User login

In ‘stealth move,’ Mich. refines vaccine waivers, improves rate among kids

Just 3 years ago, Michigan had the fourth-highest rate of unvaccinated kindergartners in the nation. But, when a charter school in northwestern Traverse City reported nearly two dozen cases of whooping cough and several cases of measles that November, state officials were jolted to action.

Without much fanfare – or time for opponents to respond – they abandoned the state’s relatively loose rules for getting an exemption and issued a regulation requiring families to consult personally with local public health departments before obtaining an immunization waiver.

The new rule sidestepped potential ideological firefights in the state legislature, which have plagued lawmakers in other states who are trying to crack down on vaccination waivers. The regulation had a dramatic effect. In the first year, the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services reported that the number of statewide waivers issued had plunged 35%. Today, Michigan is in the middle of the pack among vaccination rates.

“The idea was to make the process more burdensome,” said Michigan State University health policy specialist Mark Largent, PhD, who has written extensively about vaccines. “Research has shown that, if you make it more inconvenient to apply for a waiver, fewer people get them.”

Michigan’s experience demonstrates a way for governments to increase immunization rates without having to address religious or philosophical opposition to vaccines.

For many years, opposition to mandatory childhood vaccines has served as a frequent rallying point for those who see immunizations as interference with nature’s intentions, rebel against them as government meddling in family affairs, or raise concerns about their safety.

Vaccine advocates and health professionals regard these views as dangerous, noting that the drugs have dramatically lowered the number of serious childhood illnesses and that studies suggesting they are not safe have been debunked. They also note that vaccines’ proven effectiveness lies in “herd immunity” – the higher the participation rate, the greater the community’s protection against outbreaks of infectious disease.

Many states adopt strategies to curb exemptions “by making applications complicated to fill out or complete,” according to University of Georgia public policy expert W. David Bradford, PhD, who studies immunization. Some states require parents to notarize applications or have them certified by a physician before sending them in, and, “generally speaking, anything that raises the opportunity cost [of exemptions] works to some degree,” Bradford said. “Michigan took it a step further.”

Increasing the number of vaccinated kids in Michigan, which has a Republican governor and Republican majorities in both legislative houses, took a degree of political finesse.

“Health & Human Services wanted to do something, but the legislative option wasn’t there,” Dr. Largent said. Instead, Michigan decided to use a strategy he calls “inconvenience.”

Since 1978, Michigan had required schoolchildren entering kindergarten and middle school to obtain vaccination waiver certificates from county officials. “Some counties allowed you to do it over the phone; in others you mailed in a form and some even let you do it online,” Dr. Largent said. But, in studying vaccine policy across the country, he noted, “One thing is really clear – health departments that require you to go in and get the waiver have much lower rates.”

Michigan offered the perfect vehicle for introducing inconvenience into the process. The Joint Committee on Administrative Rules reviews state agency regulations and, if it takes no action, allows them to go into effect after 15 legislative days. The committee is composed of lawmakers, giving it a legislative imprimatur, but it is not the legislature itself, thus avoiding the political rancor that can accompany debate on controversial issues.

During the 2013-14 school year, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that Michigan had the fourth-highest rate of children entering kindergarten who had been exempted from vaccinations. The state Health & Human Services officials proposed a simple requirement: Parents seeking vaccine waivers must be briefed in person by a county health educator before a waiver would be granted. The joint committee approved the rule Dec. 11, 2014. It took effect Jan. 1, 2015.

“We were not aware of the rule until the day it happened,” said Suzanne Waltman, president of Michigan for Vaccine Choice, an antivaccine organization. “We thought it was a stealth move.”

The office of Gov. Rick Snyder did not respond directly to requests for comment on the political hazards of vaccine policy. Retired Republican state Sen. John Pappageorge, cochair of the administrative rules committee in 2014, voted to adopt the rule and described the procedure as a simple one designed to ensure “that implementation is in concurrence with the law.” Republican Rep. Tom McMillin, who was cochair of the committee at the time and voted against the rule, did not respond to requests for an interview.

In a look at one key metric, before 2015, about 22% of Michigan children did not get the fourth round of immunizations for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis that is required by the state. That had fallen to 15% 1 year later, slightly better than the national average.

The Traverse City outbreaks were overshadowed in the national media by a more dramatic measles outbreak in Southern California’s Disneyland, which also occurred over the 2014-15 holidays and ultimately led to 150 cases of the disease. But the states’ responses were quite different.

California’s solution was what Dr. Largent calls “eliminationism.” The state Legislature, with Democratic supermajorities, passed a measure doing away with religious and philosophical vaccine exemptions. Passage of the law triggered widespread protests among opponents of vaccines. Besides California, only West Virginia and Mississippi disallow nonmedical waivers.

Dr. Largent said a small number of children need waivers for medical reasons, usually because of allergies or immune deficiencies. Much larger numbers seek waivers for religious or philosophical reasons.

“The idea was to bring the waiver rate down,” Michigan Health & Human Services spokeswoman Angela Minicuci said. “From the perspective of the general population, vaccinations are recommended. This doesn’t take away choice. It simply ensures that people have education.”

But, Dr. Largent said most vaccine opponents are not necessarily swayed by arguments in favor of immunization. Instead, “by heightening the burden, you change some of the incentives” for obtaining waivers. “Moral claims and ideology don’t matter as much when it’s inconvenient.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Just 3 years ago, Michigan had the fourth-highest rate of unvaccinated kindergartners in the nation. But, when a charter school in northwestern Traverse City reported nearly two dozen cases of whooping cough and several cases of measles that November, state officials were jolted to action.

Without much fanfare – or time for opponents to respond – they abandoned the state’s relatively loose rules for getting an exemption and issued a regulation requiring families to consult personally with local public health departments before obtaining an immunization waiver.

The new rule sidestepped potential ideological firefights in the state legislature, which have plagued lawmakers in other states who are trying to crack down on vaccination waivers. The regulation had a dramatic effect. In the first year, the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services reported that the number of statewide waivers issued had plunged 35%. Today, Michigan is in the middle of the pack among vaccination rates.

“The idea was to make the process more burdensome,” said Michigan State University health policy specialist Mark Largent, PhD, who has written extensively about vaccines. “Research has shown that, if you make it more inconvenient to apply for a waiver, fewer people get them.”

Michigan’s experience demonstrates a way for governments to increase immunization rates without having to address religious or philosophical opposition to vaccines.

For many years, opposition to mandatory childhood vaccines has served as a frequent rallying point for those who see immunizations as interference with nature’s intentions, rebel against them as government meddling in family affairs, or raise concerns about their safety.

Vaccine advocates and health professionals regard these views as dangerous, noting that the drugs have dramatically lowered the number of serious childhood illnesses and that studies suggesting they are not safe have been debunked. They also note that vaccines’ proven effectiveness lies in “herd immunity” – the higher the participation rate, the greater the community’s protection against outbreaks of infectious disease.

Many states adopt strategies to curb exemptions “by making applications complicated to fill out or complete,” according to University of Georgia public policy expert W. David Bradford, PhD, who studies immunization. Some states require parents to notarize applications or have them certified by a physician before sending them in, and, “generally speaking, anything that raises the opportunity cost [of exemptions] works to some degree,” Bradford said. “Michigan took it a step further.”

