User login

Factor IX therapy seems safe, effective in young kids

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA—The recombinant factor IX product trenonacog alfa appears safe and effective for previously treated patients with hemophilia B who are younger than 12 years of age, according to researchers.

The team conducted a pooled analysis of 2 studies, which included a total of 12 patients.

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was low among patients who received trenonacog alfa as prophylaxis.

Among all patients, 72% of bleeding episodes were resolved with a single infusion of trenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed factor IX inhibitors, and treatment-related adverse events consisted of fever and hyperhidrosis.

These results were presented in a poster at the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society 2017 Scientific Symposium.

The research was conducted by employees of Aptevo Therapeutics, the company marketing trenonacog alfa as IXINITY®. The poster is available on the company’s website.

The researchers conducted a pooled analysis of 2 prospective, non-randomized studies of 12 children with hemophilia B under the age of 12.

The patients’ median age was 9.5 (range, 2-11). All patients were male. Half were Asian, 3 were white, 2 were Pacific Islanders, and 1 belonged to an “other” racial/ethnic group.

Eleven patients received trenonacog alfa as prophylaxis, and 1 patient received the treatment on demand.

Among the patients on prophylaxis, the median number of exposure days was 254 (range, 111-404), and the median dose per infusion was 75.3 IU/kg (range, 25.3-111.0).

For the patients on prophylaxis, the median number of bleeding episodes was 1.0 (range, 0-11), and the median ABR was 0.3 (range, 0-4.0). Two patients had no bleeding episodes.

The patient who received trenonacog alfa on demand had 23 bleeding episodes and an ABR of 11.1.

There were a total of 61 bleeding episodes in this study. Most (72%, n=44) resolved after 1 infusion of trenonacog alfa, and 10% (n=6) resolved without any infusions.

Eight percent of the bleeding episodes (n=5) required 2 infusions of trenonacog alfa, and 10% (n=6) required 3, 4, or 5 infusions.

Adverse events thought to be related to trenonacog alfa were hyperhidrosis and fever in 1 patient, and hyperhidrosis in another patient. ![]()

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA—The recombinant factor IX product trenonacog alfa appears safe and effective for previously treated patients with hemophilia B who are younger than 12 years of age, according to researchers.

The team conducted a pooled analysis of 2 studies, which included a total of 12 patients.

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was low among patients who received trenonacog alfa as prophylaxis.

Among all patients, 72% of bleeding episodes were resolved with a single infusion of trenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed factor IX inhibitors, and treatment-related adverse events consisted of fever and hyperhidrosis.

These results were presented in a poster at the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society 2017 Scientific Symposium.

The research was conducted by employees of Aptevo Therapeutics, the company marketing trenonacog alfa as IXINITY®. The poster is available on the company’s website.

The researchers conducted a pooled analysis of 2 prospective, non-randomized studies of 12 children with hemophilia B under the age of 12.

The patients’ median age was 9.5 (range, 2-11). All patients were male. Half were Asian, 3 were white, 2 were Pacific Islanders, and 1 belonged to an “other” racial/ethnic group.

Eleven patients received trenonacog alfa as prophylaxis, and 1 patient received the treatment on demand.

Among the patients on prophylaxis, the median number of exposure days was 254 (range, 111-404), and the median dose per infusion was 75.3 IU/kg (range, 25.3-111.0).

For the patients on prophylaxis, the median number of bleeding episodes was 1.0 (range, 0-11), and the median ABR was 0.3 (range, 0-4.0). Two patients had no bleeding episodes.

The patient who received trenonacog alfa on demand had 23 bleeding episodes and an ABR of 11.1.

There were a total of 61 bleeding episodes in this study. Most (72%, n=44) resolved after 1 infusion of trenonacog alfa, and 10% (n=6) resolved without any infusions.

Eight percent of the bleeding episodes (n=5) required 2 infusions of trenonacog alfa, and 10% (n=6) required 3, 4, or 5 infusions.

Adverse events thought to be related to trenonacog alfa were hyperhidrosis and fever in 1 patient, and hyperhidrosis in another patient. ![]()

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA—The recombinant factor IX product trenonacog alfa appears safe and effective for previously treated patients with hemophilia B who are younger than 12 years of age, according to researchers.

The team conducted a pooled analysis of 2 studies, which included a total of 12 patients.

The median annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was low among patients who received trenonacog alfa as prophylaxis.

Among all patients, 72% of bleeding episodes were resolved with a single infusion of trenonacog alfa.

None of the patients developed factor IX inhibitors, and treatment-related adverse events consisted of fever and hyperhidrosis.

These results were presented in a poster at the Hemostasis and Thrombosis Research Society 2017 Scientific Symposium.

The research was conducted by employees of Aptevo Therapeutics, the company marketing trenonacog alfa as IXINITY®. The poster is available on the company’s website.

The researchers conducted a pooled analysis of 2 prospective, non-randomized studies of 12 children with hemophilia B under the age of 12.

The patients’ median age was 9.5 (range, 2-11). All patients were male. Half were Asian, 3 were white, 2 were Pacific Islanders, and 1 belonged to an “other” racial/ethnic group.

Eleven patients received trenonacog alfa as prophylaxis, and 1 patient received the treatment on demand.

Among the patients on prophylaxis, the median number of exposure days was 254 (range, 111-404), and the median dose per infusion was 75.3 IU/kg (range, 25.3-111.0).

For the patients on prophylaxis, the median number of bleeding episodes was 1.0 (range, 0-11), and the median ABR was 0.3 (range, 0-4.0). Two patients had no bleeding episodes.

The patient who received trenonacog alfa on demand had 23 bleeding episodes and an ABR of 11.1.

There were a total of 61 bleeding episodes in this study. Most (72%, n=44) resolved after 1 infusion of trenonacog alfa, and 10% (n=6) resolved without any infusions.

Eight percent of the bleeding episodes (n=5) required 2 infusions of trenonacog alfa, and 10% (n=6) required 3, 4, or 5 infusions.

Adverse events thought to be related to trenonacog alfa were hyperhidrosis and fever in 1 patient, and hyperhidrosis in another patient. ![]()

New Drugs to Treat Hyperkalemia

Q)I have heard talk about the development of new drugs to treat hyperkalemia. What is the status of these?

Hyperkalemia is a commonly seen electrolyte imbalance in clinical practice. Risks associated with moderate-to-severe hyperkalemia include potentially fatal cardiac conduction abnormalities/arrhythmias, making identification and management critical. An in-depth discussion of hyperkalemia diagnosis can be found in our March 2017 CE/CME activity (2017;27[3]:40-49).

Risk factors for hyperkalemia include excess intake or supplementation of potassium, type 2 diabetes, liver cirrhosis, congestive heart failure (CHF), and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The kidneys excrete 90% to 95% of ingested potassium, and the gut excretes the rest. Normal kidneys take six to 12 hours to excrete an acute potassium load. As kidney function decreases, risk for hyperkalemia increases.1 Hyperkalemia rates as high as 26% have been observed in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5 (glomerular filtration rate [GFR], < 60 mL/min).2

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors—including ACE inhibitors (ACEis), angiotensin-receptor blockers, and aldosterone agonists—are associated with hyperkalemia. While RAAS therapy can play an important role in the management of CKD and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the development of hyperkalemia can necessitate a dose reduction or discontinuation of these medications, limiting their therapeutic benefit. Other medications that elevate risk for hyperkalemia include NSAIDs, heparin, cyclosporine, amiloride, triamterene, and nonselective ß-blockers.1

Therapeutic options for nonurgent treatment of hyperkalemia are limited. In addition to reducing or discontinuing associated medications, strategies include use of diuretics (as appropriate), treatment of metabolic acidosis, and dietary restrictions (ie, limiting high-potassium foods).1 Pharmacologically, there has been one (less than ideal) option—until recently.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), an ion-exchange resin approved in 1958, can be used to treat hyperkalemia.3 It comes in an enema and an oral form; the former has a faster onset, but the latter is more effective, with an onset of action of one to two hours and a duration of four to six hours.1 However, each gram of SPS contains 100 g of sodium, and the typical dose of SPS is 15 g to 60 g.4 The resulting increase in sodium load can be a concern for patients with CHF, severe hypertension, or severe edema.5

Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are limited; however, one double-blind RCT investigated the effect of SPS on 33 patients with CKD and mild-to-moderate hyperkalemia (potassium level, 5 mEq/L to 5.9 mEq/L). The researchers found that patients who took 30 g/d of SPS for seven days experienced a 73% reduction in serum potassium, compared with a 38% reduction in patients who took a placebo. Of note, more gastrointestinal issues were observed in the SPS group.6

Additionally, a retrospective chart review of 14 patients with CKD and heart disease found low-dose SPS to be safe and effective when used as a secondary measure for hyperkalemia prevention in those taking RAAS therapy.7 However, a systematic review found that SPS use with and without concurrent sorbitol may be associated with serious and fatal gastrointestinal injuries.8 In 2011, the FDA issued a black box warning regarding increased risk for intestinal necrosis when SPS is used with sorbitol.9 In 2015, the FDA recommended separating SPS from other oral medications by at least six hours, due to its potential to bind with other medications.10

Patiromer, a new potassium binder, was approved by the FDA in 2015. This sodium-free, nonabsorbed, spherical polymer uses calcium as the exchange cation to bind potassium in the gastrointestinal tract. Its onset of action is seven hours, with a 24-hour duration of action. It is not approved for emergency use. There are no renal dosing adjustment considerations with patiromer.

In RCTs, patiromer has been associated with a significant reduction in serum potassium in patients with CKD (with or without diabetes) taking RAAS therapy. The starting dose is 8.4 g/d mixed with water, taken with food; this can be increased by 8.4 g each week as needed, to a maximum dosage of 25.2 g/d. Patiromer binds between 8.5 mEq to 8.8 mEq of potassium per gram of polymer.

The original approval included a black box warning to take patiromer six hours before and after other medications, due to concern for binding with certain medications. However, after an additional study in 2016, the FDA removed this warning and approved a change in administration to three hours before and after taking other medications.

Use of patiromer is not advised in those with severe constipation, bowel obstruction/impaction, or allergies to any of its components.11 Adverse reactions associated with patiromer include constipation (which generally improves with time), hypomagnesemia, diarrhea, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and flatulence. A 52-week RCT of 304 patients with CKD on RAAS found the most common adverse event to be mild-to-moderate constipation (6.3% of patients), with two patients discontinuing therapy as a result.4 In clinical trials, 9% of patients developed hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium value, < 1.4 mg/dL). It is recommended that serum magnesium levels be monitored and supplementation offered, when appropriate.11

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) is among the potassium-lowering medications on the horizon. In 2016, the FDA accepted a new drug application for this insoluble, unabsorbed cation exchanger that also works in the GI tract and uses sodium and hydrogen as exchange cations.12

For now, however, dietary education remains a mainstay of treatment for patients with elevated serum potassium levels. It is particularly important to inform your patients that many salt substitutes and low-sodium products contain potassium chloride. They should therefore exercise caution when incorporating sodium-reducing components into their diet. —CS

Cynthia Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Gilbert S, Weiner D, Gipson D, eds; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

2. Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1156-1162.

3. Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol: a preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111-115.

4. Dunn JD, Benton WW, Orozco-Torrentera E, Adamson RT. The burden of hyperkalemia in patients with cardiovascular and renal disease. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(15 suppl): s307-s315.

5. Li L, Harrison SD, Cope MJ, et al. Mechanism of action and pharmacology of patiromer, a nonabsorbed cross-linked polymer that lowers serum potassium concentration in patients with hyperkalemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2016;21(5):456-465.

6. Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for the treatment of mild hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 10(12):2136-2142.

7. Chernin G, Gal-Oz A, Ben-Assa E, et al. Secondary prevention of hyperkalemia with sodium polystyrene sulfonate in cardiac and kidney patients on renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition therapy. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(1):32-36.

8. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, et al. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):264.e9-e24.

9. FDA. Safety warning: Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) powder. www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm186845.htm. Accessed February 15, 2017.

10. FDA. FDA drug safety communication: FDA required drug interaction studies with potassium-lowering drug Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm468035.htm. Accessed March 1, 2017.

11. Veltassa® (patiromer) [package insert]. Redwood City, CA: Relypsa, Inc; 2016. www.veltassa.com/pi.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2017.

12. AstraZeneca. FDA accepts for review New Drug Application for sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) for the treatment of hyperkalaemia. www.astrazeneca.com/investor-relations/Stock-exchange-announcements/fda-accepts-for-review-new-drug-application-for-sodium-zirconium-18102016.html. Accessed March 1, 2017.

Q)I have heard talk about the development of new drugs to treat hyperkalemia. What is the status of these?

Hyperkalemia is a commonly seen electrolyte imbalance in clinical practice. Risks associated with moderate-to-severe hyperkalemia include potentially fatal cardiac conduction abnormalities/arrhythmias, making identification and management critical. An in-depth discussion of hyperkalemia diagnosis can be found in our March 2017 CE/CME activity (2017;27[3]:40-49).

Risk factors for hyperkalemia include excess intake or supplementation of potassium, type 2 diabetes, liver cirrhosis, congestive heart failure (CHF), and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The kidneys excrete 90% to 95% of ingested potassium, and the gut excretes the rest. Normal kidneys take six to 12 hours to excrete an acute potassium load. As kidney function decreases, risk for hyperkalemia increases.1 Hyperkalemia rates as high as 26% have been observed in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5 (glomerular filtration rate [GFR], < 60 mL/min).2

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors—including ACE inhibitors (ACEis), angiotensin-receptor blockers, and aldosterone agonists—are associated with hyperkalemia. While RAAS therapy can play an important role in the management of CKD and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the development of hyperkalemia can necessitate a dose reduction or discontinuation of these medications, limiting their therapeutic benefit. Other medications that elevate risk for hyperkalemia include NSAIDs, heparin, cyclosporine, amiloride, triamterene, and nonselective ß-blockers.1

Therapeutic options for nonurgent treatment of hyperkalemia are limited. In addition to reducing or discontinuing associated medications, strategies include use of diuretics (as appropriate), treatment of metabolic acidosis, and dietary restrictions (ie, limiting high-potassium foods).1 Pharmacologically, there has been one (less than ideal) option—until recently.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), an ion-exchange resin approved in 1958, can be used to treat hyperkalemia.3 It comes in an enema and an oral form; the former has a faster onset, but the latter is more effective, with an onset of action of one to two hours and a duration of four to six hours.1 However, each gram of SPS contains 100 g of sodium, and the typical dose of SPS is 15 g to 60 g.4 The resulting increase in sodium load can be a concern for patients with CHF, severe hypertension, or severe edema.5

Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are limited; however, one double-blind RCT investigated the effect of SPS on 33 patients with CKD and mild-to-moderate hyperkalemia (potassium level, 5 mEq/L to 5.9 mEq/L). The researchers found that patients who took 30 g/d of SPS for seven days experienced a 73% reduction in serum potassium, compared with a 38% reduction in patients who took a placebo. Of note, more gastrointestinal issues were observed in the SPS group.6

Additionally, a retrospective chart review of 14 patients with CKD and heart disease found low-dose SPS to be safe and effective when used as a secondary measure for hyperkalemia prevention in those taking RAAS therapy.7 However, a systematic review found that SPS use with and without concurrent sorbitol may be associated with serious and fatal gastrointestinal injuries.8 In 2011, the FDA issued a black box warning regarding increased risk for intestinal necrosis when SPS is used with sorbitol.9 In 2015, the FDA recommended separating SPS from other oral medications by at least six hours, due to its potential to bind with other medications.10

Patiromer, a new potassium binder, was approved by the FDA in 2015. This sodium-free, nonabsorbed, spherical polymer uses calcium as the exchange cation to bind potassium in the gastrointestinal tract. Its onset of action is seven hours, with a 24-hour duration of action. It is not approved for emergency use. There are no renal dosing adjustment considerations with patiromer.

