User login

Continuous Cryotherapy vs Ice Following Total Shoulder Arthroplasty: A Randomized Control Trial

ABSTRACT

Postoperative pain management is an important component of total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Continuous cryotherapy (CC) has been proposed as a means of improving postoperative pain control. However, CC represents an increased cost not typically covered by insurance. The purpose of this study is to compare CC to plain ice (ICE) following TSA. The hypothesis was that CC would lead to lower pain scores and decreased narcotic usage during the first 2 weeks postoperatively.

A randomized controlled trial was performed to compare CC to ICE. Forty patients were randomized to receive either CC or ICE following TSA. The rehabilitation and pain control protocols were otherwise standardized. Visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, satisfaction with cold therapy, and quality of sleep were recorded preoperatively and postoperatively at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days following surgery. Narcotic usage in morphine equivalents was also recorded.

No significant differences in preoperative pain (5.9 vs 6.8; P = .121), or postoperative pain at 24 hours (4.2 vs 4.3; P = .989), 3 days (4.8 vs 4.7; P = .944), 7 days (2.9 vs 3.3; P = .593) or 14 days (2.5 vs 2.7; P = .742) were observed between the CC and ICE groups. Similarly, no differences in quality of sleep, satisfaction with the cold therapy, or narcotic usage at any time interval were observed between the 2 groups.

No differences in pain control, quality of sleep, patient satisfaction, or narcotic usage were detected between CC and ICE following TSA. CC may offer convenience as an advantage, but the increased cost associated with this type of treatment may not be justified.

The number of total shoulder arthroplasties (TSAs) performed annually is increasing dramatically.1 At the same time, there has been a push toward decreased length of hospital stay and earlier mobilization following joint replacement surgery. Central to these goals is adequate pain control. Multimodal pain pathways exist, and one of the safest and cheapest methods of pain control is cold therapy, which can be accomplished with continuous cryotherapy (CC) or plain ice (ICE).

Continue to: The mechanism of cryotherapy...

The mechanism of cryotherapy for controlling pain is poorly understood. Cryotherapy reduces leukocyte migration and slows down nerve signal transmission, which reduces inflammation, thereby producing a short-term analgesic effect. Stalman and colleagues2 reported on a randomized control study that evaluated the effects of postoperative cooling after knee arthroscopy. Measurements of metabolic and inflammatory markers in the synovial membrane were used to assess whether cryotherapy provides a temperature-sensitive release of prostaglandin E2. Cryotherapy lowered the temperature in the postoperative knee, and synovial prostaglandin concentrations were correlated with temperature. Because prostaglandin is a marker of inflammation and pain, the conclusion was that postoperative cooling appeared to have an anti-inflammatory effect.

The knee literature contains multiple studies that have examined the benefits of cryotherapy after both arthroscopic and arthroplasty procedures. The clinical benefits on pain have been equivocal with some studies showing improvements using cryotherapy3,4 and others showing no difference in the treatment group.5,6

Few studies have examined cryotherapy for the shoulder. Speer and colleagues7 demonstrated that postoperative use of CC was effective in reducing recovery time after shoulder surgery. However; they did not provide an ICE comparative group and did not focus specifically on TSA. In another study, Kraeutler and colleagues8 examined only arthroscopic shoulder surgery cases in a randomized prospective trial and found no significant different between CC and ICE. They concluded that there did not appear to be a significant benefit in using CC over ICE for arthroscopic shoulder procedures.

The purpose of this study is to prospectively evaluate CC and ICE following TSA. The hypothesis was that CC leads to improved pain control, less narcotic consumption, and improved quality of sleep compared to ICE in the immediate postoperative period following TSA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective randomized control study of patients undergoing TSA receiving either CC or ICE postoperatively. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before commencement of the study. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 30 to 90 years old undergoing a primary or revision shoulder arthroplasty procedure between June 2015 and January 2016. Exclusion criteria included hemiarthroplasty procedures.

Continue to: Three patients refused...

Three patients refused to participate in the study. Enrollment was performed until 40 patients were enrolled in the study (20 patients in each group). Randomization was performed with a random number generator, and patients were assigned to a treatment group following consent to participate. Complete follow-up was available for all patients. There were 13 (65%) male patients in the CC group. The average age of the CC group at the time of surgery was 68.7 years (range). There were 11 male patients in the ICE group. The average age of the ICE group at the time of surgery was 73.2 years (range). The dominant extremity was involved in 9 (45%) patients in the CC group and in 11 patients (55%) in the ICE group. Surgical case specifics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Surgical Cases

| CC group (n = 20) | ICE group (n = 20) |

Primary TSA | 7 (35%) | 9 (45%) |

Primary RSA | 12 (60%) | 9 (45%) |

Revision arthroplasty | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; ICE, plain ice; RSA, reverse shoulder arthroplasty; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

All surgeries were performed by Dr. Denard. All patients received a single-shot interscalene nerve block prior to the procedure. A deltopectoral approach was utilized, and the subscapularis was managed with the peel technique.9 All patients were admitted to the hospital following surgery. Standard postoperative pain control consisted of as-needed intravenous morphine (1-2 mg every 2 hours, as needed) or an oral narcotic (hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325mg, 1-2 every 4 hours, as needed) which was also provided at discharge. However, total narcotic usage was recorded in morphine equivalents to account for substitutions. No non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were allowed until 3 months postoperatively.

The CC group received treatment from a commercially available cryotherapy unit (Polar Care; Breg). All patients received instructions by a medical professional on how to use the unit. The unit was applied immediately postoperatively and set at a temperature of 45°F to 55°F. Patients were instructed to use the unit continuously during postoperative days 0 to 3. This cryotherapy was administered by a nurse while in the hospital but was left to the responsibility of the patient upon discharge. Patients were instructed to use the unit as needed for pain control during the day and continuously while asleep from days 4 to14.

The ICE group used standard ice packs postoperatively. The patients were instructed to apply an ice pack for 20 min every 2 hours while awake during days 0 to 3. This therapy was administered by a nurse while in the hospital but left to the responsibility of the patient upon discharge. Patients were instructed to use ice packs as needed for pain control during the day at a maximum of 20 minutes per hour on postoperative days 4 to 14. Compliance by both groups was monitored using a patient survey after hospital discharge. The number of hours that patients used either the CC or ICE per 24-hour period was recorded at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days. The nursing staff recorded the number of hours of use of either cold modality for each patient prior to hospital discharge. The average length of stay as an inpatient was 1.2 days for the CC group and 1.3 days for the ICE group.

Visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, satisfaction with the cold therapy, and quality of sleep were recorded preoperatively and postoperatively at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days following surgery.

Continue to: The Wilcoxon rank-sum test...

STATISTICAL METHOD

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to assess whether scores changed significantly from the preoperative period to the different postoperative time intervals, as well as to assess the values for pain, quality of sleep, and patient satisfaction. P-values <.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

No differences were observed in the baseline characteristics between the 2 groups. Both groups showed improvements in pain, quality of sleep, and satisfaction with the cold therapy from the preoperative period to the final follow-up.

The VAS pain scores were not different between the CC and ICE groups preoperatively (5.9 vs 6.8; P = .121) or postoperatively at 24 hours (4.2 vs 4.3; P = .989), 3 days (4.8 vs 4.7; P = .944), 7 days (2.9 vs 3.3; P = .593), or 14 days (2.5 vs 2.7; P = .742). Both cohorts demonstrated improved overall pain throughout the study period. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of VAS Pain Scores With Cold Therapy

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

Preoperative | 5.9 ± 4.1 | 6.8 ± 5.3 | .121 | 3.3-8.3 |

24 hours | 4.2 ± 3.0 | 4.3 ± 3.1 | .989 | 2.9-5.7 |

3 days | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 4.7 ± 3.2 | .944 | 3.2-6.3 |

7 days | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 3.3 ± 2.5 | .593 | 2.1-4.4 |

14 days | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | .742 | 1.5-3.6 |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice; VAS, visual analog scales.

The number of morphine equivalents of pain medication was not different between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (43 vs 38 mg; P = .579), 3 days (149 vs 116 mg; P = .201), 7 days (308 vs 228 mg; P = .181), or 14 days (431 vs 348 mg; P = .213). Both groups showed increased narcotic consumption from 24 hours postoperatively until the 2-week follow-up. Narcotic consumption is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of Narcotic Consumption in Morphine Equivalents

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

24 hours | 43.0 ± 36.7 | 38.0 ± 42.9 | .579 | 17.9-60.1 |

3 days | 149.0 ± 106.5 | 116.3 ± 108.9 | .201 | 63.4-198.7 |

7 days | 308.1 ± 234.0 | 228 ± 258.3 | .181 | 107.1-348.9 |

14 days | 430.8 ± 384.2 | 347.5 ± 493.4 | .213 | 116.6-610.6 |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice.