Increasing the number of vaccinated kids in Michigan, which has a Republican governor and Republican majorities in both legislative houses, took a degree of political finesse.

“Health & Human Services wanted to do something, but the legislative option wasn’t there,” Dr. Largent said. Instead, Michigan decided to use a strategy he calls “inconvenience.”

Since 1978, Michigan had required schoolchildren entering kindergarten and middle school to obtain vaccination waiver certificates from county officials. “Some counties allowed you to do it over the phone; in others you mailed in a form and some even let you do it online,” Dr. Largent said. But, in studying vaccine policy across the country, he noted, “One thing is really clear – health departments that require you to go in and get the waiver have much lower rates.”

Michigan offered the perfect vehicle for introducing inconvenience into the process. The Joint Committee on Administrative Rules reviews state agency regulations and, if it takes no action, allows them to go into effect after 15 legislative days. The committee is composed of lawmakers, giving it a legislative imprimatur, but it is not the legislature itself, thus avoiding the political rancor that can accompany debate on controversial issues.

During the 2013-14 school year, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that Michigan had the fourth-highest rate of children entering kindergarten who had been exempted from vaccinations. The state Health & Human Services officials proposed a simple requirement: Parents seeking vaccine waivers must be briefed in person by a county health educator before a waiver would be granted. The joint committee approved the rule Dec. 11, 2014. It took effect Jan. 1, 2015.

“We were not aware of the rule until the day it happened,” said Suzanne Waltman, president of Michigan for Vaccine Choice, an antivaccine organization. “We thought it was a stealth move.”

The office of Gov. Rick Snyder did not respond directly to requests for comment on the political hazards of vaccine policy. Retired Republican state Sen. John Pappageorge, cochair of the administrative rules committee in 2014, voted to adopt the rule and described the procedure as a simple one designed to ensure “that implementation is in concurrence with the law.” Republican Rep. Tom McMillin, who was cochair of the committee at the time and voted against the rule, did not respond to requests for an interview.

In a look at one key metric, before 2015, about 22% of Michigan children did not get the fourth round of immunizations for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis that is required by the state. That had fallen to 15% 1 year later, slightly better than the national average.

The Traverse City outbreaks were overshadowed in the national media by a more dramatic measles outbreak in Southern California’s Disneyland, which also occurred over the 2014-15 holidays and ultimately led to 150 cases of the disease. But the states’ responses were quite different.

California’s solution was what Dr. Largent calls “eliminationism.” The state Legislature, with Democratic supermajorities, passed a measure doing away with religious and philosophical vaccine exemptions. Passage of the law triggered widespread protests among opponents of vaccines. Besides California, only West Virginia and Mississippi disallow nonmedical waivers.

Dr. Largent said a small number of children need waivers for medical reasons, usually because of allergies or immune deficiencies. Much larger numbers seek waivers for religious or philosophical reasons.

“The idea was to bring the waiver rate down,” Michigan Health & Human Services spokeswoman Angela Minicuci said. “From the perspective of the general population, vaccinations are recommended. This doesn’t take away choice. It simply ensures that people have education.”

But, Dr. Largent said most vaccine opponents are not necessarily swayed by arguments in favor of immunization. Instead, “by heightening the burden, you change some of the incentives” for obtaining waivers. “Moral claims and ideology don’t matter as much when it’s inconvenient.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Just 3 years ago, Michigan had the fourth-highest rate of unvaccinated kindergartners in the nation. But, when a charter school in northwestern Traverse City reported nearly two dozen cases of whooping cough and several cases of measles that November, state officials were jolted to action.

Without much fanfare – or time for opponents to respond – they abandoned the state’s relatively loose rules for getting an exemption and issued a regulation requiring families to consult personally with local public health departments before obtaining an immunization waiver.

The new rule sidestepped potential ideological firefights in the state legislature, which have plagued lawmakers in other states who are trying to crack down on vaccination waivers. The regulation had a dramatic effect. In the first year, the Michigan Department of Health & Human Services reported that the number of statewide waivers issued had plunged 35%. Today, Michigan is in the middle of the pack among vaccination rates.

“The idea was to make the process more burdensome,” said Michigan State University health policy specialist Mark Largent, PhD, who has written extensively about vaccines. “Research has shown that, if you make it more inconvenient to apply for a waiver, fewer people get them.”

Michigan’s experience demonstrates a way for governments to increase immunization rates without having to address religious or philosophical opposition to vaccines.

For many years, opposition to mandatory childhood vaccines has served as a frequent rallying point for those who see immunizations as interference with nature’s intentions, rebel against them as government meddling in family affairs, or raise concerns about their safety.

Vaccine advocates and health professionals regard these views as dangerous, noting that the drugs have dramatically lowered the number of serious childhood illnesses and that studies suggesting they are not safe have been debunked. They also note that vaccines’ proven effectiveness lies in “herd immunity” – the higher the participation rate, the greater the community’s protection against outbreaks of infectious disease.

Many states adopt strategies to curb exemptions “by making applications complicated to fill out or complete,” according to University of Georgia public policy expert W. David Bradford, PhD, who studies immunization. Some states require parents to notarize applications or have them certified by a physician before sending them in, and, “generally speaking, anything that raises the opportunity cost [of exemptions] works to some degree,” Bradford said. “Michigan took it a step further.”

Increasing the number of vaccinated kids in Michigan, which has a Republican governor and Republican majorities in both legislative houses, took a degree of political finesse.

“Health & Human Services wanted to do something, but the legislative option wasn’t there,” Dr. Largent said. Instead, Michigan decided to use a strategy he calls “inconvenience.”

Since 1978, Michigan had required schoolchildren entering kindergarten and middle school to obtain vaccination waiver certificates from county officials. “Some counties allowed you to do it over the phone; in others you mailed in a form and some even let you do it online,” Dr. Largent said. But, in studying vaccine policy across the country, he noted, “One thing is really clear – health departments that require you to go in and get the waiver have much lower rates.”

Michigan offered the perfect vehicle for introducing inconvenience into the process. The Joint Committee on Administrative Rules reviews state agency regulations and, if it takes no action, allows them to go into effect after 15 legislative days. The committee is composed of lawmakers, giving it a legislative imprimatur, but it is not the legislature itself, thus avoiding the political rancor that can accompany debate on controversial issues.

During the 2013-14 school year, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that Michigan had the fourth-highest rate of children entering kindergarten who had been exempted from vaccinations. The state Health & Human Services officials proposed a simple requirement: Parents seeking vaccine waivers must be briefed in person by a county health educator before a waiver would be granted. The joint committee approved the rule Dec. 11, 2014. It took effect Jan. 1, 2015.

“We were not aware of the rule until the day it happened,” said Suzanne Waltman, president of Michigan for Vaccine Choice, an antivaccine organization. “We thought it was a stealth move.”

The office of Gov. Rick Snyder did not respond directly to requests for comment on the political hazards of vaccine policy. Retired Republican state Sen. John Pappageorge, cochair of the administrative rules committee in 2014, voted to adopt the rule and described the procedure as a simple one designed to ensure “that implementation is in concurrence with the law.” Republican Rep. Tom McMillin, who was cochair of the committee at the time and voted against the rule, did not respond to requests for an interview.

In a look at one key metric, before 2015, about 22% of Michigan children did not get the fourth round of immunizations for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis that is required by the state. That had fallen to 15% 1 year later, slightly better than the national average.