In RCTs, patiromer has been associated with a significant reduction in serum potassium in patients with CKD (with or without diabetes) taking RAAS therapy. The starting dose is 8.4 g/d mixed with water, taken with food; this can be increased by 8.4 g each week as needed, to a maximum dosage of 25.2 g/d. Patiromer binds between 8.5 mEq to 8.8 mEq of potassium per gram of polymer.

The original approval included a black box warning to take patiromer six hours before and after other medications, due to concern for binding with certain medications. However, after an additional study in 2016, the FDA removed this warning and approved a change in administration to three hours before and after taking other medications.

Use of patiromer is not advised in those with severe constipation, bowel obstruction/impaction, or allergies to any of its components.11 Adverse reactions associated with patiromer include constipation (which generally improves with time), hypomagnesemia, diarrhea, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and flatulence. A 52-week RCT of 304 patients with CKD on RAAS found the most common adverse event to be mild-to-moderate constipation (6.3% of patients), with two patients discontinuing therapy as a result.4 In clinical trials, 9% of patients developed hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium value, < 1.4 mg/dL). It is recommended that serum magnesium levels be monitored and supplementation offered, when appropriate.11

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) is among the potassium-lowering medications on the horizon. In 2016, the FDA accepted a new drug application for this insoluble, unabsorbed cation exchanger that also works in the GI tract and uses sodium and hydrogen as exchange cations.12

For now, however, dietary education remains a mainstay of treatment for patients with elevated serum potassium levels. It is particularly important to inform your patients that many salt substitutes and low-sodium products contain potassium chloride. They should therefore exercise caution when incorporating sodium-reducing components into their diet. —CS

Cynthia Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

Q)I have heard talk about the development of new drugs to treat hyperkalemia. What is the status of these?

Hyperkalemia is a commonly seen electrolyte imbalance in clinical practice. Risks associated with moderate-to-severe hyperkalemia include potentially fatal cardiac conduction abnormalities/arrhythmias, making identification and management critical. An in-depth discussion of hyperkalemia diagnosis can be found in our March 2017 CE/CME activity (2017;27[3]:40-49).

Risk factors for hyperkalemia include excess intake or supplementation of potassium, type 2 diabetes, liver cirrhosis, congestive heart failure (CHF), and chronic kidney disease (CKD). The kidneys excrete 90% to 95% of ingested potassium, and the gut excretes the rest. Normal kidneys take six to 12 hours to excrete an acute potassium load. As kidney function decreases, risk for hyperkalemia increases.1 Hyperkalemia rates as high as 26% have been observed in patients with CKD stages 3 to 5 (glomerular filtration rate [GFR], < 60 mL/min).2

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors—including ACE inhibitors (ACEis), angiotensin-receptor blockers, and aldosterone agonists—are associated with hyperkalemia. While RAAS therapy can play an important role in the management of CKD and cardiovascular disease (CVD), the development of hyperkalemia can necessitate a dose reduction or discontinuation of these medications, limiting their therapeutic benefit. Other medications that elevate risk for hyperkalemia include NSAIDs, heparin, cyclosporine, amiloride, triamterene, and nonselective ß-blockers.1

Therapeutic options for nonurgent treatment of hyperkalemia are limited. In addition to reducing or discontinuing associated medications, strategies include use of diuretics (as appropriate), treatment of metabolic acidosis, and dietary restrictions (ie, limiting high-potassium foods).1 Pharmacologically, there has been one (less than ideal) option—until recently.

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS), an ion-exchange resin approved in 1958, can be used to treat hyperkalemia.3 It comes in an enema and an oral form; the former has a faster onset, but the latter is more effective, with an onset of action of one to two hours and a duration of four to six hours.1 However, each gram of SPS contains 100 g of sodium, and the typical dose of SPS is 15 g to 60 g.4 The resulting increase in sodium load can be a concern for patients with CHF, severe hypertension, or severe edema.5

Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are limited; however, one double-blind RCT investigated the effect of SPS on 33 patients with CKD and mild-to-moderate hyperkalemia (potassium level, 5 mEq/L to 5.9 mEq/L). The researchers found that patients who took 30 g/d of SPS for seven days experienced a 73% reduction in serum potassium, compared with a 38% reduction in patients who took a placebo. Of note, more gastrointestinal issues were observed in the SPS group.6

Additionally, a retrospective chart review of 14 patients with CKD and heart disease found low-dose SPS to be safe and effective when used as a secondary measure for hyperkalemia prevention in those taking RAAS therapy.7 However, a systematic review found that SPS use with and without concurrent sorbitol may be associated with serious and fatal gastrointestinal injuries.8 In 2011, the FDA issued a black box warning regarding increased risk for intestinal necrosis when SPS is used with sorbitol.9 In 2015, the FDA recommended separating SPS from other oral medications by at least six hours, due to its potential to bind with other medications.10

Patiromer, a new potassium binder, was approved by the FDA in 2015. This sodium-free, nonabsorbed, spherical polymer uses calcium as the exchange cation to bind potassium in the gastrointestinal tract. Its onset of action is seven hours, with a 24-hour duration of action. It is not approved for emergency use. There are no renal dosing adjustment considerations with patiromer.

In RCTs, patiromer has been associated with a significant reduction in serum potassium in patients with CKD (with or without diabetes) taking RAAS therapy. The starting dose is 8.4 g/d mixed with water, taken with food; this can be increased by 8.4 g each week as needed, to a maximum dosage of 25.2 g/d. Patiromer binds between 8.5 mEq to 8.8 mEq of potassium per gram of polymer.

The original approval included a black box warning to take patiromer six hours before and after other medications, due to concern for binding with certain medications. However, after an additional study in 2016, the FDA removed this warning and approved a change in administration to three hours before and after taking other medications.

Use of patiromer is not advised in those with severe constipation, bowel obstruction/impaction, or allergies to any of its components.11 Adverse reactions associated with patiromer include constipation (which generally improves with time), hypomagnesemia, diarrhea, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and flatulence. A 52-week RCT of 304 patients with CKD on RAAS found the most common adverse event to be mild-to-moderate constipation (6.3% of patients), with two patients discontinuing therapy as a result.4 In clinical trials, 9% of patients developed hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium value, < 1.4 mg/dL). It is recommended that serum magnesium levels be monitored and supplementation offered, when appropriate.11

Sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) is among the potassium-lowering medications on the horizon. In 2016, the FDA accepted a new drug application for this insoluble, unabsorbed cation exchanger that also works in the GI tract and uses sodium and hydrogen as exchange cations.12

For now, however, dietary education remains a mainstay of treatment for patients with elevated serum potassium levels. It is particularly important to inform your patients that many salt substitutes and low-sodium products contain potassium chloride. They should therefore exercise caution when incorporating sodium-reducing components into their diet. —CS

Cynthia Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, APRN, FNP-BC

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Gilbert S, Weiner D, Gipson D, eds; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

2. Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1156-1162.

3. Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol: a preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111-115.

4. Dunn JD, Benton WW, Orozco-Torrentera E, Adamson RT. The burden of hyperkalemia in patients with cardiovascular and renal disease. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(15 suppl): s307-s315.

5. Li L, Harrison SD, Cope MJ, et al. Mechanism of action and pharmacology of patiromer, a nonabsorbed cross-linked polymer that lowers serum potassium concentration in patients with hyperkalemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2016;21(5):456-465.

6. Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for the treatment of mild hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 10(12):2136-2142.

7. Chernin G, Gal-Oz A, Ben-Assa E, et al. Secondary prevention of hyperkalemia with sodium polystyrene sulfonate in cardiac and kidney patients on renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition therapy. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(1):32-36.

8. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, et al. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):264.e9-e24.

9. FDA. Safety warning: Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) powder. www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm186845.htm. Accessed February 15, 2017.

10. FDA. FDA drug safety communication: FDA required drug interaction studies with potassium-lowering drug Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm468035.htm. Accessed March 1, 2017.

