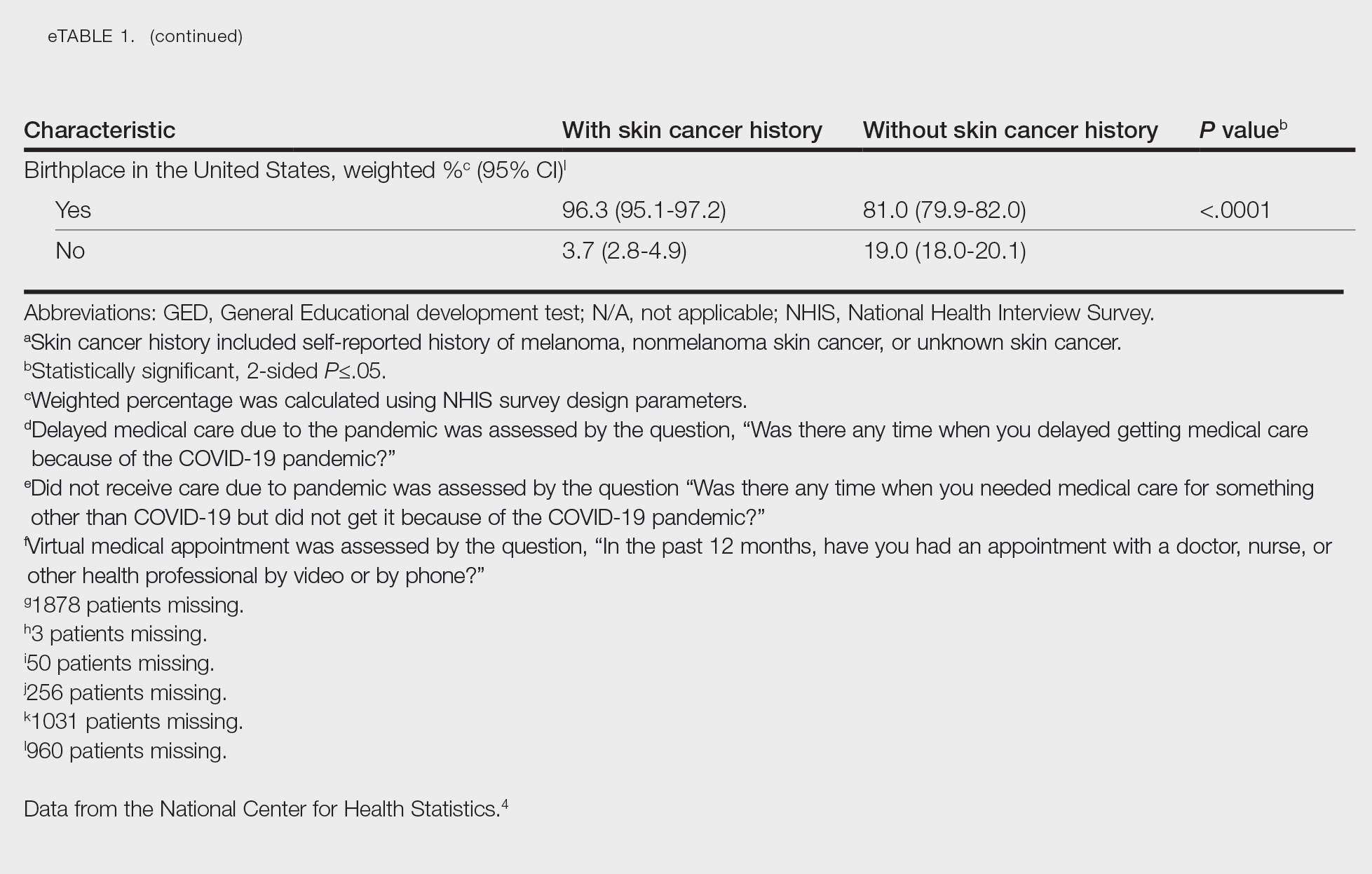

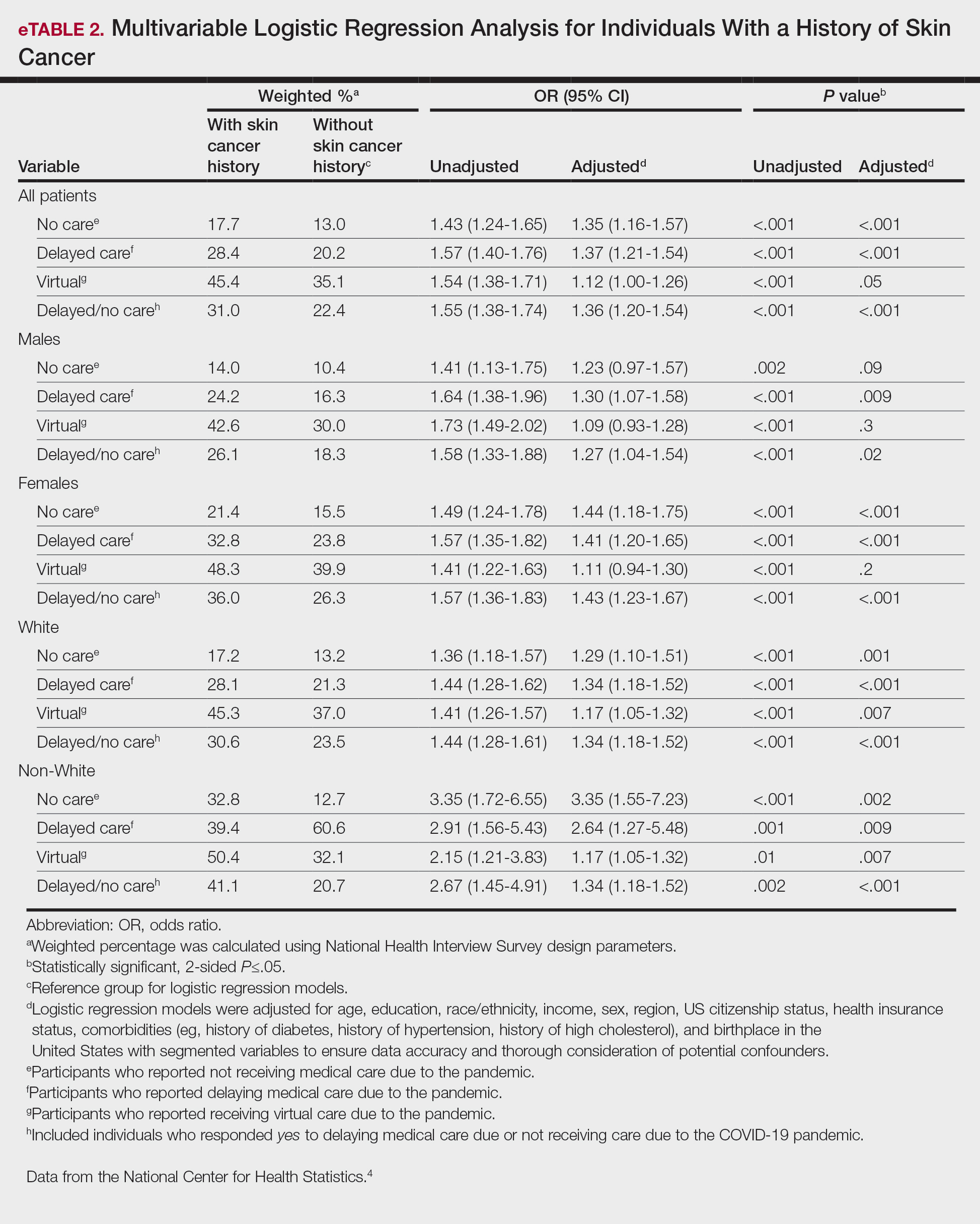