The Traverse City outbreaks were overshadowed in the national media by a more dramatic measles outbreak in Southern California’s Disneyland, which also occurred over the 2014-15 holidays and ultimately led to 150 cases of the disease. But the states’ responses were quite different.

California’s solution was what Dr. Largent calls “eliminationism.” The state Legislature, with Democratic supermajorities, passed a measure doing away with religious and philosophical vaccine exemptions. Passage of the law triggered widespread protests among opponents of vaccines. Besides California, only West Virginia and Mississippi disallow nonmedical waivers.

Dr. Largent said a small number of children need waivers for medical reasons, usually because of allergies or immune deficiencies. Much larger numbers seek waivers for religious or philosophical reasons.

“The idea was to bring the waiver rate down,” Michigan Health & Human Services spokeswoman Angela Minicuci said. “From the perspective of the general population, vaccinations are recommended. This doesn’t take away choice. It simply ensures that people have education.”

But, Dr. Largent said most vaccine opponents are not necessarily swayed by arguments in favor of immunization. Instead, “by heightening the burden, you change some of the incentives” for obtaining waivers. “Moral claims and ideology don’t matter as much when it’s inconvenient.”

Kaiser Health News is a national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Neurologists weigh in on rising drug prices

Neurologists will tackle the issues surrounding rising prices for neurological drug treatments in a set of presentations during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Boston.

During the Contemporary Clinical Issues Plenary Session on April 24, Dennis N. Bourdette, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, will give his presentation, “High Drug Prices: The Elephant in the Clinic.”

Dr. Bourdette will also address the problem on April 26 in a session called “Section Topic Controversies,” in which he and Dennis W. Choi, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Stony Brook will offer their opinions on how “Neurologists Should Take a Position Regarding the Cost of Neurological Treatments.” Dr. Bourdette is set to illustrate how “Neurologists Should More Vocally Protest Some of the Marked Price Increases Involving Neurological Treatments,” while Dr. Choi will provide rationale for his argument on why “Neurologists Should Influence Policies that Allow Companies to Commit More Resources to R&D for Neurological Diseases While Not Allowing for Rapacious Pricing Practices.” Following the discussion, Dr. Bourdette, Dr. Choi, and session moderators will have a panel discussion on the ways in which AAN members can work most productively for the benefit of their patients.

Sure to be discussed in the series of talks is a recent AAN position paper on prescription drug prices released in March that identified three distinct drug pricing challenges:

- Massive increase in the pricing of previously low-cost generic drugs used to treat common disorders without obvious increases in cost of production or distribution.

- Massive increase in the pricing for high-priced generic and brand name drugs used to treat serious disorders that are not protected by the Orphan Drug Act.

- The high cost of new medications used to treat rare disorders as defined by the Orphan Drug Act.

Neurologists will tackle the issues surrounding rising prices for neurological drug treatments in a set of presentations during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Boston.

During the Contemporary Clinical Issues Plenary Session on April 24, Dennis N. Bourdette, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, will give his presentation, “High Drug Prices: The Elephant in the Clinic.”

Dr. Bourdette will also address the problem on April 26 in a session called “Section Topic Controversies,” in which he and Dennis W. Choi, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Stony Brook will offer their opinions on how “Neurologists Should Take a Position Regarding the Cost of Neurological Treatments.” Dr. Bourdette is set to illustrate how “Neurologists Should More Vocally Protest Some of the Marked Price Increases Involving Neurological Treatments,” while Dr. Choi will provide rationale for his argument on why “Neurologists Should Influence Policies that Allow Companies to Commit More Resources to R&D for Neurological Diseases While Not Allowing for Rapacious Pricing Practices.” Following the discussion, Dr. Bourdette, Dr. Choi, and session moderators will have a panel discussion on the ways in which AAN members can work most productively for the benefit of their patients.

Sure to be discussed in the series of talks is a recent AAN position paper on prescription drug prices released in March that identified three distinct drug pricing challenges:

- Massive increase in the pricing of previously low-cost generic drugs used to treat common disorders without obvious increases in cost of production or distribution.

- Massive increase in the pricing for high-priced generic and brand name drugs used to treat serious disorders that are not protected by the Orphan Drug Act.

- The high cost of new medications used to treat rare disorders as defined by the Orphan Drug Act.

Neurologists will tackle the issues surrounding rising prices for neurological drug treatments in a set of presentations during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Neurology in Boston.

During the Contemporary Clinical Issues Plenary Session on April 24, Dennis N. Bourdette, MD, of Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, will give his presentation, “High Drug Prices: The Elephant in the Clinic.”

Dr. Bourdette will also address the problem on April 26 in a session called “Section Topic Controversies,” in which he and Dennis W. Choi, MD, PhD, of the State University of New York at Stony Brook will offer their opinions on how “Neurologists Should Take a Position Regarding the Cost of Neurological Treatments.” Dr. Bourdette is set to illustrate how “Neurologists Should More Vocally Protest Some of the Marked Price Increases Involving Neurological Treatments,” while Dr. Choi will provide rationale for his argument on why “Neurologists Should Influence Policies that Allow Companies to Commit More Resources to R&D for Neurological Diseases While Not Allowing for Rapacious Pricing Practices.” Following the discussion, Dr. Bourdette, Dr. Choi, and session moderators will have a panel discussion on the ways in which AAN members can work most productively for the benefit of their patients.

Sure to be discussed in the series of talks is a recent AAN position paper on prescription drug prices released in March that identified three distinct drug pricing challenges:

- Massive increase in the pricing of previously low-cost generic drugs used to treat common disorders without obvious increases in cost of production or distribution.

- Massive increase in the pricing for high-priced generic and brand name drugs used to treat serious disorders that are not protected by the Orphan Drug Act.

- The high cost of new medications used to treat rare disorders as defined by the Orphan Drug Act.