11. Veltassa® (patiromer) [package insert]. Redwood City, CA: Relypsa, Inc; 2016. www.veltassa.com/pi.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2017.

12. AstraZeneca. FDA accepts for review New Drug Application for sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) for the treatment of hyperkalaemia. www.astrazeneca.com/investor-relations/Stock-exchange-announcements/fda-accepts-for-review-new-drug-application-for-sodium-zirconium-18102016.html. Accessed March 1, 2017.

1. Gilbert S, Weiner D, Gipson D, eds; National Kidney Foundation. Primer on Kidney Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

2. Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, et al. The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(12):1156-1162.

3. Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR. Treatment of the oliguric patient with a new sodium-exchange resin and sorbitol: a preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1961;264:111-115.

4. Dunn JD, Benton WW, Orozco-Torrentera E, Adamson RT. The burden of hyperkalemia in patients with cardiovascular and renal disease. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(15 suppl): s307-s315.

5. Li L, Harrison SD, Cope MJ, et al. Mechanism of action and pharmacology of patiromer, a nonabsorbed cross-linked polymer that lowers serum potassium concentration in patients with hyperkalemia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2016;21(5):456-465.

6. Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of sodium polystyrene sulfonate for the treatment of mild hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 10(12):2136-2142.

7. Chernin G, Gal-Oz A, Ben-Assa E, et al. Secondary prevention of hyperkalemia with sodium polystyrene sulfonate in cardiac and kidney patients on renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibition therapy. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35(1):32-36.

8. Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, et al. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126(3):264.e9-e24.

9. FDA. Safety warning: Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) powder. www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/ucm186845.htm. Accessed February 15, 2017.

10. FDA. FDA drug safety communication: FDA required drug interaction studies with potassium-lowering drug Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate). www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm468035.htm. Accessed March 1, 2017.

11. Veltassa® (patiromer) [package insert]. Redwood City, CA: Relypsa, Inc; 2016. www.veltassa.com/pi.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2017.

12. AstraZeneca. FDA accepts for review New Drug Application for sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (ZS-9) for the treatment of hyperkalaemia. www.astrazeneca.com/investor-relations/Stock-exchange-announcements/fda-accepts-for-review-new-drug-application-for-sodium-zirconium-18102016.html. Accessed March 1, 2017.

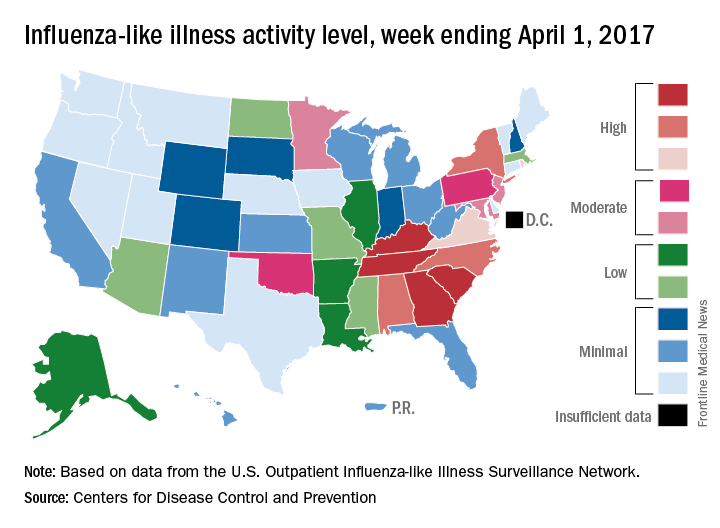

Decline in U.S. flu activity puts end of season within sight

Outpatient visits for influenza were down again in the United States during the week ending April 1, and the number of states at the highest level of flu activity dropped from seven to four, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.9% for the week ending April 1, compared with 3.2% the week before, the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network reported. The national baseline level is 2.2%.

There were 7 flu-related pediatric deaths reported for the week ending April 1 – six of the deaths occurred in previous weeks – which brings the total for the 2016-2017 season to 68, the CDC said. The largest share of those deaths by age group has been among 5- to 11-year-olds (36.8%), followed by those aged 12-17 years (26.5%), 6-23 months (16.2%), 2-4 years (14.7%), and 0-5 months (5.9%).

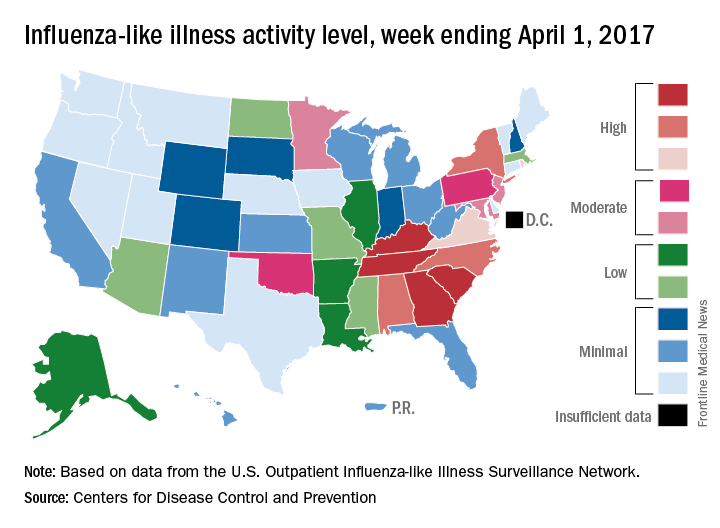

Outpatient visits for influenza were down again in the United States during the week ending April 1, and the number of states at the highest level of flu activity dropped from seven to four, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.9% for the week ending April 1, compared with 3.2% the week before, the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network reported. The national baseline level is 2.2%.

There were 7 flu-related pediatric deaths reported for the week ending April 1 – six of the deaths occurred in previous weeks – which brings the total for the 2016-2017 season to 68, the CDC said. The largest share of those deaths by age group has been among 5- to 11-year-olds (36.8%), followed by those aged 12-17 years (26.5%), 6-23 months (16.2%), 2-4 years (14.7%), and 0-5 months (5.9%).

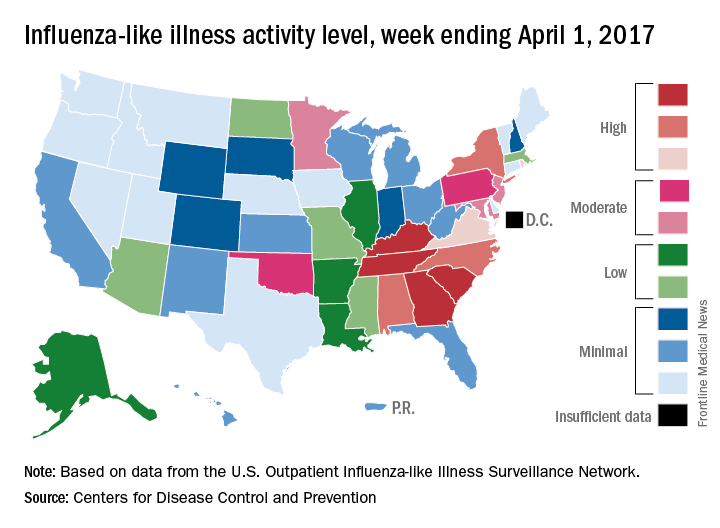

Outpatient visits for influenza were down again in the United States during the week ending April 1, and the number of states at the highest level of flu activity dropped from seven to four, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The national proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 2.9% for the week ending April 1, compared with 3.2% the week before, the CDC’s Outpatient Influenza-like Illness Surveillance Network reported. The national baseline level is 2.2%.

There were 7 flu-related pediatric deaths reported for the week ending April 1 – six of the deaths occurred in previous weeks – which brings the total for the 2016-2017 season to 68, the CDC said. The largest share of those deaths by age group has been among 5- to 11-year-olds (36.8%), followed by those aged 12-17 years (26.5%), 6-23 months (16.2%), 2-4 years (14.7%), and 0-5 months (5.9%).