VAS for quality of sleep improved in both groups from 24 hours postoperatively until the final follow-up. However, no significant differences in sleep quality were observed between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (5.1 vs 4.3; P = .382), 3 days (5.1 vs 5.3; P = .601), 7 days (6.0 vs 6.7; P = .319), or 14 days (6.5 vs 7.1; P = .348). The VAS scores for sleep quality are reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of VAS Sleep Quality With Cold Therapya

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

24 hours | 5.1 ± 2.8 | 4.3 ± 2.4 | .382 | 3.2-6.4 |

3 days | 5.1 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | .601 | 4.2-6.5 |

7 days | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | .319 | 4.9-7.7 |

14 days | 6.5 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | .348 | 5.3-8.4 |

a0-10 rating with 10 being the highest possible score.

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice; VAS, visual analog scales.

Continue to: Finally, VAS patient satisfaction...

Finally, VAS patient satisfaction scores were not different between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (7.3 vs 6.1; P = .315), 3 days (6.1 vs 6.6; P = .698), 7 days (6.6 vs 6.9; P = .670), or 14 days (7.1 vs 6.3; P = .288).

While compliance within each group utilizing the randomly assigned cold modality was similar, the usage by the CC group was consistently higher at all time points recorded. No complications or reoperations were observed in either group.

DISCUSSION

The optimal method for managing postoperative pain from an arthroplasty procedure is controversial. This prospective randomized study attempted to confirm the hypothesis that CC infers better pain control, improves quality of sleep, and decreases narcotic usage compared to ICE in the first 2 weeks after a TSA procedure. The results of this study refuted our hypothesis, demonstrating no significant difference in pain control, satisfaction, narcotic usage, or sleep quality between the CC and ICE cohorts at all time points studied.

Studies on knees and lower extremities demonstrate equivocal results for the role CC plays in providing improved postoperative pain control. Thienpont10 evaluated CC in a randomized control trial comparing plain ice packs postoperatively in patients who underwent TKA. The author found no significant difference in VAS for pain or narcotic consumption in morphine equivalents. Thienpont10 recommended that CC not be used for outpatient knee arthroplasty as it is an additional cost that does not improve pain significantly. Healy and colleagues5 reported similar results that CC did not demonstrate a difference in narcotic requirement or pain control compared to plain ice packs, as well as no difference in local postoperative swelling or wound drainage. However, a recently published randomized trial by Su and colleagues11 comparing a cryopneumatic device and ICE with static compression in patients who underwent TKA demonstrated significantly lower narcotic consumption and increased ambulation distances in the treatment group. The treatment group consumed approximately 170 mg morphine equivalents less than the control group between discharge and the 2-week postoperative visit. In addition, a significant difference was observed in the satisfaction scores in the treatment group.11 Similarly, a meta-analysis by Raynor and colleagues12 on randomized clinical trials comparing cryotherapy to a placebo group after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction showed that cryotherapy is associated with significantly lower postoperative pain (P = .02), but demonstrated no difference in postoperative drainage (P = .23) or range of motion (P = .25).

Although multiple studies have been published regarding the efficacy of cryotherapy after knee surgery, very few studies have compared CC to conventional ICE after shoulder surgery. A prospective randomized trial was performed by Singh and colleagues13 to compare CC vs no ICE in open and arthroscopic shoulder surgery patients. Both the open and arthroscopic groups receiving CC demonstrated significant reductions in pain frequency and more restful sleep at the 7-day, 14-day, and 21-day intervals compared to the control group. However, they did not compare the commercial unit to ICE. In contrast, a study by Kraeutler and colleagues8 randomized 46 patients to receive either CC or ICE in the setting of arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Although no significant difference was observed in morphine equivalent dosage between the 2 groups, the CC group used more pain medication on every postoperative day during the first week after surgery. They found no difference between the 2 groups with regards to narcotic consumption or pain scores. The results of this study mirror those by Kraeutler and colleagues,8 demonstrating no difference in pain scores, sleep quality, or narcotic consumption.

Continue to: With rising costs in the US...

With rising costs in the US healthcare system, a great deal of interest has developed in the application of value-based principles to healthcare. Value can be defined as a gain in benefits over the costs expended.14 The average cost for a commercial CC unit used in this study was $260. A pack of ICE is a nominal cost. Based on the results of this study, the cost of the commercial CC device may not be justified when compared to the cost of an ice pack.

The major strengths of this study are the randomized design and multiple data points during the early postoperative period. However, there are several limitations. First, we did not objectively measure compliance of either therapy and relied only on a patient survey. Usage of the commercial CC unit in hours decreased over half between days 3 and 14. This occurred despite training on the application and specific instructions. We believe this reflects “real-world” usage, but it is possible that compliance affected our results. Second, all patients in this study had a single-shot interscalene block. While this is standard at our institution, it is possible that either CC or ICE would have a more significant effect in the absence of an interscalene block. Finally, we did not evaluate final outcomes in this study and therefore cannot determine if the final outcome was different between the 2 groups. Our goal was simply to evaluate the first 2 weeks following surgery, as this is the most painful period following TSA.

CONCLUSION

There was no difference between CC and ICE in terms of pain control, quality of sleep, patient satisfaction, or narcotic consumption following TSA. CC may offer convenience advantages, but the increased cost associated with this type of unit may not be justified.

1. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/jbjs.j.01994.

2. Stalman A, Berglund L, Dungnerc E, Arner P, Fellander-Tsai L. Temperature sensitive release of prostaglandin E2 and diminished energy requirements in synovial tissue with postoperative cryotherapy: a prospective randomized study after knee arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):1961-1968. doi:10.2016/jbjs.j.01790.

3. Levy AS, Marmar E. The role of cold compression dressings in the postoperative treatment of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;297:174-178. doi:10.1097/00003086-199312000-00029.

4. Webb JM, Williams D, Ivory JP, Day S, Williamson DM. The use of cold compression dressings after total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Orthopaedics 1998;21(1):59-61.

5. Healy WL, Seidman J, Pfeifer BA, Brown DG. Cold compressive dressing after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:143-146. doi:10.1097/00003086-199402000-00019.

6. Whitelaw GP, DeMuth KA, Demos HA, Schepsis A, Jacques E. The use of Cryo/Cuff versus ice and elastic wrap in the postoperative care of knee arthroscopy patients. Am J Knee Surg. 1995;8(1):28-30.

7. Speer KP, Warren RF, Horowitz L. The efficacy of cryotherapy in the postoperative shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(1):62-68. doi:10.16/s1058-2746(96)80032-2.

8. Kraeutler MJ, Reynolds KA, Long C, McCarthy EC. Compressive cryotherapy versus ice- a prospective, randomized study on postoperative pain in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):854-859. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.004.

9. DeFranco MJ, Higgins LD, Warner JP. Subscapularis management in open shoulder surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(12):707-717. doi:10.5435/00124635-201012000-00001.

10. Thienpont E. Does advanced cryotherapy reduce pain and narcotic consumption after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3417-3423. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3810-8.

11. Su EP, Perna M, Boettner F, Mayman DJ, et al. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a cryopneumatic device on total knee arthroplasty recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):153-156. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.94B11.30832.

12. Raynor MC, Pietrobon R, Guller U, Higgins LD. Cryotherapy after ACL reconstruction- a meta analysis. J Knee Surg. 2005;18(2):123-129. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1248169.

13. Singh H, Osbahr DC, Holovacs TF, Cawley PW, Speer KP. The efficacy of continuous cryotherapy on the postoperative shoulder: a prospective randomized investigation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(6):522-525. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.118415.

14. Black EM, Higgins LD, Warner JP. Value based shoulder surgery: outcomes driven, cost-conscious care. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.se.2013.02.008.

ABSTRACT

Postoperative pain management is an important component of total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Continuous cryotherapy (CC) has been proposed as a means of improving postoperative pain control. However, CC represents an increased cost not typically covered by insurance. The purpose of this study is to compare CC to plain ice (ICE) following TSA. The hypothesis was that CC would lead to lower pain scores and decreased narcotic usage during the first 2 weeks postoperatively.

