User login

Ductal carcinoma in situ increases risk of dying from breast cancer by threefold

Key clinical point: Women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) had a 3-fold increased risk of dying from breast cancer than women without DCIS.

Major finding: Among the cohort, 1,540 women with DCIS died of breast cancer. The expected number of deaths from breast cancer in the cancer-free cohort was 458.

Study details: Cohort study of 144,524 women diagnosed with DCIS from 1995 to 2014.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Source: Giannakeas, V, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017124. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17124

Key clinical point: Women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) had a 3-fold increased risk of dying from breast cancer than women without DCIS.

Major finding: Among the cohort, 1,540 women with DCIS died of breast cancer. The expected number of deaths from breast cancer in the cancer-free cohort was 458.

Study details: Cohort study of 144,524 women diagnosed with DCIS from 1995 to 2014.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Source: Giannakeas, V, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017124. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17124

Key clinical point: Women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) had a 3-fold increased risk of dying from breast cancer than women without DCIS.

Major finding: Among the cohort, 1,540 women with DCIS died of breast cancer. The expected number of deaths from breast cancer in the cancer-free cohort was 458.

Study details: Cohort study of 144,524 women diagnosed with DCIS from 1995 to 2014.

Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Source: Giannakeas, V, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017124. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17124

Women 70 and older are divided on age-based guidelines for breast cancer treatment

Key clinical point: In women aged 70 or older, there are skeptical views on age-based guidelines for breast cancer treatment and difficulty in interpretating the rationale for treatment de-escalation in low-risk, early-stage hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

Major finding: Approximately 40% of participants stated they would proceed with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) despite evidence that omission is safe. Conversely, 73% stated they would omit postlumpectomy radiotherapy.

Study details: A qualitative study with 30 female participants, with a median age of 72 years and without a previous diagnosis of breast cancer.

Disclosures: Dr Jagsi reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Komen Foundation, Doris Duke Foundation, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for the Michigan Radiation Oncology Quality Consortium, and Genentech; grants and personal fees from Greenwall Foundation; personal fees from Amgen, Vizient, Sherinian & Hassostock, and Dressman, Benziger, and Lavelle; and options as compensation for her advisory board role from Equity Quotient; she also reported being an uncompensated founding member of TIME’S UP Healthcare and a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board of Directors. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Wang, T, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017129. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17129

Key clinical point: In women aged 70 or older, there are skeptical views on age-based guidelines for breast cancer treatment and difficulty in interpretating the rationale for treatment de-escalation in low-risk, early-stage hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

Major finding: Approximately 40% of participants stated they would proceed with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) despite evidence that omission is safe. Conversely, 73% stated they would omit postlumpectomy radiotherapy.

Study details: A qualitative study with 30 female participants, with a median age of 72 years and without a previous diagnosis of breast cancer.

Disclosures: Dr Jagsi reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Komen Foundation, Doris Duke Foundation, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for the Michigan Radiation Oncology Quality Consortium, and Genentech; grants and personal fees from Greenwall Foundation; personal fees from Amgen, Vizient, Sherinian & Hassostock, and Dressman, Benziger, and Lavelle; and options as compensation for her advisory board role from Equity Quotient; she also reported being an uncompensated founding member of TIME’S UP Healthcare and a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board of Directors. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Wang, T, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017129. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17129

Key clinical point: In women aged 70 or older, there are skeptical views on age-based guidelines for breast cancer treatment and difficulty in interpretating the rationale for treatment de-escalation in low-risk, early-stage hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

Major finding: Approximately 40% of participants stated they would proceed with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) despite evidence that omission is safe. Conversely, 73% stated they would omit postlumpectomy radiotherapy.

Study details: A qualitative study with 30 female participants, with a median age of 72 years and without a previous diagnosis of breast cancer.

Disclosures: Dr Jagsi reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Komen Foundation, Doris Duke Foundation, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan for the Michigan Radiation Oncology Quality Consortium, and Genentech; grants and personal fees from Greenwall Foundation; personal fees from Amgen, Vizient, Sherinian & Hassostock, and Dressman, Benziger, and Lavelle; and options as compensation for her advisory board role from Equity Quotient; she also reported being an uncompensated founding member of TIME’S UP Healthcare and a member of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board of Directors. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Wang, T, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017129. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17129

Beyond baseline, DBT no better than mammography for dense breasts

Key clinical point: In women with extremely dense breasts, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) does not outperform digital mammography (DM) after the initial exam.

Major finding: For baseline screening in women aged 50-59 years, recall rates per 1,000 exams dropped from 241 with DM to 204 with DBT. Cancer detection rates per 1,000 exams in this age group increased from 5.9 with DM to 8.8 with DBT. On follow-up exams, recall and cancer detection rates varied by patients’ age and breast density.

Study details: Review of 1,584,079 screenings in women aged 40-79 years.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute through the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The study lead reported grants from GE Healthcare.

Source: Lowry K et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7):e2011792.

Key clinical point: In women with extremely dense breasts, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) does not outperform digital mammography (DM) after the initial exam.

Major finding: For baseline screening in women aged 50-59 years, recall rates per 1,000 exams dropped from 241 with DM to 204 with DBT. Cancer detection rates per 1,000 exams in this age group increased from 5.9 with DM to 8.8 with DBT. On follow-up exams, recall and cancer detection rates varied by patients’ age and breast density.

Study details: Review of 1,584,079 screenings in women aged 40-79 years.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute through the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The study lead reported grants from GE Healthcare.

Source: Lowry K et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7):e2011792.

Key clinical point: In women with extremely dense breasts, digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT) does not outperform digital mammography (DM) after the initial exam.

Major finding: For baseline screening in women aged 50-59 years, recall rates per 1,000 exams dropped from 241 with DM to 204 with DBT. Cancer detection rates per 1,000 exams in this age group increased from 5.9 with DM to 8.8 with DBT. On follow-up exams, recall and cancer detection rates varied by patients’ age and breast density.

Study details: Review of 1,584,079 screenings in women aged 40-79 years.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute through the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. The study lead reported grants from GE Healthcare.

Source: Lowry K et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jul 1;3(7):e2011792.