Dulera inhaler linked to adrenocorticotropic suppression in small case series

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

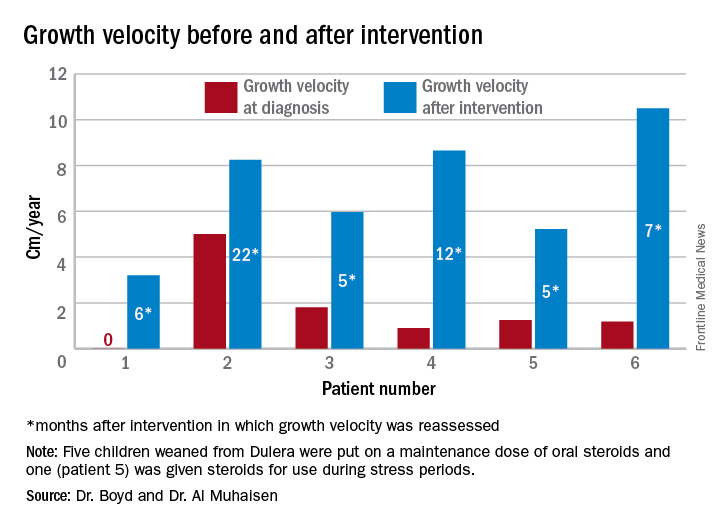

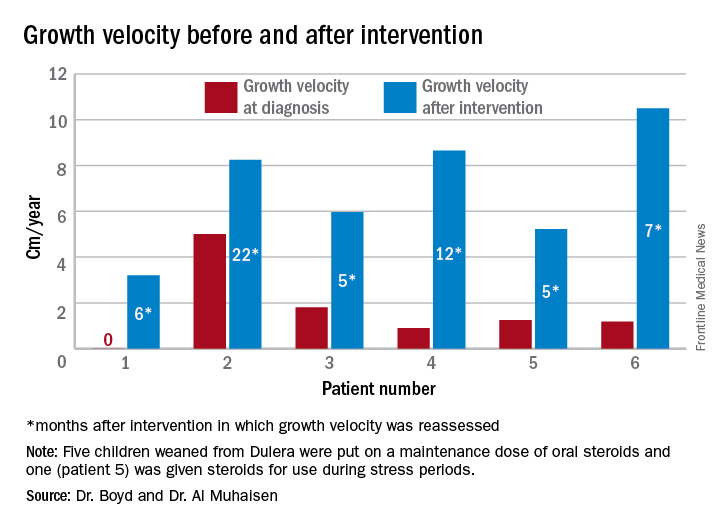

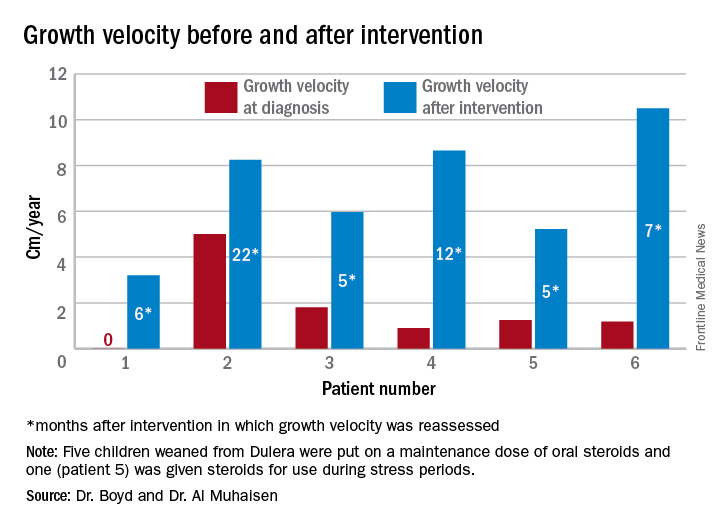

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.

“We had some back-and-forth discussions, being very frank that we thought the adrenal insufficiency was directly related to this medication and that we needed to wean it and stop it as soon as possible.”

Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.

“We had some back-and-forth discussions, being very frank that we thought the adrenal insufficiency was directly related to this medication and that we needed to wean it and stop it as soon as possible.”

Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

ORLANDO – A combination corticosteroid asthma inhaler has, for the first time, been associated with growth delay and adrenocorticotropic suppression in children.

The single-center case series is small, but the results highlight the need to regularly monitor growth and adrenal function in children using inhaled mometasone furoate/formoterol fumarate (Dulera; Merck), investigators said at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

“We are hoping to raise awareness of this risk in our pediatric endocrinology colleagues, as well as among allergists, pulmonologists, and pediatricians who treat these children,” said Fadi Al Muhaisen, MD. “These kids should be regularly screened for growth delay and adrenal insufficiency and have their growth plotted at every visit as well.”

Dulera was approved in the United States in 2010 as a maintenance therapy for chronic asthma in adults and children aged 12 years and older. Mometasone furoate is a potent corticosteroid, and formoterol fumarate is a long-acting beta2-adrenergic agonist. The prescribing information says that mometasone furoate exerts less effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis than other inhaled corticosteroids, and that adrenal suppression is unlikely to occur when used at recommended dosages. These range from a low of 100 mcg/5 mcg, two puffs daily to a maximum dose of 800 mcg/20 mcg daily.

The review involved 18 children, all of whom were seen in the endocrinology clinic for growth failure or short stature and were receiving Dulera for management of their asthma. Of these, eight (44%) had a full adrenal evaluation. Six had biochemical evidence of adrenal suppression and two had normal adrenal function. The remaining 10 patients had not undergone an adrenal evaluation. None of them were on any other inhaled corticosteroid. The six children diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency had a mean age of 9.7 years, but ranged in age from 7 to 12 years. They had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids in the preceding 6 months before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at the time of diagnosis but had been using the higher dose for the preceding 18 months. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

The six children evaluated had been using the medication for a mean of 1.3 years, although that varied widely, from just a few months to about 2 years. Only one had been on oral steroids during the 2 years before coming to the endocrinology clinic. Five were using the 200 mcg/5 mcg dose, two puffs daily; one child was taking one puff daily of 100 mcg/5 mcg at time of diagnosis, but had been using the higher dose for 18 months before that. Three were using concomitant nasal steroids.

All presented with growth failure, with bone age 1-3 years behind chronological age. One child was referred to the clinic after an emergency department visit for headache, nausea, diarrhea, and fatigue – symptoms of adrenal failure. That child had an adrenocroticotropin (ACTH) level of 10 pg/mL. Both his random peak cortisol measures after ACTH stimulation were less than 1 mcg/mL.

ACTH levels in four of the children were less than 5-6 pg/ml, with random and peak stimulated cortisols of around 1 mcg/mL. One patient had an ACTH level of 68 pg/mL, a random cortisol of less than 1 mcg/mL, and a peak stimulated cortisol of 8.7 mcg/mL.

The results were all normal in the four subjects who had repeat adrenal function evaluation after intervention. Adrenal recovery took a mean of 20 months (5-30 months).

Growth accelerated rapidly after intervention, which was either initiation of maintenance oral steroids and discontinuation of Dulera or, in one patient, after Dulera was weaned. At time of adrenal insufficiency diagnosis, four patients had grown 1-2 cm in the prior year; one had not grown at all, and one had grown about 4.5 cm. After discontinuing or weaning the medication, all experienced growth spurts: 3 cm/year in 6 months; 8 cm/year in 22 months; 6 cm/year in 5 months; 8 cm/year in 12 months; 5 cm/year in 5 months; and 10 cm/year in 7 months.

There were no exacerbations in asthma, despite discontinuing the inhaled medication, Dr. Al Muhaisen said. Changing the asthma treatment required some open discussion between the investigators and the treating pulmonologists, he noted.

“We had some back-and-forth discussions, being very frank that we thought the adrenal insufficiency was directly related to this medication and that we needed to wean it and stop it as soon as possible.”

Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

AT ENDO 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of eight children who had an adrenal workup at an endocrinology clinic, six had adrenal suppression.

Data source: The case series comprised 18 children taking Dulera who presented with growth failure.

Disclosures: Neither Dr. Al Muhaisen nor Dr. Boyd had any financial disclosures.

FDA approves Ingrezza for tardive dyskinesia in adults

The Food and Drug Administration has approved valbenazine capsules for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults.

The approval, announced April 11, came after a 6-week, placebo-controlled trial of 234 participants that compared valbenazine to placebo. At the end of the trial, those who took valbenazine experienced improvement in the severity of involuntary movements, compared with those who received placebo. As a vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitor, valbenazine works by regulating the amount of dopamine that is released into nerve cells by blocking a protein in the brain. The drug, the first to receive approval for tardive dyskinesia in adults, will be marketed as Ingrezza by Neurocrine Biosciences. Valbenazine is reportedly being studied as a treatment for Tourette syndrome in children and adolescents.