Death watch intensifies for HDL-based interventions

WASHINGTON – Is it finally time to give up on HDL cholesterol–based interventions to treat atherosclerotic disease?

The approach “is on life support,” admitted Stephen J. Nicholls, MD, a long-time leader in the field who has reported results from a series of studies during the past 10 or so years that tested various approaches to juicing HDL cholesterol activity in patients, only to see each and every candidate intervention result in an inability to budge clinical outcomes.

The latest disappointment he reported was for CER-001, an engineered HDL mimetic agent. In a placebo-controlled international study, CARAT (CER-001 Atherosclerosis Regression ACS Trial), with 301 randomized patients and 272 completers, 10 weekly infusions of CER-001 over the course of 9 weeks failed to produce discernible incremental regression of atherosclerotic plaque volume, compared with standard care measured by serial examination using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), Dr. Nicholls reported. The absence of any detectable benefit “suggests that this is not a promising strategy,” he said during his report at the meeting.

Enthusiasm for HDL cholesterol–based interventions dates to 2003, when an IVUS study of a first-generation HDL mimetic agent, ETC-216, showed an apparent ability to produce regression of coronary atheroma after five infusions over a 2-week period, compared with placebo-treated patients (JAMA. 2003 Nov 5;290[17]:2292-300). But the successor compound to this agent, MDCO-216, flamed out in an IVUS study with 113 completing patients that Dr. Nicholls reported at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in November 2016.

Also lying dead on the trial trail during past years are several cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibitors – torcetrapib, dalcetrapib and evacetrapib – as well as other agents that Dr. Nicholls described in a recent review (Arch Med Sci. 2016 Oct 24;12[6]:1302-7).

“HDL wouldn’t be the first risk factor we’ve seen that is not a modifiable target. Homocysteine is a really good example” of another atherosclerotic disease risk that’s proven immune to intervention, Dr. Nicholls said in an interview at the meeting. “Ultimately we’ll come to a point when the enthusiasm [for potential HDL interventions] will wane, but we’re not quite there yet.”

“There are other players in the HDL field” that remain viable, said Dr. Nicholls, most notably CSL112, plasma-derived apoA1 – the primary functional part of HDL cholesterol – that’s infused into patients to boost HDL activity. Results from a phase II study reported in November 2016 showed it increased cholesterol efflux (Circulation 2016 Nov; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025687), and is now the subject of additional phase II testing. “But with every negative trial, it will get harder and harder [to fund new HDL research], and we’ll look for other targets,” he said.

One promising alternative target is triglycerides. “HDL has received more attention than triglycerides over the past decade, but I think that will start to change as HDL can’t deliver,” predicted Dr. Nicholls, professor of cardiology at the South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute in Adelaide.

Understandably “financial support is the biggest issue. Do companies and investors still believe in the [HDL] dream?” Dr. Nicholls said that, objectively, looking at the HDL research record should definitely give investors pause before they sink money into new compounds for HDL intervention.

“If I was sitting at the drawing board now, would HDL be the risk factor I’d target? Probably not,” he concluded.

Dr. Nicholls received research support from Cerenis, the company that is developing CER-001, and he has received honoraria and research support from several other companies. Dr. Bhatt has received research support from several drug companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

WASHINGTON – Is it finally time to give up on HDL cholesterol–based interventions to treat atherosclerotic disease?

The approach “is on life support,” admitted Stephen J. Nicholls, MD, a long-time leader in the field who has reported results from a series of studies during the past 10 or so years that tested various approaches to juicing HDL cholesterol activity in patients, only to see each and every candidate intervention result in an inability to budge clinical outcomes.

The latest disappointment he reported was for CER-001, an engineered HDL mimetic agent. In a placebo-controlled international study, CARAT (CER-001 Atherosclerosis Regression ACS Trial), with 301 randomized patients and 272 completers, 10 weekly infusions of CER-001 over the course of 9 weeks failed to produce discernible incremental regression of atherosclerotic plaque volume, compared with standard care measured by serial examination using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), Dr. Nicholls reported. The absence of any detectable benefit “suggests that this is not a promising strategy,” he said during his report at the meeting.

Enthusiasm for HDL cholesterol–based interventions dates to 2003, when an IVUS study of a first-generation HDL mimetic agent, ETC-216, showed an apparent ability to produce regression of coronary atheroma after five infusions over a 2-week period, compared with placebo-treated patients (JAMA. 2003 Nov 5;290[17]:2292-300). But the successor compound to this agent, MDCO-216, flamed out in an IVUS study with 113 completing patients that Dr. Nicholls reported at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in November 2016.

Also lying dead on the trial trail during past years are several cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibitors – torcetrapib, dalcetrapib and evacetrapib – as well as other agents that Dr. Nicholls described in a recent review (Arch Med Sci. 2016 Oct 24;12[6]:1302-7).

“HDL wouldn’t be the first risk factor we’ve seen that is not a modifiable target. Homocysteine is a really good example” of another atherosclerotic disease risk that’s proven immune to intervention, Dr. Nicholls said in an interview at the meeting. “Ultimately we’ll come to a point when the enthusiasm [for potential HDL interventions] will wane, but we’re not quite there yet.”

“There are other players in the HDL field” that remain viable, said Dr. Nicholls, most notably CSL112, plasma-derived apoA1 – the primary functional part of HDL cholesterol – that’s infused into patients to boost HDL activity. Results from a phase II study reported in November 2016 showed it increased cholesterol efflux (Circulation 2016 Nov; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025687), and is now the subject of additional phase II testing. “But with every negative trial, it will get harder and harder [to fund new HDL research], and we’ll look for other targets,” he said.

One promising alternative target is triglycerides. “HDL has received more attention than triglycerides over the past decade, but I think that will start to change as HDL can’t deliver,” predicted Dr. Nicholls, professor of cardiology at the South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute in Adelaide.

Understandably “financial support is the biggest issue. Do companies and investors still believe in the [HDL] dream?” Dr. Nicholls said that, objectively, looking at the HDL research record should definitely give investors pause before they sink money into new compounds for HDL intervention.

“If I was sitting at the drawing board now, would HDL be the risk factor I’d target? Probably not,” he concluded.

Dr. Nicholls received research support from Cerenis, the company that is developing CER-001, and he has received honoraria and research support from several other companies. Dr. Bhatt has received research support from several drug companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

WASHINGTON – Is it finally time to give up on HDL cholesterol–based interventions to treat atherosclerotic disease?

The approach “is on life support,” admitted Stephen J. Nicholls, MD, a long-time leader in the field who has reported results from a series of studies during the past 10 or so years that tested various approaches to juicing HDL cholesterol activity in patients, only to see each and every candidate intervention result in an inability to budge clinical outcomes.

The latest disappointment he reported was for CER-001, an engineered HDL mimetic agent. In a placebo-controlled international study, CARAT (CER-001 Atherosclerosis Regression ACS Trial), with 301 randomized patients and 272 completers, 10 weekly infusions of CER-001 over the course of 9 weeks failed to produce discernible incremental regression of atherosclerotic plaque volume, compared with standard care measured by serial examination using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), Dr. Nicholls reported. The absence of any detectable benefit “suggests that this is not a promising strategy,” he said during his report at the meeting.

Enthusiasm for HDL cholesterol–based interventions dates to 2003, when an IVUS study of a first-generation HDL mimetic agent, ETC-216, showed an apparent ability to produce regression of coronary atheroma after five infusions over a 2-week period, compared with placebo-treated patients (JAMA. 2003 Nov 5;290[17]:2292-300). But the successor compound to this agent, MDCO-216, flamed out in an IVUS study with 113 completing patients that Dr. Nicholls reported at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in November 2016.

Also lying dead on the trial trail during past years are several cholesterol ester transfer protein inhibitors – torcetrapib, dalcetrapib and evacetrapib – as well as other agents that Dr. Nicholls described in a recent review (Arch Med Sci. 2016 Oct 24;12[6]:1302-7).