Study supports multigene panel testing for all breast cancer patients with second primary cancers

Key clinical point: All patients with breast cancer who develop a second primary cancer should undergo multigene panel testing, according to researchers.

Major finding: Mutation rates in BRCA1/2-negative breast cancer patients with multiple primary cancers were approximately 7% to 9%, compared with about 4% to 5% in BRCA1/2-negative patients with a single breast cancer.

Study details: A comparison of mutation rates in 1,000 high-risk breast cancer patients (551 with multiple primary cancers and 449 with a single breast cancer) and 1,804 familial breast cancer patients (340 with multiple primaries and 1,464 with a single breast cancer).

Disclosures: This research was supported by grants from government agencies and foundations as well as the University of Pennsylvania. Some authors disclosed relationships with a range of companies.

Source: Maxwell KN et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00301.

Key clinical point: All patients with breast cancer who develop a second primary cancer should undergo multigene panel testing, according to researchers.

Major finding: Mutation rates in BRCA1/2-negative breast cancer patients with multiple primary cancers were approximately 7% to 9%, compared with about 4% to 5% in BRCA1/2-negative patients with a single breast cancer.

Study details: A comparison of mutation rates in 1,000 high-risk breast cancer patients (551 with multiple primary cancers and 449 with a single breast cancer) and 1,804 familial breast cancer patients (340 with multiple primaries and 1,464 with a single breast cancer).

Disclosures: This research was supported by grants from government agencies and foundations as well as the University of Pennsylvania. Some authors disclosed relationships with a range of companies.

Source: Maxwell KN et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00301.

Key clinical point: All patients with breast cancer who develop a second primary cancer should undergo multigene panel testing, according to researchers.

Major finding: Mutation rates in BRCA1/2-negative breast cancer patients with multiple primary cancers were approximately 7% to 9%, compared with about 4% to 5% in BRCA1/2-negative patients with a single breast cancer.

Study details: A comparison of mutation rates in 1,000 high-risk breast cancer patients (551 with multiple primary cancers and 449 with a single breast cancer) and 1,804 familial breast cancer patients (340 with multiple primaries and 1,464 with a single breast cancer).

Disclosures: This research was supported by grants from government agencies and foundations as well as the University of Pennsylvania. Some authors disclosed relationships with a range of companies.

Source: Maxwell KN et al. JCO Precis Oncol. 2020. doi: 10.1200/PO.19.00301.

AI algorithm on par with radiologists as mammogram reader

Key clinical point: An artificial intelligence computer algorithm performed on par with, and in some cases exceeded, radiologists in reading mammograms from women undergoing routine screening.

Major finding: When operating at a specificity of 96.6%, the sensitivity was 81.9% for the algorithm, 77.4% for first-reader radiologists, and 80.1% for second-reader radiologists.

Study details: A comparison of algorithm and radiologist assessments of mammograms in 8,805 women, 739 of whom were diagnosed with breast cancer.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Stockholm County Council. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, Stockholm City Council, Collective Minds Radiology, and Pfizer.

Source: Salim M et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3321.

Key clinical point: An artificial intelligence computer algorithm performed on par with, and in some cases exceeded, radiologists in reading mammograms from women undergoing routine screening.

Major finding: When operating at a specificity of 96.6%, the sensitivity was 81.9% for the algorithm, 77.4% for first-reader radiologists, and 80.1% for second-reader radiologists.

Study details: A comparison of algorithm and radiologist assessments of mammograms in 8,805 women, 739 of whom were diagnosed with breast cancer.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Stockholm County Council. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, Stockholm City Council, Collective Minds Radiology, and Pfizer.

Source: Salim M et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3321.

Key clinical point: An artificial intelligence computer algorithm performed on par with, and in some cases exceeded, radiologists in reading mammograms from women undergoing routine screening.

Major finding: When operating at a specificity of 96.6%, the sensitivity was 81.9% for the algorithm, 77.4% for first-reader radiologists, and 80.1% for second-reader radiologists.

Study details: A comparison of algorithm and radiologist assessments of mammograms in 8,805 women, 739 of whom were diagnosed with breast cancer.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Stockholm County Council. The investigators disclosed financial relationships with the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, Stockholm City Council, Collective Minds Radiology, and Pfizer.

Source: Salim M et al. JAMA Oncol. 2020 Aug 27. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3321.

Older adults with multiple myeloma face heavy burden of care

A substantial cumulative burden of treatment in the first year is borne by patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM), according to a report published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

MM is a disease of aging, with a median age at diagnosis of 69 years, and the burden of treatment and not just possible outcomes should be considered in decision-making discussions with patients, according to researchers Hira S. Mian, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues.

They performed a retrospective study of a Medicare-linked database of 3,065 adults newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM) between 2007-2013. The treatment burden among the patients was assessed to determine those factors associated with high treatment burden.

Heavy burden

Treatment burden was defined as the number of total days with a health care encounter (including acute care and outpatient visits), oncology and nononcology physician visits, and the number of new prescriptions within the first year following diagnosis, according to the researchers.

The study found that there was a substantial burden of treatment, including a median of more than 2 months of cumulative interactions with health care, within the first year following diagnosis. This burden was highest during the first 3 months.

Those patients who had multiple comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.27 per 1-point increase in Charlson comorbidity index, P < .001), poor performance status (aOR 1.85, P < .001), myeloma-related end-organ damage, especially bone disease (aOR 2.28, P < .001), and those who received autologous stem cell transplant (aOR 2.41, P < .001) were more likely to have a higher treatment burden, they reported.

“Decision-making regarding treatment modalities should not just emphasize traditional parameters such as response rates and progression-free survival but should also include a discussion regarding the workload burden placed on the patient and the care partner, in order to ensure informed and patient-centered decision-making is prioritized. This may be particularly relevant among certain subgroups such as older patients with cancer who may prioritize quality of life over aggressive disease control and overall survival,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The authors reported funding from a variety of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Mian HS et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Oct 1. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.09.010.

A substantial cumulative burden of treatment in the first year is borne by patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM), according to a report published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

MM is a disease of aging, with a median age at diagnosis of 69 years, and the burden of treatment and not just possible outcomes should be considered in decision-making discussions with patients, according to researchers Hira S. Mian, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues.