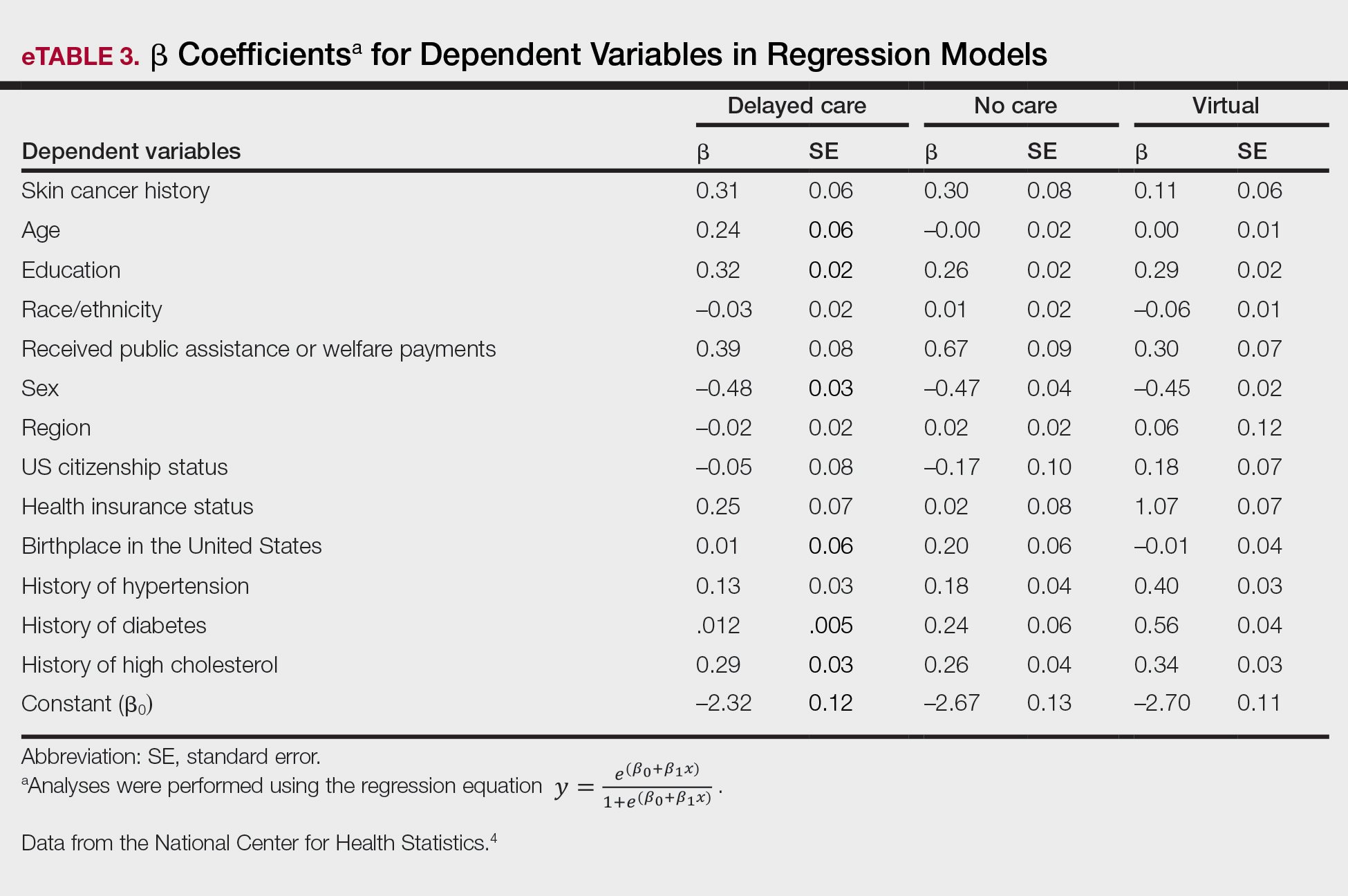

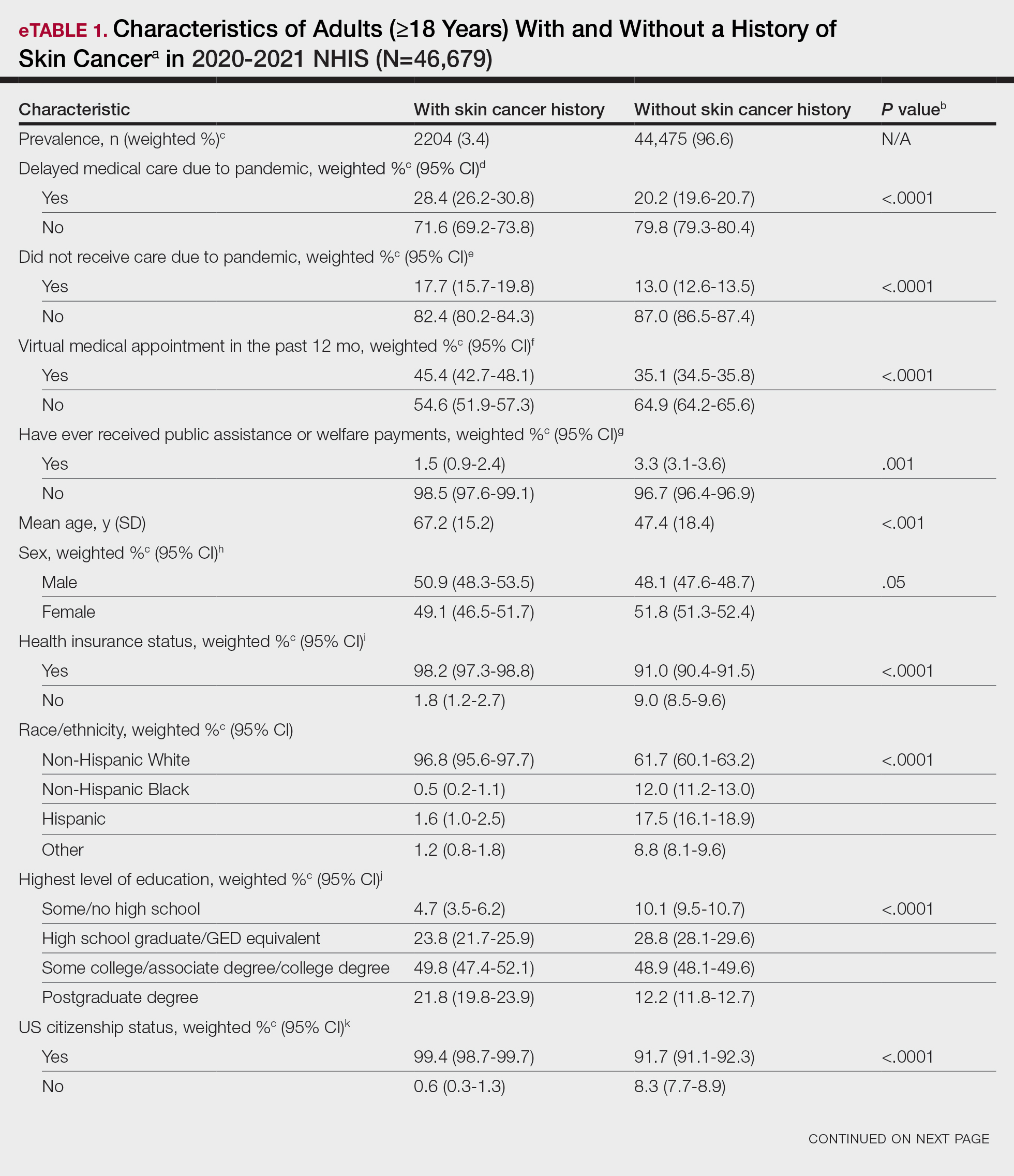