A randomized controlled trial was performed to compare CC to ICE. Forty patients were randomized to receive either CC or ICE following TSA. The rehabilitation and pain control protocols were otherwise standardized. Visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, satisfaction with cold therapy, and quality of sleep were recorded preoperatively and postoperatively at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days following surgery. Narcotic usage in morphine equivalents was also recorded.

No significant differences in preoperative pain (5.9 vs 6.8; P = .121), or postoperative pain at 24 hours (4.2 vs 4.3; P = .989), 3 days (4.8 vs 4.7; P = .944), 7 days (2.9 vs 3.3; P = .593) or 14 days (2.5 vs 2.7; P = .742) were observed between the CC and ICE groups. Similarly, no differences in quality of sleep, satisfaction with the cold therapy, or narcotic usage at any time interval were observed between the 2 groups.

No differences in pain control, quality of sleep, patient satisfaction, or narcotic usage were detected between CC and ICE following TSA. CC may offer convenience as an advantage, but the increased cost associated with this type of treatment may not be justified.

The number of total shoulder arthroplasties (TSAs) performed annually is increasing dramatically.1 At the same time, there has been a push toward decreased length of hospital stay and earlier mobilization following joint replacement surgery. Central to these goals is adequate pain control. Multimodal pain pathways exist, and one of the safest and cheapest methods of pain control is cold therapy, which can be accomplished with continuous cryotherapy (CC) or plain ice (ICE).

Continue to: The mechanism of cryotherapy...

The mechanism of cryotherapy for controlling pain is poorly understood. Cryotherapy reduces leukocyte migration and slows down nerve signal transmission, which reduces inflammation, thereby producing a short-term analgesic effect. Stalman and colleagues2 reported on a randomized control study that evaluated the effects of postoperative cooling after knee arthroscopy. Measurements of metabolic and inflammatory markers in the synovial membrane were used to assess whether cryotherapy provides a temperature-sensitive release of prostaglandin E2. Cryotherapy lowered the temperature in the postoperative knee, and synovial prostaglandin concentrations were correlated with temperature. Because prostaglandin is a marker of inflammation and pain, the conclusion was that postoperative cooling appeared to have an anti-inflammatory effect.

The knee literature contains multiple studies that have examined the benefits of cryotherapy after both arthroscopic and arthroplasty procedures. The clinical benefits on pain have been equivocal with some studies showing improvements using cryotherapy3,4 and others showing no difference in the treatment group.5,6

Few studies have examined cryotherapy for the shoulder. Speer and colleagues7 demonstrated that postoperative use of CC was effective in reducing recovery time after shoulder surgery. However; they did not provide an ICE comparative group and did not focus specifically on TSA. In another study, Kraeutler and colleagues8 examined only arthroscopic shoulder surgery cases in a randomized prospective trial and found no significant different between CC and ICE. They concluded that there did not appear to be a significant benefit in using CC over ICE for arthroscopic shoulder procedures.

The purpose of this study is to prospectively evaluate CC and ICE following TSA. The hypothesis was that CC leads to improved pain control, less narcotic consumption, and improved quality of sleep compared to ICE in the immediate postoperative period following TSA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective randomized control study of patients undergoing TSA receiving either CC or ICE postoperatively. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before commencement of the study. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 30 to 90 years old undergoing a primary or revision shoulder arthroplasty procedure between June 2015 and January 2016. Exclusion criteria included hemiarthroplasty procedures.

Continue to: Three patients refused...

Three patients refused to participate in the study. Enrollment was performed until 40 patients were enrolled in the study (20 patients in each group). Randomization was performed with a random number generator, and patients were assigned to a treatment group following consent to participate. Complete follow-up was available for all patients. There were 13 (65%) male patients in the CC group. The average age of the CC group at the time of surgery was 68.7 years (range). There were 11 male patients in the ICE group. The average age of the ICE group at the time of surgery was 73.2 years (range). The dominant extremity was involved in 9 (45%) patients in the CC group and in 11 patients (55%) in the ICE group. Surgical case specifics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Surgical Cases

| CC group (n = 20) | ICE group (n = 20) |

Primary TSA | 7 (35%) | 9 (45%) |

Primary RSA | 12 (60%) | 9 (45%) |

Revision arthroplasty | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; ICE, plain ice; RSA, reverse shoulder arthroplasty; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

All surgeries were performed by Dr. Denard. All patients received a single-shot interscalene nerve block prior to the procedure. A deltopectoral approach was utilized, and the subscapularis was managed with the peel technique.9 All patients were admitted to the hospital following surgery. Standard postoperative pain control consisted of as-needed intravenous morphine (1-2 mg every 2 hours, as needed) or an oral narcotic (hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325mg, 1-2 every 4 hours, as needed) which was also provided at discharge. However, total narcotic usage was recorded in morphine equivalents to account for substitutions. No non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were allowed until 3 months postoperatively.

The CC group received treatment from a commercially available cryotherapy unit (Polar Care; Breg). All patients received instructions by a medical professional on how to use the unit. The unit was applied immediately postoperatively and set at a temperature of 45°F to 55°F. Patients were instructed to use the unit continuously during postoperative days 0 to 3. This cryotherapy was administered by a nurse while in the hospital but was left to the responsibility of the patient upon discharge. Patients were instructed to use the unit as needed for pain control during the day and continuously while asleep from days 4 to14.

The ICE group used standard ice packs postoperatively. The patients were instructed to apply an ice pack for 20 min every 2 hours while awake during days 0 to 3. This therapy was administered by a nurse while in the hospital but left to the responsibility of the patient upon discharge. Patients were instructed to use ice packs as needed for pain control during the day at a maximum of 20 minutes per hour on postoperative days 4 to 14. Compliance by both groups was monitored using a patient survey after hospital discharge. The number of hours that patients used either the CC or ICE per 24-hour period was recorded at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days. The nursing staff recorded the number of hours of use of either cold modality for each patient prior to hospital discharge. The average length of stay as an inpatient was 1.2 days for the CC group and 1.3 days for the ICE group.

Visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, satisfaction with the cold therapy, and quality of sleep were recorded preoperatively and postoperatively at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days following surgery.

Continue to: The Wilcoxon rank-sum test...

STATISTICAL METHOD

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to assess whether scores changed significantly from the preoperative period to the different postoperative time intervals, as well as to assess the values for pain, quality of sleep, and patient satisfaction. P-values <.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

No differences were observed in the baseline characteristics between the 2 groups. Both groups showed improvements in pain, quality of sleep, and satisfaction with the cold therapy from the preoperative period to the final follow-up.

The VAS pain scores were not different between the CC and ICE groups preoperatively (5.9 vs 6.8; P = .121) or postoperatively at 24 hours (4.2 vs 4.3; P = .989), 3 days (4.8 vs 4.7; P = .944), 7 days (2.9 vs 3.3; P = .593), or 14 days (2.5 vs 2.7; P = .742). Both cohorts demonstrated improved overall pain throughout the study period. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of VAS Pain Scores With Cold Therapy

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

Preoperative | 5.9 ± 4.1 | 6.8 ± 5.3 | .121 | 3.3-8.3 |

24 hours | 4.2 ± 3.0 | 4.3 ± 3.1 | .989 | 2.9-5.7 |

3 days | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 4.7 ± 3.2 | .944 | 3.2-6.3 |

7 days | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 3.3 ± 2.5 | .593 | 2.1-4.4 |

14 days | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | .742 | 1.5-3.6 |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice; VAS, visual analog scales.

The number of morphine equivalents of pain medication was not different between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (43 vs 38 mg; P = .579), 3 days (149 vs 116 mg; P = .201), 7 days (308 vs 228 mg; P = .181), or 14 days (431 vs 348 mg; P = .213). Both groups showed increased narcotic consumption from 24 hours postoperatively until the 2-week follow-up. Narcotic consumption is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of Narcotic Consumption in Morphine Equivalents

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

24 hours | 43.0 ± 36.7 | 38.0 ± 42.9 | .579 | 17.9-60.1 |

3 days | 149.0 ± 106.5 | 116.3 ± 108.9 | .201 | 63.4-198.7 |

7 days | 308.1 ± 234.0 | 228 ± 258.3 | .181 | 107.1-348.9 |

14 days | 430.8 ± 384.2 | 347.5 ± 493.4 | .213 | 116.6-610.6 |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice.