They performed a retrospective study of a Medicare-linked database of 3,065 adults newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM) between 2007-2013. The treatment burden among the patients was assessed to determine those factors associated with high treatment burden.

Heavy burden

Treatment burden was defined as the number of total days with a health care encounter (including acute care and outpatient visits), oncology and nononcology physician visits, and the number of new prescriptions within the first year following diagnosis, according to the researchers.

The study found that there was a substantial burden of treatment, including a median of more than 2 months of cumulative interactions with health care, within the first year following diagnosis. This burden was highest during the first 3 months.

Those patients who had multiple comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.27 per 1-point increase in Charlson comorbidity index, P < .001), poor performance status (aOR 1.85, P < .001), myeloma-related end-organ damage, especially bone disease (aOR 2.28, P < .001), and those who received autologous stem cell transplant (aOR 2.41, P < .001) were more likely to have a higher treatment burden, they reported.

“Decision-making regarding treatment modalities should not just emphasize traditional parameters such as response rates and progression-free survival but should also include a discussion regarding the workload burden placed on the patient and the care partner, in order to ensure informed and patient-centered decision-making is prioritized. This may be particularly relevant among certain subgroups such as older patients with cancer who may prioritize quality of life over aggressive disease control and overall survival,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The authors reported funding from a variety of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Mian HS et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Oct 1. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.09.010.

A substantial cumulative burden of treatment in the first year is borne by patients newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM), according to a report published online in Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia.

MM is a disease of aging, with a median age at diagnosis of 69 years, and the burden of treatment and not just possible outcomes should be considered in decision-making discussions with patients, according to researchers Hira S. Mian, MD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., and colleagues.

They performed a retrospective study of a Medicare-linked database of 3,065 adults newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM) between 2007-2013. The treatment burden among the patients was assessed to determine those factors associated with high treatment burden.

Heavy burden

Treatment burden was defined as the number of total days with a health care encounter (including acute care and outpatient visits), oncology and nononcology physician visits, and the number of new prescriptions within the first year following diagnosis, according to the researchers.

The study found that there was a substantial burden of treatment, including a median of more than 2 months of cumulative interactions with health care, within the first year following diagnosis. This burden was highest during the first 3 months.

Those patients who had multiple comorbidities (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 1.27 per 1-point increase in Charlson comorbidity index, P < .001), poor performance status (aOR 1.85, P < .001), myeloma-related end-organ damage, especially bone disease (aOR 2.28, P < .001), and those who received autologous stem cell transplant (aOR 2.41, P < .001) were more likely to have a higher treatment burden, they reported.

“Decision-making regarding treatment modalities should not just emphasize traditional parameters such as response rates and progression-free survival but should also include a discussion regarding the workload burden placed on the patient and the care partner, in order to ensure informed and patient-centered decision-making is prioritized. This may be particularly relevant among certain subgroups such as older patients with cancer who may prioritize quality of life over aggressive disease control and overall survival,” the researchers concluded.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The authors reported funding from a variety of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies.

SOURCE: Mian HS et al. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2020 Oct 1. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2020.09.010.

FROM CLINICAL LYMPHOMA, MYELOMA AND LEUKEMIA

Review finds mortality rates low in young pregnant women with SJS, TEN

Investigators who but higher rates of C-sections.

The systematic review found that early diagnosis and withdrawal of the causative medications, such as antiretrovirals, were beneficial.

While SJS and TEN have been reported in pregnant women, “the outcomes and treatment of these cases are poorly characterized in the literature,” noted Ajay N. Sharma, a medical student at the University of California, Irvine, and coauthors, who published their findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

“Immune changes that occur during pregnancy create a relative state of immunosuppression, likely increasing the risk of these skin reactions,” Mr. Sharma said in an interview. Allopurinol, antiepileptic drugs, antibacterial sulfonamides, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs are agents most often associated with SJS/TEN.

He and his coauthors conducted a systematic literature review to analyze the risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of SJS and TEN in pregnant patients and their newborns using PubMed and Cochrane data from September 2019. The review included 26 articles covering 177 pregnant patients with SJS or TEN. Affected women were fairly young, averaging 29.9 years of age and more than 24 weeks along in their pregnancy when they experienced a reaction.

The majority of cases (81.9%) involved SJS diagnoses. Investigators identified antiretroviral therapy (90% of all cases), antibiotics (3%), and gestational drugs (2%) as the most common causative agents. “Multiple large cohort studies included in our review specifically assessed outcomes in only pregnant patients with HIV, resulting in an overall distribution of offending medications biased toward antiretroviral therapy,” noted Mr. Sharma. Nevirapine, a staple antiretroviral in developing countries (the site of most studies in the review), emerged as the biggest causal agent linked to 75 cases; 1 case was linked to the antiretroviral drug efavirenz.

Approximately 85% of pregnant women in this review had HIV. However, the young patient population studied had few comorbidities and low transmission rates to the fetus. In the 94 cases where outcomes data were available, 98% of the mothers and 96% of the newborns survived. Two pregnant patients in this cohort died, one from septic shock secondary to a TEN superinfection, and the other from intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic melanoma. Of the 94 fetuses, 4 died: 2 of sepsis after birth, 1 in utero with its mother, and there was 1 stillbirth.

“Withdrawal of the offending drug was enacted in every recorded case of SJS or TEN during pregnancy. This single intervention was adequate in 159 patients; no additional therapy was needed in these cases aside from standard wound care, fluid and electrolyte repletion, and pain control,” wrote the investigators. Clinicians administered antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin in patients needing further assistance.

The investigators also reported high rates of C-section – almost 50% – in this group of pregnant women.

Inconsistent reporting between studies limited results, Mr. Sharma and colleagues noted. “Not every report specified body surface area involvement, treatment regimen, maternal or fetal outcome, or delivery method. Although additional studies in the form of large-scale, randomized, clinical trials are needed to better delineate treatment, this systematic review provides a framework for managing this population.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding for the study.

SOURCE: Sharma AN et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 Apr 13;6(4):239-47.

Investigators who but higher rates of C-sections.

The systematic review found that early diagnosis and withdrawal of the causative medications, such as antiretrovirals, were beneficial.