“HDL wouldn’t be the first risk factor we’ve seen that is not a modifiable target. Homocysteine is a really good example” of another atherosclerotic disease risk that’s proven immune to intervention, Dr. Nicholls said in an interview at the meeting. “Ultimately we’ll come to a point when the enthusiasm [for potential HDL interventions] will wane, but we’re not quite there yet.”

“There are other players in the HDL field” that remain viable, said Dr. Nicholls, most notably CSL112, plasma-derived apoA1 – the primary functional part of HDL cholesterol – that’s infused into patients to boost HDL activity. Results from a phase II study reported in November 2016 showed it increased cholesterol efflux (Circulation 2016 Nov; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025687), and is now the subject of additional phase II testing. “But with every negative trial, it will get harder and harder [to fund new HDL research], and we’ll look for other targets,” he said.

One promising alternative target is triglycerides. “HDL has received more attention than triglycerides over the past decade, but I think that will start to change as HDL can’t deliver,” predicted Dr. Nicholls, professor of cardiology at the South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute in Adelaide.

Understandably “financial support is the biggest issue. Do companies and investors still believe in the [HDL] dream?” Dr. Nicholls said that, objectively, looking at the HDL research record should definitely give investors pause before they sink money into new compounds for HDL intervention.

“If I was sitting at the drawing board now, would HDL be the risk factor I’d target? Probably not,” he concluded.

Dr. Nicholls received research support from Cerenis, the company that is developing CER-001, and he has received honoraria and research support from several other companies. Dr. Bhatt has received research support from several drug companies.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACC 17

MicroRNAs linked to treatment response in lupus nephritis

MELBOURNE – Researchers have identified six microRNAs that may indicate a better likelihood of response to cyclophosphamide in patients with lupus nephritis, according to a study presented at an international conference on systemic lupus erythematosus.

“MicroRNA has been shown to be important in systemic lupus in several studies, and they’ve identified several microRNA that have been shown to affect the outcome measures in patients,” said Sarfaraz Hasni, MD, director of the Lupus Clinical Research Program at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases in Bethesda, Md., who presented a poster on the study at the meeting.

The aim of this study, involving 71 patients with lupus nephritis, was to look for microRNAs associated with treatment response to cyclophosphamide.

The first stage of the study involved isolating microRNAs from kidney biopsies taken from a first cohort of 17 responders and 15 nonresponders.

Responders were patients who, after 2 years of intravenous cyclophosphamide, showed no active urinary sediments, less than five red blood cells or white blood cells in urine, and proteinuria below 1 g/24 hours.

After analyzing 300-400 microRNAs in these biopsies, the investigators identified 6 that were significantly upregulated in association with treatment outcome in both the first cohort as well as a second validation cohort of 22 responders and 17 nonresponders.

When the researchers looked at the most likely genetic targets of these microRNAs, they identified genes associated with G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation, which points to a link with cyclophosphamide efficacy, as well as associations with immunological disease and renal inflammation.

Dr. Hasni said that previous studies of microRNA had looked in the peripheral blood but suggested this may not necessarily reflect what was happening in the kidney.

The next step for researchers is to see if upregulation of these microRNAs is predictive of treatment response.

“If you are giving cyclophosphamide for 2 years, it comes with a high risk of side effects, especially in young women because there is potential for premature ovarian failure,” Dr. Hasni said in an interview. “If we can predict that this patient is not going to respond to cyclophosphamide or will not have a good outcome, we can use alternative therapy, or perhaps use more aggressive or a combination therapy approach rather than keep doing the same thing and 2 years later find out the patient is not going to respond.”

The researchers are also keen to investigate whether these same microRNAs can be isolated from serum or urine, which would reduce the need for kidney biopsy.

“The testing for microRNA is not that hard – it’s the biopsy and extracting the tissue from the biopsy... that’s obviously cumbersome and can only be done in a research setting.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

MELBOURNE – Researchers have identified six microRNAs that may indicate a better likelihood of response to cyclophosphamide in patients with lupus nephritis, according to a study presented at an international conference on systemic lupus erythematosus.

“MicroRNA has been shown to be important in systemic lupus in several studies, and they’ve identified several microRNA that have been shown to affect the outcome measures in patients,” said Sarfaraz Hasni, MD, director of the Lupus Clinical Research Program at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases in Bethesda, Md., who presented a poster on the study at the meeting.

The aim of this study, involving 71 patients with lupus nephritis, was to look for microRNAs associated with treatment response to cyclophosphamide.

The first stage of the study involved isolating microRNAs from kidney biopsies taken from a first cohort of 17 responders and 15 nonresponders.

Responders were patients who, after 2 years of intravenous cyclophosphamide, showed no active urinary sediments, less than five red blood cells or white blood cells in urine, and proteinuria below 1 g/24 hours.

After analyzing 300-400 microRNAs in these biopsies, the investigators identified 6 that were significantly upregulated in association with treatment outcome in both the first cohort as well as a second validation cohort of 22 responders and 17 nonresponders.

When the researchers looked at the most likely genetic targets of these microRNAs, they identified genes associated with G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation, which points to a link with cyclophosphamide efficacy, as well as associations with immunological disease and renal inflammation.

Dr. Hasni said that previous studies of microRNA had looked in the peripheral blood but suggested this may not necessarily reflect what was happening in the kidney.

The next step for researchers is to see if upregulation of these microRNAs is predictive of treatment response.

“If you are giving cyclophosphamide for 2 years, it comes with a high risk of side effects, especially in young women because there is potential for premature ovarian failure,” Dr. Hasni said in an interview. “If we can predict that this patient is not going to respond to cyclophosphamide or will not have a good outcome, we can use alternative therapy, or perhaps use more aggressive or a combination therapy approach rather than keep doing the same thing and 2 years later find out the patient is not going to respond.”

The researchers are also keen to investigate whether these same microRNAs can be isolated from serum or urine, which would reduce the need for kidney biopsy.

“The testing for microRNA is not that hard – it’s the biopsy and extracting the tissue from the biopsy... that’s obviously cumbersome and can only be done in a research setting.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

MELBOURNE – Researchers have identified six microRNAs that may indicate a better likelihood of response to cyclophosphamide in patients with lupus nephritis, according to a study presented at an international conference on systemic lupus erythematosus.

“MicroRNA has been shown to be important in systemic lupus in several studies, and they’ve identified several microRNA that have been shown to affect the outcome measures in patients,” said Sarfaraz Hasni, MD, director of the Lupus Clinical Research Program at the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases in Bethesda, Md., who presented a poster on the study at the meeting.

The aim of this study, involving 71 patients with lupus nephritis, was to look for microRNAs associated with treatment response to cyclophosphamide.

The first stage of the study involved isolating microRNAs from kidney biopsies taken from a first cohort of 17 responders and 15 nonresponders.

Responders were patients who, after 2 years of intravenous cyclophosphamide, showed no active urinary sediments, less than five red blood cells or white blood cells in urine, and proteinuria below 1 g/24 hours.

After analyzing 300-400 microRNAs in these biopsies, the investigators identified 6 that were significantly upregulated in association with treatment outcome in both the first cohort as well as a second validation cohort of 22 responders and 17 nonresponders.

When the researchers looked at the most likely genetic targets of these microRNAs, they identified genes associated with G2/M DNA damage checkpoint regulation, which points to a link with cyclophosphamide efficacy, as well as associations with immunological disease and renal inflammation.

Dr. Hasni said that previous studies of microRNA had looked in the peripheral blood but suggested this may not necessarily reflect what was happening in the kidney.

The next step for researchers is to see if upregulation of these microRNAs is predictive of treatment response.

“If you are giving cyclophosphamide for 2 years, it comes with a high risk of side effects, especially in young women because there is potential for premature ovarian failure,” Dr. Hasni said in an interview. “If we can predict that this patient is not going to respond to cyclophosphamide or will not have a good outcome, we can use alternative therapy, or perhaps use more aggressive or a combination therapy approach rather than keep doing the same thing and 2 years later find out the patient is not going to respond.”