In a statement, Mitchell Mathis, MD, director of the FDA’s division of psychiatry products in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, praised the approval as “an important advance for patients suffering with tardive dyskinesia.”

Characterized by uncontrolled movement of the face and body, tardive dyskinesia is a side effect in up to 8% of patients taking typical and atypical antipsychotics. The movement disorder also can cause other debilitating problems, including difficulty with chewing, speaking, and swallowing. Some data show that in about 87% of cases, the condition is irreversible even 3 years after the inciting agent has been discontinued (Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016. 32;124-6).

“Tardive dyskinesia can be disabling and can further stigmatize patients with mental illness,” Dr. Mathis said in the statement.

The side effects of valbenazine include sleepiness and QT prolongation. The agency said the patients taking the drug should not drive, operate heavy machinery, or engage in other potentially dangerous activities. Likewise, the drug should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or in those with abnormal heartbeats associated with a prolonged QT interval, the agency said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

The Food and Drug Administration has approved valbenazine capsules for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults.

The approval, announced April 11, came after a 6-week, placebo-controlled trial of 234 participants that compared valbenazine to placebo. At the end of the trial, those who took valbenazine experienced improvement in the severity of involuntary movements, compared with those who received placebo. As a vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitor, valbenazine works by regulating the amount of dopamine that is released into nerve cells by blocking a protein in the brain. The drug, the first to receive approval for tardive dyskinesia in adults, will be marketed as Ingrezza by Neurocrine Biosciences. Valbenazine is reportedly being studied as a treatment for Tourette syndrome in children and adolescents.

In a statement, Mitchell Mathis, MD, director of the FDA’s division of psychiatry products in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, praised the approval as “an important advance for patients suffering with tardive dyskinesia.”

Characterized by uncontrolled movement of the face and body, tardive dyskinesia is a side effect in up to 8% of patients taking typical and atypical antipsychotics. The movement disorder also can cause other debilitating problems, including difficulty with chewing, speaking, and swallowing. Some data show that in about 87% of cases, the condition is irreversible even 3 years after the inciting agent has been discontinued (Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016. 32;124-6).

“Tardive dyskinesia can be disabling and can further stigmatize patients with mental illness,” Dr. Mathis said in the statement.

The side effects of valbenazine include sleepiness and QT prolongation. The agency said the patients taking the drug should not drive, operate heavy machinery, or engage in other potentially dangerous activities. Likewise, the drug should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or in those with abnormal heartbeats associated with a prolonged QT interval, the agency said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

The Food and Drug Administration has approved valbenazine capsules for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia in adults.

The approval, announced April 11, came after a 6-week, placebo-controlled trial of 234 participants that compared valbenazine to placebo. At the end of the trial, those who took valbenazine experienced improvement in the severity of involuntary movements, compared with those who received placebo. As a vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 inhibitor, valbenazine works by regulating the amount of dopamine that is released into nerve cells by blocking a protein in the brain. The drug, the first to receive approval for tardive dyskinesia in adults, will be marketed as Ingrezza by Neurocrine Biosciences. Valbenazine is reportedly being studied as a treatment for Tourette syndrome in children and adolescents.

In a statement, Mitchell Mathis, MD, director of the FDA’s division of psychiatry products in the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, praised the approval as “an important advance for patients suffering with tardive dyskinesia.”

Characterized by uncontrolled movement of the face and body, tardive dyskinesia is a side effect in up to 8% of patients taking typical and atypical antipsychotics. The movement disorder also can cause other debilitating problems, including difficulty with chewing, speaking, and swallowing. Some data show that in about 87% of cases, the condition is irreversible even 3 years after the inciting agent has been discontinued (Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016. 32;124-6).

“Tardive dyskinesia can be disabling and can further stigmatize patients with mental illness,” Dr. Mathis said in the statement.

The side effects of valbenazine include sleepiness and QT prolongation. The agency said the patients taking the drug should not drive, operate heavy machinery, or engage in other potentially dangerous activities. Likewise, the drug should be avoided in patients with congenital long QT syndrome or in those with abnormal heartbeats associated with a prolonged QT interval, the agency said.

[email protected]

On Twitter @ginalhenderson

William Beaumont: A Pioneer of Physiology

William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, was the first of several military and civilian medical facilities named for U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont (1785-1853). Beaumont was born into a large farming family in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was educated with his siblings in a local schoolhouse. His medical education was by apprenticeship with an established physician in Vermont. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen medical schools in the U.S., and most physicians were educated and trained as apprentices. In July 1812, he passed the Vermont medical examination and became a licensed physician.

In an age when no information traveled faster than the 4 legs of a horse, it is not known how much William Beaumont was aware of the events that led to the American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812. It is equally unknown whether a sense of patriotism, youthful adventurism, or simply the need for a job drove Beaumont to join the U.S. Army in September 1812. Regardless of the reasons, he soon was under fire as a Brevet Surgeon’s Mate with the 6th Regiment at the Battle of York in Canada.

The retreating British booby-trapped their powder magazine, which exploded on the Americans and caused more casualties than the battle itself. Beaumont wrote in his journal, “The surgeons wading in blood, cutting off arms, legs, and trepanning heads to rescue their fellow creatures from untimely deaths.” He also wrote that, “it awoke my liveliest sympathy” for his fellow soldiers; he worked for 48 hours without food or sleep. Beaumont saw additional action at Fort George and the Battle of Plattsburgh.Beaumont left the U.S. Army after the war, but following a few years of civilian practice, he returned to active duty and was assigned to the northwestern frontier post on Mackinac Island, Michigan, the site of lively summer fur trading between Canadian trappers and American traders. In June 1822, a young Canadian voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the upper left abdomen at close range with what we know today as a shotgun. Beaumont described the wound as the size of a man’s palm with burned lung and stomach spilling out as well as recently eaten food. He thought attempts to save St. Martin’s life were “entirely useless.”

But Beaumont gave it his best, and St. Martin miraculously survived. The wound healed but left a gastric fistula to the abdominal wall. Over time, Beaumont realized that he was able to witness the previously mysterious functions of the gastrointestinal tract. For more than 10 years, Beaumont studied the physiology of St. Martin’s fistulous stomach, leading to the publication of several articles and a book that earned Beaumont the reputation of at the very least the father of gastric physiology if not of American physiology.

Beaumont and St. Martin eventually parted ways. Beaumont pleaded with St. Martin to return for more studies, but with a wife and many children to support, St. Martin would not. Beaumont again left the U.S. Army to practice medicine in St. Louis, where in 1853, he slipped on ice and struck his head. Several weeks later at the age of 67, he died of his injuries. St. Martin died in 1880 at age 76, living almost 6 decades with a gastric fistula and fathering 17 children.

In 1921, the U.S. Army hospital at Ft. Bliss, Texas, was named for William Beaumont. The building was replaced in 1972 with a 12-story facility known as William Beaumont Army Medical Center. In November 1995, additional space was added for the VA health care center. In 1955, the William Beaumont Hospital opened in Royal Oak, Michigan. This civilian hospital has grown to a health care system with many facilities that include a school of medicine founded in 2011, all named for Beaumont.

For more detailed information on William Beaumont, read Frank TW. Builders of Trust, William Beaumont. The Borden Institute: Fort Detrick, Maryland; 2011.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at [email protected] or on Facebook.