VAS for quality of sleep improved in both groups from 24 hours postoperatively until the final follow-up. However, no significant differences in sleep quality were observed between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (5.1 vs 4.3; P = .382), 3 days (5.1 vs 5.3; P = .601), 7 days (6.0 vs 6.7; P = .319), or 14 days (6.5 vs 7.1; P = .348). The VAS scores for sleep quality are reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of VAS Sleep Quality With Cold Therapya

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

24 hours | 5.1 ± 2.8 | 4.3 ± 2.4 | .382 | 3.2-6.4 |

3 days | 5.1 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | .601 | 4.2-6.5 |

7 days | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | .319 | 4.9-7.7 |

14 days | 6.5 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | .348 | 5.3-8.4 |

a0-10 rating with 10 being the highest possible score.

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice; VAS, visual analog scales.

Continue to: Finally, VAS patient satisfaction...

Finally, VAS patient satisfaction scores were not different between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (7.3 vs 6.1; P = .315), 3 days (6.1 vs 6.6; P = .698), 7 days (6.6 vs 6.9; P = .670), or 14 days (7.1 vs 6.3; P = .288).

While compliance within each group utilizing the randomly assigned cold modality was similar, the usage by the CC group was consistently higher at all time points recorded. No complications or reoperations were observed in either group.

DISCUSSION

The optimal method for managing postoperative pain from an arthroplasty procedure is controversial. This prospective randomized study attempted to confirm the hypothesis that CC infers better pain control, improves quality of sleep, and decreases narcotic usage compared to ICE in the first 2 weeks after a TSA procedure. The results of this study refuted our hypothesis, demonstrating no significant difference in pain control, satisfaction, narcotic usage, or sleep quality between the CC and ICE cohorts at all time points studied.

Studies on knees and lower extremities demonstrate equivocal results for the role CC plays in providing improved postoperative pain control. Thienpont10 evaluated CC in a randomized control trial comparing plain ice packs postoperatively in patients who underwent TKA. The author found no significant difference in VAS for pain or narcotic consumption in morphine equivalents. Thienpont10 recommended that CC not be used for outpatient knee arthroplasty as it is an additional cost that does not improve pain significantly. Healy and colleagues5 reported similar results that CC did not demonstrate a difference in narcotic requirement or pain control compared to plain ice packs, as well as no difference in local postoperative swelling or wound drainage. However, a recently published randomized trial by Su and colleagues11 comparing a cryopneumatic device and ICE with static compression in patients who underwent TKA demonstrated significantly lower narcotic consumption and increased ambulation distances in the treatment group. The treatment group consumed approximately 170 mg morphine equivalents less than the control group between discharge and the 2-week postoperative visit. In addition, a significant difference was observed in the satisfaction scores in the treatment group.11 Similarly, a meta-analysis by Raynor and colleagues12 on randomized clinical trials comparing cryotherapy to a placebo group after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction showed that cryotherapy is associated with significantly lower postoperative pain (P = .02), but demonstrated no difference in postoperative drainage (P = .23) or range of motion (P = .25).

Although multiple studies have been published regarding the efficacy of cryotherapy after knee surgery, very few studies have compared CC to conventional ICE after shoulder surgery. A prospective randomized trial was performed by Singh and colleagues13 to compare CC vs no ICE in open and arthroscopic shoulder surgery patients. Both the open and arthroscopic groups receiving CC demonstrated significant reductions in pain frequency and more restful sleep at the 7-day, 14-day, and 21-day intervals compared to the control group. However, they did not compare the commercial unit to ICE. In contrast, a study by Kraeutler and colleagues8 randomized 46 patients to receive either CC or ICE in the setting of arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Although no significant difference was observed in morphine equivalent dosage between the 2 groups, the CC group used more pain medication on every postoperative day during the first week after surgery. They found no difference between the 2 groups with regards to narcotic consumption or pain scores. The results of this study mirror those by Kraeutler and colleagues,8 demonstrating no difference in pain scores, sleep quality, or narcotic consumption.

Continue to: With rising costs in the US...

With rising costs in the US healthcare system, a great deal of interest has developed in the application of value-based principles to healthcare. Value can be defined as a gain in benefits over the costs expended.14 The average cost for a commercial CC unit used in this study was $260. A pack of ICE is a nominal cost. Based on the results of this study, the cost of the commercial CC device may not be justified when compared to the cost of an ice pack.

The major strengths of this study are the randomized design and multiple data points during the early postoperative period. However, there are several limitations. First, we did not objectively measure compliance of either therapy and relied only on a patient survey. Usage of the commercial CC unit in hours decreased over half between days 3 and 14. This occurred despite training on the application and specific instructions. We believe this reflects “real-world” usage, but it is possible that compliance affected our results. Second, all patients in this study had a single-shot interscalene block. While this is standard at our institution, it is possible that either CC or ICE would have a more significant effect in the absence of an interscalene block. Finally, we did not evaluate final outcomes in this study and therefore cannot determine if the final outcome was different between the 2 groups. Our goal was simply to evaluate the first 2 weeks following surgery, as this is the most painful period following TSA.

CONCLUSION

There was no difference between CC and ICE in terms of pain control, quality of sleep, patient satisfaction, or narcotic consumption following TSA. CC may offer convenience advantages, but the increased cost associated with this type of unit may not be justified.

ABSTRACT

Postoperative pain management is an important component of total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Continuous cryotherapy (CC) has been proposed as a means of improving postoperative pain control. However, CC represents an increased cost not typically covered by insurance. The purpose of this study is to compare CC to plain ice (ICE) following TSA. The hypothesis was that CC would lead to lower pain scores and decreased narcotic usage during the first 2 weeks postoperatively.

A randomized controlled trial was performed to compare CC to ICE. Forty patients were randomized to receive either CC or ICE following TSA. The rehabilitation and pain control protocols were otherwise standardized. Visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, satisfaction with cold therapy, and quality of sleep were recorded preoperatively and postoperatively at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days following surgery. Narcotic usage in morphine equivalents was also recorded.

No significant differences in preoperative pain (5.9 vs 6.8; P = .121), or postoperative pain at 24 hours (4.2 vs 4.3; P = .989), 3 days (4.8 vs 4.7; P = .944), 7 days (2.9 vs 3.3; P = .593) or 14 days (2.5 vs 2.7; P = .742) were observed between the CC and ICE groups. Similarly, no differences in quality of sleep, satisfaction with the cold therapy, or narcotic usage at any time interval were observed between the 2 groups.

No differences in pain control, quality of sleep, patient satisfaction, or narcotic usage were detected between CC and ICE following TSA. CC may offer convenience as an advantage, but the increased cost associated with this type of treatment may not be justified.

The number of total shoulder arthroplasties (TSAs) performed annually is increasing dramatically.1 At the same time, there has been a push toward decreased length of hospital stay and earlier mobilization following joint replacement surgery. Central to these goals is adequate pain control. Multimodal pain pathways exist, and one of the safest and cheapest methods of pain control is cold therapy, which can be accomplished with continuous cryotherapy (CC) or plain ice (ICE).

Continue to: The mechanism of cryotherapy...

The mechanism of cryotherapy for controlling pain is poorly understood. Cryotherapy reduces leukocyte migration and slows down nerve signal transmission, which reduces inflammation, thereby producing a short-term analgesic effect. Stalman and colleagues2 reported on a randomized control study that evaluated the effects of postoperative cooling after knee arthroscopy. Measurements of metabolic and inflammatory markers in the synovial membrane were used to assess whether cryotherapy provides a temperature-sensitive release of prostaglandin E2. Cryotherapy lowered the temperature in the postoperative knee, and synovial prostaglandin concentrations were correlated with temperature. Because prostaglandin is a marker of inflammation and pain, the conclusion was that postoperative cooling appeared to have an anti-inflammatory effect.

The knee literature contains multiple studies that have examined the benefits of cryotherapy after both arthroscopic and arthroplasty procedures. The clinical benefits on pain have been equivocal with some studies showing improvements using cryotherapy3,4 and others showing no difference in the treatment group.5,6

Few studies have examined cryotherapy for the shoulder. Speer and colleagues7 demonstrated that postoperative use of CC was effective in reducing recovery time after shoulder surgery. However; they did not provide an ICE comparative group and did not focus specifically on TSA. In another study, Kraeutler and colleagues8 examined only arthroscopic shoulder surgery cases in a randomized prospective trial and found no significant different between CC and ICE. They concluded that there did not appear to be a significant benefit in using CC over ICE for arthroscopic shoulder procedures.