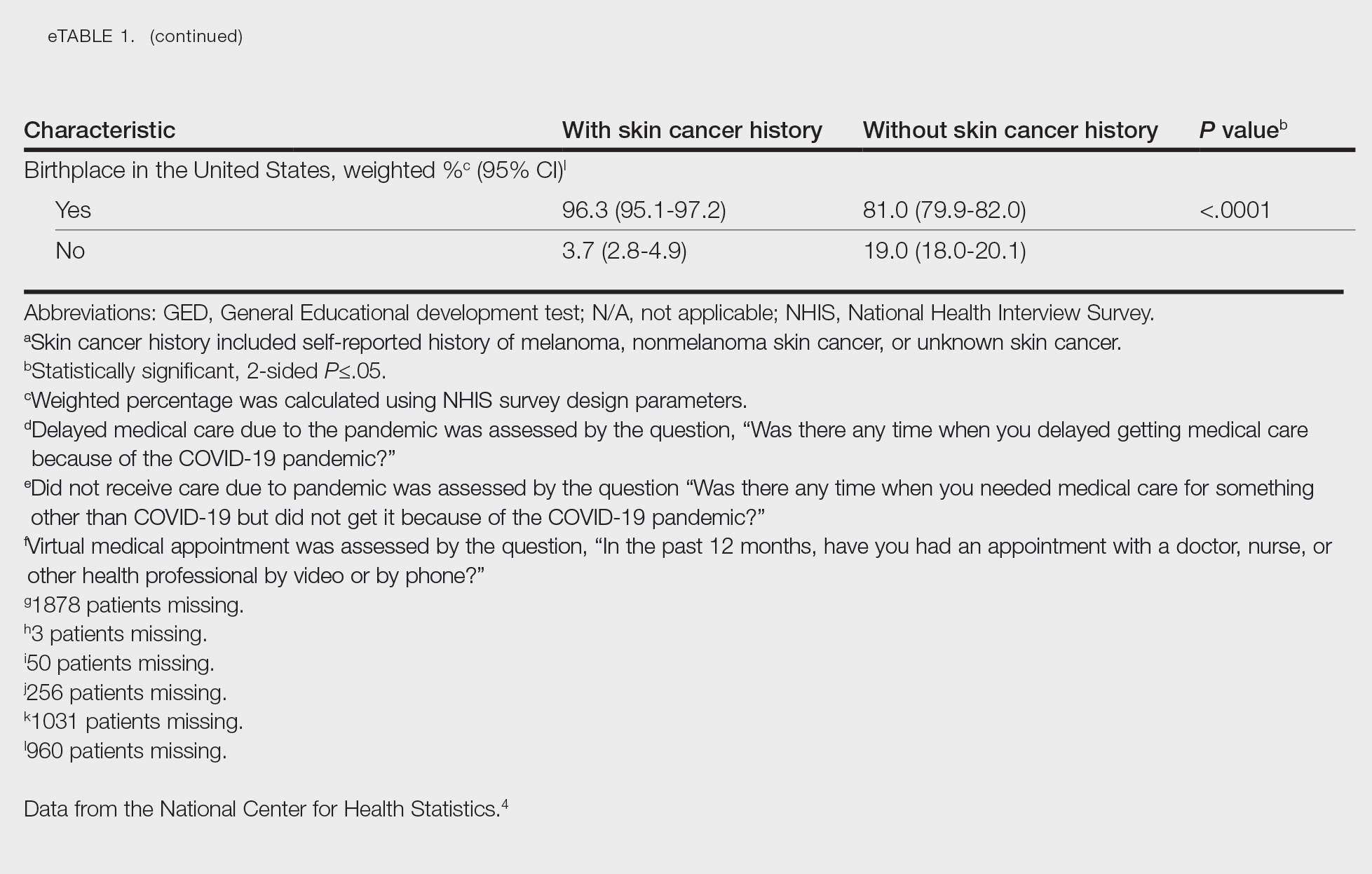

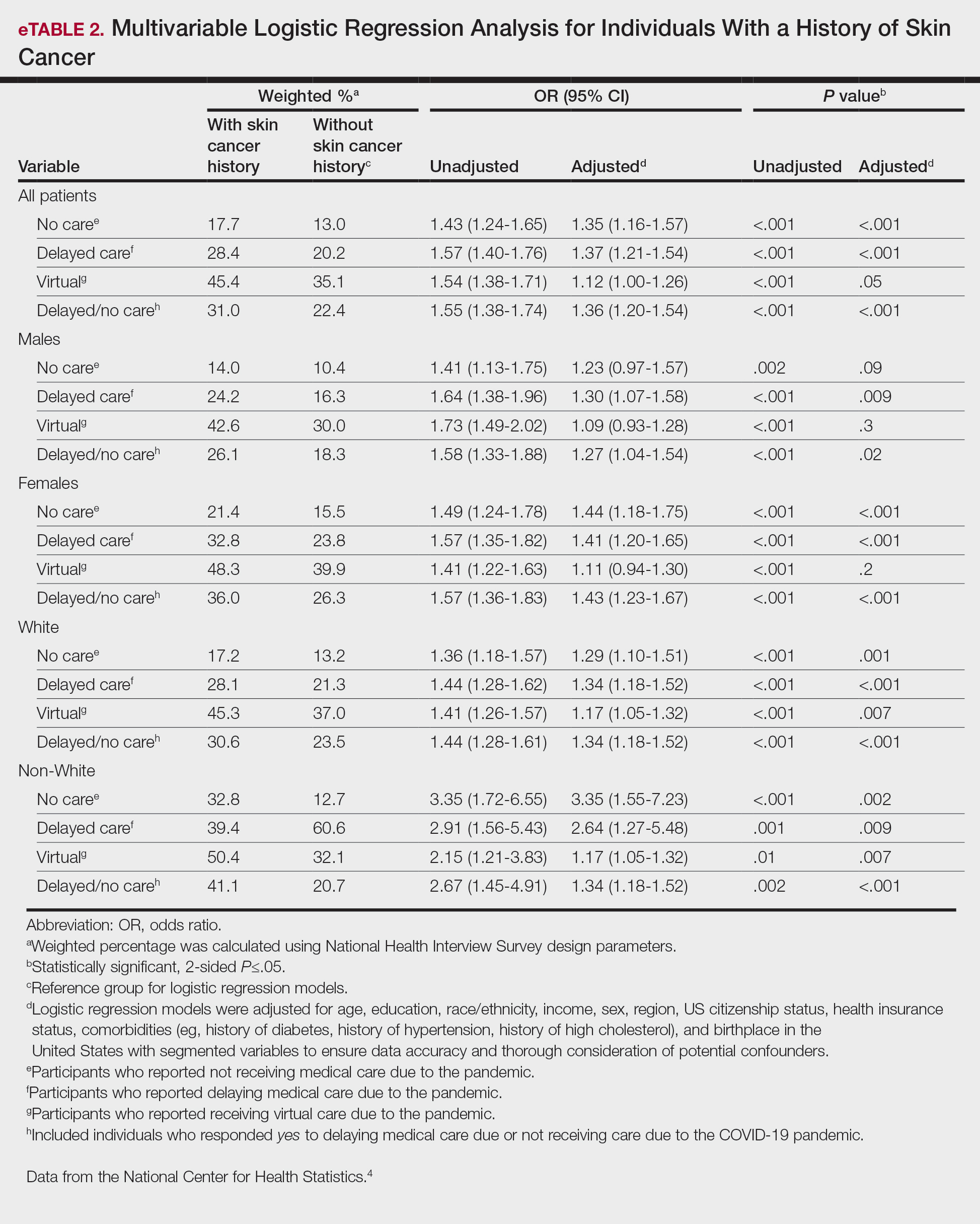