William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, was the first of several military and civilian medical facilities named for U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont (1785-1853). Beaumont was born into a large farming family in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was educated with his siblings in a local schoolhouse. His medical education was by apprenticeship with an established physician in Vermont. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen medical schools in the U.S., and most physicians were educated and trained as apprentices. In July 1812, he passed the Vermont medical examination and became a licensed physician.

In an age when no information traveled faster than the 4 legs of a horse, it is not known how much William Beaumont was aware of the events that led to the American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812. It is equally unknown whether a sense of patriotism, youthful adventurism, or simply the need for a job drove Beaumont to join the U.S. Army in September 1812. Regardless of the reasons, he soon was under fire as a Brevet Surgeon’s Mate with the 6th Regiment at the Battle of York in Canada.

The retreating British booby-trapped their powder magazine, which exploded on the Americans and caused more casualties than the battle itself. Beaumont wrote in his journal, “The surgeons wading in blood, cutting off arms, legs, and trepanning heads to rescue their fellow creatures from untimely deaths.” He also wrote that, “it awoke my liveliest sympathy” for his fellow soldiers; he worked for 48 hours without food or sleep. Beaumont saw additional action at Fort George and the Battle of Plattsburgh.Beaumont left the U.S. Army after the war, but following a few years of civilian practice, he returned to active duty and was assigned to the northwestern frontier post on Mackinac Island, Michigan, the site of lively summer fur trading between Canadian trappers and American traders. In June 1822, a young Canadian voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the upper left abdomen at close range with what we know today as a shotgun. Beaumont described the wound as the size of a man’s palm with burned lung and stomach spilling out as well as recently eaten food. He thought attempts to save St. Martin’s life were “entirely useless.”

But Beaumont gave it his best, and St. Martin miraculously survived. The wound healed but left a gastric fistula to the abdominal wall. Over time, Beaumont realized that he was able to witness the previously mysterious functions of the gastrointestinal tract. For more than 10 years, Beaumont studied the physiology of St. Martin’s fistulous stomach, leading to the publication of several articles and a book that earned Beaumont the reputation of at the very least the father of gastric physiology if not of American physiology.

Beaumont and St. Martin eventually parted ways. Beaumont pleaded with St. Martin to return for more studies, but with a wife and many children to support, St. Martin would not. Beaumont again left the U.S. Army to practice medicine in St. Louis, where in 1853, he slipped on ice and struck his head. Several weeks later at the age of 67, he died of his injuries. St. Martin died in 1880 at age 76, living almost 6 decades with a gastric fistula and fathering 17 children.

In 1921, the U.S. Army hospital at Ft. Bliss, Texas, was named for William Beaumont. The building was replaced in 1972 with a 12-story facility known as William Beaumont Army Medical Center. In November 1995, additional space was added for the VA health care center. In 1955, the William Beaumont Hospital opened in Royal Oak, Michigan. This civilian hospital has grown to a health care system with many facilities that include a school of medicine founded in 2011, all named for Beaumont.

For more detailed information on William Beaumont, read Frank TW. Builders of Trust, William Beaumont. The Borden Institute: Fort Detrick, Maryland; 2011.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at [email protected] or on Facebook.

William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso, Texas, was the first of several military and civilian medical facilities named for U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont (1785-1853). Beaumont was born into a large farming family in Lebanon, Connecticut, and was educated with his siblings in a local schoolhouse. His medical education was by apprenticeship with an established physician in Vermont. At the time, there were fewer than a dozen medical schools in the U.S., and most physicians were educated and trained as apprentices. In July 1812, he passed the Vermont medical examination and became a licensed physician.

In an age when no information traveled faster than the 4 legs of a horse, it is not known how much William Beaumont was aware of the events that led to the American declaration of war against Great Britain in June 1812. It is equally unknown whether a sense of patriotism, youthful adventurism, or simply the need for a job drove Beaumont to join the U.S. Army in September 1812. Regardless of the reasons, he soon was under fire as a Brevet Surgeon’s Mate with the 6th Regiment at the Battle of York in Canada.

The retreating British booby-trapped their powder magazine, which exploded on the Americans and caused more casualties than the battle itself. Beaumont wrote in his journal, “The surgeons wading in blood, cutting off arms, legs, and trepanning heads to rescue their fellow creatures from untimely deaths.” He also wrote that, “it awoke my liveliest sympathy” for his fellow soldiers; he worked for 48 hours without food or sleep. Beaumont saw additional action at Fort George and the Battle of Plattsburgh.Beaumont left the U.S. Army after the war, but following a few years of civilian practice, he returned to active duty and was assigned to the northwestern frontier post on Mackinac Island, Michigan, the site of lively summer fur trading between Canadian trappers and American traders. In June 1822, a young Canadian voyageur, Alexis St. Martin, was accidentally shot in the upper left abdomen at close range with what we know today as a shotgun. Beaumont described the wound as the size of a man’s palm with burned lung and stomach spilling out as well as recently eaten food. He thought attempts to save St. Martin’s life were “entirely useless.”

But Beaumont gave it his best, and St. Martin miraculously survived. The wound healed but left a gastric fistula to the abdominal wall. Over time, Beaumont realized that he was able to witness the previously mysterious functions of the gastrointestinal tract. For more than 10 years, Beaumont studied the physiology of St. Martin’s fistulous stomach, leading to the publication of several articles and a book that earned Beaumont the reputation of at the very least the father of gastric physiology if not of American physiology.

Beaumont and St. Martin eventually parted ways. Beaumont pleaded with St. Martin to return for more studies, but with a wife and many children to support, St. Martin would not. Beaumont again left the U.S. Army to practice medicine in St. Louis, where in 1853, he slipped on ice and struck his head. Several weeks later at the age of 67, he died of his injuries. St. Martin died in 1880 at age 76, living almost 6 decades with a gastric fistula and fathering 17 children.

In 1921, the U.S. Army hospital at Ft. Bliss, Texas, was named for William Beaumont. The building was replaced in 1972 with a 12-story facility known as William Beaumont Army Medical Center. In November 1995, additional space was added for the VA health care center. In 1955, the William Beaumont Hospital opened in Royal Oak, Michigan. This civilian hospital has grown to a health care system with many facilities that include a school of medicine founded in 2011, all named for Beaumont.

For more detailed information on William Beaumont, read Frank TW. Builders of Trust, William Beaumont. The Borden Institute: Fort Detrick, Maryland; 2011.

About this column

This column provides biographical sketches of the namesakes of military and VA health care facilities. To learn more about the individual your facility was named for or to offer a topic suggestion, contact us at [email protected] or on Facebook.

Testosterone Trial Offers Plusses and Minuses

“Mixed results,” is the current status report on the Testosterone Trials (“T Trials”). In older men with low testosterone, 1 year of testosterone treatment not only improved bone density and corrected anemia, but also increased the volume of coronary artery plaque.

The T Trials were designed to determine whether testosterone treatment could alleviate problems, such as impaired cognition, anemia, cardiovascular disease, diminished sexual function, decreased mobility, and fatigue. The trials were conducted at 12 sites nationwide in 790 men aged ≥ 65 years. Participants were randomly assigned to apply testosterone gel or placebo to the skin daily. Serum testosterone was measured at 1, 2, 3,6, 9, and 12 months. The men were closely monitored for prostate and cardiovascular problems.