The purpose of this study is to prospectively evaluate CC and ICE following TSA. The hypothesis was that CC leads to improved pain control, less narcotic consumption, and improved quality of sleep compared to ICE in the immediate postoperative period following TSA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a prospective randomized control study of patients undergoing TSA receiving either CC or ICE postoperatively. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before commencement of the study. Inclusion criteria included patients aged 30 to 90 years old undergoing a primary or revision shoulder arthroplasty procedure between June 2015 and January 2016. Exclusion criteria included hemiarthroplasty procedures.

Continue to: Three patients refused...

Three patients refused to participate in the study. Enrollment was performed until 40 patients were enrolled in the study (20 patients in each group). Randomization was performed with a random number generator, and patients were assigned to a treatment group following consent to participate. Complete follow-up was available for all patients. There were 13 (65%) male patients in the CC group. The average age of the CC group at the time of surgery was 68.7 years (range). There were 11 male patients in the ICE group. The average age of the ICE group at the time of surgery was 73.2 years (range). The dominant extremity was involved in 9 (45%) patients in the CC group and in 11 patients (55%) in the ICE group. Surgical case specifics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of Surgical Cases

| CC group (n = 20) | ICE group (n = 20) |

Primary TSA | 7 (35%) | 9 (45%) |

Primary RSA | 12 (60%) | 9 (45%) |

Revision arthroplasty | 1 (5%) | 2 (10%) |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; ICE, plain ice; RSA, reverse shoulder arthroplasty; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty.

All surgeries were performed by Dr. Denard. All patients received a single-shot interscalene nerve block prior to the procedure. A deltopectoral approach was utilized, and the subscapularis was managed with the peel technique.9 All patients were admitted to the hospital following surgery. Standard postoperative pain control consisted of as-needed intravenous morphine (1-2 mg every 2 hours, as needed) or an oral narcotic (hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325mg, 1-2 every 4 hours, as needed) which was also provided at discharge. However, total narcotic usage was recorded in morphine equivalents to account for substitutions. No non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were allowed until 3 months postoperatively.

The CC group received treatment from a commercially available cryotherapy unit (Polar Care; Breg). All patients received instructions by a medical professional on how to use the unit. The unit was applied immediately postoperatively and set at a temperature of 45°F to 55°F. Patients were instructed to use the unit continuously during postoperative days 0 to 3. This cryotherapy was administered by a nurse while in the hospital but was left to the responsibility of the patient upon discharge. Patients were instructed to use the unit as needed for pain control during the day and continuously while asleep from days 4 to14.

The ICE group used standard ice packs postoperatively. The patients were instructed to apply an ice pack for 20 min every 2 hours while awake during days 0 to 3. This therapy was administered by a nurse while in the hospital but left to the responsibility of the patient upon discharge. Patients were instructed to use ice packs as needed for pain control during the day at a maximum of 20 minutes per hour on postoperative days 4 to 14. Compliance by both groups was monitored using a patient survey after hospital discharge. The number of hours that patients used either the CC or ICE per 24-hour period was recorded at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days. The nursing staff recorded the number of hours of use of either cold modality for each patient prior to hospital discharge. The average length of stay as an inpatient was 1.2 days for the CC group and 1.3 days for the ICE group.

Visual analog scales (VAS) for pain, satisfaction with the cold therapy, and quality of sleep were recorded preoperatively and postoperatively at 24 hours, 3 days, 7 days, and 14 days following surgery.

Continue to: The Wilcoxon rank-sum test...

STATISTICAL METHOD

The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to assess whether scores changed significantly from the preoperative period to the different postoperative time intervals, as well as to assess the values for pain, quality of sleep, and patient satisfaction. P-values <.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

No differences were observed in the baseline characteristics between the 2 groups. Both groups showed improvements in pain, quality of sleep, and satisfaction with the cold therapy from the preoperative period to the final follow-up.

The VAS pain scores were not different between the CC and ICE groups preoperatively (5.9 vs 6.8; P = .121) or postoperatively at 24 hours (4.2 vs 4.3; P = .989), 3 days (4.8 vs 4.7; P = .944), 7 days (2.9 vs 3.3; P = .593), or 14 days (2.5 vs 2.7; P = .742). Both cohorts demonstrated improved overall pain throughout the study period. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Summary of VAS Pain Scores With Cold Therapy

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

Preoperative | 5.9 ± 4.1 | 6.8 ± 5.3 | .121 | 3.3-8.3 |

24 hours | 4.2 ± 3.0 | 4.3 ± 3.1 | .989 | 2.9-5.7 |

3 days | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 4.7 ± 3.2 | .944 | 3.2-6.3 |

7 days | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 3.3 ± 2.5 | .593 | 2.1-4.4 |

14 days | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | .742 | 1.5-3.6 |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice; VAS, visual analog scales.

The number of morphine equivalents of pain medication was not different between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (43 vs 38 mg; P = .579), 3 days (149 vs 116 mg; P = .201), 7 days (308 vs 228 mg; P = .181), or 14 days (431 vs 348 mg; P = .213). Both groups showed increased narcotic consumption from 24 hours postoperatively until the 2-week follow-up. Narcotic consumption is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of Narcotic Consumption in Morphine Equivalents

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

24 hours | 43.0 ± 36.7 | 38.0 ± 42.9 | .579 | 17.9-60.1 |

3 days | 149.0 ± 106.5 | 116.3 ± 108.9 | .201 | 63.4-198.7 |

7 days | 308.1 ± 234.0 | 228 ± 258.3 | .181 | 107.1-348.9 |

14 days | 430.8 ± 384.2 | 347.5 ± 493.4 | .213 | 116.6-610.6 |

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice.

VAS for quality of sleep improved in both groups from 24 hours postoperatively until the final follow-up. However, no significant differences in sleep quality were observed between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (5.1 vs 4.3; P = .382), 3 days (5.1 vs 5.3; P = .601), 7 days (6.0 vs 6.7; P = .319), or 14 days (6.5 vs 7.1; P = .348). The VAS scores for sleep quality are reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of VAS Sleep Quality With Cold Therapya

| CC group (mean ± SD) | ICE group (mean ± SD) | P value | 95% CI |

24 hours | 5.1 ± 2.8 | 4.3 ± 2.4 | .382 | 3.2-6.4 |

3 days | 5.1 ± 1.9 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | .601 | 4.2-6.5 |

7 days | 6.0 ± 2.3 | 6.7 ± 2.1 | .319 | 4.9-7.7 |

14 days | 6.5 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | .348 | 5.3-8.4 |

a0-10 rating with 10 being the highest possible score.

Abbreviations: CC, continuous cryotherapy; CI, confidence interval; ICE, plain ice; VAS, visual analog scales.

Continue to: Finally, VAS patient satisfaction...

Finally, VAS patient satisfaction scores were not different between the CC and ICE groups postoperatively at 24 hours (7.3 vs 6.1; P = .315), 3 days (6.1 vs 6.6; P = .698), 7 days (6.6 vs 6.9; P = .670), or 14 days (7.1 vs 6.3; P = .288).

While compliance within each group utilizing the randomly assigned cold modality was similar, the usage by the CC group was consistently higher at all time points recorded. No complications or reoperations were observed in either group.

DISCUSSION

The optimal method for managing postoperative pain from an arthroplasty procedure is controversial. This prospective randomized study attempted to confirm the hypothesis that CC infers better pain control, improves quality of sleep, and decreases narcotic usage compared to ICE in the first 2 weeks after a TSA procedure. The results of this study refuted our hypothesis, demonstrating no significant difference in pain control, satisfaction, narcotic usage, or sleep quality between the CC and ICE cohorts at all time points studied.

Studies on knees and lower extremities demonstrate equivocal results for the role CC plays in providing improved postoperative pain control. Thienpont10 evaluated CC in a randomized control trial comparing plain ice packs postoperatively in patients who underwent TKA. The author found no significant difference in VAS for pain or narcotic consumption in morphine equivalents. Thienpont10 recommended that CC not be used for outpatient knee arthroplasty as it is an additional cost that does not improve pain significantly. Healy and colleagues5 reported similar results that CC did not demonstrate a difference in narcotic requirement or pain control compared to plain ice packs, as well as no difference in local postoperative swelling or wound drainage. However, a recently published randomized trial by Su and colleagues11 comparing a cryopneumatic device and ICE with static compression in patients who underwent TKA demonstrated significantly lower narcotic consumption and increased ambulation distances in the treatment group. The treatment group consumed approximately 170 mg morphine equivalents less than the control group between discharge and the 2-week postoperative visit. In addition, a significant difference was observed in the satisfaction scores in the treatment group.11 Similarly, a meta-analysis by Raynor and colleagues12 on randomized clinical trials comparing cryotherapy to a placebo group after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction showed that cryotherapy is associated with significantly lower postoperative pain (P = .02), but demonstrated no difference in postoperative drainage (P = .23) or range of motion (P = .25).