While SJS and TEN have been reported in pregnant women, “the outcomes and treatment of these cases are poorly characterized in the literature,” noted Ajay N. Sharma, a medical student at the University of California, Irvine, and coauthors, who published their findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

“Immune changes that occur during pregnancy create a relative state of immunosuppression, likely increasing the risk of these skin reactions,” Mr. Sharma said in an interview. Allopurinol, antiepileptic drugs, antibacterial sulfonamides, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs are agents most often associated with SJS/TEN.

He and his coauthors conducted a systematic literature review to analyze the risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of SJS and TEN in pregnant patients and their newborns using PubMed and Cochrane data from September 2019. The review included 26 articles covering 177 pregnant patients with SJS or TEN. Affected women were fairly young, averaging 29.9 years of age and more than 24 weeks along in their pregnancy when they experienced a reaction.

The majority of cases (81.9%) involved SJS diagnoses. Investigators identified antiretroviral therapy (90% of all cases), antibiotics (3%), and gestational drugs (2%) as the most common causative agents. “Multiple large cohort studies included in our review specifically assessed outcomes in only pregnant patients with HIV, resulting in an overall distribution of offending medications biased toward antiretroviral therapy,” noted Mr. Sharma. Nevirapine, a staple antiretroviral in developing countries (the site of most studies in the review), emerged as the biggest causal agent linked to 75 cases; 1 case was linked to the antiretroviral drug efavirenz.

Approximately 85% of pregnant women in this review had HIV. However, the young patient population studied had few comorbidities and low transmission rates to the fetus. In the 94 cases where outcomes data were available, 98% of the mothers and 96% of the newborns survived. Two pregnant patients in this cohort died, one from septic shock secondary to a TEN superinfection, and the other from intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic melanoma. Of the 94 fetuses, 4 died: 2 of sepsis after birth, 1 in utero with its mother, and there was 1 stillbirth.

“Withdrawal of the offending drug was enacted in every recorded case of SJS or TEN during pregnancy. This single intervention was adequate in 159 patients; no additional therapy was needed in these cases aside from standard wound care, fluid and electrolyte repletion, and pain control,” wrote the investigators. Clinicians administered antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin in patients needing further assistance.

The investigators also reported high rates of C-section – almost 50% – in this group of pregnant women.

Inconsistent reporting between studies limited results, Mr. Sharma and colleagues noted. “Not every report specified body surface area involvement, treatment regimen, maternal or fetal outcome, or delivery method. Although additional studies in the form of large-scale, randomized, clinical trials are needed to better delineate treatment, this systematic review provides a framework for managing this population.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding for the study.

SOURCE: Sharma AN et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 Apr 13;6(4):239-47.

Investigators who but higher rates of C-sections.

The systematic review found that early diagnosis and withdrawal of the causative medications, such as antiretrovirals, were beneficial.

While SJS and TEN have been reported in pregnant women, “the outcomes and treatment of these cases are poorly characterized in the literature,” noted Ajay N. Sharma, a medical student at the University of California, Irvine, and coauthors, who published their findings in the International Journal of Women’s Dermatology.

“Immune changes that occur during pregnancy create a relative state of immunosuppression, likely increasing the risk of these skin reactions,” Mr. Sharma said in an interview. Allopurinol, antiepileptic drugs, antibacterial sulfonamides, nevirapine, and oxicam NSAIDs are agents most often associated with SJS/TEN.

He and his coauthors conducted a systematic literature review to analyze the risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of SJS and TEN in pregnant patients and their newborns using PubMed and Cochrane data from September 2019. The review included 26 articles covering 177 pregnant patients with SJS or TEN. Affected women were fairly young, averaging 29.9 years of age and more than 24 weeks along in their pregnancy when they experienced a reaction.

The majority of cases (81.9%) involved SJS diagnoses. Investigators identified antiretroviral therapy (90% of all cases), antibiotics (3%), and gestational drugs (2%) as the most common causative agents. “Multiple large cohort studies included in our review specifically assessed outcomes in only pregnant patients with HIV, resulting in an overall distribution of offending medications biased toward antiretroviral therapy,” noted Mr. Sharma. Nevirapine, a staple antiretroviral in developing countries (the site of most studies in the review), emerged as the biggest causal agent linked to 75 cases; 1 case was linked to the antiretroviral drug efavirenz.

Approximately 85% of pregnant women in this review had HIV. However, the young patient population studied had few comorbidities and low transmission rates to the fetus. In the 94 cases where outcomes data were available, 98% of the mothers and 96% of the newborns survived. Two pregnant patients in this cohort died, one from septic shock secondary to a TEN superinfection, and the other from intracranial hemorrhage secondary to metastatic melanoma. Of the 94 fetuses, 4 died: 2 of sepsis after birth, 1 in utero with its mother, and there was 1 stillbirth.

“Withdrawal of the offending drug was enacted in every recorded case of SJS or TEN during pregnancy. This single intervention was adequate in 159 patients; no additional therapy was needed in these cases aside from standard wound care, fluid and electrolyte repletion, and pain control,” wrote the investigators. Clinicians administered antibiotics, fluid resuscitation, steroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin in patients needing further assistance.

The investigators also reported high rates of C-section – almost 50% – in this group of pregnant women.

Inconsistent reporting between studies limited results, Mr. Sharma and colleagues noted. “Not every report specified body surface area involvement, treatment regimen, maternal or fetal outcome, or delivery method. Although additional studies in the form of large-scale, randomized, clinical trials are needed to better delineate treatment, this systematic review provides a framework for managing this population.”

The study authors reported no conflicts of interest and no funding for the study.

SOURCE: Sharma AN et al. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2020 Apr 13;6(4):239-47.

FROM THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S DERMATOLOGY

Teen affective disorders raise risk for midlife acute MI

in a Swedish national registry study presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The association was mediated in part by poor stress resilience and lack of physical fitness among these teenagers with an affective disorder, reported Cecilia Bergh, PhD, of Obrero (Sweden) University.

Her study was made possible by Sweden’s comprehensive national health care registries coupled with the Nordic nation’s compulsory conscription for military service. The mandatory conscription evaluation during the study years included a semistructured interview with a psychologist to assess stress resilience through questions about coping with everyday life, a medical history and physical examination, and a cardiovascular fitness test using a bicycle ergometer.