Related: Testosterone Replacement Therapy: Playing Catch-up With Patients

After 1 year of testosterone treatment, 54% of men with unexplained anemia and 52% of men with anemia from known causes had clinically significant increases in hemoglobin, compared with 15% and 12% of men in the placebo group. Older men with low testosterone had significantly increased volumetric bone density and estimated bone strength compared with the controls.

However, the testosterone-treated group also had significantly higher levels of coronary artery plaque, although only 170 men had coronary computed tomograph arteriography. The researchers found no significant differences between the 2 groups in cognition in older men with age-associated memory impairment.

Related: Restoring Testosterone Levels May Improve Sexual Function

The results illustrate the need for individualized decisions about testosterone treatment, said Evan Hadley, MD, director of National Institute on Aging’s Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology. The “diverse outcomes,” he notes, indicate the potential trade-offs between benefits and risks of testosterone treatment in older men. Clarifying the effects of testosterone will take longer, larger scale trials.

“Mixed results,” is the current status report on the Testosterone Trials (“T Trials”). In older men with low testosterone, 1 year of testosterone treatment not only improved bone density and corrected anemia, but also increased the volume of coronary artery plaque.

The T Trials were designed to determine whether testosterone treatment could alleviate problems, such as impaired cognition, anemia, cardiovascular disease, diminished sexual function, decreased mobility, and fatigue. The trials were conducted at 12 sites nationwide in 790 men aged ≥ 65 years. Participants were randomly assigned to apply testosterone gel or placebo to the skin daily. Serum testosterone was measured at 1, 2, 3,6, 9, and 12 months. The men were closely monitored for prostate and cardiovascular problems.

Related: Testosterone Replacement Therapy: Playing Catch-up With Patients

After 1 year of testosterone treatment, 54% of men with unexplained anemia and 52% of men with anemia from known causes had clinically significant increases in hemoglobin, compared with 15% and 12% of men in the placebo group. Older men with low testosterone had significantly increased volumetric bone density and estimated bone strength compared with the controls.

However, the testosterone-treated group also had significantly higher levels of coronary artery plaque, although only 170 men had coronary computed tomograph arteriography. The researchers found no significant differences between the 2 groups in cognition in older men with age-associated memory impairment.

Related: Restoring Testosterone Levels May Improve Sexual Function

The results illustrate the need for individualized decisions about testosterone treatment, said Evan Hadley, MD, director of National Institute on Aging’s Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology. The “diverse outcomes,” he notes, indicate the potential trade-offs between benefits and risks of testosterone treatment in older men. Clarifying the effects of testosterone will take longer, larger scale trials.

“Mixed results,” is the current status report on the Testosterone Trials (“T Trials”). In older men with low testosterone, 1 year of testosterone treatment not only improved bone density and corrected anemia, but also increased the volume of coronary artery plaque.

The T Trials were designed to determine whether testosterone treatment could alleviate problems, such as impaired cognition, anemia, cardiovascular disease, diminished sexual function, decreased mobility, and fatigue. The trials were conducted at 12 sites nationwide in 790 men aged ≥ 65 years. Participants were randomly assigned to apply testosterone gel or placebo to the skin daily. Serum testosterone was measured at 1, 2, 3,6, 9, and 12 months. The men were closely monitored for prostate and cardiovascular problems.

Related: Testosterone Replacement Therapy: Playing Catch-up With Patients

After 1 year of testosterone treatment, 54% of men with unexplained anemia and 52% of men with anemia from known causes had clinically significant increases in hemoglobin, compared with 15% and 12% of men in the placebo group. Older men with low testosterone had significantly increased volumetric bone density and estimated bone strength compared with the controls.

However, the testosterone-treated group also had significantly higher levels of coronary artery plaque, although only 170 men had coronary computed tomograph arteriography. The researchers found no significant differences between the 2 groups in cognition in older men with age-associated memory impairment.

Related: Restoring Testosterone Levels May Improve Sexual Function

The results illustrate the need for individualized decisions about testosterone treatment, said Evan Hadley, MD, director of National Institute on Aging’s Division of Geriatrics and Clinical Gerontology. The “diverse outcomes,” he notes, indicate the potential trade-offs between benefits and risks of testosterone treatment in older men. Clarifying the effects of testosterone will take longer, larger scale trials.

Study reveals global inequalities in childhood leukemia survival

New research has revealed global inequalities in survival rates for pediatric patients with leukemia.

Investigators analyzed data on nearly 90,000 pediatric leukemia patients treated in 53 countries.

In most countries, patients with lymphoid leukemias or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) saw an increase in 5-year survival between 1995 and 2009.

However, there were wide variations in survival between the countries.

The investigators reported these findings in The Lancet Haematology.

They evaluated data from 89,828 leukemia patients (ages 0 to 14) included in 198 cancer registries in 53 countries.

The team estimated 5-year net survival for patients with AML or lymphoid leukemias (controlling for non-leukemia-related deaths) by calendar period of diagnosis—1995–1999, 2000–2004, and 2005–2009—in each country.

For children diagnosed with lymphoid leukemias between 1995 and 1999, 5-year survival rates ranged from 10.6% (in China) to 86.8% (in Austria). For children diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, the rates ranged from 52.4% (Colombia) to 91.6% (Germany).

For AML, 5-year survival rates ranged from 4.2% (China) to 72.2% (Sweden) in patients diagnosed between 1995 and 1999. For children diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, 5-year survival rates ranged from 33.3% (Bulgaria) to 78.2% (Germany).

The investigators noted that, in some countries, survival for both groups of leukemia patients was consistently high.

In Austria, for example, 5-year survival rates for lymphoid leukemias were 86.8% in 1995-1999 and 91.1% in 2005-2009. For AML, rates were 60.1% and 72.6%, respectively.

Other countries saw substantial increases in survival over time.

In China, the 5-year survival rate for patients with lymphoid leukemias increased from 10.6% in 1995-1999 to 69.2% in 2005-2009. For patients with AML, the rate increased from 4.2% to 41.1%.

“These findings show the extent of worldwide inequalities in access to optimal healthcare for children with cancer,” said study author Audrey Bonaventure, MD, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“Providing additional resources, alongside evidence-based initiatives such as international collaborations and treatment guidelines, could improve access to efficient treatment and care for all children with leukemia. This would contribute substantially to reducing worldwide inequalities in survival.” ![]()

New research has revealed global inequalities in survival rates for pediatric patients with leukemia.

Investigators analyzed data on nearly 90,000 pediatric leukemia patients treated in 53 countries.

In most countries, patients with lymphoid leukemias or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) saw an increase in 5-year survival between 1995 and 2009.

However, there were wide variations in survival between the countries.

The investigators reported these findings in The Lancet Haematology.

They evaluated data from 89,828 leukemia patients (ages 0 to 14) included in 198 cancer registries in 53 countries.

The team estimated 5-year net survival for patients with AML or lymphoid leukemias (controlling for non-leukemia-related deaths) by calendar period of diagnosis—1995–1999, 2000–2004, and 2005–2009—in each country.

For children diagnosed with lymphoid leukemias between 1995 and 1999, 5-year survival rates ranged from 10.6% (in China) to 86.8% (in Austria). For children diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, the rates ranged from 52.4% (Colombia) to 91.6% (Germany).