Although multiple studies have been published regarding the efficacy of cryotherapy after knee surgery, very few studies have compared CC to conventional ICE after shoulder surgery. A prospective randomized trial was performed by Singh and colleagues13 to compare CC vs no ICE in open and arthroscopic shoulder surgery patients. Both the open and arthroscopic groups receiving CC demonstrated significant reductions in pain frequency and more restful sleep at the 7-day, 14-day, and 21-day intervals compared to the control group. However, they did not compare the commercial unit to ICE. In contrast, a study by Kraeutler and colleagues8 randomized 46 patients to receive either CC or ICE in the setting of arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Although no significant difference was observed in morphine equivalent dosage between the 2 groups, the CC group used more pain medication on every postoperative day during the first week after surgery. They found no difference between the 2 groups with regards to narcotic consumption or pain scores. The results of this study mirror those by Kraeutler and colleagues,8 demonstrating no difference in pain scores, sleep quality, or narcotic consumption.

Continue to: With rising costs in the US...

With rising costs in the US healthcare system, a great deal of interest has developed in the application of value-based principles to healthcare. Value can be defined as a gain in benefits over the costs expended.14 The average cost for a commercial CC unit used in this study was $260. A pack of ICE is a nominal cost. Based on the results of this study, the cost of the commercial CC device may not be justified when compared to the cost of an ice pack.

The major strengths of this study are the randomized design and multiple data points during the early postoperative period. However, there are several limitations. First, we did not objectively measure compliance of either therapy and relied only on a patient survey. Usage of the commercial CC unit in hours decreased over half between days 3 and 14. This occurred despite training on the application and specific instructions. We believe this reflects “real-world” usage, but it is possible that compliance affected our results. Second, all patients in this study had a single-shot interscalene block. While this is standard at our institution, it is possible that either CC or ICE would have a more significant effect in the absence of an interscalene block. Finally, we did not evaluate final outcomes in this study and therefore cannot determine if the final outcome was different between the 2 groups. Our goal was simply to evaluate the first 2 weeks following surgery, as this is the most painful period following TSA.

CONCLUSION

There was no difference between CC and ICE in terms of pain control, quality of sleep, patient satisfaction, or narcotic consumption following TSA. CC may offer convenience advantages, but the increased cost associated with this type of unit may not be justified.

1. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/jbjs.j.01994.

2. Stalman A, Berglund L, Dungnerc E, Arner P, Fellander-Tsai L. Temperature sensitive release of prostaglandin E2 and diminished energy requirements in synovial tissue with postoperative cryotherapy: a prospective randomized study after knee arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):1961-1968. doi:10.2016/jbjs.j.01790.

3. Levy AS, Marmar E. The role of cold compression dressings in the postoperative treatment of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;297:174-178. doi:10.1097/00003086-199312000-00029.

4. Webb JM, Williams D, Ivory JP, Day S, Williamson DM. The use of cold compression dressings after total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Orthopaedics 1998;21(1):59-61.

5. Healy WL, Seidman J, Pfeifer BA, Brown DG. Cold compressive dressing after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:143-146. doi:10.1097/00003086-199402000-00019.

6. Whitelaw GP, DeMuth KA, Demos HA, Schepsis A, Jacques E. The use of Cryo/Cuff versus ice and elastic wrap in the postoperative care of knee arthroscopy patients. Am J Knee Surg. 1995;8(1):28-30.

7. Speer KP, Warren RF, Horowitz L. The efficacy of cryotherapy in the postoperative shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(1):62-68. doi:10.16/s1058-2746(96)80032-2.

8. Kraeutler MJ, Reynolds KA, Long C, McCarthy EC. Compressive cryotherapy versus ice- a prospective, randomized study on postoperative pain in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):854-859. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.004.

9. DeFranco MJ, Higgins LD, Warner JP. Subscapularis management in open shoulder surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(12):707-717. doi:10.5435/00124635-201012000-00001.

10. Thienpont E. Does advanced cryotherapy reduce pain and narcotic consumption after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3417-3423. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3810-8.

11. Su EP, Perna M, Boettner F, Mayman DJ, et al. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a cryopneumatic device on total knee arthroplasty recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):153-156. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.94B11.30832.

12. Raynor MC, Pietrobon R, Guller U, Higgins LD. Cryotherapy after ACL reconstruction- a meta analysis. J Knee Surg. 2005;18(2):123-129. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1248169.

13. Singh H, Osbahr DC, Holovacs TF, Cawley PW, Speer KP. The efficacy of continuous cryotherapy on the postoperative shoulder: a prospective randomized investigation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(6):522-525. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.118415.

14. Black EM, Higgins LD, Warner JP. Value based shoulder surgery: outcomes driven, cost-conscious care. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.se.2013.02.008.

1. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254. doi:10.2106/jbjs.j.01994.

2. Stalman A, Berglund L, Dungnerc E, Arner P, Fellander-Tsai L. Temperature sensitive release of prostaglandin E2 and diminished energy requirements in synovial tissue with postoperative cryotherapy: a prospective randomized study after knee arthroscopy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):1961-1968. doi:10.2016/jbjs.j.01790.

3. Levy AS, Marmar E. The role of cold compression dressings in the postoperative treatment of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993;297:174-178. doi:10.1097/00003086-199312000-00029.

4. Webb JM, Williams D, Ivory JP, Day S, Williamson DM. The use of cold compression dressings after total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Orthopaedics 1998;21(1):59-61.

5. Healy WL, Seidman J, Pfeifer BA, Brown DG. Cold compressive dressing after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;299:143-146. doi:10.1097/00003086-199402000-00019.

6. Whitelaw GP, DeMuth KA, Demos HA, Schepsis A, Jacques E. The use of Cryo/Cuff versus ice and elastic wrap in the postoperative care of knee arthroscopy patients. Am J Knee Surg. 1995;8(1):28-30.

7. Speer KP, Warren RF, Horowitz L. The efficacy of cryotherapy in the postoperative shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(1):62-68. doi:10.16/s1058-2746(96)80032-2.

8. Kraeutler MJ, Reynolds KA, Long C, McCarthy EC. Compressive cryotherapy versus ice- a prospective, randomized study on postoperative pain in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair or subacromial decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):854-859. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.004.

9. DeFranco MJ, Higgins LD, Warner JP. Subscapularis management in open shoulder surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(12):707-717. doi:10.5435/00124635-201012000-00001.

10. Thienpont E. Does advanced cryotherapy reduce pain and narcotic consumption after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(11):3417-3423. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3810-8.

11. Su EP, Perna M, Boettner F, Mayman DJ, et al. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a cryopneumatic device on total knee arthroplasty recovery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(11 Suppl A):153-156. doi:10.1302/0301-620x.94B11.30832.

12. Raynor MC, Pietrobon R, Guller U, Higgins LD. Cryotherapy after ACL reconstruction- a meta analysis. J Knee Surg. 2005;18(2):123-129. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1248169.

13. Singh H, Osbahr DC, Holovacs TF, Cawley PW, Speer KP. The efficacy of continuous cryotherapy on the postoperative shoulder: a prospective randomized investigation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(6):522-525. doi:10.1067/mse.2001.118415.

14. Black EM, Higgins LD, Warner JP. Value based shoulder surgery: outcomes driven, cost-conscious care. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(7):1-10. doi:10.1016/j.se.2013.02.008.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- CC has been proposed as a means of improving postoperative pain control.

- CC represents a cost typically not covered by insurances.

- No difference was noted between the 2 groups in quality of sleep, satisfaction with the cold therapy, or narcotic usage at any time interval.

- While CC may offer convenience advantages, the increased cost associated with this type of unit may not be justified.

- The mechanism for CC for pain control is poorly understood.

Ketogenic Diet Found Effective and Well Tolerated in Children With RSE

A ketogenic diet appears to be effective for children with refractory status epilepticus (RSE) suggests a small trial that included 14 patients.

- A study conducted by the Status Epilepticus Research Group from January 2011 to December 2016 found that 71% of patients with refractory status epilepticus who received a ketogenic diet experienced seizure resolution, verified by EEG findings, within 7 days of starting the regimen.