The study included 238,013 males born in 1952-1956. They were aged 18-19 years when they underwent their conscription examination, at which time 34,503 of them either received or already had a diagnosis of depression or anxiety. During follow-up from 1987 to 2010, a first acute MI occurred in 5,891 of the men. The risk was increased 51% among those with an earlier teen diagnosis of depression or anxiety.

In a Cox regression analysis adjusted for levels of adolescent cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure, body mass index, and systemic inflammation, as well as additional potential confounders, such as cognitive function, parental socioeconomic index, and a summary disease score, the midlife MI risk associated with adolescent depression or anxiety was attenuated, but still significant, with a 24% increase. Upon further statistical adjustment incorporating adolescent stress resilience and cardiovascular fitness, the increased risk of acute MI in midlife associated with adolescent depression or anxiety was further attenuated yet remained significant, at 18%.

Dr. Bergh shared her thoughts on preventing this increased risk of acute MI at a relatively young age: “Effective prevention might focus on behavior, lifestyle, and psychosocial stress in early life. If a healthy lifestyle is encouraged as early as possible in childhood and adolescence, it is more likely to persist into adulthood and to improve longterm health. So look for signs of stress, depression, or anxiety that is beyond normal teenager behavior and a persistent problem. Teenagers with poor well-being could benefit from additional support to encourage exercise and also to develop strategies to deal with stress.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Bergh C et al. ESC 2020, Abstract 90524.

in a Swedish national registry study presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The association was mediated in part by poor stress resilience and lack of physical fitness among these teenagers with an affective disorder, reported Cecilia Bergh, PhD, of Obrero (Sweden) University.

Her study was made possible by Sweden’s comprehensive national health care registries coupled with the Nordic nation’s compulsory conscription for military service. The mandatory conscription evaluation during the study years included a semistructured interview with a psychologist to assess stress resilience through questions about coping with everyday life, a medical history and physical examination, and a cardiovascular fitness test using a bicycle ergometer.

The study included 238,013 males born in 1952-1956. They were aged 18-19 years when they underwent their conscription examination, at which time 34,503 of them either received or already had a diagnosis of depression or anxiety. During follow-up from 1987 to 2010, a first acute MI occurred in 5,891 of the men. The risk was increased 51% among those with an earlier teen diagnosis of depression or anxiety.

In a Cox regression analysis adjusted for levels of adolescent cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure, body mass index, and systemic inflammation, as well as additional potential confounders, such as cognitive function, parental socioeconomic index, and a summary disease score, the midlife MI risk associated with adolescent depression or anxiety was attenuated, but still significant, with a 24% increase. Upon further statistical adjustment incorporating adolescent stress resilience and cardiovascular fitness, the increased risk of acute MI in midlife associated with adolescent depression or anxiety was further attenuated yet remained significant, at 18%.

Dr. Bergh shared her thoughts on preventing this increased risk of acute MI at a relatively young age: “Effective prevention might focus on behavior, lifestyle, and psychosocial stress in early life. If a healthy lifestyle is encouraged as early as possible in childhood and adolescence, it is more likely to persist into adulthood and to improve longterm health. So look for signs of stress, depression, or anxiety that is beyond normal teenager behavior and a persistent problem. Teenagers with poor well-being could benefit from additional support to encourage exercise and also to develop strategies to deal with stress.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Bergh C et al. ESC 2020, Abstract 90524.

in a Swedish national registry study presented at the virtual annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

The association was mediated in part by poor stress resilience and lack of physical fitness among these teenagers with an affective disorder, reported Cecilia Bergh, PhD, of Obrero (Sweden) University.

Her study was made possible by Sweden’s comprehensive national health care registries coupled with the Nordic nation’s compulsory conscription for military service. The mandatory conscription evaluation during the study years included a semistructured interview with a psychologist to assess stress resilience through questions about coping with everyday life, a medical history and physical examination, and a cardiovascular fitness test using a bicycle ergometer.

The study included 238,013 males born in 1952-1956. They were aged 18-19 years when they underwent their conscription examination, at which time 34,503 of them either received or already had a diagnosis of depression or anxiety. During follow-up from 1987 to 2010, a first acute MI occurred in 5,891 of the men. The risk was increased 51% among those with an earlier teen diagnosis of depression or anxiety.

In a Cox regression analysis adjusted for levels of adolescent cardiovascular risk factors, including blood pressure, body mass index, and systemic inflammation, as well as additional potential confounders, such as cognitive function, parental socioeconomic index, and a summary disease score, the midlife MI risk associated with adolescent depression or anxiety was attenuated, but still significant, with a 24% increase. Upon further statistical adjustment incorporating adolescent stress resilience and cardiovascular fitness, the increased risk of acute MI in midlife associated with adolescent depression or anxiety was further attenuated yet remained significant, at 18%.

Dr. Bergh shared her thoughts on preventing this increased risk of acute MI at a relatively young age: “Effective prevention might focus on behavior, lifestyle, and psychosocial stress in early life. If a healthy lifestyle is encouraged as early as possible in childhood and adolescence, it is more likely to persist into adulthood and to improve longterm health. So look for signs of stress, depression, or anxiety that is beyond normal teenager behavior and a persistent problem. Teenagers with poor well-being could benefit from additional support to encourage exercise and also to develop strategies to deal with stress.”

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, conducted free of commercial support.

SOURCE: Bergh C et al. ESC 2020, Abstract 90524.

FROM ESC CONGRESS 2020

A possible benchmark for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance

A population-based cohort analysis of Barrett’s esophagus patients undergoing surveillance endoscopy suggests that the neoplasia detection rate (NDR) and the rate of missed dysplasia during the index endoscopy may be lower than previously reported in studies of referral-based cohorts. The new results suggest that NDR may be a useful quality control measure for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance.

The finding is welcome. “Just like we’ve done in colonoscopy with the adenoma detection rate, we need to have a quality metric to determine whether or not we’re adequately finding neoplasia while screening our patients with Barrett’s esophagus,” Jeffrey Mosko, MD, a gastroenterologist and interventional endoscopist at the University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital, said in an interview.