For AML, 5-year survival rates ranged from 4.2% (China) to 72.2% (Sweden) in patients diagnosed between 1995 and 1999. For children diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, 5-year survival rates ranged from 33.3% (Bulgaria) to 78.2% (Germany).

The investigators noted that, in some countries, survival for both groups of leukemia patients was consistently high.

In Austria, for example, 5-year survival rates for lymphoid leukemias were 86.8% in 1995-1999 and 91.1% in 2005-2009. For AML, rates were 60.1% and 72.6%, respectively.

Other countries saw substantial increases in survival over time.

In China, the 5-year survival rate for patients with lymphoid leukemias increased from 10.6% in 1995-1999 to 69.2% in 2005-2009. For patients with AML, the rate increased from 4.2% to 41.1%.

“These findings show the extent of worldwide inequalities in access to optimal healthcare for children with cancer,” said study author Audrey Bonaventure, MD, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“Providing additional resources, alongside evidence-based initiatives such as international collaborations and treatment guidelines, could improve access to efficient treatment and care for all children with leukemia. This would contribute substantially to reducing worldwide inequalities in survival.” ![]()

New research has revealed global inequalities in survival rates for pediatric patients with leukemia.

Investigators analyzed data on nearly 90,000 pediatric leukemia patients treated in 53 countries.

In most countries, patients with lymphoid leukemias or acute myeloid leukemia (AML) saw an increase in 5-year survival between 1995 and 2009.

However, there were wide variations in survival between the countries.

The investigators reported these findings in The Lancet Haematology.

They evaluated data from 89,828 leukemia patients (ages 0 to 14) included in 198 cancer registries in 53 countries.

The team estimated 5-year net survival for patients with AML or lymphoid leukemias (controlling for non-leukemia-related deaths) by calendar period of diagnosis—1995–1999, 2000–2004, and 2005–2009—in each country.

For children diagnosed with lymphoid leukemias between 1995 and 1999, 5-year survival rates ranged from 10.6% (in China) to 86.8% (in Austria). For children diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, the rates ranged from 52.4% (Colombia) to 91.6% (Germany).

For AML, 5-year survival rates ranged from 4.2% (China) to 72.2% (Sweden) in patients diagnosed between 1995 and 1999. For children diagnosed between 2005 and 2009, 5-year survival rates ranged from 33.3% (Bulgaria) to 78.2% (Germany).

The investigators noted that, in some countries, survival for both groups of leukemia patients was consistently high.

In Austria, for example, 5-year survival rates for lymphoid leukemias were 86.8% in 1995-1999 and 91.1% in 2005-2009. For AML, rates were 60.1% and 72.6%, respectively.

Other countries saw substantial increases in survival over time.

In China, the 5-year survival rate for patients with lymphoid leukemias increased from 10.6% in 1995-1999 to 69.2% in 2005-2009. For patients with AML, the rate increased from 4.2% to 41.1%.

“These findings show the extent of worldwide inequalities in access to optimal healthcare for children with cancer,” said study author Audrey Bonaventure, MD, PhD, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine in the UK.

“Providing additional resources, alongside evidence-based initiatives such as international collaborations and treatment guidelines, could improve access to efficient treatment and care for all children with leukemia. This would contribute substantially to reducing worldwide inequalities in survival.” ![]()

FDA clears test for individual WBD platelet units

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted new clearance for Verax Biomedical’s Platelet PGD® Test.

This qualitative immunoassay is designed to detect aerobic and anaerobic Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in platelets.

The test is now cleared for use on single units of leukocyte-reduced or non-leukocyte-reduced whole blood-derived (WBD) platelets in plasma.

The Platelet PGD Test was previously cleared by the FDA as a safety measure to be used following testing with a growth-based, quality control (QC) test for platelet components that is cleared by the FDA.

For this indication, the Platelet PGD Test can be used within 24 hours of transfusion on:

- Leukocyte-reduced apheresis platelets suspended in plasma

- Leukocyte-reduced apheresis platelets suspended in platelet additive solution C and plasma

- Pre-storage pools of up to 6 leukocyte-reduced WBD platelets suspended in plasma.

When used as a safety measure, the Platelet PGD Test can extend the dating of apheresis platelets in plasma from 5 to 7 days.

The Platelet PGD Test also has FDA clearance as a QC test for use on pools of up to 6 units of leukocyte-reduced and non-leukocyte-reduced WBD platelets suspended in plasma that are pooled within 4 hours of transfusion.

The latest FDA clearance extends this use to individual units of WBD platelets in plasma.

“[The new clearance] has been requested by current users of PGD as well as being outlined as a need in pending FDA Draft Guidance to address the risk of bacterial contamination in platelets,” said Jim Lousararian, chief executive officer of Verax Biomedical.

According to the company, the new clearance is intended to help reduce the risk of bacterial contamination for pediatric patients receiving platelet transfusions.

“Pediatric patients pose unique challenges in transfusion medicine,” said Paul Mintz, MD, chief medical officer of Verax Biomedical.

“They require small platelet doses and possess fragile immune systems. PGD testing individual WBD units for transfusion makes it practical to provide bacterially tested platelets to this most vulnerable group of patients.”

Multicenter study

The Verax PGD® test was evaluated in a 2-year study including 18 US hospitals. The results were published in Transfusion in 2011.

The objective of the study was to evaluate the test’s ability to detect bacterially contaminated units in the US apheresis inventory that tested negative for contamination by existing growth-based QC tests.

A total of 9 contaminated units were detected by PGD and confirmed as bacterially contaminated in a population of 27,620 leukocyte-reduced apheresis units (1:3,069 doses tested).

All 9 units had previously tested negative by growth-based QC methods applied earlier in unit life in conformance with all applicable AABB and CAP standards for bacterial testing.

Researchers said the study clearly demonstrated the ability of the Platelet PGD Test to detect and interdict contaminated units missed by current QC testing methods. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted new clearance for Verax Biomedical’s Platelet PGD® Test.

This qualitative immunoassay is designed to detect aerobic and anaerobic Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria in platelets.

The test is now cleared for use on single units of leukocyte-reduced or non-leukocyte-reduced whole blood-derived (WBD) platelets in plasma.

The Platelet PGD Test was previously cleared by the FDA as a safety measure to be used following testing with a growth-based, quality control (QC) test for platelet components that is cleared by the FDA.

For this indication, the Platelet PGD Test can be used within 24 hours of transfusion on:

- Leukocyte-reduced apheresis platelets suspended in plasma

- Leukocyte-reduced apheresis platelets suspended in platelet additive solution C and plasma

- Pre-storage pools of up to 6 leukocyte-reduced WBD platelets suspended in plasma.

When used as a safety measure, the Platelet PGD Test can extend the dating of apheresis platelets in plasma from 5 to 7 days.

The Platelet PGD Test also has FDA clearance as a QC test for use on pools of up to 6 units of leukocyte-reduced and non-leukocyte-reduced WBD platelets suspended in plasma that are pooled within 4 hours of transfusion.

The latest FDA clearance extends this use to individual units of WBD platelets in plasma.

“[The new clearance] has been requested by current users of PGD as well as being outlined as a need in pending FDA Draft Guidance to address the risk of bacterial contamination in platelets,” said Jim Lousararian, chief executive officer of Verax Biomedical.