- 79% of the children with RSE were weaned off enteral infusions of the diet within 14 days.

- Possible adverse effects from the ketogenic diet occurred in 3 of 14 patients, including gastrointestinal paresis and elevated triglyceride levels.

- The regimen produced ketosis within a median of 2 days after it was initiated.

- By 3 months, 4 patients were still seizure free and 3 had fewer seizures.

pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG). Efficacy and safety of ketogenic diet for treatment of pediatric convulsive refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2018;144:1-6.

A ketogenic diet appears to be effective for children with refractory status epilepticus (RSE) suggests a small trial that included 14 patients.

- A study conducted by the Status Epilepticus Research Group from January 2011 to December 2016 found that 71% of patients with refractory status epilepticus who received a ketogenic diet experienced seizure resolution, verified by EEG findings, within 7 days of starting the regimen.

- 79% of the children with RSE were weaned off enteral infusions of the diet within 14 days.

- Possible adverse effects from the ketogenic diet occurred in 3 of 14 patients, including gastrointestinal paresis and elevated triglyceride levels.

- The regimen produced ketosis within a median of 2 days after it was initiated.

- By 3 months, 4 patients were still seizure free and 3 had fewer seizures.

pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG). Efficacy and safety of ketogenic diet for treatment of pediatric convulsive refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2018;144:1-6.

A ketogenic diet appears to be effective for children with refractory status epilepticus (RSE) suggests a small trial that included 14 patients.

- A study conducted by the Status Epilepticus Research Group from January 2011 to December 2016 found that 71% of patients with refractory status epilepticus who received a ketogenic diet experienced seizure resolution, verified by EEG findings, within 7 days of starting the regimen.

- 79% of the children with RSE were weaned off enteral infusions of the diet within 14 days.

- Possible adverse effects from the ketogenic diet occurred in 3 of 14 patients, including gastrointestinal paresis and elevated triglyceride levels.

- The regimen produced ketosis within a median of 2 days after it was initiated.

- By 3 months, 4 patients were still seizure free and 3 had fewer seizures.

pediatric Status Epilepticus Research Group (pSERG). Efficacy and safety of ketogenic diet for treatment of pediatric convulsive refractory status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2018;144:1-6.

Understanding Focal Cortical Dysplasia-Induced Epilepsy

The epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia remains a major challenge, but early recognition of the disorder will allow clinicians to consider the possibility of resective surgery, which has been shown to eliminate seizures in some patients.

- A recent review of the medical literature found that most children with focal cortical dysplasia have intractable focal epilepsy.

- The epilepsy observed in patients with focal cortical dysplasia is related to activation of the mTOR pathway and altered receptor neurotransmission.

- The literature review discusses the epidemiology, natural history, and mechanisms that precipitate seizures in children with focal cortical dysplasia.

- Between 25% and 29% of children in a surgical series had focal cortical dysplasia.

Challenges in managing epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia in children. Epilepsy Res. 2018;145:1-17.

The epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia remains a major challenge, but early recognition of the disorder will allow clinicians to consider the possibility of resective surgery, which has been shown to eliminate seizures in some patients.

- A recent review of the medical literature found that most children with focal cortical dysplasia have intractable focal epilepsy.

- The epilepsy observed in patients with focal cortical dysplasia is related to activation of the mTOR pathway and altered receptor neurotransmission.

- The literature review discusses the epidemiology, natural history, and mechanisms that precipitate seizures in children with focal cortical dysplasia.

- Between 25% and 29% of children in a surgical series had focal cortical dysplasia.

Challenges in managing epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia in children. Epilepsy Res. 2018;145:1-17.

The epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia remains a major challenge, but early recognition of the disorder will allow clinicians to consider the possibility of resective surgery, which has been shown to eliminate seizures in some patients.

- A recent review of the medical literature found that most children with focal cortical dysplasia have intractable focal epilepsy.

- The epilepsy observed in patients with focal cortical dysplasia is related to activation of the mTOR pathway and altered receptor neurotransmission.

- The literature review discusses the epidemiology, natural history, and mechanisms that precipitate seizures in children with focal cortical dysplasia.

- Between 25% and 29% of children in a surgical series had focal cortical dysplasia.

Challenges in managing epilepsy associated with focal cortical dysplasia in children. Epilepsy Res. 2018;145:1-17.

Medication Patterns Changing for Pregnant Women with Epilepsy

Drug therapy for pregnant women with epilepsy has changed markedly in recent years according to analysis of data from the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study.

- MONEAD, an NIH-funded, observational, multicenter study that looked at pregnancy outcomes in mothers and their children, included women ages 14-45 years and up to 20 weeks pregnant.

- Among 351 pregnant women with epilepsy enrolled in the study, 73.8% (259) were on monotherapy and 21.9% (77) on polytherapy; 4% were not taking an antiepileptic drug.

- Lamotrigine was the most popular drug in women on monotherapy, followed by levetiracetam, carbamazepine, zonisamide, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate.

- The most common polypharmacy regimen included lamotrigine and levetiracetam.

The researchers point out that these percentages only reflect drug usage in US tertiary epilepsy centers and may not indicate usage in community practice.

MONEAD Investigator Group. Changes in antiepileptic drug-prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:10-14.

Drug therapy for pregnant women with epilepsy has changed markedly in recent years according to analysis of data from the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study.

- MONEAD, an NIH-funded, observational, multicenter study that looked at pregnancy outcomes in mothers and their children, included women ages 14-45 years and up to 20 weeks pregnant.

- Among 351 pregnant women with epilepsy enrolled in the study, 73.8% (259) were on monotherapy and 21.9% (77) on polytherapy; 4% were not taking an antiepileptic drug.

- Lamotrigine was the most popular drug in women on monotherapy, followed by levetiracetam, carbamazepine, zonisamide, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate.

- The most common polypharmacy regimen included lamotrigine and levetiracetam.

The researchers point out that these percentages only reflect drug usage in US tertiary epilepsy centers and may not indicate usage in community practice.

MONEAD Investigator Group. Changes in antiepileptic drug-prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:10-14.

Drug therapy for pregnant women with epilepsy has changed markedly in recent years according to analysis of data from the Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study.

- MONEAD, an NIH-funded, observational, multicenter study that looked at pregnancy outcomes in mothers and their children, included women ages 14-45 years and up to 20 weeks pregnant.

- Among 351 pregnant women with epilepsy enrolled in the study, 73.8% (259) were on monotherapy and 21.9% (77) on polytherapy; 4% were not taking an antiepileptic drug.

- Lamotrigine was the most popular drug in women on monotherapy, followed by levetiracetam, carbamazepine, zonisamide, oxcarbazepine, and topiramate.

- The most common polypharmacy regimen included lamotrigine and levetiracetam.

The researchers point out that these percentages only reflect drug usage in US tertiary epilepsy centers and may not indicate usage in community practice.

MONEAD Investigator Group. Changes in antiepileptic drug-prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:10-14.