Societal guidelines recommend endoscopic screening in Barrett’s esophagus patients, with the goal of identifying dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and eradicating it endoscopically before it can develop into esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Despite this, 90% of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma are diagnosed outside of a surveillance program.

Missed high-grade dysplasia or early EAC could become more invasive or metastasize, potentially leading to greater morbidity, mortality, and cost, although that relationship hasn’t been absolutely established yet the way it has with colonoscopy and colorectal cancer, according to Dr. Mosko.

Variation in endoscopy performance can be caused by the patchy and subtle appearance of dysplasia, and because procedural guidelines are not always closely followed. There is often a significant difference between procedures performed by specialists and nonspecialists. “Endoscopists in general don’t take enough time to examine the segment, they don’t wash appropriately, and when they do look, they may not be well enough trained to know what they’re looking at. The only way to improve on this aside from additional training is to have a metric that measures how you’re doing, and I think [the neoplasia detection rate] is as close as we get to doing that. I think the exact threshold for NDR is not as important as figuring out what your number is and then ways to improve it,” said Dr. Mosko.

A recent meta-analysis estimated NDR to be 7%, but the patient cohort used was derived from referrals to academic centers, where experienced gastroenterologists may register a higher than average NDR. The study also lacked data on patients, providers, or biopsy quality, which prevented assessment of the effects of NDR on subsequent missed dysplasia or predictors of high or low NDR.

To get a better estimate of NDR, researchers led by Lovekirat Dhaliwal, MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., analyzed data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, including patients from 11 counties in Minnesota. They identified 1,066 patients with Barrett’s esophagus, 71.1% of whom were male, with a mean age of 63 years. 77% had surveillance endoscopies performed by gastroenterologists, the remainder by nongastroenterologists such as doctors, surgeons, or internal medicine physicians. About 60% of participants received adequate biopsies per Seattle protocol.

The NDR was 4.9% (95% CI, 3.8%-6.4%), including 3.1% high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and 1.8% EAC. One-quarter of EAC cases had metastatic lymphadenopathy at endoscopy or surgery, and 10.6% had low-grade dysplasia (LGD). Although high-definition monitors and high-resolution endoscopes were added to practices, particularly after 2000, the researchers found no evidence of increasing NDR over time on multivariate analysis. In a separate analysis of targeted biopsies in 54 patients with a visible lesion, 9 had LGD (7.96% of all LGD diagnoses) and 10 had EAC (50.0% of all EAC diagnoses). Visible lesions were more often reported by gastroenterologists than nongastroenterologists (odds ratio, 3.7; P = .0120). Gastroenterologists had a higher rate of NDR on univariate analysis (5.8% vs. 1.7%; P = .0098).

There were 391 Barrett’s esophagus patients with no diagnosis of HGD or EAC at the initial endoscopy underwent another endoscopy at 12 months. At the follow-up procedure, eight patients were found to have HGD/EAC, amounting to 13% of HGD/EAC cases being missed at the index endoscopy. There was no statistically significant association between a missed dysplasia or found dysplasia and segment length (4.7 cm vs. 3.7 cm; P = .4), Seattle protocol adherence (62% vs. 58.7%; P = .8), visibility of lesions (OR, 0.6; P = .55), age, smoking history, or practitioner specialty.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Mosko has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dhaliwal L et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.034.

A population-based cohort analysis of Barrett’s esophagus patients undergoing surveillance endoscopy suggests that the neoplasia detection rate (NDR) and the rate of missed dysplasia during the index endoscopy may be lower than previously reported in studies of referral-based cohorts. The new results suggest that NDR may be a useful quality control measure for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance.

The finding is welcome. “Just like we’ve done in colonoscopy with the adenoma detection rate, we need to have a quality metric to determine whether or not we’re adequately finding neoplasia while screening our patients with Barrett’s esophagus,” Jeffrey Mosko, MD, a gastroenterologist and interventional endoscopist at the University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital, said in an interview.

Societal guidelines recommend endoscopic screening in Barrett’s esophagus patients, with the goal of identifying dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and eradicating it endoscopically before it can develop into esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Despite this, 90% of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma are diagnosed outside of a surveillance program.

Missed high-grade dysplasia or early EAC could become more invasive or metastasize, potentially leading to greater morbidity, mortality, and cost, although that relationship hasn’t been absolutely established yet the way it has with colonoscopy and colorectal cancer, according to Dr. Mosko.

Variation in endoscopy performance can be caused by the patchy and subtle appearance of dysplasia, and because procedural guidelines are not always closely followed. There is often a significant difference between procedures performed by specialists and nonspecialists. “Endoscopists in general don’t take enough time to examine the segment, they don’t wash appropriately, and when they do look, they may not be well enough trained to know what they’re looking at. The only way to improve on this aside from additional training is to have a metric that measures how you’re doing, and I think [the neoplasia detection rate] is as close as we get to doing that. I think the exact threshold for NDR is not as important as figuring out what your number is and then ways to improve it,” said Dr. Mosko.

A recent meta-analysis estimated NDR to be 7%, but the patient cohort used was derived from referrals to academic centers, where experienced gastroenterologists may register a higher than average NDR. The study also lacked data on patients, providers, or biopsy quality, which prevented assessment of the effects of NDR on subsequent missed dysplasia or predictors of high or low NDR.

To get a better estimate of NDR, researchers led by Lovekirat Dhaliwal, MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., analyzed data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, including patients from 11 counties in Minnesota. They identified 1,066 patients with Barrett’s esophagus, 71.1% of whom were male, with a mean age of 63 years. 77% had surveillance endoscopies performed by gastroenterologists, the remainder by nongastroenterologists such as doctors, surgeons, or internal medicine physicians. About 60% of participants received adequate biopsies per Seattle protocol.

The NDR was 4.9% (95% CI, 3.8%-6.4%), including 3.1% high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and 1.8% EAC. One-quarter of EAC cases had metastatic lymphadenopathy at endoscopy or surgery, and 10.6% had low-grade dysplasia (LGD). Although high-definition monitors and high-resolution endoscopes were added to practices, particularly after 2000, the researchers found no evidence of increasing NDR over time on multivariate analysis. In a separate analysis of targeted biopsies in 54 patients with a visible lesion, 9 had LGD (7.96% of all LGD diagnoses) and 10 had EAC (50.0% of all EAC diagnoses). Visible lesions were more often reported by gastroenterologists than nongastroenterologists (odds ratio, 3.7; P = .0120). Gastroenterologists had a higher rate of NDR on univariate analysis (5.8% vs. 1.7%; P = .0098).