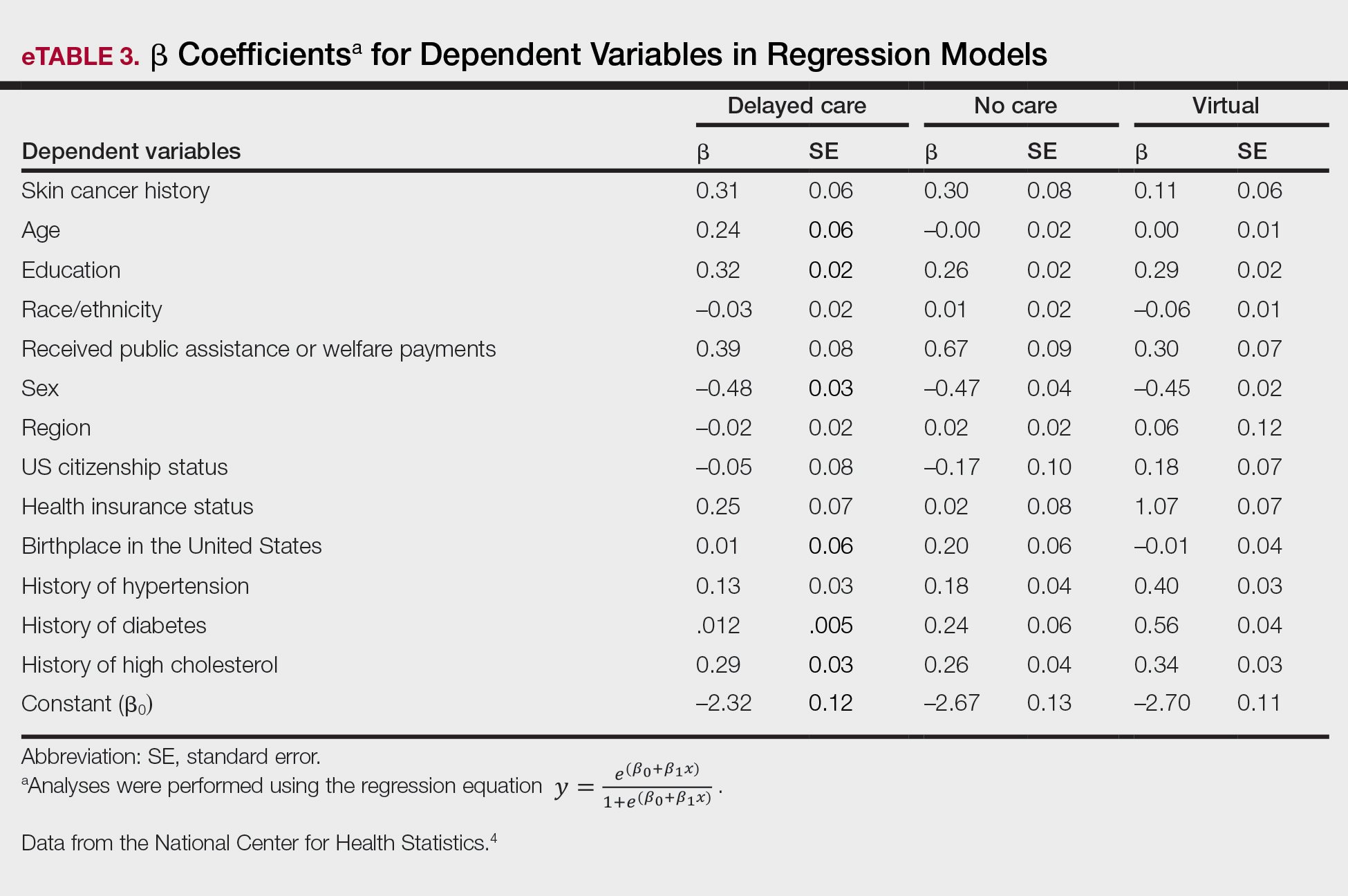

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

- Guy GP Jr, Thomas CC, Thompson T, et al. Vital signs: melanoma incidence and mortality trends and projections—United States, 1982-2030. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:591-596.