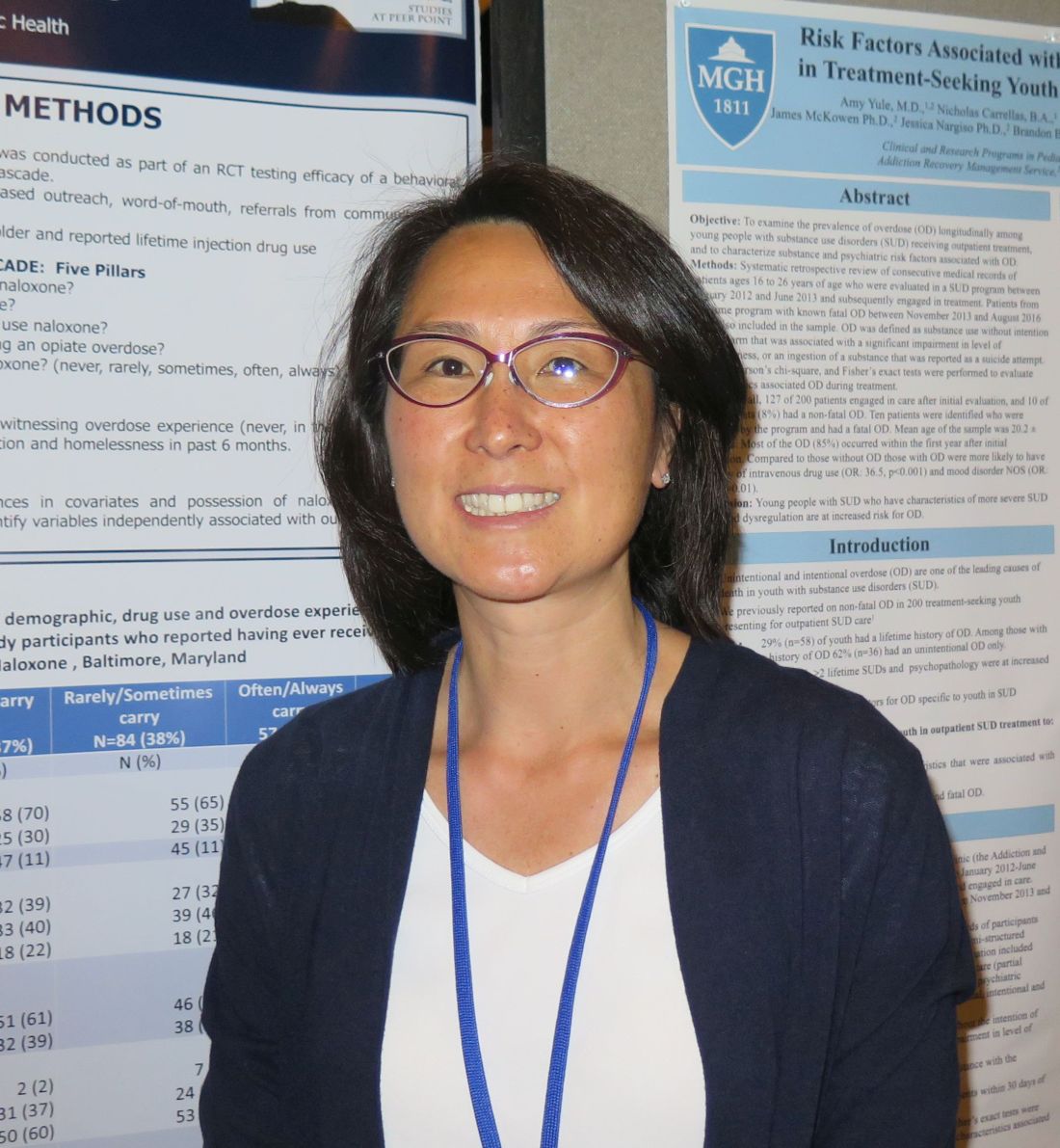

A call for ‘changing the social norms’ on naloxone

SAN DIEGO – Among individuals with a history of injection drug use, more than one-third reported never or sometimes carrying naloxone, while just one in four reported carrying with it them at all times.

Those are key findings from a survey that set out to examine gaps in the naloxone cascade in a sample of people who inject drugs.

“In order to save a life, you have to have the naloxone with you at all times,” lead study author Karin E. Tobin, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

While emerging research demonstrates the positive impact of opioid overdose education and community naloxone distribution programs to reduce opioid-related overdose deaths, opiate overdose continues to be a major cause of mortality, said Dr. Tobin, who is affiliated with the department of health behavior and society at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “We’ve made a lot of progress in convincing people that naloxone is not addictive, and that it’s not going to cause any harm,” she said. “Now, drug users aren’t afraid to ask for it. Still, we wondered: If everyone knows about naloxone and no one is embarrassed to talk about it, why are people still dying [from opioid overdoses] in Baltimore?”

She and her associates conducted a cross-sectional survey of 353 individuals aged 18 and older in Baltimore who self-reported a lifetime history of injection drug use. The data came from a baseline survey that was conducted as part of a randomized, controlled trial testing the efficacy of a behavioral intervention focused on the Hepatitis C cascade. Individuals were asked to answer questions related to the five steps of the naloxone cascade: awareness (have you ever heard about naloxone?), access (have you ever received naloxone?), training (have you ever been trained to use naloxone?), use (have you ever used naloxone during an opiate overdose?), and possession (how often do you carry naloxone?)

More than half of the survey respondents (65%) were male; mean age was 47 years. For the previous 6 months, more than half of the sample reported the use of crack (64%), heroin (74%), and other injectable drugs (57%), while 90% reported having ever witnessed an overdose – 59% in the prior year alone. Dr. Tobin and her associates found that 90% of respondents had heard about naloxone, 69% had received it, and 60% had been trained to use it. In addition, 37% reported never carrying naloxone, 38% sometimes carried it, 33% said they had used naloxone at some point, and 25% said they always carried it with them.

On multinomial regression analysis, the researchers found that carrying naloxone often or always was significantly associated with the following variables: female sex (odds ratio, 2.77), having ever witnessed an overdose (OR, 1.84), having injected in the past 12 months (OR, 1.75), and having ever used naloxone during an overdose (OR, 4.33). The latter finding is especially important, “because it means that we just have to let people practice using it,” said Dr. Tobin, who noted that more research is needed to understand reasons why injection drug users do not always carry naloxone. “We need to start changing the social norms about carrying naloxone. You never know when it will be useful.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse supported the study. Dr. Tobin reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Among individuals with a history of injection drug use, more than one-third reported never or sometimes carrying naloxone, while just one in four reported carrying with it them at all times.

Those are key findings from a survey that set out to examine gaps in the naloxone cascade in a sample of people who inject drugs.

“In order to save a life, you have to have the naloxone with you at all times,” lead study author Karin E. Tobin, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

While emerging research demonstrates the positive impact of opioid overdose education and community naloxone distribution programs to reduce opioid-related overdose deaths, opiate overdose continues to be a major cause of mortality, said Dr. Tobin, who is affiliated with the department of health behavior and society at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “We’ve made a lot of progress in convincing people that naloxone is not addictive, and that it’s not going to cause any harm,” she said. “Now, drug users aren’t afraid to ask for it. Still, we wondered: If everyone knows about naloxone and no one is embarrassed to talk about it, why are people still dying [from opioid overdoses] in Baltimore?”

She and her associates conducted a cross-sectional survey of 353 individuals aged 18 and older in Baltimore who self-reported a lifetime history of injection drug use. The data came from a baseline survey that was conducted as part of a randomized, controlled trial testing the efficacy of a behavioral intervention focused on the Hepatitis C cascade. Individuals were asked to answer questions related to the five steps of the naloxone cascade: awareness (have you ever heard about naloxone?), access (have you ever received naloxone?), training (have you ever been trained to use naloxone?), use (have you ever used naloxone during an opiate overdose?), and possession (how often do you carry naloxone?)

More than half of the survey respondents (65%) were male; mean age was 47 years. For the previous 6 months, more than half of the sample reported the use of crack (64%), heroin (74%), and other injectable drugs (57%), while 90% reported having ever witnessed an overdose – 59% in the prior year alone. Dr. Tobin and her associates found that 90% of respondents had heard about naloxone, 69% had received it, and 60% had been trained to use it. In addition, 37% reported never carrying naloxone, 38% sometimes carried it, 33% said they had used naloxone at some point, and 25% said they always carried it with them.

On multinomial regression analysis, the researchers found that carrying naloxone often or always was significantly associated with the following variables: female sex (odds ratio, 2.77), having ever witnessed an overdose (OR, 1.84), having injected in the past 12 months (OR, 1.75), and having ever used naloxone during an overdose (OR, 4.33). The latter finding is especially important, “because it means that we just have to let people practice using it,” said Dr. Tobin, who noted that more research is needed to understand reasons why injection drug users do not always carry naloxone. “We need to start changing the social norms about carrying naloxone. You never know when it will be useful.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse supported the study. Dr. Tobin reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Among individuals with a history of injection drug use, more than one-third reported never or sometimes carrying naloxone, while just one in four reported carrying with it them at all times.

Those are key findings from a survey that set out to examine gaps in the naloxone cascade in a sample of people who inject drugs.

“In order to save a life, you have to have the naloxone with you at all times,” lead study author Karin E. Tobin, PhD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

While emerging research demonstrates the positive impact of opioid overdose education and community naloxone distribution programs to reduce opioid-related overdose deaths, opiate overdose continues to be a major cause of mortality, said Dr. Tobin, who is affiliated with the department of health behavior and society at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. “We’ve made a lot of progress in convincing people that naloxone is not addictive, and that it’s not going to cause any harm,” she said. “Now, drug users aren’t afraid to ask for it. Still, we wondered: If everyone knows about naloxone and no one is embarrassed to talk about it, why are people still dying [from opioid overdoses] in Baltimore?”