There were 391 Barrett’s esophagus patients with no diagnosis of HGD or EAC at the initial endoscopy underwent another endoscopy at 12 months. At the follow-up procedure, eight patients were found to have HGD/EAC, amounting to 13% of HGD/EAC cases being missed at the index endoscopy. There was no statistically significant association between a missed dysplasia or found dysplasia and segment length (4.7 cm vs. 3.7 cm; P = .4), Seattle protocol adherence (62% vs. 58.7%; P = .8), visibility of lesions (OR, 0.6; P = .55), age, smoking history, or practitioner specialty.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Mosko has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dhaliwal L et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.034.

A population-based cohort analysis of Barrett’s esophagus patients undergoing surveillance endoscopy suggests that the neoplasia detection rate (NDR) and the rate of missed dysplasia during the index endoscopy may be lower than previously reported in studies of referral-based cohorts. The new results suggest that NDR may be a useful quality control measure for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance.

The finding is welcome. “Just like we’ve done in colonoscopy with the adenoma detection rate, we need to have a quality metric to determine whether or not we’re adequately finding neoplasia while screening our patients with Barrett’s esophagus,” Jeffrey Mosko, MD, a gastroenterologist and interventional endoscopist at the University of Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital, said in an interview.

Societal guidelines recommend endoscopic screening in Barrett’s esophagus patients, with the goal of identifying dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and eradicating it endoscopically before it can develop into esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Despite this, 90% of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma are diagnosed outside of a surveillance program.

Missed high-grade dysplasia or early EAC could become more invasive or metastasize, potentially leading to greater morbidity, mortality, and cost, although that relationship hasn’t been absolutely established yet the way it has with colonoscopy and colorectal cancer, according to Dr. Mosko.

Variation in endoscopy performance can be caused by the patchy and subtle appearance of dysplasia, and because procedural guidelines are not always closely followed. There is often a significant difference between procedures performed by specialists and nonspecialists. “Endoscopists in general don’t take enough time to examine the segment, they don’t wash appropriately, and when they do look, they may not be well enough trained to know what they’re looking at. The only way to improve on this aside from additional training is to have a metric that measures how you’re doing, and I think [the neoplasia detection rate] is as close as we get to doing that. I think the exact threshold for NDR is not as important as figuring out what your number is and then ways to improve it,” said Dr. Mosko.

A recent meta-analysis estimated NDR to be 7%, but the patient cohort used was derived from referrals to academic centers, where experienced gastroenterologists may register a higher than average NDR. The study also lacked data on patients, providers, or biopsy quality, which prevented assessment of the effects of NDR on subsequent missed dysplasia or predictors of high or low NDR.

To get a better estimate of NDR, researchers led by Lovekirat Dhaliwal, MD, at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., analyzed data from the Rochester Epidemiology Project, including patients from 11 counties in Minnesota. They identified 1,066 patients with Barrett’s esophagus, 71.1% of whom were male, with a mean age of 63 years. 77% had surveillance endoscopies performed by gastroenterologists, the remainder by nongastroenterologists such as doctors, surgeons, or internal medicine physicians. About 60% of participants received adequate biopsies per Seattle protocol.

The NDR was 4.9% (95% CI, 3.8%-6.4%), including 3.1% high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and 1.8% EAC. One-quarter of EAC cases had metastatic lymphadenopathy at endoscopy or surgery, and 10.6% had low-grade dysplasia (LGD). Although high-definition monitors and high-resolution endoscopes were added to practices, particularly after 2000, the researchers found no evidence of increasing NDR over time on multivariate analysis. In a separate analysis of targeted biopsies in 54 patients with a visible lesion, 9 had LGD (7.96% of all LGD diagnoses) and 10 had EAC (50.0% of all EAC diagnoses). Visible lesions were more often reported by gastroenterologists than nongastroenterologists (odds ratio, 3.7; P = .0120). Gastroenterologists had a higher rate of NDR on univariate analysis (5.8% vs. 1.7%; P = .0098).

There were 391 Barrett’s esophagus patients with no diagnosis of HGD or EAC at the initial endoscopy underwent another endoscopy at 12 months. At the follow-up procedure, eight patients were found to have HGD/EAC, amounting to 13% of HGD/EAC cases being missed at the index endoscopy. There was no statistically significant association between a missed dysplasia or found dysplasia and segment length (4.7 cm vs. 3.7 cm; P = .4), Seattle protocol adherence (62% vs. 58.7%; P = .8), visibility of lesions (OR, 0.6; P = .55), age, smoking history, or practitioner specialty.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Aging. Dr. Mosko has no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Dhaliwal L et al. Clin Gastro Hepatol. 2020 Jul 21. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.07.034.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

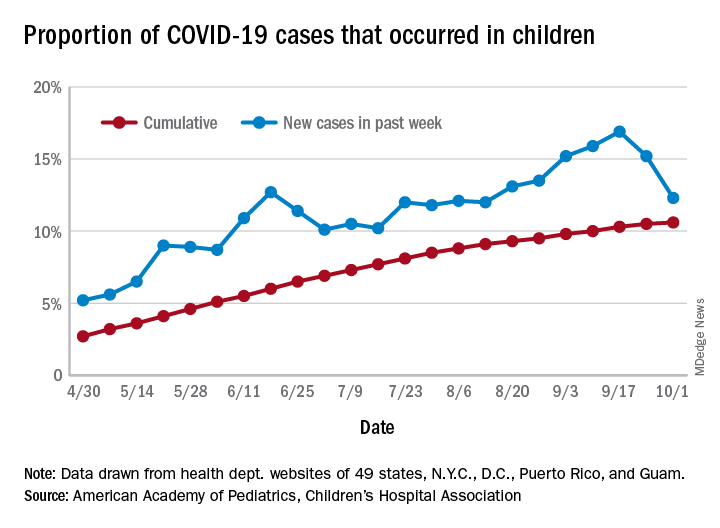

One measure of child COVID-19 may be trending downward

After increasing for several weeks, the proportion of new COVID-19 cases occurring in children has dropped for the second week in a row, according to data in a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

COVID-19 cases in children accounted for 12.3% of all new cases in the United States for the week ending Oct. 1, down from 15.2% the previous week. That measure had reached its highest point, 16.9%, just one week earlier (Sept. 17), the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not provide ages on its website), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The child COVID-19 rate for the United States was 874 per 100,000 children as of Oct. 1, and that figure has doubled since the end of July. At the state level, the highest rates can be found in Tennessee (2,031.4 per 100,000), North Dakota (2,029.6), and South Carolina (2,002.6), with the lowest rates in Vermont (168.9), Maine (229.1), and New Hampshire (268.3), the AAP/CHA report shows.