- Whiteman DC, Olsen CM, MacGregor S, et al; QSkin Study. The effect of screening on melanoma incidence and biopsy rates. Br J Dermatol. 2022;187:515-522. doi:10.1111/bjd.21649

- Jobbágy A, Kiss N, Meznerics FA, et al. Emergency use and efficacy of an asynchronous teledermatology system as a novel tool for early diagnosis of skin cancer during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:2699. doi:10.3390/ijerph19052699

- National Center for Health Statistics. NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Accessed April 19, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm

- Trepanowski N, Chang MS, Zhou G, et al. Delays in melanoma presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a nationwide multi-institutional cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:1217-1219. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.06.031

- Chiru MR, Hindocha S, Burova E, et al. Management of the two-week wait pathway for skin cancer patients, before and during the pandemic: is virtual consultation an option? J Pers Med. 2022;12:1258. doi:10.3390/jpm12081258

- Finnane A Dallest K Janda M et al. Teledermatology for the diagnosis and management of skin cancer: a systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:319-327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4361

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).

After adjusting for various potential confounders including comorbidities, our results revealed that patients with a history of skin cancer reported that they were less likely to receive in-person medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic, as high-risk individuals with a history of skin cancer may have stopped receiving total-body skin examinations and dermatology care during the pandemic. Our findings showed that patients with a history of skin cancer were more likely than those without skin cancer to delay or forego care due to the pandemic, which may contribute to a higher incidence of advanced-stage melanomas postpandemic. Trepanowski et al5 reported an increased incidence of patients presenting with more advanced melanomas during the pandemic. Telemedicine was more commonly utilized by patients with a history of skin cancer during the pandemic.

In the future, virtual care may help limit advanced stages of skin cancer by serving as a viable alternative to in-person care.6 It has been reported that telemedicine can serve as a useful triage service reducing patient wait times.7 Teledermatology should not replace in-person care, as there is no evidence of the diagnostic accuracy of this service and many patients still will need to be seen in-person for confirmation of their diagnosis and potential biopsy. Further studies are needed to assess for missed skin cancer diagnoses due to the utilization of telemedicine.

Limitations of this study included a self-reported history of skin cancer, β coefficients that may suggest a high degree of collinearity, and lack of specific survey questions regarding dermatologic care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further long-term studies exploring the clinical applicability and diagnostic accuracy of virtual medicine visits for cutaneous malignancies are vital, as teledermatology may play an essential role in curbing rising skin cancer rates even beyond the pandemic.

To the Editor:

The most common malignancy in the United States is skin cancer, with melanoma accounting for the majority of skin cancer deaths.1 Despite the lack of established guidelines for routine total-body skin examinations, many patients regularly visit their dermatologist for assessment of pigmented skin lesions.2 During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients were unable to attend in-person dermatology visits, which resulted in many high-risk individuals not receiving care or alternatively seeking virtual care for cutaneous lesions.3 There has been a lack of research in the United States exploring the utilization of teledermatology during the pandemic and its overall impact on the care of patients with a history of skin cancer. We explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on care for patients with skin cancer in a large US population.

Using anonymous survey data from the 2020-2021 National Health Interview Survey,4 we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study to evaluate access to care during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with a self-reported history of skin cancer—melanoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer, or unknown skin cancer. The 3 outcome variables included having a virtual medical appointment in the past 12 months (yes/no), delaying medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no), and not receiving care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (yes/no). Multivariable logistic regression models evaluating the relationship between a history of skin cancer and access to care were constructed using Stata/MP 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). We controlled for patient age; education; race/ethnicity; received public assistance or welfare payments; sex; region; US citizenship status; health insurance status; comorbidities including history of hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia; and birthplace in the United States in the logistic regression models.

Our analysis included 46,679 patients aged 18 years or older, of whom 3.4% (weighted)(n=2204) reported a history of skin cancer (eTable 1). The weighted percentage was calculated using National Health Interview Survey design parameters (accounting for the multistage sampling design) to represent the general US population. Compared with those with no history of skin cancer, patients with a history of skin cancer were significantly more likely to delay medical care (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.21-1.54; P<.001) or not receive care (AOR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.16-1.57; P<.001) due to the pandemic and were more likely to have had a virtual medical visit in the past 12 months (AOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.00-1.26; P=.05). Additionally, subgroup analysis revealed that females were more likely than males to forego medical care (eTable 2). β Coefficients for independent and dependent variables were further analyzed using logistic regression (eTable 3).