The researchers are also keen to investigate whether these same microRNAs can be isolated from serum or urine, which would reduce the need for kidney biopsy.

“The testing for microRNA is not that hard – it’s the biopsy and extracting the tissue from the biopsy... that’s obviously cumbersome and can only be done in a research setting.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

AT LUPUS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Researchers have identified six microRNAs from kidney biopsies that are significantly upregulated in patients who respond to cyclophosphamide treatment for lupus nephritis.

Data source: Prospective cohort study in 71 patients with lupus nephritis.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Metformin linked with better survival in RCC patients with diabetes

Metformin use was associated with better survival for patients with renal cell carcinoma and diabetes in a meta-analysis, investigators report.

Yang Li, MD, and associates at Chongqing (China) Medical University, performed a pooled analysis of data from 254,329 patients with both localized and metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and found the risk of mortality was reduced in patients exposed to metformin (hazard ratio, 0.41; P less than .001).

However, there was significant heterogeneity among the eight eligible studies included in the meta-analysis, Dr. Li and associates reported (Int Urol Nephrol. 2017 Mar 7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1548-4).

In a subgroup analysis, the association held in patients with localized disease, but was not significant in those with metastatic disease.

The current meta-analysis suggests that the use of metformin could improve the survival of kidney cancer patients, particularly those with localized disease; however, further studies are needed, the investigators conclude.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

Metformin use was associated with better survival for patients with renal cell carcinoma and diabetes in a meta-analysis, investigators report.

Yang Li, MD, and associates at Chongqing (China) Medical University, performed a pooled analysis of data from 254,329 patients with both localized and metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and found the risk of mortality was reduced in patients exposed to metformin (hazard ratio, 0.41; P less than .001).

However, there was significant heterogeneity among the eight eligible studies included in the meta-analysis, Dr. Li and associates reported (Int Urol Nephrol. 2017 Mar 7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1548-4).

In a subgroup analysis, the association held in patients with localized disease, but was not significant in those with metastatic disease.

The current meta-analysis suggests that the use of metformin could improve the survival of kidney cancer patients, particularly those with localized disease; however, further studies are needed, the investigators conclude.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

Metformin use was associated with better survival for patients with renal cell carcinoma and diabetes in a meta-analysis, investigators report.

Yang Li, MD, and associates at Chongqing (China) Medical University, performed a pooled analysis of data from 254,329 patients with both localized and metastatic renal cell carcinoma, and found the risk of mortality was reduced in patients exposed to metformin (hazard ratio, 0.41; P less than .001).

However, there was significant heterogeneity among the eight eligible studies included in the meta-analysis, Dr. Li and associates reported (Int Urol Nephrol. 2017 Mar 7. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1548-4).

In a subgroup analysis, the association held in patients with localized disease, but was not significant in those with metastatic disease.

The current meta-analysis suggests that the use of metformin could improve the survival of kidney cancer patients, particularly those with localized disease; however, further studies are needed, the investigators conclude.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In a pooled analysis of data from eight studies, the risk of mortality was reduced in patients exposed to metformin (hazard ratio, 0.41; P less than .001).

Data source: A meta-analysis of eight studies including 254,329 patients with renal cell carcinoma.

Disclosures: The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

Robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of a rectovaginal endometriotic nodule

A rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE) is the most severe form of endometriosis. The gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with histologic confirmation. A review of the literature suggests that surgery improves up to 70% of symptoms with generally favorable outcomes.

In this video, we provide a general introduction to endometriosis and a discussion of disease treatment options, ranging from hormonal suppression to radical bowel resections. We also illustrate the steps in robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of an RVE nodule:

- identify the borders of the rectosigmoid

- dissect the pararectal spaces

- release the rectosigmoid from its attachment to the RVE nodule

- identify and isolate the ureter(s)

- determine the margins of the nodule

- ensure complete resection.

Excision of an RVE nodule is a technically challenging surgical procedure. Use of the robot for resection is safe and feasible when performed by a trained and experienced surgeon.

I am pleased to bring you this video, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE) is the most severe form of endometriosis. The gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with histologic confirmation. A review of the literature suggests that surgery improves up to 70% of symptoms with generally favorable outcomes.

In this video, we provide a general introduction to endometriosis and a discussion of disease treatment options, ranging from hormonal suppression to radical bowel resections. We also illustrate the steps in robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of an RVE nodule:

- identify the borders of the rectosigmoid

- dissect the pararectal spaces

- release the rectosigmoid from its attachment to the RVE nodule

- identify and isolate the ureter(s)

- determine the margins of the nodule

- ensure complete resection.

Excision of an RVE nodule is a technically challenging surgical procedure. Use of the robot for resection is safe and feasible when performed by a trained and experienced surgeon.

I am pleased to bring you this video, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

A rectovaginal endometriosis (RVE) is the most severe form of endometriosis. The gold standard for diagnosis is laparoscopy with histologic confirmation. A review of the literature suggests that surgery improves up to 70% of symptoms with generally favorable outcomes.

In this video, we provide a general introduction to endometriosis and a discussion of disease treatment options, ranging from hormonal suppression to radical bowel resections. We also illustrate the steps in robot-assisted laparoscopic excision of an RVE nodule:

- identify the borders of the rectosigmoid

- dissect the pararectal spaces

- release the rectosigmoid from its attachment to the RVE nodule

- identify and isolate the ureter(s)

- determine the margins of the nodule

- ensure complete resection.

Excision of an RVE nodule is a technically challenging surgical procedure. Use of the robot for resection is safe and feasible when performed by a trained and experienced surgeon.

I am pleased to bring you this video, and I hope that it is helpful to your practice.

>> Arnold P. Advincula, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Tapering opioids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain released in March 2016 suggests that if “patients are found to be receiving high total daily dosages of opioids, clinicians should discuss their safety concerns with the patient [and] consider tapering to a safer dosage...”

All of us who prescribe opioids have had these discussions with patients. They are frequently fraught with hand-wringing and, all-too-often, a “steeling” for battle. We may have a general sense for what these discussions are like from the provider perspective, but what are they like for patients?

Interestingly, patients had an overall low self-perceived risk of opioid overdose. Patients attributed reports of overdose to intent or risky behaviors. Patients rated the importance of treatment of current pain higher than the future potential risk of opioid use and had little faith in nonopioid pain management strategies. Patients reported fear of opioid withdrawal. They also reported the importance of social support and a healthy, trusting relationship with their provider for the facilitation of tapering. None of the patients reported switching providers who had recommended tapering. Patients who had tapered off opioids reported improved quality of life and a level of pain that was largely unchanged.

This work provides critical insight into the fears and reservations of patients facing the prospect of life on lower doses of opioids or life without them altogether. Addressing these fears directly may facilitate the discussions with patients when discussing the tapering of opioids.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain released in March 2016 suggests that if “patients are found to be receiving high total daily dosages of opioids, clinicians should discuss their safety concerns with the patient [and] consider tapering to a safer dosage...”

All of us who prescribe opioids have had these discussions with patients. They are frequently fraught with hand-wringing and, all-too-often, a “steeling” for battle. We may have a general sense for what these discussions are like from the provider perspective, but what are they like for patients?

Interestingly, patients had an overall low self-perceived risk of opioid overdose. Patients attributed reports of overdose to intent or risky behaviors. Patients rated the importance of treatment of current pain higher than the future potential risk of opioid use and had little faith in nonopioid pain management strategies. Patients reported fear of opioid withdrawal. They also reported the importance of social support and a healthy, trusting relationship with their provider for the facilitation of tapering. None of the patients reported switching providers who had recommended tapering. Patients who had tapered off opioids reported improved quality of life and a level of pain that was largely unchanged.

This work provides critical insight into the fears and reservations of patients facing the prospect of life on lower doses of opioids or life without them altogether. Addressing these fears directly may facilitate the discussions with patients when discussing the tapering of opioids.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain released in March 2016 suggests that if “patients are found to be receiving high total daily dosages of opioids, clinicians should discuss their safety concerns with the patient [and] consider tapering to a safer dosage...”