The children of Wyoming make up the largest share, 22.4%, of any state’s COVID-19 cases, followed by North Dakota and Tennessee, both at 18.3%. New Jersey is lower than any other state at 3.9%, although New York City is a slightly lower 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said.

“The data are limited because the states differ in how they report the data, and it is unknown how many children have been infected but not tested. It is unclear how much of the increase in child cases is due to increased testing capacity,” the AAP said in an earlier statement.

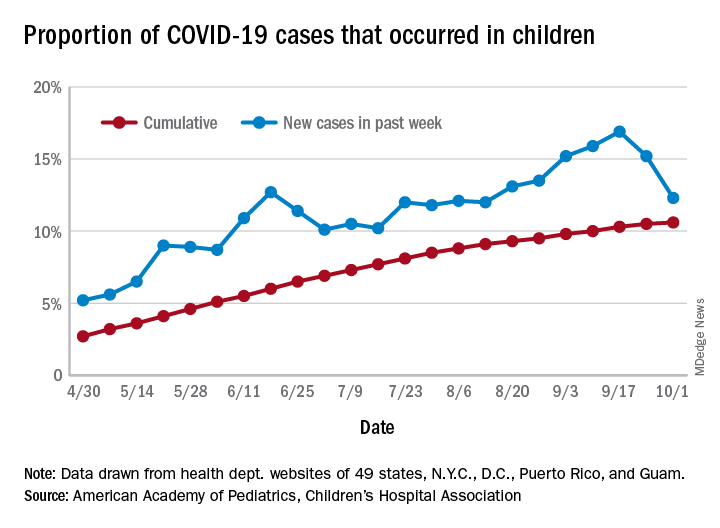

After increasing for several weeks, the proportion of new COVID-19 cases occurring in children has dropped for the second week in a row, according to data in a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

COVID-19 cases in children accounted for 12.3% of all new cases in the United States for the week ending Oct. 1, down from 15.2% the previous week. That measure had reached its highest point, 16.9%, just one week earlier (Sept. 17), the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not provide ages on its website), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The child COVID-19 rate for the United States was 874 per 100,000 children as of Oct. 1, and that figure has doubled since the end of July. At the state level, the highest rates can be found in Tennessee (2,031.4 per 100,000), North Dakota (2,029.6), and South Carolina (2,002.6), with the lowest rates in Vermont (168.9), Maine (229.1), and New Hampshire (268.3), the AAP/CHA report shows.

The children of Wyoming make up the largest share, 22.4%, of any state’s COVID-19 cases, followed by North Dakota and Tennessee, both at 18.3%. New Jersey is lower than any other state at 3.9%, although New York City is a slightly lower 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said.

“The data are limited because the states differ in how they report the data, and it is unknown how many children have been infected but not tested. It is unclear how much of the increase in child cases is due to increased testing capacity,” the AAP said in an earlier statement.

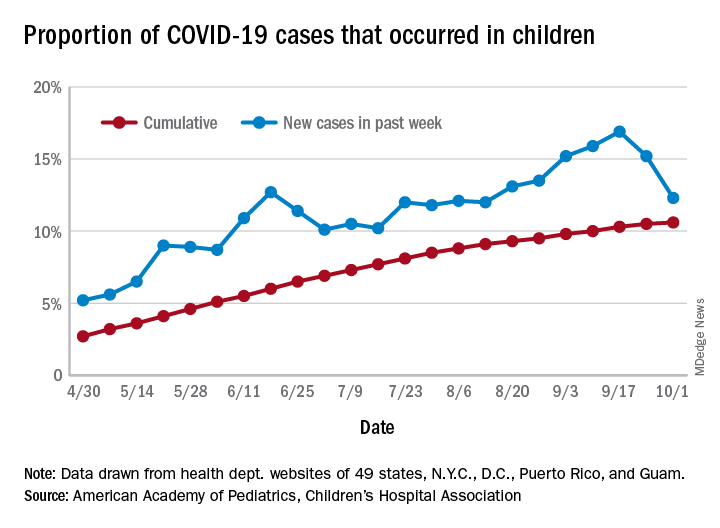

After increasing for several weeks, the proportion of new COVID-19 cases occurring in children has dropped for the second week in a row, according to data in a new report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

COVID-19 cases in children accounted for 12.3% of all new cases in the United States for the week ending Oct. 1, down from 15.2% the previous week. That measure had reached its highest point, 16.9%, just one week earlier (Sept. 17), the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

based on data from the health departments of 49 states (New York does not provide ages on its website), as well as the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

The child COVID-19 rate for the United States was 874 per 100,000 children as of Oct. 1, and that figure has doubled since the end of July. At the state level, the highest rates can be found in Tennessee (2,031.4 per 100,000), North Dakota (2,029.6), and South Carolina (2,002.6), with the lowest rates in Vermont (168.9), Maine (229.1), and New Hampshire (268.3), the AAP/CHA report shows.

The children of Wyoming make up the largest share, 22.4%, of any state’s COVID-19 cases, followed by North Dakota and Tennessee, both at 18.3%. New Jersey is lower than any other state at 3.9%, although New York City is a slightly lower 3.6%, the AAP and CHA said.

“The data are limited because the states differ in how they report the data, and it is unknown how many children have been infected but not tested. It is unclear how much of the increase in child cases is due to increased testing capacity,” the AAP said in an earlier statement.