All of us who prescribe opioids have had these discussions with patients. They are frequently fraught with hand-wringing and, all-too-often, a “steeling” for battle. We may have a general sense for what these discussions are like from the provider perspective, but what are they like for patients?

Interestingly, patients had an overall low self-perceived risk of opioid overdose. Patients attributed reports of overdose to intent or risky behaviors. Patients rated the importance of treatment of current pain higher than the future potential risk of opioid use and had little faith in nonopioid pain management strategies. Patients reported fear of opioid withdrawal. They also reported the importance of social support and a healthy, trusting relationship with their provider for the facilitation of tapering. None of the patients reported switching providers who had recommended tapering. Patients who had tapered off opioids reported improved quality of life and a level of pain that was largely unchanged.

This work provides critical insight into the fears and reservations of patients facing the prospect of life on lower doses of opioids or life without them altogether. Addressing these fears directly may facilitate the discussions with patients when discussing the tapering of opioids.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine, a general internist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a diplomate of the American Board of Addiction Medicine. The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views and opinions of the Mayo Clinic. The opinions expressed in this article should not be used to diagnose or treat any medical condition nor should they be used as a substitute for medical advice from a qualified, board-certified practicing clinician. Dr. Ebbert has no relevant financial disclosures about this article.

AGA Tech Summit offers packed agenda of innovation and technology

The 2017 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, promises to provide gastroenterologists and gastrointestinal surgeons with an insider’s perspective on regulators, payors, and companies in the medtech space during its 2017 session from April 12-14 in Boston. “This year’s agenda will highlight personalized diagnostics and the impact of MACRA on gastroenterology,” said Michael L. Kochman, MD, AGAF, of Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, who is executive committee chair of the center. “The intimate nature of the meeting will allow attendees to interact with fellow gastroenterologists and GI surgeons while benefiting from sessions on critical innovation and technology issues in our field.”

Development of the program started at the 2016 conference, building on that session’s highlights, as well as on the needs and interests of its attendees and speakers. “It takes a full 9 months to lock down the topics and find appropriate presenters,” explained Dr. Kochman. “The program is continually assessed and updated to keep up with medtech developments. Handpicked faculty members include prominent leaders in the medical, medtech, and regulatory communities.”

“Two important sessions demonstrate the breadth of the meeting,” stated Dr. Kochman. “This year’s Shark Tank will cover novel developments in GI medtech.” Participating companies and entrepreneurs will have 5 minutes to present their projects to an expert panel of venture capitalists, physicians, and industry executives who make acquisition decisions. “There will also be a cutting-edge session covering liquid biopsy and personalized medicine in gastroenterology,” he added. Other highlights include presentations on “The Macroeconomics of Care Delivery: MACRA and the Change to Come” and practice and device development.

The event includes a wide range of opportunities for networking with faculty and attendees, including during the breaks on both days, a Thursday night reception, and luncheons.

Summit sessions will span critical elements affecting how innovation in the GI space evolves from concept to reality. Other topics covered will include a digestive world outlook, driving innovation adoption, research updates, quality outcomes, raising capital, medtech success in GI and metabolic diseases from 2016, opportunities and challenges in personalized medicine, and improving patient outcomes via quality efforts.

Those who cannot attend the conference can look forward to “Highlights of the 2017 AGA Tech Summit,” which will be published as a supplement to GI & Hepatology News. “There will be writers in Boston attending and capturing highlights of the event sessions,” said Dr. Kochman. “AGA members will have the opportunity to experience the salient points of the presentations through this publication.”

The AGA Tech Summit will foster innovation and technology in the field of digestive health. “The keynote speakers and presenters, along with the audience’s multiple perspectives will be something we can build on to hopefully shape the future of gastroenterology,” concluded Dr. Kochman.

Dr. Kochman disclosed that he serves as a consultant for Boston Scientific Corp. and Dark Canyon Labs.

The 2017 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, promises to provide gastroenterologists and gastrointestinal surgeons with an insider’s perspective on regulators, payors, and companies in the medtech space during its 2017 session from April 12-14 in Boston. “This year’s agenda will highlight personalized diagnostics and the impact of MACRA on gastroenterology,” said Michael L. Kochman, MD, AGAF, of Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, who is executive committee chair of the center. “The intimate nature of the meeting will allow attendees to interact with fellow gastroenterologists and GI surgeons while benefiting from sessions on critical innovation and technology issues in our field.”

Development of the program started at the 2016 conference, building on that session’s highlights, as well as on the needs and interests of its attendees and speakers. “It takes a full 9 months to lock down the topics and find appropriate presenters,” explained Dr. Kochman. “The program is continually assessed and updated to keep up with medtech developments. Handpicked faculty members include prominent leaders in the medical, medtech, and regulatory communities.”

“Two important sessions demonstrate the breadth of the meeting,” stated Dr. Kochman. “This year’s Shark Tank will cover novel developments in GI medtech.” Participating companies and entrepreneurs will have 5 minutes to present their projects to an expert panel of venture capitalists, physicians, and industry executives who make acquisition decisions. “There will also be a cutting-edge session covering liquid biopsy and personalized medicine in gastroenterology,” he added. Other highlights include presentations on “The Macroeconomics of Care Delivery: MACRA and the Change to Come” and practice and device development.

The event includes a wide range of opportunities for networking with faculty and attendees, including during the breaks on both days, a Thursday night reception, and luncheons.

Summit sessions will span critical elements affecting how innovation in the GI space evolves from concept to reality. Other topics covered will include a digestive world outlook, driving innovation adoption, research updates, quality outcomes, raising capital, medtech success in GI and metabolic diseases from 2016, opportunities and challenges in personalized medicine, and improving patient outcomes via quality efforts.

Those who cannot attend the conference can look forward to “Highlights of the 2017 AGA Tech Summit,” which will be published as a supplement to GI & Hepatology News. “There will be writers in Boston attending and capturing highlights of the event sessions,” said Dr. Kochman. “AGA members will have the opportunity to experience the salient points of the presentations through this publication.”

The AGA Tech Summit will foster innovation and technology in the field of digestive health. “The keynote speakers and presenters, along with the audience’s multiple perspectives will be something we can build on to hopefully shape the future of gastroenterology,” concluded Dr. Kochman.

Dr. Kochman disclosed that he serves as a consultant for Boston Scientific Corp. and Dark Canyon Labs.

The 2017 AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology, promises to provide gastroenterologists and gastrointestinal surgeons with an insider’s perspective on regulators, payors, and companies in the medtech space during its 2017 session from April 12-14 in Boston. “This year’s agenda will highlight personalized diagnostics and the impact of MACRA on gastroenterology,” said Michael L. Kochman, MD, AGAF, of Penn Medicine, Philadelphia, who is executive committee chair of the center. “The intimate nature of the meeting will allow attendees to interact with fellow gastroenterologists and GI surgeons while benefiting from sessions on critical innovation and technology issues in our field.”

Development of the program started at the 2016 conference, building on that session’s highlights, as well as on the needs and interests of its attendees and speakers. “It takes a full 9 months to lock down the topics and find appropriate presenters,” explained Dr. Kochman. “The program is continually assessed and updated to keep up with medtech developments. Handpicked faculty members include prominent leaders in the medical, medtech, and regulatory communities.”

“Two important sessions demonstrate the breadth of the meeting,” stated Dr. Kochman. “This year’s Shark Tank will cover novel developments in GI medtech.” Participating companies and entrepreneurs will have 5 minutes to present their projects to an expert panel of venture capitalists, physicians, and industry executives who make acquisition decisions. “There will also be a cutting-edge session covering liquid biopsy and personalized medicine in gastroenterology,” he added. Other highlights include presentations on “The Macroeconomics of Care Delivery: MACRA and the Change to Come” and practice and device development.

The event includes a wide range of opportunities for networking with faculty and attendees, including during the breaks on both days, a Thursday night reception, and luncheons.